A Practical Guide to Explicit Solvent Molecular Dynamics for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Research

This comprehensive guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with foundational knowledge and advanced methodologies for performing molecular dynamics simulations with explicit solvent.

A Practical Guide to Explicit Solvent Molecular Dynamics for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Research

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with foundational knowledge and advanced methodologies for performing molecular dynamics simulations with explicit solvent. Covering everything from fundamental principles and system preparation protocols to force field selection, solvent model benchmarking, and simulation validation, this article synthesizes current best practices. It addresses critical challenges in achieving stable simulations and sufficient sampling, while highlighting the growing impact of machine learning interatomic potentials. The content emphasizes practical applications in predicting solvation free energies, ligand-protein binding, and other pharmaceutically relevant properties, enabling more accurate and reliable computational studies in biomedical research.

Why Explicit Solvent Matters: Fundamental Principles and Critical Applications in Biomolecular Simulation

The Critical Limitations of Implicit Solvent Models and When Explicit Solvent is Essential

Solvent models are a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, directly influencing the accuracy and reliability of predictions in structural biology and drug discovery. The fundamental choice lies between implicit models, which treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, and explicit models, which represent individual solvent molecules. While implicit solvation offers significant computational advantages, its approximations introduce specific, critical limitations that can compromise physical realism. This Application Note delineates the inherent constraints of implicit solvent models and provides clear, actionable guidance on scenarios where an explicit solvent representation is non-negotiable for scientifically valid results. The protocols herein are framed within a broader research methodology for conducting robust MD simulations with explicit solvent.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Limitations of Implicit Solvation

Implicit solvent models calculate the solvation free energy (ΔG_solv) by combining polar and non-polar contributions. The polar component is typically derived from continuum electrostatics calculations using the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation or the approximate Generalized Born (GB) model, while the non-polar component is often estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [1] [2]. The canonical GB equation, for instance, is expressed as:

[ \Delta G{solv} = -\frac{1}{2}\left(1-\frac{1}{\epsilon}\right)\sum{i,j}\frac{qi qj}{f{GB}(r{ij})} ]

where (f{GB}) is a function that incorporates the effective Born radii of atoms (i) and (j) and their separation (r{ij}) [2]. Although computationally efficient, this approach suffers from several fundamental shortcomings:

- Inaccurate Treatment of Non-Polar Interactions: Many implicit models use a simple SASA-term ((\Delta G_{np} = \gamma \cdot SASA)) to represent the complex non-polar contributions of cavity formation and van der Waals interactions. This simplification is prone to significant errors, as it fails to capture the detailed physics of dispersion and repulsive forces [3] [4].

- Neglect of Specific Solvent Effects: The continuum approximation inherently cannot capture specific, structured solute-solvent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, water bridges, and ion-specific effects. These interactions are critical for processes like molecular recognition and can alter conformational equilibria [1] [4].

- Over-simplification of Entropy and Viscosity: Implicit models lack the viscosity imposed by random collisions with explicit solvent molecules. This leads to accelerated conformational sampling but yields misleading kinetics. Furthermore, the entropic contributions of solvent molecules, particularly in the hydrophobic effect, are only coarsely approximated via SASA [1] [5].

Quantitative Benchmarking: Implicit vs. Explicit Solvent Performance

The theoretical limitations of implicit solvation manifest as quantifiable inaccuracies in simulations. The following tables summarize benchmark findings from comparative studies, highlighting the performance gap between implicit and explicit solvent models across various systems and properties.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Solvent Models on Solvation Free Energy Calculations

| Solvent Model Type | Representative Models | Accuracy vs. Experiment | Computational Cost (Relative) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit | TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P, OPC | High accuracy; considered the gold standard for solvation free energies [6] | 100x (Baseline) | High computational cost; requires extensive sampling and solvent equilibration [3] [2] |

| Implicit (GB/SA) | GB(OBC1/II), SASA | Lower accuracy; worse agreement with experiment than explicit models, sometimes substantially worse [6] | ~1x | Poor treatment of non-polar interactions; lack of specific solute-solvent effects [3] [1] |

| Implicit (PB/SA) | MMPBSA | Accuracy system-dependent; can be high but often parameterization-sensitive [4] | 10-50x (lower than explicit) | Computationally expensive for the polar component; same non-polar limitations as GB/SA [1] |

Table 2: Impact of Solvent Model on Conformational Sampling and Structural Properties (from Glycosaminoglycan Studies) [7] [8]

| Structural Property | Explicit Solvent (TIP3P, OPC) | Implicit Solvent (GB models) | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ring Puckering (IdoA2S) | Reproduces multiple puckering states (e.g., (^1)C(4), (^2)S(O)) | Poor reproduction of experimental puckering equilibria [7] | NMR data [7] |

| Global Structure (Rg, EED) | Stable, compact conformations with U-shaped curvature | Overly flexible, may not reproduce stable global folds [7] [8] | Analytical Ultracentrifugation, SAXS |

| Glycosidic Linkage Dynamics | Accurate sampling of (\Phi/\Psi) dihedrals | Altered torsional sampling due to lack of solvent friction and specific H-bonds [8] | Crystallographic data |

A critical, often-overlooked limitation of many machine-learned implicit solvent models is their training via force-matching. This approach determines potential energies only up to an arbitrary constant, rendering the models unsuitable for predicting absolute free energies, which are essential for calculating binding affinities or solvation free energies [3]. Novel approaches like the (\lambda)-Solvation Neural Network (LSNN) are being developed to overcome this by also matching derivatives with respect to alchemical variables, but this remains an active research area [3].

Essential Protocols for Explicit Solvent Simulations

For systems where implicit solvent models are inadequate, transitioning to an explicit solvent setup is essential. The following protocols provide a standardized framework for this process.

Protocol 1: System Building and Equilibration for Explicit Solvent MD

This protocol details the setup and minimization of a biomolecular system in explicit solvent, a prerequisite for stable production MD.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Force Field: CHARMM36m or AMBER14/GLYCAM06 (for carbohydrates). Select based on your biomolecule.

- Explicit Solvent Model: TIP3P, SPC/E, OPC, or TIP4P. TIP3P is a common default, but OPC may offer superior accuracy for polar systems [8].

- Software Suite: GROMACS or AMBER.

- System Builder: CHARMM-GUI or

tleap(AMBER). For neutralization and ion concentration. - Ion Parameters: All-atom ion parameters compatible with the chosen force field.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Solvation: Place the solute in an octahedral or rectangular periodic box with a minimum distance of 8.0 Å to 10.0 Å between the solute and the box edge [7] [9].

- Neutralization and Ion Concentration: Add sufficient counter-ions (e.g., Na(^+), Cl(^-)) to neutralize the system's net charge. Subsequently, add ion pairs to achieve the desired physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [8].

- Energy Minimization:

- Restrained Minimization: Perform initial minimization with positional restraints applied to the solute heavy atoms (force constant of 400-1000 kJ/mol/nm²) to relax any bad contacts in the solvent and ions. Use a steepest descent algorithm for 1,000-5,000 steps [7] [8].

- Unrestrained Minimization: Remove all restraints and perform a full minimization of the entire system until the maximum force is below a tolerance of 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm [8].

- System Equilibration:

- NVT Equilibration: Heat the system gradually from 0 K to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) over 50-125 ps using a weak-coupling algorithm (Berendsen) or a Nose-Hoover thermostat. Maintain positional restraints on solute heavy atoms [8].

- NPT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for an additional 50-200 ps at the target temperature and pressure (1 atm) using a barostat (Parrinello-Rahman). Restraints can be gradually reduced in this phase. This step ensures the correct solvent density is achieved.

Protocol 2: Weighted Ensemble Sampling for Rare Events

For biologically relevant processes that occur on timescales beyond the reach of conventional MD (e.g., protein folding, large conformational changes), enhanced sampling methods like Weighted Ensemble (WE) are essential. This protocol leverages the WESTPA software [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- WE Software: WESTPA 2.0.

- Progress Coordinate: Pre-defined collective variables from TICA or other dimensionality reduction methods.

- Propagator Interface: A flexible interface to run dynamics using any MD engine (OpenMM, GROMACS, etc.).

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Define Progress Coordinates: Identify a small number (1-3) of collective variables (CVs) that best describe the transition of interest (e.g., root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), or end-to-end distance). Use Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) on initial short simulations to identify the "slowest" modes [9].

