Beyond Guesswork: A Systematic Framework for Molecular Dynamics Equilibration in Biomedical Research

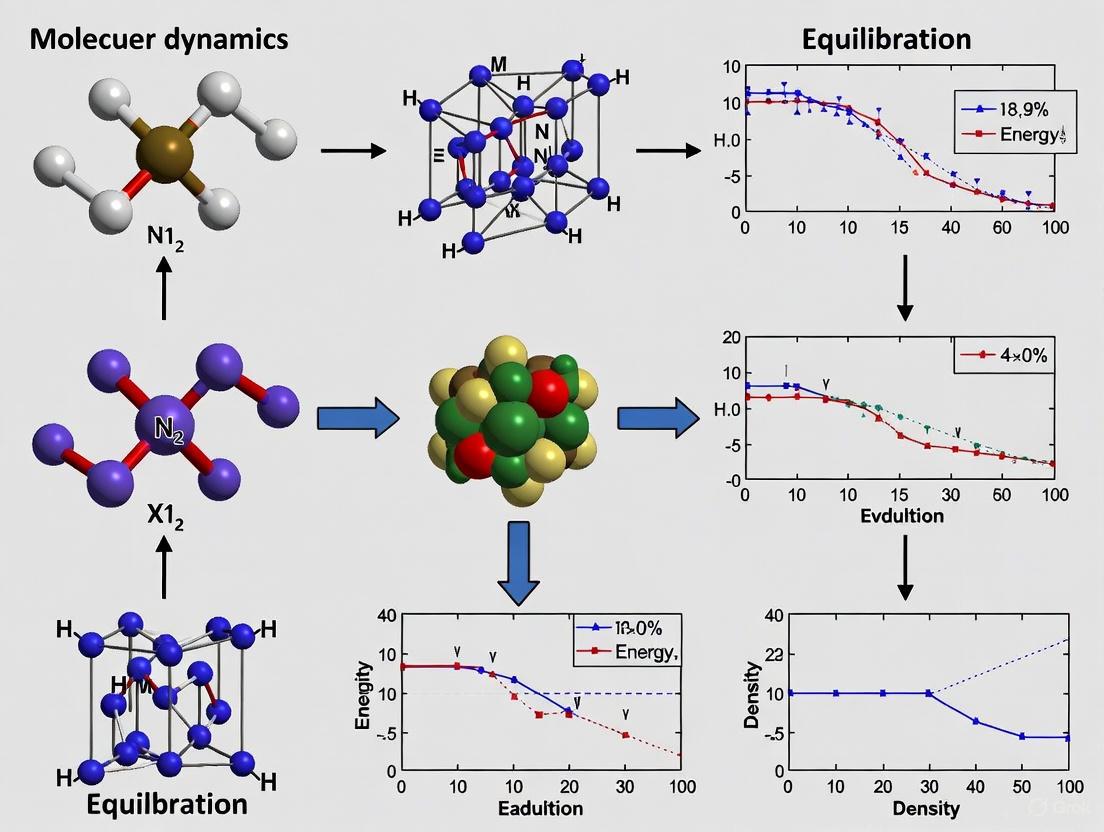

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the molecular dynamics (MD) equilibration process, a critical yet often heuristic step for obtaining physically meaningful simulation results.

Beyond Guesswork: A Systematic Framework for Molecular Dynamics Equilibration in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the molecular dynamics (MD) equilibration process, a critical yet often heuristic step for obtaining physically meaningful simulation results. We demystify equilibration by presenting a systematic framework that moves from foundational concepts to advanced optimization techniques. Covering position initialization, thermostating protocols, and uncertainty quantification, this guide addresses the core challenges researchers face in achieving thermodynamic equilibrium. It further explores modern validation methods, including machine learning and deep learning approaches, to determine equilibration adequacy. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource aims to transform equilibration from an arbitrary preparatory step into a rigorous, quantifiable procedure, thereby enhancing the reliability of MD simulations in predicting drug solubility, protein-ligand interactions, and other vital biomedical properties.

Why Equilibration Matters: The Bedrock of Reliable MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations constitute an important tool for investigating classical and quantum many-body systems across physics, chemistry, materials science, and biology [1]. Obtaining physically meaningful results from these simulations requires a crucial preliminary stage known as equilibration—a period during which the system evolves from its initial configuration to a stable, thermodynamically consistent state before data collection commences [1]. This step is essential to ensure that subsequent production runs yield results that are neither biased by the initial configuration nor deviate from the target thermodynamic state [1].

The efficiency and success of the equilibration phase are largely determined by two key factors: the initial configuration of the system in phase space and the thermostating protocols applied to drive the system toward the desired state [1]. Traditionally, equilibration parameters have been selected through largely heuristic processes, relying on researcher experience, trial and error, or expert consultation [1]. This lack of systematic methodology introduces potential inconsistencies across studies and raises questions about the reliability of subsequent production runs [1]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and implementing effective equilibration procedures based on current research and systematic evaluations.

The Critical Role of Initial Conditions

Generating a set of initial positions consistent with the specified thermodynamic state presents a significantly greater challenge than initializing velocities, which can be readily sampled from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [1]. Poor initial spatial configurations can result in characteristic temperature changes, extended equilibration times, or persistent biases in production runs [1].

Position Initialization Methods

A comprehensive evaluation of seven position initialization algorithms reveals significant differences in their performance and suitability for different coupling regimes [1]. The table below summarizes these methods and their characteristics:

Table 1: Position Initialization Methods for MD Simulations

| Method | Description | Computational Scaling | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Random (Uni) | Samples each coordinate uniformly from available position space | O(N) | Low coupling strengths; simple and fast for preliminary studies |

| Uniform Random with Rejection (Uni Rej) | Adds rejection radius to prevent particle clumping; resamples if particles too close | O(N) but with higher constant factor | Systems where particle overlap is a concern; moderate coupling strengths |

| Halton Sequence | Low-discrepancy quasi-random sequence generator | O(N) | Systems requiring even spatial distribution without clumping |

| Sobol Sequence | Low-discrepancy quasi-random sequence generator | O(N) | Similar to Halton but with different mathematical properties |

| Monte Carlo Pair Distribution (MCPDF) | Mesh-based Monte Carlo matching input pair distribution function | Computationally intensive | High-precision studies where target distribution is known |

| BCC Lattice (BCC Uni) | Body-centered cubic lattice initialization | O(N) | High coupling strengths; crystalline systems |

| BCC Beta Perturbed | BCC lattice with physical perturbations using compact beta function | O(N) | High coupling strengths needing slight disorder |

The selection of an appropriate initialization method depends significantly on the coupling strength of the system being simulated. Research demonstrates that while initialization method selection is relatively inconsequential at low coupling strengths, physics-informed methods (such as lattice-based approaches) demonstrate superior performance at high coupling strengths, substantially reducing equilibration time [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Initialization Impact

The mathematical foundation for understanding clumping behavior in random initialization methods reveals why method selection matters, particularly for large systems. For uniform random placement, the probability that any two particles fall within a critical distance (a) of each other is approximately:

[ P(d \leq a) \approx \frac{4\pi a^3}{3L^3} ]

where (L) is the simulation box side length [1]. The expected number of close pairs scales quadratically with particle number (N):

[ E[\text{close pairs}] \approx \frac{2\pi a^3 N(N-1)}{3L^3} ]

This quadratic scaling means that as system size increases, particle clumping becomes virtually inevitable with pure random placement, leading to large repulsive forces and substantial energy injection that subsequently requires long thermalization times [1]. The critical distance (ac) at which we expect to find the first close pair scales as (ac \propto N^{-2/3}), meaning for large (N), particles will be found at increasingly small separations [1].

