Beyond Purpose and Design: Pedagogical Approaches to Navigate Teleological Thinking in Drug Development

This article addresses the critical challenge of teleological thinking—the attribution of purpose or conscious design to natural phenomena—in the education of drug development professionals.

Beyond Purpose and Design: Pedagogical Approaches to Navigate Teleological Thinking in Drug Development

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of teleological thinking—the attribution of purpose or conscious design to natural phenomena—in the education of drug development professionals. It explores the foundational theories of teleological reasoning, presents evidence-based pedagogical methods to counteract these cognitive biases, and provides strategies for troubleshooting common learning obstacles. By comparing traditional and modern instructional approaches, the article offers a framework for cultivating the rigorous, evidence-based thinking essential for navigating the complexities of clinical pharmacology, new drug development, and patient safety.

Understanding Teleological Thinking: Origins and Impact in Scientific Reasoning

Teleology, derived from the Greek telos (meaning 'end', 'aim', or 'goal') and logos (meaning 'explanation' or 'reason'), is a branch of causality that explains something by its purpose or final cause, as opposed to its antecedent cause [1] [2]. This philosophical concept contends that natural entities and processes are directed toward specific ends. In classical philosophy, Aristotle argued that individual organisms have inherent, specific goals; for example, an acorn's intrinsic telos is to become a fully grown oak tree [1] [3]. This perspective suggests that nature is imbued with intentionality, a view that became controversial during the modern scientific era.

In contemporary scientific discourse, particularly in life sciences education and research, teleological explanations often emerge as a cognitive bias—a systematic pattern of deviation from normative, rational judgment [4]. This bias manifests as the tendency to attribute purpose to natural phenomena, such as claiming that "species evolve to adapt" or "genes exist to make more copies of themselves" [5]. While sometimes serving as an adaptive heuristic for rapid decision-making, this cognitive pattern can lead to perceptual distortions and inaccurate judgments when applied to mechanistic scientific explanations [4]. Within pedagogical frameworks, understanding and mitigating this bias is crucial for accurate scientific reasoning.

Philosophical Foundations and Historical Development

Classical Origins

The conceptual foundations of teleology were established in Western philosophy by Plato and Aristotle. In Plato's Phaedo, Socrates argues that true explanations for physical phenomena must be teleological, distinguishing between necessary material causes and sufficient final causes that explain why something exists in its best possible state [1]. Plato viewed the universe as unfolding optimally despite its flaws, with sensible objects being imperfect versions of perfect forms they aspire to become [3].

Aristotle subsequently developed a more systematic teleological framework through his doctrine of four causes, which gives special place to the telos or "final cause" of each thing [1]. Rejecting Plato's realm of forms, Aristotle instead proposed that organisms contain principles of change ("natures") internal to themselves that direct them toward their specific ends, which can be discovered through empirical observation and study [3]. He criticized pre-Socratic materialists like Democritus for reducing all natural operations to mere necessity while neglecting the final causes that explain why things are "for the sake of what is best in each case" [1].

Modern Transformations

During the 17th century, philosophers including René Descartes, Francis Bacon, and Thomas Hobbes wrote in opposition to Aristotelian teleology, favoring a mechanistic view of nature that rejected the notion of inherent purposes [1]. Bacon specifically warned that the "handling of final causes, mixed with the rest in physical inquiries, hath intercepted the severe and diligent inquiry of all real and physical causes" [1].

In the late 18th century, Immanuel Kant acknowledged the limitations of purely mechanistic explanations in biology, noting there would never be a "Newton of the blade of grass" because science could not explain how life develops from inanimate matter [1]. Kant treated teleology as a necessary subjective perception for human understanding rather than an objective determining factor in nature [1].

Subsequently, G.W.F. Hegel opposed Kant's view, arguing for legitimate "high" intrinsic teleology where organisms and human societies determine their actions toward self-preservation and freedom [1]. This Hegelian framework influenced Karl Marx's teleological terminology describing societal advancement through class conflict toward an established classless commune [1].

Table 1: Major Philosophical Perspectives on Teleology

| Philosopher | Period | Core Concept | View on Natural Teleology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plato | Classical | Realm of Forms; objects aspire to perfect forms | Universe unfolds optimally despite flaws [3] |

| Aristotle | Classical | Four causes with special place for final cause | Internal "natures" direct organisms toward ends [1] [3] |

| Bacon/Descartes | 17th Century | Mechanistic view of nature | Rejected inherent purposes as impediment to science [1] |

| Kant | Late 18th Century | Subjective regulative principle | Necessary for human understanding but not objectively real [1] |

| Hegel | 19th Century | Historical realization of ideas | Legitimate intrinsic teleology in organisms/societies [1] |

Teleology as Cognitive Bias in Scientific Reasoning

Mechanisms of Cognitive Bias

Cognitive biases represent systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where individuals create a "subjective reality" that dictates their behavior [4]. When making judgments under uncertainty, people rely on mental shortcuts or heuristics, which provide swift estimates about uncertain occurrences. The representativeness heuristic illustrates this tendency, where individuals judge likelihood by how much an event resembles a typical case, potentially activating stereotypes and inaccurate judgments [4].

Teleological thinking functions as a cognitive bias through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Anchoring bias: The initial presentation of a teleological explanation creates preconceived ideas that adjust insufficiently to later mechanistic information [4].

- Confirmation bias: Once teleological frameworks are established, individuals selectively search for or interpret information that confirms these preconceptions while discrediting contradictory evidence [4].

- Status quo bias: The intuitive appeal of purpose-based explanations creates resistance toward adopting more complex, mechanistic accounts, particularly when teleological thinking offers apparent explanatory satisfaction [4].

Empirical Evidence and Research Paradigms

Research in cognitive science has demonstrated the prevalence and persistence of teleological biases through various experimental paradigms:

- The "Linda Problem": This classic demonstration of the representativeness heuristic shows how individuals prioritize seemingly representative information over statistical probability, analogous to how teleological thinking favors purpose-based over causal-mechanistic explanations [4].

- Biological reasoning studies: Cross-cultural research reveals that children and adults spontaneously generate teleological explanations for natural phenomena, such as "rains to water plants" or "rivers flow to reach the ocean" [5].

- Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT): This instrument measures individuals' susceptibility to cognitive biases, with lower scores correlating with stronger teleological thinking tendencies [4].

Table 2: Common Teleological Statements in Scientific Discourse and Their Mechanistic Corrections

| Domain | Teleological Statement | Mechanistic Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Biology | "Species evolve to adapt to their environments." [5] | "Natural selection acts on random variations, favoring traits that enhance survival and reproduction." |

| Cell Biology | "The primary mission of the red blood cell is to transport oxygen." [5] | "Red blood cells contain hemoglobin molecules that bind and release oxygen through biochemical processes." |

| Genetics | "Virus mutations are to escape antibodies." [5] | "Random viral mutations generate variants; those with reduced antibody affinity are selectively amplified." |

| Physiology | "Cells die for a higher good." [5] | "Programmed cell death occurs through regulated molecular pathways that provide evolutionary advantages." |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Teleological Cognition

Protocol 1: Teleological Reasoning Assessment in Biology Education

Purpose: To quantify and characterize teleological reasoning patterns among life sciences students and professionals.

Materials:

- Stimulus set of 20 biological phenomena with paired teleological and mechanistic explanations

- Eye-tracking apparatus (e.g., Tobii Pro Fusion)

- fMRI-compatible response system (for neuroimaging variant)

- Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) questionnaire

- Analysis software (R, Python, or MATLAB with appropriate toolboxes)

Procedure:

- Participant Screening: Recruit subjects with varying expertise levels (novices to experts) using predefined criteria.

- Pre-assessment: Administer CRT to establish baseline cognitive style.

- Stimulus Presentation: Display biological scenarios in randomized order using E-Prime or PsychoPy.

- Response Recording: Collect explanation preferences (teleological/mechanistic) and response times.

- Eye-tracking: Monitor gaze patterns during decision process.

- Post-task Interview: Conduct structured interviews to elucidate reasoning strategies.