- Segment Conformational Space: Discretize the progress coordinate space into bins. Walkers (simulation replicas) are spawned and managed within these bins.

- Run WE Simulation:

- Initialization: Launch an initial set of walkers from the starting state.

- Propagation: Run short segments of MD for each walker.

- Resampling: Periodically, walkers in underrepresented regions are split, while those in overrepresented regions are merged. This adaptively allocates computational resources to efficiently explore conformational space and capture rare events [9].

- Analysis: Use the WESTPA analysis suite to compute rate constants, pathways, and generate statistical weights for the sampled states, enabling the construction of a free energy landscape.

When is Explicit Solvent Essential? A Decision Workflow

The choice between implicit and explicit solvent is context-dependent. The following decision chart provides a practical guide for researchers.

As the workflow indicates, explicit solvent is non-negotiable in the following scenarios, many of which are critical in drug development:

- Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Calculations: The prediction of absolute binding free energies requires an accurate physical model of displacement of explicit water molecules from the binding pocket and the associated entropy changes, which continuum models handle poorly [6] [4].

- Systems with Structured Solvent: Processes involving water-mediated interactions (water bridges), metal ion coordination, or the study of solvent-filled cavities demand an explicit representation [7] [10].

- Highly Charged Biomolecules: The conformational dynamics of polyelectrolytes like glycosaminoglycans (e.g., heparin), DNA, and RNA are dominated by their interaction with water and a diffuse ion atmosphere. Implicit models have been shown to poorly reproduce their experimental structural properties [7] [8].

- Studies of Kinetics and Viscosity-Dependent Phenomena: Because implicit models lack viscosity, explicit solvent with Langevin dynamics or a similar thermostat is required to model realistic dynamics and kinetic rates [1] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software, Force Fields, and Solvent Models for Explicit Solvent MD

| Category | Item | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Suites | GROMACS | High-performance MD engine. Ideal for large-scale production runs on HPC clusters. | Steep learning curve but excellent performance and analysis tools. |

| AMBER | Comprehensive MD suite with extensive force fields. | Known for robust algorithms and strong support for biomolecules. | |

| OpenMM | Toolkit for MD simulations with GPU acceleration. | High flexibility and performance; used as a backend in other tools. | |

| System Building | CHARMM-GUI | Web-based platform for building complex simulation systems. | Simplifies the process of adding solvent, ions, and membrane bilayers. |

| Enhanced Sampling | WESTPA | Software for performing Weighted Ensemble (WE) path sampling. | Essential for simulating rare events like protein folding or ligand unbinding [9]. |

| Explicit Water Models | TIP3P | Standard 3-site water model. Common default in many force fields. | Good balance of speed and accuracy, but properties like diffusion can be elevated. |

| OPC / TIP4P | 4-site, higher-accuracy water models. | Better reproduction of experimental water properties; recommended for accurate solvation studies [8]. | |

| SPC/E | Extended simple point charge model. | Improved dielectric and dynamic properties over original SPC. | |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36m | All-atom force field for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. | Includes corrections for folded and disordered proteins. |

| AMBER (ff19SB, GLYCAM06) | Force fields for proteins and carbohydrates, respectively. | GLYCAM06 is the standard for simulating sugars and glycosaminoglycans [7]. |

In atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice of how to model the solvent environment is paramount. Implicit solvent models, which treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, offer computational efficiency but fail to capture the discrete, specific nature of solute-solvent interactions. Explicit solvent modeling, where each solvent molecule is represented individually, is essential for reproducing physicochemical phenomena that emerge from molecular-level interactions. This application note details how explicit solvent modeling captures three fundamental interactions—hydrogen bonding, microsolvation, and hydrophobic effects—that are critical for accurate simulations in pharmaceutical and materials research. By providing specific protocols and analysis methodologies, we equip researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these approaches in their investigation of solvation-driven processes.

Hydrogen Bonding: Structural Stability and Biomolecular Recognition

Quantitative Characterization of Hydrogen Bonds

Hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) are predominantly electrostatic interactions between a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative donor (X-H) and an electronegative acceptor atom (Y). In explicit solvent simulations, these interactions are captured through direct atomic contacts and their dynamics over time, providing critical insights into structural stability and molecular recognition processes that implicit models cannot adequately represent.

Table 1: Key Hydrogen Bond Types and Their Characteristics in Explicit Solvent Simulations

| H-Bond Type | Interaction Energy (kcal/mol) | Primary Stabilizing Component | Key Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (O-H⋯O, N-H⋯O) | 3-10 | Electrostatic | Geometric criteria (distance, angle), J-couplings [11] |

| NH-π | 1-4 | Electrostatic | NMR chemical shifts, upfield shifts, scalar couplings [11] |

| CH-π | 1-4 | Dispersion | Through-hydrogen bond J couplings [11] |

| OH-π | 1-4 | Electrostatic | NMR chemical shifts, DFT calculations [11] |

Recent experimental evidence confirms the significance of non-conventional H-bonds, such as NH-π interactions, which engage π electrons as acceptors. In an intrinsically disordered peptide (E22G-Aβ40), direct NMR detection revealed an NH-π bond between the amide proton of Gly22 and the aromatic ring of Phe20, characterized by an upfield chemical shift of the amide proton (−0.8 ppm) and a near-zero temperature coefficient—both indicative of a persistent interaction that shields the proton from solvent exchange [11].

Experimental Protocol: Detecting NH-π Hydrogen Bonds

Objective: Provide direct experimental evidence for NH-π hydrogen bonds in biomolecules.

Materials:

- Intrinsically disordered peptide (e.g., E22G-Aβ40)

- Fluorine-labeled amino acids for specific labeling

- Deuterated solvents for NMR spectroscopy

- Computational resources for MD and DFT calculations

Methods:

- Sample Preparation:

- Incorporate site-specific fluorine labels on aromatic residues (Phe, Tyr) via recombinant expression or chemical synthesis.

- Prepare peptide samples at 0.5-1 mM concentration in appropriate aqueous buffers.

NMR Spectroscopy:

- Acquire (^{15})N-(^{1})H correlation spectra to identify anomalous upfield chemical shifts in amide protons.

- Measure temperature coefficients of amide proton chemical shifts across 5-35°C range.

- Perform (^{19})F NMR experiments to monitor aromatic ring environmental changes.

- Detect through-hydrogen bond scalar couplings using appropriate NMR experiments.

Computational Validation:

- Perform MD simulations with explicit solvent to identify potential interaction sites.

- Conduct DFT calculations on peptide fragments to quantify interaction energies and predict NMR parameters.

- Correlate experimental chemical shifts with computed values for validated structures.

Analysis: The combination of upfield amide proton shifts, near-zero temperature coefficients, and correlated aromatic ring perturbations provides strong evidence for NH-π interactions. J-couplings across the hydrogen bond offer definitive confirmation [11].

