Decoding Allostery: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Are Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

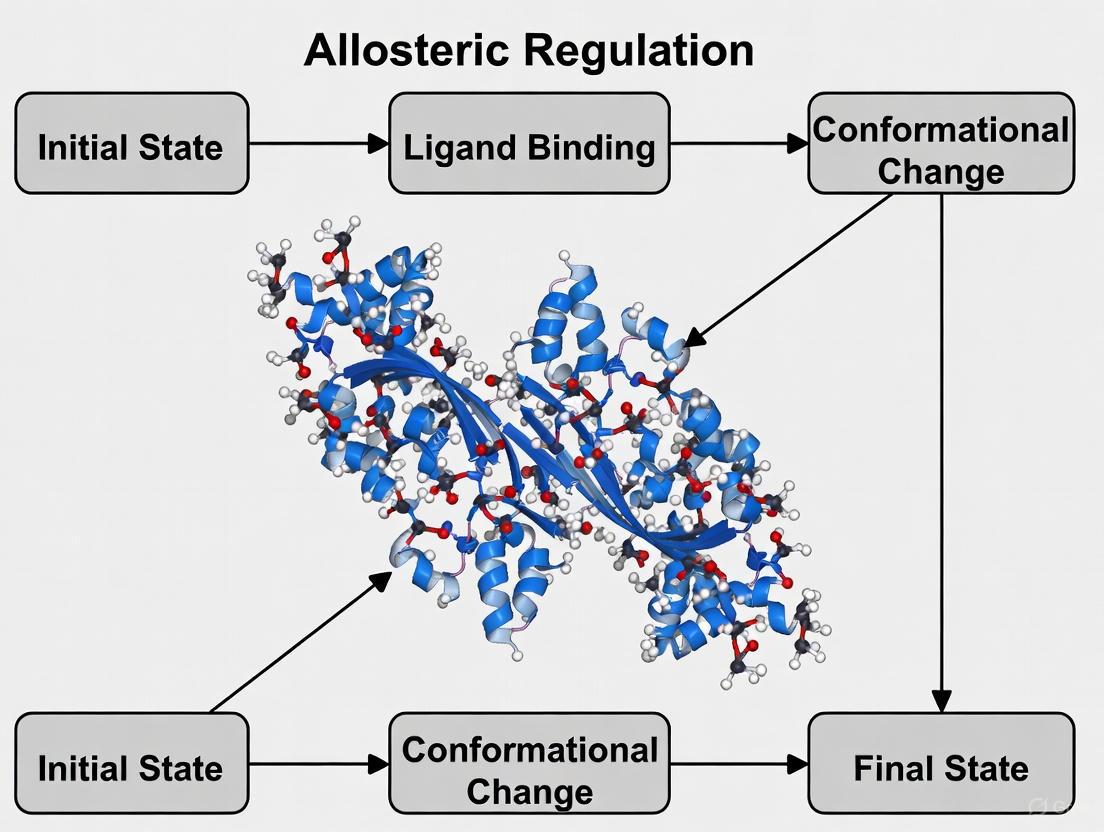

Allosteric regulation, the process of controlling protein function through binding at distal sites, offers a promising avenue for developing highly selective therapeutics.

Decoding Allostery: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Are Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

Abstract

Allosteric regulation, the process of controlling protein function through binding at distal sites, offers a promising avenue for developing highly selective therapeutics. This article explores the transformative role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in elucidating the complex mechanisms of allostery. We detail foundational concepts, advanced computational methodologies—including enhanced sampling and machine learning integration—and their application in identifying cryptic allosteric sites. The content further addresses key challenges in the field, strategies for computational and experimental validation, and provides a forward-looking perspective on how these integrative approaches are paving the way for a new generation of allosteric drugs targeting previously undruggable proteins, with a focus on practical insights for researchers and drug development professionals.

Understanding Allostery: The Foundational Principles and the Critical Role of Dynamics

Allosteric regulation represents a fundamental mechanism of biological control, enabling proteins to communicate and regulate their activity over long molecular distances. Often referred to as the "second secret of life," allostery allows effector molecules to bind at sites distinct from the active site, modulating protein function through conformational changes or alterations in protein dynamics [1] [2]. This regulatory mechanism provides a robust molecular tool for cellular communication, serving critical roles in signal transduction, catalysis, and gene regulation [1]. The conceptual framework of allostery has evolved significantly from early rigid structural models to modern dynamic paradigms that recognize the intrinsic flexibility and conformational ensembles of proteins. This evolution has been driven by advances in structural biology, computational methodologies, and theoretical frameworks, positioning allosteric regulation as a central focus in drug discovery and protein engineering [3] [4]. The growing therapeutic importance of allosteric targeting, particularly for previously "undruggable" targets, underscores the need for a comprehensive understanding of both historical models and contemporary dynamic approaches to allosteric regulation.

Historical Foundations: Classical Allosteric Models

The foundational models of allosteric regulation emerged in the 1960s and established conceptual frameworks that continue to influence the field. These models provided mechanistic explanations for how proteins could transmit binding information across long distances.

Concerted Model (MWC Model)

Proposed by Monod, Wyman, and Changeux, the concerted model postulates that protein subunits exist in a equilibrium between tense (T) and relaxed (R) states, with all subunits necessarily existing in the same conformation [5]. In this symmetric model, the equilibrium between these states can be shifted through the binding of effector molecules to regulatory sites distinct from active sites. The MWC model effectively explains positive cooperativity, as exemplified by oxygen binding to hemoglobin, where ligand binding to one subunit increases the affinity of adjacent subunits [5].

Sequential Model (KNF Model)

Described by Koshland, Nemethy, and Filmer, the sequential model offers an alternative perspective where subunits undergo induced fit conformational changes independently [5]. Unlike the concerted model, the sequential model does not require all subunits to adopt the same conformation simultaneously, allowing for mixed conformational states within the same protein complex. This model accommodates both positive and negative cooperativity through a more flexible mechanism where substrate binding at one subunit only slightly alters the structure of adjacent subunits to make their binding sites more receptive to substrate [5].

Morpheein Model

The morpheein model represents a dissociative concerted model where homo-oligomeric proteins exist as an ensemble of physiologically significant and functionally different alternate quaternary assemblies [5]. Transitions between these assemblies involve oligomer dissociation, conformational change in the dissociated state, and reassembly to a different oligomer. The disassembly step differentiates this model from classic MWC and KNF models, with porphobilinogen synthase serving as the prototype morpheein [5].

Table 1: Classical Models of Allosteric Regulation

| Model | Key Postulates | Mechanistic Insights | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concerted (MWC) | Proteins exist in T/R state equilibrium; all subunits change conformation simultaneously | Explains positive cooperativity; symmetry conservation | Hemoglobin oxygen binding kinetics |

| Sequential (KNF) | Induced fit mechanism; independent subunit conformation changes | Accounts for negative cooperativity; mixed conformational states | Aspartate transcarbamoylase regulation |

| Morpheein | Dissociative model requiring oligomer disassembly/reassembly | Alternative pathway for allosteric transitions | Porphobilinogen synthase quaternary structure changes |

The Modern Dynamic Paradigm

The contemporary understanding of allostery has expanded beyond rigid structural models to embrace the dynamic nature of proteins and the significance of conformational ensembles.

Ensemble Allostery Model

The ensemble model conceptualizes proteins as existing in a statistical ensemble of conformational states, with allosteric regulation occurring through population shifts within this ensemble [1] [2]. This framework acknowledges that allosteric signaling can occur without major structural changes through alterations in the protein's dynamic energy landscape. The model emphasizes that statistical ensembles of preexisting conformational states and communication pathways are intrinsic to a given protein system, allowing for modulation and redistribution induced by external perturbations, ligand binding, and mutations [1].

Dynamic Allostery

Dynamic allostery represents a significant departure from classical models by demonstrating that allosteric regulation can occur through alterations in thermal fluctuations and dynamics without major conformational shifts [2]. First introduced by Cooper and Dryden, this mechanism suggests that ligand binding alters the local effective elastic modulus of the protein, modulating the amplitude of thermal fluctuations rather than inducing large-scale conformational changes [2]. Experimental evidence from NMR spectroscopy has revealed that changes in residue-level fluctuations can drive allosteric effects, demonstrating that allostery can emerge from shifts in dynamic properties rather than distinct conformational changes [2].

Allosteric Communication Networks

Modern paradigms recognize allosteric regulation as a global property of protein systems that can be described by residue interaction networks, where effector binding initiates cascades of coupled fluctuations that propagate through the network and elicit long-range functional responses [1]. Graph-based network approaches map dynamic fluctuations onto graphs with nodes representing residues and edges representing dynamic properties, identifying key functional centers and allosteric communication pathways [1] [3]. These approaches have revealed that rapid signal transmission through small-world networks may be a universal signature encoded in protein families [1].

Figure 1: The conceptual transition from classical to modern paradigms in allosteric regulation, highlighting the key models and mechanisms within each framework.

Quantitative Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Modern allosteric research employs sophisticated computational and experimental approaches to characterize allosteric mechanisms across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable tools for probing biomolecular conformational dynamics, offering atomic-level insights into transient structural states and allosteric communication pathways [3]. These simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for systems comprising thousands to millions of atoms across timescales ranging from nanoseconds to milliseconds, effectively capturing thermal fluctuations and collective motions underlying functional protein dynamics [3].

Protocol 4.1.1: MD Simulation for Allosteric Site Detection

System Preparation: Obtain protein structure from PDB database, add missing residues or loops if necessary, solvate in explicit water box, add ions to neutralize system charge [6].

Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent minimization (5,000 steps) followed by conjugate gradient minimization (5,000 steps) to remove steric clashes.

Equilibration: Conduct gradual heating from 0K to 300K over 100ps with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (force constant: 1000 kJ/mol/nm²), followed by 1ns NPT equilibration with reduced position restraints (force constant: 400 kJ/mol/nm²).

Production Simulation: Run unrestrained MD simulation for timescales appropriate to system size and research question (typically 100ns-1μs), saving coordinates every 10-100ps for analysis [6].

Trajectory Analysis: Calculate root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration, and inter-residue distances to identify conformational changes and flexible regions [6].

Allosteric Site Detection: Identify transient pockets using pocket detection algorithms (e.g., MDpocket, POVME), correlate pocket opening with functional motions, and validate through mutational analysis [3].

Large-scale MD datasets, such as the GPCRmd database encompassing over 190 GPCR structures with cumulative simulation times exceeding half a millisecond, have revealed extensive local "breathing motions" of receptors on nano- to microsecond timescales, providing access to numerous previously unexplored conformational states [6]. These simulations have demonstrated that allosteric sites frequently adopt partially or completely closed states in the absence of molecular modulators, highlighting the importance of dynamics in allosteric site accessibility [6].

Network-Based Allostery Analysis

Network-based approaches conceptualize proteins as graphs where residues represent nodes and their interactions represent edges, enabling quantitative analysis of allosteric communication pathways [1] [3].

Protocol 4.2.1: Residue Interaction Network Construction and Analysis

Network Construction: Generate correlation matrix from MD trajectories using linear mutual information (LMI) or generalized correlation methods, define nodes as Cα atoms or individual residues, establish edges based on correlation thresholds or contact maps [1].

Network Metric Calculation: Compute betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and edge betweenness to identify highly connected residues and potential allosteric hubs [1].

Community Detection: Apply Girvan-Newman or Louvain community detection algorithms to identify clusters of strongly correlated residues that may represent functional modules [3].

Pathway Analysis: Identify optimal allosteric communication pathways using shortest path algorithms (e.g., Dijkstra's algorithm) with edge weights inversely related to correlation strength [1].

Dynamic Coupling Analysis: Calculate Dynamic Flexibility Index (DFI) to quantify residue resilience to perturbations and Dynamic Coupling Index (DCI) to measure inter-residue dynamic coupling, identifying Dynamic Allosteric Residue Couples (DARC sites) [2].

Tools such as MDPath employ normalized mutual information (NMI) analysis of MD simulations to identify allosteric communication paths, demonstrating applications across diverse systems including GPCRs and kinases [7].

Markov State Modeling

Markov State Models (MSMs) provide a powerful framework for reducing the complexity of MD simulations by discretizing conformational space into states and modeling transitions between them as a Markov process [1] [8].

Protocol 4.3.1: Markov State Model Construction

Feature Selection: Choose relevant structural features (e.g., dihedral angles, contact maps, inter-residue distances) that capture functional motions.

Dimensionality Reduction: Apply time-lagged independent component analysis (tICA) or principal component analysis (PCA) to identify slow collective variables.

Clustering: Use k-means clustering or density-based spatial clustering to discretize conformational space into microstates.

Model Construction: Build transition probability matrix between microstates at specified lag time, validating Markov property by testing Chapman-Kolmogorov equality.

Coarse-Graining: Perform Perron cluster cluster analysis (PCCA+) to group microstates into macrostates representing functionally relevant conformations.

Path Analysis: Identify transition paths between functional states and calculate transition rates and fluxes [8].

MSMs have been successfully applied to study allosteric regulation in systems such as KRAS-effector interactions, revealing how oncogenic mutations stabilize active states and enhance binding through modulation of switch region flexibility [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics in Modern Allosteric Research

| Methodology | Key Metrics | Biological Interpretation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics | RMSD, RMSF, dihedral angles, contact maps | Conformational stability, flexibility, interaction persistence | GPCR breathing motions, cryptic pocket opening [6] |

| Network Analysis | Betweenness centrality, shortest paths, community structure | Residue importance in communication, signal transduction pathways | Allosteric hub identification in kinases [1] [3] |

| Markov Modeling | Transition probabilities, implied timescales, state populations | Kinetic rates between conformations, thermodynamic stability of states | KRAS activation mechanism analysis [8] |

| Dynamic Analysis | DFI, DCI, vibrational density of states | Resilience to perturbations, allosteric coupling strength, collective motions | Evolutionary analysis of β-lactamases [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Contemporary allosteric research employs diverse reagents and computational tools that enable the characterization and manipulation of allosteric systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Allosteric Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Biomolecular dynamics simulation, conformational sampling | All-atom simulation of protein dynamics [3] [6] |

| Allosteric Site Prediction | MDPath, AlloScore, SPACER | Identification of regulatory pockets from structural data | Cryptic pocket detection in GPCRs and kinases [7] [3] |

| Network Analysis Tools | NetworkView, Carma, MD-TASK | Residue interaction network construction and analysis | Pathway identification in allosteric proteins [1] |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Metadynamics, REST2, Gaussian Accelerated MD | Accelerated exploration of conformational space | Rare event sampling, binding pocket discovery [3] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | AlphaFold2, ESM-2, DeepAllostery | Structure prediction, sequence analysis, site classification | Allosteric site prediction from sequence and structure [3] |

| Experimental Validation | NMR spectroscopy, HDX-MS, Cryo-EM | Conformational dynamics measurement, structural validation | Experimental verification of predicted allosteric mechanisms [1] [2] |

Allosteric Signaling Pathways: Visualization and Mechanisms

Allosteric communication within proteins follows specific pathways that can be mapped and quantified using computational approaches.

Figure 2: Allosteric signaling pathways illustrating both conformational (black) and dynamic (red) mechanisms of allosteric communication, highlighting the role of network hubs and distally coupled residues.

Application Notes: Case Studies in Allosteric Investigation

GPCR Allosteric Regulation

G protein-coupled receptors represent a paradigm for allosteric regulation in membrane proteins. Large-scale MD simulations of GPCRs have revealed that these receptors exhibit significant "breathing motions" on nanosecond to microsecond timescales, with spontaneous sampling of intermediate and even active-like states even in the absence of agonists [6]. These studies have demonstrated that antagonists, inverse agonists, and negative allosteric modulators reduce conformational sampling, suggesting that perturbation of conformational dynamics through inactive state stabilization represents a general molecular mechanism across receptor subtypes [6]. Lipid insertions into GPCR structures have been identified as valuable markers for membrane-exposed allosteric pockets and lateral entrance gates for specific ligand types [6].

KRAS Oncoprotein Allostery

The KRAS oncoprotein represents an important case study in allosteric regulation, with oncogenic mutations (G12V, G13D, Q61R) stabilizing active states and enhancing effector binding through differential modulation of switch region flexibility [8]. Integrated approaches combining MD simulations, mutational scanning, binding free energy calculations, and dynamic network modeling have elucidated how these mutations modulate allosteric landscapes. The G12V mutation rigidifies both switch I and switch II regions, locking KRAS in a stable active state, while the Q61R mutation induces a more dynamic conformational landscape [8]. Dynamic network analysis has identified critical allosteric centers and a conserved allosteric architecture that enables precision modulation of KRAS dynamics in oncogenic contexts [8].

Enzyme Allosteric Modulation

Allosteric regulation of enzymes demonstrates the therapeutic potential of targeting allosteric sites. FDA-approved allosteric drugs targeting enzymes include trametinib (MEK inhibitor), asciminib (BCR-ABL inhibitor), and deucravacitinib (TYK2 inhibitor) [4]. These drugs exemplify the advantages of allosteric modulation, including enhanced selectivity, reduced toxicity, and the ability to fine-tune enzymatic activity without competing with high-affinity endogenous substrates [4]. Studies on systems such as fructosyltransferase have demonstrated allosteric regulation through distal binding events, where interaction with immobilization surfaces (e.g., Fe₃O₄ interfaces) far from catalytic sites nevertheless influences catalytic activity through allosteric mechanisms [9].

The understanding of allosteric regulation has evolved substantially from early structural models to contemporary dynamic paradigms that recognize the importance of conformational ensembles, fluctuation networks, and population shifts. This evolution has been driven by methodological advances in MD simulations, network analysis, and machine learning, enabling increasingly sophisticated characterization of allosteric mechanisms [3]. The integration of computational and experimental approaches provides a powerful framework for advancing allosteric research, with applications in drug discovery, protein engineering, and fundamental biology [1] [4]. Future directions will likely focus on enhancing the predictive power of allosteric models through advanced ML techniques, integrating multi-scale simulations, and expanding the characterization of allosteric systems across biological networks [3]. As these methodologies continue to mature, they promise to unlock new therapeutic opportunities targeting allosteric regulation in diverse disease contexts.

The Thermodynamic and Structural Basis of Allosteric Communication

Allostery, the process by which a biological macromolecule regulates its activity at one site through the binding of an effector molecule at a distant, topographically distinct site, represents a fundamental mechanism of biological control. This phenomenon enables exquisite regulation of critical cellular processes, from metabolic flux to signal transduction. The thermodynamic and structural basis of allosteric communication provides a framework for understanding how proteins transmit signals over long distances and how these signals can be modulated for therapeutic purposes. Historically, allostery was understood through simple models such as the Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) and Koshland-Némethy-Filmer (KNF) models, which described concerted and sequential conformational transitions, respectively. However, recent advances in structural biology and computational modeling have revealed that allosteric regulation involves a complex interplay of conformational equilibria, dynamics, and energetic pathways that transmit information through proteins.

Contemporary research has demonstrated that allostery is an intrinsic property of all dynamic proteins, not just multimeric proteins as initially thought. All protein surfaces represent potential allosteric sites subject to ligand binding or mutations that can introduce structural perturbations elsewhere in the protein [10]. This expanded understanding has significant implications for drug discovery, as allosteric modulators offer advantages in specificity and reduced toxicity compared to orthosteric drugs that target active sites directly [11]. The growing appreciation of allostery as a dynamic phenomenon has been catalyzed by advances in structural techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and computational methods including molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which together provide unprecedented insights into the atomic-scale mechanisms of allosteric regulation.

Structural Mechanisms of Allostery

Conformational Transitions in Allosteric Proteins

The structural basis of allostery involves coordinated transitions between distinct conformational states, typically categorized as active (R-state) and inactive (T-state) conformations. Recent cryo-EM studies of human phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1), a key glycolytic enzyme, have elucidated fundamental differences in allosteric mechanisms between eukaryotic and bacterial systems. While bacterial PFK1 undergoes a classic R-to-T-state transition via a 7-degree rotation between rigid dimers, the human liver isoform (PFKL) exhibits a more complex transition involving a 7-degree rotation between monomers around a different axis not coincident with the protein's symmetry axes [12]. This transition is stabilized by the C-terminus, which acts as an autoinhibitory element, and by ATP binding at multiple sites, including a third site (site 3) between the catalytic and regulatory domains that is not occupied in the R-state [12].

The allosteric transition in PFKL involves local unfolding of an α-helix adjacent to ATP site 3, which disrupts the positions of residues R201 and R292 that normally bind the phosphate of the substrate F6P in the active R-state [12]. This mechanism illustrates how allosteric inhibition functionally disrupts substrate binding without affecting ATP binding in the active site. Similarly, studies on ribonucleotide reductase (RR) have revealed that allosteric regulation can occur through effector-induced oligomerization, where dATP binding promotes the formation of inactive hexamers, while ATP induces active dimers and hexamers [13]. These structural insights demonstrate the diversity of allosteric mechanisms employed by different protein systems.

Allosteric Networks and Communication Pathways

Proteins possess intricate networks of residues that facilitate allosteric communication. These networks enable the transmission of structural perturbations from allosteric sites to functional sites through pathways of spatially connected residues. Research on the response regulator protein CheY, which undergoes allosteric activation upon phosphorylation of D57, has identified specific residues critical for these communication pathways [10]. Computational predictions using tools like Ohm have successfully identified key residues in allosteric networks that correlate well with experimental mutagenesis studies, validating the importance of these pathways for allosteric function [10].

The emerging "allosteric lever" concept provides a physical principle for understanding how these networks function. This hypothesis proposes that structural perturbations at allosteric sites couple localized hard elastic modes with concerted long-range soft-mode relaxation, creating an efficient, directed transmission to distant target sites [14]. This mode-coupling pattern differs from non-allosteric perturbations, which typically couple hard and soft modes uniformly without specific directionality. The allosteric lever mechanism explains how minimal structural distortions can be efficiently transmitted to produce specific changes at distant functional sites, and interestingly, the protein sequence patterns that comprise these transmission channels appear to be evolutionarily conserved [14].

Table 1: Key Structural Features of Allosteric Proteins

| Structural Element | Role in Allostery | Example Protein | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-terminal autoinhibitory segment | Stabilizes T-state conformation | PFKL [12] | Cryo-EM structures of R and T states |

| Multiple nucleotide binding sites | Differential regulation via occupancy | PFKL [12] | Ligand density in cryo-EM maps |

| Oligomerization interfaces | Effector-induced quaternary changes | Ribonucleotide reductase [13] | X-ray structures of hexamers |

| Conserved hydrophobic pockets | Allosteric inhibitor binding | MKP5 [15] | X-ray crystallography with Compound 1 |

| Dynamic loops | Transmit conformational changes | MKP5 [15] | MD simulations and NMR |

Thermodynamic Foundations

Population Shift Model and Energy Landscapes

The thermodynamic basis of allostery is best understood through the population shift model, which posits that proteins exist as ensembles of conformations in equilibrium, with allosteric effectors stabilizing specific subsets of these states. This model represents a significant advancement over earlier induced-fit and lock-and-key mechanisms by incorporating the intrinsic dynamics of proteins into the framework of allosteric regulation. According to this view, allosteric communication occurs through shifts in the conformational equilibrium of a protein, rather than through a simple mechanical transmission of motion [16].

Proteins sample a wide energy landscape with multiple minima corresponding to different conformational states. Allosteric effectors function by altering the relative energies of these minima, thereby changing the population distribution across the conformational ensemble. This thermodynamic model explains how allosteric regulators can both activate and inhibit protein function by stabilizing active or inactive conformations, respectively. For example, in human RR1, ATP binding stabilizes active dimeric and hexameric states, while dATP binding preferentially stabilizes inactive hexamers, providing a elegant mechanism for maintaining balanced dNTP pools [13].

Energetics of Allosteric Communication

The transmission of allosteric signals through proteins involves complex energetic relationships between different regions. Recent research on MKP5, a dual-specificity phosphatase, has provided quantitative insights into how energy is propagated through allosteric networks. Structural studies of MKP5 bound to an allosteric inhibitor (Compound 1) revealed that binding at the allosteric site approximately 8 Å from the catalytic C408 residue induces conformational changes that reduce the volume of the enzymatic site by ~18% [15]. This reduction is accompanied by the formation of new hydrogen bonds between the backbone carbonyl of S446 and the hydroxyl group of S413 in the α3 helix, and the disruption of existing hydrogen bonds between S413 and N448 [15].

These structural changes alter the energy landscape of the catalytic site, reducing its accessibility and affinity for substrates. Molecular dynamics simulations of MKP5 have further elucidated how changes in the allosteric pocket propagate conformational flexibility to reorganize catalytically crucial residues in the active site [15]. The conservation of allosteric residue Y435 among active MKPs underscores the thermodynamic importance of this site for regulating catalytic activity across related enzymes [15].

Computational and Experimental Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable tools for studying allosteric mechanisms at atomic resolution. These simulations approximate atomic motions using Newtonian physics, with forces calculated from equations that account for bonded interactions (chemical bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) [16]. By simulating the jiggling and wiggling of atoms over time, MD can capture the dynamic nature of allosteric processes that are difficult to observe experimentally.

MD simulations have proven particularly valuable for identifying cryptic allosteric sites, enhancing virtual screening methodologies, and directly predicting small-molecule binding energies [16]. For example, accelerated MD (aMD) techniques artificially reduce large energy barriers, allowing proteins to sample conformational states that would be inaccessible within conventional simulation timescales [16]. Specialized hardware like the Anton supercomputer has enabled millisecond-scale simulations, capturing protein folding and drug-binding events that occur on biologically relevant timescales [16].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Allosteric Research

| Method | Principle | Applications | Tools/Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Newtonian simulation of atomic motions | Pathway identification, cryptic site discovery | AMBER, CHARMM, NAMD [16] |

| Elastic Network Models (ENM) | Coarse-grained representation of protein dynamics | Allosteric lever identification, mode analysis [14] | Ohm [10] |

| Perturbation Response Scanning | Measures residue sensitivity to perturbations | Critical residue identification | Ohm [10] |

| Allosteric Communication Networks | Graph theory applied to residue interactions | Pathway analysis, hotspot prediction | AlloViz [17] |

| Markov State Models | Statistical analysis of MD trajectories | Conformational ensemble characterization | - |

Experimental Structure Determination

Experimental approaches for studying allostery have advanced significantly with improvements in cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Cryo-EM has been particularly transformative, as it can capture structures in multiple conformational states without the crystallization constraints that often preferentially select for R-state conformations [12]. This capability was demonstrated in the determination of both R- and T-state structures of PFKL, revealing conformational differences between bacterial and eukaryotic enzymes [12].

NMR spectroscopy provides complementary information about protein dynamics and allosteric pathways on multiple timescales. Studies on MKP5 have combined NMR with crystallography and MD simulations to reveal how allosteric binding propagates conformational flexibility to reorganize catalytically crucial residues [15]. The residue Y435 was found to be essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the allosteric pocket and for interactions with substrate MAPKs, demonstrating the integration of multiple experimental approaches in elucidating allosteric mechanisms [15].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Allosteric Pathways with Ohm

Purpose: To identify allosteric sites, pathways, and critical residues using the Ohm computational platform based solely on protein structure.

Experimental Principles: Ohm implements a perturbation propagation algorithm that predicts allosteric coupling through repeated stochastic simulations of perturbation spread across a network of interacting residues. The frequency with which each residue is affected by perturbations originating from active sites defines its allosteric coupling intensity (ACI), which is used to identify allosteric hotspots [10].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Obtain the tertiary structure of the protein of interest from PDB or homology modeling. Identify and annotate active site residues based on experimental data or catalytic signatures.

- Contact Extraction: Extract atomic contacts from the protein structure. Calculate the number of contacts between each residue pair, normalized by the number of atoms in each residue.

- Probability Matrix Calculation: Compute the perturbation propagation probability matrix Pij using the equation: Pij = Cij / Σk Cik, where Cij represents the normalized contact count between residues i and j.

- Perturbation Simulation: Initiate perturbations from active site residues. For each propagation step, generate a random number between 0-1; if this number < Pij, propagate the perturbation from residue i to j.

- Pathway Identification: Repeat the perturbation process 10^4 times, recording residues through which perturbations pass. Calculate ACI values for all residues.

- Hotspot Clustering: Cluster residues according to their ACI values and 3D coordinates. Each significant cluster represents a predicted allosteric hotspot.

- Validation: Compare predictions with known experimental data where available. For Caspase-1, validate that predicted critical residues (R286, E390) match mutagenesis results [10].

Troubleshooting:

- Low ACI values may indicate insufficient sampling; increase repetition count.

- Overprediction of allosteric sites may require adjustment of clustering parameters.

- Comparison with evolutionary conservation can enhance prediction confidence.

Ohm Allosteric Pathway Mapping Workflow: This diagram illustrates the computational workflow for identifying allosteric pathways using the Ohm platform, from structure input to hotspot prediction.

Protocol 2: Allosteric Analysis with AlloViz

Purpose: To quantitatively determine, analyze, and visualize allosteric communication networks using molecular dynamics simulation data.

Experimental Principles: AlloViz is an open-source Python package that computes protein allosteric communication networks from MD trajectories using various correlation metrics, including mutual information with local non-uniformity correction (LNC) for dihedral angles [17]. The tool integrates multiple network construction methods and facilitates analysis using graph theory metrics.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- MD Trajectory Preparation: Perform molecular dynamics simulations of the protein system of interest. Ensure adequate sampling of conformational space.

- Network Construction: Choose appropriate network construction method based on:

- Motion correlation (Pearson correlation of Cα or Cβ positions)

- Dihedral angle correlation (mutual information of ϕ, ψ, χ1...χ4 angles)

- Contact-based metrics (frequency or strength)

- Interaction energies

- Network Filtering: Apply filters to focus on relevant interactions:

GetContacts_edges: Include only contact pairs identified by GetContactsSpatially_distant: Exclude residue pairs beyond distance thresholdNo_Sequence_Neighbors: Exclude adjacent residues in sequenceGPCR_Interhelix: For GPCRs, retain only inter-helical residue pairs

- Network Analysis: Calculate centrality metrics to identify key residues:

- Betweenness centrality: Number of shortest paths through nodes/edges

- Current-flow betweenness: Random-walk based centrality using electrical current model

- Delta-Network Calculation: Compare allosteric networks between different states (e.g., apo vs. ligand-bound) by subtracting edge weights to identify perturbation-induced changes.

- Visualization: Use AlloViz's graphical interface or Python API to visualize allosteric networks on protein structures.

Troubleshooting:

- High computational demand for large proteins; consider trajectory downsampling.

- Network noise from thermal motion; apply spatial or sequence distance filters.

- Interpretation challenges; use multiple centrality metrics and compare with evolutionary conservation.

Protocol 3: Cryo-EM Analysis of Allosteric States

Purpose: To determine high-resolution structures of allosteric proteins in multiple conformational states using cryo-EM.

Experimental Principles: Cryo-EM enables structure determination of proteins in near-native states without crystallization constraints. Single-particle analysis classifies particles into different conformational states, allowing determination of multiple structures from a single sample [12].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Purify target protein to homogeneity. Optimize buffer conditions and add relevant ligands (substrates, effectors, inhibitors) to stabilize specific states.

- Grid Preparation: Apply 3-4 μL protein sample (0.5-3 mg/mL) to glow-discharged cryo-EM grids. Blot and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane using vitrification device.

- Data Collection: Collect movie stacks on high-end cryo-EM microscope (e.g., Titan Krios) with dose-fractionation at specified defocus range. Target 500-1000 micrographs per dataset.

- Image Processing:

- Motion correction and dose weighting

- CTF estimation

- Automated particle picking

- 2D classification to remove junk particles

- Ab initio reconstruction and 3D classification

- State Separation: Use 3D classification without symmetry or with appropriate symmetry (e.g., C2 for PFKL filaments) to separate conformational states [12].

- High-Resolution Refinement: Refine each state separately using masked local refinement approaches. Apply symmetry if appropriate.

- Model Building and Analysis: Build atomic models into cryo-EM densities. Analyze conformational differences between states, ligand binding sites, and oligomeric interfaces.

Troubleshooting:

- Preferred orientation: Try different grid types or additives.

- Heterogeneity: Increase 3D classification rounds and particle numbers.

- Resolution limitations: Optimize ice thickness, particle concentration, and data collection parameters.

Cryo-EM Workflow for Allosteric States: This diagram outlines the single-particle cryo-EM workflow for determining structures of multiple allosteric states, from sample preparation to model analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Allosteric Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlloViz | Python package for allosteric network analysis from MD data | β-arrestin 1, PTP1B allosteric communication [17] | Integrates multiple network methods; GUI and scripting interfaces |

| Ohm | Web server for allosteric site/pathway prediction from structure | Caspase-1, CheY allosteric hotspot identification [10] | Structure-based; no MD required; perturbation propagation algorithm |

| Compound 1 (Cmpd 1) | MKP5 allosteric inhibitor | MKP5 catalytic regulation studies [15] | Binds ~8Å from catalytic C408; Y435 interaction |

| AMBER/CHARMM/NAMD | MD simulation software with force fields | Protein dynamics, allosteric pathway analysis [16] | Newtonian physics-based; explicit solvent models |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Sample support for cryo-EM | PFKL R/T state structure determination [12] | UltrAuFoil, Quantifoil; various hole sizes |

| GPCRdb | GPCR structure database and tools | GPCR allosteric site identification [17] | Generic residue numbering; inter-helix contact filters |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Allosteric modulation represents a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention, offering advantages in specificity and the potential to overcome drug resistance. Allosteric drugs can achieve high specificity by targeting unique regulatory sites rather than conserved active sites, reducing off-target effects [18] [11]. The FDA has approved several allosteric modulators, underscoring the clinical relevance of this approach.

Recent advances in computational methods have accelerated allosteric drug discovery by enabling the prediction of hidden allosteric sites that can greatly expand the repertoire of available drug targets [11]. Integration of evolutionary, structural, and dynamic features with machine learning models has improved the identification and exploitation of allosteric sites [18]. These computational approaches are complemented by experimental techniques that validate cryptic and functionally relevant pockets across diverse enzyme families [18].

Case studies on proteins such as MKP5 demonstrate the therapeutic potential of allosteric targeting. The identification of Compound 1 as an allosteric MKP5 inhibitor that binds approximately 8 Å from the catalytic site illustrates how allosteric modulation can achieve effective inhibition without competing directly with substrates at the active site [15]. Similarly, the discovery of dATP-induced oligomerization as a regulatory mechanism for ribonucleotide reductase provides insights for developing anticancer agents that target nucleotide metabolism [13].

The thermodynamic and structural basis of allosteric communication represents a complex interplay of conformational dynamics, energetic pathways, and evolutionary constraints. Advances in structural biology, particularly cryo-EM, have revealed unprecedented details of allosteric mechanisms, while computational approaches have provided tools to predict and analyze allosteric networks. The integration of these methods offers a powerful framework for understanding how proteins transmit signals over long distances and how these signals can be modulated for therapeutic purposes.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing more accurate force fields for molecular dynamics simulations, improving methods for predicting allosteric sites from sequence and structure, and designing allosteric modulators with tailored pharmacological properties. The emerging "allosteric lever" concept, which describes a mode-coupling pattern that enables efficient signal transmission, may provide a unifying principle for understanding allosteric mechanisms across diverse protein systems [14]. As these tools and concepts continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly expand our understanding of allosteric regulation and enhance our ability to target allosteric sites for therapeutic benefit.

Proteins are not static entities; they exist as dynamic conformational ensembles—collections of interconverting structures—around a native state [19]. This inherent flexibility is central to allosteric regulation, where an effector binding at one site remotely influences the functional activity at another site [3] [20] [21]. A critical consequence of this dynamism is the existence of cryptic pockets: transient, often hidden binding sites that are not apparent in static, ground-state protein structures but can emerge due to thermal fluctuations and become druggable upon opening [22]. These pockets vastly expand the potentially druggable proteome, offering opportunities to target proteins currently considered "undruggable" because they lack persistent pockets [23] [22].

The discovery of cryptic pockets is transformative for drug discovery. Unlike often-conserved orthosteric sites, cryptic pockets tend to be less conserved across protein families, enabling the development of highly selective modulators with reduced off-target effects [3] [22]. Furthermore, allosteric modulators targeting these sites can fine-tune protein activity—either inhibiting or activating it—rather than completely blocking it, preserving baseline biological signaling [3] [20]. Understanding and identifying these pockets requires a paradigm shift from a static, single-structure view to a dynamic, ensemble-based perspective, which is enabled by advanced computational strategies in molecular dynamics and machine learning [19] [23].

The Computational Toolkit for Studying Conformational Ensembles

Investigating cryptic pockets and conformational ensembles requires a multi-faceted computational approach. The table below summarizes the key methodologies, their underlying principles, and applications in allosteric research.

Table 1: Computational Methodologies for Analyzing Conformational Ensembles and Cryptic Pockets

| Method Category | Key Methods & Algorithms | Primary Function | Application in Cryptic Pocket Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Conventional MD, Accelerated MD (aMD), Steered MD (SMD) | Simulates atomic-level motions and thermodynamic fluctuations of biomolecules over time [20] [21]. | Captures transient pocket opening events and conformational shifts that reveal cryptic sites [22] [15]. |

| Enhanced Sampling | Metadynamics (MetaD), Umbrella Sampling, Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Accelerates exploration of conformational space and free energy landscapes by overcoming energy barriers [20] [21]. | Efficiently identifies rare, high-energy conformational states where cryptic pockets are formed [20]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | PocketMiner (Graph Neural Network), CryptoSite | Predicts locations of cryptic pocket formation directly from single protein structures [22]. | Enables rapid, proteome-scale screening for proteins likely to harbor cryptic pockets [22]. |

| Ensemble Structure Prediction | FiveFold (integrates AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, etc.) | Generates multiple plausible conformations from a single sequence, modeling conformational diversity [23]. | Provides a set of alternative starting structures for dynamics simulations or analysis, capturing intrinsic flexibility [23]. |

| Network & Motion Analysis | Normal Mode Analysis (NMA), Statistical Coupling Analysis (SCA) | Identifies collective motions and allosteric communication pathways within a protein [3] [20]. | Pinpoints residues critical for allostery and regions prone to conformational changes that may host cryptic pockets [3]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and resources that form the core "wet lab" for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function & Utility |

|---|---|---|

| PocketMiner [22] | Graph Neural Network | Predicts residues where cryptic pockets are likely to open from a single static structure, enabling high-throughput target prioritization. |

| FiveFold [23] | Ensemble Prediction Platform | Generates a conformational ensemble by combining five structure prediction algorithms, providing a better starting point for dynamics. |

| AlphaFold2 [3] [23] | Deep Learning Structure Prediction | Provides highly accurate initial protein structures; its outputs are key components of ensemble methods like FiveFold. |

| MDpocket [20] | Analysis Algorithm | Used with MD trajectories to track the evolution of pocket volumes and identify transient binding sites. |

| GPCRmd [3] | MD Database & Platform | A specialized repository for MD simulation data of GPCRs, facilitating data sharing and comparative analysis. |

| PASSer [20] [21] | Prediction Server | An online platform for the prediction of allosteric sites. |

Protocol 1: Predicting Cryptic Pockets with PocketMiner

This protocol details the use of the PocketMiner graph neural network to rapidly identify proteins with a high probability of containing cryptic pockets, using a single static structure as input [22]. This serves as a powerful pre-screening tool before committing to more resource-intensive MD simulations.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key steps in the PocketMiner prediction workflow.

Figure 1: PocketMiner Cryptic Pocket Prediction Workflow.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Input Preparation (Node A)

- Source: Obtain a 3D structure of the protein of interest in its ligand-free (apo) state. Suitable sources include experimental structures from the PDB or high-confidence predicted models from AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold.

- Formatting: Ensure the structure file is in PDB format. Pre-process the file to remove water molecules, ions, and other non-protein heteroatoms that are not relevant to the pocket prediction.

Model Execution (Nodes B & C)

- Featurization: PocketMiner automatically converts the input structure into a graph representation where nodes are amino acid residues and edges represent spatial proximity.

- Prediction: Run the pre-trained PocketMiner model. The model assigns a probability score to each residue, predicting its likelihood of participating in a cryptic pocket opening event within a short (e.g., 40 ns) MD simulation [22].

Output & Analysis (Nodes D & E)

- Visualization: Map the per-residue probability scores onto the protein structure using molecular visualization software like PyMOL or UCSF Chimera. Typically, a continuous surface is colored by the prediction score (e.g., blue for low probability, red for high probability).

- Identification: Identify spatial clusters of residues with high probability scores (e.g., >0.5). The centroid of the largest or highest-scoring cluster indicates the most likely location for a cryptic pocket.

Decision Point (Node F)

- Prioritization: Proteins with strong, high-probability predictions can be prioritized for further investigation via molecular dynamics simulations (Protocol 2) or experimental validation. PocketMiner achieves an ROC-AUC of 0.87 and performs prediction over 1,000-fold faster than simulation-based methods, making it ideal for screening [22].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Pocket Dynamics with Enhanced MD Simulations

Once a target is identified, this protocol uses enhanced sampling Molecular Dynamics to rigorously characterize the conformational ensemble and capture the full process of cryptic pocket opening and closing [20] [21] [15].

Experimental Workflow

The workflow for MD-based characterization of cryptic pockets involves system setup, enhanced sampling, and detailed analysis.

Figure 2: Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Cryptic Pockets.

Step-by-Step Procedure

System Preparation (Nodes A & B)

- Solvation: Place the protein in a simulation box of explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model).

- Ionization: Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

- Minimization & Equilibration: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes. Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) and equilibrate under constant pressure (NPT ensemble) to achieve stable density.

Enhanced Sampling Production Simulation (Node C)

- Technique Selection: Choose an enhanced sampling method based on the system.

- Accelerated MD (aMD): Applies a boost potential to the entire system, enhancing the sampling of rare events without requiring pre-defined collective variables. It is particularly useful for initial, unbiased exploration [20] [21].

- Metadynamics (MetaD): Uses a history-dependent bias potential to push the system away from already-visited states. It is ideal for characterizing the free energy landscape of pocket opening if a reasonable collective variable (CV), such as distance between residue Cα atoms around the pocket, can be defined [20] [21].

- Execution: Run the production simulation for a sufficient length (typically hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds) to observe multiple pocket opening and closing events.

- Technique Selection: Choose an enhanced sampling method based on the system.

Trajectory Analysis (Nodes D, E1, E2, E3)

- Pocket Volume Analysis (E1): Use tools like MDpocket to calculate the volume of potential binding pockets for every frame in the trajectory [20]. This identifies frames where the pocket is open.

- Free Energy Surface (E2): If using MetaD, construct the free energy surface as a function of the CVs. The minima on this surface represent stable conformational states, while the saddle points represent transition states [21].

- Allosteric Communication (E3): Perform correlation analysis (e.g., Dynamic Cross-Correlation) or community analysis on the trajectory to identify networks of residues that move together, potentially revealing allosteric pathways linking the cryptic pocket to the active site [3] [15].

Validation & Output (Node F)

- Structural Clustering: Cluster the simulation frames where the pocket is open to obtain representative structures of the cryptic pocket state.

- Druggability Assessment: Use the representative open structures for virtual screening or druggability prediction to assess the potential for ligand binding.

Case Study: Allosteric Inhibition of MKP5 Phosphatase

Research on the dual-specificity phosphatase MKP5 provides a seminal example of integrating crystallography, MD, and biochemistry to decode an allosteric mechanism [15].

- Experimental Identification: A high-throughput screen identified Compound 1 (Cmpd 1) as an inhibitor. An X-ray co-crystal structure revealed Cmpd 1 binding in a pocket ~8 Å away from the catalytic site, defined as an allosteric site, with residue Y435 as a critical binding mediator [15].

- MD Simulations and Mechanism: MD simulations of both the apo and Cmpd 1-bound states provided the dynamic context missing from static structures. The simulations showed that binding of the allosteric inhibitor introduced structural strain, which propagated through the α4-α5 loop and caused conformational changes in the α3 helix. This reorganization reshaped the catalytic pocket, reducing its volume and compromising enzymatic activity without directly occupying it [15].

- Functional Consequence: This study confirmed that the allosteric site was essential not only for inhibitor binding but also for interactions with its native MAPK substrates. It demonstrated how a perturbation at a distal site can transmit through the protein's conformational ensemble to modulate function at the active site [15].

The study of cryptic pockets and conformational ensembles represents a frontier in structural biology and drug discovery. Moving beyond static structures to a dynamic, ensemble-based view is essential for understanding allosteric regulation and for targeting the vast "undruggable" proteome. As demonstrated, a powerful synergy exists between computational approaches: machine learning models like PocketMiner enable rapid target prioritization, while advanced MD simulations provide atomic-level insight into the dynamics and energetics of pocket opening. The integration of these methods with experimental validation, as in the MKP5 case study, creates a robust framework for discovering and characterizing novel allosteric sites, paving the way for a new generation of selective and effective therapeutics.

Allosteric regulation is a fundamental mechanism in protein regulation, enabling the modulation of protein function from sites distal to the active (orthosteric) site [24]. In contrast to orthosteric drugs that compete with endogenous ligands for the active site, allosteric modulators bind to topographically distinct regulatory sites, inducing conformational changes that fine-tune protein activity [3] [20]. This paradigm is gaining traction as a main mode of action in the realm of antibodies and small molecules, offering a novel pharmacology that enables precise regulation of protein activity [24]. The field is entering a transformative era, driven by advancements in computational biology and artificial intelligence (AI), which hold promise for integrating allosteric site detection with de novo antibody and drug design [24] [3].

This Application Note details the core advantages of allosteric drugs—enhanced specificity, reduced toxicity, and novel mechanisms—and provides established experimental and computational protocols for their discovery and characterization, framed within the context of molecular dynamics simulation research.

Core Advantages of Allosteric Drugs

The therapeutic appeal of allosteric modulators stems from several distinct pharmacological advantages over conventional orthosteric drugs, which are quantified and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative and Qualitative Advantages of Allosteric vs. Orthosteric Drugs

| Parameter | Orthosteric Drugs | Allosteric Drugs | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Selectivity | Low; targets conserved active sites, leading to off-target effects [25]. | High; targets less conserved allosteric sites, enabling selective targeting of individual members in conserved families [25] [26]. | A study on matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) demonstrated precise functional modulation of individual isoforms (MMP-7, -12, -13) via latent allosteric sites [27]. |

| Mechanism of Action | Competitive inhibition or activation; completely blocks or mimics endogenous ligand [26]. | Non-competitive, fine-tuned modulation; can be positive (PAM), negative (NAM), or neutral, preserving physiological signaling dynamics [3] [26]. | SBI-553, an allosteric modulator of NTSR1, acts as a "molecular bumper" and "molecular glue," selectively antagonizing Gq/G11 signaling while permitting or enhancing G12/G13 signaling [28]. |

| Toxicity Profile | Higher risk of on-target and off-target toxicity due to complete pathway blockade and target promiscuity [25]. | Reduced toxicity; minimizes on-target side effects by fine-tuning activity and reduces off-target effects via higher selectivity [25] [26]. | Peripherally restricted cannabinoid receptor (CB1) agonists targeting cryptic allosteric sites show significant promise for chronic pain without central toxicity [3]. |

| Therapeutic Application | Limited to "druggable" targets with well-defined, accessible active sites. | Expands the "druggable genome" to previously "undruggable" targets (e.g., GPCRs, Ras) [24] [29]. | Allosteric antibodies have been successfully discovered against previously antibody-undruggable targets like GPCRs and ligand-gated ion channels [24]. |

| Resistance Management | Susceptible to resistance via active site mutations. | Can overcome resistance; mutations in allosteric sites are less common, and allosteric/orthosteric drug combinations can prevent resistance [25] [26]. | The multiplicity of allosteric sites allows for rescuing therapeutic actions when resistance emerges against orthosteric drugs [27]. |

Novel and Diverse Mechanisms of Action

Beyond simple activation or inhibition, allosteric drugs can execute complex pharmacological actions. A prime example is biased signaling, where a drug stabilizes a receptor conformation that preferentially activates a subset of downstream signaling pathways [28]. For instance, the allosteric modulator SBI-553 binds to the intracellular interface of the neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1), switching its G protein subtype preference and promoting signaling through β-arrestin and specific G proteins (G12/G13) while antagonizing others (Gq/G11) [28]. This allows for the separation of therapeutic effects from side effects.

Furthermore, a new generation of allosteric modulators can induce protein stabilization, destabilization, or degradation [26]. For example, the allosteric modulator GT-02287, in development for GBA-associated Parkinson's disease, prevents the misfolding of the glucocerebrosidase (GCase) enzyme, enabling it to function properly and restore lysosomal health, demonstrating transformative, disease-modifying activity [26].

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanistic concepts of allosteric regulation and signaling bias.

Figure 1: Allosteric Drug Mechanisms. Allosteric drugs bind to a site distinct from the orthosteric site, inducing conformational changes that fine-tune protein function and can lead to biased activation of specific signaling pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Allosteric Drug Discovery

Protocol 1: Characterizing Allosteric Modulation of GPCR Signaling

This protocol outlines the use of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays to characterize the G protein subtype selectivity and biased signaling of allosteric modulators, based on a study of the neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1) [28].

Application: To quantitatively profile the signaling bias of an allosteric modulator across multiple G protein subtypes and β-arrestin.

Materials and Reagents:

- TRUPATH BRET2 Sensors: A suite of plasmids for measuring activation of 14 different Gα proteins [28].

- BRET1-based β-arrestin recruitment assay: To measure recruitment of β-arrestin 1 and 2 to the GPCR [28].

- Cell Line: HEK293T cells.

- Ligands: The allosteric modulator of interest (e.g., SBI-553), the endogenous orthosteric ligand (e.g., Neurotensin, NT), and a control competitive antagonist (e.g., SR142948A).

Procedure:

- Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the plasmid for the target GPCR (e.g., NTSR1) and the appropriate BRET sensor plasmids for specific G proteins or β-arrestin.

- Ligand Treatment:

- Agonism Mode: Treat cells with a concentration range of the allosteric modulator alone to assess its intrinsic agonist activity.

- Allosteric Modulation Mode: Pre-treat cells with a fixed concentration of the allosteric modulator, followed by a concentration range of the orthosteric ligand (e.g., NT).

- BRET Measurement: Measure the BRET signal after ligand addition according to the standard protocol for TRUPATH or β-arrestin recruitment.

- Data Analysis:

- Generate concentration-response curves (CRCs) for each transducer.

- For allosteric modulation experiments, analyze the effect on the orthosteric ligand's CRC: note changes in maximal response (indicating non-competitive antagonism or agonism) and shifts in EC₅₀ (indicating changes in potency) [28].

- Calculate bias factors using operational models to quantify the ligand's preference for specific signaling pathways.

Protocol 2: Computational Workflow for Allosteric Site Prediction

This protocol describes an integrated computational workflow for identifying and validating cryptic allosteric sites using molecular dynamics (MD) and machine learning (ML), a cornerstone of modern allosteric drug discovery [3] [20].

Application: To identify transient, druggable allosteric pockets not visible in static crystal structures.

Materials and Software:

- Initial Structure: A high-resolution structure of the target protein from PDB.

- MD Simulation Software: GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD.

- Enhanced Sampling Tools: Plumed (for metadynamics, umbrella sampling).

- Pocket Detection Tools: MDpocket, Fpocket.

- Machine Learning Platforms: Allosteric site prediction tools like PASSer; AlphaFold2 for structural insights.

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Prepare the protein structure in a solvated lipid bilayer (for membrane proteins) or water box, adding necessary ions.

- Energy minimize and equilibrate the system.

- Enhanced Sampling MD:

- Pocket Detection and Analysis:

- Machine Learning Integration:

- Feed features from the MD simulations (e.g., residue contact maps, dihedral angles, pocket volumes) into ML models to predict the druggability and functional role of identified sites [3].

- Validation: Validate computationally predicted sites through mutagenesis studies and functional assays.

The workflow for this integrated protocol is visualized below.

Figure 2: Computational Allosteric Site Prediction. An integrated workflow combining molecular dynamics, pocket detection, network analysis, and machine learning to identify and characterize cryptic allosteric sites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Allosteric Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| TRUPATH BRET2 Kit | Measures activation of specific Gα proteins in live cells. | Profiling G protein subtype selectivity of GPCR allosteric modulators (e.g., SBI-553 at NTSR1) [28]. |

| Covalent Fragment Libraries | Contains small molecules with reactive warheads (e.g., for Cys) for targeting allosteric cysteines. | Discovery of Covalent-Allosteric Inhibitors (CAIs), as demonstrated for PTP1B targeting Cys121 [29]. |

| SwissSimilarity / SwissBioisosteres | Open-access platforms for virtual screening and lead optimization via molecular similarity and bioisosteric replacement. | Identifying novel allosteric inhibitors of PI5P4K2C lipid kinase from a known lead (DVF) [30]. |

| MD Simulation Suites (GROMACS/AMBER) | Performs all-atom molecular dynamics simulations to study protein dynamics and reveal transient states. | Identifying cryptic allosteric sites in proteins like BCKDK and thrombin [3] [20]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Software (Plumed) | Accelerates the exploration of conformational space in MD simulations. | Using metadynamics to uncover hidden allosteric pockets in mitochondrial Hsp90 (Trap1) [20]. |

| AlphaFold2 | Predicts protein 3D structures with high accuracy, providing models for targets with no experimental structure. | Generating structural models for allosteric site prediction and drug design [3]. |

Allosteric regulation is a fundamental mechanism in molecular biology through which the binding of an effector molecule at a site distal to the active site modulates protein function, enabling dynamic control of metabolic pathways and cellular signaling processes [21]. This phenomenon represents a "second secret of life" and has gained significant attention in drug discovery due to the unique advantages of allosteric modulators, including enhanced specificity, reduced off-target effects, and the potential for synergistic action with orthosteric drugs [21] [3]. However, the inherent complexity of allosteric mechanisms presents substantial challenges for systematic investigation and therapeutic targeting. Proteins are dynamic entities that transition between multiple conformational states, meaning that functionally critical allosteric sites often exist only as transient pockets in specific conformations [3]. These cryptic binding sites frequently escape detection by conventional structural biology methods such as X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which provide primarily static structural snapshots [3]. This application note examines the fundamental limitations of static experimental approaches in capturing these transient states and outlines integrated computational methodologies to bridge this critical gap in allosteric research.

The Experimental Limitation: Static Snapshots of Dynamic Systems

The Fundamental Detection Problem

Traditional structural biology methods face inherent limitations in capturing the dynamic spectrum of protein conformational states. X-ray crystallography typically reveals single, stable conformations that may not represent functionally relevant transient states, while the time-averaging nature of these techniques obscures short-lived intermediate conformations where allosteric sites often form [3]. These transient pockets emerge through dynamic conformational changes and represent temporary binding sites that are crucial for allosteric regulation but remain inaccessible to traditional screening methods designed for stable binding pockets [3].

The challenge is particularly pronounced for intrinsically disordered proteins and regions (IDPs/IDRs), which lack ordered structures under physiological conditions yet play significant roles in allosteric regulation [31]. These systems operate through ensemble allostery models where ligand binding stabilizes specific states and shifts conformational ensembles, a mechanism fundamentally different from the order-order transitions described in classical allosteric models like MWC (Monod-Wyman-Changeux) [31]. Static experimental methods cannot adequately capture the thermodynamic landscape of these disordered systems, limiting our understanding of their allosteric mechanisms.

Table 1: Limitations of Static Experimental Methods in Allosteric Research

| Experimental Method | Key Limitations | Impact on Allosteric Site Detection |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Captures single, stable conformations; may miss flexible regions | Fails to reveal cryptic allosteric sites that form only in transient states |

| Cryo-EM | Provides static snapshots; limited resolution for dynamic regions | Obscures allosteric pathways dependent on coordinated motions |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Can detect dynamics but limited by molecular size and timescale | Challenging to apply to large proteins or very rapid transitions |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance | Measures binding affinity but not structural changes | Cannot identify allosteric mechanisms or communication pathways |

Computational Methodologies: Bridging the Temporal Resolution Gap

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational methodology that addresses the fundamental limitations of static experimental approaches by providing atomic-level temporal resolution of biomolecular motions [21]. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for systems comprising thousands to millions of atoms across timescales from nanoseconds to milliseconds, MD simulations effectively capture the thermal fluctuations and collective motions that underlie functional protein dynamics and allosteric communication pathways [3]. The strength of MD lies in its ability to reveal conformational changes over various timescales, providing dynamic information essential for understanding enzyme allosteric regulation—information often inaccessible through traditional experimental methods [21].

In studying allosteric regulation, MD has proven particularly effective in identifying cryptic allosteric sites. For instance, in research on branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase (BCKDK), static X-ray crystallography failed to reveal certain allosteric sites, whereas MD simulations successfully captured their conformational changes [21]. Similarly, in studies of thrombin, MD simulations analyzed the conformational impact of the antagonist hirugen, uncovering cryptic allosteric sites and delineating underlying dynamic pathways [21]. These applications demonstrate how MD provides critical insights into the dynamic adjustments in key intermolecular interactions that govern allosteric regulation.

Table 2: Enhanced Sampling Techniques for Allosteric Site Discovery

| Computational Method | Fundamental Approach | Application in Allosteric Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metadynamics (MetaD) | Applies bias potential along collective variables to overcome energy barriers | Reveals hidden allosteric sites by exploring conformational transitions |

| Accelerated MD (aMD) | Modifies potential energy surface with boost potential | Captures millisecond-scale events in nanosecond simulations, identifying transient pockets |

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Simulates multiple replicas at different temperatures with periodic exchanges | Explores conformational states separated by high energy barriers |

| Umbrella Sampling | Divides conformational space into windows along reaction coordinates | Calculates free energy landscapes for allosteric site formation |

| Markov State Models (MSMs) | Constructs kinetic network from multiple short simulations | Identifies metastable states and allosteric pathways |

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To overcome the temporal limitations of conventional MD simulations, enhanced sampling techniques have been developed to accelerate the exploration of conformational space. These methods enable researchers to surpass energy barriers that obscure rare conformational events critical to allosteric regulation, thereby revealing hidden allosteric sites inaccessible through conventional MD alone [21].

Collective variable (CV)-based approaches such as metadynamics (MetaD) and umbrella sampling facilitate the exploration of conformational spaces by applying bias potentials along specific CVs involved in allosteric transitions or effector binding events [21]. MetaD introduces time-dependent bias potentials to enable the system to escape local energy minima, facilitating reconstruction of the free energy surface and revealing new conformational states where potential allosteric sites may emerge [21]. Variational Enhanced Sampling (VES) further refines this approach by optimizing a function to determine the optimal bias potential, promoting more efficient exploration of the free energy landscape [21].

When identification of suitable CVs proves challenging, alternative methods including accelerated MD (aMD), replica exchange MD (REMD), and Steered MD (SMD) become invaluable [21]. The aMD approach modifies the potential energy surface by introducing a boost potential, allowing the system to cross high energy barriers and explore broader conformational space, effectively capturing millisecond-timescale events within hundreds of nanoseconds of simulation [21]. REMD involves simulating multiple replicas of the enzyme at different temperatures, with periodic exchanges between replicas to facilitate conformational transitions, thereby enabling exploration of a wider range of conformational states and aiding discovery of allosteric sites hidden in high-energy conformations [21].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Computational Identification of Transient Allosteric States. This workflow illustrates the integrated approach from static structure determination through dynamic simulation to experimental validation of predicted allosteric sites.

Integrated Computational-Experimental Framework

Synergistic Methodologies

The most powerful approaches for investigating transient allosteric states combine computational predictions with experimental validation, creating a synergistic framework that overcomes the limitations of individual methods. This integration leverages the predictive power of computational methods with the empirical validation of experimental techniques, enabling robust identification and characterization of transient allosteric states [32]. Network-based approaches have emerged as particularly valuable in this context, mapping allosteric communication pathways within proteins by representing residue interaction networks where effector binding initiates cascades of coupled fluctuations that propagate through the network and elicit long-range functional responses at distal sites [32].

The understanding of allostery has evolved significantly from rigid structural models to dynamic, network-driven paradigms [3]. Modern computational approaches now reveal the mechanistic basis of allosteric signal transduction by identifying key functional centers and allosteric communication pathways [32]. These network-centric methods represent a powerful complementary strategy to physics-based landscape models of protein dynamics by quantifying global functional changes and identifying residues critical for allosteric signaling [32].

Diagram 2: Allosteric Signal Transduction Pathway. This diagram illustrates the propagation of allosteric signals from effector binding sites to functionally active sites through residue interaction networks.

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced transformative capabilities to allosteric research. ML approaches identify potential allosteric sites from multidimensional biological datasets, while deep learning applications enable modeling of molecular mechanisms and allosteric proteins [3] [32]. The remarkable success of AlphaFold2 in predicting protein structures with high accuracy through deep learning has spurred growing interest in leveraging its capabilities to accelerate allosteric drug discovery [3].

The emerging paradigm of data-centric integration of chemistry, biology, and computer science using artificial intelligence technologies has gained significant momentum and stands at the forefront of many cross-disciplinary efforts [32]. Machine learning can enhance molecular dynamics through data-driven sampling strategies and by augmenting trajectory data for allostery tasks, addressing the data requirements of modern models [3]. The availability of MD repositories, such as the GPCRmd database, provides standardized datasets that facilitate the integration of ML with physics-based simulations [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Allosteric Discovery

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Transient State Analysis in Allosteric Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Metadynamics, aMD, REMD | Overcome energy barriers to explore conformational space | Identification of cryptic allosteric sites |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | MDpocket, Carma | Detect and characterize transient pockets in MD trajectories | Mapping allosteric site formation dynamics |

| Network Analysis Platforms | AlloReverse, PASSer | Identify allosteric pathways and communication networks | Residue interaction network mapping |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | AlphaFold, ESM-2 | Predict protein structures and allosteric potentials | Data-driven allosteric site prediction |

| Free Energy Calculations | Thermodynamic Integration, MBAR | Calculate binding free energies and allosteric调控 thermodynamics | Quantifying allosteric effector potency |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Identification of Cryptic Allosteric Sites Using Enhanced Sampling