Thermostating Protocols and Uncertainty Quantification

Once initial positions are established, the system must be driven to the target thermodynamic state through the application of thermostats. A systematic comparison of thermostating protocols reveals several critical factors affecting equilibration efficiency.

Thermostat Comparison and Duty Cycles

Table 2: Thermostating Protocols and Their Performance Characteristics

| Thermostating Parameter | Options | Performance Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostat Algorithm | Berendsen vs. Langevin | Weaker thermostat coupling generally requires fewer equilibration cycles | Select based on system properties and desired coupling strength |

| Duty Cycle Sequence | OFF-ON vs. ON-OFF | OFF-ON sequences outperform ON-OFF approaches for most initialization methods | Implement OFF-ON cycling for more efficient equilibration |

| Coupling Strength | Strong vs. Weak coupling | Weaker coupling generally requires fewer equilibration cycles | Use weaker coupling when system stability permits |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Temperature forecasting | Enables determination of equilibration adequacy based on uncertainty tolerances | Implement UQ framework for objective termination criteria |

Research establishes direct relationships between temperature stability and uncertainties in transport properties such as diffusion coefficient and viscosity [1]. By implementing temperature forecasting as a quantitative metric for system thermalization, users can determine equilibration adequacy based on specified uncertainty tolerances in desired output properties [1]. This transforms equilibration from a heuristic process to a rigorously quantifiable procedure with clear termination criteria [1].

Statistical Framework for Equilibration Assessment

The reproducibility challenges in MD simulations necessitate a statistical approach to equilibration assessment. As noted in studies of calmodulin equilibrium dynamics, when repeated from slightly different but equally plausible initial conditions, MD simulations predict different values for the same dynamic property of interest [2]. This occurs because MD simulations fall short of properly sampling a protein's conformational space, an effect known as the "sampling problem" [2].

A statistical approach involves preparing multiple independent MD simulations from different but equally plausible initial conditions [2]. For example, in one study, 35 independent MD simulations of calmodulin equilibrium dynamics were prepared (20 simulations of the wild-type protein and 15 simulations of a mutant) [2]. This enabled quantitative comparisons at the desired error level using statistical tests, revealing effects that were not observed in studies relying on single MD runs [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Systematic Equilibration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for systematic MD equilibration, incorporating uncertainty quantification and multiple initialization strategies:

Systematic MD Equilibration Workflow

Microfield Distribution Analysis

Microfield distribution analysis provides diagnostic insights into thermal behaviors during equilibration [1]. This methodology implements temperature forecasting as a quantitative metric for system thermalization, enabling users to determine equilibration adequacy based on specified uncertainty tolerances in desired output properties [1]. The relationship between initialization methods and their performance across different coupling regimes can be visualized as follows:

Initialization Method Selection Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Equilibration

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| drMD | Automated pipeline for running MD simulations using OpenMM | User-friendly automation reducing barrier to entry for non-experts [3] |

| StreaMD | Python-based toolkit for high-throughput MD simulations | Automation of preparation, execution, and analysis phases across distributed systems [4] |

| Distributional Graphormer (DiG) | Deep learning framework for predicting equilibrium distributions | Efficient generation of diverse conformations and estimation of state densities [5] |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Machine learning models with physics-informed loss functions | Accelerating charge estimation and enforcing physical constraints [6] |

| Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) | Descriptors for characterizing local atomic environments | Featurization of atomic environments for machine learning applications [6] |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks | Deep learning models for time-series forecasting | Transient predictions of partial charges in reactive MD simulations [6] |

| Berendsen Thermostat | Algorithm for temperature control | Weak coupling approach for efficient equilibration [1] |

| Langevin Thermostat | Stochastic dynamics for temperature control | Alternative thermostat algorithm with different coupling characteristics [1] |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Deep Learning Approaches to Equilibrium Distributions

Recent advances in deep learning have introduced new approaches for predicting equilibrium distributions of molecular systems. The Distributional Graphormer (DiG) framework uses deep neural networks to transform a simple distribution toward the equilibrium distribution, conditioned on a descriptor of a molecular system such as a chemical graph or protein sequence [5]. This framework enables efficient generation of diverse conformations and provides estimations of state densities, orders of magnitude faster than conventional methods [5].

For data-scarce scenarios, physics-informed diffusion pre-training (PIDP) methods can train deep learning models with energy functions (such as force fields) of the systems [5]. This approach demonstrates that deep learning can advance molecular studies from predicting single structures toward predicting structure distributions, potentially revolutionizing the computation of thermodynamic properties [5].

Statistical Validation and Reproducibility

A critical aspect of equilibration validation involves statistical testing of simulation results. For example, in studies of protein radius of gyration, the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality can be applied to assess whether data originated from a normal parent distribution [2]. Following this, F-tests for equality of variances and two-sample t-tests can provide evidence regarding whether different simulation conditions (e.g., wild-type vs. mutant) produce statistically distinguishable results [2].

This statistical framework addresses the fundamental question of reproducibility in MD simulations: "How do we know that some property observed in an MD simulation, which may lend itself to some important biological or physical interpretation, is not merely an 'accident' of the particular simulation?" [2]. By applying statistical tests at the desired error level, researchers can make quantitative comparisons between simulations and with experimental data [2].

Equilibration represents a critical phase in molecular dynamics simulations, transforming systems from arbitrary initial conditions to thermodynamically consistent states suitable for production runs. Through systematic evaluation of position initialization methods and thermostating protocols, researchers can significantly reduce equilibration times and improve simulation reliability. The integration of uncertainty quantification frameworks provides objective criteria for determining equilibration adequacy, moving beyond traditional heuristic approaches.

As MD simulations continue to evolve, incorporating advanced statistical validation, deep learning approaches, and high-throughput automation tools, the process of equilibration becomes increasingly rigorous and quantifiable. By adopting the methodologies and best practices outlined in this technical guide, researchers can ensure their simulations yield physically meaningful results that faithfully represent the thermodynamic states of interest.

{# The Critical Consequences of Inadequate Equilibration on Simulation Outcomes #}

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool in computational molecular biology and structure-based drug design, capable of complementing experimental techniques by providing atomic-level insight into biomolecular function. However, the foundational assumption underlying most MD studies—that the simulated system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium—is often overlooked. Inadequate equilibration can invalidate simulation results, leading to erroneous conclusions about molecular mechanisms, drug-target interactions, and protein folding. This technical guide examines the critical consequences of insufficient equilibration through detailed analysis of convergence metrics, presents validated protocols for equilibrium assessment, and provides practical solutions for researchers seeking to ensure the reliability of their simulation outcomes, particularly in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications.

In molecular dynamics simulations, the equilibration process represents the critical transitional phase where a system evolves from its initial, often non-physical, configuration toward a state of thermodynamic equilibrium that properly represents the Boltzmann-distributed ensemble of states at a given temperature [7]. The starting point for most biomolecular simulations is an experimentally determined structure from the Protein Data Bank, which is obtained under non-equilibrium conditions (e.g., crystal packing forces in X-ray crystallography) [7]. Consequently, the simulated system must be allowed to relax and explore its conformational space before production simulations can be considered representative of true thermodynamic behavior.

The fundamental challenge lies in determining when true equilibrium has been reached. As noted in Communications Chemistry, "This is a question that, in our opinion, is being surprisingly ignored by the community, but needs to be thoroughly addressed since, if Hu et al.'s conclusions are generally true, then a majority of currently published MD studies would be rendered mostly meaningless" [7]. This guide addresses this critical methodological gap by providing frameworks for identifying inadequate equilibration and protocols for achieving sufficient sampling.

Defining and Diagnosing Equilibration Problems

Theoretical Framework for Molecular Equilibrium

From a statistical mechanics perspective, equilibrium is defined by the Boltzmann distribution, where the probability of finding the system in a configuration x is proportional to exp[–U(x)/kBT], with U(x) representing the potential energy function, kB Boltzmann's constant, and T the absolute temperature [8]. In practical MD terms, a system can be considered equilibrated when measured properties fluctuate around stable average values with the correct relative probabilities across all significantly populated regions of configuration space [7] [8].

A crucial distinction exists between partial equilibrium, where some properties have converged but others have not, and full equilibrium, where all properties of interest have reached their converged values [7]. This distinction is biologically significant because properties with high biological interest often depend predominantly on high-probability regions of conformational space and may converge more rapidly than transition rates between low-probability conformations [7].

Quantitative Diagnostics for Equilibration Assessment

Robust assessment of equilibration requires monitoring multiple metrics throughout the simulation trajectory. The table below summarizes key properties to monitor and their interpretation:

Table 1: Key Properties for Monitoring Equilibration in MD Simulations

| Property Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation of Convergence | Typical Timescales for Convergence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energetic Properties | Potential energy, Total energy | Stable fluctuations around a constant mean value [7] | Fast (nanoseconds) for local adjustments; slow for global reorganization |

| Structural Properties | Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of backbone atoms [9] | Plateau indicating stable structural ensemble [7] | Varies by system size and flexibility (nanoseconds to microseconds) |

| Dynamic Properties | Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of Cα atoms [9] | Stable residue-specific fluctuation patterns | Longer than RMSD, requires sufficient sampling of sidechain motions |

| System Properties | Radius of gyration (Rg) [9] | Stable compactness indicating proper folding | Critical for assessing global fold stability |

| Advanced Metrics | Autocorrelation functions (ACF) of key properties [7] | Decay to zero indicating sufficient sampling | Can reveal slow processes not apparent in simple averages |

The working definition of equilibrium for practical MD applications can be stated as: "Given a system's trajectory, with total time-length T, and a property Ai extracted from it, and calling 〈Aii calculated between times 0 and t, we will consider that property 'equilibrated' if the fluctuations of the function 〈Aiic, such that 0 < tc < T" [7].

Case Study: The Dialanine Paradox

Even simple systems can demonstrate unexpected equilibration challenges. Studies of dialanine, a 22-atom model system, have revealed unconverged properties in what researchers initially assumed would be a straightforward case for rapid equilibration [7]. If equilibrium is not reached even in this minimal system within conventional simulation timescales, the implications for larger, more complex proteins are profound, suggesting that many current MD studies may be operating with inadequate sampling [7].

Consequences of Inadequate Equilibration

Scientific Implications

The ramifications of insufficient equilibration extend across multiple domains of molecular simulation research:

Mischaracterization of Protein Dynamics: Inadequate sampling can lead to incomplete or incorrect identification of functional states and transition pathways, particularly for allosteric proteins and molecular machines [10].

Erroneous Free Energy Calculations: Free energy and entropy calculations explicitly depend on the partition function, which requires contributions from all conformational regions, including low-probability states [7]. Inadequate sampling of these regions systematically biases results.

Unreliable Drug Design Data: Structure-based drug discovery depends on accurate characterization of binding sites and protein flexibility. Non-equilibrium simulations may stabilize artifactual conformations that mislead drug design efforts [10].

Invalid Biological Mechanisms: When simulations are used to interpret experimental results and propose functional mechanisms, insufficient equilibration can lead to incorrect mechanistic conclusions that misdirect subsequent experimental work [10].

Quantifying the Sampling Deficit

The fundamental challenge in biomolecular simulation is the mismatch between biologically relevant timescales and computationally accessible ones. As noted in annual reviews of biophysics, "modern MD studies still appear to fall significantly short of what is needed for statistically valid equilibrium simulation" [8]. Roughly speaking, a simulation should run at least 10 times longer than the slowest important timescale in a system, yet many biomolecular processes occur on timescales exceeding 1 ms, well beyond routine simulation capabilities [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Simulation Capabilities versus Biological Timescales

| Process Category | Typical Biological Timescales | Routine MD Simulation Capabilities | State-of-the-Art MD Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sidechain Rotations | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Fully accessible | Fully accessible |

| Loop Motions | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Marginally accessible | Accessible with specialized hardware |

| Domain Movements | Microseconds to milliseconds | Largely inaccessible | Marginally accessible |

| Protein Folding | Microseconds to seconds | Inaccessible | Accessible only for small proteins |

| Rare Binding Events | Microseconds to hours | Inaccessible | Accessible with enhanced sampling |

Methodological Framework for Robust Equilibration

Experimental Protocols for Equilibration Assessment

Based on recent studies, the following protocols provide comprehensive assessment of equilibration status:

Protocol 1: Multi-Timescale Analysis of Properties

- Simulate the system for the maximum feasible duration [7]

- Calculate running averages of key properties (RMSD, Rg, potential energy) at multiple time origins [7]

- Identify the point at which these running averages plateau and fluctuate around a stable value

- Continue simulation for at least twice the identified equilibration time before beginning production simulation

Protocol 2: Advanced Sampling Validation

- Perform multiple independent simulations from different initial conditions [8]

- Monitor convergence of probability distributions of key geometric parameters (e.g., dihedral angles, distances)

- Apply statistical tests to confirm that distributions from different replicates are indistinguishable

- Use the replica exchange method to enhance sampling of energetic barriers [8]

Protocol 3: HCVcp Refinement Protocol Based on recent work with hepatitis C virus core protein structure prediction:

- Construct initial models using neural network-based (AlphaFold2, Robetta) or template-based (MOE) approaches [9]

- Perform MD simulations for structural refinement

- Monitor RMSD of backbone atoms, RMSF of Cα atoms, and radius of gyration to track structural convergence [9]

- Continue simulations until all metrics indicate stable structural ensembles

- Validate model quality through ERRAT and phi-psi plot analysis [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Assets

Table 3: Essential Resources for Robust Equilibration Assessment

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Equilibration Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Production MD simulation with optimized force fields [10] |

| Analysis Packages | MDTraj, CPPTRAJ, VMD | Calculation of RMSD, Rg, and other structural metrics [9] |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Replica Exchange MD (REMD), Metadynamics, Accelerated MD | Improved sampling of conformational space [8] |

| Specialized Hardware | GPUs, Specialized MD processors (Anton) | Increased simulation throughput and timescale access [10] [8] |

| Validation Tools | MolProbity, PROCHECK, QMEAN | Structural quality assessment pre- and post-equilibration [9] |

Workflow for Comprehensive Equilibration Assessment

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to equilibration assessment that incorporates multiple validation strategies:

Equilibration Assessment Workflow

Advanced Equilibration Strategies

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

When brute-force MD simulations prove insufficient for achieving equilibrium within practical computational timeframes, enhanced sampling methods become essential:

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD): Simultaneously simulates multiple copies of the system at different temperatures, enabling escape from local energy minima through configuration swapping [8].

Metadynamics: Applies a history-dependent bias potential to encourage exploration of under-sampled regions of conformational space [8].

Accelerated MD: Modifies the potential energy surface to reduce energy barriers between states while preserving the underlying landscape [8].

These methods address the fundamental timescale problem in biomolecular simulation by enhancing conformational sampling without requiring prohibitively long simulation times.

Practical Guidance for Different Biomolecular Systems

Equilibration requirements vary significantly across biomolecular systems:

Small Globular Proteins: May reach partial equilibrium for structural properties within hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds, but rare events (e.g., full unfolding) require much longer sampling [7] [8].

Membrane Proteins: Require careful equilibration of both protein and lipid environment, with particular attention to lipid-protein interactions that evolve over hundreds of nanoseconds [10].

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Present unique challenges as they lack a stable folded state, requiring assessment of convergence in ensemble properties rather than structural metrics [8].

Protein-Ligand Complexes: Require sampling of both protein flexibility and ligand binding modes, with convergence assessment focused on interaction patterns and binding site geometry [10].

The critical consequences of inadequate equilibration represent a fundamental challenge for the molecular simulation community. As MD simulations continue to play an expanding role in structural biology, drug discovery, and biomolecular engineering, rigorous attention to equilibration protocols becomes increasingly essential for generating reliable, reproducible results.

Future advancements will likely come from three complementary directions: continued improvement in force field accuracy, algorithmic innovations in enhanced sampling methods, and hardware developments that extend accessible timescales. Particularly promising are approaches that combine multiple enhanced sampling techniques with machine learning methods to identify optimal reaction coordinates and more efficiently detect convergence [8].

For researchers employing MD simulations, the implementation of robust equilibration assessment protocols—such as those outlined in this guide—represents an immediate opportunity to enhance the reliability and impact of computational studies. By adopting these practices and maintaining a critical perspective on sampling adequacy, the field can advance toward more faithful representations of biomolecular reality, bridging the gap between computational modeling and experimental observation.

The equilibration phase is a critical prerequisite for obtaining physically meaningful results from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in computational chemistry, materials science, and drug development. The efficiency of this phase is predominantly governed by the initial spatial configuration of the system. This whitepaper presents a systematic framework for automating and shortening MD equilibration through improved position initialization methods and uncertainty quantification analysis. We provide a comprehensive evaluation of seven distinct initialization approaches, demonstrating that method selection significantly impacts equilibration efficiency, particularly at high coupling strengths. Our analysis establishes that physics-informed initialization methods coupled with optimized thermostating protocols can substantially reduce computational overhead, transforming equilibration from a heuristic process into a rigorously quantifiable procedure with well-defined termination criteria.

Molecular dynamics simulations constitute an indispensable tool for investigating classical and quantum many-body systems across physics, chemistry, materials science, and biology. Obtaining physically meaningful results requires an equilibration stage during which the system evolves toward a stable, thermodynamically consistent state before production data collection commences. This step is essential to ensure that subsequent results are neither biased by initial configurations nor deviate from the target thermodynamic state [1].

The efficiency of equilibration is predominantly determined by the system's initial configuration in phase space. In classical MD simulations without magnetic fields, the phase space decouples, allowing velocity distribution to be readily sampled from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. However, generating initial positions consistent with specified thermodynamic states presents a significantly greater challenge, necessitating a thermalization phase where the system is driven to the required state typically through thermostats and/or barostats [1].

Despite its fundamental importance, selecting equilibration parameters remains largely heuristic. Researchers often rely on experience, trial and error, or expert consultation to determine appropriate thermostat strengths, equilibration durations, and algorithms. This lack of systematic methodology introduces potential inconsistencies across studies and raises questions about production run reliability [1]. This whitepaper addresses these challenges through a systematic analysis of position initialization methodologies, providing researchers with evidence-based guidelines for optimizing MD equilibration procedures.

Position Initialization Methods

Molecular dynamics simulations initialize with specifications of positions and velocities for all particles. For classical equilibrium simulations without magnetic fields, the phase space decouples, allowing velocities to be sampled randomly from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. This section details seven particle placement algorithms, summarized in Table 1, with the objective of determining optimal choices for specific physical scenarios [1].

Uniform Random (Uni)

The uniform random method represents one of the simplest initialization approaches, sampling each coordinate uniformly from available position space, r ∼ 𝒰(0,Lx)𝒰(0,Ly)𝒰(0,Lz). This method offers straightforward implementation and 𝒪(N) computational scaling. However, it carries a non-zero probability of coincident particle placement that increases with particle count. The probability that any two particles fall within distance a of each other is approximately P(d≤a)≈4πa³/3L³. With N particles creating N(N-1)/2 possible pairs, the expected number of close pairs scales quadratically with N, making clumping virtually inevitable in large systems. These close placements generate substantial repulsive forces, leading to significant energy injection and extended thermalization times [1].

Uniform Random With Rejection (Uni Rej)

This approach modifies uniform random placement by incorporating a rejection radius rrej. If two particles initialize within rrej distance, their positions are resampled until their separation exceeds this threshold. This method directly addresses the clumping problem by enforcing minimum particle separation. The optimal rrej selection should consider both the physical interaction potential and the scaling relationship ac∝N^(-2/3), where a_c represents the critical distance where clumping becomes probable. For large N systems, this rejection method becomes increasingly necessary, though it introduces additional computational overhead during initialization [1].

Quasi-Random Sequence Methods (Halton and Sobol)

Quasi-random sequences provide an alternative to purely stochastic placement by generating low-discrepancy sequences that cover space more uniformly than random samples. The Halton sequence employs coprime bases for different dimensions, while the Sobol sequence uses generating matrices of direction numbers. These methods offer more systematic spatial coverage while maintaining 𝒪(N) computational complexity. They reduce the probability of particle overlap and initial energy spikes compared to uniform random placement, potentially accelerating equilibration convergence [1].

Monte Carlo Pair Distribution (MCPDF)

This mesh-based Monte Carlo method generates initial configurations that match an input pair distribution function. By incorporating structural information from the target state, this physics-informed approach can significantly reduce the configuration space that must be sampled during equilibration. Although computationally more intensive during initialization, the MCPDF method can dramatically decrease equilibration time, particularly for systems with strong coupling where target state correlations are substantial [1].

Lattice-Based Initialization (BCC Uni and BCC Beta)

Lattice methods initialize particles on predefined lattice sites, with body-centered cubic (BCC) arrangements providing high symmetry and packing efficiency. The BCC Uni approach places particles perfectly on lattice sites, while BCC Beta introduces physical perturbations using a compact beta function to displace particles from ideal lattice positions. These methods provide excellent starting points for crystalline or strongly coupled systems but may require longer equilibration for disordered systems or liquids to erase lattice memory [1].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Seven Position Initialization Methods

| Method | Description | Computational Scaling | Optimal Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Random (Uni) | Samples each coordinate uniformly from available space | 𝒪(N) | Low-coupling systems; rapid prototyping | Simple implementation; minimal initialization overhead | High probability of particle clashes; extended equilibration |

| Uniform Random with Rejection (Uni Rej) | Adds minimum distance enforcement via rejection sampling | 𝒪(N) with rejection overhead | General-purpose; moderate coupling strengths | Prevents particle overlaps; more stable initial state | Increased initialization time; rejection sampling challenges |

| Halton Sequence | Low-discrepancy quasi-random sequence with coprime bases | 𝒪(N) | Systems requiring uniform coverage | Superior spatial distribution; reduced clumping | Sequence correlation effects |

| Sobol Sequence | Low-discrepancy quasi-random sequence with generating matrices | 𝒪(N) | High-dimensional systems; uniform sampling | Excellent uniformity properties; deterministic | Complex implementation; dimensional correlation |

| Monte Carlo Pair Distribution (MCPDF) | Mesh-based MC matching target pair distribution function | 𝒪(N) with MC overhead | High-coupling systems; known target structure | Physics-informed; dramatically reduced equilibration | Computationally intensive initialization |

| BCC Lattice (BCC Uni) | Perfect body-centered cubic lattice placement | 𝒪(N) | Crystalline systems; strong coupling | High symmetry; minimal initial energy | Artificial ordering for disordered systems |

| BCC with Perturbations (BCC Beta) | BCC lattice with physical perturbations via beta function | 𝒪(N) | Strongly coupled fluids; glassy systems | Natural disorder introduction; reduced lattice memory | Perturbation amplitude sensitivity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

System Preparation and Equilibration Framework

To evaluate initialization method efficacy, researchers should implement a systematic equilibration protocol beginning with energy minimization to eliminate excessive repulsive forces that could cause numerical instability. Subsequent equilibration should employ thermostating protocols to drive the system toward the target thermodynamic state. Our findings indicate that OFF-ON thermostating sequences (initially without thermostat, then activating it) generally outperform ON-OFF approaches for most initialization methods. Similarly, weaker thermostat coupling typically requires fewer equilibration cycles than strong coupling [1].

The GROMACS MD package, a widely used simulation framework, implements these principles through its comprehensive suite of equilibration tools. The software's default leap-frog algorithm requires initial coordinates at time t = t₀ and velocities at t = t₀ - ½Δt. When velocities are unavailable, the package can generate them from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at specified temperature, subsequently removing center-of-mass motion and scaling velocities to correspond exactly to the target temperature [11].

Equilibration Assessment Metrics

Traditional equilibration monitoring relying solely on density and energy stability may provide insufficient validation of true thermodynamic equilibrium. Research indicates that while energy and density rapidly equilibrate during initial simulation stages, pressure requires considerably longer stabilization. More robust equilibration assessment should incorporate radial distribution function (RDF) convergence, particularly for key interacting components like asphaltene-asphaltene pairs in complex molecular systems [12].

Advanced equilibration frameworks implement temperature forecasting as a quantitative metric for system thermalization, enabling researchers to determine equilibration adequacy based on specified uncertainty tolerances for target output properties. This approach transforms equilibration from an open-ended preparatory step into a quantifiable simulation component with clear success/failure criteria [1].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package with comprehensive equilibration tools [11] |

| Force Fields | GROMOS 54a7 | Parameter sets defining molecular interactions and potential energies [13] |

| System Preparation | Yukawa one-component plasma | Exemplar system for equilibration methodology validation [1] |

| Analysis Framework | Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) | Converts temperature uncertainty into target property uncertainty [1] |

| Thermostat Algorithms | Berendsen, Langevin | Temperature control mechanisms with different coupling characteristics [1] |

| Validation Metrics | Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | Assesses structural convergence and system equilibrium [12] |

| Validation Metrics | Microfield Distribution Analysis | Provides diagnostic insights into thermal behaviors [1] |

Position initialization represents a critical yet frequently overlooked component of molecular dynamics simulations that significantly impacts equilibration efficiency and production run reliability. Our systematic analysis of seven initialization methods demonstrates that selection criteria should be informed by system coupling strength, with method choice being relatively inconsequential at low coupling strengths but critically important for highly coupled systems. Physics-informed initialization approaches, particularly the Monte Carlo pair distribution method and perturbed lattice techniques, demonstrate superior performance for strongly interacting systems by reducing the configuration space that must be sampled during equilibration.

When integrated with appropriate thermostating protocols—notably OFF-ON sequences with weaker coupling strengths—and robust equilibration assessment through uncertainty quantification and radial distribution function convergence monitoring, these initialization strategies can transform MD equilibration from a heuristic process into a rigorously quantifiable procedure. This systematic framework enables researchers to establish clear termination criteria based on specified uncertainty tolerances for target properties, ultimately enhancing computational efficiency and result reliability across drug development, materials science, and biological simulation applications.

Within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the initial assignment of atomic velocities is a critical step that influences the trajectory's path toward thermodynamic equilibrium. This technical guide details the methodology of initializing velocities by sampling from the Maxwell-Boltzmann (MB) distribution, the foundational statistical model for particle speeds in an ideal gas at thermal equilibrium. We frame this specific procedure within the broader, multi-stage context of MD equilibration, a process essential for ensuring simulation stability and the generation of meaningful data for research and drug development. The document provides a thorough theoretical exposition, practical implementation protocols, and robust validation techniques for this core MD task.

In molecular dynamics, the equilibration process prepares a system for the production phase, where data for analysis is collected. A system that is not properly equilibrated may exhibit instability, such as excessively high initial forces leading to a simulation "crash," or may yield non-physical results [14]. A crucial component of this preparation is the initial assignment of velocities to all atoms, which sets the system's initial kinetic energy and temperature.

Sampling atomic velocities from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution provides a physically realistic starting point for a simulation intended to model a system in thermal equilibrium. While this does not instantly place the system in a fully equilibrated state—as the positions and potential energy may still require relaxation—it correctly initializes the kinetic energy distribution corresponding to the desired temperature. This aligns with the goal of the broader equilibration protocol: to gradually relax the system, often by first allowing mobile solvent molecules to adjust around a restrained solute, thereby avoiding catastrophic instabilities [14]. The careful application of the MB distribution is therefore not an isolated operation but a key first step in a coordinated sequence designed to guide the system to a stable and thermodynamically consistent state.

Theoretical Foundation of the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is a probability distribution that describes the speeds of particles in an idealized gas, where particles move freely and interact only through brief, elastic collisions, and the system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium [15]. It was first derived by James Clerk Maxwell in 1860 on heuristic grounds and was later investigated in depth by Ludwig Boltzmann [15].

Mathematical Formulation

For a system containing a large number of identical non-interacting, non-relativistic classical particles in thermodynamic equilibrium, the fraction of particles with a velocity vector within an infinitesimal element (d^3\mathbf{v}) centered on (\mathbf{v}) is given by: [ f(\mathbf{v}) d^3\mathbf{v} = \left[ \frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}} T} \right]^{3/2} \exp\left(- \frac{m v^2}{2k{\text{B}} T} \right) d^3\mathbf{v} ] where:

- (m) is the particle mass,

- (k_{\text{B}}) is the Boltzmann constant,

- (T) is the thermodynamic temperature,

- (v^2 = vx^2 + vy^2 + v_z^2) is the square of the speed [15].

Often, the distribution of the speed (v) (the magnitude of the velocity) is of greater interest. The probability density function for the speed is: [ f(v) = \left[ \frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}} T} \right]^{3/2} 4\pi v^2 \exp\left(- \frac{m v^2}{2k{\text{B}} T} \right) ] This is the form of the chi distribution with three degrees of freedom (one for each spatial dimension) and a scale parameter (a = \sqrt{k_B T / m}) [15].

Table 1: Key Parameters of the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution for Particle Speed.

| Parameter | Mathematical Expression | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution Parameter | ( a = \sqrt{\frac{k_B T}{m}} ) | Scales the distribution based on temperature and particle mass. |

| Mean Speed | ( \langle v \rangle = 2a \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}} ) | The arithmetic average speed of all particles. |

| Root-Mean-Square Speed | ( \sqrt{\langle v^2 \rangle} = \sqrt{3} \, a ) | Proportional to the square root of the average kinetic energy. |

| Most Probable Speed | ( v_p = \sqrt{2} \, a ) | The speed most likely to be observed in a randomly selected particle. |

Physical Interpretation and Relevance to MD

The MB distribution arises naturally from the kinetic theory of gases and is a result of the system maximizing its entropy [15]. In the context of MD, it is essential to recognize that the distribution applies to the velocities of individual particles. Due to the ergodic hypothesis, which states that the time average for a single particle over a long period is equal to the ensemble average over all particles at a single time, the velocity history of a single atom in a properly thermalized simulation will also follow the MB distribution [16]. This justifies the practice of initializing every atom's velocity by independent sampling from this distribution.

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

The theoretical description must be translated into a concrete algorithmic procedure for initializing velocities in an MD simulation.

