A Practical Guide to Setting Up Molecular Dynamics Simulations in GROMACS: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

This guide provides a comprehensive, structured approach for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to set up and execute molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using GROMACS.

A Practical Guide to Setting Up Molecular Dynamics Simulations in GROMACS: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive, structured approach for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to set up and execute molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using GROMACS. It covers foundational concepts, step-by-step methodologies, advanced optimization techniques, and rigorous validation protocols. By integrating the latest features from GROMACS 2025 releases, such as GPU-accelerated free-energy perturbation and automated physical validation, this article equips users with the knowledge to perform efficient and reliable simulations for biomedical research, including structure-based drug design and protein-ligand interaction studies.

Understanding GROMACS: Core Concepts and System Preparation

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computational technique that simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By iteratively solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, MD provides insights into dynamic processes at the atomic level that are often inaccessible through experimental methods alone [1] [2]. This approach allows researchers to follow the time evolution of molecular systems, capturing structural changes, conformational transitions, and interaction patterns that underlie biological function and molecular recognition.

GROMACS (GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations) is a highly optimized software package designed to perform molecular dynamics simulations, particularly focused on biomolecular systems such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [1]. Renowned for its exceptional performance and scalability, GROMACS has consistently ranked among the fastest molecular dynamics codes available, making it a preferred tool in both academic and industrial research settings [3]. The engine performs two primary types of calculations: molecular dynamics simulations to model system behavior over time, and energy minimization to identify stable low-energy configurations [1].

In the broader context of computational chemistry, GROMACS occupies an important position between quantum mechanical methods that provide high accuracy for small systems, and coarser-grained approaches that can handle larger systems but with reduced atomic detail [1]. This positioning makes it particularly valuable for studying biologically relevant macromolecules in aqueous environments, where the balance between computational efficiency and atomic resolution is crucial for addressing scientifically meaningful questions.

Theoretical Foundation of Molecular Dynamics

Fundamental Principles

The mathematical foundation of molecular dynamics in GROMACS centers on Newton's equations of motion for a system of N interacting atoms. The core equation governing atomic movements is expressed as:

[mi \frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{r}i}{\partial t^2} = \mathbf{F}_i, \;i=1 \ldots N]

where (mi) represents the mass of atom i, (\mathbf{r}i) its position, and (\mathbf{F}i) the force acting upon it [1]. These forces are derived as negative gradients of a potential energy function (V(\mathbf{r}1, \mathbf{r}2, \ldots, \mathbf{r}N)) that describes how atoms interact with each other:

[\mathbf{F}i = - \frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}i}]

The potential energy function encompasses various contributions including bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic forces) [1]. By numerically integrating these equations of motion in small time steps (typically 1-2 femtoseconds), GROMACS generates trajectories that depict how atomic positions and velocities evolve over time, effectively creating a "computational microscope" that reveals molecular behavior at picosecond to microsecond timescales.

Practical Considerations and Limitations

While powerful, molecular dynamics simulations employing GROMACS operate under several important approximations that users must acknowledge. First, the simulations are fundamentally classical, treating atomic motion according to Newtonian mechanics rather than quantum mechanics [1]. This approximation works well for many heavier atoms at physiological temperatures but becomes problematic for light atoms like hydrogen, where quantum effects such as tunneling may be significant. High-frequency vibrations (particularly bond stretches involving hydrogen atoms) exceed the classical treatment's validity at room temperature, necessitating correction methods or constraint algorithms [1].

Second, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation is applied, assuming electrons remain in their ground state during atomic motions [1]. This prevents the simulation of electron transfer processes or electronically excited states. Third, GROMACS utilizes empirical force fields that are inherently approximate and typically pair-additive, meaning they represent many-body effects like polarizability through effective pair potentials [1]. Finally, computational efficiency requires truncating long-range interactions using cut-off distances, though sophisticated algorithms like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) help mitigate artifacts from this approximation [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Approximations in GROMACS Molecular Dynamics

| Approximation | Description | Consequences | Common Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Mechanics | Treats atomic motion classically using Newton's equations | Fails for light atoms/high-frequency vibrations; no quantum effects | Constrain bonds; apply quantum corrections to energies |

| Born-Oppenheimer | Electrons remain in ground state during nuclear motion | Cannot simulate electron transfer or excited states | Use specialized methods for reactive systems |

| Empirical Force Fields | Parameterized potential functions | Accuracy limited by parameterization; pair-additivity | Choose appropriate force field; validate against experimental data |

| Truncated Interactions | Long-range interactions cut off at finite distance | Potential artifacts from missing long-range contributions | Use PME for electrostatics; larger cut-offs where feasible |

GROMACS Workflow: From Structure to Analysis

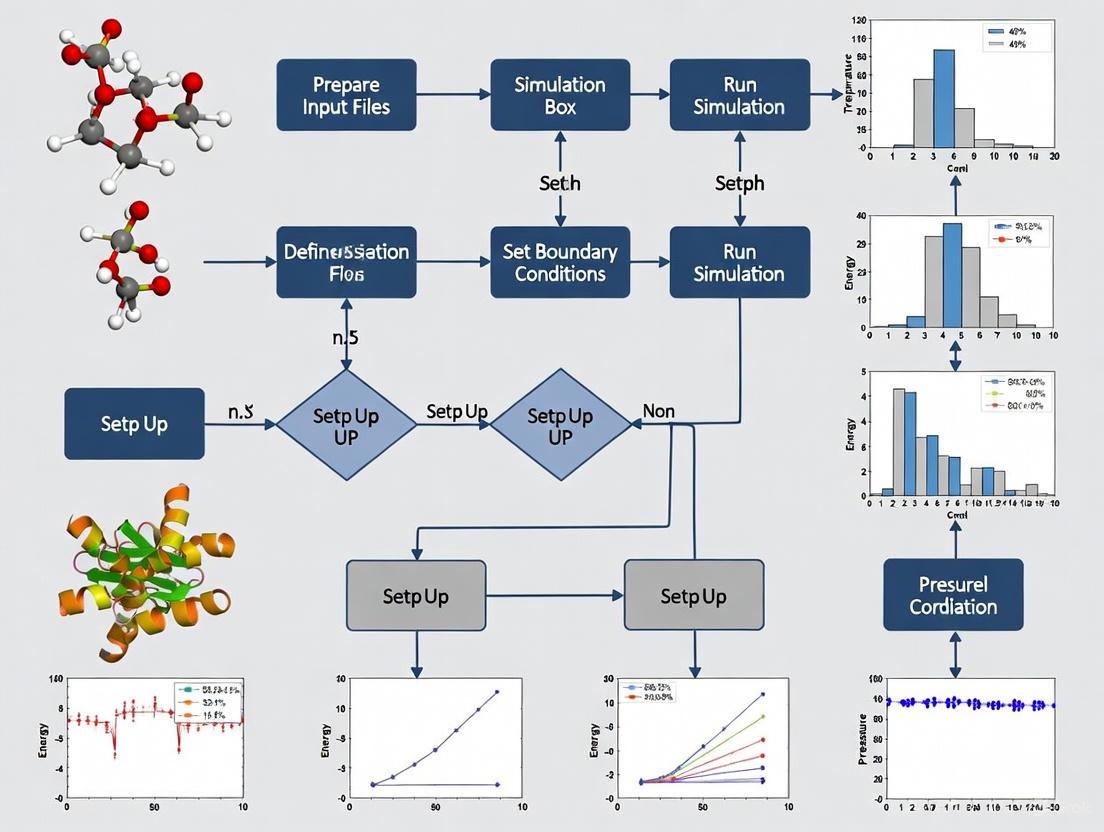

A complete molecular dynamics simulation in GROMACS follows a structured workflow with distinct stages, each serving a specific purpose in ensuring a physically meaningful and stable simulation [4] [2]. The schematic representation below illustrates this comprehensive process:

System Preparation and Solvation

The initial stage involves preparing the molecular system for simulation. This begins with obtaining or generating a starting structure, typically from experimental sources like X-ray crystallography or NMR, or through homology modeling [2]. The structure must be "cleaned" by removing non-protein components such as water molecules and ions that will be systematically reintroduced later [2]. GROMACS then generates a topology describing how atoms interact by assigning atom masses, bond parameters, and partial charges based on the selected force field [2].

