Evolutionary Algorithms in Protein Function Prediction: A Practical Guide to Validation and Application in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) with computational methods for validating protein function predictions, a critical task for researchers and drug development professionals.

Evolutionary Algorithms in Protein Function Prediction: A Practical Guide to Validation and Application in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of evolutionary algorithms (EAs) with computational methods for validating protein function predictions, a critical task for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of EAs and the challenges of protein function annotation, establishing a clear need for robust validation frameworks. The content details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including structure-based and sequence-based validation strategies, and examines specific EA implementations like REvoLd and PhiGnet for docking and function annotation. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization techniques to enhance algorithm performance and reliability. Finally, the article presents a comparative analysis of validation metrics and real-world success stories, synthesizing key takeaways and outlining future directions for applying these advanced computational techniques in biomedical and clinical research to accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Protein Function Challenge and the Evolutionary Algorithm Solution

The rapid advancement of sequencing technologies has unveiled a profound challenge in modern biology: the existence of millions of uncharacterized proteins that constitute the "functional dark matter" of the proteomic universe. In the well-studied human gut microbiome alone, up to 70% of proteins remain uncharacterized [1]. This knowledge gap represents a critical bottleneck in understanding cellular mechanisms, disease pathways, and developing novel therapeutic interventions.

The exponential growth of protein sequence databases has dramatically outpaced experimental validation capabilities. While traditional experimental methods for functional characterization provide gold-standard annotations, they are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and expensive processes that cannot approach the scale of thousands of new protein families discovered annually [1] [2]. This disparity has stimulated the development of sophisticated computational methods, particularly those leveraging evolutionary algorithms and multi-objective optimization frameworks, to systematically navigate this vast landscape of uncharacterized proteins.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of Uncharacterized Proteins Across Biological Systems

| Biological System | Total Proteins | Uncharacterized Proteins | Percentage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut Microbiome | 582,744 protein families | 499,464 families | 85.7% | [1] |

| Escherichia coli Pangenome | Not specified | Not specified | 62.4% without BP terms | [1] |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 2,046 proteins | 398 proteins | 19.5% | [3] |

| Human Proteome | 20,239 protein-coding genes | ~2,000 proteins | ~10% | [2] |

Computational Framework: Evolutionary Algorithms and Multi-Omics Integration

The Evolutionary Algorithm Paradigm

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) have emerged as powerful tools for protein function prediction, particularly when formulated as multi-objective optimization (MOO) problems. These approaches effectively navigate the complex landscape of protein function space by simultaneously optimizing multiple, often conflicting objectives based on topological and biological data [4]. One innovative implementation recasts protein complex identification as an MOO problem that integrates gene ontology-based mutation operators with functional similarity metrics to enhance detection accuracy in protein-protein interaction networks [4].

The fundamental principle guiding many function prediction methods is "guilt-by-association" (GBA), which posits that proteins with unknown functions are likely involved in biochemical processes through their associations with characterized proteins [2]. This paradigm leverages the biological reality that interacting proteins or co-expressed genes often share functional similarities and can be associated with related diseases or phenotypes [4].

Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches

Cutting-edge methodologies now integrate diverse data types to overcome the limitations of single-evidence approaches. The FUGAsseM framework exemplifies this integration by employing a two-layered random forest classifier system that incorporates sequence similarity, genomic proximity, domain-domain interactions, and community-wide metatranscriptomic coexpression patterns [1]. This multi-evidence approach achieves accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art single-organism methods while providing dramatically greater coverage of diverse microbial community proteins.

Table 2: Computational Methods for Protein Function Prediction

| Method | Approach | Data Types Utilized | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FUGAsseM | Two-layer random forest | Metatranscriptomics, genomic context, sequence similarity | Microbial community focus; >443,000 protein families annotated | [1] |

| DPFunc | Deep learning with domain-guided structure | Protein structures, domain information, sequences | Detects key functional regions; outperforms structure-based methods | [5] |

| GOBeacon | Ensemble model with contrastive learning | Protein language models, PPI networks, structure embeddings | Integrates multiple modalities; superior CAFA3 performance | [6] |

| AnnoPRO | Hybrid deep learning dual-path encoding | Multi-scale protein representation | Addresses long-tail problem in GO annotation | [7] |

| PLASMA | Optimal transport for substructure alignment | Residue-level embeddings, structural motifs | Interpretable residue-level alignment | [8] |

| EA with FS-PTO | Multi-objective evolutionary algorithm | PPI networks, gene ontology | GO-based mutation operator for complex detection | [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Integrated Multi-Evidence Function Prediction for Microbial Communities

Application: Predicting functions of uncharacterized proteins from metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data.

Workflow:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Assemble protein families from metagenomic data using tools like MetaWIBELE [1].

- Collect matched metatranscriptomes from the same biological samples.

- Annotate proteins with known functions using UniProtKB and Gene Ontology databases.

Evidence Matrix Construction:

- Calculate sequence similarity using BLAST or Diamond against reference databases [3].

- Determine genomic proximity using operon prediction and gene cluster analysis.

- Identify domain-domain interactions using InterProScan and HMMER [3] [9].

- Quantify coexpression patterns from metatranscriptomic data using correlation metrics.

Two-Layer Random Forest Classification:

- First Layer: Train individual RF classifiers for each evidence type to assign unannotated proteins to functions based on associations with annotated proteins.

- Second Layer: Ensemble RF classifier integrates per-evidence prediction confidence scores to produce combined confidence scores, adjusting evidence weighting per function.

Validation and Benchmarking:

- Use cross-validation against known annotations.

- Compare performance against state-of-the-art methods like DeepGOPlus and DeepFRI.

- Experimental validation through targeted assays for high-priority predictions.

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Algorithm for Protein Complex Detection with Gene Ontology Integration

Application: Detecting protein complexes in PPI networks using multi-objective evolutionary algorithms.

Workflow:

- Network Preprocessing:

- Obtain PPI network from STRING database or experimental data.

- Annotate proteins with GO terms and calculate functional similarity.

- Filter low-confidence interactions using topological measures.

Multi-Objective Optimization Formulation:

- Define objectives: Modularity (Q), Internal Density (ID), Functional Similarity (FS).

- Initialize population of candidate solutions (protein complexes).

Gene Ontology-Based Mutation:

- Implement Functional Similarity-Based Protein Translocation Operator (FS-PTO).

- Select proteins for mutation based on functional similarity to complex members.

- Transfer proteins between complexes to improve functional coherence.

Evolutionary Algorithm Execution:

- Apply selection, crossover, and mutation operations for multiple generations.

- Use non-dominated sorting to maintain Pareto-optimal solutions.

- Employ diversity preservation mechanisms.

Complex Validation:

- Compare detected complexes with reference datasets (e.g., MIPS).

- Evaluate biological relevance using enrichment analysis.

- Assess robustness through noise introduction tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Protein Function Annotation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRINGS Database | Database | Protein-protein interactions | Functional association networks; complex detection [4] |

| InterProScan | Software | Domain and motif identification | Detecting conserved domains in uncharacterized proteins [3] [9] |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Ontology | Functional terminology standardization | Consistent annotation across proteins; enrichment analysis [2] |

| ESM-2/ProstT5 | Protein Language Model | Sequence and structure embeddings | Feature generation for machine learning approaches [6] |

| AlphaFold2/ESMFold | Structure Prediction | 3D protein structure from sequence | Structure-based function inference [5] [8] |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Ligand-protein interaction modeling | Binding site analysis for functional insight [9] |

| PyMOL | Visualization | 3D structure visualization | Analysis of functional motifs and active sites [9] |

| TMHMM | Prediction Tool | Transmembrane helix identification | Subcellular localization; membrane protein characterization [3] |

| SignalP | Prediction Tool | Signal peptide detection | Protein localization; secretory pathway analysis [3] |

Validation Framework: From Computational Predictions to Biological Significance

Robust validation of computational predictions remains essential for bridging the annotation gap. The following framework integrates computational and experimental approaches:

Computational Validation Metrics

- ROC Analysis: Evaluate prediction accuracy, with area under curve (AUC) >0.90 considered high confidence [3].

