A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocols for Protein Systems

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to design, execute, and validate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein systems.

A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocols for Protein Systems

Abstract

This article provides a complete roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to design, execute, and validate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein systems. It covers foundational principles, from force field selection and system setup to advanced enhanced sampling techniques. The guide offers a detailed, step-by-step methodological protocol using common tools like GROMACS, highlights critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to avoid common pitfalls, and concludes with robust methods for validating simulation results against experimental data to ensure scientific reliability. This integrated approach equips scientists to leverage MD simulations effectively for studying protein structure, dynamics, and function in biomedical research.

Core Principles and System Setup for Robust Protein Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational structural biology, enabling researchers to investigate protein dynamics, conformational changes, and molecular interactions with atomic-level detail over nanosecond to microsecond timescales [1]. The value of MD simulations in protein research extends from fundamental studies of protein folding and function to applied drug discovery, where they can elucidate mechanisms of action, assess the effects of mutations, and probe interactions with small molecule substrates or other macromolecules [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the complete MD workflow—from initial protein structure to production simulation—is essential for generating reliable, publication-quality results. This protocol outlines a standardized approach for running MD simulations of proteins using the GROMACS software suite, one of the most robust and popular MD simulation packages available today [1] [3].

The fundamental principle underlying MD simulations is the numerical solution of Newton's equations of motion for each atom in the system. As described by the equation ( mi\frac{d^2 xi}{dt^2} = -(\nabla U)_i ), the acceleration of each atom depends on its mass and the force acting upon it, which is derived from the potential energy field ( U ) [4]. These equations are solved iteratively using algorithms like velocity-Verlet, which updates atomic positions and velocities based on the forces calculated at each time step [4]. The accuracy of these simulations depends critically on the force field—a set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of the system as a sum of bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (electrostatics, van der Waals) [4].

Theoretical Foundation

Force Fields and Their Application

The choice of force field represents a critical decision point in any MD simulation, as it determines how physical interactions are modeled computationally. Different force fields employ distinct functional forms and parameterization strategies, making it essential to maintain consistency throughout a simulation project. Popular all-atom force fields for protein simulations include CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS/AA, and GROMOS, each with specific strengths and recommended applications [4] [1] [3]. For instance, the Amber99sb-ildn force field is often recommended for all-atom simulations of proteins [4]. It is crucial to never mix parameters from different force fields, as this can lead to unphysical results and unreliable conclusions [4].

The potential energy ( U ) in a typical force field is composed of bonded (( U{bonded} )) and non-bonded (( U{non-bonded} )) components [4]:

[ \begin{align} U_{bonded} & = \sum_{bonds} \frac{1}{2}k_{bond} (r_{ij} - r_0)^2 \ & + \sum_{angles} \frac{1}{2} k_{angle} (\theta_{ijk} - \theta_{0})^2 \ & + \sum_{dihedrals} k_{\phi,n} [\cos(n\phi_{ijkl} +\delta_n) +1]\ & + \sum_{impropers} k_{improper} (\chi_{i^{}jkl} - \chi_0)^2 \end{align*} ]

[ \begin{align} U_{non~bonded} & = \sum_{nb~pairs} \Big[ \frac{q_i q_j}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r_{ij}} + \Big(\frac{A_{ij}}{r_{ij}^{12}} - \frac{B_{ij}}{r_{ij}^6}\Big)\Big] \end{align} ]

The non-bonded interactions are particularly computationally intensive as they must be calculated for all pairs of atoms that are not directly bonded, though various cutoff schemes and particle-mesh Ewald methods help manage this complexity [4] [3].

Integration Algorithms and Time Steps

The velocity-Verlet algorithm is commonly used to integrate Newton's equations of motion in MD simulations due to its numerical stability and conservation properties [4]. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

[ \begin{align} x_i(t+\Delta t) & = x_i(t) + v_i(t) \Delta t+ \frac{\Delta t^2}{2m_i}F_i(t)\ v_i(t+\Delta t) & = v_i(t) + \frac{\Delta t}{2m_i}\big[F_i(t+\Delta t) + F_i(t)\big] \end{align} ]

The choice of time step (( \Delta t )) represents a compromise between simulation efficiency and numerical accuracy. To properly capture the fastest motions in the system (typically hydrogen bond vibrations), the time step should not exceed 1/10 of the period of these fastest motions [4]. For all-atom simulations with hydrogen atoms, this typically translates to a time step of 1-2 femtoseconds, often with constraints applied to bonds involving hydrogen atoms to allow for slightly longer time steps [4].

Computational Protocol

System Preparation

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Application in MD Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [1] [3] | MD simulation engine | Production simulations, analysis |

| OpenMM [5] [2] | MD simulation toolkit | Alternative simulation engine |

| MDtraj [5] [6] | Trajectory analysis | Analysis of simulation outputs |

| mdciao [6] | Analysis and visualization | Specialized analysis of contact frequencies |

| PDBFixer [5] | Structure preparation | Cleaning PDB files, adding missing atoms |

| PackMol [5] | System preparation | Solvation and ion placement |

| VMD/PyMOL [1] [6] | Visualization | Visual inspection of structures and trajectories |

Initial Structure Acquisition and Processing

The MD workflow begins with a protein structure file, typically in PDB format obtained from the Protein Data Bank or from homology modeling if an experimental structure is unavailable [1]. The structure should be carefully cleaned to remove non-protein atoms such as water molecules and ligands unless these are specifically part of the system under investigation [1] [3]. This can be accomplished using tools like grep to remove HETATM records or using specialized software like PDBFixer [5] [3]. For this protocol, we use hen egg white lysozyme (PDB: 1AKI) as an example system, a small (129 residues), highly stable globular protein ideal for demonstration purposes [3].

The initial setup is performed using GROMACS's pdb2gmx tool, which converts the PDB file into GROMACS format (.gro), generates the topology, and creates a position restraint file for later use [1] [3]:

During this step, the user must select an appropriate force field and water model. The OPLS/AA force field with SPC/E water model represents a sound choice for protein systems [3].

Solvation and Ion Addition

To mimic physiological conditions, the protein must be solvated in water, and ions may be added to neutralize the system's charge or achieve specific ionic concentrations. The process begins by defining a simulation box around the protein using editconf [1]:

This command centers the protein in a cubic box with a 1.4 nm distance from the protein to the box edge. While cubic boxes are intuitive, rhombic dodecahedron boxes are more efficient for simulating globular proteins as they minimize the number of water molecules required [1] [3].

The system is then solvated using the solvate command, which adds water molecules to fill the box [1] [3]:

Finally, ions are added to neutralize the system using the genion tool [1] [3]:

For lysozyme, which carries a charge of +8, this would result in the addition of 8 chloride anions to neutralize the system [3].

Energy Minimization

Energy minimization is essential to remove any steric clashes or unusual geometry that would artificially raise the system's energy [3]. This step relaxes the structure by finding the nearest local energy minimum using algorithms like steepest descent [3].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Energy Minimization

| Parameter | Typical Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Integrator | Steepest descent | Robust energy minimization algorithm |

| Number of steps | 50,000 | Maximum minimization steps |

| EM tolerance | 1000 kJ/mol·nm | Convergence criterion |

| Coulomb cut-off | 1.0 nm | Distance for electrostatic interactions |

| vdW cut-off | 1.0 nm | Distance for van der Waals interactions |

The energy minimization is performed using GROMACS's grompp and mdrun commands [1] [3]:

System Equilibration

Before production simulation, the system must be equilibrated under appropriate thermodynamic conditions. This is typically performed in two stages: first under the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature), followed by the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) [3].

During NVT equilibration, the protein position is restrained while the solvent is allowed to move freely, using the position restraint file generated during the initial setup [3]. This allows the solvent to arrange itself naturally around the protein without the protein itself undergoing large conformational changes. A typical NVT equilibration runs for 50-100 ps while maintaining temperature using a thermostat like Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover [3].

The NPT equilibration continues with position restraints but now maintains constant pressure using a barostat such as Parrinello-Rahman, allowing the system density to adjust to the correct value [3]. This step typically also runs for 50-100 ps.