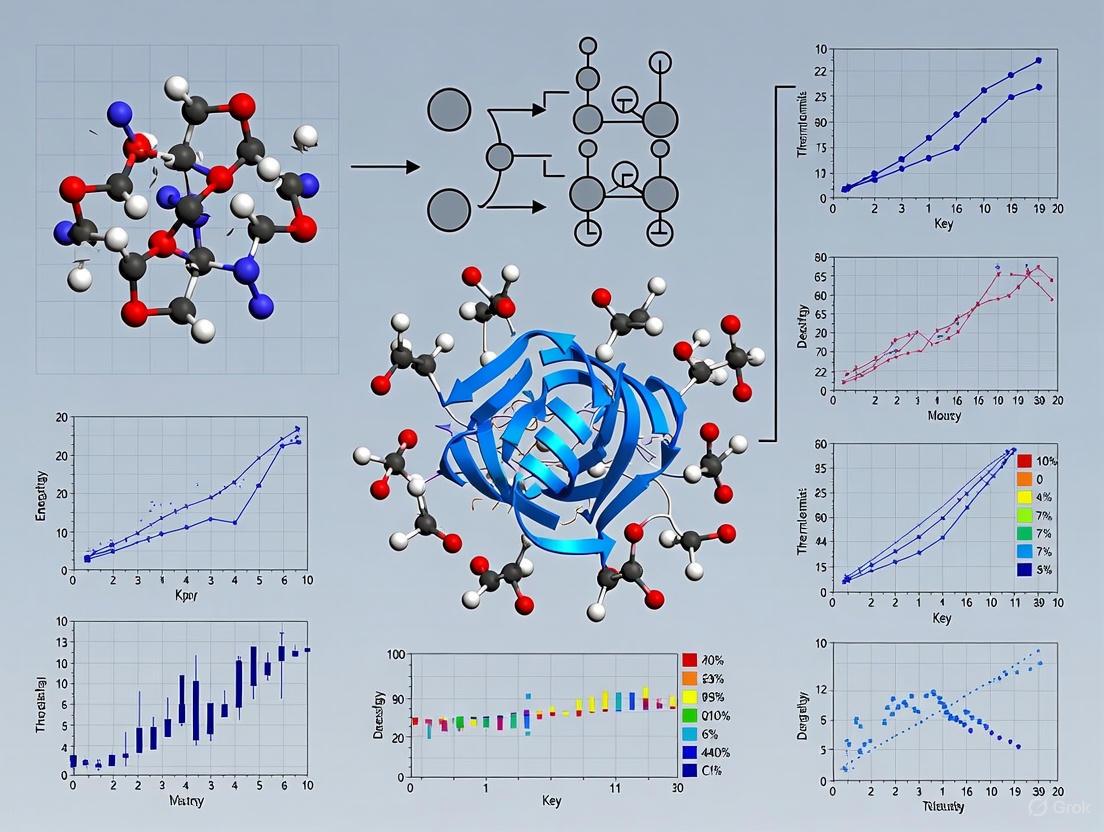

Figure 1: Workflow for experimental and computational detection of NH-π hydrogen bonds in peptide systems

Microsolvation: Local Solvent Structure and Dynamics

Quantifying Site-Specific Solvation

Microsolvation refers to the specific organization of solvent molecules around distinct sites of a solute, creating local hydration environments that significantly influence solute properties and reactivity. Explicit solvent modeling captures these specific arrangements, which continuum models inherently miss. The Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) provides a rigorous framework for quantifying these interactions by evaluating solvation thermodynamics on a spatial grid around the solute [12].

Table 2: GIST Thermodynamic Outputs for Microsolvation Analysis

| GIST Term | Physical Meaning | Computational Utility |

|---|---|---|

| ΔAsolv | Total solvation free energy | Overall stability of solute-solvent system |

| ΔEsw | Solute-solvent energy | Strength of direct interactions |

| ΔEww | Solvent-solvent energy | Cost of solvent reorganization |

| ΔStrans | Translational entropy | Restriction of solvent center-of-mass motion |

| ΔSorient | Orientational entropy | Restriction of solvent rotational freedom |

Protocol: Automated Quantum Chemical Microsolvation

Objective: Generate realistic solute-solvent clusters for quantum chemical calculations based on MD-derived thermodynamics.

Materials:

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS)

- GIST analysis tools (e.g., CPPTRAJ, in-house scripts)

- Quantum chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA)

- Python environment with required scientific libraries

Methods:

- MD Simulation Setup:

- Solvate the solute in explicit water (e.g., TIP3P, OPC models) in a cubic box with minimum 10 Å padding.

- Energy minimize the system using steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient.

- Equilibrate stepwise: NVT (50 ps) followed by NPT (100 ps) at target temperature and pressure.

- Run production MD for 10-50 ns with coordinates saved every 1-10 ps.

GIST Analysis:

- Process the trajectory to align all frames to a reference solute structure.

- Define a grid encompassing the solute with 0.5 Å spacing.

- Calculate thermodynamic quantities for each grid voxel using GIST equations.

- Identify high-occupancy hydration sites with favorable free energies.

Automated Water Placement:

- Sort hydration sites by interaction strength (ΔEsw).

- Select the N strongest hydration sites for explicit inclusion.

- Assign water orientations based on the average dipole vectors from MD.

- Generate input files for quantum chemical calculations.

Quantum Chemical Validation:

- Optimize the microsolvated cluster geometry using DFT (e.g., B3LYP/6-311++G(2d,p)).

- Calculate vibrational frequencies to confirm minima and compute IR/VCD spectra.

- Compare computed spectra with experimental data for validation.

Analysis: The success of the microsolvation model is validated by comparing computed properties (IR/VCD spectra, NMR chemical shifts) with experimental measurements. For Ace-Trp-N(n-Pr), this approach successfully identified mixed solvation states in DMSO and ACN, and dimerization in chloroform [13] [12].

Hydrophobic Effects and π-Stacking Interactions

Solvent-Driven Aggregation in Drug Formulation

Hydrophobic effects drive the association of non-polar solutes in aqueous solution to minimize the disruption of water's hydrogen-bond network. In drug delivery systems, these effects can lead to aggregation that reduces bioavailability. Explicit solvent simulations directly capture the water restructuring around hydrophobic groups and the resultant driving forces for association.

Table 3: Aggregation Propensity of Heteroaromatic Drugs in Deep Eutectic Solvent

| Drug Molecule | Average Aggregation Number | π-Stacking Energy (kcal/mol) | Interplanar Distance (nm) | Diffusion Coefficient (×10−12 m²/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allopurinol | 2.6 | -10 | 0.36 | 1.52 |

| Omeprazole | 4.3 | -32 | 0.47 | 1.07 |

| Losartan | 5.5 | -32 | 0.47 | 1.07 |

A combined MD and DFT study of heteroaromatic drugs in reline (a choline chloride/urea deep eutectic solvent) demonstrated how hydrophobic interactions and π-stacking drive aggregation. Losartan and omeprazole formed larger aggregates with stronger stacking energies compared to allopurinol, directly impacting their diffusion coefficients and potential bioavailability [14].

Protocol: Assessing Drug Aggregation in Solvent Environments

Objective: Characterize drug aggregation propensity and mechanisms in different solvent environments.

Materials:

- MD simulation software (GROMACS 5.1.2)

- GROMOS96 53A6 force field

- Drug and solvent molecular structures

- DFT software (Gaussian 09)

Methods:

- System Preparation:

- Optimize drug molecule geometries at DFT level (B3LYP/6-31+G*).

- Derive partial charges using CHELPG procedure.

- Generate MD topologies using Automated Topology Builder.

- Construct simulation box with 12 drug molecules randomly placed in solvent.

MD Simulation:

- Energy minimize the system to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibrate in NVT ensemble (5 ns, 300 K) using velocity-rescale thermostat.

- Equilibrate in NPT ensemble (5 ns, 1 atm) using Parrinello-Rahman barostat.

- Run production MD (100-200 ns) with 2 fs time step.

Aggregation Analysis:

- Calculate radial distribution functions (RDFs) between drug aromatic rings.

- Compute combined angular/radial distribution functions to identify π-stacking.

- Monitor cluster size distribution over trajectory.

- Determine interaction energies between drugs using DFT on dimer structures.

Transport Properties:

- Calculate mean squared displacement of drug molecules.

- Compute diffusion coefficients from Einstein relation.

- Analyze solvent structure around hydrophobic drug moieties.

Analysis: Larger aggregation numbers and stronger π-stacking energies correlate with reduced diffusion coefficients. Losartan shows both the largest aggregation number and slowest diffusion, indicating stronger self-association tendencies that could impact formulation strategies [14].

Figure 2: Protocol for assessing drug aggregation propensity in solvent environments using explicit solvent MD

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Explicit Solvent Studies

| Resource | Type | Function/Application | Example Sources/Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software | MD simulation engine | http://www.gromacs.org |

| AMBER | Software | MD simulation and analysis | http://ambermd.org |

| Gaussian | Software | Quantum chemical calculations | http://gaussian.com |

| CPPTRAJ | Tool | MD trajectory analysis | AmberTools distribution |

| GIST | Algorithm | Solvation thermodynamics analysis | In-house implementations, CPPTRAJ |

| TIP3P/SPC/E | Water Model | Explicit water representation | Standard MD force fields |

| DES (Reline) | Solvent | Drug solubilization studies | Choline chloride:urea (1:2) mixture |

| Chloroform-d1 | Solvent | NMR studies of aggregation | Commercial suppliers |

| ATB | Tool | Automated topology building | https://atb.uq.edu.au |

Explicit solvent modeling provides an indispensable framework for capturing the essential physical interactions that govern molecular behavior in solution. Through the protocols and analyses presented here, researchers can systematically investigate hydrogen bonding networks, microsolvation environments, and hydrophobic-driven aggregation—phenomena that are fundamental to drug design, materials science, and molecular biology. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with experimental validation and quantum chemical calculations creates a powerful multidisciplinary approach for understanding and predicting solvation effects across diverse chemical systems.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation of biological processes represents a critical tool for modern researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand molecular interactions at atomic resolution. When simulating processes in solution, a fundamental tension arises between physical accuracy and computational tractability. Explicit solvent models, which atomistically represent individual solvent molecules, provide superior physical accuracy by capturing specific solute-solvent interactions, hydrogen bonding networks, hydrophobic effects, and entropy contributions that continuum models cannot represent. However, this accuracy comes at a substantial computational cost, requiring thousands of solvent molecules and generating complex energy landscapes with nearly infinite conformational states.

The computational burden manifests in two primary dimensions: system size and sampling requirements. A typical explicitly solvated system contains hundreds to thousands of solvent molecules, dramatically increasing the number of atoms compared to gas-phase or implicit solvent simulations. Additionally, the introduction of numerous solvent degrees of freedom creates a flat energy landscape necessitating extensive sampling—typically requiring 10⁴–10⁶ individual structures—to reconstruct free energy surfaces. This dual challenge has traditionally limited the routine application of explicit solvent MD, particularly for processes involving rare events or complex conformational changes.

Quantitative Comparison of Computational Approaches

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Solvent Modeling Approaches in Molecular Dynamics

| Method | Physical Accuracy | Sampling Demands | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent | High (captures specific molecular interactions, entropy, hydrophobic effect) | Very high (10⁴–10⁶ structures typically required) | Extreme computational cost; limited sampling timescales | Processes dominated by specific solvent interactions (hydrogen bonding, ion pairing) |

| Implicit Solvent | Moderate (continuum dielectric approximation) | Low (well-defined potential energy surfaces) | Poor treatment of charged species; misses specific interactions | High-throughput screening; initial system preparation |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Potentially high (approaches QM accuracy) | Moderate (efficient after training) | Training data requirements; transferability concerns | Reactive processes in explicit solvent; enhanced sampling |

| QM/MM Hybrid | Variable (depends on QM region size) | High (but less than full QM) | Boundary artifacts; limited QM region size | Reactive processes requiring electronic structure detail |

Table 2: Sampling Efficiency Metrics Across Methodologies

| Methodology | Typical Time Step | Maximum Practical Simulation Time | Key Sampling Enhancements | Relative Speed vs. Explicit QM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Explicit Solvent | 1-2 fs | ~1 μs | Parallel tempering; Hamiltonian exchange | 10³–10⁶ × |

| Machine Learning Potentials | 0.5-1 fs | ~1 ms | Active learning; on-the-fly retraining | 10²–10⁴ × (after training) |

| Continuous Constant pH MD | 1-2 fs | ~100 ns | pH-based replica exchange | 10²–10³ × |

| Machine-Guided Path Sampling | 1-2 fs | Varies by system | Committor-based shooting moves; neural network guidance | 10 × vs. conventional MD |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Ten-Step System Preparation Protocol for Stable Explicit Solvent MD

For researchers preparing explicitly solvated biomolecular systems, we recommend the following standardized protocol to ensure stable production simulations. This protocol, adapted from PMC7413747, employs a gradual relaxation strategy to minimize initial forces and prevent simulation instability ["blow-up"] [15].

Step 1: Initial Minimization of Mobile Molecules

- Perform 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply strong positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol·Å²) to heavy atoms of large molecules

- Use initial coordinates as reference

- No constraints (e.g., SHAKE) should be applied

Step 2: Initial Relaxation of Mobile Molecules

- Execute 15 ps of NVT MD simulation with 1 fs timestep (15,000 steps total)

- Assign initial velocities via Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at target temperature

- Maintain heavy atom positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol·Å²)

- Apply necessary constraints (e.g., SHAKE for hydrogen atoms)

- Use weak-coupling thermostat with 0.5 ps time constant

Step 3: Initial Minimization of Large Molecules

- Perform 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply medium positional restraints (2.0 kcal/mol·Å²) to heavy atoms of large molecules

- No constraints should be applied

Step 4: Continued Minimization of Large Molecules

- Execute 1000 additional steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply weak positional restraints (0.1 kcal/mol·Å²) to heavy atoms of large molecules

- No constraints should be applied

Steps 5-9: Gradual Restraint Reduction

- Continue with sequential minimization and short MD simulations

- Gradually reduce positional restraints on large molecules

- Progressively increase conformational sampling

- Total: 4000 minimization steps and 40,000 MD steps (45 ps total) across first nine steps

Step 10: Density Equilibration

- Run unrestrained simulation until system density reaches plateau

- Monitor density to confirm stabilization before beginning production simulation

Machine Learning Potentials for Explicit Solvent Simulations

Machine learning potentials (MLPs) have emerged as powerful surrogates for quantum mechanical methods, offering near-QM accuracy at dramatically reduced computational cost. The active learning (AL) strategy for training MLPs to model chemical processes in explicit solvent involves a cyclic process of data generation, model training, and validation [10].

Initial Data Generation Strategy:

- Create two complementary training sets:

- Reacting substrates in gas phase or implicit solvent

- Systems with explicit solvent molecules

- For gas phase/implicit solvent: generate configurations by random atomic displacement

- For explicit solvent: use cluster models with solvent molecules at relevant positions

- Ensure minimum solvent shell radius exceeds MLP cut-off radius

Active Learning Cycle:

- Train initial MLP on small labeled dataset

- Propagate MD using current MLP

- Assess MLP stability through short MD simulations

- Select new structures for training using descriptor-based selectors

- Retrain MLP with expanded dataset

- Repeat until convergence

Key Selector Metrics:

- Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) descriptors

- Energy/force prediction variance (for committee models)

- Structural similarity metrics

Continuous Constant pH Molecular Dynamics in Explicit Solvent

The extension of continuous constant pH molecular dynamics to explicit solvent environments addresses critical limitations of implicit solvent models while maintaining computational feasibility through a hybrid explicit/implicit solvation approach [16].

Methodology Overview:

- Propagate conformational dynamics using explicit solvent model

- Compute solvation forces on titration coordinates using efficient GB model

- Implement pH-based replica exchange to enhance protonation/conformational sampling

- Employ λ-dynamics framework for continuous protonation state transitions

Protocol Details:

- Simulation length: 1 ns per replica sufficient for convergence

- Replica exchange attempts every 1-10 ps

- λ-particle mass: 5-20 amu·Å²

- Solvent shell radius: ≥10 Å for each titratable group

Key Advantages:

- Preserves native protein structure

- Provides realistic description of conformational flexibility

- Correctly models solvent-mediated ion-pair interactions

- Enables accurate pKa predictions (average absolute deviation: 0.53 from experiment)

Machine-Guided Path Sampling for Rare Events

Molecular self-organization processes often represent rare events that conventional MD struggles to sample adequately. Machine-guided path sampling integrates deep learning with transition path theory to discover mechanisms of molecular self-organization while dramatically enhancing sampling efficiency [17].

Algorithm Implementation:

- Committor Estimation: Model pB(x) = 1/(1 + e⁻q(x|w)) with neural network q(x|w)

- Transition Path Sampling: Select shooting points according to P(TP|x) = 2pB(x)(1-pB(x))

- Maximum Likelihood Training: Minimize loss function l(w|θ) = Σlog(1 + e^(sᵢq(xᵢ|w)))

- Symbolic Regression: Distill analytical expressions for human-interpretable mechanisms

Application Workflow:

- Initialize with limited unbiased MD

- Iteratively shoot trajectories from committor-informed points

- Update neural network committor model based on trajectory outcomes

- Apply symbolic regression to identify key physical observables

- Validate mechanism through independent simulations

Performance Metrics:

- 10× sampling speed-up versus conventional transition path sampling

- Quantitative agreement between predicted and sampled committors

- Transferability across thermodynamic states and chemical space

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Computational Methods for Explicit Solvent MD

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Key Features | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) | Machine learning potential | High data efficiency; active learning integration | Requires descriptor calculation; efficient linear algebra |

| Continuous Constant pH MD | pH-aware molecular dynamics | Hybrid explicit/implicit solvation; replica exchange | λ-dynamics implementation; GB model parameterization |

| Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) | Structural descriptors | Rotationally invariant; many-body interactions | Computational cost increases with system size |

| Transition Path Sampling | Rare event sampling | Bias-free; mechanism discovery | Requires order parameter definition; shooting move efficiency |

| Generalized Born Model | Implicit solvation | Computational efficiency; analytical forces | Limited accuracy for buried charges; parameterization sensitive |

| Replica Exchange | Enhanced sampling | Parallel tempering; Hamiltonian exchange | Resource intensive (multiple replicas); temperature spacing optimization |

