Decoding Viral Evolution: A Comprehensive Guide to NGS for Mutation Rate Analysis in Drug Discovery and Clinical Research

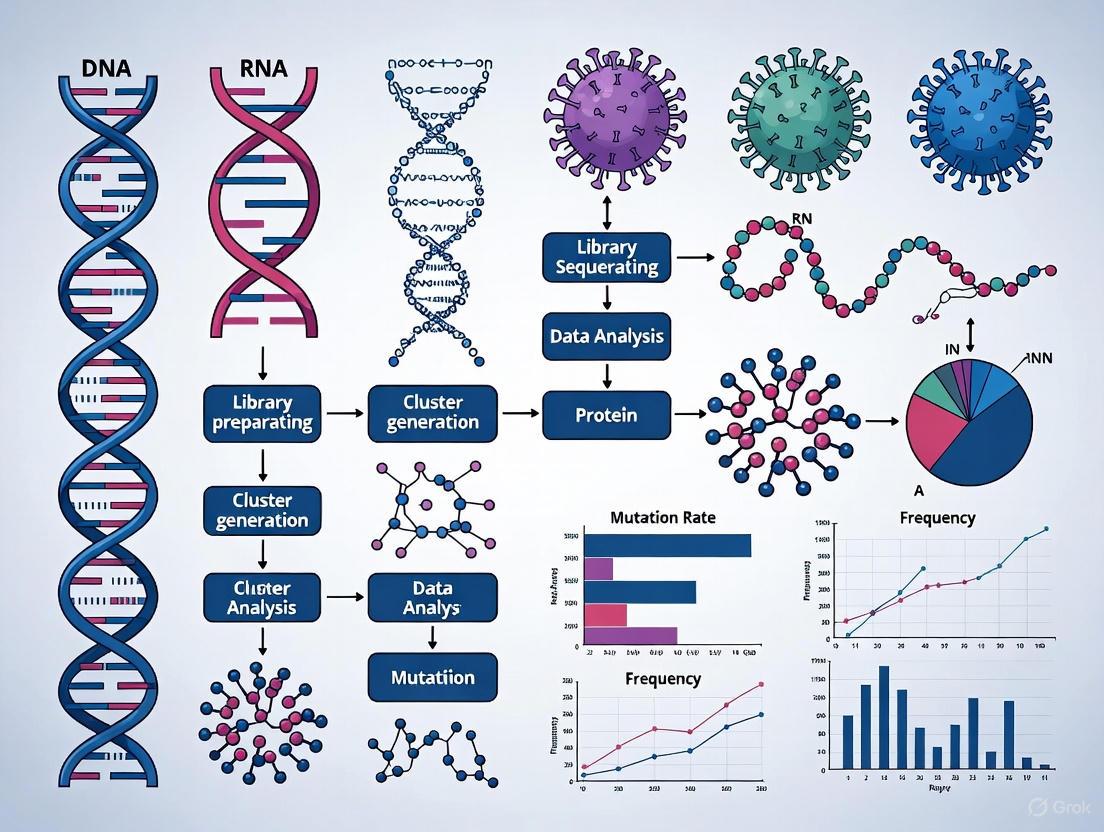

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the tracking and analysis of viral mutation rates, becoming an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how NGS technologies are applied to understand viral evolution, from fundamental principles to advanced clinical applications. We cover the critical methodological approaches for detecting mutations, including strategies for optimizing accuracy and sensitivity to identify low-frequency variants. The content further delves into troubleshooting common challenges, comparing sequencing platforms, and establishing robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing current methodologies and their practical implementations in monitoring antiviral resistance and guiding therapeutic development, this guide serves as an essential resource for advancing viral genomics research and precision medicine.

Decoding Viral Evolution: A Comprehensive Guide to NGS for Mutation Rate Analysis in Drug Discovery and Clinical Research

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the tracking and analysis of viral mutation rates, becoming an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of how NGS technologies are applied to understand viral evolution, from fundamental principles to advanced clinical applications. We cover the critical methodological approaches for detecting mutations, including strategies for optimizing accuracy and sensitivity to identify low-frequency variants. The content further delves into troubleshooting common challenges, comparing sequencing platforms, and establishing robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing current methodologies and their practical implementations in monitoring antiviral resistance and guiding therapeutic development, this guide serves as an essential resource for advancing viral genomics research and precision medicine.

Viral Mutation Fundamentals: From Molecular Mechanisms to NGS Detection Principles

The study of viral mutation rates is a cornerstone of virology, with profound implications for understanding viral evolution, pathogenesis, and the development of effective countermeasures. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized this field by providing unprecedented resolution to detect and quantify genetic variations within viral populations. The mutational landscape of viruses is not merely an academic curiosity; it directly impacts pandemic preparedness, vaccine design, and therapeutic development. This application note examines the distinct mutational profiles of DNA and RNA viruses, with a specific focus on insights gained through advanced NGS methodologies. We present standardized protocols for mutation rate quantification, detailed experimental designs for comparative studies, and key reagent solutions to support research in this critical area.

Quantitative Comparison of Viral Mutation Rates

Data compiled from recent studies utilizing NGS methodologies reveal significant differences in mutation rates between RNA viruses and between RNA and DNA viruses. These quantitative measurements provide a foundation for understanding viral evolution and adaptive potential.

Table 1: Comparative Mutation Rates of Viruses Measured by NGS Approaches

| Virus | Genome Type | Mutation Rate (substitutions/site/passage) | Mutation Spectrum Bias | Primary NGS Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | +ssRNA | ~1.5 × 10â»â¶ [1] | Dominated by C→U transitions [1] | CirSeq [1] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | +ssRNA | 3.76 × 10â»â¶ [2] | Mostly transitions [2] | RT-PCR Cloning & Sanger Sequencing [2] | |

| Influenza A Virus (IAV) | -ssRNA | 9.01 × 10â»âµ [2] | Similar transitions/transversions [2] | RT-PCR Cloning & Sanger Sequencing [2] | |

| Poliovirus | +ssRNA | ~1 × 10â»âµ [1] | Not Specified | CirSeq [1] |

The data in Table 1 highlight a critical finding: the presence of a proofreading mechanism can profoundly alter the mutational landscape of an RNA virus. SARS-CoV-2, which possesses a proofreading 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease activity in its nsp14 protein [2] [3], exhibits a mutation rate approximately 23.9-fold lower than that of Influenza A Virus, which lacks such a repair system [2]. This difference underscores why mutation rates can vary significantly even within the same broad category of RNA viruses.

Experimental Protocols for Mutation Rate Determination

Accurate determination of mutation rates relies on robust experimental designs and precise sequencing protocols. Below, we detail two key methodologies applied in recent viral studies.

Protocol 1: Circular RNA Consensus Sequencing (CirSeq) for High-Fidelity Mutation Detection

Application: This protocol is designed for the ultra-sensitive detection of spontaneous mutations in viral RNA genomes, minimizing sequencing errors to reveal the true mutational landscape [1] [4].

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the key steps in the CirSeq protocol, from RNA sample preparation to final mutation calling:

Procedure:

- Viral RNA Fragmentation: Purify viral RNA and fragment it into short pieces (~200-400 nucleotides) using controlled hydrolysis or enzymatic methods [1].

- RNA Circularization: Circulate the fragmented RNA molecules using RNA ligase. This step creates a template for generating tandem repeats during the subsequent reverse transcription [1] [4].

- cDNA Synthesis and Amplification: Perform reverse transcription on the circularized RNA. The polymerase circles the template, generating a complementary DNA (cDNA) molecule containing long tandem repeats of the original sequence. Amplify this cDNA for sequencing [1].

- NGS Library Prep and Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the amplified cDNA and sequence it using a high-throughput NGS platform (e.g., Illumina) [1] [5].

- Consensus Building and Mutation Calling: Bioinformatically process the sequencing reads. Align the tandem repeats from each original RNA molecule to generate a high-accuracy consensus sequence, effectively eliminating errors introduced during reverse transcription and sequencing. Compare these consensus sequences to the reference genome to identify true mutations [1] [4].

Protocol 2: Serial Passaging and Targeted Gene Analysis

Application: This method is used for direct comparative measurement of mutation rates between different viruses under controlled cell culture conditions, often focusing on specific genes of interest like surface glycoproteins [2].

