Evolutionary Forecasting: The New Paradigm for Predictive Drug Discovery and Development

This article explores the emerging field of evolutionary forecasting, a powerful paradigm that applies principles of natural selection to predict and optimize complex biological processes.

Evolutionary Forecasting: The New Paradigm for Predictive Drug Discovery and Development

Abstract

This article explores the emerging field of evolutionary forecasting, a powerful paradigm that applies principles of natural selection to predict and optimize complex biological processes. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we dissect the foundational theory that frames drug discovery as an evolutionary process with high attrition rates. The scope extends to methodological applications of artificial intelligence and evolutionary algorithms in target identification, molecular design, and clinical trial optimization. We address critical challenges in predictive accuracy, including data limitations and stochasticity, and provide a comparative analysis of validation frameworks. By synthesizing insights from evolutionary biology and computational science, this article provides a comprehensive roadmap for leveraging predictive models to de-risk R&D pipelines, reduce development timelines, and enhance the success rates of new therapeutics.

The Evolutionary Framework: From Natural Selection to Drug Development Pipelines

The process of drug discovery mirrors the fundamental principles of natural selection, operating through a rigorous cycle of variation, selection, and amplification. In this evolutionary framework, thousands of candidate molecules constitute a diverse population that undergoes intense selective pressure at each development stage. High attrition rates reflect a stringent selection process where only candidates with optimal therapeutic properties survive to reach patients. Current data reveals that the likelihood of approval for a new Phase I drug has plummeted to just 6.7%, down from approximately 10% a decade ago [1] [2]. This selection process mirrors evolutionary fitness landscapes, where most variants fail while only the most adapted succeed.

The foundational analogy extends to nature's laboratory – the human genome represents billions of years of evolutionary experimentation through random genetic mutations and natural selection [3]. With nearly eight billion humans alive today, each carrying millions of genetic variants, virtually every mutation compatible with life exists somewhere in the global population. These natural genetic variations serve as a comprehensive catalog of experiments, revealing which protein modifications confer protective benefits or cause disease. This perspective transforms our approach to target validation, allowing researchers to learn from nature's extensive experimentation rather than relying solely on artificial models that often fail to translate to humans.

The Selection Landscape: Quantitative Analysis of Attrition Rates

Current Clinical Success Rates

Drug development faces an increasingly challenging selection environment. Analysis of phase transition data between 2014 and 2023 reveals declining success rates across all development phases [2].

Table 1: Clinical Trial Success Rates (2014-2023)

| Development Phase | Success Rate | Primary Attrition Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I | 47% | Safety, pharmacokinetics, metabolic stability |

| Phase II | 28% | Efficacy, toxicity, biological complexity |

| Phase III | 55% | Insufficient efficacy vs. standard care, safety in larger populations |

| Regulatory Submission | 92% | Manufacturing, final risk-benefit assessment |

| Overall (Phase I to Approval) | 6.7% | Cumulative effect of all above factors |

The most significant selection pressure occurs at the Phase II hurdle, where nearly three-quarters of candidates fail, representing the critical point where theoretical mechanisms face empirical testing in patient populations [2]. This increasingly stringent selection environment stems from two competing forces: the push into biologically complex diseases with high unmet need, and dramatic increases in funding, pipelines, and clinical trial activity that create crowded competitive landscapes [2].

Disease-Specific Selection Pressures

The selection landscape varies dramatically across therapeutic areas, with distinct fitness criteria for different disease contexts. Analysis of dynamic clinical trial success rates (ClinSR) reveals great variations among various diseases, developmental strategies, and drug modalities [4].

Table 2: Success Rate Variations by Therapeutic Area

| Therapeutic Area | Relative Success Rate | Key Selection Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Below Average | Tumor heterogeneity, drug resistance mechanisms |

| Central Nervous System | Below Average | Blood-brain barrier penetration, complex pathophysiology |

| Rare Diseases | Above Average | Defined genetic mechanisms, accelerated regulatory pathways |

| Anti-infectives | Variable (extremely low for COVID-19) | Rapid pathogen evolution, animal model translatability |

| Repurposed Drugs | Unexpectedly Lower (recent years) | Novel disease mechanisms, dosing re-optimization |

This variation in selection pressures across therapeutic areas demonstrates the concept of fitness landscapes in drug development, where the criteria for success depend heavily on the biological and clinical context [4].

Learning from Nature's Laboratory: Genetic Validation as a Selection Tool

The Protective Mutation Framework

Natural genetic variations provide powerful insights for drug target validation, serving as a curated library of human experiments. A 2015 study matching drugs with genes coding for the same protein targets found that drugs with supporting human genetic evidence had double the odds of regulatory approval, with a 2024 follow-up analysis showing an even higher 2.6-fold improvement [3]. This genetic validation approach represents a fundamental shift toward learning from nature's extensive experimentation.

Several notable examples demonstrate this principle:

- CCR5 Receptor and HIV Immunity: A natural mutation in the CCR5 protein receptor provides immunity to HIV without apparent health consequences, leading to the development of Maraviroc in 2007 [3].

- DGAT1 Inhibitors and Diarrheal Disorders: Pharmaceutical DGAT1 inhibitors failed clinical trials due to severe diarrhea and vomiting, later explained by the discovery of children with natural DGAT1 mutations suffering from identical symptoms [3].

- PCSK9 and Cholesterol Regulation: Variants in the PCSK9 gene were found to significantly lower LDL cholesterol, with discoveries made possible because these variants were more common in African populations [3].

Experimental Protocol: Genetic Target Validation

Objective: To systematically identify and validate drug targets using human genetic evidence from natural variations.

Methodology:

- Population Sequencing: Large-scale exome or genome sequencing of diverse populations (e.g., UK Biobank, Regeneron Genetics Center sequencing 100,000 people) [3]

- Phenotype Correlation: Link genetic variants to disease diagnoses, blood tests, and phenotypic data from nationwide registers and electronic health records

- Variant Filtering: Focus on protein-altering variants with significant protective associations against diseases

- Mechanistic Validation: Confirm biological mechanisms through in vitro and in vivo studies

Key Technical Considerations:

- Diversity Matters: Sample diverse populations to capture population-specific variants (e.g., PCSK9 variants more common in Africans) [3]

- Sample Size: Current initiatives target 500,000 participants to detect rare protective variants [3]

- Functional Follow-up: Use cellular models (e.g., hepatocytes for liver targets) to confirm functional consequences of identified variants