Table 4: Performance Benchmarks for Explicit Solvent Methodologies

| System Type | Conventional Explicit MD | MLP-Accelerated | CPHMD | Path Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Protein (50-100 aa) | ~100 ns/day | ~1 μs/day (after training) | ~50 ns/day | ~10 transition paths/day |

| Ion Pair Association | ~10 μs required | ~100 ns required | N/A | ~1,000 iterations |

| pKa Prediction | N/A | N/A | 1 ns/replica | N/A |

| Membrane Protein | ~10 ns/day | ~100 ns/day | ~5 ns/day | ~5 transition paths/day |

The evolving landscape of explicit solvent molecular dynamics demonstrates a consistent trend toward smarter sampling rather than simply faster hardware. The integration of machine learning approaches with physical principles has created a new paradigm where computational resources are strategically allocated to regions of configuration space that contribute most significantly to the physicochemical process of interest. For drug development professionals, these advances translate to increasingly accurate predictions of solvation effects, pKa values, and binding affinities that directly impact compound optimization.

The future of explicit solvent MD lies in developing increasingly sophisticated multi-scale methods that combine the accuracy of explicit solvent representation with enhanced sampling techniques guided by physical intuition and machine learning. As these methods mature and become more accessible to non-specialists, they will undoubtedly become integral components of the drug discovery pipeline, providing unprecedented insights into molecular recognition and catalytic mechanisms in physiologically relevant environments.

Molecular dynamics (MD) with explicit solvent has become an indispensable tool in computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to model the behavior of biomolecules and their interactions with ligands in a biologically relevant, solvated environment. This article details the application notes and protocols for three critical areas where MD simulations provide profound insights: calculating solvation free energies, predicting the octanol-water partition coefficient (logP), and estimating ligand-protein binding free energies. Accurate predictions in these areas are crucial for optimizing the potency, pharmacokinetics, and safety profiles of small-molecule drug candidates, thereby streamlining the drug discovery pipeline [18] [19].

Application Note 1: Solvation Free Energy Calculations

Background and Purpose

Solvation free energy is a fundamental physicochemical property that quantifies the stability of a solute molecule in a solvent. It is a key determinant of a drug candidate's behavior, directly influencing solubility, permeability, and ultimately, its absorption and distribution within the body [20]. Calculating solvation free energies with high accuracy has been a long-standing challenge. Recent advances leverage machine-learned potentials (MLPs) to achieve accuracy close to first-principles quantum mechanics calculations, while remaining computationally feasible for drug-sized molecules [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Calculation Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different approaches for calculating solvation free energies.

Table 1: Comparison of Solvation Free Energy Calculation Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Features | Reported Accuracy | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alchemical with MLPs [20] | Alchemical transformation using a machine-learned potential. | Models entire system with MLP; avoids functional form limitations of empirical forcefields. | Sub-chemical accuracy (approaching QM level) | High |

| MM-PBSA [21] [22] | Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area. | End-point method using implicit solvation; good balance of accuracy and speed. | Accuracy depends on forcefield and system | Moderate |

| Alchemical with Empirical FF [23] | Alchemical transformation using empirical forcefields (e.g., GAFF). | Well-established protocol; relies on parameterized forcefields. | Good, but limited by forcefield accuracy | Moderate to High |

Detailed Protocol: Alchemical Free Energy Calculation with MLPs

This protocol outlines the procedure for computing solvation free energies using alchemical transformations and machine-learned potentials [20].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the small molecule solute.

- Place the solute in the center of a simulation box.

- Solvate the system with explicit solvent molecules (e.g., water for hydration free energy).

- Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration.

Alchemical Pathway Setup:

- Define the two end states of the transformation:

- State A (coupled): The solute fully interacting with the solvent.

- State B (decoupled): The solute with no interactions with the solvent (effectively in a vacuum).

- Introduce an alchemical parameter, ( \lambda ), which scales the Hamiltonian of the system from ( H0 ) (State B) to ( H1 ) (State A). The combined Hamiltonian is ( H(\vec{r}, \lambda) = \lambda H1(\vec{r}) + (1-\lambda)H0(\vec{r}) ).

- To avoid singularities when atoms overlap at intermediate ( \lambda ) states, implement a soft-core potential for the non-bonded interactions (Lennard-Jones and Coulombic). A Beutler-type softcore potential is commonly used [20].

- Define the two end states of the transformation:

Simulation and Sampling:

- Run molecular dynamics simulations at multiple intermediate ( \lambda ) values (typically 10-20 windows) to adequately sample the phase space along the alchemical path.

- For each window, perform equilibration followed by a production run to collect statistical data.

Free Energy Estimation:

- Use the simulation data to compute the free energy difference. The Thermodynamic Integration (TI) estimator is one rigorous method: [ \Delta G = \int0^1 \left\langle \frac{\partial H(\vec{r}, \lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \right\rangle\lambda d\lambda ] where ( \left\langle \cdots \right\rangle_\lambda ) denotes the ensemble average at a specific ( \lambda ).

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Alchemical solvation free energy workflow.

Application Note 2: logP Prediction

Background and Purpose

The n-octanol/water partition coefficient (logP) is a key metric of a molecule's lipophilicity. It profoundly impacts a drug candidate's absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties. According to Lipinski's Rule of Five, a logP value greater than 5 is often undesirable for orally administered drugs [21]. Experimental determination of logP can be costly and time-consuming, creating a strong demand for reliable computational models [21] [24].

Quantitative Comparison of logP Prediction Models

The performance of various logP prediction models can vary significantly depending on the dataset used for validation. The table below shows a comparison based on the diverse ZINC-707 dataset [21] [24].

Table 2: Performance of logP Prediction Models on the ZINC-707 Dataset

| Model | Type | Key Principle | RMSE (log units) | Pearson Correlation (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FElogP [21] | Structural Property-Based | Transfer free energy via MM-PBSA. | 0.91 | 0.71 |

| OpenBabel [21] | Not Specified | Not Specified | 1.13 | 0.67 |

| JPlogP [24] | Atom-Based Consensus | Distills knowledge from multiple predictors using atom-types. | High performance on pharmaceutical benchmark set | Not Reported |

| ACD/LogP (GALAS) [25] | Fragment-Based / Hybrid | Global model adjusted by local similarity to known compounds. | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| DNN Model [21] | Topology/Graph-Based | Deep neural networks trained on molecular graphs. | 1.23 | Not Reported |

Detailed Protocol: logP Prediction via Transfer Free Energy (FElogP)

The FElogP approach is based on the thermodynamic principle that logP is proportional to the free energy change of transferring a molecule from water to n-octanol [21].

Principle: The partition coefficient P is defined as the ratio of a compound's concentration in n-octanol to its concentration in water. The relationship to free energy is: [ -RT \ln 10 \times \log P = \Delta G{transfer} ] Therefore, logP can be calculated from solvation free energies in water and n-octanol: [ \log P = \frac{\Delta G{water}^{SFE} - \Delta G_{octanol}^{SFE}}{RT \ln 10} ] where ( \Delta G^{SFE} ) is the solvation free energy.

Solvation Free Energy Calculation via MM-PBSA:

- Perform MD simulations of the molecule solvated in a box of explicit water and, separately, in a box of explicit n-octanol.

- Use the MM-PBSA method to calculate the solvation free energy in each solvent from the simulation trajectories.

- In MM-PBSA, the solvation free energy (( \Delta G{solv} )) is decomposed into polar and non-polar components: [ \Delta G{solv} = \Delta G{polar} + \Delta G{non-polar} ]

- The polar component (( \Delta G_{polar} )) is calculated by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, which describes the electrostatic interaction between the solute and the continuum solvent.

- The non-polar component (( \Delta G_{non-polar} )) is associated with the cost of forming a cavity in the solvent and the van der Waals interactions at the solute-solvent interface [21].

logP Calculation:

- Input the calculated solvation free energies for water and n-octanol into the equation above to compute the final logP value.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 2: FElogP prediction workflow.

Application Note 3: Ligand-Protein Binding Free Energy

Background and Purpose

The binding free energy (( \Delta G_{bind} )) quantifies the strength of interaction between a ligand and its protein target. Accurate prediction of this affinity is a primary goal in structure-based drug design, as it allows for the in silico ranking and optimization of lead compounds, potentially reducing the need for costly and time-consuming synthetic efforts [26] [22] [23]. Methods range from less computationally demanding end-point techniques to more rigorous, pathway-based approaches.

Quantitative Comparison of Binding Free Energy Methods

The choice of method involves a trade-off between computational cost, ease of setup, and desired accuracy.

Table 3: Comparison of Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculation Methods

| Method | Type | Theoretical Basis | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM-PBSA/GBSA [22] | End-Point | Calculates energy difference between bound and unbound end-states using implicit solvation. | Faster than pathway methods; good for screening. | Large-scale virtual screening of similar compounds. |

| Double Decoupling (DD) [23] | Alchemical Pathway | Alchemically decouples ligand from protein and from solvent. | Rigorous; well-established. | Neutral ligands in various binding sites. |

| Attach-Pull-Release (APR) [23] | Physical Pathway | Pulls the physically coupled ligand out of the binding site along a defined coordinate. | No net charge change; avoids DD artifacts for charged ligands. | Ligands with clear exit pathways (e.g., surface sites). |

| Simultaneous Decoupling-Recoupling (SDR) [23] | Alchemical Pathway | Decouples ligand from protein while simultaneously recoupling it to solvent at a distance. | No net charge change; suitable for any binding site. | Charged ligands or ligands in buried binding sites. |

Detailed Protocol: Absolute Binding Free Energy with BAT.py

The BAT.py software automates Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations for diverse ligands, supporting DD, APR, and SDR methods [23].

Input Preparation:

- Provide protein structure file(s) (e.g., from a crystal structure or homology modeling).

- Provide ligand structure files for different poses. These can be generated by docking software or from multiple co-crystal structures.

System Setup with BAT.py:

- Ligand Parameterization: The tool uses OpenBabel for ligand protonation and AMBERTools to assign force field parameters (e.g., from GAFF).

- Protein Alignment: The input protein is aligned with a reference structure for consistent application of restraints.

- Dummy Atoms and Restraints: Define anchor atoms on the protein and ligand. Position dummy atoms to create a pull path (for APR) or for restraint potentials. These restraints are crucial to prevent the system from drifting and to define the bound and unstated states thermodynamically.

- Solvation and Ionization: The system is solvated in a box of explicit water molecules. Ions are added to neutralize the system and achieve the desired ionic strength.

Simulation and Free Energy Calculation:

- BAT.py automatically sets up and runs the necessary MD simulations for the chosen method (DD, APR, or SDR) using AMBER's pmemd.cuda.

- For the SDR method, the ligand is alchemically decoupled from the protein binding site while being simultaneously recoupled to the bulk solvent, all while the net charge of the system remains constant.

- The workflow involves sampling multiple windows or lambda states along the chosen pathway.

Analysis and Pose Ranking:

- BAT.py outputs the binding free energy for each input ligand pose.

- The pose with the most favorable (most negative) binding free energy is predicted as the most stable.

- The overall binding free energy for a ligand can be computed from the free energies of all considered poses (( \Delta G^\circi )) using: [ \Delta G^\circ{bind} = -RT \ln \sumi^{N{pose}} e^{-\beta \Delta G^\circ_{i}} ]

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 3: Absolute binding free energy calculation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Key Software and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER [23] | MD Simulation Suite | Facilitates molecular dynamics simulations, free energy calculations, and system analysis. Includes pmemd.cuda for GPU acceleration. |

| BAT.py [23] | Automation Tool | Python package that automates Absolute Binding Free Energy calculations, integrating system setup, simulation, and analysis. |

| GAFF2 [21] | Force Field | Provides parameters for small organic molecules, essential for energy calculations in MD simulations. |

| Machine Learned Potentials (MLPs) [20] | Force Field | Offers a more accurate alternative to empirical forcefields by learning the quantum mechanical potential energy surface. |

| ACD/LogP [25] | LogP Predictor | Commercial software offering multiple algorithms (Classic, GALAS) for logP prediction from structure. |

| OpenBabel [23] | Chemical Toolbox | Hand chemical file format conversion and ligand protonation state preparation. |

| VMD [23] | Visualization & Analysis | Used for visualizing molecular structures, trajectories, and preparing simulation systems. |

Step-by-Step System Preparation and Simulation Protocols for Stable Explicit Solvent MD

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with explicit solvent provide an atomistic view of chemical and biomolecular processes, capturing essential solute-solvent interactions that influence structure, dynamics, and mechanism. However, achieving stable and meaningful simulation trajectories requires careful preparation of the initial molecular system. This protocol details a comprehensive methodology for converting experimental structural data into simulation-ready systems for explicit solvent MD, with specific application to modelling chemical reactivity in solution.

The accurate representation of solvent effects is crucial for modelling solution-phase processes, as solvents modulate reaction rates, intermediate stability, and product distributions through specific solute-solvent interactions [10]. While implicit solvent models offer computational efficiency, they fail to capture key effects such as solvent pre-organisation and entropy contributions [10]. This protocol addresses the technical challenges of explicit solvation through systematic structure preparation and equilibration procedures.

From Experimental Data to Initial Structure

Experimental Structure Acquisition and Preparation

The foundation of reliable MD simulations begins with high-quality initial structures, typically obtained from experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy [15]. These structures often require preprocessing before they can be used in simulations:

- Add missing atoms/residues: Complete incomplete regions using homology modeling or loop prediction algorithms

- Remove experimental artifacts: Eliminate crystallographic ligands, molecular tags, and packing effects not relevant to the solution state

- Protonation state assignment: Add hydrogen atoms with appropriate protonation states for the simulated pH conditions using tools like PROPKA

- Structural validation: Verify bond lengths, angles, and stereochemistry against known geometric parameters

For chemical systems involving reactive processes, initial structures may come from crystallographic data or quantum mechanical calculations of reaction intermediates and transition states [27].

Solvation Environment Selection and Setup

The choice of solvation model depends on the specific research question and computational resources:

Table: Solvation Approaches for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Approach | Description | Best Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) | Solute embedded in a periodic box of solvent molecules | Bulk solvent properties; long-range interactions | Computationally expensive; requires careful box size selection |

| Cluster Models | Solute surrounded by explicit solvent shell without PBC | Specific solute-solvent interactions; QM/MM studies | Surface effects at cluster boundary; limited long-range interactions |

| Multi-Shell Approaches | Combination of explicit inner shell with continuum outer shell | Balanced accuracy and efficiency | Complex parameterization; boundary artifacts possible |

For simulation boxes with PBC, ensure the box dimensions provide sufficient padding (typically ≥10 Å) between the solute and box edges to prevent artificial self-interaction. For cluster models used in QM/MM or machine learning potential approaches, the solvent shell radius should exceed the cut-off radius used in subsequent MD simulations to avoid artificial forces at the solvent-vacuum interface [10].

System Preparation Protocol

A robust, multi-step preparation protocol is essential for stabilizing explicitly solvated systems before production MD simulations. The following ten-step protocol adapts and extends established methodologies for biomolecular systems to chemical systems in solution [15]:

Ten-Step Preparation Protocol

Step 1: Initial minimization of mobile molecules

- Perform 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply strong positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų) to heavy atoms of solute/large molecules

- Allow solvent molecules and ions to relax freely

- No constraint algorithms (e.g., SHAKE) should be applied

Step 2: Initial relaxation of mobile molecules

- Run 15 ps MD simulation with 1 fs timestep in NVT ensemble

- Maintain heavy atom restraints on solute (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų)

- Assign initial velocities via Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for target temperature

- Apply constraint algorithms (e.g., SHAKE) to hydrogen atoms

- Use weak-coupling thermostat with time constant of 0.5 ps

Step 3: Initial minimization of large molecules

- Perform 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply medium positional restraints (2.0 kcal/mol/Ų) to solute heavy atoms

- No constraint algorithms applied

Step 4: Continued minimization of large molecules

- Perform 1000 additional steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply weak positional restraints (0.1 kcal/mol/Ų) to solute heavy atoms

- No constraint algorithms applied

Step 5: Solute backbone/skeleton minimization

- Perform 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization

- Apply strong positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų) to backbone heavy atoms only

- Allow side chains and functional groups to relax

- No constraint algorithms applied

Step 6: Solute side chain relaxation

- Run 10 ps MD simulation with 1 fs timestep in NVT ensemble

- Apply strong positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų) to backbone atoms only

- Allow side chains and functional groups to move freely

- Apply constraint algorithms to hydrogen atoms

Step 7: Full solute minimization

- Perform 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization

- Remove all positional restraints

- No constraint algorithms applied

Step 8: Full system relaxation

- Run 10 ps MD simulation with 1 fs timestep in NVT ensemble

- No positional restraints on any atoms

- Apply constraint algorithms to hydrogen atoms

Step 9: Density equilibration

- Run 10 ps MD simulation with 1 fs timestep in NPT ensemble

- Use weak-coupling barostat with pressure time constant of 2.0 ps

- Apply constraint algorithms to hydrogen atoms

Step 10: Production preliminary run

- Continue NPT simulation until system density stabilizes

- Monitor density plateau using moving average (variation < 1% over 5-10 ps)

- This step may require 50-100 ps depending on system size and complexity

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete system preparation workflow:

Application to Chemical Reactivity in Solution

Special Considerations for Reactive Systems

Modelling chemical reactions in explicit solvent presents unique challenges that require adaptations to the standard preparation protocol:

Solvent Shell Configuration: For reactive processes, the placement of explicit solvent molecules should facilitate specific solute-solvent interactions that influence reactivity. Molecular cluster growth algorithms and microsolvation protocols can systematically position solvent molecules around reactive centers [28]. The minimum solvent shell radius should exceed the cut-off radius used in training machine learning potentials to avoid artificial forces at the solvent-vacuum interface [10].

Transition State Solvation: When modelling reactions with known transition states, include solvent configurations that stabilize the polarized charge distribution at the transition state. This may require targeted sampling around the reactive center or the use of enhanced sampling techniques during preparation.

Ion Pair Stability: For reactions involving ion pairs or charged intermediates, as studied in Lewis acid-catalyzed substitutions [27], ensure the solvent box provides sufficient dielectric screening and that counterions are appropriately placed to prevent artificial electrostatic interactions across periodic boundaries.

Machine Learning Potentials for Reactive Systems

Machine learning potentials (MLPs) offer a promising approach for modelling chemical reactions in explicit solvent with quantum mechanical accuracy at reduced computational cost [10]. The preparation of training data for MLPs requires special consideration:

Table: MLP Training Strategies for Explicit Solvent Simulations

| Strategy | Protocol | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster-Based Training | Generate configurations with solute and explicit solvent shell | Access to high-level QM methods; efficient sampling | Limited long-range interactions; surface effects |

| Active Learning with Descriptor-Based Selectors | Iterative retraining using SOAP descriptors to explore chemical space | Data efficiency; comprehensive PES coverage | Complex implementation; requires careful selector design |

| Δ-Machine Learning | Train MLP to predict difference between semi-empirical and QM PES | Reduced training data requirements | Still requires baseline calculations at each MD step |

The active learning workflow for generating MLPs for chemical reactions in solution involves:

- Initial training set generation with random atomic displacements and relevant solvent configurations

- Iterative MD simulations with preliminary MLP to explore new configurations

- Selection of new training structures using descriptor-based selectors (e.g., SOAP)

- Retraining of MLP with expanded training set until convergence

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and their functions for preparing explicit solvent systems:

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Explicit Solvent Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Packages | Function in Preparation Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| System Building | PACKMOL [27], CHARMM-GUI, tleap | Solvation box generation; molecular packing |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian [27], ORCA, Q-Chem | Reference electronic structure calculations; transition state optimization |

| Molecular Dynamics | Amber, GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM | MD engine for equilibration and production |

| Machine Learning Potentials | ANI, PhysNet, SchNet, MACE [10] | Accelerated PES evaluation for enhanced sampling |

| Analysis & Visualization | VMD, MDAnalysis, PyMOL | Trajectory analysis; structure validation |

Validation and Quality Control

Stability Assessment Criteria

Before proceeding to production simulations, verify system stability using the following criteria:

- Density plateau: System density fluctuates around experimental value with <1% variation over 5-10 ps [15]

- Energy conservation: In NVE simulations, total energy drift < 0.01-0.05 kcal/mol/ps

- Temperature and pressure stability: Fluctuations within 5-10% of target values in NVT/NPT ensembles

- Structural integrity: Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of solute backbone stabilizes

- Solvent structure: Radial distribution functions resemble those of pure solvent

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- System "blow-up" (catastrophic forces): Return to earlier minimization steps with stronger restraints; check for atomic overlaps

- Failure to reach target density: Extend Step 9 and 10 simulations; verify pressure coupling parameters

- Solute denaturation/unfolding: Increase restraint strength in early stages; extend minimization phases

- Poor energy conservation: Reduce timestep; check constraint algorithm implementation

For reactive systems specifically, validate that the solvent environment appropriately stabilizes key intermediates and transition states through comparison with experimental solvation free energies or calculated vibrational spectra.

Accurate representation of electrostatic interactions is a cornerstone of reliable molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, directly influencing the predictive power of computational studies in drug design. The choice of charge model—the method for assigning partial atomic charges to molecules—is a critical decision point in force field selection. While traditional fixed-charge models like AM1-BCC have been the workhorse for years, newer approaches like the ABCG2 model and more computationally intensive QM/MM methods offer alternative paths with different trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and transferability. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of these methodologies, offering protocols and data-driven guidance for researchers conducting explicit-solvent MD simulations within the broader context of force field parametrization for drug discovery.

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

The performance of a charge model is ultimately measured by its accuracy in predicting key physicochemical properties. The most relevant benchmarks include hydration free energy (HFE), solvation free energy in organic solvents, and protein-ligand binding free energy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Charge Models for Hydration and Solvation Free Energies

| Charge Model | Test Set | Property | Performance (RMSE, kcal/mol) | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCG2 | FreeSolv (642 molecules) | Hydration Free Energy (HFE) | 0.99 | [29] [30] |

| AM1-BCC | FreeSolv (642 molecules) | Hydration Free Energy (HFE) | ~1.71 | [29] |

| ABCG2 | 895 solvent-solute systems | Solvation Free Energy (SFE) | 0.65 | [31] |

| ABCG2 | 11 drug-like molecules | Water/Octanol Transfer Free Energy | MUE < 1.00 | [32] [33] |

| QM/MM | 11 drug-like molecules | Water/Octanol Transfer Free Energy | MUE < 1.00 | [32] |

For solvation free energies, the ABCG2 model demonstrates a clear advantage over its predecessor, AM1-BCC, achieving chemical accuracy (RMSE < 1 kcal/mol) on the standard FreeSolv database [30]. Its performance is comparable to much more expensive QM/MM methods for predicting transfer free energies between water and octanol, a key property in estimating lipophilicity (logP) [32] [33].

Table 2: Performance in Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Charge Model | Force Field Combination | Test Set | Performance (RMSE, kcal/mol) | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCG2 | GAFF2/ABCG2 + AMBER99SB*-ILDN | 507 perturbations / 273 ligands | 1.38 | [29] |

| AM1-BCC | GAFF2/AM1-BCC + AMBER99SB*-ILDN | 507 perturbations / 273 ligands | 1.31 | [29] |

| ABCG2 | GAFF2/ABCG2 + AMBER14SB | 507 perturbations / 273 ligands | 1.39 | [29] |

However, when applied to the more complex environment of a protein binding pocket, the advantage of ABCG2 diminishes. Large-scale relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations show that GAFF2/ABCG2 does not outperform GAFF2/AM1-BCC, with both models showing statistically indistinguishable accuracy and ligand-ranking capabilities [29] [34]. This highlights a crucial principle: force field optimization for a specific property (like HFE) does not guarantee improved performance for other, even related, properties (like protein-ligand binding) [29].

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol 1: Applying Fixed-Charge Models (AM1-BCC & ABCG2)

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for parametrizing small molecules with fixed-charge models for use with the GAFF2 force field in explicit solvent MD simulations.

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Input Preparation and Optimization: Begin with a 2D or 3D structure of the small molecule in a format like MOL2 or SDF. Perform a gas-phase geometry optimization using semi-empirical (e.g., AM1) or ab initio (e.g., HF/6-31G*) quantum mechanical methods to obtain a reasonable starting structure [30] [35].