Production Simulation

The production simulation phase follows equilibration and is conducted without position restraints, allowing the protein to move freely according to the force field parameters. This phase generates the trajectory data that will be analyzed to answer scientific questions. The length of production simulations depends on the biological processes being studied, but modern simulations typically range from nanoseconds to microseconds [1] [7].

For adequate sampling of protein dynamics, simulation times should be sufficient to observe the processes of interest. For small proteins like lysozyme, 1-10 ns may suffice for basic stability assessment, while larger conformational changes may require microsecond-scale simulations [1]. The production simulation is executed using:

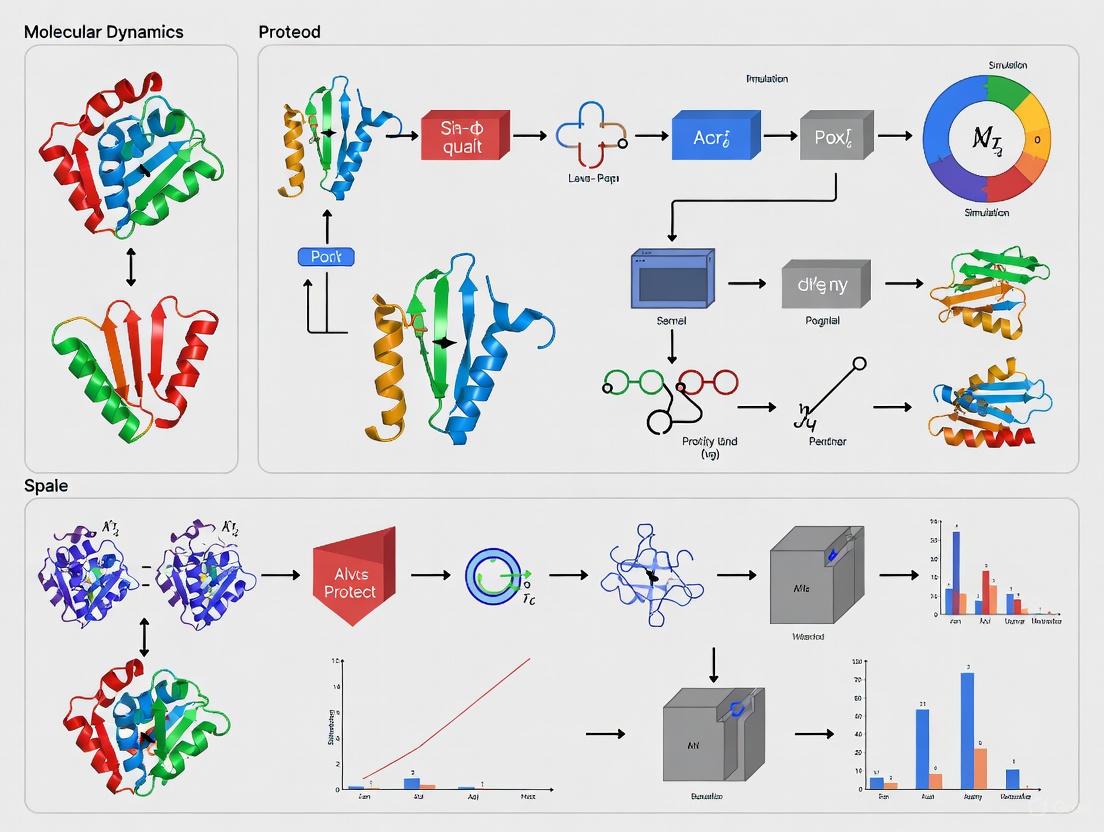

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Complete MD simulation workflow from initial structure to analysis.

Analysis Methods

Following production simulation, various analysis techniques can be applied to extract meaningful biological insights from the trajectory data. Common analyses include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability by calculating the average distance between atoms after superposition on a reference structure [7] [6].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies per-residue flexibility throughout the simulation [6].

- Radius of Gyration: Assesses protein compactness and folding状态 [5].

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Tracks changes in secondary structure elements over time [5].

- Residue-Residue Contact Analysis: Identifies persistent interactions within the protein or with ligands [6].

The mdciao package provides a particularly accessible approach for analyzing contact frequencies using a modified version of the MDtraj compute_contacts method [6]. The contact frequency for a residue pair (A,B) is calculated as:

[ CF{AB}^i = \frac{1}{Nf^i} \sum{t=1}^{Nf^i} C_{AB}(t) ]

where ( C_{AB}(t) ) is the contact function that depends on the distance cutoff δ [6].

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

MD simulations have become increasingly valuable in drug discovery, particularly in understanding molecular interactions that influence key pharmaceutical properties like solubility [7]. Machine learning analysis of MD-derived properties can predict critical characteristics such as aqueous solubility, which significantly influences a medication's bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy [7].

Research demonstrates that MD-derived properties including Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies, Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv), and RMSD can be highly effective in predicting solubility when combined with machine learning algorithms [7]. These approaches allow researchers to prioritize compounds with optimal solubility profiles early in the drug discovery process, minimizing resource consumption and enhancing the likelihood of clinical success [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for MD Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in MD Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS/AA, GROMOS | Define potential energy functions and parameters |

| Water Models | SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P | Represent solvent water molecules |

| Ion Parameters | Sodium, Chloride | Neutralize system charge and mimic physiological conditions |

| Software Packages | GROMACS, OpenMM, NAMD | MD simulation engines |

| Analysis Tools | MDtraj, MDanalysis, mdciao | Process and analyze trajectory data |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera | Visual inspection of structures and trajectories |

| Computing Resources | Workstations, HPC clusters, Cloud computing | Provide necessary computational power |

This protocol has outlined a comprehensive workflow for molecular dynamics simulations of proteins, from initial structure preparation through production simulation and analysis. The standardized approach using GROMACS ensures reproducibility and reliability of results, which is essential for both basic research and drug development applications. As MD simulations continue to evolve with improvements in force fields, sampling algorithms, and computational hardware, they offer increasingly powerful insights into protein dynamics and function. The integration of MD with machine learning approaches further expands its utility in predicting key pharmaceutical properties, underscoring its growing importance in modern drug discovery pipelines.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on molecular dynamics (MD) simulation protocols for protein research, the selection of an empirical force field (FF) represents one of the most critical methodological choices. The force field, a combination of mathematical functions and parameters describing the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates, directly determines the accuracy and reliability of simulations [8]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, an inappropriate selection can compromise predictions of protein structure, dynamics, function, and ligand interaction, potentially derailing costly research and development efforts.

This Application Note provides a structured comparison of four widely used biomolecular force fields—CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, and OPLS—focusing on their theoretical foundations, performance in benchmarking studies, and practical guidance for deployment in protein simulation protocols. The objective is to equip computational researchers with the necessary information to make an informed choice tailored to their specific protein system and research question.

The major force fields share a common mathematical form for additive energy calculations, comprising terms for bond stretching, angle bending, dihedral torsions, and non-bonded van der Waals and electrostatic interactions [8]. However, they differ significantly in their parameterization philosophies and target data, leading to variations in performance.

CHARMM: The CHARMM project is a comprehensive force field developed with a focus on reproducing a wide range of experimental data and quantum mechanical (QM) calculations for small model compounds [8]. Its recent versions, such as CHARMM36 (C36), have introduced a new backbone CMAP potential corrected against data on small peptides and folded proteins, and updated side-chain dihedral parameters, leading to a more balanced potential energy surface [8].

AMBER: The AMBER family of force fields (e.g., ff99SB-ILDN, ff03*) has been continually refined, with particular emphasis on improving the backbone and side-chain torsion potentials. A key development has been the adjustment of backbone potentials to achieve a better balance between helical and coil conformations, addressing earlier biases [9] [8].

GROMOS: The GROMOS force fields are parameterized to be consistent with the GROMOS simulation package and are often developed as a unified set of parameters. GROMOS 43A1, for instance, has been tested for the prediction of liquid-state properties [10]. These force fields are widely used for simulating proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids.

OPLS: The Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS) force fields, such as OPLS-AA, were originally parameterized to reproduce thermodynamic and structural properties of organic liquids [10] [11]. This makes them particularly attractive for studies where solvation and liquid-state behavior are critical. Recent benchmarking on a SARS-CoV-2 protease showed that OPLS-AA excelled at maintaining the native fold in longer simulations [11].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Biomolecular Force Fields

| Force Field | Parameterization Philosophy | Key Strengths | Notable Variants |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | Fit to experimental data and QM calculations for model compounds; balanced treatment of backbone and side-chains [8]. | Broad coverage of biological molecules (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids); improved backbone CMAP in C36 [8]. | CHARMM22*, CHARMM27, CHARMM36 [9] [8] |

| AMBER | Continual refinement of dihedral angles; fitting to QM data and NMR data from unfolded proteins [8]. | Good agreement with NMR data for folded proteins [9]; extensive community use and testing. | ff99SB-ILDN, ff99SB-ILDN, ff03, ff03 [9] [8] |

| GROMOS | Parameterized as a unified set; often associated with the GROMOS simulation package. | Good performance for liquid-state properties and protein dynamics [10]. | GROMOS 43A1, GROMOS 54A7 [10] |

| OPLS | Optimized for thermodynamic properties of liquids; transferable parameters [10] [11]. | Excellent reproduction of liquid densities and superior performance in maintaining native folds in long simulations [10] [11]. | OPLS-AA, OPLS-AA/L [11] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The true test of a force field lies in its performance in molecular simulations. Benchmarking against experimental data is essential for evaluating accuracy. Quantitative assessments have been conducted on properties ranging from vapor-liquid coexistence curves for small molecules to NMR observables and native fold stability for proteins.

One study evaluating vapor-liquid coexistence and liquid densities for small organic molecules found that the TraPPE force field was most accurate for liquid densities, with CHARMM being a close contender. For vapor densities, AMBER-96 showed high accuracy at various error tolerances [10]. In protein simulations, a multi-microsecond study of ubiquitin and the B3 domain of Protein G (GB3) revealed distinct performance tiers. Several force fields, including CHARMM22*, CHARMM27, and Amber ff99SB-ILDN, demonstrated a reasonably good agreement with experimental NMR data [9]. In contrast, simulations with OPLS and CHARMM22 exhibited conformational drift over time, reducing their agreement with experiments [9].

A more recent benchmark focusing on the SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro) found that while most force fields (OPLS-AA, CHARMM27, CHARMM36, AMBER03) could reproduce the native fold over hundreds of nanoseconds, OPLS-AA-based setups outperformed others in longer simulations, better maintaining the catalytic domain's folding [11].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Force Fields in Various Studies

| Force Field | Liquid Density Accuracy [10] | Vapor Density Accuracy [10] | Agreement with Protein NMR Data [9] | Long-Term Native Fold Stability [11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM22 | Not the most accurate | Not the most accurate | Conformational drift in long simulations [9] | - |

| CHARMM27 | - | - | Good agreement [9] | Showed local unfolding in long PLpro simulations [11] |

| CHARMM36 | - | - | - | Showed local unfolding in long PLpro simulations [11] |

| AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | - | - | Good agreement [9] | - |

| AMBER03 | - | - | Intermediate agreement [9] | Showed local unfolding in long PLpro simulations [11] |

| OPLS-AA | Good for organic molecules [10] | - | Conformational drift in long simulations [9] | Best performance for PLpro native fold [11] |

| TraPPE | Best overall [10] | - | - | - |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Benchmarking Force Fields on a Target Protein

This protocol outlines the steps for evaluating the performance of different force fields on a specific protein system, such as a viral protease, to determine the most suitable one for a research project [11].

System Preparation: a. Obtain the initial protein coordinate file, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). b. Use a tool like

pdb2gmx(GROMACS),tleap(AMBER), or theCHARMM-GUIweb server to set up the simulation system with the desired force field. c. Solvate the protein in a periodic box of water, ensuring a minimum distance (e.g., 1.0 nm) between the protein and the box edge. d. Add physiologically relevant concentrations of ions (e.g., 100 mM NaCl) to neutralize the system's net charge and replicate experimental conditions [11].Simulation Setup: a. Perform energy minimization to remove any steric clashes. b. Equilibrate the system in two phases: first with positional restraints on the protein heavy atoms in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for 100-200 ps, followed by a similar equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature). c. Run multiple independent production MD simulations (at least 3 replicas per force field) for the desired length (e.g., hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds). The temperature should be set to the physiologically relevant value (e.g., 310 K) [11].

Analysis and Comparison: a. Calculate the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone to assess global stability. b. Calculate the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) to analyze local flexibility and compare it to experimental B-factors, if available. c. Monitor key structural metrics, such as the distance between catalytic residues or the radius of gyration [11]. d. Employ essential subspace analysis (Principal Component Analysis) to compare large-scale conformational dynamics across force fields [9]. e. Compare simulation-derived NMR observables (e.g., residual dipolar couplings, relaxation order parameters) with experimental data when available [9].

Protocol for Liquid-Phase Property Prediction

This protocol describes the use of Monte Carlo simulations to assess a force field's ability to predict thermodynamic properties like vapor-liquid coexistence curves, which is a key strength of force fields like OPLS and TraPPE [10].

System Initialization: a. Select the small organic molecule of interest. b. Define the simulation box with a sufficient number of molecules for the liquid and vapor phases in the Gibbs ensemble.

Simulation Execution: a. Utilize Monte Carlo simulations in the NPT (isobaric-isothermal) or NVT-Gibbs ensemble as implemented in packages like the MCCCS Towhee simulation program [10]. b. Employ advanced sampling techniques such as configurational-bias Monte Carlo to improve efficiency. c. Use a dual (coupled-decoupled) cutoff method for non-bonded interactions (e.g., 10 Å and 5 Å) [10].

Data Analysis: a. Compute liquid and vapor densities at various temperatures to construct the coexistence curve. b. Extrapolate the critical temperature using the density scaling law and the law of rectilinear diameters [10]. c. Compare the simulated coexistence densities and critical temperature with experimental data to evaluate the force field's accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Parameters for Force Field Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | Software packages that perform the numerical integration of the equations of motion. | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM, CHARMM. |

| System Setup Tools | Utilities for building a simulation system, including solvation and ionization. | CHARMM-GUI, tleap (AMBER), pdb2gmx (GROMACS). |

| Water Models | Mathematical models representing water molecules within the force field. | TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP5P; choice can impact dynamics and should match the force field recommendation [11]. |

| Force Field Parameter Files | Files containing all the specific bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded parameters for atoms and residues. | charmm36.xml (CHARMM36 in GROMACS), amber99sb-ildn.ff (in GROMACS), OPLS-AA parameter set. |

| TraPPE Force Field | A force field parameterized specifically for high accuracy in predicting fluid phase equilibria [10]. | Predicting vapor-liquid coexistence curves and liquid densities for organic molecules [10]. |

| CMAP Correction | A grid-based energy correction term applied to the protein backbone dihedrals (ϕ, ψ) to improve secondary structure accuracy. | Used in CHARMM36 and some AMBER variants to achieve a more realistic Ramachandran plot and protein stability [8]. |

Decision Framework and Visual Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a force field based on the research objective and system characteristics.

The critical choice between CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, and OPLS is not a matter of identifying a single "best" force field, but rather of selecting the most appropriate tool for a specific scientific problem. Benchmarking studies consistently show that modern versions like CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, and OPLS-AA provide high-quality results, but their relative performance can depend on the context—whether simulating a folded protein's dynamics, predicting liquid-phase thermodynamics, or modeling a complex multi-component system.

The most robust strategy for a new research project, especially one targeting a novel protein or under non-standard conditions, is to consult recent literature on similar systems and, where feasible, perform a targeted benchmark. By following the structured protocols and decision framework outlined in this document, researchers can make a justified and critical choice of force field, thereby ensuring the molecular dynamics simulation protocol forms a solid foundation for their scientific discoveries in protein research.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of proteins, creating a realistic environment is crucial for obtaining biologically relevant results. The setup involves making critical decisions about the boundary conditions of the system, the shape and size of the simulation box, and how to represent the solvent environment. These choices significantly impact the computational cost, accuracy, and physical validity of the simulation. This application note provides detailed protocols for implementing periodic boundary conditions (PBC), selecting appropriate box types, and choosing between explicit and implicit solvation methods within the context of protein simulations. Proper implementation of these components is essential for simulating biological systems accurately while managing computational expense, and is a foundational step in any MD protocol for protein research.

Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC)

Concept and Implementation

Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are a computational method used to minimize finite-size effects by simulating a small part of a system (the unit cell) that is surrounded by exact copies of itself in all directions [12]. In this setup, when a particle exits the simulation box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters through the opposite face [13]. The topology of a three-dimensional system with PBC is equivalent to a torus [12]. This approach effectively creates an infinite system and eliminates vacuum interfaces, which is particularly important for simulating bulk solutions or biological membranes.

In MD packages like GROMACS, PBC are combined with the minimum image convention, which stipulates that each particle interacts only with the closest image of any other particle in the system [14]. For a cubic box, this requires that the cutoff radius ((R_c)) for non-bonded interactions must be less than half the shortest box vector [14]:

[R_c < \frac{1}{2} \min(\|\mathbf{a}\|, \|\mathbf{b}\|, \|\mathbf{c}\|)]

This restriction ensures that a particle does not interact with multiple images of the same particle.

Practical Considerations and Artifacts

While PBC reduce surface artifacts, they introduce periodicity effects that researchers must recognize and manage:

- Visualization Artifacts: During trajectory analysis, molecules may appear to be broken, diffuse out of the box, or have unrealistic bonds across the cell [13]. These are visualization artifacts, not errors, resulting from the fundamental nature of PBC.

- Correcting Trajectories: These visual issues can be corrected after simulation using tools like

gmx trjconvin GROMACS. A suggested workflow involves [13]:- Making molecules whole

- Clustering molecules if desired

- Removing jumps using a first-frame reference

- Centering the system

- Applying fitting for analysis

- Electrostatic Considerations: For systems containing ionic interactions, the net charge of the unit cell should be zero to avoid summation issues with long-range electrostatic forces [12]. This is typically achieved by adding counterions.

- System Size Requirements: The simulation box must be large enough to prevent a molecule from interacting with its own periodic image. A common recommendation is to maintain at least 1 nm of solvent between the protein surface and the box edges in all dimensions [12].

Table 1: Common PBC-Related Artifacts and Solutions

| Artifact | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Molecules appearing broken | Visualization of a molecule crossing the box boundary | Use gmx trjconv -pbc mol to make molecules whole |

| Holes in solvent | Protein protruding through one face creates a complementary void on the opposite face | Understand this is normal; use gmx trjconv -center for visualization |

| Unphysical bonds across the box | Visualization connecting atoms in primary cell with their periodic images | Use gmx trjconv -pbc nojump to remove periodic jumps |

| Excessive diffusion | Molecules freely diffuse in periodic space | Use gmx trjconv -pbc cluster to keep molecules grouped |

Box Types and Selection

Common Box Geometries

The simulation box must be a space-filling shape that tiles perfectly in three-dimensional space [14]. While a cubic box is the most intuitive, other shapes can be more efficient for simulating biomolecules.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Box Types for Biomolecular Simulations

| Box Type | Volume for Same Image Distance | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic | (d^3) (Reference) | Simple to implement and understand | Largest solvent requirement; computationally expensive | Membrane systems; simple solutes |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron (xy-square) | (0.707d^3) (29% less than cube) | Reduced solvent molecules; faster computation | Less familiar shape; special visualization requirements | Spherical or flexible proteins in solution |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron (xy-hexagon) | (0.707d^3) (29% less than cube) | 14% smaller cross-sectional area than square version | Requires adjustment of box height | Membrane protein simulations |

| Truncated Octahedron | (0.770d^3) (23% less than cube) | More spherical than cube; good efficiency | More complex to set up | Globular proteins |

Protocol: Selecting and Implementing Box Type

Objective: Choose an optimal box type for simulating a solvated protein system to balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy.

Materials:

- Protein structure file (PDB format)

- MD software (e.g., GROMACS with

editconfutility) - Solvent model (e.g., TIP3P water)

Methodology:

Determine System Size Requirements:

- Measure the maximum diameter of the protein ((d_{protein})) using visualization software

- Determine cutoff distance ((R_c)), typically 1.0-1.2 nm for modern force fields

- Calculate minimum box size: (d{box} = d{protein} + 2 \times R_c)

- Add additional margin (0.5-1.0 nm) to prevent artificial periodicity effects [12]

Select Appropriate Box Type:

- For globular proteins: Use rhombic dodecahedron to minimize solvent molecules [14]

- For membrane systems: Use cubic or hexagonal rhombic dodecahedron boxes

- For elongated proteins: Consider rectangular boxes that match the protein shape

Implement Box in GROMACS:

Verify Box Dimensions:

- Check that all box vectors satisfy: (R_c < \frac{1}{2} \min(\|\mathbf{a}\|, \|\mathbf{b}\|, \|\mathbf{c}\|)) [14]

- Ensure protein is completely contained within the box with sufficient margin

Considerations:

- The rhombic dodecahedron reduces solvent requirements by approximately 29% compared to a cubic box with the same image distance, significantly decreasing computational cost [14]

- For production simulations, the box shape should remain consistent with the choice made during energy minimization and equilibration phases

- When using non-rectangular boxes, ensure all analysis tools properly handle the triclinic geometry

Solvation Methods

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvation treats each solvent molecule as individual atoms with specific interactions. For aqueous systems, this means including thousands of discrete water molecules around the solute.

Advantages:

- Physical Accuracy: Reproduces molecular details of solute-solvent interactions, including hydrogen bonding networks and dielectric screening [15]

- Proper Dynamics: Maintains correct viscosity and hydrodynamic properties

- Validated: Consistently shows better agreement with experimental NMR data compared to implicit models [15]

Disadvantages:

- Computational Cost: Water molecules constitute >80% of atoms in typical systems, dramatically increasing computation time

- Sampling Limitations: Slow dynamics due to physical viscosity of explicit water

Protocol: Explicit Solvation with GROMACS

Objective: Solvate a protein in an explicit water box using optimal parameters for biomolecular simulation.

Materials:

- Protein structure in simulation box (from previous step)

- Water model (e.g., TIP3P, SPC, OPC)

- GROMACS utilities (

gmx solvate,gmx genion)

Methodology:

Select Water Model:

Solvate the System:

Add Ions for Neutrality:

- Calculate system charge from topology

- Add counterions to achieve net zero charge [12]

Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes

- Continue until maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm

Validation:

- Check final density after NPT equilibration (~1000 kg/m³ for water)

- Monitor potential energy stability during production dynamics

- Verify radial distribution functions match expected water properties

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvation represents solvent as a continuous medium rather than individual molecules, using an analytical approximation to estimate solvation effects [18].

Common Implicit Solvent Methods:

Table 3: Comparison of Implicit Solvation Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Born (GB) | Approximates Poisson-Boltzmann using Born radii | Fast calculation; reasonable accuracy for electrostatic solvation | Less accurate for nonpolar contributions; parameter-dependent |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) | Numerical solution of PB equation with dielectric boundaries | More rigorous electrostatics; better for inhomogeneous systems | Computationally expensive; slow for dynamics |

| ASA-based models | Linear relation between SASA and solvation free energy | Captures hydrophobic effect; computationally simple | Misses specific electrostatic effects; parameterization challenges |

Advantages of Implicit Solvent:

- Computational Speed: No explicit water molecules dramatically reduces system size

- Enhanced Sampling: Absence of viscosity allows faster conformational transitions

- Direct Free Energy: Some models directly provide solvation free energies

Disadvantages and Artifacts:

- Missing Molecular Details: No explicit hydrogen bonding with solvent molecules [15]

- Incomplete Physics: Lack of microscopic viscosity and hydrodynamics [18]

- Structural Artifacts: Can lead to protein compaction, excessive internal hydrogen bonding, and distortion of surface elements compared to explicit solvent [15]

Protocol: Implicit Solvation Setup

Objective: Configure an implicit solvent simulation for rapid sampling of protein conformations.

Materials:

- Protein structure file

- MD software with implicit solvent capability (e.g., GROMACS with GB model)

- Implicit solvent parameters

Methodology:

Select Implicit Solvent Model:

- For general purpose: Generalized Born with SA (GBSA) For electrostatic focus: Poisson-Boltzmann For speed: Accessible Surface Area (ASA) methods

Configure Parameter File:

Run Simulation:

- Note that no explicit solvation step is needed

- Electrostatic cutoff may be increased due to lack of periodic boundary artifacts

- Sampling occurs more rapidly due to reduced friction

Considerations:

- Implicit solvent is particularly useful for:

- Quick preliminary simulations

- Systems with large conformational changes

- Free energy calculations

- Validation with explicit solvent is recommended for critical results

- Newer hybrid approaches combine explicit first solvation shell with implicit bulk solvent [18]

Comparative Analysis: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvation

Table 4: Decision Matrix for Solvation Methods in Protein Simulations

| Criterion | Explicit Solvent | Implicit Solvent |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | High - reproduces molecular details [15] | Moderate - approximations in physics [15] |

| Computational Cost | High - 80-90% of atoms are solvent | Low - no explicit solvent atoms |

| Sampling Speed | Slow - physical viscosity limits dynamics | Fast - reduced friction enables rapid transitions |

| Electrostatics | Natural screening with explicit waters | Approximated via dielectric continuum |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Explicit with water molecules | Missing or mean-field representation [15] |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Emergent from water behavior | Added via surface area terms [18] |

| Best Applications | Production simulations; parameter development; validation | Initial sampling; large conformational changes; quick scans |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | Engine for running simulations | GROMACS [16] [17], AMBER [17], NAMD, OpenMM [19] |

| Force Fields | Mathematical representation of atomic interactions | AMBER ff19SB [17], CHARMM36, OPLS-AA |

| Water Models | Represent explicit solvent molecules | TIP3P [16], SPC, OPC [17], TIP4P |

| Box Generation Tools | Create simulation boundaries | gmx editconf (GROMACS), tleap (AMBER), PACKMOL |

| Solvation Utilities | Add solvent to simulation | gmx solvate (GROMACS), solvate (NAMD) |

| Ion Placement Tools | Add ions for physiological conditions | gmx genion (GROMACS), autoionize (VMD) |

| Trajectory Analysis | Process and visualize results | gmx trjconv, VMD, PyMOL, MDAnalysis |

| Implicit Solvent Models | Continuum solvent approximations | Generalized Born [18], Poisson-Boltzmann [18] |

The setup of the simulation environment through appropriate PBC, box selection, and solvation methods forms the foundation for reliable molecular dynamics simulations of proteins. Periodic boundary conditions effectively eliminate edge artifacts while introducing periodicity considerations that must be managed during analysis. The choice of box geometry represents a balance between computational efficiency and physical requirements, with rhombic dodecahedra offering significant advantages for globular proteins. Most critically, the selection between explicit and implicit solvation involves fundamental trade-offs between accuracy and computational expense, with explicit solvent generally recommended for production simulations where molecular details of hydration are important [15], while implicit methods offer advantages for rapid conformational sampling. By carefully implementing these components according to the protocols outlined herein, researchers can establish robust simulation environments suitable for studying protein structure, dynamics, and function in biologically relevant contexts.

The Role of System Minimization and Equilibration in Achieving Stability

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of proteins, the processes of system minimization and equilibration are critical for achieving numerical stability, physiological realism, and accurate sampling of conformational states. These preparatory steps ensure that the simulated system transitions from an initial, often high-energy configuration to a stable, biologically relevant state before production simulations commence. The profound impact of these protocols on simulation outcomes is highlighted by studies showing that inadequate equilibration can introduce persistent artifacts, such as artificially increased lipid density and decreased hydration in ion channel pores, which subsequently distort functional interpretations [20]. Within the broader thesis of MD protocols for protein research, this application note details current methodologies and quantitative benchmarks for implementing robust minimization and equilibration procedures, leveraging recent advances in machine learning potentials and automated workflows to enhance efficiency and reliability.

Quantitative Data on Simulation Performance and Accuracy

Recent advancements in AI-driven simulations provide quantitative benchmarks for the accuracy and efficiency achievable with modern computational approaches. The performance metrics below illustrate how next-generation tools balance computational demands with ab initio accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Driven MD Simulation Methods

| Method | Key Innovation | Reported Accuracy (Force MAE) | Computational Efficiency Gain | System Size Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI2BMD [21] | AI-based ab initio biomolecular dynamics with protein fragmentation | 1.056 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ (large proteins) | >6 orders of magnitude faster than DFT | Proteins >10,000 atoms |

| BioEmu-1 [22] | Deep learning model for generating structural ensembles | Reproduces MD equilibrium distributions accurately | 10,000-100,000x fewer GPU hours than classical MD | Various protein systems |

Table 2: Energy and Force Calculation Accuracy Across Methods

| Calculation Method | Energy MAE (kcal mol⁻¹ per atom) | Force MAE (kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹) | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI2BMD Potential [21] | 0.038 (small proteins), 7.18×10⁻³ (large proteins) | 1.974 (small proteins), 1.056 (large proteins) | Density Functional Theory |

| Classical MM Force Field [21] | ~0.214 | ~8.392 | Density Functional Theory |

Experimental Protocols for System Preparation

Protocol 1: Standard Soluble Protein Equilibration

This protocol establishes a foundation for simulating soluble proteins using a combination of traditional MD engines and emerging AI potentials.

- System Building: Utilize CHARMM-GUI solutions, potentially automated through LLM-based agents like NAMD-Agent, to generate topologies and input files [23]. Solvate the protein in a TIP3P water box with 0.15 M NaCl to mimic physiological conditions.

- Energy Minimization:

- Objective: Relieve steric clashes and high-energy distortions from initial model building.

- Procedure: Apply 5,000 steps of steepest descent algorithm, targeting a energy gradient tolerance of 10.0 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹.

- Constraints: Gradually relax restraint schemes; start with heavy positional restraints (force constant of 10.0 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²) on protein backbone atoms.

- Thermal Equilibration:

- Objective: Gradually heat the system to the target physiological temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- Procedure: Employ a stepwise thermalization protocol in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature):

- 100 ps at 100 K

- 100 ps at 200 K

- 100 ps at 300 K

- Thermostat: Use Langevin dynamics with a damping coefficient of 1.0 ps⁻¹.

- Restraints: Maintain weak restraints on protein backbone (force constant of 1.0 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²).

- Density Equilibration:

- Objective: Achieve correct solvent density and system pressure.

- Procedure: Conduct 1-2 ns simulation in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) at 1 atm.

- Barostat: Use a Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston with oscillation period of 200 fs and decay time of 50 fs.

- Restraints: Release all positional restraints or maintain minimal restraints on Cα atoms only (force constant of 0.5 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²).

Protocol 2: Membrane Protein-Specific Equilibration

Specialized protocols are essential for membrane proteins to avoid artifacts such as inadequate pore hydration and excessive lipid penetration, as observed in Piezo1 channel simulations [20].

- Initial System Setup:

- Utilize CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder to construct an asymmetric lipid bilayer environment matching the protein's native membrane composition.

- Employ a multiscale approach: begin with Martini coarse-grained (CG) simulation for efficient pre-equilibration of the lipid bilayer around the protein.

- CG-to-All Atom Conversion:

- Reverse-map the equilibrated CG system to all-atom (AA) resolution.

- Critical Modification: During CG equilibration, apply positional restraints to lipid headgroups and the protein to prevent excessive lipid penetration into transmembrane pores [20].

- Minimization and Hydration:

- Perform extended minimization (10,000 steps) with strong restraints on protein and lipid atoms.

- Implement explicit pore hydration by manually inserting water molecules into channel pores before AA equilibration.

- Multi-Stage Equilibration:

- Stage 1: 500 ps NVT equilibration with heavy restraints on protein and lipid atoms (force constant 10.0 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²).

- Stage 2: 1 ns NPT equilibration with restraints on protein backbone and lipid headgroups.

- Stage 3: 5-10 ns NPT equilibration with no restraints, monitoring pore hydration and lipid distribution.

Protocol 3: AI-Accelerated Equilibration Workflow

Integrate next-generation AI tools to dramatically accelerate the exploration of conformational space and equilibration processes.