Sampling Algorithms and Software Commands

The core task is to generate a vector (\mathbf{v} = (vx, vy, vz)) for each atom such that the ensemble of velocities follows the 3D MB distribution. A common and efficient method is to sample each Cartesian component independently from a normal (Gaussian) distribution. This works because the distribution (f(\mathbf{v})) factors into the product of three Gaussian distributions, one for each velocity component [15]. For a single component (e.g., (vx)), the distribution is: [ f(vx) dvx = \sqrt{\frac{m}{2\pi kB T}} \exp\left(- \frac{m vx^2}{2kB T}\right) dvx ] which is a normal distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of (\sigma = \sqrt{\frac{k_B T}{m}}).

Therefore, the practical algorithm is:

- For each atom in the system:

- For each velocity component (vx, vy, v_z):

- Sample a value from a Gaussian distribution with mean (μ = 0) and standard deviation (\sigma = \sqrt{\frac{k_B T}{m}}).

- Assign the vector ((vx, vy, v_z)) to the atom.

Most modern MD software packages automate this process. For example, the AMS package allows users to specify InitialVelocities with Type Random and the RandomVelocitiesMethod set to Boltzmann, which directly implements this sampling procedure [17]. Similarly, the protocol described by Andrews et al. specifies that initial velocities should be "assigned for the desired temperature via a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution" at the beginning of the MD equilibration steps [14].

Integration within a Broader Equilibration Protocol

Velocity initialization is merely the first step in a comprehensive equilibration strategy. A robust protocol, such as the ten-step one proposed by Andrews et al., uses this initialization within a series of carefully orchestrated minimization and relaxation phases [14]. The following workflow diagram illustrates how velocity initialization fits into this broader equilibration framework, which is critical for stabilizing biomolecular systems in explicit solvent.

Diagram 1: MD Equilibration Workflow.

As shown in the diagram, velocities are typically assigned from the MB distribution just before the first constant-volume (NVT) MD simulation step (Step 2 in the referenced protocol) [14]. This step allows the mobile solvent and ions to relax around the still-restrained solute. The subsequent steps gradually release the restraints on the larger biomolecules, allowing the entire system to relax toward a stable equilibrium without experiencing large, destabilizing forces.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Equilibration.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent Model | Provides a physically realistic environment for the solute, mimicking aqueous or specific biological environments. |

| Positional Restraints | Harmonic constraints applied to atomic coordinates during initial stages to prevent unrealistic movements and allow gradual relaxation. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, Langevin) | Regulates the system's temperature by scaling velocities or adding stochastic forces, maintaining the target temperature. |

| Barostat | Regulates the system's pressure, often used in later equilibration stages (NPT ensemble) to achieve the correct density. |

| Steepest Descent Minimizer | An energy minimization algorithm used to remove bad atomic contacts and high initial strain energy from the system. |

Validation and Troubleshooting

After initializing velocities and running the equilibration protocol, it is crucial to verify that the system is evolving correctly and that the velocity distribution remains physically meaningful.

Validating the Velocity Distribution

A direct test involves analyzing the velocities of particles during the simulation. After the system has been allowed to evolve for a sufficient time (post-initialization), a histogram of the velocities for a set of identical atoms (e.g., all water oxygen atoms) should conform to the MB distribution for the target temperature [16]. As one user demonstrated, the velocity data from a simulation of a single atom type can fit the theoretical MB curve almost perfectly, validating the implementation [16]. This test confirms that the thermostat and the dynamics are correctly maintaining the statistical properties of the system.

Common Artifacts and Strategic Considerations

A significant challenge in MD is ensuring that the system has truly reached equilibrium. Convergence is not guaranteed simply by running a simulation for an arbitrary length of time. Some properties, particularly those involving transitions to low-probability conformations, may require very long simulation times to converge, while others (like average distances) may stabilize more quickly [7]. A system can be in "partial equilibrium," where some properties are converged but others are not [7].

Furthermore, the choice of equilibration protocol can profoundly impact the results. For instance, in complex systems like membrane proteins, a poor protocol can lead to artifacts such as artificially increased lipid density in channel pores, which then persist into the production run [18]. This underscores that correct velocity initialization, while vital, is only one component of a larger strategy. The stability of the simulation must be monitored through properties like energy, density, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), with the production phase commencing only after these metrics achieve stable values [14] [7].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have long relied on heuristic, experience-driven approaches for system equilibration, creating a significant source of uncertainty in computational research. This whitepaper examines the emerging paradigm shift toward quantitative, metrics-driven equilibration frameworks. By synthesizing recent advances in initialization methodologies, uncertainty quantification, and thermostatting protocols, we document the movement from traditional rules of thumb to systematically verifiable procedures with clear termination criteria. This transformation, particularly impactful for drug discovery and development professionals, enables more reproducible simulations and reliable prediction of physicochemical properties such as solubility—a critical factor in pharmaceutical efficacy.

In traditional molecular dynamics simulations, equilibration has predominantly been an art rather than a science. The conventional protocol involves energy minimization, heating, pressurization, and an unrestrained simulation period until properties such as energy and Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) appear to stabilize visually [7]. This approach suffers from significant limitations:

- Subjectivity: Determination of equilibration adequacy relies on researcher judgment of when a "plateau" is reached

- Inefficiency: Conservative time allocations often lead to wasted computational resources

- Uncertainty: Lack of quantitative metrics makes reproducibility challenging

- System-specific variability: Optimal protocols differ across molecular systems and force fields

The fundamental question—"how can we determine if the system reached true equilibrium?" [7]—has remained largely unanswered in practice. This ambiguity has profound implications for MD applications in drug development, where unreliable simulations can lead to incorrect predictions of drug solubility, binding affinities, and other physicochemical properties critical to pharmaceutical efficacy.

A Systematic Framework for Equilibration

Position Initialization Methods

The initial configuration of a molecular system significantly influences equilibration efficiency. Silvestri et al. comprehensively evaluated seven distinct initialization approaches, revealing system-dependent performance characteristics [19]:

Table 1: Position Initialization Methods and Their Applications

| Initialization Method | Description | Optimal Use Case | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Random | Random placement of molecules within simulation volume | Low coupling strength systems | Adequate performance at low complexity |

| Uniform Random with Rejection | Random placement with overlap prevention | Moderate coupling systems | Improved stability over basic random |

| Halton/Sobol Sequences | Low-discrepancy quasi-random sequences | Systems requiring uniform sampling | Superior spatial distribution properties |

| Perfect Lattice | Ideal crystalline arrangement | Benchmarking studies | Potentially slow equilibration from artificial order |

| Perturbed Lattice | Slightly disordered crystalline lattice | General purpose initialization | Balanced order and disorder for faster equilibration |

| Monte Carlo Pair Distribution | Sampling based on radial distribution | High coupling strength systems | Physics-informed approach for challenging systems |

Their findings demonstrate that initialization method selection becomes critically important at high coupling strengths, where physics-informed methods (particularly Monte Carlo pair distribution) show superior performance by providing more physically realistic starting configurations [19].

Thermostating Protocols and Temperature Control

Temperature control represents another dimension where quantitative approaches supersede heuristic methods. Research has systematically compared multiple thermostating aspects:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Thermostating Protocols

| Protocol Aspect | Options Compared | Performance Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupling Strength | Strong vs. Weak coupling | Weaker coupling generally requires fewer equilibration cycles | Moderate coupling strengths optimal for balance of control and natural fluctuations |

| Duty Cycle | ON-OFF vs. OFF-ON sequences | OFF-ON sequences outperform ON-OFF for most initialization methods | Begin with thermostats OFF, then activate after initial relaxation |

| Thermostat Type | Berendsen vs. Langevin | Context-dependent performance | Langevin may provide better stochastic properties for certain systems |

| Solvent-Focused Coupling | All atoms vs. solvent-only | Solvent-only coupling provides more physical representation | Couple only solvent atoms to heat bath for more realistic energy transfer [20] |

The solvent-focused thermal equilibration approach represents a particularly significant advancement. By coupling only solvent atoms to the heat bath and monitoring the protein-solvent temperature differential, researchers established a unique measure of equilibration completion time for any given parameter set [20]. This method demonstrated measurably improved outcomes in terms of RMSD and principal component analysis, showing significantly less undesirable divergence compared to traditional approaches.