The force field selection (e.g., OPLS/AA, AMBER, CHARMM) determines the mathematical forms and parameters used to calculate potential energies [2]. Following topology generation, the protein is centered in a simulation box, with common box types including rectangular boxes and more efficient rhombic dodecahedra that minimize solvent molecules while maintaining minimum image convention [2]. Finally, the system is solvated with water molecules (using models such as SPC, SPC/E, or TIP3P) and ions are added to neutralize the system's net charge and achieve physiological salt concentrations [2].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

With a fully assembled system, energy minimization addresses any residual steric clashes or unusual geometry that would create artificially high energy states [2]. This step employs algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient to find the nearest local energy minimum, effectively "relaxing" the structure before dynamics begin [1] [2]. The minimization proceeds until the maximum force falls below a specified tolerance (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) [2].

Following minimization, the system undergoes a two-stage equilibration process to gradually introduce dynamics while maintaining stability. First, NVT equilibration (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) allows the solvent to reorganize around the protein while restraining protein atomic positions, bringing the system to the target temperature (typically 300K) using thermostats like Berendsen or velocity rescaling [2]. Second, NPT equilibration (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) adjusts the system density to the target pressure (usually 1 bar) using barostats like Parrinello-Rahman, allowing the box size to fluctuate appropriately [2].

Production Simulation and Analysis

The production phase follows equilibration, continuing the simulation without positional restraints and using parameters identical to the final equilibration stage [2]. This phase collects the trajectory data used for subsequent analysis, with duration dependent on the scientific question and available computational resources. While short simulations (nanoseconds) may suffice for studying local flexibility, longer simulations (microseconds to milliseconds) are often necessary for capturing large-scale conformational changes or binding events.

Finally, trajectory analysis extracts scientifically meaningful information from the simulated dynamics. GROMACS includes numerous built-in analysis tools for calculating properties such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to monitor structural stability, radius of gyration to measure compactness, radial distribution functions to study solvation, and hydrogen bonding patterns to investigate molecular interactions [4] [5]. Additional analyses might include principal component analysis to identify essential dynamics, clustering to group similar conformations, and free energy calculations to quantify binding affinities or conformational preferences [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential GROMACS Components

Successful molecular dynamics simulations require careful selection of various computational "reagents" that define the physical model and simulation parameters. The table below outlines key components researchers must consider when designing GROMACS simulations:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for GROMACS Simulations

| Component | Function | Common Options | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines potential energy function and parameters | OPLS/AA, AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS | Compatibility with biomolecule type; validation against relevant experimental data |

| Water Model | Represents solvent water properties | SPC, SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P | Matching to force field; dielectric properties; computational cost |

| Temperature Coupling | Maintains constant temperature during simulation | Berendsen, velocity rescaling, Nose-Hoover | Stability vs. accurate ensemble generation |

| Pressure Coupling | Maintains constant pressure during simulation | Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman | Stability during equilibration; accurate fluctuation reproduction |

| Electrostatic Treatment | Handles long-range electrostatic interactions | PME, Cut-off, Reaction-field | Accuracy; computational requirements; system size |

| Constraint Algorithms | Manage high-frequency bond vibrations | LINCS, SHAKE | Enable longer time steps; maintain molecular geometry |

Advanced Features and Specialized Applications

Enhanced Sampling and Free Energy Calculations

Beyond conventional molecular dynamics, GROMACS supports advanced sampling techniques that accelerate rare events and enable free energy calculations [3]. Umbrella sampling applies positional restraints along a reaction coordinate to reconstruct potential of mean force (PMF) profiles, useful for studying processes like ligand unbinding or conformational transitions [3]. Free energy perturbations gradually transform one molecular species into another through alchemical pathways, allowing calculation of relative binding affinities or solvation free energies [3]. These methods expand GROMACS applications to drug design challenges where quantifying interaction strengths is essential.

Tabulated Interaction Functions

For researchers requiring specialized potential functions beyond standard force fields, GROMACS offers tabulated interaction functions [6]. Users can define custom potential functions for non-bonded interactions according to:

[V(r{ij}) = \frac{qi qj}{4 \pi\epsilon0} f(r{ij}) + C6 g(r{ij}) + C{12} h(r_{ij})]

where (f), (g), and (h) are user-defined functions specifying electrostatic, dispersion, and repulsive interactions respectively [6]. The software employs cubic spline interpolation with optimized coefficients to ensure smooth potential and force evaluation during simulation [6]. This flexibility enables simulations with novel functional forms or specific modifications to standard potentials for methodological development or specialized applications.

Performance Optimization Features

GROMACS incorporates sophisticated algorithms to maximize simulation performance while maintaining accuracy. The Verlet cut-off scheme uses neighbor searching with buffered pair lists that are updated intermittently, significantly reducing computational overhead [7]. Dynamic pair list pruning further optimizes performance by removing particle pairs that remain outside the interaction cut-off during the list's lifetime [7]. The software also implements cluster-based non-bonded kernels that process multiple particle interactions simultaneously, efficiently utilizing modern SIMD and SIMT hardware architectures in CPUs and GPUs [7]. These optimizations make GROMACS exceptionally performant, enabling researchers to simulate larger systems for longer time scales within practical computational constraints.

Protocol: Lysozyme Simulation in Water

To illustrate a complete GROMACS workflow, this protocol outlines the simulation of hen egg white lysozyme in aqueous solution, a common benchmark system [3] [2]. The process assumes GROMACS is installed and properly configured on the computing environment.

System Setup

Obtain and prepare the initial structure: Download the lysozyme structure (PDB code 1AKI) from the Protein Data Bank and remove non-protein atoms:

Generate topology and define simulation box:

Solvate and add ions:

Energy Minimization

Prepare input parameters (create em.mdp file with following content):

Run energy minimization:

Check minimization success by verifying the maximum force is below the specified tolerance (1000 kJ/mol/nm):

System Equilibration

NVT Equilibration (create nvt.mdp with appropriate parameters):

NPT Equilibration (create npt.mdp with appropriate parameters):

Monitor equilibration by checking temperature and pressure stability:

Production Simulation and Analysis

Run production MD:

Analyze trajectory for basic properties:

This protocol produces a stable, equilibrated lysozyme simulation suitable for investigating structural dynamics, flexibility, and solvation properties. The resulting trajectory serves as the foundation for more specialized analyses depending on research objectives.

GROMACS represents a sophisticated yet accessible platform for biomolecular simulation, offering researchers the ability to probe atomic-scale dynamics critical to understanding biological function and facilitating drug discovery. Its careful balance between physical accuracy and computational efficiency, coupled with extensive analysis capabilities, has established it as a cornerstone tool in computational chemistry and structural biology. The systematic workflow outlined in this article—from initial system preparation through production simulation and analysis—provides a robust framework for researchers to implement molecular dynamics studies addressing diverse scientific questions. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, GROMACS simulations will offer increasingly detailed insights into complex biological processes, bridging the gap between static structural information and dynamic functional understanding.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational biology, chemistry, and drug development, enabling researchers to study the structure, dynamics, and function of biomolecular systems. Among the various MD software packages available, GROMACS has consistently remained one of the most popular and high-performance choices, distinguished by its exceptional speed and comprehensive feature set. For researchers embarking on MD projects, particularly those new to the field, effectively navigating the extensive documentation and diverse community resources can be a daunting yet critical task for successful simulation outcomes. This guide provides a structured pathway through the GROMACS ecosystem, framed within the broader context of setting up and conducting molecular dynamics research, enabling both novice and experienced users to efficiently locate information and leverage community support.

The GROMACS Resource Ecosystem

GROMACS provides a multi-faceted support ecosystem comprising official documentation, interactive learning platforms, and community-driven forums. Understanding the purpose and interrelation of these components is the first step toward efficient problem-solving.