- Initial Structure Generation:

- Utilize BioEmu-1 to generate diverse starting conformational ensembles, providing thousands of protein structures per hour on a single GPU [22].

- Input experimental structures or AlphaFold2/3 predictions to sample folded, unfolded, and intermediate states.

- Rapid Energy Evaluation:

- Employ AI2BMD for ab initio accuracy force calculations at dramatically reduced computational cost [21].

- The system uses a fragmentation approach and machine learning force field to achieve DFT-level accuracy with near-linear scaling for systems exceeding 10,000 atoms.

- Enhanced Sampling:

- Leverage BioEmu-1's ability to accurately reproduce MD equilibrium distributions with 10,000-100,000x fewer GPU hours [22].

- Directly sample from the equilibrium distribution, bypassing lengthy conventional MD equilibration phases for specific applications.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: MD equilibration workflow with AI and quality control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Minimization and Equilibration

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Minimization/Equilibration |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM-GUI [23] | Web Interface | Automated generation of simulation-ready input files, solvation, ion placement, and membrane building |

| NAMD-Agent [23] | LLM Automation Agent | Automated interaction with CHARMM-GUI and generation of simulation scripts using natural language instructions |

| AI2BMD [21] | AI Potential | Machine learning force field providing ab initio accuracy for energy/force calculations with dramatically reduced computational time |

| BioEmu-1 [22] | Deep Learning Model | Generation of structural ensembles and equilibrium distributions, bypassing lengthy conventional MD equilibration |

| AMOEBA Force Field [21] | Polarizable Force Field | Explicit solvent modeling with improved electrostatic interactions for more accurate equilibration |

| Martini Coarse-Grained FF [20] | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Rapid pre-equilibration of complex systems, particularly membrane proteins, before all-atom refinement |

The critical role of system minimization and equilibration in achieving stability in protein MD simulations cannot be overstated. As demonstrated, inadequate protocols can introduce persistent artifacts that compromise functional interpretations, particularly in complex systems like membrane proteins [20]. The emerging generation of AI-enhanced tools—including BioEmu-1 for rapid structural sampling [22] and AI2BMD for accurate force calculations [21]—offers transformative potential to accelerate and improve these foundational steps. By implementing the detailed protocols and quality control measures outlined in this application note, researchers can establish robust simulation foundations that ensure physiological relevance and enhance the predictive power of their molecular dynamics investigations.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insights into protein structure, function, and dynamics. However, conventional MD is often limited by the timescales it can access, frequently failing to sample biologically relevant conformational changes that occur beyond the microsecond range [24]. This sampling problem arises from the rough energy landscapes of biomolecules, where many local minima separated by high-energy barriers trap simulations in non-functional states [25]. Enhanced sampling methods have been developed to overcome these limitations, enabling researchers to study rare events and calculate free energy landscapes with greater efficiency. This article focuses on three powerful techniques: Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD), Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD), and Metadynamics, providing detailed protocols for their application in protein research.

Methodological Foundations

The Sampling Problem in Molecular Dynamics

Biomolecular systems exhibit complex, multidimensional free energy landscapes characterized by numerous local minima and high barriers. Conventional MD simulations often become trapped in these local minima, preventing adequate sampling of all relevant conformational substates within accessible simulation timescales [25]. The core challenge lies in the fact that biologically important processes—such as protein folding, ligand binding, and conformational changes—typically involve crossing energy barriers that exceed the thermal energy (kBT) available in standard simulations. This limitation is particularly acute for proteins with rugged energy landscapes and intrinsically disordered peptides that explore diverse conformational states [26].

Enhanced Sampling Approaches

Enhanced sampling methods address this fundamental challenge through different strategic approaches. REMD (Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics) employs parallel simulations at different temperatures or Hamiltonians, allowing periodic exchanges that prevent trapping in local minima [25]. aMD (Accelerated Molecular Dynamics) applies a boost potential to smooth the energy landscape, lowering barriers while maintaining the physical pathway of transitions [26]. Metadynamics uses a history-dependent bias potential along predefined collective variables to gradually fill energy wells and drive exploration of new regions [27]. Each method offers distinct advantages depending on the system characteristics and research objectives, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Enhanced Sampling Methods

| Method | Fundamental Principle | System Size Suitability | Key Advantages | Primary Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REMD | Parallel simulations at different temperatures with exchange attempts [25] | Limited by number of replicas required [25] | Avoids pre-defining reaction coordinates; Provides temperature-dependent behavior | Computational cost scales with system size; Temperature selection critical |

| aMD | Addition of boost potential when system energy falls below threshold [26] | Suitable for small to medium systems [26] | No need for collective variables; Maintains physical pathway of transitions | Difficulties in proper reweighting for thermodynamics; Parameter sensitivity |

| Metadynamics | History-dependent bias potential along collective variables [27] | Depends on collective variable dimensionality [28] | Direct free energy surface reconstruction; Efficient barrier crossing | Choice of collective variables is critical; Risk of incomplete sampling if variables poorly chosen |

Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD)

Theoretical Basis and Implementation

REMD enhances conformational sampling by running multiple parallel MD simulations (replicas) at different temperatures, with periodic attempts to exchange configurations between adjacent replicas based on a Metropolis criterion [25]. The exchange probability between two replicas at temperatures Ti and Tj with potential energies Ei and Ej is given by:

[ P = \min\left(1, \exp\left[\left(\frac{1}{kB Ti} - \frac{1}{kB Tj}\right)(Ei - Ej)\right]\right) ]

This approach allows configurations to escape local energy minima through higher-temperature replicas while maintaining proper Boltzmann sampling at each temperature. The method has evolved beyond temperature-based exchanges to include Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD), where replicas differ in their potential energy functions, and multiplexed REMD (M-REMD), which combines multiple replicas per temperature level for improved sampling [25].

REMD Protocol for Protein Folding

System Preparation:

- Initial Structure: Obtain protein coordinates from PDB or generate using modeling software. For de novo folding studies, start from extended or random coils.

- Solvation: Solvate the protein in an appropriate water box (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) with minimum 10-15 Å padding from protein edges [29].

- Ionization: Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

REMD Parameters:

- Temperature Distribution: Select temperatures using approximately 10-20% exchange probability between adjacent replicas. For a 100-residue protein, typical temperature ranges span 300-500 K with 24-64 replicas [30].

- Exchange Attempt Frequency: Attempt exchanges every 1-2 ps for sufficient decorrelation between attempts.

- Simulation Length: Run each replica for 50-100 ns, monitoring convergence through RMSD and native contact analysis.

Execution and Analysis:

- Parallel Execution: Launch replicas simultaneously using MPI-enabled MD software (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD) [25].

- Convergence Monitoring: Track temperature walking patterns (each replica should visit all temperatures) and calculate potential energy distributions across replicas.

- Free Energy Calculation: Use the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method on the lowest-temperature replica data to compute free energy surfaces.

Table 2: REMD Parameters for Protein Folding Studies

| Parameter | Small Protein (<50 aa) | Medium Protein (50-100 aa) | Large Protein (>100 aa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Replicas | 24-32 | 32-48 | 48-64+ |

| Temperature Range (K) | 300-450 | 300-500 | 300-550 |

| Exchange Frequency (ps) | 1-2 | 1-2 | 2-4 |

| Simulation Length per Replica (ns) | 50-100 | 100-200 | 200-500 |

| Expected Exchange Rate | 15-25% | 15-25% | 10-20% |

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD)

Theoretical Framework

aMD enhances sampling by adding a non-negative boost potential to the system's original potential energy when it falls below a defined threshold [26]. The modified potential energy is given by:

[ V^*(r) = V(r) + V{\text{boost}}(r) ] [ V{\text{boost}}(r) = \begin{cases} 0 & V(r) \ge E{\text{thresh}} \ \frac{(E{\text{thresh}} - V(r))^2}{\alpha + (E{\text{thresh}} - V(r))} & V(r) < E{\text{thresh}} \end{cases} ]

where (E_{\text{thresh}}) is the threshold energy and (\alpha) is the acceleration factor determining the roughness of the modified landscape. aMD can be applied to dihedral angles only, the total potential energy, or both in the "dual-boost" approach, which is generally recommended for comprehensive sampling [26].

aMD Protocol for Peptide Conformational Sampling

System Setup:

- Force Field Selection: Choose appropriate force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) with recent dihedral parameter corrections [29].

- Solvation Model: Use implicit solvent (Generalized Born) for rapid sampling or explicit solvent for accuracy.

- Equilibration: Run conventional MD for 5-10 ns to equilibrate system and collect baseline potential energies.

Parameter Selection (Dual-Boost):

- Dihedral Boost Parameters:

- Calculate average dihedral energy ((\langle V{\text{dihed}} \rangle)) from equilibrated cMD

- Set tuning parameter: (\alphaD = \frac{1}{5} \times (3.5\ \text{kcal/mol}) \times N{\text{residues}})

- Set threshold: (E{\text{thresh,D}} = \langle V{\text{dihed}} \rangle + \alphaD)

- Total Boost Parameters:

- Calculate average total potential energy ((\langle V{\text{total}} \rangle)) from cMD

- Set tuning parameter: (\alphaT = \frac{1}{5} \times (1.0\ \text{kcal/mol}) \times N{\text{atoms}})

- Set threshold: (E{\text{thresh,T}} = \langle V{\text{total}} \rangle + \alphaT)

Simulation and Analysis:

- Production Run: Execute aMD simulation for 100-500 ns, monitoring boost potential to ensure adequate acceleration.

- Reweighting: Use cumulant expansion to second order or other reweighting schemes to recover unbiased distributions [26].

- Collective Variable Identification: Analyze trajectories using principal component analysis to identify dominant motions and relevant collective variables for subsequent metadynamics.

Diagram 1: aMD Simulation and Analysis Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in running accelerated molecular dynamics simulations, from initial setup through to analysis.

Metadynamics

Theoretical Principles

Metadynamics enhances sampling by adding a history-dependent bias potential constructed as a sum of Gaussian functions deposited along predefined collective variables (CVs) [27]. The bias potential at time t is given by:

[ V{\text{bias}}(S, t) = \sum{t' = \tauG, 2\tauG, ...} w \exp\left(-\frac{(S - S(t'))^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) ]

where S represents the collective variables, τG is the Gaussian deposition stride, w is the initial Gaussian height, and σ controls the Gaussian width. In well-tempered metadynamics, the Gaussian height decreases over time to ensure convergence:

[ w(t) = w0 \exp\left(-\frac{V{\text{bias}}(S(t), t)}{k_B \Delta T}\right) ]

where w0 is the initial height and ΔT is a bias factor parameter. Upon convergence, the bias potential provides an estimate of the underlying free energy surface: (F(S) = -\frac{T + \Delta T}{\Delta T} V_{\text{bias}}(S, t \to \infty) + C) [27].

Metadynamics Protocol for Protein-Ligand Binding

Collective Variable Selection:

- Distance-based CV: Center-of-mass distance between protein binding site and ligand.

- Hydrogen Bond CV: Number of protein-ligand hydrogen bonds.

- Interaction CV: Protein-ligand interaction energy.

PLUMED Configuration:

Parameters and Execution:

- Gaussian Parameters: Set initial height to 0.5-1.0 kJ/mol and widths (σ) to 10-20% of CV fluctuations from unbiased MD.

- Deposition Pace: Deposit Gaussians every 500-1000 steps (1-2 ps) to allow system relaxation.

- Grid Definition: Set GRIDMIN, GRIDMAX, and GRID_BIN for each CV to encompass relevant conformational space.

- Convergence Monitoring: Run until CVs show free diffusion and free energy estimate stabilizes.

Analysis and Validation:

- Free Energy Surface: Reconstruct from HILLS file using

sum_hillsutility. - Convergence Test: Perform block analysis on HILLS file to estimate errors.

- Reweighting: Use final bias potential to reweight trajectory and project free energy on additional CVs.

Table 3: Metadynamics Parameters for Different Application Scenarios

| Application | Recommended CVs | Gaussian Height (kJ/mol) | Gaussian Width (σ) | Bias Factor | Typical Simulation Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand Binding | Distance, H-bonds, coordination | 0.5-1.0 | 0.1-0.2 nm, 0.5-1.0, 0.1-0.2 | 10-20 | 100-500 ns |

| Peptide Folding | RMSD, secondary structure, radius of gyration | 1.0-2.0 | 0.05-0.1 nm, 0.1-0.2, 0.05-0.1 nm | 10-15 | 200-1000 ns |

| Enzyme Conformational Change | Dihedral angles, salt bridge distances | 0.5-1.5 | 0.1-0.3 rad, 0.05-0.1 nm | 15-25 | 500-2000 ns |

Diagram 2: Metadynamics Convergence Process. This diagram illustrates the progression of metadynamics simulations from initial trapping in a local minimum through to convergence, where the free energy surface is fully reconstructed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Enhanced Sampling Simulations

| Tool Name | Type | Key Features | Compatible Methods | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PySAGES [31] | Python Library | GPU acceleration, JAX-based, multiple backend support | aMD, Metadynamics, ABF | Custom CV development, machine learning integration |

| PLUMED [28] [27] | MD Plugin | Extensive CV library, multiple MD engine compatibility | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling, REMD | Standard enhanced sampling, free energy calculations |

| OpenMM [2] | MD Engine | GPU optimization, Python API | aMD, REMD | Rapid prototyping, custom simulation workflows |

| drMD [2] | Automated Pipeline | User-friendly, automated setup, minimal coding | Basic REMD, Metadynamics | Non-expert users, standardized protocols |

| GROMACS [25] | MD Engine | High performance, extensive analysis tools | REMD, Metadynamics | Large-scale production simulations |

Table 5: Force Fields and Solvation Models for Protein Simulations

| Force Field | Protein Types | Solvation Models | Enhanced Sampling Compatibility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER [29] [26] | General proteins, peptides | TIP3P, TIP4P, GB models | All methods (REMD, aMD, Metadynamics) | Recent dihedral corrections improve accuracy |

| CHARMM [29] | Membrane proteins, nucleic acids | TIP3P, CHARMM-modified | REMD, Metadynamics | Transferable between different system types |

| OPLS-AA [29] | Small molecules, ligands | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC | REMD, Metadynamics | Excellent for protein-ligand systems |

| Martini [27] | Large systems, membranes | Coarse-grained water | Metadynamics | Extended timescales, large conformational changes |

Integrated Application Protocol

Hierarchical Sampling Strategy

For complex biological questions, a hierarchical approach combining multiple enhanced sampling methods provides optimal results:

- Initial Exploration: Run aMD simulations (100-200 ns) to rapidly explore conformational space and identify relevant collective variables through PCA analysis [26].

- Focused Sampling: Apply metadynamics using 2-3 key CVs identified from aMD to quantify free energy landscapes [26].

- Validation: Use REMD to validate results without CV bias, particularly for temperature-sensitive processes.

Convergence Assessment

Quantitative Metrics:

- REMD: Monitor replica exchange rates (target: 15-25%) and temperature random walks.

- aMD: Check boost potential distribution and reweighting effectiveness.

- Metadynamics: Monitor CV diffusion and free energy estimate stability through block analysis [27].

Statistical Validation:

- Perform multiple independent runs from different initial conditions.

- Use block analysis to estimate statistical errors in free energy calculations.

- Compare results from different enhanced sampling methods for consistency.

This integrated approach leverages the complementary strengths of each method while mitigating their individual limitations, providing robust characterization of protein energy landscapes and dynamics for drug development and basic research applications.

A Step-by-Step MD Simulation Protocol for Protein Dynamics

The reliability of any Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the initial protein structure. Protein Structure Preparation and Pre-processing is a critical first step that transforms a raw, experimentally determined structure into a complete, physically plausible, and simulation-ready model [1] [32]. This process addresses common deficiencies in structural data, such as missing atoms, incorrect protonation states, and steric clashes, which, if left uncorrected, can lead to simulation artifacts and erroneous biological conclusions [33]. A meticulously prepared system provides a solid foundation for the subsequent stages of energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD, enabling the accurate study of protein dynamics, function, and interaction.