- Cross-Validation: Temporal validation based on CAFA challenges, partitioning data by annotation date [5] [7].

- Comparative Benchmarking: Assess performance against state-of-the-art methods using Fmax and AUPR metrics [5] [6].

Experimental Validation Pathways

- Targeted Mutagenesis: Validate essential predicted functional residues through site-directed mutagenesis [5].

- Ligand Binding Assays: Test predicted molecular functions through biochemical assays [9].

- Protein-Protein Interaction Validation: Confirm predicted interactions using Y2H or co-immunoprecipitation [10] [4].

- Gene Expression Analysis: Verify coexpression patterns through qPCR or transcriptomics [1].

The integration of evolutionary algorithms with multi-scale biological data represents a paradigm shift in addressing the critical gap in protein annotation. As these computational methods continue to evolve, they offer a systematic pathway to navigate the millions of uncharacterized proteins, transforming our understanding of biological systems and accelerating drug discovery.

The future of protein function annotation lies in the development of increasingly sophisticated multi-objective optimization frameworks that can seamlessly integrate diverse data types while providing biologically interpretable results. As these tools become more accessible to the broader research community, we anticipate accelerated discovery of novel protein functions, therapeutic targets, and fundamental biological mechanisms that will reshape our understanding of cellular life.

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) are population-based metaheuristic optimization techniques inspired by the principles of natural evolution. They are particularly valuable for solving complex, non-linear problems in computational biology, many of which are classified as NP-hard [4]. In biological contexts such as protein function prediction and drug discovery, EAs effectively navigate vast, complex search spaces where traditional methods often fail. The core operations of selection, crossover, and mutation enable these algorithms to iteratively refine solutions, balancing the exploration of new regions with the exploitation of known promising areas [11]. This balanced approach is crucial for addressing real-world biological challenges, including predicting protein-protein interaction scores, detecting protein complexes, and optimizing ligand molecules for drug development, where they must handle noisy, high-dimensional data and generate biologically interpretable results [12].

Core Operational Principles and Biological Applications

The fundamental cycle of an evolutionary algorithm involves maintaining a population of candidate solutions that undergo selection based on fitness, crossover to recombine promising traits, and mutation to introduce novel variations. This process mirrors natural evolutionary pressure, driving the population toward increasingly optimal solutions over successive generations [13]. In biological applications, these principles are adapted to incorporate domain-specific knowledge, such as gene ontology annotations or protein sequence information, significantly enhancing their effectiveness and the biological relevance of their predictions [4] [14].

Selection Operator

The selection operator implements a form of simulated natural selection by favoring individuals with higher fitness scores, allowing them to pass their genetic material to the next generation.

- Fitness-Proportionate Selection: This approach assigns selection probabilities directly proportional to an individual's fitness. In protein complex detection, fitness is often a multi-objective function balancing topological metrics like internal density with biological metrics like functional similarity based on Gene Ontology [4].

- Rank-Based and Tournament Selection: These methods help prevent premature convergence by reducing the selection pressure from super-fit individuals early in the process. Advanced implementations, such as the Dynamic Factor-Gene Expression Programming (DF-GEP) algorithm, adaptively adjust selection strategies during evolution to maintain population diversity and improve global search capabilities [12].

Table 1: Selection Strategies in Biological EAs

| Strategy Type | Mechanism | Biological Application Example | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Objective Selection | Balances conflicting topological & biological fitness scores | Detecting protein complexes in PPI networks [4] | Identifies functionally coherent modules |

| Dynamic Factor Optimization | Adaptively adjusts selection pressure based on population state | Predicting PPI combined scores with DF-GEP [12] | Prevents premature convergence |

| Elitism | Guarantees retention of a subset of best performers | Ligand optimization in REvoLd [11] | Preserves known high-quality solutions |

Crossover Operator

The crossover operator recombines genetic information from parent solutions to produce novel offspring, exploiting promising traits discovered by the selection process.

- Multi-Point Crossover: This standard approach exchanges multiple sequence segments between two parents. In the REvoLd algorithm for drug discovery, crossover recombines molecular fragments from promising ligand molecules to explore new regions of the chemical space [11].

- Domain-Specific Crossover: Effective biological EAs often employ custom crossover mechanisms. For instance, when working with gene ontology annotations, crossover must ensure the production of valid, semantically meaningful offspring by respecting the hierarchical structure of biological knowledge [4].

Diagram 1: Crossover generates novel solutions.

Mutation Operator

The mutation operator introduces random perturbations to individuals, restoring lost genetic diversity and enabling the exploration of uncharted areas in the search space.

- Standard Mutation: Involves random alterations to an individual's representation. In DF-GEP for PPI score prediction, an adaptive mutation rate is used, dynamically adjusted based on population diversity and evolutionary progress [12].

- Domain-Informed Mutation: Specialized mutation strategies significantly enhance performance. The Functional Similarity-Based Protein Translocation Operator (FS-PTO) uses Gene Ontology semantic similarity to guide mutations, translocating proteins between complexes in a biologically meaningful way rather than relying on random changes [4].

Table 2: Mutation Operators in Biological EAs

| Operator Type | Perturbation Mechanism | Biological Rationale | Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Mutation | Dynamically adjusts mutation rate | Maintains diversity while converging [12] | DF-GEP [12] |

| Functional Similarity-Based (FS-PTO) | Translocates proteins based on GO similarity | Groups functionally related proteins [4] | MOEA for Complex Detection [4] |

| Low-Similarity Fragment Switch | Swaps fragments with dissimilar alternatives | Explores diverse chemical scaffolds [11] | REvoLd [11] |

Integrated Experimental Protocol for Protein Complex Detection

This protocol details the application of a Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) for identifying protein complexes in Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks, incorporating gene ontology (GO) for biological validation [4].

Diagram 2: Protein complex detection workflow.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Application in Protocol | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRING Database | PPI Network Data | Provides combined score data for network construction and validation [12] | https://string-db.org/ |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Functional Annotation Database | Provides biological terms for functional similarity calculation and FS-PTO mutation [4] | http://geneontology.org/ |

| Cytoscape Software | Network Analysis Tool | Used for PPI network construction, visualization, and preliminary analysis [12] | https://cytoscape.org/ |

| Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences (MIPS) | Benchmark Complex Dataset | Serves as a gold standard for validating and benchmarking detected complexes [4] | http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/ |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation and Network Construction

- Source: Obtain PPI data from the STRING database, which provides a combined score indicating interaction confidence [12].

- Preprocessing: Filter interactions using a combined score threshold (e.g., >0.7) to reduce noise. Download corresponding Gene Ontology annotations for all proteins in the network.

- Construction: Use Cytoscape or a custom script to construct an undirected graph where nodes represent proteins and weighted edges represent the combined interaction scores [12].

Algorithm Initialization

- Population Generation: Randomly generate an initial population of candidate protein complexes. Each candidate is a subset of proteins in the network.

- Parameter Tuning: Set evolutionary parameters. Common settings are a population size of 100-200 individuals, a crossover rate of 0.8-0.9, and an initial mutation rate of 0.1, adaptable via dynamic factors [12].

Fitness Evaluation

- Evaluate each candidate complex using a multi-objective function that balances:

- Topological Fitness: Measured by Internal Density (ID). Formula: ID = 2E / (S(S-1)), where E is the number of edges within the complex and S is the complex size [4].

- Biological Fitness: Measured by the Functional Similarity (FS) of proteins within the complex, calculated from their GO annotations using semantic similarity measures [4].

- Evaluate each candidate complex using a multi-objective function that balances:

Evolutionary Cycle

- Selection: Apply a tournament or rank-based selection method to choose parents for reproduction, favoring candidates with higher Pareto dominance in the multi-objective space [4].

- Crossover: Recombine two parent complexes using a multi-point crossover to create offspring complexes.

- Mutation: Apply the FS-PTO operator. For a protein, identify the most functionally similar complex based on GO and translocate the protein there, rather than making a random change [4].

Termination and Output

- Loop: Repeat the fitness evaluation and evolutionary cycle for a fixed number of generations (e.g., 30-50) or until population convergence is observed.

- Output: Return the final population's non-dominated solutions as the set of predicted protein complexes. Validate against benchmark datasets like MIPS [4].

Advanced Application: Ultra-Large Library Screening with REvoLd

The REvoLd algorithm exemplifies a specialized EA for drug discovery, optimizing molecules within ultra-large "make-on-demand" combinatorial chemical libraries without exhaustive screening [11].

REvoLd Protocol for Ligand Optimization

- Initialization: Generate a random population of 200 ligands by combinatorially assembling available chemical building blocks [11].

- Fitness Evaluation: Dock each ligand against the target protein using RosettaLigand, which allows full ligand and receptor flexibility. The docking score serves as the fitness function [11].

- Selection: Allow the top 50 scoring ligands (elites) to advance to the next generation directly [11].

- Reproduction:

- Crossover: Perform multi-point crossover between fit molecules to recombine promising molecular scaffolds.

- Mutation: Implement multiple mutation strategies:

- Fragment Switch: Replace a molecular fragment with a low-similarity alternative to explore diverse chemistry.

- Reaction Switch: Change the core reaction used to assemble fragments, accessing different regions of the combinatorial library [11].

- Termination: Run for 30 generations. Execute multiple independent runs to discover diverse molecular scaffolds, as the algorithm does not fully converge but continues finding new hits [11].

The core principles of selection, crossover, and mutation provide a robust framework for tackling some of the most challenging problems in computational biology and drug discovery. By integrating domain-specific biological knowledge—such as Gene Ontology for mutation or flexible docking for fitness evaluation—these algorithms evolve from general-purpose optimizers into powerful tools for generating biologically valid and scientifically insightful results. The continued refinement of these mechanisms, particularly through dynamic adaptation and sophisticated biological knowledge integration, promises to further expand the capabilities of evolutionary computation in the life sciences.

Why EAs for Validation? Addressing Multi-Objective Optimization in Functional Annotation

The rapid expansion of protein sequence databases has far outpaced the capacity for experimental functional characterization, creating a critical annotation gap that computational methods must bridge [15] [6]. Protein function prediction is inherently a multi-objective optimization problem, requiring balance between often conflicting goals such as sequence similarity, structural conservation, interaction network properties, and phylogenetic patterns. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) provide a powerful framework for navigating these complex trade-offs during validation of functional annotations.

This application note establishes why EAs are particularly suited for addressing multi-objective challenges in functional annotation validation. We detail specific EA-based methodologies and provide standardized protocols for researchers to implement these approaches, with a focus on practical application for validating Gene Ontology (GO) term predictions.

EA Advantages for Multi-Objective Validation

Theoretical Foundations

Evolutionary Algorithms belong to the meta-heuristic class of optimization methods inspired by natural selection. Their population-based approach is fundamentally suited for multi-objective optimization as they can simultaneously handle multiple conflicting objectives and generate diverse solution sets in a single run [4] [16]. For protein function validation, where criteria such as sequence homology, structural compatibility, and network context often conflict, EAs can identify Pareto-optimal solutions that represent optimal trade-offs between these competing factors.

The multiple populations for multiple objectives (MPMO) framework exemplifies this strength, where separate sub-populations focus on distinct objectives while co-evolving to find comprehensive solutions [16]. This approach maintains population diversity while accelerating convergence—a critical advantage over methods that optimize objectives sequentially rather than simultaneously.

Specific Advantages for Protein Function Annotation

Table 1: EA Advantages for Protein Function Validation

| Advantage | Technical Basis | Validation Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Pareto Optimization | Identifies non-dominated solutions balancing multiple objectives without artificial weighting [4]. | Preserves nuanced functional evidence without premature simplification. |

| Biological Plausibility | Incorporates biological domain knowledge through custom operators (e.g., GO-based mutation) [4]. | Enhances functional relevance of validation outcomes. |

| Robustness to Noise | Maintains performance despite spurious or missing PPI data common in biological networks [4]. | Provides reliable validation despite imperfect input data. |

| Diverse Solution Sets | Population approach generates multiple validated annotation hypotheses [16]. | Supports exploratory analysis and ranking of alternative functions. |

EA-Based Validation Framework & Protocol

Integrated Multi-Objective EA Framework for Validation

The following workflow diagrams the complete EA-based validation process for protein function predictions, integrating both biological and topological objectives:

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Preparation of Validation Datasets

Materials Required:

- PPI Networks: Source from STRING, BioGRID, or species-specific databases

- GO Annotations: Current release from Gene Ontology Consortium

- Prediction Outputs: Results from tools like DeepGOPlus, GOBeacon, or custom predictors

- Sequence Embeddings: Pre-computed from ESM-2, ProtT5, or similar models [15] [6]

Procedure:

- Data Integration: Map predicted functions to known experimental annotations, creating gold-standard validation sets

- Feature Extraction: Generate multi-modal features (network topology, sequence embeddings, functional similarity)

- Objective Definition: Formulate 3-5 key validation objectives (e.g., topological density, GO consistency, phylogenetic profile correlation)

EA Configuration and Execution

Materials Required:

- Computational Environment: High-performance computing cluster with parallel processing capabilities

- Software Libraries: DEAP, Platypus, or custom EA frameworks in Python/R

Procedure:

- Population Initialization:

- Set population size to 100-500 individuals

- Encode solutions as binary vectors or real-valued representations

- Initialize with random solutions and known high-quality predictions

Fitness Evaluation (per generation):

- Calculate each objective function for all individuals

- Apply non-dominated sorting for Pareto ranking

- Compute crowding distance for diversity preservation

Genetic Operations:

- Selection: Apply tournament selection (size 2-3) to choose parents

- Crossover: Implement FS-PTO operator with 80-90% probability [4]

- Mutation: Apply GO-informed mutation with 5-15% probability per gene

Termination Check:

- Run for 100-500 generations or until Pareto front stabilizes

- Assess convergence by hypervolume improvement (<1% change over 10 generations)

Key EA Components for Functional Annotation

Multi-Objective Fitness Functions

Effective validation requires balancing multiple biological objectives. The following functions should be implemented:

Topological Objective:

Where |E(C)| is internal edges and |C| is complex size [4]

Biological Coherence Objective:

Where sim_GO is functional similarity based on GO term semantic similarity

Validation Accuracy Objective:

Using Matthews Correlation Coefficient for robust performance assessment [17] [18]

Specialized Genetic Operators

Functional Similarity-Based Protein Translocation Operator (FS-PTO)

This biologically-informed crossover operator enhances validation quality by considering functional relationships:

GO-Based Mutation Operator

This domain-specific mutation strategy introduces biologically plausible variations:

Procedure:

- For each candidate solution selected for mutation:

- Identify proteins with inconsistent functional annotations

- Query GO database for proteins with similar functional profiles

- Substitute inconsistent proteins with functionally similar alternatives

- Maintain topological constraints while improving biological coherence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function in EA Validation | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PPI Networks (STRING/BioGRID) | Provides topological framework for complex validation | Use high-confidence interactions (combined score >700) [4] |

| GO Semantic Similarity Measures | Quantifies functional coherence between proteins | Implement Resnik or Wang similarity metrics [4] |

| Protein Language Models (ESM-2, ProtT5) | Generates sequence embeddings for functional inference | Use pre-trained models; fine-tune if domain-specific [15] [6] |

| EA Frameworks (DEAP, Platypus) | Provides multi-objective optimization infrastructure | Configure for parallel fitness evaluation [4] [16] |

| Validation Metrics (MCC, F_max) | Quantifies prediction validation quality | Prefer MCC over F1 for imbalanced datasets [17] [18] |

Performance Assessment and Benchmarking

Quantitative Evaluation Protocol

Materials Required:

- Gold standard datasets (e.g., MIPS, CYC2008, GOA)

- Benchmark prediction sets from multiple methods

- Statistical analysis environment (R, Python with scipy/statsmodels)

Procedure:

- Comparative Analysis:

- Execute EA validation alongside alternative methods (MCL, MCODE, DECAFF)

- Apply identical evaluation metrics across all methods

- Perform statistical significance testing (paired t-tests, bootstrap confidence intervals)

- Robustness Testing:

- Introduce controlled noise into PPI networks (10-30% edge perturbation)

- Measure performance degradation across methods

- Assess stability of validated functional annotations

Expected Results and Interpretation

Table 3: Benchmarking EA Validation Performance

| Evaluation Metric | EA-Based Validation | Traditional Methods | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | 0.75 ± 0.08 | 0.62 ± 0.12 | p < 0.01 |

| F_max (Molecular Function) | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | p < 0.05 |

| Robustness to 20% PPI Noise | -8% performance | -22% performance | p < 0.001 |

| Functional Coherence (GO Similarity) | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.11 | p < 0.01 |

Interpretation Guidelines:

- EA validation typically outperforms on biological coherence metrics

- Traditional methods may excel in pure topological measures but lack functional relevance

- MCC values >0.7 indicate high-quality validation across all confusion matrix categories [17] [18]

- Robustness advantage emerges most clearly in noisy biological data conditions

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Implementation Challenges

Premature Convergence:

- Symptom: Population diversity loss within 20-30 generations

- Solution: Increase mutation rate (10-15%), implement niche preservation techniques

Poor Solution Quality:

- Symptom: Validated annotations lack biological coherence

- Solution: Enhance FS-PTO operator with additional biological constraints

Computational Intensity:

- Symptom: Fitness evaluation dominates runtime

- Solution: Implement parallel fitness evaluation, caching of GO similarity scores

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

Optimal parameter ranges established through empirical testing:

- Population Size: 150-300 individuals

- Crossover Rate: 0.8-0.9

- Mutation Rate: 0.05-0.15 per individual

- Generation Count: 200-500 iterations

Systematic parameter tuning should be performed for novel validation scenarios, with focus on balancing exploration and exploitation throughout the evolutionary process.

The accurate prediction of protein function represents a critical bottleneck in modern biology and drug discovery. While deep learning (DL) and protein language models (PLMs) have made significant strides by leveraging large-scale sequence and structural data, they often face challenges such as hyperparameter optimization, convergence on local minima, and handling the complex, multi-objective nature of biological systems [19] [20]. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) offer a powerful, biologically-inspired approach to address these limitations. This application note delineates protocols for integrating EAs with DL and PLMs to enhance the accuracy, robustness, and biological interpretability of protein function predictions, providing a practical framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Integrated Approaches

The integration of evolutionary algorithms with deep learning models has demonstrated measurable improvements in key performance metrics for computational biology tasks, from image classification to hyperparameter optimization.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of EA-Hybrid Models in Biological Applications

| Model/Algorithm | Application Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| HGAO-Optimized DenseNet-121 [20] | Multi-domain Image Classification | Accuracy: Up to +0.5% on test set; Loss: Reduced by 54 points | Outperformed HLOA, ESOA, PSO, and WOA |

| GOBeacon [6] | Protein Function Prediction (Fmax) | BP: 0.561, MF: 0.583, CC: 0.651 | Surpassed DeepGOPlus, Domain-PFP, and DeepFRI on CAFA3 |

| PerturbSynX [21] | Drug Combination Synergy Prediction | RMSE: 5.483, PCC: 0.880, R²: 0.757 | Outperformed baseline models across multiple regression metrics |

Integrated Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Objective EA for Protein Complex Detection in PPI Networks

This protocol details the use of a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for identifying protein complexes within protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, integrating Gene Ontology (GO) to enhance biological relevance [4].

Step 1: Problem Formulation as Multi-Objective Optimization

- Input: A PPI network represented as a graph G(V, E), where V is the set of proteins and E is the set of interactions.

- Objective Functions: Formulate the detection of protein complexes C as a multi-objective problem aiming to simultaneously maximize:

- Topological Density (D): D(C) = (2 * |EC|) / (|C| * (|C| - 1)) where EC are interactions within complex C.

- Bological Coherence (B): B(C) = Avg(Functional SimilarityGO(vi, vj)) for all proteins vi, vj in C, calculated using GO semantic similarity measures.

Step 2: Algorithm Initialization and GO-Informed Mutation

- Population Initialization: Generate an initial population of candidate solutions (potential protein complexes) using a seed-and-grow method from highly connected nodes.

- Functional Similarity-Based Protein Translocation Operator (FS-PTO):

- For a selected candidate complex C, identify the protein vmin with the lowest average functional similarity to other members of C.

- From the network neighbors of C, identify a protein vexternal that has high GO-based functional similarity to the members of C.

- With a defined probability, translocate vmin out of C and incorporate vexternal into C.

Step 3: Evolutionary Optimization and Complex Selection

- Fitness Evaluation: Calculate the non-dominated Pareto front for the two objective functions (Density and Biological Coherence) across the population.

- Selection and Variation: Apply tournament selection based on Pareto dominance. Use standard crossover and the custom FS-PTO mutation operator to create offspring populations.

- Termination and Output: Iterate for a predefined number of generations (e.g., 1000) or until convergence. Output the final set of non-dominated candidate complexes from the Pareto front.

Protocol 2: EA-Driven Hyperparameter Optimization for Deep Learning Models

This protocol describes using a hybrid evolutionary algorithm (HGAO) to optimize hyperparameters of deep learning models like DenseNet-121, improving their performance in biological image classification and other pattern recognition tasks [20].

Step 1: Search Space and Algorithm Configuration

- Hyperparameter Search Space: Define the critical parameters to optimize. For DenseNet-121, this typically includes:

- Learning Rate: Log-uniform distribution between 1e-5 and 1e-2.

- Dropout Rate: Uniform distribution between 0.1 and 0.7.

- HGAO Algorithm Setup: Configure the hybrid algorithm, which combines:

- Quadratic Interpolation-based Horned Lizard Optimization Algorithm (QIHLOA), simulating crypsis and blood-squirting behaviors for exploration.

- Newton Interpolation-based Giant Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (NIGAO), simulating foraging behaviors for exploitation.

- Hyperparameter Search Space: Define the critical parameters to optimize. For DenseNet-121, this typically includes:

Step 2: Fitness Evaluation and Evolutionary Cycle

- Fitness Function: The core of the EA is the fitness function. For a given hyperparameter set θ, it is evaluated as follows:

- Train the target DL model (e.g., DenseNet-121) on the training dataset using θ.

- Evaluate the trained model on a held-out validation set.

- The fitness score is the primary metric of interest, e.g., Fitness(θ) = Validation Accuracy.

- Hybrid Optimization: The HGAO algorithm evolves a population of hyperparameter sets over generations. It uses QIHLOA for global search to escape local optima and NIGAO for local refinement around promising solutions.

- Fitness Function: The core of the EA is the fitness function. For a given hyperparameter set θ, it is evaluated as follows:

Step 3: Model Deployment and Validation

- Final Model Training: Once the HGAO algorithm converges, select the hyperparameter set with the highest fitness score. Train the final model on the combined training and validation dataset using these optimized parameters.

- Performance Reporting: Evaluate the final model on a completely unseen test set, reporting standard metrics (e.g., Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score) to confirm the improvement gained from optimization.

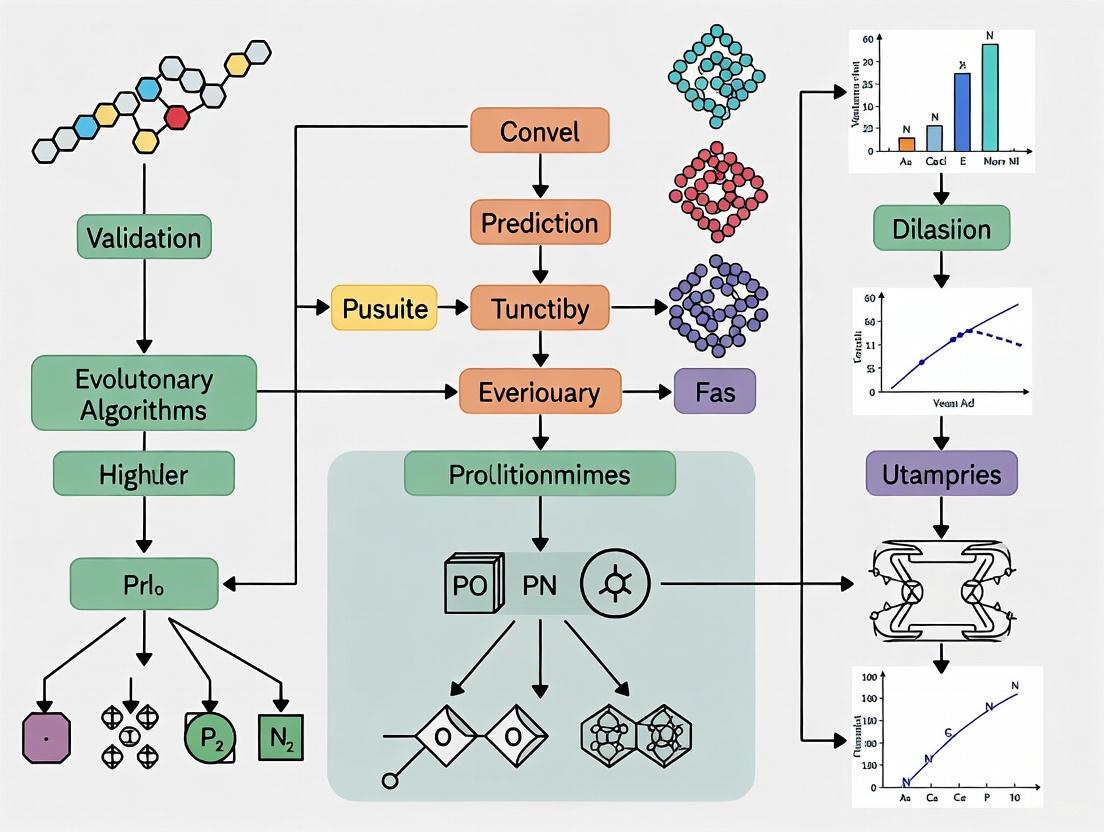

Workflow Visualization

Integrated EA-DL Framework for Functional Prediction

GO-Informed Mutation Operator (FS-PTO) Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for EA-DL Integration

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRING Database [22] [6] | PPI Network Data | Provides protein-protein interaction networks for constructing biological graphs for models like GOBeacon and MultiSyn. | https://string-db.org/ |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [4] [5] | Knowledge Base | Provides standardized functional terms for evaluating biological coherence in EAs and training DL models. | http://geneontology.org/ |

| ESM-2 & ProstT5 [6] | Protein Language Model | Generates sequence-based (ESM-2) and structure-aware (ProstT5) embeddings for protein representations. | GitHub / Hugging Face |

| InterProScan [5] | Domain Detection Tool | Scans protein sequences to identify functional domains, used for guidance in models like DPFunc. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/ |

| FS-PTO Operator [4] | Evolutionary Mutation Operator | Enhances complex detection in PPI networks by translocating proteins based on GO functional similarity. | Custom Implementation |

| HGAO Optimizer [20] | Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm | Optimizes hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate) of DL models like DenseNet-121 for improved performance. | Custom Implementation |

Implementing Evolutionary Algorithms for Robust Function Validation

The advent of ultra-large, make-on-demand chemical libraries, containing billions of readily available compounds, presents a transformative opportunity for in-silico drug discovery [11]. However, this opportunity is coupled with a significant challenge: the computational intractability of exhaustively screening these vast libraries using flexible docking methods that account for essential ligand and receptor flexibility [11] [23]. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) offer a powerful solution to this problem by efficiently navigating combinatorial chemical spaces without the need for full enumeration [24] [11]. RosettaEvolutionaryLigand (REvoLd) is an EA implementation within the Rosetta software suite specifically designed for this task [24]. It leverages the full flexible docking capabilities of RosettaLigand to optimize ligands from combinatorial libraries, such as Enamine REAL, achieving remarkable enrichments in hit rates compared to random screening [11]. This protocol details the application of REvoLd for structure-based validation of protein function predictions, enabling researchers to rapidly identify promising small-molecule binders for therapeutic targets or functional probes.

The REvoLd algorithm is an evolutionary process that optimizes a population of ligand individuals over multiple generations. Its core components are visualized in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: The REvoLd evolutionary docking workflow. The process begins with a random population of ligands, which are iteratively improved through cycles of docking, scoring, selection, and genetic operations.

Algorithm Description

REvoLd begins by initializing a population of ligands (default size: 200) randomly sampled from a combinatorial library definition [24] [11]. Each ligand in the population is then independently docked into the specified binding site of the target protein using the RosettaLigand protocol. The docking process incorporates full ligand flexibility and limited receptor flexibility, primarily through side-chain repacking and, optionally, backbone movements [23]. Each protein-ligand complex undergoes multiple independent docking runs (default: 150), and the resulting poses are scored.

The key innovation of REvoLd lies in its fitness function, which is based on Rosetta's full-atom energy function but is normalized for ligand size to favor efficient binders [24]. The primary fitness scores are:

- ligandinterfacedelta (lid): The difference in energy between the bound and unbound states.

- lid_root2: The

lidscore divided by the square root of the number of non-hydrogen atoms in the ligand. This is the default main term used for selection.

After scoring, the population undergoes selection pressure. The fittest individuals (default: 50 ligands) are selected to propagate to the next generation using a tournament selection process [24] [11]. This selective pressure drives the population towards better binders over time.

To explore the chemical space, REvoLd applies evolutionary operators to create new offspring:

- Crossover: Combines fragments from two parent ligands to create a novel child ligand.

- Mutation: Switches a single fragment in a ligand with an alternative from the library, or changes the reaction scheme used to link fragments.

This cycle of docking, scoring, selection, and reproduction is repeated for a fixed number of generations (default: 30). The algorithm is designed to be run multiple times (10-20 independent runs recommended) from different random seeds to broadly sample diverse chemical scaffolds [24].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful execution of a REvoLd screen requires the assembly of specific input files and computational resources. The following table summarizes the essential components of the "scientist's toolkit" for these experiments.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for REvoLd

| Item | Description | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein Structure | A prepared protein structure file (PDB format). The structure should be pre-processed (e.g., adding hydrogens, optimizing side-chains) using Rosetta utilities. | Serves as the static receptor for docking simulations. The binding site must be defined. |

| Combinatorial Library Definition | Two white-space separated files: 1. Reactions file: Defines the chemical reactions (via SMARTS strings) used to link fragments. 2. Reagents file: Lists the available chemical building blocks (fragments/synthons) with their SMILES, unique IDs, and compatible reactions. | Defines the vast chemical space from which REvoLd can assemble and sample novel ligands. |

| RosettaScripts XML File | An XML configuration file that defines the flexible docking protocol, including scoring functions and sampling parameters. | Controls the RosettaLigand docking process for each candidate ligand, ensuring consistent and accurate pose generation and scoring. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A computing environment with MPI support. Recommended: 50-60 CPUs per run and 200-300 GB of total RAM. | Provides the necessary computational power to execute the thousands of docking calculations required within a feasible timeframe (e.g., 24 hours/run). |

Benchmarking Performance and Experimental Data

REvoLd has been rigorously benchmarked on multiple drug targets, demonstrating its capability to achieve exceptional enrichment of hit-like molecules compared to random selection from ultra-large libraries [11].

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of REvoLd on Diverse Drug Targets

| Drug Target | Library Size Searched | Total Unique Ligands Docked by REvoLd | Hit Rate Enrichment Factor (vs. Random) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target 1 | >20 billion | ~49,000 - 76,000 | 869x |

| Target 2 | >20 billion | ~49,000 - 76,000 | 1,622x |

| Target 3 | >20 billion | ~49,000 - 76,000 | 1,201x |

| Target 4 | >20 billion | ~49,000 - 76,000 | 1,015x |

| Target 5 | >20 billion | ~49,000 - 76,000 | 1,450x |

Note: The number of docked ligands varies per target due to the stochastic nature of the algorithm. The enrichment factors highlight that REvoLd identifies potent binders by docking only a tiny fraction (e.g., 0.0003%) of the total library [11].

Fitness Score Convergence and Pose Accuracy

The convergence of a REvoLd run can be monitored by tracking the best fitness score (default: lid_root2) in each generation. Successful runs typically show a rapid improvement in scores within the first 15 generations, followed by a plateau as the population refines the best candidates [11]. Furthermore, the top-scoring poses output by REvoLd have been validated for accuracy. In cross-docking benchmarks, the enhanced RosettaLigand protocol consistently places the top-scoring ligand pose within 2.0 Å RMSD of the native crystal structure for a majority of cases, demonstrating its reliability in predicting correct binding modes [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Input Preparation

Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain a high-resolution structure of your target protein (e.g., from PDB or via homology modeling with AlphaFold2).

- Prepare the structure using Rosetta's

fixbbapplication or similar to repack side chains using the same scoring function planned for docking. This ensures the unbound state is optimized and scoring reflects binding affinity changes. - Remove any native ligands and crystallographic water molecules unless deemed critical.

Combinatorial Library Acquisition:

- The Enamine REAL space is the primary library used with REvoLd. Licensing for academic use can be obtained by contacting BioSolveIT or Enamine directly [24].

- The library is provided as two files:

reactions.txtandreagents.txt, which define the combinatorial chemistry rules.

RosettaScript Configuration:

- A default XML script for docking is provided in the REvoLd documentation. Key parameters to customize include:

box_sizein theTransformmover: Defines the search space for initial ligand placement.widthin theScoringGridmover: Sets the size of the scoring grid around the binding site.

- A default XML script for docking is provided in the REvoLd documentation. Key parameters to customize include:

Execution Command

A typical REvoLd run is executed using MPI for parallelization. The following command example outlines the required and key optional parameters.

Diagram 2: Structure of a REvoLd execution command. The model is built from a series of required and optional command-line flags that control input, parameters, and output.

Critical Note: Always launch independent REvoLd runs from separate working directories to prevent result files from being overwritten [24].

Output Analysis

Upon completion, REvoLd generates several key output files in the run directory:

ligands.tsv: The primary result file. It contains the scores and identifiers for every ligand docked during the optimization, sorted by the main fitness score. The numerical ID in this file corresponds to the PDB file name for the best pose of that ligand.*.pdbfiles: The best-scoring protein-ligand complex for thousands of the top ligands.population.tsv: A file for developer-level analysis of population dynamics, which can generally be ignored for standard applications.

REvoLd represents a significant advancement in structure-based virtual screening, directly addressing the scale of modern make-on-demand chemical libraries. By integrating an evolutionary algorithm with the rigorous, flexible docking framework of RosettaLigand, it enables the efficient discovery of high-affinity, synthetically accessible small molecules. The protocol outlined herein provides researchers with a detailed roadmap for deploying REvoLd to validate protein function predictions and accelerate early-stage drug discovery, turning the challenge of ultra-large library screening into a tractable and powerful opportunity.

The PhiGnet (Physics-informed graph network) method represents a significant advancement in the field of computational protein function prediction. It is a statistics-informed learning approach designed to annotate protein functions and identify functional sites at the residue level based solely on amino acid sequences [25] [26]. This method addresses a critical bottleneck in genomics: while over 356 million protein sequences are available in databases like UniProt, approximately 80% lack detailed functional annotations [26]. PhiGnet bridges this sequence-function gap by leveraging evolutionary information encapsulated in coevolving residues, providing a powerful tool for researchers in biomedicine and drug development who require accurate functional insights without relying on experimentally determined structures [25].

The foundational hypothesis of PhiGnet is that information contained in coevolving residues can be leveraged to annotate functions at the residue level. By capitalizing on knowledge derived from evolutionary data, PhiGnet employs a dual-channel architecture with stacked graph convolutional networks (GCNs) to process both evolutionary couplings and residue communities [25]. This allows it not only to assign functional annotations but also to quantify the significance of individual residues for specific biological functions, providing interpretable predictions that can guide experimental validation [26].

Methodological Framework and Key Concepts

Core Architectural Components

PhiGnet's architecture specializes in assigning functional annotations, including Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers and Gene Ontology (GO) terms, to protein sequences through several integrated components [25]:

Input Representation: Protein sequences are initially embedded using the pre-trained ESM-1b model, which converts amino acid sequences into numerical representations suitable for computational processing [25].

Dual-Channel Graph Convolutional Networks: The core of PhiGnet consists of two stacked graph convolutional networks that process two types of evolutionary constraints:

Information Processing Pipeline: The embedded sequence representations are input as graph nodes, with EVCs and RCs forming graph edges into six graph convolutional layers within the dual stacked GCNs. These work in conjunction with two fully connected layers to generate probability tensors for assessing functional annotation viability [25].

Activation Scoring: Using gradient-weighted class activation maps (Grad-CAM), PhiGnet computes activation scores to assess the significance of each individual residue for specific functions, enabling pinpoint identification of functional sites at the residue level [25].

Theoretical Foundation: Evolutionary Couplings and Residue Communities

The effectiveness of PhiGnet rests upon the biological significance of its core analytical components:

Evolutionary Couplings (EVCs) represent pairs of residue positions where mutations have co-occurred throughout evolution, maintaining functional or structural complementarity. These couplings are identified through statistical analysis of multiple sequence alignments and reflect constraints that preserve protein function across species [27]. The underlying principle is that when two residues interact directly, a mutation at one position must be compensated by a complementary mutation at the interacting position to maintain functional integrity [27].

Residue Communities (RCs) are groups of residues that exhibit coordinated evolutionary patterns and often correspond to functional units or structural domains within proteins. These communities represent hierarchical interactions beyond pairwise couplings and can identify functionally important regions even when residues are sparsely distributed across different structural elements [25]. For example, in the Serine-aspartate repeat-containing protein D (SdrD), residue communities identified through evolutionary couplings contained most residues that bind calcium ions, despite these residues being distributed across different structural elements [25].

Quantitative Performance Assessment

PhiGnet's performance has been rigorously evaluated against experimental data and compared with state-of-the-art methods. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from these assessments.

Table 1: PhiGnet Performance in Identifying Functional Residues

| Protein Target | Function Type | Prediction Accuracy | Key Correctly Identified Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| cPLA2α | Ion binding | High | Asp40, Asp43, Asp93, Ala94, Asn95 (Ca2+ binding) |

| Ribokinase | Ligand binding | Near-perfect | Not specified in source |

| αLA | Ion interaction | Near-perfect | Not specified in source |

| TmpK | Ligand binding | Near-perfect | Not specified in source |

| Ecl18kI | DNA binding | Near-perfect | Not specified in source |

| Average across 9 proteins | Various | ≥75% | Varies by protein |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Evolutionary Coupling-Based Methods

| Method | Input Data | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhiGnet | Sequence only | Residue-level function annotation; quantitative significance scoring | Requires sufficient homologous sequences |

| EvoIF/EvoIF-MSA [28] | Sequence + Structure | Lightweight architecture; integrates within-family and cross-family evolutionary information | Depends on quality of structural data |

| GREMLIN [27] | Sequence alignments | Accurate contact prediction across protein interfaces | Requires deep alignments (Nseq > Lprotein) |

| DCA-based Dynamics [29] | Sequence alignments | Predicts protein dynamics directly from sequences | Accuracy depends on contact prediction quality |

| IDBindT5 [30] | Single sequence | Predicts binding in disordered regions; fast processing | Lower accuracy for disordered regions |

The quantitative examinations demonstrate PhiGnet's capability to accurately identify functionally relevant residues across diverse proteins. In nine proteins of varying sizes (60-320 residues) and folds with different functions, PhiGnet achieved an average accuracy of ≥75% in predicting significant sites at the residue level compared to experimental or semi-manual annotations [25]. When mapped onto 3D structures, the activation scores showed significant enrichment for functional relevance at binding interfaces [25].

For example, for the mutual gliding-motility (MgIA) protein, residues with high activation scores (≥0.5) agreed with semi-manually curated BioLip database annotations and were located at the most conserved positions [25]. These residues formed a pocket that binds guanosine di-nucleotide (GDP), highlighting PhiGnet's ability to capture functionally important regions conserved through natural evolution [25].

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Implementing PhiGnet for Residue-Level Function Prediction

Objective: To predict protein function annotations and identify functionally significant residues using PhiGnet from amino acid sequences alone.

Input Requirements: Protein amino acid sequence in FASTA format.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sequence Embedding Generation

- Input the query protein sequence into the ESM-1b model to generate sequence embeddings.

- These embeddings serve as the initial representation of the protein, capturing sequence features that are informative for function prediction [25].

Evolutionary Data Extraction

- Evolutionary Couplings Calculation: Search sequence databases for homologs and build a multiple sequence alignment. Apply statistical methods (e.g., direct coupling analysis) to identify evolutionary couplings between residue pairs [25] [29].

- Residue Communities Identification: Perform community detection algorithms on the evolutionary coupling network to identify groups of residues with coordinated evolutionary patterns [25].

Graph Network Construction

- Represent the protein as a graph where:

- Nodes correspond to individual residues, initialized with their ESM-1b embeddings.

- Edges represent either evolutionary couplings (EVCs) or residue community relationships (RCs) [25].

- This creates two complementary graph representations of the same protein.

- Represent the protein as a graph where:

Dual-Channel Graph Convolution Processing

- Process each graph through a separate stack of six graph convolutional layers:

- Channel 1: Processes evolutionary couplings (EVCs) to capture direct coevolutionary constraints.

- Channel 2: Processes residue communities (RCs) to capture higher-order functional modules [25].

- Each GCN layer updates node representations by aggregating information from connected neighbors, progressively capturing more complex patterns.

- Process each graph through a separate stack of six graph convolutional layers:

Feature Integration and Function Prediction

- Combine the outputs from both GCN channels.

- Pass the integrated representations through two fully connected layers.

- Generate probability scores for different functional annotations (EC numbers, GO terms) [25].

Residue Significance Scoring

- Apply Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) to the trained model.

- Compute activation scores for each residue relative to specific predicted functions.

- Residues with high activation scores (≥0.5) are identified as potentially functionally significant [25].

Output Interpretation:

- The model outputs both protein-level function predictions and residue-level significance scores.

- High-scoring residues should be prioritized for experimental validation (e.g., site-directed mutagenesis).

- Predictions can be mapped onto experimental or predicted structures to visualize functional sites [25].

Validation Protocol: Experimental Verification of Predicted Functional Residues

Objective: To experimentally validate PhiGnet predictions of functionally important residues.

Procedure:

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

- Design mutant constructs targeting high-activation-score residues predicted by PhiGnet.

- Include control mutations of residues with low activation scores.

- Express and purify wild-type and mutant proteins [25].

Functional Assays

- For enzyme predictions: Measure catalytic activity of wild-type and mutants.

- For binding proteins: Determine binding affinity using methods like surface plasmon resonance or isothermal titration calorimetry.

- For structural proteins: Assess structural integrity via circular dichroism or stability assays [25].

Data Analysis

- Compare functional measurements between wild-type and mutants.

- Statistically significant loss of function in high-score mutants validates prediction accuracy.

- Control mutations should show minimal functional impact [25].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues in PhiGnet Implementation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low confidence predictions | Insufficient homologous sequences for EVC calculation | Expand sequence database search parameters |

| Poor residue-level resolution | Shallow multiple sequence alignments | Use more sensitive homology detection methods |

| Disagreement with known annotations | Species-specific functional adaptations | Incorporate phylogenetic context in analysis |

| Inconsistent community detection | Weak coevolutionary signal | Adjust community detection parameters |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete PhiGnet experimental workflow, from sequence input to functional prediction and validation:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Evolutionary Coupling Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-1b [25] | Protein Language Model | Generates sequence embeddings | Initial protein representation |

| HHblits/Jackhmmer | Homology Detection | Builds multiple sequence alignments | Evolutionary couplings calculation |

| GREMLIN [27] | Statistical Model | Identifies coevolving residues | EVC calculation from MSAs |

| ProtT5 [30] | Protein Language Model | Alternative sequence embeddings | Input representation option |

| Foldseek [28] | Structure Search Tool | Finds structural homologs | Homology detection via structure |

| AlphaFold2 [29] | Structure Prediction | Predicts 3D protein structures | Optional structural validation |

| BioLiP [25] | Database | Curated ligand-binding residues | Benchmarking predictions |

These computational tools form the essential toolkit for implementing PhiGnet and related evolutionary coupling analyses. The protein language models (ESM-1b, ProtT5) provide the initial sequence representations that capture evolutionary constraints learned from millions of natural sequences [25] [30]. Homology detection tools are critical for building multiple sequence alignments needed to calculate evolutionary couplings, with Foldseek offering the unique capability to find homologs through structural similarity when sequence similarity is low [28]. GREMLIN and similar global statistical models employ pseudo-likelihood maximization to distinguish direct from indirect couplings, which is essential for accurate contact prediction [27]. Finally, structure prediction tools and curated databases serve validation purposes, allowing researchers to compare predictions with experimental or computationally generated structures and known functional annotations [25] [29].

The rational design of therapeutic molecules, whether proteins or small molecules, inherently involves balancing multiple, often competing, biological and chemical properties. A candidate with exceptional binding affinity may prove useless due to high toxicity or poor synthesizability. Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) have emerged as powerful tools for navigating this complex multi-objective optimization landscape, capable of efficiently exploring vast molecular search spaces to identify Pareto-optimal solutions—those where no single objective can be improved without sacrificing another [31] [32]. Framing this challenge within a rigorous multi-objective optimization (MOO) or many-objective optimization (MaOO) context is crucial for accelerating the discovery of viable drug candidates. This Application Note details the integration of multi-objective fitness functions within evolutionary algorithms, providing validated protocols for simultaneously optimizing binding affinity, synthesizability, and toxicity, directly supporting the broader thesis of validating protein function predictions with evolutionary algorithm research.

Computational Frameworks for Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization

Several advanced computational frameworks have been developed to address the challenges of constrained multi-objective optimization in molecular science. These frameworks typically combine latent space representation learning with sophisticated evolutionary search strategies.

Table 1: Key Multi-Objective Optimization Frameworks in Drug Discovery

| Framework Name | Core Methodology | Handled Objectives (Examples) | Constraint Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| PepZOO [33] | Multi-objective zeroth-order optimization in a continuous latent space (VAE). | Antimicrobial function, activity, toxicity, binding affinity. | Implicitly handled via multi-objective formulation. |

| CMOMO [34] | Deep multi-objective EA with a two-stage dynamic constraint handling strategy. | Bioactivity, drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility. | Explicitly handles strict drug-like criteria as constraints. |

| MosPro [35] | Discrete sampling with Pareto-optimal gradient composition. | Binding affinity, stability, naturalness. | Pareto-optimality for balancing conflicting objectives. |

| MoGA-TA [31] | Improved genetic algorithm using Tanimoto crowding distance. | Target similarity, QED, logP, TPSA, rotatable bonds. | Maintains diversity to prevent premature convergence. |

| Transformer + MaOO [32] | Integrates latent Transformer models with many-objective metaheuristics. | Binding affinity, QED, logP, SAS, multiple ADMET properties. | Pareto-based approach for >3 objectives. |

The CMOMO framework is particularly notable for its explicit and dynamic handling of constraints, which is a critical advancement for practical drug discovery. It treats stringent drug-like criteria (e.g., forbidden substructures, ring size limits) as constraints rather than optimization objectives [34]. Its two-stage optimization process first identifies molecules with superior properties in an unconstrained scenario before refining the search to ensure strict adherence to all constraints, effectively balancing performance and practicality [34].

For problems involving more than three objectives, the shift to a many-objective optimization perspective is crucial. A framework integrating Transformer-based molecular generators with many-objective metaheuristics has demonstrated success in simultaneously optimizing up to eight objectives, including binding affinity and a suite of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties [32]. Among many-objective algorithms, the Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Dominance and Decomposition (MOEA/D) has been shown to be particularly effective in this domain [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Multi-Objective EA for Protein Optimization (PepZOO)

This protocol describes the directed evolution of a protein sequence using a latent space and zeroth-order optimization, adapted from the PepZOO methodology [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Encoder-Decoder Model (Variational Autoencoder): A pre-trained model to project discrete amino acid sequences into a continuous latent space and reconstruct sequences from latent vectors [33].

- Property Predictors: Independently trained supervised models for each property of interest (e.g., toxicity predictor, stability predictor). These do not need to be differentiable [33].

- Initial Population (Prototype AMPs): A set of known protein sequences (e.g., natural antimicrobial peptides) to serve as starting points for evolution [33].

Procedure

- Sequence Encoding: Encode each prototype amino acid sequence in the initial population into a low-dimensional, continuous latent vector,

z, using the encoder module [33]. - Property Evaluation: Decode the latent vector back to a sequence and use the property predictors to evaluate the multiple objectives (e.g.,

F_toxicity,F_affinity,F_synthesizability). - Gradient Estimation via Zeroth-Order Optimization:

- For the current latent vector

z, generate a population ofMrandom directional vectors{u_m}. - Create perturbed latent vectors

z' = z + σ * u_m, whereσis a small step size. - Decode and evaluate the properties for each perturbed vector.

- Estimate the gradient for each objective

ias:ĝ_i = (1/Mσ) * Σ_{m=1}^M [F_i(z + σu_m) - F_i(z)] * u_m.

- For the current latent vector

- Determine Evolutionary Direction: Compose the individual gradients

{ĝ_i}into a single update direction,Δz, that improves all objectives. This can be achieved by a weighted sum or a Pareto-optimal composition scheme [33] [35]. - Iterative Update: Update the latent representation:

z_{new} = z + η * Δz, whereηis the learning rate. Decodez_{new}to obtain the new candidate sequence. - Termination Check: Repeat steps 2-5 until the generated sequences meet all target property thresholds or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Figure 1: Workflow for multi-objective protein optimization using latent space and zeroth-order gradients, as implemented in PepZOO [33].

Protocol 2: Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization for Small Molecules (CMOMO)

This protocol is designed for optimizing small drug-like molecules under strict chemical constraints, based on the CMOMO framework [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Lead Molecule: The initial molecule to be optimized.

- Chemical Database (e.g., ChEMBL): A source of known bioactive molecules to build a "Bank library" for initialization.

- Pre-trained Chemical Encoder-Decoder: A model (e.g., based on SMILES or SELFIES) to map molecules to and from a continuous latent space.

- Property Predictors: Models for QED, synthesizability (SA), logP, etc.

- Constraint Validator: A function (e.g., using RDKit) to check molecular validity and drug-like constraints (e.g., ring size, forbidden substructures).

Procedure

- Population Initialization:

- Encode the lead molecule and top-K similar molecules from the Bank library into latent vectors.

- Generate an initial population of

Nlatent vectors by performing linear crossover between the lead molecule's vector and those from the library [34].

- Unconstrained Optimization Stage:

- Reproduction: Use a latent Vector Fragmentation-based Evolutionary Reproduction (VFER) strategy to generate offspring latent vectors, promoting diversity [34].

- Evaluation: Decode all parent and offspring vectors into molecules. Filter invalid molecules using RDKit. Evaluate the multiple objective properties (e.g., bioactivity, QED) for each valid molecule.

- Selection: Apply a multi-objective selection algorithm (e.g., non-dominated sorting) to select the best

Nmolecules based solely on their property scores, ignoring constraints for now.

- Constrained Optimization Stage:

- Feasibility Evaluation: Calculate the Constraint Violation (CV) for each molecule in the population using a function that aggregates violations of all predefined constraints [34].

- Constrained Selection: Switch to a selection strategy that prioritizes feasibility. Molecules with CV=0 (feasible) are preferred. Among feasible molecules, selection is based on non-dominated sorting of the property objectives.

- Termination: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until a population of molecules is found that is both feasible (CV=0) and Pareto-optimal with respect to the multiple property objectives.

Table 2: Example Quantitative Results from Multi-Objective Optimization Studies

| Study / Framework | Optimization Task | Key Results | Success Rate & Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| PepZOO [33] | Optimize antimicrobial function & activity. | Outperformed state-of-the-art methods (CVAE, HydrAMP). | Improved multi-properties (function, activity, toxicity). |

| CMOMO [34] | Inhibitor optimization for Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 (GSK3). | Identified molecules with favorable bioactivity, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility. | Two-fold improvement in success rate compared to baselines. |

| DeepDE [36] | GFP activity enhancement. | 74.3-fold increase in activity over 4 rounds of evolution. | Surpassed benchmark superfolder GFP. |

| MoGA-TA [31] | Six multi-objective benchmark tasks (e.g., Fexofenadine, Osimertinib). | Better performance in success rate and hypervolume vs. NSGA-II and GB-EPI. | Reliably generated molecules meeting all target conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Multi-Objective Evolutionary Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Projects discrete molecular sequences into a continuous latent space, enabling smooth optimization [33] [34]. | Creating a continuous search space for gradient-based evolutionary operators in PepZOO and CMOMO. |

| Transformer-based Autoencoder | Advanced sequence model for molecular generation; provides a structured latent space for optimization [32]. | Used in ReLSO model for generating novel molecules optimized for multiple properties. |

| RDKit Software Package | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit; used for fingerprint generation, similarity calculation, and molecular validity checks [31]. | Calculating Tanimoto similarity and physicochemical properties (logP, TPSA) in MoGA-TA. |

| Property Prediction Models | Supervised ML models that act as surrogates for expensive experimental assays during in silico optimization. | Predicting toxicity, binding affinity (docking), and ADMET properties to guide evolution [33] [32]. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) Annotations | Provides biological functional insights; can be integrated into mutation operators or fitness functions. | Used in FS-PTO mutation operator to improve detection of biologically relevant protein complexes [4]. |

| Non-dominated Sorting (NSGA-II) | A core selection algorithm in MOEAs that ranks solutions by Pareto dominance and maintains population diversity [31]. | Selecting the best candidate molecules for the next generation in MoGA-TA and other frameworks. |

Figure 2: Logical relationship between core components in a deep learning-guided multi-objective evolutionary algorithm.

The ability to predict protein function has opened new frontiers in identifying therapeutic targets. Validating these predictions, however, requires discovering ligands that modulate these functions. Ultra-large chemical libraries, containing billions of "make-on-demand" compounds, represent a golden opportunity for this task, but their vast size makes exhaustive computational screening prohibitively expensive. This application note details how the evolutionary algorithm REvoLd (RosettaEvolutionaryLigand) enables efficient hit identification within these massive chemical spaces, providing a critical tool for experimentally validating protein function predictions [11] [37].

REvoLd addresses the fundamental challenge of ultra-large library screening (ULLS): the computational intractability of flexibly docking billions of compounds. By exploiting the combinatorial nature of make-on-demand libraries, it navigates the search space intelligently rather than exhaustively, identifying promising hit molecules with several orders of magnitude fewer docking calculations than traditional virtual high-throughput screening (vHTS) [11] [38]. This case study outlines REvoLd's principles and presents a proven experimental protocol for its application, demonstrated through a successful real-world benchmark against the Parkinson's disease-associated target LRRK2.

REvoLd Algorithm and Key Concepts

Core Evolutionary Principles