Quantitative Metrics for Equilibration Assessment

Uncertainty Quantification in Property Prediction

The cornerstone of the quantitative equilibration framework is the direct relationship between temperature stability and uncertainties in transport properties. Silvestri et al. established that temperature forecasting serves as a quantitative metric for system thermalization, enabling researchers to determine equilibration adequacy based on specified uncertainty tolerances in output properties [19]. This approach allows for:

- Termination criteria: Simulations can be stopped when property uncertainties fall below user-defined thresholds

- Resource allocation: Computational resources can be optimized based on desired precision

- Comparative analysis: Different systems and protocols can be objectively evaluated

For drug development applications, this uncertainty quantification is particularly valuable when predicting properties such as diffusion coefficients and viscosity, which influence drug solubility and bioavailability.

Convergence Monitoring in Biological Systems

Long-timescale simulations of biological macromolecules require careful convergence monitoring. The working definition of equilibration for MD simulations has been refined as: "Given a system's trajectory, with total time-length T, and a property Ai extracted from it, and calling 〈Ai〉(t) the average of Ai calculated between times 0 and t, we will consider that property 'equilibrated' if the fluctuations of the function 〈Ai〉(t), with respect to 〈Ai〉(T), remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after some 'convergence time', tc, such that 0 < tc < T" [7].

This conceptual framework acknowledges that different properties converge at different rates, with biologically relevant metrics often converging faster than comprehensive phase space exploration.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Machine Learning Integration with MD Simulations

The quantitative equilibration paradigm enables more reliable integration of MD with machine learning (ML) for property prediction. In pharmaceutical research, this hybrid approach has demonstrated significant value in predicting critical properties such as aqueous solubility [13].

Research has shown that MD-derived properties including Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies (Coulombic_t, LJ), Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv), RMSD, and Average Number of Solvents in Solvation Shell (AvgShell)—when combined with traditional parameters like logP—can predict aqueous solubility with high accuracy (R² = 0.87 using Gradient Boosting algorithms) [13].

This methodology provides:

- Mechanistic insights: MD simulations reveal molecular interactions governing solubility

- Accuracy: Performance comparable to structure-based prediction models

- Transferability: Framework applicable across diverse chemical spaces

Hybrid MD-ML Framework for Physicochemical Properties

The quantitative equilibration philosophy enables the development of robust hybrid frameworks that combine MD simulations with machine learning. For instance, in boiling point estimation of aromatic fluids, MD simulations using OPLS-AA force fields produced density predictions with relative errors below 2% compared to experimental values [21]. This data then trained ML models including Nearest Neighbors Regression, Neural Networks, and Support Vector Regression, with NNR achieving the closest match with MD data [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Solvent-Focused Thermal Equilibration Protocol

Based on the methodology described in PMC4128190 [20], the following protocol provides a quantitative approach to thermal equilibration:

System Preparation:

- Solvate the molecular structure with explicit solvent molecules

- Add neutralizing counterions as required by the system

- Perform energy minimization with protein atoms fixed

- Execute brief MD simulation (50 ps) at target temperature with restrained protein atoms

Equilibration Phase:

- Remove protein atom restraints

- Perform quenched energy minimization

- Couple only solvent atoms to heat bath using Berendsen or Langevin methods

- Maintain constant pressure at 1 atm

- Use temperature coupling time constant appropriate for the system (typically 0.1-1.0 ps)

Monitoring and Completion:

- Calculate average kinetic energy and corresponding temperatures for protein and solvent separately

- Monitor temperature differential between protein and solvent

- Define equilibration completion when temperature differential stabilizes within acceptable range

- Verify that standard deviations obey fluctuation-dissipation theorem

This protocol typically requires 50-100 ps for completion, though system-specific variations should be expected.

Machine Learning Analysis of MD-Derived Properties

For drug solubility prediction applications, the following protocol implements the quantitative framework [13]:

Data Collection and Preparation:

- Compile experimental solubility data (logS) for diverse drug compounds

- Extract octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) from literature

- Establish MD simulation parameters consistent across all compounds

MD Simulation Setup:

- Conduct simulations in isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble

- Use consistent force field (e.g., GROMOS 54a7) across all compounds

- Employ cubic simulation box with appropriate dimensions

- Maintain consistent temperature and pressure control methods

Property Extraction:

- Calculate key properties from trajectories:

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

- Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies

- Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv)

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

- Average number of solvents in solvation shell (AvgShell)

- Ensure sufficient sampling for statistical reliability

Machine Learning Implementation:

- Apply feature selection to identify most predictive properties

- Train multiple ensemble algorithms (Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting)

- Validate models using appropriate cross-validation techniques

- Compare performance with traditional structure-based approaches

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for Quantitative Equilibration

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation package | Versatile open-source software with comprehensive equilibration tools [13] |

| NAMD | MD simulation package | Efficient scaling for large systems; implements various thermostat options [20] |

| Berendsen Thermostat | Temperature coupling | Provides weak coupling to external heat bath [19] [20] |

| Langevin Thermostat | Temperature control | Stochastic thermostat suitable for constant temperature sampling [19] |

| GROMOS 54a7 Force Field | Molecular mechanics parameterization | Provides balanced accuracy for biomolecular systems [13] |

| OPLS-AA Force Field | Molecular mechanics parameterization | Accurate for organic fluids and small molecules [21] |

| Halton/Sobol Sequences | Quasi-random initialization | Superior spatial sampling for initial configurations [19] |

| Monte Carlo Pair Distribution | Physics-informed initialization | Optimal for high coupling strength systems [19] |

The transformation of molecular dynamics equilibration from heuristic art to quantitative science represents a fundamental advancement in computational methodology. By implementing systematic initialization approaches, solvent-focused thermal equilibration, uncertainty quantification, and machine learning integration, researchers can now establish clear termination criteria and reliability metrics for their simulations. This paradigm shift enables more reproducible, efficient, and reliable MD simulations—particularly valuable in drug development where accurate prediction of physicochemical properties directly impacts clinical success. As these quantitative frameworks continue to evolve, they promise to further enhance the role of molecular dynamics as an indispensable tool in pharmaceutical research and development.

Executing Effective Equilibration: Protocols, Thermostats, and Force Fields

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, equilibration is an essential preparatory stage during which the system evolves towards a stable, thermodynamically consistent state before data collection for production runs can commence [1]. This process ensures that results are neither biased by the initial atomic configuration nor deviate from the target thermodynamic state, making it fundamental for obtaining physically meaningful data across fields such as drug development, materials science, and structural biology [1]. Traditionally, the selection of equilibration parameters has been largely heuristic, relying on researcher experience and trial-and-error, which introduces potential inconsistencies across studies [1]. This guide provides a systematic framework for the equilibration process, transforming it from a black-box procedure into a rigorously quantifiable operation with clear diagnostic metrics and termination criteria, directly supporting reproducible research within a broader thesis on MD methodologies.

Theoretical Foundation: From Initialization to Uncertainty Quantification

Position Initialization Methods

The efficiency of the equilibration phase is predominantly determined by the initial configuration of the system in phase space [1]. While initial velocities are readily sampled from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, generating initial positions that approximate the desired thermodynamic state presents a greater challenge [1]. The choice of initialization method significantly impacts the extent of unwanted energy injection and the subsequent duration required for thermalization.