Background & Significance

Proteins are dynamic entities, and their biological function is often inextricably linked to their internal motions, which can range from local side-chain fluctuations to large-scale conformational changes [34] [35]. MD simulations provide a powerful in silico tool to observe these dynamics at atomic resolution, a feat that is often challenging for experimental techniques alone [34] [36].

Experimental structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), whether derived from X-ray crystallography or NMR, are the primary starting points for simulations. However, they are imperfect models of the native state. Key issues include:

- Missing Hydrogen Atoms: X-ray crystallography typically cannot resolve hydrogen positions due to their low electron density [35] [33].

- Incomplete Residues: Side chains and even entire loops may be disordered and missing from the electron density map [32].

- Unphysical Contacts: Crystal packing can sometimes introduce steric clashes not present in solution [35].

- Ambiguous Protonation States: The ionization states of residues like His, Asp, and Glu are not directly determined and must be assigned based on the local environment and pH [32] [33].

Proper pre-processing corrects these issues, ensuring the system is chemically accurate and energetically relaxed before the simulation begins. This step is crucial for studying phenomena like allosteric regulation and the functional impact of mutations, where accurate baseline dynamics are essential [34] [37].

Core Principles and Data

The preparation workflow is governed by several core principles aimed at creating a system that closely mimics the protein's native physiological environment. The key input is a protein structure file, most commonly in PDB format, obtained from the RCSB database [1] [38]. The choices made during preparation, such as the force field and water model, are critical and should be consistent with the intended MD engine and research question.

Table 1: Essential File Formats in Protein Structure Preparation

| File Extension | Description | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| .pdb | Standard Protein Data Bank format; contains atomic coordinates. | Initial input structure; archival format. |

| .gro | GROMACS format; contains atomic coordinates and velocities. | Primary coordinate file for GROMACS simulations [1]. |

| .top / .itp | Topology file; defines molecules, atom types, bonds, and force field parameters. | Molecular description for the simulation engine [1] [38]. |

| .mdp | Molecular dynamics parameters file; contains simulation control parameters. | Input for grompp to define simulation type (e.g., energy minimization) [1]. |

Table 2: Commonly Used Force Fields and Water Models

| Force Field | Characteristics | Commonly Paired Water Model |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM27/36/FF14SB | All-atom; accurate for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids; includes CMAP correction for proteins [38] [37]. | TIP3P, TIP4P |

| AMBER (ff99SB, ff14SB) | All-atom; widely used for proteins and DNA; known for good balance of secondary structure stability [38]. | TIP3P, SPC/E |

| OPLS-AA/L | All-atom; optimized for liquid properties and protein thermodynamics [35]. | SPC/E, TIP4P |

| GROMOS (54a7, 45a3) | Unified atom (hydrogens not explicitly on aliphatic carbons); computationally efficient [38]. | SPC |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for protein structure preparation, integrating the key steps and file types.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for preparing a protein system for MD simulation using the GROMACS suite, a robust and widely used open-source tool [1] [38].

Obtaining and Pre-processing the Initial Structure

- Retrieve Structure: Download your protein of interest from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) [1] [38].

- Visual Inspection: Use a molecular visualization tool like PyMol, VMD, or Rasmol to inspect the structure for overall topology, the presence of ligands, ions, and crystallographic waters [1] [35].

- Structure Cleaning:

- Remove non-essential heteroatoms (e.g., crystallization agents, buffer molecules) that are not relevant to your biological question.

- Decide on the retention of crystallographic waters and ligands. Tightly bound waters in the active site may be functionally important and should be kept.

- A common command-line approach to remove HETATM records (which include most non-protein entities) is: [38]

- Check for residues listed under the "MISSING" comment in the PDB header, as these indicate atoms or whole residues not present in the experimental structure [38].

Generating Topology and Force Field Assignment

- Run

pdb2gmx: This critical GROMACS tool generates the topology, a post-processed structure file, and a position restraint file. [38]-f: Input PDB file.-o: Output processed structure file in GROMACS format (.gro).-p: Output topology file (.top).-water: Specifies the water model (e.g., tip3p, spc, spce).-ff: Selects the force field (e.g., charmm27, amber99sb-ildn, opls-aa).

- Force Field Selection: When executed,

pdb2gmxmay prompt you to select a force field if not specified in the command. The choice of force field is critical and should be based on the molecule type and current best practices [38]. - Output: This step adds missing hydrogen atoms and generates the molecular topology based on the chosen force field [1] [38].

Defining the Simulation Environment

- Create Simulation Box: Use

editconfto place the protein in a simulation box with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) to avoid edge effects. [1]-bt: Box type (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron, octahedron). A rhombic dodecahedron is often preferred as it approximates a sphere with minimal solvent molecules.-d: Distance (in nm) between the protein and the box edge. A value of at least 1.0 nm is recommended to avoid spurious self-interactions [1].-c: Center the protein in the box.

- Solvation: Use

solvateto fill the box with water molecules. [1] [35]-cp: Input configuration of the protein.-cs: Configuration of the solvent (e.g., spc216 is a pre-equilibrated box of SPC water).- The topology file (

topol.top) is automatically updated to include the added water molecules.

System Neutralization and Energy Minimization

- Add Ions: To neutralize the system's net charge and mimic physiological ionic strength, use the

geniontool. This requires a pre-processed run input file (.tpr). - Energy Minimization: This step relieves any residual steric clashes or strained geometry introduced during the setup process by finding the nearest local energy minimum.

- Create a parameter file (

em.mdp) specifying the energy minimization algorithm (e.g., steepest descent) and number of steps. - Run the preprocessor and energy minimizer: [35]

- The

-deffnmflag sets the default filenames for input and output files. - A successful minimization is indicated by a large negative potential energy and a maximum force (Fmax) below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Create a parameter file (

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Protein Preparation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software Suite | An open-source, high-performance MD simulation package used for all steps of preparation, simulation, and analysis [1] [38]. |

| CHARMM/AMBER/OPLS | Force Field | A set of empirical mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of the system [1] [38]. |

| PyMol / VMD | Visualization Software | Used for visual inspection of the initial and intermediate structures, and for rendering molecular graphics [1] [35]. |

| RCSB PDB | Database | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids, providing the initial input coordinates [1] [38]. |

| Schrödinger Maestro | GUI Software Suite | Provides a comprehensive, automated Protein Preparation Workflow for adding hydrogens, correcting bonds, filling loops, and optimizing H-bond networks [32] [33]. |

| tleap / Antechamber | Parameterization Tool | AMBERTools utilities for generating force field topologies and parameters for standard and non-standard molecules (e.g., ligands) [33]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-Based GUI | A web-based platform that simplifies the setup of complex simulation systems, including membrane proteins, and provides input files for multiple MD engines [23]. |

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the process of generating a molecular topology and selecting an appropriate force field is a critical step that fundamentally determines the accuracy and reliability of the simulation outcomes. The topology defines the physical properties and connectivity of all atoms within the system, while the force field provides the mathematical framework and parameters that describe the potential energy surface governing atomic interactions. For researchers investigating protein dynamics, folding, and interactions with ligands or other biomolecules, this setup phase establishes the foundation upon which all subsequent simulation data is built [1] [39].

The selection process requires careful consideration of the specific protein system, research questions, and available computational resources. Contemporary force fields have evolved significantly from their early predecessors, with ongoing developments focused on improving accuracy for diverse biological contexts, including intrinsically disordered regions, post-translational modifications, and complex multi-component systems [39]. This protocol provides a structured framework for navigating these critical decisions and implementing them using the GROMACS simulation suite, a robust and widely adopted tool in computational biophysics [1].

Theoretical Background

The Molecular Topology

A molecular topology file contains a complete description of all interactions within a molecular system [40]. It defines the fundamental identity of the molecule beyond its simple atomic coordinates. Specifically, it enumerates:

- Atoms: The elemental types and their specific force field assignments.

- Bonds: Covalent connections between atoms with their equilibrium lengths and force constants.

- Angles: Parameters for bond angles between every set of three connected atoms.

- Dihedrals: Torsional potentials around rotatable bonds, crucial for defining protein backbone and side-chain flexibility.

- Non-bonded interactions: Parameters for van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, including partial atomic charges and Lennard-Jones coefficients.