Molecular Dynamics for Protein-Ligand Complex Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations for analyzing protein-ligand complexes, a critical methodology in structural biology and rational drug design.

Molecular Dynamics for Protein-Ligand Complex Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations for analyzing protein-ligand complexes, a critical methodology in structural biology and rational drug design. It covers foundational principles, including the physical basis of binding and the role of MD in complementing docking studies. The guide explores methodological workflows, from system setup to trajectory analysis, and addresses key challenges such as sampling efficiency and force field selection. Furthermore, it examines validation protocols and comparative analyses with other computational techniques, incorporating recent advances like machine learning integration and AlphaFold2 models. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to enhance the application of MD in biomedical research.

Understanding the Basics: How Molecular Dynamics Reveals Protein-Ligand Interactions

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool in structural biology, providing atomic-level insight into the dynamic behavior of biomolecules. By numerically solving classical equations of motion, MD allows researchers to simulate the physical movements of atoms over time, revealing processes that are often difficult to capture experimentally [1]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying protein-ligand complexes, where understanding binding mechanisms, conformational changes, and interaction energies is crucial for applications in drug discovery and design.

Fundamental Principles and Applications

MD simulations compute the time-dependent behavior of a molecular system based on a potential energy function, or force field. These force fields contain terms for both bonded interactions (bond lengths, angles, dihedral angles) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatics) [1]. With integration time steps typically in the femtosecond range, MD can capture biologically relevant events ranging from local side-chain motions to large-scale conformational changes.

The applications of MD in structural biology are diverse and impactful:

- Protein Folding and Structure Prediction: All-atom MD can predict structures of peptides and small proteins (<80 amino acids) with accuracy comparable to experiments, particularly when template-based modeling methods fail [1].

- Protein-Ligand Interactions: MD simulations help characterize binding sites, identify key residues, and quantify interaction energies, providing crucial information for rational drug design [2].

- Model Refinement: MD-based approaches can refine protein structure models by sampling near-native conformations and integrating limited experimental or bioinformatics data [1].

- Binding Affinity Prediction: By capturing the dynamic nature of molecular recognition, MD simulations contribute to both physics-based and machine-learning approaches for predicting binding free energies [3] [4].

Key Methodologies and Performance Benchmarking

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Conventional MD simulations are often limited to timescales shorter than those required for biologically relevant events like protein folding or ligand unbinding. Enhanced sampling methods address this limitation:

- Replica-Exchange MD (REMD): Multiple copies of the system are simulated at different temperatures, allowing efficient barrier crossing and more thorough conformational sampling [1].

- Metadynamics: Uses a biased potential on pre-defined collective variables to accelerate rare events while still providing thermodynamic information [5].

- Accelerated MD: Modifies the potential energy surface to reduce energy barriers, enhancing sampling of conformational states [1].

Binding Affinity Prediction Protocols

Accurately predicting protein-ligand binding affinity remains a central challenge. Various MD-based approaches have been developed, each with different trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy (MAE/R-value) | Computational Cost | Key Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking | ~2-4 kcal/mol RMSE [6] | Low (<1 minute on CPU) [6] | Fast conformational sampling with empirical scoring functions |

| MM/GBSA & MM/PBSA | R-value: 0.1-0.6 [3] | Medium | Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area solvation |

| Free Energy Perturbation | MAE: 0.8-1.2 kcal/mol [3] | Very High (>12 hours GPU) [6] | Alchemical transformations between ligands |

| QM/MM-M2 Protocols | MAE: 0.60 kcal/mol, R: 0.81 [3] | Medium-Low | Quantum mechanics-derived charges with mining minima conformational sampling |

The QM/MM-M2 approach represents a recent advancement that combines quantum mechanical accuracy with manageable computational cost. This method applies quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) to generate electrostatic potential (ESP) charges for ligands in selected conformers obtained from classical mining minima calculations [3]. The incorporation of polarization effects through QM/MM-derived charges significantly improves accuracy over purely forcefield-based approaches.

Trajectory Analysis and Affinity Prediction

Novel methods continue to emerge that leverage MD simulations for affinity prediction. One approach compares the dynamic behavior of proteins upon ligand binding using MD trajectories [4]. This method quantifies differences in binding site dynamics between ligand systems using similarity metrics like Jensen-Shannon divergence, then correlates these differences with experimental binding affinities. This strategy has demonstrated strong correlations (R-value up to 0.88) for targets like BRD4 and PTP1B [4].

Experimental Protocols

Standard MD Simulation Workflow for Protein-Ligand Complexes

The following workflow describes a typical MD simulation protocol for studying protein-ligand interactions:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for MD Simulations

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Examples/Options |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Defines potential energy terms for molecular interactions | AMBER [1], CHARMM [1], OPLS-AA [1] |

| Water Models | Represents solvent effects explicitly or implicitly | TIP3P, TIP4P (explicit) [1], GB/SA models (implicit) [1] |

| Software Packages | Performs MD simulations and analysis | OpenMM [5], Amber22 [4], GROMACS [1] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Accelerates rare events and improves sampling efficiency | REMD [1], Metadynamics [5], aMD [1] |

| System Preparation | Adds missing atoms, assigns protonation states | H++ [4], PDBFixer, CHARMM-GUI |

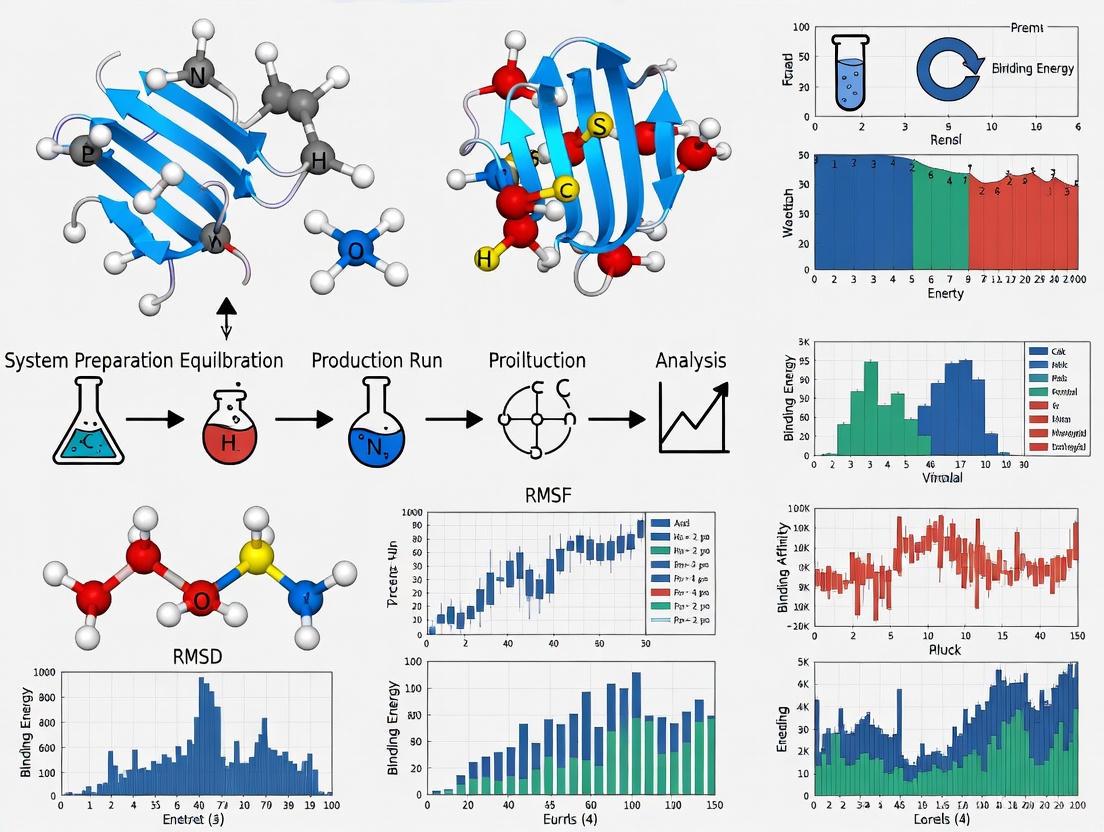

Diagram 1: Standard MD simulation workflow

Step 1: System Preparation

- Start with an experimental or predicted protein-ligand structure (e.g., from PDBbind [2])

- Add hydrogen atoms using tools like H++ at physiological pH [4]

- Assign protonation states of ionizable residues appropriate for the simulation conditions

- For ligands, obtain topology parameters using tools like GAFF (Generalized Amber Force Field) [4]

Step 2: Solvation and Ion Addition

- Place the complex in a cubic water box with a buffer region (typically ≥10.0 Å) using explicit water models like TIP3P [4]

- Add ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration

Step 3: Energy Minimization

- Perform 5,000 steps of steepest descent minimization to remove steric clashes [4]

- Gradually reduce position restraints on heavy atoms if needed

Step 4: System Equilibration

- Run 100 ps NVT simulation at 300 K with restraints on heavy atoms (10 kcal/mol·Å²) [4]

- Follow with 100 ps NPT simulation at 300 K and 1 bar with same restraints [4]

- Use Berendsen or Langevin thermostat and Monte Carlo barostat

Step 5: Production Simulation

- Run unrestrained MD simulation in NPT ensemble (400 ns recommended for convergence) [4]

- Save trajectories every 2-100 ps depending on analysis requirements

- Perform multiple independent trials (≥3) to assess reproducibility [4]

Step 6: Trajectory Analysis

- Remove rotational and translational motions by fitting to reference structure

- Calculate RMSD, RMSF, interaction energies, and other relevant metrics

- For binding affinity prediction, employ specific analysis methods (see Section 3.2)

Binding Affinity Prediction Using Trajectory Similarity

This protocol describes an approach for predicting binding affinities by comparing protein dynamics across different ligand complexes:

Diagram 2: Binding affinity prediction from trajectory similarity

Step 1: Simulation Setup and Execution

- Perform MD simulations for each protein-ligand complex following the protocol in Section 3.1

- Include the apo protein (without ligand) in the simulation set

- Run three independent trials for each system with different random seeds [4]

Step 2: Binding Site Residue Identification

- For each frame, calculate the minimum distance between any heavy atom of a residue and any heavy atom of the ligand

- Define the activity ratio as n/N, where n is the number of frames where the minimum distance <5Å, and N is the total number of frames

- Identify binding site residues as those with activity ratio >0.5 during the simulation [4]

Step 3: Trajectory Similarity Calculation

- Extract trajectories of binding site residues for analysis

- Remove rotation and translation by fitting to backbone atoms of binding site residues

- Estimate probability density functions for each system using Gaussian kernel density estimation with Silverman's rule-of-thumb bandwidth [4]

- Calculate pairwise Jensen-Shannon (JS) divergence between all systems:

Where KL denotes Kullback-Leibler divergence [4]

Step 4: Data Reduction and Correlation

- Build a distance matrix from all pairwise JS divergences

- Perform multidimensional scaling to embed the distance matrix in 3D space

- Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the embedded points

- Correlate the first principal component (PC1) with experimental binding free energies (ΔG) [4]

Step 5: Sign Determination of Correlation

- Use coarse ΔG estimations from docking programs like AutoDock Vina to determine the sign of the PC1-ΔG correlation when experimental data is limited [4]

Implementation Tools and Best Practices

Accessible MD Implementation

For researchers new to MD simulations, user-friendly tools like drMD provide automated pipelines that lower the barrier to entry. drMD uses OpenMM as its simulation engine and requires only a single configuration file, making it particularly suitable for experimentalists seeking to incorporate MD into their research [5]. Key features include:

- Automated handling of routine simulation procedures

- Real-time progress updates and simulation "vitals" checks

- Enhanced sampling options including metadynamics

- Error handling and recovery functions to rescue failed simulations [5]

Data Quality Considerations

The accuracy of MD simulations depends critically on the quality of initial structures. Databases like MISATO address common issues in structural datasets by providing:

- Quantum mechanical refinement of ligand geometries

- Correction of protonation states and hydrogen atom placement

- Extensive molecular dynamics trajectories (over 170 μs total) of protein-ligand complexes [2]

- Validation against experimental data to ensure reliability

Such curated datasets help address limitations in experimental structures from the PDB, including distorted bonds and angles, incorrect atom assignments, and missing hydrogen atoms [2].

Molecular dynamics simulations have evolved from a specialized computational technique to an essential component of structural biology research. The continued development of more accurate force fields, enhanced sampling algorithms, and integration with experimental data ensures that MD will play an increasingly important role in understanding protein-ligand interactions and accelerating drug discovery. As methods like QM/MM-M2 and trajectory similarity analysis demonstrate, combining physical principles with efficient computational strategies enables researchers to achieve experimental-level accuracy in predicting structures and binding affinities while managing computational costs. For practicing researchers, the growing availability of automated tools and curated datasets makes this powerful methodology increasingly accessible for probing the dynamic nature of biological macromolecules.

Protein-ligand interactions are fundamental to virtually all biological processes, including enzyme catalysis, signal transduction, and gene regulation [7] [8]. The precise molecular recognition between a protein and its ligand—characterized by high specificity and affinity—forms the basis of cellular function and communication [7]. A detailed understanding of these interactions is therefore central to molecular biology and is particularly crucial for rational drug design, where the aim is to develop therapeutic compounds that modulate protein function with high precision [7] [8].

The study of these interactions has evolved from early conceptual models like the "lock-and-key" principle to our current understanding, which incorporates protein dynamics and complex energy landscapes [8]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on molecular dynamics for protein-ligand complex analysis, aims to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of the physical basis, key interactions, and energetics governing protein-ligand binding. We will summarize fundamental principles, detail experimental and computational protocols for probing these interactions, and present a practical toolkit for their analysis.

Fundamental Principles of Protein-Ligand Interactions

Binding Kinetics and Thermodynamics

The formation of a protein-ligand complex is a reversible process described by the simple reaction: P + L ⇌ PL where P is the protein, L is the ligand, and PL is the resulting complex [7]. The kinetics of this association are defined by the association rate constant ((k{on})) and the dissociation rate constant ((k{off})). At equilibrium, these constants define the binding affinity through the binding constant ((Kb)) or its inverse, the dissociation constant ((Kd)) [7]:

[Kb = \frac{k{on}}{k{off}} = \frac{[PL]}{[P][L]} = \frac{1}{Kd}]

From a thermodynamic perspective, the spontaneity of the binding event is determined by the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG), which must be negative for favorable binding. The standard binding free energy (ΔG°) is related to (K_b) by:

ΔG° = −RTlnKb

where R is the universal gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin [7]. This free energy change can be decomposed into its enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) components through the fundamental equation:

ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

The enthalpic term (ΔH) primarily reflects the specificity and strength of non-covalent interactions between the protein and ligand, while the entropic term (-TΔS) is a measure of changes in the system's dynamics and order, including the loss of translational and rotational degrees of freedom upon binding, and solvation effects [7] [9].

Key Intermolecular Interactions

The binding affinity and specificity are governed by a combination of several non-covalent interactions between the protein and ligand, often acting in concert [7] [9].

Table 1: Key Non-Covalent Interactions in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Interaction Type | Energy Range (kJ/mol) | Characteristics | Role in Binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals | 0.1 – 4 | Attractive/repulsive forces from induced dipoles; weak but numerous. | Major contributor to binding affinity through cumulative effect. |

| Hydrogen Bonding | 4 – 40 | Interaction between donor (H-bond) and acceptor (lone pair). | Enhances specificity and directionality of binding. |

| Electrostatic (Ionic) | 20 – 40 | Interaction between permanently charged groups (e.g., NH₃⁺...COO⁻). | Provides strong, long-range attraction in the binding site. |

| Cation-π / π-π | Variable | Interaction between cation and aromatic system, or between aromatic rings. | Can contribute significantly to binding energy in specific contexts. |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Entropy-driven | Release of ordered water molecules from non-polar surfaces into the bulk solvent. | Often a major driving force, primarily through entropic gain. |

Binding Models and Conformational Dynamics

Our understanding of how proteins and ligands recognize each other has moved beyond the static "lock-and-key" model. The "induced fit" model proposes that the binding site can adjust its conformation upon ligand binding to achieve optimal complementarity [8]. More recently, the "conformational selection" model has gained support, suggesting that the unbound protein exists as an ensemble of conformations in equilibrium, from which the ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing complementary conformation [8]. In practice, both induced fit and conformational selection mechanisms can be engaged in the same binding process [8].

Quantitative Analysis of Binding Energetics

Accurately measuring and predicting the strength of protein-ligand interactions is a central challenge in biophysics and drug discovery. The following table summarizes the key experimental and computational methods used.

Table 2: Methods for Investigating Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity

| Method | Measured Parameters | Advantages | Disadvantages/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | ΔG, ΔH, TΔS, Kₐ, stoichiometry (n). | Directly measures all thermodynamic parameters in a single experiment. | Requires relatively large amounts of protein; limited sensitivity for very tight binding. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | kₒₙ, kₒff, Kₐ (from kinetics). | Provides real-time kinetic data; high-throughput versions available. | Requires immobilization of one binding partner; potential for artifacts. |

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Kₐ (from equilibrium binding). | Homogeneous assay; suitable for high-throughput screening. | Requires a fluorescent ligand; potential for interference from compound fluorescence. |

| Molecular Docking | Predicted binding pose and affinity score. | Fast, cheap virtual screening of large compound libraries. | Scoring functions are often approximate; limited conformational sampling. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Binding pathways, conformational dynamics, detailed interaction maps. | Provides atomic-level detail and time-resolved data on binding. | Extremely computationally expensive; limited by force field accuracy. |

| Free Energy Calculations | Absolute or relative binding free energies (ΔG). | High theoretical accuracy for affinity prediction. | Even more time-consuming than standard MD; requires significant expertise. |

The following workflow illustrates a typical integrated computational approach for analyzing protein-ligand interactions, combining docking and molecular dynamics simulations:

Diagram 1: A Computational Workflow for Binding Analysis.

Protocols for Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Protein-Ligand Complexes

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up, running, and analyzing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to study protein-ligand interactions, providing insights that are often inaccessible by experimental means alone [10] [11].

System Preparation and Minimization

Initial Structure Retrieval and Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or from molecular docking results (e.g., using AutoDock) [11]. Using visualization and preparation software (e.g., Chimera, VMD):

- Remove crystallographic water molecules and irrelevant co-factors, unless they are part of the binding site.

- Add missing hydrogen atoms according to physiological pH (considering standard protonation states of residues like His, Asp, Glu).

- Ensure the ligand structure has correct bond orders and reasonable protonation states. Parameterize the ligand using tools like CGenFF or ACPYPE to generate topology and parameter files compatible with the chosen simulation force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) [11].

Solvation and Ionization: Place the protein-ligand complex in a simulation box (e.g., cubic, rectangular) with a buffer distance of at least 10 Å between the solute and the box edges. Solvate the system with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model) [11]. Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl).

Energy Minimization: Perform an energy minimization of the solvated system to remove any bad atomic contacts and steric clashes introduced during the setup. This is typically done in two steps: first restraining the heavy atoms of the protein and ligand while minimizing the solvent and ions, followed by a full minimization of the entire system.

Equilibration and Production Run

System Equilibration: Gradually heat the minimized system from 0 K to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) over 50-100 ps in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature), applying restraints to the protein and ligand heavy atoms. Subsequently, run a short simulation (100-200 ps) in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to equilibrate the density of the system, again with restraints. Finally, release the restraints and continue the NPT equilibration until the system properties (e.g., temperature, pressure, energy) stabilize.

Production MD Simulation: Run an unrestrained MD simulation in the NPT ensemble for a duration sufficient to sample the relevant motions and stability of the complex. For many binding interactions, this may range from tens of nanoseconds to microseconds, depending on the system and research question. Maintain a constant temperature (using, e.g., a Langevin thermostat) and pressure (using, e.g., a Nosé-Hoover Langevin barostat). Use a timestep of 2 fs, constraining bonds involving hydrogen atoms with algorithms like SHAKE or LINCS [11].

Trajectory Analysis

Stability Assessment: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and the ligand heavy atoms relative to the starting structure to verify the simulation has reached equilibrium and to assess the overall stability of the complex.

Interaction Analysis: Use tools like ProLIF (Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints) to analyze the MD trajectory and identify specific interactions (hydrophobic, hydrogen bonds, ionic, etc.) between the ligand and individual protein residues over time [12]. This generates a fingerprint that can be visualized as a dataframe or a bar plot to show interaction frequencies.

Diagram 2: MD Trajectory Interaction Analysis with ProLIF.

Energetic Analysis: Employ more advanced methods like the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) or Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) approaches to estimate the binding free energy from simulation snapshots. While less accurate than rigorous free energy methods, they offer a reasonable compromise between computational cost and accuracy for ranking ligands.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Protein-Ligand Interactions

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Structural Datasets | Provides 3D structures and binding data for training/scoring functions and benchmarking. | PDBbind, BioLiP, Binding MOAD, HiQBind [13]. |

| Structure Preparation Workflows | Algorithms to correct common structural artifacts (bonds, protonation, clashes) in PDB files. | HiQBind-WF; crucial for ensuring data quality before simulation [13]. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predicts the binding pose and affinity of a ligand to a protein receptor. | AutoDock 4.2/5, AutoDock Vina; used for virtual screening and pose generation for MD [11]. |

| Force Fields | Defines potential energy functions and parameters for MD simulations. | CHARMM27/36, AMBER ff14SB/ff19SB; determines the accuracy of simulated dynamics [11]. |

| MD Simulation Engines | Software to perform the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion for all atoms. | NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER; the core engine for running production simulations [11]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Programs and libraries to process and analyze the output of MD simulations. | MDAnalysis (for general analysis), ProLIF (for interaction fingerprints) [12]. |

| Binding Affinity Assays | Experimental methods to measure the strength of protein-ligand interactions. | ITC (thermodynamics), SPR (kinetics); used for validation of computational predictions [7] [8]. |

The intricate dance between a protein and its ligand, governed by the fundamental physics of intermolecular forces and energetics, is a cornerstone of biological function and pharmaceutical intervention. This application note has detailed the core principles—from kinetics and thermodynamics to the specific interactions that drive binding—and has provided a practical protocol for using molecular dynamics simulations to probe these interactions at an atomic level. The integration of robust computational methods, like MD and docking, with high-quality structural data and experimental validation, represents a powerful strategy for advancing our understanding of molecular recognition. As methods for predicting complex structures with deep learning mature [8] and computational power grows, the ability to accurately simulate and characterize protein-ligand binding will continue to refine, accelerating the discovery and optimization of new therapeutic agents.

Molecular docking serves as a fundamental tool in structural molecular biology and computer-aided drug design for predicting the binding orientation of small molecule ligands within their target proteins. However, the static nature of docking, which often treats proteins as rigid bodies, fails to capture the dynamic nature of biomolecular recognition. This application note examines the critical limitations of docking approaches and demonstrates how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations provide an essential framework for achieving accurate binding mode prediction. By accounting for full atomistic flexibility, solvation effects, and true thermodynamic stability, MD simulations bridge the gap between static structural predictions and biologically relevant binding characterization, ultimately enhancing the reliability of structure-based drug design.

The Limitations of Static Docking

Molecular docking has become a ubiquitous computational method for predicting protein-ligand interactions, yet it suffers from fundamental limitations that restrict its predictive accuracy. The primary constraint lies in the limited sampling of conformational space and the use of approximated scoring functions that often yield poor correlation with experimental binding affinities [14]. Docking calculations typically treat proteins as largely rigid entities, allowing only minimal side-chain flexibility despite overwhelming evidence that protein flexibility significantly impacts ligand recognition [15]. This rigid-receptor approximation becomes particularly problematic for protein-protein interactions (PPIs) and systems involving large-scale conformational changes.

The scoring function problem represents another critical weakness. As noted in benchmarking studies, "the empirical score is calculated for a single predicted structure, although any dynamic effects can be essential" [16]. These scoring functions frequently fail to account for entropic contributions, solvation effects, and the true dynamics of binding interactions. Research has shown that docking scores often correlate poorly with experimental binding affinities, especially for diverse ligand sets [14]. This limitation persists despite advances in docking algorithms, suggesting inherent constraints in the static docking paradigm.

MD Simulations: Capturing Dynamic Recognition

Fundamental Advantages

Molecular Dynamics simulations address key limitations of docking by modeling system flexibility and temporal evolution. Unlike docking, MD simulations:

- Account for full protein and ligand flexibility, enabling side-chain rearrangements and backbone motions

- Explicitly include solvent effects through water models and ions, critical for modeling true biological conditions

- Provide temporal resolution of binding events and complex stability

- Capture entropic contributions through conformational sampling

- Reveal cryptic binding sites invisible in static crystal structures [15]

MD simulations have demonstrated particular value for studying membrane proteins like GPCRs and flexible systems such as PR-Set7, where accurate prediction requires accounting for substantial protein motion [16]. The ability to observe structural relaxation over time allows researchers to distinguish stable binding poses from metastable configurations that might score well in docking but rapidly dissociate under dynamic conditions.

Quantitative Evidence for Improved Accuracy

Recent large-scale studies provide compelling quantitative evidence for the superiority of MD-based approaches. The PLAS-20k dataset, comprising 19,500 protein-ligand complexes with MD-calculated binding affinities, demonstrates significantly better correlation with experimental values compared to docking scores [14]. This extensive dataset highlights how MD-derived binding affinities, computed using the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) method, more reliably predict experimental results across diverse protein families and ligand types.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Docking vs. MD-Based Binding Affinity Prediction

| Method | Approach | Correlation with Experiment | System Flexibility | Solvent Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Static scoring function | Limited/poor correlation [14] | Restricted | Implicit/approximated |

| MD/MMPBSA | Ensemble averaging from dynamics | Good correlation [14] | Full atomistic | Explicit |

| IFD-MD | Hybrid docking/MD approach | High accuracy (90% success) [17] | Limited backbone, full side-chain | Explicit |

Furthermore, the integration of MD with docking protocols has demonstrated remarkable success rates. Schrödinger's IFD-MD method achieves approximately 90% accuracy in reproducing key features of crystal structures, significantly outperforming both standard docking and earlier induced fit approaches [17]. This hybrid methodology successfully combines the sampling efficiency of docking with the physical fidelity of MD, representing a practical balance between computational expense and predictive accuracy.

Practical Protocols: From Docking to MD Refinement

MD Simulation Workflow for Binding Mode Validation

The following protocol describes a complete workflow for validating and refining docking poses through MD simulation, based on established methods from the OpenFE toolkit and recent literature [18] [14]:

System Preparation

- Input Structures: Start with docked protein-ligand complexes in PDB format

- Parameterization: Generate ligand parameters using appropriate force fields (GAFF2 for small molecules, AMBER ff14SB for proteins) [14]

- Solvation: Solvate the system in an explicit water model (TIP3P) with ion concentrations matching physiological conditions (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [18]

- Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes using the L-BFGS algorithm

Equilibration Protocol

- Minimization: 5,000 steps of minimization with protein heavy atom restraints [18]

- NVT Equilibration: 10 ps simulation with positional restraints on protein backbone atoms while heating system to target temperature (typically 298K) [18] [14]

- NPT Equilibration: 10 ps simulation with semi-isotropic pressure coupling to achieve proper density [18]

Production Simulation

- Duration: 20 ps to nanoseconds-scale simulation depending on system size and research question [18]

- Parameters: Maintain constant temperature (298K) and pressure (1 atm) using Langevin thermostat and Monte Carlo barostat

- Integration: Use 2-4 fs timestep with constraints on bonds involving hydrogen atoms [18] [14]

- Output: Save trajectories every 20 ps for subsequent analysis [18]

The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive workflow:

Binding Pose Stability Assessment

To evaluate binding mode stability during MD simulations:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate ligand and binding site RMSD relative to initial docked structure

- Interaction Persistence: Monitor key protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) over simulation time using tools like PLIP [19]

- Ligand Residence: Assess whether the ligand remains bound or dissociates from the binding site

- Cluster Analysis: Identify predominant binding modes from the trajectory

Studies demonstrate that unstable docking poses often lead to rapid ligand dissociation or significant pose rearrangement during MD simulations, whereas correct binding modes maintain stability [16]. For example, in studies of β2 adrenergic receptor complexes, correct poses maintained stable interactions throughout 150 ns simulations, while incorrect poses showed substantial ligand movement within the binding pocket [16].

Advanced Applications & Integration

Machine Learning and Large-Scale MD Datasets

The emergence of large-scale MD datasets represents a transformative development for binding mode prediction. The PLAS-20k dataset provides binding affinities from MD simulations of 19,500 protein-ligand complexes, creating opportunities for machine learning approaches that leverage dynamic features rather than static structures [14]. These datasets enable:

- Training ML models on ensemble conformations rather than single structures

- Incorporating temporal interaction patterns into affinity prediction

- Developing improved scoring functions informed by MD-derived thermodynamics

Retraining the OnionNet model on PLAS-20k demonstrated enhanced binding affinity prediction compared to models trained solely on static structural data [14]. This integration of MD with ML creates a powerful synergy for future drug discovery applications.

Specialized MD Approaches for Challenging Targets

Advanced MD protocols address specific challenges in binding mode prediction:

Induced Fit Docking MD (IFD-MD) Schrödinger's IFD-MD protocol combines pharmacophore docking, Prime refinement, and metadynamics to predict binding poses for novel scaffolds, achieving 90% success rates while being computationally efficient compared to brute-force MD [17].

Mixed-Solvent MD (MixMD) This cosolvent simulation technique identifies cryptic binding hotspots by observing organic probe molecule localization during simulations, revealing potential allosteric sites invisible in crystal structures [15].

Enhanced Sampling Methods Techniques like Gaussian-accelerated MD (GaMD) and metadynamics reduce the time required to observe binding and unbinding events, making MD practical for drug discovery timelines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for MD-Based Binding Mode Prediction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenMM [18] [14] | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulation | Running production MD trajectories with GPU acceleration |

| PLIP [19] | Analysis Tool | Protein-ligand interaction profiling | Detecting and classifying non-covalent interactions in MD trajectories |

| AMBER Tools [14] | Parameterization | Force field assignment | Generating parameters for proteins (ff14SB) and small molecules (GAFF2) |

| IFD-MD [17] | Workflow | Induced fit docking with MD | Predicting binding poses for novel scaffolds with high accuracy |

| PLAS-20k [14] | Dataset | MD-derived binding affinities | Training ML models on dynamic interaction data |

| g-xTB [20] | Semiempirical QM | Interaction energy calculation | Accurate protein-ligand interaction energy benchmarking |

Molecular Dynamics simulations have evolved from a specialized biophysical technique to an essential component of accurate binding mode prediction. By addressing the critical limitations of static docking—particularly protein flexibility, solvation, and proper thermodynamic sampling—MD provides a physical framework for distinguishing correct from incorrect binding modes. The integration of MD with docking protocols, machine learning, and advanced sampling methods creates a powerful pipeline for structure-based drug design. As demonstrated by large-scale validation studies and practical applications across diverse target classes, MD simulations provide the necessary bridge between static structural predictions and biologically relevant binding characterization, ultimately increasing the success rate of drug discovery efforts.

The accurate prediction of how a small molecule (ligand) binds to its protein target is a cornerstone of computational drug discovery. This process revolves around solving two fundamental challenges: sampling the correct binding pose and scoring the interaction accurately to estimate the binding affinity. While these tasks are interrelated, they present distinct methodological hurdles. Sampling involves efficiently exploring the vast conformational space of the ligand and protein, while scoring requires precisely calculating the subtle energy differences that dictate binding strength. The delicate balance of enthalpic and entropic contributions to the overall binding free energy further complicates this process, as large opposing energy terms must be calculated with extreme precision to yield accurate net binding affinities, which typically fall within a narrow range of -4 to -15 kcal/mol [6]. This application note examines the latest advances in computational protocols designed to address these challenges, providing detailed methodologies for researchers in the field.

The Sampling Challenge: Exploring Conformational Space

Current Methodologies and Gaps

Sampling the correct binding pose is the first critical step in protein-ligand interaction prediction. Traditional docking methods rely on algorithms like Monte Carlo or genetic algorithms to explore the rotational, translational, and conformational degrees of freedom of the ligand within the binding site [21]. However, these methods often struggle with computational efficiency, particularly for large and flexible systems, and can fail to overcome energy barriers to sample the correct pose effectively [21]. The challenge is further compounded when considering protein flexibility, as rigid receptor approximations may miss crucial induced-fit effects.

Advanced Sampling Protocols

Multi-Scale Brownian Dynamics and Molecular Dynamics Workflow:

For calculating association rate constants (kₒₙ), a multiscale approach combining Brownian Dynamics (BD) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations has shown promise [22]. This protocol efficiently captures both long-range diffusional encounters and short-range molecular interactions.

- Step 1 – Brownian Dynamics Simulations: Run BD simulations to model the long-range diffusion of the ligand and generate an ensemble of diffusional encounter complexes. The objective is to produce structures where the ligand comes in close proximity to the active site.

- Step 2 – Structure Selection: Select the generated encounter complexes where the ligand is positioned near the binding site for further analysis.

- Step 3 – Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Use the selected BD structures as starting points for MD simulations. This step captures the subsequent formation of the bound complex with atomic detail, accounting for short-range interactions, solvation effects, and molecular flexibility.

- Step 4 – Analysis: Calculate the association rate constant from the simulation trajectories and validate against experimental data [22].

Synthetic Complex Generation with Rigorous Validation:

To address the scarcity of training data for deep learning models, a novel workflow for the procedural generation of synthetic protein-ligand complexes has been developed [21]. This method enhances the diversity and quality of available data for training docking models.

- Step 1 – Diverse Generation Strategies: Employ an ensemble of generation techniques to create synthetic complexes. This includes:

- PDB Fragmentation: Breaking down existing structures in the Protein Data Bank.

- De Novo Ligand Design: Creating novel ligands conditioned on a specific protein pocket.

- De Novo Protein Design: Designing proteins capable of binding a specific molecule.

- Step 2 – Rigorous Quality Control: Implement a multi-stage validation procedure to filter the generated complexes:

- Physics-Based Filtering: Assess complexes using knowledge of molecular interactions and physical principles.

- ML-Based Filtering: Use machine learning models to identify structures that are indistinguishable from experimental complexes.

- Step 3 – Model Training: Utilize the validated synthetic dataset to retrain established docking models (e.g., Smina, Gnina) or deep learning-based docking tools [21].

The Scoring Challenge: Accurate Binding Affinity Prediction

The Accuracy-Speed Trade-Off

A significant challenge in scoring is the inherent trade-off between computational speed and accuracy. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of current popular methods:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

| Method | Typical RMSE (kcal/mol) | Typical Pearson's R | Computational Cost | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking | 2.0 - 4.0 | ~0.3 | Low (minutes on CPU) | High-throughput virtual screening |

| MM/GBSA & MM/PBSA | Varies widely | 0.1 - 0.7 [3] | Medium | Post-processing of docking poses |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | 0.8 - 1.2 | 0.5 - 0.9 [3] | Very High (12+ GPU hours) | Lead optimization |

| QM/MM-Multi-Conformer (This Note) | 0.60 - 0.78 | 0.81 [3] | Medium-High | High-accuracy affinity estimation |

As evidenced in Table 1, docking is fast but lacks accuracy, while FEP is accurate but computationally prohibitive for large libraries. This creates a "methods gap" for approaches that are definitively more accurate than docking but faster than FEP [6].

AI-Enhanced Scoring Functions

AI-driven methodologies are revolutionizing scoring functions by moving beyond traditional empirical scoring. Geometric deep learning, graph neural networks, and transformers now integrate physical constraints to improve binding affinity estimation [23]. These models have demonstrated enhanced performance in virtual screening, surpassing the accuracy of traditional docking scoring functions [23]. A key advantage of deep learning models is their ability to serve as superior scoring functions for re-ranking poses generated by classical sampling algorithms [21].

Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) Protocol

To achieve high accuracy without the extreme cost of FEP, a protocol combining QM/MM with the mining minima method (VM2) has been developed. This approach addresses the critical limitation of classical force fields—the inaccurate representation of electrostatic interactions via fixed atomic charges [3]. Four specific protocols (Qcharge-VM2, Qcharge-FEPr, Qcharge-MC-VM2, and Qcharge-MC-FEPr) were tested, with the multi-conformer free energy processing (Qcharge-MC-FEPr) protocol delivering the best performance [3].

- Step 1 – Initial Conformer Sampling: Perform a classical VM2 (MM-VM2) calculation to obtain an ensemble of probable ligand conformers and poses within the binding site.

- Step 2 – Quantum Mechanical Charge Derivation: For selected conformers from Step 1, replace the force field atomic charges of the ligand with Electrostatic Potential (ESP) charges derived from a QM/MM calculation. In this calculation, the ligand is treated with quantum mechanics, while the protein environment is handled with molecular mechanics.

- Step 3 – Conformer Selection and Processing (Protocol-Dependent):

- Qcharge-VM2: Use only the most probable conformer for a new conformational search and free energy processing (FEPr).

- Qcharge-MC-FEPr: Select up to four conformers that collectively represent >80% of the probability and proceed directly to FEPr without a new conformational search. This protocol achieved the highest correlation (R=0.81) with experimental data [3].

- Step 4 – Free Energy Calculation: Perform free energy processing (FEPr) on the selected conformer(s) with the new QM/MM-derived charges to compute the final binding free energy.

- Step 5 – Universal Scaling: Apply a universal scaling factor (USF) of 0.2 to the calculated free energy values to correct for systematic overestimation and minimize the error relative to experimental measurements [3].

The workflow for the top-performing Qcharge-MC-FEPr protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Integrated Workflow: Combining Sampling and Scoring

For a comprehensive protein-ligand interaction analysis, sampling and scoring must be integrated. A robust protocol begins with broad sampling using either traditional docking or a generative DL model like a diffusion-based network to produce multiple candidate poses [21]. These poses are then subjected to a multi-stage scoring process, starting with a fast AI-based scoring function to filter out clearly incorrect poses, followed by a more rigorous method like the QM/MM-MC-FEPr protocol for a final, high-accuracy affinity estimate on the top-ranked poses. This tiered approach balances computational efficiency with the need for accuracy in critical predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Software and Computational Tools for Protein-Ligand Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| VM2 (VeraChem) [3] | Software Suite | Implements the Mining Minima method for conformational search and free energy calculations. |

| GROMACS [24] | Molecular Dynamics Engine | Performs high-performance MD simulations for sampling and equilibration. |

| MDAnalysis [25] | Analysis Library | A Python library for analyzing MD trajectories and structural data. |

| VMD/Chimera [24] | Visualization Software | Visualizes molecular structures, trajectories, and binding poses. |

| DiffDock [21] | Deep Learning Model | A diffusion-based generative model for blind molecular docking. |

| Smina/Gnina [21] | Docking Software | Established molecular docking programs with customizable scoring. |

| Python & NumPy | Programming Environment | Core scripting and data analysis for custom workflow implementation. |

The fields of sampling and scoring are being transformed by AI-driven methods and sophisticated multi-scale physical approaches. While challenges in generalization and computational cost remain, protocols that intelligently combine these advances—such as using generative models for sampling followed by QM/MM-informed or AI-powered scoring—are pushing the boundaries of accuracy in binding free energy estimation. As these protocols continue to mature and become more integrated into commercial and open-source software platforms, they promise to significantly accelerate the efficiency and success rate of structure-based drug design.

Practical Implementation: Setting Up, Running, and Analyzing MD Simulations for Drug Discovery

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is an indispensable computational method for studying the dynamics of biomolecular systems with atomic-level detail, providing critical insights that are often difficult to obtain through experimental approaches alone [26]. For protein-ligand systems, MD simulations enable researchers to investigate binding mechanisms, conformational changes, and interaction patterns that underlie molecular recognition and function. This application note provides a comprehensive protocol for conducting MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes, with specific application to the N-terminal domain of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) in complex with a resorcinol-based ligand, though the workflow is broadly applicable to other protein-ligand systems [27]. The protocol is presented within the context of a broader thesis on molecular dynamics for protein-ligand complex analysis research, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require robust methodologies for studying molecular interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Category | Item/Software | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Preparation | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source for initial protein-ligand crystal structures [27] |

| OpenBabel/Compound Conversion | File format conversion and hydrogen addition [27] | |

| Force Fields | AMBER99SB | Force field for protein parameterization [27] |

| GAFF (General AMBER Force Field) | Force field for small molecule parameterization [27] | |

| Solvation & Ions | TIP3P Water Model | Three-site water model for solvation [27] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Ion concentration adjustment (e.g., 0.15 M) [18] | |

| Simulation Engine | OpenMM | Simulation engine for MD calculations [18] |

| Analysis Tools | mdciao | Analysis and visualization of contact frequencies [26] |

| MDtraj | Trajectory analysis and processing [26] |

Workflow Methodology

Initial Structure Preparation

The initial step involves obtaining and preparing the molecular system for simulation. For the Hsp90-resorcinol complex, the structure is obtained from the Protein Data Bank (accession code: 6HHR) [27]. The structure file must be separated into protein and ligand components, as they require different parameterization approaches. Proteins consist of standardized amino acid building blocks, whereas small molecules exhibit diverse chemical structures requiring individual parameterization [27].

Protocol 1.1: Structure Separation

- Input: PDB file containing protein-ligand complex

- Tools: Text processing tools (e.g., grep) or molecular visualization software

- Method:

- Extract protein coordinates by selecting lines that do not match "HETATM"

- Extract ligand coordinates by selecting lines that match the specific ligand residue code (e.g., "AG5E")

- Save as separate PDB files for protein and ligand

- Output: "Protein (PDB)" and "Ligand (PDB)" files [27]

Protocol 1.2: Ligand Hydrogen Addition

- Input: Ligand PDB file

- Tools: Compound Conversion (OpenBabel-based)

- Method:

- Load ligand PDB file

- Add hydrogens appropriate for physiological pH (7.0)

- Output hydrated ligand structure

- Output: "Hydrated ligand (PDB)" file [27]

Topology Generation and System Parameterization

Topology generation defines the constant attributes of atoms, including charges, bonds, and other molecular mechanics parameters. This process must be performed separately for the protein and ligand components using appropriate force fields.

Protocol 2.1: Protein Topology Generation

- Input: Protein PDB file

- Tools: GROMACS initial setup tool

- Method:

- Specify force field: AMBER99SB

- Select water model: TIP3P

- Generate topology with position restraints file

- Output: Protein topology (TOP), structure (GRO), and restraint (ITP) files [27]

Protocol 2.2: Ligand Topology Generation

- Input: Hydrated ligand PDB file

- Tools: acpype tool (AmberTools interface)

- Method:

- Set molecular charge (e.g., 0)

- Specify force field: GAFF

- Select charge method: BCC (bond charge correction)

- Output: Ligand topology files in GROMACS format [27]

Simulation Box Setup and Solvation

The parameterized molecular system must be placed in a biologically relevant environment, typically an aqueous solution with physiological ion concentrations.

Protocol 3: System Solvation

- Input: Protein-ligand complex topology and coordinates

- Tools: OpenMM Modeller or GROMACS solvation tools

- Method:

- Define box shape (e.g., cubic)

- Set solvent padding (e.g., 1.2 nm)

- Add water molecules using specified water model (TIP3P)

- Add ions to achieve physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl)

- Output: Solvated system coordinates and updated topology [18]

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before production simulation, the system must be relaxed to remove steric clashes and equilibrated to the target temperature and pressure.

Table 2: Simulation Stages and Parameters

| Simulation Stage | Key Parameters | Duration | Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Minimization | 5,000 steps of steepest descent [18] | - | Remove steric clashes and high-energy contacts |

| NVT Equilibration | Langevin integrator, 298.15 K [18] | 10 ps [18] | Stabilize system temperature |

| NPT Equilibration | Monte Carlo barostat, 1 atm [18] | 10 ps [18] | Stabilize system density and pressure |

| Production MD | 4 fs timestep, PME electrostatics [18] | Varies (20 ps example [18]) | Generate trajectory for analysis |

Protocol 4.1: Energy Minimization

- Integrator: Steepest descent

- Steps: 5,000

- Constraints: Hydrogen bonds

- Output: Minimized system structure [18]

Protocol 4.2: NVT Equilibration

- Integrator: Langevin with collision rate of 1/ps

- Temperature: 298.15 K

- Duration: 10 ps

- Constraints: Hydrogen bonds

- Output: NVT-equilibrated structure [18]

Protocol 4.3: NPT Equilibration

- Integrator: Langevin with collision rate of 1/ps

- Temperature: 298.15 K

- Pressure: 1 atm with Monte Carlo barostat

- Duration: 10 ps

- Constraints: Hydrogen bonds

- Output: NPT-equilibrated structure [18]

Production Simulation and Analysis

The production phase generates the trajectory data used for analysis of dynamic properties and molecular interactions.

Protocol 5: Production MD Simulation

- Input: Equilibrated system from NPT stage

- Integrator: Langevin with 4 fs timestep

- Duration: Varies by project (e.g., 20 ps to microseconds)

- Nonbonded method: PME with 1 nm cutoff

- Output: Trajectory files (e.g., XTC, TRR), checkpoint files, and log files [18]

Protocol 6: Trajectory Analysis - Contact Frequency Calculation

- Input: Production trajectory

- Tools: mdciao Python API

- Method:

- Compute residue-residue distances using closest heavy-atoms

- Apply distance cutoff (default: 4.5 Å)

- Calculate contact frequencies using formula:

- Output: Contact frequency maps and residue-residue interaction data

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow from Structure to Analysis

Analysis and Visualization Methods

Analysis of MD trajectories provides insights into protein-ligand interactions, conformational dynamics, and binding stability. Contact frequency analysis is particularly valuable for identifying persistent interactions between protein residues and ligands.

Protocol 7: Visualization and Contact Analysis with mdciao

- Tools: mdciao command-line tool or Python API

- Input: Production trajectory and topology files

- Key Parameters:

- Distance scheme: Closest heavy-atoms

- Cutoff distance (δ): 4.5 Å (default, adjustable)

- Output format: Production-ready figures and tables

- Advanced Features:

- Domain-specific annotations (GPCRs, G-proteins, kinases)

- Per-trajectory frequency comparisons

- Consensus nomenclature support for cross-system comparison [26]

Diagram 2: Trajectory Analysis and Contact Mapping Process

This comprehensive workflow provides researchers with a robust methodology for conducting molecular dynamics simulations of protein-ligand complexes, from initial structure preparation through production simulation and analysis. The protocol leverages widely adopted tools and force fields while maintaining flexibility for system-specific adaptations. The integration of contact frequency analysis through tools like mdciao enables efficient extraction of biologically meaningful insights from trajectory data, particularly for drug development applications where understanding protein-ligand interaction dynamics is crucial. This standardized approach ensures reproducibility while providing multiple customization points for researchers investigating diverse molecular systems.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in structural biology and computational drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights into the behavior of proteins and their interactions with ligands. The reliability of these simulations, however, is critically dependent on appropriate system setup. This protocol details best practices for three foundational aspects of MD system preparation: force field selection, solvation, and ionization. Proper configuration of these components ensures physical accuracy and stability in simulations of protein-ligand complexes, which is essential for meaningful research outcomes in areas such as binding mechanism analysis and free energy calculations. The guidelines presented here are framed within a comprehensive research thesis on molecular dynamics for protein-ligand complex analysis, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in computational studies.

Force Field Selection Protocol

Benchmarking Force Field Combinations

The selection of appropriate force fields (FFs) for proteins, ligands, and solvent is paramount for achieving accurate ligand binding free energies in alchemical free energy calculations. A systematic evaluation of 12 different AMBER force field combinations was conducted using the JACS benchmark set, comprising 80 alchemical transformations across eight protein systems (BACE1, TYK2, CDK2, MCL1, JNK1, p38, Thrombin, and PTP1B) [28]. The study compared protein FFs (ff14SB and ff19SB), ligand FFs (GAFF2.2 and OpenFF), and water models (TIP3P, TIP4PEW, and OPC) to identify optimal combinations for binding free energy calculations.

Table 1: Performance of Different AMBER Force Field Combinations for ΔΔGbind Prediction [28]

| Protein FF | Ligand FF | Water Model | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE, kcal/mol) | Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE, kcal/mol) | Pearson's Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ff14SB | GAFF2.2 | TIP3P | 0.87 [0.69, 1.07] | 1.22 [0.94, 1.50] | 0.64 [0.52, 0.76] |

| ff19SB | GAFF2.2 | OPC | 1.00 [0.80, 1.23] | 1.38 [1.10, 1.70] | 0.62 [0.49, 0.75] |

| ff19SB | OpenFF | TIP3P | 1.02 [0.81, 1.26] | 1.40 [1.11, 1.72] | 0.62 [0.49, 0.75] |

| ff14SB | OpenFF | TIP4PEW | 1.04 [0.83, 1.28] | 1.43 [1.13, 1.75] | 0.61 [0.48, 0.74] |

| ff14SB | GAFF2.2 | OPC | 1.05 [0.84, 1.29] | 1.44 [1.14, 1.76] | 0.61 [0.48, 0.74] |

| ff19SB | GAFF2.2 | TIP4PEW | 1.06 [0.85, 1.30] | 1.45 [1.15, 1.77] | 0.61 [0.48, 0.74] |

The results demonstrated that no single combination performed statistically better than all others, but the combination of ff14SB for proteins, GAFF2.2 for ligands, and TIP3P for water consistently delivered excellent performance with a mean unsigned error of 0.87 kcal/mol and a Pearson's correlation of 0.64 against experimental data [28]. This combination is therefore recommended as a reliable starting point for AMBER-TI calculations.

Advanced Force Field and Method Comparisons

Beyond traditional force fields, emerging methods like neural network potentials (NNPs) and tight-binding semiempirical methods offer promising alternatives. Benchmarking against the PLA15 dataset, which provides reference interaction energies at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) level of theory, reveals the comparative performance of these approaches [20].

Table 2: Performance of Low-Cost Methods for Protein-Ligand Interaction Energy Prediction [20]

| Method | Type | Mean Absolute Percent Error (%) | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Spearman ρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g-xTB | Semiempirical | 6.1 | 0.994 ± 0.002 | 0.981 ± 0.023 |

| GFN2-xTB | Semiempirical | 8.2 | 0.985 ± 0.007 | 0.963 ± 0.036 |

| UMA-m | NNP (OMol25) | 9.6 | 0.991 ± 0.007 | 0.981 ± 0.023 |

| eSEN-OMol25-s | NNP (OMol25) | 10.9 | 0.992 ± 0.003 | 0.949 ± 0.046 |

| AIMNet2 (DSF) | NNP | 22.1 | 0.633 ± 0.137 | 0.768 ± 0.155 |

| GFN-FF | Polarizable FF | 21.7 | 0.446 ± 0.225 | 0.532 ± 0.241 |

The semiempirical method g-xTB demonstrated superior accuracy with a mean absolute percent error of 6.1%, outperforming all tested NNPs [20]. Notably, NNPs trained on the OMol25 dataset (UMA-m, UMA-s, eSEN) showed promising results with errors around 10-13%, while other NNPs and the polarizable force field GFN-FF exhibited larger errors. These findings suggest that g-xTB is currently the most accurate method for predicting protein-ligand interaction energies, though the best-performing NNPs show potential for future development.

Figure 1: Force Field Selection Workflow for MD Simulations

Explicit Solvation and System Preparation Protocol

Ten-Step Simulation Preparation Protocol

Proper system solvation and equilibration are critical for stable production simulations, particularly for explicitly solvated biomolecules. A well-defined ten-step protocol has been developed to prepare systems for stable dynamics, comprising a series of energy minimizations and molecular dynamics relaxations designed to allow gradual system relaxation [29].

Table 3: Ten-Step Protocol for Preparing Explicitly Solvated Systems [29]

| Step | Description | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial minimization of mobile molecules | 1000 steps Steepest Descent; Positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų) on heavy atoms | Relieve atomic clashes in solvent/ions |

| 2 | Initial relaxation of mobile molecules | 15 ps NVT MD; Positional restraints (5.0 kcal/mol/Ų) on heavy atoms | Relax solvent and ions around fixed solute |

| 3 | Initial minimization of large molecules | 1000 steps SD; Medium positional restraints (2.0 kcal/mol/Ų) | Partially relax solute while preventing large movements |

| 4 | Continued minimization of large molecules | 1000 steps SD; Weak positional restraints (0.1 kcal/mol/Ų) | Further relax solute with minimal restraints |

| 5 | Solvent and large molecule relaxation | 10 ps NPT MD; Weak positional restraints (0.1 kcal/mol/Ų) | Equilibrate system density with gentle restraints |

| 6 | Final minimization | 1000 steps SD; No restraints | Remove any remaining strains |

| 7 | Heating phase | 10 ps NVT MD; Temperature increase to target | Gradually reach target simulation temperature |

| 8 | Solvent equilibration | 10 ps NPT MD; No restraints | Equilibrate solvent density at target temperature |

| 9 | Final equilibration | Variable length NPT MD | Prepare for production simulation |

| 10 | Density stabilization check | Run until density plateau criteria satisfied | Ensure system density has stabilized |

This protocol employs a strategic approach where mobile molecules (solvent and ions) are allowed to relax before large molecules (proteins, nucleic acids), with positional restraints gradually weakened throughout the process [29]. For proteins and nucleic acids, the protocol recommends allowing substituents (side chains, nucleobases) to relax prior to the backbone to minimize disruption to secondary structural elements.

Absolute Solvation Free Energy Protocol

For calculating absolute solvation free energies, a specialized protocol implements thermodynamic cycle calculations through partial annihilation schemes. This protocol transfers a molecule from vacuum to solvent by decoupling interactions along an alchemical path [30].

Key Steps in Absolute Solvation Protocol [30]:

- System Parameterization: Parameterize the system using OpenMMForceFields and Open Force Field

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the fully interacting system using short MD simulation (NVT and NPT equilibration in solvent leg)

- Alchemical System Creation: Create an alchemical system for free energy calculations

- Minimization: Minimize the alchemical system

- Production Simulation: Equilibrate and production simulate the alchemical system using multistate sampling (HREX, SAMS, or independent) under NPT conditions

- Analysis: Analyze results using MBAR estimator to obtain free energy differences

The protocol uses a lambda schedule that turns off electrostatic interactions first, followed by decoupling of Lennard-Jones interactions with a soft-core potential to avoid instabilities in intermediate lambda windows [30]. Both complex and ligand systems are prepared for transformations, with the overall absolute solvation free energy obtained through summation of free energy differences along the thermodynamic cycle.

Figure 2: Explicit Solvation Protocol Workflow with Restraint Strategy

Ionization Protocols for Electrospray Simulations

Modeling Grotthuss-Diffuse H₃O⁺ for Native ESI

Traditional MD simulations of electrospray ionization have utilized metal ions as charge carriers, despite proteins being primarily detected as protonated ions in experimental mass spectra. A novel protocol now enables simulation of discrete Grotthuss-diffuse H₃O⁺ that dynamically alters amino acid protonation states to model electrospray charging and gaseous ion formation more accurately [31].

Protocol for Simulating Proton Exchange in ESI Droplets [31]:

System Preparation:

- Use protein structures with initial protonation states set to pH 7 values

- Generate protonation state-specific topologies using GROMACS commands

- Create droplets by solvating and centering protein in water box, removing solvent beyond droplet radius

- Charge droplets by replacing water molecules with H₃O⁺ ions (90% of Rayleigh limit)

Simulation Parameters:

- Force Field: CHARMM36 with TIP4P/2005 water

- Temperature: 370 K with ramp of 2.5 K/ns to 450 K to facilitate evaporation

- Integrator: Leapfrog with 1 fs timesteps

- Constraints: LINCS algorithm for hydrogen-bond constraints

Proton Exchange Reactions:

- Implement proton transfer between H₃O⁺ and water for Grotthuss diffusion

- Enable charge neutralization of negatively charged residues (Glu, Asp, C-terminus)

- Facilitate positive charging of His residues

- Exclude Arg, Lys, and N-terminus from deprotonation due to high pKa values

This protocol successfully recreates experimentally observed charge-state distributions and supports the charge residue model as the dominant mechanism of native protein ionization during ESI [31]. The simulations reveal that protonation is highly specific to individual residues and correlates with the formation of localized hydrated regions on the protein surface as droplets desolvate.

Mobile Proton Techniques for Gaseous Proteins

For simulating gaseous protein ions, standard fixed-charge force fields are inadequate because they cannot capture proton mobility within biomolecules. A mobile proton MD approach addresses this limitation by allowing protons to migrate between basic sites based on energy criteria [32].

Key Considerations for ESI Droplet Simulations [32]:

- Temperature Control: Evaporative cooling must be countered by simulated heating (2.5 K/ns ramp)

- Droplet Size: Appropriate radius selection (e.g., 2.5 nm for ubiquitin) to completely solvate proteins while managing computational expense

- Electrostatics: Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for solution simulations; non-Ewald approaches without cutoffs for gas phase

- Trajectory Stitching: Combining multiple short simulations to model extended timescales of droplet evaporation

These protocols confirm that "native" ESI culminates in protein ion release via the charged residue model, with MD-generated charge states and collision cross sections matching experimental data [32]. The mobile proton simulations demonstrate the high propensity of gaseous proteins to form salt bridges and undergo charge migration during collision-induced unfolding and dissociation.

Figure 3: Ionization Protocol for ESI Simulations with Proton Exchange

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Simulations

| Category | Item | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Protein FFs | ff14SB [28], ff19SB [28], CHARMM36 [31] | Define potential energy functions for proteins |

| Ligand FFs | GAFF2.2 [28], OpenFF [28] | Parameterize small molecule ligands | |

| Water Models | TIP3P [28], TIP4P/2005 [31], OPC [28] | Represent solvent water molecules | |

| Software Tools | MD Engines | GROMACS [31], AMBER [28] | Perform molecular dynamics simulations |

| Free Energy | CHARMM-GUI Free Energy Calculator [28] | Setup and analysis of binding free energy calculations | |

| Analysis | PLIP [19], PyMBAR [30] | Analyze interactions and estimate free energies | |

| Specialized Methods | Semiempirical | g-xTB [20], GFN2-xTB [20] | Rapid calculation of interaction energies |

| NNPs | UMA-m, UMA-s [20], AIMNet2 [20] | Machine learning potentials for increased accuracy | |

| System Preparation | Model Building | CHARMM-GUI [28], RDKit [33] | Prepare molecular structures and system topologies |

| Protonation | Constant pH MD [31], Mobile Proton MD [32] | Manage protonation states in simulations |

This protocol has detailed comprehensive guidelines for setting up molecular dynamics simulations focusing on three critical aspects: force field selection, solvation methods, and ionization protocols. For force field selection, the combination of ff14SB for proteins, GAFF2.2 for ligands, and TIP3P for water provides a robust choice for binding affinity calculations, while emerging methods like g-xTB show superior performance for interaction energy predictions. The ten-step explicit solvation protocol offers a systematic approach for stabilizing biomolecular systems before production simulations, gradually relaxing positional restraints to prepare physically realistic systems. Finally, the incorporation of Grotthuss-diffuse H₃O⁺ and mobile proton techniques enables more accurate modeling of electrospray ionization processes, aligning simulations more closely with experimental observations. Together, these protocols provide researchers with a solid foundation for conducting reliable molecular dynamics simulations of protein-ligand complexes, facilitating advances in computational drug discovery and structural biology.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-ligand complexes are indispensable in modern drug discovery, providing insights into conformational dynamics, binding mechanisms, and allosteric regulation that static structures cannot reveal. These simulations enable researchers to understand the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of drug-target interactions, which are crucial for rational drug design [34] [35]. The reliability of these simulations, however, depends critically on proper system preparation, particularly through carefully designed equilibration phases and production run parameters. Without appropriate equilibration, simulations may yield artifactual results that misrepresent the true behavior of the biological system, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions in drug development projects.

This protocol outlines a comprehensive framework for running MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes, with particular emphasis on the crucial equilibration steps that precede production data collection. The methodology presented here follows established best practices in the field [36] and can be implemented using common MD software packages such as GROMACS [37] [38] and OpenMM [18].

Theoretical Foundations of Equilibration

The Necessity of Equilibration

Equilibration serves to gradually relax the simulated system from its initial coordinates toward a stable state that represents the desired thermodynamic ensemble (NVT or NPT). This gradual relaxation is essential because the initial molecular configuration, often derived from crystal structures, may contain steric clashes, unrealistic bond geometries, or improper solvation shell arrangements that would introduce significant artifacts if immediately subjected to production dynamics [36] [38]. The equilibration process typically employs position restraints on the solute atoms (protein and ligand), which are gradually released to allow the solvent and ions to adjust around the macromolecule before granting full flexibility to the entire system.

Thermodynamic Ensembles

MD simulations utilize different thermodynamic ensembles during the equilibration and production phases:

NVT Ensemble (Constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature): This ensemble is used in the first equilibration stage to stabilize the system temperature without allowing volume fluctuations. It establishes correct kinetic energy distribution but may result in improper density [39] [18].

NPT Ensemble (Constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature): This ensemble follows NVT equilibration and allows the system to reach the correct density by permitting volume changes under constant pressure conditions. The NPT ensemble matches experimental conditions more closely and is typically used for production simulations [39] [18].

Equilibration Protocol

The equilibration process consists of a series of methodical steps designed to gradually relax the system. The workflow proceeds sequentially from initial structure preparation through minimization and equilibration in different ensembles, culminating in the production simulation.

Energy Minimization

Energy minimization resolves any steric clashes or unrealistic geometries in the initial structure that would create excessively large forces and destabilize the simulation. The steepest descent algorithm is typically employed for initial minimization steps due to its robustness with poorly conditioned systems, often followed by conjugate gradient or L-BFGS methods for finer convergence [37] [39].

Typical Parameters:

- Algorithm: Steepest descent initially (50,000 steps), then conjugate gradient if needed

- Force Tolerance: 10-1000 kJ/mol/nm (10 kJ/mol/nm is common) [39]

- Constraints: None applied during minimization

NVT Equilibration (Temperature Stabilization)

The NVT ensemble equilibration stabilizes the system temperature while keeping volume fixed. Position restraints are typically applied to protein and ligand heavy atoms to allow solvent and ions to equilibrate around the macromolecule without the solute undergoing large conformational changes [39] [18].

Typical Parameters:

- Duration: 100-250 ps (longer for larger systems) [39] [18]

- Temperature: 300 K (adjust based on system requirements)

- Thermostat: Velocity rescale (modified Berendsen thermostat) or Nosé-Hoover

- Position Restraints: Applied to protein and ligand heavy atoms with force constants of 1000 kJ/mol/nm²

- Time Step: 1-2 fs (when bonds involving hydrogen are constrained)

NPT Equilibration (Density Stabilization)

The NPT ensemble equilibration allows the system to reach the correct density by permitting volume changes under constant pressure. Position restraints are typically maintained but may be gradually reduced in multiple stages for sensitive systems [38] [18].

Typical Parameters:

- Duration: 100-500 ps (monitor density stabilization) [39] [18]

- Temperature: Same as NVT phase

- Pressure: 1 bar (1.01325 atm)

- Barostat: Berendsen (for equilibration) or Parrinello-Rahman (for production)

- Position Restraints: Maintained or reduced relative to NVT phase

- Time Step: 1-2 fs

Table 1: Equilibration Protocol Parameters

| Parameter | Energy Minimization | NVT Equilibration | NPT Equilibration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | 50,000 steps [39] | 100 ps [39] [18] | 100 ps [39] [18] |

| Algorithm | Steepest descent [39] | Leap-frog/Velocity Verlet [37] | Leap-frog/Velocity Verlet [37] |

| Temperature | N/A | 300 K [39] | 300 K [39] |

| Pressure | N/A | N/A | 1 bar [18] |

| Restraints | None | Position restraints on protein-ligand [39] [18] | Position restraints (reduced) [38] |

| Constraints | None | LINCS for bonds [37] | LINCS for bonds [37] |

Production Simulation Parameters

After successful equilibration, the system proceeds to production simulation, where position restraints are removed and trajectory data is collected for analysis. The production phase should be sufficiently long to sample the relevant conformational space for the biological process under investigation [36] [35].

Table 2: Production Run Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Settings | Considerations |

|---|---|---|