Table 1: Comparison of Position Initialization Methods

| Method | Description | Computational Scaling | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Random (Uni) | Each coordinate sampled uniformly from available space [1]. | O(N) | High-temperature systems; fastest initialization [1]. |

| Uniform Random w/ Rejection (Uni Rej) | Particles resampled if within a specified rejection radius [1]. | > O(N) | General purpose; prevents extreme forces from particle clumping [1]. |

| Low-Discrepancy Sequences (Halton, Sobol) | Uses quasi-random sequences for improved space-filling properties [1]. | O(N) | Systems where uniform random distribution is insufficient [1]. |

| Monte Carlo Pair (MCPDF) | Mesh-based Monte Carlo matching an input pair distribution function [1]. | > O(N) | High-coupling strength systems; physics-informed initialization [1]. |

| Perfect Lattice (BCC Uni) | Particles placed on a regular grid, e.g., Body-Centered Cubic [1]. | O(N) | Low-temperature crystalline or glassy systems [1]. |

| Perturbed Lattice (BCC Beta) | Lattice positions perturbed using a compact beta function [1]. | O(N) | Low-temperature systems requiring slight disorder [1]. |

An Uncertainty Quantification Framework for Equilibration

A modern approach to equilibration recasts the problem as one of uncertainty quantification (UQ) [1]. Instead of guessing an adequate equilibration duration, this framework uses estimates of a target output property (e.g., a transport coefficient like diffusion or viscosity) to determine how much equilibration is necessary. The temperature uncertainty during equilibration is propagated into an uncertainty in the targeted output property using its known or approximated temperature dependence [1]. This provides a clear, criterion-driven success/failure feedback loop, allowing researchers to terminate equilibration once the uncertainty in the desired property falls below a specified tolerance.

Experimental Protocols: A Detailed Workflow

The Core Equilibration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete, iterative workflow from system construction to production simulation, incorporating initialization, energy minimization, and thermalization.

Protocol: Position Initialization and Energy Minimization

The first computational stage involves creating a stable initial atomic configuration.

- Select an Initialization Method: Choose a method from Table 1 appropriate for your system's physical state. For high-coupling strength systems, physics-informed methods like MCPDF or BCC Beta demonstrate superior performance, whereas at low coupling strengths, the choice is less critical [1].

- Execute Energy Minimization: The initial configuration, particularly from random placement, may contain high-energy overlaps. Energy minimization (steepest descent, conjugate gradient) is used to relieve these steric clashes and find a local energy minimum, providing a mechanically stable starting point for dynamics.

- Initialize Velocities: Assign initial velocities to all particles by random sampling from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature [1].

Protocol: System Thermalization and Thermostating

This protocol brings the system to the target temperature.

- Apply Thermostat: Couple the system to a thermostat to enforce the target temperature. Common choices include Berendsen (for rapid initial heating/cooling) and Langevin (stochastic) thermostats [1].

- Thermostat Coupling Strength: Weaker thermostat coupling generally requires fewer equilibration cycles but may allow for larger temperature fluctuations. The strength must be tuned to be strong enough to maintain temperature without artificially overdamping system dynamics [1].

- Thermostating Duty Cycle: An OFF-ON sequence (allowing the system to evolve without a thermostat initially, then applying it) typically outperforms an ON-OFF sequence for most initialization methods [1].

- Monitor System Stability: Run the simulation while monitoring the instantaneous and average temperature and total system energy. The system is considered thermally stable when these metrics fluctuate around a steady-state value.

Protocol: Equilibration Sufficiency and Uncertainty Quantification

This final protocol provides a quantitative check to determine when equilibration is complete.

- Select a Target Property: Identify a key output property of interest for your study, such as the self-diffusion coefficient or shear viscosity [1].

- Forecast Temperature Stability: Use the recent temperature time-series to forecast its long-term stability. This serves as a quantitative metric for system thermalization [1].

- Propagate to Property Uncertainty: Use an approximate model of your target property's temperature dependence to translate the forecasted temperature uncertainty into an uncertainty for the property itself [1].

- Check Against Tolerance: If the calculated uncertainty for the target property is below a pre-specified tolerance, equilibration is deemed sufficient. If not, the thermalization run should be extended [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools for MD Equilibration

| Item Name | Function/Description | Role in Equilibration Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| drMD | An automated pipeline for running MD simulations using the OpenMM toolkit [3]. | Simplifies the entire equilibration and production process for non-experts, handling routine procedures automatically and providing real-time progress updates [3]. |

| OpenMM | A high-performance toolkit for molecular simulation, often used as the engine for drMD and other pipelines [3]. | Provides the underlying computational libraries for executing energy minimization, thermostating, and dynamics with high efficiency on various hardware platforms. |

| ReaxFF | A reactive force field that enables dynamic charge equilibration and modeling of bond formation/breakage [6]. | Critical for simulating reactive processes, such as in corrosion; requires specialized equilibration to account for fluctuating atomic charges [6]. |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | Machine learning models, such as LSTMs, trained with physics-informed loss functions [6]. | Can act as a surrogate to accelerate charge estimation in reactive MD by orders of magnitude, adhering to physical constraints like charge neutrality [6]. |

| Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) | A descriptor used to characterize the local atomic environment [6]. | Used in machine-learning accelerated workflows to featurize atomic environments for training surrogate models that predict properties like partial charge [6]. |

Advanced Topics and Optimization Strategies

Diagnosing Equilibration with Microfield Analysis

Beyond monitoring global properties like temperature, analysis of local microfield distributions can provide diagnostic insights into the system's thermal behavior during equilibration [1]. This involves examining the distribution of electric or force fields experienced by individual particles due to their neighbors. A stable, reproducible microfield distribution is a strong indicator that the system has reached local thermodynamic equilibrium, often providing a more sensitive metric than global averages alone.

Leveraging Machine Learning for Enhanced Workflows

Machine learning (ML) is increasingly used to optimize MD workflows. For reactive force fields like ReaxFF, where charge equilibration is a computational bottleneck, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks can be trained to predict charge density evolution based on local atomic environments [6]. When combined with a physics-informed loss function that enforces constraints like charge neutrality, these models can achieve errors of less than 3% compared to MD-obtained charges while being generated two orders of magnitude faster [6]. This approach, coupled with Active Learning (AL) to efficiently build training datasets, allows for rapid screening and extends the practical timescales of simulations for phenomena like corrosion [6].

Within the framework of molecular dynamics (MD) research, the equilibration process is a critical, yet often heuristic, procedure necessary for driving a system toward a stable, thermodynamically consistent state before data collection commences. The efficiency and success of this phase are largely determined by two factors: the initial configuration of the system and the algorithms used to control its thermodynamic state [1]. This article focuses on the latter, providing a technical deep-dive into the thermostat algorithms that manage the system's temperature. In classical MD simulations, the velocity distribution is readily initialized by sampling from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. However, generating initial positions consistent with the target thermodynamic state presents a greater challenge, necessitating a thermalization phase where the system is driven to the required state primarily through the application of thermostats [1]. The selection of an appropriate thermostat is therefore not merely a technicality but a fundamental decision that influences the accuracy of sampling, the reliability of dynamical properties, and the overall computational efficiency of the simulation.

Despite their importance, choices regarding thermostating protocols—including algorithm selection, coupling strength, and cycling strategies—often rely on experience and trial-and-error, leading to potential inconsistencies across studies [1]. A systematic methodology is needed to transform equilibration from an open-ended, heuristic process into a rigorously quantifiable procedure with clear termination criteria. This article aims to provide a comprehensive comparison of prominent thermostat algorithms, including Berendsen, Langevin, Nosé-Hoover, and advanced stochastic methods, to establish clear guidelines for their application within the molecular dynamics equilibration process.

Theoretical Foundations of Temperature Control

The Purpose of a Thermostat in MD