- Data Analysis: Compute teleological preference scores and correlate with expertise measures.

Validation Metrics:

- Internal consistency (Cronbach's α > 0.8)

- Test-retest reliability (r > 0.7)

- Discriminant validity between expertise groups (p < 0.01)

Protocol 2: Intervention Efficacy for Bias Mitigation

Purpose: To evaluate pedagogical strategies for reducing teleological bias in scientific reasoning.

Experimental Design: Randomized controlled trial with pre-test/post-test measures.

Intervention Conditions:

- Condition A: Explicit instruction on teleological bias with counterexamples

- Condition B: Case-based learning with mechanistic reasoning emphasis

- Condition C: Contrasting cases (teleological vs. mechanistic explanations)

- Control: Standard curriculum without bias addressing

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment: Administer Teleological Reasoning Assessment (Protocol 1) to all participants.

- Randomization: Assign participants to conditions using stratified random sampling by prior knowledge.

- Intervention Delivery: Implement 4-week training modules (2 sessions/week, 90 minutes each).

- Post-intervention Assessment: Readminister Teleological Reasoning Assessment.

- Delayed Post-test: Conduct follow-up assessment at 3-month interval.

Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Change in teleological explanation selection

- Secondary: Response latency, conceptual understanding scores

- Tertiary: Transfer to novel biological scenarios

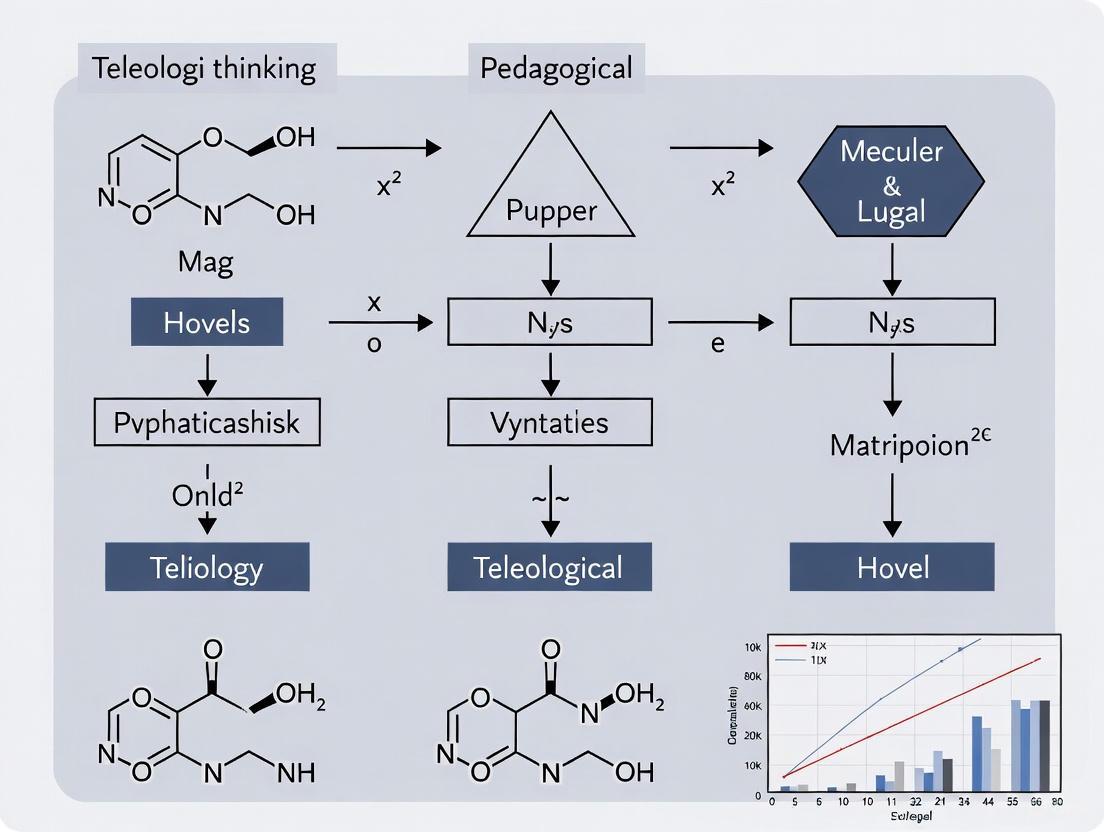

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating teleological bias interventions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Cognitive Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials for Teleological Cognition Research

| Item | Specifications | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Presentation Software | E-Prime 3.0, PsychoPy, SuperLab | Precise control of stimulus timing and response collection for cognitive tasks |

| Eye-Tracking System | Tobii Pro Fusion (250Hz), EyeLink 1000 Plus | Monitoring gaze patterns to identify attentional biases during reasoning tasks |

| Neuroimaging Apparatus | 3T fMRI with compatible response system, fNIRS portables | Identifying neural correlates of teleological vs. mechanistic reasoning |

| Cognitive Assessment Tools | Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT), AWMA-2, Need for Cognition Scale | Measuring individual differences in cognitive style and working memory capacity |

| Data Analysis Platforms | R Statistics with lme4, brms; Python with SciPy, PyMC3 | Implementing multilevel models for nested data and Bayesian hypothesis testing |

| Qualitative Analysis Software | NVivo 14, MAXQDA | Systematic coding of interview transcripts and open-ended responses |

Analytical Framework and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Metrics for Teleological Bias

Research should employ multiple converging measures to quantify teleological bias:

- Teleological Preference Score: Percentage of teleological explanations selected across stimulus set (target: <15% in expert scientists)

- Response Latency: Decision time differences between teleological and mechanistic choices (typically faster for teleological responses)

- Confidence Ratings: Self-reported certainty in explanations (often higher for teleological selections despite inaccuracy)

- Conceptual Integration: Ability to connect biological concepts across domains without teleological bridging

Statistical Modeling Approaches

Advanced statistical methods are required to analyze complex cognitive data:

- Multilevel regression models account for nested data (responses within participants within institutions)

- Path analysis tests mediating factors between cognitive style and teleological reasoning

- Bayesian hierarchical models quantify evidence for absence of effects (null results)

- Growth curve modeling tracks changes in reasoning patterns across intervention periods

Figure 2: Conceptual path model of relationships between cognitive factors and teleological bias.

Application Notes for Research and Pedagogy

Implementation Guidelines for Science Education

Based on empirical findings, the following evidence-based practices can mitigate teleological biases:

Explicit Refutation: Directly address and counter teleological explanations rather than simply presenting correct information.

Mechanistic Focus: Emphasize causal mechanisms in biological processes through detailed pathway analysis.

Contrasting Cases: Present side-by-side comparisons of teleological and mechanistic explanations with explicit discussion of their differences.

Metacognitive Training: Teach students to monitor their own reasoning for teleological patterns using self-explanation prompts.

Historical Context: Discuss historical examples of teleological thinking in science and how they were overcome through mechanistic understanding.

Domain-Specific Considerations

Different scientific disciplines require tailored approaches:

- Evolutionary Biology: Focus on random variation and selective retention rather than directional adaptation.

- Biochemistry: Emphasize molecular interactions and thermodynamic principles over "design" or "purpose."

- Physiology: Highlight homeostatic mechanisms and regulatory feedback loops without intentional framing.

- Ecology: Explain ecosystem dynamics through material and energy flows rather than balance or harmony concepts.

Effective intervention requires sustained engagement with these concepts across the curriculum rather than isolated treatment in single sessions. Longitudinal tracking indicates significant improvement in mechanistic reasoning emerges after approximately 20-30 hours of targeted instruction with distributed practice.

Identifying Teleological Pitfalls in Drug Development Narratives

Teleological thinking—the attribution of purpose or directed goals to natural phenomena—functions as a significant epistemological obstacle in scientific reasoning, particularly in complex fields like drug development [6]. This cognitive bias imposes substantial restrictions on learning and interpreting biological processes, often leading researchers to intuitively assume that "bacteria mutate in order to become resistant to antibiotics" or that "drug candidates should demonstrate perfect specificity" [6]. Within pharmaceutical research and development, these implicit teleological narratives can misdirect experimental design, data interpretation, and strategic decision-making, potentially contributing to the 90% failure rate observed in clinical drug development [7].

