Environmental DNA (eDNA): Revolutionizing Biodiversity Monitoring for Scientific Research and Conservation

This article examines the transformative role of environmental DNA (eDNA) in biodiversity monitoring, a non-invasive method that detects genetic material shed by organisms into their environment.

Environmental DNA (eDNA): Revolutionizing Biodiversity Monitoring for Scientific Research and Conservation

Abstract

This article examines the transformative role of environmental DNA (eDNA) in biodiversity monitoring, a non-invasive method that detects genetic material shed by organisms into their environment. It explores the foundational science behind eDNA, its release mechanisms, and transport across aquatic, terrestrial, and aerial ecosystems. The content details cutting-edge methodological approaches, from single-species detection to metabarcoding for entire communities, highlighting innovative applications like leveraging existing air quality networks for continental-scale surveys. The article also addresses critical challenges, including standardization, data interpretation, and technological limitations, while providing a comparative analysis with traditional monitoring techniques. Finally, it synthesizes how this powerful, scalable tool is poised to generate the high-resolution, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data essential for achieving global biodiversity targets and informing biomedical and ecological research.

What is Environmental DNA? Unlocking the Genetic Footprint of Life

Environmental DNA (eDNA) refers to genetic material that can be extracted from environmental samples—such as soil, water, and air—without first isolating any target organisms. This DNA originates from shed skin cells, hair, saliva, mucus, feces, urine, and other biological debris that organisms continuously release into their surroundings [1] [2]. The analysis of eDNA represents a transformative tool in the biological sciences, allowing researchers to detect species and assess biodiversity through the genetic traces they leave behind. Its application spans two major, and seemingly distinct, fields: ecological and conservation research and forensic science [1] [2]. In ecology, eDNA is pivotal for monitoring biodiversity, tracking invasive species, and conserving protected fauna [1] [3]. Simultaneously, forensic science has begun to harness eDNA to investigate human presence at crime scenes, moving beyond traditional biological evidence to detect trace genetic material from surfaces, dust, and even the air [2]. This guide details the core methodologies, applications, and data standards that underpin the rigorous application of eDNA analysis across these domains, with a particular emphasis on its foundational role in biodiversity predictions research.

eDNA in Ecosystem Monitoring and Biodiversity Research

The use of eDNA in ecosystem monitoring has revolutionized the way scientists track and study biodiversity. It offers a highly sensitive, non-invasive method for detecting species, including those that are rare, elusive, or logistically challenging to monitor through traditional surveys.

Core Methodologies and Workflows

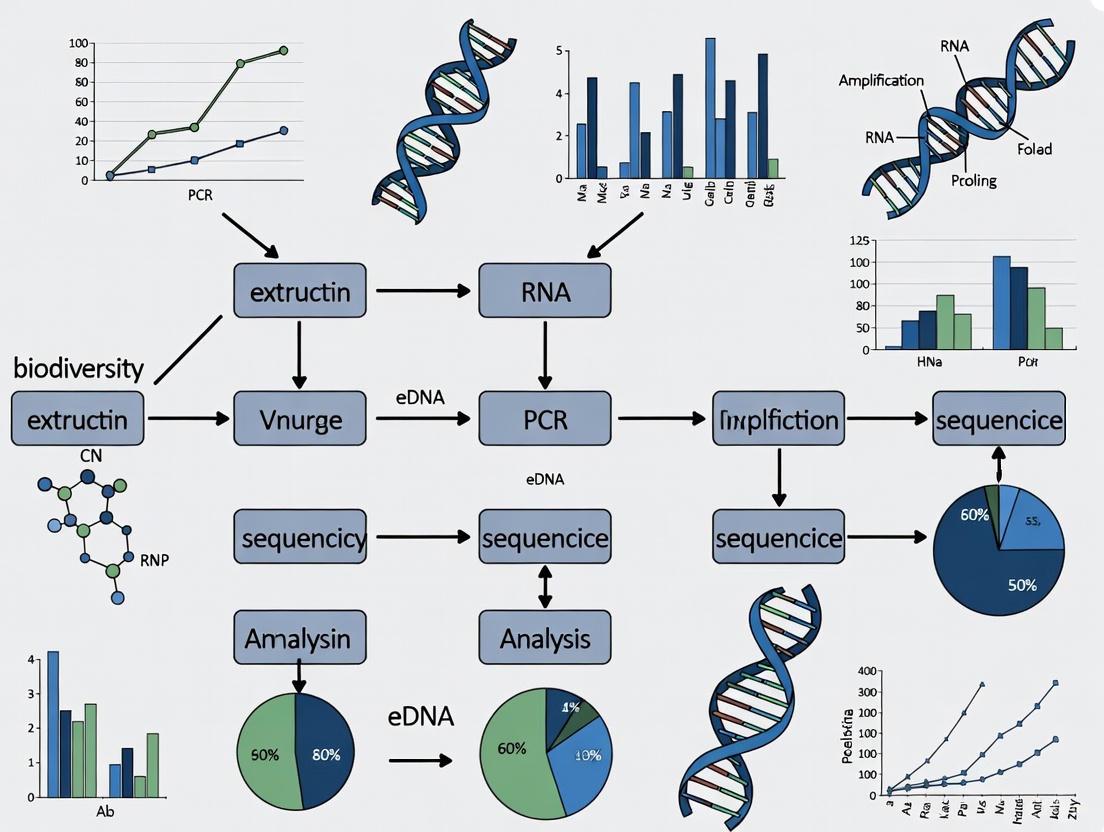

The standard workflow for biodiversity monitoring via eDNA involves a sequence of critical steps, from sample collection to data interpretation. The following diagram outlines this generalized process for a freshwater ecosystem, a common use case.

- Sample Collection: Water is collected from the target environment, typically followed by immediate filtration to capture particulate matter, including cellular debris containing DNA. The choice of filter pore size is critical and depends on the target organisms [1].

- Sample Preservation: After filtration, samples must be preserved to prevent DNA degradation. This often involves freezing or using chemical preservatives to maintain DNA integrity until laboratory analysis [1].

- DNA Extraction: In the laboratory, DNA is isolated and purified from the filter membranes or preserved samples. Robust extraction kits are essential for obtaining high-quality DNA suitable for downstream analysis [2].

- DNA Analysis: Two primary analytical methods are employed:

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): A targeted approach used to detect the presence of a specific species. It is highly sensitive and quantitative, ideal for tracking invasive species or species at risk [4] [3].

- Metabarcoding: A comprehensive approach that uses high-throughput sequencing to identify a broad range of taxa from a single sample. A specific genetic marker (or "barcode") is amplified and sequenced, allowing for the simultaneous detection of multiple species within a community [4].

- Data Interpretation and Species Identification: The generated DNA sequences are compared against reference databases (e.g., GenBank, BOLD) to assign taxonomic identities. The data is then interpreted to make inferences about species presence, relative abundance, and overall biodiversity [1].

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful eDNA analysis relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components of the "Scientist's Toolkit" for eDNA research.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for eDNA Analysis

| Item | Function in eDNA Workflow |

|---|---|

| Filter Membranes | The primary substrate for capturing eDNA from water samples; different pore sizes (e.g., 0.22µm to 1.0µm) target different particle size classes [1]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits designed to lyse cells and purify nucleic acids from complex environmental samples, removing inhibitors that can hamper downstream analysis [2]. |

| PCR Primers & Probes | Short, synthetic oligonucleotides designed to bind to and amplify a unique DNA barcode region of a target species (for qPCR) or a broader taxonomic group (for metabarcoding) [4]. |

| DNA Polymerases | Enzymes that catalyze the amplification of DNA during PCR or qPCR reactions; specialized formulations are often used for enhanced fidelity or performance with inhibited samples. |

| Positive Control DNA | Genomic DNA of a known target species, used to validate that the qPCR or sequencing assay is functioning correctly [4]. |

| Negative Controls | Nuclease-free water or blank filters processed alongside samples to monitor for laboratory or reagent contamination throughout the workflow [1]. |

eDNA in Forensic Science and Crime Scene Investigation

The forensic application of eDNA extends the same principles of detection to human genetics and crime scene analysis. It involves collecting and analyzing the trace human DNA that is continually shed into the environment, providing a powerful tool for linking individuals to specific locations.

Forensic Workflows and Experimental Protocols

Forensic eDNA investigations require meticulous protocols to ensure the integrity of evidence and the validity of genetic profiles. The workflow for a typical indoor crime scene investigation is detailed below.

- Evidence Collection: Forensic investigators collect samples from various surfaces and environmental media within a crime scene.

- Surface Swabs: Cotton or nylon swabs are used to collect touch DNA from frequently contacted surfaces like computer mice, keyboards, door handles, and light switches [2].

- Air Samples: Air filtration systems can capture airborne skin cells and respiratory droplets, providing a broader picture of human presence in a room [2].

- Dust Samples: Settled indoor dust accumulates skin cells, hair, and other biological material over time, serving as an archive of past occupants [2].

- Chain-of-Custody and Transport: A documented chain-of-custody is maintained for all samples to ensure their integrity for legal proceedings. Samples are transported securely to the forensic laboratory.

- DNA Extraction: The extraction of high-quality DNA from these diffuse and often mixed samples is a critical step. Recent research, such as the work by Fantinato et al. (2024), demonstrates that DNA/RNA co-extraction methods (E2) yield significantly higher quantities of DNA and more complex profiles compared to DNA-only extraction methods (E1), making them the preferred approach for forensic eDNA [2].

- DNA Profiling: The extracted DNA is analyzed using standard forensic techniques, primarily Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling, which creates a unique genetic fingerprint of an individual. In cases of degraded DNA, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis may be employed.

- Profile Interpretation and Transfer Dynamics: A key challenge is interpreting complex DNA mixtures and understanding transfer dynamics. Investigators must determine whether a DNA profile was deposited through direct contact or via indirect transfer (e.g., through air or dust). Studies show that DNA can persist in an environment for extended periods (e.g., >30 days), complicating the linkage of DNA presence to a specific crime event [2].

Quantitative Data from Forensic eDNA Studies

Empirical research provides critical data on the performance and reliability of eDNA in forensic applications. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a 2024 study on human eDNA.

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Forensic eDNA Analysis (Fantinato et al., 2024)

| Aspect of Investigation | Key Finding | Forensic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Method | DNA/RNA co-extraction (E2) yielded significantly higher DNA quantities and more complex profiles than DNA-only (E1) [2]. | The E2 method is superior for maximizing DNA recovery from trace environmental evidence. |

| Sample Type (Surface) | Personal surfaces (e.g., computer mouse) most frequently matched the primary user; shared surfaces (e.g., door handles) contained mixed DNA [2]. | Sampling strategy must be tailored to the investigative question to identify primary occupants vs. visitors. |

| Sample Type (Air/Dust) | Air and dust samples complemented surface findings, providing a broader view of DNA transfer. DNA from a former occupant was detected >30 days after departure [2]. | Highlights the potential for indirect transfer and the challenge of "background" DNA in interpreting scene relevance. |

| Persistence of DNA | DNA of an absent individual was detected on surfaces and in air samples more than 30 days after they had left the environment [2]. | Critical for assessing the timing of events; DNA presence does not necessarily indicate recent presence. |

Data Standards and Reporting for eDNA Research

For eDNA data to be reproducible, interoperable, and useful for large-scale biodiversity predictions, adherence to community data standards is paramount. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other international bodies have championed the adoption of standardized metadata checklists.

The FAIR eDNA (FAIRe) metadata checklist is strongly recommended for eDNA projects. It incorporates terms from established standards like MIxS (Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence), Darwin Core, and fields specific to eDNA data [4]. This ensures that data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). For projects involving quantitative PCR (qPCR), the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide a framework for reporting necessary experimental details [4].

Table 3: Recommended Data Standards and Repositories for eDNA Data

| Data Type | Recommended Standard | Recommended Repository |

|---|---|---|

| eDNA Survey Samples | FAIRe metadata checklist [4] | National Center for Environmental Information (NCEI) |

| Amplicon/Metabarcoding | MIxS (MIMARKS Survey package) [4] | NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) |

| Targeted qPCR Data | MIQE guidelines [4] | NCEI |

| Feature Observation Tables | BIOM format [4] | Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) / Ocean Biogeographic Information System (OBIS) |

Environmental DNA analysis has emerged as a powerful and versatile tool that bridges the fields of ecosystem science and forensic investigation. In freshwater and other ecosystems, it provides a sensitive and comprehensive method for biodiversity monitoring and the early detection of invasive species [1] [3]. In forensic science, it expands the evidentiary horizon beyond traditional samples, allowing investigators to detect human presence from surfaces, air, and dust [2]. The core of rigorous eDNA application lies in standardized methodologies—from optimized collection and preservation to validated extraction protocols—and the stringent application of data standards like the FAIRe checklist [1] [4]. As these methodologies continue to be refined and integrated with large-scale biodiversity prediction models, eDNA is poised to play an increasingly critical role in both understanding ecological networks and solving complex forensic cases.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has revolutionized biodiversity monitoring by allowing researchers to detect species non-invasively. The efficacy of this powerful tool hinges on a fundamental understanding of the sources of eDNA and the factors governing its release into the environment. This technical guide examines the biological origins of eDNA—including skin cells, feces, and respiratory particles—and the variables affecting its shedding rates, providing a foundation for robust biodiversity predictions in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

The Biological Origins of Environmental DNA

Environmental DNA originates from the continuous shedding of genetic material from organisms through a variety of biological processes and materials [5]. These sources can be broadly categorized based on their release mechanisms.

Lysis-Associated eDNA Release: This process involves the rupture of cell membranes, releasing intracellular DNA into the environment. Lysis can be triggered by bacterial endolysins, prophages, virulence factors, or antibiotics [5]. For instance, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, prophage endolysins facilitate eDNA release through explosive cell lysis, while pyocyanin stimulates release via H₂O₂-induced cell lysis [5]. Furthermore, mechanical damage to plants or invasion by pathogenic bacteria can lead to enzymatic degradation of plant structures, resulting in eDNA release [5].

Lysis-Free eDNA Release: eDNA can also be actively secreted into the environment without cell lysis. Mechanisms include the release via membrane vesicles (MVs), eosinophils, and mast cells [5]. In Streptococcus mutans, eDNA released from MVs is a vital component of biofilm matrices [5]. Active defense mechanisms also contribute; for example, neutrophils in the human immune system release eDNA to form Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) to combat pathogens, and plant root tips release eDNA in an analogous manner [5].

The primary biological materials that carry this DNA into the environment include:

- Feces and Urine: These excretions represent a significant source of DNA, providing a substantial contribution to the eDNA pool [5].

- Skin Cells and Mucus: Sloughed epithelial cells from mucosal layers and skin are continuously released, especially in aquatic environments [5] [6].

- Gametes and Scales: Spawn and scales are notable sources for fish and other aquatic organisms [6].

- Respiratory Particles: Particles expelled through the gills of fish or the respiratory tracts of terrestrial animals contain cellular material [6].

Quantitative Shedding Rates and Influencing Factors

Shedding rates determine the concentration of eDNA in the environment, which is critical for detecting species and interpreting results. These rates are not constant and are influenced by a complex interplay of biological and environmental factors.

Key Factors Influencing eDNA Shedding

Species Identity and Physiology: Significant differences in eDNA shedding rates exist between species, independent of biomass. Studies comparing salmonids, cyprinids, and sculpin have demonstrated distinct shedding quantities linked to their specific physiology and ecology [6].

Metabolic Activity and Energy Use: A positive correlation exists between energy use (measured as oxygen consumption) and the quantity of eDNA shed by freshwater fish. Higher metabolic rates lead to increased release of genetic material [6].

Animal Behavior and Activity Levels: Increased physical activity leads to higher eDNA shedding rates due to greater shearing forces between the animal's surface and the surrounding water, as well as increased volumes of water pumped over the gills [6]. Furthermore, stress can amplify tissue shedding rates by up to 100 times [5].

Life Stage and Body Size: The relationship between body size and mass-specific eDNA shedding is complex. Some studies, such as those on perch and eel, found lower mass-specific shedding rates in adults compared to juveniles, potentially due to the scaling of metabolic rates and surface area [6]. However, this finding has not been consistent across all species, as similar experiments with salmonids did not confirm this trend [6].