- Conformational Sampling (Recommended): Generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers. While both AM1-BCC and ABCG2 show smaller charge fluctuations across conformations than RESP charges, using multiple conformers for charge averaging can improve transferability [30] [36].

- Charge Assignment:

- For AM1-BCC, use the

antechambermodule from AmberTools with the-c bccflag [30]. - For ABCG2, apply the new bond charge correction (BCC) parameters developed for GAFF2. This typically involves using a customized version of

antechamberor another tool that implements the ABCG2 parameter set [30] [31].

- For AM1-BCC, use the

- Force Field Parameter Assignment: Assign the remaining GAFF2 parameters (bond, angle, dihedral, and van der Waals terms) using

antechamberandparmchk2[31] [35]. - System Building: Solvate the parameterized molecule in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water model). Add counterions to neutralize the system's total charge [37] [35].

Protocol 2: QM/MM-Based Charge Derivation (RESP-QM/MM)

This protocol describes a more rigorous approach for deriving charges that incorporate condensed-phase effects, suitable for high-accuracy studies where computational cost is secondary.

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- QM/MM Simulation Setup: Place the solute molecule (with a preliminary set of charges, e.g., from AM1-BCC) in an explicit solvent box. Set up a QM/MM simulation where the solute is treated at the QM level (e.g., DFT with a modest basis set) and the solvent is treated with a classical MM force field (e.g., TIP3P) [36] [32].

- Sampling and ESP Calculation: Run a relatively short QM/MM MD simulation to sample the solute's configuration space in the solvent. Collect multiple snapshots from this trajectory. For each snapshot, calculate the electrostatic potential (ESP) generated by the QM electron density and nuclei at the positions of the surrounding MM solvent atoms [36].

- Charge Fitting: Perform a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) fit for each snapshot, using the MM atoms as the grid points for the ESP matching. The final atomic charges are obtained by averaging the fitted charges over all collected snapshots [36] [32]. This method, as used in D-RESP and xDRESP, generates charges that inherently include polarization by the solvent environment [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Datasets for Charge Model Development and Validation

| Tool/Dataset Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Charge Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| AmberTools/AnteChamber | Software Suite | Automated parameterization of organic molecules. | The primary tool for applying AM1-BCC and ABCG2 charge models and GAFF2 parameters [30] [31]. |

| FreeSolv Database | Benchmark Dataset | Experimental and calculated hydration free energies for 642 molecules. | The golden-standard benchmark for validating HFE prediction accuracy [29] [30]. |

| OpenFE Dataset | Benchmark Dataset | Protein-ligand binding free energy data for 12 targets with 273 ligands. | Key benchmark for testing transferability to protein-ligand binding affinity prediction [29]. |

| MiMiC Framework | Software Framework | Multiscale modeling framework for advanced QM/MM simulations. | Enables advanced methods like D-RESP and xDRESP for dynamics-generated multipole moments [36]. |

| Cinnabar | Software Tool | Processing and analysis of free energy perturbation results. | Used to calculate absolute binding free energies from perturbation data for model validation [29]. |

The choice between ABCG2, AM1-BCC, and QM/MM charge models is not a matter of identifying a single "best" option, but of selecting the most appropriate tool for a specific research question and resource context.

- For High-Throughput Solvation and Lipophilicity Screening: The ABCG2 model is highly recommended. Its superior accuracy for HFE and water-octanol transfer free energies, combined with its low computational cost, makes it ideal for large-scale virtual screening and logP prediction in early-stage drug discovery [30] [32] [31].

- For Standard Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy Calculations: The AM1-BCC model remains a robust and validated choice. Given its comparable performance to ABCG2 in RBFE calculations and its extensive history of use, it presents a lower-risk option for production runs where the primary goal is ranking compound affinities [29] [34].

- For Maximum Accuracy in Condensed-Phase Studies: QM/MM-derived charges (e.g., RESP-QM/MM) should be considered for systems where electronic polarization is critical or for validating fixed-charge models, despite their high computational cost [36] [32]. Emerging methods like xDRESP, which dynamically generate atom-centered multipole moments during QM/MM simulations, represent the future for capturing complex electrostatics beyond fixed point charges [36].

A critical overarching insight is that exceptional performance on solvation properties does not automatically translate to improved protein-ligand binding affinity prediction [29]. Future improvements in binding free energy calculations may require simultaneous optimization of ligand and protein force fields for mutual compatibility, rather than optimizing ligand parameters in isolation.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a foundational tool for exploring biological processes at an atomic level. The choice of how to represent the solvent—the environment in which these processes occur—is a critical decision that directly impacts the outcome and biological relevance of the simulation [38]. While implicit solvent models offer speed, they cannot reproduce the microscopic details of the protein-water interface and often produce conformational ensembles that differ from those generated with explicit water [38] [39]. Consequently, explicit solvent models are the gold standard for accuracy, yet they dominate the computational cost of simulations [38]. This application note provides a structured benchmark and practical protocols for employing the most common explicit water models—TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P, TIP4PEw, OPC, and TIP5P—within a rigorous MD research framework, drawing on recent comparative studies.

Water Model Specifications and Theoretical Background

Explicit water models are empirical constructs designed to reproduce key bulk properties of water. They differ primarily in the number of interaction sites and the distribution of charges, which directly influences their computational cost and accuracy [38] [40].

Three-site models like TIP3P and SPC/E place charges on the three atomic nuclei. They are computationally efficient but offer a simpler representation of water's electrostatic potential [38]. Four-site models such as TIP4P, TIP4PEw, and OPC shift the negative charge from the oxygen atom to a dummy atom (M) located along the H-O-H bisector. This provides a more accurate description of the molecular quadrupole moment, improving the replication of bulk properties and electrostatic interactions at a higher computational cost [41] [40]. The Five-site model TIP5P uses two lone-pair sites to represent the electron density, further refining the electrostatic description [40].

The table below summarizes the fundamental parameters for the benchmarked models.

Table 1: Force Field Parameters for Common Explicit Water Models [38] [41]

| Parameter | TIP3P | SPC/E | TIP4P-Ew | OPC | TIP5P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-H Bond (Å) | 0.9572 | 1.00 | 0.9572 | 0.8724 | - |

| H-O-H Angle (°) | 104.52 | 109.47 | 104.52 | 103.6 | - |

| O-M Distance (Å) | - | - | 0.1250 | 0.1594 | - |

| qO (e) | -0.834 | -0.8476 | -1.04844 | -1.3582 | - |

| qH (e) | +0.417 | +0.4238 | +0.52422 | +0.6791 | - |

| LJ εOO (kcal/mol) | 0.1550 | 0.0653* | 0.16275 | 0.21280 | - |

| LJ σOO (Å) | 3.1536 | 3.1655* | 3.16435 | 3.1660 | - |

| # Interaction Sites | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

Note: SPC/E Lennard-Jones parameters are sometimes reported differently; values from a common source are shown for consistency. TIP5P parameters are omitted for brevity but are available in specialized reviews [40].

Benchmarking Performance Across Biological Systems

The performance of a water model is not universal but depends significantly on the specific biological system under investigation. The following benchmarks highlight system-dependent outcomes.

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and Protein-GAG Complexes

GAGs are highly charged, periodic linear polysaccharides whose interactions with proteins are heavily mediated by water, making solvent model choice particularly crucial [7] [42].

- Global Heparin Structure: For simulating a heparin dp10 oligosaccharide, the TIP5P and OPC models demonstrated the best agreement with experimental data for global descriptors like the radius of gyration and end-to-end distance [7].

- Protein-GAG Binding: In MD simulations of protein-GAG complexes (e.g., FGF2-Heparin, Cathepsin K-Chondroitin Sulfate), significant variations in binding poses and interaction descriptors were observed across different water models [42]. This emphasizes that the choice of solvent model can directly influence conclusions about binding mechanism and stability. Implicit solvent models (GB) generally failed to reproduce the same structural and dynamic features as explicit models in these systems [42].

Peptide and Protein Secondary Structure

The ability of a water model to correctly bias or not bias peptide folding is a key test of its utility in protein simulations.

- Peptide Folding with aMD: In accelerated MD simulations of various peptides (α-helical, β-hairpin, intrinsically disordered), the combination of the ff19SB force field with the OPC water model showed superior performance, particularly for intrinsically disordered peptides [43]. The widely used ff14SB/TIP3P combination exhibited a strong helical bias [43].