Table: Core Components of the GROMACS Resource Ecosystem

| Resource Type | Key Access Points | Primary Function | Target Audience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Official Documentation | manual.gromacs.org [8] [9] [10] | Comprehensive technical reference, installation guides, and user manuals | All users, from beginners to advanced developers |

| Interactive Tutorials | tutorials.gromacs.org [11]; mdtutorials.com/gmx/ [3] | Hands-on, step-by-step learning for specific simulation types | Beginners and users exploring new simulation methods |

| Community Support | gromacs.bioexcel.eu [12] | Q&A forum for troubleshooting and knowledge sharing | Users encountering specific problems or seeking advice |

| Official Website | www.gromacs.org [13] | News, release announcements, and central resource hub | All users tracking updates and general information |

The following diagram illustrates the recommended pathway for a researcher to navigate these resources, from initial setup to advanced problem-solving:

Official Documentation and Version Control

The official GROMACS documentation serves as the authoritative source for all technical information. The documentation is version-specific, ensuring instructions and parameters align with your installed software. The current version as of 2025 is the 2025 series, with documentation readily available online [8] [13]. The documentation is systematically organized into several key sections:

- Installation Guide: Provides comprehensive instructions for compiling and installing GROMACS on various platforms, including crucial guidance for enabling GPU acceleration via CUDA, which can dramatically speed up calculations [8] [14].

- User Guide: Offers introductory material and practical advice for performing effective simulations, making it an excellent starting point for beginners [10].

- Reference Manual: Delves into the theoretical background, algorithms, and implementation details for users who need a deeper understanding [8] [10].

- How-To Guides: Contain short, focused articles for accomplishing specific tasks [8].

A critical best practice is to always use the documentation that matches your specific GROMACS version, as commands and acceptable parameters can change between releases. The official documentation portal provides access to the documentation for all maintained versions, including the recent 2025, 2024, and 2023 series [9]. The GROMACS development team maintains a clear policy, typically keeping only the two most recent major versions under active maintenance. For instance, when the 2023 series was released, the 2021 series entered a state of limited, conservative maintenance [9]. This policy underscores the importance of using an up-to-date version for your research to ensure access to the latest features and critical bug fixes.

Interactive Tutorials and Learning Pathways

For researchers new to GROMACS or tackling a new type of simulation system, interactive tutorials provide the most effective learning pathway. These resources translate theoretical knowledge into practical, step-by-step protocols.

- Official GROMACS Tutorials: Hosted at

tutorials.gromacs.org, these are provided as interactive Jupyter notebooks that can be run directly in a web browser. This platform is regularly used in official training workshops and provides a uniform, accessible learning environment [11]. - Justin Lemkul's Tutorials: Available at

mdtutorials.com/gmx/, these are among the most widely used and respected tutorials in the community. They are meticulously designed to progress from fundamental to advanced topics and are being updated for GROMACS 2025 [3]. The sequence of learning is logically structured:- Lysozyme in Water: Covers the complete workflow for a standard soluble protein, including system preparation, solvation, energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD [3].

- Membrane Proteins (KALP15 in DPPC): Introduces the complexities of simulating lipid bilayers and embedded proteins [3].

- Protein-Ligand Complexes: Focuses on the critical steps of parameterizing and handling non-standard small molecules [3].

- Free Energy Calculations: Guides users through advanced techniques for calculating binding affinities and solvation free energies [3].

These tutorials are not just collections of commands; they provide crucial scientific context, explain the rationale behind each step, and offer troubleshooting advice, making them invaluable for a researcher's thesis work.

Community Engagement and Support

When documentation and tutorials are insufficient to resolve a problem, the GROMACS user community becomes an essential resource. The primary official forum for user support is the BioExcel GROMACS Forum (gromacs.bioexcel.eu) [12]. This platform hosts several dedicated categories:

- User Discussions: This is the main forum for asking and answering usage and troubleshooting questions. With thousands of posts, it is a rich repository of solved issues [12].

- Announcements: A channel for official news from the development team, including patch releases and security notices [12].

- Third-Party Tools: A curated space for sharing and discussing external tools, force fields, and scripts that complement GROMACS [12].

- Development Discussions: A forum for conversations about the internal codebase and future development of GROMACS [12].

Before posting a new question, it is considered good practice to thoroughly search the forum archives, as many common issues have already been addressed in detail. For example, a user inquiring about the availability of Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) would discover that it is not currently a standard feature in GROMACS, leading them to consider alternative enhanced sampling methods [14]. When asking a question, providing a clear description of your system, the exact commands used, relevant portions of your input files, and the associated error messages will significantly increase the likelihood of receiving a helpful response.

Experimental Protocol: A Standard MD Workflow

To contextualize the use of these resources, below is a generalized MD setup protocol for a protein, adapted from peer-reviewed literature and community tutorials [15] [3]. This workflow exemplifies the practical steps where a researcher would need to consult the specific resources detailed in previous sections.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Software for a Typical GROMACS Simulation

| Item | Function/Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure (PDB File) | Initial 3D coordinates of the biomolecule to be simulated. | Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) [15] |

| Force Field | A set of mathematical functions and parameters describing interatomic forces. Examples include CHARMM, AMBER, and GROMOS families. | Chosen during the pdb2gmx step; common ones are bundled with GROMACS [15] [3] |

| Molecular Topology File (.top) | Describes the molecular system (atoms, bonds, angles, charges, etc.) in the language of the force field. | Generated by pdb2gmx and updated in subsequent steps [15] |

| Parameter File (.mdp) | A set of all the control parameters that define the conditions of the simulation (e.g., temperature, pressure, timestep). | GROMACS documentation website or tutorial examples [15] |

| Water Model | Defines the explicit solvent molecules (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P) to solvate the protein. | Added during the solvate step [15] [3] |

| Counter Ions | Ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) added to neutralize the total charge of the system. | Added during the genion step [15] |

Computational Procedure

The logical flow of a simulation, from initial structure to production run, can be visualized as a series of preparation and simulation stages. This workflow is foundational to most research projects involving molecular dynamics in GROMACS.

System Preparation

- Obtain and pre-process protein structure: Download a PDB file and remove extraneous molecules like crystallographic water and unknown ligands unless they are critical to your study. Visualize the structure with a tool like RasMol [15].

- Generate topology and structure file: Use the

pdb2gmxcommand to create the topology (*.top) and GROMACS format structure (*.gro) files. This step requires selecting an appropriate force field (e.g.,ffG53A7was recommended for GROMACS v5.1 with explicit solvent; consult current tutorials for up-to-date recommendations). - Define the simulation box: Use

editconfto place the protein in a periodic box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) with sufficient margin (e.g., 1.0-1.4 nm) from the edges. - Solvate the system: Use

solvateto fill the box with water molecules. This automatically updates your topology file. - Neutralize the system: First, generate a binary input file (

*.tpr) usinggromppwith a simple parameter file (*.mdp). Then, usegenionto replace water molecules with counter ions to achieve a net zero charge.

Simulation Execution

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to remove any steric clashes and bad contacts in the initial structure. This is a critical step before heating the system.

- System Equilibration: This is a two-stage process to slowly bring the system to the desired thermodynamic state.

- NVT Ensemble: Equilibrate the system at constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature (e.g., 300 K) for about 50-100 ps, restraining the heavy atoms of the protein to their initial positions.

- NPT Ensemble: Further equilibrate the system at constant Number of particles, Pressure (e.g., 1 bar), and Temperature for another 50-100 ps, typically with weaker or no restraints.

- Production MD: This is the final, unrestrained simulation from which data is collected for analysis. The length of this simulation (nanoseconds to microseconds) depends on the biological process being studied [15] [3].

Trajectory Analysis

Mastering the landscape of GROMACS documentation and community resources is a foundational skill for any researcher employing molecular dynamics in their work. A strategic approach—starting with the official documentation for reference, progressing through structured tutorials for practical experience, and engaging with the community forum for targeted problem-solving—will significantly accelerate the learning curve and enhance the quality and reliability of simulation results. As GROMACS continues to evolve, with the 2025 series representing the current state-of-the-art, these resources remain dynamic, continually updated to incorporate new methodologies and best practices. By integrating these resources into a standardized simulation workflow, as outlined in the general protocol, researchers and drug development professionals can build a solid foundation for conducting robust and scientifically impactful molecular dynamics investigations.

Force Fields, Periodic Boundary Conditions, and Integrators

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with GROMACS, three foundational concepts form the essential framework for accurate and efficient modeling of biomolecular systems: force fields, periodic boundary conditions (PBC), and integrators. These components work synergistically to describe interatomic interactions, minimize finite-size artifacts, and numerically solve equations of motion. For researchers in drug development and structural biology, understanding the precise implementation and appropriate selection of these elements is critical for generating reliable simulation data that can inform experimental work and rational drug design. This protocol details the practical application of these concepts within the GROMACS environment, providing structured guidance for setting up robust MD simulations.

Force Fields: The Rulebook for Atomic Interactions

A force field is a mathematical expression and associated parameter set that describes the potential energy of a system of particles as a function of their nuclear coordinates [16]. In GROMACS, the potential functions are distinct from the parameters used within those functions, and care must be taken to use consistent sets validated together [16]. The functional form typically divides interactions into bonded terms (connecting atoms via chemical bonds) and non-bonded terms (describing interactions between all atoms, typically modeled with Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials) [17].

Table 1: Major Force Field Families Available in GROMACS

| Force Field | Type | Key Characteristics | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER (e.g., AMBER99SB-ILDN) [16] [18] | All-atom | Includes correction maps (CMAP) for improved backbone torsion; parameters suitable for proteins and nucleic acids. | All-atom simulation of proteins; requires -nocmap with pdb2gmx to disable CMAP if undesired. |

| CHARMM (e.g., CHARMM36) [16] [18] | All-atom | Extensive validation for proteins, lipids, nucleic acids; uses CMAP corrections. | Membrane proteins; lipid bilayers; requires specific non-bonded settings (e.g., force-switch modifier). |

| GROMOS (e.g., 54A7) [16] [18] | United-atom | Parametrized with twin-range cut-off; aliphatic hydrogens are not explicitly represented. | United-atom setups; use with caution with modern integrators due to potential density deviations [16]. |

| OPLS/AA [16] [18] | All-atom | Optimized for liquid simulations; transferable parameters. | Organic molecules; condensed phase systems. |

Application Protocol: Force Field Selection and Implementation

Protocol 1: Selecting and Implementing a Force Field in GROMACS

- Assess System Requirements: Choose a force field appropriate for your biomolecular system and the properties of interest. For general all-atom simulations, AMBER99SB-ILDN or CHARMM36 are recommended starting points [16]. Consistency between the force field's intended use and your simulation conditions is paramount.

- Obtain Topology: Use

gmx pdb2gmxto process your initial coordinate file (.pdb) and generate a molecular topology using your selected force field. For molecules not recognized by pdb2gmx, utilize specialized tools such as the Automated Topology Builder (ATB) for GROMOS, SwissParam for CHARMM, or antechamber/acpype for AMBER GAFF parameters [19]. - Verify Compatibility: Ensure your simulation parameters (.mdp settings) match the force field's intended use. For example:

- CHARMM36: Requires specific non-bonded settings:

constraints = h-bonds,cutoff-scheme = Verlet,vdwtype = cutoff,vdw-modifier = force-switch,rlist = 1.2,rvdw = 1.2,rvdw-switch = 1.0,coulombtype = PME,rcoulomb = 1.2, andDispCorr = no(for bilayers) [18]. - GROMOS-96: Was parametrized with a Lennard-Jones cut-off of at least 1.4 nm; ensure

rvdwis set to at least this value [16].

- CHARMM36: Requires specific non-bonded settings:

- Avoid Force Field Mixing: Never mix parameters from different force field families, as this leads to unphysical results and unreliable data [17].

Periodic Boundary Conditions: Simulating an Infinite System

Periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are employed to minimize edge effects in a finite simulation system [20]. The atoms are placed in a space-filling unit cell (the "box"), which is surrounded by translated copies of itself, creating an infinite periodic lattice that eliminates vacuum interfaces [20]. GROMACS uses the minimum image convention, meaning that for short-range non-bonded interactions, each atom only interacts with the single closest image of any other atom in the periodic lattice [20]. The program supports general triclinic boxes, which include special cases like cubes, rhombic dodecahedra, and truncated octahedra [20].

Table 2: Common Box Types and Their Properties in GROMACS

| Box Type | Image Distance | Relative Volume | Box Vectors | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic | (d) | (d^3) (100%) | (ax=ay=a_z=d); Angles=90° | Simple systems; crystals. |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron (xy-square) | (d) | (\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}d^3 \approx 0.71\,d^3) (71%) | (ax=d, ay=d, a_z=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}d); Angles=90° | Spherical solutes (e.g., globular proteins in water); minimizes number of solvent atoms. |

| Truncated Octahedron | (d) | (\frac{4}{9}\sqrt{3}d^3 \approx 0.77\,d^3) (77%) | Complex vector definitions [20] | Spherical solutes; slightly more isotropic than rhombic dodecahedron. |

Application Protocol: Implementing Periodic Boundary Conditions

Protocol 2: Setting Up Periodic Boundary Conditions

- Box Shape Selection: For simulating a approximately spherical solute (like a protein) in solution, use a rhombic dodecahedron box to reduce the number of required solvent molecules by approximately 29% compared to a cubic box, significantly lowering computational cost [20].

- Box Size Determination: The box must be large enough so that the cut-off radius (Rc) satisfies: [ Rc < \frac{1}{2} \min(\|\mathbf{a}\|, \|\mathbf{b}\|, \|\mathbf{c}\|) ] to prevent atoms from interacting with multiple images of the same particle [20]. Furthermore, the box length in any direction should exceed the length of the macromolecule in that direction plus twice the cut-off radius to prevent a solvent molecule from "seeing" both sides of the macromolecule [20].

- Box Creation and Solvation:

- Use

gmx editconfto define a box of appropriate size and shape around your solute molecule. - Use

gmx solvateto fill the box with solvent molecules (e.g., water).

- Use

- Trajectory Visualization and Analysis: Be aware that GROMACS stores particle coordinates within a brick-shaped volume for efficiency, even when using a triclinic box. Use

gmx trjconvto convert the trajectory for visualization or analysis in the desired unit-cell representation [20].

Integrators: The Engine of Molecular Dynamics

Integrators are numerical algorithms that solve Newton's equations of motion to update particle positions and velocities over time [21] [7]. The choice of integrator and its associated parameters (notably the time step dt) dictates the stability, accuracy, and efficiency of the simulation [21]. GROMACS offers a variety of integrators for different types of simulations, including dynamics, energy minimization, and other specialized calculations [21].

Table 3: Key Integrators and Energy Minimization Algorithms in GROMACS

| Algorithm | Type | Key Features | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| md (leap-frog) [21] | Dynamics (Integrator) | Default; efficient; sufficient accuracy for most production simulations. | Standard production MD. |

| md-vv (velocity Verlet) [21] | Dynamics (Integrator) | More accurate for Nose-Hoover/Parrinello-Rahman coupling; slightly more expensive. | Advanced sampling; NVE simulations. |

| sd (stochastic dynamics) [21] | Dynamics (Integrator) | Leap-frog stochastic dynamics; acts as a thermostat; friction set by tau-t. |

Simulating canonical ensemble (NVT). |

| steep (steepest descent) [21] [22] | Energy Minimization | Robust; follows the direction of the negative gradient. | Initial energy minimization. |

| cg (conjugate gradient) [21] [22] | Energy Minimization | More efficient than steepest descent for later minimization stages. | Refined energy minimization. |

Application Protocol: Configuring the Integrator

Protocol 3: Setting Up the Integrator for MD Simulation

- Select Integration Algorithm: For standard production MD, use

integrator = md(leap-frog) [21]. For constant NVE simulations or with advanced thermostats/barostats, considerintegrator = md-vv(velocity Verlet) for improved accuracy [21]. - Choose Time Step (

dt):- The time step is limited by the fastest motions in the system, typically bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms.

- A safe rule of thumb is to set

dtto 1-2 fs for all-atom simulations with bond constraints applied to hydrogen-heavy atom bonds (constraints = h-bonds) [17]. - To enable a larger time step (e.g., 4 fs),

mass-repartition-factorcan be used to scale the masses of the lightest atoms (typically hydrogens), though this modifies the dynamics [21].

- Set Simulation Length (

nsteps):- The total simulated time is

nsteps * dt. - Plan

nstepsbased on the biological process of interest (e.g., nanoseconds for local side-chain motions, microseconds to milliseconds for large conformational changes).

- The total simulated time is

- Remove Center-of-Mass Motion:

- Energy Minimization:

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GROMACS Simulations

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Topology (.top) [23] | Defines all interactions (bonded, non-bonded) for molecules in the system. | Generated by gmx pdb2gmx or external tools (ATB, CHARMM-GUI, acpype). Uses #include statements to incorporate force field and molecule definitions. |

| Molecular Structure (.gro/.pdb) [23] | Contains initial atomic coordinates, velocities, and box vectors. | The .gro format is native to GROMACS and can store velocities. |

| MD Parameters (.mdp) [23] | Configuration file specifying all simulation parameters (integrator, temperature, pressure, cut-offs, etc.). | A sample mdp file is provided in the GROMACS documentation as a starting point. |

| Run Input File (.tpr) [23] | Portable binary containing all information needed to run a simulation. | Generated by gmx grompp, which processes the .gro, .top, and .mdp files. This is the input for gmx mdrun. |

GROMACS Distribution share/top dir [19] |

Contains force field parameter files (.itp), atom type definitions, and default parameters (e.g., vdwradii.dat). |

Files can be customized by placing a modified copy in the working directory, which overrides the default. |

The foundation of a reliable molecular dynamics (MD) simulation in GROMACS lies in the meticulous preparation of initial structures. This protocol provides a standardized, step-by-step methodology for converting experimental Protein Data Bank (PDB) files into simulation-ready coordinate and topology files. The procedures outlined herein cover structure preprocessing, force field selection, topology generation, system solvation, and ion neutralization—critical steps ensuring physical accuracy and simulation stability. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide establishes a robust workflow for preparing biomolecular systems, forming an essential component of a comprehensive MD simulation framework.

Molecular dynamics simulations serve as a powerful computational tool for studying biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function at atomic resolution. The initial setup phase, particularly the preparation of accurate coordinate and topology files, profoundly influences simulation outcomes and their biological relevance [15]. The process transforms experimental structural data from PDB files into a computational model that incorporates appropriate atomic interactions through empirically-derived force fields.

The GROMACS simulation package, renowned for its computational efficiency and comprehensive toolset, requires specific file formats and system definitions to function optimally [24]. This protocol addresses the conversion pipeline, emphasizing the critical decisions researchers must make regarding force field selection, protonation states, and system neutralization—factors that collectively determine the physical fidelity of the resulting simulation.

Table 1: Essential computational tools and files for MD system preparation

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Files | PDB (.pdb), GROMACS format (.gro) | Store atomic coordinates and system structural information [23] |

| Topology Files | GROMACS topology (.top), Include topology (.itp) | Define molecular parameters, bonding, force field, and atomic charges [15] |

| Simulation Parameters | Molecular Dynamics Parameter file (.mdp) | Specify simulation conditions and algorithms [15] |

| Visualization Software | RasMol, Avogadro | Visual inspection of protein structure and graphics rendering [15] |

| Text Editors | Gedit, vi, emacs | Edit PDB files, update topology files, and modify input parameter files [15] |

| Force Field Databases | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA, GROMOS | Provide parameter sets for bonded and non-bonded interactions [25] |

Theoretical Framework: Molecular Dynamics and Force Fields

Molecular Dynamics Fundamentals

MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system: [ mi\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} = \mathbf{F}i ] where (mi) is the mass of atom (i), (\mathbf{r}i) its position, and (\mathbf{F}_i) the force acting upon it derived from the potential energy function (V) [7]. The velocity Verlet algorithm typically integrates these equations, progressing the system through discrete time steps (usually 1-2 fs) [17].

Force Field Composition

The potential energy function (V) (force field) encompasses both bonded and non-bonded interactions [17]:

[

V = V{\text{bonded}} + V{\text{non-bonded}}

]

[

V{\text{bonded}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} kb(r - r0)^2 + \sum{\text{angles}} k\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2 + \sum{\text{dihedrals}} k\phi[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)]

]

[

V{\text{non-bonded}} = \sum{i

Table 2: Common force fields available in GROMACS and their applications

| Force Field | Best Applications | Water Model Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER99SB-ILDN | Proteins, nucleic acids | TIP3P, SPC/E |

| CHARMM27 | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids | TIP3P (modified) |

| OPLS-AA | Organic molecules, proteins | TIP4P, SPC |

| GROMOS 54A7 | Biomolecular condensed phases | SPC |

Diagram 1: Complete workflow for preparing simulation-ready structures in GROMACS

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Initial Structure Acquisition and Preprocessing

Procedure:

- Obtain protein coordinates from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) [15]:

- Visually inspect the structure using molecular visualization software (e.g., RasMol) to identify non-protein components, structural anomalies, and missing residues.

- Remove heteroatoms and crystallographic water molecules that may interfere with subsequent solvation: Note: Waters are removed at this stage since the system will be explicitly solvated later in the protocol [24].

Force Field Selection and Topology Generation

Procedure:

- Execute the

pdb2gmxcommand to generate topology and processed coordinate files: - Select an appropriate force field when prompted. For proteins, AMBER99SB-ILDN or CHARMM27 are generally recommended [24] [17].

- Choose a water model consistent with the selected force field (e.g., TIP3P for AMBER, TIP4P for OPLS-AA) [25].

- Specify protonation states for histidine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and other residues with titratable groups. The

-interflag enables interactive selection [25]. - Verify the output files:

conf.gro: Processed coordinates in GROMACS formattopol.top: System topology with force field parametersposre.itp: Position restraint file (if needed)

System Solvation and Neutralization

Procedure:

- Define simulation box using

editconf: Note: The-d 1.4flag creates a 1.4 nm buffer between the protein and box edge, while-ccenters the protein [15]. - Solvate the system with water molecules using

solvate: - Generate preprocessed run input file for ion addition:

- Neutralize system charge by adding counterions:

Note: The

-neutralflag automatically adds sufficient ions to neutralize the system net charge [15].

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

Table 3: Troubleshooting common issues during structure preparation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

pdb2gmx fails with"atom not found" |

Missing atoms in input structure or non-standard residues | Use -missing flag to bypass or manually add missing atoms to PDB file [25] |

| System has net charge | Lack of counterions for charged biomolecules | Ensure gmx genion is executed with -neutral flag to add appropriate counterions [15] |

| Unphysical energiesduring minimization | Atom overlaps, incorrect protonation states, or inappropriate force field parameters | Verify protonation states, check for steric clashes, and ensure force field compatibility with molecule type [26] |

| Water moleculesinside hydrophobic core | Incomplete removal of crystallographic waters before solvation | Remove all HOH records from original PDB before running pdb2gmx [24] |

Expected Outcomes and Validation

Upon successful completion of this protocol, researchers will obtain the following essential files for GROMACS simulations:

- Final coordinate file (

protein_ions.gro): Contains the fully solvated and neutralized system with proper periodic boundary conditions. - Complete topology file (

topol.top): Includes all force field parameters, molecular definitions, and interaction potentials for the system. - Position restraint file (

posre.itp): Optional file for restraining heavy atoms during equilibration.

The resulting system should be characterized by zero net charge, appropriate dimensions to prevent artificial periodicity artifacts, and physically realistic protonation states at the desired simulation pH. The topology should correctly represent all bonded and non-bonded interactions according to the selected force field.

Applications in Drug Development

For drug development professionals, this structure preparation protocol enables the investigation of protein-ligand interactions through MD simulations. Proper topology generation is particularly crucial when incorporating small molecule therapeutics, which often require specialized parameterization using tools like CGenFF for CHARMM force fields or Antechamber for AMBER force fields [27]. The resulting simulation systems facilitate binding affinity calculations, allosteric mechanism studies, and structure-based drug design—all dependent on the initial structural accuracy established through this protocol.

Defining the Simulation Box and Solvation Models

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using GROMACS, proper system preparation is a critical foundation for obtaining physically meaningful and reliable results. Two of the most fundamental steps in this process are defining the simulation box and solvating the system. The simulation box establishes the periodic boundary conditions that mimic a continuous environment from a finite system, while solvation places the solute molecule in a biologically relevant solvent environment, typically water. These steps significantly impact simulation stability, computational cost, and the accuracy of subsequent analyses. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and quantitative guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to correctly implement these crucial procedures within the GROMACS framework.

Theoretical Background

The Role of Periodic Boundary Conditions

Molecular dynamics simulations employ periodic boundary conditions (PBC) to avoid edge effects and simulate a more natural, infinite environment [28]. Under PBC, the simulation box is replicated infinitely in all directions. When a particle exits the central box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters through the opposite face [28]. This approach ensures that the number of particles remains constant and eliminates vacuum interfaces that would otherwise create unnatural forces.

The simulation box shape and dimensions must be carefully selected to balance computational efficiency with biological relevance. For globular proteins, the box should provide sufficient solvent padding around the solute to prevent artificial interactions between periodic images. For membrane proteins or elongated structures, box dimensions must accommodate the specific architecture while minimizing unnecessary solvent that increases computational burden.

Solvation Principles and Solvent Models

Solvation involves immersing the solute molecule in solvent particles to create a biologically relevant environment. The gmx solvate tool in GROMACS performs this operation by filling the simulation box with solvent molecules, typically water, while removing any that clash with the solute atoms [29]. The program identifies clashes by comparing interatomic distances against a database of van der Waals radii (vdwradii.dat), which are scaled by a factor (default: 0.57) to achieve proper density [29].

GROMACS supports various 3-site water models, with Simple Point Charge (SPC) water as the default [29]. The program uses coordinates from $GMXLIB/spc216.gro, which can also serve as a starting point for other 3-site water models after brief equilibration [29]. The solvation process can also incorporate ions to neutralize system charge or achieve specific physiological concentrations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Components for Simulation Box Setup and Solvation

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS Suite | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Provides all necessary tools (gmx solvate, gmx editconf) for system preparation [29] |

| Solvent Coordinate File | Pre-equilibrated solvent system (e.g., spc216.gro) |

Supplies pre-configured solvent molecules for solvation [29] |

| Force Field | Parameter set defining molecular interactions (e.g., OPLS/AA) | Determines van der Waals radii, atomic charges, and bonding parameters [2] |

| vdwradii.dat | Database of van der Waals radii | Contains atomic radii used for clash detection during solvation [29] |

| Topology File | Molecular structure definition (.top) | Defines molecular composition and connectivity; updated with solvent molecule count [29] |

Quantitative Parameters for System Setup

Table 2: Critical Parameters for gmx solvate Command

| Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Range | Description | Impact on Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -scale | 0.57 | 0.5-0.6 | Scale factor for van der Waals radii from vdwradii.dat [29] | Lower values increase solvent density; 0.57 yields ~1000 g/L for proteins in water [29] |

| -radius | 0.105 [nm] | 0.1-0.15 [nm] | Default van der Waals distance for atoms not in database [29] | Affects solvent placement and system density |

| -shell | 0 [nm] | 0.8-1.5 [nm] | Thickness of water layer around solute [29] | Thicker layers reduce periodicity artifacts but increase system size |

| -maxsol | 0 (unlimited) | ≥0 | Maximum number of solvent molecules to add [29] | Non-zero values create voids; generally avoid for complete solvation |

| -box | (0 0 0) | Variable | Box size vector in nm [29] | Determines system volume; set explicitly or from solute coordinate file |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for System Preparation

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for preparing a solvated system in GROMACS, beginning with a solute structure and progressing through topology generation, boxing, solvation, and equilibration.

Protocol 1: Defining the Simulation Box

Objective: Create an appropriately sized and shaped simulation box around a solute molecule.

Materials:

- Input structure file (GRO format) from

gmx pdb2gmxor similar - GROMACS installation with

gmx editconftool

Method:

- Center the solute: Use

gmx editconfto center the molecule in the box: The-cflag centers the structure in the box [29].

Define box dimensions and type: Select an appropriate box type and size:

- Box type (

-bt): Common choices include:cubic: Simple cubic box (default)dodecahedron: Rhombic dodecahedron (most efficient for globular proteins) [2]octahedron: Truncated octahedron

- Distance (

-d): Set the minimum distance (nm) between the solute and box edge [2]. For most proteins, 1.0-1.5 nm is sufficient.

- Box type (

Alternative explicit box dimensions: For specific dimension requirements:

This creates a rectangular box of specified dimensions (x, y, z in nm).

Troubleshooting:

- For elongated molecules, use rectangular boxes with custom dimensions

- For membrane simulations, ensure box dimensions match lipid bilayer dimensions

- Verify box size using

gmx checkor visualization tools

Protocol 2: System Solvation

Objective: Fill the simulation box with solvent molecules while removing clashes with solute atoms.

Materials:

- Boxed solute structure (GRO format)

- Topology file (TOP format)

- Solvent coordinate file (default:

spc216.gro)

Method:

- Basic solvation command:

-cp: Input solute coordinate file-cs: Input solvent coordinate file (uses SPC water by default) [29]-p: Topology file (will be updated with solvent molecule count)-o: Output solvated coordinate file

Advanced solvation with hydration shell:

The

-shellparameter adds a water layer of specified thickness (nm) around the solute, which is particularly useful for spherical systems [29].Custom van der Waals parameters:

Validation:

- Check the solvation log file for the number of solvent molecules added

- Verify the topology file has been updated with the correct solvent count

- Visually inspect the solvated system using molecular visualization software

- Run a brief energy minimization to resolve any remaining steric clashes

Protocol 3: Aqueous Solvation with Ion Addition

Objective: Solvate the system and add ions to neutralize charge and achieve physiological concentration.

Materials:

- Solvated system (GRO and TOP files)

- Ion topology parameters (included in force field)

- GROMACS

gmx geniontool

Method:

- Prepare input for ion addition:

- Replace solvent molecules with ions:

-pname/-nname: Specify positive and negative ion names (force field dependent)-neutral: Add ions to neutralize system charge [2]-conc: Add additional ions to achieve specific molar concentration (e.g., 0.15 M for physiological saline)

Considerations:

- For systems with net charge, additional counterions will be added automatically during neutralization

- Select ion names compatible with your chosen force field (e.g., NA+/CL- for OPLS/AA)

- The program will prompt for a group to replace with ions; typically select "SOL"

Applications in Drug Development

Proper solvation protocols are particularly crucial in pharmaceutical applications where accurate representation of molecular interactions directly impacts predictive capabilities. In drug delivery research, MD simulations help optimize carrier systems like functionalized carbon nanotubes, chitosan-based nanoparticles, and human serum albumin (HSA) by providing atomic-level insights into drug encapsulation, stability, and release processes [30]. Accurate solvation ensures reliable prediction of solubility, permeation, and binding affinities for anticancer drugs including Doxorubicin (DOX), Gemcitabine (GEM), and Paclitaxel (PTX) [30].

For drug binding studies, sufficient solvent padding (typically ≥1.0 nm) prevents artificial interactions between periodic images of the protein-ligand complex. The choice of water model (SPC, SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P) should align with the selected force field to maintain consistency with parameterization assumptions. These considerations significantly impact the accuracy of binding free energy calculations and residence time predictions used in rational drug design.

A Step-by-Step GROMACS Simulation Workflow: From Energy Minimization to Production

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the topology defines the system's physical structure and potential energy surface. It comprehensively describes the molecules within the system, including their atomic composition, chemical connectivity, and the force field parameters governing their interactions. This document provides a detailed protocol for constructing molecular topologies and defining force field parameters within the GROMACS MD package, forming a critical step in accurate simulation setup.

Force Field Selection

The force field provides the mathematical functions and parameters used to calculate the potential energy of the system. GROMACS includes numerous pre-parameterized force fields, each with specific strengths and intended applications [31].

Table 1: Standard Force Fields Distributed with GROMACS [31]

| Force Field Family | Specific Versions | Typical Application Domain |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | AMBER03, AMBER94, AMBER96, AMBER99, AMBER99SB, AMBER99SB-ILDN | Proteins, nucleic acids, general biomolecules |

| CHARMM | CHARMM27 | All-atom simulations, proteins, lipids, nucleic acids (includes CMAP for proteins) |

| GROMOS | 43a1, 43a2, 45a3, 53a5, 53a6, 54a7 | United-atom simulations, lipids, biomolecular condensed phases |

| OPLS | OPLS-AA/L | All-atom simulations, liquid systems, proteins |

Selecting an appropriate force field is a foundational decision. The choice should be guided by the system's composition (e.g., protein, DNA, membrane) and the properties of interest, ensuring compatibility with the chosen water model [32]. Researchers are encouraged to consult the literature for force fields validated for their specific type of molecule or phenomenon.

Topology Construction Workflow

The process of building a system topology involves translating a molecular structure from coordinates into a GROMACS-readable description of molecules and their interactions. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this process.

Generating Topologies for Standard Molecules

For standard biomolecules like proteins and nucleic acids, the pdb2gmx tool automates topology generation.

- Preprocess Input Structure: Clean your initial PDB file by removing crystallographic waters, ions, or other non-essential molecules. For example, to remove waters, use:

- Execute

pdb2gmx: During execution, the program will interactively prompt you to select a force field and a water model from the available options [24]. This ensures self-consistent parameter sets. - Analyze Outputs:

pdb2gmxgenerates three key files:topol.top: The main topology file containing molecule definitions and force field inclusions.processed.gro: The processed coordinates in GROMACS format.posre.itp: A file containing position restraints for the heavy atoms, which can be used during equilibration.

Handling Non-Standard Molecules and Ligands

Molecules not defined in the force field's residue database (e.g., drugs, cofactors, novel linkers) require manual parametrization. The general principle is to use small model compounds and piece the larger topology together, rather than parametrizing a huge molecule in one step [33].

- Obtain Initial Structure: Acquire or draw the 3D structure of your ligand (e.g., in MOL2 format).

- Generate Parameters: Use specialized external tools such as:

- CGenFF: For the CHARMM force field family.

- ACPYPE (AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE) or antechamber: For the AMBER force field family.

- Automated Topology Builder (ATB): For the GROMOS force field family.

- Incorporate Parameters: Manually integrate the generated parameters into your system topology. This typically involves:

- Adding new

[ atomtypes ]if needed. - Including a new

.itpfile for the ligand molecule. - Adding the ligand to the

[ molecules ]directive in the main.topfile.

- Adding new

Topology File Structure and Parameter Definition

The GROMACS topology file is highly structured. Understanding its components is essential for verification and modification.

Anatomy of a Topology File

A typical .top file, as generated by pdb2gmx, contains the following sections [34] [24]:

#include "forcefield.itp": This statement imports all the core parameters for the chosen force field [31].[ moleculetype ]: Defines a molecule and the number of bonds (nrexcl) for non-bonded neighbor exclusion.[ atoms ]: Lists every atom in the molecule, specifying its type, residue, charge, and mass.[ bonds ],[ angles ],[ dihedrals ]: Define the covalent connectivity and associated parameters.[ system ]and[ molecules ]: Declare the name of the entire system and list the constituent molecules and their counts.

Modifying and Adding Parameters

Force field parameters are not static; they can be modified or extended to improve accuracy or cover new chemical species.

Changing Existing Bonded Parameters: To alter parameters for specific interactions, add the new parameter definition after the force field inclusion in the topology. GROMACS uses the last definition it encounters [31].

Adding New Atom Types: New atom types can be defined in an extra

[ atomtypes ]section following the force field inclusion. After defining the type, additional[ nonbond_params ]can be specified [31].Defining Non-Bonded Interactions: The interpretation of the

VandWparameters in[ atomtypes ]and[ nonbond_params ]depends on the combination rule defined in the[ defaults ]section [35]. For combination rule 1,Vis C6 andWis C12, whereas for rules 2 and 3,Vis σ andWis ε.

Table 2: Key File Types in Force Field Directories [31] [35]

| Filename | Purpose and Content |

|---|---|

forcefield.itp |

Main file; includes other files and sets default non-bonded rules. |

ffnonbonded.itp |

Contains [ atomtypes ] and [ nonbond_params ] for van der Waals interactions. |

ffbonded.itp |

Contains [ bondtypes ], [ angletypes ], [ dihedraltypes ], etc. |

.rtp (Residue Topology) |

Contains standardized building blocks (residues) used by pdb2gmx. |

.atp |

Atom type database containing masses. |

.hdb |

Hydrogen database for adding hydrogens during pdb2gmx execution. |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Topology Construction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

gmx pdb2gmx |

GROMACS Module | Generates topologies and processed coordinates for standard proteins/nucleic acids from PDB files [24]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Server | Prepares complex simulation systems, including membranes and solutions, with CHARMM/AMBER force fields [32]. |

| Automated Topology Builder (ATB) | Web Server | Provides and validates molecular topologies for the GROMOS force field family [32]. |

| ACPYPE | Software Tool | Converts AMBER force field parameters (from antechamber) into GROMACS-compatible .itp files [32]. |

| CGenFF | Web Server/Software | Generates parameters for drug-like molecules within the CHARMM force field ecosystem [36]. |

vdwradii.dat |

Database File | Contains van der Waals radii for atom types; used by solvate and other tools. Can be customized by user [32]. |

A correctly constructed topology is the bedrock of a meaningful and stable MD simulation. This protocol has outlined the critical steps: from selecting a validated force field, to generating topologies for standard and non-standard molecules, and finally to understanding the topology file structure for manual verification and modification. Meticulous attention at this preparatory stage prevents common simulation failures and ensures the physical realism of the computed trajectories, thereby laying the groundwork for robust scientific conclusions.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the initial configuration of a system, often derived from experimental structures, may contain steric clashes or inappropriate geometry due to discrete atom placement, preceding mutations, or other manipulations [37]. These structural imperfections result in excessively high potential energy, which, if unaddressed, can cause simulation instability and integration failure [38]. Energy minimization (EM) serves as the critical first computational step to relieve these strains by iteratively adjusting atomic coordinates to find a local energy minimum on the potential energy surface [39]. This process removes all kinetic energy, providing a low-energy, stable starting configuration essential for subsequent simulation steps, including equilibration and production MD [38]. Performing EM is a foundational practice within the GROMACS MD workflow, ensuring the system's mechanical stability before introducing thermal motion.

Theoretical Foundation of Energy Minimization

Energy minimization algorithms operate by searching for configurations where the net force on each atom approaches zero. The potential energy ( V ) of a system is a function of the coordinates of all ( N ) atoms, ( \mathbf{r}1, \mathbf{r}2, \ldots, \mathbf{r}N ). The force on each atom ( i ) is the negative gradient of this potential: ( \mathbf{F}i = - \frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}_i} ) [38]. The minimization is considered successful when the maximum absolute value of any force component in the system falls below a user-specified tolerance, ( \epsilon ) [39]. A reasonable value for ( \epsilon ) can be estimated from the root mean square force of a harmonic oscillator at a given temperature. For a weak oscillator at 1 K, this force is approximately 7.7 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹, thus a practical ( \epsilon ) value is typically between 1 and 1000 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹, depending on the desired precision and the system's intended purpose [39].

Table 1: Core Algorithms for Energy Minimization in GROMACS

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent [39] | Moves atoms in the direction of the negative gradient (force). The step size is adjusted heuristically. | Robust, easy to implement, effective for initial steps away from high-energy structures. | Slow convergence near the energy minimum. | Initial relaxation of systems with steric clashes. |

| Conjugate Gradient [39] | Uses a sequence of non-interfering (conjugate) directions for successive steps. | More efficient than Steepest Descent closer to the minimum. | Cannot be used with constraints (e.g., rigid water models). | Minimization prior to normal-mode analysis. |

| L-BFGS [39] | A quasi-Newton method that approximates the inverse Hessian matrix from a history of previous steps. | Fastest convergence for large systems in practice. | Not yet parallelized; requires more memory per step. | General-purpose minimization for large biomolecular systems. |

Practical Implementation in GROMACS

Parameter Selection in the MDP File

The control parameters for energy minimization in GROMACS are defined in the molecular dynamics parameter (mdp) file. The choice of algorithm is specified via the integrator directive [21]. Key parameters common to all minimizers include emtol, the force tolerance for convergence (default: 10.0 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹), and nsteps, the maximum number of steps allowed (default: -1, meaning no limit) [21]. For the Steepest Descent algorithm, the emstep parameter defines the initial maximum displacement (in nm) [39] [21].

Table 2: Key MDP Parameters for Energy Minimization

| Parameter | Value for Steepest Descent | Value for Conjugate Gradient | Value for L-BFGS | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

integrator |

steep |

cg |

l-bfgs |

Selects the minimization algorithm [21]. |

emtol |

10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | Force tolerance for convergence (kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹) [21]. |

nsteps |

-1 | -1 | -1 | Maximum number of minimization steps [21]. |

emstep |

0.01 | N/A | N/A | Initial maximum step size for Steepest Descent (nm) [21]. |

nstcgsteep |

N/A | 1000 | N/A | Frequency of steepest descent steps within CG [21]. |

Executing the Minimization

The minimization run is executed using the mdrun program. The command and associated steps are consistent across different types of simulations.

This will produce output files including em.gro (minimized structure), em.trr (trajectory), em.edr (energy file), and em.log (log file).

Analysis of Results and Convergence Criteria

A successful energy minimization is characterized by convergence, where the potential energy reaches a stable, negative value and the maximum force in the system (Fmax) falls below the specified emtol [37]. For a typical protein in water, the potential energy (Epot) should be negative and on the order of 10⁵–10⁶ kJ/mol, a value that scales with the system size and the number of water molecules [37]. The log file (em.log) reports the Fmax and Epot at each step and upon completion, which must be checked to verify success.

It is possible for the minimization to reach the maximum number of steps (nsteps) with a reasonable Epot but with Fmax still above emtol. This indicates non-convergence and suggests the system may be unstable for subsequent equilibration. In such cases, the minimization should be continued by using the output structure (em.gro) as a new starting point, potentially with an increased nsteps or a adjusted step size [37].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for performing and validating energy minimization, integrating the choice of algorithm and convergence checks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Energy Minimization

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Coordinate File | Defines the initial 3D atomic structure of the system. | GRO file, PDB file [37]. |

| Topology File | Defines the chemical makeup, connectivity, and force field parameters of the molecules in the system. | TOP file [21]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Parameters (MDP) File | A text file specifying all control parameters for the simulation, including the choice of integrator and convergence criteria. | MDP file [21]. |

| Force Field | A set of mathematical functions and parameters defining the potential energy of the system. Examples include CHARMM, AMBER, and GROMOS. | Included in topology and parameter files [38]. |

| GROMACS Executables | The software suite used to preprocess the input (gmx grompp) and run the minimization (gmx mdrun). |

GROMACS installation [13]. |

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the process of equilibration is critical for achieving stable, production-ready systems that accurately represent physiological or experimental conditions. Equilibration involves bringing a system to a desired thermodynamic state before data collection begins. This process typically occurs in two sequential phases: first under the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature), followed by the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature). The NVT ensemble, also known as the canonical ensemble, allows the system to thermally relax and stabilize at the target temperature. The subsequent NPT ensemble, or isothermal-isobaric ensemble, allows the system density to adjust while maintaining constant pressure, which most closely resembles experimental conditions [40]. Proper execution of both equilibration phases is essential for preventing non-physical behavior, corrupted trajectories, or complete simulation failure [41].

Theoretical Foundation of Ensemble Equilibration

The NVT (Canonical) Ensemble

The NVT ensemble maintains a constant number of particles (N), fixed volume (V), and constant temperature (T). During NVT equilibration, the system's temperature is stabilized through the application of thermostats that modulate atomic velocities. The temperature in MD simulations is computed from the total kinetic energy of the system using the equipartition theorem [42]. The role of a thermostat is not to maintain a perfectly constant temperature at every timestep, but rather to ensure the system achieves the correct average temperature with appropriate fluctuations around this average [42]. For a protein simulation in aqueous solution, typical NVT equilibration periods range from 50-100 picoseconds, though larger or more complex systems may require longer timescales [43] [41].

The NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) Ensemble

The NPT ensemble maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T). This phase typically follows NVT equilibration and allows the system density to stabilize. Pressure in MD is calculated from both the kinetic energy and the virial contribution [42]. Similar to temperature, pressure exhibits significant fluctuations in MD simulations, and instantaneous pressure values are essentially meaningless. The pressure coupling algorithm (barostat) ensures the system maintains the correct average pressure over time [40]. This phase generally requires longer simulation time than NVT equilibration because pressure relaxation occurs more slowly than temperature stabilization [40].

Essential Parameters for Equilibration Protocols

Integration and Control Parameters

Table 1: Key Molecular Dynamics Parameters for System Equilibration

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | NVT Value/Range | NPT Value/Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | integrator |

md (leap-frog) |

md (leap-frog) |

Algorithm for integrating equations of motion |

| Time Parameters | dt |

0.001-0.002 ps | 0.001-0.002 ps | Integration time step |

nsteps |

50,000-100,000 | 250,000-500,000 | Number of integration steps | |

| Temperature Coupling | tcoupl |

V-rescale | V-rescale | Thermostat algorithm |

tau-t |

0.5-1.0 ps | 0.5-1.0 ps | Thermostat time constant | |

ref-t |

300 K (or target) | 300 K (or target) | Reference temperature | |

tc-grps |

Protein Non-Protein | Protein Non-Protein | Groups for temperature coupling | |

| Pressure Coupling | pcoupl |

No | C-rescale | Barostat algorithm |

tau-p |

- | 1.0-2.0 ps | Barostat time constant | |

ref-p |

- | 1.0 bar | Reference pressure | |

compressibility |

- | 4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ | System compressibility | |

| Constraint Algorithm | constraints |

h-bonds | h-bonds | Bond constraint algorithm |

| Continuation | continuation |

No | Yes | Continue from previous simulation |

| Velocity Handling | gen_vel |

Yes | No | Generate initial velocities |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GROMACS Equilibration

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Choices | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Defines potential energy functions and parameters | GROMOS-96, OPLS-AA/L, CHARMM36, AMBER [44] [16] | Select based on system composition; GROMOS-96 for united-atom, OPLS-AA/L for all-atom simulations |

| Water Models | Solvation environment | SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P | TIP3P common for biomolecular systems; affects density (expected ~986 kg/m³ for pure TIP3P water) [40] |

| Thermostats | Temperature control | V-rescale, Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen | V-rescale recommended for correct fluctuations; avoid Berendsen for production runs [42] |

| Barostats | Pressure control | C-rescale, Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen | C-rescale provides correct ensemble; Berendsen for initial equilibration only |

| Ion Parameters | System neutralization and physiological concentration | Na⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺, Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺ | Include appropriate ions for biological systems; affects electrostatic interactions |

| Position Restraints | Maintain protein structure during initial equilibration | posre.itp |

Applied to protein heavy atoms; force constants typically 1000 kJ/mol/nm² |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

NVT Equilibration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for NVT equilibration:

Step 1: Input Preparation

Begin with a properly energy-minimized system. The input structure is typically provided as a GRO file from the previous minimization step. Use the GROMACS grompp module to preprocess the simulation data:

The -r flag provides reference coordinates for position restraints, which are typically applied to protein heavy atoms during initial equilibration to maintain structural integrity while allowing solvent relaxation [43].

Step 2: Parameter Configuration Configure the NVT parameters in the molecular dynamics parameter (mdp) file. Key settings include: