Measuring Teleological Reasoning in Evolution: Assessment Tools, Validation Strategies, and Applications for Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary tools and methodologies for assessing teleological reasoning in evolutionary biology.

Measuring Teleological Reasoning in Evolution: Assessment Tools, Validation Strategies, and Applications for Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary tools and methodologies for assessing teleological reasoning in evolutionary biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the cognitive foundations of teleological bias, details quantitative and qualitative assessment methods, and addresses challenges in implementation. The scope covers foundational concepts, methodological applications, strategies for optimizing reliability, and comparative validation of emerging automated scoring technologies, including traditional machine learning and Large Language Models. The synthesis offers critical insights for developing robust assessment frameworks in scientific research and education, with implications for fostering accurate causal reasoning in biomedical contexts.

Understanding Teleological Reasoning: Cognitive Foundations and Research Imperatives

Teleological explanations describe biological features and processes by referencing their purposes, functions, or goals [1]. In biology, it is common to state that "bones exist to support the body" or "the immune system fights infections so that the organism survives" [1]. These explanations are characterized by their use of telos (a Greek term meaning 'end' or 'purpose') to account for why organisms possess certain traits [1] [2]. While such purposive language is largely absent from other natural sciences like physics, it remains pervasive and arguably indispensable in biological sciences [1] [3].

The central philosophical puzzle lies in reconciling this purposive language with biology's status as a natural science. Physicists do not claim that "rivers flow so that they can reach the sea" – such phenomena are explained through impersonal forces and prior states [1]. Teleological explanations in biology, therefore, require careful naturalization to avoid invoking unscientific concepts such as backward causation, vital forces, or conscious design in nature [3] [4].

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Historical Context and Modern Interpretations

Historically, teleology was associated with creationist views, where organisms were considered designed by a divine creator [2]. William Paley's Natural Theology (1802), with its famous watchmaker analogy, argued that biological complexity evidenced a benevolent designer [2]. Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection provided a naturalistic alternative, explaining adaptation through mechanistic processes rather than conscious design [3] [2].

Modern approaches seek to "naturalize" teleology, grounding it in scientifically acceptable concepts [3]. Two primary frameworks dominate contemporary discussion:

Table 1: Theoretical Frameworks for Naturalizing Teleology

| Framework | Core Principle | Proponents/Influences |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Approaches [1] [3] | A trait's function is what it was selected for in evolutionary history. The function of the heart is to pump blood because ancestors with better pumping hearts had higher fitness. | Ernst Mayr, Larry Wright |

| Present-Focused Approaches [1] | A trait's function is the current causal role it plays in maintaining the organism's organization and survival. | Robert Cummins |

A significant terminological development was Pittendrigh's (1958) introduction of teleonomy to distinguish legitimate biological function-talk from metaphysically problematic teleology [5] [4]. Teleonomy refers to the fact that organisms, as products of natural selection, have goal-directed systems without implying conscious purpose or backward causation [5].

Classification of Teleological Explanations

Francisco Ayala proposes a useful classification of teleological explanations relevant for empirical testing [6]. He distinguishes between:

- Natural vs. Artificial: Artificial teleology applies to human-made objects (a knife's purpose is to cut), while natural teleology applies to biological traits without a conscious designer [6].

- Bounded vs. Unbounded: Bounded teleology explains traits with specific, limited goals (e.g., physiological processes), while unbounded teleology might be misapplied to evolution as a whole [6].

Assessment Tools and Protocols for Teleological Reasoning

Research on conceptual understanding in biology education has developed robust methods for assessing teleological reasoning, which can be adapted for research settings.

Protocol: Eliciting and Categorizing Teleological Statements

Objective: To identify and classify the types of teleological reasoning employed by students or research participants regarding evolutionary and biological phenomena.

Materials:

- Pre-designed prompts or interview questions about biological traits (e.g., "Why do giraffes have long necks?" or "How did the polar bear's white fur evolve?")

- Audio recording equipment or written response forms

- Coding scheme based on established categories [5] [4]

Procedure:

- Stimulus Presentation: Present participants with biological scenarios or questions. Avoid leading language. Use both open-ended ("Why...?") and function-prompting ("What purpose might X serve?") questions to detect reasoning shifts [5].

- Data Collection: Record participants' explanations verbatim.

- Data Analysis and Coding: Code responses according to a defined schema. Key distinctions include:

- Need-Based vs. Desire-Based: Does the explanation reference an organism's survival needs or attribute conscious desires? [5]

- Proximate vs. Ultimate Causation: Does the explanation reference immediate mechanisms (proximate) or evolutionary history and function (ultimate)? [5]

- Adequate vs. Inadequate Teleology: Does the explanation correctly link a trait's function to its evolutionary history via natural selection, or does it posit the function or a need as the direct cause of the trait's origin? [4]

Table 2: Coding Schema for Teleological Explanations

| Code Category | Sub-Category | Example Explanation | Adequacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need-Based | Basic Need | "The neck grew long so that the giraffe could reach high leaves." | Inadequate |

| Restricted Teleology | "The white fur evolved for camouflage in order to survive." | Requires further probing | |

| Function-Based | Selected Effect | "White fur became common because it provided camouflage, which helped ancestors survive and reproduce." | Adequate |

| Mentalistic | Desire-Based | "The giraffe wanted to reach higher leaves, so it stretched its neck." | Inadequate |

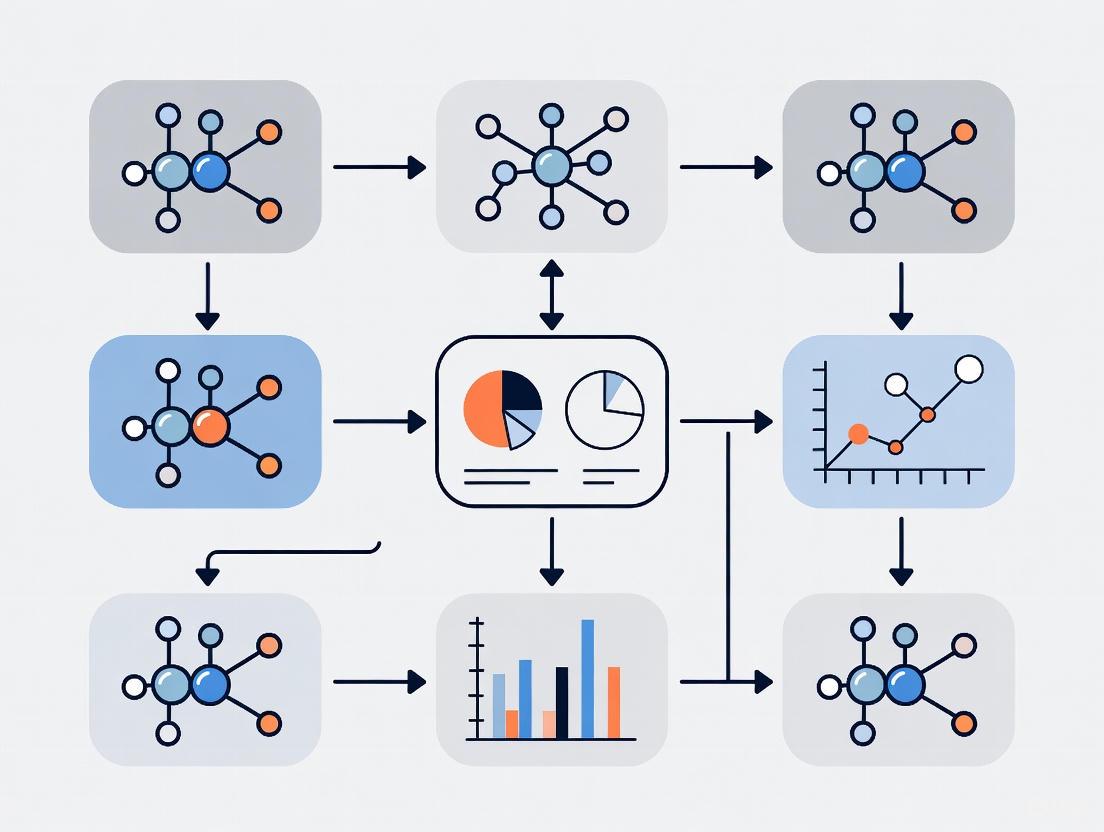

Method: Causal Mapping for Conceptual Change

Objective: To visualize and clarify the causal relationships in evolutionary processes, helping participants distinguish between adequate functional reasoning and inadequate teleological reasoning [5].

Background: Causal mapping is a teaching tool that makes explicit the role of behavior and other factors in evolution. It helps link everyday experiences of goal-directed behavior to the population-level, non-goal-directed process of natural selection [5].

Workflow: The methodology involves guiding participants through the creation of a visual map that traces the causal pathway of evolutionary change, incorporating key concepts like variation, selection, and inheritance.

Causal Map of Evolutionary Change

Implementation Protocol:

- Introduction: Introduce a specific evolutionary scenario (e.g., evolution of antibiotic resistance).

- Node Identification: Have participants identify key causal nodes (e.g., random mutation in bacteria, presence of antibiotic, reproductive success of resistant bacteria).

- Linking: Guide participants in drawing directional arrows between nodes to establish causality.

- Labeling: Ensure participants label the arrows with the nature of the relationship (e.g., "causes differential survival," "leads to increased frequency in population").

- Discussion and Refinement: Use the map to discuss why certain causal paths are incorrect (e.g., "the need for resistance causes the mutation") and which are supported by evidence.

Quantitative Data Analysis and Interpretation

When analyzing data from assessments of teleological reasoning, researchers should employ structured methods to categorize and quantify responses.

Data Visualization for Assessment Analysis

Effective visualization is key to exploring and presenting data on teleological reasoning. SuperPlots are particularly useful for displaying data that captures variability across biological repeats or different participant groups [7]. They combine individual data points with summarized distribution information, providing a clear view of trends and variability.

Recommended Tools:

- R with ggplot2: The

ggplot2package, based on the "grammar of graphics," allows for flexible and sophisticated creation of plots like SuperPlots, dot plots, and box plots [7] [8]. - Python with Matplotlib/Seaborn: Python's data visualization libraries offer robust ecosystems for creating customizable charts and statistical graphics [7].

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics for Scoring Teleological Reasoning

| Metric | Description | Measurement Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Teleological Tendency Score | Frequency of teleological formulations in explanations. | Count or percentage of teleological statements per response. |

| Adequacy Index | Proportion of teleological statements that are biologically adequate (e.g., reference natural selection correctly). | Ratio (Adequate Statements / Total Teleological Statements). |

| Causal Accuracy | Score reflecting the correct identification of causal agents in evolutionary change (e.g., random mutation vs. organismal need). | Ordinal scale (e.g., 1-5 based on rubric). |

| Conceptual Complexity | Measure of the number of key evolutionary concepts (variation, inheritance, selection) integrated into an explanation. | Count of concepts present. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials and conceptual tools for research into teleological reasoning.

Table 4: Key Reagents for Research on Teleological Reasoning

| Item/Tool | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Interview Protocols | To elicit and record participant explanations in a consistent, comparable format. | Protocols from studies by Kelemen (2012) or Legare et al. (2013) can be adapted [5] [4]. |

| Validated Concept Inventories | To quantitatively assess understanding of evolution and identify teleological misconceptions. | Use established instruments like the Concept Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS). |

| Causal Mapping Software | To create and analyze visual causal models generated by participants. | Tools like CMapTools or even general diagramming software (e.g., draw.io) can be used. |

| R or Python with Qualitative Analysis Packages | To code, categorize, and statistically analyze textual and verbal response data. | R packages (e.g., tidyverse for data wrangling, ggplot2 for plotting) or Python (e.g., pandas, scikit-learn) are essential [7]. |

| Coding Scheme Rubric | A detailed guide for consistently classifying responses into teleological categories. | The rubric should be based on a firm theoretical foundation (e.g., distinguishing ontological vs. epistemological telos) [4]. |

Teleological explanations, when properly naturalized within the framework of evolutionary theory, are a legitimate and powerful tool in biology. The assessment protocols, causal mapping methods, and analytical tools outlined in these application notes provide researchers with a structured approach to investigate how teleological reasoning manifests and how it can be guided toward scientifically adequate conceptions. By clearly distinguishing between the epistemological utility of functions and the ontological fallacy of purposes in nature, researchers and educators can better navigate the complexities of teleological language in biological sciences.

This section provides a consolidated summary of key quantitative findings related to essentialist and teleological reasoning in evolution education.

Table 1: Prevalence and Impact of Cognitive Biases in Evolution Education

| Bias Type | Key Characteristics | Prevalence/Impact Findings | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teleological Reasoning | Attributing purpose or goals to natural phenomena; viewing evolution as forward-looking [9] [10]. | Lower levels predict learning gains in natural selection (p < 0.05) [10]. | Undergraduate evolutionary medicine course [10]. |

| Essentialist Reasoning | Assuming species members share a uniform, immutable essence; ignoring within-species variation [9] [11]. | Underlies one of the most challenging aspects of understanding natural selection: the importance of individual variability [9]. | Investigation of undergraduate students' explanations of antibiotic resistance [9]. |

| Genetic Essentialism | Interpreting genetic effects as deterministic, immutable, and defining homogeneous groups [12]. | In obesity discourse, when genetic info is invoked, it is often presented in a biased way [12]. | Analysis of ~26,000 Australian print media articles on obesity [12]. |

| Anthropocentric Reasoning | Reasoning by analogy to humans, exaggerating human importance or projecting human traits [9]. | Intuitive reasoning was present in nearly all students' written explanations of antibiotic resistance [9]. | Undergraduate explanations of antibiotic resistance [9]. |

Table 2: Efficacy of Interventions Targeting Cognitive Biases

| Intervention Type | Target Audience | Key Outcome | Significance/Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Misconception-Focused Instruction (MFI) | Undergraduate students [13] | Higher doses of MFI (up to 13% of class time) associated with greater evolution learning gains and attenuated misconceptions [13]. | MFI creates opportunities for cognitive dissonance to correct biased reasoning [13]. |

| Correcting Generics & Highlighting Function Variability | 7- to 8-year-old U.S. children [11] | Children viewed more average category members as prototypical, reducing idealized prototypes [11]. | Explanations about varied functions alone explained the effect for novel animals [11]. |

| Directly Challenging Design Teleology | Undergraduate students with creationist views [13] | Significant (p < 0.01) improvements in teleological reasoning and acceptance of human evolution [13]. | Students with creationist views never achieved the same levels of understanding/acceptance as naturalist students [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Assessment and Intervention

This section details standardized methodologies for measuring essentialist and teleological biases and for implementing corrective interventions.

Protocol: Assessing Teleological and Essentialist Reasoning Using the ACORNS Instrument

Application Note: The Assessment of COntextual Reasoning about Natural Selection (ACORNS) is a validated tool for uncovering student thinking about evolutionary change across biological phenomena via written explanations [14].

- Objective: To detect and code the presence of normative (scientific) and non-normative (including teleological and essentialist) reasoning elements in written evolutionary explanations.

Materials:

Procedure:

- Administration: Provide participants with an ACORNS prompt featuring a novel evolutionary scenario.

- Data Collection: Collect text-based explanations from participants.

- Human Scoring:

- Score each explanation using the standardized rubric for nine key concepts.

- Normative Concepts: Variation, Heritability, Differential Survival/Reproduction, Limited Resources, Competition, Non-Adaptive Factors.

- Non-Normative Concepts (Misconceptions):

- Establish inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.81 is a robust target) [14].

- (Alternative) Automated Scoring: Input student responses into the EvoGrader system for machine-learning-based scoring, which has demonstrated performance matching or exceeding human inter-rater reliability [14].