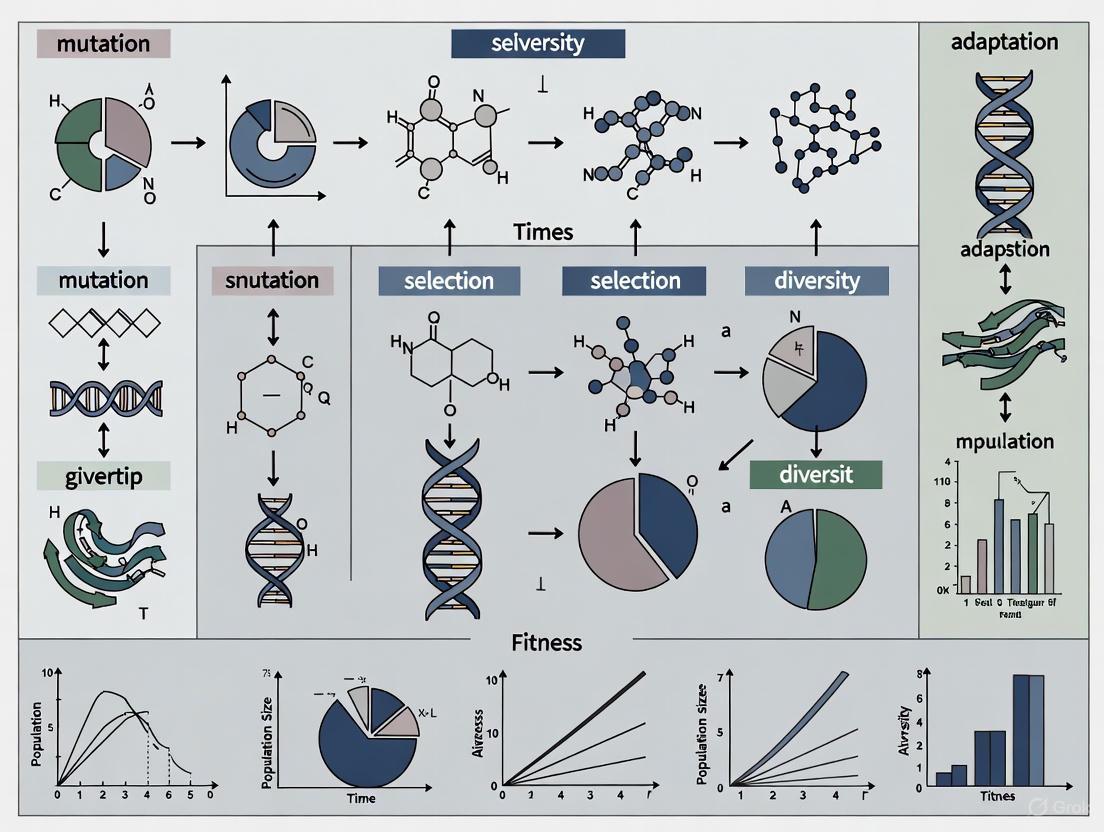

Diagram 1: Genetic target validation workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Validation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Genetic Validation

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing Platforms | Identify coding and non-coding variants | Population-scale sequencing (UK Biobank) [3] |

| Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Arrays | Detect common genetic variations | Initial screening for disease associations |

| Human Hepatocytes | Study liver-specific metabolism | Validation of HSD17B13 liver disease protection [3] |

| Primary Cell Cultures | Model human tissue-specific biology | CCR5 function in immune cells [3] |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) | Confirm target engagement in intact cells | Validation of direct drug-target binding [5] |

| Animal Disease Models | In vivo functional validation | DGAT1 knockout mouse model [3] |

Adaptive Strategies: Modern Approaches to Improve Evolutionary Fitness

AI-Driven Molecular Evolution

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative force in designing molecular candidates with enhanced fitness properties. Machine learning models now routinely inform target prediction, compound prioritization, pharmacokinetic property estimation, and virtual screening strategies [5]. Recent work demonstrates that integrating pharmacophoric features with protein-ligand interaction data can boost hit enrichment rates by more than 50-fold compared to traditional methods [5].

In hit-to-lead optimization, deep graph networks can generate thousands of virtual analogs, dramatically compressing traditional timelines. In one 2025 study, this approach generated 26,000+ virtual analogs, resulting in sub-nanomolar inhibitors with over 4,500-fold potency improvement over initial hits [5]. This represents a paradigm shift from sequential experimental cycles to parallel in silico evolution of molecular families.

Diagram 2: AI-driven drug discovery cycle

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro DMPK Selection Assays

Early assessment of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) properties represents a crucial selection hurdle that eliminates candidates with suboptimal "fitness" profiles before clinical testing. In vitro DMPK studies can prevent late-stage failures by identifying liabilities in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties [6].

Key Methodologies:

Metabolic Stability Assays

- Purpose: Evaluate metabolic rate and half-life

- Protocol: Incubate test compound with liver microsomes or hepatocytes (human/animal)

- Measurements: Parent compound depletion over time, metabolite identification

- Interpretation: High metabolic stability suggests longer half-life and sustained efficacy

Permeability Assays (Caco-2, PAMPA)

- Purpose: Assess ability to cross biological membranes

- Caco-2 Model: Human intestinal barrier model (cell-based)

- PAMPA: Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (non-cell-based)

- Application: Predict oral absorption and bioavailability

Plasma Protein Binding

- Purpose: Determine free fraction available for pharmacological activity

- Method: Equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration

- Significance: Only unbound drug is pharmacologically active

CYP450 Inhibition and Induction

- Purpose: Identify drug-drug interaction potential

- Assay Format: Fluorescent or LC-MS/MS based activity measurements

- Clinical Relevance: Inhibition increases toxicity risk, induction reduces efficacy

Transporter Assays

- Purpose: Evaluate uptake and efflux transporter interactions

- Key Transporters: P-glycoprotein (P-gp), OATPs

- Impact: Absorption, tissue distribution, excretion predictions

Technical Considerations:

- Use human-derived materials for better clinical translatability

- Employ LC-MS/MS for sensitive drug concentration measurements

- Integrate data with computational modeling to predict human pharmacokinetics

Novel Modalities Expanding the Druggable Genome

Evolution in drug discovery has expanded beyond small molecules to include novel modalities that address previously "undruggable" targets:

PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras): Over 80 PROTAC drugs are in development, leveraging the body's natural protein degradation system [7]. These molecules recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to target proteins for destruction, expanding beyond traditional occupancy-based pharmacology.

CRISPR Gene Editing: The 2025 case of a seven-month-old infant receiving personalized CRISPR base-editing therapy developed in just six months demonstrates rapid-response capability [7]. In vivo CRISPR therapies for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (e.g., CTX310 reducing LDL by 86% in Phase 1) show potential for durable treatments [7].

Radiopharmaceutical Conjugates: Combining targeting molecules with radioactive isotopes enables highly localized therapy while sparing healthy tissues [7]. These theranostic approaches provide both imaging and treatment capabilities.

Host-Directed Antivirals: Instead of targeting rapidly evolving viruses, these therapies target human proteins that viruses exploit, potentially providing more durable protection against mutating pathogens [7].

The evolutionary framework in drug discovery provides both a explanatory model for current challenges and a strategic roadmap for improvement. By recognizing that attrition represents a selection process, researchers can focus on enhancing the fitness of candidate molecules through genetic validation, AI-driven design, and early DMPK profiling. The declining success rates paradoxically signal progress as the field tackles more scientifically challenging diseases rather than producing "me-too" therapies [2].

The future lies in evolutionary forecasting – developing predictive models that can accurately simulate the fitness of drug candidates in human systems before extensive experimental investment. This approach integrates genetic evidence from nature's laboratory with advanced in silico tools and functionally relevant experimental systems. As the field progresses, the organizations that thrive will be those that most effectively learn from and leverage these evolutionary principles to design fitter drug candidates from the outset, ultimately transforming drug discovery from a screening process to a predictive engineering discipline.

The Red Queen Hypothesis, derived from evolutionary biology, provides a powerful framework for understanding the relentless, co-evolutionary dynamics between therapeutic innovation and drug safety monitoring in the pharmaceutical industry. This hypothesis, which posits that organisms must constantly adapt and evolve merely to maintain their relative fitness, mirrors the pharmaceutical sector's continuous struggle to advance medical treatments while simultaneously managing emerging risks and adapting to an evolving regulatory landscape. This whitepaper examines the foundational principles of this evolutionary arms race, analyzes quantitative data on its impacts, and explores forward-looking strategies—including evolutionary forecasting and advanced computational models—that aim to proactively navigate these pressures. The integration of these evolutionary concepts is crucial for developing a more predictive, adaptive, and resilient drug development ecosystem.

In evolutionary biology, the Red Queen Hypothesis describes a phenomenon where species must continuously evolve and adapt not to gain an advantage, but simply to survive in the face of evolving competitors and a changing environment [8]. The name is borrowed from Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, where the Red Queen tells Alice, "it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place" [9]. This concept was formally proposed by Leigh Van Valen in 1973 to explain how reciprocal evolutionary effects among species can lead to a constant-rate extinction probability observed in the fossil record [8].

When applied to the pharmaceutical industry, this hypothesis aptly describes the relentless cycle of adaptation between several forces: therapies that constantly improve but face evolving resistance and safety concerns; pathogens and diseases that develop resistance to treatments; regulatory frameworks that evolve in response to past safety issues; and monitoring systems that must advance to detect novel risks. This creates a system where continuous, often resource-intensive, innovation is required just to maintain current standards of patient safety and therapeutic efficacy [9]. This coevolutionary process is not a series of isolated events but a continuous, interconnected feedback loop, the dynamics of which are essential for understanding the challenges of modern drug development.

Historical Evolution of Pharmacovigilance as a Red Queen Process

The development of pharmacovigilance—the science of monitoring drug safety—is a quintessential example of a Red Queen process. Its history is marked by tragic events that spurred regulatory evolution, which in turn necessitated further innovation in risk management.

Table 1: Major Milestones in the Evolution of Pharmacovigilance

| Year | Event | Regulatory/System Response | Impact on Innovation/Safety Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1848 | Death of Hannah Greener from chloroform anesthesia [10] [11] | The Lancet established a commission to investigate anesthesia-related deaths [10]. | Established early principle that systematic data collection is needed to understand drug risks. |

| 1937 | 107 deaths in the USA from sulfanilamide elixir with diethyl glycol [10] [11] | Passage of the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938), requiring drug safety demonstration pre-market [10] [11]. | Introduced the concept of pre-market safety testing, lengthening development timelines to enhance safety. |

| 1961 | Thalidomide tragedy linking the drug to congenital malformations [10] [11] | Worldwide strengthening of drug laws: 1962 Kefauver-Harris Amendments (USA), EC Directive 65/65 (Europe), spontaneous reporting systems, Yellow Card scheme (UK, 1964) [10] [11]. | Made pre-clinical teratogenicity testing standard; marked the birth of modern, systematic pharmacovigilance. |

| 1968 | -- | Establishment of the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring [10] [11]. | Created a global framework for sharing safety data, requiring international standardization of processes. |

| 2004-2012 | Withdrawal of Rofecoxib and other high-profile safety issues [11] | EU Pharmacovigilance Legislation (Directive 2010/84/EU): strengthened EudraVigilance, established PRAC, mandated Risk Management Plans [10] [11]. | Shifted focus from reactive to proactive risk management, increasing the data and planning burden on companies. |

This historical progression demonstrates a clear pattern: a drug safety crisis leads to stricter regulations, which in turn forces innovation in risk assessment and monitoring methodologies. As noted in one analysis, "advances in science that increase our ability to treat diseases have been matched by similar advances in our understanding of toxicity" [9]. This is the Red Queen in action—running to stay in place. The regulatory environment does not remain static, and the standards for safety and efficacy that a new drug must meet are continually evolving, requiring developers to be increasingly sophisticated.

Quantitative Evidence of the Pharmaceutical Red Queen

The pressures of this evolutionary race are quantifiable in industry performance and resource allocation. Key metrics reveal a landscape of increasing complexity and cost.

Table 2: Quantitative Data Reflecting Industry Pressures

| Metric | Historical Data | Current/Trend Data | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Drug Approvals | 131 applications for new active compounds in 1996 [9]. | 48 applications in 2009 [9]. | Suggests a declining output of new chemical entities, potentially due to increasing hurdles. |

| R&D Cost & Efficiency | -- | PwC estimates AI could deliver ~$250 billion of value by 2030 [12]. | Highlights massive efficiency potential, necessitating new skills and technologies to realize. |

| Skills Gap Impact | -- | 49% of industry professionals report a skills shortage as the top hindrance to digital transformation [12]. | A failure to adapt the workforce directly impedes the industry's ability to evolve and keep pace. |

| Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) Burden | -- | ADRs cause ~5% of EU hospital admissions, ranked 5th most common cause of hospital death, costing €79 billion/year [11]. | Underscores the constant and significant pressure from safety issues that the system must address. |

The data on declining new drug applications is particularly telling. As one analysis put it, "This decline brings to mind endangered species, where it becomes important to identify deteriorating environments to prevent extinction" [9]. The environment for drug discovery has become more demanding, and the industry must evolve rapidly to avoid a decline in innovation.

Evolutionary Forecasting: A Framework for Proactive Adaptation

The emerging field of evolutionary forecasting offers tools to break free from a purely reactive cycle. The goal is to move from observing evolution to predicting and even controlling it [13]. This is directly applicable to predicting pathogen resistance, cancer evolution, and patient responses to therapy.

The scientific basis for these predictions rests on Darwin's theory of natural selection, augmented by modern population genetics, which accounts for forces like mutation, drift, and recombination [13]. The predictability of evolution is highest over short timescales, where the paths available to a population are more constrained [13].

Table 3: Methods for Evolutionary Prediction and Control in Pharma

| Method Category | Description | Pharmaceutical Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Population Genetic Models | Quantitative models incorporating selection, mutation, drift, and migration. | Predicting the rate of antibiotic resistance evolution in bacteria based on mutation rates and selection pressure. |

| Statistical/Machine Learning Models | Using patterns in large datasets (e.g., viral genome sequences) to forecast future states. | The WHO's seasonal influenza vaccine strain selection, which predicts dominant variants months in advance [13]. |

| Experimental Evolution | Directly evolving pathogens or cells in the lab under controlled conditions (e.g., with drug gradients). | Identifying likely resistance mutations to a new anticancer drug before it reaches clinical trials. |

| Genomic Selection | Using genome-wide data to predict the value of traits for selective breeding; can be adapted for microbial engineering. | Selecting or engineering high-yielding microbial strains for biopharmaceutical manufacturing [13]. |

A key application is evolutionary control: altering the evolutionary process with a specific purpose [13]. In pharma, this can mean designing treatment regimens to suppress resistance evolution—for example, using drug combinations or alternating therapies to guide pathogens toward evolutionary dead-ends [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Studies

To operationalize evolutionary forecasting, researchers rely on a suite of advanced tools and reagents that enable high-throughput experimentation and detailed genomic analysis.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Evolutionary Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in Evolutionary Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Random Mutagenesis Libraries | Generates vast diversity of genetic variants (e.g., in promoters or coding sequences) for screening. | Training neural network models to map DNA sequence to function and predict evolutionary outcomes [14]. |

| Barcoded Strain Libraries | Allows simultaneous tracking of the fitness of thousands of different microbial strains in a competitive pool. | Measuring the fitness effects of all possible mutations in a gene or regulatory region under drug pressure. |

| ChIP-seq Kits (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) | Identifies genomic binding sites for transcription factors and other DNA-associated proteins. | Constructing gold-standard regulatory networks to validate predictive algorithms like MRTLE [15]. |

| Long-read Sequencing Platforms (e.g., PacBio, Nanopore) | Provides accurate sequencing of long DNA fragments, enabling resolution of complex genomic regions. | Tracking the evolution of entire gene clusters and structural variations in pathogens or cancer cells over time. |

| Dual-RNAseq Reagents | Allows simultaneous transcriptome profiling of a host and an infecting pathogen during interaction. | Studying co-evolutionary dynamics in real-time, a key aspect of the Red Queen Hypothesis [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Predicting Regulatory Evolution in Yeast

A groundbreaking study from MIT exemplifies the experimental approach to building predictive models of regulatory evolution [14]. The following protocol details their methodology.

Objective: To create a fitness landscape model capable of predicting how any possible mutation in a non-coding regulatory DNA sequence (promoter) will affect gene expression and organismal fitness.

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Library Generation and Transformation: Synthesize a library of tens to hundreds of millions of completely random DNA sequences designed to replace the native promoter of a reporter gene in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Use high-efficiency transformation to ensure broad representation of the library within the yeast population [14].

High-Throughput Phenotyping: Grow the transformed yeast population under defined selective conditions. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate yeast cells based on the expression level of the reporter gene (e.g., low, medium, high fluorescence). This quantitatively links each random promoter sequence to a specific expression output [14].

Sequence Recovery and Quantification: Isolate genomic DNA from the sorted population pools. Use high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina) to count the abundance of each unique promoter sequence in each expression bin. This generates a massive dataset linking DNA sequence to gene expression level [14].

Model Training and Validation: Train a deep neural network on the dataset, using the DNA sequence as the input and the measured expression level as the output. The model learns the "grammar" of regulatory sequences. Validate the model's predictive power by testing its predictions on held-out data and on known, engineered promoter sequences not seen during training [14].

Landscape Visualization and Prediction: Develop a computational technique to project the high-dimensional fitness landscape predictions from the model onto a two-dimensional graph. This allows for intuitive visualization of evolutionary paths, potential endpoints, and the effect of any possible mutation, effectively creating an "oracle" for regulatory evolution [14].

The Red Queen Hypothesis provides a profound and validated lens through which to view the history and future of pharmaceutical development. The industry is inextricably locked in a co-evolutionary dance where advances in therapy, shifts in pathogen resistance, and enhancements in safety science perpetually drive one another forward. The challenge of "running to stay in place" is evident in the declining output of new drugs and the rising costs of development.

However, the nascent field of evolutionary forecasting offers a path toward a more intelligent and proactive equilibrium. By leveraging sophisticated computational models, high-throughput experimental data, and AI, the industry can aspire not just to react to evolutionary pressures, but to anticipate and manage them. This shift—from being a passive participant to an active director of evolutionary processes—holds the key to breaking the costly cycle of reactive innovation. The future of pharma lies in learning not just to run faster, but to run smarter, using predictive insights to navigate the evolutionary landscape and ultimately deliver safer, more effective therapies in a more efficient and sustainable manner.

The process of drug discovery and development is a complex, high-stakes endeavor that exhibits many characteristics of an evolutionary system. It is a process defined by variation, selection, and retention, where a vast number of candidate molecules are generated, and only a select few survive the rigorous journey to become approved medicines [9]. This evolutionary process is shaped by three fundamental forces: the availability and flow of funding, which acts as the lifeblood of research; the regulatory and technological environment, which sets the rules for survival; and the contributions of individual genius, whose unique insights can catalyze paradigm shifts [9]. Analyzing these forces is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for developing robust evolutionary forecasts that can guide future R&D strategy, optimize resource allocation, and ultimately enhance the probability of delivering new therapies to patients. This paper examines these forces through historical and contemporary lenses, providing a structured analysis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Funding Landscape: Oxygen for Innovation

Funding is the essential resource that fuels the drug discovery ecosystem, much as oxygen and glucose are fundamental to biological systems [9]. The sources and allocation of this funding create a powerful selection pressure that determines which research paths are pursued and which are abandoned.

Historical and Contemporary Funding Analysis

The global pharmaceutical industry is projected to reach approximately $1.6 trillion in spending by 2025, reflecting a steady compound annual growth rate [16]. Beneath this aggregate figure lies a complex funding landscape spanning public, private, and venture sources.

Table 1: Key Funding Sources and Their Impact in Drug Discovery

| Funding Source | Historical Context & Scale | Strategic Impact & Selection Pressure |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Industry R&D | Annual industry R&D investment exceeds $200 billion [16]. Historically, ~14% of sales revenue is reinvested in R&D [9]. | Traditionally prioritizes targets with clear market potential. Drives large-scale clinical trials but can disfavor niche or high-risk exploratory research. |

| Public & Non-Profit Funding | U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) annual budget ~£20 billion; UK MRC/Wellcome/CRUK ~£1 billion combined [9]. | Supports foundational, basic research that de-risks early discovery. The Berry Plan (1954-1974) created a "Golden Age" by directing medical talent to NIH [9]. |

| Biotech Venture Funding | 2021 peak of $70.9 billion in venture funding [17]. Q2 2024 saw $9.2 billion across 215 deals, signaling recovery [18]. | Fuels high-innovation, nimble entities. Investors are increasingly selective, favoring validated targets and clear biomarker strategies [17]. |

Funding as an Evolutionary Selection Mechanism

The distribution of funding acts as a key selection mechanism within the drug discovery ecosystem. A challenging interaction exists between the inventor and the investor, which has been analogized to "mating porcupines" [9]. This dynamic is evident in the shifting patterns of innovation. While large pharmaceutical companies invest the largest sums, studies show that biotech companies have outpaced large pharmaceutical companies in creating breakthrough therapies, producing 40% more FDA-approved "priority" drugs between 1998 and 2016 despite spending less in aggregate [16]. This has led to the emergence of the biotech-leveraged pharma company (BIPCO) model and is now evolving into new models like the technology-investigating pharma company (TIPCO) and asset-integrating pharma company (AIPCO) [19]. The recent market correction in 2022-2023 forced a reassessment of priorities, and while funding remains substantial, it is now exclusively directed toward programs with validated targets, strong biomarker evidence, and well-defined regulatory strategies [17].

The Environmental Landscape: The Rules of Survival

The environment in which drug discovery operates—comprising regulatory frameworks, technological advancements, and market dynamics—defines the "rules of survival." This environment is not static; it evolves in response to scientific progress, public health crises, and societal expectations.

The Regulatory and "Red Queen" Effect

The regulatory landscape presents a classic "Red Queen" effect, where developers must run faster just to maintain their place [9]. As therapeutic science advances, so does the understanding of toxicity and the complexity of required trials. While tougher regulation is often cited as a barrier, data does not fully support this; the number of new drug applications fell from 131 in 1996 to 48 in 2009, yet the approval rate in the EU actually increased from 29% to 60% over the same period [9]. This suggests that the primary challenge is not necessarily over-regulation but a potential mismatch between scientific ambition and the ability to demonstrate clear patient benefit within the current framework. Modern regulators require increasingly sophisticated data packages, and the cost of failure is immense, with only 5.3% of oncology programs and 7.9% of all development programs ultimately succeeding [17].

Technological Disruption and Environmental Shift

Technological advancements represent environmental upheavals that can rapidly reshape the entire discovery landscape. The most transformative recent shift is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI). By 2025, it is estimated that 30% of new drugs will be discovered using AI, reducing discovery timelines and costs by 25-50% in preclinical stages [18]. AI leverages machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) to enhance target validation, small molecule design, and prediction of physicochemical properties and toxicity [20] [21]. Beyond AI, other technological shifts include:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Allows for the rapid testing of millions of compounds, moving from a serendipitous process to a precision-guided endeavor [22].

- Advanced Databases: Resources like PubChem, ChEMBL, and the Protein Data Bank provide invaluable structural and bioactivity data that streamline lead identification [22].

- Cell and Gene Therapies (CGTs): This modality represents a paradigm shift, particularly with recent approvals for solid tumors. The CGT market is predicted to reach $74.24 billion by 2027 [17].

Diagram: The "Red Queen" Effect in Drug Discovery Evolution

The Force of Individual Genius: Catalysts of Variation

Within the evolutionary framework of systemic forces, the individual researcher remains a critical source of variation—the "mutations" that can drive the field forward. History shows that single individuals with deep expertise and dedication can achieve breakthroughs that reshape therapeutic areas.

Case Studies of Paradigm-Shifting Contributions

The contributions of Gertrude Elion, James Black, and Akira Endo exemplify how individual genius can act as a potent evolutionary force [9]. Their work demonstrates that small, focused teams can generate an outsized impact.

Table 2: Profiles of Individual Genius in Drug Discovery

| Scientist | Core Discovery & Approach | Therapeutic Impact & Legacy |

|---|---|---|

| Gertrude Elion | Rational drug design via purine analog synthesis. Key methodology: systematic molecular modification to alter function. | Multiple first-in-class agents: 6-mercaptopurine (leukaemia), azathioprine (transplantation), aciclovir (herpes). Trained a generation of AIDS researchers. |

| James Black | Receptor subtype targeting. Key methodology: development of robust lab assays to screen for specific receptor antagonists. | Pioneered β-blockers (propranolol) and H₂ receptor antagonists (cimetidine), creating two major drug classes and transforming CV and GI medicine. |

| Akira Endo | Systematic natural product screening. Key methodology: screened 6,000 fungal extracts for HMG CoA reductase inhibition. | Discovery of the first statin (compactin), founding the most successful drug class for cardiovascular disease prevention. |

A common theme among these innovators was their work within the pharmaceutical industry, their profound knowledge of chemistry, and their dedication to improving human health. They operated in teams of roughly 50 or fewer researchers, highlighting that focused individual brilliance within a supportive environment can be extraordinarily productive [9].

The Modern Manifestation of Individual Genius

In the contemporary landscape, the "individual genius" model has evolved. The complexity of modern biology and the rise of advanced technologies like AI have made solitary discovery less common. Today's innovators are often the architects of new technological platforms or the leaders of biotech startups who synthesize insights from vast datasets. The modern ecosystem relies on collaborative networks and open innovation models [16], where the individual's role is to connect disparate fields—for example, applying computational expertise to biological problems. The legacy of Elion, Black, and Endo continues not in isolation, but through individuals who drive cultural and technological shifts within teams and organizations.

The experimental protocols of drug discovery rely on a foundational set of reagents, databases, and tools. These resources enable the key methodologies that drive the field forward, from target identification to lead optimization.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Modern Drug Discovery

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| PubChem | Database | A vast repository of chemical compounds and their biological activities, essential for initial screening and compound selection [22]. |

| ChEMBL | Database | A curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR) [22]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Provides 3D structural information of biological macromolecules, enabling structure-based drug design [22]. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Platform/Technology | Automated system for rapidly testing hundreds of thousands of compounds for activity against a biological target [22]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Instrument/Assay | An affinity-based technique that provides real-time, label-free data on the kinetics (association/dissociation) of biomolecular interactions [22]. |

| AI/ML Platforms (e.g., DeepVS) | Software/Tool | Uses deep learning for virtual screening, predicting how strongly small molecules will bind to a target protein, prioritizing compounds for synthesis [21]. |

| Fragment Libraries | Chemical Reagent | Collections of low molecular weight compounds used in fragment-based screening to identify weak but efficient binding starting points for lead optimization [22]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Fragment-Based Lead Discovery

The following protocol is a modern evolution of the systematic approaches used by historical figures like Akira Endo, now augmented by technology.

- Target Selection and Validation: Select a purified, recombinant protein target implicated in a disease pathway. Validate its functional activity and structural integrity.

- Fragment Library Screening: Screen a library of 500-2,000 low molecular weight fragments (<250 Da) using a biophysical method such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to identify initial binders [22].

- Hit Validation and Co-structure Determination: Validate primary hits using orthogonal assays (e.g., NMR, thermal shift). Attempt to obtain an X-ray co-crystal structure of the fragment bound to the target. This structural information is crucial for understanding the binding motif.

- Fragment Growing/Elaboration: Using the co-structure as a guide, chemically modify the fragment by adding functional groups to increase its potency and selectivity. This is an iterative process of chemical synthesis and biological testing.

- Lead Optimization: Once a potent compound series is established, optimize for full drug-like properties (potency, selectivity, ADMET - Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) using a combination of medicinal chemistry and AI-based predictive models [21].

Diagram: Core Workflow in Modern Lead Discovery

Synthesis and Evolutionary Forecasting

The evolutionary trajectory of drug discovery is governed by the continuous interaction of funding, environment, and individual ingenuity. Forecasting future success requires a dynamic model that accounts for all three forces.

- Funding Trends: The shift toward selective venture funding and the TIPCO/AIPCO models suggests that future winners will be those that can tightly integrate scientific promise with clear commercial and regulatory pathways [19]. Forecasting must account for capital flows into disruptive platforms like AI and CGTs.

- Environmental Pressures: The "Red Queen" effect will intensify. Regulators will demand more sophisticated real-world evidence and patient-centric outcomes. Forecasters should monitor regulatory approvals for novel modalities as indicators of environmental shift.

- The Modern "Genius": The individual's role is evolving into that of an integrator—someone who can bridge computational and wet-lab science, and navigate the complex biotech partnership landscape [16] [19]. Forecasting models must value leadership and cross-disciplinary collaboration as key success factors.

The historical reliance on serendipity has given way to a more calculated, strategic process [22]. The organizations most likely to thrive in the coming decade will be those that create environments and funding structures capable of attracting and empowering modern integrators, while adeptly navigating the accelerating demands of the regulatory and technological landscape. By applying this evolutionary lens, stakeholders can make more informed strategic decisions, ultimately increasing the efficiency and success of bringing new medicines to patients.

The predictability of evolution remains a central debate in evolutionary biology, hinging on the interplay between deterministic forces like natural selection and stochastic processes such as genetic drift. This guide synthesizes theoretical frameworks, quantitative models, and experimental methodologies to delineate the conditions under which evolutionary trajectories can be forecast. We explore how population size, fitness landscape structure, and genetic architecture jointly determine evolutionary outcomes. By integrating concepts from population genetics, empirical case studies, and emerging computational tools, this review provides a foundation for evolutionary forecasting research, with particular relevance for applied fields including antimicrobial and drug resistance management.

Evolution is a stochastic process, yet it operates within boundaries set by deterministic forces. The degree to which future evolutionary changes can be forecast depends critically on the relative influence and interaction between these factors. Deterministic processes, primarily natural selection, drive adaptive change in a direction that can be predicted from fitness differences among genotypes. In contrast, stochastic processes—including genetic drift, random mutation, and environmental fluctuations—introduce randomness and historical contingency, potentially rendering evolution unpredictable [23] [24].

The question of evolutionary predictability is not merely academic; it has profound implications for addressing pressing challenges in applied sciences. In drug development, predicting the emergence of resistance mutations in pathogens or cancer cells is essential for designing robust treatment strategies and combination therapies [25]. The global crisis of antimicrobial resistance is fundamentally driven by microbial adaptation, demanding predictive models of evolutionary dynamics to formulate effective solutions [25]. Similarly, in conservation biology, forecasting evolutionary responses to climate change informs strategies for managing biodiversity and facilitating evolutionary rescue in threatened populations.

This technical guide establishes a framework for analyzing predictability in evolutionary systems by examining the theoretical foundations, quantitative benchmarks, experimental approaches, and computational tools that define the field.

Theoretical Foundations: Selection, Drift, and Population Size

The predictable or stochastic nature of evolution is profoundly influenced by population genetics parameters. The selection-drift balance dictates that the relative power of natural selection versus genetic drift depends largely on the product of the effective population size (Nₑ) and the selection coefficient (s) [26].

Population Size Regimes and Evolutionary Behavior

Theoretical models reveal three broad regimes of evolutionary behavior across a gradient of population sizes:

The Neutral Limit (Small Nₑ): When Nₑ is very small or when |Nₑs| ≪ 1, stochastic processes dominate. Genetic drift causes random fluctuations in allele frequencies, overwhelming weak selective pressures. Evolution in this regime is largely unpredictable for individual lineages, following neutral theory predictions [26].

The Selection-Drift Regime (Intermediate Nₑ): In populations of intermediate size, both selection and drift exert significant influence. While beneficial mutations have a better chance of fixation than neutral ones, their trajectory remains somewhat stochastic. The dynamics in this regime are complex and particularly relevant for many natural populations, including pathogens like HIV within a host [26].

The Nearly Deterministic Limit (Large Nₑ): When Nₑ is very large and |Nₑs| ≫ 1, deterministic selection dominates. The fate of alleles with substantial fitness effects becomes highly predictable. In this regime, quasispecies theory and deterministic population genetics models provide accurate forecasts of evolutionary change [26].

Table 1: Evolutionary Regimes Defined by Population Size and Selection Strength

| Regime | Defining Condition | Dominant Process | Predictability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Limit | Nₑs | ≪ 1 | Genetic Drift | Very Low | |

| Selection-Drift | Nₑs | ≈ 1 | Selection & Drift | Intermediate | |

| Deterministic Limit | Nₑs | ≫ 1 | Natural Selection | High |

A Stochastic Framework for Evolutionary Change

The classic Price equation provides a deterministic description of evolutionary change but is poorly equipped to handle stochasticity. A generalized, stochastic version of the Price equation reveals that directional evolution is influenced by the entire distribution of an individual's possible fitness values, not just its expected fitness [27].

This framework demonstrates that:

- Stochastic variation amplifies selection in small or fluctuating populations.

- Populations are pulled toward phenotypes with not only minimum variance in fitness (even moments of the fitness distribution) but also maximum positive asymmetry (odd moments) [27].

- The direct effect of parental fitness on offspring phenotype represents an additional stochastic pathway not captured in traditional models.

These insights are formalized in the following conceptual diagram of evolutionary dynamics:

Quantitative Framework: Key Parameters and Data Limits

Predictive accuracy in evolution is constrained by both inherent randomness ("random limits") and insufficient knowledge ("data limits") [24]. The following table summarizes core parameters and their impact on predictability.

Table 2: Key Parameters Governing Evolutionary Predictability

| Parameter | Description | Quantitative Measure | Impact on Predictability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Coefficient (s) | Relative fitness difference | s = (w₁ - w₂)/w₂ | Higher | s | increases predictability |

| Effective Population Size (Nₑ) | Number of breeding individuals | Estimated from genetic data | Larger Nₑ increases predictability of selected variants | ||

| Mutation Rate (μ) | Probability of mutation per generation | Per base, per gene, or genome-wide | Higher μ increases potential paths, may decrease predictability | ||

| Recombination Rate (r) | Rate of genetic exchange | cM/Mb, probability per generation | Higher r breaks down LD, can increase predictability of response | ||

| Distribution of Mutational Effects (DME) | Spectrum of fitness effects | Mean and variance of s | Lower variance in DME increases predictability |

The Data Limits Hypothesis

Even deterministic evolution can be difficult to predict due to data limitations that cause poor understanding of selection and its environmental causes, trait variation, and inheritance [24]. These limits operate at multiple levels:

- Unpredictable Environmental Fluctuations: Environmental sources of selection (climate, predator abundance) may fluctuate deterministically yet appear random due to chaotic dynamics sensitive to initial conditions [24].

- Incomplete Understanding of Selection: Even with known environmental changes, predicting how these factors impose selection on phenotypes requires detailed knowledge of resource distributions and organismal ecology.

- Complex Genetic Architecture: The mapping from selective pressure to genetic change is complicated by epistasis, pleiotropy, polygenic inheritance, and phenotypic plasticity [24].

Overcoming these data limits requires integrating long-term monitoring with replicated experiments and genomic tools to dissect the genetic architecture of adaptive traits [24].

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Predictability

Microbial Evolution Experiments

Objective: To measure repeatability of evolutionary trajectories under controlled selective environments.

Protocol:

- Founder Strain Preparation: Start with a genetically identical clone of model microbes (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae).

- Replication: Establish multiple (≥6) independent replicate populations in identical environments.

- Selective Regime: Apply constant selection pressure (e.g., antibiotic gradient, novel carbon source, temperature stress).

- Longitudinal Sampling: Periodically archive frozen samples (every 50-100 generations) for downstream analysis.

- Phenotypic Monitoring: Measure fitness changes through competition assays against a marked reference strain.

- Genomic Analysis: Sequence whole genomes of evolved isolates to identify parallel mutations. Calculate the probability of parallel evolution—the likelihood that independent lineages mutate the same genes [23].

Interpretation: High parallelism in mutational targets indicates stronger deterministic selection and greater predictability.

Time-Series Allele Frequency Tracking

Objective: To compare observed evolutionary trajectories against model predictions.

Protocol:

- Field Sampling: Collect population samples across multiple generations (e.g., annually for vertebrates, seasonally for insects).

- Genotype-Phenotype Mapping: Conduct GWAS or QTL mapping to identify loci associated with traits under selection.

- Selection Gradient Analysis: Estimate the strength and form of selection by relating individual fitness to trait values.

- Environmental Covariates: Quantify relevant environmental variables (temperature, resource availability, predator density).

- Model Testing: Use time-series data to parameterize models and test their predictive accuracy for future time points [24].

Application: This approach has been successfully applied in systems such as Darwin's finches [24] and Timema stick insects [24] to quantify the predictability of contemporary evolution.

Visualization of Evolutionary Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for analyzing evolutionary predictability through combined experimental and computational approaches:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Evolutionary Predictability Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) Setup | Maintains replicated populations for thousands of generations | Study of parallel evolution in E. coli under glucose limitation |

| Barcoded Microbial Libraries | Tracks lineage dynamics through unique DNA barcodes | Measuring fitness of thousands of genotypes in parallel |

| Animal Model Cyrogenics | Preserves ancestral and intermediate generations | Resurrecting ancestral populations for fitness comparisons |

| Environmental Chamber Arrays | Controls and manipulates environmental conditions | Testing evolutionary responses to climate variables |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Genomes, transcriptomes, and population sequencing | Identifying mutations in evolved populations |

| Fitness Assay Platforms | Measures competitive fitness in controlled environments | Quantifying selection coefficients for specific mutations |

| Probabilistic Programming Languages | Implements complex Bayesian models for inference | Forecasting evolutionary trajectories from genomic data |

Emerging Frontiers and Computational Approaches

Machine learning and artificial intelligence are revolutionizing evolutionary prediction by identifying complex patterns in high-dimensional data that elude traditional statistical methods. These approaches are particularly powerful for:

- Inference of Demographic History: Deep learning models can infer population size changes, migration rates, and divergence times from genomic data [28].

- Predicting Antibiotic Resistance: Models trained on bacterial genome sequences can predict resistance phenotypes and evolutionary trajectories [25].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Convolutional neural networks can build phylogenetic trees from sequence data and identify complex morphological patterns [29].

- Lineage Tracing: AI methods help reconstruct evolutionary lineages from single-cell sequencing data, even without a known phylogenetic tree [29].

These methods are increasingly accessible through probabilistic programming languages like TreePPL, which enable more flexible model specification for complex evolutionary scenarios [29]. The emerging field of online phylogenetics provides computationally efficient methods for analyzing thousands of sequences in near real-time, crucial for tracking pandemic pathogens [29].

Predictability in evolution emerges from the tension between deterministic selection and stochastic processes. While fundamental limits exist due to random mutation, drift, and historical contingency, significant predictive power is achievable for many evolutionary scenarios, particularly those involving strong selection in large populations. Future progress will depend on overcoming data limitations through integrated experimental and observational studies, leveraging emerging computational tools like machine learning, and developing more comprehensive theoretical frameworks that account for the full complexity of evolutionary systems. The resulting predictive capacity holds immense promise for addressing critical challenges in medicine, agriculture, and conservation biology.

Computational Arsenal: AI and Evolutionary Algorithms for Predictive Modeling

Artificial intelligence (AI) has progressed from an experimental curiosity to a clinically utility, driving a paradigm shift in therapeutic development by replacing labor-intensive, human-driven workflows with AI-powered discovery engines [30]. This transition is particularly transformative in the domain of target discovery and validation, the critical first step in the drug development pipeline. AI-driven target discovery leverages machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) to systematically decode complex biological data, identifying molecular entities with a high probability of therapeutic success. The integration of these technologies compresses discovery timelines, expands chemical and biological search spaces, and redefines the speed and scale of modern pharmacology [30]. Companies like Insilico Medicine, Recursion, and Owkin have demonstrated that AI can accelerate target identification from a typical six months to as little as two weeks, showcasing the profound efficiency gains possible [31]. This technical guide examines the foundations of AI-driven target discovery and validation, framing its methodologies within the context of evolutionary forecasting research, which uses computational models to predict biological trajectories and optimize therapeutic interventions.

Core AI Methodologies and Their Biological Applications

The AI toolkit for target discovery encompasses a diverse set of computational approaches, each suited to particular data types and biological questions. Understanding these methodologies is prerequisite for designing effective discovery campaigns.

2.1 Machine Learning Paradigms Machine learning employs algorithmic frameworks to analyze high-dimensional datasets, identify latent patterns, and construct predictive models through iterative optimization [32]. Its application in target discovery follows several distinct paradigms:

Supervised Learning utilizes labeled datasets for classification and regression tasks. Algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and Random Forests (RFs) are trained on known drug-target interactions to predict novel associations [32]. For example, a classifier can be trained to distinguish between successful and failed targets based on features extracted from historical clinical trial data [31].

Unsupervised Learning identifies latent data structures without pre-existing labels through clustering and dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal component analysis and K-means clustering [32]. This approach can reveal novel target classes or disease subtypes by grouping genes or proteins with similar expression patterns across diverse biological contexts [33].

Semi-supervised Learning boosts drug-target interaction prediction by leveraging a small set of labeled data alongside a large pool of unlabeled data. This is achieved through model collaboration and by generating simulated data, which enhances prediction reliability, especially when comprehensive labeled datasets are unavailable [32].

Reinforcement Learning optimizes molecular design via Markov decision processes, where agents iteratively refine policies to generate inhibitors and balance pharmacokinetic properties through reward-driven strategies [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring vast chemical spaces in silico.

2.2 Deep Learning Architectures Deep learning, a subset of ML utilizing multi-layered neural networks, excels at processing complex, high-dimensional data like genomic sequences, imaging data, and protein structures [33].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are predominantly applied to image-based data, such as histopathology slides or cellular imaging from high-content screening. For instance, Recursion uses AI-powered image analysis to spot subtle changes in cell morphology and behavior in response to drugs or genetic perturbations that can reveal new drug targets [31].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) operate on graph-structured data, making them ideal for analyzing biological networks, including protein-protein interaction networks, metabolic pathways, and knowledge graphs that link genes, diseases, drugs, and patient characteristics [31].

Large Language Models (LLMs) and protein language models, trained on vast corpora of biological literature and protein sequence databases, can connect unstructured insights from scientific literature with structured data, complementing AI predictions with published knowledge [31]. These models have demonstrated capability in predicting protein interactions and generating functional protein sequences [28].

2.3 Evolutionary Computation Evolutionary computation (EC) offers particular promise for target discovery as most discovery problems are complex optimization problems beyond conventional algorithms [34]. EC methods have been widely applied to solve these challenges, substantially speeding up the process [34]. The RosettaEvolutionaryLigand (REvoLd) algorithm exemplifies this approach, using an evolutionary algorithm to search combinatorial make-on-demand chemical spaces efficiently without enumerating all molecules [35]. This algorithm explores vast search spaces for protein-ligand docking with full flexibility, demonstrating improvements in hit rates by factors between 869 and 1622 compared to random selections [35].

Figure 1: AI Methodology Selection Framework for Target Discovery

The AI-Driven Target Discovery Workflow: From Data to Candidate

A systematic workflow is essential for translating raw biological data into validated therapeutic targets. This process integrates multiple AI methodologies and experimental validation in an iterative cycle.

3.1 Data Acquisition and Curation The first step involves gathering multimodal data from diverse sources. As exemplified by Owkin's Discovery AI platform, this includes gene mutational status, tissue histology, patient outcomes, bulk gene expression, single-cell gene expression, spatially resolved gene expression, and clinical records [31]. Additional critical data sources include existing knowledge on target druggability, gene expression across cancers and healthy tissues, phenotypic impact of gene expression in cancer cells (from datasets like ChEMBL and DepMap), and past clinical trial results [31]. The quality and representativeness of this data fundamentally determines AI model performance, necessitating rigorous curation and normalization procedures.

3.2 Feature Engineering and Model Training After data acquisition, feature engineering extracts biologically relevant predictors. This involves both human-specified features (e.g., cellular localization) and AI-extracted features from data modalities like H&E stains and genomic data [31]. In advanced platforms, approximately 700 features with depth in spatial transcriptomics and single-cell modalities can be extracted [31]. These features are fed into machine learning classifiers that identify which features are predictive of target success in clinical trials. The models are validated on historical clinical trial outcomes of known targets to ensure predictive accuracy [31].

3.3 Target Prioritization and Scoring AI systems evaluate potential targets against three critical criteria: efficacy, safety, and specificity [31]. The models produce a score for each target representing its potential for success in treating a given disease, while also predicting potential toxicity [31]. For example, AI can analyze how a target is expressed across different healthy tissues and predict high expression in critical organs like kidneys, flagging potential toxicity risks early in the process [31]. Optimization methods can further identify patient subgroups that will respond better to a given target, enabling precision medicine approaches [31].

3.4 Experimental Validation and Model Refinement AI-identified targets require experimental validation in biologically relevant systems. AI can guide this process by recommending appropriate experimental models (e.g., specific cell lines or organoids) and conditions that best mimic the disease environment [31]. As validation data is generated, AI models undergo continuous retraining on both successes and failures from past experiments and clinical trials, allowing them to become smarter over time [31]. This creates a virtuous cycle of improvement where each experimental outcome enhances the predictive capability of the AI.

Figure 2: AI-Driven Target Discovery and Validation Workflow

Quantitative Landscape: AI-Discovered Compounds in Clinical Development

The impact of AI-driven discovery is quantifiably demonstrated by the growing pipeline of AI-discovered therapeutics advancing through clinical trials. The following tables summarize key compounds and performance metrics.

Table 1: Selected AI-Discovered Small Molecules in Clinical Trials (2025)

| Small Molecule | Company | Target | Stage | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INS018-055 | Insilico Medicine | TNIK | Phase 2a | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| ISM-6631 | Insilico Medicine | Pan-TEAD | Phase 1 | Mesothelioma, Solid Tumors |

| ISM-3412 | Insilico Medicine | MAT2A | Phase 1 | MTAP−/− Cancers |

| GTAEXS617 | Exscientia | CDK7 | Phase 1/2 | Solid Tumors |

| EXS4318 | Exscientia | PKC-theta | Phase 1 | Inflammatory/Immunologic Diseases |

| REC-1245 | Recursion | RBM39 | Phase 1 | Biomarker-enriched Solid Tumors/Lymphoma |

| REC-3565 | Recursion | MALT1 | Phase 1 | B-Cell Malignancies |

| REC-4539 | Recursion | LSD1 | Phase 1/2 | Small-Cell Lung Cancer |

| REC-3964 | Recursion | C. diff Toxin Inhibitor | Phase 2 | Clostridioides difficile Infection |

| RLY-2608 | Relay Therapeutics | PI3Kα | Phase 1/2 | Advanced Breast Cancer |

Source: Adapted from [32]

Table 2: Performance Metrics of AI-Driven Discovery Platforms

| Metric | Traditional Discovery | AI-Driven Discovery | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery to Phase I Timeline | ~5 years | 18-24 months | Insilico Medicine's IPF drug [30] |

| Design Cycle Efficiency | Baseline | ~70% faster | Exscientia's in silico design [30] |

| Compounds Synthesized | Baseline | 10× fewer | Exscientia's automated platform [30] |

| Target Identification | 6 months | 2 weeks | Owkin-Sanofi collaboration [31] |

| Virtual Screening Enrichment | Baseline | 869-1622× improvement | REvoLd benchmark [35] |

Experimental Protocols for AI-Driven Target Validation

Translating AI-derived target hypotheses into validated candidates requires rigorous experimental protocols. The following methodologies represent current best practices.

5.1 Multi-modal Data Integration Protocol This protocol enables the integration of diverse data types for comprehensive target assessment:

Step 1: Data Collection - Aggregate multimodal data including genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, histopathological, and clinical data from patient cohorts and public repositories like TCGA. For spatial biology context, leverage proprietary datasets like the MOSAIC multiomic spatial database [31].

Step 2: Data Preprocessing - Normalize datasets to account for platform-specific biases and batch effects. Implement quality control metrics to exclude low-quality samples.

Step 3: Feature Extraction - Extract approximately 700 features encompassing spatial transcriptomics, single-cell modalities, and knowledge graph-derived relationships [31]. Combine human-specified features (e.g., cellular localization) with AI-discovered features from unstructured data.

Step 4: Model Training - Train classifier models using historical clinical trial outcomes as ground truth. Employ ensemble methods to combine predictions from multiple algorithm types.

Step 5: Cross-validation - Validate model performance using leave-one-out cross-validation or time-split validation to ensure generalizability to novel targets.

5.2 AI-Guided Experimental Validation Protocol Once targets are prioritized, this protocol guides their biological validation:

Step 1: Model System Selection - Use AI recommendations to select experimental models (cell lines, organoids, patient-derived xenografts) that closely resemble the patient population from which the target was identified [31].

Step 2: Experimental Design - Implement AI-suggested conditions that best mimic the disease microenvironment, including specific combinations of immune cells, oxygen levels, or treatment backgrounds [31].

Step 3: High-Content Screening - For phenotypic screening, utilize automated platforms like Recursion's phenomics platform that apply AI-powered image analysis to detect subtle cellular changes [30].

Step 4: Multi-parameter Assessment - Evaluate efficacy, selectivity, and early toxicity signals in parallel. For toxicity assessment, prioritize testing in healthy tissue models based on AI-predicted expression patterns [31].

Step 5: Iterative Refinement - Feed experimental results back into AI models to refine predictions and guide subsequent validation experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Target Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Organoids | Physiologically relevant disease modeling | Testing AI-predicted targets in context-specific microenvironments [36] |

| Multiplex Immunofluorescence Reagents | Spatial profiling of tumor microenvironment | Validating AI-identified spatial biology features [31] |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | High-throughput functional genomics | Experimental validation of AI-predicted essential genes [33] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Kits | Cellular heterogeneity resolution | Confirming AI-identified cell-type specific targets [31] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Signaling pathway activation assessment | Validating AI-predicted mechanism of action |

| Cloud Computing Resources | AI model training and deployment | Running evolutionary algorithms and deep learning models [35] |

Evolutionary Forecasting in AI-Driven Discovery

Evolutionary forecasting provides a conceptual framework for understanding how AI systems can predict biological trajectories and optimize therapeutic interventions over time.

6.1 Evolutionary Computation in Chemical Space Exploration Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) applied to drug discovery embody principles of evolutionary forecasting by simulating selection pressures to optimize molecular structures. The REvoLd algorithm exemplifies this approach, using an evolutionary protocol to search ultra-large make-on-demand chemical spaces [35]. The algorithm maintains a population of candidate molecules that undergo iterative selection, crossover, and mutation operations, with fitness defined by docking scores against protein targets [35]. This methodology efficiently explores combinatorial chemical spaces without enumerating all possible molecules, demonstrating the power of evolutionary principles to navigate vast optimization landscapes.

6.2 Continuous Learning from Clinical Trial Evolution AI platforms for target discovery increasingly incorporate evolutionary principles through continuous learning from the "fitness" of drug targets as determined by clinical trial outcomes. As exemplified by Owkin's platform, models are continuously retrained on both successes and failures from past clinical trials, allowing them to become smarter over time [31]. This evolutionary approach to model refinement enables AI systems to adapt to changing understanding of disease biology and clinical development paradigms.

6.3 Forecasting Resistance Evolution The most advanced applications of evolutionary forecasting in AI-driven discovery involve predicting the evolution of drug resistance. By analyzing evolutionary patterns in pathogen genomes or cancer cells, AI models can forecast resistance mechanisms and design next-generation therapeutics that preempt these evolutionary escapes. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology and infectious disease, where resistance frequently limits therapeutic efficacy.

Regulatory and Implementation Considerations

The integration of AI into target discovery necessitates careful attention to regulatory expectations and practical implementation challenges.

7.1 Regulatory Landscape Regulatory agencies have developed evolving frameworks for evaluating AI in drug development. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has received over 500 submissions incorporating AI components across various stages of drug development [37]. The FDA's approach is characterized as flexible and dialog-driven, encouraging innovation through individualized assessment [37]. In contrast, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has established a structured, risk-tiered approach that mandates comprehensive documentation, representativeness assessments, and strategies to address class imbalances and potential discrimination [37]. The EMA's framework explicitly prefers interpretable models but acknowledges black-box models when justified by superior performance, requiring explainability metrics and thorough documentation [37].

7.2 Implementation Challenges Successful implementation of AI-driven target discovery faces several significant challenges:

Data Quality and Bias: AI models are vulnerable to biases and limitations in training data. Incomplete, biased, or noisy datasets can lead to flawed predictions [33]. Ensuring data representativeness across diverse patient populations is essential for equitable target discovery.

Interpretability and Explainability: The "black box" nature of many complex AI models, especially deep learning, limits mechanistic insight into their predictions [33]. Regulatory agencies and scientific peers increasingly require explanations for AI-derived target hypotheses, driving development of explainable AI techniques [37].

Workflow Integration: Adoption requires cultural shifts among researchers, clinicians, and regulators, who may be skeptical of AI-derived insights [33]. Successful implementation involves embedding AI tools into existing research workflows with appropriate guardrails and validation protocols.

Validation Standards: Predictions require extensive preclinical and clinical validation, which remains resource-intensive [33]. The field lacks standardized benchmarks for evaluating AI-derived target hypotheses, though initiatives are emerging to address this gap.

Future Directions: Toward Agentic AI and Predictive Biology

The trajectory of AI-driven target discovery points toward increasingly autonomous and predictive systems. Next-generation approaches include agentic AI that can learn from previous experiments, reason across multiple biological data types, and simulate how specific interventions are likely to behave in different experimental models [31]. Platforms like Owkin's K Pro represent early examples of this trend, packaging accumulated biological knowledge into agentic AI co-pilots that facilitate rapid investigation of biological questions [31]. In the future, such systems may predict experimental outcomes before they're conducted, dramatically narrowing which hypotheses warrant empirical testing [31]. This progression toward predictive biology, grounded in evolutionary forecasting principles, promises to further compress discovery timelines and increase the success probability of therapeutic programs, ultimately delivering better medicines to patients faster.

The field of drug discovery is undergoing a profound transformation, moving away from traditional trial-and-error approaches toward a systematic, predictive science powered by generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). This shift represents a cornerstone of evolutionary forecasting research, which seeks to predict and guide molecular adaptation for therapeutic purposes. Traditional virtual screening methods must explore an expansive and vast chemical space of up to 10^60 drug-like compounds and remain constrained by existing chemical libraries [38]. In contrast, generative de novo design—also known as inverse molecular design—reverses this paradigm by starting with desired molecular properties and generating novel chemical structures that fulfill these specific criteria [38] [39]. This inverse design approach allows researchers to map specific property profiles back to vast chemical spaces, generating novel molecular structures tailored to optimal therapeutic characteristics [40]. The application of AI, particularly deep learning, to evolutionary genomics and molecular design is still in its infancy while showing promising initial results [28]. This technical guide explores the core architectures, optimization strategies, and experimental frameworks that constitute this revolutionary approach to molecular design.

Core Generative Architectures for Molecular Design

Several deep learning architectures form the foundation of modern generative molecular design. Each offers distinct advantages for navigating chemical space and generating novel molecular structures with desired properties.

Transformer-based Models

Originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), transformers have been successfully adapted for molecular generation by treating Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings as a chemical "language" [41] [38]. These models utilize an auto-regressive generation process where the probability of generating a specific token sequence (T) is given by:

[ \textbf{P} (T) = \prod{i=1}^{\ell }\textbf{P}\left( ti\vert t{i-1}, t{i-2},\ldots, t_1\right) ]

For conditional generation, where output depends on input sequence (S), the probability becomes:

[ \textbf{P} (T\vert S) = \prod{i=1}^{\ell }\textbf{P}\left( ti\vert t{i-1}, t{i-2},\ldots, t_1, S\right) ]

Recent advancements include specialized transformer variants such as GPT-RoPE, which implements rotary position embedding to better capture relative position dependencies in molecular sequences, and T5MolGe, which employs a complete encoder-decoder architecture to learn mapping relationships between conditional properties and SMILES sequences [38].

Alternative Generative Architectures

Beyond transformers, several other architectures contribute distinct capabilities to molecular generation: