Molecular Dynamics Simulation Crashes: A Comprehensive Guide from Prevention to Recovery for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to handle molecular dynamics simulation crashes.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Crashes: A Comprehensive Guide from Prevention to Recovery for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to handle molecular dynamics simulation crashes. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, it explores common error origins in force fields and system setup, examines methodological choices including traditional and machine learning approaches, offers practical troubleshooting for memory and topology issues, and establishes validation protocols using multi-architecture comparison and experimental benchmarking. The guidance integrates insights from recent benchmarks and software updates to address critical stability challenges in biomedical simulation workflows.

Understanding Why Simulations Fail: Core Principles and Common Crash Origins

FAQs: Diagnosing and Resolving Molecular Dynamics Simulation Crashes

My simulation crashes with a "Particle coordinate is NaN" error. What are the most common causes?

This is a frequent crash signature in MD simulations, often triggered by a few key issues [1]. The following diagnostic workflow can help you identify the root cause.

The table below outlines specific debugging actions and solutions for each common cause.

| Root Cause | Diagnostic Action | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Atom Clashes [1] | Visualize the last frames before the crash; look for overlapping atoms or unnatural bond stretching [1]. | Increase minimization steps; use a steepest descent minimizer before switching to conjugate gradient [1]. |

| Incorrect Parameters [1] | Check if extreme forces are localized to a newly parameterized small molecule residue [1]. | Re-parameterize the molecule, paying close attention to torsion and charge parameters [1] [2]. |

| Incorrect Box Size [1] | Monitor the box volume in the simulation log for large, unphysical fluctuations [1]. | For production runs (barostat: false), use the final equilibrated box size from a prior NPT simulation [1]. |

| Strong Restraints/NNP [1] | Temporarily remove positional restraints or neural network potential (NNP) forces from the input file [1]. | Reduce force constants (k values) for restraints or use a smaller integration timestep for NNP instability [1]. |

How can I verify that my force field parameters are appropriate for my system?

Selecting and validating a force field is critical for simulation stability and accuracy. The table below compares major force field types and their validation metrics.

| Force Field Type | Key Characteristics | Recommended Validation Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Additive (Class I) [3] [4] | Static atomic charges; harmonic bonds/angles; Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials [4]. | Reproduce known densities, enthalpies of vaporization, and conformational energies of model compounds [5]. |

| Polarizable [5] | Explicitly models electronic polarization response (e.g., via Drude oscillators) [5]. | Accuracy in varying dielectric environments (e.g., water-membrane interfaces); dipole moments [5]. |

| Machine Learning (MLFF) [6] | Trained on quantum mechanical data; can achieve quantum accuracy [6]. | Performance in finite-temperature MD, not just static energy/force prediction; capture of phase transitions [6]. |

| Specialized (e.g., BLipidFF) [2] | Developed for specific molecular classes (e.g., bacterial lipids) using high-level QM [2]. | Compare simulated properties (e.g., bilayer rigidity, diffusion rates) against targeted biophysical experiments [2]. |

Best Practice Protocol: Force Field Validation

- Reproduce a Known Result: Begin by simulating a well-studied system (e.g., a pure solvent or a standard protein) with established parameters to ensure your simulation setup is correct [7].

- Check System Properties: Plot the potential energy, density, pressure, and temperature of your system over time. The potential energy should be negative and stable, while other properties should fluctuate around their set points [7].

- Validate Structural Properties: For biomolecules, generate a Ramachandran plot to check for realistic protein backbone conformations. For any system, calculate radial distribution functions to identify unphysical atom-atom distances [7].

What is the relationship between the integration time step and simulation instability?

The integration time step is a major factor in numerical instability. Too large a step can cause energy drift, artifacts, or simulation "blow-up," even if the simulation appears stable initially [8].

The Shadow Hamiltonian Concept: A powerful way to understand this is through backward error analysis. The numerical solution from your integrator can be seen as the exact solution for a "shadow" Hamiltonian system. When you use a large time step, you are effectively simulating this slightly different shadow system, and the properties you measure (energy, temperature) will contain a discretization error relative to the original system you intended to simulate [8].

Protocol: Determining an Optimal Time Step

- Start Conservative: Begin with a small time step (e.g., 0.5 fs for all-atom systems with explicit bonds to hydrogen).

- Run Benchmark Simulations: Conduct multiple short simulations (e.g., 1 ns) of your system in the NVE ensemble (microcanonical), using different time steps.

- Measure Energy Conservation: For each time step, plot the total energy of the system over time. A high-quality, symplectic integrator will show stable energy fluctuation without a drift.

- Extrapolate to Zero: For critical applications, run simulations at several different time steps (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 fs) and extrapolate the measured property (e.g., potential energy) to a zero time step to estimate and correct for the discretization error [8].

- Consider Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR): For all-atom systems, HMR allows the use of a larger time step (e.g., 4 fs) by increasing the mass of hydrogen atoms and decreasing the mass of the atoms they are bound to, thus maintaining the total mass while slowing down the fastest vibrational frequencies [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function in MD Stability | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Visualization Software (VMD/PyMOL) [1] | Critical for visually diagnosing crashes by identifying atom clashes, unnatural bond stretching, or atoms moving erratically [1]. | Inspect the starting structure and the last few frames before a crash. |

| Force Field Parameter Databases (MolMod, TraPPE) [3] | Provide validated, digitally available parameter sets for molecules and ions, reducing the need for and errors in manual parameterization [3]. | Ensure compatibility between the functional forms of different parameter sets if mixing [3]. |

| Automated Parameterization Tools (ParamChem, AnteChamber) [5] | Generate initial topology and parameter estimates for novel small molecules, providing a starting point for further validation [5]. | Automatically generated parameters always require careful validation and often optimization [1]. |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software (Gaussian09, Multiwfn) [2] | Used for rigorous derivation of force field parameters, especially atomic partial charges (via RESP fitting) and torsion energy profiles [2]. | Essential for creating accurate parameters for novel molecules not in standard force fields. |

| Structure-Based Drug Design (CSBDD) [4] | Provides the functional form and parameters for simulating proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes with ligands [4]. | The choice of biomolecular force field (CHARMM, AMBER, etc.) must be compatible with the chosen small molecule force field. |

FAQs: General Molecular Dynamics Crash Principles

Q1: What are the first steps I should take when any MD simulation crashes? The first steps are to check the log files and the error message. Log files are crucial for diagnosing the problem. For many MD engines, the error message will include the source file and line number, which can help pinpoint the issue [10] [11]. Immediately after a crash, ensure you collect the log files before shutting down the application or compute node, as they may be stored in a temporary directory and lost upon shutdown [10].

Q2: My simulation ran for hours before crashing. How can I troubleshoot this?

Intermittent crashes after long run times can be difficult to diagnose. Common causes include hardware instability, memory leaks, or accumulation of numerical instabilities. Enable core dumps and use debugging tools like gdb to analyze the crash point [12]. For GPU-accelerated runs, check for rare GPU communication errors, which can manifest as seemingly random crashes [12].

Q3: Are there common system-level issues that cause crashes across different MD software? Yes. Insufficient system memory (RAM) is a frequent cause. The cost in memory and time scales with the number of atoms, and running out of memory will cause the job to fail [13]. For distributed parallel runs, network firewall issues can prevent processes from communicating, especially with floating license servers [14]. Also, ensure the system's regional settings are set to English (United States), as some software has dependencies on this [14].

Q4: What does a "bad bond/angle" error typically indicate? A "bad bond" or "bad angle" error usually signals that the simulation has become unstable. In GROMACS, a "Bad FENE bond" means two atoms have moved too far apart for the bond model to handle [11]. In LAMMPS, an "Angle extent > half of periodic box length" error indicates atoms are so far apart that the angle definition is ambiguous [11]. This often results from incorrect initial structure, poor equilibration, or overly aggressive parameter settings.

GROMACS Troubleshooting Guide

Common Errors and Solutions

| Error Message | Primary Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Out of memory when allocating" [13] | Insufficient RAM for the system size or analysis. | Reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis, shorten the trajectory, or use a computer with more memory [13]. |

| "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database" [13] | The force field does not contain parameters for the residue. | Rename the residue to match the database, find a topology file for the molecule, or parameterize the residue yourself [13]. |

| "Atom Y in residue XXX not found in rtp entry" [13] | Atom names in your coordinate file do not match those in the force field's .rtp entry. |

Rename the atoms in your structure file to match the database expectations [13]. |

| "Found a second defaults directive" [13] | The [defaults] directive appears more than once in your topology. |

Comment out or delete the extra [defaults] directive, typically found in an included topology (.itp) file [13]. |

| "Invalid order for directive xxx" [13] | The order of directives in the .top or .itp file violates the required sequence. |

Ensure directives appear in the correct order (e.g., [defaults] must be first). Review Chapter 5 of the GROMACS reference manual [13]. |

| CUDA Error #717 (or #700) on H100 GPUs [12] | A low-level GPU communication error, often when running multiple simulations per GPU. | This may be an application-level bug. Try a different GROMACS version or reduce the number of parallel simulations per GPU [12]. |

Experimental Protocol: Recovering from a Topology Error

Objective: To fix a "Residue not found in database" error and successfully generate a topology using pdb2gmx.

- Diagnosis: Run

pdb2gmxwith your structure file and note the exact name of the missing residue (e.g., 'L1G'). - Investigation: Check if the residue exists under a different name in your chosen force field's Residue Topology Database (RTD). Consult the force field's documentation.

- Solution A (Renaming): If the residue exists with a different name, rename the residue in your structure (.pdb) file to match the database and rerun

pdb2gmx. - Solution B (Manual Topology): If the residue is absent, you cannot use

pdb2gmxdirectly. Obtain or create a topology (.itp) file for the molecule. Manually include this file in your main topology (.top) file using the#includestatement. - Validation: Run

gromppagain. A successful pass indicates the topology error has been resolved.

AMBER Troubleshooting Guide

Common Errors and Solutions

| Error Category | Symptoms / Error Message | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Floating License | Inability to run AMBER; license check failures. | Verify the Floating License Server (FLS) service is running. Check the License.Lic file configuration and ensure firewalls allow traffic on the license port (default 27001) [14]. |

| Application Crashes | Splash screen not visible or application is inaccessible [14]. | Use the Windows Task Manager to switch to the AMBER application. Turn off Sticky Keys in Windows settings [14]. |

| Unstable Simulation | Simulation crashes without clear error in log. | Ensure your system's region is set to English (United States). Check for and delete the file C:\Program if it exists [14]. |

| Missing Vehicles/Libraries | No vehicles appear in Autonomie workflows [14]. | Edit the project settings via the Autonomie menu and ensure all three default Autonomie libraries are included in the project [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing a Floating License Issue

Objective: To resolve AMBER startup failures related to licensing.

- Verify Service: On the license server machine, open the Services app (

services.msc) and find the "FLS" entry. Verify its status is "Running." If not, start the service. If it fails to start, check thedebug.logfile in the FLS directory for errors [14]. - Check Client Configuration: On the client machine, navigate to

%AppData%\Argonne National Laboratory\AMBER\<Version>\and open theLicense.Licfile. Its contents should be of the form:SERVER <hostname> 0 <port>, followed byUSE_SERVER(e.g.,SERVER AMBER-FLS 0 27001) [14]. - Test Connectivity: From the client machine, open a command prompt and ping the license server by name (e.g.,

ping AMBER-FLS). If this fails, it indicates a network naming or firewall issue that must be resolved by your IT department [14]. - Collect Logs: If problems persist, zip the entire FLS directory and the AMBER

%AppData%directory and email them to support at [email protected] [14].

NAMD Troubleshooting Guide

While the search results did not contain specific NAMD error messages, the principles of MD simulation troubleshooting are universal. The following guide is constructed based on general MD knowledge and the error patterns observed in GROMACS and LAMMPS [11].

Common Inferred Errors and Solutions

| Error Type | Likely Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| "ERROR: All bond coeffs are not set" | Missing force field parameters for bonds. | Ensure all parameters are set in the configuration file or the supplied structure file before running the simulation. |

| "ERROR: Atom count is inconsistent" | Atoms have been lost, often due to extreme forces causing atoms to move too far. | Check the initial structure and minimization protocol. Increase the cutoff margins or use a smaller timestep. |

| "ERROR: Bad global field in log file" | Corruption of output or log files. | Check disk space and file system permissions. Try running from a different directory (e.g., /dev/shm if on Linux). |

| Segmentation Fault (SIGSEGV) | A memory access violation, often from bugs in configuration, plugins, or the software itself. | Run a simpler test case to see if the problem persists. Check the core dump with a debugger. Update to the latest version of NAMD. |

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic MD Crash Diagnosis Workflow

Objective: To methodically identify the root cause of a persistent simulation crash in any MD package.

- Simplify: Create a minimal reproducible test case. Reduce your system size, shorten the simulation time, and remove unnecessary components. If the crash stops, the issue lies in the removed components.

- Check Inputs: Scrutinize your input configuration and structure files. Are all parameters set? Are there any typos or formatting errors? For NAMD, use

sourcecommands to ensure all necessary parameter files are loaded. - Analyze Logs: Examine the last few lines of the output log file. The final error message is your most important clue. Look for warnings about large forces, bad contacts, or parameter issues that preceded the crash.

- Validate Topology: Use utilities like

psfgen(for NAMD) orpdb2gmx -ter(for GROMACS) to ensure your protein termini and ligands are correctly defined and protonation states are appropriate for the simulation pH. - Review Equilibration: Confirm that the system was properly minimized and equilibrated. A crash during production often stems from inadequate equilibration. Check the logs from your NVT and NPT equilibration stages for stability in energy, temperature, and density.

Case Study: A GROMACS CUDA Crash

Scenario: A researcher runs 48 parallel GROMACS simulations on a node with eight H100 GPUs. Randomly, between one and six simulations on the same GPU crash with CUDA error #717 (cudaErrorInvalidAddressSpace) [12].

- Error Analysis: The error code indicates a low-level GPU memory access violation. The fact that crashes only occur for simulations on the same GPU and that re-running from a checkpoint does not reproduce the error suggests a race condition or a bug in the GPU-resident mode under high concurrency [12].

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Solution: As a workaround, the researcher reduced the number of parallel simulations per GPU, which reduced the frequency of crashes. The ultimate fix may require a patch from the GROMACS development team. This case highlights the importance of reporting detailed bugs, including system specs, GROMACS version, and core dumps [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key software and resources essential for diagnosing and resolving crashes in molecular dynamics simulations.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Debugger (e.g., gdb) | Analyzes core dump files generated after a crash to pinpoint the exact line of code and function where the failure occurred. | Used to analyze the stack trace of a GROMACS CUDA crash, revealing the error originated in a GPU constraints function [12]. |

Log Files (exec.log, es_log.txt) |

Primary record of application execution, containing error messages, warnings, and status updates. | The first resource to check for any crash. AmberELEC guides users to collect these from /tmp/logs for diagnosis [10]. |

| Force Field Residue Database | Contains the topology and parameter definitions for molecular building blocks. | Consulted when a "residue not found" error occurs in pdb2gmx to check for naming mismatches or missing entries [13]. |

System Monitoring (e.g., htop, nvidia-smi) |

Monitors real-time system resource usage, including CPU, memory, and GPU utilization. | Used to diagnose an "Out of memory" error by confirming that RAM or GPU memory is exhausted during a simulation [13]. |

| Community Forums | Platforms where users and developers share solutions to common and uncommon errors. | A user posted a detailed report of a random GROMACS CUDA crash, leading to a workaround and developer awareness [12]. |

Understanding Force Fields and Common Pitfalls

A force field is a set of empirical energy functions and parameters used to calculate the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates [15]. In molecular dynamics (MD), the potential energy (U) is typically composed of bonded and non-bonded interactions: U(r) = ∑U_bonded(r) + ∑U_non-bonded(r) [15]. Selecting an appropriate force field is critical for simulation accuracy, yet researchers often encounter significant pitfalls.

A primary mistake is choosing a force field simply because it is widely used, without considering its specific parameterization for your molecules [16]. Force fields are designed for specific molecular classes (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids, small organic ligands), and using an incompatible one leads to inaccurate energetics, incorrect conformations, or unstable dynamics [16]. Furthermore, attempting to combine parameters from different force fields can disrupt the balance between bonded and non-bonded interactions, resulting in unrealistic system behavior [16].

Automated parameter assignment tools can be prone to errors for all but the most straightforward molecules [17]. Complex or heterogeneous systems will almost always require careful processing and sometimes manual intervention for correct atom type assignment [17].

| Pitfall | Consequence | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Incompatible Force Field Selection [16] | Inaccurate interaction modeling, unstable dynamics, unrealistic conformations. | Select a force field developed for your specific system type (e.g., CHARMM36 for proteins, GAFF2 for organic ligands). |

| Mixing Incompatible Force Fields [16] | Unphysical interactions due to differing functional forms, charge derivation methods, and combination rules. | Ensure force fields are explicitly designed to work together (e.g., CGenFF with CHARMM, GAFF2 with AMBER ff14SB). |

| Missing Parameters for Custom Molecules (e.g., ligands) [17] [16] | Simulation crashes or unrealistic behavior for parts of the system. | Use parameter generation tools that match your primary force field; always validate the generated parameters. |

| Incorrect or Outdated Parameters [18] | Affects system dynamics, thermodynamics, and overall properties. | Thoroughly review recent literature for recommended and validated force field versions and parameter sets. |

| Topology Inconsistencies (missing bonds/angles, incorrect charges) [18] | Structural instabilities, failure in energy minimization, non-neutral systems in periodic boundary conditions. | Use tools like gmx pdb2gmx for topology generation; check total system charge; run energy minimization to identify errors. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: My simulation crashes immediately with errors about missing parameters. What should I do?

This is a common issue, especially when simulating molecules not originally in the force field, such as custom ligands or non-standard residues [17].

- Step 1: Identify the Atom(s). Carefully read the error message from your MD engine (e.g., GROMACS). It will typically name the specific atom type or residue for which parameters are missing.

- Step 2: Generate Parameters. Use specialized tools to generate parameters compatible with your chosen force field. For the AMBER force field, the GAFF (General Amber Force Field) and the

antechambertool are common choices. For CHARMM, the CGenFF (CHARMM General Force Field) program and website are used. - Step 3: Validate the Parameters. Do not assume generated parameters are perfect. Perform a series of checks:

- Geometry Optimization: Use quantum chemistry software to optimize the ligand's geometry and compare it with the geometry from the force field parameters.

- Energy Comparison: Compare the conformational energies from quantum mechanics calculations with those from the force field.

- Visual Inspection: Manually inspect the generated topology file for unrealistic bond lengths, angles, or atomic charges.

FAQ: My system seems unstable, with unusual fluctuations. Could this be a force field issue?

Yes, instability can often be traced to force field problems, but other causes must be ruled out [18] [16].

- Check 1: Minimization and Equilibration. Ensure your system underwent proper energy minimization to remove bad contacts and was sufficiently equilibrated to stabilize temperature and pressure [16]. Inadequate equilibration means the system does not represent the correct thermodynamic ensemble.

- Check 2: Force Field Compatibility. If your system contains different molecule types (e.g., a protein, a ligand, and a membrane), confirm that all parameters come from compatible force fields. Mixing non-compatible force fields is a common source of instability [16].

- Check 3: Topology Integrity. Verify your system topology for errors like missing bonds or angles, which can cause structural instabilities [18]. Also, check that the total charge of the system is correct, as an incorrect net charge can cause severe artifacts in periodic boundary conditions [18].

FAQ: How can I validate that my chosen force field is appropriate for my system?

A simulation that runs without crashing is not necessarily correct [16]. Proper validation is essential.

- Compare with Experimental Data: Where possible, compare simulation observables with experimental data. This can include:

- Comparing root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) with experimental B-factors from crystallography.

- Comparing NMR observables like Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) distances or scalar coupling constants with their simulated counterparts [16].

- Check Physical Properties: For some systems, you can compute bulk properties like density or diffusion coefficients and compare them with known experimental values.

- Consult the Literature: Research what force fields are commonly used and validated for systems similar to yours. Community best practices are a valuable guide [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software tools and resources essential for addressing force field-related challenges.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| CGenFF (CHARMM General Force Field) [16] | A program and web service used to generate parameters for small molecules within the CHARMM force field family, ensuring compatibility. |

| GAFF/GAFF2 (General Amber Force Field) [16] | A general-purpose force field for organic molecules, designed to be used with the AMBER family of force fields. Parameters are often generated using the antechamber tool. |

| ATB (Automated Topology Builder) [17] | A database and tool that provides optimized molecular topologies and parameters, though it may not contain highly complex molecules like asphaltene. |

| Moltemplate [17] | A molecule builder for LAMMPS that supports some force fields like OPLSAA and AMBER, helping to construct complex systems and assign parameters. |

| InterMol [17] | A conversion tool that can translate parameter files from other MD packages (like GROMACS, CHARMM, AMBER) for use in other simulation software, aiding in force field compatibility. |

| VMD/TopoTools [17] | A visualization and analysis program with scripting capabilities (Tcl) that can be used for complex topology building and parameter assignment, offering fine-grained control. |

Experimental Protocol: Force Field Parameterization for a Novel Ligand

This protocol outlines the methodology for generating and validating force field parameters for a custom ligand, a common requirement in drug development research.

Objective: To integrate a novel ligand into an MD simulation using the AMBER ff14SB force field for the protein, ensuring consistent and physically accurate parameters for the ligand.

1. Initial Structure Preparation

- Obtain or draw the 3D structure of the ligand.

- Use a tool like Avogadro or GaussView to perform a preliminary geometry optimization using quantum chemical methods (e.g., HF/3-21G*) to obtain a reasonable starting structure.

2. Quantum Chemical Calculations

- Use quantum chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian or ORCA) to perform a more advanced geometry optimization and frequency calculation (e.g., at the B3LYP/6-31G* level) to ensure the structure is at a local energy minimum (no imaginary frequencies).

- Perform an ESP (Electrostatic Potential) calculation at the same level of theory. The ESP is used to fit the atomic partial charges for the ligand.

3. Parameter Generation with antechamber and parmchk2

- Use the

antechamberprogram (part of the AMBER tools) to automatically generate the ligand topology. A typical command is:antechamber -i ligand.log -fi gout -o ligand.mol2 -fo mol2 -c resp -at gaff2This command reads the Gaussian output (ligand.log), assigns GAFF2 atom types, and derives RESP charges, outputting a.mol2file. - Use

parmchk2to check for and generate any missing force field parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals):parmchk2 -i ligand.mol2 -f mol2 -o ligand.frcmod

4. System Building and Validation

- Incorporate the generated

.mol2and.frcmodfiles into the larger system topology (e.g., the protein-ligand complex) usingtleap. - Visually inspect the final structure in a program like VMD or PyMOL to check for unrealistic atom placements or clashes.

- Run a short, gas-phase MD simulation of the ligand alone and analyze the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to see if the geometry remains stable, indicating reasonable internal parameters.

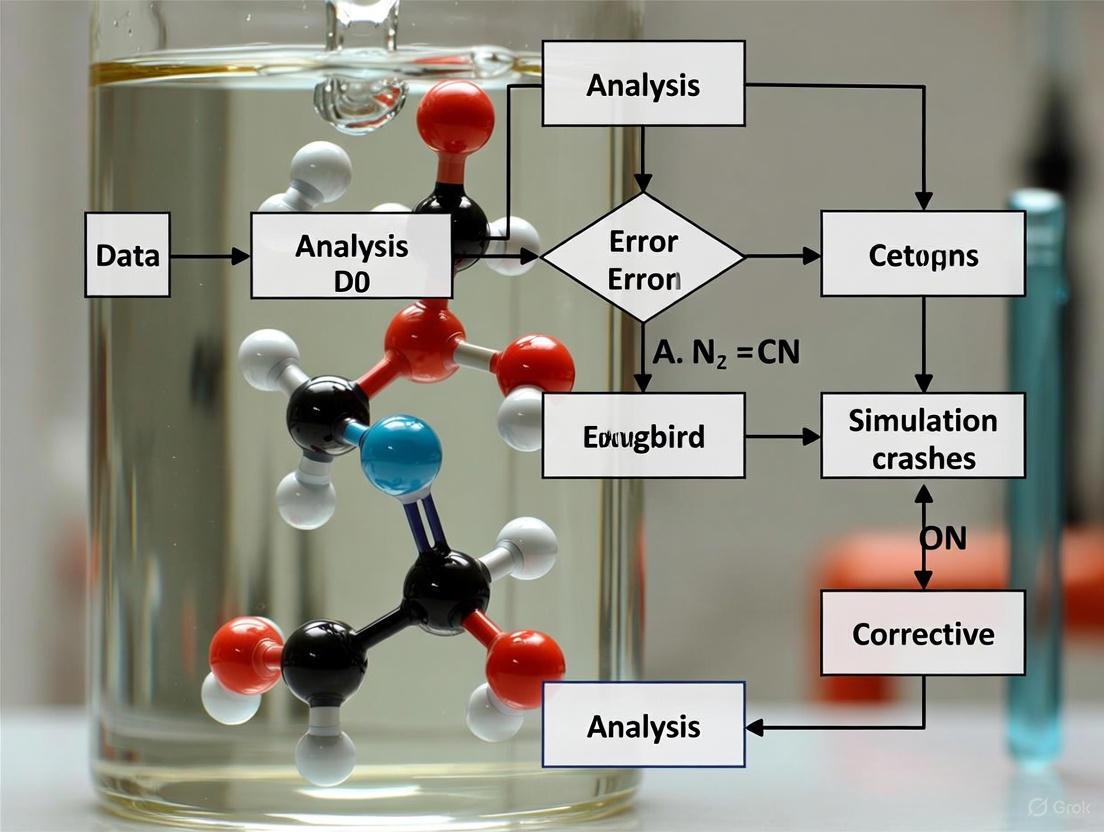

Workflow for Parameter and Topology Generation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for generating and validating force field parameters, a critical process for avoiding simulation crashes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the most immediate danger of making the simulation box too small?

A box that is too small forces atoms to interact with their own periodic images, creating unphysical forces that can destabilize the entire simulation. This often manifests as a "blowing up" of the system, where atoms gain extremely high velocities and the simulation crashes. A common specific error is the box size << cutoff error, where the chosen interaction cutoff distance is larger than the box itself, making neighbor list construction impossible [19].

Q2: I get a "box size << cutoff" error even though my box seems large enough. What could be wrong? This can occur if you have extremely asymmetric box dimensions. For instance, if one dimension of your box is very small (e.g., for a 2D simulation) but you have very large particles elsewhere in the system, the particle diameters can dictate a large global cutoff. This large cutoff may then exceed the smaller box dimension, triggering the error [19]. The solution is to model the large particles differently, such as using a wall potential instead of explicit atoms [19].

Q3: My simulation crashes with a " Particle coordinate is NaN" error immediately after solvation. What should I check first? This is a classic symptom of atomic clashes. Your first step should be to visualize the output structure of your solvation step [1]. Look for atoms from the protein and the solvent that are occupying the same space. Running a longer energy minimization can sometimes resolve these clashes [1]. Furthermore, always ensure your solvation box has a sufficient margin (e.g., at least 10 Å) around your solute [20].

Q4: How can incorrect ion placement cause a crash? Placing ions too close to the solute or to each other creates severe steric clashes. This results in impossibly high forces and potential energy during the first steps of minimization or dynamics, leading to a crash [1]. Ion placement algorithms should ensure a minimum safe distance from the solute and between the ions themselves.

Q5: Why does my topology have missing parameters after using pdb2gmx?

This error (Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database) means the force field you selected does not contain a definition for the molecule or residue 'XXX' in your input file [21]. This is common for non-standard residues, cofactors, or ligands. You cannot use pdb2gmx for these molecules; you must obtain or create a topology for them separately and include it in your system's topology file [21] [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Step-by-Step Protocol

When faced with a crash suspected to be from system setup, follow this investigative protocol to identify the root cause.

Step 1: Visualize the Initial Configuration

- Methodology: Before running any simulation, use a molecular visualization tool (e.g., VMD, PyMol) to inspect the output files of your system setup steps (the final

.groor.pdbfile aftersolvateandgenion). - Rationale: Many setup errors, like grossly oversized boxes or atoms placed on top of each other, are immediately obvious to the eye [1] [23].

Step 2: Run a Multi-Stage Energy Minimization

- Methodology: Do not proceed if minimization fails. Start with the steepest descent algorithm for its robustness. If it fails, run a short minimization with a very small step size (e.g., 0.001) and write a trajectory to see where atoms move violently [1].

- Rationale: Minimization resolves atomic clashes by finding the nearest local energy minimum. A failure indicates the initial structure is too unstable, often due to the errors discussed here [1].

Step 3: Systematically Enable Checks during Initial MD

- Methodology: If the simulation crashes during the first steps of equilibration, run it with extremely conservative settings for a few picoseconds [1]:

- Set

nstlist = 1to update the neighbor list every step. - Reduce the timestep to 0.1-0.5 fs.

- Output a trajectory every step (

nstxout = 1) to catch the exact moment of failure.

- Set

- Rationale: This helps identify the specific atoms and interactions causing the instability [1].

Step 4: Analyze Key Log File Outputs

- Methodology: Scrutinize the log file from the failed run. Key things to monitor are [7]:

- Potential Energy: It should be negative and stable. A very high or

NaNvalue indicates a severe problem. - Pressure and Density: Large, unphysical fluctuations can indicate an unstable box size.

- Maximum Force: This value should decrease during minimization and remain reasonable during MD.

- Potential Energy: It should be negative and stable. A very high or

The logical relationship between the primary setup errors and the subsequent simulation diagnostics can be visualized as a troubleshooting pathway, as shown in the diagram below.

Table 1: Key software tools and resources for diagnosing and resolving system setup errors.

| Tool / Resource | Primary Function in Troubleshooting | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Viewer (VMD, PyMOL) | Visual inspection of initial coordinates, solvation, and ion placement; identifying clashes [1] [23]. | The first and most crucial tool. Check the final output of every setup step. |

| Energy Minimization Log | Analyzing the convergence of potential energy and maximum force to assess structure stability [7]. | Failure to converge indicates a fundamentally unstable starting structure. |

pdb2gmx & x2top |

Generating topologies for standard amino acids/nucleic acids (pdb2gmx) or simple molecules (x2top) [21]. |

Not suitable for non-standard molecules; know the limits of your force field [21]. |

| Neighbor List Logs | Checking for warnings about the box being too small for the chosen cutoff [19]. | Heed warnings about "communication cutoff" or "box size << cutoff" [19] [23]. |

| Force Analysis (Advanced) | Some MD engines can write force data; visualizing force vectors can pinpoint atoms experiencing extreme interactions [1]. | Computationally expensive and complex, but invaluable for diagnosing subtle parameterization errors [1]. |

Critical System Setup Parameters and Diagnostics

Adhering to established numerical guidelines is essential for avoiding setup-related crashes. The table below summarizes critical parameters to monitor.

Table 2: Quantitative guidelines and diagnostics for key system setup parameters.

| Parameter | Recommended Value / Threshold | Diagnostic Action if Violated |

|---|---|---|

| Solvation Box Margin | ≥ 1.0 nm (10 Å) from solute to box edge [20]. | Increase the margin and re-solvate. A smaller margin risks unphysical PBC interactions [20]. |

| Interaction Cutoff | Must be less than half the shortest box dimension under PBC [19]. | Increase the box size or (cautiously) reduce the cutoff. A "box size << cutoff" error will occur [19]. |

| Potential Energy | Should be a large, negative value [7]. | A positive or NaN value indicates severe atomic clashes or incorrect topology. |

| Maximum Force | Should converge to a value near zero during minimization. | A persistently high value indicates residual clashes or incorrect parameters. |

Key Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Solvation and Ion Placement via Minimization

- Input: The final coordinate and topology file after system setup.

- Procedure: Perform energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm. Use a conservative step size (e.g., 0.01 nm) and a high number of steps (e.g., 5000). Run until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Expected Outcome: The potential energy decreases smoothly and becomes negative, and the maximum force converges below the threshold.

- Troubleshooting: If minimization fails, visualize the trajectory to see which atoms are moving erratically, indicating a local clash [1].

Protocol 2: Checking for Stable Box Dimensions via Equilibration

- Input: The minimized system structure.

- Procedure: Run a short NPT equilibration (e.g., 100-500 ps). Monitor the box dimensions, density, and pressure over time.

- Expected Outcome: The box volume and density fluctuate around a stable average value. The pressure fluctuates around the target value (e.g., 1 bar).

- Troubleshooting: Large, systematic drifts in density or extreme pressure spikes suggest the initial box size was far from the equilibrium state, which can strain the barostat and lead to crashes [1].

Recent Advances in Simulation Stability from Current Literature (2024-2025)

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational method based on Newton's laws of motion to study the structure, dynamics, and properties of matter by simulating the motion of atoms or molecules and their interactions [24]. Simulation stability refers to the ability of an MD simulation to run successfully to completion without numerical failures, unphysical behavior, or premature termination. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, maintaining simulation stability is crucial for obtaining reliable, reproducible results in fields ranging from drug design to materials science.

Recent literature highlights several persistent challenges to simulation stability. MD simulations of complex systems often face difficulties stemming from the amorphous and heterogeneous nature of materials, making it challenging to define accurate initial structures [25]. Key processes such as hydration and ion transport involve slow dynamics with timescales ranging from seconds to years, far exceeding the typical nanosecond to microsecond range of classical MD simulations [25]. Additionally, achieving realistic composition models that reflect complex chemical environments imposes extremely high computational demands [25].

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance and methodologies to address these stability challenges, leveraging the most recent advances in MD simulation techniques from 2024-2025 literature.

Troubleshooting Guides: Resolving Common Simulation Instabilities

Force Field and Parameterization Issues

Table 1: Force Field Selection and Parameterization Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Validated Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unphysical bond stretching/breaking | Incorrect force field parameters for specific bond types | Use OPLS4 forcefield parameterized for specific properties [26] | Accurate prediction of density (R²=0.98) and ΔHvap (R²=0.97) for solvent systems [26] |

| Atom overlap or extreme forces | Incompatible van der Waals parameters between different molecule types | Implement ReaxFF reactive force field for complex chemical systems [24] | Successful modeling of RDX nitramine shock waves and silicon oxide systems [24] |

| System energy minimization fails | Inadequate treatment of electrostatic interactions for charged systems | Apply COMPASSIII forcefield for polymeric and inorganic materials [27] | Accurate modeling of silicone materials' elastic modulus (2.533 GPa) and tensile strength (5.387 MPa) [27] |

| Unrealistic dihedral angles | Missing or improper torsion parameters | Utilize embedded-atom method for transition metals and alloys [24] | Accurate simulation of grain boundaries and interfacial diffusion behavior [24] |

Experimental Protocol: Force Field Validation

- Initial Testing: Run short simulations (50-100 ps) of isolated molecules or small systems to validate basic structural properties against experimental or quantum mechanical data.

- Property Comparison: Calculate density, enthalpy of vaporization, or radial distribution functions and compare with available experimental data as done in solvent mixture studies [26].

- Gradual Complexity: Increase system complexity gradually, starting with pure components before proceeding to multicomponent mixtures [26].

- Force Field Refinement: For reactive systems, implement ReaxFF which has been successfully applied to hydrocarbons, silicon oxide systems, and high-energy materials [24].

System Setup and Equilibration Failures

Table 2: System Initialization and Equilibration Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Validated Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation box size instability | Inadequate periodic boundary conditions | Use miscibility tables from CRC handbook to ensure homogeneous mixtures [26] | Successful creation of 30,142 formulation examples spanning pure components to quinternary systems [26] |

| Poor energy conservation | Incorrect time step or integration algorithm | Employ multistep methods for use in molecular dynamics calculations [24] | Improved simulation stability for solid/liquid interface migration kinetics [24] |

| Temperature/pressure oscillation | Overly aggressive thermostat/barostat settings | Apply simulation protocols validated for specific systems (e.g., 10 ns production MD for solvent properties) [26] | Accurate calculation of packing density, ΔHvap, and ΔHm with good experimental correlation (R² ≥ 0.84) [26] |

| Solvation layer errors | Improper solvation or ion placement | Use modified tobermorite models with controlled water adsorption for hydrated systems [25] | Successful modeling of calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (CASH) with accurate radial distribution functions [25] |

Experimental Protocol: System Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent algorithm followed by conjugate gradient method to remove bad contacts.

- Gradual Heating: Increase temperature gradually from 0K to target temperature in steps of 50K with 10-20ps simulations at each step.

- Equilibration Phases: Conduct NVT equilibration (constant particle number, volume, and temperature) followed by NPT equilibration (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature).

- Stability Checks: Monitor potential energy, temperature, and density for stability before proceeding to production runs, following protocols used in dental material simulations [27].

Performance and Hardware Limitations

Table 3: Computational Resource and Performance Issues

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Validated Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation crashes with large systems | Memory limitations or insufficient RAM | Leverage GPU accelerators and high-performance computing clusters [24] | Enabled simulation of ultra-large-scale data for complex metallurgical systems [24] |

| Unacceptably slow simulation speed | Inefficient parallelization or outdated hardware | Implement machine learning potentials to reduce computational cost [24] | Development of machine learning interatomic potentials for Ni-Mo alloys [24] |

| Inconsistent results across runs | Hardware-dependent numerical precision | Utilize consistent simulation protocols across all systems [26] | Successful high-throughput screening of 30,000 solvent mixtures with consistent results [26] |

| Trajectory file corruption | Storage I/O limitations during simulation | Use LAMMPS, DL_POLY, or Materials Studio with optimized I/O settings [24] | Reliable simulation of complex metallurgical systems and interfacial behaviors [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most significant recent advances in MD simulation stability from 2024-2025 literature?

Recent advances focus on integrating machine learning with MD simulations, developing specialized force fields, and creating high-throughput simulation protocols. Specifically:

- Machine Learning Integration: ML potentials now enable accurate simulation of complex systems with reduced computational cost, as demonstrated in studies of Ni-Mo alloys [24].

- High-Throughput Protocols: Systematic approaches for generating large datasets (30,000+ formulations) with consistent simulation parameters ensure reproducible results [26].

- Advanced Force Fields: Development of reactive force fields like ReaxFF for specific chemical systems improves stability for reactive simulations [24].

Q2: How can I improve simulation stability for multicomponent systems with more than 10 different components?

For complex multicomponent systems:

- Use experimentally derived miscibility tables to ensure component compatibility before simulation [26].

- Implement the new FDS2S machine learning approach which outperforms other methods in predicting simulation-derived properties for formulations [26].

- Leverage high-throughput screening with sequential component addition rather than simulating all components simultaneously [26].

Q3: What are the best practices for maintaining stability during polymerization simulations?

Based on recent dental material research:

- Use COMPASSIII force field with Forcite module for polymerization dynamics [27].

- Simulate polymerization kinetics using Kinetix and DMol3 modules to analyze dimensional stability under various stresses [27].

- Validate polymerization success by comparing calculated mechanical properties (elastic modulus, tensile strength) with expected values [27].

Q4: How can I handle the slow dynamics problem in MD simulations, where processes occur over timescales far exceeding practical simulation times?

Addressing timescale limitations:

- Focus on key descriptors that can be extracted from shorter simulations but correlate with longer-term properties [26].

- Implement advanced sampling techniques and multiscale modeling approaches that are becoming more feasible with GPU acceleration [24].

- For specific systems like cement hydration products, utilize well-validated initial structures (e.g., modified tobermorite) that represent equilibrated states [25].

Q5: What software tools show the most promise for improving simulation stability in complex systems?

Recent evaluations indicate:

- LAMMPS and Materials Studio: Show robust performance for complex metallurgical systems and interfacial behaviors [24].

- BIOVIA Materials Studio 2020: Successfully models polymerization dynamics and mechanical properties for dental materials [27].

- Specialized Codes: For specific applications like oil-displacement polymers, customized simulation approaches are being developed that address domain-specific stability challenges [28].

Advanced Stabilization Methodologies

Machine Learning-Enhanced Stability

Recent advances demonstrate that machine learning significantly enhances MD simulation stability through:

- Formulation-Property Relationships: The new FDS2S approach outperforms other methods in predicting simulation-derived properties, enabling more stable simulation parameter selection [26].

- Active Learning Frameworks: These identify promising formulations 2-3 times faster than random guessing, reducing unstable simulation attempts [26].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Identifies top features relevant to formulation-property relationships, allowing optimization of simulation parameters for stability [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stable MD Simulations

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Stability Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS4 Force Field | Accurate parameterization for organic molecules and solvents | Solvent mixture property prediction [26] | High correlation with experiment (R² ≥ 0.84) for density and ΔHvap |

| ReaxFF Reactive Force Field | Describes bond formation and breaking in complex systems | Shock waves in high-energy materials; silicon oxide systems [24] | Enables stable simulation of chemical reactions |

| COMPASSIII Force Field | Parameterization for polymers and inorganic materials | Dental material polymerization simulations [27] | Accurate prediction of mechanical properties (elastic modulus, tensile strength) |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Reduced computational cost while maintaining accuracy | Ni-Mo alloys and complex metallic systems [24] | Enables simulation of larger systems for longer timescales |

| High-Throughput Screening Protocols | Systematic evaluation of formulation stability | 30,000+ solvent mixture formulations [26] | Identifies stable parameter sets before extensive simulation |

Experimental Protocol: Machine Learning-Enhanced Simulation

- Data Generation: Run high-throughput classical MD simulations to generate comprehensive datasets (e.g., 30,000+ solvent mixtures) [26].

- Model Training: Train machine learning models using formulation descriptor aggregation (FDA), formulation graph (FG), or Set2Set-based method (FDS2S) [26].

- Property Prediction: Use trained models to predict formulation properties and identify potentially unstable parameter combinations.

- Targeted Simulation: Run full MD simulations only on the most promising candidates identified by ML screening.

Maintaining simulation stability in molecular dynamics requires addressing challenges at multiple levels, from force field selection and system setup to computational resource management. Recent advances from 2024-2025 literature demonstrate that integrating machine learning approaches with traditional MD simulations offers the most promising path forward for enhancing stability while maintaining accuracy. The methodologies and troubleshooting guides presented here provide researchers with practical approaches to overcome common instability issues, leveraging the latest developments in force fields, simulation protocols, and computational tools.

By implementing these evidence-based strategies from recent high-impact literature, researchers can significantly improve simulation success rates across diverse applications including drug development, materials science, metallurgy, and complex chemical formulations.

Building Robust Simulation Workflows: Method Selection and Implementation Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why do my MLFF simulations crash, even when energy and force errors on the test set are low? Simulation crashes often occur due to a reality gap: a model might perform well on standard computational benchmarks but fail when confronted with the complexity of real-world conditions or long simulation times. This can happen if the model encounters atomic configurations far outside its training data distribution. Crashes may manifest as atoms flying apart or unphysically large forces, making the equations of motion impossible to integrate [29] [30] [31].

2. Are traditional force fields more stable than machine learning force fields? Yes, traditional force fields are generally more numerically stable for well-parameterized systems. Their explicitly defined, simple functional forms and limited flexibility make them robust for dynamics within their intended domain of use. However, this stability can come at the cost of lower accuracy and poor transferability to new chemical environments. MLFFs, with their high capacity, can achieve quantum-level accuracy but are more prone to instability due to unphysical extrapolations on unseen data [32] [33].

3. What are the most common sources of instability in MLFFs? The primary sources are:

- Data Fidelity and Distribution Shift: Models trained on limited data, or data that doesn't represent the conditions of the simulation (e.g., only crystalline structures used to simulate surfaces), are likely to fail [30] [33].

- DFT Inaccuracies: MLFFs inherit systematic errors from their underlying Density Functional Theory (DFT) training data, which can lead to deviations in properties like lattice parameters and elastic constants, ultimately affecting simulation stability [34].

- Under-constrained Training: A model trained only on a handful of quantum calculations may be under-constrained, meaning it can learn multiple potential energy surfaces that all fit the training data but behave differently during dynamics [34].

4. How can I improve the stability of my MLFF without collecting expensive new quantum data? Several advanced training strategies can enhance stability:

- Fused Data Learning: Incorporate experimental data (e.g., lattice parameters, elastic constants) alongside quantum data during training. This adds physical constraints, helping the model correct for DFT inaccuracies and produce more stable and realistic simulations [34].

- Stability-Aware Training: Use frameworks like StABlE Training, which run MD simulations during the training process to identify and correct unstable trajectories. This provides a powerful supervisory signal that goes beyond single-point energies and forces [31].

- Multi-Fidelity Frameworks: Leverage a mix of abundant low-fidelity data (e.g., from fast DFT functionals) and scarce high-fidelity data (e.g., from high-level quantum methods or experiments) to build a more robust and data-efficient model [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Crashes Due to Unphysically Large Forces

Diagnosis: This is a common failure mode for MLFFs. It indicates that the model is producing an incorrect potential energy surface for the sampled atomic configurations.

Solution: A Step-by-Step Protocol

- Verify with a Short Simulation: Run a short, preliminary MD simulation and monitor the maximum force on any atom. A sudden, large spike is a clear warning sign.

- Analyze the Training Data:

Implement a Fused Data Learning Strategy:

- Objective: Re-train the model to concurrently reproduce both DFT data and key experimental observables.

- Protocol: a. Select target experimental properties relevant to stability (e.g., elastic constants, lattice parameters) [34]. b. Use a differentiable simulation framework (e.g., DiffTRe) to compute gradients of the loss function with respect to the model parameters, based on the difference between simulated and experimental properties [34]. c. Alternate training between standard DFT data (energies, forces) and the experimental data loss. This iterative process fuses the two information sources into a single, more robust model [34].

- Expected Outcome: The refined model should show improved agreement with the target experiments and increased simulation stability, as inaccuracies from the DFT functional are corrected [34].

Apply Stability-Aware Boltzmann Estimator (StABlE) Training:

- Objective: Directly penalize unstable dynamics during the training process without needing additional quantum calculations [31].

- Protocol: a. Run Parallel Simulations: During training, iteratively run many short MD simulations in parallel using the current model. b. Identify Instability: These simulations will naturally seek out unstable regions of the potential energy surface. c. Compute Observable Loss: Calculate a loss based on a reference observable (e.g., radial distribution function, density) from a reliable source (like a prior stable simulation or a short ab initio MD trajectory). d. Backpropagate and Correct: Use a differentiable Boltzmann Estimator to backpropagate the observable loss through the simulation and update the model parameters, directly teaching the model to avoid unstable configurations [31].

- Expected Outcome: Significant improvements in simulation stability and data efficiency, enabling longer time steps and more reliable estimation of thermodynamic observables [31].

Problem: Model Fails to Generalize to Systems with Different Dimensionality

Diagnosis: Universal MLFFs often perform well on 3D bulk crystals but show degraded accuracy for molecules (0D), nanowires (1D), or surfaces (2D). This can cause instability when simulating interfaces [36].

Solution:

- Strategy: Ensure the training dataset includes adequate representation of all relevant dimensionalities. If using a pre-trained universal potential, fine-tune it on a smaller, system-specific dataset that includes low-dimensional structures [36].

- Validation: Benchmark the model's performance on a dedicated multi-dimensional test set before deploying it for production simulations of complex interfaces [36].

Stability and Performance Data

Table 1: MD Simulation Stability of Universal MLFFs on Diverse Mineral Structures. This table summarizes the performance of different models when pushed to their limits on complex, real-world systems, highlighting the stability trade-off [30].

| Model Name | Simulation Completion Rate (MinX-EQ) | Simulation Completion Rate (MinX-HTP) | Simulation Completion Rate (MinX-POcc) | Primary Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orb | 100% | 100% | 100% | High robustness across all tested conditions. |

| MatterSim | 100% | 100% | 100% | High robustness across all tested conditions. |

| MACE | ~95% | ~95% | ~75% | Performance degrades with compositional disorder. |

| SevenNet | ~95% | ~95% | ~75% | Performance degrades with compositional disorder. |

| CHGNet | <15% | <15% | <15% | High failure rate; unphysically large forces. |

| M3GNet | <15% | <15% | <15% | High failure rate; unphysically large forces. |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Advanced Training on MLFF Stability and Accuracy. This table shows how modern training methodologies can directly address and mitigate common instability issues [34] [31].

| Training Strategy | Reported Improvement | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Data Learning (DFT & EXP) | Corrects DFT inaccuracies in lattice parameters and elastic constants; improves overall force field accuracy [34]. | Fuses high-fidelity simulation data with experimental reality to create better-constrained models. |

| Stability-Aware (StABlE) Training | Significant gains in simulation stability and agreement with reference observables; allows for larger MD timesteps [31]. | Uses differentiable MD to penalize unstable trajectories and incorrect thermodynamic observables during training. |

| Multi-Fidelity Framework (MF-MLFF) | Up to 40% reduction in force MAE; high-fidelity data requirements reduced by a factor of five [35]. | Leverages cheap, abundant low-fidelity data to learn general features, calibrated by scarce high-fidelity data. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for diagnosing and correcting MLFF simulation instability. Two advanced strategies, Fused Data Learning and Stability-Aware Training, provide pathways to a more robust model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for MLFF Development and Troubleshooting

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in MLFF Research |

|---|---|---|

| DiffTRe | Algorithm / Method | Enables gradient-based training of MLFFs against experimental or simulation observables, crucial for fused data learning [34]. |

| StABlE Training | Training Framework | Provides a end-to-end differentiable method to incorporate stability and observable-based supervision directly into MLFF training [31]. |

| UniFFBench / MinX | Benchmarking Framework | Offers a comprehensive dataset and protocol for evaluating MLFFs against experimental measurements, helping to identify the "reality gap" [30]. |

| DP-GEN | Active Learning Platform | Automates the process of generating training data and building MLFFs by iteratively discovering and labeling new, relevant configurations [37]. |

| PolyArena / PolyData | Benchmark & Dataset | Provides experimentally measured polymer properties and accompanying quantum-chemical data for training and validating MLFFs on soft materials [32]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Best Practices

Q1: What is the most critical factor for a successful Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) according to recent benchmarks?

Recent large-scale benchmarks, such as the TEA Challenge 2023, conclude that the choice of MLFF architecture (e.g., MACE, SO3krates, sGDML) is becoming less critical. When a problem falls within a model's scope, simulation results show a weak dependency on the specific architecture used. The emphasis for a successful implementation should instead be placed on developing a complete, reliable, and representative training dataset. The quality and coverage of the training data are more decisive for simulation accuracy and stability than the choice of model itself [38] [39] [40].

Q2: For which types of physical interactions should I be especially cautious?

Long-range noncovalent interactions remain a significant challenge for all current MLFF models. Special caution is necessary when simulating physical systems where such interactions are prominent, such as molecule-surface interfaces. Ensuring your training data adequately represents these interactions is crucial [38] [41] [39].

Q3: Can I trust MLFF molecular dynamics (MD) simulations just based on low force/energy errors on a test set?

No. A low force/energy error on a standard test set is necessary but not sufficient to trust an MLFF for MD simulations. The TEA Challenge highlights that long MD simulations provide a more robust test of reliability. A model must not only reproduce energies and forces for single configurations but must also remain stable over time and correctly capture the system's thermodynamics and dynamics. It is critical to validate your model by comparing observables (e.g., radial distribution functions, Ramachandran plots) from MLFF-driven MD simulations against reference DFT calculations or experimental data [39].

Q4: What is a recommended strategy to improve the accuracy of an MLFF beyond using DFT data?

A fused data learning strategy has been demonstrated to yield highly accurate ML potentials. This involves training a single model to concurrently reproduce both ab initio data (e.g., DFT-calculated energies, forces, and virial stress) and experimental data (e.g., mechanical properties, lattice parameters). This approach can correct known inaccuracies of DFT functionals and result in a molecular model of higher overall accuracy compared to models trained on a single data source [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Simulation Instability and Crashes

Problem: MD simulations crash or become unstable, often with atoms flying apart or bonds breaking unrealistically.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or Non-Representative Training Data | Analyze if the simulation is exploring geometries far from those in the training set. Check for large, unexpected atomic forces during the MD run. | Expand the training dataset to better cover the relevant phase space. Use active learning (on-the-fly sampling) to automatically include new, relevant configurations during training [42] [39]. |

| Inadequate Treatment of Long-Range Interactions | Check if instability occurs in systems with charged components, interfaces, or large dipoles. | Be aware that this is a known limitation. Prioritize MLFF architectures that explicitly model long-range electrostatics and ensure your training data includes configurations where these forces are significant [38] [39]. |

| Distribution Shift in Configurations | Use clustering algorithms (e.g., on dihedral angles) to compare the conformational space sampled in your MD to the training data. | Retrain the model with a more diverse dataset that encompasses all relevant metastable states and transition pathways observed in reference simulations [39]. |

Failure to Reproduce Target Properties

Problem: The MLFF simulation is stable, but the calculated observables (e.g., lattice parameters, elastic constants, free energy surfaces) do not match reference DFT or experimental values.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying DFT Inaccuracies | Compare your DFT-calculated properties against higher-level theory or experimental data. | Employ a fused data learning approach. Use the DiffTRe method or similar to fine-tune a pre-trained (on DFT) ML potential against experimental observables, thereby correcting for DFT's inherent inaccuracies [34]. |

| Poor Generalization to Target Property | The model may be accurate on forces but not on the specific property you are measuring, which is an ensemble average. | Incorporate the target experimental properties directly into the training loop alongside the DFT data. This ensures the model is optimized to reproduce these specific observables [34]. |

| Incorrect Simulation Setup | Verify that your simulation settings (ensemble, thermostat, barostat) match those used to generate the reference data. | Consult best practices guides for MD simulations. Ensure that for surface or molecule calculations, stresses are not trained (set ML_WTSIF to a very small value) as the vacuum layer does not exert stress onto the cell [42]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Fused Data Learning Workflow

This protocol outlines the methodology for training an MLFF using both DFT data and experimental observables, as demonstrated for titanium [34].

DFT Pre-training:

- Data Generation: Perform DFT calculations on a diverse set of atomic configurations (e.g., equilibrated, strained, randomly perturbed structures, high-temperature MD snapshots). The database should include energies, forces, and virial stress.

- Initial Training: Train an MLFF (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) using a standard regression loss function to match the DFT-calculated energies, forces, and virials.

Experimental Data Integration:

- Target Selection: Identify key experimental properties to match (e.g., temperature-dependent elastic constants, lattice parameters).

- EXP Trainer Loop: Use an iterative process to fine-tune the pre-trained MLFF:

- Run MD simulations with the current MLFF to compute the target observables.

- Calculate the loss between the simulated and experimental observables.

- Use a method like Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) to compute the gradients of this loss with respect to the MLFF parameters, avoiding the need for backpropagation through the entire MD trajectory.

- Update the MLFF parameters to minimize the loss.

Alternating Training: Alternate between the DFT trainer (to maintain agreement with quantum mechanics) and the EXP trainer (to match experiment) for one epoch each until convergence. Early stopping should be used to select the final model.

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

MLFF Stability Assessment Protocol

This protocol describes the procedure used in the TEA Challenge to evaluate the robustness of MLFFs in production MD simulations [39].

- System Preparation: Select the target system (e.g., a polypeptide, a molecule-surface interface, a perovskite material). Define the initial coordinates and simulation box.

- Simulation Setup:

- Ensemble: Prefer the NpT ensemble (ISIF=3) for training, as cell fluctuations improve robustness. For surfaces or molecules, use NVT (ISIF=2) and do not train stresses.

- Thermostat: Use a stochastic thermostat (e.g., Langevin) for good phase space sampling.

- Time Step: Set POTIM appropriately (e.g., ≤1.5 fs for oxygen-containing compounds, ≤0.7 fs with hydrogen).

- Initialization: Heat the system gradually from a low temperature to about 30% above the target application temperature to explore phase space.

- Production Run: Launch multiple independent, long-term (e.g., 1 ns) MD simulations from the same starting structure using different, independently trained MLFFs.

- Stability Check: Monitor simulations for catastrophic failures, such as broken bonds or system disintegration.

- Observable Analysis: For stable trajectories, compute relevant statistical observables:

- For biomolecules: Generate Ramachandran plots and analyze populations of metastable states using clustering algorithms.

- For materials/interface: Calculate radial distribution functions, lattice parameters, or diffusion coefficients.

- Validation: Compare the MLFF-derived observables against a reference ab initio MD trajectory or experimental data. Consistency across different MLFF architectures increases confidence in the result.

Key Research Reagents: MLFF Architectures and Tools

The table below summarizes the MLFF architectures and key computational tools discussed in the benchmark studies.

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE [39] | Equivariant Message-Passing GNN | Molecular & Materials Simulations | Uses spherical harmonics and radial distributions. Showed excellent mutual agreement in peptide simulations. |

| SO3krates [39] | Equivariant Message-Passing GNN | Molecular & Materials Simulations | Employs an equivariant attention mechanism to enhance model efficiency. |

| sGDML [39] | Kernel-Based ML Model | Molecular Simulations | Uses a global descriptor, well-suited for molecules in gas phase. |

| FCHL19* [39] | Kernel-Based ML Model | Molecular & Materials Simulations | Based on local atom-centered representations. |

| SOAP/GAP [39] | Kernel-Based ML Model | Molecular & Materials Simulations | The Gaussian Approximation Potential; a pioneering kernel-based MLFF. |

| VASP [42] | Software Package | Ab-initio DFT & MLFF Training | Contains integrated methods for constructing and applying MLFFs using ab-initio data. |

| DiffTRe [34] | Algorithm / Method | Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting | Enables training MLFFs directly on experimental observables without backpropagating through the MD trajectory. |

| CGnets [43] | Deep Learning Framework | Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics | Learns coarse-grained free energy functions from atomistic data, capturing emergent multibody terms. |

MLFF Stability Assessment Workflow

This workflow outlines the steps to systematically assess the stability and accuracy of a trained MLFF, as practiced in rigorous benchmarks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the maximum time step I can use without causing my simulation to become unstable? The maximum stable time step depends on your system's highest frequency vibrations. For typical systems:

- 2 femtoseconds (fs) is a standard and safe choice for most biomolecular simulations in explicit solvent [44].

- 5 fs can be sufficient for many metallic systems [45].

- 1-2 fs is necessary for systems with light atoms (e.g., hydrogen) or strong bonds (e.g., carbon) [45]. Using too large a time step will cause a dramatic energy increase and simulation failure.

FAQ 2: My simulation energy is increasing uncontrollably. What are the primary causes? A rapid increase in total energy, often called the simulation "blowing up," is most commonly caused by [45]:

- An excessively large time step.

- Incorrect constraints, leading to unrealistic forces.

- Overlapping atoms or steric clashes in the initial structure.

FAQ 3: How does the choice of thermostat impact the physical accuracy of my ensemble? Thermostats differ in how they control temperature and thus sample the canonical (NVT) ensemble:

- Stochastic thermostats (e.g., Langevin) correctly sample the ensemble but introduce random forces [45].

- Deterministic thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) preserve the dynamics but can cause temperature oscillations if not properly tuned [45].

- Velocity rescaling thermostats (e.g., Berendsen) efficiently relax the temperature to the target value but suppress energy fluctuations, leading to an incorrect ensemble [45].

FAQ 4: When should I use constraint algorithms like SHAKE or LINCS? Constraint algorithms are essential for [46]:

- Removing fast vibrations from bonds involving hydrogen atoms, which allows for a larger time step.

- Maintaining rigid molecules or specific molecular geometries during the simulation.

- Performing constrained optimizations, where certain parameters (e.g., a bond length or dihedral angle) are fixed during energy minimization [47].

FAQ 5: Why is the temperature in my NVT simulation fluctuating around the target value? Is this an error? No, this is expected behavior. In a correct NVT ensemble simulation, the instantaneous temperature fluctuates around the set point because the system constantly exchanges energy with the "thermal bath" modeled by the thermostat. The total energy, however, will fluctuate in an NVT simulation [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Simulation Instability and Crash on Startup

Problem: The simulation fails within the first few steps, often with an error related to coordinate updating or a "singular matrix."

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Time step too large | Check the log file for a sudden jump in potential energy. | Reduce the time step to 1 or 2 fs, especially if your system contains light atoms or strong bonds [45]. |

| Initial steric clashes | Visualize the initial structure; check for overlapping atoms. | Perform a careful energy minimization before starting the dynamics. |

| Incorrect system setup | Verify the topology and parameters for missing atoms or bonds. | Ensure all force field parameters are correctly assigned to your molecule. |

Issue 2: Incorrect Temperature or Energy Drift

Problem: The simulated system's temperature is consistently too high/low, or the total energy shows a steady drift over time in an NVE simulation.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor thermostat coupling | Check the temperature time course; it may be unstable or slow to converge. | For the Berendsen thermostat, adjust the coupling time constant tau. For Nosé-Hoover, use a thermostat chain [45]. |

| Insufficient equilibration | The system may not have reached equilibrium before production. | Extend the equilibration period until energy and temperature stabilize. |

| Energy drift in NVE | A small, linear energy drift can be normal. A large drift may indicate issues. | Ensure the pair list is updated frequently enough or its buffer size is increased to prevent missed interactions [46]. |

Issue 3: Constraints are Not Satisfied

Problem: Bond lengths or angles that should be constrained are changing during the simulation.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Constraint algorithm failure | Check the simulation log for warnings about constraint convergence. | Increase the number of iterations for the constraint algorithm (e.g., lincs-order in GROMACS, Shake Iterations in AMS [48]). |

| Over-constrained system | The system may be numerically rigid, causing instability. | For angle constraints near 0° or 180°, split the constraint using a dummy atom, analogous to a Z-matrix approach [47]. |

| Algorithm not applied | Verify that constraints are correctly defined in the input. | Ensure the constraint algorithm is activated in the molecular dynamics parameters. |

Parameter Selection Reference Tables

Table 1: Recommended Time Steps for Different System Types

| System Type | Recommended Time Step (fs) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| All-atom, explicit solvent | 2 | Standard for systems with flexible bonds [44]. |

| Metallic systems | 5 | Good choice for systems without high-frequency bonds [45]. |

| Systems with light atoms (H) | 1 - 2 | Necessary to capture fast hydrogen vibrations [45]. |

| Coarse-grained models | 20 - 40 | Softer potentials and fewer degrees of freedom allow for larger steps. |

Table 2: Comparison of Thermostat Algorithms

| Thermostat Type | Algorithm Examples | Pros | Cons | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic | Langevin [45] | Simple, correct ensemble. | Stochastic forces alter dynamics. | Systems in implicit solvent; stochastic dynamics. |

| Deterministic | Nosé-Hoover (Chain) [45] | Deterministic, correct ensemble. | Can cause periodic temperature oscillations. | Accurate NVT sampling where dynamics are secondary. |

| Velocity Rescaling | Berendsen, Bussi [45] | Fast, robust temperature control. | Does not generate a correct NVT ensemble (Berendsen). | Rapid equilibration (Berendsen). Correct NVT sampling (Bussi). |

Table 3: Common Constraints and Their Applications

| Constraint Type | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| FixAtoms [49] | Freezes selected atoms completely. | Holding a protein backbone fixed during ligand docking. |

| FixBondLength [49] | Fixes the distance between two atoms. | Keeping a key bond length constant during a reaction study. |