Workflow Overview: The logical flow of the serial passaging experiment is shown below:

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Infection: Use cell lines susceptible to the viruses under study (e.g., Calu-3 human lung epithelial cells for respiratory viruses). Infect cells at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI=0.1-1) to minimize co-infection and complementation effects [1] [2].

- Serial Virus Passaging: Harvest the virus-containing culture supernatant after a fixed period (e.g., 48 hours). Use this supernatant to infect fresh cells. Repeat this process for multiple passages (e.g., 15 passages) to allow for the accumulation of mutations [2].

- Viral RNA Extraction and Gene Targeting: After the final passage, extract viral RNA from the supernatant. Use Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) with gene-specific primers to amplify target regions (e.g., the Spike (S) gene for SARS-CoV-2 or the Hemagglutinin (HA) and Neuraminidase (NA) genes for Influenza) [2].

- Cloning and Sequencing: Clone the RT-PCR products into plasmids. Sequence a sufficient number of clones (e.g., 20 per passage line) to detect mutations and determine their frequency [2].

- Mutation Rate Calculation: Calculate the mutation rate using the formula: Mutation Rate = (Total number of mutations / Total number of nucleotides sequenced) / Number of passages [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of the aforementioned protocols requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for viral mutation rate studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Mutation Rate Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptible Cell Lines | Provides a permissive system for viral replication and serial passaging. | VeroE6 cells (for high viral diversity) [1]; Calu-3 (human lung adenocarcinoma, physiologically relevant) [1] [2]. |

| Ultra-Sensitive NGS Kits | Library preparation for high-fidelity sequencing. | CirSeq library prep kits [1]; Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis kits [5]. |

| Viral RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality, intact viral RNA from culture supernatants or clinical samples. | Kits based on silica-membrane column technology or magnetic beads. |

| Reverse Transcriptase & PCR Kits | Amplification of specific viral genomic regions for cloning and sequencing. | High-fidelity RT-PCR kits to minimize polymerase-introduced errors during amplification [2]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Consensus sequence generation, variant calling, and mutation spectrum analysis. | Custom CirSeq data analysis pipelines [1]; BWA/GATK for short-read data; specialized tools for quasispecies reconstruction [4]. |

| A2 | A2, CAS:131816-87-0, MF:C21H15N5O10S2, MW:561.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Bromomethyl-1,2-dinitrobenzene | 4-Bromomethyl-1,2-dinitrobenzene, CAS:114872-53-6, MF:C7H5BrN2O4, MW:261.03 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion and Evolutionary Implications

The empirical data generated through NGS-based protocols reveal fundamental evolutionary strategies. The high mutation rate of Influenza A virus facilitates rapid antigenic drift, allowing it to escape host immunity and necessitating annual vaccine reformulation [2] [3]. Conversely, the lower mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2, enabled by its proofreading mechanism, may be a necessary adaptation to maintain the integrity of its large (~30 kb) genome [1] [3]. However, its global spread and high replication volume provide ample opportunity for fitter variants to emerge, as observed with the Omicron lineage and its sub-lineages [6].

The biased mutation spectrum, particularly the C→U transitions dominant in SARS-CoV-2, points to specific underlying mutational processes, such as cytidine deamination, which may represent a therapeutic target [1]. Furthermore, the finding that mutation rates are reduced in regions of RNA secondary structure highlights an additional layer of genomic constraint where synonymous mutations can have significant fitness costs [1].

Next-generation sequencing has provided a refined, quantitative understanding of viral mutation rates, moving beyond broad generalizations to reveal the precise mechanisms and constraints that shape viral evolution. The protocols and reagent solutions outlined in this application note provide a framework for researchers to accurately measure and compare these critical parameters. As NGS technologies continue to advance, becoming more sensitive and accessible, their application in tracking viral evolution in near real-time will be invaluable for public health responses, drug discovery, and the design of next-generation, resilient vaccines.

The field of viral genomics has undergone a profound transformation, moving from targeted, sequence-dependent methods to an era of untargeted, high-throughput genomic surveillance. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a powerful tool that provides unparalleled capabilities for analyzing viral DNA and RNA molecules in a high-throughput and cost-effective manner [5]. This revolutionary technology allows researchers to sequence millions of nucleic acid fragments simultaneously, providing comprehensive insights into viral genome structure, genetic variations, and evolutionary dynamics [5].

The evolution of sequencing technologies is vividly illustrated by comparing the discovery of three major zoonotic coronaviruses. In 2002/2003, SARS-CoV-1 was identified using a combination of virus isolation, electron microscopy, serology, and partial genome sequencing via Sanger technology. A decade later, the identification of MERS-CoV in 2012 leveraged similar methods but incorporated whole genome sequencing using the Roche 454 short-read NGS platform. In 2019, SARS-CoV-2 was directly identified from patient samples using short-read mNGS with the Illumina platform, producing a complete viral genome sequence within days [7]. This progression highlights how NGS has dramatically accelerated and broadened our ability to characterize viral pathogens.

The NGS Technology Landscape

The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of viral genomics research, facilitating studies on viral evolution, outbreak investigation, and vaccine development. Various sequencing platforms offer distinct advantages depending on the specific application requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Sequencing Technologies for Viral Genomics

| Technology | Read Length | Error Rate | Key Strengths | Best Applications in Virology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 50-300 bp | 0.1-1.0% | High accuracy, high throughput, high sensitivity | Variant calling, genomic surveillance, low-frequency mutation detection |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Up to 1+ Mb | 1-15% | Long read length, portability, real-time sequencing | Rapid outbreak investigation, genome finishing, structural variation |

| PacBio HiFi | 10,000-25,000 bp | <1% (with circular consensus) | Long reads with high accuracy | De novo genome assembly, complex strain discrimination |

| Ion Torrent | 200-400 bp | ~1% | Fast run times, semiconductor detection | Rapid diagnostics, targeted sequencing |

NGS technologies are broadly categorized into second-generation (short-read) and third-generation (long-read) platforms. Short-read technologies like Illumina provide high accuracy and are ideal for detecting single nucleotide variants and performing quantitative analyses [7]. Long-read technologies such as Oxford Nanopore and PacBio excel at resolving complex genomic regions, detecting structural variations, and achieving complete de novo genome assemblies without the need for reference-based mapping [5] [7].

The choice between these technologies depends on the specific research goals. For comprehensive viral discovery where no prior sequence information exists, long-read sequencing provides advantages in assembling complete genomes. For sensitive detection of minor variants in a viral population, short-read sequencing offers the depth and accuracy required to identify mutations present at low frequencies [8].

Key Applications in Viral Genomics

Viral Discovery and Metagenomics

Viral metagenomic next-generation sequencing (vmNGS) has transformed our capacity for the untargeted detection and characterization of emerging zoonotic viruses, surpassing the limitations of traditional targeted diagnostics [7]. This sequence-independent approach enables detection without prior genetic information, making it invaluable for outbreak investigations of unknown etiology.

vmNGS supports comprehensive viral genome surveillance, enabling real-time monitoring of viral evolution, identification of origins, and tracking of dissemination routes. Its application is particularly crucial within the One Health paradigm, which recognizes the interdependence of animal, environmental, and human health [7]. Approximately 60-80% of emerging human viruses have zoonotic origins, and vmNGS provides a central tool for early warning at the human-animal-environment interface [7].

Tracking Viral Mutations and Evolution

NGS enables high-resolution characterization of individual mutations in viral genomes, providing insights into evolutionary dynamics and treatment responses. Targeted NGS approaches using enrichment strategies allow researchers to focus sequencing on specific genomic regions, enabling deeper coverage and detection of rare variants [9].

For example, in studying evolving bacterial populations, researchers used xGen Lockdown Probes to perform target enrichment of commonly mutated genes [9]. This approach enabled them to track the frequency of mutations in evolving populations with sufficient sensitivity to detect competing mutations when they were still "new" and very rare within the population. Similar approaches can be applied to monitor the evolution of viruses, including key oncogenes in cancer-associated viruses [9].

In HIV research, NGS has revolutionized the tracking of drug resistance mutations (DRMs). Unlike Sanger sequencing, NGS can detect minority variants present in 1% to 20% of the viral population, which may increase the risk of treatment failure [10]. This additional information regarding relative abundance of susceptible/resistant strains strengthens our ability to assess the clinical impact of a given DRM and guide treatment strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Viral Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for viral metagenomic sequencing:

Viral Genome Enrichment Protocol for Avian Orthoreoviruses

Sample Preparation and Viral Culture Conditions:

- Inoculate LMH cell monolayers at 95% confluency with viral inoculum

- Incubate at 38°C with 5% CO₂ for 5 days

- Harvest infected cells and supernatant by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes

- Resuspend pellet in virus dilution buffer and sonicate on ice (3 pulses at 30% amplitude, 10s on/30s off) [8]

ARV Genome Enrichment Protocol:

- Virion Purification: Use Capto Core 700 resin for initial purification

- Host rRNA Depletion: Treat with custom ssDNA probes targeting chicken rRNA, RNase H, and DNase I

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert viral RNA to cDNA using ARV-specific primers

- Single Primer Amplification PCR (R-SPA): Amplify cDNA using ARV-specific primers [8]

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- For Illumina short-read sequencing: Use Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit with IDT for Illumina DNA/RNA UD Indexes

- For Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing: Follow ONT Rapid sequencing gDNA barcoding protocol

- Sequence Illumina libraries on MiSeq using Nano Kit v2 (500 cycles)

- Sequence ONT libraries on GridION platform [8]

Target Enrichment for Tracking Rare Mutations

Population Sequencing with Target Enrichment:

- Grow successive generations of microbial populations in liquid culture with daily transfers

- Monitor population dynamics using phenotypic markers (e.g., araA+/araA– clones on indicator agar)

- Isolate genomic DNA after desired generations (~500 generations)

- Prepare Illumina libraries with custom adapters containing barcoding sequences

- Perform target enrichment using ~120 xGen Lockdown Probes targeting genes of interest

- Follow Nimblegen SeqCap protocol with 72-hour hybridization

- Perform stringent washes with hard vortexing using reagents heated to 90°C

- Sequence enriched DNA on Illumina HiSeq platform [9]

Bioinformatic Analysis for Mutation Tracking:

- For improved confidence in rare variant calls, consider duplex sequencing using adapters with 12 random bases at the 3' end

- Use random barcodes to identify reads arising from the same gDNA molecule

- Generate consensus sequences to eliminate errors from single reads

- Track mutation frequencies across time points to calculate fitness effects [9]

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral NGS

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| xGen Lockdown Probes | Target enrichment for specific genomic regions | Capturing viral genes of interest for deep sequencing [9] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for Illumina platforms | Preparing metagenomic libraries from viral cDNA [8] |

| Capto Core 700 Resin | Virion purification | Initial purification of viral particles from cell culture [8] |

| Custom ssDNA Probes | Host rRNA depletion | Removing chicken rRNA from avian virus samples [8] |

| Universal Probe Library (UPL) | Quantitative digital PCR | Absolute quantification of NGS libraries [11] |

| ONT Rapid Barcoding Kit | Library preparation for Nanopore | Rapid barcoding of viral genomes for long-read sequencing [8] |

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics Pipeline

Quality Control and Preprocessing:

- For Illumina reads: Use Trimmomatic with Phred score threshold >30 [8]

- For Nanopore reads: Apply NanoFilt with Q value threshold of 7, then trim with Porechop [8]

Assembly Methods Comparison:

- De novo assembly: Use SPAdes for short reads or Canu/Flye for long reads

- Reference-guided assembly: Map quality-trimmed reads to custom reference genome using BWA or minimap2

- Hybrid assembly: Combine short and long reads for improved assembly quality [8]

Studies comparing assembly methods for avian orthoreoviruses found that regardless of sequencing technology, the best quality assemblies were generated by mapping quality-trimmed reads to a custom reference genome constructed from publicly available ARV genomic segments with highest sequence similarity to de novo contigs [8].

Quantitative Comparison Methods: For quantitative comparison of sequencing datasets, statistical methods like ChIPComp account for background signals, signal-to-noise ratios, biological variations, and multiple-factor experimental designs [12]. These methods model read counts following Poisson distribution, with underlying rates accounting for both technical artifacts and biological signals, enabling robust differential analysis [12].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite its transformative potential, implementing NGS in viral genomics faces several challenges. Workflow complexity involves multiple steps with potential variables that need careful control [10]. Rigorous validation of equipment, methods, and processes is essential to ensure accurate, reproducible, and reliable results [10].

Cost and infrastructure requirements remain significant barriers, particularly for clinical settings and resource-limited environments [7]. The need for confirmation by secondary validated methods further complicates clinical implementation [10].

Data management and analysis present substantial hurdles, as NGS generates enormous datasets requiring sophisticated computational infrastructure and bioinformatics expertise [5] [10]. Interpretation of results often requires specialized knowledge, as seen with HIV drug resistance mutation profiling [10].

Looking forward, the field is moving toward more integrated surveillance systems based on the One Health approach [7]. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, becoming more efficient, scalable, and cost-effective, NGS is poised to become a central tool for global pandemic preparedness and zoonotic disease control [5] [7]. The development of novel algorithms for data analysis and improved quantification methods will further enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from the vast datasets generated by these powerful technologies [5] [11].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become a cornerstone for tracking viral evolution and detecting mutations that confer drug resistance. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and resources for researchers focusing on the key genetic targets and methodologies essential for robust viral mutation rate studies.

The error-prone replication of viruses, combined with selective pressure from antiviral therapies, drives the emergence of drug-resistant viral variants. The traditional view that DNA viruses, such as herpesviruses, evolve slowly has been overturned; growing evidence shows they exist as dynamic populations with significant standing variation [13]. For instance, herpes simplex virus (HSV) populations can exhibit mutation frequencies as high as 3.6 x 10^-4 substitutions per base per plaque transfer, and nucleotide variations can be found in up to 3-4% of the HSV-1 genome between strains [13]. Detecting these minority variants, which can rise to dominance and cause treatment failure, requires sensitive and high-throughput sequencing approaches [13] [14]. Targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) offers a powerful, culture-independent solution, enabling comprehensive resistance profiling directly from clinical samples with high sensitivity and a relatively low cost [15] [16].

Key Viral Genetic Targets for Drug Resistance

Resistance mutations are not uniformly distributed across viral genomes; they are often concentrated in specific genes that are the targets of antiviral drugs. The table below summarizes critical genetic targets for major human viruses.

Table 1: Key Genetic Targets for Drug Resistance in Clinically Significant Viruses

| Virus | Genome Type | Key Target Genes/Proteins | Associated Antiviral Drugs | Clinical Impact of Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) | RNA | Protease (PR), Reverse Transcriptase (RT), Integrase (IN) [14] | Protease inhibitors, NRTIs, NNRTIs, Integrase inhibitors [14] | Treatment failure across multiple drug classes [14] |

| Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) | DNA | Reverse Transcriptase/Polymersase (RT) [14] | Nucleos(t)ide analogues (e.g., Lamivudine, Entecavir) [14] | Reduced efficacy of first-line treatments [14] |

| Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | RNA | NS3, NS5A, NS5B [14] | Protease inhibitors, NS5A inhibitors, NS5B polymerase inhibitors [14] | Compromised efficacy of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens [14] |

| Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1/2) | DNA | Thymidine Kinase (UL23), DNA Polymerase (UL30) [13] | Acyclovir, Famiciclovir [13] | Reduced susceptibility to first-line therapies [13] |

| Influenza A Virus (IAV) | RNA | Neuraminidase (NA), Matrix 2 (M2), Polymerase complex (PB2, PB1, PA) [17] | Oseltamivir, Zanamivir, Adamantanes [17] | Limited treatment options, especially during outbreaks [17] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | DNA | katG, inhA, rpoB, pncA, gyrA, gyrB, rpsL, rrs [16] | Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Pyrazinamide, Fluoroquinolones [16] | Emergence of multi-drug (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB [16] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | RNA | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), Spike (S) protein [14] | Remdesivir, Nirmatrelvir, monoclonal antibodies [14] | Escape from neutralizing antibodies and antiviral agents [14] |

Quantitative Performance of NGS in Resistance Detection

The analytical performance of NGS methods is critical for reliable variant detection. The following table compiles key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of NGS Methodologies for Resistance Detection

| Methodology / Platform | Virus / Pathogen | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted NGS (tNGS) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 95.1% concordance with phenotypic AST; 87.95% positive rate in confirmed TB cases (vs 80.72% for Xpert MTB/RIF) [16] | [16] |

| Short-Read Sequencing (Illumina iSeq100/MiSeq) | HIV-1, HBV, HCV, TB, SARS-CoV-2 | High concordance for majority and minority variants; Q30 scores ≥80%; low error rates (<1%) [14] | [14] |

| Long-Read Sequencing (Oxford Nanopore MinION) | HIV-1, HBV, HCV, TB, SARS-CoV-2 | High concordance for majority subtypes; detected a higher number of minority mutations (<20%) compared to short-read platforms [14] | [14] |

| Optimized Whole-Genome Sequencing (Nanopore) | Influenza A Virus (IAV) | Robust whole-genome amplification from avian, swine, and human samples with low viral loads; enabled high-throughput multiplexing [17] | [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Targeted NGS of Viral Genes

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for tNGS of viral genomes, adaptable for viruses like HIV, HBV, and HCV, based on established methods [14].

Sample Preparation and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Sample Type: 200 µL of plasma, serum, or other clinical samples (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) [16] [14].

- Extraction Method: Automated nucleic acid extraction is recommended for consistency. Use platform-specific kits, such as the MagNA Pure system (Roche) or the KingFisher Apex (Thermo Fisher Scientific) [14] [17].

- Quality Control: Quantify extracted nucleic acids using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit Flex). For RNA samples, assess integrity if possible. Include positive and negative extraction controls to monitor for contamination [16] [14].

Target Amplification

This step uses multiplex PCR to amplify genomic regions associated with drug resistance.

- Principle: Pathogen-specific primer sets are used to generate amplicons covering known and potential drug resistance mutations under standardized conditions [14].

- Reaction Setup:

- Primers: Use commercially available, validated primer sets (e.g., DeepChek Assays) or published primers targeting critical regions (e.g., HIV pol gene, HBV RT gene) [14].

- Cycling Conditions (Example):

- Amplicon QC: Verify amplification success and specificity by running 5 µL of the PCR product on an agarose gel (e.g., E-Gel System) [14].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

This protocol is based on the Illumina platform [14].

- Purification and Quantification: Pool PCR amplicons if multiple regions were amplified separately. Purify the pool using magnetic beads (e.g., AMPure XP). Quantify the purified DNA with a fluorometer [14].

- Library Preparation: Use a commercial NGS library prep kit (e.g., DeepChek NGS Library preparation kit).

- Fragmentation and End-Repair: Enzymatically fragment 3 ng/µL of the amplicon pool at 37°C for 30 min, followed by end-repair and A-tailing [14].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate indexed adapters to the fragments at 20°C for 15 min [14].

- Library Amplification: Perform 8 cycles of PCR to enrich the adapter-ligated fragments [14].

- Library QC and Normalization:

- Size Selection: Clean up the library with magnetic beads (0.8x ratio) to remove fragments outside the 200-800 bp range [14].

- Quality Assessment: Analyze 1 µL of the library on a fragment analyzer (e.g., TapeStation 4150) to confirm a peak at ~400 bp and the absence of primer-dimers [14].

- Quantification: Quantify the final library by qPCR to ensure a minimum concentration of 2 ng/µL [14].

- Sequencing:

Bioinformatic Analysis

A standardized pipeline is required to translate raw sequencing data into actionable mutation reports.

- Base Calling and Demultiplexing: Generate FASTQ files and assign reads to samples based on their unique indices [18].

- Read Processing: Trim low-quality bases and adapter sequences from the reads.

- Alignment: Map processed reads to a reference genome (e.g., HXB2 for HIV-1) using aligners like BWA or Bowtie2 [18].

- Variant Calling: Identify nucleotide variants relative to the reference, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (indels). Use specialized variant callers (e.g., DeepVariant) for high accuracy [19].

- Variant Annotation and Reporting: Annotate called variants with functional consequences (e.g., amino acid change) and known associations with drug resistance using databases like the WHO mutation catalog for TB [16]. Report mutations as consensus or minority variants based on a predefined frequency threshold (e.g., ≥5% or ≥20%) [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and tools required for successful implementation of viral resistance sequencing.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Viral tNGS

| Item | Function / Application | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality viral DNA/RNA from clinical samples. | MagNA Pure Kits (Roche), QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), KingFisher Automated Systems [14] [17] |

| Target-Specific Primer Panels | Amplification of drug resistance-associated genomic regions. | DeepChek Assays (ABL Diagnostics) [14], custom-designed primer pools [17] |

| High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix | Accurate amplification of target sequences with low error rates. | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB), LunaScript RT Master Mix (NEB) [17] |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Preparation of amplified DNA for sequencing on NGS platforms. | DeepChek NGS Library Prep Kit (ABL Diagnostics) [14] |

| NGS Sequencing Platform | High-throughput sequencing of prepared libraries. | Illumina (iSeq100, MiSeq), Oxford Nanopore (MinION) [14] [19] |

| Bioinformatics Software | Data analysis, variant calling, and interpretation of resistance mutations. | DeepChek Software (ABL Diagnostics), DeepVariant (Google) [14] [19] |

| Reference Materials & Controls | Ensuring assay accuracy, precision, and detecting contamination. | QCMD Panels, positive/negative extraction controls, non-template controls (NTC) [16] [14] |

| Alfalone | Alfalone, CAS:970-48-9, MF:C17H14O5, MW:298.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Brassicasterol | Brassicasterol, CAS:474-67-9, MF:C28H46O, MW:398.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The precise identification of genetic targets for antiviral drug resistance is fundamental to effective therapy and public health surveillance. tNGS provides a powerful and flexible framework for detecting both majority and minority resistant variants across a broad spectrum of viruses. The protocols and resources detailed in this application note provide a roadmap for researchers to implement robust sequencing assays, enabling deeper insights into viral evolution and the preemptive management of treatment failure.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the study of viral pathogens by enabling researchers to analyze viral populations with unprecedented depth and resolution. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, which produces a consensus sequence, NGS can sequence millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, providing critical insights into genetically heterogeneous viral populations known as quasispecies [20] [5]. This technological advancement is particularly valuable for understanding viral evolution, as RNA viruses like Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) mutate at remarkably high rates, with HIV-1 exhibiting mutation rates as high as 10â»Â³ nucleotide substitutions per site per year [20]. The error-prone activity of viral reverse transcriptase (RT) is largely responsible for this observed variability, creating complex distributions of closely related variant genomes that facilitate rapid adaptation to environmental pressures, including antiretroviral therapy [20].

The application of NGS in virology has opened new avenues for connecting specific genetic mutations to treatment outcomes, particularly through the identification of resistance-associated mutations (RAMs) that reduce drug efficacy. Numerous HIV-related outcomes can be determined from the viral genome, including resistance profiles, population transmission dynamics, viral heritability traits, and time since infection [21]. The shift from Sanger sequencing to NGS in HIV research over the past decade has been crucial because NGS achieves near full-length genome sequence coverage while simultaneously characterizing within-host diversity by encapsulating HIV subpopulations [21]. This detailed genetic information is essential for developing effective treatment strategies and understanding treatment failure mechanisms, making NGS an indispensable tool in both clinical virology and drug development pipelines.

Key NGS Technologies and Platforms

The selection of appropriate NGS platforms is fundamental to successful viral genomics research. Second-generation sequencing methods, often called short-read technologies, form the backbone of most current viral sequencing applications due to their high accuracy and throughput [5]. The Illumina platform utilizes a sequencing-by-synthesis method based on reversible dye terminators, making it particularly suitable for detecting single nucleotide variants and achieving high coverage depths necessary for identifying minority variants in viral populations [5]. However, researchers must be aware that sample overloading on Illumina platforms can result in overcrowding or overlapping signals, potentially increasing error rates to approximately 1% [5].

Third-generation sequencing technologies, exemplified by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing and Oxford Nanopore sequencing, offer distinct advantages for specific viral genomics applications [5]. These platforms generate long reads that are invaluable for resolving complex genomic regions, haplotyping, and detecting structural variations. PacBio SMRT sequencing employs specialized cells housing numerous zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) where individual DNA molecules are immobilized, with light emissions measured in real-time as polymerase incorporates nucleotides [5]. While PacBio systems traditionally focused on long-read sequencing, the recent introduction of the PacBio Onso system utilizes sequencing by binding (SBB) chemistry for short-read applications, providing an alternative to traditional Illumina workflows [5].

