From Final Causes to Natural Selection: The Evolving History of Teleology in Evolutionary Biology

This article traces the complex history of teleological thinking in evolutionary biology, from its Aristotelian origins to contemporary debates.

From Final Causes to Natural Selection: The Evolving History of Teleology in Evolutionary Biology

Abstract

This article traces the complex history of teleological thinking in evolutionary biology, from its Aristotelian origins to contemporary debates. It examines how biology has grappled with apparent purpose in nature, from pre-Darwinian natural theology through the Darwinian revolution to modern concepts of teleonomy. For researchers and drug development professionals, we analyze methodological applications of teleological reasoning in functional biology, troubleshoot persistent conceptual pitfalls, and validate scientifically acceptable uses of goal-directed language within evolutionary frameworks. The synthesis offers critical insights for interpreting biological function and adaptation in biomedical research.

From Aristotle to Darwin: The Philosophical Foundations of Biological Purpose

The manifest appearance of function and purpose in living systems is responsible for the prevalence of apparently teleological explanations of organismic structure and behavior in biology. Despite the substantial advances in mechanistic understanding, teleological notions are largely considered ineliminable from modern biological sciences, including evolutionary biology, genetics, medicine, and ethology, because they play an important explanatory role [1]. This persistence of teleological language—the attribution of ends, purposes, and functions to biological traits—represents a direct intellectual lineage to Aristotle's concept of the final cause. The central question that frames contemporary debate is not whether teleological language appears in biology, but how such apparently goal-directed explanations should be understood within a naturalistic framework that otherwise rejects backward causation and vitalistic forces [1] [2].

The status of teleology in biology remains contested precisely because it sits at the intersection of empirical science and philosophical foundations. As Ernst Mayr identified, teleological notions remain controversial because they are suspected of being vitalistic, requiring backwards causation, incompatible with mechanistic explanation, mentalistic, or not empirically testable [1]. This paper traces the Aristotelian origins of biological teleology, examines its transformation through Darwinian evolution, and analyzes its contemporary manifestations in evolutionary biology research, with particular attention to implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Aristotle's Four Causes and the Foundation of Teleology

The Conceptual Framework of Aristotelian Causality

Aristotle's philosophy of nature proposed four distinct modes of explanation, or "causes" (αἰτία, aitia), that collectively provide a complete account of why things exist or change [3]. These four causes represent categories of questions that explain "the why's" of natural phenomena:

- Material Cause: The physical substrate or matter from which something is composed (e.g., the bronze of a statue)

- Formal Cause: The pattern, essence, or defining characteristics that make something what it is (e.g., the shape or form of the statue)

- Efficient Cause: The agent or mechanism that brings something into being (e.g., the sculptor crafting the statue)

- Final Cause (τέλος, telos): The end, purpose, or function for the sake of which something exists or occurs (e.g., the statue's purpose as a memorial) [3]

For Aristotle, the final cause represents the culmination of a developmental process, that toward which natural changes tend. In living systems, this teleology is immanent—the impetus for goal-directed processes and their ends are inherent principles within the organisms themselves [1]. As Aristotle observed, "This is most obvious in the animals other than man: they make things neither by art nor after inquiry or deliberation... It is absurd to suppose that purpose is not present because we do not observe the agent deliberating. Art does not deliberate. If the ship-building art were in the wood, it would produce the same results by nature. If, therefore, purpose is present in art, it is present also in nature" [3].

Aristotle's Biology and Immanent Teleology

Aristotle's biological works, including "History of Animals," "Parts of Animals," and "Generation of Animals," applied this teleological framework systematically to living organisms. He argued that we cannot adequately explain biological structures without reference to their functions—teeth are for chewing, roots are for nourishment, eyes are for seeing. This teleology is naturalistic and functional rather than creationist; the goal-directedness emerges from within nature itself, not from external design [1]. For Aristotle, a seed has the eventual adult plant as its final cause precisely because, under normal circumstances, the seed naturally develops into the adult plant [3].

Table 1: Aristotle's Four Causes Applied to Biological and Artificial Objects

| Cause Type | Definition | Biological Example | Artificial Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material | The matter from which a thing is made | Wood and leaves of a tree | Bronze of a statue |

| Formal | The pattern, essence, or structure | Photosynthetic capacity and branching structure | Shape and features of the statue |

| Efficient | The agent or mechanism of production | Germination and growth processes | Sculptor and tools |

| Final | The end, purpose, or function | Reproduction and providing shade | Memorialization of a person |

Aristotle distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic causes, with matter and form being intrinsic (dealing directly with the object), while efficient and final causes were extrinsic (external to the object) [3]. However, in his biological works, this distinction becomes nuanced—the final cause of an organism's development is immanent to the organism itself, an internal principle directing development toward the mature form.

Historical Transformation: From Divine Artifact to Natural Selection

Pre-Darwinian Teleology: Natural Theology and Intelligent Design

Before Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, the dominant framework for understanding biological teleology was through natural theology, which interpreted the appearance of function in nature as evidence of conscious design by a benevolent creator [4]. William Paley's 1802 "Natural Theology," with its famous watchmaker analogy, argued that the intricate adaptation of organisms to their environments—such as the eye's complex structure for seeing—necessarily implied a designer, just as a watch implies a watchmaker [4]. This perspective externalized and supernaturalized teleology, positioning biological purposes as artifacts of divine intention rather than immanent principles, as in Aristotle's framework.

This creationist teleology differed significantly from Aristotle's naturalistic final causes. While Aristotle saw teleology as inherent to nature itself, natural theology positioned it as imposed from without by a transcendent designer. This Platonic influence, particularly through the figure of the Divine Craftsman or 'Demiurge' from Plato's Timaeus, created a fusion of creationist and functionalist teleology that would dominate biological thought until Darwin [1].

Darwin's Revolutionary Naturalization of Teleology

Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection is widely regarded as having naturalized biological teleology, providing an explanation for the appearance of design without recourse to a designer [1] [4]. As philosopher Michael Ghiselin notes, Darwin succeeded in "getting rid of teleology and replacing it with a new way of thinking about adaptation" [1]. The theory explained how species "have been modified so as to acquire that perfection of structure and co-adaptation" without any appeal to a benevolent Creator [1].

However, Darwin's relationship with teleological language was complex. He consistently used the language of 'final causes' to describe biological functions in his Species Notebooks and throughout his life, while simultaneously providing a mechanistic explanation that rendered divine intervention unnecessary [1]. This ambiguity persists in contemporary biology, where teleological language remains ubiquitous despite natural selection's non-teleological mechanism.

Table 2: Transformation of Teleological Frameworks in Biology

| Historical Period | Primary Framework | Source of Teleology | Representative Thinkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Aristotelian Naturalism | Immanent to nature | Aristotle, Galen |

| Pre-Darwinian | Natural Theology | External Designer | John Ray, William Paley |

| 19th Century | Vitalism & Orthogenesis | Internal life force | Henri Bergson, Karl Ernst von Baer |

| Modern Synthesis | Evolutionary Biology | Natural selection | Theodosius Dobzhansky, Ernst Mayr |

| Contemporary | Pluralistic Naturalism | Selected functions | Francisco Ayala, contemporary biologists |

The Modern Synthesis and the Teleology Debates

The architects of the modern evolutionary synthesis (approximately 1930-1950) grappled extensively with how to reconcile teleological language with population genetics and natural selection. Ernst Mayr distinguished between "teleological" explanations (which he rejected as involving goal-directedness or future causation) and "teleonomic" explanations (which he endorsed as referring to programmed processes shaped by natural selection) [4]. This terminological distinction represented an attempt to preserve the utility of functional explanation while purging it of metaphysically problematic elements.

The mid-20th century also saw influential critiques of what Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin termed the "adaptationist programme"—the tendency to assume that every trait is an optimal adaptation forged by natural selection [4]. Their critique highlighted how facile teleological explanations could hinder biological understanding by overlooking constraints, historical contingencies, and non-adaptive byproducts.

Contemporary Manifestations in Evolutionary Biology

The Persistence of Teleological Language in Modern Biology

Despite concerted efforts to eliminate teleological language from biology, it remains deeply ingrained in evolutionary explanation. Biologists routinely make claims such as "The chief function of the heart is the transmission and pumping of the blood" or "The Predator Detection hypothesis remains the strongest candidate for the function of stotting [by gazelles]" [1]. This persistence suggests that teleological framing serves an important heuristic and explanatory function that is difficult to replace with purely mechanistic descriptions.

The geneticist J.B.S. Haldane famously captured this tension with his quip that "Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist: he cannot live without her but he's unwilling to be seen with her in public" [5]. Biologists continue to employ teleological language while explicitly distancing themselves from its metaphysical implications, treating it as a metaphorical shorthand or recognizing it as a distinctive form of explanation appropriate to living systems [5] [4].

Philosophical Accounts of Biological Teleology

Contemporary philosophy of biology has developed several naturalistic accounts of biological function that aim to preserve the legitimacy of teleological explanation while avoiding backwards causation or vitalism. These accounts generally fall into two broad categories:

Selected Effects Theories: Also known as etiological theories, these accounts define the function of a trait in terms of the historical selective pressures that shaped it. On this view, the function of the heart is to pump blood because this is the effect for which hearts were selected in evolutionary history [2] [4].

Causal Role Theories: Associated with philosophers like Robert Cummins, these accounts define function in terms of the current causal contribution a trait makes to the complex capacities of the system containing it. The heart's function is to pump blood because this activity contributes to the circulatory system's capacity to distribute nutrients and oxygen [2].

The selected effects approach has gained considerable traction because it aligns closely with evolutionary explanation and provides clear criteria for distinguishing proper functions from mere accidental effects. However, it faces challenges in explaining novel traits that have not yet undergone selection or traits that have been co-opted for new functions (exaptations) [4].

Mechano-Finalism and Contemporary Evolutionary Theory

A Bergsonian critique of contemporary evolutionary theory identifies what it terms "mechano-finalism"—the implicit teleology that persists despite official rejection of goal-directedness [5]. This manifests in two primary forms:

Implicit Optimization Assumptions: The adaptationist assumption that natural selection produces optimally designed traits, which treats selection as if it were striving toward predetermined optima [5].

Intentionality Attribution: The description of genes and organisms as rational agents maximizing reproductive success, which attributes human-like intentionality to evolutionary processes [5].

This mechano-finalism is particularly evident in optimization models in evolutionary biology and in the rhetoric of "selfish genes" that "seek" to maximize their replication. While defended as metaphorical, this language may import substantive assumptions that influence theory development and experimental design [5].

Methodology: Experimental Approaches to Teleological Questions

Testing Adaptive Hypotheses in Evolutionary Biology

Modern evolutionary biology has developed rigorous methodologies for testing teleological claims about biological functions. The standard approach involves determining whether a trait is an adaptation for a proposed function, which requires demonstrating:

- Heritability: The trait has a genetic basis and is transmitted across generations.

- Functional Utility: The trait contributes to a specific function that enhances survival or reproduction.

- Selective Advantage: The trait increases the fitness of organisms possessing it compared to alternatives [4].

For example, investigating the hypothesis that early feathers served an adaptive function in visual display rather than thermoregulation requires comparative analysis of fossil evidence, developmental patterns, and ecological context [1]. Such investigations exemplify how modern biology operationalizes and tests claims that would have been framed in terms of final causes in Aristotelian natural philosophy.

Experimental Protocols for Function Attribution

The following protocol outlines a generalized methodology for investigating biological function through experimental evolution and comparative analysis:

Protocol 1: Experimental Evolution of Functional Traits

Generate Variation: Create or identify populations with variation in the trait of interest (e.g., through mutagenesis, sampling natural variation, or utilizing existing genetic diversity).

Measure Performance: Quantify the relationship between trait variation and proposed functional outcomes (e.g., efficiency of resource utilization, success in predator avoidance, or reproductive success).

Track Selection: Monitor population changes over multiple generations to determine if traits with specific functional advantages increase in frequency.

Control Conditions: Maintain parallel control populations where the proposed selective pressure is absent to establish causal specificity.

Genetic Analysis: Identify genetic correlates of selected traits to establish heritability and genetic architecture.

This experimental approach provides empirical grounds for function attribution without recourse to teleological assumptions, instead relying on measurable selective pressures and fitness consequences.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Functional Analysis

| Research Reagent | Composition/Type | Function in Experimental Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenic Agents | Chemical (EMS) or Physical (UV radiation) mutagens | Generate genetic variation for selection experiments |

| Molecular Markers | SNP arrays, PCR primers, sequencing assays | Track heritability and identify genetic loci underlying traits |

| Fitness Assays | Competitive growth media, behavioral arenas, reproductive output measures | Quantify differential survival and reproduction |

| Phylogenetic Tools | DNA sequence alignments, morphological character matrices | Reconstruct evolutionary history and trait origins |

| Functional Genomics Tools | RNAi, CRISPR-Cas9, gene expression arrays | Manipulate and measure gene-trait-function relationships |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Teleological Reasoning in Disease Models and Drug Discovery

The Aristotelian legacy of functional explanation continues to shape biomedical research, particularly in how diseases are conceptualized and investigated. The framing of diseases as "functional disturbances" reflects teleological thinking—pathology is understood as deviation from normal functioning, where "normal functioning" is implicitly understood in teleological terms as the proper end or telos of biological processes.

In drug development, target identification often relies on teleological assumptions about biological systems. For instance, the investigation of sickle-cell anemia involves understanding why the sickle-cell gene persists in certain populations despite its harmful effects. The explanation references the historical selective advantage the gene provided against malaria—a teleological explanation referencing past selective pressures [1]. This example illustrates how evolutionary teleology informs medical understanding and therapeutic strategy.

Functional Explanation in Mechanism-of-Action Studies

The determination of drug mechanisms of action frequently employs teleological reasoning within a broader naturalistic framework. When researchers state that a drug "works by inhibiting" a specific enzyme to achieve a therapeutic effect, they are employing a form of teleological explanation—the inhibition is understood in terms of its functional consequence for the biological system and its contribution to the therapeutic outcome.

This explanatory structure mirrors Aristotle's four causes in modern guise: the drug's chemical composition (material cause), its molecular structure (formal cause), its binding interactions (efficient cause), and its therapeutic purpose (final cause). The legitimacy of this final cause attribution rests not on Aristotelian natural philosophy but on evolutionary history and demonstrated causal efficacy within complex biological systems.

The persistence of teleological explanation in biology, despite concerted efforts to eliminate it, suggests that Aristotle identified something fundamental about how we understand living systems. The appearance of purpose in nature may be explainable through the mechanistic processes of natural selection, but the explanatory power of functional language appears ineliminable from biological practice [1] [2] [4].

Contemporary evolutionary biology has naturalized Aristotelian final causes through the concept of selected functions, providing a framework for understanding purpose without consciousness, design without a designer, and teleology without mysticism. This transformed teleology retains the explanatory structure of Aristotle's framework while grounding it in the historical processes of variation, inheritance, and differential reproduction.

For researchers in biology and medicine, awareness of this philosophical legacy enables more nuanced reflection on the structure of biological explanation and the inescapable role of functional thinking in understanding living systems. The challenge is not to purge biology of teleology altogether, but to employ it with appropriate epistemic caution—recognizing its utility as an explanatory framework while remaining vigilant against its potential to import unwarranted assumptions about optimality or conscious design in nature.

The concept of teleology—the explanation of phenomena by reference to their purpose, ends, or goals—has profoundly influenced biological thought since antiquity. Prior to Charles Darwin's 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species, teleological reasoning provided the dominant framework for understanding the complexity and adaptation of living organisms. Within this historical context, William Paley's watchmaker analogy emerged as the most influential formulation of the design argument, asserting that the intricate functionality of nature necessitates an intelligent designer, much as the intricate mechanism of a watch implies a watchmaker [6] [7]. This argument, known as natural theology, sought evidence for the existence and attributes of a deity through the empirical study of nature [6]. This whitepaper examines the structure, historical antecedents, and scientific criticisms of Paley's argument, framing it within the broader history of teleology in evolutionary biology research. Understanding this intellectual heritage is crucial for contemporary researchers, as teleological concepts continue to inform philosophical debates about function, purpose, and directionality in biological systems, including those relevant to drug development and functional biology [8] [9].