Protocol: Intervention to Attenuate Teleological Reasoning in a Human Evolution Course

Application Note: This protocol employs direct, reflective confrontation of design teleology to facilitate conceptual change, particularly effective in a human evolution context [13].

- Objective: To significantly reduce students' endorsement of design teleological reasoning and improve their understanding and acceptance of natural selection.

Materials:

- Pre- and post-surveys: Measure teleological reasoning (e.g., design teleology statements), understanding (Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection - CINS), and acceptance (Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance - I-SEA) [13].

- Reflective writing prompts (e.g., "Reflect on a time you thought about a biological trait as 'designed for a purpose.' How would you explain it now using evolutionary mechanisms?") [13].

- Active learning worksheets with statements featuring design teleology for students to critique and correct.

Procedure:

- Pre-Assessment: Administer surveys at the course start to establish baseline levels of teleological reasoning, understanding, and acceptance.

- Explicit Instruction:

- Directly contrast design teleological reasoning (e.g., "Bacteria become resistant in order to survive antibiotics") with veridical evolutionary mechanisms (e.g., "Random mutation generates variation; antibiotics select for resistant individuals") [9] [13].

- Differentiate true teleology (in artifact design) from its misapplication in evolution [13].

- Active Learning Activities:

- Correction Tasks: Provide students with short passages containing design teleology statements. Students work individually or in groups to identify and rewrite the statements using scientifically accurate mechanistic language [13].

- Contrast Tasks: Present students with paired explanations (one teleological, one mechanistic) for the same trait and facilitate discussion on their differences, underlying assumptions, and evidentiary support.

- Reflective Writing: Assign reflective essays prompting students to articulate their understanding of teleological reasoning and how their thinking about evolutionary processes has changed [13].

- Post-Assessment & Analysis: Re-administer surveys at the course end. Analyze pre-post changes using paired t-tests or similar statistical methods to evaluate intervention efficacy [13].

Protocol: LLM-Assisted Analysis of Genetic Essentialist Biases in Text Corpora

Application Note: This protocol leverages Large Language Models (LLMs) for large-scale detection of a specific essentialist bias—genetic essentialism—in textual data [12].

- Objective: To semi-automatically classify large volumes of text (e.g., media articles, student writing) for the presence of genetic essentialist (GE) biases.

Materials:

- Text corpus (e.g., .csv or .txt files containing the target articles or responses).

- Dar-Nimrod and Heine's (2011) GE bias framework defining four sub-components: Determinism, Specific Aetiology, Naturalism, and Homogeneity [12].

- Pre-defined LLM (e.g., GPT-4) prompts engineered to classify text based on the GE framework.

- (Validation) Human expert-scored subset of the corpus.

Procedure:

- Task and Class Specification: Define the classification task for the LLM based on the four GE biases [12].

- Prompt Engineering: Develop and iteratively refine prompts that instruct the LLM to read a text segment and identify the presence or absence of each GE bias, providing definitions and examples.

- Model Deployment: Run the target text corpus through the LLM using the finalized prompts to generate bias classifications for each text item.

- Validation:

- A subset of the corpus (e.g., 100-200 items) is independently scored by human experts using the same GE framework.

- Calculate inter-rater reliability (e.g., percentage agreement, Krippendorf's alpha) between the LLM and human experts to ensure the model detects biases as reliably as human experts [12].

- Quantitative Analysis: Use the validated LLM classifications to quantify the frequency and co-occurrence of different GE biases across the entire corpus.

Table 3: Key Assessment Tools and Reagents for Studying Cognitive Biases

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Bias Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACORNS Instrument | Assessment Instrument | Elicits written explanations of evolutionary change [14]. | Flags non-normative reasoning, including need-based teleology and transformational (essentialist) change [14]. |

| EvoGrader | Automated Scoring System | Machine-learning-based online tool for scoring ACORNS responses [14]. | Enables large-scale, rapid identification of teleological and essentialist misconceptions in student writing [14]. |

| Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Assessment Instrument | Multiple-choice test measuring understanding of natural selection fundamentals [10]. | Provides a validated measure of learning gains, used to correlate with levels of teleological reasoning [10]. |

| Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance (I-SEA) | Assessment Instrument | Multi-dimensional scale measuring acceptance of evolution in different contexts [13]. | Tracks changes in evolution acceptance, particularly relevant when intervening with religious or creationist students [13]. |

| Dar-Nimrod & Heine GE Framework | Conceptual Framework | Defines four sub-components of genetic essentialism: Determinism, Specific Aetiology, Naturalism, Homogeneity [12]. | Provides the theoretical basis for coding textual data for nuanced essentialist biases, usable by both human coders and LLMs [12]. |

| Validated Teleology Scale | Assessment Instrument | Survey instrument measuring endorsement of design teleological statements [13] [10]. | Quantifies the strength of teleological reasoning before and after educational interventions [13] [10]. |

Quantitative Data on Worldview, Teleology, and Evolution Understanding

The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from research exploring the relationships between religious views, teleological reasoning, and the understanding of evolutionary concepts.

Table 1: Pre-Instruction Differences Between Student Groups [13]

| Metric | Students with Creationist Views | Students with Naturalist Views | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Teleological Reasoning | Higher levels | Lower levels | < 0.01 |

| Acceptance of Evolution | Lower levels | Higher levels | < 0.01 |

| Acceptance of Human Evolution | Lower levels | Higher levels | < 0.01 |

Table 2: Impact of Educational Intervention on Student Outcomes [13]

| Student Group | Change in Teleological Reasoning | Change in Acceptance of Human Evolution | Post-Course Performance vs. Naturalist Peers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creationist Views | Significant improvement (p < 0.01) | Significant improvement (p < 0.01) | Underperformed; never achieved parity |

| Naturalist Views | Significant improvement (p < 0.01) | (Implied improvement) | (Baseline for comparison) |

Table 3: Predictors of Evolution Understanding and Acceptance [13]

| Factor | Relationship with Evolution Understanding | Relationship with Evolution Acceptance |

|---|---|---|

| Student Religiosity | Significant negative predictor | Not a significant predictor |

| Creationist Views | Not a significant predictor | Significant negative predictor |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Teleological Reasoning

Protocol: Pre-Post Quantitative Assessment of Teleological Reasoning

Objective: To quantitatively measure changes in participants' endorsement of design-based teleological reasoning before and after an educational intervention.

Materials:

- Pre- and post-intervention survey instruments.

- Validated scales for measuring teleological reasoning (e.g., assessing agreement with statements like "Traits evolved to fulfill a need of the organism").

- Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance (I-SEA).

- Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS).

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved informed consent forms.

Procedure:

- Recruitment: Recruit participant cohort (e.g., undergraduate students enrolled in an evolution-related course).

- Pre-Test Administration: Distribute the pre-intervention survey package (teleology scale, I-SEA, CINS) at the beginning of the semester or research study.

- Educational Intervention: Implement the planned intervention. Example interventions include:

- A human evolution course that explicitly addresses and challenges design teleological reasoning.

- Active learning activities where students correct design teleology statements.

- Lessons contrasting design teleology with veridical evolutionary mechanisms.

- Post-Test Administration: Distribute the identical survey package at the end of the intervention period.

- Data Analysis:

- Use paired t-tests or ANOVA to compare pre- and post-scores for the entire cohort and for subgroups (e.g., creationist vs. naturalist views).

- Employ multiple linear regression to identify predictors (e.g., religiosity, pre-existing creationist views) of understanding and acceptance scores.

Protocol: Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Reflective Writing

Objective: To gain a deeper, qualitative understanding of how students perceive the relationship between their worldview and evolutionary theory.

Materials:

- Reflective writing prompts (e.g., "Discuss your understanding and acceptance of natural selection and teleological reasoning").

- Qualitative data analysis software (e.g., NVivo).

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Assign reflective writing exercises during or after the educational intervention.

- Familiarization: Read and re-read the written responses to gain familiarity with the data.

- Initial Coding: Generate initial codes that identify key phrases and ideas related to teleology, religiosity, and evolution.