This Application Note provides a structured framework for identifying and mitigating teleological reasoning through specific experimental protocols, quantitative analysis methods, and visualization tools, framed within a pedagogical approach to teleological thinking research.

Quantitative Landscape of Drug Development Challenges

A clear understanding of the quantitative realities of drug development establishes the necessary context for identifying where teleological narratives most frequently distort decision-making.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Challenges in Contemporary Drug Development

| Development Challenge | Statistical Measure | Impact & Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Success Rate | ~7% approval rate from preclinical stages [8] | 8.5 drugs must enter development for one approval [8] |

| Development Timeline | 11-12 years from discovery to approval [8] | Creates disconnect between "slow motion" development and rapid new biological discoveries [8] |

| Development Cost | Out-of-pocket: ~$1.4B per compound; Fully loaded: ~$2.6B [8] | Contributes to high-stakes decision environment where cognitive biases thrive [8] |

| Clinical Trial Demands | Patient arms increased from 100-250 (1990s) to 500-1000 patients [8] | Driven by need for statistical power to detect smaller marginal benefits in overall survival [8] |

Protocol 1: Identifying Teleological Language in Research Documentation

Experimental Purpose and Pedagogical Context

This protocol establishes a systematic content analysis methodology to detect and classify teleological statements within drug development documentation (research papers, project proposals, internal reports). The protocol treats teleological language not merely as erroneous thinking but as an epistemological obstacle that is both functional and transversal, requiring metacognitive vigilance rather than simple elimination [6].

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Teleological Language Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Text Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo, Atlas.ti) | Facilitates systematic coding and quantification of teleological language patterns across large document corpora. |

| Structured Codebook | Defines operational criteria for identifying teleological phrasing with examples and counterexamples. |

| Annotation Platform | Enables multiple independent raters to code documents for inter-rater reliability assessment. |

| Reference Documentation | Guidelines for reporting experimental protocols to establish normative, non-teleological language benchmarks [9]. |

Experimental Workflow and Procedure

The experimental workflow for this protocol follows a structured, sequential process:

Step 1: Document Collection and Preparation

- Assemble target documents (hypotheses, study designs, conclusions) from research projects

- Remove identifying information to prevent rater bias

- Establish control documents using explicitly non-teleological writing

Step 2: Teleological Codebook Development

- Define explicit coding categories:

- Strong Teleology: Explicit "in order to" or "for the purpose of" statements

- Weak Teleology: Implicit purposeful language ("designed to," "intended to")

- Need-Based Reasoning: "Bacteria needed to become resistant" [6]

- Anthropomorphism: Attributing human-like intentionality to biological systems

- Provide multiple examples and counterexamples for each category

Step 3: Rater Training and Calibration

- Train multiple independent raters using the codebook

- Conduct calibration sessions until inter-rater reliability >0.8 (Cohen's Kappa)

- Establish consensus process for resolving coding discrepancies

Step 4: Quantitative and Diagnostic Analysis

- Calculate descriptive statistics for teleology frequency and distribution [10]

- Perform diagnostic analysis to identify relationships between teleological language and specific development phases [11]

- Use correlation analysis to examine connections between teleological language and project outcomes

Protocol 2: Testing the Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity-Activity Relationship (STAR) to Counteract Compound Selection Bias

Experimental Purpose and Pedagogical Context

This protocol addresses the teleological pitfall of overemphasizing drug potency and specificity while overlooking tissue exposure and selectivity—a form of "potency myopia" that stems from implicit design assumptions about drug behavior [7]. The STAR framework provides a systematic methodology to rebalance candidate evaluation by explicitly integrating tissue pharmacokinetics with activity metrics.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for STAR Protocol Implementation

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Tissue-Specific Biomarkers | Enable measurement of target engagement and exposure in disease-relevant tissues. |

| Companion Diagnostics | Developed in parallel from program start to identify patient populations most likely to respond [8]. |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS/MS systems for quantifying drug concentrations in multiple tissue compartments. |

| PD Biomarker Assays | Measure proximal pathway engagement rather than assuming intended biological effects. |

STAR Classification and Experimental Workflow

The STAR framework classifies drug candidates into four distinct categories based on integrated pharmacological properties:

Step 1: Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Profiling (STR)

- Determine drug concentrations in disease-relevant tissues versus plasma over time

- Calculate tissue-to-plasma ratios across candidate compounds

- Assess selectivity for target tissues over sites of potential toxicity

Step 2: Integrated STAR Classification

- Class I Candidates: High specificity/potency + high tissue exposure/selectivity

- Development Path: Proceed with low-dose regimens predicting superior efficacy/safety

- Class II Candidates: High specificity/potency + low tissue exposure/selectivity

- Development Path: Requires high doses with expected toxicity; cautious evaluation

- Class III Candidates: Adequate specificity/potency + high tissue exposure/selectivity

- Development Path: Often overlooked; low-dose regimens with manageable toxicity

- Class IV Candidates: Low specificity/potency + low tissue exposure/selectivity

- Development Path: Early termination recommended [7]

Step 3: Dose Route and Schedule Optimization

- Challenge teleological convenience assumptions (e.g., "all drugs should be oral")

- Match dose route to therapeutic window considerations

- Model species differences in PK/PD to select human dosing schedules [12]

Quantitative Data Analysis Methods for Teleological Pitfall Identification

Descriptive and Inferential Statistical Framework

Robust quantitative analysis is essential for moving beyond teleological interpretations of drug development data. The statistical approach should progress from descriptive to inferential methods:

Table 4: Quantitative Analysis Methods for Drug Development Data

| Analysis Type | Statistical Methods | Application to Teleological Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Analysis | Mean, median, mode, standard deviation, skewness [10] | Characterize central tendency and distribution of key efficacy/toxicity parameters |

| Diagnostic Analysis | Correlation analysis, regression modeling [11] | Identify relationships between tissue exposure metrics and clinical outcomes |

| Predictive Analysis | Time series analysis, cluster analysis [11] | Forecast clinical outcomes based on preclinical STAR classification |

| Inferential Statistics | T-tests, ANOVA, chi-square tests [10] [11] | Test hypotheses about differences between STAR classes |

Statistical Analysis of Clinical Trial Endpoints

The interpretation of clinical endpoints requires careful statistical framing to avoid teleological narratives:

Overall Survival (OS) Analysis

- Recognize that absolute survival improvements have different clinical meanings based on baseline expectations (2-month improvement from 8→10 months vs. 29→31 months) [8]

- Account for confounding effects of subsequent therapy lines when interpreting OS data [8]

Progression-Free Survival (PFS) Considerations

- Understand trade-offs between "cleaner" PFS endpoints and complexities of measurement timing, radiographic methods, and dropout patterns [8]

- Ensure consistent assessment criteria across treatment arms to prevent interpretation bias

Visualization and Metacognitive Tools for Teleological Vigilance

Biomarker-Driven Development Workflow

The integration of biomarker strategies provides a concrete methodology for replacing teleological assumptions with empirical data:

Metacognitive Vigilance Framework

Developing metacognitive vigilance involves creating explicit awareness of teleological reasoning patterns:

Declarative Knowledge Component

- Educate researchers about teleology as an epistemological obstacle rather than simply "wrong thinking" [6]

- Distinguish between legitimate functional language in biology and problematic teleological assumptions

Procedural Knowledge Component

- Implement structured checkpoints in development workflows to challenge teleological narratives

- Establish "premortem" exercises where teams identify how teleological assumptions could lead to failure

Conditional Knowledge Component

- Develop researchers' ability to recognize contexts where teleological thinking is most likely to influence decisions (e.g., candidate selection, dose optimization) [6]

- Create decision aids that explicitly counter teleological convenience biases (e.g., automatic preference for oral dosing) [12]

These application notes and experimental protocols provide a structured approach to identifying and mitigating teleological pitfalls throughout the drug development process. By implementing systematic content analysis, adopting the STAR framework for candidate selection, applying appropriate quantitative methods, and developing metacognitive vigilance, research teams can replace implicit design narratives with empirical, evidence-based decision-making. This pedagogical approach transforms teleological thinking from an unconscious epistemological obstacle into a recognized and managed dimension of research quality, potentially contributing to improved success rates in pharmaceutical development.

