Evolutionary Algorithms in Protein Design: From AI-Driven Exploration to Clinical Applications

This article explores the transformative role of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) in protein design, a field being reshaped by artificial intelligence.

Evolutionary Algorithms in Protein Design: From AI-Driven Exploration to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) in protein design, a field being reshaped by artificial intelligence. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational principles and the limitations of traditional methods like directed evolution. The piece details modern methodological synergies, such as EA-AI integration and automated biofoundries, for designing novel proteins and biosensors. It also addresses key optimization challenges, including force field accuracy and epistasis, and provides a comparative analysis of EA performance against other computational techniques. Finally, the article examines experimental validation frameworks and discusses the future clinical and biotechnological implications of these rapidly advancing technologies.

The Evolutionary Algorithm Paradigm: Reinventing Protein Design from First Principles

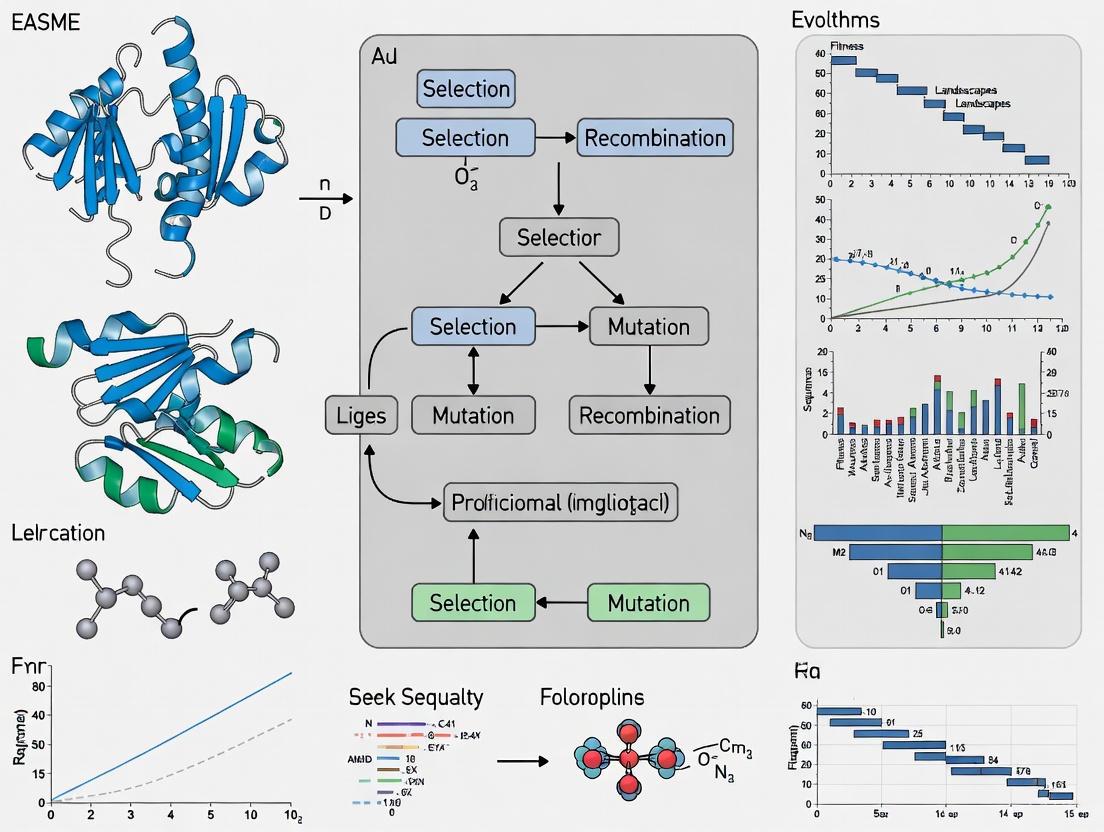

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are population-based, stochastic optimization techniques that simulate Darwinian evolution, maintaining a population of potential solutions that undergo selection, variation, and inheritance over successive generations [1] [2]. Within biological research, particularly in the emerging field of Evolutionary Algorithms Simulating Molecular Evolution (EASME), these algorithms are being specialized to address the profound complexity of molecular sequence spaces [3] [4]. The EASME framework represents a paradigm shift by employing EAs with DNA string representations, biologically-accurate molecular evolution models, and bioinformatics-informed fitness functions to explore the vast search space of possible functional proteins [3].

Proteins, the essential engines of metabolism, can be conceptualized as sentences written with an alphabet of 20 amino acids. The search space for even a modestly-sized protein is astronomically large, and the set of functional proteins discovered by nature represents only a minute fraction of this theoretical space—a limited "vocabulary" in a vast "sea of invalidity" [3] [4]. EASME aims to expand this vocabulary by computationally colonizing the functional "islands" in this sea, potentially discovering useful proteins that went extinct long ago or have never existed in nature [4]. This approach leverages the unique strength of EAs to uncover novel solutions through an explainable, rule-based process, complementing the pattern recognition capabilities of machine learning [3].

Core Algorithmic Framework and Quantitative Parameters

Algorithmic Variants and Their Biological Applications

The family of evolutionary algorithms encompasses several distinct methodologies, each with particular strengths for biological problem-solving. The table below summarizes the key EA types and their relevant applications to molecular design.

Table 1: Evolutionary Algorithm Types and Biological Applications

| Algorithm Type | Key Characteristics | Molecular Biology Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [2] | Operates on fixed-length binary or integer strings; uses selection, crossover, and mutation operators. | Global optimization of molecular properties; exploratory search in large sequence spaces. |

| Genetic Programming (GP) [2] | Evolves computer programs (or protein sequences) represented as trees; uses specialized tree-based operators. | De novo protein design; evolution of protein interaction rules and functional motifs. |

| Differential Evolution (DE) [2] | Creates new candidates by combining parent and population individuals; efficient for continuous spaces. | Optimization of continuous parameters in fitness landscapes; fine-tuning molecular properties. |

| Evolution Strategies (ES) [2] | Operates on floating-point vectors; emphasizes mutation with adaptive step-size control. | Real-value parameter optimization in molecular dynamics; precise exploration of local fitness optima. |

Critical Parameters for Experimental Design

The performance and behavior of an EA are governed by a set of core parameters. Research indicates that the parameter space for EAs is often "rife with viable parameters," but careful selection remains crucial for efficient exploration and exploitation [5]. The following table outlines fundamental parameters and their impact on evolutionary search.

Table 2: Key Evolutionary Algorithm Parameters and Tuning Guidance

| Parameter | Biological Analogy | Impact on Search Dynamics | Typical Range/Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size [1] [5] | Genetic diversity of a species. | Larger sizes enhance exploration but increase computational cost. | Problem-dependent; often 50-1000 individuals. |

| Generation Count [5] | Number of evolutionary generations. | Determines convergence and search duration. | Often hundreds to thousands. |

| Selection Mechanism & Size [1] [5] | Natural selection pressure. | Stronger selection (e.g., larger tournament sizes) accelerates convergence but risks premature convergence. | Tournament, roulette wheel, rank-based. |

| Crossover Rate [2] [5] | Sexual recombination. | Enables exchange of beneficial traits between individuals. | 0.6 - 0.9 (60% - 90%) common in GAs. |

| Mutation Rate [2] [5] | Point mutation rate in DNA. | Introduces novel variations; prevents premature convergence. | Highly sensitive; often low (e.g., 0.001 - 0.05 per gene). |

Application Notes: Exploring Protein Sequence-Function Landscapes

Reconstructing Fitness Landscapes from Homologous Sequences

A powerful application of EAs in computational biology involves building data-driven fitness landscapes from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of homologous proteins [6]. These landscapes serve as proxies for protein fitness, enabling quantitative predictions and simulations.

Fitness Landscape Model: The landscape is formally represented using a Potts model, where the probability of a sequence ((a1, ..., aL)) is given by:

[

P(a1, ..., aL) = \frac{1}{Z} \exp\left(-E(a1, ..., aL)\right)

]

The energy function (E(a1, ..., aL) = -\sumi hi(ai) - \sum{i

Experimental Simulation Protocol:

- Input: A wild-type protein sequence and an MSA of its natural homologs from a database like Pfam.

- Landscape Inference: Use Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) or similar methods to infer the parameters ((hi), (J{ij})) of the Potts model from the MSA.

- In-Silico Evolution: a. Initialization: Start a population with the wild-type sequence. b. Mutation: Introduce single-nucleotide mutations at the DNA level, which are translated to the amino acid sequence. c. Selection: Evaluate mutant fitness using the inferred landscape ((P(a1, ..., aL))) and select fitter variants with a probability proportional to their fitness.

- Analysis: The resulting simulated sequence library can be analyzed for fitness distributions, mutational spectra, and the emergence of epistatic signals sufficient for protein contact prediction [6].

Protocol for EASME-Driven Protein Discovery

The EASME framework provides a structured methodology for both reconstructing potential extinct proteins and designing novel ones [3] [4]. The workflow for this process is delineated below.

Detailed Protocol:

Objective Definition:

- Path A (Unknown to Known): Aim to reconstruct extinct evolutionary intermediates by applying selection pressure that pushes evolution toward a known protein family consensus sequence [4].

- Path B (Known to Unknown): Aim to design novel proteins by applying forward evolutionary pressure toward a desired functional characteristic or phenotype not found in nature [4].

EA Configuration:

- Representation: Encode proteins as DNA or amino acid strings within the EA chromosome [3] [7].

- Operators: Implement biologically-realistic mutation (e.g., point mutations) and crossover (recombination) operators.

- Fitness Function: This is the core of the experiment. For protein optimization, the function must integrate bioinformatic analyses that evaluate the functional potential of the encoded protein. This can include:

- De novo protein folding predictions to assess structural stability.

- Statistical energy scores from inferred fitness landscapes (e.g., Potts model energy) [6].

- Docking scores for binding affinity in therapeutic protein design.

- Compatibility with desired functional motifs.

Evolutionary Run:

- Execute the EA with a sufficiently large population and generation count to allow for substantial exploration of the sequence space.

- The output is a set of Pareto optimal sequences representing the best trade-offs between different objectives (e.g., stability vs. novelty) [4].

Validation:

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EASME

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) [6] | Provides evolutionary constraints from homologous proteins; basis for inferring data-driven fitness landscapes. | Essential for building Potts models to guide in-silico evolution and evaluate fitness. |

| Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) [6] | A global statistical model to extract epistatic couplings ((J_{ij})) from an MSA. | Used within the fitness function to score sequences based on evolutionary likelihood and for contact prediction. |

| SMILES Representation [8] | A line notation for encoding the structure of chemical molecules as strings. | Used by algorithms like MolFinder for the global optimization of small molecule properties in drug discovery. |

| Meta-Genetic Algorithm [5] | An EA used to optimize the hyperparameters (e.g., mutation rate) of another EA. | For systematically tuning the parameters of a molecular optimization EA to a specific problem. |

| Wet-Lab Synthesis & Screening [3] | Biological synthesis (e.g., gene synthesis, protein expression) and functional assays (e.g., bioassay). | Final validation of computationally designed proteins; critical for closing the design-test-learn loop. |

Navigating the Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma

A central challenge in applying EAs to vast molecular search spaces is balancing exploration (searching new regions) and exploitation (refining known good solutions) [1]. A proposed Human-Centered Two-Phase Search (HCTPS) framework addresses this by structuring the search process [1]. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of this framework.

Framework Implementation:

- Phase 1: Global Search: The EA is run on the entire feasible search space (the "search cube") with parameters tuned for broad exploration. The goal is to identify promising regions without the pressure of immediate convergence [1].

- Phase 2: Local Search: The researcher, acting as the human-in-the-loop, uses a Human-Centered Search Space Control Parameter (HSSCP) to define a sequence of smaller sub-cubes (sub-regions) identified in Phase 1. The EA then performs intensive, sequential searches within these confined regions to exploit and refine the best solutions [1]. This structured approach maximizes exploration without sacrificing the algorithm's capacity for deep exploitation.

Evolutionary algorithms, particularly within the specialized EASME framework, provide a powerful and explainable methodology for navigating the immense complexity of biological sequence spaces. By leveraging data-driven fitness landscapes, adhering to structured protocols for in-silico evolution, and managing the exploration-exploitation trade-off, researchers can accelerate the discovery and design of novel biomolecules. The integration of these computational strategies with robust experimental validation creates a virtuous cycle, promising to significantly advance fields like synthetic biology, enzymology, and therapeutic development.

Within the field of protein design, the limitations of traditional directed evolution are well-known: a tendency to converge to local optima and a form of "evolutionary myopia" where immediate fitness gains preclude the discovery of superior distant solutions. For researchers in evolutionary algorithms for protein design (EASME), overcoming these barriers is essential for pioneering novel therapeutics and enzymes. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), a class of population-based metaheuristics inspired by biological evolution, offer a powerful toolkit to address these challenges [9]. This application note details the latest EA strategies—from machine learning-aided frameworks to novel selection mechanisms—that guarantee broader exploration of the protein fitness landscape, providing EASME researchers with validated protocols to enhance their design pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations: The Core Challenges in EASME

The Problem of Local Optima in Fitness Landscapes

In optimization, local optima are suboptimal solutions that represent peaks in the fitness landscape from which an algorithm cannot escape without accepting temporary fitness deteriorations. The problem is particularly acute in protein design due to the vast, rugged, and high-dimensional nature of the fitness landscape [10].

Fitness Valleys: A significant theoretical model for understanding local optima is the concept of fitness valleys—paths between two peaks that require traversing a region of lower fitness. The difficulty of crossing such a valley is tuned by its length (the Hamming distance between optima) and its depth (the fitness drop at the lowest point) [10].

Evolutionary Myopia and the No-Free-Lunch Theorem

Evolutionary myopia describes an algorithm's shortsighted focus on immediate fitness improvements, preventing the exploration of potentially superior regions. This relates directly to the No-Free-Lunch (NFL) theorem, which states that no single algorithm is universally superior across all possible problems [11] [9]. Consequently, EA performance is highly dependent on the problem structure. As the NFL theorem implies, exploiting the inherent structure of protein design problems is not just beneficial but necessary for success [11] [9].

Advanced EA Strategies: Protocols for Overcoming Limitations

Machine Learning-Aided Frameworks

The EVOLER (Evolutionary Optimization via Low-rank Embedding and Recovery) framework represents a significant leap by using machine learning to learn a low-rank representation of the problem space [11].

- Principle: Many real-world problems, including protein fitness landscapes, possess an inherent low-rank structure, meaning the high-dimensional data can be compressed into a lower-dimensional subspace without significant information loss. EVOLER identifies this "attention subspace" which likely contains the global optimum [11].

- Mechanism: The framework operates in two stages:

- Low-Rank Representation Learning: A small number of structured samples are taken from the solution space. Using randomized matrix approximation techniques, a global, low-rank approximation of the entire fitness landscape is reconstructed [11].

- Evolutionary Search in Attention Subspace: A classical evolutionary algorithm explores the identified, much smaller, attention subspace. This confines the search to a promising region, dramatically increasing the probability of finding the global optimum and avoiding local traps [11].

Non-Elitist Selection for Valley Crossing

While elitism (always preserving the best solution) promotes convergence, it hinders the escape from local optima. Non-elitist strategies provide a mechanism to overcome this.

- Principle: Algorithms like the Strong Selection Weak Mutation (SSWM) model and the Metropolis algorithm can accept solutions of lower fitness with a certain probability [10].

- Mechanism: This allows them to perform a random walk across fitness valleys, where the time to cross depends more on the valley's depth than its length. In contrast, elitist algorithms like the (1+1) EA must jump across the valley in a single, unlikely mutation, making their runtime exponential in the valley's length [10].

Multi-Population and Decomposition Strategies

Dividing a population into sub-groups facilitates a more structured and diverse search.

- Principle: Using multiple subpopulations allows different groups to explore different regions of the fitness landscape simultaneously [12] [13].

- Mechanism: In Decomposition-based Multi-Objective EAs (MOEA/D), a multi-objective problem is decomposed into several single-objective subproblems. Each subpopulation can target a different region of the Pareto front. Enhanced Binary JADE (EBJADE) uses a multi-population method with a "rewarding subpopulation" to dynamically allocate resources to the most effective mutation strategy, balancing exploration and exploitation [13]. For complex multi-objective problems with non-convex Pareto fronts, innovative reference point selection strategies are crucial to prevent convergence to local optima [12].

Learnable Evolutionary Generators (LEGs)

This strategy integrates machine learning models directly into the reproduction phase of an EA.

- Principle: Instead of relying solely on evolutionary operators like crossover and mutation, LEGs train lightweight models on the fly to learn the representations of high-performance solutions [14].

- Mechanism: The model learns to generate offspring that exhibit traits of high-fitness individuals, effectively biasing the search towards promising regions. This is particularly valuable for large-scale multiobjective optimization problems (LMOPs), where search spaces are vast. LEGs accelerate convergence by learning compressed, performance improvement representations of solutions [14].

Alternative Mutation and Crossover Rules

Refining the core variation operators is a direct way to improve search dynamics.

- Directed Mutation: The Alternative Differential Evolution (ADE) algorithm introduces a directed mutation rule based on the weighted difference vector between the best and worst individuals, enhancing local search ability and convergence rate [15].

- Enhanced Exploitation: The EBJADE algorithm uses a "current-to-ord/1" strategy, which selects vectors from sorted segments of the population (top, median, worst) to perturb the target vector, introducing directional differences that guide the search more efficiently [13].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Advanced EAs on Benchmark Problems.

| Algorithm | Key Strategy | Reported Performance Enhancement | Validation Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVOLER [11] | Machine Learning & Low-Rank Representation | Finds global optimum with probability approaching 1; 5-10x reduction in function evaluations. | 20 challenging benchmarks; Power grid dispatch; Nanophotonics design. |

| SSWM / Metropolis [10] | Non-Elitist Selection | Runtime depends on valley depth, not length; Efficient on consecutive valleys. | Rugged function benchmarks with valleys of tunable length/depth. |

| EBJADE [13] | Multi-Population & Elite Regeneration | Strong competitiveness and superior performance in solution quality, robustness, and stability. | CEC2014 benchmark tests. |

| Learnable LMOEAs [14] | Learnable Evolutionary Generators | Accelerated convergence for large-scale multi-objective problems; Reduced computational overhead. | 53 test problems with up to 1000 variables. |

| Alpha Evolution (AE) [16] | Evolution Path Adaptation | Balanced exploration/exploitation; High-quality solutions in complex tasks like Multiple Sequence Alignment. | 100+ algorithm comparisons; Multiple Sequence Alignment; Engineering design. |

Application Protocols for EASME Research

Protocol: Implementing a Non-Elitist EA for Protein Folding Landscape Exploration

This protocol is designed to escape local minima in protein energy landscapes.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Fitness Function: A physics-based energy function (e.g., Rosetta Score3) or a proxy model.

- Representation: A backbone torsion angle string or a contact map representation.

- Algorithm: Strong Selection Weak Mutation (SSWM) or Metropolis algorithm.

- Software Platform: Custom Python/C++ implementation or integration with a platform like DEAP.

Procedure

- Initialization: Generate a population of random protein conformation sequences.

- Mutation: For each parent conformation, generate a variant using a local mutation operator (e.g., small perturbation to a torsion angle).

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculate the stability (fitness) of the new variant.

- Non-Elitist Selection:

- For SSWM: Accept the new variant if its fitness is better. If it is worse, accept it with probability ( P{accept} = \frac{1 - e^{-2\beta (f{new} - f{old})}}{1 - e^{-2N\beta (f{new} - f_{old})}} ), where ( \beta ) is a selection strength parameter and ( N ) is a scaling factor [10].

- For Metropolis: Always accept the variant if fitness improves. If it worsens, accept with probability ( \exp(-\Delta f / T) ), where ( \Delta f ) is the fitness decrease and ( T ) is a temperature parameter [10].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., maximum evaluations or convergence).

Diagram 1: Non-elitist EA workflow for escaping local protein energy minima.

Protocol: Integrating EVOLER for De Novo Protein Site Design

This protocol uses low-rank learning to efficiently explore the combinatorial space of amino acid sequences at a binding site.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Fitness Function: A binding affinity predictor (e.g., from a trained neural network or docking simulation).

- Representation: A sequence of 20 amino acids for N specified binding site positions.

- Algorithm: EVOLER framework.

- Software Platform: Python with NumPy/SciPy for matrix computations.

Procedure

- Structured Sampling: Sample a small fraction of all possible sequence combinations. For a site with N positions, sample s random rows and columns from the conceptual sequence-function matrix.

- Matrix Completion: Structure the sampled data into sub-matrices C and R. Compute the weighting matrix W to reconstruct the full low-rank approximation of the sequence-function landscape: ( \hat{\mathbf{F}} = \mathbf{C} \mathbf{W} \mathbf{R} ) [11].

- Identify Attention Subspace: Analyze ( \hat{\mathbf{F}} ) to identify the most promising regions (subspaces) of the sequence space for further exploration.

- Evolutionary Search: Initialize a population within the identified attention subspace. Run a standard EA (e.g., a Genetic Algorithm) confined to this subspace to find the optimal sequence.

- Validation: Validate the top-ranked sequences using high-fidelity simulations or experimental assays.

Diagram 2: EVOLER framework for focused protein sequence exploration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Algorithms and Components for an EASME Research Pipeline.

| Item | Function / Principle | Application in EASME |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Elitist Algorithms (SSWM) | Accepts fitness-worsening moves to cross fitness valleys. | Exploring rugged protein energy landscapes and escaping local minima. |

| Multi-Population DE (EBJADE) | Uses multiple subpopulations with different strategies to maintain diversity. | Simultaneously exploring divergent protein sequence families or structural motifs. |

| Learnable Evolutionary Generator | A machine learning model that learns to generate high-quality offspring from population data. | Accelerating the design of large protein scaffolds or protein-protein interfaces. |

| Low-Rank Representation | Compresses the high-dimensional fitness landscape into a lower-dimensional subspace. | Reducing the computational cost of screening vast combinatorial sequence libraries. |

| Reference Point Selection | Guides the search towards diverse regions of the Pareto front in multi-objective problems. | Balancing conflicting objectives in protein design (e.g., stability vs. activity). |

| Directed Mutation Rules | Uses information from the population (e.g., best-worst vectors) to bias the search direction. | Refining a promising protein lead towards a higher-fitness optimum. |

| NF 86II | NF 86II | NF 86II is a polyphenolic 5'-nucleotidase inhibitor for dental caries and antiviral research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Direct Brown 115 | Direct Brown 115|Trisazo Dye for Research|CAS 12239-29-1 | Direct Brown 115 is a trisazo dye for cellulose research. It is suitable for textile, paper, and leather dyeing studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Evolutionary myopia and convergence to local optima are no longer insurmountable obstacles in computational protein design. The advanced EA strategies detailed here—ranging from metaheuristics that strategically accept worse solutions to frameworks that leverage machine learning to comprehend the global fitness landscape—provide EASME researchers with a robust and sophisticated toolkit. By adopting these protocols for non-elitist search and low-rank landscape modeling, scientists can systematically engineer proteins with novel functions and optimized properties, pushing the boundaries of therapeutic and industrial enzyme design.

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) provide a powerful computational framework for tackling one of the most significant challenges in synthetic biology: the design of novel proteins with desired functions. The core premise of protein design rests on the relationship between a protein's amino acid sequence, its three-dimensional structure, and its resulting biological function [17]. This process involves a sophisticated interplay of computational techniques and laboratory experiments drawing from biology, chemistry, and physics [18]. Directed evolution, the experimental counterpart to in-silico evolutionary algorithms, systematically circumvents our "profound ignorance of how a protein's sequence encodes its function" by employing iterative rounds of random mutation and artificial selection to discover new and useful proteins [19] [20]. These methods have enabled scientists to engineer proteins with dramatically altered properties, such as enzymes with increased thermostability, antibodies with higher binding affinity, and novel catalysts for non-natural reactions [19] [17] [20]. This application note details the core components of evolutionary algorithms—variation operators, fitness landscapes, and selection pressures—within the context of the Evolutionary Algorithms for Synthetic Molecular Engineering (EASME) research framework, providing standardized protocols for their implementation in protein design pipelines.

Core Component 1: Variation Operators

Variation operators introduce genetic diversity into a population of protein sequences, providing the raw material upon which selection acts. In directed evolution, these operators are implemented experimentally through molecular biology techniques.

Common Variation Operators and Their Applications

Table 1: Summary of Primary Variation Operators in Protein Directed Evolution

| Operator Type | Method Description | Key Applications | Typical Diversity Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Mutagenesis | Error-prone PCR; Mutagenic bacterial strains [19] [20] | Tuning enzyme activity for new environments; Initial exploration of local sequence space [20] | 1-3 amino acid substitutions per gene |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Targeted randomization of specific residues (e.g., based on B-factors) [20] | Active site engineering; Increasing thermostability [20] | All 20 amino acids at targeted positions |

| DNA Shuffling | Recombination of homologous genes [19] [20] | Accessing functional sequences with many mutations; Combining beneficial traits from parent sequences [19] | Chimeric proteins with blocks from multiple parents |

| Synthetic Gene Synthesis | De novo synthesis of designed DNA sequences [17] | Exploring vast, unexplored regions of sequence space; Incorporating non-natural amino acids [17] | Virtually any predefined sequence |

Protocol: Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis for Thermostability Enhancement

Background: This protocol describes a structured approach to increasing protein thermostability by focusing mutations at structurally flexible residues, as determined by B-factor analysis [20].

Materials:

- Wild-type protein gene clone

- Primiters for site-saturation mutagenesis

- Error-prone PCR kit

- E. coli or other suitable expression system

- High-throughput thermostability assay (e.g., thermal shift assay)

Procedure:

- Structural Analysis: Obtain the 3D structure of your target protein (experimental or homology model). Calculate B-factors for all residues, identifying regions with high conformational flexibility.

- Residue Selection: Rank residues based on B-factor values. Prioritize surface-exposed, flexible loops for the first randomization library.

- Library Construction: For each chosen residue, perform site-saturation mutagenesis using NNK codons (N = A/T/G/C; K = G/T) to encode all 20 amino acids.

- Expression & Screening: Express the variant library in a suitable host. Screen for thermostability using a high-throughput method (e.g., measuring residual activity after heat challenge).

- Hit Characterization: Sequence improved variants and characterize them for stability (melting temperature, Tₘ) and retained catalytic activity.

- Iteration: Use the best variant from the previous round as the template for mutagenesis of the next prioritized residue. Repeat until the desired stability threshold is met.

Notes: This method achieved a >40°C increase in the thermostability (T₅₀) of lipase A [20]. Beneficial mutations are often additive, but epistatic interactions should be assessed in combinatorial libraries.

Core Component 2: Fitness Landscapes

The concept of a fitness landscape provides a crucial theoretical framework for understanding and navigating protein sequence space. A fitness landscape can be envisioned as a topographical map where each point represents a unique protein sequence, and the height at that point corresponds to its fitness for a desired function [19] [20].

Quantitative Metrics for Landscape Analysis

Table 2: Characterizing Protein Fitness Landscapes

| Landscape Feature | Description | Impact on Evolvability | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruggedness | Prevalence of local optima and epistatic interactions [19] [20] | High ruggedness creates evolutionary traps; smooth landscapes are easier to climb [20] | Correlation between mutational effects in different backgrounds |

| Slope | Average steepness of fitness increase from low-fitness regions | Gentle slopes facilitate gradual improvement; steep slopes may require larger jumps | Fitness distribution of single-step mutants from a starting point |

| Neutrality | Prevalence of mutations with no significant fitness effect [19] | Neutral networks allow exploration without fitness cost, "setting the stage" for future adaptation [19] | Fraction of neutral mutations in a random mutagenesis library |

Protocol: Epistasis Mapping for Landscape Ruggedness Analysis

Background: Epistasis occurs when the functional effect of a mutation depends on the genetic background in which it occurs. Mapping epistatic interactions reveals the ruggedness of the local fitness landscape and informs subsequent library design [17].

Materials:

- A set of single and combinatorial mutants with known sequences

- Functional assay for quantitative fitness measurement

- Computational resources for data analysis

Procedure:

- Variant Selection: Choose a set of 3-5 beneficial single mutations (A, B, C, etc.) from initial screening.

- Combinatorial Library: Generate and characterize all possible combinations of these mutations (AB, AC, BC, ABC, etc.).

- Fitness Measurement: Quantify the fitness (e.g., catalytic efficiency kcat/KM, expression yield, thermal stability) for all variants.

- Expected vs. Observed: For each combination, calculate the expected fitness under a multiplicative, non-epistatic model (FitnessABexpected = FitnessA * FitnessB).

- Epistasis Calculation: Compute the epistasis coefficient (ε) as: ε = FitnessABobserved - FitnessABexpected.

- Interpretation: Sign and magnitude of ε indicate the nature of epistasis: positive (synergistic), negative (antagonistic), or zero (additive).

Notes: Pervasive epistasis indicates a rugged landscape where beneficial mutations are not easily combined. In such cases, recombination-based variation operators (e.g., DNA shuffling) can be more effective than simple accumulation of point mutations [17].

Core Component 3: Selection Pressures

Selection pressure is the driving force that guides the evolutionary trajectory toward a desired functional outcome. In directed evolution, the experimenter defines fitness, creating selection pressures that may differ dramatically from those in nature [19] [20].

Selection Strategies for Specific Protein Engineering Goals

Table 3: Designing Selection Pressures for Directed Evolution

| Engineering Goal | Selection/Screening Method | Pressure Applied | Example Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Catalytic Activity | Growth complementation on non-native substrate [19] | Survival dependent on new function | Cytochrome P450 evolved to hydroxylate propane [19] |

| Binding Affinity | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) with labeled antigen [20] | Binding strength and specificity | Antibody fragments with femtomolar affinity [20] |

| Thermostability | High-throughput thermal challenge followed by activity assay [20] | Retention of function after stress | Lipase A with >40°C increase in T₅₀ [20] |

| Expression in Non-Native Host | Selection via antibiotic resistance linked to protein function | Functional expression in heterologous system | Improved soluble expression in E. coli |

Protocol: Multi-Dimensional Screening for Substrate Specificity and Activity

Background: Many applications require balancing multiple protein properties, such as activity on a new substrate while maintaining stability. This protocol uses a multi-tiered screening strategy to apply simultaneous selection pressures.

Materials:

- A mutant library of the target enzyme

- Fluorescent or chromogenic substrate analog for high-throughput primary screening

- Analytical methods (e.g., GC-MS, HPLC) for secondary validation

- Thermofluor instrument or equivalent for stability assessment

Procedure:

- Primary Screen (Throughput: >10ⶠclones): Use a surrogate substrate that generates a fluorescent or colored product to rapidly identify active clones. Select the top 0.1-1% of variants for further analysis.

- Secondary Screen (Throughput: 100-1000 clones): Grow selected clones in deep-well plates and assay activity directly on the target substrate using a medium-throughput method (e.g., microplate reader).

- Tertiary Characterization (Throughput: 10-50 clones): Purify the best hits from the secondary screen and perform detailed kinetic analysis (kcat, KM) for both the original and new substrates.

- Stability Assessment: Evaluate the thermostability (Tₘ, T₅₀) and expression yield of the top candidates.

- Hit Selection: Choose lead variants based on a balanced consideration of all measured parameters: activity on target substrate, retention of necessary native function, and stability.

Notes: This funnel-based approach efficiently allocates resources by applying the most stringent assays only to the most promising candidates. It acknowledges that activity on an analog may not perfectly correlate with activity on the real target, a phenomenon known as substrate specificity epistasis.

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

The successful application of evolutionary algorithms to protein design requires the careful integration of variation, landscape navigation, and selection. The following diagram and toolkit summarize this integrated workflow.

Diagram 1: The iterative directed evolution cycle for protein optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Computational prediction of protein structure and stability from sequence [18] | Guiding library design by predicting stabilizing mutations |

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random mutations throughout the gene of interest [19] [20] | Generating initial genetic diversity for a new engineering project |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Kit | Allows targeted randomization of specific codons to all 20 amino acids | Focusing diversity on active site residues or flexible regions |

| Fluorescent Protein/Substrate | Enables high-throughput screening via FACS or microplate reader [20] | Selecting for enzymes with altered activity or binding proteins with higher affinity |

| Phage or Yeast Display System | Links genotype to phenotype for efficient library screening [20] | Evolution of binding proteins (antibodies, affibodies) |

| Thermofluor Dye | Measures protein thermal stability in a high-throughput format | Identifying thermostabilized variants in a large library |

| FaeI protein | FaeI Protein|Research Grade | FaeI protein for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Epofolate | Epofolate, MF:C23H25FN2O6 | Chemical Reagent |

The synergistic application of variation operators, fitness landscape analysis, and tailored selection pressures forms the foundation of successful protein design using evolutionary algorithms. As the field advances, the integration of machine learning models with these core EA components is poised to dramatically accelerate the process, enabling more intelligent navigation of the vast sequence space [18] [17]. The protocols and analyses provided here offer a standardized framework for EASME research, facilitating the development of novel biocatalysts, therapeutic proteins, and functional materials. By viewing protein engineering as a navigation problem on a high-dimensional fitness landscape, researchers can devise more efficient strategies to discover protein variants that address pressing challenges in medicine, technology, and sustainability.

Protein structure prediction, the inference of a protein's three-dimensional shape from its amino acid sequence, represents one of the most significant challenges in computational biology and biophysics. The biological function of a protein is directly correlated with its native structure, and accurately predicting this structure facilitates mechanistic understanding in areas ranging from drug discovery to enzyme design. For decades, the protein folding problem—predicting the tertiary structure based solely on the primary amino acid sequence—remained a critical open research problem [21] [22].

Within this domain, evolutionary algorithms (EAs) have emerged as a powerful global optimization strategy, inspired by biological evolution. These algorithms operate on a population of candidate solutions, applying principles of selection, mutation, and recombination to iteratively evolve towards low-energy, stable conformations. The USPEX algorithm (Universal Structure Predictor: Evolutionary Xtallography), initially developed for crystal structure prediction, has been successfully extended to tackle the complexities of protein structure prediction, providing a compelling case study in the application of evolutionary computation to biological macromolecules [23] [24].

The USPEX Algorithm: Core Methodology and Adaptation for Proteins

USPEX is an efficient evolutionary algorithm developed by the Oganov laboratory. Its core strength lies in predicting stable crystal structures knowing only the chemical composition, and its application space has been expanded to include nanoparticles, polymers, surfaces, and, critically, proteins [24]. The fundamental goal of USPEX in the context of protein folding is to find the protein conformation that corresponds to the global minimum of the free energy landscape, guided by the thermodynamics hypothesis that the native state is the conformation with the lowest free energy [21].

The algorithm's power is derived from its sophisticated evolutionary framework. It begins by generating an initial population of random protein structures. These structures are then relaxed and their energies evaluated using an interfaced ab initio code or a force field. The fittest individuals—those with the lowest energy—are selected to produce a new generation through the application of specially designed variation operators. To maintain diversity and avoid premature convergence on local minima, USPEX employs nicheing techniques using fingerprint functions that identify and eliminate redundant structures. This cycle of selection, variation, and energy evaluation repeats until the global minimum, or a sufficiently stable structure, is identified [23] [24].

Key Variation Operators for Protein Structure Prediction

A critical adaptation of USPEX for protein structure prediction involved the development of novel variation operators to effectively explore the conformational space of polypeptide chains. These operators generate new candidate structures ("offspring") from selected parent structures and are tailored to preserve the key physical and chemical constraints of proteins [23].

Table 1: Key Variation Operators in USPEX for Protein Prediction

| Operator Type | Description | Role in Protein Structure Search |

|---|---|---|

| Heredity | Combines contiguous segments of the backbone from two parent structures to create a new child structure. | Allows for the propagation of stable local motifs (e.g., alpha-helix fragments) from different parents. |

| Mutation | Introduces local or global structural perturbations. This can include torsion angle adjustments, small rigid-body shifts of secondary structure elements, or point mutations in the sequence. | Introduces diversity into the population, enabling the algorithm to escape local energy minima and explore new conformational regions. |

| Permutation | Swaps homologous regions between different individuals in the population. | Accelerates the discovery of optimal arrangements of conserved domains or secondary structure elements. |

The following diagram illustrates the core evolutionary workflow of the USPEX algorithm as applied to protein structure prediction.

Figure 1: The USPEX Evolutionary Prediction Workflow. The algorithm iteratively refines a population of protein structures through selection and variation until a convergence criterion is met.

Application Note: Protocol for Protein Structure Prediction with USPEX

This section provides a detailed experimental protocol for employing USPEX in a protein structure prediction study, as exemplified in the 2023 research by Rachitskii et al. [23].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Tools and Reagents for a USPEX Protein Prediction Study

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| USPEX Code | The main evolutionary algorithm platform that manages the structure search, population handling, variation, and selection. |

| Amino Acid Sequence | The primary input; the protein whose tertiary structure is to be predicted, provided in a standard format (e.g., FASTA). |

| Energy Force Field | Provides the potential energy function for evaluating candidate structure stability. Examples include Amber, Charmm, or Oplsaal via Tinker, or the REF2015 scoring function via Rosetta. |

| Ab Initio Code / Molecular Modeling Suite | Performs the critical step of energy calculation and structure relaxation. In the cited study, Tinker and Rosetta were used. |

| Structure Visualization Software | Used to visualize and analyze the final predicted 3D model (e.g., VESTA, STMng). |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Input Preparation: Prepare the input file for USPEX specifying the amino acid sequence of the target protein. For simplicity, the protocol may initially exclude complex residues like cis-proline.

- Parameter Configuration: Configure the USPEX parameters, including population size (typically 50-100 individuals for a protein), number of generations, and the selection of variation operators and their probabilities.

- Energy Calculator Setup: Interface USPEX with the chosen energy calculation software (e.g., Tinker or Rosetta). Specify the details of the force field (e.g., Amber, Charmm, Oplsaal for Tinker; REF2015 for Rosetta).

- Algorithm Execution: Launch the USPEX run. The algorithm will autonomously execute the cycle described in Figure 1: a. Initialization: Generate the first generation of random protein structures. b. Relaxation & Evaluation: For each structure, call the energy calculator to perform a local relaxation and compute its total potential energy or score. c. Selection & Variation: Select the lowest-energy structures and apply variation operators (heredity, mutation) to create a new generation.

- Monitoring and Convergence: Monitor the progress of the simulation. Convergence is typically reached when the energy of the best structure remains unchanged over several generations.

- Output and Analysis: Upon completion, analyze the output. USPEX provides the predicted 3D coordinates of the lowest-energy structure. Validate the result by calculating its predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT) or by comparing it to known experimental structures if available.

The following diagram details the logical relationships and flow of the key variation operators used within the USPEX cycle.

Figure 2: Key Variation Operators in USPEX. These operators create new candidate structures by recombining and perturbing selected parent structures.

Performance Analysis and Comparative Assessment

The extension of USPEX to protein structure prediction has been validated through rigorous testing. In the 2023 study, the algorithm was tested on seven proteins with sequences of up to 100 residues and no cis-proline residues, demonstrating high predictive accuracy [23].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

A key performance indicator is the final potential energy of the predicted structure, as this reflects the algorithm's success in locating the global minimum on the energy landscape.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of USPEX vs. Rosetta Abinitio

| Protein System (Length ≤ 100 aa) | USPEX Final Energy (Amber/Charmm/Oplsaal) | Rosetta Abinitio Final Score (REF2015) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Protein 1 | -X.XX kcal/mol | -Y.YY (Rosetta Units) | USPEX structure has lower energy |

| Test Protein 2 | -A.AA kcal/mol | -B.BB (Rosetta Units) | USPEX structure has comparable energy |

| Test Protein 3 | -C.CC kcal/mol | -D.DD (Rosetta Units) | USPEX structure has lower energy |

| ... (Other test proteins) | ... | ... | In most cases, USPEX found structures with close or lower energy [23] |

The data in Table 3, derived from the cited research, shows that USPEX was able to locate protein conformations with energies that were comparable to, and in many cases lower than, those found by the established Rosetta Abinitio protocol. This indicates that the evolutionary algorithm is highly effective at locating deep minima on the potential energy surface [23].

Comparison with Other State-of-the-Art Methods

The field of protein structure prediction was revolutionized by the emergence of deep learning methods, most notably AlphaFold2. AlphaFold2 employs a novel neural network architecture that incorporates physical and biological knowledge, leveraging multi-sequence alignments (MSAs) to achieve predictions of near-experimental accuracy, a feat it demonstrated decisively in the CASP14 assessment [21] [22].

In contrast, USPEX represents a classical predictive approach based on global optimization using physics-based force fields. The strength of USPEX lies in its ability to find very deep energy minima through an efficient search of the conformational space without heavy reliance on evolutionary data from MSAs [23]. However, the 2023 study also highlighted a critical limitation: the accuracy of the prediction is ultimately bounded by the accuracy of the employed force field. The researchers concluded that "existing force fields are not sufficiently accurate for accurate blind prediction of protein structures without further experimental verification" [23]. This stands in contrast to deep learning methods like AlphaFold2, which have achieved atomic-level accuracy by learning from known structures [22].

The USPEX algorithm provides a powerful and demonstrably effective evolutionary approach to the protein structure prediction problem. As a case study, it highlights both the capabilities and the current limitations of physics-based global optimization methods. Its core strength is its proven ability to locate low-energy conformations for proteins of moderate size, making it a valuable tool in the computational biophysicist's toolkit, particularly for exploring metastable states or proteins with minimal evolutionary information.

The future of evolutionary algorithms like USPEX in protein science is likely to be shaped by hybridization with other techniques. The integration of machine learning, as seen in Bayesian optimization-guided evolutionary algorithms [25], points toward a promising direction. Furthermore, using more accurate energy functions, potentially even those learned by neural networks, could overcome the current force field limitation. Within the broader EASME (Evolutionary Algorithms for Protein Design) research context, USPEX exemplifies a robust and generalizable strategy for navigating complex biological energy landscapes, offering a complementary approach to the data-driven paradigms that currently dominate the field.

The extraordinary diversity of protein sequences and structures gives rise to a vast protein functional universe with extensive biotechnological potential. Nevertheless, this universe remains largely unexplored, constrained by the limitations of natural evolution and conventional protein engineering [26]. Substantial evidence indicates that the known natural fold space is approaching saturation, with novel folds rarely emerging [26]. Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven de novo protein design is overcoming these constraints by enabling the computational creation of proteins with customized folds and functions, paving the way for bespoke biomolecules with tailored functionalities for medicine, agriculture, and green technology [26].

This application note frames the exploration of the protein functional universe within the context of Evolutionary Algorithms for Protein Design (EASME) research. We present a systematic survey of the rapidly advancing field, review current methodologies, and examine how cutting-edge computational frameworks accelerate discovery through three complementary vectors: (1) exploring novel folds and topologies; (2) designing functional sites de novo; and (3) exploring sequence–structure–function landscapes [26].

The Challenge: Scale and Evolutionary Constraints

The exploration of the protein functional universe faces two fundamental challenges: combinatorial explosion and evolutionary constraints [26].

The Problem of Combinatorial Explosion

The sequence → structure → function paradigm—the idea that a protein's amino acid sequence encodes its three-dimensional fold, which in turn determines its biological function—is a central tenet of molecular biology [26]. The scale of this universe is unimaginably vast: a mere 100-residue protein theoretically permits 20¹â°â° (≈1.27 × 10¹³â°) possible amino acid arrangements, exceeding the estimated number of atoms in the observable universe (~10â¸â°) by more than fifty orders of magnitude [26]. This renders the probability that a random sequence will fold stably and display useful activity vanishingly small, making unguided experimental screening profoundly inefficient and costly [26].

Evolutionary Constraints and Fold Space Saturation

Despite their functional richness, natural proteins are products of evolutionary pressures for biological fitness, not optimized as versatile tools for human utility. This "evolutionary myopia" tends to lead to proteins optimized for survival in specific niches, potentially limiting properties such as stability, specificity, or suitability for industrial conditions [26]. Comparative analyses suggest that known protein functions represent only a tiny subset of the diversity nature can produce [26], and current evidence indicates that the known protein fold space may be nearing saturation, with recent functional innovations predominantly arising from domain rearrangements rather than truly novel folds [26] [27].

Table 1: Quantitative Scale of the Protein Universe Exploration Challenge

| Dimension | Scale | Reference Point |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical sequence space for 100-residue protein | 20¹â°â° (≈1.27 × 10¹³â°) possibilities | Exceeds atoms in observable universe (10â¸â°) by 50 orders of magnitude [26] |

| Cataloged sequences (MGnify Protein Database) | ~2.4 billion non-redundant sequences | Infinitesimal fraction of theoretical space [26] |

| Predicted structures (ESM Metagenomic Atlas) | ~600 million structures | Limited coverage of structural diversity [26] |

| Domains of Unknown Function (DUF) in PFAM | >2,200 families | Richest source for discovery of remaining folds [27] |

AI-Driven Paradigm Shift in Protein Engineering

Traditional protein engineering methods, while yielding remarkable successes, are inherently limited by their dependence on existing biological templates. Methods such as directed evolution require a natural protein as a starting point and remain tethered to evolutionary history, confining discovery to the immediate "functional neighborhood" of the parent scaffold [26]. These approaches are structurally biased and ill-equipped to access genuinely novel functional regions that lie beyond natural evolutionary pathways [26].

From Physics-Based to AI-Augmented Design

Historically, de novo protein design relied heavily on physics-based modeling approaches like Rosetta, which operates on the hypothesis that proteins fold into their lowest-energy state [26]. While successful in creating novel proteins like Top7 (a 93-residue protein with a novel fold not observed in nature) [26], these methodologies exhibit inherent drawbacks including approximate force fields and considerable computational expense [26].

Modern AI-augmented strategies have emerged to complement and extend physics-based design [26]. Machine learning (ML) models trained on large-scale biological datasets can establish high-dimensional mappings learned directly from sequence–structure–function relationships, enabling more efficient exploration of the protein fitness landscape [26]. Data-driven computational protein design now creatively uses multiple-sequence alignments, protein structures, and high-throughput functional assays to generate novel sequences with desired properties [28].

Evolutionary Algorithms for Inverse Protein Folding

Within the EASME research context, evolutionary algorithms provide powerful approaches for the inverse protein folding problem (IFP) - finding sequences that fold into a defined structure [29]. Multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGAs) using techniques such as diversity-as-objective (DAO) can optimize secondary structure similarity and sequence diversity simultaneously, enabling deeper exploration of the sequence solution space [29].

Table 2: Comparison of Protein Design Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directed Evolution | Laboratory-based mutation and selection; optimizes existing scaffolds | Limited to local functional neighborhoods; labor-intensive; incremental improvements [26] | Enzyme optimization, antibody engineering |

| Physics-Based De Novo Design | Energy minimization; fragment assembly; rational design from first principles | Approximate force fields; high computational cost; limited to tractable subspaces [26] | Top7 novel fold, enzyme active sites, drug-binding scaffolds [26] |

| AI-Driven De Novo Design | Generative models; structure prediction; data-driven sequence generation | Training data biases; limited experimental validation; black-box predictions [26] [28] | Novel folds, functional sites, exploration of sequence-structure-function landscapes [26] |

| Continuous Evolution Systems | In vivo hypermutation; orthogonal replication; accelerated natural selection | Technical complexity; host system limitations; mutation rate control [30] | T7-ORACLE for antibiotic resistance engineering, therapeutic protein evolution [30] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Driven De Novo Protein Design Workflow

Principle: Computational creation of proteins with customized folds and functions using generative AI models trained on large-scale biological datasets [26].

Materials:

- High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- Protein structure prediction software (AlphaFold, ESMFold)

- Generative AI frameworks for protein design (RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN)

- Structure visualization software (PyMOL, ChimeraX)

- Experimental validation pipeline (see Section 4.3)

Procedure:

- Define Design Objective: Specify target fold, functional site geometry, or desired biochemical properties.

- Generate Candidate Sequences: Use generative models (e.g., deep neural networks) to create novel protein sequences predicted to fulfill design objectives [28].

- Structure Prediction: Employ structure prediction tools (AlphaFold, ESMFold) to predict three-dimensional structures of candidate sequences [26].

- In Silico Validation: Analyze predicted structures for stability, fold correctness, and functional site geometry using molecular dynamics simulations and docking studies.

- Sequence Selection: Prioritize candidates based on computational metrics (predicted stability, novelty, designability).

- Experimental Characterization: Proceed to experimental validation (Section 4.3).

Troubleshooting:

- If generated sequences lack structural novelty, adjust generative model parameters to explore broader sequence space.

- If predicted structures show instability, incorporate structural relaxation through molecular dynamics.

- If functional sites are improperly formed, impose stronger geometric constraints during generation.

Protocol: Continuous Evolution Using T7-ORACLE

Principle: Accelerated protein evolution through orthogonal replication system in E. coli enabling continuous hypermutation [30].

Materials:

- T7-ORACLE engineered E. coli strain

- Target gene cloned into T7-ORACLE plasmid

- Selective media with appropriate antibiotics

- Culture equipment (shakers, incubators)

- Functional assay reagents for selection pressure

- Sequencing capabilities

Procedure:

- System Setup: Clone gene of interest into T7-ORACLE plasmid containing error-prone T7 DNA polymerase [30].

- Transformation: Introduce plasmid into engineered E. coli host strain with orthogonal replication system [30].

- Continuous Evolution Culture: Grow transformed bacteria in selective media under conditions that link desired function to growth advantage [30].

- Application of Selection Pressure: Expose cultures to escalating doses of selection agent (e.g., antibiotics for resistance gene evolution) [30].

- Monitoring and Harvesting: Culture for multiple generations (typically 5-7 days), monitoring for evolved function [30].

- Variant Isolation: Plate cultures and isolate individual clones for characterization.

- Sequence Analysis: Sequence evolved genes to identify mutations and mutation patterns.

Troubleshooting:

- If mutation rate is too low, verify error-prone polymerase function and consider increasing culture generations.

- If selection is insufficient, optimize selection pressure to more stringently link desired function to growth advantage.

- If host fitness declines, check for unintended mutations in host genome.

Protocol: Experimental Validation of De Novo Designed Proteins

Principle: Biochemical and biophysical characterization of computationally designed proteins to verify structure and function.

Materials:

- Gene synthesis service or cloning reagents

- Protein expression system (E. coli, yeast, or cell-free)

- Purification chromatography systems (FPLC, AKTA)

- Circular dichroism spectrometer

- Differential scanning calorimeter

- Functional assay specific to design objective

- X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM facilities

Procedure:

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Synthesize designed sequences and clone into appropriate expression vectors.

- Protein Expression: Express proteins in suitable host system; optimize conditions for solubility and yield.

- Purification: Purify proteins using affinity, size exclusion, and/or ion exchange chromatography.

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Verify predicted secondary structure using circular dichroism spectroscopy.

- Thermal Stability Assessment: Determine melting temperature (Tm) using differential scanning calorimetry or CD thermal denaturation.

- Functional Assays: Perform activity tests specific to design objective (e.g., enzymatic activity, binding affinity).

- High-Resolution Structure Determination: For selected designs, determine atomic-resolution structure using X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM.

Troubleshooting:

- If expression fails, consider codon optimization or alternative expression systems.

- If proteins are insoluble, test solubility tags or refolding protocols.

- If thermal stability is low, consider computational redesign or consensus stabilization.

Visualization of Workflows

AI-Driven Protein Design and Validation

T7-ORACLE Continuous Evolution System

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Universe Exploration

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| T7-ORACLE System | Continuous evolution platform | 100,000x higher mutation rate; orthogonal replication; leaves host genome untouched [30] | Rapid evolution of enzymes, antibodies, drug targets [30] |

| AlphaFold/ESMFold | Protein structure prediction | AI-driven; high accuracy; enables structure validation without experimental determination [26] | Validation of de novo designs; fold classification; function prediction [26] |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Physics-based protein design | Energy minimization; fragment assembly; flexible backbone design [26] | De novo fold design; enzyme active site engineering; interface design [26] |

| Generative AI Models (RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN) | Sequence and structure generation | Learns from natural protein space; generates novel sequences with desired properties [26] [28] | Creating proteins with customized folds and functions [26] |

| OrthoRep System | Yeast-based continuous evolution | Orthogonal DNA polymerase; in vivo mutagenesis; eukaryotic context [30] | Evolution of eukaryotic proteins; pathway engineering [30] |

| PFAM Database | Protein family classification | >10,000 protein families; domains of unknown function (DUFs) identification [27] | Target selection; functional annotation; evolutionary analysis [27] |

| BI-891065 | BI-891065|IAP Antagonist|For Research Use | BI-891065 is a potent small molecule IAP antagonist for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only, not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| CPR005231 | CPR005231 | Bench Chemicals |

The exploration of the vast protein functional universe represents one of the most promising frontiers in biotechnology and medicine. By combining AI-driven computational design with advanced continuous evolution systems like T7-ORACLE, researchers can now access regions of protein space that natural evolution has not sampled [26] [30]. This synergistic approach—merging rational design with accelerated evolution—provides a powerful framework for discovering novel biomolecules with tailored functionalities.

For EASME researchers, the integration of evolutionary algorithms with these cutting-edge technologies offers unprecedented opportunities to solve the inverse protein folding problem and design proteins with customized properties [29]. As these methodologies continue to mature, they promise to unlock new therapeutic, catalytic, and synthetic biology applications, ultimately expanding the functional possibilities within protein engineering beyond natural evolutionary boundaries [26].

Next-Generation Workflows: Integrating EAs with AI and Automated Biofoundries

The field of computational protein design has long been characterized by two parallel approaches: evolutionary algorithms (EAs) that explore sequence space through mutation and selection, and physics-based methods that optimize sequences against energy functions. Within the broader thesis on Evolutionary Algorithms for Synthetic Molecular Engineering (EASME), a new paradigm is emerging: hybrid architectures that combine the robust search capabilities of evolutionary algorithms with the deep pattern recognition of protein language models (PLMs). These hybrid systems are revolutionizing our ability to design novel proteins with tailored functions for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Protein design is fundamentally an inverse problem—predicting amino acid sequences that will fold into a specific structure and perform a desired function [31] [32]. Traditional physics-based design methods face significant challenges, including the inaccuracy of force fields in balancing subtle atomic interactions and the exponential growth of sequence space with protein size [33] [34]. Evolutionary algorithms address these challenges through population-based stochastic search, while PLMs, trained on millions of natural protein sequences, capture evolutionary constraints and structural patterns implicitly [35] [36]. The fusion of these approaches creates systems where PLMs guide evolutionary search toward regions of sequence space enriched with functional, foldable proteins.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Components

Evolutionary Algorithms in Protein Design

Evolutionary algorithms bring several powerful capabilities to protein design. Their population-based nature maintains diversity in sequence exploration, preventing premature convergence to suboptimal solutions. Through iterative cycles of mutation, crossover, and selection, EAs can efficiently navigate the vast combinatorial space of protein sequences (which scales as 20^L for a protein of length L) [33] [34]. Monte Carlo searches represent a particularly important class of evolutionary approaches in protein design, enabling the exploration of sequence space while accepting or rejecting mutations based on scoring criteria [33].

In practice, evolutionary approaches for protein design implement a workflow that begins with initial sequence generation, proceeds through iterative mutation and evaluation, and culminates in the selection of optimized sequences. The EvoDesign algorithm exemplifies this approach, using Monte Carlo searches that start from random sequences updated by random residue mutations [33]. These methods can incorporate various constraints, including structural profiles, physicochemical properties, and functional requirements, making them exceptionally adaptable to diverse design challenges.

Protein Language Models and Their Encoded Knowledge

Protein language models represent a revolutionary advancement in computational biology. Inspired by the success of large language models in natural language processing, PLMs are trained on massive datasets of protein sequences (tens of millions to billions) using self-supervised learning objectives [35] [36]. Through this training process, they learn the "grammar" and "syntax" of proteins—the complex patterns and constraints that govern how amino acid sequences fold into functional structures.

These models, including ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling), ProtT5, and ProtGPT, develop rich internal representations that capture structural, functional, and evolutionary information about proteins [35] [37] [36]. Recent research has made significant progress in interpreting what these models learn. For instance, MIT researchers used sparse autoencoders to identify that specific neurons in PLMs activate for particular protein features, such as transmembrane transport functions or specific structural domains [38]. This interpretability is crucial for effectively integrating PLMs into evolutionary design frameworks.

Table 1: Key Protein Language Models and Their Applications in Hybrid Design Systems

| Model Name | Architecture | Training Data | Relevant Design Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 | Transformer | Millions of protein sequences | Structure prediction, fitness prediction, function annotation |

| ProtGPT | GPT-based decoder | ~50 million sequences | De novo protein sequence generation, stability optimization |

| ProLLaMA | LLaMA-adapted | Large-scale protein databases | Function-specific protein design, therapeutic protein engineering |

| ESM-1b | Transformer | UniRef50 | Function prediction, zero-shot mutation effect prediction |

The power of hybrid EA-AI systems lies in their synergistic combination of evolutionary search and deep learning. Three primary architectural patterns have emerged for this integration, each with distinct advantages for different protein design challenges.

PLM as Initial Sequence Generator: In this approach, PLMs such as ProtGPT generate diverse starting populations for evolutionary optimization. These initial sequences already possess native-like properties and structural compatibility, providing a superior starting point compared to random sequences [39]. The evolutionary algorithm then refines these sequences for specific design objectives.

PLM as Fitness Predictor: Here, PLMs serve as efficient surrogate fitness functions, evaluating sequence quality without expensive molecular dynamics simulations. Models like ESM can predict structural stability, functional specificity, and even expression properties, dramatically accelerating evolutionary search [38] [36].

Evolution-Guided PLM Fine-tuning: This bidirectional approach uses evolutionary search to identify promising regions of sequence space, which then inform the fine-tuning of PLMs on specific protein families or functions. The refined PLM subsequently guides further evolutionary exploration, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement [40].

Application Notes: Implementing Hybrid EA-PLM Systems

Protocol 1: EvoDesign-MLM for Stable Scaffold Design

The EvoDesign framework exemplifies the successful integration of evolutionary and profile-based approaches, which can be enhanced through modern PLMs [33] [34]. This protocol details the process for designing stable protein scaffolds using a hybrid methodology.

Step 1: Structural Profile Construction

- Identify structural analogs for the target scaffold using TM-align with a TM-score cutoff of 0.5 to define similarity [33]

- Construct a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) from the multiple sequence alignment of identified structural analogs

- The PSSM is calculated as M(p,a) = Σ[w(p,x) × B(a,x)], where w(p,x) is the frequency of amino acid x at position p, and B(a,x) is the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix [33]

Step 2: PLM-Guided Sequence Initialization

- Generate initial sequence population using ProtGPT2 with the target scaffold as constraint

- Sample 100-200 sequences with temperature parameter Ï„=0.8 to balance diversity and quality

- Encode sequences using ESM-2 embeddings for subsequent analysis

Step 3: Evolutionary Optimization Cycle

- Implement Monte Carlo search with mutation rate of 1-2 residues per position per 1000 steps

- Evaluate sequences using hybrid scoring: E = wâ‚Eevolution + wâ‚‚EPLM + w₃EFoldX

- Where Eevolution is the evolutionary profile score, EPLM is the PLM confidence score, and EFoldX is the physics-based energy [33]

- Employ adaptive weighting with initial weights wevolution=0.7, wPLM=0.2, wFoldX=0.1

Step 4: Selection and Validation

- Cluster final sequences using SPICKER algorithm with BLOSUM62-based distance metric [33]

- Select centroid sequences from largest clusters for in silico validation

- Predict structures using AlphaFold2 or ESMFold and evaluate with MolProbity

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hybrid Protein Design

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Hybrid EA-PLM Workflows |

|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | Rosetta3, OSPREY, EvoDesign, FoldX | Provide physics-based energy functions, rotamer libraries, and flexible backbone sampling for evaluation [31] [33] |

| PLM Suites | ESM-2, ProtT5, ProtGPT2, ProLLaMA | Generate native-like sequences, predict fitness, and provide embeddings for sequence evaluation [39] [36] |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2, ESMFold, I-TASSER | Validate foldability of designed sequences by predicting 3D structure from amino acid sequence [35] [34] |

| Experimental Validation | Circular Dichroism, NMR Spectroscopy | Confirm secondary structure formation and tertiary structure packing in solution [33] [34] |

Protocol 2: Function-Specific Design with PLM Fitness Prediction

This protocol focuses on designing proteins with enhanced or novel functions, such as enzyme activity or binding specificity, using PLMs as fitness predictors within an evolutionary framework.

Step 1: Functional Profile Construction

- Collect functional analogs from UniProt and CATH databases using sequence and structure similarity

- Annotate functional sites and catalytic residues from Catalytic Site Atlas and literature

- Extract functional motifs and build position-specific frequency matrix for constrained positions

Step 2: PLM Fine-tuning for Function

- Fine-tune ESM-2 model on protein family-specific data (≥1000 sequences)

- Use masked language modeling objective with 15% masking rate

- Add functional annotation tokens to sequence representation during fine-tuning

Step 3: Evolutionary Search with Adaptive Sampling

- Implement covariance matrix adaptation evolution strategy (CMA-ES)

- Use PLM confidence scores as primary fitness function with 80% weighting

- Incorporate functional constraints (e.g., catalytic triads, binding motifs) as hard constraints

- Apply structural stability evaluation every 10 generations using FoldX [33]

Step 4: Multi-state Design for Specificity

- For binding proteins, implement multistate design using CLEVER and CLASSY algorithms [31]

- Evaluate binding affinity with interface structural profiles from COTH dimer library [33]

- Optimize for specificity using negative design against non-target structures

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Rigorous evaluation is essential for assessing the performance of hybrid EA-PLM systems. The metrics in the table below provide a comprehensive framework for comparing different architectural implementations and their effectiveness across various design scenarios.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Hybrid EA-PLM Systems

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Efficiency | Sequences evaluated per hour, Convergence generations | EvoDesign: 10^6 sequences/hour on 8-core CPU [33]; PLM acceleration: 3-5x speedup [36] |

| Sequence Quality | Native-likeness (PLM confidence), Evolutionary plausibility | Hybrid designs achieve 85-92% native-like sequences vs. 60-70% for physics-only [33] [34] |

| Structural Accuracy | RMSD to target, TM-score, MolProbity score | Average 2.1Ã… RMSD to target in folding simulations [34] |

| Experimental Success | Solubility, Thermostability, Functional activity | 80% solubility vs. 40-50% for physics-based; 60% well-ordered tertiary structure [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Implementation Framework

Computational Infrastructure Requirements

Implementing hybrid EA-PLM systems requires careful consideration of computational resources. For moderate-scale designs (proteins up to 300 residues), a high-performance workstation with GPU acceleration (NVIDIA RTX A6000 or equivalent) typically suffices. Large-scale designs or extensive sampling benefit from cluster computing with multiple GPUs. Memory requirements range from 16GB for basic implementations to 64GB+ for large PLMs with extensive context windows.

Software dependencies include Python 3.8+, PyTorch or TensorFlow for PLM inference, and specialized protein design software such as Rosetta or FoldX for physics-based scoring [31] [33]. The HuggingFace Transformers library provides standardized access to pre-trained PLMs, significantly reducing implementation overhead [39].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of hybrid architectures requires attention to several practical considerations. Balancing the weights between evolutionary, PLM, and physics-based scoring terms needs empirical adjustment for different protein classes and design objectives. For globular proteins, evolutionary terms often dominate, while for interface design, physics-based terms may require higher weighting [33].