Molecular Dynamics for Protein Structure Refinement: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation as a powerful tool for refining predicted and experimental protein structures.

Molecular Dynamics for Protein Structure Refinement: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation as a powerful tool for refining predicted and experimental protein structures. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details how physics-based MD sampling, when integrated with knowledge-based data and smart restraints, can consistently improve model accuracy towards experimental levels. The content explores key methodologies, addresses common challenges like force field selection and sampling limitations, and outlines rigorous validation protocols against experimental observables. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices, demonstrating MD's growing role in bridging the sequence-structure gap for drug discovery, functional analysis, and next-generation risk assessment.

The Physics-Based Foundation of MD for Structure Refinement

The paradigm that a protein's amino acid sequence determines its three-dimensional structure is a cornerstone of structural biology [1]. The remarkable success of artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) tools such as AlphaFold2 in predicting static protein structures from sequence has validated this principle [1] [2]. However, a significant gap remains between predicting a single, static structure and understanding the dynamic conformational ensembles that are essential for protein function [1]. This application note details the limitations of current static structure predictions and provides detailed protocols for using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to refine these models, thereby bridging the sequence-structure gap towards a more complete understanding of protein dynamics.

The AI/ML Revolution and Its Limitations

AI/ML tools like AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, and ESMFold employ specialized neural network architectures and attention mechanisms to achieve unprecedented accuracy in protein structure prediction [1]. These models are trained on vast datasets of sequence and structural information from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and genomic databases [1]. Benchmark tests demonstrate that advanced hybrid methods like D-I-TASSER can outperform AlphaFold2 on certain targets, particularly difficult single-domain and multidomain proteins, with average TM-scores of 0.870 versus 0.829 on a set of 500 non-redundant hard targets [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Structure Prediction Methods on "Hard" Targets

| Method | Average TM-score | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-I-TASSER | 0.870 [2] | Hybrid approach; integrates deep learning potentials with physics-based folding simulations; domain splitting & assembly [2] | Computationally intensive |

| AlphaFold2.3 | 0.829 [2] | End-to-end deep learning; attention mechanisms; multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) [1] [2] | Primarily predicts static structures |

| C-I-TASSER | 0.569 [2] | Uses deep-learning-predicted contact restraints [2] | Lower accuracy than newer hybrid methods |

| I-TASSER | 0.419 [2] | Traditional threading assembly refinement; physics-based force field [2] | Relies heavily on template identification |

Despite their success, these AI/ML models typically predict a single, low-energy state, potentially overlooking the structural heterogeneity critical for function [1]. Proteins are dynamic systems that sample multiple conformational states across complex energy landscapes [1]. Techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy reveal ensembles of conformational states, underscoring the need for refinement beyond static prediction [1].

Molecular Dynamics for Structure Refinement

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful methodology for refining static structural models by simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. MD allows researchers to probe the effects of mutations, investigate intermolecular interactions, and explore conformational dynamics [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for MD-Based Refinement

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| drMD Pipeline | An automated, user-friendly pipeline for running MD simulations using the OpenMM toolkit [3] | Reduces expertise barrier for non-specialists to run publication-quality simulations [3] |

| OPLS4 Forcefield | A classical molecular mechanics force field parameterized to accurately predict properties like density and heat of vaporization [4] | Provides physical parameters for energy calculations in MD simulations [4] |

| NMR Ensemble Data | Experimentally determined ensembles of conformational states from the PDB and BMRB [1] | Serves as ground truth for training AI/ML models and validating predicted conformational ensembles [1] |

| High-Throughput MD Dataset | Large-scale simulation datasets (e.g., 30,000+ solvent mixtures) for benchmarking formulation-property relationships [4] | Enables benchmarking of machine learning models and provides physical insights into multicomponent systems [4] |

Protocol: MD Simulation for AI-Predicted Model Refinement

Objective: To refine a static AI-predicted protein structure and explore its conformational landscape using the drMD pipeline. Input: A protein structure file (e.g., PDB format) from AlphaFold2 or similar prediction tools.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Setup

- Solvation: Place the protein model in a solvation box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with a minimum padding of 1.0 nm between the protein and the box edge.

- Neutralization: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge. Additional ions can be added to simulate physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Energy Minimization

- Run an energy minimization step using the steepest descent algorithm to remove steric clashes and high-energy interactions introduced during system setup.

- Termination Criteria: Continue until the maximum force is less than 1000 kJ/mol/nm.

Equilibration

- Perform a two-phase equilibration in the NVT and NPT ensembles.

- NVT Ensemble: Run for 100 ps while restraining protein heavy atoms, gradually heating the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- NPT Ensemble: Run for 100 ps with restrained protein heavy atoms to stabilize the system pressure (e.g., 1 bar).

Production Simulation

- Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a duration sufficient to capture the dynamics of interest (typically 100 ns to 1 µs, depending on the system and research question).

- Configuration: Use a 2-fs time step. Save atomic coordinates to a trajectory file every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis.

Analysis

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Analyze the protein backbone RMSD relative to the starting structure to assess stability and convergence.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Calculate per-residue RMSF to identify flexible regions.

- Cluster Analysis: Perform clustering on the trajectory to identify dominant conformational states.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Use PCA to identify the major collective motions of the protein.

Integrating MD with AI for Conformational Ensemble Prediction

A promising frontier is the development of AI/ML models dedicated to predicting protein conformational ensembles directly from sequence [1]. This can be achieved by training models that integrate sequence data with conformationally sensitive experimental data, such as NMR-derived structural ensembles [1]. The following workflow outlines a conceptual framework for this integration.

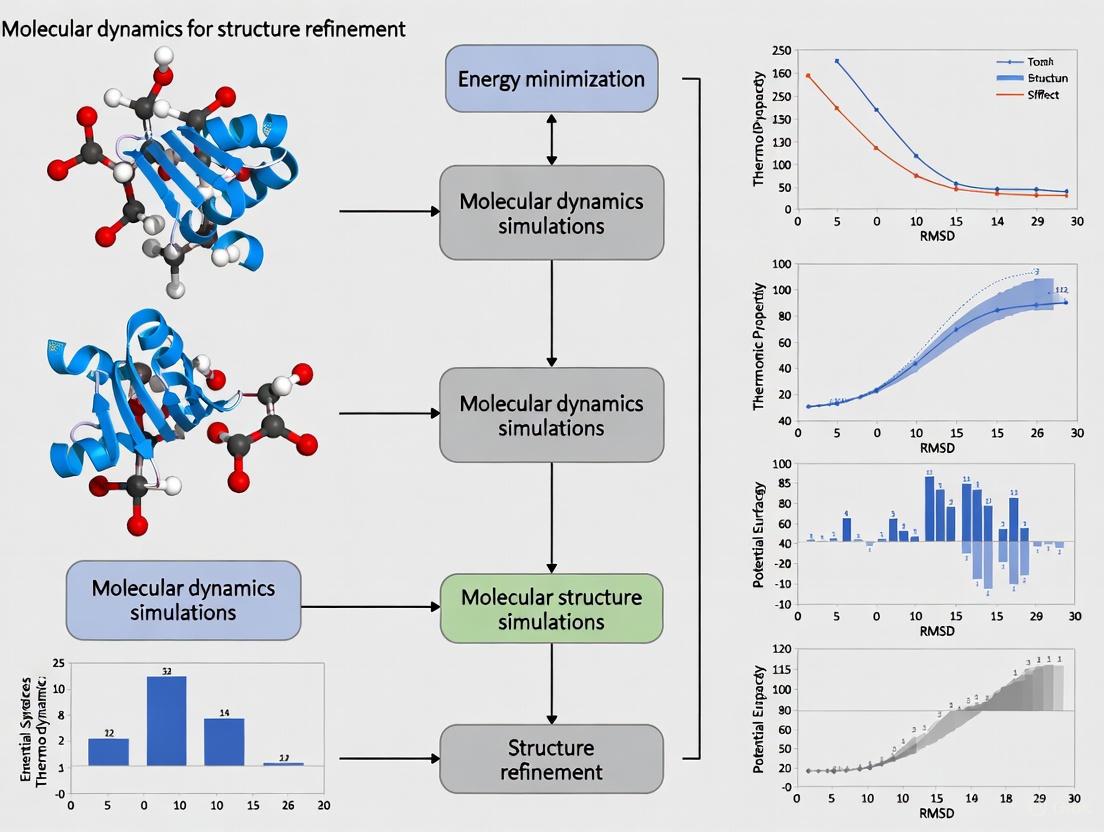

Diagram 1: Workflow for Ensemble Prediction.

While AI has dramatically advanced our ability to predict protein structure from sequence, molecular dynamics simulations remain an indispensable tool for refining these models and capturing the dynamic nature of proteins. The integration of AI-predicted structures with physics-based simulations and experimental data offers a powerful pathway to finally bridge the sequence-structure gap, enabling a deeper understanding of protein function and accelerating drug discovery.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational microscope, enabling researchers to bridge the gap between static template-based models and the dynamic physical reality of biomolecular systems. While experimental techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provide invaluable structural information, they often produce ensemble-averaged data that may misrepresent the inherent flexibility of biological macromolecules. This application note details how MD simulations, particularly advanced ensemble refinement methods, can transform static structural models into dynamic ensembles that better reflect biological reality. We focus specifically on protocols for refining mismodeled RNA structures, with broader applications for proteins and other macromolecular complexes frequently encountered by drug development professionals. The integration of MD with experimental data creates a powerful pipeline for converting structural biology data into mechanistically relevant models that can inform drug discovery efforts.

Quantitative Analysis of the Single-Structure Problem in Cryo-EM

Single-particle cryo-EM has revolutionized structural biology by enabling near-atomic resolution imaging of large macromolecular complexes, but conventional refinement tools condense all single-particle images into a single structure, which can significantly misrepresent highly flexible molecules. This limitation is particularly problematic for RNA-containing structures and flexible protein regions where conformational heterogeneity exists. Recent analysis reveals that this issue affects most cryo-EM RNA structures in the 2.5-4 Å resolution range, necessitating computational refinement approaches [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Mismodeling in RNA Cryo-EM Structures

| Parameter | Pre-MD Refinement | Post-MD Ensemble Refinement | Improvement Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Properly folded helices | 6 mismodeled helices | All helices correctly paired | 100% recovery of canonical structure |

| Conformational coverage | Single static conformation | Multiple conformational states | Dynamic ensemble representing system plasticity |

| Experimental data fit | Incompatible for flexible regions | Bayesian agreement with density | Statistically rigorous uncertainty quantification |

| B-factor representation | Isotropic approximations | Explicit spatial fluctuations | Physically meaningful dynamics mapping |

The fundamental challenge arises because cryo-EM density maps often result from a mixture of conformational states, particularly for disordered regions, multi-domain proteins, and RNA systems. Fitting such heterogeneous data with a single structure frequently leads to non-biologically relevant models or structural artifacts where the model sacrifices proper geometric parameters (like canonical base pairing in RNA helices) to fit the experimental density [5].

Ensemble Refinement Protocol for Cryo-EM Structures

System Preparation and Initial Modeling

Begin with the deposited cryo-EM structure (PDB format) and corresponding density map (EMD format). For the group II intron ribozyme protocol (PDB: 6ME0, EMD-9105, resolution 3.6 Å), first visually inspect the structure and identify regions with poor geometry or unclear density [5]:

- Identify missing residues: For 6ME0, a 38-nucleotide gap was present and modeled using DeepFoldRNA. Include this modeled region in simulations but note it for separate analysis if the density map is truncated in this area.

- Detect mismodeled elements: Use annotation tools and secondary structure prediction to identify elements inconsistent with canonical geometry. For 6ME0, six helices were not properly paired despite being present in the reference secondary structure.

- Initial helix remodeling: Execute short (2.5 ns) MD simulations in explicit solvent with restraints to remodel mismodeled helices using canonical template RNA duplexes with identical sequences. Apply the ERMSD metric, which accounts for properly paired strands and has been used to reversibly fold RNA motifs.

Metainference Ensemble Refinement

The core refinement employs metainference, a Bayesian method that reconstructs structural ensembles using multi-replica MD simulations guided by experimental data [5]:

- Simulation initialization: Start from the final structure of the restrained MD simulation with properly folded helices.

- Single-replica control: Perform initial single-replica refinement enforcing one model to match experimental data as a control. This typically causes properly folded helices to unfold, confirming incompatibility with the single-structure assumption.

- Multi-replica ensemble setup: Initialize ensemble refinement with increasing replicas (8, 16, 32, 64), taking equally spaced snapshots from the single-structure refinement simulation. A minimum of 8 replicas is typically required to satisfy experimental restraints.

- Production simulation: Run 10 ns trajectory per replica. Release helical restraints after first 5 ns, allowing incompatible helices to unfold while maintaining biologically relevant ones.

- Validation controls: Repeat simulation with different force fields and ion conditions (e.g., K+ vs Na+) to confirm robustness.

Workflow Title: MD Ensemble Refinement Protocol

Convergence and Quality Assessment

Robust MD simulations require careful convergence analysis to ensure reliable results. Follow this reproducibility checklist [6]:

- Convergence validation: Demonstrate time-course analysis showing property equilibration. Clearly describe how simulations are split into equilibration and production runs, specifying the amount of production data analyzed.

- Statistical robustness: Perform at least 3 independent simulations per condition with statistical analysis. Provide evidence that results are independent of initial configuration.

- Experimental connection: Calculate experimental observables where possible (mutagenesis effects, binding assays, NMR parameters, FRET distances) to validate physiological relevance.

- Force field justification: Describe whether chosen model accuracy is sufficient for the research question (all-atom vs. coarse-grained, fixed charge vs. polarizable, solvent model). Justify force field selection based on system characteristics.

- Enhanced sampling needs: If investigating events beyond brute-force MD timescales, employ enhanced sampling methods with clearly stated parameters and convergence criteria.

- Complete documentation: Provide system setup details including box dimensions, atom counts, water molecules, ion concentration, temperature, pressure control methods, and software versions with input files in public repositories.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for MD Refinement

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Parameters | Function in Refinement Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | FF12MC, FF14SB, FF99 with modifications [7] | Describe physical interactions and energy relationships between atoms |

| Specialized Force Field Features | Shortened C-H bonds, removed nonperipheral sp3 torsions, reduced 1-4 interaction scaling factors [7] | Improve simulation stability and agreement with experimental data |

| Simulation Software | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD | MD simulation engines with explicit solvent capabilities |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Metainference, replica-exchange MD | Overcome energy barriers and improve conformational sampling |

| Experimental Data Integration | Cryo-EM density map restraints (EMD-9105) [5] | Guide simulations to match experimental observations |

| System Preparation Tools | DeepFoldRNA for gap modeling [5] | Complete incomplete structural models before refinement |

| Validation Metrics | ERMSD for RNA folding, time-course analysis, B-factor comparison [5] | Quantify refinement improvement and convergence |

| Reproducibility Framework | Molecular dynamics reproducibility checklist [6] | Ensure simulation reliability and methodological rigor |

Visualization and Analysis of Refined Ensembles

Following ensemble refinement, analyze trajectories to extract biological insights and validate against experimental data:

- Representative structure extraction: Cluster trajectories to identify major conformational states. For the group II intron, the most flexible region was the ab initio modeled loop, with significant dynamics also in other regions consistent with B-factor predictions [5].

- Density back-calculation: Generate theoretical density maps from ensemble trajectories to validate against original cryo-EM data.

- Fluctuation analysis: Calculate root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) to quantify regional flexibility and compare with experimental B-factors.

- Functional correlation: Map flexible and rigid regions to phylogenetic conservation data. For the group II intron, flexible regions were typically exterior, solvent-exposed stem loops with low conservation, while rigid core catalytic domains were highly conserved [5].

The ensemble refinement reveals inherent biomolecular plasticity that single-structure approaches obscure. This dynamic view provides deeper functional insights, as flexible regions often play crucial roles in biological mechanisms despite their disorder.

MD-driven ensemble refinement represents a paradigm shift in structural biology, moving from single static models to dynamic ensembles that better capture biological reality. The metainference approach detailed here successfully addressed mismodeling in RNA cryo-EM structures, demonstrating broad applicability to other biomolecular systems. By implementing these protocols, researchers can transform template-based models into physically realistic ensembles, providing drug development professionals with more accurate structural information for rational design. The integration of MD simulations with experimental structural biology creates a powerful framework for understanding biomolecular function at atomic resolution, bridging the critical gap between structural snapshots and biological mechanism.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is an indispensable computational technique for studying the physical motions of atoms and molecules over time, providing atomic-level insights into biological processes and material properties. For researchers engaged in molecular structure refinement, the accuracy and efficiency of an MD simulation are dictated by three core components: the force field, which defines the potential energy surface; the water model, which represents the solvent environment; and the sampling method, which determines the exploration of conformational space. The careful selection and integration of these components are critical for obtaining physically meaningful results that can complement experimental findings. This application note details current methodologies, provides benchmark data, and outlines practical protocols to guide the setup of robust MD simulations within the context of structural refinement research, particularly for drug development applications.

Force Fields

The force field is the fundamental law of an MD simulation, comprising a set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. Its accuracy is paramount for the predictive power of the simulation.

Performance Benchmarking and Selection

Force fields are typically parameterized against specific types of data, and their performance can vary significantly depending on the system and property of interest. A comparative study assessed the accuracy of several major force fields in reproducing experimental vapor-liquid coexistence curves and liquid densities for small organic molecules, with key results summarized in Table 1 [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Performance for Liquid Densities and Vapor-Liquid Coexistence [8]

| Force Field | Primary Parameterization Target | Performance on Liquid Densities | Performance on Vapor Densities | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TraPPE | Vapor-liquid coexistence curves | Best overall accuracy | Good | Specialized for fluid phase equilibria. |

| CHARMM22 | Proteins and nucleic acids | Nearly as accurate as TraPPE | Good | Suitable for biomolecular systems. |

| AMBER-96 | Proteins | Moderate accuracy | Best overall accuracy | - |

| OPLS-aa | Liquid densities for organic molecules | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy | - |

| GROMOS 43A1 | Biomolecular simulations | Lower accuracy | Lower accuracy | - |

| COMPASS | Condensed-phase materials | Lower accuracy | Lower accuracy | - |

| UFF | Broad coverage of periodic table | Poorest accuracy | Poorest accuracy | Not recommended for fluid properties. |

For biomolecular simulations, the choice is often between families like AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS. A 2023 study highlighting the importance of specific extensions for non-natural peptides found that a modified CHARMM36m force field, with improved backbone dihedral parameters, accurately reproduced experimental structures for all seven β-peptide sequences tested [9]. In contrast, the AMBER and GROMOS force fields could only correctly treat four of the seven sequences without further parametrization [9]. This underscores that for novel systems beyond natural proteins, checking for force field parametrization and validation for specific molecule classes is essential.

The Emergence of Neural Network Potentials

A paradigm shift is underway with the development of Neural Network Potentials, which learn potential energy surfaces from high-quality quantum chemical data. Meta's Open Molecules 2025 dataset and associated models, such as the Universal Model for Atoms, demonstrate performance that matches high-accuracy Density Functional Theory on molecular energy benchmarks at a fraction of the computational cost [10]. These models offer a promising path to closing the accuracy gap associated with classical force fields, particularly for reactive systems and those with complex electronic structure.

Water Models

Water models are a critical subset of the force field that define the representation of solvent molecules. The choice of water model significantly influences the simulated properties of solvated molecules, especially for highly charged systems like glycosaminoglycans [11].

Explicit Solvent Model Benchmarking

Explicit solvent models represent water molecules as discrete entities. A 2023 benchmark study evaluated several explicit water models for simulating heparin (HP), a highly anionic glycosaminoglycan, with results summarized in Table 2 [11]. The study highlighted that properties such as the end-to-end distance and radius of gyration are sensitive to the solvent model choice.

Table 2: Comparison of Explicit Water Models for Heparin MD Simulations [11]

| Water Model | Type | Key Findings for Heparin Dynamics | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIP3P | 3-site | Common default; provides a reasonable baseline. | Low |

| SPC/E | 3-site | - | Low |

| TIP4P | 4-site | - | Medium |

| TIP4PEw | 4-site | Improved parameterization for liquid water. | Medium |

| OPC | 4-site | Shows promise for accurate GAG simulation. | Medium |

| TIP5P | 5-site | - | High |

An information-theoretic analysis of water clusters provides further insights into the fundamental differences between models. The study found that the SPC/ε model, which includes an empirical self-polarization correction to improve the dielectric constant, demonstrated superior electronic structure representation and an optimal entropy-information balance compared to TIP3P and SPC [12]. TIP3P showed excessive localization and reduced complexity, which worsened with increasing cluster size [12].

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvent models (e.g., Generalized Born models) treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium rather than explicit molecules. While computationally faster, a benchmark showed they can yield significantly different molecular volumes and dimensions for heparin compared to explicit models [11]. They are generally less reliable for simulating detailed solvation dynamics and specific water-mediated interactions but can be useful for initial folding studies or very large systems where computational cost is prohibitive.

Sampling Methods

Adequate sampling of the conformational ensemble is a major challenge in MD, as biological processes often occur on timescales much longer than can be simulated. Enhanced sampling methods are therefore often necessary.

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics

Replica Exchange MD is a widely used enhanced sampling technique. In REMD, multiple non-interacting copies of the system are simulated in parallel at different temperatures or with different Hamiltonians [13]. Periodically, exchanges between neighboring replicas are attempted based on a Metropolis criterion, which allows conformations to escape deep energy minima [13]. The workflow for setting up a REMD simulation is outlined in Figure 1 and the protocol in Section 7.1.

Advanced and Specialized Sampling Protocols

Beyond standard REMD, new methods continue to be developed. Replica Exchange Solute Tempering is a variant that scales the interactions of a specific "solute" region across replicas, improving sampling efficiency for a region of interest [14]. A novel protocol called Probabilistic MD Chain Growth (PMD-CG) has been introduced for rapidly generating conformational ensembles of disordered proteins. PMD-CG combines structural fragments from a pre-computed tripeptide database with chain growth algorithms, allowing for the extremely quick generation of ensembles that agree well with those generated by more computationally intensive methods like REST [14]. The protocol for PMD-CG is detailed in Section 7.2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key software, force fields, and datasets essential for conducting modern MD simulations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | Engine for running MD simulations. | GROMACS [13], AMBER [13], CHARMM [13], NAMD [13] |

| Visualization Software | Molecular modeling and trajectory analysis. | VMD [13], PyMOL [9] |

| High-Performance Computing | Resource for running compute-intensive simulations. | HPC cluster with MPI [13] |

| Neural Network Potentials | High-accuracy, fast potential energy surfaces. | Meta eSEN and UMA models [10] |

| Reference Datasets | Training and benchmarking for new models. | Meta OMol25 dataset [10] |

| Force Fields (Biomolecules) | Parameters for proteins, nucleic acids, etc. | CHARMM36m [9], AMBER [9], GROMOS [9] |

| Water Models (Explicit) | Representing solvent molecules. | TIP3P [11], SPC/ε [12], OPC [11], TIP4Pew [11] |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Methods to improve conformational sampling. | REMD [13], REST [14], PMD-CG [14] |

The refinement of molecular structures through MD simulation requires careful consideration of its core components. The selection of a force field must be guided by the specific system, with traditional biomolecular force fields like CHARMM36m offering robust performance for proteins, while emerging Neural Network Potentials trained on datasets like OMol25 promise a new level of accuracy. For solvation, explicit water models such as SPC/ε and OPC show advantages over the traditional TIP3P model, particularly for charged biomolecules. Finally, sufficient sampling is non-negotiable, and enhanced methods like REMD, REST, and the novel PMD-CG protocol are essential tools for exploring complex free energy landscapes. By making informed choices among these components, researchers can design MD simulations that provide reliable and insightful data for structure-based research and drug development.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Replica Exchange MD (REMD) with GROMACS

This protocol outlines the steps to perform a REMD simulation using GROMACS for a peptide system, such as studying the dimerization of hIAPP(11-25) [13].

System Preparation: a. Construct the initial configuration of the peptide(s) using a tool like VMD [13]. b. Generate the molecular topology file using

pdb2gmxin GROMACS, selecting the desired force field and water model. c. Solvate the peptide in an appropriate periodic box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) with a minimum distance between the solute and box edge (e.g., 1.0-1.4 nm). d. Add ions to neutralize the system and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).Energy Minimization: a. Perform energy minimization first with position restraints on the solute heavy atoms to relax the solvent and ions. Use the steepest descent algorithm for 1,000-5,000 steps. b. Perform a second minimization without any restraints to remove all residual steric clashes.

System Equilibration: a. NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 100 ps in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) at 300 K. Use a thermostat like the Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover. Maintain position restraints on solute heavy atoms. b. NPT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 50-100 ps in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) at 1 bar. Use a barostat like Parrinello-Rahman. Maintain position restraints on solute heavy atoms.

REMD Setup: a. Determine Replica Parameters: Choose a temperature range (e.g., 300 K to 500 K) and the number of replicas. The number of replicas required for a sufficient acceptance ratio can be estimated using tools like

demux. Typically, 24-64 replicas are used for a small peptide in water. b. Generate Configuration Files: Create a separate.mdpparameter file for each replica, differing only in theref_t(reference temperature) parameter. c. Prepare Topology and Structure: Use themdpfiles withgromppto generate.tprfiles for each replica.Production REMD: a. Launch the multi-replica simulation using

mpirun -np <number_of_replicas> gmx_mpi mdrun -s topol.tpr -multi <number_of_replicas> -replex 500(where-replexdefines the number of steps between exchange attempts). b. Ensure the HPC cluster has sufficient resources (typically 2 cores per replica).Trajectory Analysis: a. After the simulation, use the

demuxtool to recombine the trajectories from different replicas into continuous trajectories at each temperature of interest. b. Analyze the reconstructed trajectories at the temperature of interest (e.g., 300 K) using standard GROMACS tools (g_rms,g_gyrate, etc.) and custom scripts to calculate properties like the free energy landscape.

Protocol: Probabilistic MD Chain Growth for Disordered Proteins

This protocol describes the generation of conformational ensembles for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDRs) using the PMD-CG method [14].

Conformational Pool Generation: a. For all possible tripeptide sequences found in the IDR of interest, run extensive MD simulations (or access pre-computed databases) to sample their conformational space. b. Cluster the trajectories for each tripeptide to create a representative conformational pool, storing structures and their associated statistical weights.

Chain Assembly: a. Start from the N-terminus of the IDR sequence. Select a starting tripeptide fragment from its corresponding conformational pool, weighted by its probability. b. For the next residue in the sequence, select a tripeptide fragment that overlaps by two residues with the previous fragment. The selection is made based on the probabilistic distribution from the tripeptide MD data, ensuring conformational continuity. c. Repeat this process iteratively until the entire chain is assembled.

Ensemble Generation and Validation: a. Repeat the chain assembly process thousands of times to generate a large ensemble of conformations. b. Compute experimental observables (e.g., NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings, SAXS profiles) from the generated ensemble. c. Validate the PMD-CG ensemble by comparing these computed observables with experimental data or with results from a reference simulation (e.g., a REST simulation [14]).

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of computational structural biology, providing atomic-level insights into biomolecular function, dynamics, and interactions crucial for drug development. However, a significant limitation of conventional MD is its inadequate sampling of conformational space within accessible simulation timescales. Biomolecular systems often possess rough energy landscapes with many local minima separated by high energy barriers, causing simulations to become trapped in non-functional states and preventing the observation of biologically relevant conformational changes [15]. This sampling problem is particularly acute in structure refinement projects, where the goal is to generate accurate, experimentally consistent models of protein structures, especially for flexible systems or those with multiple functional states.

Enhanced sampling techniques were developed to overcome these limitations. By employing advanced algorithms that accelerate the exploration of phase space, these methods facilitate the crossing of energy barriers and enable a more thorough investigation of the free energy landscape. This application note details prominent enhanced sampling methods, with a focus on Replica Exchange MD (REMD) and its variants, providing structured protocols and resources to guide researchers in selecting and applying these techniques for efficient structural refinement.

Enhanced sampling methods operate on different principles to improve the efficiency of conformational exploration. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of several major techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Enhanced Sampling Methods for Biomolecular Simulations

| Method | Core Principle | Best Suited For | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Parallel simulations at different temperatures/ Hamiltonians periodically attempt configuration swaps [13]. | Protein folding, peptide aggregation, conformational transitions [13] [15]. | Avoids kinetic trapping; provides correct Boltzmann distribution at all temperatures; highly parallel [13]. | High computational cost (many replicas); choice of temperature range is critical; efficiency decreases for very large systems [15]. |

| Metadynamics | History-dependent bias potential is added to collective variables (CVs) to discourage revisiting previous states [15]. | Protein folding, molecular docking, conformational changes, ligand binding [15]. | Actively drives exploration along predefined CVs; good for calculating free energy surfaces [15]. | Quality depends heavily on correct choice of CVs; risk of non-convergence if CVs are poorly chosen. |

| Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF) | Continuously estimates and applies a bias to counteract the mean force along a CV [16]. | Ion permeation, small molecule translocation, side-chain rotation [16]. | Directly computes the free energy gradient; efficient convergence for low-dimensional CVs. | Requires defined CVs; can suffer from sampling issues in complex landscapes. |

| Simulated Annealing | Artificial temperature is gradually decreased during simulation to find low-energy states [15]. | Structure prediction and refinement of very flexible systems [15]. | Effective global minimum search; relatively low computational cost per simulation. | Does not generate a thermodynamic ensemble; risk of quenching into local minima. |

Among these, REMD has gained widespread popularity for biomolecular applications. Its standard form, Temperature REMD (T-REMD), enhances sampling by facilitating temperature-driven barrier crossing. Several specialized variants have been developed to improve efficiency or target specific problems:

- Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD): Replicas differ in their potential energy function (Hamiltonian), often through varying a coupling parameter

λ, which can enhance sampling in specific degrees of freedom like solvation or side-chain interactions [17]. - Multiplexed REMD (M-REMD): Employs multiple independent runs (multiplexed replicas) at each temperature, allowing exchanges between both temperatures and configurations. This can lead to better convergence in shorter simulation time, albeit at a higher total computational cost [18].

- Gibbs Sampling REMD: An implementation that tests all possible pairs for exchange, not just neighbors, which can improve mixing without requiring additional energy calculations [17].

Replica Exchange MD: Theoretical Foundation and Practical Protocol

Theoretical Foundation of REMD

The replica exchange method is a hybrid algorithm that combines MD simulations with a Monte Carlo sampling scheme. In REMD, ( M ) non-interacting copies (replicas) of the system are simulated in parallel, each at a different temperature (( T1, T2, ..., TM )) or with a different Hamiltonian [13]. At regular intervals, an exchange of configurations between two neighboring replicas (e.g., ( i ) at temperature ( Tm ) and ( j ) at temperature ( T_n )) is attempted. The acceptance probability for this exchange is governed by the Metropolis criterion:

[P(i \leftrightarrow j) = \min\left(1, \exp\left[ \left(\frac{1}{kB Tm} - \frac{1}{kB Tn}\right)(Ui - Uj) \right] \right)]

where ( Ui ) and ( Uj ) are the potential energies of replicas ( i ) and ( j ), and ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant [13] [17]. This criterion ensures detailed balance is maintained, guaranteeing correct thermodynamic sampling. Upon acceptance, the configurations and scaled velocities are swapped, allowing a configuration trapped at a lower temperature to escape at a higher temperature, thereby enhancing conformational sampling across all replicas.

Detailed Application Protocol: REMD of a Peptide Dimer

The following protocol, adapted from a study on the hIAPP(11-25) peptide dimer, outlines a typical REMD workflow using the GROMACS software package [13].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for a Typical REMD Study

| Reagent/Software | Function/Description | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation software package. | Versions 4.5.3 and later support REMD; essential for running simulations and analysis [13] [17]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Parallel computing resource. | Requires MPI library; typically 2 cores per replica for optimal performance [13]. |

| Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) | Molecular visualization and modeling. | Used for constructing initial configurations and visualizing results [13]. |

Protocol Steps:

System Setup and Initial Configuration:

- Construct an initial configuration of your biomolecular system. For the hIAPP(11-25) dimer study, this involved placing two peptides in an extended conformation within a simulation box [13].

- Solvate the system with an appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add necessary ions to neutralize the system's charge.

REMD Parameter Selection and Configuration:

- Number and Spacing of Replicas: The number of replicas is determined by the temperature range and the desired acceptance probability for exchanges (ideally 10-20%). The temperature spacing should be closer at lower temperatures. GROMACS provides an online

REMD calculatorto assist in selecting temperatures based on the number of atoms and desired temperature range [17]. The energy difference-based probability is approximately ( P \approx \exp(-\epsilon^2 \frac{c}{2} N{df}) ), where ( N{df} ) is the number of degrees of freedom [17]. - Simulation Parameters: Prepare a

.mdpparameter file for GROMACS. Key settings include:integrator = mdfor dynamicsdt = 0.002for a 2 fs time step (often requires constraining bonds withconstraints = h-bonds)nsteps = 500000for 1 ns per replica (adjust as needed)pcoupl = Parrinello-Rahmanfor pressure couplingtcoupl = V-rescalefor temperature coupling

- Exchange Attempt Frequency: Set

nstcalclambdaandnsttry(e.g., every 100-1000 steps) to define how often exchange is attempted between neighboring replicas.

- Number and Spacing of Replicas: The number of replicas is determined by the temperature range and the desired acceptance probability for exchanges (ideally 10-20%). The temperature spacing should be closer at lower temperatures. GROMACS provides an online

Running the Simulation:

- Use

gmx_mpi mdrun(or equivalent) with the-multiand-replexflags to execute the multi-replica simulation with exchange. The command might resemble: This runs 16 replicas and attempts an exchange every 500 steps.

- Use

Post-Simulation and Data Analysis:

- Replica Trajectories and Exchange Analysis: Use GROMACS tools like

gmx whamto analyze the replica trajectories and compute the free energy landscape as a function of desired reaction coordinates. - Convergence Assessment: Monitor the time evolution of key observables (e.g., radius of gyration, RMSD, secondary structure content) to ensure sampling has converged.

- Structure Analysis: Cluster the trajectories and analyze the dominant conformations to understand the structural ensemble generated by the REMD simulation.

- Replica Trajectories and Exchange Analysis: Use GROMACS tools like

The logical flow and interdependence of these steps are visualized in the workflow below.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

Enhanced sampling methods are increasingly being integrated with other computational and experimental techniques to tackle complex problems in structural biology and drug discovery.

Integration with Cryo-EM and AI for Modeling Alternative States

A major challenge in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is building atomic models into medium-resolution density maps, especially when the protein exists in multiple conformational states. A recent innovative approach combines generative AI with density-guided MD simulations [19]. This method involves:

- Generating a Diverse Ensemble: Using stochastic subsampling of the multiple sequence alignment in AlphaFold2 to produce a broad ensemble of potential starting structures, rather than relying on a single model.

- Clustering and Selection: Applying structure-based clustering (e.g., k-means) to identify representative models from the AI-generated ensemble.

- Simulation-Based Refinement: Subjecting the cluster representatives to density-guided MD simulations, where a biasing potential steers the model toward the experimental cryo-EM density. A final model is selected based on a compound score balancing map fit and model quality [19]. This hybrid strategy has been successfully demonstrated for membrane proteins like the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR), enabling the resolution of state-dependent differences such as helix bending and domain rearrangement [19].

GPU-Accelerated and Machine Learning-Enhanced Sampling

The computational demand of enhanced sampling is being addressed by leveraging modern hardware and algorithms. The PySAGES library provides a Python-based platform for advanced sampling methods fully accelerated on GPUs, supporting backends like HOOMD-blue, OpenMM, and LAMMPS [16]. Key features include:

- Accessibility: An intuitive interface for managing simulations, defining collective variables, and implementing sampling methods.

- Advanced Methods: Includes a wide range of techniques such as Metadynamics, Adaptive Biasing Force, and the String Method.

- Machine Learning Integration: Employs machine learning strategies, such as artificial neural network sampling, to approximate free energy surfaces and their gradients, which promises to improve the efficiency and scope of enhanced sampling simulations [16].

Enhanced sampling techniques, particularly REMD and its advanced variants, are powerful tools for overcoming the sampling limitations of conventional MD simulations. They are indispensable for projects aimed at refining biomolecular structures and characterizing their free energy landscapes, providing critical insights for rational drug design. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging trends focusing on the integration of experimental data like cryo-EM densities and the adoption of GPU acceleration and machine learning to push the boundaries of simulation size, complexity, and efficiency. By following the detailed protocols and leveraging the tools outlined in this application note, researchers can effectively apply these methods to advance their structure refinement research.

Practical MD Refinement Protocols and Real-World Applications

Molecular Dynamics (MD) refinement has emerged as a powerful technique for improving the accuracy and biological relevance of biomolecular structures, particularly by integrating experimental data to guide physics-based simulations. This process addresses a fundamental challenge in structural biology: computational models, while detailed, are limited by the accuracy of their underlying force fields and can deviate from experimental observations [20]. The standard MD refinement pipeline provides a systematic framework for reconciling these differences, transforming an initial model into a refined structure that is consistent with both physical laws and experimental data. This is especially critical for flexible systems like RNA and intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), where conformational heterogeneity is central to function [21] [5].

The core principle of MD refinement involves using MD simulations to sample conformational space while employing experimental data as restraints to bias the simulation toward structures that agree with real-world measurements. This approach has been successfully applied to structures determined by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), where single-structure models often misrepresent the dynamics of flexible molecules [5]. For researchers in structural biology and drug development, particularly in fields like targeted protein degradation [22], implementing a robust MD refinement pipeline is essential for obtaining reliable structural insights that can guide molecular design.

Key Concepts and Theoretical Foundation

The Need for Refinement in Biomolecular Modeling

MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into biomolecular dynamics but often fail to perfectly reproduce experimental data due to force field inaccuracies and limited sampling times [20] [21]. This discrepancy is particularly pronounced for RNA molecules and IDPs, which sample diverse conformational landscapes. Traditional structural biology methods like cryo-EM often condense data from millions of single-particle images into a single static model, which can misrepresent flexible regions [5]. MD refinement addresses these limitations by ensuring the final structural ensemble is both physically plausible and experimentally consistent.

Approaches to MD Refinement

The MD refinement pipeline can target different aspects of the simulation model, with three primary refinement paradigms:

- Ensemble Refinement: Adjusts populations of conformations within a structural ensemble to match experimental data without drastically altering individual structures [20].

- Force Field Refinement: Modifies the underlying energy function (force field) parameters to improve agreement with experiments across multiple systems.

- Forward Model Refinement: Corrects the functions that map simulated structures to experimental observables, addressing potential inaccuracies in this computational step [20].

These approaches are not mutually exclusive and can be seamlessly combined for more powerful refinement strategies [20].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Prerequisites and Input Assessment

Initial Model Quality Evaluation: Before embarking on MD refinement, critically assess the starting model's quality. Systematic benchmarking on RNA structures from CASP15 reveals that MD refinement provides modest improvements for high-quality starting models but rarely benefits poorly predicted models, which often deteriorate further during simulation [23].

Experimental Data Requirements: The refinement process requires experimental data such as cryo-EM density maps, NMR chemical shifts, or SAXS profiles. For cryo-EM, the resolution range of 2.5-4.0 Å is particularly suitable for ensemble refinement, as single-structure approaches in this range often misrepresent flexible regions [5].

MD Refine Implementation Protocol

MDRefine provides a comprehensive Python package that implements multiple refinement strategies within a unified framework [20]. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow:

Step 1: System Preparation

- Prepare the initial structure (from crystallography, cryo-EM, or computational modeling) using standard molecular simulation setup.

- Add hydrogens, solvate in an appropriate water model, and add ions to neutralize the system.

- For RNA systems, use specialized force fields like RNA-specific χOL3 [23].

Step 2: Restraint Generation

- Process experimental data to generate appropriate spatial restraints.

- For cryo-EM data, convert the density map to a potential that can guide the MD simulation [5].

- Define uncertainty estimates for experimental data to properly weight restraints versus physical forces.

Step 3: Simulation Parameters

- Set simulation length based on system size and complexity: 10-50 ns for fine-tuning reliable models [23].

- Use replica-exchange methods to enhance conformational sampling, especially for heterogeneous systems [5].

- Employ enhanced sampling techniques like Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) for complex conformational transitions [21].

Step 4: Ensemble Refinement via Metainference

- For flexible systems, implement metainference, a Bayesian method that uses multiple replicas to model structural ensembles [5].

- Use a minimum of 8 replicas for simple systems, increasing to 32-64 for complex macromolecules like the group II intron ribozyme [5].

- Run production simulations for at least 10 ns per replica after equilibration.

Step 5: Validation and Analysis

- Calculate agreement metrics between the refined ensemble and experimental data.

- Compare structural properties (RMSD, fluctuations) with original model.

- Assess preservation of known structural features (e.g., base pairing in RNA helices).

Table 1: Quantitative Guidelines for MD Refinement Parameters Based on Benchmarking Studies

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Context and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Length | 10-50 ns | Effective for fine-tuning high-quality starting models; longer simulations (>50 ns) may induce structural drift [23] |

| Number of Replicas | 8-64 | Depends on system complexity; 8 minimum for ribozyme systems, 32-64 for comprehensive sampling [5] |

| Force Field | RNA-specific χOL3 (for RNA) | Specialized force fields improve accuracy for specific biomolecules [23] |

| Ion Conditions | K+ over Na+ | Cation type affects RNA stability; K+ more physiologically relevant [5] |

Practical Guidelines for Effective Refinement

Based on systematic benchmarking, consider these practical recommendations:

- Input Model Selection: MD refinement works best for fine-tuning reliable models and quickly testing their stability, not as a universal corrective method for poor models [23].

- Early Diagnostics: Monitor early simulation trajectories (first 2-5 ns) to diagnose whether refinement is viable; unstable behavior may indicate fundamentally flawed starting models [23].

- Multi-Scale Integration: For complex drug discovery applications like targeted protein degraders, integrate MD refinement with AI-based methods for ternary complex prediction [22].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Refinement Pipelines

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDRefine | Python Package | Implements ensemble, force field, and forward model refinement | General MD refinement with experimental data [20] |

| PROTAC-DB | Database | Repository of PROTAC structures and activity data | Targeted protein degrader design [22] |

| Amber with χOL3 | MD Engine/Force Field | RNA-specific force field for accurate dynamics | RNA structure refinement [23] |

| DeepFoldRNA | Modeling Tool | AI-based RNA structure prediction | Filling gaps in initial RNA models [5] |

| HADDOCK | Docking Software | Integrative modeling of protein complexes | Generating initial ternary complexes for PROTACs [22] |

| Metainference | Simulation Method | Bayesian ensemble refinement with experimental data | Flexible systems with heterogeneous cryo-EM densities [5] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard MD refinement pipeline, integrating key decision points and methodological options based on current best practices:

Applications and Case Studies

RNA Structure Refinement

The application of MD refinement to RNA structures demonstrates its capability to address specific challenges in structural biology. In the case of the group II intron ribozyme, ensemble refinement revealed that a single-structure approach had mismodeled several flexible helical regions. Through metainference-based MD with 32 replicas, researchers generated a structural ensemble that better matched the cryo-EM density while maintaining proper base pairing in RNA helices [5]. This approach proved broadly applicable to RNA-containing cryo-EM structures in the 2.5-4 Å resolution range.

Targeted Protein Degrader Design

In drug discovery, particularly for targeted protein degradation, MD refinement has become integral to predicting ternary complex structures between E3 ligases, proteins of interest, and degrader molecules. Hybrid pipelines combining docking with all-atom MD refinement achieve sub-2 Å accuracy in positioning degraders, enabling more reliable prediction of degradation activity [22]. This application highlights how MD refinement bridges between structural modeling and functional prediction in therapeutic development.

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

For IDPs, traditional MD simulations struggle to adequately sample diverse conformational landscapes due to computational limitations. AI-enhanced MD approaches now leverage deep learning to generate diverse ensembles, which can then be refined against experimental data using methods similar to MDRefine [21]. This hybrid approach overcomes sampling limitations while maintaining physical plausibility.

The standard MD refinement pipeline represents a sophisticated methodology for enhancing biomolecular structures by integrating experimental data with physics-based simulations. As demonstrated across multiple applications, from RNA ribozymes to therapeutic degrader complexes, this approach significantly improves structural accuracy when applied appropriately to suitable starting models. The key success factors include careful assessment of initial model quality, selection of appropriate refinement strategy, adherence to optimal simulation parameters, and rigorous validation against experimental data. For researchers in structural biology and drug discovery, mastering this pipeline provides a powerful approach to extracting biologically meaningful insights from structural models, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics and deepening our understanding of molecular function.

The field of structural biology has undergone a paradigm shift, moving from static structural representations to dynamic ensemble-based models that capture the intrinsic motions essential for protein function. This evolution has been driven by the recognition that proteins are inherently dynamic, with motions spanning an impressive 15 orders of magnitude in timescale (from 10⁻¹⁴ to 10 seconds) [24]. These motions range from sub-picosecond atomic vibrations to millisecond-scale large-amplitude domain reorientations, all of which can be crucial for biological mechanisms such as enzyme catalysis, allosteric regulation, and molecular recognition [24] [25].

No single experimental technique can comprehensively capture this full spectrum of dynamics. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provides high-resolution structural snapshots, particularly for large complexes, but offers limited direct information on timescales of motion. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy excels at characterizing dynamics across picosecond-to-millisecond timescales in solution but faces challenges with larger molecular complexes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomistic detail and continuous trajectories of motions but are constrained by computational timescales and force field accuracy [24] [26] [25]. The integration of these complementary techniques now enables researchers to construct atomistic pictures of protein motions that are inaccessible to any single method in isolation, providing fundamental insights into protein behavior that can guide therapeutic development [24].

Fundamental Principles of Method Integration

Complementary Nature of Experimental Techniques

The power of integrative approaches lies in the complementary strengths of each method, which together provide a more complete picture of protein structure and dynamics.

- Cryo-EM has revolutionized structural biology by enabling near-atomic resolution visualization of large macromolecular complexes and membrane proteins without requiring crystallization. Recent developments in time-resolved cryo-EM allow researchers to capture structural states at different time points, trapping non-equilibrium states typically in the millisecond time frame. Furthermore, cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) enables visualization of proteins within their native cellular environments, preserving spatial relationships in living cells [25].

- NMR Spectroscopy provides unique insights into protein dynamics across multiple timescales through relaxation measurements, lineshape analysis, and exchange experiments. It characterizes motions from pico- to milliseconds, including side-chain reorientations, loop motions, and collective domain movements [24]. NMR is particularly powerful for identifying regions of flexibility and transient interactions that are often crucial for biological function.

- MD Simulations bridge the gap between structural snapshots by providing continuous trajectories of protein motions at atomistic detail. Simulations can reveal transient states and conformational changes difficult to capture experimentally. Recent advances in computing power have enabled simulations to reach biologically relevant timescales of microseconds to milliseconds for many systems [25].

Quantitative Capabilities of Integrated Methods

Table 1: Technical Capabilities of Integrated Structural Biology Methods

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Timescale Coverage | Key Measurable Parameters | System Size Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryo-EM | 2-4 Å (near-atomic) | Static snapshots; millisecond with time-resolved | 3D density maps, Q-scores, conformational states | Limited by particle size < ~50 kDa |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Atomic (for distances/angles) | Picoseconds to seconds | Relaxation rates (R₁, R₂), NOEs, J-couplings, S² order parameters | Typically < 100 kDa (solution NMR) |

| MD Simulations | Atomic (0.1-1 Å deviation) | Femtoseconds to milliseconds (rarely seconds) | Root mean square deviation/fluctuation, free energy landscapes, dihedral transitions | System size and simulation time dependent |

| Integrated Approaches | Atomic to near-atomic | Picoseconds to seconds (indirectly) | Ensemble models, conformational populations, validation metrics (FSC, Ramachandran) | Limited by largest component method |

The integration paradigm typically follows two pathways: 1) MD simulations guided by experimental restraints from cryo-EM and NMR, and 2) Experimental data interpretation enhanced by computational predictions and simulations. The combination allows researchers to overcome the limitations of individual techniques, particularly for modeling complex dynamic processes such as allosteric regulation, enzyme catalysis, and the behavior of intrinsically disordered proteins [25] [27].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Integrative Refinement of Cryo-EM Structures Using Gaussian Mixture Models and Deep Neural Networks

This protocol describes an automated method for refining molecular model series from heterogeneous cryo-EM structures, combining Gaussian mixture models (GMMs) with deep neural networks (DNNs) to capture structural dynamics [28].

- Application Scope: Building molecular model series from cryo-EM datasets with conformational heterogeneity, describing macromolecular dynamics with near-perfect geometry scores.

- Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Model Preparation: Begin with an existing homolog or AlphaFold-predicted model. Place one Gaussian function at each non-hydrogen atom to create a GMM representation [28].

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Using previously obtained cryo-EM heterogeneity analysis results, follow a 1D trajectory in conformational space and group particles by regular intervals [28].

- 3D Reconstruction: Generate 3D reconstructions from each group of particles representing different conformational states [28].

- DNN Refinement: Train deep neural networks to output molecular models matching the corresponding maps of particle groups. The DNN uses a loss function that combines:

- Map-model Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) evaluated in Fourier space

- Stereochemical constraints including Ramachandran plots and side-chain rotamer libraries implemented in differentiable forms [28].

- Multi-Step Refinement: Implement an automatic multi-step process involving:

- Large-scale morphing

- Residue-wise adjustment

- Full-atom refinement considering both map-model agreement and stereochemical constraints [28].

- Validation: Assess output models using PDB validation metrics, Q-scores, and real-space fitting metrics to ensure both geometric quality and map agreement [28].

Key Advantages: Fully automated process without manual intervention; produces models with near-perfect geometry scores; enables direct comparison of structural dynamics with other techniques like MD and NMR [28].

Protocol 2: Ensemble Refinement of RNA Structures Using Metainference MD

This protocol addresses the challenge of refining highly flexible RNA molecules, where single-structure approaches often misrepresent dynamic regions [5].

- Application Scope: Ensemble refinement of mismodeled cryo-EM RNA structures using all-atom simulations, particularly valuable for flexible RNA systems in the 2.5-4 Å resolution range.

- Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Model Assessment: Visually inspect the deposited structure and identify regions with potential mismodeling, particularly RNA helices that are not properly paired despite being predicted by secondary structure analysis [5].

- Gap Filling and Initial Remodeling: Model missing regions using tools like DeepFoldRNA. Perform short MD simulations (2.5 ns) in explicit solvent with restraints to remodel incorrectly paired helices using the ERMSD metric, which ensures proper strand pairing [5].

- Metainference Simulation Setup: Initialize multiple replicas (minimum of 8 required) using equally spaced snapshots from single-structure refinement simulations. Prepare the hybrid energy function that combines:

- Physics-based force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM)

- Spatial restraints enforcing agreement with experimental cryo-EM density maps [5].

- Ensemble Refinement: Run metainference MD simulations (10 ns per replica) using a Bayesian approach that:

- Automatically determines the accuracy of input data

- Optimally weights multiple information sources based on relative accuracy

- Models structural ensembles by improving prior description with experimental information [5].

- Helical Restraint Release: After the first 5 ns of simulation, release helical restraints to allow helices incompatible with the cryo-EM map to unfold naturally while preserving biologically relevant folded states [5].

- Validation and Analysis: Calculate back-calculated density maps from the ensemble and compare with experimental data. Analyze root-mean-square fluctuations to identify flexible regions and assess phylogenetic conservation of stable versus dynamic elements [5].

Key Advantages: Accounts for RNA plasticity and dynamics; reveals inaccuracies of single-structure approaches; produces ensembles compatible with both experimental data and expected RNA geometry; broadly applicable to flexible macromolecular systems [5].

Protocol 3: Integrative Study of Viral Capsid Dynamics

This protocol demonstrates how MAS NMR, cryo-EM, and MD simulations can be combined to study dynamics in large macromolecular assemblies like the HIV-1 capsid [24].

- Application Scope: Characterizing functionally important motions in pleomorphic viral capsids and other large assemblies with inherent structural variability.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare tubular assemblies of capsid proteins that recapitulate salient structural features of native capsids [24].

- Data Collection:

- Acquire Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) NMR spectra to probe dynamics at key functional regions

- Collect cryo-EM data to obtain medium-resolution structural information

- Complement with solution NMR data on isolated domains or constructs [24].

- Integrative Modeling:

- Use MAS NMR experiments and data-guided MD simulations with rigorous model-free statistical analysis

- Derive distinct conformational clusters and their relative populations

- Identify dynamics in functionally important regions like β-hairpins, binding loops, and oligomerization interfaces [24].

- Key Outcomes: Atomic-level dynamic and conformational information on functionally important regions; identification of distinct conformational clusters and populations; insights into allosteric mechanisms and potential therapeutic targeting sites [24].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrative Structural Biology

| Category | Specific Tools | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | AMBER (with χOL3 for RNA), GROMACS, OpenMM, CHARMM | Physics-based MD simulations with experimental restraints | Force field parameterization; explicit solvent models; enhanced sampling |

| Experimental Restraint Tools | Metainference, Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) | Integrating ensemble-averaged data into MD simulations | Bayesian framework; handles noisy, averaged data |

| Cryo-EM Analysis | cryoSPARC, RELION, EMDB | Single-particle analysis and heterogeneity characterization | 3D classification; continuous flexibility analysis |

| NMR Dynamics | Relaxation analysis, CEST, CPMG | Characterizing dynamics across multiple timescales | Picosecond-nanosecond motions; microsecond-millisecond exchange |

| Validation Resources | PDB Validation Server, MolProbity | Assessing model geometry and fit to experimental data | Ramachandran analysis; clash scores; rotamer outliers |

| Specialized Databases | ATLAS, GPCRmd, MemProtMD | MD trajectories for specific protein classes | Pre-computed simulations; reference conformational ensembles |

Data Interpretation and Validation Framework

Successful integration of cryo-EM, NMR, and MD requires rigorous validation at multiple stages to ensure biological relevance and technical accuracy.

- Geometric Validation: All models should be assessed using the PDB validation server, which provides metrics for Ramachandran outliers, rotamer deviations, bond length/angle deviations, and atomic clashes. Near-perfect geometry scores are achievable with current refinement protocols [28].

- Experimental Fit Validation: Evaluate map-model agreement using Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) for cryo-EM and Q-scores for local map-model correlation. For NMR-based ensembles, validate against experimental restraints such as NOEs, J-couplings, and residual dipolar couplings [28] [5].

- Ensemble Validation: For ensemble methods, ensure that the collection of structures represents the experimental data better than any single structure. Calculate ensemble-averaged fits to cryo-EM density and verify that conformational diversity aligns with experimental B-factors or root-mean-square fluctuations [5].

- Biological Validation: Assess whether dynamic regions correlate with functional domains, phylogenetic conservation, and known biological mechanisms. Flexible regions often correspond to functional elements like binding sites or allosteric pathways [5].

The integration of cryo-EM, NMR spectroscopy, and MD simulations has transformed our ability to characterize protein dynamics, moving structural biology from static snapshots to dynamic ensemble-based representations. The protocols outlined here—from GMM-DNN refinement of cryo-EM heterogeneity data to metainference MD for RNA ensembles—provide robust frameworks for tackling complex dynamic processes in biological systems.

Future developments will likely include more sophisticated AI-driven approaches for conformational sampling [27] [21], improved force fields validated by experimental data [5], and enhanced time-resolved techniques that capture functional motions at higher temporal resolution [25]. As these methods continue to converge and evolve, they will further accelerate the exploration of protein structure-function relationships, ultimately impacting drug discovery and therapeutic development for challenging targets.

The prediction of protein structures has been revolutionized by deep learning, with tools like AlphaFold achieving remarkable accuracy for static structures. However, a significant challenge remains in refining these models to capture the dynamic conformational states that are crucial for understanding biological function. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful technique for this refinement, but their success heavily depends on the availability of accurate spatial restraints. This application note details protocols for integrating bioinformatic data—specifically, predicted inter-residue contacts and AI-generated spatial features—as restraints in MD simulations to guide and enhance the refinement of protein structural models. Framed within a broader thesis on molecular dynamics for structure refinement, these methodologies provide a robust framework for researchers and drug development professionals to generate functionally relevant, dynamic conformational ensembles, moving beyond static structural snapshots.

Quantitative Evidence and Performance Metrics

The integration of deep learning predictions with molecular dynamics is not merely theoretical; it is supported by quantitative benchmarks demonstrating its superiority over purely AI-based or traditional physical methods. The table below summarizes key performance data from recent studies and resources.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Hybrid AI-MD Approaches and Key Datasets

| Method / Resource | Key Feature | Performance / Scale | Reference / Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-I-TASSER | Hybrid deep learning & iterative threading assembly refinement | Average TM-score of 0.870 on "Hard" targets, outperforming AlphaFold2 (0.829) and AlphaFold3 (0.849). | [2] |

| MD with Predicted Contacts | MD refinement using predicted distances as restraints | Produces excellent structural models, with force fields helping to correct errors in noisy distance predictions. | [29] |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) | Massive dataset for training neural network potentials (NNPs) | >100 million molecular snapshots; 6 billion CPU-hours of DFT calculations; 10x larger systems than previous datasets. | [10] [30] |

| Dynamicasome | AI model trained on MD-derived features for pathogenicity | Outperformed existing tools (REVEL, PROVEAN) in predicting mutation pathogenicity. | [31] |

| MD for RNA Refinement | MD refinement of RNA models (Amber χOL3 force field) | Short simulations (10-50 ns) improve high-quality starting models; longer runs often induce drift. | [32] [33] |

These data underscore a clear trend: the synergy between AI-predicted restraints and physics-based simulations consistently yields higher accuracy, especially for challenging targets like non-homologous and multidomain proteins.

Workflow for Integrating AI-Generated Restraints in MD

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a typical pipeline that integrates AI-generated predictions with molecular dynamics simulations for structure refinement.

Diagram 1: AI-Restrained MD Refinement Workflow. The process begins with a sequence, generates initial restraints via AI, incorporates them as energy terms in MD, and culminates in a refined structural ensemble.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for implementing the hybrid AI-MD refinement pipeline, based on successful approaches like D-I-TASSER and methods described for leveraging predicted contacts.

Protocol: AI-Restrained MD for Protein Structure Refinement

Objective: To refine an initial protein structural model by incorporating spatial restraints derived from deep learning predictions into molecular dynamics simulations.

I. Initial Restraint Generation

- Deep Learning-Based Restraint Prediction:

- Input: The target protein's amino acid sequence.

- Tools: Utilize deep learning platforms such as DeepPotential, AttentionPotential, or AlphaFold2 to generate multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and predict spatial features [2].

- Key Outputs:

- Inter-Residue Distance Maps: Predict pairwise distances between residues, often formatted as a 2D matrix where each value represents the expected distance between Cβ atoms (Cα for glycine).

- Contact Maps: A binary or probabilistic representation of which residue pairs are in contact (typically < 8Å).

- Hydrogen-Bond Networks: Predict the likelihood and geometry of hydrogen bonds between backbone and side-chain atoms [2].

- Validation: Assess the self-consistency and confidence (e.g., predicted aligned error from AlphaFold) of the predicted restraints.

II. Molecular Dynamics System Setup and Restraint Implementation

Structure Preparation:

- Use the AI-predicted structure or a homology model as the starting conformation.

- Use a tool like

tleap(AmberTools) orpdb2gmx(GROMACS) to add missing atoms, protonate the structure at physiological pH, and solvate it in a water box (e.g., TIP3P) with a buffer of at least 10 Å [33]. - Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Define Restraint Energy Terms:

- Convert the predicted distance maps into a collective variable or an external potential. A common method is to apply harmonic or flat-bottomed restraints on the pairwise distances.

- Example GROMACS

mdpfile snippet: - A corresponding restraint file (e.g.,

restraints.dat) would list the atom pairs, their reference distances (from AI prediction), and force constants.

Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization (e.g., 5,000-10,000 steps) while applying positional restraints on the protein's heavy atoms (force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) to relax the solvent and ions.

- Equilibration MD:

- NVT Ensemble: Heat the system from 0 K to 300 K over 100-500 ps, maintaining restraints on protein heavy atoms.

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate the system for 1-5 ns at 300 K and 1 bar to stabilize the density, again with restrained protein atoms [33].

III. Production Simulation and Analysis

Production Molecular Dynamics:

- Run the production simulation with the AI-derived distance restraints active.

- Simulation Length: The length is system-dependent. For refinement, shorter simulations (10-50 ns) are often sufficient for local relaxation, as longer simulations can induce structural drift [32] [33]. Monitor root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to assess stability.

- Software: GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, or CHARMM are suitable MD engines [27].

- Ensemble Generation: Run multiple replicas (e.g., 3-5) with different initial velocities to improve sampling.

Post-Simulation Analysis:

- Conformational Clustering: Cluster the trajectories to identify the most representative conformations.

- Stability Metrics: Calculate the RMSD, radius of gyration (Rg), and root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of the refined models.

- Validation: Compare the final, refined models against the initial model and, if available, experimental data. Use metrics like TM-score and MolProbity to assess global fold and stereochemical quality.

Validation and Quality Control

Ensuring the validity of the refined models is critical. The following table outlines key metrics and methods for quality control.

Table 2: Key Validation Metrics for Refined Structures

| Validation Aspect | Metric / Tool | Description & Target Value |

|---|---|---|

| Global Fold Accuracy | TM-score | Measures structural similarity. A score >0.5 suggests the same fold; >0.8 indicates high accuracy [2]. |