The Consequences of Teleological Reasoning for Clinical Judgment and Patient Safety

Application Notes: Understanding Teleological Reasoning in Clinical Contexts

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Teleological reasoning represents a cognitive bias wherein natural phenomena are explained by reference to purposes, goals, or functions rather than antecedent causes [13]. In clinical practice, this manifests as the tendency to assume that biological processes, symptoms, or disease manifestations occur "for" a particular purpose or end-state. This reasoning style contrasts with evidence-based mechanistic understanding and poses significant challenges to accurate clinical judgment [6] [14].

Research indicates that teleological reasoning is a universal cognitive tendency, present even in experts under conditions of cognitive load or time pressure [13] [15]. In clinical contexts, this can lead to misconceptions such as "bacteria mutate in order to become resistant to antibiotics" or "the body creates fever to fight infection" without understanding the underlying mechanistic processes of random mutation and selection or inflammatory cytokine release [6]. These teleological explanations fundamentally misunderstand the blind, non-purposeful nature of natural selection and physiological processes.

Impact on Clinical Judgment and Decision-Making

Teleological reasoning adversely affects clinical judgment through multiple pathways. It can lead to premature closure in diagnostic reasoning, where clinicians attribute symptoms to apparent "purposes" without fully investigating underlying mechanisms [16] [17]. This cognitive bias may also reinforce essentialist thinking about diseases as having fixed "natures" or predetermined trajectories, potentially limiting consideration of individual patient variations and comorbidities [6].

The situated nature of clinical reasoning—occurring within complex social relationships involving patients, families, and healthcare teams—makes it particularly vulnerable to teleological shortcuts [16]. When cognitive resources are stretched, clinicians may default to teleological explanations, especially for complex pathophysiology or emergent presentations [15]. This is particularly problematic in nursing practice, where clinical judgment directly impacts patient safety through monitoring, surveillance, and intervention decisions [17] [18].

Consequences for Patient Safety

Poor clinical judgment resulting from teleological reasoning can lead to diagnostic errors, inappropriate treatment decisions, and failure to recognize deteriorating patients [17]. Specific patient safety risks include:

- Misinterpretation of clinical cues: Attributing symptoms to incorrect purposes may lead to missed identification of salient information [19]

- Inadequate intervention planning: Teleological explanations may support incorrect causal models of disease, leading to ineffective or harmful interventions [18]

- Reduced situational awareness: Purpose-based reasoning can limit anticipation of potential complications or alternative explanations for clinical presentations [16] [17]

The NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model emphasizes that sound clinical judgment requires cognitive skills that may be compromised by teleological biases, directly impacting patient safety outcomes [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Teleological Reasoning in Clinical Populations

Objective

To quantify the prevalence and strength of teleological reasoning biases among healthcare professionals and students, and to correlate these measures with clinical judgment performance.

Background and Rationale

Teleological reasoning persists in educated adults and may resurface under cognitive constraints [13] [15]. Understanding how this bias manifests in clinical populations is essential for developing targeted interventions. This protocol adapts established instruments from cognitive psychology to clinical contexts.

Materials and Equipment

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Teleological Reasoning Assessment

| Item | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Teleological Reasoning Assessment Tool (TRAcT) | Measures endorsement of teleological explanations | 15-item Likert scale assessing agreement with statements like "The body creates fever to fight infection" |

| Clinical Judgment Simulation Scenarios | Standardized clinical cases with embedded teleological distractors | Virtual patient cases with purposeful vs. mechanistic explanation options |

| Cognitive Load Manipulation Tasks | Concurrent tasks to simulate clinical workload | Dual-task paradigm with clinical reasoning under time pressure or simultaneous calculation tasks |

| Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Assess understanding of non-teleological processes | Modified for clinical contexts (e.g., antibiotic resistance evolution) [13] [14] |

| Eye-Tracking Equipment | Measures attention to teleologically salient cues | Fixation patterns on purposeful vs. mechanistic clinical information |

Procedure

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses, advanced practitioners) and students from academic medical centers and training programs. Target sample: N=200 with balanced representation across experience levels.

- Baseline Assessment: Administer TRAcT and CINS instruments in controlled conditions without time pressure.

- Cognitive Load Condition: Randomize participants to speeded (time-limited) versus untimed conditions for clinical judgment simulations.

- Scenario Administration: Present standardized clinical cases through high-fidelity simulation platforms (e.g., Body Interact) with embedded teleological reasoning challenges [18].

- Process Tracing: Collect think-aloud protocols, eye-tracking data, and response times during scenario completion.

- Performance Metrics: Score responses based on accuracy of mechanistic understanding, appropriate intervention selection, and avoidance of teleological explanations.

Data Analysis

- Calculate teleological reasoning scores from TRAcT instrument

- Correlate teleological reasoning scores with clinical judgment accuracy under different cognitive load conditions

- Use regression models to identify predictors of teleological reasoning (experience, specialty, cognitive style)

- Analyze verbal protocols for teleological language patterns

- Examine eye-tracking metrics for attention allocation to teleologically salient information

Protocol 2: Intervention Study for Mitigating Teleological Bias

Objective

To develop and test educational interventions targeting teleological reasoning biases in clinical judgment, and to measure effects on patient safety indicators.

Background and Rationale

Based on the framework of González Galli et al., effective regulation of teleological reasoning requires metacognitive vigilance—knowledge of teleology, awareness of its expressions, and deliberate regulation of its use [6]. This protocol tests whether explicit instruction challenging teleological reasoning improves clinical judgment outcomes.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Materials for Teleological Bias Intervention

| Item | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metacognitive Vigilance Training Modules | Structured curriculum for recognizing and regulating teleological bias | Case-based workshops highlighting mechanistic vs. teleological explanations |

| Reflection and Debriefing Guides | Facilitate conscious examination of reasoning processes | Structured templates for analyzing clinical decisions using Tanner's Model [19] |

| Clinical Reasoning Simulation Platform | Provide practice with feedback in controlled environments | Body Interact or similar virtual patient systems with teleological reasoning analytics [18] |

| Teleological Reasoning Assessment | Pre-post measure of intervention effectiveness | Adapted instruments from Kelemen et al. with clinical scenarios [13] [20] |

| Patient Safety Metrics | Outcome measures for intervention impact | Standardized indicators: medication errors, diagnostic accuracy, complication detection |

Procedure

- Participant Recruitment and Baseline Assessment: Recruit nursing and medical students (N=150). Assess baseline teleological reasoning (TRAcT) and clinical judgment (Clinical Judgment Simulation Test).

- Randomization: Randomly assign participants to intervention group (metacognitive vigilance training) or control group (standard clinical education).

- Intervention Delivery:

- Module 1: Explicit instruction on teleological reasoning, distinguishing warranted and unwarranted teleology in clinical contexts

- Module 2: Contrasting cases highlighting differences between teleological and mechanistic explanations

- Module 3: Cognitive forcing strategies to recognize and counter teleological biases

- Module 4: Reflective practice using Tanner's Model to analyze clinical judgments [19]

- Simulation Practice: Both groups complete identical clinical simulations, with intervention group receiving specific feedback on teleological reasoning.

- Post-Intervention Assessment: Administer TRAcT and clinical judgment measures immediately post-intervention and at 3-month follow-up.

- Outcome Measurement: Track patient safety indicators in subsequent clinical rotations (for advanced students) or through standardized patient encounters.

Data Analysis

- Mixed ANOVA to assess group × time interactions on teleological reasoning scores

- Regression models predicting clinical judgment accuracy from teleological reasoning reduction

- Qualitative analysis of reflective journals for metacognitive vigilance development

- Correlation between teleological reasoning reduction and patient safety metrics

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Evidence for Teleological Reasoning Prevalence and Impact

Table 3: Quantitative Findings on Teleological Reasoning in Educational Contexts

| Study Reference | Population | Teleological Reasoning Measure | Key Findings | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnes et al. (2022) [13] | Undergraduate students (N=83) | Teleological Statements Rating | Decreased teleological reasoning after direct instruction | p ≤ 0.0001 |

| Kelemen et al. (2013) [13] | Physical scientists | Forced-choice teleological explanations | 75% endorsed teleological statements under time pressure | Large effect (d = 0.85) |

| Kelemen (1999) [20] | Preschool children | Function attribution tasks | Children broadly attribute functions to natural objects | Significant age trend |

| Wingert & Hale (2021) [13] | Undergraduate biology students | Teleological reasoning inventory | Anti-teleological pedagogy improved evolution understanding | Medium to large effects |

| Spiegel et al. (2012) [14] | Undergraduate students | CINS and teleology measures | Teleological reasoning predicted natural selection understanding | β = -0.42 |

Relationship Between Teleological Reasoning and Clinical Judgment

Table 4: Correlates of Teleological Reasoning in Clinical Domains

| Variable | Relationship with Teleological Reasoning | Clinical Judgment Impact | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive load | Positive correlation | Increased diagnostic errors under time pressure | [15] |

| Clinical experience | Negative correlation | Experts show more mechanistic reasoning patterns | [16] |

| Metacognitive training | Negative correlation | Explicit instruction reduces bias | [6] |

| Patient safety outcomes | Positive correlation | Associated with judgment errors | [17] [18] |

| Scientific understanding | Negative correlation | Better knowledge protects against teleology | [14] |

Implementation Guidelines for Research and Education

Integration with Existing Clinical Education Frameworks

The Tanner Clinical Judgment Model provides an effective framework for addressing teleological reasoning in clinical education [19]. Each domain of the model can be leveraged to mitigate teleological bias:

- Noticing: Train attention to mechanistic causal relationships rather than apparent purposes

- Interpreting: Explicitly contrast teleological and mechanistic explanations for clinical phenomena

- Responding: Develop interventions based on evidence-based mechanisms rather than assumed purposes

- Reflecting: Metacognitive analysis of reasoning processes to identify teleological biases

Similarly, the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model emphasizes cognitive skills that counter teleological reasoning, including hypothesis evaluation, knowledge application, and information processing [18].

Research Translation and Future Directions

Future research should:

- Develop standardized instruments for measuring teleological reasoning in clinical populations

- Establish causal relationships between teleological reasoning reduction and patient safety outcomes

- Investigate domain-specific manifestations of teleological reasoning across medical specialties

- Explore technological interventions (e.g., AI-based clinical decision support) to counter teleological biases

- Examine cultural and individual differences in teleological reasoning susceptibility

The conceptualization of teleological reasoning as an epistemological obstacle rather than a simple misconception suggests the need for educational approaches focused on metacognitive regulation rather than elimination [6]. This aligns with modern theories of clinical reasoning as situated, social, and contextual [16], requiring nuanced interventions that acknowledge the complexity of clinical practice while addressing specific cognitive vulnerabilities.

Teleological thinking, the intuitive tendency to explain phenomena by their purpose or end goal rather than their antecedent causes, represents a significant conceptual barrier in science education and research. In the context of evolution, students frequently explain adaptation as a goal-directed process, invoking purpose, an external designer, or the internal needs of organisms as causal factors [21]. This "teleological bias" persists into adulthood and professional life, potentially affecting scientific reasoning in complex fields like drug development, where understanding emergent, non-directed processes is crucial. This document explores how specific pedagogical frameworks—constructivism and inquiry-based learning—can be strategically deployed to counteract these deeply ingrained reasoning patterns.

The challenge is particularly pronounced because teleological explanations often serve as a natural starting point for hypothesis generation, making them seductively intuitive [22]. However, when this initial teleological stance is not rigorously followed by testing against the null hypothesis, it risks supplanting scientific skepticism with conviction-driven narratives. Constructivist and inquiry-based approaches directly target this vulnerability by restructuring the learning process to move students from intuitive, purpose-driven explanations toward evidence-based, causal reasoning.

Theoretical Foundations

Constructivist Learning Theory

Constructivism posits that learners actively construct knowledge through their experiences and interactions, rather than passively receiving information [23]. This theory emphasizes that new learning is contingent on the learner's prior knowledge, the learning context, and the instructional guidance provided [24]. In a constructivist classroom, the teacher acts as a facilitator who guides students to become active participants, helping them make meaningful connections between what they already know and new knowledge [25].

From a social constructivist perspective, learning is inherently a social activity. Lev Vygotsky argued that all cognitive functions originate as products of social interactions [25]. This is encapsulated in his concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which defines the distance between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with expert guidance. Learning occurs when students are integrated into a "community of inquiry," where knowledge is built collaboratively through discourse and shared problem-solving [25].

Inquiry-Based Learning

Inquiry-based learning is a student-centered pedagogical approach where learning is driven by a process of questioning, investigation, and discovery. Rather than absorbing information passively, students pose questions, gather and analyze data, and draw evidence-based conclusions [26]. This process is iterative, encouraging students to continually refine their ideas as they gather new information.

The Guided Inquiry Design (GID) is a structured model that supports this process, framing learning around a research-based cycle that promotes the development of essential research and critical-thinking skills [26]. This approach stands in stark contrast to traditional, teacher-led methods that focus on content delivery and rote memorization, which often result in only surface-level understanding [26].

The Teleological Challenge

Teleological explanations in biology often involve attributing evolutionary changes to the needs of organisms or the intentions of a designer, thereby misrepresenting the blind, stochastic process of natural selection [21]. This constitutes a "widespread cognitive construal" or an "informal, intuitive way of thinking about the world" [21]. While this mode of thinking is a natural starting point, it becomes an obstacle if it is not developed into a more scientific, causal framework.

Mechanisms of Counteraction: How the Frameworks Address Teleology

The following table summarizes the core mechanisms through which constructivism and inquiry-based learning target and dismantle teleological reasoning.

Table 1: Mechanisms for Counteracting Teleological Thinking

| Pedagogical Framework | Core Mechanism | Impact on Teleological Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| Constructivism | Knowledge actively built by learner [23] | Challenges passive acceptance of intuitive, teleological narratives |

| Learning through social collaboration [25] | Exposes personal teleological ideas to peer critique and alternative viewpoints | |

| Teacher as facilitator (not information source) [25] | Shifts authority from the teacher's "correct answer" to evidence-based reasoning | |

| Inquiry-Based Learning | Learning starts with a question, not an answer [26] | Disrupts the closure provided by a simplistic teleological "explanation" |

| Emphasis on process of investigation [26] | Replaces a focus on the "why" of purpose with the "how" of mechanism and cause | |

| Iterative refinement of ideas [26] | Encourages skepticism of initial (often teleological) hypotheses through testing |

These frameworks do not simply teach what to think about evolution or complex systems; they teach how to think scientifically. They create a learning environment where teleological ideas are naturally surfaced, tested against evidence, and recognized as insufficient, thereby creating the cognitive space for a more robust, scientific understanding to be constructed.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deconstructing Teleology through Guided Inquiry

This protocol is designed for a professional development workshop for researchers and scientists.

4.1.1 Objective: To explicitly identify teleological statements in scientific discourse and redesign them into evidence-based, causal explanations through a guided inquiry process.

4.1.2 Materials:

- Triggering Resource: A short video or case study describing a recent biological phenomenon (e.g., antibiotic resistance, a novel protein function).

- Data Collection Tools: Access to scientific databases (e.g., PubMed, Scopus) and data visualization software.

- Collaboration Platform: A digital collaboration tool like Trello to organize the inquiry process, manage tasks, and document group findings [25].

- Color-Coded Graphic Organizers: Templates for organizing information, using a consistent color scheme (e.g., pink for key vocabulary, yellow for central hypotheses, green for supporting evidence) to structure and differentiate concepts [27].

4.1.3 Procedure:

- Triggering Event (15 min): Present the triggering resource. Participants individually write a brief, initial explanation for the phenomenon.

- Exploration & Identification (30 min):

- In small groups, participants share their initial explanations.

- Using a color-coded worksheet, the group analyzes these statements, highlighting potential teleological language (e.g., "The bacteria wanted to become resistant," "The protein's purpose is to...").

- The group formulates a central, non-teleological research question.

- Investigation (60 min):

- Groups use scientific databases to gather evidence related to their question, focusing on mechanistic data (e.g., genetic mutations, structural changes, selective pressures).

- Findings are logged and organized in a shared Trello board, with columns for "Hypotheses," "Gathered Evidence," "Conflicting Data," and "Revised Explanations."

- Integration & Resolution (45 min):

- Groups synthesize their evidence to construct a causal explanation for the phenomenon, using a color-coded graphic organizer to visually map the relationship between mutation, selection, and the observed outcome.

- Each group presents their findings, explicitly stating how their final explanation differs from their initial teleological one.

4.1.4 Evaluation:

- Compare participants' pre- and post-activity explanations using a rubric that scores for the presence of teleological language and the coherence of the causal mechanism.

- Collect self-reported data on participants' awareness of teleological bias in their own thinking.

Protocol 2: A Constructivist Community of Inquiry for Experimental Design

This protocol outlines a methodology for a research team to critique and improve a proposed experimental plan.

4.2.1 Objective: To leverage social constructivism and a structured Community of Inquiry (CoI) to identify and eliminate teleological assumptions in the design of a drug development experiment.

4.2.2 Materials:

- Draft Experimental Protocol: A one-page description of a proposed experiment, intentionally seeded with a subtle teleological assumption (e.g., framing a drug's effect as its "intended purpose" rather than a testable hypothesis).

- CoI Framework Guide: A handout outlining the three presences: Social (building a safe, collaborative environment), Cognitive (the critical thinking process), and Teaching (facilitation to achieve learning outcomes) [25].

4.2.3 Procedure:

- Establishing Social Presence (10 min): The facilitator leads a round-table introduction where each member states their expertise and one potential blind spot they have when reviewing experimental designs.

- Cognitive Presence - Triggering (20 min): The draft protocol is distributed. Participants silently review it, annotating any statements that seem based on assumption rather than evidence.

- Cognitive Presence - Exploration & Integration (50 min):

- The facilitator guides a discussion where participants present their annotations. The goal is to collaboratively articulate the underlying teleological assumption.

- The group then works together to reframe the experiment's central hypothesis into a falsifiable null hypothesis, ensuring the design is capable of rejecting it [22].

- Teaching Presence & Resolution (40 min): The facilitator ensures the conversation remains focused on the experimental logic and does not become personal. The group collaboratively produces a revised version of the experimental protocol, explicitly stating the null hypothesis and the criteria for its rejection.

4.2.4 Evaluation:

- The quality of the final experimental protocol is assessed by an independent senior scientist using a standardized checklist for methodological rigor.

- Participants are surveyed on their perception of the CoI process's effectiveness in uncovering hidden assumptions.

Visualization of Conceptual Relationships

The following diagram models the logical workflow through which constructivist and inquiry-based pedagogies intervene to disrupt teleological thinking and foster scientific reasoning.

The following table details essential "research reagents" for implementing the described protocols and integrating these pedagogical strategies into a scientific research environment.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Implementing Anti-Teleological Pedagogies

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Guided Inquiry Design (GID) Framework | Provides a flexible, research-based structure for designing inquiry learning cycles. | Used in Protocol 1 to scaffold the process from initial question to resolved explanation, ensuring a move away from teleological intuition [26]. |

| Community of Inquiry (CoI) Model | Defines the three presences (Social, Cognitive, Teaching) required to create a critical, collaborative learning community. | Used in Protocol 2 to structure group interactions, ensuring a safe environment for critiquing ideas and a focused path to conceptual resolution [25]. |

| Digital Collaboration Platforms (e.g., Trello) | Web-based tools that organize projects into boards, making workflow and responsibilities visible to all group members. | Manages the inquiry process in Protocol 1; facilitates task management and documentation in collaborative research teams [25]. |

| Color-Coding Strategy | A cognitive strategy that uses consistent color to distinguish between concepts, improving recall, retention, and organization of information. | Applied in graphic organizers in Protocol 1 to help researchers visually separate assumptions from evidence and map complex causal relationships [27]. |

| Null Hypothesis Formulation | The cornerstone of scientific testing, positing no effect or relationship until evidence proves otherwise. | The central goal of Protocol 2, acting as the direct antidote to untested, teleological assumptions by forcing empirical rigor [22]. |

Evidence-Based Pedagogies to Foster Non-Teleological Reasoning

Implementing Problem-Based Learning (PBL) with Real-World Drug Cases

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) represents a paradigm shift from traditional, lecture-based teaching to a student-centered pedagogy that uses real-world problems to drive the acquisition of knowledge and critical thinking skills [28]. In the context of drug development education, this method proves particularly valuable for challenging teleological thinking—the cognitive bias toward ascribing purpose or predetermined outcomes to natural phenomena without rigorous empirical validation. The implementation of PBL with authentic drug cases forces students to navigate the inherent uncertainties and complex, non-linear pathways that characterize pharmaceutical research and development, thereby countering oversimplified, goal-oriented narratives.

This approach moves students beyond passive reception of established facts and requires them to engage in active investigation, mirroring the authentic scientific process. Through analyzing cases like the rise and fall of Vioxx or the development of new therapeutics, students experience firsthand that drug discovery does not follow a preordained, purposeful path but rather advances through hypothesis generation, rigorous testing, and critical analysis of evidence [29] [22]. The following protocols and application notes provide a structured framework for implementing these educational strategies to foster scientific reasoning and robust critical analysis skills among researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Evidence: Evaluating PBL Effectiveness in Pharmaceutical Education

Empirical studies across diverse educational settings have quantified the impact of PBL on developing crucial competencies. The following tables summarize key findings from research in pharmaceutical and medical education.

Table 1: Comparative Outcomes of PBL vs. Lecture-Based Learning (LBL) in a Pharmacy Student RCT (2021) [30]

| Assessment Metric | PBL Group (n=28) | LBL Group (n=29) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem-Solving Skills (mean score) | 8.43 ± 1.56 | 7.02 ± 1.72 | 0.002 |

| Self-Directed Learning (mean score) | 7.39 ± 1.19 | 6.41 ± 1.28 | 0.004 |

| Communication Skills (mean score) | 8.86 ± 1.47 | 7.68 ± 1.89 | 0.01 |

| Critical Thinking (mean score) | Significantly higher | Baseline | 0.02 |

| Final Exam Grade (mean score) | 79.86 ± 1.38 | 68.10 ± 1.76 | N/A |

Table 2: Improvement in Clinical Thinking Skills of Assistant General Practitioner Trainees (2025) [31]

| Thinking Skill Domain | Post-Course Mean Score (CBL-PBL Group) | Post-Course Mean Score (LBL Group) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Thinking | Notably improved | Less improvement | p < 0.001 |

| Systems Thinking | Notably improved | Less improvement | p < 0.001 |

| Evidence-Based Thinking | Notably improved | Less improvement | p < 0.001 |

| Professional Knowledge Test Score | Substantially increased | Less increase | p < 0.001 |

Table 3: Student Performance in Drug Delivery Courses Before and After PBL Implementation [32]

| Cohort & Teaching Method | Maximum Marks (Drug Delivery Systems 2) | Average Marks (Drug Delivery Systems 1) | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 2014 (Tutorials only) | Lower | Lower | Baseline |

| Cohort 2015 (with PBL) | Significantly higher | Significantly higher (p < 0.05) | Better |

| Cohort 2016 (with PBL) | Significantly higher | Significantly higher (p < 0.05) | Better |

Application Notes: Core Principles for Effective PBL Implementation

Utilizing Real-Life Drug Cases as Pedagogical Tools

Authentic real-life events provide a powerful foundation for developing PBL problems that trigger comprehensive learning objectives difficult to address through clinical scenarios alone [29]. The case of rofecoxib (Vioxx), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug voluntarily withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns, exemplifies an effective, multi-faceted case study. Such a case can introduce students to the complete drug lifecycle—from preclinical testing and clinical trials to post-marketing surveillance and drug withdrawal—while integrating critical issues of professionalism, ethics, patient safety, and critical appraisal of literature [29]. This reality-based approach disrupts teleological assumptions by revealing the complex, often unpredictable interplay of science, business, regulation, and chance that determines a drug's fate.

Structuring Learning to Foster Scientific Reasoning

A well-designed PBL curriculum follows a structured sequence to maximize learning outcomes:

- Problem Activation: Students encounter a trigger, such as a news article about a drug's market withdrawal or data from a clinical trial.

- Self-Directed Learning: In small groups, students identify knowledge gaps, formulate learning objectives, and independently research topics such as drug mechanisms, trial design, and regulatory science [28].

- Knowledge Synthesis: Groups reconvene to share findings, refine their understanding, and collaboratively develop a comprehensive assessment of the case.

- Feedback and Reflection: A concluding session allows students to review the problem, receive feedback, and reflect on the learning process, solidifying the link between evidence and conclusion [29].

The Facilitator's Role in Countering Cognitive Bias

The tutor in a PBL session acts as a facilitator rather than a knowledge transmitter. Effective facilitators guide the discussion, ask probing questions that challenge superficial reasoning, and ensure students consistently support their hypotheses with evidence from the literature [33] [28]. This guidance is crucial for helping students recognize and avoid teleological pitfalls, such as assuming a drug's therapeutic success was inevitable based on its initial mechanism of action, while ignoring contradictory evidence or unforeseen adverse effects that emerged during its development.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a PBL Module on Drug Lifecycle Analysis

Protocol for a Multi-Session PBL Module Using the Vioxx Case Study

Objective: To enable students to comprehensively analyze the lifecycle of a pharmaceutical drug, understand the principles of drug safety, and recognize the non-teleological nature of drug development. Primary Case: Rofecoxib (Vioxx) [29]. Group Size: 8-10 students plus one faculty facilitator. Duration: Typically one week, comprising two 2-3 hour sessions with self-directed learning in between.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Session 1: Case Trigger and Learning Objective Generation

- The facilitator presents the problem through sequential triggers (e.g., initial press release about Vioxx's approval, subsequent clinical study data, news of its withdrawal) [29].

- Students analyze the triggers, identifying facts, generating hypotheses, and pinpointing knowledge gaps.

- The group collaboratively defines a set of learning objectives. Example objectives derived from the Vioxx case include:

- Explain the COX-2 selective inhibition mechanism and its theoretical advantages.

- Describe the phases and design of clinical trials for new drugs.

- Define the role and limitations of post-marketing surveillance.

- Analyze the ethical responsibilities of pharmaceutical companies, regulators, and prescribers.

- Critically appraise a clinical study reporting cardiovascular risks.

Self-Directed Learning Phase

- Students independently research the learning objectives using scientific databases, regulatory guidelines, and medical literature.

- The facilitator is available for guidance on resource selection and research strategies.

Session 2: Knowledge Application and Synthesis

- Students reconvene to share and discuss their findings.

- The group works together to build a comprehensive picture of the case, explaining the scientific, regulatory, and ethical dimensions.

- The facilitator challenges conclusions that lack evidence, pushing students to defend their reasoning with data.

Assessment and Feedback

Integrated CBL-PBL Protocol for Clinical Thinking

For advanced trainees, such as Assistant General Practitioners, an integrated Case-Based Learning (CBL) and PBL approach has proven effective for enhancing clinical thinking [31].

Protocol:

- Preparation: Provide trainees with diagnostic guidelines, relevant academic papers, and clinical procedure videos.

- Simulated Encounter: Begin with a simulated patient encounter to identify key clinical issues.

- Guided Discussion: Facilitate in-depth group discussions where trainees analyze the case, pose questions, and develop evidence-based care plans.

- Synthesis and Review: A group representative summarizes findings, followed by an instructor-led review that provides expert insight and addresses challenges [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for PBL in Drug Development

This toolkit comprises key materials and resources essential for constructing and implementing effective PBL sessions focused on real-world drug cases.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Drug-Based PBL Modules

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in PBL Context | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Real Drug Case Archives | Serves as the foundational trigger problem for PBL sessions. | The Vioxx case provides a complete narrative for discussing drug safety, clinical trials, and ethics [29]. |

| Scientific Databases | Enables self-directed learning; students find primary literature to address learning objectives. | Searching PubMed for clinical trials on COX-2 inhibitors and their associated cardiovascular risks. |

| Clinical Guidelines | Provides a framework for assessing the standard of care and identifying deviations in a case. | Referencing FDA or EMA guidelines on clinical trial design and post-marketing surveillance requirements. |

| Structured Feedback Instrument | A validated questionnaire for collecting quantitative and qualitative feedback on the PBL problem and process. | Using a 5-point Likert scale to assess whether the problem encouraged self-directed learning and critical thinking [29]. |

| Competency Evaluation Scale | Objectively measures the development of target skills such as clinical or critical thinking. | The Clinical Thinking Skills Evaluation Scale (CTSES) assesses critical, systematic, and evidence-based thinking [31]. |

Visualizing the Pedagogical Strategy: From Problem to Competency

The following diagram illustrates the overarching logic and workflow of a PBL intervention, from the initial presentation of a real-world problem to the development of core competencies that counter teleological reasoning.

Utilizing Socratic Questioning to Challenge Assumptions of Purpose

Socratic questioning, a dialectical method developed by the Greek philosopher Socrates, is a structured form of inquiry that uses systematic questioning to explore complex ideas, uncover underlying assumptions, and stimulate critical thinking [34] [35]. Within pedagogical research on teleological thinking—the tendency to explain phenomena in terms of purposes or goals—Socratic questioning serves as a powerful methodological tool to help researchers and scientists identify and challenge implicit purpose-based assumptions that may bias scientific reasoning.

This approach is not about "teaching" in the traditional sense but involves a shared dialogue where the facilitator leads with thought-provoking questions to examine the value systems and beliefs that underpin participants' statements and assumptions [35]. For research professionals, this method provides a framework to critically evaluate their own reasoning patterns and methodological approaches, particularly when confronting complex biological systems or emergent phenomena in drug development where teleological explanations may inadvertently arise.

Theoretical Framework and Core Principles

Historical and Philosophical Foundations

The Socratic Method originates from Western pedagogical traditions dating to Socrates, who engaged in continual probing questioning to explore ethical dilemmas and principles of moral character [35]. This dialectical approach was designed not to impart knowledge but to demonstrate complexity, difficulty, and uncertainty—making it particularly suited for examining sophisticated scientific concepts where teleological assumptions may persist unconsciously.

Key Operational Principles

Socratic questioning in research settings operates on several foundational principles that distinguish it from other pedagogical approaches:

- Collaborative Dialogue: The process involves shared investigation rather than unidirectional instruction, creating a partnership between facilitator and researchers [36].

- Non-Judgmental Exploration: The facilitator maintains genuine curiosity and openness, creating a safe environment for examining deeply held assumptions without defensiveness [36].

- Gradual Progression: Questioning proceeds from broad, open-ended inquiries to more specific probes, allowing participants to explore thoughts at a comfortable pace [36].

- Assumption-Focused: The target of inquiry is not surface-level statements but the underlying belief systems that support them [35].

- Productive Discomfort: The process creates intellectual tension necessary for examining deeply held beliefs, characterized as "productive discomfort" rather than intimidation [35].

