Directed Evolution in Biotechnology: Methodologies, Applications, and Future Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of directed evolution, a powerful protein engineering tool that mimics natural selection to optimize biomolecules for biotechnological and therapeutic applications.

Directed Evolution in Biotechnology: Methodologies, Applications, and Future Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of directed evolution, a powerful protein engineering tool that mimics natural selection to optimize biomolecules for biotechnological and therapeutic applications. It covers foundational principles, from classical methods like error-prone PCR to cutting-edge techniques such as machine learning-assisted evolution and in vivo base-editing platforms. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content delves into practical methodologies for engineering enzymes, antibodies, and degron systems, addresses common experimental challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a comparative analysis of different technologies. The review synthesizes key takeaways and discusses future directions, including the potential of directed evolution to create novel therapeutics and biocatalysts.

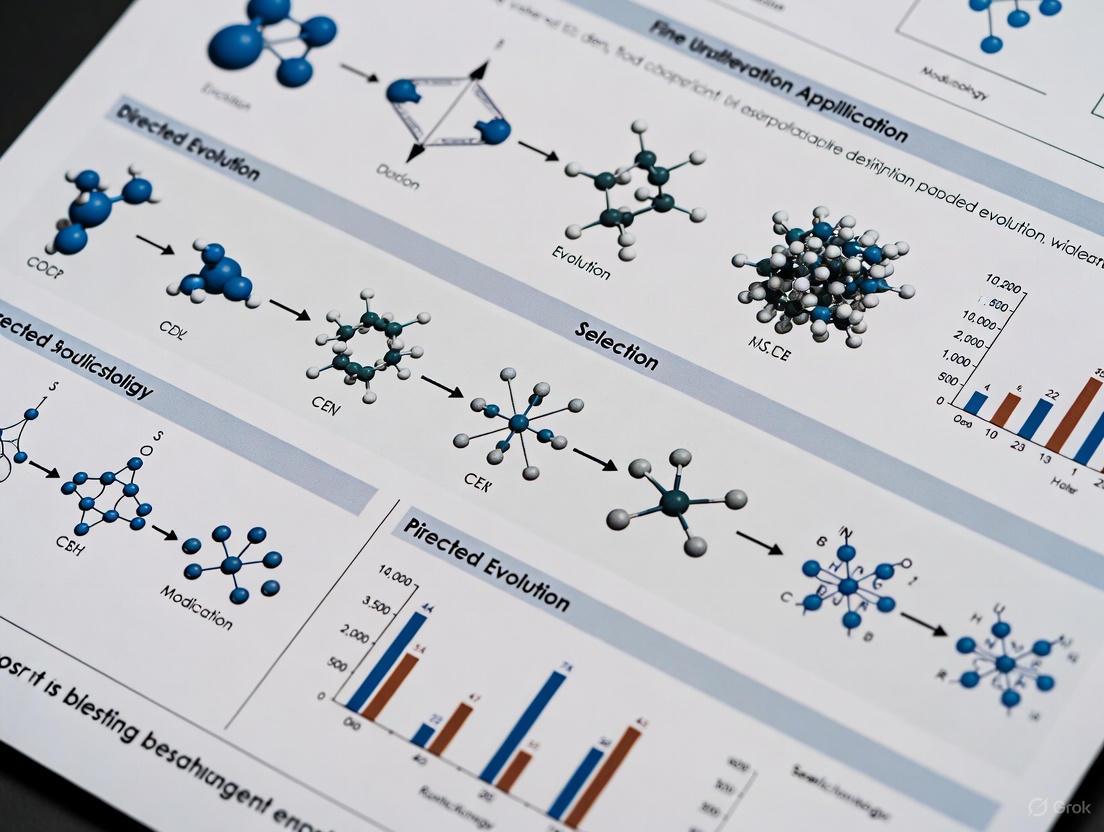

The Principles and Power of Directed Evolution

1. Introduction

Directed evolution is a powerful protein engineering technique that mimics the process of natural selection in a laboratory setting to optimize biomolecules for desired properties [1] [2]. This method involves iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening to navigate vast sequence spaces, isolating variants with enhanced functions such as catalytic activity, stability, or binding affinity [3]. For researchers in biotechnology and drug development, directed evolution has become an indispensable tool for generating novel enzymes, therapeutic proteins, and biosensors that are difficult to design through rational methods alone [4] [2]. The following application notes and protocols detail contemporary methodologies, with a focus on machine learning-integrated approaches that are reshaping the efficiency and scope of protein engineering campaigns.

2. Core Principles and Recent Methodological Advances

Traditional directed evolution operates as a greedy hill-climbing algorithm on the protein fitness landscape, which can be inefficient when mutations exhibit non-additive, or epistatic, behavior, often leading to convergence on local optima [1]. Recent advances have integrated machine learning (ML) to overcome these limitations, creating adaptive, intelligent search strategies. The table below summarizes and compares several state-of-the-art ML-assisted directed evolution frameworks.

Table 1: Advanced Machine Learning Frameworks for Directed Evolution

| Framework Name | Core Innovation | Reported Performance | Key Application/Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALDE (Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution) [1] | Iterative Bayesian optimization leveraging uncertainty quantification to balance exploration and exploitation. | Improved product yield from 12% to 93% in 3 rounds for a challenging epistatic system. | Optimization of five epistatic residues in ParPgb for a cyclopropanation reaction. |

| CLADE (Cluster Learning-assisted Directed Evolution) [5] | Hierarchical unsupervised clustering sampling to generate diverse training sets for supervised learning. | Achieved global maximal fitness hit rates of 91.0% (GB1 dataset) and 34.0% (PhoQ dataset). | Screening of a four-site combinatorial library, sequentially testing 480 out of 160,000 sequences. |

| ODBO [6] | Bayesian optimization enhanced with a novel low-dimensional sequence encoding and search space prescreening via outlier detection. | Effectively found variants with properties of interest in four protein directed evolution experiments. | A general framework designed to reduce experimental cost and time for a broad range of problems. |

| PROTEUS [7] | A biological AI system that performs directed evolution directly in mammalian cells for developing research tools or gene therapies. | Successfully evolved improved versions of proteins and nanobodies functionally tuned for mammalian environments. | Developed drug-regulatable proteins and DNA-damage-detecting nanobodies directly in human cells. |

| Computational DE (EnzyHTP) [3] | A computational directed evolution protocol using adaptive resource allocation for high-throughput virtual screening based on stability and catalytic activity. | Identified all four experimentally-observed beneficial mutants for Kemp eliminase; completed 18.4 μs of MD and 18,400 QM calculations in 3 days. | Virtual screening for Kemp eliminase (KE07) variants using folding stability and electrostatic stabilization energy as computational readouts. |

3. Experimental Protocol: ALDE for Optimizing an Epistatic Enzyme Active Site

The following protocol is adapted from the ALDE workflow used to optimize the active site of a protoglobin (ParPgb) for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction [1].

3.1. Define Objective and Design Space

- Objective: Explicitly define the fitness metric. In the cited study, the objective was the difference between the yield of the cis cyclopropanation product and the trans product (cis yield - trans yield).

- Design Space: Select k residues suspected of influencing the function. The study selected five epistatic active-site residues (W56, Y57, L59, Q60, F89), creating a theoretical design space of 20^5 (3.2 million) variants.

3.2. Initial Library Construction and Screening

- Method: Simultaneously mutate all k residues using PCR-based mutagenesis with NNK degenerate codons to maximize sequence diversity.

- Screening: Synthesize and screen an initial library of variants (e.g., hundreds of clones) using a relevant wet-lab assay (e.g., gas chromatography for product yield and selectivity).

- Output: The result is an initial dataset of sequence-fitness pairs (e.g., SequenceVariant1 -> Fitness_1).

3.3. Computational Model Training and Variant Proposal

- Encoding: Convert the protein sequence data into a numerical representation (e.g., one-hot encoding, embeddings from protein language models).

- Model Training: Train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., a model capable of uncertainty estimation like Gaussian Process Regression) on the collected sequence-fitness data to learn the mapping.

- Acquisition Function: Apply an acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound, Expected Improvement) to the trained model to rank all ~3.2 million sequences in the design space. This function balances the exploitation of predicted high-fitness sequences with the exploration of sequences where the model is uncertain.

- Proposal: Select the top N (e.g., 50-200) ranked sequences for the next experimental round.

3.4. Iterative Evolution and Final Isolation

- Loop: The proposed sequences are synthesized and assayed in the wet lab. The new data is added to the growing dataset, and the cycle (Steps 3.3 and 3.4) repeats.

- Termination: The process continues for a set number of rounds or until a fitness threshold is met (e.g., >90% yield of the desired product). The best-performing variant from the final round is isolated and characterized.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below catalogs key reagents and materials essential for executing a directed evolution campaign, particularly one based on the ALDE protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Directed Evolution

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Template | The gene or protein to be engineered. Provides the starting sequence and known function. | A gene encoding a protoglobin (e.g., ParPgb) [1] or Kemp eliminase (KE07) [3]. |

| Mutagenesis Reagents | To introduce genetic diversity into the parent template. | PCR reagents, NNK degenerate codons, or specialized kits for site-saturation mutagenesis [1]. |

| Expression System | A cellular host for producing the protein variants. | E. coli cells, or mammalian cells (e.g., for the PROTEUS system) [7]. |

| Screening Assay Reagents | To quantitatively measure the fitness of each variant. | Substrates (e.g., 4-vinylanisole, ethyl diazoacetate), buffers, and detection instruments (e.g., GC-MS, plate readers) [1]. |

| ML/Computational Software | To train models, predict fitness, and propose new variants. | Custom Python codebases (e.g., ALDE GitHub repo), EnzyHTP software for computational screening [1] [3]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | To power computationally intensive simulations and model training. | Clusters with ~30 GPUs and ~1000 CPUs for molecular dynamics and QM calculations in virtual screening [3]. |

5. Comparative Workflow: Traditional DE vs. ML-Assisted DE

The fundamental shift from traditional to modern directed evolution is best understood by comparing their core operational workflows, as illustrated in the following diagram.

6. Conclusion

Directed evolution has matured from a brute-force screening technique into a sophisticated discipline integrating computational intelligence and high-throughput biology. Frameworks like ALDE, CLADE, and PROTEUS demonstrate that leveraging machine learning and adaptive experimental design is no longer optional but essential for efficiently tackling complex protein engineering challenges, especially those involving significant epistasis [1] [5] [7]. For drug development professionals, these methods unlock the potential to rapidly engineer highly specific biologics, biocatalysts for green chemistry, and novel therapeutic modalities, directly accelerating the pace of biotechnological innovation [4] [2].

The field of directed evolution, a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, traces its conceptual origins to a seminal series of 1960s experiments that demonstrated Darwinian principles at the molecular level. Spiegelman's Monster represents the first experimental demonstration of evolution operating on molecular replicators outside of a cellular context, providing a foundational model for all subsequent in vitro evolution technologies [8] [9]. This revolutionary experiment proved that RNA molecules subjected to selective pressure in a test tube would evolve toward optimized replicative efficiency, shedding unnecessary genomic information in favor of minimal sequences capable of rapid reproduction [8]. The methodology established a fundamental paradigm: iterative rounds of replication, selection, and amplification could steer biomolecules toward desired functional traits.

This application note contextualizes these historical foundations within modern directed evolution frameworks, highlighting how Spiegelman's basic principles have been refined into sophisticated protocols for engineering proteins and nucleic acids. We detail specific methodologies that have enabled researchers to evolve biomolecules with novel functions, emphasizing practical protocols for laboratory implementation. The transition from evolving simple RNA replicators to engineering complex protein therapeutics demonstrates how core evolutionary principles have been adapted to address increasingly ambitious biotechnological challenges, particularly in drug development where engineered proteins now enable therapeutic strategies once considered impossible [10] [11].

Historical Foundation: Spiegelman's Monster

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The original Spiegelman experiment utilized a remarkably simple yet powerful experimental setup that continues to inform modern directed evolution approaches [8]:

- Initial Template: RNA from bacteriophage Qβ, approximately 4,500 nucleotides in length.

- Replication System: Qβ RNA-dependent RNA replicase, free nucleotides, and essential salts.

- Evolutionary Pressure: Serial transfer of replicated RNA to fresh solution tubes containing replication components.

- Selection Mechanism: Faster-replicating RNA variants outcompeted slower-replicating ones in each transfer.

After 74 serial transfers spanning multiple generations, the original RNA genome evolved into a minimal replicator of only 218 nucleotides—dubbed "Spiegelman's Monster"—that replicated with maximum efficiency under the experimental conditions [8]. This dwarf genome retained only the essential sequences required for replicase recognition, jettisoning all genes unnecessary for replication in this simplified environment.

Quantitative Evolution of RNA Genomes

Table 1: Genomic Reduction in Spiegelman's Experiment

| Generation | Nucleotide Length | Replication Efficiency | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (Qβ virus) | ~4,500 nucleotides | Baseline | Complete viral genome |

| Intermediate | ~500-1,000 nucleotides | Increased | Loss of structural genes |

| Final (74 transfers) | 218 nucleotides | Maximized for conditions | Minimal replicase binding site |

Subsequent research confirmed and extended these findings. Sumper and Luce demonstrated that under appropriate conditions, Qβ replicase could spontaneously generate self-replicating RNA de novo without initial template [8]. Eigen later produced even more degraded systems of just 48-54 nucleotides—the absolute minimum required for replicase binding [8]. These findings established that Darwinian evolution requires only a self-replicating molecule subject to selection pressure, providing experimental support for the "RNA world" hypothesis of life's origins.

Modern Extensions: Evolving Molecular Ecosystems

Recent research has dramatically expanded on Spiegelman's original work. A Japanese team led by Ichihashi and Mizuuchi conducted long-term evolution experiments demonstrating that a single RNA replicator could evolve into complex molecular ecosystems [9]. After 600 hours and 120 replication rounds, the original RNA diversified into five distinct molecular "species" or lineages comprising both host RNAs (encoding replicases) and parasitic RNAs (hijacking replication machinery) [9].

Table 2: Emergent Molecular Diversity in Extended Evolution Experiments

| Lineage Type | Number Evolved | Functional Role | Evolutionary Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host | 3 lineages | Encodes functional replicase | Developed interference mutations against parasites |

| Parasite | 2 lineages | Hijacks host replication machinery | Developed defensive mutations |

| Super-cooperator | 1 host lineage | Could replicate all lineages | Emerged by round 228, enabling network stability |

This molecular ecosystem demonstrated sophisticated ecological dynamics including arms races, coevolution, and eventually stabilization through cooperative networks [9]. By round 190, population fluctuations gave way to smaller waves, suggesting the lineages had established quasi-stable coexistence—a phenomenon termed "survival of the flattest" where networks of cooperators outperform individual replicators [9].

Figure 1: Emergence of Molecular Ecosystems from a Single Replicator

Modern Directed Evolution Platforms

Key Technological Platforms

Contemporary directed evolution employs sophisticated display technologies that overcome the library size limitations of early methods. These platforms enable screening of vastly larger molecular diversity (up to 1015 variants) compared to cell-based systems (typically limited to 106-107 variants by transformation efficiency) [12] [13].

Table 3: Comparison of Modern Directed Evolution Platforms

| Platform | Library Size | Genotype-Phenotype Link | Key Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIS Display | >1012 | DNA-based via RepA protein [12] | DNA-binding proteins, transcription factors [12] | Fully in vitro, no transformation needed [12] |

| Yeast Display | ~107 | Cell surface expression [14] | Antibody engineering, protein-DNA interactions [14] | Supports eukaryotic processing; limited library size [13] |

| mRNA Display | ~1012 | Puromycin linkage [13] | Peptide optimization, protein-binding partners [13] | Fully in vitro; fragile RNA complexes [13] |

| Phage Display | ~107-109 | Viral coat protein fusion [13] | Antibody engineering, protein-protein interactions [13] | Robust; limited by bacterial transformation [13] |

CIS Display Protocol for Engineering DNA-Binding Proteins

CIS display represents a particularly powerful DNA-based in vitro platform that overcomes the library size limitations of cell-based systems [12]. The following protocol details its application for evolving minimal transcription factors:

DNA Template and Target Preparation

Construct Design: Prepare CIS display constructs containing:

- Ptac promoter for in vitro transcription

- Gene of interest (e.g., Cro transcription factor)

- RepA replication initiator protein

- CIS-origin sequence for genotype-phenotype linkage [12]

Template Amplification: Amplify constructs using KOD hot-start polymerase with:

- 3 μL of 10 μM each primer

- 4 μL of 25 mM MgSO4

- 5 μL of 2 mM each dNTP

- 5 μL of 10× buffer

- 1 ng template DNA

- 1U polymerase

- Nuclease-free water to 50 μL [12]

PCR Protocol:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 25-35 cycles: 95°C for 20s, 65°C for 30s, 70°C for 50s

- Final extension: 70°C for 2 minutes [12]

Target DNA Preparation: Anneal biotinylated target DNA sequences by:

- Combining 5 μL of 100 μM each primer with 40 μL annealing buffer

- Heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, then slow cooling to 50°C (-1°C/cycle, 1 minute per cycle) [12]

In Vitro Transcription and Translation

Template Mixture: Dilute DNA template of interest (e.g., Ptac-Cro-RepA-CIS-ori) with non-binding control (e.g., Ptac-GFP-RepA-CIS-ori) at 1:109 ratio to mimic selection from diverse library [12].

Translation Reaction: Add 3-4 μg mixed DNA templates to E. coli S30 extract for coupled transcription/translation according to manufacturer protocols [12].

Affinity Selection and Amplification

Streptavidin Bead Preparation:

- Wash Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin with PBS pH 7.4

- Block with 2% BSA, 0.1 mg/mL herring sperm DNA in PBS [12]

Binding Reaction: Incubate translated CIS display complexes with biotinylated target DNA immobilized on streptavidin beads for 1 hour with rotation.

Washing: Remove non-specific binders with 0.1-1% Tween-20 in PBS washing buffer.

Elution and Amplification: Recover bound complexes by PCR amplification of bead-bound DNA for subsequent rounds of selection.

Iterative Selection: Typically 3-7 rounds of selection with increasing stringency are required to enrich functional binders from >109-fold excess of non-functional variants [12].

Figure 2: CIS Display Workflow for Directed Evolution

Case Study: Engineering RNA-Conjugating Enzymes via Yeast Display

A recent breakthrough application of directed evolution created a covalent RNA-protein conjugation system by engineering the HUH tag enzyme [14]. This case study exemplifies the modern directed evolution workflow:

Experimental Evolution Protocol

Library Construction:

- Subject wild-type HUH tag (specific for single-stranded DNA) to error-prone PCR

- Generate library of ~1.2×108 variants with 1-2.3 amino acid changes per gene [14]

Yeast Display Evolution:

- Express HUH variants on yeast surface as Aga2p fusions

- Initially select with DNA-RNA hybrid probes (r9 hybrid) at 2 μM concentration

- Progressively transition to pure RNA probes over 7 generations [14]

Selection Pressure Modulation:

- Generations 1-2: Use hybrid RNA-DNA probes

- Generation 3: Transition to r11 hybrid with only 2 DNA nucleotides

- Generations 4-7: Use pure RNA probe while decreasing concentration from 500 nM to 1 nM

- Generation 5: Replace Mn2+ with Mg2+ for physiological relevance [14]

Screening and Isolation:

- Label yeast cells with biotinylated RNA probe

- Stain with streptavidin-PE and anti-myc antibody

- Isolate highest-binding population by FACS

- Sequence enriched variants and characterize kinetics [14]

Quantitative Outcomes

The directed evolution campaign generated rHUH, a 13.4 kD protein with 12 mutations relative to wild-type HUH tag [14]. The evolved enzyme achieved:

- Covalent conjugation to 10-nucleotide RNA recognition sequence within minutes

- Operational sensitivity down to 1 nM target RNA

- Shifted metal ion requirement from Mn2+ to Mg2+

- Efficient labeling in mammalian cell lysate [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Directed Evolution Protocols

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Protocol Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Systems | KOD hot-start, Q5 High-Fidelity | Library construction, amplification | CIS display, mutagenesis [12] |

| In Vitro Translation | E. coli S30 extract | Protein synthesis without cells | CIS display, ribosome display [12] |

| Display Scaffolds | Aga2p yeast display, RepA CIS display | Genotype-phenotype linkage | Yeast surface display, CIS display [12] [14] |

| Selection Reagents | Streptavidin magnetic beads, biotinylated probes | Target binding and isolation | Affinity selection across platforms [12] [14] |

| Cell Lines | Saccharomyces cerevisiae EBY100 | Eukaryotic protein expression | Yeast surface display [14] |

| Detection Reagents | Streptavidin-PE, anti-myc antibodies | FACS detection and sorting | Screening and quantification [14] |

| Acid red 426 | Acid red 426, CAS:118548-20-2, MF:C5H5FN2O | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sulphur Blue 11 | Sulphur Blue 11, CAS:1326-98-3, MF:C22H21NO | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

AI-Driven Transformation of Protein Engineering

The convergence of directed evolution with artificial intelligence represents the most significant recent advancement in the field. AI systems are now capable of designing de novo proteins with optimized structures, functions, and therapeutic properties that nature never evolved [10].

Key AI Technologies and Applications

RFdiffusion: Applies diffusion models to generate novel proteins, including enzymes, binders, and scaffolds with high stability and target specificity [10].

VibeGen: Introduces a dual-model framework to design proteins with specific dynamic properties, enabling engineering of proteins with tailored mechanical or allosteric behaviors [10].

AlphaFold2/3: While primarily a prediction tool, AlphaFold provides essential structural validation for AI-designed proteins and enables faster target validation [10].

These tools compress protein design cycles from years to days or weeks while creating proteins unconstrained by natural evolutionary history [10]. Companies like Generate Biomedicines are leveraging these capabilities to create next-generation therapeutics that are not only more effective but also more manufacturable and scalable than their natural counterparts [10].

The trajectory from Spiegelman's minimalist RNA replicators to contemporary AI-driven protein design illustrates how fundamental evolutionary principles have been harnessed and refined for biotechnological applications. The core paradigm remains consistent: generate diversity, apply selective pressure, and amplify successful variants. However, the methodologies have evolved from simple serial transfers of RNA in test tubes to sophisticated computational and display technologies that can explore vast regions of sequence space.

This progression demonstrates that historical experiments provide not merely historical context but conceptual frameworks that continue to inform cutting-edge research. Modern directed evolution protocols, whether employing cell-free display technologies or computational design, still operate on the fundamental principle established by Spiegelman: evolution can be directed toward useful goals when appropriate selective pressures are applied to diversifying molecular populations. As these technologies continue to advance, they enable increasingly ambitious applications in therapeutic development, synthetic biology, and fundamental research into the principles governing molecular evolution.

Directed evolution (DE) is a powerful protein engineering method that mimics the process of natural selection in a laboratory environment to steer proteins or nucleic acids toward a user-defined goal [13]. This method functions by harnessing natural evolution but on a significantly shorter timescale, enabling the rapid selection of biomolecule variants with properties that make them more suitable for specific applications in biotechnology and drug development [15]. The technique consists of subjecting a gene to iterative rounds of mutagenesis (creating a library of variants), selection (expressing those variants and isolating members with the desired function), and amplification [13]. The appeal of directed evolution lies in its conceptual straightforwardness and its proven ability to yield useful, and often unanticipated, solutions for tailoring protein properties such as thermal stability, enzyme selectivity, specific activity, and ligand binding [16].

The Iterative Cycle: Core Principles and Workflow

The fundamental algorithm of directed evolution is an iterative cycle of diversification and selection. This cycle mirrors natural evolution, requiring three key components: variation between replicators, fitness differences upon which selection acts, and heritability of that variation [13]. In practice, this translates to a core, repeatable workflow.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, iterative stages of a standard directed evolution experiment.

Key Stages of the Cycle

- Diversification: The first step involves generating a large library of genetic variants from a parent gene. This is achieved through various mutagenesis techniques, which can range from random methods that introduce point mutations across the entire sequence to more focused approaches that target specific regions [13] [15].

- Selection/Screening: The created library is then subjected to a process that identifies variants with the desired enhanced function. Selection directly couples protein function to the survival or physical isolation of the gene (e.g., binding to an immobilized target), while screening involves individually assaying each variant to quantitatively measure its activity against a set threshold [13].

- Amplification: The genes encoding the best-performing variants are isolated and amplified, for example, using PCR or by growing transformed host bacteria [13]. This amplified genetic material serves as the template for the next round of evolution, allowing for stepwise improvements over multiple generations [13].

Detailed Methodologies and Data

Library Creation: Diversification Strategies

Creating genetic diversity is the foundation of the diversification step. The choice of method depends on the available structural knowledge and the desired scope of exploration in the sequence space. The table below summarizes common genetic diversification techniques.

Table 1: Methodologies for Genetic Diversification in Directed Evolution

| Method | Purpose | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-prone PCR (epPCR) [15] [17] | Insertion of random point mutations across the whole sequence. | Easy to perform; does not require prior knowledge of key positions. | Reduced and biased sampling of mutagenesis space; genetic code redundancy. | Subtilisin E [15], Glycolyl-CoA carboxylase [15], Thermostable lipase [17] |

| DNA Shuffling [13] [17] | Random recombination of multiple parental sequences. | Recombines beneficial mutations; can jump into new regions of sequence space. | Requires high sequence homology (>70%) between parent genes. | Thymidine kinase [15], Non-canonical esterase [15], Thermostable lipase [17] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis [13] [15] | Focused mutagenesis of specific amino acid positions. | In-depth exploration of chosen positions; enables rational design of "smart" libraries. | Only a few positions are mutated; libraries can become very large. | Widely applied to enzyme engineering [15] |

| Sequence Saturation Mutagenesis (SeSaM) [17] | Insertion of random point mutations. | Overcomes biases of epPCR; generates diverse mutant libraries. | Requires multiple chemical and enzymatic steps. | Thermostable phytase [17] |

| RAISE [15] | Insertion of random short insertions and deletions (indels). | Enables random indels across the sequence. | Indels are limited to a few nucleotides; can introduce frameshifts. | β-Lactamase [15] |

| Orthogonal Replication Systems [15] | In vivo random mutagenesis. | Mutagenesis can be restricted to the target sequence. | Relatively low mutation frequency; target sequence size limitations. | β-Lactamase, Dihydrofolate reductase [15] |

Isolation of Variants: Selection and Screening Platforms

After creating a variant library, the challenge is to identify the rare, improved variants. The choice between selection and screening is critical and depends on the desired property and the available assay technology.

Table 2: Methods for Isolation of Variants in Directed Evolution

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage Display [13] [15] | Selection | Very High | Viruses display protein variants; selected via affinity binding. | Limited to binding properties (e.g., antibodies). |

| mRNA Display [13] [17] | Selection | Very High (~1013 sequences) | In vitro method; genotype-phenotype link via puromycin; large library diversity. | Compatible with unnatural amino acids and glycosylation [17]. |

| FACS-Based Screening [15] | Screening | Very High | Uses fluorescence-activated cell sorting. | Evolved property must be linked to a change in fluorescence. |

| In vivo Selection [13] | Selection | High (limited by transformation) | Couples protein function to cell survival (e.g., toxin resistance). | Difficult to engineer; prone to artifacts. |

| Colorimetric/Fluorimetric Screening [15] | Screening | Medium to High | Fast and easy to perform with colonies or cultures. | Limited to substrates/products with spectral properties. |

| Plate-Based Automated Assays [15] | Screening | Medium | Automation increases throughput; can be coupled to GC/HPLC. | Throughput is limited compared to other methods. |

Advanced Protocol: PROTEUS for Mammalian Cell Directed Evolution

The PROTEUS (PROTein Evolution Using Selection) system represents a recent advancement, enabling directed evolution directly in mammalian cells [7]. This is significant as most prior work relied on bacterial systems.

Experimental Workflow:

- System Design: PROTEUS uses chimeric virus-like particles, combining the outer shell of one virus with the genes of another. This design is crucial for stability, preventing the system from "cheating" by evolving trivial solutions that do not answer the intended biological question [7].

- Programming the Cell: Mammalian cells are programmed with a genetic problem (e.g., "efficiently turn off a human disease gene") [7].

- Diversification and Parallel Processing: The system explores millions of possible genetic sequences in parallel within the mammalian cell environment. The use of the viral system allows for this massive parallel processing [7].

- Selection and Amplification: Variants that provide improved solutions (e.g., better gene silencing) become dominant within the cellular population, while incorrect solutions disappear. The winning variants can then be isolated and studied [7] [18].

Key Application: Researchers have used PROTEUS to develop improved versions of proteins that are more easily regulated by drugs and nanobodies that can detect DNA damage, a key process in cancer development [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of a directed evolution campaign requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Directed Evolution |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Provides optimized mixtures of DNA polymerase, nucleotides, and buffer conditions to introduce random point mutations during gene amplification [17]. |

| PURE System | A reconstituted, customizable in vitro translation system. Allows for the incorporation of unnatural amino acids (e.g., homopropargylglycine) by excluding competing natural amino acids [17]. |

| Puromycin-Linker | A critical reagent in mRNA display. This molecule, an analogue of the 3'-end of tyrosyl-tRNA, covalently links the synthesized peptide to its encoding mRNA, creating the essential genotype-phenotype link [17]. |

| Homopropargylglycine (HPG) | An "clickable" alkynyl unnatural amino acid. Used in conjunction with the PURE system, it replaces methionine and allows for subsequent chemical conjugation (e.g., of glycans) via copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) [17]. |

| Chimeric Virus-like Particles (for PROTEUS) | The core engineering component of the PROTEUS system. Provides a stable and robust vehicle to perform iterative cycles of evolution and selection within the complex environment of a mammalian cell [7]. |

| Immobilized Target Ligand | Essential for affinity-based selection methods like phage display. The target protein or molecule is fixed to a solid support to bind and isolate interacting variants from a library [13]. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrate | A proxy substrate that produces a fluorescent or colored product upon enzymatic reaction. Enables high-throughput screening by allowing rapid identification of active enzyme variants from large libraries [13] [15]. |

| FLUORAD FC-100 | FLUORAD FC-100, CAS:147335-40-8, MF:C8H15N3.2HBr |

| STEEL | STEEL, CAS:12597-69-2, MF:C34H32N2Na2O10S2 |

Protein engineering is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, enabling the creation of tailored enzymes and proteins for applications ranging from drug development to industrial biocatalysis [19] [20]. The two primary strategies for this tailoring—directed evolution and rational design—offer distinct pathways to optimizing protein function [19] [21]. Directed evolution mimics natural selection in a laboratory setting, employing iterative rounds of random mutagenesis and screening to enhance protein properties without requiring prior structural knowledge [22] [23]. In contrast, rational design operates like a precision engineering tool, using detailed knowledge of protein structure and mechanism to introduce specific, calculated mutations that alter function [24] [20]. The choice between these approaches, or their combination, is fundamental to the success of biotechnology research and development projects. This application note delineates the advantages, limitations, and optimal use cases for each method to guide researchers in selecting the most efficient strategy for their specific goals.

Core Principle Comparison

The following table summarizes the fundamental distinctions between directed evolution and rational design.

Table 1: Core Principles of Directed Evolution and Rational Design

| Aspect | Directed Evolution | Rational Design |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Mimics natural evolution; a discovery-based process [22] | Analogous to architectural planning; a hypothesis-driven process [19] |

| Requirement for Structural Data | Not required [23] | Essential [24] [20] |

| Key Steps | 1. Library creation via random mutagenesis2. High-throughput screening/selection3. Amplification of improved variants4. Iteration of cycles [22] [23] | 1. Analysis of protein structure/mechanism2. In silico prediction of beneficial mutations3. Site-directed mutagenesis4. Functional characterization [24] |

| Nature of Mutations | Random, can uncover non-intuitive solutions [23] | Targeted and specific, based on understanding [24] |

| Automation & Throughput | Relies on high-throughput screening of large libraries (often >10^4 variants) [15] [23] | Lower throughput; typically tests a small number of designed variants [20] |

The workflows for these two methods are fundamentally different, as illustrated below.

Advantages, Limitations, and Use Cases

Directed Evolution

Advantages:

- Bypasses Need for Structural Knowledge: Its most significant advantage is the ability to improve proteins even when their three-dimensional structure or detailed catalytic mechanism is unknown [23].

- Discovers Non-Intuitive Solutions: The random nature of mutagenesis can uncover beneficial mutations that would be impossible to predict through rational models, often leading to novel and highly optimized variants [23].

- Proven Robustness: It is a well-established, versatile method responsible for engineering enzymes for a vast array of applications, from industrial biocatalysts to therapeutic proteins [22] [23].

Limitations:

- High-Throughput Screening Bottleneck: The requirement to screen large libraries for improved variants is often the most time-consuming and resource-intensive part of the process [23].

- Risk of Local Optima: The iterative process can become trapped in local fitness maxima, where incremental improvements plateau without discovering a globally optimal variant that requires multiple simultaneous mutations [19].

Ideal Use Cases:

- Optimizing complex properties like thermostability or organic solvent tolerance [20].

- Altering substrate specificity or creating novel enzymatic activities [22].

- When structural information for the target protein is unavailable or incomplete.

Rational Design

Advantages:

- Precision and Speed: When successful, it can achieve the desired functional change in a few targeted mutations, avoiding the need to generate and screen large libraries [24] [20].

- Deepens Mechanistic Understanding: The hypothesis-driven approach provides direct insight into the relationship between protein structure and function [24].

- Efficient for Specific Changes: Ideal for tasks like altering cofactor specificity or remodeling an active site based on a known substrate analog [24] [21].

Limitations:

- Dependent on Accurate Structural Models: Its success is wholly contingent on the availability and accuracy of high-resolution structural data (from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM) and computational models [24].

- Incomplete Predictive Power: The complex relationship between protein sequence, structure, dynamics, and function is not fully understood, making the outcomes of rational design sometimes unpredictable [24].

Ideal Use Cases:

- Engineering a few key residues in the active site to alter enantioselectivity [24].

- Introducing disulfide bonds or other mutations to improve thermodynamic stability [24].

- "Consensus" engineering, where a protein is mutated to match the most common amino acid found in its homologs [24].

Table 2: Summary of Application Suitability

| Application Goal | Recommended Primary Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Improve Thermostability | Directed Evolution [20] | Effective without structural data. Screening can be done by heating cell lysates. |

| Alter Enantioselectivity | Semi-Rational [25] | Saturation mutagenesis of active site residues guided by structural analysis. |

| Change Cofactor Specificity | Rational Design [21] | Requires understanding of cofactor-binding pocket. |

| Develop Novel Catalytic Activity | Directed Evolution [22] | Powerful for discovering non-natural functions from large sequence spaces. |

| Improve Kinetic Parameters (kcat/KM) | Both | Directed evolution explores broad space; rational design fine-tunes active site. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Directed Evolution via Error-Prone PCR

This protocol outlines a basic directed evolution cycle to improve a property like thermostability or activity in a microbial host.

1. Library Generation by Error-Prone PCR (epPCR)

- Reaction Setup: In a 50 µL reaction, combine: 10-100 ng DNA template, 5 µL 10x reaction buffer (without Mg2+), 0.2 mM each dATP and dGTP, 1 mM each dCTP and dTTP (nucleotide imbalance reduces fidelity), 0.1-0.5 mM MnCl2 (critical for increasing error rate), 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (lacks proofreading), and 20 pmol of each primer [23].

- Thermocycling: Standard PCR cycling (e.g., 30 cycles of: 95°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 1 min/kb).

- Purification and Cloning: Purify the PCR product and clone it into an appropriate expression vector. Transform the ligated plasmid into a competent bacterial host (e.g., E. coli) to create the variant library. Aim for a library size of at least 10^4-10^6 clones to ensure diversity [23].

2. High-Throughput Screening

- Plate-Based Assay: For thermostability, culture individual colonies in 96-well deep-well plates. Induce protein expression and lyse cells. Split the lysate: heat one portion (e.g., 60°C for 10 min) and keep the other on ice. Centrifuge to remove precipitated protein.

- Activity Measurement: Assay both heated and unheated lysates for enzymatic activity in a 96-well plate using a colorimetric or fluorometric substrate. Measure the initial reaction rates with a plate reader [23].

- Selection: Calculate the residual activity for each variant (activityheated / activityunheated). Select clones with the highest residual activity for the next round.

3. Iteration

- Isolate plasmid DNA from the "winner" variants.

- Use this pooled DNA as the template for the next round of epPCR, often with slightly more stringent selection conditions (e.g., higher heating temperature) to drive further improvement [23].

Protocol for Rational Design via Site-Directed Mutagenesis

This protocol describes the process of designing and creating a specific point mutation to, for example, alter substrate sterics.

1. Computational Analysis and Mutation Design

- Structure Analysis: Obtain the protein structure (PDB file). Using molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL), identify active site residues interacting with the substrate.

- Residue Selection: Select a residue whose side chain appears to create steric hindrance against a desired, larger substrate. The hypothesis is that mutating this residue to a smaller one (e.g., Phe → Ala) will accommodate the substrate and improve activity [24].

- Energy Minimization: Use computational protein design software (e.g., Rosetta) to model the mutation, optimize the side-chain rotamer, and assess the predicted stability (ΔΔG) of the variant [24].

2. Site-Directed Mutagenesis

- Primer Design: Design two complementary primers (forward and reverse) that are 25-45 bases long, with the desired mutation in the center. The primer should have a melting temperature (Tm) of ≥78°C.

- PCR Amplification: Set up a 50 µL PCR reaction with: 10-50 ng plasmid template, 125 ng of each primer, 1x reaction buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, and a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., PfuUltra). Use a thermocycler program optimized for primer extension without strand displacement.

- Template Digestion: After PCR, digest the methylated parental DNA template by adding 1 µL of DpnI restriction enzyme directly to the PCR reaction and incubating at 37°C for 1-2 hours.

- Transformation and Validation: Transform the DpnI-treated DNA into competent E. coli. Isolate plasmid DNA from resulting colonies and sequence the gene to confirm the presence of the desired mutation and absence of secondary mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table lists essential materials and tools for executing protein engineering campaigns.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Protein Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | Enzyme for error-prone PCR; low fidelity introduces random mutations [23]. | Standard for epPCR protocols. |

| MnClâ‚‚ | Divalent cation added to epPCR reactions to significantly increase mutation rate [23]. | Concentration is tuned to control mutation frequency (typically 0.1-0.5 mM). |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests the methylated parental DNA template after site-directed mutagenesis, enriching for newly synthesized mutant plasmids [24]. | Critical step in many SDM kits. |

| Fluorescent/Colorimetric Substrates | Enable high-throughput screening of enzyme activity in microtiter plates or via FACS [15] [23]. | Must be designed to report on the specific function of interest. |

| Phage/Yeast Display Systems | Selection (not just screening) technology; links protein function to the genetics of the viral/yeast particle, allowing isolation of binders from vast libraries [15] [20]. | Powerful for engineering antibodies and peptides. |

| Structural Visualization Software | Essential for rational design to analyze active sites, substrate channels, and inter-residue interactions [24] [25]. | PyMOL, ChimeraX. |

| Protein Design Software | Computational tools for predicting the effect of mutations on stability and function, and for de novo design [24] [25]. | Rosetta, FoldX. |

| DAC 1 | DAC 1 Inhibitor | Explore DAC 1 (HDAC) inhibitors for epigenetic and cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Acid Brown 434 | Acid Brown 434, CAS:126851-40-9, MF:C22H13FeN6NaO11S, MW:648.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The distinction between directed evolution and rational design is increasingly blurred by semi-rational approaches [25] [20]. This hybrid methodology uses computational and bioinformatic analysis to identify "hotspot" residues likely to impact function. Researchers then perform focused randomization (e.g., saturation mutagenesis) at these few sites, creating smart libraries that are small in size but rich in functional diversity [25]. For instance, multiple sequence alignment of a protein family can reveal evolutionarily variable positions, which are prime targets for such libraries [24] [25].

Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are revolutionizing both strategies. AI can predict protein structures from sequences with remarkable accuracy, empowering rational design [20]. For directed evolution, AI models can analyze sequence-activity relationships from screening data to predict beneficial mutations and guide the design of smarter subsequent libraries, dramatically accelerating the engineering cycle [22]. The emergence of fully autonomous platforms, like SAMPLE (Self-driving Autonomous Machines for Protein Landscape Exploration), which combines AI-driven protein design with robotic experimentation, points to a future of increasingly automated and efficient protein engineering [20].

In conclusion, both directed evolution and rational design are powerful, complementary tools in the protein engineer's arsenal. The choice of method depends on the project's specific goals, constraints, and available knowledge. Directed evolution excels as a broad exploration tool when structural knowledge is limited, while rational design offers a precise and rapid path when a clear hypothesis can be formulated from structural data. The most successful modern research pipelines often integrate both, leveraging their combined strengths to develop novel biocatalysts and therapeutics with unprecedented efficiency.

Directed evolution (DE), a cornerstone technique in protein engineering, has traditionally focused on optimizing the function of single proteins. This method mimics natural selection in a laboratory setting by employing iterative rounds of diversification, selection, and amplification to steer proteins toward a user-defined goal [13]. However, the field is undergoing a significant paradigm shift. The scope of directed evolution is rapidly expanding beyond single-gene optimization to encompass the engineering of complex functionalities within entire metabolic pathways and the reprogramming of complex cellular behaviors [17]. This progression marks a critical evolution in biotechnology, enabling researchers to tackle more ambitious challenges in synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development.

The following table summarizes the core progression in the scope of directed evolution efforts.

Table 1: The Expanding Scope of Directed Evolution Applications

| Evolution Target | Primary Objective | Key Methodologies | Example Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Proteins | Optimize stability, binding affinity, catalytic activity, or enantioselectivity [13] [26]. | Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, site-saturation mutagenesis, phage/mRNA display [15] [13] [17]. | Engineering of P450 enzymes for novel biocatalytic transformations [26]. |

| Metabolic Pathways | Refactor multi-step biosynthetic pathways for enhanced production of valuable compounds [17]. | DNA shuffling of operons, combinatorial assembly of pathway variants, in vivo selection [17]. | Evolution of an operon's function to improve a biotransformation process [17]. |

| Whole Cells | Engineer novel cellular functions, improve tolerance to industrial stresses, or create complex genetic circuits. | Orthogonal replication systems, in vivo mutagenesis (e.g., PROTEUS), continuous evolution platforms [18]. | Evolution of proteins directly inside human cells to improve patient tolerance of treatments [18]. |

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols to guide researchers in leveraging these advanced directed evolution strategies.

Application Notes: Key Technological Advances

Machine Learning (ML)-Assisted Directed Evolution

A major advancement in evolving single proteins is the integration of machine learning, which helps navigate the vastness of protein sequence space and overcome challenges like epistasis (non-additive interactions between mutations). Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) is a powerful iterative workflow that combines wet-lab experimentation with computational modeling [1].

- Principle: ALDE uses an initial set of sequence-fitness data to train a supervised ML model. This model then prioritizes the next batch of sequences to test experimentally based on predicted fitness and uncertainty quantification, balancing exploration and exploitation. The new experimental data is used to retrain the model, creating a closed-loop optimization cycle [1].

- Application: This approach has been successfully used to optimize a challenging epistatic landscape of five residues in a protoglobin (ParPgb) for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction. In just three rounds, ALDE improved the product yield from 12% to 93%, exploring only about 0.01% of the total sequence space [1].

In Vivo Evolution of Mammalian Cells with PROTEUS

The PROTEUS (PROTein Evolution Using Selection) system represents a leap forward in whole-cell directed evolution. Developed to evolve molecules within the complex environment of mammalian cells, it fast-forwards evolution by years and even decades [18].

- Significance: Traditional directed evolution is often performed in bacterial or yeast cells. PROTEUS allows for the optimization of proteins, antibodies, and cellular pathways directly in human cells. This ensures that the evolved functions are tailored to a physiologically relevant context, which is crucial for developing therapeutics that patients can better tolerate and process [18].

- Implication: This technology enables the screening of millions of genetic sequences to find optimal adaptations, potentially allowing for the development of cell-based therapies and the ability to "switch genetic diseases off" [18].

DNA Shuffling for Pathway Engineering

For evolving metabolic pathways, DNA shuffling is a key methodology that mimics natural recombination.

- Principle: This technique involves random recombination of DNA fragments from closely related gene sequences to create chimeric genes or operons [17]. This allows for the mixing of beneficial mutations from different parents and the exploration of sequence space more efficiently than point mutagenesis alone.

- Application: DNA shuffling has been used not only to improve individual enzymes but also to evolve the function of an entire operon, demonstrating its power for optimizing metabolic pathways for novel biotransformation processes in vivo [17]. For example, the thermostability of lipase from Bacillus pumilus was enhanced approximately tenfold using this method [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) for a Multi-Site Variant Library

This protocol is adapted from the application of ALDE to optimize five epistatic residues in the ParPgb enzyme [1].

I. Define Objective and Design Space

- Define a quantitative fitness objective (e.g., product yield, selectivity).

- Select k target residues for randomization, defining a theoretical sequence space of 20^k variants.

II. Generate Initial Library and Collect Data

- Method: Simultaneously mutate all k residues using PCR-based mutagenesis with NNK degenerate codons.

- Screening: Express variants and screen using a relevant assay (e.g., GC, HPLC). An initial library of tens to hundreds of variants provides the starting dataset.

III. Computational Model Training and Variant Proposal

- Encoding: Represent protein sequences numerically (e.g., one-hot encoding, embeddings from protein language models).

- Model Training: Train a supervised ML model (e.g., Gaussian process, neural network) on the collected sequence-fitness data. The model should provide uncertainty estimates.

- Acquisition: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound, Expected Improvement) to rank all sequences in the design space. Select the top N (e.g., 50-200) variants for the next round.

IV. Iterative Experimental Rounds

- The top N proposed variants are synthesized, expressed, and assayed.

- New data is added to the training set, and the process returns to Step III.

- Continue until fitness is sufficiently optimized or performance plateaus.

Protocol: DNA Shuffling for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

This protocol outlines the process for evolving a multi-enzyme pathway via DNA shuffling [17].

I. Library Generation via Shuffling

- DNA Preparation: Isolate and purify the genes or operons of interest from several related parental sequences (typically with >70% sequence identity).

- Fragmentation: Digest the DNA pool using DNase I to create random fragments of a desired size (e.g., 50-100 bp).

- Reassembly: Perform a primerless PCR. Fragments with homologous regions anneal and are extended by a DNA polymerase, reassembling into full-length chimeric genes.

- Amplification: Use standard PCR with gene-specific primers to amplify the reassembled full-length products.

II. Screening and Selection

- Cloning: Clone the shuffled library into an appropriate expression vector and transform into a host organism (e.g., E. coli).

- High-Throughput Screening: Screen for the desired pathway-level phenotype. This could involve:

- Growth Selection: If the pathway produces a metabolite essential for growth or confers resistance to a toxin.

- Fluorescent/Absorbance-Based Assays: Using surrogate substrates that produce a detectable signal.

- Chromatography (HPLC/GC): For direct measurement of product titer from microtiter plate cultures.

- Isolation of Hits: Isolate the best-performing clones from the primary screen for further validation and sequencing.

III. Iterative Rounds

- Use the best-performing chimeric sequences as the parental templates for subsequent rounds of DNA shuffling to accumulate beneficial mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for executing advanced directed evolution campaigns.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Directed Evolution

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| KAPA2G Fast Multiplex PCR Kit | High-fidelity, fast polymerase for robust library construction and amplification. Derived from directed evolution [26]. | Generating mutant libraries via error-prone PCR or amplifying recombined genes from DNA shuffling [26]. |

| NNK Degenerate Codons | Allows for saturation mutagenesis at specific positions, encoding all 20 amino acids and one stop codon. | Creating focused libraries for active site residues in a protein [1]. |

| PURE System | A reconstituted in vitro transcription-translation system. Highly customizable for incorporating unnatural amino acids [17]. | mRNA display with homopropargylglycine (HPG) for subsequent "click" chemistry-based glycosylation of peptides [17]. |

| Homopropargylglycine (HPG) | An unnatural, "clickable" methionine analogue incorporated during in vitro translation [17]. | Enables site-specific conjugation of moieties like glycans to peptides/proteins in mRNA display libraries [17]. |

| Specialized Host Strains | Bacterial or yeast strains engineered for high-efficiency transformation and protein expression. | Serving as hosts for mutant library expression during screening and selection. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Ultra-high-throughput screening technology for analyzing and sorting cells based on fluorescent signals [15]. | Screening displayed protein libraries (e.g., yeast display) for binding or enzymatic activity using fluorescent substrates [15]. |

| indralin | Indralin | Indralin is an alpha1-adrenomimetic radioprotector for research. It is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| R: CL | R: CL Reagent | R: CL reagent is for Research Use Only. Not for use in diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. This product is not for human or animal use. |

Toolkit for Innovation: Key Techniques and Biotech Applications

In the field of directed evolution, the generation of diverse genetic libraries constitutes a critical first step for engineering proteins with enhanced properties, such as improved catalytic activity, stability, or novel functions. These methods mimic natural evolution in laboratory settings by creating vast populations of protein variants from which improved clones can be identified through screening or selection. This application note provides detailed protocols and comparative analysis of three fundamental library generation techniques—Error-Prone PCR, DNA Shuffling, and Saturation Mutagenesis—framed within the context of directed evolution for biotechnology applications. Each method offers distinct advantages in the type and diversity of mutations introduced, enabling researchers to select the most appropriate strategy based on their specific protein engineering goals.

Error-Prone PCR (epPCR)

Principle and Applications

Error-prone PCR is a widely adopted technique for introducing random mutations throughout a target gene. Unlike conventional PCR which aims for high-fidelity amplification, epPCR deliberately reduces replication fidelity by altering reaction conditions, resulting in nucleotide misincorporations during DNA synthesis [27] [28]. The method was initially developed by Caldwell and Joyce in 1992 and has since become a cornerstone technique in directed evolution experiments [27]. Biotechnologists favor epPCR for its simplicity and ability to generate diverse mutant libraries in a single reaction, making it particularly valuable for exploring functional improvements when structural information is limited or when broad exploration of sequence space is desired [27].

Key applications of epPCR in directed evolution include protein engineering for improved enzyme activity or stability, directed evolution through iterative mutation and selection cycles, drug development for studying drug resistance mechanisms, and functional genomics for identifying essential gene regions [27]. The technique is cost-effective and time-efficient, allowing laboratories to generate hundreds to thousands of mutants without sophisticated equipment [27].

Standard Protocol

Materials:

- Template DNA (purified, 100-1000 ng/μL)

- Taq DNA polymerase (without proofreading activity)

- Forward and reverse primers (specific to target gene)

- dNTP mixture (imbalanced concentrations)

- MgClâ‚‚ (higher concentration than standard PCR)

- MnClâ‚‚ (mutation-enhancing additive)

- PCR buffer (standard composition)

- Thermocycler

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 50 μL reaction mixture containing:

- 1× PCR buffer

- 7 mM MgClâ‚‚ (higher than standard 1.5-3 mM)

- 0.5 mM MnClâ‚‚

- 0.4 mM each dNTP (or use imbalanced dNTP ratios)

- 50 ng template DNA

- 25 pmol each primer

- 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase [29]

Thermocycling:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 3 minutes

- 30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 92°C for 1 minute

- Annealing: 60°C for 1 minute

- Extension: 72°C for 2 minutes

- Final extension: 72°C for 7 minutes [29]

Product Analysis:

- Verify amplification by agarose gel electrophoresis

- Purify PCR product using standard kits

- Clone into appropriate expression vector

- Transform into host cells for library generation

Critical Considerations:

- Use Taq polymerase without proofreading activity to prevent correction of incorporated errors [28]

- Optimize mutation rate by adjusting Mg²âº, Mn²âº, and dNTP concentrations [27]

- Control mutation frequency to approximately 1-3 mutations per kilobase to balance diversity and protein functionality [28]

- Excessive mutation rates can lead to non-functional proteins, while insufficient rates limit diversity [27]

Workflow Visualization

DNA Shuffling

Principle and Applications

DNA shuffling, also known as molecular breeding, is an in vitro random recombination method that enables the reassembly of gene fragments from homologous sequences, generating chimeric genes with combinations of mutations from parent genes [30] [31]. First described by Willem P.C. Stemmer in 1994, this technique goes beyond point mutagenesis by facilitating the recombination of beneficial mutations from multiple genes, significantly accelerating the directed evolution process [30] [31]. DNA shuffling mimics natural recombination processes, allowing for the exploration of a broader sequence space than methods relying solely on point mutations.

The key advantage of DNA shuffling lies in its ability to combine beneficial mutations from different parent sequences while simultaneously removing neutral or deleterious mutations through recombination [30]. This method is particularly valuable for evolving complex protein properties that require multiple mutations, such as substrate specificity, enzyme activity, and thermal stability [31]. Applications span protein and small molecule pharmaceutical development, bioremediation enzyme engineering, vaccine improvement, and gene therapy vector optimization [30].

Standard Protocol (Molecular Breeding Method)

Materials:

- Parent DNA sequences (homologous genes or mutant libraries)

- DNase I (for random fragmentation)

- DNA polymerase (with proofreading capability for reassembly)

- dNTP mixture

- PCR primers (specific to gene termini)

- Thermostable DNA polymerase

- Thermocycler

Procedure:

- Gene Fragmentation:

- Combine 2-4 μg of parent DNA(s) in 100 μL of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM MgCl₂

- Add 0.15 units DNase I and incubate at room temperature for 5-10 minutes

- Monitor fragmentation by agarose gel electrophoresis; target fragment sizes of 100-300 bp for a 1 kb gene [31]

Fragment Purification:

- Separate fragments on 2% low-melting-point agarose gel

- Excise and purify fragments in the 100-300 bp range

- Use ion-exchange paper or gel extraction kits for purification [31]

Reassembly PCR:

- Resuspend purified fragments at high concentration (10-30 ng/μL) in PCR mix

- Perform PCR without primers: 30-45 cycles of:

- 94°C for 30 seconds (denaturation)

- 45-50°C for 30 seconds (annealing)

- 72°C for 30 seconds (extension) [31]

- Include a proofreading polymerase (e.g., Pfu) to minimize additional mutations if desired

Amplification of Full-Length Genes:

- Dilute reassembly PCR product 40-fold in fresh PCR mix containing 0.8 μM gene-specific primers

- Perform 20 cycles of standard PCR with annealing temperature optimized for primers

- Gel-purify correctly sized products for cloning [31]

Critical Considerations:

- Degree of homology between parent genes determines recombination efficiency

- Fragment size affects the number of crossovers; smaller fragments increase recombination frequency

- Polymerase choice balances mutation rate and reassembly efficiency

- Backcrossing (shuffling with wild-type sequences) can eliminate neutral mutations [31]

Workflow Visualization

Saturation Mutagenesis

Principle and Applications

Saturation mutagenesis is a targeted approach that replaces specific amino acid positions with all possible amino acid substitutions, enabling comprehensive exploration of function and structure at defined sites [32] [33]. This method represents a compromise between fully randomized approaches and rational design, offering controlled diversity with reduced screening requirements compared to random mutagenesis techniques. By focusing on predetermined "hot spots" such as active sites or regions known to influence protein properties, researchers can efficiently optimize enzymes without the need for extensive structural information.

The technique is particularly valuable for fine-tuning catalytic properties, altering substrate specificity, enhancing enantioselectivity, and improving enzyme stability [32]. Advanced implementations like Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis (ISM) enable combinatorial exploration of multiple target sites, identifying synergistic effects between mutations that might be missed in single-step approaches [32]. Saturation mutagenesis has proven successful in developing enzymes for industrial processes, fine chemical synthesis, and bioremediation applications [32].

Standard Protocol

Materials:

- Template DNA (plasmid vector with target gene)

- Mutagenic primers (degenerate at target codon)

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase

- dNTP mixture

- DpnI restriction enzyme (for template digestion)

- Competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α or XL1-Blue)

Procedure:

- Primer Design:

- Design forward and reverse primers containing the degenerate target codon (NNK or NNN) in the middle

- NNK degeneration (K = G or T) encodes all 20 amino acids plus one stop codon (32 variants)

- NNN degeneration encodes all 20 amino acids plus three stop codons (64 variants)

- Include 15-20 non-mutated bases flanking both sides of the degenerate codon

- Phosphorylate primers if using non-strand-displacing polymerases [33]

PCR Amplification:

- Set up reaction using high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., QuikChange protocol)

- Thermocycling parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 18 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 55-60°C for 1 minute

- Extension: 68°C for 1-2 minutes per kb of plasmid [33]

Template Digestion and Transformation:

- Digest PCR product with DpnI (10 U/μL) for 1-2 hours at 37°C

- DpnI specifically cleaves methylated parental DNA template

- Transform 1-5 μL of digestion reaction into competent E. coli cells

- Plate on selective media to obtain mutant library [33]

Critical Considerations:

- NNK degeneracy reduces library size (32 codons) while maintaining complete amino acid coverage

- Library completeness follows the formula P = 1 - (1 - 1/N)^T, where N is variant number and T is transformants

- Screen 2-3× library size (e.g., 95-200 clones for NNK) to ensure >95% coverage [32]

- For multiple sites, consider combinatorial library sizes and screening capacity

Workflow Visualization

Comparative Analysis

Method Selection Guide

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Library Generation Methods

| Parameter | Error-Prone PCR | DNA Shuffling | Saturation Mutagenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Type | Random point mutations | Recombination + point mutations | Targeted amino acid substitutions |

| Mutation Control | Low (random distribution) | Medium (homology-dependent) | High (specific codons) |

| Library Diversity | Broad, sequence-wide | Focused on beneficial combinations | Focused on predefined sites |

| Structural Information Required | None | None (but beneficial) | Recommended for site selection |

| Best Applications | Initial diversity generation, unknown targets | Recombining beneficial mutations, family shuffling | Active site optimization, mechanistic studies |

| Typical Mutation Rate | 1-3 mutations/kb [28] | Variable (dependent on parents) | All possible substitutions at target codon |

| Screening Effort | High (large libraries) | Medium-high | Medium (focused libraries) |

| Technical Complexity | Low | Medium-high | Low-medium |

| Key Limitations | Mostly neutral/deleterious mutations, no crossover | Requires sequence homology | Limited to predefined regions |

| RG7775 | RG7775, MF:C12H12N4O | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| C620-0696 | C620-0696, MF:C24H24N4O3, MW:416.481 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Library Generation Methods

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Library Generation |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | Taq polymerase (without proofreading) | Error-prone PCR: introduces mutations through low fidelity [27] [28] |

| Polymerases | Pfu polymerase, Klenow fragment | DNA shuffling: high-fidelity assembly of fragments [27] [31] |

| Nucleases | DNase I | DNA shuffling: random fragmentation of parent genes [30] [31] |

| Restriction Enzymes | DpnI | Saturation mutagenesis: selective digestion of methylated template DNA [33] |

| Mutation Enhancers | MnClâ‚‚, imbalanced dNTPs | Error-prone PCR: reduces replication fidelity to increase mutation rate [27] [34] |

| Cloning Systems | TA cloning, restriction enzyme cloning | All methods: insertion of mutated genes into expression vectors |

| Competent Cells | E. coli DH5α, XL1-Blue | All methods: efficient transformation of mutant libraries [33] |

| Degenerate Primers | NNK, NNN codons | Saturation mutagenesis: encoding all possible amino acid substitutions [32] [33] |

Advanced Applications in Biotechnology

Directed Evolution Strategies

The integration of these library generation methods into directed evolution pipelines has revolutionized protein engineering for biotechnology applications. Iterative approaches, combining epPCR for initial diversification followed by DNA shuffling to recombine beneficial mutations, and saturation mutagenesis for fine-tuning, have yielded remarkable successes in enzyme engineering [32]. Notable examples include the evolution of industrial enzymes for detergents and biofuels, therapeutic protein optimization, and development of biocatalysts for fine chemical synthesis [27] [32].

For environmental applications, these methods have generated enzymes with enhanced capabilities for bioremediation and detoxification of pollutants [32]. DNA shuffling of homologous oxygenases, for example, has produced variants with expanded substrate ranges for degradation of environmental contaminants [30]. Similarly, saturation mutagenesis has enabled the optimization of enzyme activity and stability under specific process conditions required for industrial applications [32] [33].

Emerging Technologies

Recent advancements in library generation methods include the development of novel techniques such as Nucleotide Exchange and Excision Technology (NExT) DNA shuffling, which utilizes uridine triphosphate incorporation followed by enzymatic excision to create defined fragmentation patterns [29]. Similarly, deaminase-driven random mutation (DRM) systems employing engineered cytidine and adenosine deaminases have demonstrated significantly higher mutation frequencies and diversity compared to traditional epPCR [35].

Automation and high-throughput screening methodologies have further enhanced the implementation of these library generation techniques, enabling researchers to explore larger sequence spaces and identify improved variants more efficiently. The continuous refinement of these methods promises to accelerate the development of novel biocatalysts for pharmaceutical, industrial, and environmental applications.

Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, and saturation mutagenesis represent powerful, complementary tools in the directed evolution toolkit. Error-prone PCR offers straightforward generation of random mutations across entire genes, DNA shuffling enables efficient recombination of beneficial mutations, and saturation mutagenesis provides targeted exploration of specific residues. The selection of an appropriate method depends on the specific protein engineering goals, available structural information, and screening capabilities. As directed evolution continues to advance biotechnology research and development, these library generation methods remain fundamental to engineering proteins with novel functions and optimized properties for diverse applications.

Within the framework of directed enzyme evolution, the successful isolation of desired mutants from vast libraries is the cornerstone of engineering proteins with enhanced properties such as altered substrate specificity, thermostability, and organic solvent resistance [36]. The primary bottleneck in this process is often not the creation of genetic diversity, but its effective analysis. High-throughput screening (HTS) and selection methods are, therefore, critical as they enable researchers to rapidly sift through multifarious candidates to identify those with desirable traits [36]. This article provides detailed Application Notes and Protocols for three pivotal techniques—Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), Phage Display, and Compartmentalization—that have revolutionized the field of directed evolution by coupling genotype to phenotype, thereby allowing for the efficient evolution of enzymes and antibodies for biotechnological and therapeutic applications.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

Application Notes

FACS is a powerful high-throughput screening platform capable of analyzing and sorting individual cells based on their fluorescent signals at remarkable speeds of up to 30,000 cells per second [36]. Its utility in directed evolution stems from its compatibility with various assay formats that link intracellular or surface-displayed enzyme activity to a fluorescent output. Key applications include:

- Product Entrapment: A cell-permeable, non-fluorescent substrate is converted by an intracellular enzyme into a fluorescent, impermeable product that accumulates within the cell. This enables direct sorting of active clones based on their fluorescence intensity [36]. For instance, this method identified a glycosyltransferase variant with over 400-fold enhanced activity [36].

- GFP-Reporter Assays: The activity of the target enzyme is coupled to the expression of a fluorescent protein like GFP, allowing for the screening of enzymes based on their functional output, such as in the evolution of Cre recombinase mutants [36].

- Cell Surface Display: Enzymes displayed on the cell surface (e.g., on yeast or bacteria) can catalyze reactions that lead to the attachment of a fluorescent substrate to the cell itself. This bond-forming activity was used to achieve a 6,000-fold enrichment of active clones in a single sorting round [36].

Detailed Protocol

The following protocol outlines the key steps for a FACS-based screen using a product entrapment assay.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Fluorescent Substrate | A cell-permeable compound that is converted by the target enzyme into an impermeable, fluorescent product. |

| Expression Host Cells | Cells (e.g., E. coli or yeast) harboring the mutant enzyme library. |

| Flow Cytometry Buffer | A buffered saline solution (e.g., PBS) to maintain cell viability and facilitate analysis. |

| FACS Machine | Instrument for detecting fluorescence and physically sorting cells. |

Procedure:

- Library Transformation & Culture: Transform the mutant enzyme library into an appropriate microbial host (e.g., E. coli). Grow individual clones in deep-well microtiter plates or flasks under selective conditions to induce protein expression [36].

- Substrate Incubation: Harvest the cells and resuspend them in an appropriate buffer. Incubate the cell suspension with the cell-permeable, fluorescent substrate. The incubation time and temperature should be optimized to allow the enzymatic reaction and subsequent product entrapment to occur [36].

- Washing: Pellet the cells and wash them thoroughly with flow cytometry buffer to remove any extracellular substrate and fluorescent reaction products that have not been trapped inside the cell. This step is crucial for reducing background fluorescence.

- Sample Preparation & FACS Analysis: Resuspend the washed cell pellet in an appropriate volume of ice-cold buffer for FACS analysis. It is critical to include control samples (e.g., cells without the enzyme or with a wild-type enzyme) to set the sorting gates accurately.