From Folding Pathways to Drug Discovery: Leveraging Molecular Dynamics for Protein Simulation

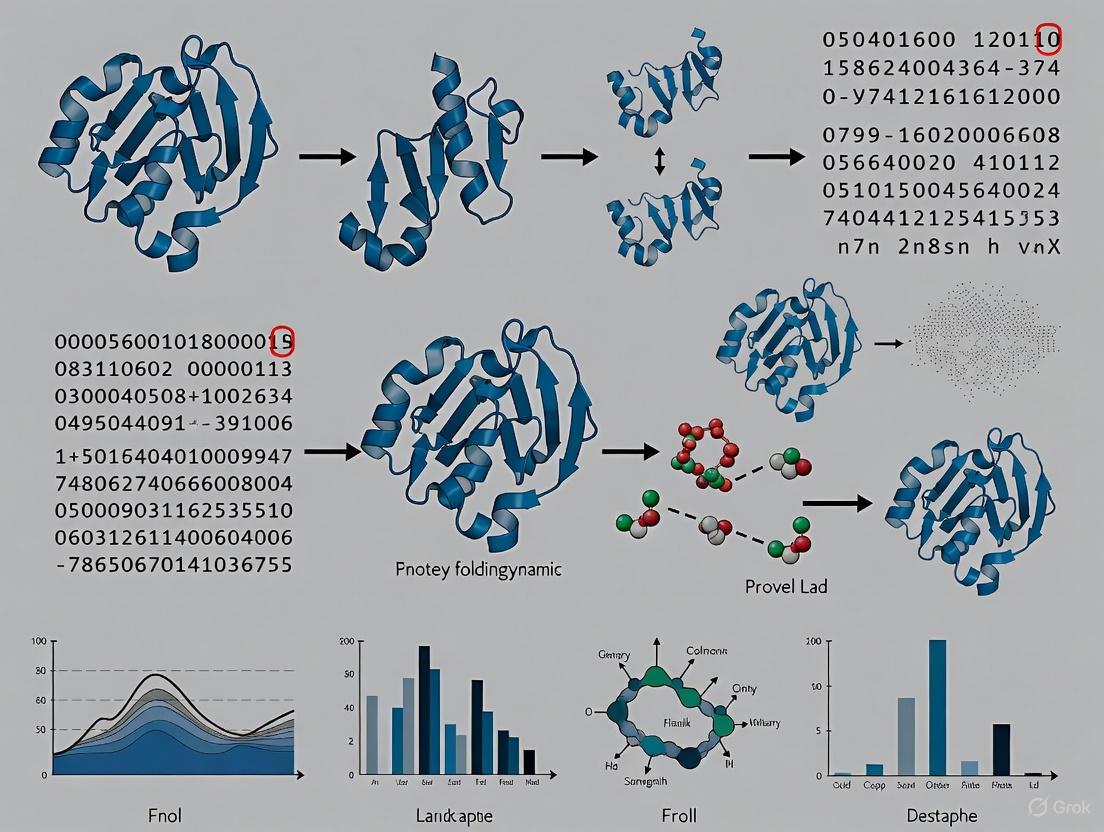

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have revolutionized the study of protein folding, moving beyond static structures to capture dynamic conformational ensembles.

From Folding Pathways to Drug Discovery: Leveraging Molecular Dynamics for Protein Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have revolutionized the study of protein folding, moving beyond static structures to capture dynamic conformational ensembles. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, explores advanced methodological applications in rational drug design, and addresses key challenges like sampling limitations and force field accuracy. The content further discusses rigorous validation protocols against experimental data and comparative analyses of simulation software. By synthesizing insights from traditional simulations and cutting-edge machine-learning approaches, this review serves as a critical resource for leveraging MD to uncover folding mechanisms, predict protein behavior, and accelerate therapeutic development.

The Atomic Dance: Fundamental Principles of Protein Folding and MD Simulation

The lock-and-key model, a foundational concept in structural biology, provides a useful but static representation of molecular interactions. We now understand that protein function is not solely determined by static three-dimensional structures but is fundamentally governed by dynamic transitions between multiple conformational states [1] [2]. This shift from static to multi-state representations is crucial for understanding the mechanistic basis of protein function and regulation [1].

Proteins exist as dynamic conformational ensembles—collections of interconverting structures under thermodynamic equilibrium [1]. These ensembles include stable states, metastable states, and the transition states between them, forming a complex energy landscape that dictates protein behavior [1]. For drug development professionals, this paradigm shift opens new avenues for targeting previously "undruggable" proteins, including those with intrinsic disorder or multiple conformational states [3] [4].

The Scientific Framework: From Static Structures to Dynamic Ensembles

Key Concepts and Biological Significance

Protein dynamic conformations refer to the process of conformational change over time and space, encompassing both subtle fluctuations and significant conformational transitions [1]. Many functional proteins rely on these dynamic changes to perform specific biological roles: enzymes modulate conformational states to facilitate catalytic processes, while membrane proteins utilize specific conformational transitions to mediate signal transduction and regulate molecular transport [1].

The conformational ensemble represents the collection of independent conformations of proteins in various motion states under certain conditions, reflecting the structural diversity of the protein under thermodynamic equilibrium [1]. This ensemble captures the distribution and probabilities of the protein's conformations under given conditions, effectively representing dynamic conformations under specific experimental or physiological contexts [1].

Factors Driving Conformational Diversity

- Intrinsic Factors: The presence of disordered regions lacking stable secondary structure results in higher flexibility. Relative rotations or adjustments between structural domains also facilitate transitions between different conformations. Proteins such as GPCRs, transporters, and kinases undergo specific conformational changes to perform their biological functions [1].

- Extrinsic Factors: Different conformational states can be triggered by ligand binding or interactions with other macromolecules. Changes in environmental factors such as temperature, pH, and ion concentration directly impact protein stability and conformation. Mutations in the primary amino acid sequence may also induce conformational shifts [1].

Emerging evidence indicates that dynamic information facilitating conformational transitions may be inherently encoded within the protein sequence itself, independent of external environmental perturbations [1].

Methodological Approaches for Studying Conformational Ensembles

Computational Advances in the Post-AlphaFold Era

The emergence of deep learning has revolutionized static protein structure prediction, but capturing dynamic conformational changes remains challenging [1]. Several computational approaches have been developed to address this limitation:

- AlphaFold-based Enhanced Sampling: Modifying AlphaFold2 inputs through multiple sequence alignment (MSA) masking, subsampling, and clustering to capture different co-evolutionary relationships and generate diverse predicted conformations [1].

- Generative Models: Utilizing diffusion models and flow matching to predict protein multiple conformations by transforming structure prediction into sequence-to-structure generation through iterative denoising [1].

- Ensemble Methods: The FiveFold methodology combines predictions from five complementary algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D) to model conformational landscapes through consensus-building and variation quantification [4].

Table 1: Computational Methods for Dynamic Conformation Prediction

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Principles | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSA-based Deep Learning | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold | Uses evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments | High-accuracy prediction for well-folded proteins | Limited for proteins with poor evolutionary coverage |

| Protein Language Models | OmegaFold, ESMFold | Single-sequence methods using language model embeddings | Orphan sequences, limited homologous information | May sacrifice accuracy in complex fold prediction |

| Generative Models | Diffusion Models, RFdiffusion | Iterative denoising from sequence to structure | Designing flexible binders for disordered proteins | Computational intensity, training data requirements |

| Ensemble Methods | FiveFold | Consensus-building from multiple algorithms | Conformational diversity, intrinsically disordered proteins | Complexity in interpretation and validation |

Experimental Techniques for Capturing Dynamics

Experimental methods provide crucial validation for computational predictions and direct observation of dynamic processes:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Characterizes proteins in solution, capturing dynamic information and resolving flexible or disordered regions [5].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Enables visualization of large macromolecular complexes at near-atomic resolution without crystallization, particularly valuable for membrane proteins and flexible assemblies [5] [6].

- Time-Resolved Crystallography: Uses advanced X-ray sources to capture transient molecular states and conformational changes at atomic resolution [6].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Provides atomistic insights into biomolecular behavior over time by solving Newton's equations of motion for each atom in the system [5].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Ensemble Structure Prediction with FiveFold

Purpose: To generate multiple plausible conformations for proteins, especially intrinsically disordered proteins and flexible regions.

Experimental Principles: The FiveFold methodology integrates predictions from five structure prediction algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D) to create a conformational ensemble. The system uses Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC) for standardized secondary structure representation and Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM) to capture and visualize conformational diversity [4].

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Obtain the amino acid sequence of the target protein in FASTA format.

- For specific applications, identify regions of interest (disordered regions, binding sites, mutation sites).

Parallel Structure Prediction

- Run structure prediction using all five algorithms with default parameters.

- For MSA-dependent methods (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold), ensure adequate MSA depth.

- For language model-based methods (ESMFold), use appropriate model variants.

PFSC Assignment

- Convert each predicted structure to PFSC representation.

- Assign secondary structure states (H: α-helix, E: β-strand, B: β-bridge, G: 3₁₀ helix, I: π-helix, T: turn, S: bend, C: coil) for each 5-residue window.

- Create standardized structural representations for comparison.

PFVM Construction

- Align structural features across all five predictions.

- Identify consensus regions and systematic differences.

- Construct probability matrices showing likelihood of each state at each position.

Conformational Sampling

- Define diversity requirements (minimum RMSD between conformations, secondary structure content ranges).

- Use probabilistic sampling to select combinations of secondary structure states.

- Apply diversity constraints to ensure broad coverage of conformational space.

Structure Generation and Validation

- Convert PFSC strings to 3D coordinates using homology modeling.

- Perform stereochemical validation (Ramachandran plots, rotamer analysis).

- Filter for physically reasonable conformations.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If ensemble lacks diversity, adjust sampling parameters to increase structural variation.

- For computationally intensive targets, consider sequential rather than parallel execution.

- Validate against available experimental data (NMR, cryo-EM) when possible.

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics Analysis with mdciao

Purpose: To analyze and visualize residue-residue contact dynamics from MD simulation trajectories.

Experimental Principles: mdciao is an open-source Python API that computes residue-residue contact frequencies using a modified version of MDtraj's contact calculation methods. It focuses on transparent, universal metrics with hard cutoffs and exploits consensus nomenclature for selection and comparison [7].

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Gather MD trajectory files in supported formats (xtc, dcd, h5, etc.).

- Prepare corresponding topology file (pdb, prmtop, etc.).

- Define molecular fragments or residues of interest.

Contact Frequency Calculation

- Set distance cutoff parameters (default: 4.5Å for heavy atoms).

- Choose distance scheme (closest heavy-atoms, Cα-atoms, center of mass).

- Compute contact frequencies using formula:

ContactGroup Object Creation

- Instantiate ContactGroup object encapsulating all distance-related data.

- Store residue pairs, atom pairs, molecular topology, fragment labels.

- Serialize object to .npy file for storage and re-use.

Analysis and Visualization

- Generate frequency reports and contact matrices.

- Create flare plots showing interaction networks.

- Plot distance distributions and time traces.

- Compare frequencies across different MD setups.

Domain-Specific Annotation

- Query online databases for generic residue numbering (GPCRs, G-proteins, kinases).

- Automatically annotate figures with domain-specific information.

- Enable comparison across different systems regardless of sequence identity.

Key Parameters:

- Distance cutoff (δ): Typically 4.5Å for heavy atoms

- Schemes: closest heavy-atoms, Cα-atoms, center of mass

- Trajectory stride: Adjust based on trajectory length and computational resources

Protocol 3: Targeting Disordered Proteins with AI-Assisted Binder Design

Purpose: To design binders for intrinsically disordered proteins using RFdiffusion and related approaches.

Experimental Principles: This approach uses deep learning-based protein design to create flexible binders that target disordered regions. Unlike traditional methods that seek static binding pockets, this technique designs binders that can adapt to the conformational ensemble of disordered targets [3].

Procedure:

Target Identification

- Identify disordered regions from sequence or prediction tools.

- Select target sequences of interest (e.g., tau protein in Alzheimer's disease).

Binder Design with RFdiffusion

- Input target amino acid sequence (not structure) into RFdiffusion.

- Specify design parameters for flexibility and binding interface.

- Generate initial binder designs.

Binder Optimization

- Screen designs for stability and binding affinity.

- Use structural validation to ensure physical realism.

- Select top candidates for experimental testing.

Experimental Validation

- Express and purify designed binders.

- Assess binding using biophysical methods (SPR, ITC).

- Evaluate functional effects in cellular assays.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools and Databases for Studying Conformational Ensembles

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATLAS | MD Database | Comprehensive simulations of ~2000 representative proteins | https://www.dsimb.inserm.fr/ATLAS [1] |

| GPCRmd | Specialized MD Database | MD simulations for GPCR family proteins | https://www.gpcrmd.org/ [1] |

| MemProtMD | MD Database | Membrane protein simulations and folding data | https://memprotmd.bioch.ox.ac.uk/ [1] |

| SARS-CoV-2 DB | MD Database | Simulation trajectories of coronavirus proteins | https://epimedlab.org/trajectories [1] |

| mdciao | Analysis Tool | Analysis and visualization of MD contact frequencies | https://github.com/gph82/mdciao [7] |

| FiveFold | Ensemble Method | Consensus conformational ensemble generation | Methodology described in [4] |

| RFdiffusion | Design Tool | AI-based binder design for disordered proteins | Baker Lab tools [3] |

| GROMACS | MD Engine | Molecular dynamics simulation software | Open-source package [1] |

| AMBER | MD Engine | Molecular dynamics with force fields | Academic licensing [1] |

| OpenMM | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulation | Open-source package [1] |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The shift to dynamic conformational ensembles has profound implications for drug discovery:

Expanding the Druggable Proteome

Approximately 80% of human proteins remain "undruggable" by conventional methods, largely because many challenging targets require therapeutic strategies that account for conformational flexibility and transient binding sites [4]. Ensemble-based approaches enable targeting of:

- Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Comprising approximately 30-40% of the human proteome, IDPs play crucial roles in cellular processes and disease states but have been largely inaccessible to traditional drug discovery [4].

- Protein-Protein Interaction Interfaces: Often involve dynamic and transient contacts that can be targeted by conformation-specific binders [5].

- Allosteric Sites: Ensemble methods can reveal cryptic allosteric pockets that emerge during conformational transitions [4].

Case Study: Targeting Neurodegenerative Disease Proteins

The intrinsically disordered protein tau has been implicated in Alzheimer's disease pathology. Ensemble-based binder design approaches have shown promise in disrupting tau's damaging aggregation:

- Flexible Binder Design: Using RFdiffusion to design binders that target tau's amino acid sequence rather than a specific conformation [3].

- Enveloping Binders: Creating binders that form their own pockets for the target to fit into, particularly effective for sequences that don't favor specific secondary structures [3].

- Aggregation Disruption: Designed binders can prevent or redirect pathological aggregation pathways [3].

Precision Medicine Applications

Ensemble methods facilitate structure-based drug design that accounts for genetic variations:

- Mutation Impact Analysis: Understanding how coding mutations alter conformational landscapes and drug binding [5].

- Personalized Therapeutics: Designing drugs that target specific conformational subpopulations relevant to individual patients [4].

- Drug Resistance Mechanisms: Studying how mutations in drug target proteins alter their conformational dynamics and binding sites [5].

Future Perspectives

The field of protein dynamics research is rapidly evolving with several promising directions:

- Integration of Experimental and Computational Methods: Combining cryo-EM, NMR, and MD simulations with AI-based predictions to validate and refine ensemble models [6].

- Timescale Resolution: Developing methods to capture dynamics across broader timescales, from femtosecond bond vibrations to second-scale conformational changes.

- Multi-Scale Modeling: Bridging atomic-level simulations with cellular-scale processes to understand protein function in physiological contexts.

- Automated Workflows: Creating end-to-end pipelines from sequence to dynamic ensemble with minimal user intervention.

The ongoing transformation from static structures to dynamic conformational ensembles represents a paradigm shift in structural biology with far-reaching implications for understanding biological function and developing novel therapeutics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe the intricate dance of atoms in proteins and other biomolecules over time. At the heart of every MD simulation lies the force field—a mathematical representation of the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates. Force fields, combined with Newton's laws of motion, create the engine that drives atomic-level simulations, making it possible to study complex biological processes like protein folding that occur on timescales inaccessible to direct experimental observation.

This application note examines the fundamental principles of force fields and their interplay with Newtonian mechanics within the specific context of protein folding research. We provide researchers and drug development professionals with a practical framework for understanding, selecting, and applying modern force fields, supported by structured data comparisons, implementation protocols, and visualization tools.

Theoretical Foundation: Force Fields and Newton's Laws

The Mathematical Formalism of Force Fields

Classical force fields decompose the potential energy of a system into individual contributions from bonded and non-bonded interactions, with the general form:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E{\text{non-bonded}} = E{\text{bonds}} + E{\text{angles}} + E{\text{torsions}} + E{\text{electrostatic}} + E{\text{van der Waals}} ]

This additive approach [8] allows for computationally efficient energy and force calculations while capturing the essential physics of molecular interactions. The gradient of this potential energy function yields the forces acting on individual atoms, which according to Newton's second law ((F = ma)), determines their acceleration [8].

Newtonian Mechanics in Molecular Dynamics

MD simulations numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion to trace the trajectory of atoms over time. The standard computational algorithm follows this sequence:

- Calculate forces on all atoms: (Fi = -\nabla E{\text{total}}(r_i))

- Compute accelerations: (ai = Fi/m_i)

- Update velocities: (vi(t + \Delta t/2) = vi(t - \Delta t/2) + a_i(t)\Delta t)

- Update positions: (ri(t + \Delta t) = ri(t) + v_i(t + \Delta t/2)\Delta t)

This integration cycle, typically using a time step of 1-2 femtoseconds, repeats millions of times to simulate biologically relevant timescales, generating trajectories that reveal protein folding pathways, conformational changes, and binding events.

Current Force Fields for Protein Folding Research

Additive versus Polarizable Force Fields

Most traditional force fields employ an additive approximation where the electrostatic environment remains constant, but the next major advancement involves incorporating electronic polarizability to better represent electrostatic interactions in varying dielectric environments [8].

Additive force fields like AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS-AA use fixed atomic partial charges and have reached a mature state after 35 years of development [8]. The CHARMM additive all-atom force field has recently been updated to the C36 version, featuring a new backbone CMAP potential optimized against experimental data on small peptides and folded proteins, along with new side-chain dihedral parameters [8]. Similarly, the AMBER force field family has seen continuous improvement, with variants including ff99SB, ff99SB-ILDN, ff99SB-ILDN-Phi, and others introducing modifications to backbone potentials and side-chain torsions [8].

Polarizable force fields like the CHARMM Drude model and AMOEBA represent the next generation of force fields by explicitly accounting for electronic polarization. In the Drude model, this is achieved by attaching a charged "Drude particle" to each atom via a harmonic spring, representing the electronic degrees of freedom [8]. Development of the Drude polarizable force field began in 2001, with parameters now available for various biomolecules and functional groups [8].

Recent Advances and Balanced Force Fields

A significant challenge in modern force field development has been creating balanced parameterizations that simultaneously describe folded domains accurately while capturing the properties of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). Recent refinements have focused on optimizing protein-water interactions and torsional parameters.

Two refined Amber force fields demonstrate this balanced approach: ff03w-sc incorporates selective upscaling of protein-water interactions, while ff99SBws-STQ′ includes targeted torsional refinements for glutamine residues to correct overestimated helicity in polyglutamine tracts [9]. Extensive validation against NMR and SAXS data shows that both force fields accurately reproduce IDP dimensions and secondary structure propensities while maintaining folded protein stability [9].

Table 1: Major Protein Force Field Families and Their Characteristics

| Force Field Family | Key Variants | Special Features | Applicability to Protein Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | ff99SB, ff14SB, ff19SB, ff03ws, ff99SB-disp [8] [9] | Extensive torsional parameter optimization; variants available with different water models | Balanced performance for folded and disordered proteins with recent variants |

| CHARMM | CHARMM22*, CHARMM36, CHARMM36m [8] [9] | CMAP corrections for backbone; balanced LJ parameters | Good for folded proteins; CHARMM36m improved for IDPs |

| CHARMM Drude | 2013, 2016, 2019 versions [8] | Polarizable force field; explicit electronic degrees of freedom | Improved dielectric response; better for heterogeneous environments |

| AMOEBA | 2010, 2013, 2017 versions [8] | Polarizable force field; atomic multipoles | Accurate electrostatics; computationally demanding |

| GROMOS | 53A6, 54A7, 54A8 [8] | Unified atom approach; parameterized against thermodynamic data | Good for folded proteins; less common for IDPs |

| OPLS-AA | OPLS-AA, OPLS-AA/M [8] | Optimized for liquid properties; transferable | Reasonable for folded proteins |

Machine Learning Force Fields

Machine-learned force fields represent a paradigm shift, enabling direct construction of flexible molecular force fields from high-level ab initio calculations. The symmetrized gradient-domain machine learning (sGDML) approach incorporates spatial and temporal physical symmetries to construct force fields with quantum-chemical CCSD(T) level of accuracy, allowing converged MD simulations with fully quantized electrons and nuclei [10].

This approach solves the accuracy and molecular size dilemma by reducing problem complexity through data-driven discovery of relevant physical symmetries and enhancing information content through exercise of static and dynamic symmetries [10]. While currently limited to smaller molecules, this technology promises spectroscopic accuracy in future molecular simulations.

Quantitative Comparison of Modern Force Fields

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Force Fields for Protein Folding Applications

| Force Field | Water Model | Folded Protein Stability | IDP Dimensions | Secondary Structure Propensity | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ff99SB-ILDN [8] | TIP3P, TIP4P-D | Good (some over-stabilization) | Overly collapsed [9] | Balanced with TIP4P-D | General use with modified water models |

| CHARMM36m [9] | Modified TIP3P | Good | Accurate for many IDPs | Slight overpopulation of helices | Systems with folded and disordered regions |

| ff99SB-disp [9] | TIP4P-D | Very good | Accurate (slight overexpansion) [9] | Accurate | Balanced simulations; IDP studies |

| ff03ws [9] | TIP4P/2005 | Moderate (instability in long simulations) [9] | Accurate for most IDPs | Accurate | IDP studies with caution for folded domains |

| ff03w-sc [9] | TIP4P/2005 | Good (improved over ff03ws) [9] | Accurate | Accurate | Balanced systems (folded + disordered) |

| DES-Amber [9] | TIP4P/2005 | Good | Slightly compact | Accurate | Protein-protein interactions |

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation in Protein Folding

Protocol 1: Assessment of Folded Protein Stability

Purpose: To evaluate a force field's ability to maintain the native structure of folded proteins over microsecond timescales.

Materials:

- Reference protein structures (e.g., Ubiquitin PDB: 1D3Z, Villin HP35 PDB: 2F4K)

- MD software (e.g., NAMD [8], GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM [8])

- Solvation system (appropriate water model, ions for physiological concentration)

Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Obtain protein coordinates from the Protein Data Bank

- Solvate in a water box with at least 10 Å padding from protein edges

- Add ions to neutralize system and achieve 150 mM NaCl concentration

Equilibration:

- Energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm (5,000 steps)

- Solvent equilibration with protein heavy atoms restrained (100 ps, NVT ensemble)

- System equilibration with decreasing position restraints (100 ps each, NPT ensemble)

Production Simulation:

- Run multiple independent simulations (≥ 2.5 μs each) without restraints

- Maintain temperature at 300 K using Langevin dynamics or Nosé-Hoover thermostat

- Maintain pressure at 1 atm using Langevin piston or Parrinello-Rahman barostat

Analysis:

- Calculate backbone root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from native structure

- Compute root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residues

- Monitor secondary structure content using DSSP or STRIDE

- Identify unfolding events through visual inspection and hydrogen bond analysis

Expected Outcomes: Stable force fields (e.g., ff99SBws) maintain RMSD < 0.2 nm, while problematic ones (e.g., ff03ws) show significant deviations (> 0.4 nm) and local unfolding [9].

Protocol 2: Characterization of Intrinsically Disordered Protein Ensembles

Purpose: To validate force field performance for disordered proteins against experimental NMR and SAXS data.

Materials:

- IDP sequences of interest (e.g., ACTR, RS peptide, α-synuclein)

- Experimental data (NMR chemical shifts, scalar couplings, SAXS profiles)

- Enhanced sampling capabilities (temperature replica-exchange, metadynamics)

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Build extended initial structures of IDP sequences

- Solvate in appropriate water box with ions

- Energy minimization and equilibration as in Protocol 1

Enhanced Sampling:

- Implement temperature replica-exchange MD (T-REMD) with 24-48 replicas

- Temperature range: 300-500 K exponentially spaced

- Attempt replica exchanges every 1-2 ps

- Aggregate data from all replicas using reweighting procedures

Ensemble Analysis:

- Calculate NMR chemical shifts from structures using SHIFTX or CAMSHIFT

- Compute 3J-coupling constants from dihedral angles

- Calculate SAXS profiles using CRYSOL or FOXS

- Determine radius of gyration (Rg) and end-to-end distance distributions

Validation:

- Compare calculated and experimental NMR parameters (chemical shifts, J-couplings)

- Compare calculated and experimental SAXS profiles using χ²

- Assess ensemble properties against single-molecule FRET data if available

Expected Outcomes: Balanced force fields should reproduce experimental Rg values within error margins and accurately capture secondary structure propensities without artificial overcollapse or expansion [9].

Protocol 3: Analysis of Folding Pathways and Transition States

Purpose: To characterize protein folding mechanisms and compare with theoretical models using transition path analysis.

Materials:

- Fast-folding proteins (e.g., Villin headpiece, WW domain)

- High-performance computing resources for multiple long simulations

- Analysis tools for transition path identification

Methodology:

- Simulation Setup:

- Prepare both folded and unfolded initial structures

- Run multiple independent simulations (10-100) starting from different configurations

- Use appropriate enhanced sampling if needed to observe folding events

Transition Path Identification:

- Monitor reaction coordinate Q (native contacts fraction) over time

- Identify transition paths as segments where Q crosses from unfolded (<0.2) to folded (>0.89) values without returning [11]

- Rescale transition path times from 0 to 1 for comparison

Mechanism Analysis:

- Count native segments (contiguous native residues >3-5) along transition paths

- Calculate formation times for different structural elements

- Identify common folding nuclei and critical contacts

Comparison with Theoretical Models:

- Construct Ising-like models based on native contact maps [11]

- Compare distribution of folding mechanisms between MD and model

- Test key assumptions (e.g., native-centricity, limited nucleation sites)

Expected Outcomes: MD simulations of villin headpiece show folding proceeds with structure formation in only a few regions of the sequence, supporting the fundamental assumptions of simplified Ising-like theoretical models [11].

Visualization and Analysis of Folding Mechanisms

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for Protein Folding Simulations

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Protein Folding MD Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | AMBER ff19SB [9], CHARMM36m [9], ff99SB-disp [9] | Provides energy function for molecular interactions | Balance between folded stability and IDP accuracy; water model compatibility |

| Water Models | TIP3P [8], TIP4P/2005 [9], TIP4P-D [9], OPC [9] | Solvation environment; impacts protein-water interactions | Critical for balancing protein-protein vs. protein-solvent interactions |

| MD Software Packages | NAMD [8], GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM [8] | Engine for running simulations with Newton's laws | Performance, scalability, force field compatibility, analysis tools |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Replica-Exchange MD, Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling | Accelerates conformational sampling | Required for observing folding events in accessible simulation times |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, VMD, MDAnalysis, GROMACS tools | Trajectory analysis, visualization, quantification | RMSD, RMSF, secondary structure, contact analysis, clustering |

| Validation Databases | PDB [9], NMR chemical shifts [9], SAXS profiles [9] | Experimental data for force field validation | Essential for assessing real-world predictive power |

Force fields serve as the essential engine of molecular dynamics simulations, transforming Newton's fundamental laws of motion into a powerful tool for investigating protein folding. The ongoing development of balanced force fields that accurately describe both folded and disordered states represents a significant achievement in the field, though challenges remain in perfectly capturing the balance of molecular interactions across diverse protein systems.

Future directions include the continued refinement of polarizable force fields like Drude and AMOEBA, the incorporation of machine-learned potentials with quantum-level accuracy, and the development of next-generation water models that better represent aqueous environments. For researchers studying protein folding and designing therapeutic interventions, careful selection of appropriate force fields combined with rigorous validation against experimental data remains crucial for generating biologically meaningful insights from molecular simulations.

The study of protein folding—the process by which a polypeptide chain attains its functional three-dimensional structure—represents one of the fundamental challenges in molecular biology [12]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational technique to probe this process at atomic resolution, providing insights that complement experimental approaches [13]. The core challenge in MD simulations has historically been the timescale gap between processes accessible to simulation and those relevant to biological folding. While many proteins fold on timescales ranging from microseconds to seconds, all-atom MD simulations were traditionally limited to nanoseconds or microseconds [12] [14].

This application note traces the methodological evolution that has expanded MD simulations from picosecond-scale observations to millisecond-scale investigations, with a specific focus on applications in protein folding research. We document key computational breakthroughs that have bridged this timescale gap, enabling researchers to study folding pathways, intermediates, and kinetics with unprecedented detail. The progression from straightforward molecular dynamics to advanced sampling techniques and Markov state modeling has fundamentally transformed our ability to connect simulation with experimental folding data [14] [15].

For structural biologists and computational scientists, this evolution has opened new avenues for investigating complex folding phenomena in large proteins and multidomain systems, which comprise the majority of proteins but remain less understood than their smaller counterparts [15]. The protocols and methodologies detailed herein provide a toolkit for researchers aiming to apply these advanced MD techniques to their protein folding studies.

Methodological Evolution and Key Techniques

Essential Dynamics Sampling (EDS)

The Essential Dynamics Sampling (EDS) technique, introduced in the 1990s and applied to protein folding in the early 2000s, represents an early approach to extend the practical timescale of folding simulations [12]. This method addresses the sampling problem by biasing simulations along collective motions derived from the protein's native state fluctuations.

The fundamental innovation of EDS lies in its use of a configurational subspace defined by a set of generalized coordinates obtained through essential dynamics analysis of an equilibrated trajectory. In standard MD, the conformational sampling efficiency is limited, with even microsecond-length simulations exploring only a small fraction of the available conformational space for systems of biological interest [12]. EDS overcomes this by performing a regular MD simulation but only accepting steps that do not increase the distance from a target structure in this predefined subspace.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Essential Dynamics Sampling of Cytochrome c Folding

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein | Horse heart cytochrome c (104 amino acids) | Well-characterized folding pathway with experimental data for validation [12] |

| Simulation System | Protein solvated in periodic rectangular box (67.90 × 63.27 × 72.26 Å) | Provides physiological-like environment while maintaining computational efficiency |

| Force Field | GROMOS87 with modifications | Standard force field with improved treatment of aromatic rings and hydrogen atoms [12] |

| Water Model | Simple Point Charge (SPC) | Compatible with GROMOS87 force field |

| Long-range Electrostatics | Particle-Mesh Ewald method | Accurate treatment of electrostatic interactions in periodic system |

| Constraints | SHAKE algorithm for all bond lengths | Enables 2 fs timestep for numerical integration |

| Essential Dynamics Vectors | 106 generalized degrees of freedom (from 312 Cα eigenvectors) | Captures essential collective motions while reducing computational dimensionality |

The EDS protocol involves two complementary procedures: an expansion procedure to increase the distance from a reference structure (effectively unfolding the protein), and a contraction procedure to decrease this distance (refolding the protein) [12]. This approach allowed researchers to simulate the folding of cytochrome c starting from structures with root-mean-square deviations of approximately 20 Å from the crystal structure, achieving correct folding using only a fraction of the full conformational degrees of freedom [12].

Markov State Models (MSMs)

Markov State Models (MSMs) represent a paradigm shift in MD timescale extension, moving from continuous trajectories to a discrete-state continuous-time framework that can integrate data from multiple simulations. The MSMBuilder2 software, described in 2011, provides a high-performance implementation of this approach, validated on dynamics ranging from picoseconds to milliseconds [14].

Unlike EDS, which biases simulations along predefined coordinates, MSMs use many short, unbiased simulations to statistically reconstruct long-timescale dynamics. The fundamental assumption is that the molecular system can be described as a Markov process on a discretized state space, where the probability of transitioning between states depends only on the current state, not on previous history.

Table 2: MSMBuilder2 Protocol for Protein Folding Analysis

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Generation | Run multiple short, unbiased MD simulations from different starting structures | Ensure adequate sampling of diverse conformational regions |

| 2. Feature Selection | Choose relevant structural parameters (e.g., dihedral angles, contact maps) | Features should capture essential aspects of protein folding |

| 3. Clustering | Group similar conformations into microstates | Cluster quality significantly impacts model accuracy |

| 4. Model Construction | Build transition probability matrix between states | Use robust counting procedures to estimate transition probabilities |

| 5. Model Validation | Test kinetic and equilibrium predictions | Compare implied and actual timescales; check Chapman-Kolmogorov test |

| 6. Analysis | Identify metastable states, pathways, and rates | Extract physically meaningful insights from the model |

The power of the MSM approach lies in its ability to integrate data from multiple simulation techniques (including both all-atom and simplified models) and its natural connection to experimental observables such as relaxation rates and population distributions [14]. This framework has been particularly valuable for characterizing complex folding pathways with multiple intermediates and for studying the folding of larger proteins that exceed the practical limits of continuous MD approaches.

All-Atom Structure-Based Models

While coarse-grained approaches like EDS and MSMs extend accessible timescales, all-atom simulations remain essential for capturing atomic-level details of folding mechanisms, including the effects of specific mutations and chemical environments. Recent advances have made all-atom folding simulations of larger proteins increasingly practical [15].

All-atom structure-based models incorporate varying degrees of native-centric bias while maintaining atomic resolution. These methods range from purely structure-based Gō models, which emphasize the native topology, to all-atom simulations with explicit solvent that include full side-chain chemistry [15]. The application of these approaches to serpins and other large proteins has demonstrated their ability to provide critical, detailed information on folding free energy landscapes, intermediates, and pathways [15].

These synergistic computational approaches have proven particularly valuable for interpreting experimental folding data, designing new folding experiments, and testing the effects of mutations and small molecules on folding [15]. When combined with experimental techniques such as hydrogen exchange, fluorescence, and NMR, all-atom simulations can provide atomic-resolution insights into folding mechanisms [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Essential Dynamics Sampling for Protein Folding

This protocol outlines the application of EDS to simulate protein folding, based on the approach used for cytochrome c folding [12].

System Setup and Equilibrium MD

- Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain the native structure from the Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB 1hrc for cytochrome c). Process the structure to add missing atoms, hydrogen atoms, and correct protonation states.

- Solvation and Minimization: Solvate the protein in a rectangular water box with at least 10 Å buffer between the protein and box edges. Add ions to neutralize the system. Perform energy minimization using steepest descent until convergence (Fmax < 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Equilibration: Run equilibrium MD simulation at 300 K for at least 160 ps to ensure proper system equilibration. Use a timestep of 2 fs with constraints on all bonds using the SHAKE algorithm. Maintain constant temperature using an isokinetic temperature coupling scheme.

Essential Dynamics Analysis

- Trajectory Analysis: From the equilibrated portion of the trajectory (after 160 ps), extract the coordinates of Cα atoms at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 ps).

- Covariance Matrix Construction: Build the covariance matrix of positional fluctuations for the Cα atoms (matrix order 312 for a 104-residue protein).

- Diagonalization: Diagonalize the covariance matrix to obtain eigenvectors (representing concerted motions) and eigenvalues (representing mean-square fluctuations along each direction).

- Vector Selection: Sort eigenvectors by eigenvalue and select a subset for the EDS procedure (e.g., 106 vectors accounting for the most significant collective motions).

Essential Dynamics Sampling

- Reference Structure: Define the native structure as the reference for distance calculations.

- Distance Calculation: For each MD step, calculate the distance between the current structure and the reference in the chosen subspace defined by the selected eigenvectors.

- Step Acceptance Criterion:

- For contraction procedure (folding): Accept the step if it does not increase the distance from the reference.

- For expansion procedure (unfolding): Accept the step if it does not decrease the distance from the reference.

- Projection: If a step violates the acceptance criterion, project the coordinates and velocities radially onto the hypersphere centered at the reference, with radius equal to the distance in the previous step.

- Multiple Trajectories: Perform multiple independent folding simulations starting from different unfolded structures to assess pathway variability.

Protocol: Markov State Model Construction

This protocol describes the construction of Markov State Models for protein folding analysis using approaches implemented in MSMBuilder2 [14].

Data Generation and Preparation

- Simulation Strategy: Run hundreds to thousands of short MD simulations (nanoseconds to microseconds) starting from diverse conformations, including unfolded states, partially folded intermediates, and the native state.

- Conformation Storage: Save molecular coordinates at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) to capture dynamics at appropriate temporal resolution.

- Feature Selection: Calculate features that capture essential aspects of protein structure, such as:

- Backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ)

- Contact maps between residues

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from reference structures

- Secondary structure elements

State Space Discretization

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply time-lagged independent component analysis (tICA) or principal component analysis (PCA) to identify slow collective variables.

- Clustering: Use k-means clustering or k-centers clustering to group similar conformations into microstates (typically 100-10,000 states). Ensure that the clustering captures structural diversity while maintaining Markovianity at the chosen lag time.

Model Construction and Validation

- Transition Matrix Estimation: Count transitions between states at a specified lag time (τ) to construct a count matrix. Apply Bayesian estimation or maximum likelihood methods to convert counts to transition probabilities.

- Lag Time Optimization: Test different lag times and select the minimum lag time where the implied timescales become approximately constant (validating Markovian behavior).

- Model Validation:

- Chapman-Kolmogorov Test: Compare predicted and observed state populations at multiple times.

- Eigenvalue Spectrum: Check that the first few eigenvalues are separated from the rest.

- Experimental Comparison: Validate against experimental data such as folding rates and intermediate populations.

Model Analysis

- Pathway Identification: Compute committor probabilities between states to identify folding pathways and transition states.

- Free Energy Landscape: Calculate free energies from stationary probabilities of states.

- Rate Calculation: Extract folding and unfolding rates from the eigenvalues of the transition matrix.

Visualization and Workflows

EDS Folding Simulation Workflow

MSM Construction Pipeline

Multi-scale MD Integration Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Protein Folding Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Protein Folding |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software Package | High-performance molecular dynamics | Production MD simulations with various force fields; used in EDS studies [12] |

| GROMOS87 | Force Field | Molecular mechanics parameters | Describes atomic interactions; modified for improved protein folding simulations [12] |

| MSMBuilder2 | Software Package | Markov State Model construction | Modeling conformational dynamics from picoseconds to milliseconds [14] |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | Protein structure prediction | Generating starting models for proteins without resolved structures [16] |

| Robetta | Modeling Server | De novo protein structure prediction | Alternative to AF2 for constructing initial protein models [16] |

| I-TASSER | Modeling Platform | Template-based structure prediction | Automated template identification and structure assembly [16] |

| trRosetta | Prediction Server | Deep neural network structure prediction | Predicts inter-residue geometries for structure construction [16] |

| SHAKE Algorithm | Constraint Method | Bond length constraints | Enables longer timesteps by constraining bond vibrations [12] |

| Particle-Mesh Ewald | Electrostatics Method | Long-range electrostatic treatment | Accurate calculation of electrostatic interactions in periodic systems [12] |

| Simple Point Charge (SPC) | Water Model | Solvent representation | Compatible water model for protein folding simulations [12] |

The evolution of molecular dynamics from picosecond to millisecond timescales has fundamentally transformed our ability to study protein folding computationally. The synergistic development of biased sampling techniques like Essential Dynamics Sampling, statistical approaches like Markov State Models, and increasingly accurate all-atom simulations has created a powerful multi-scale toolkit for researchers [12] [14] [15].

These methodological advances have narrowed the historical gap between simulation and experiment, enabling direct comparison with and interpretation of experimental folding data [13]. For drug development professionals, these tools provide unprecedented atomic-level insights into folding pathways that can inform therapeutic strategies targeting protein misfolding diseases. For researchers studying complex biological systems, the integration of these computational approaches with experimental techniques creates new opportunities to understand how large, multidomain proteins attain their functional structures [15].

As these methods continue to evolve, we anticipate further convergence of computational and experimental approaches, ultimately leading to more predictive models of protein folding that can be applied to diverse challenges in structural biology and therapeutic development.

The protein folding problem represents one of the major challenges in molecular biology, seeking to explain how an amino acid sequence determines a protein's 3D native structure and how this process occurs so rapidly despite a vast number of possible conformations [17]. The folding funnel hypothesis provides a powerful conceptual framework that addresses these questions by visualizing protein folding through an energy landscape perspective [18]. This theory posits that a protein's native state corresponds to its free energy minimum under physiological conditions, with the depth of the funnel representing the energetic stabilization of the native state and the width representing the conformational entropy of the system [17].

In this landscape, the y-axis represents the internal free energy of a protein—the sum of hydrogen bonds, ion-pairs, torsion angle energies, hydrophobic and solvation free energies—while the multiple x-axes represent the conformational structures [17]. Unlike simple chemical reactions that follow a single pathway, folding is a transition from disorder to order, with the funnel concept emphasizing parallel processes and ensembles rather than a strictly linear sequence of intermediates [17]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide the computational toolkit to explore this theoretical framework, offering atomistic insights into folding pathways, intermediate states, and the kinetics of the folding process.

MD Approaches to Sampling the Energy Landscape

Molecular dynamics simulations face significant challenges in studying protein folding due to the conformational sampling efficiency problem; even microsecond-long simulations may explore only a small fraction of the available conformational space [12]. Several specialized MD techniques have been developed to overcome these limitations, each with distinct methodological approaches for sampling the folding funnel.

Table 1: Molecular Dynamics Methods for Studying Protein Folding

| Method | Key Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Essential Dynamics Sampling (EDS) [12] | Biases simulation along collective coordinates defined by essential dynamics; accepts steps not increasing distance from target | Folding of cytochrome c from unfolded structures (~20 Å RMSD) using backbone collective motions | Requires prior ED analysis; projection may introduce artifacts |

| Targeted Molecular Dynamics [12] | Applies time-dependent harmonic restraints to decrease all-atom RMSD from native state | Calculating reaction paths between conformations | May introduce non-physical forces; pathway bias |

| High-Temperature Unfolding [12] | Unfolds from native state under denaturing conditions (high temperature) | Studying unfolding pathways and stability | Reverse process may not match folding; temperature artifacts |

| Biased-Sampling Free-Energy [12] | Combines high-temperature unfolding with free energy calculations along path | Calculating folding free energies at 300 K along predetermined paths | Computationally intensive; dependent on unfolding path accuracy |

| BioEmu (Diffusion Models) [19] | Uses denoising diffusion on AlphaFold2 representations to sample equilibrium distributions | Rapid sampling of protein conformational ensembles (10,000 structures in hours on GPU) | Approximate equilibrium; dependent on training data |

The EDS technique is particularly noteworthy for its application to cytochrome c folding [12]. In this method, a standard MD simulation is performed at each step, but only those steps not increasing the distance from a target structure are accepted. The distance calculation occurs in a configurational subspace defined by generalized coordinates obtained from an essential dynamics analysis of an equilibrated trajectory. This approach enabled correct folding of cytochrome c starting from structures with ~20 Å RMSD from the crystal structure using only 106 generalized degrees of freedom focused on backbone carbon motions, without containing explicit information on side chains [12].

The folding pathways revealed by EDS simulations of cytochrome c demonstrated agreement with experimental data, showing an early collapse of the main chain structure followed by secondary structure formation [12]. This mirrors experimental observations from fluorescence, time-resolved circular dichroism, and small-angle x-ray scattering that identified two folding intermediates with ~0.5-ms and ~7-ms lifetimes [12].

Protocol: Essential Dynamics Sampling for Protein Folding

The following protocol outlines the EDS method as applied to cytochrome c folding, which successfully generated native structures from unfolded starting points [12].

System Preparation and Equilibration

- Initial Structure Acquisition: Obtain the crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., PDB entry 1hrc for horse heart cytochrome c).

- Solvation: Solvate the protein in a periodic rectangular water box (e.g., dimensions 67.90 × 63.27 × 72.26 Å for cytochrome c) using explicit water models such as SPC.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes and bad contacts.

- Equilibration MD: Conduct an unrestrained molecular dynamics simulation at the target temperature (300 K) for sufficient time to achieve equilibrium (e.g., 2.66 ns total, discarding the first 160 ps as equilibration).

Essential Dynamics Analysis

- Covariance Matrix Construction: From the equilibrated trajectory, build the covariance matrix of positional fluctuations for the Cα carbon atoms (order 312 for a 104-residue protein).

- Diagonalization: Diagonalize the covariance matrix to obtain eigenvectors (representing directions of concerted motions) and eigenvalues (representing mean-square positional fluctuations for each direction).

- Eigenvector Sorting: Sort eigenvectors according to their corresponding eigenvalues in descending order.

Essential Dynamics Sampling Simulation

- Generate Unfolded Structures: Use EDS in expansion mode at 300 K, utilizing all native eigenvectors (excluding the last six eigenvectors representing overall rototranslation) to produce starting unfolded structures with high RMSD from native (~20 Å).

- Define Subspace for Folding: Select a subset of eigenvectors for the contraction procedure (e.g., eigenvectors 1-100, 101-200, or 201-306 for cytochrome c) to calculate the distance from the target structure.

- Perform Biased Sampling: For each MD step:

- Perform a regular MD simulation.

- Calculate the distance between the current structure and the reference structure in the chosen subspace.

- Accept the step if the distance does not increase (contraction procedure).

- If the distance increases, project coordinates and velocities radially onto the hypersphere centered in the reference, with radius given by the distance from the reference in the previous step.

- Repeat: Continue until structures converge to native-like configurations (low RMSD).

Table 2: Simulation Parameters for EDS Folding Protocol

| Parameter | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Software | GROMACS | Molecular dynamics engine |

| Force Field | GROMOS87 with modifications | Energy calculations |

| Water Model | SPC (Simple Point Charge) | Solvation effects |

| Bond Treatment | SHAKE algorithm | Constrain all bond lengths |

| Electrostatics | Particle-Mesh Ewald | Long-range interactions |

| Timestep | 2 fs | Numerical integration |

| Temperature Coupling | Isokinetic | Maintain constant temperature |

| Nonbond Cutoff | 9.0 Å | Short-range interactions |

Protocol: Targeted MD and Advanced Sampling

Targeted Molecular Dynamics

- System Setup: Prepare the system as described in Section 3.1.

- Restraint Application: Apply time-dependent harmonic restraints on each atom that continuously decrease the all-atom RMSD from the native state.

- Simulation: Run MD simulation while these restraints guide the protein toward the native conformation.

BioEmu for Rapid Ensemble Sampling

For researchers needing to sample thousands of structures rapidly, the BioEmu biomolecular emulator provides an alternative approach [19]:

- Input Generation: Use AlphaFold2's evoformer to generate single and pair representations of the input protein sequence.

- Diffusion Sampling: Employ a denoising diffusion model to generate protein structures through 30-50 denoising steps.

- Ensemble Construction: Sample approximately 10,000 independent protein structures within minutes to hours on a single GPU.

This method is particularly valuable for studying protein dynamics and equilibrium distributions at scale, though it provides approximate rather than physically precise trajectories [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Protein Folding Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [12] | MD Software Package | High-performance molecular dynamics | Primary simulation engine for folding trajectories |

| GROMOS87 Force Field [12] | Molecular Mechanics | Energy calculations and atomic interactions | Physical basis for interatomic forces |

| Particle-Mesh Ewald [12] | Electrostatics Method | Accurate treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions | Essential for solvated systems |

| AlphaFold2 Evoformer [19] | Deep Learning Network | Generates sequence representations from input protein sequences | Input generation for BioEmu emulator |

| Distributional Graphormer (DiG) [19] | Neural Network Architecture | Backbone for denoising diffusion model | Core of BioEmu structure sampling |

| Essential Dynamics [12] | Analysis Method | Identifies collective motions from covariance matrix | Defines subspace for EDS sampling |

| SHAKE Algorithm [12] | Constraint Algorithm | Constrains all bond lengths during simulation | Enables 2 fs timestep for numerical integration |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Metrics for Folding Analysis

Table 4: Key Observables for Characterizing Folding Pathways

| Observable | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Experimental Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | Root-mean-square deviation of atomic positions | Progress toward native structure; lower values indicate more native-like configurations | Crystal structure validation |

| Radius of Gyration | Mass-weighted root-mean-square distance of atoms from center of mass | Compactness; decrease indicates hydrophobic collapse | SAXS measurements [12] |

| Native Contacts | Percentage of residue-residue contacts present in native structure | Formation of correct tertiary structure | Hydrogen-deuterium exchange |

| Free Energy Profile | From probability distributions along reaction coordinates | Energy barriers and intermediate stability | Folding cooperativity measurements |

| Secondary Structure Content | DSSP or similar algorithm | Formation of α-helices and β-sheets | Circular dichroism spectroscopy [12] |

Analysis of EDS simulations for cytochrome c revealed folding pathways consistent with experimental observations, including an early collapse phase followed by concerted secondary structure formation and side-chain packing [12]. The simulation successfully reproduced the presence of multiple folding intermediates and identified potential kinetic traps where frustrated topologies could slow the folding process, mirroring experimental fluorescence energy transfer studies that showed only a small fraction of collapsed structures correctly fold [12].

The integration of molecular dynamics with folding funnel theory provides powerful insights for drug development, particularly in understanding diseases of protein misfolding such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and prion disorders. By identifying kinetic traps and frustrated states along the folding pathway, researchers can target therapeutic interventions to prevent accumulation of toxic aggregates or stabilize native conformations.

The folding funnel concept explains how proteins navigate the complex energy landscape to achieve their functional native states. Molecular dynamics simulations, particularly advanced sampling methods like EDS, provide the computational microscope to observe these processes at atomistic resolution. As MD methodologies continue to evolve alongside emerging AI-based approaches like BioEmu, researchers are gaining increasingly powerful tools to decode the relationship between protein sequence, structure, and folding dynamics—with profound implications for both basic science and pharmaceutical development.

Advanced MD Techniques and Their Impact on Drug Discovery and Beyond

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, particularly in the study of protein folding, a central challenge is the timescale disparity between biologically relevant events and computationally feasible simulation lengths. Protein folding processes occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales, while all-atom explicit solvent MD simulations typically access nanoseconds to microseconds, creating a significant sampling gap [20]. This limitation often leaves simulations trapped in local energy minima, unable to observe complete folding pathways or adequately sample conformational space.

Enhanced sampling methods have emerged as powerful computational strategies to overcome these energy barriers and accelerate rare events. Among these, metadynamics and parallel tempering have proven particularly effective for studying complex biomolecular processes like protein folding. These techniques, especially when combined in hybrid approaches such as parallel tempering metadynamics, enable researchers to explore free energy landscapes, identify folding intermediates, and predict folding mechanisms with atomic-level resolution that often eludes experimental techniques [21] [22] [23].

Theoretical Foundations

Metadynamics

Metadynamics is an enhanced sampling method that accelerates the exploration of conformational space by adding a history-dependent bias potential to the system's Hamiltonian. This bias is constructed as a sum of repulsive Gaussian potentials deposited along selected collective variables (CVs) – low-dimensional descriptors that capture the essential dynamics of the process being studied [21] [22].

In well-tempered metadynamics, the most common variant today, the bias potential ( V(s,t) ) is defined by:

[ V(s,t) = \omega \sum{t'=0}^{t} \exp\left(-\frac{V(s,t')}{kB\Delta T}\right) \exp\left(-\frac{(s-s(t'))^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) ]

where ( \omega ) is the initial Gaussian height, ( \sigma ) determines Gaussian width, ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant, and ( \Delta T ) is a parameter that controls how quickly the bias potential converges [22]. The bias potential systematically "fills" free energy minima, encouraging the system to escape local minima and explore new regions of conformational space while simultaneously providing an estimate of the underlying free energy landscape.

Parallel Tempering

Parallel tempering (also known as replica exchange) addresses the sampling problem by simulating multiple copies (replicas) of the system at different temperatures [22] [24]. The replicas are evolved independently, with occasional swaps between configurations at adjacent temperatures based on a Metropolis criterion:

[ P(swap) = \min\left(1, \exp\left[(\betai - \betaj)(Ui - Uj)\right]\right) ]

where ( \beta = 1/k_BT ) and ( U ) is the potential energy. This approach allows conformations to effectively diffuse from low temperatures (where they might be trapped in local minima) to high temperatures (where barriers are more easily crossed), and back again to low temperatures. The result is significantly improved sampling efficiency, especially for systems with complex, rough energy landscapes like folding proteins [22] [24].

Integration of Methods

The combination of metadynamics with parallel tempering creates a powerful hybrid approach that addresses limitations of both methods. Parallel tempering metadynamics applies metadynamics bias potentials across multiple temperature replicas, overcoming barriers along both the CV space (via metadynamics) and orthogonal degrees of freedom (via temperature exchanges) [21] [22]. This integration is particularly valuable for protein folding, where many relevant motions may not be captured by a small number of predefined CVs.

Table 1: Key Enhanced Sampling Methods for Protein Folding

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metadynamics | History-dependent bias potential along collective variables | Directly reconstructs free energy surfaces; Good for known reaction coordinates | Folding mechanisms; Ligand binding; Conformational changes |

| Parallel Tempering | Multiple temperatures with configuration exchanges | No need to predefine reaction coordinates; Excellent for global sampling | Protein folding; Phase transitions; Complex systems with unknown pathways |

| Parallel Tempering Metadynamics | Combines bias potential with temperature exchanges | Addresses both CV and orthogonal degrees of freedom; Reduces hidden barriers | Complex folding landscapes; Multidomain proteins; Misfolding studies |

Application Notes for Protein Folding

AlphaFold-Derived Collective Variables

A recent innovation in protein folding simulations leverages the distance probability profiles generated by AlphaFold 2 as a basis for constructing collective variables. AlphaFold produces a tensor with dimensions N×N×M (where N is residue count and M is distance bins) containing probabilities for residue-residue distances [21] [25] [26].

This output enables the definition of an AlphaFold-based CV that scores any protein conformation by its compliance with the AlphaFold-predicted distance distributions:

[ CV{AF} = \sum{i=1}^{N} \sum{j=1}^{i-1} D[i,j,\hat{d}{i,j}] ]

where ( D[i,j,\hat{d}{i,j}] ) is the AlphaFold probability for residues i and j being in the distance bin ( \hat{d}{i,j} ) corresponding to their current distance in conformation C [21]. This CV can drive folding simulations toward AlphaFold-predicted native structures while allowing exploration of alternative conformations and folding pathways.

Practical Implementation and Protocols

PTMetaD-WTE Protocol for Protein Folding

The Parallel Tempering Metadynamics in Well-Tempered Ensemble (PTMetaD-WTE) protocol combines multiple enhanced sampling techniques [22]:

System Setup: Prepare the solvated protein system with appropriate counterions. For a tryptophan cage mini-protein, this typically involves ~1,602 TIP3P water molecules with Amber99SB-ILDN force field parameters [21].

Replica Configuration: Set up 16 replicas with temperatures following an exponential distribution (e.g., 300K to 546.6K with k=0.04).

Two-Step Simulation:

- Step 1: Run 20 ns PTMetaD with bias on potential energy (Gaussian height=2 kJ/mol, width=500 kJ/mol, deposition every 1 ps, bias factor=60).

- Step 2: Apply accumulated biases as static potential, then bias a structurally relevant CV (e.g., intermolecular contacts) for 400 ns per replica.

Analysis: Unbiased probabilities are reweighted using ( e^{\beta(V(s(R),t)-c(t))} ), where c(t) ensures normalization [22].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between the key enhanced sampling methods discussed:

Performance Considerations

Successful implementation requires careful parameter selection:

Table 2: Performance Optimization for Enhanced Sampling

| Parameter | Consideration | Typical Values | Impact on Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Replicas | System size and temperature range | 16-32 replicas | Too few replicas reduces exchange probability; too many increases computational cost |

| Temperature Range | Melting point and force field properties | 300-595 K for proteins | Must include temperatures where folding/unfolding transitions occur |

| Gaussian Width (σ) | CV fluctuations and system size | System-dependent (~5 for contact CVs) | Affects resolution of free energy reconstruction |

| Bias Factor | Well-tempered metadynamics convergence | 8-60 | Higher values give broader exploration but slower convergence |

| Exchange Attempt Frequency | Correlation between replicas | Every 1-10 ps | Too frequent attempts waste resources; too rare reduces efficiency |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Enhanced Sampling Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Core simulation dynamics | GROMACS 2021+ recommended for PLUMED compatibility [21] |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins | PLUMED 2.7.2+ | CV definition and bias potential | Essential for metadynamics; Custom AlphaFold CV available [21] |

| Containerization | Docker, Singularity | Reproducible computational environments | ljocha/GROMACS:2021-3.3 image available with AlphaFold CV support [21] |

| Force Fields | Amber99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36 | Molecular mechanics parameters | Amber99SB-ILDN used successfully for mini-protein folding [21] |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, PyEMMA, LOOS | Trajectory analysis and MSM construction | Critical for interpreting large datasets from enhanced sampling [23] |

Case Studies and Applications

Mini-Protein Folding

Enhanced sampling methods have successfully simulated the folding of small, fast-folding proteins such as:

Trp-cage (20 residues): Folding simulations using AlphaFold-based CVs in parallel tempering metadynamics captured folding equilibria and identified the critical role of secondary structure formation, particularly the α-helix, during the folding process [21] [26].

β-hairpin: Simulations revealed folding mechanisms and free energy landscapes consistent with experimental data, demonstrating the ability of these methods to reproduce known folding behavior [21].

Villin headpiece (35 residues): Multiple research groups have successfully folded villin using enhanced sampling approaches, revealing heterogeneous folding pathways and the potential existence of intermediates with native secondary structure but disordered tertiary contacts [20].

Overcoming Force Field Limitations

A significant challenge in protein folding simulations is force field accuracy. For example, some AMBER force field variants have predicted melting temperatures for Trp-cage more than 100K above experimental values [20]. Enhanced sampling methods help identify these discrepancies by enabling more thorough exploration of conformational space, thus providing valuable data for force field refinement and validation.

Large Protein and Multidomain Folding

While early successes focused on mini-proteins, recent advances now enable the study of larger, more complex systems:

Serpins: These large, multidomain protease inhibitors have been studied using structure-based models (Gō-like models) combined with all-atom simulations, revealing folding intermediates and misfolded states relevant to disease [15].

Protein oligomerization: PTMetaD-WTE has been applied to study protein-protein interactions and oligomerization, processes relevant to both normal function and pathological aggregation [22].

Enhanced sampling methods, particularly metadynamics and parallel tempering, have transformed molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding by enabling access to biologically relevant timescales and conformational spaces. The integration of these methods with data from AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold represents a particularly promising direction, combining physical simulations with learned structural information.

As computational power continues to grow and methods become more sophisticated, these approaches will increasingly tackle larger, more complex systems including multidomain proteins, protein-protein interactions, and protein-ligand complexes. The ongoing development of more accurate force fields, more efficient sampling algorithms, and more robust analysis techniques will further expand the impact of enhanced sampling methods on our understanding of protein folding and function.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful "computational microscope" for studying protein folding, conformational changes, and functional mechanisms at atomic resolution [27]. These simulations numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion to generate trajectories of atomic positions over time, enabling researchers to study physical movements of atoms and molecules that are difficult to observe experimentally [28]. However, the computational demands of MD simulations have historically limited their application to biologically relevant timescales, particularly for large systems or slow-folding proteins.

The field has witnessed a hardware revolution that has dramatically extended accessible simulation timescales. This revolution encompasses two complementary paths: the adaptation of massively parallel graphics processing units (GPUs) for general-purpose MD computing, and the development of specialized supercomputers like Anton, designed specifically for MD simulations. These advancements have enabled researchers to push simulation timescales from nanoseconds to milliseconds and beyond, opening new frontiers in understanding protein folding pathways, allosteric regulation, and drug-target interactions.

GPU Acceleration in Molecular Dynamics

The Shift from CPU to GPU Computing

Traditional MD simulations relied on central processing units (CPUs) for computation, but the growing complexity of molecular systems and demand for longer timescales prompted a shift to graphics processing units (GPUs) [29]. GPUs offer massive parallel processing capabilities ideal for MD algorithms, which can distribute force calculations across thousands of computational cores simultaneously. Benchmark studies demonstrate that GPU acceleration offers significant performance improvements, particularly for large systems, without compromising accuracy [29].

The performance advantage of GPUs stems from their architectural differences. While CPUs contain a relatively small number of powerful cores optimized for sequential serial processing, GPUs contain thousands of smaller cores designed for parallel execution. This parallel architecture perfectly matches the computational requirements of MD simulations, where forces between pairs of atoms can be calculated independently before being summed to integrate the equations of motion.

Current GPU Hardware for MD Simulations

Table 1: High-Performance GPUs for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| GPU Model | Architecture | CUDA Cores | Memory | Key Advantages for MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA RTX 4090 | Ada Lovelace | 16,384 | 24 GB GDDR6X | Excellent price-performance balance for smaller simulations [30] |

| NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | Ada Lovelace | 18,176 | 48 GB GDDR6 | Superior for memory-intensive simulations; ideal for large biological systems [30] |

| NVIDIA RTX 5000 Ada | Ada Lovelace | ~10,752 | 24 GB GDDR6 | Balanced performance for standard simulations [30] |

For molecular dynamics workloads, the key considerations when selecting GPUs include CUDA core count for parallel processing, memory capacity for handling large systems, and architectural features that optimize scientific computing [30]. The latest NVIDIA Ada Lovelace architecture introduces new Streaming Multiprocessors and enhanced Tensor Cores that increase throughput and efficiency of operations critical for MD simulations.

Performance benchmarks demonstrate remarkable acceleration factors when using GPUs for MD simulations. OpenCafeMol, a coarse-grained biomolecular simulator, demonstrated approximately 100-240x speedup on a single GPU (RTX 4090) compared to simulations on a typical 8-core CPU machine [31]. This level of acceleration directly translates to the ability to simulate longer timescales or larger systems within practical timeframes.

Multi-GPU Configurations for Enhanced Performance