- Theme Development: Collate codes into potential themes (e.g., "Perceived Incompatibility of Religion and Evolution," "Openness to Coexistence").

- Theme Review: Check if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts and the entire dataset.

- Analysis: Produce a thematic analysis report, integrating quantitative findings with qualitative themes to provide a mixed-methods conclusion.

Visualization of Conceptual Relationships and Workflows

Conceptual Framework of Design Teleology in Evolution Education

Experimental Workflow for Mixed-Methods Research

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Teleology Assessment

Table 4: Key Instruments and Analytical Tools for Research

| Tool Name | Type/Purpose | Brief Function Description |

|---|---|---|

| Teleological Reasoning Scale | Assessment Instrument | Quantifies endorsement of design-based explanations for natural phenomena [13]. |

| Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance (I-SEA) | Assessment Instrument | Measures acceptance of evolution across microevolution, macroevolution, and human evolution subdomains [13]. |

| Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Assessment Instrument | Assesses understanding of key natural selection concepts [13]. |

| GraphPad Prism | Analytical Software | Streamlines statistical analysis and graphing of quantitative data from pre-/post-tests; simplifies complex experimental setups [15]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software (e.g., NVivo) | Analytical Software | Aids in the thematic analysis of qualitative data from reflective writing and interviews [13]. |

Teleological reasoning represents a significant conceptual barrier to a mechanistic understanding of natural selection. This cognitive bias manifests as the tendency to explain biological phenomena by reference to future goals, purposes, or functions, rather than by antecedent causal mechanisms [4]. In evolutionary biology, this often translates into students assuming that traits evolve because organisms "need" them for a specific purpose, fundamentally misunderstanding the causal structure of natural selection [10]. For instance, when students explain the evolution of the giraffe's long neck by stating that "giraffes needed long necks to reach high leaves," they engage in teleological reasoning by invoking a future need as the cause of evolutionary change, rather than the actual mechanism of random variation and differential survival [10].

The core issue lies in the conflation of two distinct notions of telos (Greek for 'end' or 'goal'). Biologists legitimately use function talk as an epistemological tool to describe how traits contribute to survival and reproduction (teleonomy), while students often misinterpret this as evidence of ontological purpose in nature (teleology) [4]. This conceptual confusion leads to what philosophers of science have identified as problematic "backwards causation," where future outcomes (like being better adapted) are mistakenly seen as causing the evolutionary process, rather than resulting from it [1] [16]. The persistence of this reasoning pattern is well-documented across educational levels, appearing before, during, and after formal instruction in evolutionary biology [4].

Assessment Frameworks: Measuring Teleological Tendencies

Quantitative Instrumentation and Scoring Metrics

Table 1: Primary Assessment Instruments for Teleological Reasoning

| Instrument Name | Measured Construct | Item Format & Sample Items | Scoring Methodology | Validation Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teleological Reasoning Scale (TRS) | General tendency to endorse teleological explanations | Likert-scale agreement with statements like "Birds evolved wings in order to fly" | Summative score (1-5 scale); higher scores indicate stronger teleological tendencies | Used in [10]; shows predictive validity for learning natural selection |

| Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Understanding of natural selection mechanisms; detects teleological misconceptions | Multiple-choice questions with distractors reflecting common teleological biases | Correct answers scored +1; teleological distractors identified and tracked | Anderson et al. (2002); validated with pre-post course designs [10] |

| Open-Ended Explanation Analysis | Spontaneous use of teleological language in evolutionary explanations | Written responses to prompts like "Explain how polar bears evolved white fur" | Coding protocol for key phrases: "in order to," "so that," "needed to," "for the purpose of" | Qualitative coding reliability established through inter-rater agreement metrics [4] |

Research using these instruments has revealed that teleological reasoning is not merely a proxy for non-acceptance of evolution. In one controlled study, lower levels of teleological reasoning predicted learning gains in understanding natural selection over a semester-long course, while acceptance of evolution did not [10]. This distinction underscores the cognitive rather than purely cultural or attitudinal nature of the obstacle. The assessment protocols consistently show that teleological reasoning distorts biological relationships between mechanisms and functions, with students providing the function of a trait as the one and only causal factor for how the trait came into existence without linking it to evolutionary selection mechanisms [4].

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Teleological Reasoning

Protocol 1: Dual-Prompt Assessment for Detecting Teleological Bias

- Objective: To distinguish between functional biological reasoning and inadequate teleological reasoning in evolutionary explanations.

- Materials: Standardized assessment booklet, demographic questionnaire, timing device.

- Procedure:

- Pre-assessment (5 minutes): Administer the Teleological Reasoning Scale (TRS) to establish baseline tendency.

- Scenario Presentation (10 minutes): Present two evolutionary scenarios:

- Scenario A: Adaptation (e.g., "Explain how antibiotic resistance in bacteria evolves")

- Scenario B: Origin of Novel Trait (e.g., "Explain how feathers first evolved in dinosaurs")

- Written Response (15 minutes): Participants provide written explanations for both scenarios.

- Forced-Choice Follow-up (5 minutes): Participants select between paired explanations:

- Option 1 (Mechanistic): "Random mutations created genetic variation. Bacteria with resistance genes survived antibiotic treatment and reproduced more."

- Option 2 (Teleological): "Bacteria needed to become resistant to survive, so they developed resistance in response to the antibiotic."

- Post-hoc Interview (Optional, 15 minutes): Subset of participants elaborates on reasoning.

- Analysis:

- Quantitative: Score CINS and TRS instruments per standardized protocols.

- Qualitative: Code written responses using teleological language framework.

- Statistical: Correlate TRS scores with preference for teleological forced-choice options.

This protocol's experimental workflow is designed to capture both explicit and implicit teleological reasoning through multiple measurement approaches:

Cognitive and Conceptual Underpinnings

Psychological Origins and Philosophical Foundations

Teleological reasoning finds its roots in domain-general cognitive biases that emerge early in human development. Cognitive psychology explains these tendencies through dual-process models, which distinguish between intuitive reasoning processes (fast, automatic, effortless) and reflective reasoning processes (slow, deliberate, requiring conscious attention) [4]. The intuitive appeal of teleological explanations represents a default reasoning mode that must be overridden through reflective, scientific thinking [10]. This tendency is so pervasive that some philosophers, following Kant, have suggested we inevitably understand living things as if they are teleological systems, though this may reflect our cognitive limitations rather than reality [16].

The philosophical problem centers on whether purposes, functions, or goals can be legitimate parts of causal explanations in biology. While physicists do not claim that "rivers flow so they can reach the sea," biologists routinely make statements like "the heart beats to pump blood" [1]. The challenge lies in naturalizing teleological language without resorting to unscientific notions like backwards causation or intelligent design. Evolutionary theory addresses this by providing a naturalistic framework for understanding function through historical selection processes, yet students consistently struggle with this conceptual shift [16].

Conceptual Mapping of Teleological Reasoning

The relationship between different forms of teleological reasoning and their appropriate scientific counterparts can be visualized as follows:

Research Reagents and Methodological Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Methodological Tools for Teleology Research

| Tool Category | Specific Instrument | Primary Function in Research | Key Characteristics & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validated Surveys | Teleological Reasoning Scale (TRS) | Measures general propensity to endorse teleological statements | 15-item Likert scale; validated with undergraduate populations; internal consistency α > 0.8 [10] |

| Conceptual Assessments | Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Identifies specific teleological misconceptions in evolutionary thinking | 20 multiple-choice items; teleological distractors systematically identified; pre-post test design [10] |

| Qualitative Coding Frameworks | Teleological Language Coding Protocol | Analyzes open-ended responses for implicit teleological reasoning | Codes for "in order to," "so that," "for the purpose of"; requires inter-rater reliability >0.8 [4] |

| Experimental Paradigms | Dual-Prompt Assessment | Distinguishes functional reasoning from inadequate teleology | Combines written explanations with forced-choice items; controls for acceptance vs. understanding [10] |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | R Statistical Environment with psych, lme4 packages | Analyzes complex relationships between variables | Computes correlation between TRS and learning gains; controls for religiosity, prior education [10] |

Intervention Protocol: Addressing Teleological Reasoning

Mechanism-Based Instructional Strategy

Protocol 2: Mechanism-Focused Intervention for Teleological Bias

- Objective: To redirect explanatory patterns from teleological to mechanistic reasoning in evolutionary biology.

