Evaluating Coalescent Models for Demographic History: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of coalescent models for inferring demographic history, tailored for researchers and professionals in biomedical and clinical research. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of coalescent theory, including its mathematical basis and key concepts like the Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA). The review then explores a spectrum of methodological approaches, from basic pairwise models to advanced structured and Bayesian frameworks, highlighting their applications in studying human evolution, disease mapping, and conservation genetics. Critical challenges such as model identifiability, computational constraints, and recombination handling are addressed, alongside practical optimization strategies. The article culminates in a comparative analysis of modern software implementations and validation techniques, synthesizing key takeaways to guide model selection and discuss future implications for understanding the demographic underpinnings of disease and tailoring therapeutic strategies.

Evaluating Coalescent Models for Demographic History: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of coalescent models for inferring demographic history, tailored for researchers and professionals in biomedical and clinical research. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of coalescent theory, including its mathematical basis and key concepts like the Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA). The review then explores a spectrum of methodological approaches, from basic pairwise models to advanced structured and Bayesian frameworks, highlighting their applications in studying human evolution, disease mapping, and conservation genetics. Critical challenges such as model identifiability, computational constraints, and recombination handling are addressed, alongside practical optimization strategies. The article culminates in a comparative analysis of modern software implementations and validation techniques, synthesizing key takeaways to guide model selection and discuss future implications for understanding the demographic underpinnings of disease and tailoring therapeutic strategies.

The Building Blocks of Coalescent Theory: From Kingman's Framework to Deep Ancestral Structure

Coalescent theory is a foundational population genetics model that describes how genetic lineages sampled from a population merge, or coalesce, as they are traced back to a single, common ancestor. This mathematical framework looks backward in time, with lineages randomly merging at each preceding generation until all converge on the Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA). The model provides the expected time to coalescence and the variance around this expectation, offering powerful insights into population history, including effective population size, migration, and divergence events [1].

The core principle involves modeling the probability that two lineages coalesce in a previous generation. In a population with a constant effective size of 2Ne, the probability of coalescence per generation is 1/(2Ne). The distribution of time until coalescence for two lineages is approximately exponential, with both mean and standard deviation equal to 2Ne generations. This simple pairwise model can be extended to samples of n individuals, where the expected time between successive coalescence events increases almost exponentially further back in time [1]. This theoretical framework underpins a wide array of computational methods developed to infer demographic history from genomic data.

Comparison of Major Coalescent-Based Methods

Researchers have developed several powerful software implementations to apply coalescent theory to genetic data. The table below summarizes the primary features of these methods.

Table 1: Key Features of Major Coalescent-Based Methods

| Method | Core Function | Optimal Sample Size | Key Input Data | Model Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC [2] [3] | Infers past population sizes from a single diploid genome | 2 haplotypes | Sequenced, phased genomes | Single, panmictic population; piecewise-constant population size |

| MSMC/MSMC2 [2] [4] [3] | Infers population size and separation history | 2-8 haplotypes (MSMC), >8 (MSMC2) | Multiple phased haplotypes | Multiple populations; cross-coalescence rates |

| BEAST/BEAST 2 [5] [6] | Bayesian inference of phylogenies & population parameters | Dozens to hundreds of samples | Molecular sequences (DNA, protein), trait data, fossil calibrations | Highly flexible; wide range of tree priors, clock models, and substitution models |

| diCal [2] | Parametric inference of complex demographic models | Tens of haplotypes | Phased haplotypes | Complex models with divergence, continuous/pulse migration, growth |

| SMC++ [2] | Infers population size history, works with unphased data | Hundreds of individuals | Genotype data (does not require phasing) | Single population; infers smooth splines for population size |

These methods differ significantly in their statistical approaches. Coalescent-hidden Markov models (Coalescent-HMMs) like PSMC, MSMC, and diCal use a sequentially Markovian coalescent framework to track genealogies along the genome, treating the genealogy at each locus as a latent variable [2]. In contrast, Bayesian MCMC frameworks like BEAST sample from the posterior distribution of trees and model parameters given the input data, allowing for the integration of multiple complex models and data sources [5] [6].

Table 2: Method Performance and Data Requirements

| Method | Statistical Power | Ability to Model Population Structure | Handling of Missing Data | Computational Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC | Limited to ancient past for a single genome | No | Not applicable to single genome | Very High |

| MSMC | Good in recent past with multiple haplotypes | Yes, via cross-coalescence rates | Not explicitly discussed | High |

| BEAST 2 | High, integrates multiple data sources | Yes, via structured tree priors [6] | Robust via data integration [6] | Moderate, depends on model complexity and data size |

| diCal | High power for recent history [2] | Yes, parametric modeling | Not explicitly discussed | Moderate |

| SMC++ | High power from large sample sizes [2] | No | Not explicitly discussed | High |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Simulation-Based Validation and Benchmarking

A standard protocol for validating and comparing coalescent methods involves coalescent simulations, where genomes are generated under a known, predefined demographic model. This allows researchers to assess a method's accuracy by comparing its inferences to the "true" history. For example, a study evaluating species tree methods under models of missing data simulated gene trees and sequence alignments under the Multi-Species Coalescent (MSC) model, which describes the evolution of individual genes within a population-level species tree [7]. The protocol involves:

- Defining a True Species Tree: A species tree (\mathcal{T}=(T,\Theta)) with topology (T) and branch lengths (\Theta) (in coalescent units) is specified.

- Generating Random Gene Trees: For each gene, a genealogy is simulated backward in time. At speciation events, lineages enter a common population and can coalesce with a hazard rate (\lambda), where coalescence times are exponentially distributed: (\tau{ij}\sim \lambda e^{-\lambda \tau{ij}}) [7].

- Generating Sequence Data (Optional): A sequence evolution model can be applied to each simulated gene tree to generate multiple sequence alignments.

- Introducing Missing Data: Taxa can be deleted from the simulated datasets under specific models (e.g., the i.i.d. model

Miid) to test method robustness [7]. - Running Inference Methods: The simulated data (either the true gene trees or the resulting sequences) are given as input to the methods being evaluated, such as ASTRAL, MP-EST, or SVDquartets [7].

- Assessing Accuracy: The estimated species tree topology is compared to the true topology (T) to measure accuracy.

Power Analysis for Structured Models

For methods designed to detect complex events like ancestral population structure, a detailed power analysis is crucial. The protocol for testing cobras, a coalescent-based model for deep ancestral structure, is illustrative [8]:

- Simulate Structured History: Genomic sequences (e.g., 3 Gb) are simulated under a pulse model of population structure. This model defines two ancestral populations (A and B) that diverge at time

T2, admix at a later timeT1with fractionγ, and have specific population sizes (NA(t)and constantNB). - Parameter Recovery Test: The method is run on the simulated data to see if it can recover the known parameters (e.g.,

γ,T1,T2). This is repeated over many replicates. - Model Comparison: The likelihood of the data under the true structured model is compared to the likelihood under an incorrect panmictic model (e.g., using PSMC) to determine if the method can correctly distinguish between them [8].

- Sensitivity Analysis: The analysis is repeated across a grid of different parameter values (e.g., different

T1andT2pairs) to identify the range of conditions under which the method performs reliably.

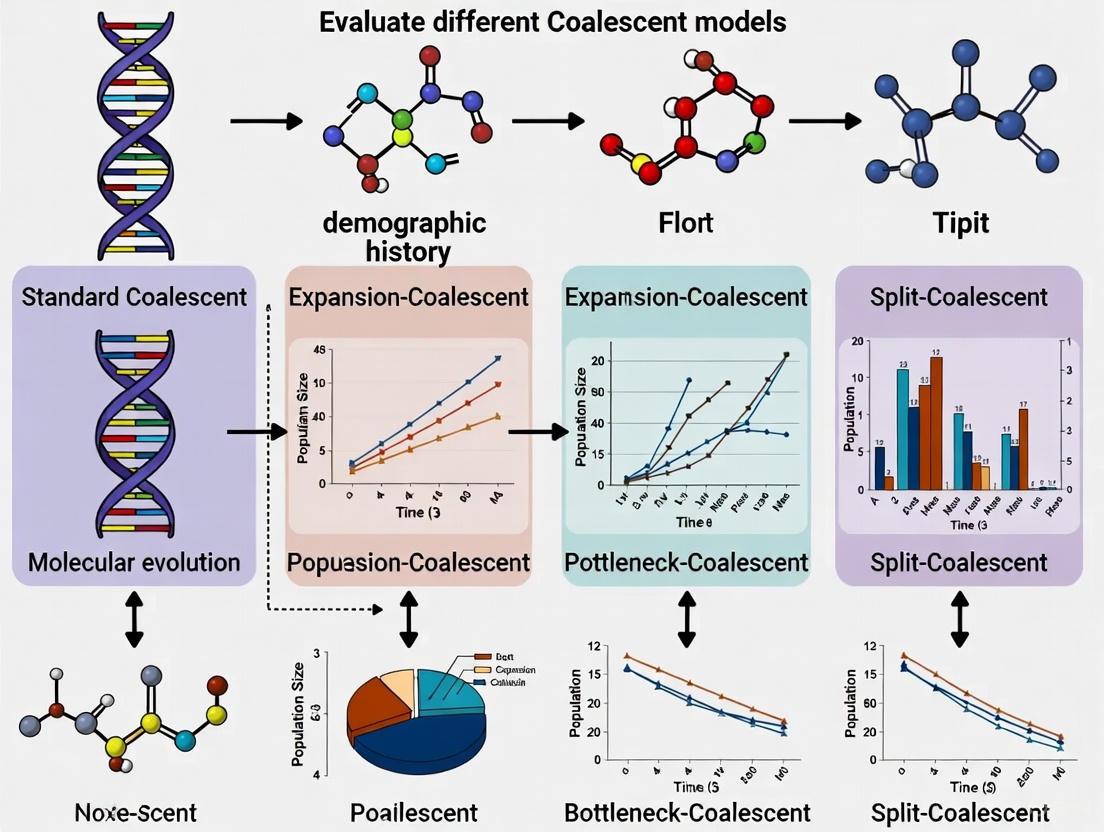

Visualization of Coalescent Models and Workflows

The Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) Framework

Methods like PSMC, MSMC, and cobras operate under the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent framework, which models how genealogies change along a chromosome due to recombination.

Successful demographic inference requires a suite of software tools and data resources. The table below lists key components of the modern population geneticist's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Coalescent Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST 2 [6] | Software Platform | Bayesian evolutionary analysis via MCMC | Integrates multiple data sources to infer rooted, time-measured phylogenies and population history. |

| PSMC [3] | Inference Tool | Infers population size history from a single genome | Provides a demographic history sketch from limited data; ideal for ancient history of a species. |

| MSMC2 [4] [3] | Inference Tool | Infers population size and separation from multiple genomes | Models complex population splits and gene flow using cross-coalescence rates. |

| Phased Haplotypes [3] | Data Pre-requisite | Genomic sequences where maternal/paternal alleles are assigned | Critical input for MSMC, diCal, and PSMC for accurate tracking of lineages. |

| High-Coverage Whole Genomes | Data | Comprehensive genomic sequencing data | Provides the raw polymorphism and linkage information needed for all coalescent-based inference. |

| Fossil Calibrations & Sampling Dates [5] [6] | Calibration Data | External temporal information | Provides absolute time scaling in BEAST analyses, converting coalescent units to years. |

| 1000 Genomes Project Data [8] | Reference Data | Public catalog of human genetic variation | A standard resource for applying and testing methods on real human population data. |

Kingman's Coalescent and the Mathematical Foundation of Genealogical Models

Coalescent theory is a foundational framework in population genetics that models how gene lineages sampled from a population trace back to a common ancestor. Developed primarily by John Kingman in the early 1980s, this mathematical approach has become the standard null model for interpreting genetic variation and inferring demographic history [1] [9]. The theory works backward in time, simulating how ancestral lineages merge or "coalesce" at common ancestors, with the waiting time between coalescence events following a probabilistic distribution that depends on population size and structure [1].

The power of coalescent theory lies in its ability to make inferences about population genetic parameters such as effective population size, migration rates, and recombination from molecular sequence data [1] [10]. By providing a model of genealogical relationships, it enables researchers to understand how genetic diversity is shaped by evolutionary forces including genetic drift, mutation, and natural selection. The theory has proven particularly valuable in phylogeography, where it helps decipher how historical events and demographic processes have influenced the spatial distribution of genetic diversity across populations and species [9].

Table: Key Properties of the Standard Kingman Coalescent

| Property | Mathematical Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Coalescence Rate | $\frac{n(n-1)}{2N_e}$ for n lineages | Probability two lineages share a common ancestor |

| Time Scaling | Measured in $2N_e$ generations | Natural time unit for genetic drift |

| Waiting Time Distribution | Exponential with mean $\frac{2N_e}{n(n-1)}$ | Stochastic time between coalescent events |

| Mutation Parameter | θ = $4N_eμ$ (diploids) | Neutral genetic diversity expectation |

Kingman's Coalescent: The Standard Model

Mathematical Foundation

Kingman's coalescent describes the ancestral relationships of a sample of genes under the assumptions of neutral evolution, random mating, constant population size, and no population structure [1]. The process is mathematically straightforward: starting with n lineages, each pair of lineages coalesces independently at rate 1 when time is measured in units of $2Ne$ generations, where $Ne$ is the effective population size [11]. This results in a series of coalescence events that gradually reduce the number of distinct ancestral lineages until reaching the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of the entire sample [1].

The waiting time $tn$ between coalescence events, representing the time during which there are exactly n distinct lineages, follows an exponential distribution with parameter $n(n-1)/2$ in coalescent time units. When converted to generations, the expected time is $E[tn] = \frac{2N_e}{n(n-1)}$ [1]. A key insight is that coalescence times increase almost exponentially as we look further back in time, with the deepest branches of the genealogy showing substantial variation [1].

Relationship to Population Models

Kingman's coalescent was originally derived as an approximation of the Wright-Fisher model of reproduction, but it has since been shown to emerge as the limiting ancestral process for a wide variety of population models provided the variance in offspring number is not too large [11] [12]. This robustness has contributed significantly to its widespread adoption across population genetics.

The coalescent effective population size $Ne$ is defined specifically in relation to Kingman's coalescent as the parameter that scales time in the coalescent process to generations [11]. For a haploid Wright-Fisher population, $Ne = N$, while for a Moran model, $N_e = N/2$, reflecting their different coalescence rates due to variations in reproductive patterns [11]. This definition differs from previous effective size measures by being tied to the complete ancestral process rather than single aspects of genetic variation.

Figure 1: Kingman coalescent with 4 lineages showing binary tree structure and exponential waiting times between coalescence events.

Alternative Coalescent Models

Tajima's Coalescent for Computational Efficiency

The Tajima coalescent, also known as the Tajima n-coalescent, represents a lower-resolution alternative to Kingman's coalescent that offers significant computational advantages [10]. While Kingman's model tracks labeled individuals and produces binary tree structures, Tajima's coalescent works with unlabeled ranked tree shapes where external branches are considered equivalent [10]. This reduction in state space is substantial - for a sample of 6 sequences, there are 360 possible Kingman topologies but only 16 Tajima topologies with positive likelihood [10].

Recent work has extended Tajima's coalescent to handle heterochronous data (samples collected at different times), which is essential for applications involving ancient DNA or rapidly evolving pathogens [10]. The likelihood profile under Tajima's coalescent is more concentrated than under Kingman's, with less extreme differences between high-probability and low-probability genealogies. This smoother likelihood surface enables more efficient Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) exploration of tree space, as proposals are less likely to be rejected in low-density regions [10].

Multiple Merger Coalescents for Extreme Reproductive Scenarios

When the Kingman coalescent assumptions are violated by extreme reproductive behavior, alternative models known as multiple merger coalescents (including Λ-coalescents and β-coalescents) provide more accurate genealogical models [13] [14]. These models allow more than two lineages to coalesce simultaneously, which occurs naturally in populations experiencing sweepstakes reproduction (where a few individuals contribute disproportionately to the next generation) or strong pervasive natural selection [13].

Multiple merger coalescents produce fundamentally different genealogies than Kingman's coalescent, with shorter internal branches and longer external branches [14]. These topological differences affect genetic diversity patterns in ways that cannot be fully captured by Kingman's coalescent, even with complex demographic histories [13]. Statistical tests based on the two-site joint frequency spectrum (2-SFS) have been developed to detect deviations from Kingman assumptions in genomic data [13].

Exact Coalescent for the Wright-Fisher Model

For situations where sample size is large relative to population size, the exact coalescent for the Wright-Fisher model provides an alternative to Kingman's approximation [12]. The Kingman coalescent differs from the exact Wright-Fisher coalescent in several important ways: shorter waiting times between successive coalescent events, different topological probabilities, and slightly smaller tree lengths for large samples [12]. The most significant difference is in the sum of lengths of external branches, which can be more than 10% larger for the exact coalescent [12].

Table: Comparison of Coalescent Models for Demographic Inference

| Model Type | Key Assumptions | Strengths | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingman Coalescent | Neutral evolution, random mating, moderate offspring variance | Robust, well-characterized, extensive software support | May be misspecified under extreme demography or selection | Standard null model, human population history |

| Tajima Coalescent | Same as Kingman but with unlabeled lineages | Computational efficiency, better MCMC mixing | Loss of label information | Large sample sizes, scalable inference |

| Multiple Merger Coalescents | Sweepstakes reproduction, strong selection | Captures extreme reproductive variance | Complex mathematics, limited software | Marine species, viruses, pervasive selection |

| Exact Wright-Fisher Coalescent | Finite population size, Wright-Fisher reproduction | Exact for WF model, no approximation needed | Computationally intensive | Small populations, large sample fractions |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Coalescent Hidden Markov Models (Coalescent-HMMs)

Coalescent hidden Markov models represent a powerful framework for inferring population history from genetic data by modeling how genealogies change along chromosomes due to recombination [15]. These methods exploit the fact that while the full ancestral process with recombination is complex, approximations that track local genealogies as hidden states in an HMM can capture the essential patterns of linkage disequilibrium [15].

The key insight behind coalescent-HMMs is that genealogies at nearby loci are correlated due to limited recombination, allowing for more powerful inference of demographic parameters than methods based solely on allele frequencies [15]. Recent advances include diCal2 for complex multi-population demography, SMC++ for scalability to larger sample sizes, and ASMC for improved computational efficiency [15]. These methods typically require careful discretization of time and may involve approximations such as tracking only a subset of the full genealogy.

Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor (TMRCA) Inference

The time to the most recent common ancestor represents a fundamental variable for inferring demographic history [14]. Recent methodological advances using inhomogeneous phase-type theory have enabled efficient calculation of TMRCA densities and moments for general time-inhomogeneous coalescent processes [14]. This approach formulates the TMRCA as the time to absorption of a continuous-time Markov chain, allowing matrix-based computation of likelihoods for independent samples of TMRCAs.

This methodology has been applied to study exponentially growing populations and to characterize genealogy shapes through parameter estimation via maximum likelihood [14]. The TMRCA provides greater explanatory power for distinguishing evolutionary scenarios than summary statistics based solely on genetic diversity, as it captures deeper historical signals [14].

Figure 2: Workflow for demographic inference using coalescent models, showing iterative model validation step.

Statistical Tests for Model Selection

Determining whether the Kingman coalescent provides an adequate description of population data requires statistical tests specifically designed to detect deviations from its assumptions. The two-site frequency spectrum (2-SFS) test offers a global approach that examines whether genome-wide diversity patterns are consistent with the Kingman coalescent under any population size history [13]. This test exploits the different dependence of the 2-SFS on genealogy topologies compared to the single-site frequency spectrum.

When applied to Drosophila melanogaster data, the 2-SFS test demonstrated that genomic diversity is inconsistent with the Kingman coalescent, suggesting the presence of multiple mergers or other violations of Kingman assumptions [13]. Such tests are crucial for avoiding misspecified models in demographic inference and for understanding which evolutionary forces have shaped patterns of genetic diversity.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Coalescent-Based Inference

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | BEAST/BEAST2, DIYABC, GENOME, IMa | Bayesian inference, simulation, parameter estimation | Flexible demographic models, temporal data integration |

| Data Formats | VCF, Newick trees, Site frequency spectra | Standardized input for analysis | Interoperability between specialized tools |

| Statistical Tests | 2-SFS test, Goodness-of-fit measures | Model selection, validation | Detection of model misspecification |

| Computational Methods | MCMC, Sequential Monte Carlo, Variational Bayes | Posterior approximation, likelihood calculation | Scalability to large datasets |

Discussion and Comparative Assessment

Kingman's coalescent remains the cornerstone of modern population genetic inference, providing a robust and well-characterized null model for demographic history [1] [11]. Its mathematical tractability and extensive software support make it the default choice for many applications, particularly for human populations where its assumptions are often reasonable [15]. However, the development of alternative coalescent models addresses important limitations that become relevant in specific biological contexts.

The Tajima coalescent offers compelling computational advantages for large sample sizes without sacrificing inferential power about population size dynamics [10]. Multiple merger coalescents provide more appropriate models for species with sweepstakes reproduction or strong selection, though they remain less accessible due to mathematical complexity and limited software implementation [13] [14]. The exact Wright-Fisher coalescent serves as an important reference for small populations or large sample fractions where Kingman's approximation may break down [12].

Methodological innovations in coalescent-HMMs and TMRCA inference continue to expand the boundaries of what can be learned from genetic data [14] [15]. The integration of these approaches with robust model selection procedures, such as the 2-SFS test, creates a powerful framework for demographic inference that can adapt to the specific characteristics of different study systems [13]. As genomic datasets grow in size and complexity, the continued development and comparison of coalescent models will remain essential for extracting accurate insights about population history from molecular sequence variation.

For decades, the assumption of panmixia—a randomly mating population without structure—has served as a foundational null model in population genetics. However, mounting evidence reveals that this simplifying assumption can produce misleading inferences about demographic history. Real populations exhibit complex structures, with subgroups experiencing varying degrees of isolation and interaction through migration and admixture events. When these realities are unaccounted for, methods assuming panmixia can generate spurious signals of population size changes, incorrectly date divergence events, and produce biased estimates of evolutionary parameters [16]. The emerging paradigm recognizes that properly modeling population structure and admixture is not merely a refinement but a necessity for accurate demographic inference. This guide evaluates coalescent-based methods for demographic history reconstruction, focusing specifically on their ability to account for population structure and admixture, with direct implications for biomedical research in personalized medicine, disease gene mapping, and understanding human evolutionary history.

Theoretical Foundation: From Panmixia to Structured Coalescent Models

The Inverse Instantaneous Coalescence Rate (IICR) and Structural Illusions

The cornerstone of many demographic inference methods is the pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent (PSMC), which estimates a history of effective population sizes by inferring the inverse coalescence rate [8]. In a perfectly panmictic population, this inverse instantaneous coalescence rate (IICR) directly corresponds to effective population size. However, in structured populations, this relationship breaks down. The IICR becomes a function of both the sampling scheme and the underlying population structure, potentially generating trajectories that suggest population size changes even when the total population size has remained constant [16]. For example, in an n-island model with constant deme sizes, the IICR for two genes sampled from the same deme shows a monotonic S-shaped decrease, while samples from different demes exhibit an L-shaped history of recent expansion [16]. This demonstrates that sampling strategy alone can produce conflicting demographic inferences from the same underlying population structure.

Identifiability Challenges in Structured Models

A fundamental challenge in demographic inference is distinguishing between true population size changes and signals generated by population structure. Theoretical work shows that for any panmictic model with changes in effective population size, there necessarily exists a structured model that can generate exactly the same pairwise coalescence rate profile without changes in population sizes [8]. This identifiability problem means that different historical scenarios can produce identical genetic signatures under different models. However, recent methodological advances leverage additional information in the transition matrix of the hidden Markov model used in PSMC to distinguish structured models from panmictic models, even when they have matching coalescence rate profiles [8].

Comparative Analysis of Coalescent Methods

Methodologies and Their Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Coalescent-Based Methods for Demographic Inference

| Method | Sample Size | Key Features | Model Flexibility | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC [2] | 2 haplotypes | Infers piecewise constant population size history; assumes panmixia | Low | Population size history from a single genome |

| MSMC [2] | >2 haplotypes | Tracks time to first coalescence; reports cross-coalescence rates | Medium | Divergence times, recent population history |

| diCal [2] | Tens of haplotypes | Parametric inference of complex models; uses conditional sampling distribution | High | Complex models with migration, admixture; recent history |

| SMC++ [2] | Hundreds of individuals | Combines SFS with SMC; infers smooth population size changes | Medium | Large sample sizes; recent and ancient history |

| CoalHMM [2] | Multiple species | Tracks coalescence in species tree branches | Medium | Species divergence, ancestral population sizes |

| cobr aa [8] | 2 haplotypes | Explicitly models ancestral population split and rejoin; infers local ancestry | High | Deep ancestral structure, archaic admixture |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Metrics on Simulated and Real Data

| Method | Inference Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Structure Detection Power | Admixture Timing Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC | High for panmictic models | High | None | Not applicable |

| MSMC | Improved in recent past | Medium | Low via CCRs | Limited |

| diCal | High for complex models | Low to medium | High with parametric models | Good for recent events |

| SMC++ | High across timescales | Medium to high | Limited | Good |

| cobr aa | High for deep structure | Medium | Specifically designed for structure | ~300 ka for human divergence |

The recently introduced cobraa (coalescence-based reconstruction of ancestral admixture) method represents a significant advance for detecting deep ancestral structure. In simulation studies, cobraa accurately recovered admixture fractions down to approximately 5% and correctly identified split and admixture times in a structured model where populations diverged 1.5 million years ago and admixed 300,000 years ago [8]. In contrast, PSMC applied to the same simulated data detected a false population size peak instead of correctly identifying the constant population size with structure [8].

Experimental Protocols for Structural Inference

cobraa Analysis Workflow for Detecting Deep Ancestral Structure

Protocol Title: Detecting Deep Ancestral Structure Using cobraa

Experimental Overview: This protocol employs the cobraa (coalescence-based reconstruction of ancestral admixture) method to identify and characterize ancient population structure and admixture events from modern genomic data [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Whole-genome sequencing data from diploid individuals

- High-performance computing infrastructure

- Reference genomes for calibration

- Genomic annotations (coding sequences, conserved regions)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Obtain phased diploid genome sequences from sources such as the 1000 Genomes Project or Human Genome Diversity Project. Ensure high coverage and quality control.

- Model Specification: Define the structured coalescent model with two ancestral populations that diverged at time T2 and admixed at time T1, with admixture fraction γ.

- Parameter Estimation: Run cobraa's expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm over multiple (T1, T2) time pairs until convergence (change in total log-likelihood <1 between iterations).

- Ancestry Inference: Use posterior decoding to identify regions of the genome derived from each ancestral population.

- Validation: Correlate inferred ancestry blocks with genomic features (e.g., distance to coding sequences) and archaic human divergence patterns.

Interpretation: The method successfully identified that all modern humans descend from two ancestral populations that diverged approximately 1.5 million years ago and admixed around 300,000 years ago in a 80:20 ratio [8]. Regions from the minority ancestral population correlate strongly with distance to coding sequence, suggesting deleterious effects against the majority background.

IICR Analysis for Discriminating Structure from Size Changes

Protocol Title: IICR Analysis to Distinguish Genuine Population Size Changes from Structural Effects

Experimental Overview: This method computes the Inverse Instantaneous Coalescence Rate for various demographic models to determine whether inferred population size changes reflect actual size variation or spurious signals from population structure [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Python script for IICR computation (Supplementary Fig. S1 from [16])

- Coalescent simulation software

- Genetic data from studied populations

- Geographic sampling information

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Define candidate demographic models including panmictic populations with size changes and structured populations with constant total size.

- IICR Calculation: Compute the theoretical IICR for each model using known distributions of coalescence times for a sample of size two.

- Simulation: Generate genetic data under each model using coalescent simulations with recombination.

- PSMC Application: Apply PSMC to simulated data to recover inferred population size history.

- Pattern Comparison: Compare empirical PSMC plots from real data to theoretical IICR trajectories from different models.

Interpretation: IICR analysis demonstrates that structured population models can produce PSMC plots identical to those from panmictic models with population size changes. This approach serves as a critical diagnostic for evaluating whether inferred demographic histories genuinely reflect population size variation or represent artifacts of unmodeled population structure [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| cobr aa Software [8] | Coalescent-based inference of ancestral structure | Detecting deep population splits and admixture |

| IICR Computation Script [16] | Theoretical calculation of inverse coalescence rates | Discriminating structure from size changes |

| Spatial Λ-Fleming-Viot Model [17] | Coalescent inference in spatial continua | Modeling continuous population distributions |

| diCal2 Framework [2] | Parametric inference of complex demography | Multi-population models with migration |

| SMC++ [2] | Scalable coalescent inference | Large sample sizes without phasing requirements |

| Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG) [18] | Complete genealogical history with recombination | Fundamental representation of sequence relationships |

| Echitovenidine | Echitovenidine, CAS:7222-35-7, MF:C26H32N2O4, MW:436.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Concanamycin C | Concanamycin C, CAS:81552-34-3, MF:C45H74O13, MW:823.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Understanding population structure and admixture has direct implications for biomedical research and drug development. Inaccurate demographic models can produce spurious signals of natural selection, leading to false positives in disease gene identification [2]. Furthermore, local ancestry patterns inferred through methods like cobraa can reveal regions of the genome under selective constraints, with direct relevance to understanding genetic disease risk across diverse populations [8]. The recognition that all modern humans carry ancestry from multiple deep ancestral populations [8] underscores the importance of considering this complex demographic history in pharmacogenomic studies and clinical trial design, as local ancestry patterns may influence drug metabolism and treatment response.

The assumption of panmixia represents a significant oversimplification that can lead to systematically biased inferences in demographic reconstruction. Methods that explicitly incorporate population structure and admixture—such as cobraa, diCal2, and structured coalescent models—provide more accurate and biologically realistic depictions of population history. The choice of inference method should be guided by the specific research question, with particular attention to the method's assumptions about structure, its power to detect admixture events, and its scalability to available data. As genomic datasets continue to grow in size and diversity, properly accounting for population structure will remain essential for valid inferences in both evolutionary and biomedical contexts.

The prevailing model of human origins, which posits a single, continuous ancestral lineage in Africa, is being fundamentally re-evaluated. For decades, the narrative of a linear progression from archaic humans to Homo sapiens has dominated paleoanthropology. However, recent breakthroughs in genomic analysis and coalescent modeling are revealing a far more complex history. A landmark 2025 study published in Nature Genetics presents compelling evidence that modern humans are the product of a deep ancestral structure, involving at least two populations that evolved separately for over a million years before reuniting [8] [19]. This revelation challenges the simplicity of the single-lineage hypothesis and suggests that the very definition of our species must account for a more intricate, braided ancestry.

The limitations of previous models, particularly their assumption of panmixia (random mating within a single population), have obscured this deeper structure. Traditional methods like the Pairwise Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (PSMC) have provided valuable insights into population size changes but operate under the potentially flawed premise of an unstructured population [8]. This article objectively compares these established methods with a novel structured coalescent model, evaluating their performance in reconstructing demographic history and their implications for biomedical research.

Model Comparison: PSMC vs. cobraa

The Established Benchmark: PSMC

The Pairwise Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (PSMC) method, introduced in 2011, revolutionized the field of demographic inference by enabling researchers to estimate historical population sizes from a single diploid genome [8]. Its fundamental principle involves analyzing the distribution of coalescence times across the genome, which reflect the times at which ancestral lineages merge. The inverse of the coalescence rate provides an estimate of the effective population size over time. PSMC's strength lies in its ability to detect broad patterns of population expansion and contraction from minimal data. However, its critical limitation is its foundational assumption of panmixia—that the ancestral population was always a single, randomly mating entity [8]. This assumption makes it incapable of detecting or accurately modeling periods of ancestral population structure, potentially leading to misinterpretations of the demographic history it reconstructs.

The Novel Challenger: cobraa

To address the limitations of PSMC, researchers from the University of Cambridge developed coalescence-based reconstruction of ancestral admixture (cobraa) [8] [19]. cobraa is a coalescent-based hidden Markov model (HMM) that explicitly models a "pulse" of population structure: two populations (A and B) descend from a common ancestor, diverge for a period, and then rejoin through an admixture event. Its parameters include the population sizes of A (which can vary over time) and B (held constant for identifiability), the admixture fraction (γ), and the split (T2) and admixture (T1) times [8]. The key innovation of cobraa is its exploitation of information in the transition probabilities of the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC). Even when a structured model and an unstructured model produce identical coalescence rate profiles, they differ in the conditional distributions of neighboring coalescence times [8]. cobraa leverages this differential information to distinguish a structured history from a panmictic one, restoring identifiability to the problem.

Table 1: Key Parameter Comparisons Between PSMC and cobraa

| Feature | PSMC (Panmictic Model) | cobraa (Structured Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | Single, randomly mating population at all times [8] | Two ancestral populations that split and later admix [8] |

| Inferred Parameters | Historical effective population size (Nâ‚‘) [8] | Nâ‚(t), Nᵦ, admixture fraction (γ), split time (T2), admixture time (T1) [8] |

| Data Input | A single diploid genome sequence [8] | A single diploid genome sequence [8] |

| Handles Ancestral Structure | No; can create false signals of bottlenecks/expansions [8] | Yes; explicitly models divergence and admixture [8] |

| Key Strength | Powerful for detecting population size changes in a simple history [8] | Identifies and characterizes deep ancestral structure invisible to PSMC [8] |

Performance and Experimental Validation

The performance of cobraa was rigorously tested on both simulated and real genomic data. On simulated data, cobraa demonstrated a strong ability to recover the true parameters of a structured history. It could accurately infer admixture fractions (γ) down to approximately 5%, with performance improving at higher mutation-to-recombination rate ratios [8]. Furthermore, cobraa successfully identified the correct neighborhood of split and admixture times through a grid-search of (T1, T2) pairs, with the maximum likelihood estimate being adjacent to the simulated truth [8].

A critical experiment involved simulating data under a structured model with a known bottleneck and then analyzing it with both PSMC and cobraa. The results were starkly different: PSMC inferred a false peak in population size, completely missing the simulated bottleneck and the underlying structure. In contrast, cobraa accurately recovered the population size changes of the major ancestral population and provided a relatively accurate estimate of the admixture fraction [8]. This experiment highlights how the assumption of panmixia can lead PSMC to profoundly misinterpret the demographic history of a species.

Table 2: Summary of Key Findings from the Application of cobraa to 1000 Genomes Data [8] [20] [19]

| Inferred Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Divergence Time (T2) | Time when the two ancestral populations initially split. | ~1.5 million years ago [8] [19] |

| Admixture Time (T1) | Time when the two populations came back together. | ~300 thousand years ago [8] [19] |

| Admixture Fraction (γ) | Proportion of ancestry from the minority population (B). | ~20% (80:20 ratio) [8] [19] |

| Post-Divergence Bottleneck | A severe population size reduction in the major lineage (A) after the split. | Detected [8] [19] |

| Relationship to Archaic Humans | The majority population (A) was also the primary ancestor of Neanderthals and Denisovans [8] [19]. | Supported |

| Functional Genomic Distribution | Minority ancestry (B) is correlated with distance from coding sequences, suggesting deleterious effects [8]. | Supported |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The cobraa Analysis Workflow

The application of the cobraa model to infer deep ancestral structure follows a detailed computational protocol. The following diagram and description outline the key steps in this process, from data preparation to biological interpretation.

Diagram 1: The cobraa Model Inference Workflow (Title: cobraa Analysis Workflow)

- Data Acquisition and Processing: The workflow begins with the acquisition of high-coverage whole-genome sequencing data from diverse modern human populations. The foundational datasets for the 2025 study came from the 1000 Genomes Project and the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) [8] [19]. Raw sequence data undergoes standard processing pipelines, including alignment to a reference genome and variant calling, to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and other genetic variants.

- Model Definition and Initialization: Researchers define the parameters of the structured coalescent model, including initial guesses for the split time (T2), admixture time (T1), and admixture fraction (γ). The population size of the minority ancestral group (Nᵦ) is typically held constant, while the size of the majority group (Nâ‚(t)) is allowed to vary over time [8].

- Iterative Model Fitting with Grid Search: The core of the analysis involves running the cobraa Hidden Markov Model (HMM). cobraa uses an Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm to iteratively estimate population sizes and the admixture fraction until convergence is achieved (i.e., the change in total log-likelihood between iterations falls below a threshold) [8]. Because the split and admixture times (T1, T2) are fixed in a single run, this process is embedded within a grid search. cobraa is run repeatedly over different (T1, T2) pairs, and the log-likelihood of each model is recorded. The pair with the maximum log-likelihood is selected as the best-fitting model [8].

- Ancestry Decomposition and Functional Analysis: Using the fitted model, posterior decoding is performed to infer which regions of the modern human genome are derived from each of the two ancestral populations [8] [19]. These ancestry assignments are then correlated with functional genomic annotations (e.g., proximity to genes) and compared with divergent sequences from archaic humans like Neanderthals and Denisovans to draw evolutionary and functional conclusions [8].

Validation with Simulated Data

A critical step in establishing the validity of cobraa involved rigorous testing on simulated data where the true demographic history was known. The protocol for this validation is as follows:

- Simulation Setup: Genomic sequences are simulated under a specified structured demographic model, incorporating parameters such as population sizes, divergence and admixture times, admixture proportion, mutation rate (e.g., μ = 1.25 × 10â»â¸), and recombination rate (e.g., r = 1 × 10â»â¸) [8].

- Benchmarking: The simulated data is analyzed with both cobraa and PSMC. The inferences from each method (e.g., estimated population sizes, admixture fraction) are then compared against the known, simulated "ground truth" [8].

- Power Assessment: This process is repeated across a wide range of parameter values (e.g., different admixture fractions γ from 0.05 to 0.4) and with multiple replicates to assess the statistical power, accuracy, and potential biases of the cobraa method [8].

Successfully conducting demographic inference research requires a suite of computational tools and data resources. The table below details the key "research reagents" used in the featured study and essential for work in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Coalescent Modeling

| Resource/Solution | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| cobraa Software | Computational Algorithm | Implements the structured coalescent HMM to infer population split, admixture, and size history from genomic data [8]. |

| PSMC Software | Computational Algorithm | Infers historical effective population size from a single genome under a panmictic model; used as a benchmark for comparison [8]. |

| 1000 Genomes Project Data | Genomic Dataset | A public catalog of human genetic variation from diverse populations; serves as the primary source of modern human sequences for analysis [8] [19]. |

| Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) Data | Genomic Dataset | A resource of human cell lines and DNA from globally diverse populations; used to validate findings across human genetic diversity [8]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | Provides the substantial computational power required for running multiple HMM iterations and grid searches over parameter space. |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | Bioinformatics Pipeline | A standard suite of tools for variant discovery in high-throughput sequencing data; used for initial data processing and quality control. |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

The revelation of a deep ancestral structure in all modern humans has profound implications beyond evolutionary genetics, particularly for biomedical research and drug development. The non-random distribution of ancestral segments in the genome is a critical finding. The study discovered that genetic material from the minority ancestral population is strongly correlated with distance to coding sequences, suggesting it was often deleterious and purged by natural selection from gene-rich regions [8] [19]. This creates a genomic architecture where an individual's ancestry proportion at a specific locus can influence disease risk.

For drug development, this underscores the necessity of accounting for local ancestry in Pharmacogenomics. Genetic variants influencing drug metabolism (pharmacokinetics) and drug targets (pharmacodynamics) may have differential effects depending on their deep ancestral background. A one-size-fits-all approach to drug dosing may be ineffective or even harmful if these underlying structural variations are not considered. Furthermore, the discovery that genes related to brain function and neural processing from the minority population may have been positively selected [19] opens new avenues for neuroscience research, potentially identifying novel pathways and targets for neuropsychiatric disorders. Understanding this deep structure is therefore not just about our past, but is essential for developing the precise and equitable medicines of the future.

A Spectrum of Coalescent Models: From PSMC to Structured Admixture and Bayesian Inference

Article Contents

- PSMC Overview & Mechanism: Core principles and workflow of the PSMC method.

- Limitations of PSMC: Key constraints of the original model.

- The Evolving Landscape of PSMC Alternatives: Advanced methods addressing PSMC limitations.

- Comparative Performance Analysis: Accuracy, scalability, and benchmark data.

- Experimental Protocols: Common methodologies for evaluation.

- Research Toolkit: Essential software and resources.

The Pairwise Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (PSMC) is a computational method that infers a population's demographic history from the genome sequence of a single diploid individual [21]. By analyzing the mosaic of ancestral segments within the genome, PSMC can estimate historical effective population sizes over a time span of thousands of generations [21]. Its ability to work with unphased genotypes makes it particularly valuable for non-model organisms where high-quality reference genomes and phased data may be unavailable [22].

The model works by relating the local variation in the time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) along the genome to fluctuations in historical population size. It uses a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to trace the coalescent history of the two chromosomes, where the hidden states are the coalescent times. Because these times are continuous, the model discretizes them into a finite number of intervals, assuming the population size is constant within each interval [23]. This process produces an inference of historical effective population size, revealing periods of population expansion, decline, or stability.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of the PSMC inference process.

Limitations of the Original PSMC Model

Despite its revolutionary impact, the original PSMC model has several recognized limitations that affect its resolution and applicability.

- Simplistic Historical Reconstruction: A fundamental constraint is the assumption that the effective population size remains constant within each discretized time interval [23]. This leads to a "stair-step" appearance in the inferred history, which is a simplification of what were likely more continuous or complex changes [22].

- Limited Recent History Resolution: PSMC provides poor estimates of very recent population history (e.g., within the last 10-20 thousand years) due to a limited number of informative recombination and coalescence events in that time range from a single genome [23].

- Restriction to a Single Sample: As originally formulated, PSMC can only analyze data from a single diploid sample. It cannot leverage information from multiple individuals in a population, which limits its statistical power and prevents the inference of more complex demographic scenarios involving population structure [22].

- Sensitivity to Data Quality and Quantity: The method's performance depends on genome coverage. While designed for whole-genome data, simulations show it can be applied to Restriction Site Associated DNA (RAD) data, but its reliability decreases significantly when the proportion of the genome covered falls to 1% [21].

The Evolving Landscape of PSMC Alternatives

To address the limitations of PSMC, several successor methods have been developed, incorporating more complex models and leveraging increased computational power.

Key Methodological Advances

- Beta-PSMC: This extension replaces the assumption of a constant population size within each time interval with the probability density function of a beta distribution [23]. This allows Beta-PSMC to model a wider variety of population size changes within each interval (such as gradual growth or decline), uncovering more detailed historical fluctuations, particularly in the recent past, without a prohibitive increase in the number of discretized intervals [23].

- PHLASH: A recent Bayesian method that aims to be a general-purpose inference procedure [22]. It is designed to be fast, accurate, capable of analyzing thousands of samples, and invariant to phasing. A key innovation is a new technique for efficiently computing the gradient of the PSMC likelihood function, which enables rapid navigation to areas of high posterior probability. PHLASH provides a full posterior distribution over the inferred history, offering built-in uncertainty quantification [22].

- SMC++: This method incorporates the joint modeling of the SFS and the pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent, allowing it to analyze larger sample sizes than PSMC while also integrating information from the allele frequency spectrum [22].

- MSMC2: A generalization of the PSMC concept that optimizes a composite likelihood evaluated over all pairs of haplotypes in a multi-sample dataset, improving the inference of recent population history [22].

Comparative Strengths of Advanced Methods

Table 1: Comparison of PSMC and its successor methods.

| Method | Key Innovation | Sample Size Flexibility | Key Advantage | Notable Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC [21] | Baseline model | Single diploid individual | Robust with unphased data; simple interpretation | "Stair-step" history; poor recent inference |

| Beta-PSMC [23] | Beta distribution for population size fluctuation in intervals | Single diploid individual | More detailed history within intervals; better recent past resolution | Struggles with instant population changes |

| PHLASH [22] | Bayesian inference with efficient likelihood differentiation | Scalable to thousands of samples | Full posterior uncertainty; high accuracy; fast (GPU-accelerated) | Requires more data for good performance with very small samples |

| SMC++ [22] | Incorporates site frequency spectrum (SFS) | Multiple samples | Leverages SFS for improved inference | Cannot analyze very large sample sizes within feasible time |

| MSMC2 [22] | Composite likelihood from all haplotype pairs | Multiple samples | Improved resolution from multiple samples | High memory usage with larger samples |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Recent benchmarks on simulated data, where the true demographic history is known, provide a quantitative basis for comparing these methods.

Benchmarking Results

A 2025 study evaluated PHLASH, SMC++, MSMC2, and FITCOAL (an SFS-based method) across 12 different established demographic models from the stdpopsim catalog, representing eight different species [22]. The tests used whole-genome sequence data simulated for diploid sample sizes (n) of 1, 10, and 100. Accuracy was measured using the root mean-square error (RMSE) of the estimated population size on a log–log scale.

Table 2: Summary of benchmark results comparing the performance of demographic inference methods. Data sourced from [22].

| Scenario | Most Accurate Method | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=1, 10, 100) | PHLASH (61% of scenarios) | Tended to be the most accurate most often across diverse models and sample sizes. |

| n = 1 (Single diploid) | PHLASH, SMC++, MSMC2 | Performance differences were small; SMC++ and MSMC2 sometimes outperformed PHLASH. |

| n = 10, 100 | PHLASH | PHLASH's performance scaled effectively with larger sample sizes. |

| Constant Size Model | FITCOAL | Extremely accurate when the true model fits its assumptions. |

The study concluded that while no single method uniformly dominates all others, PHLASH was the most accurate most often and is highly competitive across a broad spectrum of models [22]. Its non-parametric nature allows it to adapt to variability in the underlying size history without user fine-tuning.

Computational Performance

Computational requirements are a practical consideration for researchers.

- Beta-PSMC: The running time for Beta-PSMC is close to that of a standard PSMC run with a number of intervals equal to

n * k, wherenis the number of intervals andkis the number of subintervals used for beta distribution fitting [23]. A smallerk(e.g., 3) is often sufficient for accurate inference in most scenarios [23]. - PHLASH: This method leverages a highly efficient, GPU-based implementation. In benchmarks, it tended to be faster and have lower error than several competing methods, including SMC++, MSMC2, and FITCOAL, while also providing Bayesian uncertainty quantification [22].

Experimental Protocols

The following is a generalized protocol for evaluating demographic inference methods, based on methodologies common in the field and referenced in the search results [23] [22] [21].

Data Simulation and Method Testing

A standard approach for quantitative comparison involves simulation-based benchmarking.

- Define a True Demographic Model: Establish a known population size history, which may include complex features like exponential growth, bottlenecks, and migration. Public catalogs like stdpopsim provide standardized models [22].

- Simulate Genomic Data: Use a coalescent simulator (e.g., SCRM [22]) to generate synthetic genome sequences under the defined model. Parameters like mutation rate and recombination rate must be specified.

- Run Inference Methods: Apply PSMC and alternative methods (e.g., Beta-PSMC, PHLASH, SMC++) to the simulated data.

- Compare to Ground Truth: Quantify accuracy by comparing the inferred population trajectory to the known, simulated history using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) on a log–log scale [22].

Application to Real Genomic Data

When applying these methods to empirical data, the workflow is as follows.

- Data Preparation: Obtain a high-coverage genome sequence for the target species (for single-genome methods) or a dataset of multiple individuals. For PSMC, the input is typically a consensus sequence in FASTQ format.

- Parameter Setting: Define key parameters, including generation time, per-generation mutation rate, and the number of discretized time intervals. These are often derived from literature.

- Execution and Model Selection: Run the inference tool. For methods like Beta-PSMC, the number of subintervals (

k) must be chosen [23]. - Interpretation and Validation: Analyze the resulting plot of effective population size over time. The results can be validated by comparing with known climatic events or independent archaeological/paleontological evidence [23].

The workflow for a typical benchmarking study, from simulation to analysis, is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key resources and software solutions essential for conducting demographic inference using PSMC and its alternatives.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and software for coalescent-based demographic inference.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC [21] | Software | Infers population history from a single genome. | The baseline method; useful for initial assessment and for species with limited samples. |

| Beta-PSMC [23] | Software | Infers detailed population fluctuations within time intervals. | Used for obtaining higher-resolution insights from a single genome, especially for recent history. |

| PHLASH [22] | Software (Python) | Bayesian inference of population history from many samples. | Recommended for scalable, accurate, full-population analysis with uncertainty quantification. |

| SMC++ [22] | Software | Infers demography using SFS and PSMC framework. | Suitable for analyses that aim to combine linkage and allele frequency information. |

| stdpopsim [22] | Catalog | Standardized library of population genetic simulation models. | Provides rigorously defined models for consistent and comparable method benchmarking. |

| SCRM [22] | Software | Coalescent simulator for genomic sequences. | Generates synthetic data under a known demographic model for method testing and validation. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Data | Data | High-coverage genome sequence from a diploid individual. | The primary input for single-genome methods like PSMC and Beta-PSMC. |

| Cyclic HPMPC | Cyclic-hpmpc|CAS 127757-45-3|For Research | Cyclic-hpmpc is a broad-spectrum antiviral research compound. This product is For Research Use Only, not for human or veterinary therapeutic applications. | Bench Chemicals |

| Based | Based, CAS:199804-21-2, MF:C18H18N8O4S2, MW:474.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

In the field of population genetics, accurately reconstructing demographic history from genomic data is a fundamental challenge. The Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (SMC) and its successor, SMC', are two pivotal models that have enabled researchers to infer past population sizes and divergence times using a limited number of genome sequences. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two core models, evaluating their theoretical foundations, performance, and practical applications to help researchers select the appropriate tool for demographic inference.

Model Fundamentals: From SMC to SMC'

The Sequentially Markovian Coalescent is a class of models that approximate the complex ancestral recombination graph (ARG) by applying a Markovian simplification to the coalescent process along the genome [24]. This innovation made it computationally feasible to analyze genome-scale data for demographic inference.

The Original SMC Model: Introduced by McVean and Cardin (2005), the SMC model simplifies the ARG by dictating that each recombination event necessarily creates a new genealogy. In its backward-in-time formulation, the key rule is that coalescence is permitted only between lineages containing overlapping ancestral material [24]. This makes the process sequentially Markovian, meaning the genealogy at any point along the chromosome depends only on the genealogy at the previous point.

The SMC' Model: Introduced by Marjoram and Wall (2006) as a modification to the SMC, the SMC' model is a closer approximation to the full ARG. Its defining rule is that lineages can coalesce if they contain overlapping or adjacent ancestral material [24]. This slight change in the coalescence rule has significant implications, as it allows the two lineages created by a recombination event to coalesce back with each other. Consequently, in the SMC' model, not every recombination event results in a new pairwise coalescence time.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between SMC and SMC'

| Feature | SMC Model | SMC' Model |

|---|---|---|

| Key Reference | McVean and Cardin (2005) [24] | Marjoram and Wall (2006) [24] |

| Coalescence Rule | Only between lineages with overlapping ancestral material [24] | Between lineages with overlapping or adjacent ancestral material [24] |

| Effect of Recombination | Every recombination event produces a new coalescence time [24] | Not every recombination event produces a new coalescence time [24] |

| Theoretical Approximation to ARG | First-order approximation [24] | "Most appropriate first-order" approximation; more accurate [24] |

Performance and Quantitative Comparison

The transition from SMC to SMC' was driven by the need for greater accuracy in approximating real genetic processes. Quantitative analyses and practical applications have consistently demonstrated the superior performance of the SMC' model.

Analytical and Simulation-Based Evidence

A key analytical result is that the joint distribution of pairwise coalescence times at recombination sites under the SMC' is the same as it is marginally under the full ARG. This demonstrates that SMC' is, in an intuitive sense, the most appropriate first-order sequentially Markov approximation to the ARG [24].

Furthermore, research has shown that population size estimates under the pairwise SMC are asymptotically biased, while under the pairwise SMC' they are approximately asymptotically unbiased [24]. This is a critical advantage for SMC' in demographic inference, as it means that with sufficient data, its estimates will converge to the true population size.

Simulation studies have confirmed that SMC' produces measurements of linkage disequilibrium (LD) that are more similar to those generated by the ARG than the original SMC does [24]. Since LD is a fundamental pattern shaped by population genetic forces, accurately capturing it is essential for reliable inference.

Performance in Practical Applications

The SMC and SMC' frameworks underpin several widely used software tools for demographic inference. Their performance can be evaluated by examining the capabilities of these tools.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SMC/SMC'-Based Inference Tools

| Software Tool | Underlying Model | Key Application & Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSMC(Pairwise SMC) | SMC [25] | Infers population size history from a single diploid genome. Powerful for deep history and ancient samples [25]. | Less powerful in the recent past; only uses two haplotypes [2]. |

| MSMC(Multiple SMC) | SMC' [24] | Uses multiple haplotypes. Improved power in the recent past and for inferring cross-coalescence rates between populations [2]. | Does not perform parametric model fitting for complex multi-population scenarios [2]. |

| diCal2 | SMC' (CSD framework) [2] | Performs parametric inference of complex models (divergence, migration, growth). Powerful for recent history (e.g., peopling of the Americas) [2]. | Computational cost increases with more populations [2]. |

| SMC++ | SMC [2] | Scales to hundreds of unphased samples, providing power in both recent and ancient past. Infers population sizes as smooth splines [2]. | Simpler hidden state compared to multi-haplotype methods [2]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing SMC-based inference requires a structured workflow, from data preparation to model interpretation. The following protocol outlines the key steps, with a focus on methods like PSMC and MSMC that have been widely applied.

Data Preparation and Input Generation

- Sequence Data Processing: Begin with whole-genome sequencing data (e.g., BAM files). Call variants and generate a consensus sequence in FASTA format for the target individual(s). For a diploid PSMC analysis, this involves creating a single sequence where each homozygous site is represented by its base and each heterozygous site by an IUPAC ambiguity code [25].

- Input File Generation: The consensus sequence is converted into the required input format for the specific tool. For PSMC, this is often a

psmcfafile, which is a binary representation of the genome sequence. This step effectively transforms the genomic variation data into a form that the HMM can interpret.

Model Execution and Parameter Setting

- Running the Analysis: Execute the software (e.g.,

psmcormsmc) with the input file and chosen parameters. - Parameter Selection: This is a critical step that influences the accuracy and resolution of the inference.

- Mutation Rate (μ) and Generation Time (g): These are not inferred by the model but are used to scale the results from coalescent units to real years and effective population sizes. The values must be chosen based on prior knowledge from the study species [25]. Incorrect assumptions here will systematically bias all estimates.

- Time Interval Patterning (

-pin PSMC): This parameter specifies the atomic time intervals for the HMM. It controls the resolution and time depth of the inference. A common pattern is-p "4+25*2+4+6", which sets 64 free interval parameters [25]. The pattern should be chosen based on the available data and the time periods of interest.

- Bootstrapping: To assess the confidence of the inferred demographic history, perform bootstrap analyses by randomly resampling genomic segments with replacement and re-running the inference. This generates a confidence interval around the population size history curve.

Output Interpretation

- The SMC-HMM Process: The tool uses an HMM where the hidden states are discrete time intervals representing the coalescence time (T) for the two alleles at a genomic position [25]. The observations are the sequenced genotypes (homozygous or heterozygous). The emission probability describes the chance of a mutation given T, and the transition matrix describes how coalescence times change along the chromosome due to recombination under the SMC/SMC' model [8] [25].

- Plotting the Results: The primary output is a file that can be plotted to show the trajectory of effective population size (Ne) over time. The Y-axis is Ne (derived from the inverse coalescence rate) and the X-axis is time in the past (often on a log scale). The bootstrap results can be plotted as confidence intervals around the main trajectory.

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

The SMC framework continues to be a fertile ground for methodological innovation, enabling researchers to ask increasingly complex questions about population history.

A significant recent advancement is the development of cobrra, a coalescent-based HMM introduced in 2025 that explicitly models an ancestral population split and rejoin (a "pulse" model of structure) [8]. This method addresses a key limitation of earlier tools like PSMC, which assume a single, panmictic population throughout history. Theoretical work had shown that a structured population model could produce a coalescence rate profile identical to that of an unstructured model with population size changes, creating an identifiability problem [8].

cobrra leverages additional information in the SMC model transitions—the conditional distributions of neighboring coalescence times—to distinguish between structured and panmictic histories [8]. When applied to data from the 1000 Genomes Project, cobrra provided evidence for deep ancestral structure in all modern humans, suggesting an admixture event ~300 thousand years ago between two populations that had diverged ~1.5 million years ago [8]. This showcases how extensions of the SMC framework can yield novel biological insights into deep history.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful demographic inference requires both robust software and accurate ancillary data. The following table lists essential "research reagents" for conducting SMC-based analyses.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for SMC-Based Demographic Inference

| Category | Item/Software | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Core Software | PSMCMSMCdiCalSMC++ | Infers population size history from a single diploid genome [25].Infers population size and cross-coalescence rates from multiple haplotypes [2].Parametric inference of complex multi-population models with migration [2].Infers history from hundreds of unphased samples [2]. |

| Ancillary Data | Mutation Rate (μ)Generation Time (g)Reference Genome | Scales coalescent time to real mutations per base per generation; critical for timing events [25].Converts generational timescale to real years [25].Essential for aligning sequence data and calling variants. |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary processing power and memory for whole-genome analysis and bootstrapping. |

| Arborinine | Arborinine, CAS:5489-57-6, MF:C16H15NO4, MW:285.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Sequentially Markovian Coalescent has revolutionized the study of demographic history from genomic data. While the original SMC model provided a breakthrough in computational tractability, the SMC' model has proven to be a superior approximation to the ancestral recombination graph, yielding less biased estimates and more accurate representations of linkage disequilibrium.

The choice between the two models in practice is often dictated by the software implementation. For analyses of a single diploid genome focusing on deep history, the SMC-based PSMC remains a robust and widely used tool. For studies requiring higher resolution in the recent past, leveraging multiple genomes, or investigating population splits, SMC'-based tools like MSMC and diCal2 are more powerful. Emerging methods like cobrra demonstrate that the SMC framework is still evolving, now enabling researchers to probe deep ancestral structure and admixture that were previously inaccessible. As genomic data sets continue to grow in size and complexity, the SMC and SMC' models will undoubtedly remain foundational for unlocking the secrets of population history.

Mapping Disease Genes, Conservation, and Human Evolutionary History

The coalescent theory provides a powerful mathematical framework for reconstructing the demographic history of populations from genetic data. By modeling the genealogy of sampled sequences backward in time, coalescent-based methods can infer historical population sizes, divergence times, migration patterns, and other demographic parameters that have shaped genetic diversity. These inferences play a crucial role in mapping disease genes by providing realistic null models for distinguishing neutral evolution from natural selection, in conservation genetics by identifying endangered populations and understanding their historical trajectories, and in unraveling human evolutionary history by reconstructing migration routes and population admixture events.

Recent methodological advances have expanded the applicability and accuracy of coalescent-based inference. Key developments include improved computational efficiency enabling analysis of larger sample sizes, more flexible modeling choices accommodating complex demographic scenarios, and enhanced utilization of linkage disequilibrium information through coalescent hidden Markov models (coalescent-HMMs) [15]. These improvements have addressed earlier limitations related to scalability and model flexibility, allowing researchers to tackle increasingly sophisticated biological questions across various organisms, from humans to pathogens to endangered species.

Comparative Performance of Contemporary Coalescent Methods

Quantitative Benchmarking of Inference Accuracy

Recent methodological advances have produced several competing approaches for demographic inference. A comprehensive benchmark study evaluated PHLASH against three established methods—SMC++, MSMC2, and FITCOAL—across 12 different demographic models from the stdpopsim catalog representing eight species (Anopheles gambiae, Arabidopsis thaliana, Bos taurus, Drosophila melanogaster, Homo sapiens, Pan troglodytes, Papio anubis, and Pongo abelii) [22]. The tests simulated whole-genome data for diploid sample sizes of n ∈ {1, 10, 100} with three independent replicates, resulting in 108 simulation runs.

Table 1: Method Performance Across Sample Sizes Based on Root Mean Square Error

| Method | n=1 | n=10 | n=100 | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHLASH | Competitive with SMC++/MSMC2 | Most accurate in majority of scenarios | Most accurate in majority of scenarios | Highest accuracy in 22/36 scenarios (61%) |

| SMC++ | Most accurate for some models | Limited to n∈{1,10} due to computational constraints | Could not run within 24h | Highest accuracy in 5/36 scenarios |

| MSMC2 | Most accurate for some models | Limited to n∈{1,10} due to memory constraints | Could not run within 256GB RAM | Highest accuracy in 5/36 scenarios |

| FITCOAL | Crashed with n=1 | Accurate for constant growth models | Extremely accurate for members of its model class | Highest accuracy in 4/36 scenarios |

The benchmark employed root mean square error (RMSE) as the primary accuracy metric, calculated as the squared area between true and estimated population curves on a log-log scale, giving greater emphasis to accuracy in the recent past and for smaller population sizes [22]. Results demonstrated that no method uniformly dominated all others, but PHLASH achieved the highest accuracy most frequently across the tested scenarios.

Method-Specific Strengths and Computational Considerations