Evolutionary Predictability in Molecular Ecology: From Genetic Determinism to Biomedical Applications

This article explores the emerging science of evolutionary predictability within molecular ecology, synthesizing theoretical foundations with practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals.

Evolutionary Predictability in Molecular Ecology: From Genetic Determinism to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the emerging science of evolutionary predictability within molecular ecology, synthesizing theoretical foundations with practical applications for researchers and drug development professionals. It examines the core tension between stochastic evolutionary forces and deterministic patterns observed in molecular evolution, reviewing evidence from convergent evolution, experimental evolution studies, and viral genomics. The content covers predictive methodologies from fitness landscape modeling to genomic selection, addresses key challenges like epistasis and data limitations, and validates approaches through comparative analysis across biological scales. Finally, it outlines transformative implications for predicting pathogen evolution, antibiotic resistance, and guiding therapeutic design, establishing a framework for integrating evolutionary forecasting into biomedical research.

The Determinism Paradox: Reconciling Random Mutation with Predictable Molecular Evolution

Defining Evolutionary Predictability in a Molecular Context

Evolutionary biology has undergone a profound shift, moving from a field traditionally viewed as a historical science to one embracing predictive power. The once-dominant view, popularized by Stephen Jay Gould, held that the random, stochastic nature of evolution made predicting evolutionary trajectories near impossible [1]. However, the development of high-throughput sequencing and sophisticated data analysis technologies has challenged this paradigm, providing an abundance of molecular data that yields novel insights into evolutionary processes [1]. Evolutionary predictions are now increasingly used to develop fundamental knowledge of evolving systems and demonstrate evolutionary control, with critical applications in medicine, agriculture, and conservation biology [1].

This transformation frames a central question in modern molecular ecology: to what extent can we predict evolutionary outcomes? This guide examines evolutionary predictability through the lens of molecular processes, exploring the factors that enhance or diminish our forecasting capabilities across biological scales from single-nucleotide polymorphisms to complex phenotypic traits.

Theoretical Frameworks for Evolutionary Prediction

Foundational Theories and Their Predictive Implications

Two primary theoretical frameworks have shaped our understanding of molecular evolution, each offering distinct perspectives on predictability:

The Modern Synthesis: This framework integrates Darwinian natural selection with Mendelian inheritance, positing that genetic variation arises randomly but natural selection acts deterministically [1]. From this perspective, predictions are grounded in the principle that exposing bacteria to antibiotics will select for individuals harboring resistance mutations, ultimately producing populations dominated by resistant mutants [1]. This deterministic view of selection supports more predictable evolutionary outcomes.

Neutral Theory of Evolution: Proposed by Motoo Kimura, this controversial theory suggests that most genetic variation between and within species results from random accumulation of selectively neutral or nearly neutral mutations [1]. While acknowledging purifying selection (which eliminates deleterious mutations) and positive selection (which favors beneficial mutations), neutral theory assumes most genomes are well-adapted, making advantageous mutations rare [1]. This emphasis on stochastic processes constrains evolutionary predictability.

Modern evolutionary biology recognizes that natural systems often operate with complexity exceeding either theoretical extreme, incorporating elements of both deterministic selection and stochastic processes [1].

Repeatability as a Measure of Predictability

Evolutionary repeatability—the independent evolution of highly similar or identical genotypes or phenotypes—serves as a crucial indicator of evolutionary predictability [1]. Repeatability exists on a quantifiable continuum rather than a binary state, with convergent and parallel evolution representing one extreme end of this spectrum [1].

Table 1: Types of Repeated Evolution

| Type | Definition | Molecular Context |

|---|---|---|

| Parallel Evolution | Evolution of similar traits in independently evolving but related species or populations [1] | Similar genetic changes occurring in closely related lineages facing similar selection pressures |

| Convergent Evolution | Evolution of similar traits in independent species that do not share a recent common ancestor [1] | Different genetic changes producing similar phenotypic outcomes in distantly related lineages |

The extent of evolutionary repeatability provides insights into the deterministic nature of evolutionary processes, with higher repeatability suggesting greater predictability [1]. Understanding the factors influencing repeatability could ultimately enable more accurate evolutionary forecasts [1].

Molecular Evidence for Evolutionary Predictability

Empirical Evidence from Experimental Evolution

Contemporary research provides compelling evidence for evolutionary repeatability at molecular levels. Recent work on temperature adaptation in seed beetles (Callosobruchus maculatus) offers particularly insightful findings [2].

In an evolve-and-resequence experiment, researchers established replicate lines from three geographic populations and reared them at hot (35°C) or cold (23°C) temperatures, then tracked evolutionary trajectories at both phenotypic and genomic levels [2]. The experimental design allowed comparisons within and between genetic backgrounds to quantify repeatability.

Table 2: Phenotypic vs. Genomic Repeatability in Seed Beetle Thermal Adaptation

| Aspect | Hot Temperature (35°C) | Cold Temperature (23°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Rate | Higher (0.87 ± 0.14) [2] | Lower (0.5 ± 0.07) [2] |

| Phenotypic Parallelism | More parallel (39.32° ± 19.16°) [2] | Less parallel (67.42° ± 23.30°) [2] |

| Genomic Repeatability | Lower between backgrounds [2] | Higher between backgrounds [2] |

| Shared Genic Targets | 51 genes (more than expected by chance) [2] | 296 genes (more than expected by chance) [2] |

| Prediction Accuracy | Accurate within but not between backgrounds [2] | More consistent across genetic backgrounds [2] |

This research demonstrated that while phenotypic evolution was faster and more repeatable under hot temperatures, genomic-level adaptation was actually less repeatable across different genetic backgrounds [2]. This paradox suggests that the same strong selection pressures that increase phenotypic repeatability may simultaneously decrease genomic repeatability due to genetic redundancy and epistasis [2].

Microbial Systems as Models for Evolutionary Prediction

Microbial evolution provides another critical window into evolutionary predictability, with significant implications for human health [3]. The global antimicrobial resistance crisis represents a pressing example of microbial adaptation to selective pressures (antibiotic use), making understanding and predicting microbial evolutionary dynamics increasingly urgent [3].

Microbial systems offer particular advantages for studying evolutionary predictability:

- Rapid generation times enable observation of evolutionary processes in real-time

- Large population sizes facilitate statistical analysis of evolutionary trajectories

- Genomic tractability allows comprehensive molecular monitoring

- Controlled laboratory environments reduce confounding variables

Research in microbial evolution has revealed that predictions tend to be more precise on short timescales, where stochastic effects have less opportunity to divert evolutionary trajectories [1].

Methodologies for Studying Evolutionary Predictability

Experimental Evolution Protocols

The seed beetle thermal adaptation study [2] exemplifies a robust approach to quantifying evolutionary predictability:

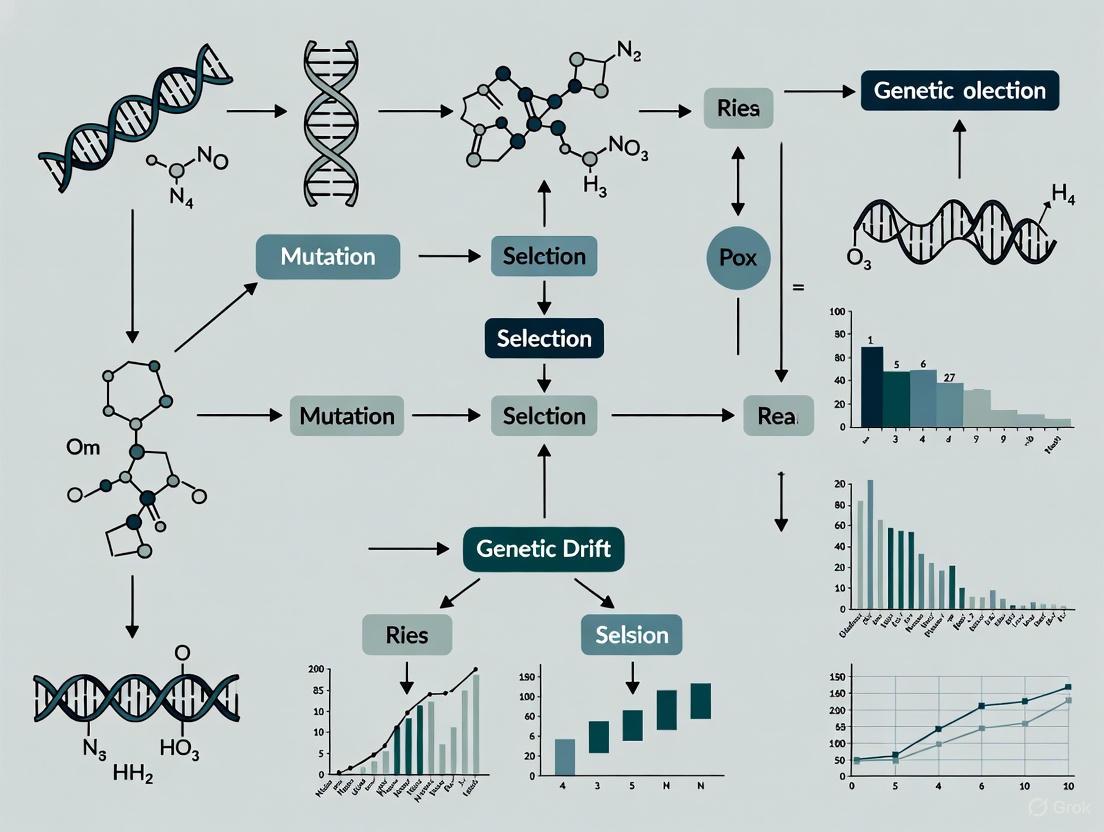

Figure 1: Experimental evolution workflow for assessing evolutionary repeatability across multiple genetic backgrounds under different selective environments.

Genomic Analysis Techniques

Table 3: Genomic Analysis Methods for Evolutionary Prediction

| Method | Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (pool-seq) | Tracking allele frequency changes across entire genomes in evolving populations [2] | Requires sufficient sequencing depth; effective population size estimates needed to distinguish selection from drift |

| Selection Coefficient Estimation | Quantifying strength of selection on specific alleles or genomic regions [2] | Must account for effective population size (Nₑ) which differs between selective environments |

| Candidate SNP Identification | Identifying putatively selected polymorphisms [2] | Categorization into synergistically pleiotropic, antagonistically pleiotropic, and private alleles reveals different evolutionary patterns |

| Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis | Identifying biological processes repeatedly targeted by selection [2] | Higher-level repeatability often observed even when individual SNPs show little repeatability |

| Jaccard Indices | Quantifying overlap of selected genes across populations and treatments [2] | Permutation tests determine whether observed overlap exceeds chance expectations |

Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Experiments

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Evolutionary Predictability Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Evolutionary Experiments |

|---|---|

| Callosobruchus maculatus (Seed Beetle) | Model organism for thermal adaptation studies; well-characterized biology and genome [2] |

| Multiple Genetic Backgrounds | Geographic populations with distinct evolutionary histories to test contingency [2] |

| Controlled Temperature Environments | Standardized selective environments (e.g., 23°C cold, 29°C ancestral, 35°C hot) [2] |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Platform | Monitoring allele frequency changes at genomic scale over evolutionary time [2] |

| Life-History Trait Assays | Quantifying phenotypic evolution (development time, weight, fecundity, metabolic rate) [2] |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Analyzing selection coefficients, effective population size, and parallelism statistics [2] |

Factors Influencing Evolutionary Repeatability and Prediction

Genetic and Environmental Determinants

Multiple factors interact to determine the degree of evolutionary repeatability observed in molecular contexts:

Strength of Selection: Theory suggests that environments imposing stronger selection are more likely to produce repeatable evolutionary outcomes [2]. The seed beetle experiment confirmed that hotter temperatures, which theoretically impose stronger selection due to thermodynamic constraints, produced faster and more parallel phenotypic evolution [2].

Genetic Background and Historical Contingency: Previous evolutionary history significantly influences subsequent adaptive trajectories. The seed beetle study found greater parallelism within genetic backgrounds than between them for both hot and cold temperatures, highlighting the role of historical contingency [2].

Genetic Redundity and Epistasis: Hot temperature adaptation in seed beetles showed lower genomic repeatability between backgrounds, potentially explained by increased importance of epistatic interactions [2]. This genetic redundancy means different genetic solutions can arrive at similar phenotypic outcomes.

Polygenic Architecture of Traits: When adaptation involves many loci of small effect, repeatability is more likely at the pathway level than at the level of individual nucleotides [2]. The seed beetle thermal adaptation was highly polygenic, involving thousands of candidate SNPs [2].

Figure 2: Key factors affecting evolutionary repeatability at phenotypic and genomic levels, showing how some factors differentially impact these two levels.

The Repeatability-Predictability Relationship

The relationship between repeatability and predictability forms the foundation for evolutionary forecasting:

Phenotypic vs. Genomic Predictability: The seed beetle experiment revealed a critical dissociation—while phenotypic evolution was more repeatable (and thus potentially more predictable) at hot temperatures, genomic evolution was less repeatable across genetic backgrounds [2]. This suggests that predictions of adaptation in key phenotypes from genomic data may become increasingly difficult as climates warm [2].

Timescale Dependence: Evolutionary predictions have been shown to be more precise on short timescales, where contingent factors have less opportunity to divert evolutionary trajectories [1]. Over longer timescales, stochastic processes accumulate, reducing predictability.

Level of Biological Organization: Predictability varies across biological scales. While individual nucleotide changes may be poorly predictable, pathway-level evolution shows greater repeatability [2]. Similarly, phenotypic outcomes often show greater predictability than their underlying molecular bases.

Applications and Future Directions

Practical Applications of Evolutionary Prediction

Accurate evolutionary forecasting has transformative potential across multiple fields:

Antimicrobial Resistance: Medicine would be significantly advanced by foreseeing which pathogens are most likely to evolve drug resistance [1]. Understanding the molecular pathways repeatedly involved in resistance evolution could inform drug development and treatment strategies.

Influenza Vaccine Development: Predictive models based on evolutionary theory aid vaccine development by predicting which influenza variant will dominate upcoming flu seasons [1].

Conservation Biology: Conservation efforts can be assisted by identifying which endangered species face the greatest extinction risk from climate change [1]. Genomic data may help predict adaptive potential in threatened populations.

Agricultural Management: Predicting evolutionary trajectories in crop pests and pathogens can inform sustainable agricultural practices and pesticide rotation strategies [1].

Emerging Research Frontiers

Several emerging research areas promise to enhance our predictive capabilities:

Integration of Microbial Evolutionary Dynamics: Research linking microbial evolution to community dynamics and ecosystem functioning represents a growing frontier [3]. This includes understanding how evolutionary dynamics in microbial communities impact human health, biogeochemical cycles, and antibiotic resistance spread [3].

Cross-Scale Predictive Models: Developing models that connect genomic changes to phenotypic outcomes across biological scales remains a fundamental challenge. The observed dissociation between phenotypic and genomic repeatability in seed beetles highlights the complexity of this endeavor [2].

Applied Evolutionary Prediction: Research is increasingly focusing on practical applications of evolutionary forecasting, including developing resilient biotechnological solutions and managing evolutionary processes in clinical and agricultural contexts [3].

As the field advances, integrating knowledge across biological scales—from molecular to ecological—will be essential for enhancing our ability to predict evolutionary outcomes. While significant challenges remain, particularly in reconciling genomic and phenotypic predictability, the growing evidence for repeatable evolutionary patterns offers promise for the future of evolutionary forecasting in molecular ecology and beyond.

The question of whether evolution is a predictable process or a contingent one, heavily dependent on chance historical events, represents a foundational debate in evolutionary biology. The late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould famously argued that the random, stochastic nature of evolution makes evolutionary processes fundamentally unpredictable, proposing that if one could "replay the tape of life," the outcomes would be vastly different each time [1] [4]. This perspective of historical contingency suggests that evolutionary outcomes are idiosyncratic products of a particular and unpredictable course of historical events, with long-term consequences that make evolution increasingly path-dependent over time [4]. Challenging this view are numerous documented cases of convergent and parallel evolution, where similar phenotypes or genotypes evolve independently in response to similar selection pressures, suggesting that natural selection can override historical contingencies to produce predictable outcomes [1] [5]. This debate has profound implications for molecular ecology and drug discovery, where understanding the predictability of evolutionary processes can inform strategies for anticipating pathogen resistance, identifying therapeutic targets, and developing novel treatments [6] [7].

Theoretical Frameworks: From Historical Contingency to Evolutionary Repeatability

Gould's Contingency Thesis

Stephen Jay Gould's argument for historical contingency rests on the premise that evolution is dominated by stochastic events such as mass extinctions, genetic drift, and unique mutations, creating an inherently unpredictable process. From this perspective, the diversity of life reflects a series of historical accidents rather than deterministic adaptation. Gould proposed that the extraordinary number of potential evolutionary pathways, combined with the sensitivity of long-term outcomes to initial conditions, makes large-scale evolutionary patterns essentially unrepeatable [1] [4]. This view suggests that as lineages diverge over evolutionary time, the likelihood of them evolving similar adaptations decreases substantially due to accumulating genetic and developmental differences that constrain future evolutionary possibilities [5].

Evidence for Convergent and Parallel Evolution

In contrast to Gould's contingency thesis, numerous studies have documented remarkable cases of convergent evolution (similar traits evolving independently in distantly related species) and parallel evolution (similar traits evolving independently in closely related species) across the tree of life [1]. These repeated evolutionary patterns suggest that natural selection can produce predictable outcomes when organisms face similar environmental challenges. Classic examples include the independent evolution of wings in birds and bats, camera-type eyes in vertebrates and cephalopods, and similar morphological adaptations in geographically separated species occupying comparable ecological niches [5]. The repeated evolution of similar adaptations implies that there may be a limited number of optimal solutions to particular functional problems, "stacking the deck" in favor of certain evolutionary outcomes regardless of historical starting points [5].

Table 1: Types of Repeated Evolution and Their Characteristics

| Type | Definition | Genetic Basis | Phylogenetic Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel Evolution | Independent evolution of similar traits in related species | Same genetic mechanisms | More common among closely related taxa |

| Convergent Evolution | Independent evolution of similar traits in distantly related species | Different genetic mechanisms | Occurs across diverse phylogenetic distances |

| Functionally Redundant Evolution | Evolution of different traits serving the same function | Variable genetic mechanisms | Less contingent on evolutionary history |

The Modern Synthesis and Neutral Theory

The debate between contingency and predictability also reflects broader theoretical tensions in evolutionary biology. The Modern Synthesis emphasizes natural selection as the primary driver of adaptive evolution, with genetic variation arising randomly and mutations being selected based on their fitness effects [1]. This framework naturally accommodates repeated evolution when similar selection pressures operate on independent lineages. In contrast, the Neutral Theory proposed by Motoo Kimura emphasizes that most evolutionary change at the molecular level results from the random fixation of selectively neutral mutations through genetic drift [1]. This perspective highlights the substantial role of chance in evolution, particularly at the molecular level, which would support Gould's contingency argument.

Quantitative Evidence: Meta-Analyses of Evolutionary Repeatability

Recent meta-analyses of published examples of repeated evolution provide quantitative insights into the predictability of evolutionary processes and the factors that influence evolutionary repeatability.

The Impact of Phylogenetic Distance

A comprehensive survey of reported cases of repeated evolution in animals revealed that the likelihood of repeated evolution is strongly influenced by the phylogenetic distance between taxa [5]. Overall, reports of repeated evolution decreased progressively as the phylogenetic separation between taxa increased. However, this pattern varied substantially depending on the type of repeated evolution and the phenotypic characteristics under investigation. The survey found that 53% of reported cases involved morphological adaptations, while behavior and physiology accounted for 22% and 18% respectively [5].

Table 2: Factors Influencing Evolutionary Repeatability Based on Meta-Analysis

| Factor | Effect on Repeatability | Evidence Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Distance | Strong negative correlation with morphological repeatability | High (based on quantitative analysis) |

| Type of Trait | Morphology more contingent than behavior or physiology | Moderate (differential patterns observed) |

| Genetic Mechanism | Parallel evolution (same genes) more contingent than convergent evolution (different genes) | Moderate (trend observed) |

| Functional Redundancy | Less contingent than other forms of adaptation | Moderate (multiple examples) |

| Selection Pressure | Habitat similarity most common factor (48% of cases) | High (based on frequency analysis) |

Differential Repeatability Across Biological Domains

The meta-analysis revealed important differences in how contingent various forms of adaptation appear to be. The repeated evolution of similar morphological characteristics was heavily skewed toward closely related taxa, supporting Gould's view that historical constraints play a significant role in morphological evolution [5]. In contrast, the repeated evolution of behavioral and physiological adaptations appeared less contingent on evolutionary history, occurring across broader phylogenetic distances. This suggests that different aspects of phenotype may be more or less "evolvable," with behavior and physiology potentially having more potential evolutionary pathways than morphology [5]. Additionally, functionally redundant characteristics—alternative phenotypes that achieve the same functional outcome—appeared less contingent, being frequently reported among both closely and distantly related taxa [5].

Experimental Evolution: Replaying the Tape of Life

Experimental Evolution Methodologies

Experimental evolution has emerged as a powerful approach for directly testing evolutionary predictability by "replaying the tape of life" under controlled laboratory conditions [7]. This methodology typically involves establishing replicate populations of model organisms (e.g., bacteria, yeast, or other microorganisms) and exposing them to defined selection pressures over multiple generations. Key methodological approaches include:

- Serial batch transfer: Populations are periodically transferred to fresh media, allowing for continuous evolution under defined conditions [7].

- Chemostat cultures: Continuous culture systems maintain constant environmental conditions while allowing for evolutionary dynamics [7].

- Fluctuating environments: Variable conditions can be introduced to mimic natural environmental variation [7].

- In vivo models: Experimental evolution within host organisms (e.g., mouse models) provides insights into host-pathogen coevolution [7].

Fitness and evolutionary changes are tracked using various metrics, including:

- Growth rates and minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for antimicrobial resistance [7]

- Competitive fitness assays between evolved and ancestral strains [7]

- Genetic analyses including whole-genome sequencing to identify mutations [7]

- Molecular barcoding for high-resolution tracking of subpopulation dynamics [7]

Experimental Evolution Workflow: This diagram illustrates the general approach for testing evolutionary predictability through replicated experimental evolution under defined selection pressures.

Key Findings from Experimental Evolution Studies

Experimental evolution studies have provided nuanced insights into the predictability of evolution:

- Pathogenic fungi evolved resistance to antifungal drugs through both predictable and contingent pathways, with some mutations occurring repeatedly across replicates while others were lineage-specific [7].

- BCL-2 family proteins evolved novel protein-protein interaction specificities through largely unpredictable trajectories, with outcomes strongly dependent on historical starting points [4].

- Collateral sensitivity patterns, where resistance to one drug increases sensitivity to another, have shown some predictability that could inform combination therapy approaches [7].

- Fitness trade-offs associated with resistance mutations often follow predictable patterns, but the specific genetic solutions vary considerably [7].

The experimental evolution of BCL-2 family proteins provides particularly compelling evidence for historical contingency. When researchers used ancestral protein reconstruction to evolve BCL-2 proteins from different historical starting points toward the same functional outcome, they found that evolutionary trajectories yielded "virtually no common mutations," even under strong and identical selection pressures [4]. This suggests that contingency generated over long historical timescales can steadily erase necessity, making evolutionary outcomes increasingly unpredictable as phylogenetic distance increases.

Molecular Evidence: From Genotype to Phenotype

Genetic Constraints on Evolutionary Repeatability

At the molecular level, the debate between contingency and predictability centers on the availability and accessibility of genetic variation that can produce adaptive phenotypes. Studies of parallel and convergent evolution at the genetic level have revealed several key patterns:

- Close relatives are more likely to evolve similar adaptations through identical genetic mechanisms (parallel evolution) due to shared genetic and developmental backgrounds [5].

- Distant relatives more often evolve similar adaptations through different genetic mechanisms (convergent evolution) when different mutations affect the same physiological pathways or protein functions [5].

- Historical mutations can alter the set of accessible future mutations, creating path dependence in protein evolution [4].

- Pleiotropic constraints, where mutations affect multiple functions, can limit evolutionary pathways, making some adaptations less accessible in certain genetic backgrounds [4].

Protein Evolution and Historical Contingency

Research on the evolution of BCL-2 family proteins demonstrated that historical contingency can profoundly shape molecular evolutionary trajectories. When ancestral BCL-2 proteins were evolved to acquire new protein-protein interaction specificities, researchers found that "contingency generated over long historical timescales steadily erased necessity" [4]. Specifically:

- Trajectories launched from the same ancestral protein produced outcomes with some shared mutations, indicating a degree of predictability.

- Trajectories launched from different ancestral proteins showed virtually no common mutations, despite selection for the same functional outcome.

- The effect of historical substitutions was to change the sets of mutations that could productively alter function at each historical point, making evolution increasingly path-dependent over time.

These findings suggest that the specific sequences of BCL-2 proteins—and likely other proteins as well—are "idiosyncratic products of a particular and unpredictable course of historical events" [4].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Molecular Ecology

Evolutionary Principles in Drug Target Identification

The predictability of evolutionary processes has direct applications in drug discovery, particularly in identifying promising drug targets. Evolutionary information has been used to develop the Evolution-Strengthened Knowledge Graph (ESKG), which integrates evolutionary data such as Ohnologs (genes generated in whole-genome duplication events) and evolutionary stages of genes with various biological relationships to predict causative disease genes and drug targets [6]. This approach recognizes that "existing successful targets share some critical evolutionary hallmarks," and that "evolutionary information can facilitate the target prediction" [6]. The ESKG contains more than 4 million triplets and 16 kinds of relations, enabling machine learning models like GraphEvo to predict both the targetability and druggability of genes [6].

Table 3: Evolutionary Concepts in Drug Discovery Applications

| Evolutionary Concept | Drug Discovery Application | Example/Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Hallmarks | Predicting successful drug targets | Ohnologs and specific evolutionary stages are enriched among successful targets [6] |

| Evolutionary Conservation | Identifying functionally important genes | Ancient, conserved genes often represent core biological processes |

| Convergent Evolution | Anticipating resistance mechanisms | Similar resistance mutations emerge independently [7] |

| Experimental Evolution | Screening for resistance development | Preemptive identification of resistance mutations [7] |

| Evolution-Strengthened Knowledge Graphs | Predicting target-disease associations | Integration of evolutionary data with biological networks [6] |

Anticipating and Managing Drug Resistance

Understanding evolutionary predictability is crucial for anticipating and managing drug resistance in pathogens. Experimental evolution studies with pathogenic fungi have revealed both predictable and contingent aspects of resistance evolution:

- Predictable patterns include frequent mutations in specific target genes (e.g., ERG genes for azole resistance in fungi) and common fitness trade-offs associated with resistance [7].

- Contingent patterns emerge in the specific mutation spectra and evolutionary pathways taken by different lineages, influenced by initial genetic background and historical accidents [7].

- Collateral sensitivity patterns, where resistance to one drug increases sensitivity to another, show some predictability that can be exploited in designing combination therapies [7].

- Agricultural practices can drive predictable cross-resistance to clinical antifungals, highlighting the importance of integrated management approaches [7].

Knowledge Graphs and Predictive Models in Drug Discovery

The integration of evolutionary principles into computational approaches represents a promising frontier in drug discovery. The Evolution-Strengthened Knowledge Graph (ESKG) exemplifies this approach, combining common biological data (e.g., gene-disease associations, drug-target interactions) with evolutionary information to create a comprehensive resource for predicting promising drug targets [6]. Machine learning models like GraphEvo, built on ESKG, can effectively predict both the targetability and druggability of genes, potentially accelerating early-stage drug discovery [6]. Similarly, approaches like MSPEDTI combine protein evolutionary information (via Position-Specific Scoring Matrices) with drug structural information to predict drug-target interactions, achieving prediction accuracies of 86-94% across different target classes [8].

Evolution-Informed Drug Discovery: This diagram shows how evolutionary observations, encompassing both contingent factors and predictable patterns, are integrated into computational frameworks for drug discovery applications.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Evolutionary Predictability Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) | Protein evolutionary analysis | Quantifies evolutionary conservation and variation in protein sequences | PSI-BLAST against SwissProt database [8] |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Drug structure characterization | Encodes molecular structures as binary vectors for computational analysis | PubChem database [8] |

| Fluorescent Protein Markers | Competitive fitness assays | Enables tracking of subpopulation dynamics in experimental evolution | GFP, RFP variants [7] |

| Antifungal/Antibiotic Agents | Experimental evolution studies | Applies selective pressure for resistance evolution | Clinical antifungals/antibiotics [7] |

| Ancestral Protein Reconstruction | Historical contingency studies | Recreates ancient proteins to replay evolution from different starting points | Phylogenetic analysis and gene synthesis [4] |

| Drug-Target Interaction Databases | Predictive model training | Provides gold-standard data for machine learning approaches | BRENDA, KEGG, DrugBank [8] |

| Knowledge Graphs | Data integration and prediction | Integrates diverse biological and evolutionary data for relationship mining | ESKG with >4 million triplets [6] |

The debate between Gould's contingency and convergent evolution evidence does not yield a simple verdict. Instead, empirical evidence reveals a nuanced reality where evolutionary outcomes display both predictable and contingent characteristics. The degree of evolutionary repeatability appears to depend on multiple factors, including:

- Phylogenetic distance: Closely related taxa are more likely to evolve similar adaptations through parallel genetic mechanisms [5].

- Type of trait: Behavior and physiology show greater evolutionary repeatability than morphology across distant taxa [5].

- Functional constraints: When there are limited solutions to functional challenges, convergent evolution is more likely [5].

- Historical constraints: Accumulated mutations over time create path dependence, making evolution increasingly contingent [4].

For molecular ecology and drug discovery, these insights suggest a dual approach: leveraging predictable evolutionary patterns when they exist (e.g., common resistance mutations, evolutionarily conserved target features) while acknowledging and accounting for contingent factors that limit predictability. The integration of evolutionary principles into computational frameworks like knowledge graphs and machine learning models represents a promising approach to navigating this complexity, potentially enhancing our ability to predict evolutionary outcomes and apply these predictions to practical challenges in medicine and biotechnology.

Future research directions should include more comprehensive experimental evolution studies across diverse biological systems, enhanced integration of evolutionary and ecological perspectives, and the development of more sophisticated computational models that can account for both predictable and contingent aspects of evolution. As these efforts advance, they will continue to refine our understanding of when and how we can predict the evolutionary processes that shape the biological world.

The question of whether evolutionary change is predictable sits at the heart of molecular ecology research, creating a fundamental tension between stochastic genetic forces and deterministic phenotypic outcomes. While biological entities operate within physical and chemical laws that suggest determinism, evolutionary processes introduce elements of randomness through mutation, genetic drift, and environmental stochasticity [9]. This framework creates a central question for researchers: to what extent do the deterministic elements of natural selection make evolutionary change predictable, particularly when considering the emergent properties of biological systems [9]?

The resolution to this apparent contradiction lies in understanding that evolutionary predictability exists on a spectrum, influenced by factors including population size, strength of selection, genetic architecture, and environmental stability. Advances in genomic technologies, quantitative models, and long-term empirical studies are now providing unprecedented insights into where specific biological systems fall on this spectrum. This analytical framework is particularly relevant for drug development professionals seeking to anticipate pathogen evolution and resistance mechanisms, where accurate predictions can inform therapeutic design and intervention strategies.

Theoretical Foundations: Random Processes and Deterministic Forces

The Stochastic Elements of Evolution

Genetic randomness originates from several fundamental biological processes that introduce inherent unpredictability into evolutionary systems:

- Mutation: The random appearance of novel genetic variants provides the raw material for evolution, with mutation rates varying across genomes and influenced by environmental factors [10]. These random biochemical events create genetic diversity independently of an organism's functional needs.

- Genetic Drift: The random sampling of alleles across generations becomes particularly influential in small populations, where it can lead to the fixation of deleterious alleles or loss of beneficial ones through a process known as drift load [11]. This effect is quantified through the concept of effective population size (Nₑ), which is often much smaller than census population size [11].

- Recombination: The random reassortment of genetic material during meiosis creates novel allele combinations, with the rate of recombination influenced by chromosomal position and specific hotspot motifs [11].

- Demographic Stochasticity: Random fluctuations in population size due to variations in individual birth, death, and migration rates can significantly impact evolutionary trajectories, especially in small populations targeted for conservation [11].

The Deterministic Forces in Evolution

Counterbalancing these stochastic elements, several deterministic forces impart predictable directionality to evolutionary change:

- Natural Selection: This goal-directed process systematically favors phenotypes with greater fitness in a given environment, potentially leading to convergent evolutionary solutions [9]. The strength of selection determines the degree to which it can overcome random genetic drift.

- Biophysical Constraints: Physical and chemical laws impose absolute limits on possible biological forms and functions [10]. For proteins, folding stability represents a key biophysical constraint that shapes evolutionary outcomes [12].

- Demo-Genetic Feedback: The reciprocal interaction between demographic processes and genetic composition creates self-reinforcing cycles that can drive populations toward predictable states [11]. This feedback can trap small populations in an "extinction vortex" where declining numbers exacerbate genetic erosion.

- Antagonistic Pleiotropy: When mutations have opposing fitness effects in different environments or at different times, this can lead to adaptive tracking where populations continuously adapt to changing conditions, creating patterns that mimic neutrality at the molecular level [13].

Current Research Approaches and Quantitative Frameworks

Predictive Modeling in Population Genetics

Contemporary research employs sophisticated modeling approaches to quantify the balance between randomness and determinism:

Table 1: Quantitative Frameworks for Predicting Evolutionary Outcomes

| Framework | Key Inputs | Predictive Outputs | Applicable Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype Design Space (PDS) [10] | Kinetic parameters of molecular processes, environmental variables | Full repertoire of possible biochemical phenotypes, transition probabilities between phenotypes | Microbial systems, molecular pathway analysis |

| Birth-Death Population Models with SCS [12] | Protein folding stability constraints, population parameters | Forecasted protein sequences and stability changes under selection | Viral protein evolution, antimicrobial resistance |

| Demo-Genetic Models [11] | Census population size, genetic load, migration rates | Extinction risk, response to genetic rescue interventions | Conservation biology, threatened species management |

| Polygenic Score Prediction Intervals [14] | GWAS summary statistics, individual genotypes | Calibrated prediction intervals for complex traits, identification of high-risk individuals | Human complex diseases, plant and animal breeding |

Methodological Protocols for Forecasting Evolution

Protocol 1: Forecasting Protein Evolution Using Structurally Constrained Models

This protocol integrates birth-death population genetics with structural constraints to forecast protein evolutionary trajectories [12]:

- Initialize Population: Begin with a founding population of sequences, typically derived from natural isolates or engineered variants.

- Parameterize Fitness Landscape: Define fitness based on protein folding stability (ΔG) using structurally constrained substitution models that incorporate biophysical principles.

- Simulate Birth-Death Process: At each generation, compute birth and death rates for each variant based on its fitness, with high-fitness variants producing more offspring.

- Introduce Mutations: Incorporate novel mutations according to empirically determined mutation rates, with structural constraints influencing acceptance probabilities.

- Track Evolutionary Trajectories: Monitor sequence changes, population diversity, and fitness changes over evolutionary time.

- Validate Predictions: Compare forecasted sequences with subsequently observed natural variants to assess predictive accuracy.

Protocol 2: Constructing Calibrated Prediction Intervals for Polygenic Scores

The PredInterval method provides robust uncertainty quantification for polygenic risk scores [14]:

- Generate PGS Point Estimates: Calculate polygenic scores using any preferred method (e.g., LDpred, PRS-CS, DBSLMM).

- Compute Phenotypic Residuals: Calculate the difference between observed and predicted phenotypic values in training data.

- Estimate Residual Quantiles: Through cross-validation, determine the distribution of phenotypic residuals across genetic backgrounds.

- Construct Prediction Intervals: For each new individual, calculate the (1-α)% prediction interval as PGS ± Q(1-α/2), where Q is the appropriate quantile of the residual distribution.

- Assess Calibration: Verify that the empirical coverage rate matches the nominal coverage rate across diverse genetic architectures.

Quantitative Evidence: Empirical Data on Predictability

Performance Benchmarks for Predictive Methods

Table 2: Empirical Performance of Evolutionary Prediction Methods

| Method/System | Trait/Outcome | Performance Metric | Result | Implications for Determinism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PredInterval [14] | 17 complex traits | Prediction coverage at 95% target | 96.0% (quantitative), 96.7% (binary) | High predictability for polygenic traits when uncertainty is properly quantified |

| BLUP Analytical Form [14] | Complex traits | Prediction coverage at 95% target | 91.0% (quantitative), 83.4% (binary) | Underestimation of uncertainty reduces apparent predictability |

| ProteinEvolver2 [12] | Viral protein stability | Prediction error for ΔG | Acceptable errors for stability, larger for sequences | Structural constraints enable stability prediction despite sequence variability |

| Long-term studies [15] | Speciation events | Documentation of complete speciation process | Observed in Darwin's finches over decades | Deterministic selection can overcome random initial conditions |

Temporal Scales of Predictability

Long-term evolutionary studies provide unique insights into how predictability changes across timescales [15]:

Evidence from long-term evolution experiments reveals that while short-term adaptation is often highly predictable from a knowledge of selection pressures and genetic variation, long-term evolutionary trajectories become increasingly influenced by historical contingencies such as rare mutations and chance environmental events [15]. The LTEE with Escherichia coli has demonstrated that while fitness trajectories are remarkably consistent across replicates in the short term, genomic solutions show considerable divergence over thousands of generations [15].

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Evolutionary Predictability Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | SLiM [11], ProteinEvolver2 [12], Design Space Toolbox [10] | Forward simulation of evolutionary processes | Scalability to large populations, integration of realistic genetic architectures |

| Genomic Data Types | Genome-wide association studies, whole-genome sequencing, epigenetic markers [16] | Mapping genotype-phenotype relationships | Resolution for detecting rare variants, functional validation requirements |

| Experimental Systems | Long-term evolution experiments [15], microbial evolution, synthetic communities [3] | Real-time observation of evolutionary dynamics | Generation time, scalability, relevance to natural systems |

| Analytical Frameworks | PredInterval [14], birth-death models [12], demo-genetic feedback models [11] | Quantifying uncertainty and forecasting changes | Computational demands, parameter estimation, model validation |

Conceptual Framework: Mapping Genotype to Phenotype

The challenge of predicting evolutionary outcomes fundamentally depends on the mapping between genotype and phenotype, which involves multiple mechanistic steps [10]:

The Phenotype Design Space framework addresses the second mapping in this cascade by providing a mathematically rigorous definition of phenotype based on biochemical kinetics, enumerating the full phenotypic repertoire available to a biological system, and functionally characterizing each phenotype independent of its context-dependent selection [10]. This approach enables researchers to determine the distribution of phenotype diversity generated by mutation and available for selection—a longstanding challenge in evolutionary theory.

Applications and Implications for Molecular Ecology and Drug Development

Practical Applications in Disease Research

The tension between genetic randomness and phenotypic determinism has profound implications for drug development:

- Antimicrobial Resistance: Forecasting evolutionary trajectories of pathogens can inform the design of antibiotic combination therapies that minimize resistance emergence [3]. Models incorporating protein stability constraints show promise in predicting which resistance mutations are likely to arise [12].

- Complex Disease Risk: Calibrated prediction intervals for polygenic scores enable more accurate identification of high-risk individuals for preventive interventions, with PredInterval improving identification rates by 8.7-830.4% compared to existing approaches [14].

- Vaccine Design: Forecasting protein evolution in rapidly evolving viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2 can guide selection of vaccine strains that anticipate future circulating variants [12].

Conservation Implications

Demo-genetic models inform conservation strategies by quantifying how genetic rescue interventions can counteract the negative effects of genetic drift and inbreeding in small populations [11]. These models reveal that the success of genetic rescue depends not only on genetic composition but also on emergent outcomes of interacting demographic processes and stochastic events.

The apparent tension between genetic randomness and phenotypic determinism reflects complementary rather than contradictory evolutionary forces. Random processes generate the variation upon which deterministic selection acts, with the balance between these forces determining the predictability of evolutionary outcomes. Current research demonstrates that evolutionary trajectories are increasingly predictable when we account for biophysical constraints, quantify uncertainty appropriately, and integrate across biological hierarchies from molecules to populations.

For molecular ecology research and drug development, this emerging predictive capacity offers the potential to anticipate evolutionary responses to environmental change, design more durable therapeutic interventions, and develop effective conservation strategies. The key frontier lies in developing integrated models that simultaneously capture stochastic processes while respecting the deterministic constraints that channel evolutionary outcomes into predictable pathways.

A longstanding goal of evolutionary biology is to understand the relationship between genotype, phenotype, and fitness, and its consequences for adaptation and speciation [17]. The theory of fitness landscapes provides a powerful conceptual and mathematical framework for this endeavor by modeling how genotypes or phenotypes map to reproductive success [17]. In molecular ecology research, this framework is increasingly critical for transforming evolution from a historical science into a predictive one [1]. While Stephen Jay Gould famously argued that the random, stochastic nature of evolution made evolutionary processes inherently unpredictable, recent advances in high-throughput sequencing and data analysis have challenged this view, revealing compelling evidence of evolutionary repeatability across diverse systems [1]. The core principles of natural selection, genetic constraints, and the topography of fitness landscapes collectively determine the degree to which evolutionary trajectories can be forecast, with significant implications for addressing pressing challenges in drug development, antimicrobial resistance, and pathogen evolution [18] [1].

Theoretical Foundations

Natural Selection and Neutral Evolution

Evolutionary outcomes emerge from the interplay of deterministic and stochastic forces. Natural selection acts as a primary deterministic force, favouring beneficial mutations that enhance survival and reproduction [1]. In the context of predictability, a selectionist viewpoint suggests that similar environmental pressures should drive populations toward similar adaptive solutions, particularly when starting from similar genetic backgrounds [1].

Conversely, the neutral theory of evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura, emphasizes stochasticity. It posits that most genetic variation within and between species arises from the random accumulation of selectively neutral mutations through genetic drift rather than natural selection [1]. According to this view, the rate of molecular evolution is determined primarily by mutation rate and population size, with Darwinian selection playing a minimal role [1].

In natural systems, the reality is more complex than either extreme suggests. Environmental influences and historical contingencies create a complex evolutionary landscape where both selection and drift operate simultaneously [1]. The predictability of evolution is therefore not absolute but exists on a quantifiable scale, influenced by the relative strengths of these forces [9].

Genetic Constraints and Epistasis

Genetic constraints represent limitations on evolutionary paths imposed by genetic architecture. A central concept is epistasis—the phenomenon where the fitness effect of a mutation depends on the genetic background in which it occurs [17]. From a fitness landscape perspective, epistasis introduces nonlinearity into the genotype-phenotype-fitness mapping function [17].

Epistasis manifests in several forms that influence evolutionary predictability:

- Reciprocal sign epistasis: Occurs when the sign of a mutation's fitness effect (beneficial or deleterious) reverses depending on genetic background. This interaction can create fitness peaks and valleys, potentially trapping populations on local optima rather than global fitness peaks [17].

- Diminishing-returns epistasis: A global pattern where the beneficial effect of a mutation tends to be smaller in fitter genetic backgrounds. This pattern has been observed across diverse organisms and reduces the number of accessible evolutionary paths [18].

The strength of epistatic interactions varies substantially across biological systems, influenced by factors including the fitness effects of individual mutations, whether mutations occur in the same or different genes, and environmental conditions [18].

Fitness Landscape Theory

Sewall Wright introduced the fitness landscape concept as a visual metaphor for evolution [18]. In this framework, genotypes are represented in a multi-dimensional space, with fitness as the vertical dimension. Evolution can be envisioned as a population moving across this landscape toward fitness peaks.

The topography of fitness landscapes—their ruggedness or smoothness—profoundly affects evolutionary dynamics and predictability:

- Smooth landscapes with single peaks facilitate predictable evolutionary trajectories toward the global optimum.

- Rugged landscapes with multiple peaks, separated by valleys of lower fitness, reduce predictability as populations may become trapped on different local optima [18].

Analyses of empirical fitness landscapes reveal they are generally rugged, though the degree of ruggedness varies substantially [18]. This variation depends on factors including the biological system, environmental conditions, and the mutations under consideration [18].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Fitness Landscape Theory

| Concept | Description | Impact on Predictability |

|---|---|---|

| Ruggedness | Presence of multiple fitness peaks and valleys due to epistasis | Decreases predictability; populations may become trapped on different local optima |

| Accessibility | Ease with which evolutionary paths can be traversed | Determines which mutational pathways are likely to be used |

| Neutrality | Presence of mutations with identical fitness effects | Increases exploration of genotype space through neutral drift |

| Epistasis | Dependence of mutation effects on genetic background | Creates nonlinearities that constrain or redirect evolutionary paths |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Characterizing Fitness Landscapes

Empirical characterization of fitness landscapes involves systematically measuring fitness effects of mutations and their combinations. Recent methodological advances have dramatically increased the scale of these efforts:

Deep Mutational Scanning: This approach involves creating comprehensive mutant libraries and measuring fitness effects through bulk competitions using deep sequencing [18]. This enables analyses of landscapes involving thousands of genotypes, providing high-resolution maps of fitness effects [18].

Experimental Evolution: This method involves tracking genetic and phenotypic changes in populations over time in controlled laboratory environments. Combined with whole-genome sequencing, it allows researchers to observe evolutionary trajectories directly and test predictions based on fitness landscape models [1].

Critical Experimental Design Considerations

Proper experimental design is paramount in molecular ecology research to ensure the reliability and interpretability of results. Several key considerations include:

Randomization and Balancing: Properly designed (randomized and/or balanced) experiments are standard in ecological research but are often overlooked in laboratory processing of samples [19]. Without randomization during laboratory procedures (e.g., DNA extraction, PCR), unexpected laboratory events (e.g., equipment failure, reagent variability) can systematically bias results and confound interpretations [19]. Molecular ecology studies should report detailed designs of sample processing to ensure safeguards against such biases [19].

Batch Effects: Similar to challenges in early genome-wide association studies, molecular ecology experiments are vulnerable to batch effects where technical artifacts rather than biological factors create spurious patterns [19]. These can be mitigated through randomized sample processing order and balanced experimental designs across batches [19].

Controls: Appropriate controls are essential, including negative controls (e.g., dH₂O instead of DNA template in PCR) and positive controls, which should be randomly distributed within processing batches [19].

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Methodologies in Fitness Landscape Research

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning | Creates mutant libraries; uses high-throughput sequencing to measure fitness | Mapping fitness effects of mutations across genes; identifying epistatic interactions | Thousands of genotypes |

| Experimental Evolution | Tracks evolving populations over time in controlled environments; uses whole-genome sequencing | Observing real-time evolutionary trajectories; testing predictability | Dozens to hundreds of generations |

| Barcoded Lineage Tracking | Uses unique genetic barcodes to follow lineages | Measuring lineage fitness in competition experiments | Millions of lineages |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fitness Landscape Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin Soil, MoBio PowerSoil) | Isolation of high-quality DNA from environmental or experimental samples | Extracting extracellular DNA from sediment cores in molecular ecology studies [19] |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Reagents | Amplification of specific DNA sequences | Preparing taxonomically informative marker gene fragments for metabarcoding [19] |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Determining genetic sequences of multiple samples in parallel | Genotyping evolved populations; sequencing mutant libraries [18] |

| Environmental DNA (eDNA) Preservation Solutions | Stabilizing DNA from environmental samples | Preserving community DNA from sediment or water samples for temporal studies [19] |

Quantitative Patterns in Empirical Fitness Landscapes

Empirical studies have revealed consistent quantitative patterns in fitness landscapes across biological systems:

Distribution of Fitness Effects: The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations is typically characterized by a large proportion of deleterious mutations, a small proportion of beneficial mutations, and many mutations of small effect [17].

Trajectory Entropy: This measures the uncertainty in evolutionary paths. Landscapes with high trajectory entropy have many equally likely evolutionary paths, reducing predictability, while low entropy landscapes have constrained paths that enhance predictability [18].

Pervasiveness of Epistasis: Empirical studies consistently detect widespread epistatic interactions, though their strength varies. For example, studies of TEM-1 β-lactamase revealed strong epistasis among just four mutations [18], while other systems show more moderate epistatic effects.

Table 4: Key Quantitative Findings from Empirical Fitness Landscape Studies

| System | Number of Mutations Studied | Strength of Epistasis | Impact on Evolutionary Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEM-1 β-lactamase [18] | 4 | Strong | Constrained evolutionary paths to antibiotic resistance |

| E. coli experimental evolution [18] | Multiple | Variable across environments | Altered relationship between mutation frequency and fitness |

| Hsp90 [18] | Multiple | Environment-dependent | Synonymous mutations impacted fitness landscape topography |

| Tobacco etch potyvirus [18] | Multiple | Strong | Deviations from expected evolutionary paths toward peaks |

Visualization of Fitness Landscape Concepts

Applications and Future Directions

The integration of fitness landscape theory with molecular ecology holds significant promise for practical applications. In public health, fitness landscape models have shown utility in predicting influenza evolution for vaccine development [18] [1]. In antimicrobial resistance, understanding the topographic constraints on resistance evolution can inform treatment strategies and drug development [1]. In conservation biology, predictive models based on evolutionary principles can identify endangered species at greatest risk of extinction [1].

Future progress will require:

- Integration of multi-scale data combining molecular, ecological, and environmental information

- Development of dynamic landscape models that account for changing environments and ecological interactions

- Advanced statistical frameworks for characterizing high-dimensional fitness landscapes from experimental data

- Cross-system comparative analyses to identify general principles versus system-specific peculiarities

As empirical data continue to accumulate and modeling frameworks become more sophisticated, fitness landscape theory offers a powerful paradigm for advancing from retrospective explanations to prospective predictions in molecular evolution [17] [18] [1].

In molecular ecology and evolutionary biology, the repeated evolution of similar traits presents a fundamental question: to what extent is evolution predictable? Convergent and parallel evolution represent two points on a spectrum of evolutionary repeatability, providing a powerful framework for investigating the deterministic forces shaping biological diversity. While often used interchangeably, these phenomena are distinguished by the starting points of the lineages in question. Parallel evolution occurs when independently evolving lineages share a recent common ancestor and utilize similar genetic solutions to adapt to comparable environmental challenges [20]. In contrast, convergent evolution describes the emergence of similar traits in distantly related lineages that have independently evolved similar genetic or phenotypic solutions [21].

At the molecular level, these patterns offer critical insights into the constraints and opportunities that dictate how organisms adapt. When the same nucleotide substitutions, gene expression changes, or structural genomic variations recur independently in response to similar selective pressures, they reveal the fundamental predictability of evolutionary processes. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence and methodologies for studying molecular convergence and parallelism, framing these phenomena within the broader context of evolutionary predictability in molecular ecology research.

Empirical Evidence Across Biological Systems

Quantitative Patterns of Molecular Parallelism

Table 1: Documented Patterns of Parallel Molecular Evolution Across Study Systems

| Study System | Generations/Time | Parallelism Level | Key Molecular Changes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila populations | 85-161 generations | High parallelism in gene expression between populations; reduces between species | 366-2,251 genes with significant expression changes; GO term enrichment | [21] |

| Eucalyptus species | Natural populations | 91% divergent evolution; 50% parallel evolution in adaptive homologous genes | Antagonistic regulation of homologous genes; heat shock protein expression | [22] |

| Laboratory yeast (S. cerevisiae) | ~10,000 generations | Widespread genetic parallelism; declining adaptability over time | Steady accumulation of mutations; historical contingency | [23] |

| Annual killifishes | Natural evolution | Convergent miRNA regulation in independent clades | miR-430 family dysregulation; 3p/5p form switching | [24] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Patterns

The empirical evidence reveals that molecular parallelism and convergence occur across multiple biological levels and systems. In transcriptomic studies of Eucalyptus species, while divergent evolution dominated (91% of significant genes), homologous genes showed parallel adaptive responses in 50% of cases, suggesting that even closely related species may develop different molecular solutions to similar environmental challenges [22]. Notably, plastic responses in homologous genes showed 98% parallel regulation, while adaptive responses showed only 50% parallelism, indicating that the determinism of molecular evolution depends on the type of selection pressure.

In Drosophila experimental evolution, parallel gene expression changes in response to novel environments become increasingly dissimilar with greater genetic divergence between compared groups [21]. This pattern suggests that the adaptive architecture—including allele frequencies and effect sizes of contributing loci—becomes more distinct with increasing divergence, leading to reduced parallel evolution at the gene expression level. However, when genes are grouped by Gene Ontology categories, parallel responses become more apparent, supporting increased parallelism at higher hierarchical levels of biological organization [21].

Long-term evolution experiments with yeast populations reveal that phenotypic adaptation couples with steady accumulation of mutations, widespread genetic parallelism, and historical contingency over 10,000 generations [23]. The dynamics of fitness increase follow repeatable patterns of declining adaptability, while the rate of molecular evolution remains relatively constant. This demonstrates that parallel molecular evolution can persist over extended evolutionary timescales, though the probability of parallel adaptation decreases as populations approach their fitness optimum.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Reciprocal Transplant Designs with Transcriptomics

Objective: To disentangle the contributions of adaptation, plasticity, and genotype-by-environment interactions to molecular evolution patterns.

Protocol:

- Population Selection: Identify multiple natural populations of target species across environmental gradients. For Eucalyptus studies, select populations from tropical and temperate regions with similar coastal environments to minimize confounding climatic factors [22].

- Common Garden Establishment: Establish reciprocal common gardens in contrasting environments (e.g., temperature regimes). Utilize fully factorial designs where all genotypes are grown in all environments.

- RNA Sequencing: Extract RNA from target tissues under standardized conditions. For Eucalyptus species, leaf tissue provides representative gene expression profiles. Sequence using Illumina platforms with minimum 30 million reads per sample and three biological replicates.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Process raw sequences through quality control (FastQC), alignment (STAR or HISAT2), and quantification (featureCounts). Perform differential expression analysis using DESeq2 or edgeR, defining contrasts for plastic, adaptive, and genotype-by-environment interaction effects.

- Homology Assessment: Identify homologous genes between species using orthology prediction tools (OrthoFinder, InParanoid). Categorize parallel evolution when homologous genes show same expression direction, divergent evolution when expression directions oppose.

Laboratory Experimental Evolution

Objective: To observe molecular evolution in real-time under controlled selective pressures.

Protocol:

- Population Founding: Establish multiple replicate populations from common ancestral stock. Include both haploid and diploid populations when possible, as in yeast evolution experiments [23].

- Environmental Regimes: Apply consistent selective environments across replicates. For Drosophila, defined laboratory environments with controlled temperature, humidity, and nutritional resources [21].

- Generational Transfers: Maintain populations for hundreds to thousands of generations with regular propagation. Freeze archival samples at defined intervals (e.g., every 70 generations) to create a "frozen fossil record" [23].

- Fitness Assays: Conduct competitive fitness assays at multiple time points by mixing evolved populations with differentially marked reference strains.

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Sequence pooled population samples or individual clones at multiple time points. Identify SNPs, structural variants, transposable elements, and gene expression changes.

- Parallelism Quantification: Calculate parallelism indices by determining the proportion of shared differentiated genes or genomic regions between independent replicate populations.

Comparative Phylogenomics

Objective: To identify convergent molecular evolution across independently evolved lineages in natural systems.

Protocol:

- Species Selection: Identify multiple independent pairs of related species that have independently adapted to similar environments, such as annual killifish clades from Africa and South America [24].

- Genome Sequencing and Assembly: Generate high-quality genome assemblies for all target species using long-read technologies (PacBio, Nanopore) and chromatin conformation data (Hi-C) for scaffolding.

- Small RNA Sequencing: For non-model organisms, extract small RNAs from relevant tissues (e.g., killifish embryos during diapause) using mirVana kits [24]. Construct libraries with 3' adapters specifically designed for microRNA capture.

- Expression Quantification: Map sequences to reference genomes, count reads per microRNA, and normalize using DESeq2 accounting for library size differences.

- Convergence Testing: Apply phylogenetic comparative methods to identify genes or miRNAs showing repeated expression shifts in independent lineages adapting to similar environments, correcting for phylogenetic relatedness.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Transcriptomic Studies of Parallel Evolution

Melanocortin Pathway Linking Color and Behavior

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Molecular Evolution Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | Whole genome sequencing, RNA-seq, smallRNA-seq for variant calling and expression quantification |

| Bioinformatic Tools | DESeq2, edgeR, OrthoFinder, STAR, HISAT2 | Differential expression analysis, orthology prediction, sequence alignment |

| Specialized Kits | mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit, NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep | microRNA extraction and library preparation for non-model organisms |

| Reference Materials | Australian Tree Seed Centre collections, Drosophila Stock Centers | Source of genetically defined founding populations for evolution experiments |

| Laboratory Evolution | 96-well microplates for batch culture, environmental chambers | Maintain defined population structures and selective environments |

| Fitness Assay Tools | Fluorescently labeled reference strains, competition assays | Quantify relative fitness of evolved populations |

Discussion: Implications for Evolutionary Predictability

The documented patterns of convergent and parallel molecular evolution have profound implications for predicting evolutionary responses to environmental change. From the consistent slowing of adaptation rates observed in long-term yeast experiments [23] to the reduced parallelism in gene expression with increasing genetic divergence in Drosophila [21], molecular evolution demonstrates both predictable patterns and important limitations to evolutionary forecasting.

The evidence suggests that prediction is most reliable at higher levels of biological organization. While specific nucleotide substitutions may rarely be parallel, pathway-level and gene-level convergence occurs with remarkable frequency [24]. This hierarchical predictability offers promise for forecasting evolutionary responses to challenges such as climate change, antibiotic resistance, and disease adaptation.

For drug development professionals, these patterns inform strategies for anticipating resistance evolution. The redundant genetic architecture underlying complex traits means that targeted therapies may encounter multiple resistance mechanisms, yet constraints imposed by pleiotropy (as in the melanocortin pathway [25]) can create vulnerabilities that remain stable across evolutionary timescales. Understanding these molecular evolutionary patterns thus provides not only fundamental insights into life's diversity but also practical tools for addressing pressing challenges in medicine and conservation.

The Role of Neutral Evolution and Genetic Drift in Limiting Predictability

An In-depth Technical Whitepaper for Molecular Ecology and Drug Development Research

The question of evolutionary predictability—whether the paths and outcomes of evolution can be forecast from initial conditions—is foundational to molecular ecology and has profound implications for applied fields such as drug development. For decades, the Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution served as a central paradigm, positing that the majority of fixed mutations at the molecular level are neutral, governed not by natural selection but by the stochastic process of genetic drift [26]. This framework implied a certain degree of predictability, as the molecular clock hypothesis suggests a steady, time-dependent rate of neutral substitution. However, emerging research now fundamentally challenges this premise, revealing that the processes underlying molecular evolution are far from neutral and that the interplay of drift with other forces creates inherent limitations on our predictive capacity. This whitepaper synthesizes recent empirical evidence and theoretical advances to elucidate how neutral evolution and genetic drift act as critical, and often underestimated, constraints on evolutionary predictability. It is structured to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous technical guide, complete with quantitative data summaries, experimental protocols, and visual frameworks to inform future research and development strategies.

Theoretical Framework

The Foundational Paradigm and Its Modern Challengers

The Neutral Theory, first proposed in the 1960s, argued that most evolutionary changes at the molecular level result from the fixation of neutral mutations via genetic drift, with only a rare minority of adaptations driven by positive selection [26]. This theory provided a powerful null model for evolutionary biology. Its modern challengers, however, demonstrate that while the outcomes of evolution can appear neutral, the underlying processes are not.

Adaptive Tracking with Antagonistic Pleiotropy: A new model termed "Adaptive Tracking with Antagonistic Pleiotropy" reconciles the observed high rate of beneficial mutations with a lower-than-expected fixation rate. It proposes that a mutation beneficial in one environment can become deleterious when the environment changes. Consequently, populations are in a constant state of "chasing" their changing environments, preventing full adaptation and resulting in the fixation of mutations that appear neutral when observed over a longer timescale [26]. This dynamic directly limits predictability, as the trajectory of alleles is highly dependent on the sequence and nature of environmental fluctuations, which are themselves often unpredictable.

Constructive Neutral Evolution (CNE): CNE offers another non-adaptive route to complexity. It describes a process whereby a system's complexity increases without any gain in function, driven by neutral interactions that buffer the effects of deleterious mutations. A neutral interaction between two components (e.g., proteins A and B) can pre-suppress the negative effects of a future mutation in one component (A). This allows the otherwise deleterious mutation to drift to fixation, making the system dependent on the A-B interaction and thereby increasing its complexity [27]. The probabilistic "ratchet" of this process makes it more likely to repeat than reverse. For behavioural or molecular traits, CNE implies that observed complexity is not necessarily an adaptation and may be a historical artefact of neutral processes, posing a significant challenge to predicting evolutionary trajectories based on functional optimization.

Quantitative Genetics of Non-Neutral Traits

Predicting evolution for complex, non-Gaussian traits (e.g., survival, counts of offspring) requires specialized statistical approaches. The Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) framework has become a cornerstone for estimating quantitative genetic parameters for such traits. A key challenge is that GLMMs provide inferences on a statistically convenient latent scale, which is often non-linearly related to the observed data scale via a link function (e.g., logit, log) [28].