Socratic Questioning Typology and Applications

Question Categories for Research Contexts

Socratic questioning can be systematically categorized into distinct types, each serving specific functions in deconstructing teleological assumptions:

Table 1: Socratic Question Typology for Challenging Teleological Assumptions

| Question Type | Primary Function | Research Application Example | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clarifying Questions | Elucidate meaning and define terms | "What exactly do you mean when you describe this biological pathway as 'designed'?" | Clearer operational definitions and identification of ambiguous terminology |

| Probing Assumptions | Uncover implicit premises | "What assumption leads you to conclude this molecular structure exists 'for' a specific function?" | Recognition of unstated presuppositions about purpose in natural systems |

| Probing Evidence | Examine factual support | "What experimental evidence supports this purposeful interpretation versus emergent explanation?" | Differentiation between empirical support and interpretive leaps |

| Alternative Perspectives | Consider viewpoint diversity | "How would researchers from different theoretical frameworks interpret these same results?" | Recognition of multiple plausible explanations without teleological framing |

| Probing Implications | Explore consequence chains | "If this mechanism truly evolved purposefully, what would that imply about its developmental origins?" | Understanding of logical consequences and potential contradictions |

| Meta-Questioning | Examine the questioning process itself | "How does your current research paradigm influence the types of questions you consider valid?" | Awareness of disciplinary constraints on scientific inquiry |

Quantitative Assessment Framework

The effectiveness of Socratic interventions can be measured through structured assessment tools that quantify shifts in reasoning patterns:

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Teleological Reasoning Shifts

| Assessment Dimension | Pre-Intervention Baseline | Post-Intervention Measurement | Measurement Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teleological Statement Frequency | Count of purpose-based explanations in research documentation | Reduction in teleological framing in experimental write-ups | Content analysis coding scheme |

| Assumption Recognition Accuracy | Identification of implicit assumptions in case scenarios (0-100%) | Improved detection of unstated premises in research critiques | Standardized assumption recognition test |

| Explanatory Flexibility | Number of alternative explanations generated for complex phenomena | Increased diversity of mechanistic vs. teleological accounts | Explanatory diversity index |

| Methodological Justification Quality | Rated quality of experimental design rationale (1-5 scale) | Enhanced evidence-based justification for methodological choices | Blind-rated protocol assessment |

| Cognitive Flexibility | Response patterns to paradigm-challenging evidence | Increased adaptation to evidence contradicting initial hypotheses | Cognitive flexibility inventory |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Structured Socratic Dialogue for Research Teams

Purpose: To identify and challenge teleological assumptions in experimental design and interpretation through facilitated group dialogue.

Materials Required:

- Research protocol or paper draft for analysis

- Audio recording equipment for session documentation

- Whiteboard or digital equivalent for mapping assumptions

- Structured questioning guide (Table 1)

Procedure:

- Preparation Phase (15 minutes):

- Select a specific research context (experimental design, data interpretation, or literature evaluation)

- Participants review materials independently, noting potential purpose-based assumptions

- Facilitator identifies key teleological risk areas for targeted questioning

Initial Questioning Phase (20 minutes):

- Facilitator begins with clarifying questions: "What is the central hypothesis?" "How do you define key mechanisms?"

- Progress to assumption-probing questions: "What presuppositions underlie your methodological approach?"

- Document all identified assumptions visually for group reference

Evidence Examination Phase (25 minutes):

- Guide participants to distinguish empirical findings from interpretive frameworks: "Which conclusions are directly data-supported versus inferential?"

- Challenge teleological interpretations: "What evidence specifically indicates purpose versus emergent function?"

- Explore alternative mechanistic explanations for observed phenomena

Implication Analysis Phase (20 minutes):

- Examine consequences of maintained assumptions: "How would your approach change if this assumption proved false?"

- Identify potential methodological biases introduced by teleological framing

- Generate specific strategies for minimizing purpose-based assumptions in future work

Synthesis and Application (10 minutes):

- Participants summarize key insights and specific changes to research approach

- Develop personal action plans for maintaining awareness of teleological reasoning

- Schedule follow-up assessment of implementation success

Validation Measures:

- Pre/post assessment using metrics from Table 2

- Inter-rater reliability scoring of research documentation

- Longitudinal tracking of publication patterns

Protocol 2: Controlled Experimental Evaluation of Socratic Interventions

Objective: To quantitatively measure the efficacy of Socratic questioning in reducing teleological reasoning among research professionals.

Experimental Design:

- Randomized controlled trial with waitlist control group

- Double-blind assessment of outcomes

- Mixed-methods analysis of quantitative and qualitative data

Participant Recruitment:

- Target: 60 research scientists and drug development professionals

- Inclusion: Minimum 2 years research experience, current active research role

- Stratified random assignment by research domain and experience level

Intervention Protocol:

- Experimental Group: Twice-weekly Socratic dialogue sessions (90 minutes) for 6 weeks

- Control Group: Maintains standard research practice during intervention period

- Delayed Intervention: Control group receives intervention after post-test assessment

Assessment Timeline:

- T1: Baseline assessment (pre-intervention)

- T2: Immediate post-intervention assessment

- T3: 3-month follow-up for persistence effects

Primary Outcome Measures:

- Teleological Reasoning Inventory (standardized instrument)

- Research Protocol Quality Assessment (blinded expert review)

- Assumption Recognition Test (experimental measure)

Statistical Analysis Plan:

- Repeated measures ANOVA for group × time interactions

- Effect size calculations using Cohen's d

- Qualitative analysis of session transcripts for thematic patterns

Visualization of Socratic Questioning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow and decision points in applying Socratic questioning to challenge teleological assumptions:

Figure 1: Socratic Questioning Workflow for Teleological Assumptions

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Socratic Intervention Research

| Tool Category | Specific Instrument | Primary Application | Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Tools | Teleological Reasoning Inventory (TRI) | Baseline assessment and outcome measurement | Established reliability (α = 0.87) in research populations |

| Dialogue Protocols | Structured Socratic Dialogue Guide | Standardized facilitation of questioning sessions | Pilot-tested for facilitator consistency |

| Coding Frameworks | Teleological Language Coding Scheme | Quantitative content analysis of research documents | Inter-coder reliability κ = 0.79 achieved |

| Analysis Software | Qualitative Data Analysis Suite | Transcript coding and thematic analysis | Supports mixed-methods research design |

| Control Materials | Active Control Workshop Materials | Control for non-specific intervention effects | Matched for time and engagement demands |

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Facilitation Competencies

Effective implementation requires facilitators to develop specific competencies:

- Question Formulation Precision: Crafting questions that target assumptions without triggering defensiveness requires careful linguistic precision and contextual awareness [36].

- Temporal Pacing Management: Balancing productive discomfort with psychological safety necessitates skilled pacing of challenging questions [35].

- Metacognitive Modeling: Facilitators must explicitly model the examination of their own assumptions to demonstrate the process authentically.

- Domain Expertise Integration: While process expertise is crucial, sufficient scientific domain knowledge ensures relevant and meaningful questioning pathways.

Adaptation for Research Contexts

Successful application in scientific settings requires contextual adaptations:

- Evidence-Based Orientation: Emphasize the distinction between empirical evidence and interpretive frameworks throughout dialogues.

- Methodological Translation: Connect insights directly to concrete changes in research design, data interpretation, and communication practices.

- Collaborative Culture Alignment: Frame the process as enhancing scientific rigor rather than identifying individual deficiencies.

- Time-Efficient Implementation: Develop streamlined protocols compatible with research workflow constraints without sacrificing depth.

Socratic questioning provides a systematic methodology for identifying and challenging teleological assumptions in scientific research, particularly within drug development and biological sciences. The structured protocols and assessment frameworks presented enable rigorous implementation and evaluation of this pedagogical approach.

Future research should explore optimal dosing of interventions, individual difference factors affecting responsiveness, domain-specific adaptations, and technological enhancements for scaling implementation. Longitudinal studies examining the persistence of cognitive changes and their impact on research innovation outcomes will further establish the value of this approach for advancing scientific practice.

Designing Constructivist Learning Environments for Active Knowledge Building