Environmental Conditions: Factors such as water temperature, pH, and microbial activity crucially affect the persistence of eDNA after shedding, influencing its detectability [5]. In aquatic environments, pH and temperature have been shown to significantly affect eDNA concentration [7].

Table 1: Factors Affecting eDNA Shedding Rates and Their Impacts

| Factor | Impact on eDNA Shedding | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Species Identity | Significant species-specific differences in shedding rates | Aquarium experiments with seven fish species revealed distinct shedding rates between taxa [6] |

| Metabolic Rate | Positive correlation between energy use and eDNA release | Oxygen consumption measurements correlated with dPCR eDNA quantification [6] |

| Animal Activity | Increased movement leads to higher eDNA shedding | Activity measured via snapshots every 30s showed positive correlation with eDNA quantities [6] |

| Body Size/Life Stage | Variable effects; often lower mass-specific shedding in adults | Contrasting results between perch/eel (lower in adults) and salmonids (no clear pattern) [6] |

| Stress | Can amplify shedding rates up to 100x | Tissue shedding rates dramatically increased under stress conditions [5] |

Quantitative Data on eDNA Persistence

The persistence of eDNA after shedding determines the temporal and spatial window for detection.

Aquatic Environments: eDNA can persist in water for approximately 7 to 21 days, with its half-life heavily dependent on local conditions [8]. One study reported a half-life ranging from 6.9 hours for anchovy DNA in California inshore waters to 71 hours in colder marine or freshwater systems [8]. Degradation occurs 1.6 times faster inshore than offshore [8].

Terrestrial and Sediment Environments: Soil eDNA is abundant, accounting for roughly 40% of the total DNA pool, with concentrations ranging from 0.03 to 200 µg/g [5]. In sediments, more than 90% of DNA is extracellular, and eDNA can bind to particles, protecting it from nuclease destruction [5]. In ferruginous sediments from Lake Towuti, eDNA concentration was approximately 0.5–0.6 µg/g in the surface layer, with concentration decreasing with depth [5].

Table 2: eDNA Concentration and Persistence Across Environments

| Environment | eDNA Concentration Range | Persistence/Temporal Dynamics | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic Water Column | 2.5-46 µg/L (mesotrophic) to 11.5-72 µg/L (eutrophic) [5] | Half-life: 6.9 hours to 71 hours [8]; 7-21 days overall [8] | Temperature, pH, UV radiation, microbial activity, turbidity [7] [8] |

| Sediments | 0.5-0.6 µg/g (surface layer) [5]; Up to 96.8 ± 19.8 µg/g in river sediments [5] | Long-term preservation; decreases with depth [5] | Particle adsorption, protection from nucleases, oxygen availability [5] |

| Soil | 0.03-200 µg/g [5] | Localized, can remain intact for extended periods [5] | Soil composition, organic matter, pH, microbial activity [5] |

| Air | Varies significantly with biomass and airflow | Temporal variation from hours to seasons; spatial variation vertically and horizontally [9] | Airflow, particle size, sampler efficiency, relative humidity [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Shedding and Transport

Controlled Aquarium Experiment Protocol

To investigate the effect of activity, energy use, and species identity on eDNA shedding, a controlled aquarium experiment can be implemented, adapting methodologies from Thalinger et al. [6].

Experimental Setup: House individual fish or controlled groups in aquaria with constant water flow to maintain consistent conditions and prevent eDNA accumulation. The system should include a sampling port for regular water collection.

Activity Monitoring: Record fish activity through automated snapshots (e.g., every 30 seconds) to quantify movement patterns. This provides a continuous behavioral metric.

Energy Use Measurement: Utilize an intermittent flow respirometer to measure oxygen consumption, which serves as a proxy for metabolic rate and energy use.

Water Sampling and eDNA Analysis: Collect water samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 3 hours). Filter samples using appropriate pore sizes (e.g., 0.7µm for higher yield in turbid water [7]). Preserve filters for DNA extraction and analyze target eDNA using absolute quantification methods like digital PCR (dPCR) for high specificity and accuracy [7] [6].

Data Analysis: Employ statistical models (e.g., Generalized Linear Mixed Models) to control for the effect of fish mass and test for correlations between eDNA quantity, fish activity, and energy use, while accounting for species-specific differences [6].

Field-Based Protocol for Terrestrial Mammal Detection

For assessing terrestrial mammal eDNA transport during rainfall events, a field-based protocol can be employed, as demonstrated in the Kiyotake River system study [7].

Study Design and Sampling Site Selection: Identify rivers or water bodies within catchments housing target terrestrial species. Select sampling points at varying distances from assumed entry points to assess transport dynamics.

Rainfall-Triggered Sampling: Collect water samples during and after rainfall events, which transport terrestrial eDNA to rivers via surface runoff. Characterize rainfall using parameters of Gaussian distribution (duration, intensity) [7].

Water Quality Measurement: Record concurrent environmental data including turbidity, pH, water temperature, and conductivity at each sampling instance.

Filtration and DNA Analysis: Filter water samples using different pore sizes (e.g., 0.7 µm and 2.7 µm) to compare efficiency, with smaller pores generally capturing more eDNA, particularly in turbid water [7]. Quantify target DNA (e.g., for Bos taurus) using species-specific dPCR assays [7].

Modeling and Interpretation: Use Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) to reveal the influence of environmental factors (e.g., rainfall duration, turbidity, pH, distance from source) on eDNA concentration [7]. This helps disentangle shedding, transport, and degradation processes.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for eDNA Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Filtration Materials | Glass fiber filters (0.7µm, 2.7µm pore sizes) [7]; HEPA F7 filters (for air sampling) [10] [9]; Plasma polymer-coated filters [10] | Capturing eDNA particles from water or air samples; coated filters can enhance eDNA binding efficiency. |

| Sampling Equipment | Portable water filtration pumps; Custom air extraction devices [10]; Active air samplers (e.g., impaction, impingement, filtering) [9] | Active collection of environmental samples for eDNA analysis. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit, QIAGEN) | Isolving high-quality DNA from complex environmental samples like filters, soil, or sediment. |

| PCR Reagents | Species-specific primers and probes; Digital PCR (dPCR) master mixes; Metabarcoding primer sets (e.g., 12S, 16S for vertebrates) [11] [12] | Targeted amplification and absolute quantification of eDNA; amplification of multiple species in a sample. |

| Sequencing Kits | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library preparation kits | Preparing eDNA libraries for metabarcoding or metagenomic shotgun sequencing. |

| Positive Controls | Synthetic oligonucleotides or cloned target DNA fragments | Validating PCR assay efficiency and specificity; serving as quantitative standards. |

Implications for Biodiversity Predictions and Monitoring

Understanding eDNA sources and shedding dynamics is not merely academic; it directly impacts the design, interpretation, and application of eDNA-based biodiversity research. Variations in shedding rates among species can influence the perceived community composition, potentially leading to over- or under-representation of certain taxa [6]. Furthermore, the transport of eDNA from its source complicates the precise localization of individuals, especially in aquatic environments where DNA can be detected kilometers from its origin [7] [5].

The integration of this knowledge is crucial for advancing conservation efforts. For instance, the high sensitivity of eDNA allows for the early detection of invasive species, such as Asian carp in Chicago waterways, enabling rapid response before populations become established [8]. Similarly, it facilitates the monitoring of endangered species, like the detection of crayfish plague to protect native white-clawed crayfish in the UK [8]. By accounting for the factors that affect shedding and persistence, researchers can move beyond simple presence-absence data toward more quantitative applications, such as estimating relative abundance and tracking population trends over time, ultimately fulfilling the promise of eDNA as a transformative tool for global biodiversity assessment.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has revolutionized ecological monitoring by enabling scientists to detect species from the genetic material they shed into their surroundings [13]. This non-invasive tool is transforming standard practices for characterizing aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity, with applications in conservation biology, invasion ecology, and biomonitoring [13] [14]. The technique leverages the fact that all organisms continuously shed genetic material through processes like skin cell sloughing, gamete release, and excretion, leaving a DNA trail in their environment [15]. Understanding the complex journey of this genetic material—from its shedding by organisms to its transport through various environmental media and eventual degradation—is fundamental to interpreting eDNA data accurately and leveraging its full potential for biodiversity predictions in research [13]. This technical guide examines the current state of knowledge regarding eDNA transport and fate across water, soil, and air, providing researchers with the foundational principles needed to design robust eDNA studies.

eDNA Shedding and Origin

The journey of eDNA begins when organisms shed genetic material into their environment. The majority of eDNA originates from released urine and faecal matter, shed epithelial cells from external mucous layers, and tissue from decomposing organisms [13]. Shedding rates exhibit significant variability even within species when accounting for biomass, creating uncertainty in the relationship between collected eDNA and actual organism abundance [13]. Multiple factors influence shedding rates, with studies documenting that stress can cause up to 100-fold increases in tissue shedding rates [13]. Additional biotic and abiotic variables including age, diet, water temperature, and community structure further contribute to substantial variation in the volume and rate of tissue shedding [13]. This inherent variability in shedding rates represents a critical source of uncertainty that must be considered in downstream analysis and ecological inference, as changes in eDNA abundance for a given species may reflect either alterations in shedding rates or actual changes in organism biomass or abundance [13].

Transport Mechanisms and Modeling Across Environmental Media

Aquatic Environments

In aquatic systems, eDNA undergoes complex transport dynamics influenced by water movement. In lotic systems (rivers and streams), eDNA is transported downstream from its point of origin, with detection distances varying based on current velocity, particle size, and degradation rates [13]. One study established an exponential quantitative relationship between eDNA concentration and golden mussel density, while identifying water temperature and pH as critical environmental factors influencing this relationship [16]. In lentic systems (lakes and ponds), eDNA distribution is primarily governed by diffusion and slow advective processes, creating concentration gradients around source organisms [13]. Marine environments present additional complexities due to stratification, salinity effects, and larger scales of water movement [13].

Table 1: Key Environmental Factors Influencing eDNA Fate in Aquatic Systems

| Factor | Effect on eDNA | Mechanism | Impact on Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increased decay rate | Enhanced microbial and enzymatic activity | Reduced detection window & distance [13] [16] |

| pH | Influences DNA adsorption to particles | Affects molecular charge and stability | Alters quantitative relationship with biomass [13] [16] |

| Turbidity | Variable effects on persistence | Particles may protect or expose DNA to degraders | Can extend or reduce detection capability [13] |

| UV Exposure | Accelerates degradation | Direct DNA damage through photolysis | Significantly reduces persistence [13] |

| Microbial Activity | Increases degradation | Enzymatic breakdown of DNA molecules | Seasonal variation in persistence [17] |

Soil and Vadose Zone Transport

eDNA transport through soil and the vadose zone (unsaturated soil above groundwater) exhibits complex behavior due to the porous nature of the medium. Research demonstrates that free DNA can be transported nearly non-selectively through variably saturated soils, behaving similarly to colloidal particles [18]. The transport mechanisms include advection-dispersion processes with interactions at solid-water interfaces (SWIs), air-water interfaces (AWIs), and air-water-solid (AWS) contact lines [18]. Under variably saturated transient flow conditions, additional complexity emerges through processes like film straining and entrapment in immobile water zones [18]. Modeling efforts have successfully simulated experimental synthetic DNA tracer transport using a two-site kinetic sorption model with one reversible and one irreversible attachment site, achieving strong correlation with observed data (R² = 0.824, NSE = 0.823) [18]. The concentration peaks observed in DNA tracer transport through soils are likely related to the movement of AWS contact lines that mobilize and carry DNA under variably saturated transient flow conditions [18].

Airborne Transport and Cross-Medium Transfer

Recent research has demonstrated that eDNA can transfer between environmental compartments, particularly from water to air. A 2025 study provided the first systematic evidence that passive air sampling can detect aquatic eDNA from spawning salmon in air samples collected above water surfaces [19]. The study revealed that although airborne eDNA concentrations were approximately 25,000 times more dilute than in water, they still exhibited covariance with both water eDNA concentrations and visual fish counts [19]. Natural physical processes facilitating this cross-medium transfer include evaporation, bubble-burst aerosolization from water turbulence, and biological processes such as splashes and leaping fish [19]. This water-to-air eDNA transfer enables monitoring of aquatic organisms using passive air collection methods, opening new possibilities for non-invasive biomonitoring in remote or resource-limited settings [19].

Degradation Processes and Rates

The accurate biological interpretation of eDNA signals requires understanding degradation processes and rates across environmental media. eDNA decay involves multiple processes often combined into a single decay rate estimate, with reported half-lives ranging from 0.7 hours in multi-species assays to 71.1 hours in Antarctic icefish [13]. Complex models of DNA decay where rates decrease over time often better explain aquatic eDNA decay than monophasic models, potentially corresponding to multiphasic mechanisms involved in tissue and eDNA decay as different cellular compartments exhibit different liabilities [13].

Biological Degradation Mechanisms

Cellular degradation begins immediately after shedding, with cells from intestinal or mucosal epithelial tissues often starting to degrade via apoptosis (programmed cell death) before being shed [13]. During apoptosis, nuclear DNA is tightly packed and hydrolyzed into approximately 180 bp fragments, while mitochondrial DNA is randomly fragmented during late-stage apoptosis [13]. When apoptosis is incomplete, a switch to necrosis (uncontrolled cell death) may occur, potentially allowing longer DNA fragments to survive [13]. In the environment, free DNA is typically degraded by bacteria and extracellular nucleases into smaller, unpredictable fragments [13]. eDNA persistence is therefore directly linked to microbial activity, trophic state, and extracellular nuclease concentrations [13]. Seasonal variability in eDNA persistence has been documented in marine systems, where rapid phosphate turnover during periods of phosphate limitation can reduce d-eDNA (dissolved eDNA) turnover to less than 5 hours [17].

Abiotic Degradation Factors

DNA undergoes spontaneous decomposition through several chemical pathways, with rates heavily influenced by environmental conditions. At 25°C in a neutral buffer, DNA is remarkably stable, with estimated half-lives for various degradation processes including phosphodiester bond cleavage (31,000,000 years), depurination (70-180 years), and deoxycytidine deamination (120 years) [13]. However, environmental conditions dramatically accelerate these processes, with temperature being particularly influential—to the extent that thermal history may be more important than material age when successfully amplifying ancient DNA [13]. Additional environmental factors including pH, salinity, oxygen concentration, and sunlight exposure further impact degradation rates across different ecosystems [13] [17].

Table 2: Experimental eDNA Decay Rates Across Environmental Conditions

| Environment | Target Organism | Half-Life | Key Influencing Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine System | Various taxa | Seasonal variation: hours to >1 month | Phosphate limitation, microbial utilization | [17] |

| Freshwater | Multiple species | 0.7 hours | Temperature, pH, turbidity | [13] |

| Antarctic Freshwater | Icefish | 71.1 hours | Low temperature, reduced microbial activity | [13] |

| Vadose Zone | Synthetic DNA tracer | ~10% in 10 days | Low microbes/DNase in basaltic tephra | [18] |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Aquatic eDNA Sampling Protocol

Standardized water sampling for eDNA analysis involves collecting water samples in a manner that minimizes contamination and preserves DNA integrity. The following protocol represents current best practices:

Sample Collection: Collect water samples using sterile containers, avoiding sediment disturbance. For quantitative studies, standardize volume (typically 1-2 L) and collection depth [14].

Filtration: Immediately filter water samples through appropriate pore size membranes (typically 0.22-0.45 μm) to capture eDNA particles. Various filter types including mixed cellulose ester (MCE), glass fiber (GF), and polycarbonate (PC) are used depending on water turbidity and target analysis [19] [20].

Preservation: Preserve filters in DNA stabilization buffers such as DNA/RNA Shield or ethanol to prevent degradation during transport and storage [19].

Extraction: Extract DNA using membrane-based protocols or commercial kits designed for environmental samples, incorporating controls to monitor contamination [21].

Analysis: Analyze extracted eDNA using quantitative PCR (qPCR) for single species detection or metabarcoding for community-level analysis, employing appropriate marker genes (e.g., COI for animals, 18S for eukaryotes) [19] [22].

Airborne eDNA Sampling Methodology

A recent pioneering study systematically tested methods for sampling eDNA at the air-water interface using passive collectors:

Sampler Deployment: Deploy passive air samplers approximately 3 meters above the water surface to minimize splash contamination while capturing airborne DNA particles [19].

Filter Types: Utilize multiple filter types to compare capture efficiency:

- Gelatin filters: Effective for capturing airborne particles while maintaining viability

- PTFE filters: High durability, widely used in active air sampling

- MCE filters: Traditionally employed for water filtration, tested for airborne application [19]

Configuration: Suspend filters in custom 3D-printed "honeycomb" puck filter holders with collection surfaces oriented vertically to capture airborne DNA particles driven by gravitational settling [19].

Alternative Collector: Include an open container of deionized water (25×30×10 cm) with approximately 750 cm² surface area positioned horizontally to capture settling particles [19].

Exposure Time: Deploy collectors for approximately 24 hours, then recover using sterile forceps and immediately preserve in DNA/RNA Shield [19].

Soil eDNA Sampling and Vadose Zone Transport Studies

Research on synthetic DNA tracer transport through the vadose zone has established rigorous methodologies:

Tracer Design: Design synthetic DNA tracers (e.g., 200-nucleotide sequences) using random sequence generators, then verify specificity against known genomes using NCBI's Primer-BLAST tool [18].

Experimental Setup: Conduct experiments in controlled systems such as 1 m³ sloped lysimeters packed with defined porous media (e.g., freshly crushed basaltic tephra with "loamy sand" texture) [18].

Tracer Injection: Introduce DNA tracers alongside conservative tracers (e.g., deuterium) under transient variably saturated flow conditions mimicking natural wetting-drying cycles [18].

Sample Collection: Collect effluent samples at timed intervals to construct breakthrough curves, comparing DNA tracer recovery with conservative tracers [18].

Model Validation: Simulate transport using colloid transport models (e.g., HYDRUS-2D with Schijven and Šimůnek two-site kinetic sorption model) to validate understanding of retention and remobilization mechanisms [18].

Figure 1: Pathways and Processes in eDNA Transport and Fate

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for eDNA Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Materials | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filtration Media | Mixed Cellulose Ester (MCE), Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Gelatin filters, Glass Fiber (GF) | Capture eDNA particles from environmental samples | Filter choice affects capture efficiency; varies by application (water/air) [19] [20] |

| Preservation Reagents | DNA/RNA Shield, Ethanol (95%), Long-term storage buffers | Stabilize DNA between collection and extraction | Critical for preventing degradation; choice affects downstream analysis [19] [21] |

| Extraction Kits | Membrane-based protocols, Acroprep glass fiber/Bio-Inert membrane plates, Commercial kits | Isolate DNA from environmental samples | Efficiency varies with sample type; includes contamination controls [21] |

| Amplification Reagents | PCR/qPCR master mixes, Metabarcoding primers (COI, 18S, etc.), Positive controls | Target species-specific sequences or multiple taxa | Primer selection critical for taxonomic resolution; controls essential [22] [21] |

| Synthetic Tracers | Custom-designed oligonucleotides (e.g., 200-nucleotide sequences) | Hydrological tracing, transport studies | Verify specificity against known genomes; length affects degradation [18] |

Implications for Biodiversity Monitoring and Conservation

Understanding eDNA transport and fate is crucial for its application in biodiversity monitoring and conservation policy. eDNA technology supports global biodiversity assessment through its ability to provide standardized, scalable, and cost-effective monitoring that can be implemented across diverse ecosystems [14]. The technology directly addresses data needs outlined in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework by providing information on: (1) the state of biodiversity across scales and systems; (2) spatial movements of organisms and temporal changes in species abundance; and (3) how ecosystems respond to anthropogenic change [14]. Recent demonstrations of nationwide biodiversity censuses using pre-existing air quality monitoring networks highlight how airborne eDNA can transform industrial infrastructure into global wildlife monitoring systems, enabling biodiversity assessment at previously impossible scales [15]. However, accurate interpretation of these data requires careful consideration of the transport and degradation processes outlined in this document to avoid erroneous ecological inferences.

Figure 2: eDNA Sampling Methodologies Across Environmental Media

The journey of eDNA through water, soil, and air involves complex processes of shedding, transport, and degradation that span environmental media. The emerging understanding of cross-medium eDNA transfer, particularly from water to air, opens new possibilities for non-invasive monitoring of aquatic systems [19]. Advances in modeling eDNA transport, especially through challenging environments like the vadose zone, provide increasingly sophisticated tools for predicting eDNA fate [18]. However, significant context-dependency in eDNA persistence and transport necessitates environment-specific calibration for robust biological interpretation [13] [19]. Future research directions should focus on quantifying eDNA transport and fate across diverse ecosystems, standardizing sampling methodologies to enable global comparison, and integrating eDNA data with traditional monitoring approaches to validate and strengthen biodiversity assessments. As these methodological challenges are addressed, eDNA technology promises to revolutionize our ability to track and protect global biodiversity at scales necessary to address the current conservation crisis.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has revolutionized ecological monitoring by enabling the detection of species from genetic material shed into their surroundings. Understanding the persistence and degradation dynamics of eDNA is fundamental to interpreting detection data accurately and avoiding false positives from legacy DNA or false negatives from rapid degradation. The duration eDNA remains detectable is not a fixed value but a complex function of interacting environmental and biological processes that influence its production, state, and decay [13]. This technical guide synthesizes current research on eDNA persistence, focusing on the mechanisms governing its degradation and the experimental approaches used to quantify its lifespan in aquatic environments, framing these findings within the broader context of biodiversity prediction research.

The Dynamics of eDNA in the Environment

The Multiple States of eDNA

When organisms shed DNA into the water column, the resulting extraorganismal eDNA exists in a mixture of physical states, each with specific implications for its persistence and detectability [23]. The four principal states are:

- Intracellular DNA: DNA contained within whole cells shed from the organism (e.g., skin, intestinal cells).

- Intraorganellar DNA: DNA encapsulated within organelles, such as mitochondria or chloroplasts, released from cells.

- Particle-Adsorbed DNA: Extracellular DNA that has become bound to the surfaces of organic or mineral suspended particles.

- Dissolved DNA: Truly extracellular, free DNA molecules suspended in the water column.

The state of eDNA significantly influences its decay rate. Intracellular and intraorganellar DNA are initially protected from degradation by their surrounding membranes, while dissolved DNA is most vulnerable to enzymatic and chemical breakdown [23] [13]. The conversion between these states is governed by environmental parameters. For instance, cell lysis—the rupture of cells releasing their contents—is accelerated by osmotic stress, microbial enzyme activity, and temperature [23]. Conversely, adsorption of dissolved DNA to particles is controlled by electrostatics, which are modulated by water chemistry factors like pH, ionic strength, and the concentration of divalent cations such as Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ [23]. In marine environments with high salinity and positively charged mineral surfaces, a greater proportion of eDNA is expected to be in the particle-adsorbed state, which may offer some protection against degradation.

Key Processes and Conversion Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the primary states of eDNA and the processes that govern their conversion and degradation in the aquatic environment.

Factors Governing eDNA Degradation

Abiotic Factors

Abiotic environmental conditions are primary drivers of eDNA decay rates. Their influence is often mediated through their effect on the biological activity of microbes that produce DNA-degrading enzymes.

- Temperature: This is consistently identified as one of the most critical factors. Higher temperatures accelerate both enzymatic and spontaneous chemical degradation of DNA. A global meta-analysis confirmed that eDNA detection probability decreases in hotter regions and seasons [24]. Furthermore, temperature influences eDNA production (shedding), adding complexity to its net effect on concentration [25].

- pH: Acidic conditions promote the depurination of DNA, a spontaneous hydrolysis reaction that breaks the sugar-phosphate backbone, leading to strand cleavage [13]. One study found a temporal gradient of pH to be a significant covariable influencing eDNA persistence [26].

- UV Radiation: Solar ultraviolet light damages DNA by causing cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers between adjacent nucleotides, rendering the DNA unamplifiable. The combined negative effect of temperature and UV radiation significantly reduces eDNA detection [24].

- Salinity: The effect of salinity is complex. While salt can have a preservative effect on DNA in some contexts, evidence suggests that eDNA detection probability is generally lower in marine ecosystems than in freshwater systems [24] [27]. The higher ionic strength in marine environments may attenuate electrostatic repulsion, facilitating DNA adsorption to particles and potentially altering its availability for degradation processes [23].

Biotic Factors

Biological activity is a major driver of eDNA degradation.

- Microbial Activity: The abundance and metabolic activity of bacteria and other microorganisms are paramount. Microbes produce extracellular nucleases that efficiently cleave DNA molecules for nutrient assimilation [13]. Factors that stimulate microbial activity, such as higher temperatures and organic nutrient loads, consequently accelerate eDNA decay.

- Enzyme Concentration: The presence of extracellular DNases directly and rapidly degrades dissolved DNA. The concentration of these enzymes in the water is a key determinant of decay rate [13].

- Target Species and DNA Characteristics: Degradation rates can be species-specific, influenced by differences in the composition and shedding of biological materials [26] [13]. Furthermore, the target gene fragment length plays a role, with shorter fragments generally persisting longer than longer ones [13].

Quantitative Decay Rates Across Environments

Experimental studies report eDNA decay rates using first-order exponential decay models, often summarized by the decay rate constant (k) or the eDNA half-life (the time required for the eDNA concentration to reduce by half). The table below synthesizes half-life estimates from key studies.

Table 1: Measured eDNA Half-Lives in Various Aquatic Environments

| Environment / Condition | Target Organism | Approximate Half-Life (Hours) | Key Influencing Factors | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine - Inshore | Fish & Crab | ~21 - 48 | Salinity, biotic correlates | [26] |

| Marine - Offshore | Fish & Crab | ~26 - 46 | Slower decay than inshore | [26] |

| Marine (General) | Sessile Invertebrates | eDNA: ~94; eRNA: ~13 | Similar decay rate constants | [28] |

| Freshwater - Tadpole Mesocosms | Tadpoles | Varies widely | Temperature, pathogen load | [25] |

| Modeled Marine Coastal | General | Varies with temperature | Tidal forcing, temperature | [27] |

These quantitative values demonstrate the high variability of eDNA persistence. The half-life of marine fish and crab eDNA can range from 21 to 48 hours in inshore environments, offering a potential detection window of about 2 days under specific conditions [26]. A striking finding is the persistence of environmental RNA (eRNA), which was detected for up to 13 hours, contrary to the assumption that it degrades much faster than eDNA [28]. This has implications for distinguishing living from dead organisms.

Table 2: Impact of Environmental Factors on eDNA Detection and Persistence

| Factor | Effect on eDNA Persistence | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| High Temperature | Decreases persistence | Increases microbial/enzymatic activity and spontaneous chemical decay. |

| Low pH | Decreases persistence | Promotes depurination and other acid-driven hydrolysis reactions. |

| High UV Exposure | Decreases persistence | Causes direct photodamage to DNA strands. |

| High Salinity | Decreases detection probability | Modifies DNA-state interactions and microbial communities. |

| High Microbial Load | Decreases persistence | Increases concentration of extracellular nucleases. |

| Particle Adsorption | Can increase or decrease | Can protect from nucleases but facilitate sedimentation. |

Experimental Protocols for Studying eDNA Decay

Mesocosm Experimental Design

Controlled mesocosm experiments are a standard approach for quantifying eDNA decay rates while manipulating environmental variables.

- Protocol Overview: Organisms are placed in aquaria containing filtered water from the environment of interest. After a shedding period (e.g., 36-48 hours), the organisms are removed, and water samples are collected repeatedly over time to track the decrease in eDNA concentration [26] [28] [25].

- Key Controls: To ensure reliability, experiments include no-template controls (NTCs) in PCR to detect contamination and no-treatment controls (water with no organisms) to account for background eDNA or contamination [26]. Inhibition tests are performed on DNA extracts to confirm PCR efficiency.

- Quantification: Quantitative PCR (qPCR) or droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) is used to measure target eDNA concentration at each time point. The data is then fitted to an exponential decay model (e.g., ( C(t) = C_0 e^{-kt} )) to calculate the decay rate constant k and half-life [26] [27] [28].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for eDNA Decay Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Filtered Environmental Water | Serves as the experimental medium, maintaining natural microbial and chemical conditions. |

| Species-Specific qPCR/ddPCR Assays | For absolute quantification of target eDNA concentration over time. Requires validated primers/probes. |

| Laboratory Aquaria/Tanks | Controlled mesocosms for containing organisms and water during shedding and decay phases. |

| Sterile Water Sampling Equipment | (e.g., vacuum pumps, filter funnels, sterile bottles) For consistent, contamination-free water collection. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | (e.g., silica-membrane based kits) For isolating eDNA from water filters or precipitates. |

| PCR Reagents & Plate Sealer | For preparing and running qPCR/ddPCR reactions. |

| DNase/RNase-free Filters | (e.g., 0.22µm pore size) For sterilizing water and capturing eDNA from water samples. |

| Digital Droplet Reader (for ddPCR) | To read and quantify the results of a ddPCR reaction, which partitions samples into nanoliter droplets. |

The finite persistence of eDNA has profound implications for its use in biodiversity prediction and conservation. A key challenge is the spatial and temporal uncertainty inherent in a positive detection. In marine systems, modeling studies indicate that eDNA signals can be transported significant distances (median dispersal of 2.27 to 14.14 km in one coastal model), primarily controlled by tidal excursion and water temperature influencing decay [27]. This means a detection may not pinpoint the exact location of the source organism. Similarly, detecting eDNA from a species that has recently left an area or died (a "false positive") is a risk, though the discovery of persistent eRNA offers a potential tool to better confirm the presence of living organisms [28].

Understanding decay dynamics is therefore critical for designing robust monitoring programs. Sampling design must account for local hydrodynamic conditions and seasonal variations in temperature that affect the "detectable footprint" of a species [27]. Furthermore, the multiphasic nature of eDNA decay—where different states degrade at different rates—suggests that simple exponential decay models may need refinement for more accurate spatio-temporal predictions [13].

In conclusion, the persistence of eDNA in the environment is a dynamic interplay of physical, chemical, and biological processes. While typical half-lives range from hours to days in the water column, this is highly dependent on local conditions. For researchers using eDNA to predict biodiversity, acknowledging and accounting for these complexities is not optional—it is essential for transforming eDNA from a powerful detection tool into a reliable, quantitative pillar of conservation science.

From Sampling to Sequencing: A Practical Guide to eDNA Workflows and Applications

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has revolutionized biodiversity monitoring by providing a sensitive, non-invasive tool for detecting species across aquatic ecosystems. The reliability of eDNA data is fundamentally dependent on the sampling strategy employed, with active filtration, water collection, and passive traps representing the core methodological approaches. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these strategies, detailing their operational parameters, performance characteristics, and optimal application contexts. Within the broader thesis of eDNA's role in biodiversity predictions, we demonstrate how sampling methodology influences detection sensitivity, community composition assessment, and ultimately, the ecological inferences drawn from eDNA data. We present standardized protocols, quantitative performance comparisons, and practical implementation frameworks to guide researchers in selecting and applying these methods effectively for conservation and research applications.

Accurate monitoring of species distributions is crucial for evaluating extinction threats, assessing environmental health, surveying for exotic species, and planning effective conservation actions [29]. Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling has emerged as a transformative approach that alleviates disadvantages associated with traditional observational and capture-based strategies, including organism disturbance and bias caused by differing levels of taxonomic expertise [29]. eDNA describes the genetic material of subterranean and aquatic species present in environmental samples [20], enabling detection without direct observation or capture.

The choice of eDNA sampling strategy significantly impacts detection probability, community composition assessment, and biodiversity estimates [29]. Sampling approaches must account for eDNA heterogeneity throughout water bodies, as eDNA generally occurs in low concentrations and dilutes with distance from its source [29]. This technical guide examines the three principal eDNA sampling strategies—active filtration, water collection, and passive traps—within the context of advancing biodiversity prediction research. We provide a systematic framework for method selection based on study objectives, environmental conditions, and practical constraints.

Comparative Analysis of Sampling Strategies

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary eDNA sampling strategies:

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of eDNA Sampling Strategies for Biodiversity Assessment

| Strategy | Detection Performance | Optimal Use Cases | Equipment Requirements | Processing Time | Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Filtration | Higher likelihood of species detection with 5µm vs. 0.22µm filters [29]; More sensitive for rare taxa [30] | Turbid environments; Target species detection; Quantification studies | Pumps, tubing, filter housings, membranes [29] | 10-40 minutes per replicate [30] | Higher equipment costs; Laboratory charges per filter [29] |

| Water Collection | Similar sensitivity to filtration for some applications [31] | Preserving samples for later analysis; Highly turbid waters | Collection containers, coolers, preservatives [32] | Rapid collection but requires lab processing | Lower field equipment costs but higher transport and lab costs |

| Passive Traps | Detected 11-37 fish species vs. 19-32 for active filtration [31]; Effective in 5 minutes to 24 hours [31] | Large-scale surveys; Remote locations; High-replication studies [31] | Filter membranes, holders, deployment apparatus [19] | Minimal active time; Deployment duration varies | Lower equipment and personnel requirements [30] |

Table 2: Method Performance Across Ecosystem Types

| Strategy | Freshwater Systems | Marine Systems | Turbid Waters | Clear Waters | Flowing Water | Lentic Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Filtration | Excellent [33] | Excellent [34] | Challenging (clogging) [29] | Optimal | Good with adjustment for flow [32] | Excellent |

| Water Collection | Good with preservation [32] | Good with preservation | Excellent for high particulates | Good | Limited by transport | Good |

| Passive Traps | Effective [31] | Variable (better in temperate) [34] | Not affected by particulates | Effective | Limited in fast flow | Optimal |

Active Filtration Methodology

Principles and Mechanisms

Active filtration involves forcing water through a membrane to concentrate eDNA particles, enabling processing of larger water volumes, increased eDNA yield, and in situ processing relative to alternative capture methods [29]. This approach enhances detection sensitivity for rare taxa by concentrating genetic material from substantial water volumes [30]. The technique's effectiveness depends on filter pore size, water volume processed, and the physicochemical properties of the water matrix.

Experimental Protocol for Active Filtration

Equipment and Reagents

- Filtration apparatus: Peristaltic pump, vacuum pump, or manual syringe system [29]

- Filter membranes: Sterivex 0.22µm, Smith-Root 5µm, or other pore sizes depending on application [29]

- Sterile containers: For water collection if filtering in laboratory

- Personal protective equipment: Disposable gloves, safety glasses

- Decontamination supplies: 10% bleach solution, DNA-free water, ethanol [32]

- Sample preservation: Desiccant, DNA/RNA Shield, or silica gel [32]

Field Procedures

- Site preparation: Select sampling locations representative of the water body, typically from multiple points [29]. For streams, collect at the most downstream location first to prevent cross-contamination [32].

- Equipment decontamination: Sterilize all equipment with 10% bleach solution followed by rinsing with DNA-free water before sampling and between sites [32].

- Water collection: Collect water from just below the surface (<20 cm) using sterile containers, or filter directly from the water column [29].

- Filtration process: Pass water through filter membrane using chosen pumping mechanism. Record volume filtered and any clogging issues [32].

- Filter preservation: Remove filter from housing using sterile forceps and place in sterile vial with desiccant or preservation buffer [32].

- Sample documentation: Label samples with date, location, volume filtered, filter type, and other relevant metadata [32].

- Quality control: Collect field blank samples using distilled water to assess potential contamination [32].

- Storage: Store samples in refrigerator before transport to lab, then transfer to -80°C freezer for long-term preservation [32].

Technical Considerations

- Pore size selection: Larger pore sizes (5-10µm) enable larger water volumes in turbid conditions and may improve detection probabilities for some amphibian species [29].

- Volume optimization: Filter as large a volume as practical; 5-L samples are common, though volume depends on particulate load [32].

- Replication: Collect multiple filters per site to account for eDNA heterogeneity and increase detection probability [29].

Applications in Biodiversity Prediction

Active filtration provides quantitative data that can be correlated with species abundance when properly calibrated [19]. This strategy is particularly valuable for detecting rare and invasive species [20], assessing community composition through metabarcoding [29], and monitoring sensitive ecosystems with minimal disturbance.

Water Collection Methodology

Principles and Mechanisms

Water collection involves gathering bulk water samples for later processing in laboratory settings. This approach separates sample collection from filtration, providing flexibility in field operations and making it suitable for conditions where immediate filtration is impractical. The method preserves the complete eDNA signal present in the collected water volume, though it may require careful handling to prevent degradation during transport.

Experimental Protocol for Water Collection

Equipment and Reagents

- Water collection containers: Sterile, single-use bottles or containers [32]

- Cooling equipment: Coolers, ice packs, or refrigeration units [32]

- Preservatives: DNA/RNA stabilization solutions if immediate processing isn't possible

- Transport containers: Secure, leak-proof packaging for sample transport

- Filtration equipment: For laboratory-based processing of collected water

Field Procedures

- Site selection: Choose sampling locations that represent the target habitat, similar to active filtration approaches.

- Container preparation: Use pre-sterilized containers to prevent contamination.

- Water collection: Collect water from below the surface, avoiding sediment disturbance.

- Preservation: Add stabilizers if needed, or immediately cool samples to 4°C.

- Transport: Transfer samples to laboratory facilities under cooled conditions.

- Laboratory processing: Filter water samples under controlled conditions within 24-48 hours of collection.

Technical Considerations

- Holding times: Process samples as quickly as possible to minimize eDNA degradation.

- Volume requirements: Collect sufficient water for planned analyses, typically 1-5 liters per sample.

- Temperature control: Maintain cold chain from collection to processing to preserve eDNA integrity.

Applications in Biodiversity Prediction

Water collection is particularly valuable for sampling in highly turbid conditions where immediate filtration is challenging [29]. This method also enables standardized processing across multiple sites when laboratory facilities are accessible and supports studies requiring complex preservation approaches.

Passive Traps Methodology

Principles and Mechanisms

Passive eDNA collection involves submerging materials directly in the water column to capture eDNA without active pumping [34]. This approach relies on natural water movement to bring eDNA particles into contact with collection surfaces, where they adhere through electrostatic attraction, physical entrapment, or absorption [31]. Passive sampling eliminates the need for filtration equipment and can enable greater replication at lower cost [30].

Experimental Protocol for Passive Traps

Equipment and Reagents

- Collection materials: Filter membranes (cellulose ester, nylon, cotton rounds, sponge) [31] [34]

- Deployment apparatus: Holders, frames, or securing devices [31]

- Preservation supplies: DNA/RNA Shield, sterile forceps, collection vials [19]

- Personal protective equipment: Disposable gloves to prevent contamination

Field Procedures

- Material preparation: Load collection materials into deployment apparatus using sterile techniques.

- Site deployment: Submerge passive collectors in the water column, securing them in place [31].

- Exposure period: Leave collectors in place for predetermined time (5 minutes to 24 hours) [31].

- Sample retrieval: Carefully collect materials using sterile forceps to minimize eDNA loss.

- Preservation: Immediately place collectors in preservation buffer or cool storage.

- Documentation: Record deployment location, duration, depth, and environmental conditions.

Technical Considerations

- Material selection: Cellulose ester membranes generally outperform charged nylon in tropical waters [34]. Cotton rounds yield greater eDNA than research-grade filters in some applications [30].

- Exposure duration: Short deployments (as little as 5 minutes) can be effective, with longer periods not necessarily increasing species detection [31].

- Replication: Deploy multiple passive samplers per site to account for spatial heterogeneity in eDNA distribution.

Applications in Biodiversity Prediction

Passive traps enable extensive spatial replication for mapping species distributions and detecting rare organisms [30]. They are particularly valuable in remote areas where equipment portability is essential [30] and for long-term monitoring programs requiring cost-effective sampling [34]. Recent advances demonstrate that passive collection can even detect aquatic eDNA transferred to air at the water-air interface [19].

Integrated Workflow and Experimental Design

Method Selection Framework

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate eDNA sampling strategies based on research objectives and environmental constraints:

Quality Assurance and Control

Robust eDNA studies incorporate multiple quality control measures at each stage of the sampling process:

- Field blanks: Collect samples using distilled water to monitor field contamination [32].

- Equipment sterilization: Clean equipment with 10% bleach solution between sites [32].

- Negative controls: Include extraction and amplification controls to identify laboratory contamination.

- Positive controls: Use synthetic DNA sequences to verify assay sensitivity.

- Replication: Collect multiple samples per site to account for spatial heterogeneity and estimate detection probabilities [29].

Data Interpretation Considerations

Each sampling method influences the resulting biodiversity assessments:

- Active filtration: Provides volume-standardized data suitable for quantitative models but may underrepresent diversity in turbid waters if filters clog prematurely [29].

- Water collection: Captures the complete eDNA complement but requires careful handling to prevent degradation.

- Passive traps: Enables extensive spatial coverage but may yield lower DNA quantities requiring optimized molecular analysis [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for eDNA Sampling and Their Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterivex 0.22µm filters | Fine-pore filtration for small eDNA particles | Active filtration in clear waters [29] | Prone to clogging in turbid water [29] |

| Smith-Root 5µm filters | Larger-pore filtration for turbid systems | Wetland and river sampling [29] | Enables larger water volumes; better detection for some species [29] |

| Cellulose ester membranes | Passive eDNA collection | Marine and freshwater passive sampling [31] [34] | Effective in both temperate and tropical systems [34] |

| Chitosan-coated cellulose | Enhanced DNA binding via electrostatic attraction | Passive collection optimization [31] | Polycation polymer efficiently binds anionic DNA [31] |

| Cotton rounds | Low-cost passive collection material | Large-scale surveys; remote monitoring [30] | Higher eDNA yields than some research-grade filters [30] |

| DNA/RNA Shield | eDNA preservation at room temperature | Field stabilization of samples [19] | Prevents degradation during transport |

| Gelatin filters | Air-water interface eDNA collection | Detecting aquatic eDNA in air [19] | Effective for passive air sampling above water bodies [19] |

| PTFE filters | Airborne eDNA collection | Detecting water-to-air eDNA transfer [19] | High durability for passive air sampling [19] |

The selection of eDNA sampling strategy—active filtration, water collection, or passive traps—profoundly influences biodiversity detection and ecological interpretation. Active filtration provides high sensitivity for rare species detection, water collection offers practical advantages in challenging field conditions, and passive traps enable unprecedented replication for comprehensive biodiversity assessment. Within the broader context of biodiversity prediction research, methodological choices must align with specific research questions, environmental constraints, and analytical resources. As eDNA science continues to evolve, methodological standardization and cross-validation will enhance data comparability across studies and ecosystems, ultimately strengthening the role of eDNA analysis in conservation decision-making and ecological forecasting.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis has emerged as a revolutionary tool for monitoring biodiversity, enabling researchers to detect species through genetic material they shed into their environment [5]. This molecular approach offers a sensitive, non-invasive alternative to traditional survey methods, which can be time-consuming, costly, and potentially harmful to vulnerable species and their habitats [35] [5]. The core of eDNA analysis lies in two principal laboratory techniques: quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for targeting specific species and metabarcoding for assessing entire biological communities. The decision between these methods is critical and hinges on the study's fundamental aims—whether the requirement is for sensitive detection and quantification of particular species or for a comprehensive community profile [36] [37]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of both methodologies, framing them within the broader context of using eDNA to predict and monitor biodiversity.

Fundamental Principles of qPCR and Metabarcoding

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Target Species

qPCR, also known as real-time PCR, is a species-specific detection method. It relies on primers and a fluorescent probe designed to bind exclusively to a unique DNA sequence of a target organism [37]. The core output, the cycle threshold (CT), indicates the amplification cycle at which a significant amount of target DNA is detected, with lower CT values correlating with higher initial DNA quantities [35]. This relationship allows qPCR to be not only a presence/absence tool but also a semi-quantitative method for estimating DNA concentration in the original sample [36] [38].

Metabarcoding for Whole Communities

Metabarcoding employs universal primers that target a conserved genetic region across a broad taxonomic group (e.g., all fishes or invertebrates). This amplified region contains hyper-variable sequences that allow for species identification through high-throughput sequencing (HTS) [35] [39]. A key advantage is its ability to detect hundreds to thousands of taxa from a single environmental sample, providing a extensive view of the biological community [35] [40]. However, the quantitative relationship between the number of DNA sequences (reads) generated for a species and its actual abundance or biomass is influenced by multiple factors, including primer bias and PCR competition [38].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Comparison of qPCR and Metabarcoding

| Feature | qPCR (Target Species) | Metabarcoding (Whole Communities) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Detect and/or quantify a pre-defined species | Comprehensive profiling of a taxonomic community |

| Primer Design | Species-specific primers and probe | Universal primers for a broad taxonomic group |

| Typical Output | Cycle threshold (CT) value; DNA copy number | List of species and their sequence read counts |

| Key Strength | High sensitivity for low-abundance targets [36] | Holistic, discovery-based approach without the need for prior species knowledge [35] |

| Inherent Limitation | Requires prior knowledge of target species; limited to few species per assay | Quantitative inferences can be biased; more complex data processing [36] [38] |

Comparative Performance: Sensitivity, Quantification, and Community Data

The choice between qPCR and metabarcoding involves navigating a trade-off between the sensitivity needed for detecting specific species and the value of obtaining comprehensive community data.

Detection Sensitivity

Studies directly comparing the two methods consistently show that qPCR generally achieves higher detection probabilities for individual target species [36] [39]. This heightened sensitivity makes qPCR particularly suited for detecting rare, endangered, or invasive species where false negatives can have significant consequences [36]. For instance, a hierarchical modelling study across multiple species and datasets concluded that qPCR was more sensitive than metabarcoding [36]. Similarly, a study on small pelagic fish in the open ocean found that while both methods produced congruent distribution patterns, the detection rate for qPCR was consistently higher than for metabarcoding [39].

Quantitative Potential

Both methods show correlations between their output metrics and species abundance or biomass, but their quantitative applications differ.

- qPCR: The relationship between CT value and species abundance/biomass is well-documented, making it a robust tool for comparative abundance studies [36] [38].

- Metabarcoding: Traditional read counts are not directly quantitative. However, advanced techniques like the qMiSeq approach are overcoming this limitation. This method involves adding internal standard DNAs to each sample to create a sample-specific regression line, converting sequence reads into estimated DNA copy numbers [38]. Studies using qMiSeq have demonstrated significant positive relationships between eDNA concentrations and both the abundance and biomass of captured fish, confirming its potential for quantitative community assessment [38].

Community Insights

The principal advantage of metabarcoding is its ability to illuminate the entire biological community from a single sample. A single metabarcoding analysis can reveal co-occurring species, potential predator-prey relationships, and the broader ecological network, providing context for the target species that a single-species qPCR assay cannot [35]. For example, a study on the parasitic gill louse (Salmincola edwardsii) found that metabarcoding detected the target parasite with accuracy comparable to qPCR, while simultaneously revealing a vast community of over 2,600 invertebrate taxa from the same eDNA samples [35].

Table 2: Summary of Comparative Studies between qPCR and Metabarcoding

| Study Focus & Citation | Key Finding on Detection Sensitivity | Key Finding on Quantification/Performance | Community Insight Provided by Metabarcoding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gill Louse Parasite [35] | No evidence that occupancy or detection probabilities differed between methods. | Number of metabarcoding reads negatively predictive of qPCR CT values. | Detected over 2,600 invertebrate taxa, revealing the broader biological community. |

| Multiple Species (Platypus, Fish, Amphibian) [36] | qPCR achieved higher detection probabilities across species and datasets. | Sensitivity differences were impacted by methodological thresholds for a "true positive." | Not the focus of the study; qPCR was determined preferable for high detection probability of targets. |

| Small Pelagic Fish [39] | Detection rate using qPCR was always higher than with metabarcoding. | A positive correlation was found between results from qPCR and metabarcoding. | Metabarcoding can provide fish community structure, but the study recommended combined usage. |

| River Fish Community (qMiSeq) [38] | qMiSeq (quantitative metabarcoding) consistently detected more species than capture-based surveys. | Significant positive relationships found between eDNA concentration (qMiSeq) and captured abundance/biomass. | Revealed community structure differences between upstream and downstream sites. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Core eDNA Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for eDNA studies, from sample collection to data analysis, highlighting the point at which qPCR and metabarcoding methodologies diverge.

Protocol for Species-Specific qPCR Detection