William Paley's Watchmaker Analogy: Core Argument and Structure

In his 1802 work Natural Theology, William Paley presented his definitive formulation of the teleological argument for God's existence. The core of his argument rests on a simple yet powerful analogy. Paley asks the reader to imagine finding a watch upon a heath, as opposed to a simple stone [6] [10]. While one might entertain the idea that the stone had "lain there forever," the watch presents a different case entirely. Its complex, coordinated parts—gears, springs, and a dial—all work together for the purpose of timekeeping. This intricate mechanism, Paley argues, forces the mind to the inevitable conclusion that the watch "must have had a maker" who designed and assembled it for its purpose [6] [7] [11].

Paley then extends this logic to the natural world. He contends that every manifestation of contrivance and design found in the watch exists to an even greater degree in nature, "with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation" [6]. From the sophisticated anatomy of the human eye to the adapted features of the most humble organisms, such as the wings and antennae of an earwig, Paley saw evidence of deliberate design [6]. He concluded that just as the watch implies a watchmaker, the natural world implies a cosmic, intelligent designer—God [10]. For Paley, this designer was not only intelligent but also benevolent, having carefully designed all organisms and, by extension, cared for humanity [6].

Table 1: Core Components of Paley's Watchmaker Argument

| Component | Description | Function in the Argument |

|---|---|---|

| The Watch | A complex, functional object with interacting parts serving a purpose. | Serves as the analogue; its design is intuitively recognized as evidence of an intelligent maker. |

| The Stone | A simple, natural object without apparent complexity or function. | Provides a contrast to the watch, highlighting that not all objects trigger a design inference. |

| Contrivance | The purposeful arrangement of multiple parts to achieve a specific function. | The key observable property that distinguishes designed objects (watch) from non-designed ones (stone). |

| The Watchmaker | The intelligent agent who comprehends the watch's construction and designed its use. | The necessary conclusion from the observation of the watch; serves as the analogue for God. |

| Nature's Complexity | The observed intricacy, adaptation, and functionality of organisms and their parts. | The primary subject of the argument; presented as a vastly more complex version of the watch's contrivance. |

| The Divine Designer | The intelligent, benevolent creator God inferred from nature's complexity. | The ultimate conclusion of the argument, established by analogy from the watchmaker. |

Historical Antecedents and Intellectual Background

Paley's argument, while becoming the most famous version, was the culmination of a long tradition of teleological thought. The philosophical roots of teleology extend back to Ancient Greek philosophy. Plato, in his Timaeus, described the cosmos as the handiwork of a divine Craftsman (Demiurge) who fashioned the world according to eternal, perfect forms [12] [8]. More significantly, Aristotle developed the concept of final causes, wherein the end or purpose of a thing is part of its explanation. For Aristotle, this teleology was often immanent, or internal to natural entities, rather than imposed by an external designer [12] [8].

The Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries, with its discovery of universal laws of nature, reinforced the image of the universe as a perfect, law-governed machine [6]. Thinkers like Isaac Newton and René Descartes saw the orderly motion of planets and physical laws as evidence of a divine mechanic [6]. This led to the rise of Deism, which embraced the watchmaker analogy: just as a watch is set in motion by a watchmaker and then operates according to its internal mechanism, the universe was begun by a creator and then operated according to pre-established natural laws [6] [11].

Prior to Paley, several natural theologians employed similar mechanistic analogies. In 1696, William Derham's The Artificial Clockmaker presented a teleological argument for God's existence [7]. Notably, the philosopher David Hume offered devastating criticisms of the design argument in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779), published before Paley's Natural Theology. Hume argued that we have no experience of universe-making, that the analogy between human artifacts and the cosmos is weak, and that the argument could just as easily suggest multiple, finite, or imperfect designers [6] [10]. Despite these pre-emptive critiques, Paley's lucid and comprehensive formulation became the standard statement of the argument.

Table 2: Key Figures in the Pre-Darwinian Teleological Tradition

| Figure & Period | Contribution to Teleology/Design | Key Work(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Plato (427-327 BCE) | Cosmic teleology via a divine Craftsman (Demiurge) who models the world on eternal Forms. | Timaeus |

| Aristotle (384-322 BCE) | Immanent teleology; theory of four causes, including the final cause (telos) as the purpose or end of a thing. | Physics, De Anima |

| Cicero (106-43 BCE) | Early "intelligent design" argument using a sundial or water-clock analogy to argue for cosmic purpose. | The Nature of the Gods |

| Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) | Integrated Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology; his "fifth way" is an argument from design. | Summa Theologiae |

| Isaac Newton (1642-1727) | Saw the regular motion of planets and physical laws as evidence of a divine mechanic occasionally intervening. | Principia Mathematica |

| William Derham (1657-1735) | Used the clock analogy to argue for a designer from the evidence of nature. | The Artificial Clockmaker (1696) |

| David Hume (1711-1776) | Mounted a powerful philosophical critique of the design argument prior to Paley. | Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) |

| Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) | Combined evolution with teleology, proposing linear progression toward complexity driven by an innate tendency. | Philosophie Zoologique (1809) |

Pre-Darwinian Evolutionary Thought and Teleology

The intellectual landscape before Darwin was not exclusively dominated by static creationism. Various theories of species transformation (transformism) existed, but they often retained a teleological core. The dominant worldview was the Great Chain of Being, a static, hierarchical structure of all life forms from lowest to highest [11]. In the 18th century, this concept began to be "temporalized," transforming from a static chain into a ladder of ascent, with life progressing toward higher levels of perfection [11].

This teleological evolutionism is best exemplified by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. He proposed that species evolve, but his theory was one of progressive, linear evolution driven by an innate, goal-directed force toward greater complexity [11]. He combined this with a second mechanism—the inheritance of acquired characteristics—to explain adaptation. For Lamarck, the telos or goal of evolution was the production of increasingly complex organisms, culminating in humans [11]. This stood in sharp contrast to Darwin's later theory of branching evolution without a pre-ordained goal or direction.

The design argument, as articulated by Paley and others, was a direct response to materialistic and chance-based explanations of origins, such as those proposed by the ancient Epicureans and Atomists [12] [11]. Proponents like Robert Boyle argued that the intricate design of a biological organism, such as a dog's foot, displayed incomparably more art than the most complex human-made machine, like the clock at Strasbourg, making a divine engineer the only rational conclusion [11].

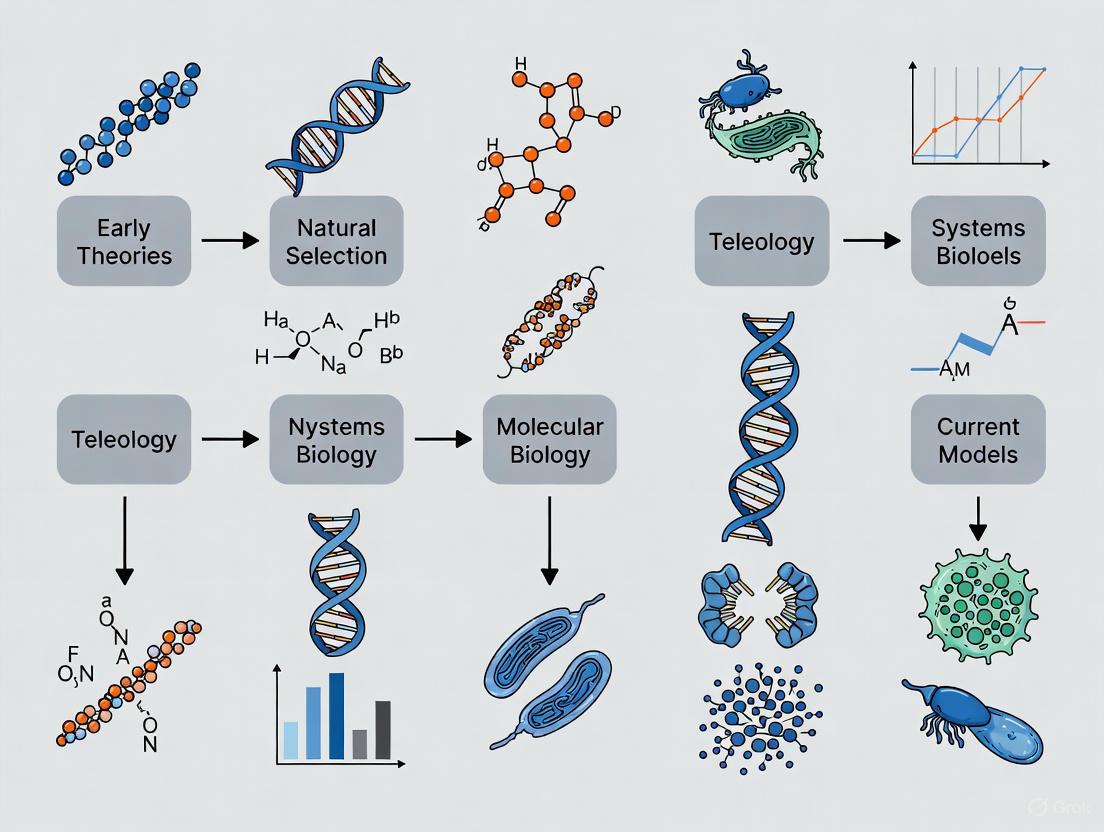

Diagram: The Intellectual Pathway to Darwin, illustrating how pre-Darwinian teleological concepts laid the groundwork for evolutionary thought while creating the central argument that Darwin's theory would challenge.

Scientific and Philosophical Rejection of the Watchmaker Argument

The publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859 provided a scientifically robust, naturalistic alternative to Paley's divine watchmaker. Darwin, who had studied Paley closely at Cambridge and initially admired his work, offered natural selection as a blind, automatic, and non-teleological process that could account for the appearance of design in nature [6] [7]. The mechanism of cumulative, undirected variation filtered by environmental pressures made the hypothesis of a designer scientifically superfluous for explaining adaptation [10].

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins famously updated the analogy in his 1986 book The Blind Watchmaker, arguing that "the only watchmaker in nature is the blind force of physics" and that natural selection, while having no purpose in mind, can explain the existence and complex form of all life [7] [10]. Dawkins concluded that Paley was "gloriously and utterly wrong," though he acknowledged that Paley's argument required a serious scientific response [7].

The core philosophical criticisms of Paley's argument, many pre-dating Darwin, remain powerful today. These include:

- The Weak Analogy: The universe and a watch are disanalogous in critical ways. We have experience of watches being made, but no experience of universe-making [6] [10].

- The Problem of Imperfection: The existence of poor design, vestigial organs, and natural evil (e.g., suffering) is difficult to reconcile with an omnipotent and benevolent designer [10].

- The Confusion of Law: Paley's claim that a "law" presupposes a "lawgiver" equivocates between descriptive laws of nature (which simply describe observed regularities) and prescriptive laws (which are created and enforced) [10].

- The Anthropomorphic Bias: The argument projects human-like qualities of design and purpose onto nature, a tendency that cognitive psychology suggests is intuitive but often misleading [9].

Contemporary Relevance and Teleology in Modern Biology

While Paley's specific design argument has been rejected by biological science, debates about teleology persist in more nuanced forms. Modern biology has sought to naturalize teleological language, stripping it of metaphysical implications while retaining its utility for describing function [8] [13].

Key contemporary discussions include:

- Teleonomy: Biologist Colin Pittendrigh (1958) coined the term teleonomy to describe the quality of being goal-directed in biological systems without implying conscious purpose. It refers to the appearance of purposefulness that is actually the product of an underlying mechanistic, evolutionary program [9].

- Biological Function: Attributing a "function" to a biological trait (e.g., "the function of the heart is to pump blood") remains a cornerstone of biological explanation. This is an epistemological use of telos, where the "end" is used as a heuristic tool, not a claim about a real goal in nature [9]. This is distinct from an ontological use of telos, which would assume goals truly exist in nature [9].

- Goal-Directedness in Evolution: Some researchers argue that certain large-scale evolutionary trends, driven by persistent natural selection (an "ecological field") or thermodynamic gradients, can exhibit a form of goal-directedness characterized by persistence and plasticity (the ability to reach a similar outcome from different starting points) [13]. This view is careful to state that such "goal-directedness" implies no intentionality or inevitability, but rather a predictable, constrained directionality [13].

For today's researchers and scientists, this history is critical. It underscores the importance of carefully distinguishing between heuristic teleological language (e.g., "this signaling pathway is for cell communication") and the actual, mechanistic causal explanations that constitute scientific understanding. This vigilance helps prevent the kind of teleological reasoning that can distort research questions and interpretations, particularly in fields like drug development, where understanding the mechanistic basis of function and failure is paramount.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Conceptual "Reagents" for Analyzing Teleology

| Conceptual Tool | Function/Explanation | Role in Modern Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Explanation | Explains phenomena by detailing the underlying physical causes and processes. | The foundational standard for causal understanding in biology and drug development. |

| Teleonomic Language | Describes goal-directed behavior in organisms as programmed by evolutionary history. | Allows for functional talk (e.g., "the immune system seeks out pathogens") without metaphysical commitment. |

| Etiological Theory of Function | Defines a trait's function as the effect for which it was naturally selected. | Links current function to evolutionary history; useful in comparative biology and evolutionary medicine. |

| Systems Biology | Studies complex interactions within biological systems, often using network models. | Provides a non-teleological framework for understanding emergent complexity and regulation. |

| Constraint Theory | Identifies factors (physical, genetic, developmental) that bias or limit the paths available to evolution. | Helps explain evolutionary trends and outcomes without invoking goals or purposes. |

The apparent purposefulness of living organisms has long presented a profound philosophical and scientific challenge. Before the Darwinian revolution, the natural world was predominantly interpreted through a theological lens, where the complex adaptation of organisms was seen as direct evidence of conscious, benevolent design—a view central to natural theology [4]. This perspective, exemplified by William Paley's watchmaker analogy, argued that organs like the eye, with their intricate structures perfectly suited for seeing, must have been designed for that purpose by a creator [4]. Teleological explanations, which account for phenomena by their goals or ends, were thus grounded in a divine planner. However, with the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, Charles Darwin, alongside Alfred Russel Wallace, provided a powerful alternative: a fully naturalistic mechanism—evolution by natural selection—that could explain the appearance of design without invoking a designer [14]. This Darwinian revolution did not eliminate teleological language from biology but sought to naturalize it, stripping it of its supernatural connotations and redefining biological purpose as the product of a blind, historical process. This whitepaper explores how Darwinian theory reconceptualized teleology, its enduring implications for modern biological research, and its practical applications in fields like drug discovery.

Historical Foundations of Teleology in Biology

The intellectual struggle with teleology predates Darwin by millennia. Ancient Greek philosophy, particularly Aristotle's concept of final causes, laid the groundwork by asserting that the purpose (telos) of a thing is a fundamental cause of its being [15] [4]. For Aristotle, this teleology was immanent and naturalistic, inherent to living beings themselves. In contrast, Plato's teleology was creationist, positing a divine Craftsman (Demiurge) who fashioned the world according to an external, eternal ideal [15]. This creationist view was later absorbed into Christian natural theology, which dominated European science for centuries. Figures like John Ray and William Paley argued that the adaptive complexity of organisms was incontrovertible proof of a intelligent designer [4].

By the 19th century, competing theories attempted to explain biological change. Lamarckism, for instance, proposed that organisms could acquire characteristics through use or disuse and pass them on, implying a different, non-selective path to adaptation [14]. Vitalist philosophies, such as Henri Bergson's élan vital, argued for a purposeful life force driving evolution [4]. These pre-Darwinian frameworks, while naturalistic in some respects, often retained elements of goal-directedness or mystical causation. Darwin's genius was to provide a mechanistic and empirically supported theory that could account for the same phenomena—adaptation and complexity—without recourse to any form of conscious intention, whether divine or vitalist.

Table 1: Major Pre-Darwinian Conceptions of Teleology

| Theory/Period | Key Proponents | Explanation for Adaptation/Purpose | Core Teleological Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aristotelian Teleology | Aristotle | Natural, immanent final causes inherent in organisms [15]. | Naturalistic, immanent goal-directedness. |

| Natural Theology | John Ray, William Paley | Conscious, benevolent design by a Creator God [4]. | External, divine design and purpose. |

| Lamarckism | Jean-Baptiste Lamarck | Inheritance of characteristics acquired through use/disuse [14]. | Naturalistic, but based on organismal effort and response to environment. |

| Vitalism/Orthogenesis | Henri Bergson, Karl Ernst von Baer | Driven by a purposeful life force (élan vital) or inherent directional trend [4]. | Internal, non-material purposeful drive. |

The Darwinian Mechanism: Natural Selection as a Naturalistic Explanation

Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection replaced conscious design with a mechanistic process relying on three observable, natural principles:

- Variation: All individuals within a population are unique, possessing slight variations in their heritable traits [14].

- Inheritance: Offspring inherit traits from their parents [14].

- Differential Survival and Reproduction: Individuals with traits better suited to their local environment are more likely to survive and reproduce, passing on those advantageous traits to the next generation [14] [4].

Over countless generations, this process of non-random selective retention of random variations leads to the accumulation of traits that are exquisitely adapted for survival and reproduction in a given environment. The long neck of the giraffe, for example, is not the result of striving to reach higher leaves but rather the outcome of generations of ancestors with slightly longer necks having better access to food and thus leaving more offspring [14]. This mechanism successfully naturalizes the concept of function. The function of the heart is to pump blood, not because a designer intended it so, but because ancestors with hearts that pumped blood more effectively were selected for [15] [4]. This redefinition provides a robust, empirical framework for explaining apparent design, making teleology scientifically respectable within biology.

Diagram 1: The logic of natural selection. This cyclical process explains adaptation without purposeful design.

Teleological Language in Modern Evolutionary Biology

Despite the successful naturalization of function, teleological language remains pervasive and controversial in evolutionary biology. Biologists frequently use shorthand phrases such as "the function of feathers is for flight" or "gazelles stott in order to signal to predators" [15] [4]. For many scientists, this language is a convenient, if technically imprecise, way to describe the evolutionary selected effect of a trait.

However, critics highlight several dangers in this practice. It can:

- Imply backward causation, where a future goal (e.g., flying) explains a current trait (feathers) [15] [4].

- Reinforce misconceptions among students, such as the belief that evolution is a purposeful or striving process [4].

- Resurrect the specter of vitalism or creationism, even if unintentionally [4].

Consequently, some biologists and philosophers advocate for purging teleological language entirely or replacing it with terms like teleonomy, which denotes goal-directed behavior arising from programmed mechanisms (like a thermostat) rather than conscious purpose [4]. Others, like philosopher Francisco Ayala, argue that such language is irreducible in biology, as it captures the real, functional organization of living systems that is the product of natural selection [4]. The consensus in modern research is that teleological statements are permissible as long as they are understood as a compact reference to the causal history of natural selection.

Table 2: Philosophical Stances on Teleology in Post-Darwinian Biology

| Philosophical Position | View on Teleology | Key Argument | Representative Thinkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminativism | Teleological language should be removed from biology. | It is misleading, promotes misconceptions, and is reducible to mechanistic descriptions [4]. | Ernst Mayr (in some writings), some biology educators. |

| Shorthand Interpretation | Teleology is a convenient, shorthand way of speaking. | It is a compact reference to the historical action of natural selection and is eliminable in principle [4]. | Many practicing evolutionary biologists. |

| Irreducibility Thesis | Teleological explanations are irreducible. | They capture a real, distinctive type of causation (functional explanation) based on natural selection [4]. | Francisco Ayala, J.B.S. Haldane. |

Experimental and Methodological Applications

The Darwinian framework is not merely a theoretical construct; it provides a powerful lens for designing and interpreting biological research, particularly in the context of adaptation. A key methodological principle is the distinction between a trait's current utility and its historical origin. The hypothesis that feathers are an adaptation for flight, for instance, must be tested against three criteria: heritability, current function in flight, and increased fitness in flying organisms [4]. However, paleontological evidence showing that non-flying theropod dinosaurs had feathers demonstrates that feathers are an exaptation for flight—a trait that evolved for one function (likely thermoregulation) and was later co-opted for another [14] [4]. This highlights the importance of historical data in testing adaptive hypotheses.

Experimental Protocol: Testing an Adaptive Hypothesis

Objective: To determine if a specific trait (e.g., a protein variant, a morphological structure, or a behavior) is an adaptation to a particular environmental pressure.

- Define the Trait and Proposed Function: Precisely characterize the trait and state a clear hypothesis about its adaptive function (e.g., "Variant A of protein P confers resistance to drug D").

- Establish Heritability: Conduct breeding studies or genetic analysis to confirm the trait has a heritable component.

- Measure Fitness Consequences: Design a controlled experiment (e.g., in the lab or field) to compare the fitness (survival and reproductive success) of individuals with and without the trait in the relevant environment.

- Example: Expose isogenic bacterial strains differing only in the presence of Variant A to drug D and measure growth rates and population size over time.

- Correlate Trait with Selective Pressure: Perform observational studies across a natural environmental gradient to correlate the prevalence of the trait with the intensity of the proposed selective pressure.

- Employ Comparative Phylogenetics: Use phylogenetic trees to trace the evolutionary history of the trait and determine if its origin correlates with the appearance of the proposed selective pressure, controlling for common ancestry.

This multi-pronged methodology helps avoid the "Panglossian paradigm" critiqued by Gould and Lewontin, which assumes every trait is an optimal adaptation, by rigorously testing adaptive stories against empirical evidence and historical data [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Evolutionary Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Evolutionary Biology

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application in Evolutionary Research |

|---|---|

| Model Organisms (Drosophila, E. coli, C. elegans, finches) | Used in real-time evolution experiments to observe selection, genetic drift, and adaptation under controlled conditions [14]. |

| Fossil Specimens & Paleontological Data | Provides historical evidence of trait evolution and lineage divergence, allowing tests of adaptive hypotheses over deep time [4]. |

| DNA Sequencing Kits & Platforms | Enables the identification of genetic variation, construction of phylogenetic trees, and detection of genes under positive selection. |

| Compound Libraries & High-Throughput Screeners | Allows for large-scale screening of natural or synthetic compounds to study evolutionary responses to novel chemical pressures, relevant to drug discovery [16]. |

| Computational Phylogenetic Software | Tools for building and analyzing evolutionary trees to infer relationships, divergence times, and character evolution. |

Case Study: Evolutionary Principles in Drug Discovery

The process of drug discovery shares remarkable parallels with natural selection, making it a powerful applied case study. The journey from a vast chemical library to a single approved medicine is a high-attrition process of variation and selection [16].

- Variation: Pharmaceutical companies maintain vast libraries of millions of chemical compounds, representing the "variation" upon which selection acts [16].

- Selection: This library is screened for biological activity against a target. Promising "lead" molecules are then subjected to iterative rounds of testing and chemical modification (analogous to mutation), with each round selecting for improved efficacy, specificity, and safety (the "fitness" criteria in this context) [16]. This iterative optimization is akin to the evolution of successive "generations" of drug molecules.

- Attrition: The extreme attrition rate, where few candidates survive to become medicines, mirrors the high extinction rate seen in evolution [16].

The Red Queen Hypothesis—the idea that organisms must constantly adapt to survive in a changing environment—also finds a parallel in the "arms race" between drug developers and pathogens or cancer cells, which can evolve resistance to therapies [16]. Furthermore, many breakthrough drugs, such as statins (discovered by Akira Endo) and H₂ receptor antagonists (developed by James Black), emerged from a deep understanding of evolutionary biology and comparative biochemistry, screening naturally occurring compounds or targeting evolutionarily conserved pathways [16]. This evolutionary perspective can guide the search for new medicines by focusing on fundamental biological processes shaped by evolution.

Diagram 2: The drug discovery pipeline as an evolutionary process.

The Darwinian revolution successfully naturalized the concept of purpose in biology by providing a mechanistic, non-teleological causal explanation—natural selection—for the appearance of design in living organisms. It transformed teleology from a theological or metaphysical premise into a scientifically tractable set of problems concerning function, adaptation, and evolutionary history. While teleological language persists as a useful, if sometimes problematic, shorthand in biological discourse, its meaning is now firmly anchored in the historical processes of variation, selection, and inheritance. This naturalized understanding of purpose continues to bear fruit, not only in fundamental evolutionary research but also in applied fields like drug discovery, where the principles of selection and adaptation provide a powerful framework for innovation. The Darwinian revolution, therefore, stands as a permanent and productive re-orientation of biological thought, allowing science to fully engage with the purposeful nature of life without resorting to supernatural explanation.

The Darwinian theory of evolution by natural selection fundamentally reshaped biological thought by providing a mechanistic, non-directed explanation for the diversity of life. However, this paradigm shift did not immediately eliminate alternative frameworks that incorporated elements of directionality, purpose, or inherent progressive tendencies in evolutionary change. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, vitalism and orthogenesis emerged as significant alternative teleological frameworks that challenged strictly Darwinian interpretations of evolutionary history. These frameworks shared a common skepticism that random variation and selective pressures alone could account for the apparent directionality, complexity, and coordinated development observed in the living world. This review examines the historical development, core principles, and scientific critiques of these alternative paradigms, situating them within the broader history of teleological thinking in evolutionary biology and exploring their potential resonances in contemporary biological research.

The enduring appeal of teleological explanations in biology stems from the apparent goal-directedness of living systems, from embryonic development to adaptive traits. While Darwinism explains this apparent purposiveness through the mechanistic process of natural selection, vitalism and orthogenesis proposed alternative causal mechanisms rooted in either a distinct life principle or an inherent directional tendency in variation itself [17] [2]. Understanding these historical frameworks provides valuable context for ongoing debates about evolutionary directionality, complexity, and the status of teleological language in modern biology.

Conceptual Foundations: Defining the Frameworks

Vitalism: The Life Force Hypothesis

Vitalism represents a diverse set of views united by the core proposition that living organisms are fundamentally distinct from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than inanimate things [17] [18]. This position holds that biological phenomena cannot be fully reduced to physical and chemical explanations alone.

Metaphysical Vitalism: This form of vitalism posits a distinct "vital force" (vis essentialis) or life principle that animates organic matter and demarcates living from non-living entities. Historically, this concept appeared in Aristotle's notion of the soul (psyche) as the organizing principle of life, Galen's pneuma as the essential life spirit, and Lamarck's postulation of an ordering "life-power" augmented by an inner "adaptive force" [17]. This framework implied that life requires explanation in terms of purposes and principles distinct from those governing inorganic matter.

Physical Vitalism: Also termed "scientific vitalism" or "process vitalism," this approach accepts physico-chemical determinism but rejects reductionist explanations that would reduce organisms merely to the sum of their parts [17]. Prominent exponents like Claude Bernard argued for the irreducible uniqueness of life, viewing organisms as integrated, harmonious wholes governed by principles like homeostasis. Modern complex systems dynamics theories in developmental biology that describe emergent properties not explainable by constituent parts alone share conceptual affinities with physical vitalism [17].

Orthogenesis: The Straight-Line Evolution Hypothesis

Orthogenesis (from Greek orthós, "straight," and génesis, "origin") represents the biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction toward some goal due to some internal mechanism or "driving force" [19] [20]. This framework rejected natural selection as the primary organizing mechanism in evolution in favor of a rectilinear model of directed evolution.

According to this view, once a species begins evolving in a particular direction, it continues along that trajectory due to intrinsic momentum rather than adaptive pressures [20]. The theory proposed that variation is not random but directed toward fixed goals, with selection playing a minimal role as species are carried automatically along paths determined by internal factors controlling variation [19]. Orthogenesis was particularly influential in paleontology, where fossil sequences were often interpreted as showing linear, directional trends that seemed difficult to explain through gradualistic natural selection [19].

Table 1: Core Principles of Vitalism and Orthogenesis

| Framework | Core Principle | Proposed Mechanism | Relationship to Natural Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitalism | Living organisms contain non-physical elements or are governed by different principles than inanimate matter | Vis essentialis (life force) or irreducible organizational principles | Inadequate to explain distinctive properties of life |

| Orthogenesis | Organisms evolve in definite directions due to internal driving forces | Innate tendencies in variation; internal momentum | Secondary or impotent compared to internal directionality |

Historical Development and Key Exponents

Vitalism: From Aristotle to Modern Times

The history of vitalism extends from ancient philosophical conceptions of life through to contemporary debates. Aristotle's concept of the soul (psyche) as the organizing principle of organisms established a teleological framework for understanding living things that would persist for millennia [17]. During the Enlightenment, vitalist theories experienced a resurgence, with Georg Ernst Stahl positing an anima responsible for organic organization, and the Montpellier vitalists emphasizing the irreducible uniqueness of living processes [17].

In the early 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck incorporated vitalist elements into his evolutionary theory, postulating both an ordering "life-power" and an inner "adaptive force" that guided evolutionary development toward greater complexity [17]. Throughout the 19th century, vitalism remained a significant position in biological thought, though it increasingly contended with advancing physiological explanations that sought to reduce biological phenomena to physic-chemical processes.

In the 20th century, vitalist perspectives were maintained by figures such as Hans Driesch, whose experiments on sea urchin embryogenesis led him to postulate a non-material entelechy as the coordinating factor in development [17]. Though largely marginalized within mainstream biology, vitalistic intuitions continue to resurface in various forms, particularly in debates about consciousness, the origin of life, and the limits of reductionist explanation [17] [18].

Orthogenesis: From Paleontology to Rejection

Orthogenesis emerged as a significant evolutionary framework in the late 19th century, particularly among paleontologists and biologists who observed what appeared to be directional trends in the fossil record. The term was introduced by Wilhelm Haacke in 1893 and popularized by Theodor Eimer, who studied butterfly coloration and argued for directional evolutionary trends independent of adaptive significance [19].

Key figures in the development of orthogenesis included:

- Carl Nägeli (1817-1891): Proposed an "inner perfecting principle" that directed evolutionary development, arguing that many evolutionary developments were nonadaptive and variation was internally programmed [19].

- Henry Fairfield Osborn (1857-1935): Advocated "aristogenesis," arguing that the germplasm contained potentialities for improvement that were realized over geological time, with nature not wasting "time or effort with chance or fortuity" [21].

- Leo Berg: Championed "nomogenesis," a form of orthogenesis incorporating Lamarckian evolution [20].

Orthogenesis was particularly influential in interpretations of evolutionary trends such as the increasing size of horse ancestors or the elaborate antlers of the Irish elk, which were interpreted as directional tendencies that might even lead species to extinction through over-specialization [19]. However, with the emergence of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis in the mid-20th century, which integrated genetics with natural selection, orthogenesis and other alternatives to Darwinism were largely abandoned by biologists [19].

Table 2: Historical Proponents and Their Contributions

| Figure | Time Period | Framework | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aristotle | 384-322 BCE | Vitalist | Concept of soul (psyche) as organizing principle |

| Jean-Baptiste Lamarck | 1744-1829 | Vitalist/Orthogenetic | Ordering "life-power" and inner "adaptive force" |

| Carl Nägeli | 1817-1891 | Orthogenetic | "Inner perfecting principle" directing evolution |

| Theodor Eimer | 1843-1898 | Orthogenetic | Popularized term; butterfly coloration studies |

| Henry Fairfield Osborn | 1857-1935 | Orthogenetic | "Aristogenesis" with germplasm potentialities |

Critical Responses and Scientific Rejection

The Modern Synthesis and Mechanistic Explanation

The development of the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis in the mid-20th century provided a comprehensive framework that marginalized both vitalism and orthogenesis as scientifically untenable. Key figures in this synthesis, such as George Gaylord Simpson, Ernst Mayr, and Theodosius Dobzhansky, articulated forceful critiques of these teleological frameworks [19] [21].

Simpson specifically attacked orthogenesis, linking it with vitalism by describing it as "the mysterious inner force" [19]. In his 1941 work "The Role of the Individual in Evolution," Simpson characterized teleological reasoning as "evolutionary fatalism" and rejected it as metaphysical and antithetical to mechanistic Darwinian evolution [21]. He specifically targeted Osborn's "aristogenesis," arguing that predetermined trends and vitalistic explanations could not be justified when mechanistic genetic terms provided sufficient explanation [21].

Ernst Mayr made the term orthogenesis effectively taboo in mainstream biology by stating in a 1948 Nature article that it implied "some supernatural force" [19]. The emerging consensus viewed orthogenesis as incompatible with population genetics and the understanding of mutation as random with respect to adaptive needs.

Philosophical and Empirical Problems

Both vitalism and orthogenesis faced significant philosophical and empirical challenges that led to their rejection by mainstream biology:

- Lack of Mechanism: Neither framework could propose a testable physical mechanism for the purported vital force or directional evolutionary trends. The "life principle" of vitalism remained metaphysically undefined and inaccessible to empirical investigation [17] [18].

- Incompatibility with Genetics: Orthogenesis conflicted with the understanding of mutation as random with respect to adaptive needs, a cornerstone of population genetics [19] [22].

- Teleological Nature: Both frameworks were criticized for their teleological implications, suggesting purpose or end-goals in evolution, which contradicted the non-directed, mechanistic understanding of evolutionary processes [19] [20].

- Alternative Explanations: Apparent directional trends in evolution could be explained through orthoselection (consistent selective pressures) or developmental constraints without invoking internal directional forces [19].

Despite these criticisms, some elements of both frameworks persist in modified forms in contemporary biology, particularly in debates about evolutionary directionality, complexity, and the status of teleological language in biological explanation [23] [17].

Contemporary Resonances and Reformulations

Modern Analogues and Conceptual Legacies

While vitalism and orthogenesis as historically formulated have been largely rejected, certain contemporary biological concepts bear functional similarities or address similar theoretical spaces:

Teleonomy and Biological Complexity: The concept of "teleonomy" was introduced as an evolutionary replacement for teleological explanations, recognizing the goal-directed appearance of biological systems while grounding this directionality in evolutionary mechanisms [23] [2]. Recent work has proposed quantifying "teleonomic complexity" through life history theory, measuring how organisms have evolved complex strategies to optimize fitness [23] [24]. This represents a naturalistic reformulation of the intuition behind orthogenetic complexity increases.

Extended Evolutionary Synthesis: Contemporary challenges to the Modern Synthesis, such as James Shapiro's work on "natural genetic engineering," emphasize the role of targeted cellular responses to environmental challenges [22]. While explicitly rejecting vitalism, these approaches share with vitalism a emphasis on the active, responsive capacities of organisms rather than purely random variation.

Empirical Vitalism: Some recent approaches have attempted to develop what might be called an "empirical vitalism" that acknowledges the distinctive properties of organisms while remaining naturalistic [18]. These approaches emphasize the self-generating, teleological organization of living systems as an empirical phenomenon that requires distinctive explanatory strategies, without positing supernatural agencies [18].

Visualization of Conceptual Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the historical development and conceptual relationships between vitalism, orthogenesis, and mainstream evolutionary biology:

Conceptual Evolution of Teleological Frameworks in Biology

Research Reagents and Methodological Approaches

Table 3: Analytical Approaches for Studying Historical and Contemporary Teleological Frameworks

| Methodology | Application | Key Insights | Contemporary Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paleontological Trend Analysis | Identifying directional patterns in fossil sequences | Distinguishing selective trends from apparent directionality | Cope's Rule (body size increases) analysis [23] |

| Developmental Genetics | Investigating constraints on phenotypic variation | Identifying internal constraints on evolutionary possibilities | Evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo) [22] |

| Genome Sequencing & Analysis | Detecting targeted genetic changes | Assessing "read-write" genome capabilities vs. random mutation | Natural genetic engineering phenomena [22] |

| Philosophical Analysis | Clarifying teleological concepts | Distinguishing teleonomy from teleology | Function and proper function analyses [2] [25] |

| Life History Theory | Quantifying teleonomic complexity | Measuring complexity in survival/reproduction strategies | Life history strategy matrices [23] [24] |

Vitalism and orthogenesis represent significant chapters in the history of biological thought, reflecting persistent intuitions about directionality, purpose, and the distinctive nature of living systems. While these frameworks in their original forms were legitimately rejected for lack of empirical support and testable mechanisms, the theoretical spaces they occupied continue to resonate in contemporary biology.

The vitalist intuition that organisms possess distinctive organizational properties not fully reducible to their physical components finds echoes in contemporary systems biology, complex systems theory, and theories of biological autonomy [17] [18]. The orthogenetic observation of directional trends in evolution reemerges in discussions of evolutionary progress, complexity increases, and constraints on variation [23] [19]. Both frameworks highlight enduring tensions in biological explanation between mechanism and organization, between contingency and directionality, and between reductionist and holistic approaches.

For modern researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these historical frameworks provides valuable perspective on contemporary debates about evolutionary mechanisms, biological complexity, and the appropriate use of teleological language in biology. While the specific mechanisms proposed by vitalism and orthogenesis have not withstood scientific scrutiny, the broader questions they raised about directionality, organization, and the distinctive properties of living systems continue to inform cutting-edge biological research.

The Modern Synthesis of the early 20th century represents a pivotal period in evolutionary biology, successfully integrating Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection with Gregor Mendel's principles of heredity into a unified mathematical framework [26]. This synthesis emerged from what Julian Huxley termed the "eclipse of Darwinism," a period when biologists grew skeptical of natural selection due to weaknesses in Darwin's account of inheritance, particularly his adherence to blending inheritance which implied that beneficial variations would be weakened each generation [26]. The reconciliation was achieved primarily through mathematical population genetics, which demonstrated how Mendelian genetics with discrete inheritance units could maintain the variation necessary for natural selection to operate effectively over time [26] [27].

The central teleological challenge the Modern Synthesis addressed was the apparent contradiction between the undirected, non-goal-oriented mechanism of natural selection and the seemingly purposeful adaptations observed in nature. Prior to the synthesis, teleological explanations persisted in evolutionary thinking, often implicitly suggesting that evolution proceeded toward predetermined goals or that variations arose to meet organisms' needs [28]. The architects of the Modern Synthesis, including R.A. Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane, and Sewall Wright, developed mathematical models that demonstrated how complex adaptation could emerge from the cumulative selection of random variations without recourse to forward-looking mechanisms or purposeful direction [26] [27] [29].

Historical Predecessors to the Synthesis

The Problem of Inheritance in Darwinian Evolution

Darwin's original theory faced significant challenges regarding the mechanism of inheritance. His theory of pangenesis, with contributions to the next generation (gemmules) flowing from all parts of the body, implied Lamarckian inheritance as well as blending [26]. This presented a fundamental problem, as Fleeming Jenkin noted in 1868, that any new variation would be weakened by 50% each generation through blending inheritance, making it difficult for small variations to survive long enough to be selected [26]. This conceptual weakness led to the "eclipse of Darwinism" from the 1880s onward, with biologists exploring alternatives including Lamarckism, orthogenesis, saltationism, and mutationism [26].

August Weismann's germ plasm theory, set out in his 1892 work "The Germ Plasm: a Theory of Inheritance," fundamentally challenged this view by proposing a one-way relationship between the germ plasm (hereditary material) and the rest of the body (the soma) [26]. His experiments demonstrating that amputated tails in mice did not affect offspring tails provided evidence for 'hard' inheritance, directly countering Lamarckian views and intensifying debates about evolutionary mechanisms [26].

The Mendelian-Biometrician Debate

The rediscovery of Mendel's work in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns initially exacerbated theoretical divisions in evolutionary biology [26]. Two opposing schools emerged: the Mendelians (including William Bateson and de Vries) who favored mutationism—evolution driven by discrete mutations—and the biometric school (led by Karl Pearson and Walter Weldon) who focused on continuous variation and questioned how Mendelism could explain gradual evolution [26]. This debate reflected deeper philosophical divisions about the nature of evolutionary change and whether it occurred through dramatic jumps or gradual accumulation of small variations.

Table 1: Key Figures in the Development of the Modern Synthesis

| Researcher | Contribution | Timeline | Key Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| R.A. Fisher | Mathematical population genetics | 1918-1930 | The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection (1930) |

| J.B.S. Haldane | Analysis of real-world selection examples | 1920s | Series of papers on industrial melanism |

| Sewall Wright | Population structure and genetic drift | 1930s | Evolution in Mendelian Populations |

| Theodosius Dobzhansky | Integration of genetics with natural populations | 1937 | Genetics and the Origin of Species |

| Ernst Mayr | Species concept and speciation | 1942 | Systematics and the Origin of Species |

| George Gaylord Simpson | Integration of paleontology | 1944 | Tempo and Mode in Evolution |

| G. Ledyard Stebbins | Botanical evidence | 1950 | Variation and Evolution in Plants |

Core Conceptual Advances of the Modern Synthesis

Mathematical Population Genetics

The foundational achievement of the Modern Synthesis came through mathematical demonstration that Mendelian genetics was compatible with gradual evolution by natural selection. In 1918, R.A. Fisher's paper "The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance" showed how continuous variation could arise from multiple discrete genetic loci [26]. Fisher's work, culminating in his 1930 book "The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection," demonstrated that rather than opposing natural selection, Mendelian genetics actually provided the stable inheritance mechanism that selection required [26].

Simultaneously, J.B.S. Haldane analyzed real-world examples of natural selection, such as the evolution of industrial melanism in peppered moths, providing empirical quantification of selection in natural populations [26]. Sewall Wright's work on population structure and genetic drift added further dimension to the understanding of how evolutionary forces interact in finite populations [27]. These mathematical treatments collectively demonstrated that natural selection acting on Mendelian variations could produce evolutionary change without teleological guidance.

The "No Teleology" Condition in Natural Selection

A central philosophical contribution of the Modern Synthesis was its explicit rejection of teleological mechanisms in evolution. As later articulated by philosophers of biology, natural selection requires a "no teleology" condition that distinguishes it from artificial selection, intelligent design, or orthogenetic theories [29]. This condition specifies that the evolutionary process is not guided toward a predetermined endpoint, variation is produced randomly with respect to adaptation, and selection pressures are not forward-looking [29].

The synthesis established that while organisms appear designed, this apparent design emerges from purely mechanistic processes—natural selection sorting random variations based on their immediate adaptive value rather than future utility. This represented a crucial departure from earlier evolutionary theories that implicitly or explicitly incorporated purposeful direction, whether through internal drives (orthogenesis) or acquired characteristics (Lamarckism) [29].

Diagram 1: Conceptual reconciliation in the Modern Synthesis

Key Experimental Evidence

Castle's Hooded Rat Experiments

Experimental Protocol: Beginning in 1906, William Castle conducted a systematic long-term study on the effects of selection on coat color patterns in rats [26]. The experimental methodology involved:

- Initial Crosses: Crossing hooded rats (showing a recessive piebald pattern) with both wild-type grey rats and "Irish" patterned rats

- Back-crossing: Subsequent generations were back-crossed with pure hooded rats

- Selection Regime: Different groups were selectively bred for either larger or smaller dark stripes on their backs for five consecutive generations

- Measurement: Quantitative assessment of stripe size variation across generations

Results and Interpretation: Castle found that selective breeding could produce characteristics "considerably beyond the initial range of variation" [26]. By 1911, he concluded that these results could be explained by Darwinian selection acting on heritable variation involving multiple Mendelian genes, directly refuting de Vries's claim that continuous variation was environmentally induced and non-heritable [26]. This provided crucial evidence that selection acting on Mendelian factors could produce gradual evolutionary change.

Morgan's Drosophila Research

Experimental Protocol: Thomas Hunt Morgan initially approached genetics as a saltationist, attempting to demonstrate that mutations could produce new species in fruit flies in single steps [26]. His experimental methodology included:

- Mass Breeding: Maintaining large populations of Drosophila melanogaster under controlled conditions

- Mutation Screening: Systematic identification and characterization of spontaneous mutations

- Inheritance Tracking: Meticulous documentation of inheritance patterns across generations

- Chromosome Mapping: Correlation of inheritance patterns with chromosomal structures

Results and Interpretation: By 1912, Morgan's extensive work demonstrated that fruit flies had "many small Mendelian factors (discovered as mutant flies) on which Darwinian evolution could work as if the variation was fully continuous" [26]. Rather than producing new species in single jumps, mutations increased genetic variation in populations, providing the raw material for gradual selection. This evidence helped convince geneticists that Mendelism supported rather than contradicted Darwinism.

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting the Modern Synthesis

| Experimental System | Researcher | Time Period | Key Finding | Teleological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hooded Rats | William Castle | 1906-1911 | Continuous variation from Mendelian genes | Refuted saltationist teleology of directed large mutations |

| Fruit Flies | Thomas H. Morgan | 1910-1912 | Multiple small factors enable gradual evolution | Undermined essentialist species concepts |

| Peppered Moths | J.B.S. Haldane | 1920s | Quantitative measurement of selection | Demonstrated non-teleological adaptation to environment |

| Population Genetics | R.A. Fisher | 1918-1930 | Mathematical reconciliation | Established non-teleological framework for adaptation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Methodologies and Reagents in Modern Synthesis Research

| Method/Reagent | Function | Example Application | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organisms (Drosophila, Rats) | Genetic crossing experiments | Morgan's fruit flies, Castle's rats | Enabled controlled inheritance studies |

| Statistical Methods | Quantitative analysis of variation | Fisher's population genetics | Provided mathematical rigor to evolutionary theory |

| Selection Experiments | Artificial selection studies | Castle's hooded rat program | Demonstrated efficacy of selection on Mendelian variations |

| Chromosomal Mapping | Physical localization of genes | Morgan's Drosophila lab | Connected abstract genes to physical structures |

| Mendelian Cross Analysis | Tracking discrete inheritance | All key studies | Established particulate inheritance mechanism |

Teleological Reasoning as a Persistent Challenge

Cognitive and Educational Dimensions

Despite the conceptual advances of the Modern Synthesis, teleological reasoning persists as a significant challenge in evolutionary education and understanding. Research indicates that teleological thinking—the cognitive tendency to explain phenomena by reference to goals or purposes—represents a universal default in human cognition [30]. Students across educational levels demonstrate implicit associations between genetic concepts and teleological explanations, viewing genes as having goals ("genes turn on so that a cell can develop properly") or embodying essentialist qualities [31].

This teleological bias is remarkably persistent, remaining active even in scientifically trained individuals when under cognitive pressure or time constraints [30]. Neuroscience and education research reveals that teleological thinking is not eliminated by scientific education but rather coexists with scientific understanding, requiring conscious effort to suppress in appropriate contexts [31] [30].

Addressing Teleology in Evolution Education

Modern pedagogical approaches have shifted from attempts to eliminate teleological reasoning entirely toward developing metacognitive vigilance—the ability to recognize and regulate the use of teleological thinking [28]. Effective educational strategies include: