How to Fix Molecular Dynamics System Instability: A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are powerful but prone to instability that can invalidate results and waste computational resources.

How to Fix Molecular Dynamics System Instability: A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are powerful but prone to instability that can invalidate results and waste computational resources. This article provides a comprehensive, step-by-step framework for researchers and drug development professionals to diagnose, resolve, and prevent MD system crashes. Covering everything from foundational principles and robust setup methodologies to advanced troubleshooting and rigorous validation, the guide synthesizes current best practices to ensure stable, reliable, and scientifically meaningful simulations.

Understanding the Root Causes of MD Instability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My simulation run ends with a solver error about an "unstable system." What does this mean? This typically means that parts of your system are not properly restrained and are undergoing rigid body motion. In a molecular dynamics context, this is akin to a molecule or part of a structure "flying away" because it lacks sufficient constraints or proper bonding interactions to counteract the applied forces, leading to a divergent solution that the solver cannot handle [1].

Q2: My simulation runs but the RMSD plot shows massive, unstable fluctuations. Is this a system instability?

Large, unstable fluctuations in Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) can indeed indicate a problem. While some fluctuation is normal, significant jumps or deviations (e.g., from 1 nm to 7 nm) can signal issues. It is recommended to first check your trajectory processing, for instance by using commands like gmx trjconv -pbc nojump to correct for periodic boundary condition artifacts before concluding that the system itself is unstable [2].

Q3: How can I tell if my results are "unphysical"? Unphysical results are those that violate fundamental physical laws or expected behaviors. Examples include:

- Excessive Displacements: Atoms or bodies moving far beyond what applied forces would allow [1].

- Energy Explosions: A non-physical, continuous increase in the system's total energy.

- Unrealistic Configurations: The simulation leads to molecular geometries that are not chemically or physically possible.

Q4: For nano-scale systems, what specific attractive forces can cause pull-in instability? In Nano-Electro-Mechanical Systems (NEMS), the interplay of attractive forces is critical. For separation gaps generally larger than 20 nm, the Casimir force (which varies with the inverse fourth power of the separation distance) is a dominant cause of pull-in instability. At smaller separations (below ~20 nm), the van der Waals force (varying with the inverse cube of the distance) becomes the primary concern [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Instabilities

Method 1: The "Soft Springs" Stability Test

This method helps identify which parts of your system are unstable by applying a gentle, stabilizing force and observing what moves excessively.

Experimental Protocol:

- Create a Test Study: Duplicate your unstable simulation study (e.g., label it "Gravity Test").

- Simplify Physics: Replace all complex external loads with a simple, uniform load like gravity.

- Apply Soft Springs: In the study settings, activate the "Use soft springs to stabilize model" option.

- Run and Analyze: Execute the simulation. The solver may warn of excessive displacements; proceed to save the results.

- Identify Unstable Bodies: Create a displacement plot with the deformed shape visualization turned off. Bodies showing high displacement (e.g., in red on a color gradient) are the unstable components requiring additional constraints [1].

Method 2: Frequency Analysis for Rigid Body Modes

This technique uses a frequency or modal analysis to detect components that are free to move as rigid bodies.

Experimental Protocol:

- New Study: Create a new frequency-type study (e.g., "Frequency Test").

- Copy Constraints: Transfer all fixture and contact definitions from the original study. Replace any non-bonded contacts (e.g., "no penetration") with bonded contacts for stability testing.

- Set Solver Properties: In the study properties, enable "Use soft spring to stabilize the model" and select a 'Direct Sparse' solver type for robustness.

- Run and Interpret: Run the analysis. The presence of natural frequencies very close to zero (or the first few mode shapes showing large, rigid movements) confirms the existence of unstable bodies [1].

Method 3: The "Build-Up" Approach

This is a systematic, bottom-up method to ensure every part of your system is properly connected.

Experimental Protocol:

- Start from Scratch: Duplicate your study and label it "Build Up." Initially, exclude all bodies from analysis.

- Establish a Stable Base: Re-include one "base" body that can be firmly fixed (e.g., with a "Fixture" constraint). Run the study to confirm stability.

- Iteratively Add Components: Gradually include adjacent bodies one by one. For each new body, explicitly define bonded contact sets to connect it to the already-stable part of the assembly.

- Test at Each Step: Run the study after adding each new body or small group of bodies. If instability occurs, you know the issue lies with the most recently added components or their contact definitions [1].

Quantitative Data on Forces Causing Instability

The table below summarizes key forces that can lead to pull-in instability in micro- and nano-scale devices, which are often the subject of MD simulations [3].

Table 1: Attractive Forces in NEMS/MEMS Leading to Pull-In Instability

| Force Type | Governing Equation | Range of Applicability | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casimir Force | ( F_{cas} = \frac{\pi^2 \hbar c w L}{240(g-y)^4} ) | Separation gaps generally > 20 nm | ( \hbar ): Reduced Planck's constant; ( c ): Speed of light [3] |

| van der Waals Force | ( F{vdw} = \frac{AH w L}{6\pi(g-y)^3} ) | Separation gaps < 20 nm | ( A_H ): Hamaker's constant [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Components for Studying Instability in MD Simulations of NEMS

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Silicon Nano-wire | A common deformable electrode geometry used to study pull-in instability and the effects of Casimir forces at the nanoscale [3]. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) | Used as a cantilever deformable electrode. Its mechanical properties and high aspect ratio make it ideal for investigating instability in NEMS switches and sensors [3]. |

| Graphene Sheet | Often serves as a rigid, fixed substrate electrode in NEMS experiments, providing a well-defined surface for interaction with nano-wires or CNTs [3]. |

| Pairwise Casimir Potential | An atomistic potential (e.g., ( U(r_{ij}) = C/r^7 )) used in MD frameworks to incorporate the effect of long-range Casimir forces, which is crucial for accurate simulation of instability in nanoscale gaps [3]. |

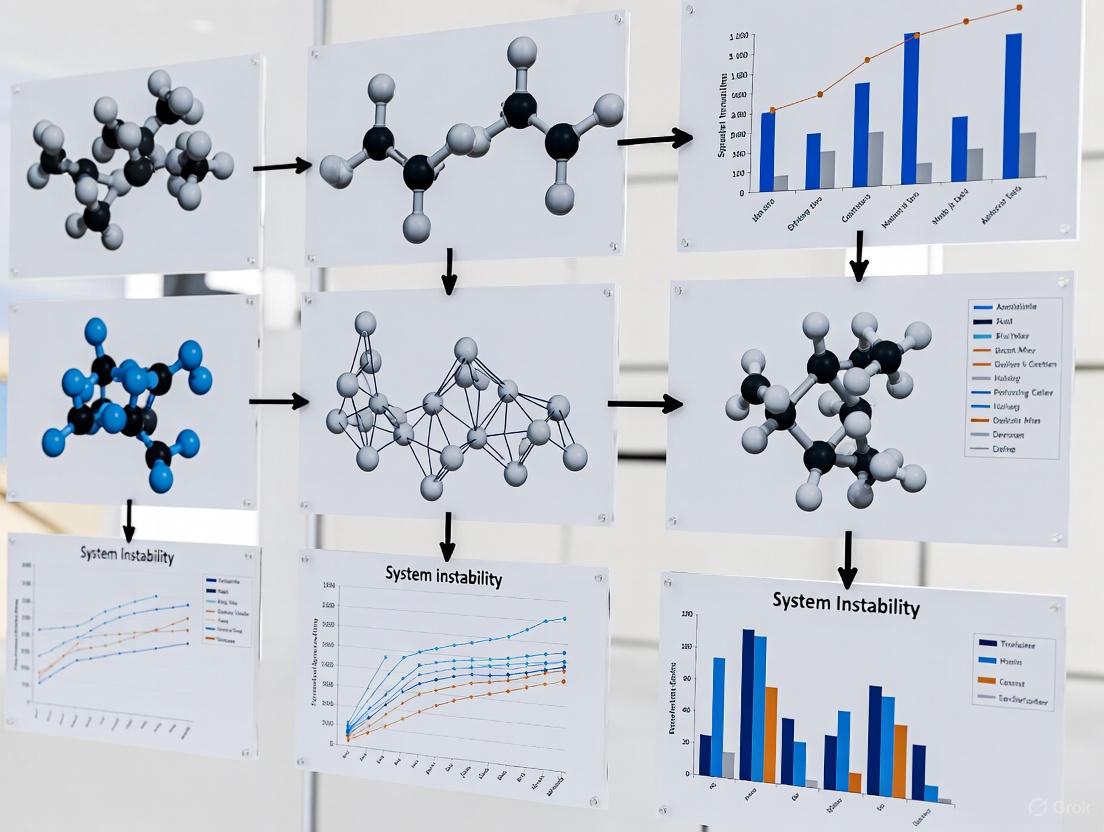

Experimental Workflow for MD System Stability Analysis

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving system instability in molecular dynamics simulations, integrating the methods described above.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Steric Clashes

Steric clashes are unphysical overlaps between non-bonding atoms in a molecular structure and are a common artifact in low-resolution models and homology models. Left unresolved, they can cause instability in molecular dynamics simulations [4].

Quantitative Identification of Steric Clashes

| Metric | Definition | Acceptable Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Clash-Score | The total Van der Waals repulsion energy from all clashes, divided by the number of atomic contacts checked [4]. | ≤ 0.02 kcal·mol⁻¹·contact⁻¹ [4] |

| Van der Waals Repulsion Energy | The energy calculated for a specific atomic overlap using force field non-bonded parameters (e.g., CHARMM19) [4]. | > 0.3 kcal/mol (0.5 kBT) defines a clash [4] |

Step-by-Step Protocol for Clash Resolution

The following workflow, "Automated Clash Minimization", outlines the automated protocol for resolving severe steric clashes in protein structures.

- Quantitative Clash Analysis: Use a tool like the Chiron server to calculate the clash-score of your input structure. This provides a quantitative measure of the severity of steric clashes, independent of protein size [4].

- Automated Minimization: If the clash-score is unacceptable, proceed with an automated minimization protocol using a method like Discrete Molecular Dynamics (DMD). DMD is a robust method for resolving severe clashes with minimal backbone perturbation, even for larger proteins [4].

- Validation: Re-calculate the clash-score of the refined structure to confirm it falls within the acceptable range derived from high-resolution crystal structures [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When I visualize my simulation trajectory, I see holes in the solvent, broken molecules, or my protein diffusing out of the box. What is wrong?

A: This is typically not an error. This is the expected behavior when visualizing simulations that use Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). PBC are used to mimic an infinite system, meaning atoms that exit one face of the box simultaneously re-enter from the opposite face. The appearance of "holes" or molecules leaving the box are visualization artifacts [5]. These issues can be fixed after the simulation by processing the trajectory file with tools like gmx trjconv in GROMACS to make molecules whole and center the system [5] [6].

Q: How do I prevent water molecules from being placed inside my protein or lipid membrane during solvation?

A: The solvate tool can sometimes place water molecules in undesired locations, like within alkyl chains of lipids. To prevent this, you can create a local copy of the vdwradii.dat file in your working directory and increase the van der Waals radius for the relevant atoms. A commonly recommended value is 0.375 nm instead of the default 0.15 nm for carbon atoms in lipid chains, which creates a larger exclusion zone and suppresses interstitial water placement [6].

Q: My homology model has severe steric clashes. Why can't I just use simple energy minimization to fix it?

A: While steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization with molecular mechanics force fields is a common first step, it may fail to resolve severe clashes. For these challenging cases, more robust protocols like those using Discrete Molecular Dynamics (DMD) or knowledge-based potentials (e.g., in Rosetta) are often necessary. These methods are specifically designed to handle large, unphysical atomic overlaps with minimal distortion to the overall protein fold [4].

Q: Should I provide my own temperature coupling group for a handful of ions in my system?

A: No. A temperature-coupling group must be of sufficient size to justify its own thermostat. Applying a thermostat to a very small group, like a few ions, can introduce errors and artifacts because many thermostat algorithms are designed to work well only in the thermodynamic limit (large number of particles). It is generally best to couple ions to the larger group of the solvent in which they are dissolved [5] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key computational tools and resources used in the preparation and refinement of molecular structures for simulation.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| CHIRON Web Server | An automated, quantitative tool for identifying and resolving severe steric clashes in protein structures using Discrete Molecular Dynamics (DMD) [4]. |

gmx trjconv Utility |

A core GROMACS tool for processing molecular dynamics trajectories to fix periodicity artifacts for visualization and analysis, such as making molecules whole and centering the system [5]. |

vdwradii.dat File |

A parameter file that defines atomic van der Waals radii. Modifying it allows users to control solvent placement during system setup by creating larger exclusion zones [6]. |

| Discrete Molecular Dynamics (DMD) | A simulation engine that uses square-well potentials for rapid sampling. It is effective for resolving steric clashes more robustly than some conventional minimizers [4]. |

| High-Resolution Structure Dataset | A curated set of experimentally determined protein structures (e.g., resolution < 2.5 Å) used to define a statistically acceptable baseline for native-like steric clashes (clash-score) [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "energy drift" mean in a Molecular Dynamics simulation? Energy drift refers to a gradual, unphysical change in the total energy of a simulated system over time. In a perfectly energy-conserving system, the total energy should fluctuate around a constant value. A significant upward or downward trend indicates that energy is being artificially added to or removed from the system, compromising the physical realism of the simulation and the validity of its results [7].

Q2: My simulation has a significant energy drift. Where should I start looking for the problem? Begin by investigating the most common culprits, which can be broadly categorized into three areas:

- Force Field Accuracy: The underlying model defining interatomic interactions may be inaccurate or incompatible with your system [7].

- Numerical Integration Errors: Inaccuracies in solving the equations of motion, often related to time step size or the specific integrator used, can introduce energy errors at every step [8].

- Dielectric Boundary Forces: In implicit solvent simulations (e.g., Poisson-Boltzmann), inaccurate calculation of forces at the boundary between different dielectric regions (e.g., solute and solvent) is a known source of energy violation [8].

Q3: How can a machine learning potential cause energy non-conservation? A machine learning (ML) potential can cause non-conservation in two key ways. First, the ML model may provide forces that are not the true negative gradient of its predicted energy, leading to a violation of the fundamental law of energy conservation. Second, the model might produce reasonable-looking forces or trajectories that are nonetheless not energy-conserving because they are not derived from a potential energy function at all. It is crucial to distinguish between the conservation of the simulation's internal energy and the conservation of the "true" physical energy [7].

Q4: What is a simple check for true-energy non-conservation? A practical approach is to monitor the simulated system's ability to replicate physically meaningful observables. For instance, you can simulate infrared spectra and evaluate the quality of the result against experimental or highly accurate theoretical data. Significant deviations suggest a high degree of true-energy non-conservation in your dynamics [7].

The following table outlines common issues, their diagnostic signatures, and recommended corrective actions.

| Source of Drift | Diagnostic Symptoms | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Force Calculation [8] | - Energy drift in implicit solvent simulations.- Unphysical forces on atoms near dielectric boundaries. | - Implement more accurate numerical methods for force calculation, such as the Immersed Interface Method (IIM).- Apply charge singularity removal techniques. |

| Incompatible Force Field [7] | - Unphysical dissociation of molecules during simulation.- Poor replication of known physical properties (e.g., infrared spectra). | - Validate the force field for your specific system.- For ML potentials, ensure forces are the true gradient of the energy.- Use proposed new criteria to evaluate true-energy conservation. |

| Lyapunov Instability & Sampling [9] | - Chaotic trajectories that are sensitive to initial conditions.- Difficulty obtaining reproducible averages for correlation functions (e.g., for ionic conductivity). | - Accept instability as a feature for sampling.- Use efficient "order-n" algorithms for on-the-fly calculation of correlation functions (e.g., MSD).- Ensure proper analysis techniques (e.g., compensating for box size changes in NpT simulations). |

| Numerical Solver Inaccuracy [8] | - Slow convergence of reaction field energies with grid spacing in finite-difference methods.- Inaccurate forces. | - Use harmonic averaging for dielectric constants at interfaces.- Employ more advanced interface treatments like IIM to achieve uniform high-order accuracy. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Implicit Solvent Models

This methodology is used to diagnose energy drift originating from the treatment of dielectric boundaries in implicit solvent simulations [8].

- 1. Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of reaction field energies, forces, and dielectric boundary forces for a known test system.

- 2. System Preparation:

- Construct a single dielectric sphere model, a well-studied analytical test system.

- Define a piece-wise constant dielectric model (e.g., ε=1 inside the sphere, ε=80 outside).

- Place a test charge at a defined location within the sphere.

- 3. Simulation & Analysis:

- Solve the Poisson’s equation using a finite-difference method on a uniform Cartesian grid.

- Treatment 1: Apply a simple harmonic average (HA) for dielectric constants at grid midpoints straddling the interface [8].

- Treatment 2: Apply the Immersed Interface Method (IIM), which enforces interface conditions into the discretization at grid points near the interface [8].

- Calculate and compare the reaction field energies and forces from both treatments against the known analytical solution.

- Quantify the improvement in accuracy and convergence rate with decreasing grid spacing.

- 4. Interpretation: The IIM method is expected to show significant improvement in both energies and forces, highlighting the importance of accurate boundary force calculation for energy conservation.

Protocol 2: Assessing True-Energy Conservation

This protocol provides a practical method to evaluate the physical realism of a simulation, which is particularly relevant for simulations using ML potentials or other methods where energy conservation is not guaranteed [7].

- 1. Objective: To estimate the degree of true-energy non-conservation in a molecular dynamics simulation.

- 2. System Preparation:

- Prepare your system as usual for the production simulation.

- 3. Simulation & Analysis:

- Run a standard MD simulation to generate a trajectory.

- From this trajectory, compute a physically meaningful observable that can be compared against a reliable benchmark. A recommended test is the simulation of infrared spectra.

- Quantitatively compare your simulated spectra with high-quality experimental data or results from highly accurate (e.g., quantum mechanical) calculations.

- 4. Interpretation: The degree of agreement between your simulation and the benchmark serves as a criterion for true-energy conservation. Large discrepancies indicate that the simulation, even if internally consistent, does not conserve true physical energy.

Visualizing the Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing energy drift in MD simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details essential computational tools and methodologies referenced in the troubleshooting of energy conservation.

| Item Name | Function in Research | Technical Specification / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Immersed Interface Method (IIM) [8] | Improves accuracy at dielectric boundaries in implicit solvent simulations. | A finite-difference method that incorporates jump conditions at the dielectric interface into the discretization scheme, leading to uniform high-order accuracy. |

| Harmonic Averaging (HA) [8] | Standard treatment for dielectric constants at grid midpoints in finite-difference methods. | Assigns the dielectric constant at a midpoint between two grid points using a weighted harmonic mean of the two dielectric constants, improving energy convergence. |

| True-Energy Conservation Criteria [7] | Evaluates the physical realism of a simulation beyond internal energy conservation. | A set of proposed criteria, such as benchmarking simulated infrared spectra, to assess whether a simulation conserves true physical energy. |

| Order-n Correlation Function Algorithm [9] | Enables efficient calculation of correlation functions (e.g., for MSD) on-the-fly. | An algorithm for calculating time-correlation functions with linear computational complexity in the number of particles, avoiding the need for large trajectory files. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Are large pressure fluctuations in my simulation a sign of a problem? No, large instantaneous pressure fluctuations are entirely normal in molecular dynamics simulations. Pressure is a macroscopic property, and its instantaneous value at the microscopic scale is not well-defined and can oscillate significantly. For a small box of 216 water molecules, fluctuations of 500-600 bar are standard. These fluctuations decrease with the square root of the number of particles; a system 100 times larger will still have fluctuations of about 50-60 bar [10]. The average pressure over time is what matters for correctness.

2. My temperature fluctuates. Is my thermostat broken?

No, the goal of a thermostat is not to keep the instantaneous temperature constant, but to ensure the average temperature of the system is correct and that the size of the fluctuations is appropriate. Fluctuations are expected and their magnitude is proportional to 1/sqrt(N_atoms), meaning they are more pronounced in smaller systems [11]. A good thermostat ensures the simulation samples the correct statistical ensemble.

3. What are acceptable energy fluctuations in an NVE simulation? In an NVE (microcanonical) ensemble, the total energy should be conserved. A common heuristic is that fluctuations on the order of 1 part in 5000 of the total system energy per ~20 timesteps are often considered acceptable, though this can be system-dependent. The key is to check for the absence of a systematic drift in the total energy over time, which would indicate an issue with the integration timestep or other simulation parameters [12].

4. Why does my molecule look broken or extend outside the box when I visualize it?

This is typically not an error but a visualization artifact due to Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). Molecules are free to diffuse across the boundaries of the simulation box. When an atom exits one side of the box, it re-enters from the opposite side. This can make molecules appear fragmented. The solution is to process your trajectory file with a tool like gmx trjconv (in GROMACS) using commands like -pbc mol or -pbc nojump to "re-make" molecules whole before visualization [2] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Pressure Fluctuations: Normal vs. Problematic

The table below summarizes key characteristics to help you diagnose pressure-related issues:

| Feature | Normal Fluctuations | Signs of Potential Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Magnitude | Hundreds of bar are typical for standard system sizes [10]. | Drastic, orders-of-magnitude changes that correlate with system deformation. |

| Average Value | Averages to the reference pressure set in the barostat over time [13]. | Consistent, significant deviation from the reference pressure over the production run. |

| System Size | Scale as 1/sqrt(N_atoms) [10]. |

Unusually large even for very large systems. |

| Impact on Structure | No impact on the stability of the biomolecular structure. | Coupled with unfolding, compression, or dissolution of the solute. |

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Calculate the Average: Use your MD analysis tools to compute the average pressure over your production simulation. Do not rely on instantaneous values.

- Check the Trajectory: Visually inspect the trajectory to ensure the solute (e.g., protein) remains stable and the solvent density looks uniform. Look for catastrophic collapse or expansion.

- Verify Barostat Settings: Confirm that the

compressibilityvalue in your input file is appropriate for your solvent (e.g.,4.5e-5 bar⁻¹for water) and that thetau_p(barostat time constant) is set to a reasonable value (e.g., 1-5 ps) [13].

Pressure Fluctuation Diagnosis

Temperature Control and Thermostat Configuration

Common Thermostat Pitfalls:

- Over-coupling: Using too many separate thermostat groups (e.g., one for the protein, one for water, one for ions) can introduce artifacts. For a protein simulation,

tc-grps = Protein Non-Proteinis usually sufficient and recommended [10]. - Incorrect Thermostat for Small Systems: Avoid using thermostats like Nosé-Hoover or Berendsen for components with very few degrees of freedom (e.g., a non-interacting ligand in free energy calculations) [10].

- Slow Equilibration: If the temperature of different system components equilibrates too slowly, try switching the thermostat coupling regime. For example, in CP2K, using

REGION MASSIVE(which couples 3 degrees of freedom per atom) instead ofREGION GLOBALcan lead to faster equipartition [11].

Best Practices:

- Use a thermostat known to sample the correct statistical ensemble (e.g., stochastic thermostats like Langevin for small systems or Nose-Hoover for larger ones).

- Apply the thermostat to the entire system or large, logically connected groups.

- Ensure the thermostat time constant (

tau_t) is not set too aggressively, which can artificially suppress natural fluctuations.

Temperature Stabilization Guide

Energy Conservation in NVE Simulations

Diagnosing Energy Drift: A systematic drift in total energy in an NVE simulation indicates a problem with the integration algorithm or energy conservation. The table below lists common culprits and solutions.

| Issue | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Timestep Too Large | Energy drift increases with larger timesteps. | Reduce the integration timestep (e.g., from 2 fs to 1 fs). |

| Incorrect Treatment of Long-Range Electrostatics | Energy drift and structural artifacts. | Use a more accurate method like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME). |

| Constraint Algorithm Errors | Energy drift, especially with bond constraints. | Ensure a robust constraint algorithm like P-LINCS is used and correctly parametrized [10]. |

| Round-off Error | Can be an issue in single precision simulations. | Use double precision for more sensitive calculations. |

| Incorrect PBC Handling | Energy drift and "blowing up" of molecules. | Use -pbc nojump during trajectory processing for analysis, but ensure PBC are correctly implemented in the simulation itself [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key computational "reagents" and their functions in ensuring stable MD simulations.

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Parrinello-Rahman Barostat | A robust barostat for pressure coupling that samples the correct NPT ensemble. | Preferred over simpler barostats like Berendsen for production runs [13]. |

| Langevin Thermostat | A stochastic thermostat good for small systems and providing correct ensemble sampling. | Good choice for solvated ligands or small proteins [10]. |

| Leap-frog Integrator | A numerical algorithm for integrating Newton's equations of motion. | Common default in many packages like GROMACS due to its efficiency and stability [10]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | A method for accurately calculating long-range electrostatic interactions. | Critical for avoiding artifacts and energy drift in simulations of charged systems [10]. |

| LINCS/P-LINCS | Algorithms for constraining bond lengths, allowing for a longer integration timestep. | P-LINCS is the parallel version, essential for stable simulations with constraints [10]. |

gmx trjconv Utility |

A trajectory processing tool for fixing PBC artifacts, centering, and fitting. | Essential for both analysis and visualization [2] [10]. |

The Impact of Force Field Selection and Compatibility on System Stability

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My simulation crashed or shows unrealistic protein motions. Could the force field be the problem? Yes, this is a common issue. An incorrectly chosen or parameterized force field is a frequent cause of instability. Using a force field designed for proteins on a carbohydrate system, or mixing incompatible force fields for different parts of your system (e.g., a protein and a drug-like ligand), can disrupt the balance of interactions, leading to unphysical behavior or crashes [14]. Always select a force field validated for your specific type of molecule.

Q2: How can I check if my force field is compatible with all molecules in my system? Thorough validation is key. First, visually inspect your initial structure for steric clashes or distorted geometries that may cause instability [14]. Second, after minimization, check that the potential energy of the system is negative and that key thermodynamic properties like temperature, pressure, and density have stabilized during equilibration [15] [14]. For non-standard molecules like ligands, ensure parameters were generated to be compatible with the main force field [14].

Q3: What does a stable, equilibrated system look like before I start production runs? Before beginning production simulation, your system should show stable plateaus in key thermodynamic properties under the chosen ensemble (NVT, NPT) [14]. Monitor the following:

- Potential Energy: Should be negative and stable [15].

- Temperature and Pressure: Should fluctuate around your set points [15].

- System Density: Should remain at a reasonable, stable value [15].

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Should plateau, but note that a flat RMSD alone does not guarantee correct thermodynamic behavior [14].

Q4: Are large fluctuations in RMSD always a sign of force field problems?

Not necessarily. First, rule out technical artifacts. Large, sudden jumps in RMSD can be caused by molecules crossing periodic boundaries, which can be corrected using trajectory analysis tools (e.g., gmx trjconv -pbc nojump in GROMACS) [2]. However, if corrections are applied and the protein still shows large, unstable deviations from its native state, it could indicate that the force field's energy surface does not favor the folded structure, potentially due to inaccuracies in the backbone or side-chain dihedral parameters [16] [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Force Field-Related Instabilities

The table below outlines common symptoms, their potential causes, and corrective actions.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation crashes during energy minimization or early in dynamics | Poor starting structure with steric clashes; Severe force field incompatibility for a specific molecule [14]. | Extend minimization; Visually inspect and repair the initial structure; Check protonation states; Re-parameterize non-standard molecules [14]. |

| Unrealistic protein unfolding or large, unstable RMSD fluctuations | Incorrect backbone potential in the force field; Inaccurate side-chain dihedral parameters; PBC artifacts in analysis [16] [2]. | Use a modern, validated force field (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB-ILDN); Correct for PBC in trajectory analysis [16] [2]. |

| Unphysical ligand behavior (e.g., drifting away, distorted geometry) | Ligand parameters are incompatible with the protein/water force field; Inaccurate torsion profiles for the ligand [17] [14]. | Use a compatible small molecule force field (e.g., GAFF2 with AMBER, CGenFF with CHARMM); Ensure ligand parameters are derived to work with the main force field [14]. |

| System density, pressure, or energy fails to stabilize during equilibration | Inadequate equilibration protocol; Incorrect or unbalanced non-bonded (vdW) parameters [14] [18]. | Extend equilibration until properties plateau; Validate force field's reproduction of liquid-state properties (density, enthalpy of vaporization) [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating and Equilibrating a System for Stable Production Dynamics

This protocol ensures your system is stable and well-equilibrated before starting production runs, minimizing force field-related instabilities.

1. System Preparation

- Structure Check: Obtain your initial structure (e.g., from PDB) and meticulously check for missing atoms, residues, and correct protonation states at your desired pH using tools like PDbfixer or H++ [14].

- Force Field Selection: Choose a force field specifically developed for your molecule (see Table 1). Do not mix force fields unless they are explicitly designed to be compatible [14].

- Parameter Generation: For any non-standard molecules (e.g., ligands, cofactors), use tools that generate parameters compatible with your main force field (e.g., CGenFF for CHARMM, GAFF for AMBER) [14].

- Solvation and Ionization: Solvate the system in an appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the charge and achieve physiological concentration.

2. Energy Minimization

- Objective: Remove any residual steric clashes and relax the structure into a local energy minimum.

- Method: Use a robust energy minimization algorithm like steepest descent or conjugate gradient. Continue until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) [14].

3. System Equilibration

- Principle: Gently introduce temperature and pressure to the system while restraining the heavy atoms of the solute (e.g., protein backbone). This allows the solvent and ions to relax around the solute.

- NVT Equilibration: Simulate for 50-100 ps in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) with solute restraints. Monitor temperature stability.

- NPT Equilibration: Simulate for 100-200 ps (or longer if needed) in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) with solute restraints. Monitor pressure and system density for stability.

- Final NPT Equilibration: Run a final NPT equilibration without any restraints. This is a critical step. Verify equilibration by ensuring the potential energy, density, temperature, and pressure have all reached a stable plateau [14].

4. Pre-Production Checks

- Visual Inspection: Visually examine the final equilibrated structure to ensure no gross distortions have occurred.

- Metric Validation: Generate a Ramachandran plot for a protein to check for reasonable secondary structure [15].

Protocol 2: A Methodology for Evaluating Force Field Performance on a Protein System

This protocol provides a framework for assessing whether a force field produces stable, physically accurate dynamics for a protein.

1. Simulation Setup

- Prepare the protein system as described in Protocol 1, using the force field under evaluation.

- Run multiple independent simulations (at least 3) with different initial random seeds to ensure observed behaviors are reproducible and not stochastic artifacts [14].

2. Production Simulation

- Run a production simulation of a length sufficient to observe the dynamics of interest (e.g., hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds for larger conformational changes).

3. Analysis and Validation Compare simulation-derived observables against experimental or benchmark data where available.

- Structural Stability: Calculate the backbone RMSD relative to the native structure. While a stable RMSD is good, it is not sufficient alone [14].

- Local Flexibility: Calculate the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of residue positions. Compare with experimental B-factors from crystallography [14].

- Secondary Structure: Monitor the retention of known secondary structural elements (e.g., alpha-helices, beta-sheets) over time using tools like DSSP.

- Ensemble Validation (if possible): Compare NMR observables such as spin relaxation rates or residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) if experimental data exists [14].

Workflow Diagrams

Force Field Selection and Stability Analysis Workflow

Force Field Parameterization and Compatibility Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Common Biomolecular Force Fields and Their Applications

| Force Field | Primary Application | Key Characteristics | Common Pairing for Small Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 [16] [19] | Proteins, Nucleic Acids, Lipids | Detailed parameters for biomolecules; Good for membrane systems and protein-ligand interactions [19]. | CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) [14] |

| AMBER (e.g., ff19SB, ff14SB) [16] [19] | Proteins, Nucleic Acids | Emphasis on accurate backbone and side-chain dihedrals; Widely used in protein folding and drug binding studies [16] [19]. | General AMBER Force Field (GAFF/GAFF2) [17] [14] |

| GROMOS [16] [19] | Proteins, Lipids, Carbohydrates | Unified atom design; High computational efficiency; Suitable for large-scale simulations like lipid membranes [19]. | GROMOS-compatible parameter sets |

| OPLS/OPLS-AA [16] [19] | Proteins, Organic Molecules | Originally parameterized for liquid simulations; Strong performance in drug design and protein-ligand binding [19] [18]. | OPLS-based small molecule parameters |

Table 2: Key Parameterization and Validation Techniques

| Method | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Calculations [17] [18] | Provides target data (e.g., torsion energy profiles, electrostatic potentials) for deriving bonded and non-bonded force field parameters. | [17] [18] |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) [18] | An optimization technique that automates the fitting of force field parameters (e.g., van der Waals terms) to reproduce experimental data. | [18] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNN) [17] | A machine learning approach that predicts force field parameters for a molecule directly from its structure, enabling expansive chemical space coverage. | [17] |

| Liquid-State Property Validation [18] | The process of testing parameter sets by simulating neat liquids and comparing results to experimental density and enthalpy of vaporization. | [18] |

Building Stable Systems: Robust Setup and Parameter Selection

A guide to building stable molecular dynamics systems from imperfect initial structures.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of biomolecules are powerful tools in structural biology and drug discovery. However, system instability during simulation often originates from errors in the initial structure preparation phase. This guide provides specific, actionable solutions to correct common issues in protein structure files, ensuring a more robust and physically realistic foundation for your MD research.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Q: Why does my simulation crash with errors about "bad contacts" or "bonds rotating more than 30 degrees"?

- A: This is a classic sign of an unstable system. The culprit is often an inadequately prepared initial structure. Before investing computational resources in long production runs, ensure your structure has been properly corrected for missing atoms, correct protonation states, and has undergone sufficient energy minimization to relieve steric clashes [20].

- Q: My tool reports "atom X in residue Y not found in residue topology database." What does this mean?

- A: This error indicates a mismatch between the atom names in your coordinate file and the names defined in the force field's residue database. The force field is not "magical"; it can only build topologies for molecules defined in its database. Solutions include renaming the atoms in your structure to match the database or, if the residue is entirely missing, parameterizing the molecule yourself or finding a compatible topology file [21].

- Q: I have a raw PDB file from the Protein Data Bank. What are the most common defects I need to fix before simulation?

- A: PDB files from experimental sources often lack hydrogen atoms, have incomplete side chains, contain missing residues in the sequence (gaps), and use non-standard naming for residues or atoms. Furthermore, the protonation states of residues like histidine, glutamine, and asparagine are often ambiguous and must be assigned based on the local hydrogen-bonding environment [22] [23].

- Q: How do I handle the protonation states of histidine and other ambiguous residues?

- A: A single, static configuration is often insufficient. Research suggests that for many proteins, multiple rotamer and protonation states are energetically accessible and consistent with the experimental data. Protocols like the Rotamer and Protonation Assignment (RAPA) analyze the local environment to identify a set of unique, consistent states. Investigate these states to ensure your simulation is not biased by an incorrect initial assignment [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Structure Preparation Errors

The table below outlines frequent errors encountered during structure preparation with pdb2gmx and other tools, along with their diagnoses and solutions.

| Error Message / Symptom | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Residue not found in residue topology database" [21] | The force field does not have an entry for this residue, or the residue name in your file is incorrect. | 1. Check for alternative residue names in the force field database.2. Manually create a topology (.itp) file for the molecule.3. Use a different force field with parameters for your residue. |

| "WARNING: atom X is missing in residue Y" [21] | The structure is incomplete. Common for hydrogen atoms or heavy atoms noted in PDB REMARK 465/470 records. |

1. Use -ignh to let pdb2gmx add correct hydrogens.2. For missing heavy atoms, use tools like PDBrestore, Chimera, or Modeller to complete the structure [23]. |

| "Long bonds and/or missing atoms" [21] | Severe structural incompleteness causing topology building to fail. | Use dedicated structure repair software to model in the missing atoms before proceeding with topology generation. |

| Simulation instability (bond rotation, bad contacts) [20] | The initial structure may have steric clashes, incorrect geometry, or wrong protonation states. | 1. Ensure all missing atoms are added and protonation states are correct.2. Run a thorough energy minimization protocol.3. Consider a multi-step equilibration with position restraints. |

| Ambiguous rotamer/protonation states for ASN, GLN, HIS [22] | The local hydrogen-bonding environment allows for more than one chemically plausible state. | Use a protocol like RAPA to identify the set of energetically accessible states instead of choosing a single state. Run simulations for multiple consistent configurations. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Robust Structure Preparation

The following workflow, incorporating modern tools and best practices, ensures a comprehensive approach to preparing a stable initial structure for MD simulation.

Methodology

- Initial Analysis and Fetching: Begin by obtaining your raw structure, either from a local file or by fetching it from the PDB using its 4-character code.

- Structural Repair: Use a specialized tool like PDBrestore to perform initial repairs. This includes adding hydrogen atoms, completing missing atoms in side chains, and identifying disulfide bridges [23].

- Gap Filling: If the protein sequence has missing residues (gaps), these must be filled. PDBrestore employs a "divide and conquer" strategy, generating the missing subsequence in an all-trans conformation and testing different orientations to find the optimal fit with minimal steric clashes, followed by energy minimization [23].

- Protonation State Assignment: Critically assess the protonation states of ambiguous residues like histidine, asparagine, glutamine, serine, threonine, and tyrosine. Do not rely on a single static assignment. Employ a method like the RAPA protocol to identify all rotamer and protonation states that are energetically consistent with the local hydrogen-bonding environment of the crystal structure [22].

- Ligand and Cofactor Parameterization: For any non-standard molecules (e.g., drugs, cofactors, metal ions), derive topology and parameter files. Tools like PDBrestore can generate GAFF2 parameters for ligands for use with GROMACS [23]. Always ensure metal-coordinating residues (like cysteines or histidines) have the correct topology.

- Final Energy Minimization: The final, complete structure (protein, repaired gaps, corrected states, ligands, and cofactors) should undergo a final energy minimization using a force field like AMBER99SB-ILDN to relieve any remaining atomic clashes and optimize the geometry [23].

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of this workflow, highlighting the critical decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential software tools and resources for preparing molecular structures.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PDBrestore [23] | Web-based tool for repairing PDB files: adds H, fixes side chains, fills gaps, parameterizes ligands. | Streamlines the initial, cumbersome preparation of protein-ligand structures from raw PDB files for MD. |

| RAPA Protocol [22] | A self-consistent approach to assign rotamer and protonation states beyond a single configuration. | Identifies multiple energetically accessible states for ambiguous residues (ASN, GLN, HIS, etc.). |

| CHARMM-GUI [23] | A web-based graphical user interface for setting up complex MD systems, including membrane proteins. | An alternative for system building, though may have limitations in gap repair and metal incorporation. |

| AMBER99SB-ILDN [23] | A well-validated force field for proteins. | Used in the final minimization stage to optimize the geometry of the repaired structure. |

| VMD - PSF Plugin [23] | A molecular visualization and analysis program with a plugin to generate protein structure files. | Often used internally by other tools (like PDBrestore) to add missing atoms and hydrogens. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the most important rule for choosing a time step? The most critical rule is the Nyquist theorem, which states that your time step must be less than half the period of the fastest vibration in your system to accurately capture its dynamics. [24] In practice, a more conservative ratio of 0.033 to 0.01 of the shortest vibrational period is often recommended for acceptable energy conservation. [24]

What is a typical time step value for a biomolecular system? For systems containing light atoms like hydrogen, a time step of 0.5 to 2 femtoseconds (fs) is standard. [24] When bonds involving hydrogen are constrained (e.g., using algorithms like SHAKE or LINCS), a 2 fs time step is commonly and successfully used. [24]

How can I check if my time step is appropriate? A reliable method is to run a constant energy (NVE) simulation and monitor the conserved quantity (total energy). [24] A significant energy drift indicates an unstable simulation, often due to a time step that is too large. For publishable results, the long-term drift should ideally be less than 1 meV/atom/ps. [24]

What happens if I use a time step that is too large? An excessively large time step leads to instability and artifacts, including: [25] [24]

- Lack of energy conservation: The total energy of the system will drift.

- Loss of equipartition: Energy is not distributed correctly among the different degrees of freedom.

- Numerical blow-up: The simulation may crash due to unphysical forces or the failure of constraint algorithms.

Can I use a larger time step with machine learning? Machine learning algorithms can predict trajectories with longer time steps, but they often do not preserve the geometric structure (symplecticity) of Hamiltonian flow, leading to the energy conservation and equipartition artifacts mentioned above. [25] Emerging methods focus on learning structure-preserving maps, which are equivalent to learning the mechanical action of the system, to enable longer time steps while maintaining physical fidelity. [25]

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Time Step-Related Instabilities

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Next Diagnostic Step |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid drift in total energy in NVE simulation | Time step too large; Non-symplectic integrator | Check period of fastest vibration (e.g., C-H ~11 fs); Reduce time step to 0.5-2 fs [24] |

| Simulation crashes with "SHAKE failure" | Large time step prevents convergence of bond constraints | Reduce time step; Check for incorrect topology (e.g., misplaced atoms) [24] |

| Lack of equipartition between degrees of freedom | Underlying integrator lacks structure-preserving properties | Verify use of a symplectic and time-reversible integrator like Velocity Verlet [25] [24] |

| Energy drift in NVT/NPT simulations | Time step too large; Incorrect "conserved quantity" for the ensemble | Identify the correct conserved quantity for your Thermostat/Barostat and monitor its drift [24] |

Protocol for Systematically Determining the Optimal Time Step

Objective: To empirically determine the maximum stable time step for a new molecular system.

Principle: The optimal time step is the largest value that does not cause a significant drift in the conserved quantity of the system over a short test simulation. [24]

Procedure:

- Preparation: Start with a well-equilibrated system. The initial configuration should be at a local energy minimum.

- Baseline Test: Run a short (10-50 ps) simulation in the NVE ensemble using a conservative time step (e.g., 0.5 or 1 fs). This establishes a baseline for energy conservation.

- Iterative Testing: Gradually increase the time step (e.g., to 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 fs) and for each value, run a new short NVE simulation from the same initial configuration.

- Quantitative Analysis: For each simulation, calculate the drift in the total energy (the conserved quantity for NVE). This is typically done by performing a linear regression of the total energy over time.

- Acceptance Criterion: The maximum acceptable time step is the largest value for which the energy drift remains below your chosen threshold (e.g., < 1 meV/atom/ps for rigorous studies). [24]

- Final Validation: Conduct a longer (100 ps - 1 ns) production simulation in your target ensemble (NVT/NPT) using the selected time step to ensure stability over a more relevant timescale.

Recommended Time Steps for Different Simulation Types

Table 1: Guidelines for time step selection based on system composition and method.

| Simulation Type / Condition | Recommended Time Step | Key Rationale and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Biomolecules (with constraints) | 2 fs | Default for most systems with constrained bonds to hydrogen. [24] |

| Systems with light atoms (H, D) | 0.25 - 1 fs | Necessary to resolve high-frequency vibrations; essential for accurate hydrogen dynamics. [24] |

| All-atom (no constraints) | 0.5 - 1 fs | Required to resolve the fastest bond vibrations (e.g., C-H period ~11 fs). [24] |

| Machine Learning Integrators | > 10x conventional | Emerging method; requires structure-preserving maps to avoid energy drift. [25] |

| Coarse-Grained Models | 10 - 50 fs | Softer effective potentials from eliminated degrees of freedom allow longer time steps. |

Energy Drift Tolerance Levels

Table 2: Benchmarks for acceptable levels of energy drift in conserved quantities. [24]

| Application Context | Maximum Tolerable Drift | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Results | < 10 meV/atom/ps | Sufficient for observing large-scale conformational dynamics. |

| Publishable Results | < 1 meV/atom/ps | Standard for rigorous, quantitatively accurate scientific studies. |

Advanced Methods for Larger Time Steps

Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR): This technique allows for a larger time step by artificially redistributing mass from heavy atoms to the bonded hydrogen atoms. [26] This slows down the fastest vibrations (which are mass-dependent), effectively reducing the Nyquist frequency and permitting time steps of up to 4 fs. [26]

Using Constraint Algorithms: Algorithms like SHAKE, LINCS, and SETTLE are fundamental to standard MD practice. [24] They remove the highest frequency vibrations (bond stretches involving hydrogen) from the dynamics, which is why a 2 fs time step becomes stable for most biomolecular systems.

Structure-Preserving (Symplectic) Integrators: Using integrators that preserve the geometric structure of Hamiltonian mechanics (e.g., Velocity Verlet) is crucial for long-term stability. [25] [24] These integrators conserve a "shadow Hamiltonian," ensuring excellent energy conservation even over long simulation times. [25]

Time Step Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential software and reagents for stable molecular dynamics simulations. [27] [28]

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in MD |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software | High-performance MD engine, excellent for testing and production. [27] [28] |

| AMBER | MD Software | Suite for biomolecular simulations, includes advanced analysis tools. [28] |

| OpenMM | MD Engine | Highly flexible, GPU-optimized toolkit; used in Flare and others. [26] [28] |

| CHARMM | MD Software/Force Field | Comprehensive simulation and analysis program with its own force field. [28] |

| NAMD | MD Software | Fast, parallel MD simulator, often used with VMD for visualization. [28] |

| MDAnalysis | Analysis Tool | Python library for analyzing MD trajectories. [27] |

| VMD | Visualization Tool | Visualization, animation, and analysis of large biomolecular systems. [27] |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | Used for free energy calculations and advanced sampling techniques. [27] |

| SHAKE/LINCS | Algorithm | Constrains bond lengths to allow for longer time steps. [24] |

| Velocity Verlet | Algorithm | Symplectic and time-reversible integration algorithm for stable dynamics. [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is my system's potential energy excessively high at the start of a simulation? A: A very high initial potential energy almost always indicates steric clashes in your initial structure. These are instances where atoms overlap, creating large repulsive forces that can destabilize the simulation. To resolve this, you should perform energy minimization before starting the production dynamics. This process uses algorithms like steepest descent to adjust atomic positions and find a lower energy, clash-free configuration [29].

Q: My minimization is not converging. What should I do? A: Non-convergence can be due to several factors. First, check for persistent steric clashes or unrealistic bond lengths/angles in your initial model. You may need to use a multi-stage minimization approach, starting with strong restraints on the protein backbone to allow solvent and side chains to relax, followed by a full minimization with all restraints removed [30] [29]. Additionally, ensure you are using a sufficient number of minimization steps.

Q: Should I use restraints during minimization? A: Yes, using restraints is a common and recommended practice. A typical protocol involves an equilibration run where heavy atoms of the protein are restrained to their starting positions, allowing the solvent (water and ions) to relax around the structure. This prevents unnecessary distortion of the carefully built protein model while optimizing the solvent environment [30].

Q: What is the difference between energy minimization and equilibration? A:

- Energy Minimization is a static process that seeks the nearest local energy minimum on the potential energy surface. It primarily resolves steric clashes and incorrect geometries without regard to temperature.

- Equilibration is a dynamic process that uses Molecular Dynamics (MD) to bring the system to a stable state at the desired temperature and pressure. It involves gradually releasing restraints and allowing the system to settle into a physiologically realistic ensemble of states [30] [29].

Q: How do I know if my minimization was successful? A: A successful minimization is typically indicated by a stable and low final potential energy, but the most critical indicator is a low root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the forces or the atomic coordinates between successive minimization steps. Many minimization algorithms report convergence when the energy change per step and the maximum force fall below predefined thresholds [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| System explodes during initial dynamics | Severe steric clashes not relieved by minimization; unstable bonds/angles. | Run additional minimization steps; check topology for parameter errors; use stronger restraints during initial equilibration [29]. |

| High energy after minimization | Minimization trapped in a local high-energy minimum; insufficient steps. | Try a conjugate gradient algorithm after initial steepest descent; increase the number of minimization cycles [29]. |

| Large RMSD in backbone during equilibration | Solvent-protein interactions not optimized; restraints released too quickly. | Extend the equilibration phase with positional restraints on protein heavy atoms; ensure water and ions are properly relaxed first [30]. |

| Unphysical distortion of the protein | Inadequate or missing restraints during minimization/equilibration. | Apply harmonic restraints to the protein backbone or alpha-carbons during the initial minimization and early equilibration stages [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Energy Minimization for an RNA Nanostructure

The following protocol, adapted from methods for RNA systems, outlines a robust energy minimization procedure to prepare a stable system for molecular dynamics [29].

1. Prepare Initial Structure and Topology

- Obtain your initial structure from sources like X-ray crystallography, NMR, or computational design.

- Use a tool like

tleap(in AMBER) to assign force field parameters (e.g.,ff14SBfor proteins,OL3for RNA), create the topology file, and solvate the system in a water box (e.g., TIP3P). Add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

2. Run Initial Minimization with Restraints

- This step relaxes the solvent and ions around the fixed solute.

- Restraints: Apply strong positional restraints (e.g., 50 kcal/mol/Ų) on the heavy atoms of your macromolecule.

- Algorithm: Use the steepest descent method for the first 500-1000 steps, as it is robust for removing large clashes.

- Goal: Minimize until the energy change between steps is sufficiently small (convergence).

3. Run Full System Minimization

- Remove all positional restraints.

- Algorithm: Start with steepest descent for 1000-2500 steps, then switch to a conjugate gradient algorithm for finer optimization until convergence is achieved.

- Goal: Find a low-energy, clash-free starting configuration for the entire system.

This workflow can be visualized as follows:

Minimization and Equilibration Parameters

The table below summarizes key parameters from a documented protocol for achieving a stable minimization [30].

| Parameter | Value | Purpose / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Minimization Algorithm | Steepest Descent | Effective for removing large steric clashes [29]. |

| Positional Restraints | Applied to protein heavy atoms | Prevents distortion while solvent relaxes [30]. |

| Equilibration Duration | 100 ps | Allows system to stabilize at target temperature/pressure [30]. |

| Pressure Coupling | Turned off during production | After equilibration, system size is typically fixed [30]. |

| Production Simulation | 10 ns (example) | The final, unrestrained simulation used for data collection [30]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software packages like AMBER, GROMACS, or NAMD are essential platforms for performing energy minimization and subsequent MD simulations. They contain the force fields and algorithms needed for the calculations [29]. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical parameters (e.g., ff14SB, OL3) that defines the potential energy function, governing bonded and non-bonded interactions between atoms during the simulation [29]. |

| Visualization Tool | Software such as VMD or Discovery Studio Visualizer is critical for inspecting structures pre- and post-minimization, checking for steric clashes, and analyzing trajectories [29]. |

| Solvent Model | A water model (e.g., TIP3P) that represents water molecules in the simulation box, creating a more realistic biological environment than a vacuum [29]. |

| Neutralizing Ions | Ions like Na⁺ or Cl⁻ are added to the system to neutralize the net charge of the solute, which is crucial for achieving correct electrostatic properties and simulation stability [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Equilibration Issues

This guide helps you diagnose and resolve common problems encountered during NVT and NPT equilibration in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. Follow the workflow below to systematically identify and fix issues with your system.

Common Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: Energy Drift or Continuous Decrease

- Description: The total potential energy of the system does not reach a stable plateau but instead shows a steady downward trend over long simulation times (e.g., 60-100 ns) [31].

- Diagnosis: This indicates the system is slowly relaxing towards a more stable configuration, often due to a sub-optimal initial structure or slow dynamics, particularly in confined systems [31].

- Solutions:

- Extend Simulation Time: Allow the simulation to run for at least five times the observed characteristic relaxation time (Tc). If Tc is ~20 ns, run for >100 ns [31].

- Review Initial Configuration: Re-check the initial system setup, including solvent packing and the placement of molecules within the simulation box.

- Use Enhanced Sampling: For complex systems like a slit pore with confined water, combine MD with occasional Monte Carlo (MC) displacement or rotation moves to help the system overcome energy barriers [31].

Problem 2: Excessive Pressure Oscillations

- Description: The pressure fluctuates wildly and does not stabilize around the target value.

- Diagnosis: This is often related to the parameters of the barostat or the properties of the system itself.

- Solutions:

- Adjust Barostat Coupling Time: Increase the time constant for pressure coupling (e.g., the

1000.0value in LAMMPS'nptfix) to dampen oscillations. This parameter should be larger for more complex systems [31]. - Check Compressibility: Ensure the correct isothermal compressibility value is set for your material in the barostat algorithm.

- Adjust Barostat Coupling Time: Increase the time constant for pressure coupling (e.g., the

Problem 3: Density Fails to Converge

- Description: The system density fluctuates and does not settle at the expected value.

- Diagnosis: The system may not be fully relaxed, or the initial density guess may be too far from the equilibrium value.

- Solutions:

- Use a Robust Equilibration Protocol: Follow a multi-step equilibration procedure. A proposed ultrafast method for polymers has been shown to be ~200% more efficient than conventional annealing and ~600% more efficient than a basic "lean" method [32].

- Verify Force Field Compatibility: Ensure that the chosen force field is appropriate for your system and conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure).

Quantitative Benchmarks for Equilibration Performance

The table below summarizes data from a study on equilibrating a perfluorosulfonic acid (PFSA) polymer, comparing the efficiency of different methods [32].

| Equilibration Method | Relative Efficiency (Baseline: Lean Method) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Proposed Ultrafast Method | ~600% more efficient | A robust, novel algorithm for fast equilibration of complex polymer networks [32]. |

| Conventional Annealing | ~200% more efficient | Sequential NVT and NPT ensembles across a wide temperature range (e.g., 300K to 1000K); iterative until target density is achieved [32]. |

| Lean Method | Baseline | Two-step process involving a long NPT simulation; less computationally intensive but slower to converge [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How long should I run an NPT simulation to be sure the system is equilibrated? There is no universal time. You must analyze the stability of key properties. A system exhibiting exponential relaxation with a characteristic time (Tc) of ~20 ns may require at least 100 ns (5*Tc) to fully equilibrate [31]. Do not rely solely on the mean and standard deviation; use statistical tests like linear regression to confirm a quantity is constant over time [31].

Q2: What are the best statistical methods to confirm equilibration? Beyond plotting energies and density, you can use:

- Linear Regression: Perform a linear fit of the potential energy (or density) against time. A statistically significant slope indicates the property is still drifting [31].

- Normality Tests: Use tests like Kolmogorov-Smirnov or Shapiro-Wilk on the data. If the values are not normally distributed around a mean, the system may not be equilibrated [31].

- Kurtosis Analysis: Calculate the kurtosis of the property. A value lower than 3 (negative excess kurtosis) can indicate a drifting mean [31].

Q3: My system is a confined fluid (e.g., in a pore or slit). Why is equilibration so slow? Confined systems have a rugged potential energy landscape. Molecules require large energy fluctuations to "jump" between stable configurations, which are statistically rare in plain MD simulations. A recommended solution is to combine your MD simulation with occasional Monte Carlo (MC) displacement or rotation moves to enhance sampling [31].

Q4: What is a Verlet buffer and how does it relate to energy drift? In the Verlet cut-off scheme, a buffered pair list is used to avoid rebuilding the neighbor list every step. The pair-list cut-off is larger than the interaction cut-off. If particles move into the interaction cut-off between list updates, it can cause a small energy drift. GROMACS can automatically determine the buffer size based on a tolerance for this energy drift (default is 0.005 kJ/mol/ps per particle) [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions for MD Equilibration

The following table details key components and their functions in setting up and running stable MD equilibration simulations.

| Item | Function / Role in Equilibration |

|---|---|

| Initial Coordinates | The starting 3D atom positions. A configuration too far from equilibrium can drastically increase equilibration time or trap the system in a meta-stable state. |

| Initial Velocities | The starting atomic velocities, often generated from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature to initialize kinetic energy [33]. |

| Force Field | Defines the potential energy function (bonded and non-bonded interactions). The choice of force field is critical for achieving physically meaningful equilibrium properties [33]. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Nose-Hoover) | Regulates the system's temperature by scaling velocities or coupling to a heat bath, essential for maintaining a stable NVT or NPT ensemble. |

| Barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) | Regulates the system's pressure by adjusting the simulation box size and shape, essential for the NPT ensemble. |

| Neighbor Searching Algorithm | Efficiently finds atom pairs within the interaction cut-off. Schemes like the buffered Verlet list are O(N) complexity and prevent energy drift [33]. |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Mimics a bulk environment by replicating the simulation box in all directions, eliminating surface effects. The box vectors (b1, b2, b3) must be defined [33]. |

FAQs: Solving System Instability in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

FAQ 1: My simulation crashed shortly after switching from equilibration to production run. The pressure was fluctuating wildly. What went wrong?

A common cause is an overly aggressive barostat. The Berendsen barostat is excellent for equilibration but does not produce correct fluctuations for production runs [34] [35]. For production, switch to a barostat that properly samples the NPT ensemble, such as the Nosé-Hoover (MTTK) or the stochastic Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello barostat [34] [36]. Furthermore, ensure your barostat's relaxation time (tau_p) is appropriately chosen; a value that is too small can cause violent, unstable oscillations in the box volume [35]. Typical values range from 0.5 to 4.0 ps, often starting around 1.5 ps [35].

FAQ 2: My simulation is stable, but my computed diffusion coefficients are incorrect. Could my thermostat be the cause?

Yes. Some thermostats, like the Langevin thermostat, apply a damping force that interferes with momentum transfer, which makes them unsuitable for calculating dynamical properties like diffusion coefficients [35]. For such properties, use a thermostat that preserves the dynamics of the system, such as the Nosé-Hoover thermostat [35].

FAQ 3: How can I tell if my system has been properly equilibrated before starting production?

Do not rely on a single metric like RMSD. A flat RMSD curve does not guarantee proper equilibration [14]. You should verify that key thermodynamic properties—including temperature, pressure, total energy, potential energy, and system density—have stabilized and formed consistent plateaus [14]. Monitoring the radius of gyration and hydrogen bond networks can provide additional confirmation [14].

FAQ 4: I am getting "flying ice cube" warnings in my logs. What does this mean, and is it a problem?

The "flying ice cube" effect is an artefact of some thermostats (like the Berendsen thermostat) where the kinetic energy is not properly partitioned across all degrees of freedom [35]. This can lead to the unphysical accumulation of kinetic energy in the global translational motions of the entire system, effectively causing it to "fly" while internal motions "freeze" [35]. This is a serious problem for production runs because it does not sample the correct ensemble. Modern implementations often counteract this by default, but switching to a more robust thermostat like Nosé-Hoover or Bussi is recommended for production simulations [35].

FAQ 5: My protein's RMSD is showing large, sudden jumps. Is this a sign of unfolding or a technical issue?

Before concluding that your protein is unfolding, rule out periodic boundary condition (PBC) artefacts [14] [2]. A molecule that crosses the simulation box boundary can appear to have a large, sudden jump in RMSD. Most MD software includes tools to correct for this. In GROMACS, for example, you can use gmx trjconv -pbc mol followed by gmx trjconv -pbc nojump to make molecules whole and remove these jumps before analysis [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unstable pressure and simulation crash during the NPT phase.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Overly aggressive barostat: A barostat relaxation time (

tau_p) that is too short applies corrections too vigorously, leading to large, uncontrolled volume oscillations [35].- Solution: Increase the

tau_pparameter. Start with a value around 1.5 ps and adjust as needed [35].

- Solution: Increase the

- Large pressure difference: If the difference between the initial internal pressure and the target pressure is very large, the barostat will try to adjust the volume too quickly, which can crash the simulation [34].

- Incorrect barostat for production:

- Solution: Use the Berendsen barostat for rapid equilibration, but always switch to a more robust barostat like Parrinello-Rahman, MTTK, or Stochastic Cell Rescaling for production simulations to ensure correct sampling [34].

Problem: The simulation temperature is stable, but the energy distribution is incorrect.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Use of a non-ensemble thermostat: The Berendsen thermostat is known to produce incorrect kinetic energy distributions and should not be used for production sampling [37] [35].

- Incorrect thermostat chain length: When using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat, a short chain length can lead to poor ergodicity, especially in small systems.

Problem: Incompatible integrator and barostat combination.

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Some advanced integrators have specific requirements for the barostat. For example, a user encountered a fatal error when trying to combine the

md-vv(velocity Verlet) integrator with the Parrinello-Rahman barostat in GROMACS, as this combination was only available in a different simulator module [38].- Solution: Consult your MD software manual carefully. If you encounter such an error, you may need to switch to a different pressure control algorithm (e.g., from Parrinello-Rahman to MTTK) that is compatible with your chosen integrator [38].

Comparison of Thermostat and Barostat Algorithms

Table 1: Comparison of common thermostat algorithms.

| Thermostat | Ensemble Sampled | Strengths | Weaknesses | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen [37] [35] | Not a true NVT ensemble [35]. | Very efficient for equilibration; rapidly drives system to target temperature [34] [35]. | Produces incorrect energy distributions; can cause "flying ice cube" effect; non-ergodic [37] [35]. | Initial equilibration only [35]. |

| Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello (Stochastic Velocity Rescaling) [37] [36] | Correctly samples the NVT ensemble (canonical) [37]. | Efficiently thermalizes the system; correct sampling; good for small and large systems [37]. | Stochastic (random) component means results are not perfectly reproducible without identical random seeds [37]. | All stages, including production [37]. |

| Nosé-Hoover [34] [37] [35] | Correctly samples the NVT ensemble (canonical) [35]. | Considered a "gold standard"; deterministic (reproducible) [35]. | Can have ergodicity issues in small systems; requires a thermostat chain for complex systems [34] [37]. | Production runs for condensed matter systems [35]. |

| Langevin [35] | Correctly samples the NVT ensemble [35]. | Very stable; allows for larger timesteps; good for biological systems [35]. | Damping force disrupts momentum, so cannot be used to compute diffusion coefficients [35]. | Systems where hydrodynamic properties are not the focus [35]. |

Table 2: Comparison of common barostat algorithms.

| Barostat | Ensemble Sampled | Typical τ_p (ps) | Strengths | Weaknesses | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen [34] [35] | Not a true NPT ensemble [34]. | 0.5 - 4.0 [35] | Very efficient for equilibration and relaxing the system density [34] [35]. | Suppresses pressure fluctuations; induces artefacts in inhomogeneous systems; should not be used for production [34]. | Initial equilibration only [34]. |

| Stochastic Cell Rescaling (Bernetti-Bussi) [34] [36] | Correctly samples the NPT ensemble (isobaric-isothermal) [36]. | N/A | An improved Berendsen barostat; converges fast without oscillations; correct fluctuations [34] [36]. | Stochastic method [36]. | All stages, including production [34]. |

| Parrinello-Rahman [34] | Correctly samples the NPT ensemble [34]. | 2.0 (as in example) [38] | Allows changes in box shape; useful for studying solids under stress [34]. | Volume may oscillate with a frequency proportional to the piston mass [34]. | Production runs, especially for solids or anisotropic systems [34]. |

| MTTK (Martyna-Tobias-Klein) [34] [37] | Correctly samples the NPT ensemble [34]. | N/A | Extension of Nosé-Hoover; performs better for small systems [34]. | Oscillations can be an issue; the similar Langevin piston barostat converges faster due to stochastic damping [34]. | Production runs, particularly for small systems [34]. |

Experimental Protocol for a Stable Production Run

This protocol outlines the steps to transition from a minimized structure to a stable production run in the NPT ensemble, emphasizing the selection of thermostats and barostats.

1. System Minimization

- Objective: Remove steric clashes and high-energy interactions from the initial structure [14].

- Method: Use a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to minimize the system's energy until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) [14].

2. Initial Equilibration (NVT)

- Objective: Gently heat the system to the target temperature while keeping the volume fixed.

- Thermostat: Use the Berendsen thermostat for its rapid and efficient coupling [35].

- Parameters: Set

tau_tto a moderate value (e.g., 0.5 - 1.0 ps) [35]. Run until the temperature stabilizes around the target value.

3. Density Equilibration (NPT)

- Objective: Allow the system density to adjust to the target temperature and pressure.

- Thermostat & Barostat: Use the Berendsen thermostat and barostat for their stability and efficiency during this relaxation phase [34] [35].

- Parameters: Set