- Target Audience: Undergraduate biology students, particularly those identified with high TRS scores.

- Duration: 3-week module integrated into evolutionary biology course.

- Instructional Sequence:

- Contrastive Cases (Week 1):

- Present paired examples: Artifact (designed with purpose) vs. Biological trait (evolved without purpose)

- Explicitly contrast "made for" language with "evolved by" language

- Highlight differences in causal structure using visual diagrams

- Mechanism Tracing (Week 2):

- Provide templates for mechanistic explanations: Variation → Environmental Pressure → Differential Reproduction → Inheritance

- Use worked examples with gradual fading of scaffolding

- Students practice identifying and labeling each component in novel scenarios

- Teleological Trap Identification (Week 3):

- Teach students to recognize common teleological patterns in their own thinking

- Provide explicit correction protocols for restructuring explanations

- Use metacognitive reflection prompts: "What was your first instinct? Why might it be misleading?"

- Contrastive Cases (Week 1):

- Materials:

- Contrastive case worksheets

- Mechanism tracing templates

- Worked examples with full and partial solutions

- Corrective feedback rubrics focusing on causal structure

- Assessment:

- Pre-post administration of CINS and TRS

- Analysis of explanation patterns in written responses

- Tracking reduction in teleological language use

This intervention protocol employs a conceptual change approach that specifically targets the cognitive mechanisms underlying teleological reasoning:

Implications for Research and Education

The documented impact of teleological reasoning on understanding evolutionary mechanisms carries significant implications for both biology education and experimental research design. In educational contexts, instructors should explicitly distinguish between the epistemological use of function as a productive biological heuristic and the ontological commitment to purpose in nature that constitutes problematic teleology [4]. Assessment strategies must be designed to detect subtle forms of teleological reasoning that persist even after students can correctly answer standard examination questions.

For research professionals, particularly in drug development and evolutionary medicine, understanding the distinction between functional analysis and teleological explanation is crucial when modeling evolutionary processes such as antibiotic resistance or cancer development. Teleological assumptions can lead to flawed predictive models that misrepresent the mechanistic basis of evolutionary change [17]. The assessment tools and intervention protocols outlined here provide a framework for identifying and addressing these conceptual barriers in both educational and research contexts.

Future research directions should include developing more sensitive assessment tools that can detect implicit teleological reasoning, designing targeted interventions for specific biological subdisciplines, and exploring the relationship between teleological reasoning and success in applied evolutionary fields such as medicinal chemistry or phylogenetic analysis.

Assessment Tools in Action: Quantitative and Qualitative Methodologies

A robust understanding of evolutionary theory is fundamental across the life sciences, from biology education to biomedical research and drug development. However, comprehending evolution is cognitively challenging due to deep-seated, intuitive reasoning biases. Teleological reasoning—the cognitive tendency to explain natural phenomena by reference to a purpose or end goal—is a primary obstacle to accurately understanding natural selection as a blind, non-goal-oriented process [18] [19]. To advance research and education, scientists have developed standardized instruments to quantitatively measure conceptual understanding and identify specific misconceptions. These tools, including specialized conceptual inventories, provide critical, high-fidelity data on mental models. They enable researchers to assess the effectiveness of educational interventions, evaluate training programs, and understand the cognitive underpinnings that may influence reasoning in professional settings, including the interpretation of biological data in drug development [20] [21].

Established Conceptual Assessment Instruments

Several rigorously validated instruments are available to probe understanding of evolutionary concepts and the prevalence of teleological reasoning. The table below summarizes key established tools.

Table 1: Established Conceptual Assessment Instruments for Evolution Understanding

| Instrument Name | Primary Construct Measured | Format & Target Audience | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CACIE (Conceptual Assessment of Children’s Ideas about Evolution) [21] | Understanding of variation, inheritance, and selection. | Interview-based; for young, pre-literate children. | 20 items covering 10 concepts; can be used with six different animal and plant species. |

| ACORNS (Assessing Contextual Reasoning about Natural Selection) [19] | Use of teleological vs. natural selection-based reasoning. | Open-ended written assessments; typically for older students and adults. | Presents evolutionary scenarios; responses are coded for teleological and mechanistic reasoning. |

| CINS (Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection) [19] | Understanding of core principles of natural selection. | Multiple-choice; for undergraduate students. | Validated instrument used to measure understanding and acceptance of evolution. |

| I-SEA (Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance) [19] | Acceptance of evolutionary theory. | Likert-scale survey; for students. | Measures acceptance across microevolution, macroevolution, and human evolution subscales. |

The CACIE is a significant development for research with young children, a group for whom few validated tools existed. Its development involved a five-year research process, including a systematic literature review, pilot studies, and observations, ensuring its questions are developmentally appropriate and scientifically valid [21].

The ACORNS instrument is particularly valuable for probing teleological reasoning because of its open-ended format. Unlike multiple-choice tests, it allows researchers to see how individuals spontaneously construct explanations for evolutionary change, revealing a tendency to default to purpose-based arguments even when mechanistic knowledge is available [19].

Experimental Protocols for Instrument Implementation

Standardized administration is crucial for obtaining reliable and comparable data. The following protocols outline best practices for deploying these assessment tools in a research context.

Protocol for Administering Conceptual Inventories

This protocol is adapted from established best practices for concept inventories and research methodologies [22] [19].

- Instrument Selection: Choose an inventory whose measured constructs (e.g., teleological reasoning, natural selection understanding) align with your research questions. Verify the instrument's validation level for your target demographic [22].

- Pre-Test Administration:

- Timing: Administer the pre-test before any relevant instruction or intervention to accurately capture baseline knowledge and pre-existing reasoning biases [22].

- Setting: Conduct in a controlled, quiet environment to minimize distractions.

- Instructions: Provide standardized, neutral instructions to all participants. For example: "This is not a test of your intelligence or a graded exam. We are interested in your ideas about how living things change over time. Please answer each question as best you can."

- Anonymity: Assure participants of confidentiality to reduce anxiety and social desirability bias.

- Intervention Period: Conduct the planned educational intervention or training program.

- Post-Test Administration:

- Timing: Administer the post-test immediately after the intervention concludes. For retention studies, a delayed post-test may be administered weeks or months later.

- Setting and Instructions: Maintain conditions identical to the pre-test.

- Data Collection and Storage: Collect assessments with a participant code to allow for pre-post matching while maintaining anonymity. Store data securely.

Protocol for Coding and Analyzing ACORNS-like Responses

This protocol details the process for quantifying open-ended responses, a key method in teleology research [19].

- Response Collection: Gather written or transcribed verbal responses to evolutionary scenarios (e.g., "Explain how a species of monkey with a short tail might have evolved to have a long tail over many generations").

- Codebook Development: Create a coding rubric based on established research. Key code categories include:

- Mechanistic Reasoning: Responses citing random variation, differential survival, heritability, and non-directed change.

- External Design Teleology: Responses implying an external agent or designer caused the change for a purpose (e.g., "Nature gave it a long tail to...").

- Internal Design Teleology: Responses attributing change to the organism's internal needs or desires (e.g., "The monkeys needed longer tails, so they evolved them").

- Other Misconceptions (e.g., Lamarckian inheritance).

- Coder Training: Train multiple raters on the use of the codebook. Establish inter-rater reliability (IRR) by having all coders score a subset of the same responses and calculating a reliability metric (e.g., Cohen's Kappa). A Kappa of >0.7 is generally considered acceptable. Retrain and clarify the codebook until high IRR is achieved [21].

- Blinded Coding: Coders score all responses without knowledge of the participant's identity or whether it is a pre- or post-test.

- Data Quantification:

- Calculate frequency counts for each code category per participant or per response.

- Compute scores, such as a "Teleological Reasoning Score" (percentage of responses containing teleological elements) or a "Mechanistic Reasoning Score."

- Statistical Analysis: Use appropriate statistical tests (e.g., paired t-tests for pre-post comparisons of continuous scores, ANOVA for comparing multiple groups) to evaluate the impact of the intervention on reasoning patterns.

Graphviz DOT script for the ACORNS Response Coding Workflow:

Diagram 1: ACORNS response coding workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a suite of "research reagents"—both physical and methodological.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Assessing Teleological Reasoning

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Validated Concept Inventory (e.g., CINS, CACIE) | Provides a standardized, psychometrically robust measure of specific concepts, allowing for cross-institutional comparisons [21] [22]. |

| ACORNS Assessment Prompts | A set of open-ended evolutionary scenarios used to elicit spontaneous reasoning and identify teleological explanations without the cueing effect of multiple-choice options [19]. |

| Structured Interview Protocol | A scripted set of questions and prompts (e.g., for the CACIE) ensures consistency across participants and raters, enhancing data reliability [21]. |

| Coding Rubric/Codebook | The operational definitions for different types of reasoning (mechanistic, teleological). It is the key for transforming qualitative responses into quantifiable data [19]. |

| Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR) Metric | A statistical measure (e.g., Cohen's Kappa) that validates the consistency of the coding process, ensuring the data is objective and reproducible [21]. |

| Pre-Post Test Research Design | The foundational methodological framework for measuring change in understanding or reasoning as a result of an intervention [22]. |

Visualization of Conceptual Change and Assessment Strategy

Effective research design involves mapping the pathway from intuitive to scientific reasoning and deploying the right tools to measure progress along that path. The following diagram illustrates this strategic assessment approach.

Graphviz DOT script for the Conceptual Change Assessment Strategy:

Diagram 2: Conceptual change assessment strategy.

Established instrumentation like the ACORNS tool and various conceptual inventories provide the rigorous methodology required to move beyond anecdotal evidence in evolution education and cognition research. By applying the detailed protocols for administration and coding outlined in this document, researchers can generate high-quality, reproducible data on the persistence of teleological reasoning and the efficacy of strategies designed to promote a mechanistic understanding of evolution. This scientific approach to assessment is critical for developing effective training and educational frameworks, ultimately supporting clearer scientific reasoning in fields ranging from basic biology to applied drug development.

Concept mapping is a powerful visual tool used to represent and assess an individual's understanding of complex topics by illustrating the relationships between concepts within a knowledge domain. These maps consist of nodes (concepts) connected by labeled links (relationships), forming a network of propositions that externalize cognitive structures [23]. Within evolution education, where conceptual understanding is often hampered by persistent teleological reasoning (attributing evolution to needs or purposes), concept mapping provides a structured method to make students' conceptual change and knowledge integration processes visible [24] [5]. This protocol details the application of concept mapping as an assessment tool, focusing on the quantitative analysis of network metrics and concept scores to evaluate conceptual development, particularly in the context of identifying and addressing teleological reasoning in evolution research.

Background and Theoretical Framework

The Challenge of Teleological Reasoning in Evolution

Teleological reasoning, the attribution of purpose or directed goals to evolutionary processes, presents a significant hurdle in evolution education [5]. Students often explain evolutionary change by referencing an organism's needs, conflating proximate mechanisms (e.g., physiological or behavioral responses) with ultimate causes (the evolutionary mechanisms of natural selection acting over generations) [5]. Concept maps can help distinguish these causal levels by making the structure of a student's knowledge explicit, thereby revealing gaps, connections, and potentially flawed teleological propositions.

Concept Maps as Models of Knowledge Structure

Concept maps are grounded in theories of cognitive structure and knowledge integration. They externalize the "cognitive maps" individuals use to organize information, allowing researchers to analyze the complexity, connectedness, and accuracy of a learner's conceptual framework [23]. When used repeatedly over a learning period, they can trace conceptual development, showing how new information is assimilated or existing knowledge structures are accommodated [24]. This is crucial for investigating conceptual change regarding evolutionary concepts.

Key Quantitative Metrics for Concept Map Analysis

The analysis of concept maps for assessment relies on quantifiable metrics that serve as proxies for knowledge structure quality. These metrics can be broadly categorized into structural metrics and concept-focused scores. The table below summarizes the core quantitative metrics used in concept map analysis.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Concept Map Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Metrics | Number of Nodes | Total count of distinct concepts included in the map [24] [25]. | Indicates breadth of knowledge or scope considered. |

| Number of Links/Edges | Total count of connecting lines between nodes [24] [25]. | Reflects the degree of interconnectedness between ideas. | |

| Number of Propositions | Valid, meaningful statements formed by a pair of nodes and their linking phrase [25]. | Measures the quantity of articulated knowledge units. | |

| Branching Points | Number of concepts with at least three connections [25]. | Suggests the presence of integrative, hierarchical concepts. | |

| Average Degree | The average number of links per node in the map [24]. | A key network metric indicating overall connectedness. | |

| Concept Scores | Concept Score | Score based on the quality and accuracy of concepts used [24]. | Assesses the sophistication and correctness of individual concepts. |

| Similarity to Expert Maps | Quantitative measure of overlap with a reference map created by an expert [24]. | Gauges the "correctness" or expert-like nature of the knowledge structure. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing concept mapping as an assessment tool in a research or educational setting, with a focus on evolution education.

Protocol 1: Longitudinal Assessment of Conceptual Change in Evolution

Objective: To track changes in students' conceptual understanding of evolutionary factors (e.g., mutation, natural selection, genetic drift) over the course of an instructional unit.

Materials:

- Focus question (e.g., "How does evolution occur in a population?")

- Pre-defined list of key concepts (e.g., mutation, natural selection, adaptation, genetic variation, fitness, population) or allow for open concept use.

- Digital concept mapping software (e.g., Visme, LucidChart, Miro) [23] or physical materials (pen, cards, sticky notes).

- Data collection instrument (e.g., pre- and post-test conceptual inventory) [24].

Procedure:

- Pre-test Assessment: Administer a conceptual inventory (e.g., a multiple-choice test on evolution) to establish a baseline of understanding [24].

- Initial Map Construction (Time T1): Present participants with the focus question. Instruct them to create a concept map using the provided concepts (or their own) to answer the question. Emphasize that nodes should be connected with labeled arrows to form meaningful statements [23] [25].

- Intermediate Map Revisions (Times T2, T3, etc.): At strategic points during the instructional unit, have participants revisit and revise their previous concept maps. This allows them to incorporate new learning, correct misconceptions, and create new connections [24].

- Post-test and Final Map (T_final): After the instructional unit, re-administer the conceptual inventory. Then, have participants create a final, revised concept map [24].

- Data Extraction and Analysis:

- For each map (T1, T2, ..., T_final), calculate the metrics listed in Table 1 (number of nodes, links, propositions, average degree, etc.).

- Calculate a "similarity to expert map" score for each participant's maps.

- Analyze the pre-post change in conceptual inventory scores. Split participants into groups based on learning gains (e.g., high, medium, low) [24].

- Statistically compare the concept map metrics between the different time points and between the different learning-gain groups.

Workflow Visualization:

Protocol 2: Linking Map Structure to Scientific Reasoning in Writing

Objective: To investigate the correlation between the structural complexity of concept maps used to plan scientific writing and the quality of the resulting written scientific reasoning.

Materials:

- Research topic or thesis statement.

- Concept mapping software.

- A validated writing assessment rubric (e.g., the Biology Thesis Assessment Protocol (BioTAP) for evaluating scientific reasoning) [25].

Procedure:

- Map Creation: Participants generate a concept map to define the boundaries of their research and construct their scientific argument, rather than using a traditional outline [25].

- Peer and Instructor Review: Maps are reviewed by peers and instructors. Feedback focuses on clarity, use of jargon, logical connections, and the need for more or less elaboration [25].

- Map Revision: Participants revise their concept maps based on feedback.

- Thesis Writing: Participants write their full scientific thesis or paper.

- Assessment and Correlation:

- The final thesis is assessed using a standardized writing rubric (e.g., BioTAP) to generate a scientific reasoning score [25].

- The structural features of the final concept map (number of concepts, propositions, branching points) are quantified.

- A statistical analysis (e.g., correlation) is performed between the map complexity metrics and the writing assessment scores. It is important to note that increased complexity does not always correlate with improved writing, as experts may simplify their maps to focus on core arguments [25].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Concept Mapping Studies

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Tools & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Mapping Software | Enables efficient creation, editing, and digital analysis of concept maps. Facilitates collaboration and data export. | Visme, LucidChart, Miro, Mural [23]. |

| Social Network Analysis (SNA) Software | Used for advanced quantitative analysis of concept map network structure, calculating metrics like centrality and density [26]. | UCINET, NetDraw [26]. |

| Validated Assessment Rubric | Provides a reliable and consistent method for scoring the quality of written work or specific concepts in a map. | Biology Thesis Assessment Protocol (BioTAP) [25]. |

| Expert Reference Map | A concept map created by a domain expert; serves as a "gold standard" for calculating similarity scores of participant maps [24]. | Should be developed and validated by multiple experts for reliability. |

| Pre-/Post-Test Instrument | A standardized test to measure content knowledge gains independently of the concept map activity. | Conceptual inventories in evolution (e.g., assessing teleological reasoning) [24]. |

Visualization and Analysis of Map Networks

Concept maps can be analyzed as networks, and Social Network Analysis (SNA) methods can be applied to gain deeper insights. SNA can visualize the map from different perspectives and calculate additional metrics on the importance of specific concepts (nodes) within the network [26]. The following diagram illustrates a sample analysis workflow for a single concept map using SNA principles.

Concept Map Network Analysis:

Concept mapping, when coupled with rigorous quantitative analysis of network metrics and concept scores, provides a powerful and versatile methodology for assessing conceptual understanding. In the specific context of evolution education research, it offers a window into the complex processes of knowledge integration and conceptual change, allowing researchers to identify and track the persistence of teleological reasoning. The protocols and metrics outlined here provide a framework for researchers to reliably employ this tool, generating rich, data-driven insights into how students learn and how instruction can be improved to foster a more scientifically accurate understanding of evolution.

Application Notes

Theoretical Foundation and Utility in Research

Rubric-based scoring provides a structured, transparent framework for analyzing complex constructs like teleological reasoning in evolution. By defining specific evaluative criteria and quality levels, rubrics transform subjective judgment into reliable, quantifiable data, enabling precise measurement of conceptual understanding and misconceptions in research populations [27]. This methodology is particularly valuable in evolution education research for disentangling interconnected reasoning elements and providing consistent, replicable scoring across large datasets [14].

In the context of evolutionary biology assessment, analytic rubrics are predominantly used to separately score multiple key concepts and misconceptions [14]. This granular approach allows researchers to identify specific patterns in teleological reasoning—the cognitive tendency to attribute purpose or deliberate design as a causal explanation in nature—rather than treating evolution understanding as a monolithic trait. The structural clarity of rubrics also facilitates the training of human coders and the development of automated scoring systems, enhancing methodological rigor in research settings [27] [14].

Key Concepts and Misconceptions in Evolutionary Reasoning

Research utilizing rubric-based approaches has identified consistent patterns in evolutionary reasoning across diverse populations. The table below summarizes core concepts and prevalent teleological misconceptions frequently assessed in evolution education research:

Table 1: Key Concepts and Teleological Misconceptions in Evolutionary Reasoning

| Category | Component | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Key Scientific Concepts | Variation | Presence of heritable trait differences within populations [14] |

| Heritability | Understanding that traits are passed from parents to offspring [14] | |

| Differential Survival/Reproduction | Recognition that traits affect survival and reproductive success [14] | |

| Limited Resources | Understanding that resources necessary for survival are limited [28] | |

| Competition | Recognition that organisms compete for limited resources [14] | |

| Non-Adaptive Factors | Understanding that not all traits are adaptive [14] | |

| Teleological Misconceptions | Need-Based Causation | Belief that traits evolve because organisms "need" them [14] |

| Adaptation as Acclimation | Confusion between evolutionary adaptation and individual acclimation [14] | |

| Use/Disuse Inheritance | Belief that traits acquired during lifetime are heritable [14] |

Teleological misconceptions, particularly need-based causation, represent deeply embedded cognitive patterns that persist despite formal instruction [14] [28]. Rubric-based scoring allows researchers to quantify the prevalence and persistence of these non-normative ideas across different educational interventions, demographic groups, and cultural contexts, providing critical data for developing targeted pedagogical strategies.

Quantitative Performance of Scoring Methodologies

Recent comparative studies have quantified the performance of different scoring methodologies when applied to evolutionary explanations. The following table summarizes reliability metrics and characteristics of human, machine learning (ML), and large language model (LLM) scoring approaches:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Scoring Methods for Evolutionary Explanations

| Scoring Method | Agreement/Reliability | Processing Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Scoring with Rubric | Cohen's Kappa > 0.81 [14] | High labor time | High accuracy, nuanced judgment | Time-consuming, expensive at scale |

| Traditional ML (EvoGrader) | Matches human reliability [14] | Rapid processing | High accuracy, replicability, privacy | Requires large training dataset |

| LLM Scoring (GPT-4o) | Robust but less accurate than ML (~500 additional errors) [14] | Rapid processing | No task-specific training needed | Ethical concerns, reliability issues |

The ACORNS (Assessment of COntextual Reasoning about Natural Selection) instrument, coupled with its analytic rubric, has demonstrated strong validity evidence across multiple studies and international contexts, including content validity, substantive validity, and generalization validity [14]. When implemented with rigorous training and deliberation protocols, human scoring with this rubric achieves inter-rater reliability levels (Cohen's Kappa > 0.81) considered almost perfect agreement in research contexts [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementation of Rubric-Based Human Scoring

Research Instruments and Data Collection

- Instrument Selection: Utilize the established ACORNS instrument (Assessment of COntextual Reasoning about Natural Selection) to elicit written explanations of evolutionary change [14]. This instrument presents biological scenarios across diverse taxa and evolutionary contexts to surface both normative and non-normative reasoning patterns.

- Data Collection: Administer ACORNS items to research participants in controlled settings. Ensure responses are text-based and of sufficient length to exhibit reasoning patterns (typically 1-5 sentences). Collect demographic data and potential covariates (e.g., prior evolution education, religious affiliation, political orientation) to enable analysis of subgroup differences [29].

Rater Training and Calibration

- Training Phase: Provide raters with the analytic scoring rubric containing definitions of all nine concepts (six normative, three misconceptions) [14]. Conduct group sessions using sample responses not included in the research corpus. Discuss scoring decisions until consensus is achieved.

- Calibration Phase: Independently score a calibration set of 50-100 responses. Calculate inter-rater reliability using Cohen's Kappa for each concept. Require minimum reliability of κ = 0.75 before proceeding to research scoring. Retrain on problematic concepts if needed.

- Ongoing Quality Control: Implement periodic checks during research scoring by having all raters score the same randomly selected responses. Investigate and resolve systematic scoring discrepancies through deliberation.

Scoring Procedure and Data Management

- Blinded Scoring: Ensure raters are blinded to participant demographics and experimental conditions when scoring responses.

- Consensus Building: For responses where initial independent scores disagree, implement a structured deliberation process where raters present evidence from the text to support their scoring decisions [14].

- Data Recording: Record binary scores (present/absent) for each of the nine concepts in a structured database. Maintain records of initial disagreements and consensus decisions for transparency and reliability assessment.

Protocol 2: Automated Scoring Validation and Implementation

ML-Based Scoring with EvoGrader

- System Preparation: Access the web-based EvoGrader system (www.evograder.org). The system utilizes "bag of words" text parsing and binary classifiers from Sequential Minimal Optimization, with each concept model optimized by unique feature extraction combinations [14].

- Model Validation: Before scoring research data, validate system performance on a subset of human-scored responses from your specific population. Compute agreement statistics to ensure performance matches established benchmarks.

- Batch Processing: Upload text responses in appropriate format. The system automatically processes responses and returns scores for all nine concepts. Download results for statistical analysis.

LLM Scoring Implementation

- Prompt Engineering: Develop specific prompts that incorporate the rubric criteria for each concept. Example prompt structure: "Identify whether the following student explanation contains evidence of [specific concept]. Response: [student text]. Options: Present, Absent. Guidelines: [concept definition and examples]." [14]

- LLM Configuration: Use consistent parameters across scoring runs (temperature = 0 for deterministic output, appropriate token limits). For proprietary LLMs like GPT-4o, implement API calls with error handling and rate limiting.

- Validation Sampling: Manually verify a statistically significant sample of LLM-scored responses (≥10%) against human scoring to quantify agreement and identify systematic errors.

Protocol 3: Analysis of Teleological Reasoning Patterns

Quantitative Analysis of Scoring Data

- Concept Frequency Calculation: Compute prevalence rates for each key concept and misconception across the sample. Calculate 95% confidence intervals for proportion estimates.

- Concept Co-occurrence Analysis: Use association mining or network analysis to identify patterns in how concepts cluster within responses. Teleological misconceptions (particularly need-based reasoning) often co-occur with absence of key mechanistic concepts [14].

- Statistical Modeling: Employ multivariate regression models to identify demographic and educational factors associated with teleological reasoning patterns. Control for relevant covariates in models examining subgroup differences [29].

Qualitative Analysis of Response Patterns

- Response Profiling: Develop typologies of teleological reasoning based on response patterns. Common patterns include: explicit need statements ("needed to..."), intentionality language ("wanted to..."), and goal-oriented explanations ("in order to...") [14].

- Contextual Analysis: Examine how problem features (taxon, trait type, evolutionary context) influence expression of teleological reasoning. Certain contexts may preferentially activate teleological schemas [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACORNS Instrument | Assessment tool | Elicits evolutionary explanations across diverse contexts | Multiple parallel forms; various biological scenarios [14] |

| Analytic Scoring Rubric | Measurement framework | Provides criteria for scoring key concepts and misconceptions | Binary scoring (present/absent); 9 defined concepts [14] |

| EvoGrader | Automated scoring system | Machine learning-based analysis of written responses | Free web-based system; trained on 10,000+ responses [14] |

| Cohen's Kappa Statistic | Reliability metric | Quantifies inter-rater agreement beyond chance | Accounts for agreement by chance; standard in rubric validation [27] [14] |

| Rater Training Protocol | Methodology | Standardizes human scoring procedures | Includes calibration exercises; consensus building [14] |

Teleological reasoning, the cognitive bias to view natural phenomena as occurring for a purpose or directed toward a goal, represents a significant barrier to accurate understanding of evolutionary mechanisms [10]. This cognitive framework leads individuals to explain evolutionary change through statements such as "giraffes developed long necks in order to reach high leaves," implicitly attributing agency, intention, or purpose to natural selection [10]. In research settings, systematically identifying and quantifying this reasoning pattern in written explanations provides crucial data for developing effective educational interventions and assessment tools. This protocol establishes standardized methods for extracting evidence of teleological reasoning from textual data, enabling consistent analysis across evolutionary biology education research.

Coding Framework: Operational Definitions and Classification

Core Definition and Key Characteristics

For coding purposes, teleological reasoning is operationally defined as: The attribution of purpose, goal-directedness, or intentionality to evolutionary processes to explain the origin of traits or species. This contrasts with scientifically accurate explanations that reference random variation and differential survival/reproduction without implicit goals [10].

The table below outlines the primary indicators of teleological reasoning in written text:

Table 1: Coding Indicators for Teleological Reasoning

| Indicator Category | Manifestation in Text | Example Statements |

|---|---|---|

| Goal-Oriented Language | Use of "in order to," "so that," "for the purpose of" connecting traits to advantages | "The polar bear grew thick fur in order to stay warm in the Arctic." |

| Need-Based Explanation | Organisms change because they "need" or "require" traits to survive | "The giraffe needed a long neck to reach food." [10] |

| Benefit-as-Cause Conflation | Confusing the benefit of a trait with the cause of its prevalence | "The moths turned dark to camouflage themselves from predators." |

| Intentionality Attribution | Attributing conscious intent to organisms or species | "The finches wanted bigger beaks, so they exercised them." [10] |

Distinguishing from Other Cognitive Biases

Accurate coding requires distinguishing teleological reasoning from other common cognitive biases in evolution understanding:

- Essentialism: The assumption that species members share an unchanging essence [21]

- Anthropomorphism: Attributing human characteristics to non-human organisms or processes [21]

- Lamarckian Inheritance: Belief that acquired characteristics can be directly inherited

Quantitative Analysis and Data Presentation

Scoring and Frequency Quantification

Once coded, teleological reasoning instances should be quantified using standardized metrics. The following table presents core quantitative measures for analysis:

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Teleological Reasoning Analysis

| Metric | Operational Definition | Calculation Method | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teleological Statement Frequency | Raw count of statements exhibiting teleological reasoning | Direct count per response/text | 5 teleological statements in one written explanation |

| Teleological Density Score | Proportion of teleological statements to total statements | (Teleological Statements / Total Statements) × 100 | 4 teleological statements out of 10 total = 40% density |

| Teleological Category Distribution | Frequency distribution across teleological subtypes | Counts per subcategory (goal-oriented, need-based, etc.) | 60% need-based, 30% goal-oriented, 10% intentionality |

| Pre-Post Intervention Change | Reduction in teleological reasoning after educational intervention | (Pre-density - Post-density) / Pre-density | Density reduction from 45% to 20% = 55.6% improvement |

Statistical Analysis Protocols

For rigorous analysis, implement these statistical procedures:

- Inter-rater Reliability Assessment: Calculate Cohen's kappa (κ) or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to establish coding consistency between multiple raters

- Comparative Analysis: Use t-tests or ANOVA to compare teleological reasoning metrics between different participant groups (e.g., educational background, prior coursework)

- Intervention Effectiveness: Employ paired t-tests to assess significant reductions in teleological reasoning following educational interventions

- Correlational Analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson's r) between teleological reasoning scores and other variables (e.g., evolution acceptance, religiosity)

Experimental Protocol: Data Collection and Processing Workflow

Instrument Selection and Administration

Figure 1: Workflow for selecting appropriate assessment instruments and collecting written explanations for teleological reasoning analysis.

Procedure:

- Select appropriate assessment instrument based on target population:

- Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS): For undergraduate or adult populations [10]

- Conceptual Assessment of Children's Ideas about Evolution (CACIE): For elementary-aged children (interview-based) [21]

- Open-Ended Evolutionary Scenarios: Researcher-developed prompts asking participants to explain evolutionary change in specific contexts

Administer instrument following standardized protocols:

- Provide consistent instructions to all participants

- Ensure adequate time for written responses (typically 15-45 minutes depending on instrument)

- Collect demographic data (age, prior biology education, evolution acceptance measures)

Prepare data for analysis:

- Anonymize all responses

- Transcribe handwritten responses to digital text format

- Organize responses in structured database with unique identifiers

Coding and Analysis Procedure

Figure 2: Systematic workflow for coding and analyzing teleological reasoning in written texts.

Coder Training Protocol:

- Training Session (2 hours):

- Review operational definitions of teleological reasoning and related concepts

- Practice coding sample texts with known teleological reasoning instances

- Discuss coding disagreements to establish consensus understanding

- Reliability Assessment:

- Each coder independently analyzes identical set of 20-30 participant responses

- Calculate inter-rater reliability using Cohen's kappa (κ)

- Require minimum κ ≥ 0.80 before proceeding with full analysis