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Platforms for Viral Genomics

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Key Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Viral Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 36-300 bp | High accuracy, low cost per base, high throughput | Short reads limit haplotype resolution | Variant calling, resistance mutation profiling, population diversity |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time | Average 10,000-25,000 bp | Long reads, direct epigenetics | Higher cost, lower throughput | Full-length viral genome assembly, complex variant detection |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | Average 10,000-30,000 bp | Ultra-long reads, real-time analysis, portability | Higher error rate (~15%) | Rapid outbreak investigation, large structural variants |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor | 200-400 bp | Fast run times, simple workflow | Homopolymer errors | Targeted viral sequencing, resistance testing |

The computational requirements for NGS data analysis represent a critical consideration for research design. NGS data analysis is computationally intensive, requiring storage, transfer, and processing of very large data files that typically range from 1–3 GB in size [22]. Access to advanced computing resources, either on-site via private networks or cloud-based solutions, is highly recommended for efficient data processing [22]. Furthermore, while many user-friendly bioinformatic tools are available, researchers often require scripting and coding skills in languages such as Python, Perl, R, and Bash, typically performed within Linux or Unix-like operating environments [22].

NGS Data Analysis Framework

The analysis of NGS data follows a structured framework comprising three core stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary analysis [22]. Each stage transforms the data progressively from raw sequencing outputs to biologically meaningful conclusions about viral mutations and their potential clinical significance. Understanding this workflow is essential for properly interpreting NGS data in the context of viral resistance research.

Primary Analysis

Primary analysis begins with the assessment of raw sequencing data for quality control and initial processing [22]. For Illumina sequencing, the input is typically a binary base call (BCL) file containing raw intensity measurements and nucleotide base identifications [22]. Specialized software, such as bcl2fastq Conversion Software, processes these files to generate text-based FASTQ files, which contain the nucleotide sequences along with quality scores for each base [22]. During this stage, several critical quality metrics are assessed, including total sequencing yield, error rates based on internal controls, Phred quality scores (with Q>30 indicating <0.1% base call error rate), percentage of sequences aligned to control genomes, cluster density, and phasing/prephasing percentages [22].

A crucial step in primary analysis is demultiplexing, which separates sequencing data from multiple library samples that were processed concurrently [22]. Each sample is identified by unique index sequences, and demultiplexing generates individual FASTQ files corresponding to each sample in the experiment [22]. These files contain read names, flow cell locations, and other identifying information necessary for downstream analysis. Proper quality control at this stage is vital, as issues with sequencing efficiency or sample misidentification can compromise all subsequent analyses.

Secondary Analysis

Secondary analysis converts the raw sequence data into biologically interpretable results through a series of computational steps [22]. The process begins with read cleanup, where low-quality sequence reads and portions of reads are removed or trimmed—a process known as "soft-clipping" [22]. Tools like FastQC provide comprehensive quality assessment, including per-base quality scores, sequence quality distribution, GC content, and identification of duplicate or overrepresented sequences [22]. For viral RNA sequencing, additional specialized cleanup steps may include correction of sequence bias introduced during library preparation, quantitation of RNA types (such as ribosomal RNA contaminants), and determination of strandedness when directional sequencing kits are used [22].

Following quality control, sequencing reads are aligned to reference genomes using tools such as BWA or Bowtie 2 [22]. The choice of reference genome is critical, as inconsistencies can introduce artifacts in variant calling. For HIV research, standard references like HXB2 are commonly used, but researchers must document and consistently apply their chosen reference to ensure reproducibility [22]. The output from alignment is typically stored in Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files, which provide a compressed, efficient format for storing sequence alignment data [23]. These files can be visualized using genome browsers like the Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV), allowing researchers to inspect read alignments, identify pileups in specific regions, and visually confirm potential mutations [22].

The final stage of secondary analysis involves mutation calling, where genetic variations that differ from the reference genome are identified [22]. For viral research, this includes identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, deletions, and other anomalies. The output is typically stored in Variant Call Format (VCF) files, which provide a standardized, text-based format for storing gene sequence variations [22]. For gene expression analysis in viral studies, tab-delimited formats (TSV files) are often used, with columns representing samples, genes, raw counts, and normalized counts [22].

Tertiary Analysis

Tertiary analysis represents the final stage where biological meaning is extracted from the processed data [22]. In the context of viral resistance research, this involves connecting identified mutations to known resistance profiles, interpreting their potential impact on treatment outcomes, and generating actionable reports. This stage often integrates additional data sources, including clinical patient information, drug treatment histories, and existing knowledge bases of resistance-associated mutations.

Experimental Protocol: NGS for HIV Drug Resistance Profiling

This section provides a detailed protocol for using NGS to profile HIV drug resistance mutations, based on established methodologies from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study and other research initiatives [21].

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

Begin with plasma samples from HIV-positive patients, ensuring proper ethical approvals and informed consent are obtained. Viral RNA should be extracted from 500-1000 μL of patient plasma using commercial viral RNA extraction kits. Include appropriate controls: negative extraction controls (nuclease-free water) and positive controls with known viral titers. Convert extracted RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with gene-specific primers targeting the HIV pol gene, which encodes viral enzymes including reverse transcriptase and protease—primary targets of antiretroviral drugs.

Amplify the cDNA using a nested PCR approach with primers designed to target the entire protease gene and the first 1,000 nucleotides of the reverse transcriptase gene. This amplification strategy ensures adequate coverage of genomic regions where most known resistance-associated mutations occur. Purify PCR products using magnetic bead-based clean-up systems and quantify using fluorometric methods. For library preparation, utilize commercial library preparation kits compatible with your sequencing platform. During library preparation, incorporate unique dual indexes (UDIs) to enable multiplexing of multiple samples while preventing index hopping issues. Validate the final libraries using capillary electrophoresis systems to confirm appropriate fragment sizes and the absence of primer dimers.

Sequencing and Data Processing

Dilute libraries to appropriate concentrations and pool based on the desired sequencing depth. For viral resistance profiling, a minimum coverage of 10,000x per base is recommended to reliably detect low-frequency variants present at 1% or higher. Sequence the pooled libraries on an Illumina platform using a 2x150 bp paired-end sequencing strategy to ensure adequate overlap for read merging and high-quality consensus calling.

Process the raw sequencing data through the primary and secondary analysis workflow as described in Section 3. Begin by converting BCL files to demultiplexed FASTQ files using bcl2fastq software. Perform quality assessment of the FASTQ files using FastQC, then trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt. Align the processed reads to the HXB2 reference HIV genome using optimized aligners such as BWA or Bowtie2. Process the resulting SAM files into sorted BAM files, then mark and remove PCR duplicates using tools like Picard Tools. Call variants using a specialized viral variant caller such as LoFreq or VarScan2, which are optimized for detecting low-frequency variants in viral populations.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Viral NGS

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Commercial viral RNA kits | Isolate viral RNA from plasma | Evaluate yield and purity; avoid degradation |

| Reverse Transcriptase | MLV RT, AMV RT, thermostable RTs | cDNA synthesis from RNA template | Fidelity impacts mutation detection accuracy [20] |

| PCR Enzymes | High-fidelity DNA polymerases | Amplify target viral sequences | Minimize introduction of amplification errors |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina Nextera, Swift Accel | Fragment DNA and add adapters | Compatibility with sequencing platform is critical |

| Quantification Kits | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay | Accurate DNA quantification | Fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometric |

| Unique Dual Indexes | Illumina IDT UDIs | Sample multiplexing | Reduce index hopping and cross-contamination |

Resistance Mutation Analysis

Annotate identified variants using specialized databases such as the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database. Categorize mutations based on their known association with resistance to specific drug classes: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs). Generate a comprehensive resistance report that includes the frequency of each resistance-associated mutation, the associated drug resistance levels, and potential cross-resistance patterns. For clinical interpretation, follow established guidelines from organizations such as the International Antiviral Society-USA.

Advanced Methods for Studying Viral Mutation Rates

Understanding the intrinsic mutation rates of viruses provides crucial insights into their evolutionary dynamics and capacity for developing drug resistance. Several advanced NGS-based methods have been developed specifically for characterizing the fidelity of viral reverse transcriptases and RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, addressing the limitations of traditional enzymatic and reporter-based assays [20].

The PRIMER ID method incorporates unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) during the reverse transcription step, allowing researchers to distinguish true biological mutations from errors introduced during PCR amplification and sequencing [20]. Each cDNA molecule is tagged with a random oligonucleotide "primer ID," enabling bioinformatic tracking of amplification products derived from the original viral RNA molecule. This approach significantly reduces artifacts and provides more accurate measurements of viral mutation frequencies.

Other specialized methods include Circular Sequencing (CIR-SEQ), which uses circularization of RNA templates to achieve multiple passes of sequencing, thereby enhancing accuracy, and Single-Molecule Real-Time Sequencing (SMRT-SEQ) that allows direct observation of polymerase activity without amplification bias [20]. Rolling Circle Sequencing (ROLL-SEQ) applies similar principles to circular templates for high-fidelity variant detection. These techniques are particularly valuable for studying the mutation profiles of different reverse transcriptases, including those from HIV-1, HIV-2, and non-retroviral RTs like the thermostable group II intron RT (TGIRT) from Geobacillus stearothermophilus [20].

Data Management and Implementation Considerations

The implementation of NGS for viral resistance studies requires robust data management strategies to handle the substantial computational and storage challenges associated with genomic data. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study Viral NGS Database (SHCND) exemplifies an effective solution, addressing key issues in handling NGS data including high volumes of raw and processed data, storage solutions, application of sophisticated bioinformatic tools, high-performance computing resources, and reproducibility [21].

A dedicated NGS database should incorporate several key design elements: centralized storage of all NGS data with standardized metadata annotation, direct integration of bioinformatic pipelines for automated processing, version control for analysis protocols, and secure access mechanisms for researchers [21]. The SHCND, which includes NGS sequences from 5,178 unique people with HIV (PWH) as of 2025, has demonstrated its utility across multiple research projects on HIV pathogenesis, treatment, drug resistance, and molecular epidemiology [21]. This approach ensures data integrity, facilitates collaboration, and enables the integration of genomic data with clinical metadata for comprehensive analysis.

For laboratories establishing viral NGS capabilities, several practical considerations are essential. Data storage requirements can be substantial, with raw FASTQ files for a single sample typically ranging from 1-50 GB depending on the sequencing depth [23]. Compressed alignment files (BAM format) typically reduce storage needs by 30-50% compared to uncompressed files, while CRAM format can offer an additional 30-60% size reduction through reference-based compression [23]. Computational infrastructure must support the processing demands of alignment and variant calling, which often requires high-performance computing clusters or cloud-based solutions. Additionally, standardized operating procedures for data analysis, including specific versions of bioinformatic tools and reference genomes, are critical for ensuring reproducible results across different experiments and research groups.

Table 3: NGS Data Management and File Formats

| Data Type | Standard Format | Size Range | Primary Use | Tools for Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Reads | FASTQ | 1-50 GB | Store sequences with quality scores | FastQC, Trimmomatic, Cutadapt |

| Alignments | BAM | 30-50% smaller than FASTQ | Store mapped reads; enable visualization | SAMtools, BWA, Bowtie2, IGV |

| Alignment Index | BAI | Small | Enable random access to BAM files | SAMtools, Picard |

| Variants | VCF | Variable | Store mutation calls | BCFtools, GATK, SnpEff |

| Compressed Alignments | CRAM | 30-60% smaller than BAM | Long-term storage; data transfer | SAMtools |

Next-generation sequencing has fundamentally transformed our approach to understanding viral mutations and their relationship to treatment outcomes. The methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing NGS-based approaches to study viral resistance mechanisms. By integrating advanced sequencing technologies with robust bioinformatic analyses and proper data management practices, researchers can accurately identify resistance-associated mutations, characterize viral diversity, and elucidate the genetic basis of treatment failure.

The continued evolution of NGS technologies, including the emergence of long-read sequencing and improved single-molecule methods, promises to further enhance our ability to study viral populations with increasing resolution and accuracy. As these technologies become more accessible and standardized, their implementation in clinical and research settings will be crucial for advancing our understanding of viral evolution, optimizing treatment strategies, and ultimately improving patient outcomes in the face of rapidly evolving viral pathogens.

NGS in Action: Methodologies and Clinical Applications for Viral Mutation Detection

Within viral genomics research, targeted sequencing has become an indispensable methodology for focusing resources on specific genomic regions of interest, enabling deeper characterization of viral diversity and evolution. This approach is particularly critical for studying viral mutation rates, where capturing complete haplotypes and resolving complex variations is essential. Targeted sequencing allows researchers to bypass the unnecessary sequencing of entire viral or host genomes, concentrating instead on key genes or regions known to influence pathogenicity, immune evasion, or drug resistance [24]. Two powerful strategies for target enrichment—long-range PCR and amplicon-based sequencing—provide robust frameworks for generating high-quality viral genomic data, even from challenging sample types like clinical isolates and environmental wastewater [25] [26].

The application of these methods in virology addresses several inherent challenges of short-read sequencing, including limited ability to phase distantly separated variants and difficulties in analyzing regions with high sequence homology or complex repeats [27] [24]. Long-read sequencing technologies, such as those offered by Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and PacBio, when coupled with targeted enrichment, now enable researchers to obtain complete viral genomes with unambiguous haplotype resolution, providing deeper insights into viral quasispecies evolution and transmission dynamics [24] [28].

Long-Range PCR for Targeted Viral Sequencing

Principles and Workflow Optimization

Long-range PCR (LR-PCR) refers to the amplification of DNA targets over 5 kilobases (kb) in length, which typically cannot be amplified using routine PCR methods or reagents [29]. This technique is particularly valuable in viral genomics for generating large amplicons that span significant portions of viral genomes or entire smaller viral genomes in a single fragment. Successful LR-PCR traditionally employs a blend of DNA polymerases—typically a primary polymerase for fast elongation combined with a proofreading enzyme for accuracy [29]. The proofreading component repairs DNA mismatches incorporated at the 3' end of the growing strand, allowing the primary polymerase to continue elongation much further, resulting in successful amplification of long DNA fragments.

Recent methodological advances have optimized LR-PCR for integration with long-read sequencing platforms. A 2025 study established a robust, end-to-end workflow for phasing and localizing variants using LR-PCR and targeted Nanopore sequencing, demonstrating successful amplification of targets up to 22 kb with a 90% success rate using the UltraRun LongRange PCR Kit [27]. Critical optimization steps included careful primer design in unique sequence regions, adherence to manufacturer-recommended PCR programs with single annealing temperatures and extension times to enable processing of multiple samples simultaneously, and limitation of PCR cycles to 26 to minimize the generation of chimeric reads—a known PCR artifact where two different biological sequences combine, potentially affecting sequencing accuracy and phasing [27].

Application in Viral Research

LR-PCR has been successfully implemented in sequencing complex viral genomes, including Human Papillomavirus 16 (HPV16). A 2025 study developed a scalable HPV16 whole-genome sequencing approach using ONT's MinION and PromethION2 platforms that employed multiple primer set designs, including a near full-length primer set generating amplicons up to 7.7 kb to capture intact or nearly full-length HPV16 DNA [28]. This strategy enabled researchers to comprehensively analyze HPV16 genetic diversity among women in sub-Saharan African countries, generating complete HPV16 genomes at high coverage (median read coverage: 5,899–15,279×) and identifying all four previously defined HPV16 lineages (A–D) and their high-risk sublineages [28].

The method demonstrated sufficient sensitivity to amplify and sequence as few as five copies of HPV16 per reaction, making it particularly valuable for working with low-biomass clinical samples often encountered in viral research [28]. The successful application of this LR-PCR approach in resource-limited settings highlights its potential for decentralizing genomic surveillance and enabling in-country sequencing capabilities in regions most affected by viral pathogens.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Optimized Long-Range PCR in Viral Sequencing Applications

| Parameter | Performance Metric | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Success Rate | 90% for amplification up to 22 kb | Human genomic DNA amplification [27] |

| Chimeric Read Rate | Median 2.80% (range 1.79–16.12%) | Under optimized conditions [27] |

| Variant Phasing Concordance | 100% for SNV pairs and small InDels | Inter-variant distances 5.8–21.4 kb [27] |

| Sensitivity | As few as 5 HPV16 copies per reaction | CaSki cell line DNA [28] |

| Coverage Depth | Median 5,899–15,279× | HPV16 clinical samples [28] |

Experimental Protocol: Long-Range PCR for Viral Genome Amplification

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Begin with viral propagation in appropriate cell lines (e.g., Vero E6 cells for TOSV) or clinical samples (cervical exfoliated cells for HPV16) [30] [28].

- Extract nucleic acids using commercial kits (e.g., QIAsymphony with "Virus Pathogens DSP Midi Kit" for RNA viruses), eluting in 60 μL volume [25].

- For DNA viruses, use proteinase K digestion followed by column-based purification.

- Quantify extracted nucleic acids using fluorometric methods and assess quality via spectrophotometric ratios (A260/280 ≈ 1.8-2.0).

Primer Design

- Design primers targeting conserved regions of viral genomes using alignment software (MAFFT v7.525) and specialized primer design tools (FastPCR software) [25] [30].

- For comprehensive genome coverage, design multiple overlapping amplicons (e.g., three amplicons of 4961 bp, 6378 bp, and 4860 bp for RSV-A) [25].

- Incorporate degenerate bases at variable positions to enhance binding efficacy across diverse viral strains [30].

- Verify primer specificity using BLAST analysis against relevant databases.

Long-Range PCR Amplification

- Select appropriate LR-PCR kit (e.g., UltraRun LongRange PCR Kit, Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix) based on target length [27] [25].

- Prepare 20-50 μL reactions containing 1X PCR master mix, 0.5 μM each forward and reverse primer, and 150 ng DNA or 10 μL RNA (for reverse transcription PCR) [27] [25].

- Use the following thermocycling conditions for DNA amplification:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 26 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing: 60-68°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 1 minute per kb (adjust based on target length)

- Final extension: 68°C for 5-10 minutes

- For RNA viruses, include initial reverse transcription step (50°C for 10-30 minutes) using systems like SuperScript IV One-Step RT-PCR [25].

PCR Product Cleanup and Quantification

- Analyze amplicons using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent 4200 TapeStation System) [27].

- Define successful amplification as presence of clear band with concentration >2 ng/μL without significant non-specific products.

- Purify amplicons using bead-based cleanups (e.g., AMPure XP beads) if necessary.

- Quantify using fluorometric methods and normalize concentrations for library preparation.

Amplicon-Based Sequencing Strategies

Tiled Amplicon Approaches for Viral Genome Sequencing

Amplicon-based sequencing utilizes polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to selectively amplify genetic regions of interest, with primers designed to bookend target regions so the resulting amplicons can be specifically sequenced [24]. While simple and cost-effective, this approach has been significantly enhanced through tiling strategies that amplify overlapping fragments spanning entire viral genomes. This method has become particularly valuable for viral surveillance, enabling comprehensive genomic characterization even from low-concentration samples.

A novel targeted tiled amplicon-based sequencing protocol developed for sequencing the Hemagglutinin (HA) gene segment of seasonal influenza A and B viruses from wastewater demonstrates the power of this approach for public health surveillance [26]. The method uses short tiled amplicons (<250 bp in length) to successfully capture the HA gene segment, achieving consistent coverage across the gene in samples with influenza viral target digital PCR detections of at least 10³ copies/L [26]. This sensitivity threshold makes it possible to monitor viral evolution and detect low-frequency single nucleotide variants (SNVs) at high depth of coverage, providing insights into the diversity of circulating influenza viruses at the community level.

Similarly, an improved high-throughput amplicon-based whole-genome sequencing assay for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) was designed with three distinct amplicons covering the entire ~15.2 kb RSV genome [25]. This protocol achieved success in approximately 95% of samples with relatively low viral load (typically corresponding to cycle of quantification values of 27-32) and produced exceptionally high median depth of coverage (over 12,000×) with more than 1×10ⶠmapped reads [25]. Sequences passing quality filters showed coverage of at least 98% across the entire genome, enabling robust phylogenetic analysis and detection of emerging variants.

Implementation for Viral Surveillance

The development of a novel amplicon-based whole-genome sequencing framework for Toscana virus (TOSV) showcases the adaptability of this approach for emerging viral threats [30]. Researchers designed 45 oligonucleotide primer pairs based on TOSV lineage A reference sequences, generating 26 primer pairs for segment L, 13 for segment M, and 6 for segment S capable of amplifying overlapping sequences spanning the entire TOSV genome [30]. Strategic incorporation of degenerate bases in the primers enhanced sensitivity by maximizing binding efficacy to multiple strains, mitigating the risk of amplification failure across diverse viral isolates.

Sensitivity testing of this TOSV amplicon sequencing method demonstrated robust performance at viral RNA concentrations above 10² copies/μL, with coverage exceeding 96% across all genomic segments [30]. At higher concentrations (10³-10ⴠcopies/μL), the method achieved nearly complete genome recovery with consensus lengths consistently full-length for all segments, suggesting excellent assembly and comprehensive genomic characterization [30]. This performance highlights the utility of amplicon-based approaches for building genomic databases for understudied pathogens, enabling large-scale studies of genetic diversity and evolutionary dynamics critical for improving diagnostics and public health strategies.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Amplicon-Based Sequencing for Viral Surveillance

| Virus | Amplicon Strategy | Sensitivity | Coverage | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A/B | Short tiled amplicons (<250 bp) | 10³ copies/L | Consistent coverage across HA gene | Wastewater surveillance [26] |

| RSV | Three amplicons (4.9-6.4 kb) | Cq ≤32 (≥10³.ⵠRNA copies/mL) | ≥98% full genome | Clinical samples [25] |

| TOSV | 45 primer pairs (tiled) | >10² copies/μL | >96% (all segments) | Viral propagates, clinical samples [30] |

| HPV16 | Full-length + tiling primers | 5 copies/reaction | 5,899-15,279× median depth | Clinical isolates, cell lines [28] |

Experimental Protocol: Tiled Amplicon Sequencing for Viral Genomes

Primer Design and Validation

- Retrieve complete genome sequences of target virus from public databases (e.g., Nextstrain) representing recent circulating strains [25].

- Align sequences using MAFFT v7.525 or similar alignment software to identify conserved regions [25] [30].

- Design primer pairs to generate overlapping amplicons of 400-500 bp for short-read platforms or 2-7 kb for long-read platforms [30] [28].

- Incorporate degenerate bases at polymorphic positions to enhance coverage across diverse strains [30].

- Validate primer specificity in silico using BLAST and evaluate efficiency with FastPCR software [25].

- Conduct phylo-primer-mismatch analysis by mapping primer sequences against strain alignment to visualize mismatches across phylogenetic tree [25].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- For RNA viruses: perform reverse transcription using SuperScript IV One-Step RT-PCR System or equivalent [25].

- Amplify viral genome in multiple separate RT-PCR/PCR reactions (e.g., 3 reactions for RSV covering different genome segments) [25].

- Use 50 μL reactions containing 10 μL total RNA, appropriate primer concentrations (typically 0.5 μM final concentration), and master mix [25].

- Pool PCR products in equimolar ratios after quantification and quality assessment.

- Proceed with library preparation using platform-specific kits:

- Sequence on appropriate platform (Illumina for short-read, GridION/PromethION for long-read).

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Perform basecalling and demultiplexing using platform-specific tools (e.g., MinKNOW/dorado for Nanopore) [27].

- Align reads to reference genome using Minimap2 (long-read) or BWA (short-read) [27] [28].

- For amplicon-based data: implement primer trimming and consider amplicon-aware alignment.

- Conduct variant calling using appropriate tools:

- Generate consensus sequences and perform phylogenetic analysis for lineage assignment.

Successful implementation of long-range PCR and amplicon-based sequencing strategies requires careful selection of molecular biology reagents, sequencing kits, and bioinformatic tools. The following table summarizes key solutions utilized in the protocols cited in this application note.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Viral Targeted Sequencing

| Category | Specific Product/Kits | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LR-PCR Kits | UltraRun LongRange PCR Kit (Qiagen) | Amplification of long targets (up to 22 kb) | 90% success rate for long targets [27] |

| Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen) | High-fidelity amplification of complex templates | Proofreading activity, high processivity [27] | |

| LongAmp Taq 2X Master Mix (NEB) | Robust amplification of GC-rich targets | Blended polymerase system [27] | |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | SuperScript IV One-Step RT-PCR System | Whole-genome amplification of RNA viruses | High sensitivity, high fidelity [25] |

| Sequencing Kits | Ligation Sequencing Kit V14 (SQK-LSK114, ONT) | Library preparation for Nanopore sequencing | Compatible with native barcoding [27] |

| Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24, ONT) | Multiplexing samples on Flongle/GridION | Enables up to 8-plex per flow cell [27] | |

| Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (iMAP) | Amplicon sequencing on Illumina platforms | Optimized for tiled amplicon workflows [30] | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Clair3 | Variant calling from long-read data | Combines pileup and full-alignment approaches [27] [28] |

| PEPPER-Margin-DeepVariant | Variant calling pipeline | Full-alignment method for high precision [28] | |

| WhatsHap, HapCUT2 | Phasing of genetic variants | Resolves haplotypes from long-read data [27] | |

| Minimap2 | Alignment of long reads to reference | Fast and accurate for noisy long reads [27] |

Long-range PCR and amplicon-based sequencing strategies represent powerful approaches for targeted viral sequencing, each with distinct advantages for different research contexts. LR-PCR excels in generating long amplicons that span complex genomic regions or entire viral genomes, enabling comprehensive haplotype resolution and characterization of structural variations [27] [28]. Tiled amplicon approaches provide exceptional depth of coverage across target regions, making them ideal for detecting low-frequency variants and working with challenging sample types like wastewater and low-viral-load clinical specimens [25] [26].

The integration of these targeted enrichment methods with third-generation sequencing platforms has dramatically improved our ability to study viral mutation rates and evolution. By providing complete viral haplotypes and resolving complex genomic regions that were previously intractable to short-read sequencing, these approaches enable researchers to track viral transmission pathways, identify emerging variants of concern, and understand the molecular mechanisms driving viral evolution. As these methodologies continue to mature and become more accessible, they promise to further democratize viral genomic surveillance, enabling researchers worldwide to contribute to our collective understanding of viral dynamics and evolution.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the management of viral infections in immunocompromised patients, enabling high-resolution detection of antiviral resistance mutations. For Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the emergence of drug-resistant strains poses a significant challenge to successful long-term therapy [31] [32]. NGS surpasses traditional Sanger sequencing by detecting minority variants present at frequencies as low as 1-5%, providing an early warning system for emerging resistance and allowing for more informed clinical decision-making [31] [32] [10]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for implementing NGS-based antiviral resistance monitoring for HCMV and HIV within a clinical research context.

Recent surveillance data highlights the prevalence and trends of antiviral resistance in HCMV and HIV, underscoring the need for continuous monitoring.

Table 1: Documented Resistance Mutations and Their Frequencies

| Virus | Gene/Region | Key Resistance Mutations | Associated Antiviral(s) | Reported Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCMV | UL97 | Various (e.g., G579C) [33] | (Val)ganciclovir, Maribavir [31] | Found in 25% of patients with novel mutations [33] |

| UL54 | Various (e.g., A835T, P522S) [33] | Ganciclovir, Cidofovir, Foscarnet [31] | Found in 25% of patients with novel mutations [33] | |

| UL56 / UL89 | Various [31] | Letermovir [31] | Not specified | |

| HIV | Reverse Transcriptase | K65R, M184I/V [34] | Tenofovir, Emtricitabine/Lamivudine [34] | 22% in seroconversions on PrEP [34] |

| Integrase | R263K [35] | Dolutegravir, Bictegravir [35] | Increasing prevalence [35] | |

| Protease | Multiple major mutations [35] | Protease Inhibitors | 2.1% (in HIV DNA, 2024) [35] |

Table 2: HIV Drug Resistance Trends Over Time (2018-2024) [35]

| Resistance Category | Prevalence in HIV RNA (2018) | Prevalence in HIV RNA (2024) | Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Drug Resistance | ~30% | ~25% | â–¼ Declining |

| NRTI + NNRTI Resistance | 6.1% | 3.5% | â–¼ Declining |

| Dual NRTI + INSTI Resistance | 8.7% | 4.7% | â–¼ Declining |

| Protease Inhibitor Resistance | <3% | <3% | â–º Stable |

Experimental Protocols for NGS-Based Resistance Detection

NGS Protocol for HCMV Antiviral Resistance

This protocol is adapted from a validated procedure for sequencing HCMV genes associated with antiviral resistance [31].

1. Primer Design and Multiplex PCR Setup:

- Design: Design primers to generate 400-800 bp amplicons covering full coding sequences of target genes (UL27, UL54, UL55, UL56, UL89, UL97) using the HCMV Merlin strain (NC_006273.2) as a reference. Utilize tools like Primal Scheme and refine with multiple sequence alignment to ensure coverage of genetic diversity [31].

- Multiplexing: Group primer sets into three multiplex pools to avoid dimerization [31].

- PCR Master Mix:

- Primer Pool (final concentration 0.08-0.1 µM)

- 1x Q5 Reaction Buffer

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- <10 ng viral DNA template

- 0.02 U/µL Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase

- 1x Q5 High GC Enhancer

- Nuclease-free water to 25 µL [31].

- Thermocycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 15 min.

- 35 Cycles: 95°C for 15 s, 62°C for 5 min.

- Final Extension: 62°C for 5 min.

- Hold at 4°C [31].

2. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Purify the multiplex PCR products.

- Prepare sequencing libraries using the Illumina Nextera XT kit.

- Sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform with a minimum of 100,000 reads per sample to ensure adequate depth for variant calling [31].

3. Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Use FastQC to assess raw read quality.

- Alignment: Map reads to the HCMV reference genome (NC_006273.2) using BWA or similar aligner.

- Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels using tools like GATK. The limit of detection for minority variants is ~5% [31].

- Interpretation: Compare identified amino acid substitutions to published databases (e.g., CHARMD, HerpesDRG) to classify mutations as confirmed resistance-associated, polymorphic, or novel [33].

Hybrid NGS Protocol for HIV-2 Drug Resistance

This protocol details a hybrid NGS approach for HIV-2, which is inherently resistant to some antiretrovirals [36].

1. Sample Preparation and Amplification:

- Extract viral RNA from plasma samples.

- Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA.

- Amplify the protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase regions of the HIV-2 pol gene using a one-touch PCR approach.

2. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries from the amplified cDNA.

- Sequence the libraries using an Ion Torrent platform (e.g., GeneStudio S5) [36].

3. Data Analysis and Validation:

- Analysis: Use the Torrent Suite and Ion Reporter software for base calling, alignment, and variant identification.

- Validation: The protocol demonstrated 92% amplification success for protease, 91% for reverse transcriptase, and 49% for integrase in a cohort of 100 samples. It showed strong agreement with Sanger sequencing while additionally detecting minority variants like K70E and M184V that Sanger missed [36].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized NGS workflow for antiviral resistance profiling, applicable to both HCMV and HIV with target-specific modifications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of NGS for antiviral resistance monitoring requires a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Category | Item | Specific Example / Function | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) | Accurate amplification of target viral genes for sequencing [31]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Illumina Nextera XT; Ion Chef System | Prepares amplified DNA for sequencing on the respective platform [31] [37]. | |

| Targeted Amplicon Panel | Custom-designed multiplex primer pools | Enriches specific viral genes (e.g., UL54, UL97 for HCMV; pol for HIV) [31] [37]. | |

| Platform & Sequencing | NGS Sequencer | Illumina MiSeq; Ion Torrent S5 | Generates high-throughput sequence data [31] [36]. |

| Bioinformatics | Primary Analysis Software | Torrent Suite (Ion Torrent); Illumina DRAGEN | Performs base calling, quality control, and initial alignment [37]. |

| Secondary Analysis & Interpretation | Stanford HIVdb; In-house HCMV pipelines | Annotates variants and interprets drug resistance from sequence data [32] [38]. | |

| Data Visualization | MultiQC; Custom scripts | Provides QC overview and visualization of results [38]. | |

| Corilagin (Standard) | Corilagin (Standard), CAS:23094-69-1, MF:C27H22O18, MW:634.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Demethylsuberosin | Demethylsuberosin, CAS:21422-04-8, MF:C14H14O3, MW:230.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |