Molecular Dynamics Trajectory Quality Assessment: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive article explores current methodologies and best practices for assessing the quality of molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories, a critical challenge in computational biophysics and drug development.

Molecular Dynamics Trajectory Quality Assessment: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive article explores current methodologies and best practices for assessing the quality of molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories, a critical challenge in computational biophysics and drug development. As MD simulations become increasingly integral to understanding biological processes at atomic resolution, robust quality evaluation protocols are essential for ensuring reliable results. We examine foundational concepts of trajectory analysis, advanced methodological frameworks like the Quality Evaluation Based Simulation Selection (QEBSS) protocol, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and rigorous validation approaches comparing force fields and algorithms. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances from 2025 research to provide practical guidance for implementing effective trajectory quality assessment in biomedical applications, from protein dynamics studies to drug solubility prediction.

The Fundamentals of MD Trajectory Quality: Understanding Core Metrics and Their Biophysical Significance

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool in structural biology, biophysics, and drug discovery, enabling researchers to investigate the dynamic evolution of biomolecular systems with exceptional detail [1]. The technique models physical system motions by solving dynamical equations of motion based on parameterized force fields, generating trajectories that depict conformational sampling over time [2]. However, the value of these simulations hinges on their quality and reliability, necessitating robust assessment methodologies. Within the broader context of molecular dynamics trajectory quality assessment research, this guide objectively compares the essential metrics used to evaluate simulation performance: Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of Gyration (Rg), and energy conservation principles. These quantitative measures provide complementary insights into different aspects of trajectory quality, from global structural stability to local residue flexibility and system thermodynamics.

Core Quality Metrics Comparison

Definition and Applications of Key Metrics

MD simulations generate enormous amounts of trajectory data, and specific metrics have been standardized to evaluate different aspects of structural dynamics and simulation quality.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): This fundamental metric calculates the average distance between atoms of a protein or protein complex relative to a reference structure, typically the initial frame. RMSD primarily assesses structural stability, convergence of the simulation system, and the status of conformational changes over time [3]. It provides a global measure of how much the structure deviates from its starting configuration or other reference states.

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): This residue-specific metric quantifies the average fluctuation of each residue relative to its mean position throughout the simulation trajectory. RMSF is particularly valuable for identifying flexible and rigid regions within a protein, illuminating domains with significant dynamic behavior that may be crucial for biological function [3].

Radius of Gyration (Rg): Rg measures the mean distance of atoms from the center of mass of a protein, providing insights into its overall compactness and folding state. Low Rg values depict a more compact structure (folded state), while high Rg values depict an expanded structure (unfolded state) [3]. This metric is especially useful for studying folding/unfolding processes and conformational compaction.

Energy Conservation: In microcanonical (NVE) ensemble simulations, the principle of energy conservation requires that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant over time. Monitoring the fluctuation of total energy provides a critical check on the stability and physical validity of the simulation, with significant energy drift indicating potential problems with the integration algorithm, force field parameters, or simulation setup.

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Essential MD Quality Metrics

| Metric | Structural Level | Primary Application | Interpretation Guidelines | Computational Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | Global | Structural stability and convergence [3] | Low values indicate stable simulation; significant jumps may indicate conformational changes [4] | Backbone or Cα atoms typically used to eliminate noise from side chain motions |

| RMSF | Local (per-residue) | Flexibility and dynamics of residues [3] | High values indicate flexible regions; low values indicate rigid structural elements [5] | Cα atoms commonly analyzed to identify functionally important flexible regions |

| Rg | Global | Compactness and folding state [3] | Low values = compact/folded; high values = expanded/unfolded [3] | All atoms or backbone atoms to assess overall structural compaction |

| Energy Conservation | System-level | Physical validity and numerical stability [2] | Stable total energy = physically realistic; energy drift = potential integration problems | Total energy of the system monitored throughout production simulation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard MD Simulation Workflow

The assessment of quality metrics follows a standardized MD workflow that ensures proper system preparation, equilibration, and production phases:

System Preparation: The protein structure is obtained from experimental sources (Protein Data Bank) or computational modeling approaches such as AlphaFold2, Robetta-RoseTTAFold, or homology modeling [4] [6]. The structure is solvated in a water box (typically TIP3P water model) with ions added to neutralize the system and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [7].

Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization using algorithms like steepest descent until the maximum force is below a specified threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/(mol·nm)) to remove steric clashes and bad contacts [7].

Equilibration: The minimized system undergoes equilibration in two phases:

- NVT equilibration (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for 100 ps to stabilize the temperature at the target value (typically 310 K for biological systems) using thermostats like Berendsen [7].

- NPT equilibration (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for 100 ps to stabilize the pressure at 1.0 bar using barostats like Parrinello-Rahman [7].

Production Simulation: The equilibrated system proceeds to production MD simulation for data collection, typically ranging from 100 ns to 1 μs depending on the system size and research question. Trajectories are saved at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps) for subsequent analysis [7] [8].

Trajectory Analysis: The saved trajectories are analyzed using tools like GROMACS, VMD, or ProProtein to calculate quality metrics including RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and energy conservation [1].

Metric Calculation Protocols

Table 2: Detailed Methodologies for Calculating Essential Quality Metrics

| Metric | Calculation Method | Technical Parameters | Software Implementation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | RMSD = √(1/N × Σᵢ[(xᵢ - xᵢref)² + (yᵢ - yᵢref)² + (zᵢ - zᵢref)²]) where N is the number of atoms, (x,y,z) are coordinates, and (xref,yref,zref) are reference coordinates [2] | Typically calculated after rotational and translational fitting to reference structure; often using backbone or Cα atoms | GROMACS (gmx rms), VMD, ProProtein [1] |

||

| RMSF | RMSFᵢ = √(⟨(rᵢ - ⟨rᵢ⟩)²⟩) where rᵢ is the position of atom i, and ⟨⟩ denotes time average [2] | Calculated for each residue; requires prior fitting to remove global translation/rotation | GROMACS (gmx rmsf), ProProtein platform [1] |

||

| Rg | Rg = √(1/M × Σᵢ mᵢ(rᵢ - rcm)²) where M is total mass, mᵢ is mass of atom i, rᵢ is position, and rcm is center of mass [3] | Can be calculated for all atoms or specific subsets; often reported for backbone atoms | GROMACS (gmx gyrate), VMD |

||

| Energy Conservation | ΔE_total = | Etotal(t) - ⟨Etotal⟩ | / σE where Etotal is total energy, ⟨⟩ denotes average, and σ_E is standard deviation | Monitored throughout simulation; particularly critical for NVE ensembles | GROMACS (gmx energy), NAMD |

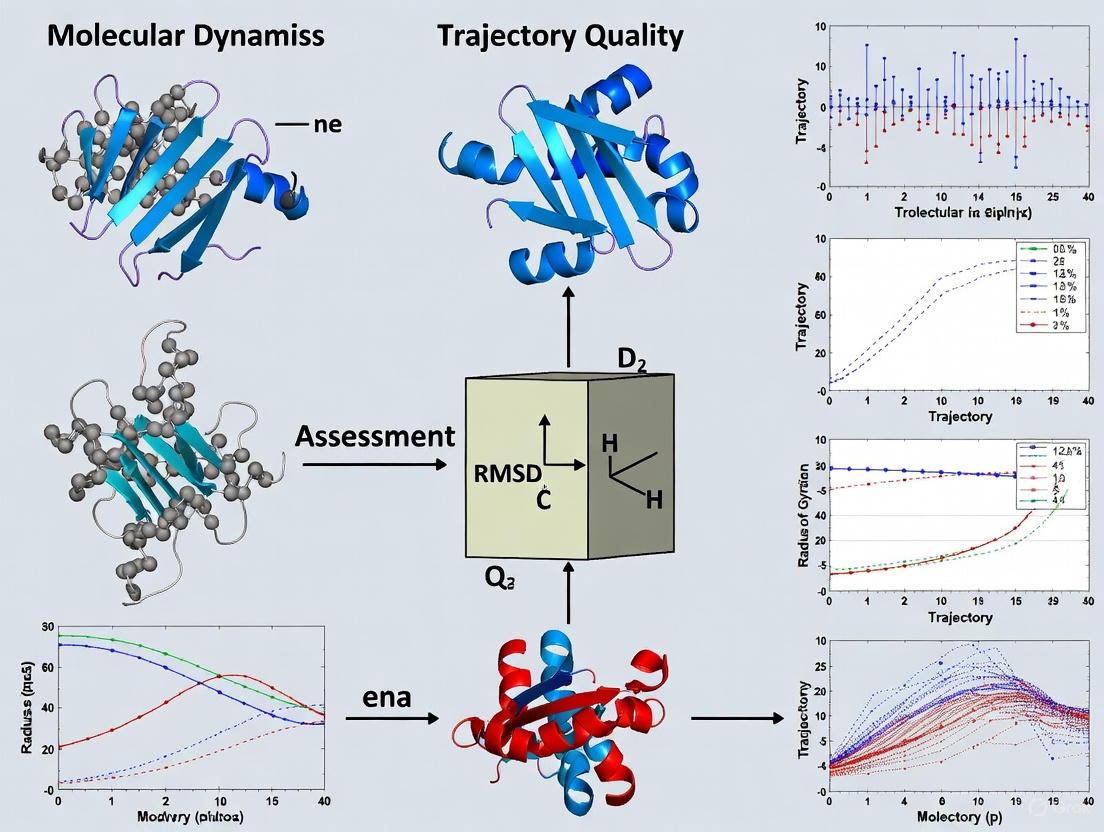

Figure 1: MD workflow and quality assessment metrics relationship. The diagram illustrates the standard molecular dynamics simulation workflow and its connection to the essential quality metrics used for trajectory validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools and Computational Resources for MD Quality Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software Suite | High-performance molecular dynamics simulations [7] [8] | Calculation of RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and energy monitoring through built-in analysis tools |

| ProProtein | Web Platform | Automated identification of 3D structure fluctuations in MD trajectories [1] | Visualization of high-fluctuation regions and trajectory quality assessment |

| CHARMM36 | Force Field | Parameterization of molecular interactions [7] | Provides physical basis for realistic simulation dynamics and energy conservation |

| AMBER99-SB-ILDN | Force Field | Alternative parameterization for biomolecular simulations [2] | Ensures accurate energy calculations and structural dynamics |

| GROMOS 54a7 | Force Field | Unified atom force field for MD simulations [8] | Parameterization for consistent energy conservation and structural properties |

| Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) | Visualization Software | Trajectory visualization and analysis [7] | Visual quality assessment and metric calculation through plugins |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Modeling Software | Homology modeling and structure preparation [4] | Initial structure preparation and template-based modeling for simulation input |

The comprehensive assessment of molecular dynamics simulation quality requires the integrated application of multiple complementary metrics. RMSD provides essential information about global structural stability, RMSF reveals local flexibility patterns critical for functional mechanisms, Rg quantifies overall compactness and folding state, and energy conservation validates the physical realism of the simulation. Current research indicates that these metrics should not be considered in isolation but rather as an interconnected framework for trajectory validation [3] [2]. As MD simulations continue to advance in temporal and spatial complexity, with studies now routinely reaching microsecond timescales and investigating larger biomolecular assemblies [1], the rigorous application of these quality metrics becomes increasingly crucial for distinguishing physically meaningful results from computational artifacts. The development of automated platforms like ProProtein [1] represents the growing recognition that standardized, accessible quality assessment is fundamental to the continued advancement of molecular dynamics as a predictive tool in structural biology and drug discovery.

Spin relaxation measurements, specifically of the parameters T1 (longitudinal relaxation time), T2 (transverse relaxation time), and heteronuclear Nuclear Overhauser Effect (hetNOE), provide indispensable experimental windows into molecular dynamics at atomic resolution. These NMR parameters are sensitive to molecular motions because nuclear spin relaxation is mediated by fluctuating local magnetic fields caused by both the overall tumbling and internal movements of molecules [9]. For protein studies, backbone 15N relaxation serves as a primary experimental probe, reporting on dynamics across an extraordinary range of timescales from picoseconds to milliseconds [10]. The connection between these measurable parameters and underlying molecular motions is encoded in the spectral density function, J(ω), which describes the distribution of motional frequencies within the molecule [9] [11].

The interpretation of T1, T2, and hetNOE data enables researchers to characterize both the global rotational diffusion of biomolecules and site-specific internal flexibility, information crucial for understanding how structural dynamics relate to biological function. This guide systematically compares the predominant analytical frameworks used to extract motional information from relaxation data, assessing their theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and respective strengths in connecting NMR measurements to molecular dynamics.

Theoretical Foundations: From NMR Parameters to Molecular Motions

Fundamental Relationships

The core theoretical framework connects experimentally measured relaxation parameters (T1, T2, hetNOE) to the spectral density function through mathematical relationships where:

- R1 (=1/T1) depends primarily on spectral density components at high frequencies [J(ωH + ωN), J(ωN), J(ωH - ωN)] [9]

- R2 (=1/T2) has additional dependence on J(0), making it sensitive to slower motions [9] [11]

- hetNOE reports on high-frequency motions [J(ωH + ωN), J(ωH - ωN)] and reflects fast ps-ns timescale dynamics [9]

These relationships are quantitatively expressed by the following equations [9]:

R1 = (1/4) * (μ₀²γN²γH²ħ²)/(4π²rNH⁶) * [J(ωH - ωN) + 3J(ωN) + 6J(ωH + ωN)] + c²J(ω_N)

R2 = (1/8) * (μ₀²γN²γH²ħ²)/(4π²rNH⁶) * [J(ωH - ωN) + 3J(ωN) + 6J(ωH + ωN) + 4J(0) + 6J(ωH)] + (c²/6)[4J(0) + 3J(ωN)] + R_ex

Key Molecular Motions Accessible via NMR Relaxation

Table: Characteristic NMR relaxation signatures of different molecular motions

| Motion Type | Timescale | T1 Signature | T2 Signature | hetNOE Signature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall tumbling | ns | Field-dependent decrease | Field-dependent decrease | High positive values (~0.8) |

| Fast internal motions | ps-ns | Moderate increase | Minimal change | Reduced values (0 to negative) |

| Conformational exchange | μs-ms | Minimal direct effect | Significant decrease (R_ex term) | Minimal direct effect |

| Anisotropic rotation | ns | Site-dependent variations | Site-dependent variations | Site-dependent variations |

Comparative Analysis of Methodological Frameworks

Model-Free Analysis (Lipari-Szabo Approach)

The Model-Free (Lipari-Szabo) approach represents the most widely employed method for interpreting protein backbone dynamics from NMR relaxation data. This framework assumes separability of internal and global motions and characterizes internal dynamics using two principal parameters: the generalized order parameter (S²), which quantifies the spatial restriction of internal motions (with values ranging from 1 for rigid sites to 0 for completely flexible sites), and the effective correlation time (τₑ), which describes the timescale of these internal motions [11]. The primary advantage of this approach lies in its ability to provide a simplified yet physically meaningful representation of complex dynamics without requiring detailed atomic-level knowledge of the motional mechanisms.

The extended Model-Free formalism introduces additional parameters to account for more complex motional regimes, including Sf² (fast limit order parameter) and τs (slow correlation time) to model motions occurring on distinct timescales [11]. However, this approach faces limitations in accurately representing physical autocorrelation functions that contain multiple exponential components within the monitored Larmor frequency window [11]. Studies have demonstrated that while the Model-Free approach can precisely fit experimental relaxation data, the resulting parameters may not always faithfully represent the underlying physical dynamics, particularly for highly mobile residues or systems with anisotropic global tumbling [11].

Anisotropic Tumbling Models

For molecules with pronounced elongated topology, such as θ-defensins which exhibit a length of approximately 30 Å with cross-sectional dimensions of about 10 × 10 Ų, the assumption of isotropic tumbling becomes inadequate [9]. In such cases, researchers must apply anisotropic rotational diffusion models that account for direction-dependent rotational diffusion coefficients (D∥ and D⊥) [9]. The θ-defensin HTD-2 represents a classic example where the strikingly elongated topology (with length-to-cross-section ratio of ~3:1) suggests potentially highly anisotropic overall motion approximating that of an axially symmetric cylinder [9].

Comparative studies indicate that while an isotropic model with internal motion can provide a satisfactory fit to experimental data for some systems, anisotropic models may be physically more appropriate for non-globular proteins [9]. The implementation of anisotropic models requires determination of the alignment tensor and consideration of the orientation of each N-H bond vector relative to the principal diffusion axes, adding complexity to the analysis but providing a more accurate representation of the global dynamics for asymmetric molecules [11].

Molecular Dynamics-Assisted Analysis

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an alternative approach for interpreting NMR relaxation data that offers atomic-level detail of the motional processes. Unlike model-free methods that parameterize dynamics, MD simulations explicitly model the physical trajectory of atomic movements, from which autocorrelation functions can be directly calculated [11]. Recent advancements have demonstrated the power of integrating MD simulations with NMR relaxation analysis to overcome limitations of simplified analytical models.

The Quality Evaluation Based Simulation Selection (QEBSS) protocol represents a systematic framework for selecting ensembles from MD simulation data that best reproduce experimental NMR relaxation parameters (15N T1, T2, and hetNOE) [12]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for characterizing conformational ensembles and dynamics of complex multi-domain proteins containing both folded and intrinsically disordered regions, such as calmodulin, CDNF, MANF, and EN2 [12]. Similarly, the development of optimized time constant-constrained triexponential (TCCT) representations has shown marked improvement over extended Lipari-Szabo formalisms in accurately back-predicting physical autocorrelation functions derived from MD simulations [11].

Table: Comparison of Methods for Interpreting NMR Relaxation Data

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Parameters | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Free (Lipari-Szabo) | Separability of internal and global motions | S², τₑ | Simple parameterization; Intuitive physical interpretation; Works well for globular proteins | May not represent physical autocorrelation functions accurately; Limited for anisotropic systems |

| Anisotropic Diffusion | Direction-dependent rotational diffusion | D∥, D⊥, diffusion tensor orientation | Physically appropriate for elongated molecules; Accounts for orientation-dependent relaxation | Increased complexity; Requires more experimental data |

| Molecular Dynamics Assistance | Atomic-level simulation of physical trajectory | Force field parameters, simulation conditions | Provides atomic detail; No presupposed motional model; Can reveal complex dynamics | Computationally intensive; Force field dependencies |

| QEBSS Protocol | Selection of MD ensembles matching experimental data | Quality metrics against T1, T2, hetNOE | Systematic ensemble selection; Handles multi-domain proteins with heterogeneous dynamics | Requires extensive simulation data; Computational resource demands |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Isotopic Labeling

The acquisition of high-quality NMR relaxation data requires specialized sample preparation, particularly for small cyclic peptides like θ-defensins. Traditional chemical synthesis approaches make isotopic labeling prohibitively expensive, but recent methodological advances have overcome this limitation. The semirecombinant protein splicing method enables cost-effective production of isotopically labeled cyclic peptides for NMR applications [9]. This protocol involves:

Recombinant Expression: A synthetic DNA sequence encoding the target peptide (e.g., HTD-2) with an N-terminal TEV protease recognition site and C-terminal modified intein is cloned into an expression vector (e.g., pTXB1) and transformed into bacterial expression systems (e.g., BL21(DE3) cells) [9].

Isotopic Labeling: Cells are grown in M9 minimal medium containing 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source to incorporate 15N labels into the peptide backbone [9].

Purification and Cyclization: The intein fusion protein is purified using chitin affinity chromatography, followed by simultaneous cyclization and folding through incubation with TEV protease and reduced glutathione [9].

Final Purification: The folded cyclic peptide is purified by reverse-phase HPLC, with purity and identity confirmed by analytical HPLC and mass spectrometry [9].

This method typically yields approximately 200 μg of 15N-labeled peptide per liter of bacterial culture, sufficient for comprehensive NMR relaxation studies [9].

Data Acquisition and Processing

Standardized protocols for acquiring 15N relaxation data involve collecting three complementary datasets at specific magnetic field strengths:

T1 Measurements: Using an inversion-recovery pulse sequence with multiple relaxation delays to monitor recovery of longitudinal magnetization.

T2 Measurements: Employing spin-echo (CPMG) sequences with variable delay periods to quantify transverse relaxation.

hetNOE Measurements: Acquiring spectra with and without 1H presaturation to determine steady-state 1H-15N Overhauser enhancements.

For dynamics occurring on microsecond-to-millisecond timescales, relaxation dispersion techniques (CPMG and R1ρ) provide additional characterization of conformational exchange processes and low-population excited states [10]. These methods are particularly valuable for capturing rare conformational fluctuations or binding events that escape detection in standard relaxation measurements.

Research Reagent Solutions for NMR Relaxation Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for NMR Relaxation Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 15N-labeled isotopes | Isotopic enrichment for NMR detection | 15NH4Cl (99% 15N purity) in M9 minimal media [9] |

| Expression vectors | Recombinant production of target peptides | pTXB1 plasmid with NdeI and SapI restriction sites [9] |

| Affinity chromatography media | Purification of fusion proteins | Chitin beads for intein fusion purification [9] |

| Proteases | Specific cleavage for peptide cyclization | TEV protease for recognition sequence cleavage [9] |

| Folding reagents | Promoting disulfide bond formation | Reduced glutathione in degassed phosphate buffer [9] |

| MD simulation software | Atomic-level dynamics modeling | NAMD2, AMBER16 with specific force fields [11] |

| Force fields | Physical parameterization for MD simulations | CHARMM27, CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB, ff14SB, ff15FB, ff15ipq [11] |

| Water models | Solvation environment for simulations | TIP3P, TIP3P-FB (for specific force fields) [11] |

Workflow Visualization

NMR Relaxation Data Interpretation Workflow

The interpretation of spin relaxation data (T1, T2, hetNOE) provides powerful insights into molecular motions across multiple timescales, connecting experimental NMR parameters to dynamic biological processes. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that the choice of analytical framework—whether Model-Free, anisotropic tumbling models, or MD-assisted approaches—significantly influences the extracted motional parameters and their physical interpretation. For globular proteins with approximately isotropic rotation, the Model-Free approach offers an efficient and intuitive framework, while elongated molecules like θ-defensins often require anisotropic treatment for physically meaningful analysis [9]. The emerging integration of molecular dynamics simulations with experimental relaxation data, exemplified by the QEBSS protocol and optimized TCCT representations, provides enhanced capability for characterizing complex conformational ensembles of multi-domain proteins and intrinsically disordered systems [12] [11]. This methodological evolution continues to refine our understanding of the fundamental relationship between molecular dynamics and biological function, with direct implications for drug design and therapeutic development.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational tool for characterizing the structural dynamics of biomolecules at atomic resolution. While significant progress has been made in developing force fields that accurately describe folded proteins, simulating intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or proteins containing both folded and disordered regions presents a unique challenge. Unlike folded proteins with well-defined tertiary structures, IDPs exist as heterogeneous structural ensembles, and their accurate simulation requires force fields that can simultaneously model both structured and unstructured states. This guide provides a systematic comparison of modern force fields, evaluating their ability to balance these competing demands using quantitative benchmarks from experimental and simulation studies.

Performance Comparison of Contemporary Force Fields

Quantitative Assessment of Force Field Accuracy

Systematic benchmarking studies have evaluated numerous force fields against extensive experimental datasets to determine their accuracy for both folded and disordered protein states. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of prominent force fields based on large-scale assessments.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Force Fields for Folded and Disordered Proteins

| Force Field | Water Model | Folded Proteins | Disordered Proteins | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a99SB-disp | TIP4P-D | Excellent agreement with NMR J couplings, RDCs, and order parameters [13] | Unprecedented accuracy for dimensions and secondary structure propensities [13] | Specifically optimized for both ordered and disordered states without trade-offs [13] | - |

| a99SB*-ILDN | TIP3P | Good accuracy for folded domains [13] | Produces overly compact disordered states [13] | Reliable for traditional folded protein simulations [13] | Poor performance for IDP dimensions and residual structure [13] |

| a03ws | Custom | Maintains folded state accuracy [13] | Improved over base versions but still limited [13] | Empirically optimized solute-solvent dispersion interactions [13] | Does not fully resolve compactness issue in IDPs [13] |

| C36m | TIP3P-CHARMM | Good for globular proteins [14] | Better dimensions than older versions but still overcompact [13] | Recent update improved small disordered peptides [13] | Does not solve overcompactness problem for larger IDPs [13] |

| C36m2021s3p | mTIP3P | Maintains structural integrity of folded domains [14] | Most balanced for R2-FUS-LC IDP region in benchmarking [14] | Computationally efficient; samples both compact and extended states [14] | - |

Specialized Benchmarking for Intrinsically Disordered Regions

Recent benchmarking focused specifically on the R2-FUS-LC region, an IDP implicated in ALS, provides additional insights into force field performance. The study evaluated 13 different force field and water model combinations using multiple metrics including radius of gyration (Rg), secondary structure propensity (SSP), and intra-peptide contact maps [14].

Table 2: Force Field Performance Scores for R2-FUS-LC IDP Region (Adapted from Scientific Reports, 2023)

| Force Field | Water Model | Rg Score | SSP Score | Contact Map Score | Final Score | Ranking Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c36m2021s3p | mTIP3P | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.58 | Top (*) |

| a99sb4pew | TIP4P-EW | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.47 | Top (*) |

| a19sbopc | OPC | 0.49 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.54 | Top (*) |

| c36ms3p | TIP3P | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.45 | Top (*) |

| a99sbdisp | CUFIX | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.37 | Middle (•) |

| a99sbnmd | TIP4P-NMD | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.33 | Middle (•) |

| a03ws | TIP4P-2005 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.22 | Bottom (#) |

| c27s3p | SPC | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.19 | Bottom (#) |

The scoring system assigned values from 0-1 for each metric, with the final score calculated by multiplying and rescaling the three normalized scores. Force fields were categorized into top ("*"), middle ("•"), and bottom ("#") ranking groups based on their overall performance [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Protocol for Balanced Force Field Assessment

The development and validation of balanced force fields follows rigorous experimental protocols:

1. Benchmark Set Composition: A diverse set of 21 experimentally well-characterized proteins and peptides was assembled, including folded proteins (ubiquitin, GB3, lysozyme, BPTI), fast-folding proteins (villin headpiece, Trp-cage), and disordered proteins (ACTR, drkN SH3, α-synuclein). This comprehensive benchmark encompasses over 9,000 experimental data points from techniques including NMR spectroscopy, SAXS, FRET, J-couplings, residual dipolar couplings, and chemical shifts [13].

2. Simulation Methodology: MD simulations are typically performed using production runs of 100ns to 1μs per system, with multiple replicates to ensure statistical significance. Simulations are conducted in explicit solvent under physiological conditions (150mM NaCl, 300K). The simulation workflow involves energy minimization, gradual heating, equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles, followed by production dynamics [13] [14].

3. Parameter Optimization Approach: For the development of a99SB-disp, researchers started with the a99SB-ILDN protein force field with TIP4P-D water model and iteratively optimized torsion parameters while introducing small changes in protein and water van der Waals interaction terms. Parameters were refined using a subset of the benchmark and validated against the remaining systems to prevent overfitting [13].

4. Evaluation Metrics: The primary metrics for assessment include:

- Radius of gyration (Rg): Measures global compactness of protein structures

- Secondary structure propensity (SSP): Quantifies residual structural elements

- Contact maps: Identifies native and non-native interactions

- Comparison with experimental data: Quantitative agreement with NMR parameters, SAXS profiles, and other experimental observables [13] [14]

Figure 1: Force Field Benchmarking and Development Workflow

Advanced Approaches: Integrating Machine Learning and Experimental Data

Recent advances incorporate machine learning (ML) and experimental data fusion to improve force field accuracy:

ML-Guided Force Field Selection: Machine learning analysis of MD trajectories can identify key properties influencing simulation accuracy. Studies have shown that properties including Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic interactions, Lennard-Jones (LJ) potentials, and solvation free energies are critical descriptors that correlate with force field performance [8].

Data Fusion Techniques: ML potentials can be trained using both Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and experimentally measured properties (mechanical properties, lattice parameters). This fused data learning strategy concurrently satisfies multiple target objectives, resulting in molecular models with higher accuracy compared to models trained with a single data source [15].

Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting: The DiffTRe method enables training of ML potentials on experimental data without backpropagating through entire trajectories. This approach allows force field parameters to be optimized to match experimental observables while maintaining physical plausibility [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Force Field Evaluation

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation package for running production dynamics [8] | Used with GROMOS 54a7 force field for solubility studies; provides efficient parallelization [8] |

| AMBER | Suite of biomolecular simulation programs with specialized force fields [13] | Includes a99SB-disp, a99SB*-ILDN variants; supports both folded and disordered proteins [13] |

| CHARMM | Molecular mechanics program with comprehensive force field options [14] | Implements C36m and C36m2021s3p force fields; compatible with mTIP3P water model [14] |

| TIP4P-D | Water model designed with balanced dispersion interactions [13] | Used with a99SB-ILDN as starting point for a99SB-disp development [13] |

| mTIP3P | Modified TIP3P water model with computational efficiency [14] | Combined with CHARMM36m2021 force field for IDP simulations [14] |

| NPT Ensemble | Constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature [8] | Standard for equilibrium MD simulations of biomolecules in aqueous solution [8] |

Practical Implementation Guidelines

Decision Framework for Force Field Selection

Figure 2: Force Field Selection Decision Framework

Best Practices for Simulation Protocols

System Preparation: Always begin with thorough energy minimization and gradual equilibration to prevent unrealistic starting conditions that can bias results.

Multiple Replicates: Conduct at least 3-5 independent simulations for each system to assess convergence and obtain statistically meaningful results, particularly important for disordered protein ensembles.

Simulation Length: For disordered proteins or folding studies, ensure simulations are sufficiently long to sample relevant conformational spaces. Typical production runs range from 100ns to 1μs depending on system size and scientific question.

Experimental Validation: Whenever possible, validate simulation results against available experimental data such as NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings, or SAXS profiles to confirm force field appropriateness for your specific system.

Water Model Compatibility: Always use water models specifically parameterized for your chosen force field, as force field and water model combinations are typically optimized together.

The development of force fields capable of accurately simulating both folded and disordered protein states represents a significant advancement in molecular dynamics methodology. Force fields such as a99SB-disp and C36m2021s3p have demonstrated remarkable ability to balance the competing requirements of structured and unstructured regions, broadening the range of biological systems amenable to MD simulation. Future directions include increased integration of machine learning methods, more sophisticated data fusion techniques combining simulation and experimental data, and continued refinement of parameters to address specific challenges such as amyloid formation and phase separation. As these tools evolve, they will further enhance our ability to model complex biological processes involving structural heterogeneity and dynamics.

In structural biology and drug development, the function of multidomain proteins is often governed by their dynamic nature, particularly the large-scale reorientations of their domains [16]. However, these conformational changes pose a significant challenge for computational methods, as sampling the vast conformational space adequately is non-trivial. The core of this challenge lies in the fact that multidomain proteins are "conformationally more flexible" than single-domain proteins, with reciprocal domain orientations that can vary significantly depending on the presence of binding partners [16]. Assessing whether a computational simulation has sufficiently explored this space—a concept known as sampling adequacy—is therefore paramount to generating reliable, biologically relevant data.

The critical importance of this assessment is underscored by a fundamental principle: simulation results are only as good as the statistical quality of the sampling [17]. Errors in simulation arise from both inaccuracies in the molecular models (force fields) and from insufficient sampling. Without adequate sampling, the true predictive power of even the most accurate force field remains unknown [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of modern methodologies for conformational space exploration, focusing on their application to multidomain proteins and the protocols for evaluating the completeness of the sampling they achieve.

A range of computational methods has been developed to tackle the sampling problem, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of several prominent approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Sampling Protein Conformational Space

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Underlying Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Atomic Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Conventional MD | Numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion with an atomic-level force field. | Provides high-resolution, time-resolved dynamics with explicit atomic details [18]. | Computationally expensive; often falls short of sampling cooperative events at microsecond+ scales for large systems [18]. |

| Enhanced Sampling MD | Replica Exchange, Meta-dynamics | Accelerates exploration by overcoming energy barriers via elevated temperature or bias potentials. | More efficient exploration of free energy landscape and rare events. | Parameter selection can be complex; statistical analysis requires care [19]. |

| Coarse-Grained & Analytical Models | Elastic Network Models (ENM), Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) | Represents protein as a simplified mechanics-based model to solve for collective motions. | Computationally efficient; identifies large-scale, cooperative motions mathematically [18]. | Lacks atomic details and anharmonicity [18]. |

| Hybrid Simulation Methods | MDeNM, CoMD, ClustENM, ClustENMD | Combines the efficiency of ENM/NMA with the detail of MD to guide exploration [18]. | Computationally efficient while retaining atomic resolution; good for large cooperative changes [18]. | Performance depends on parameters and system; may require optimization [18]. |

| Generative AI Models | Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) [20] | Deep learning model trained on MD data to learn physical principles of motion and generate novel conformations. | Extremely rapid generation of new, thermodynamically stable conformations, bypassing MD's kinetic barriers [20]. | Dependent on the quality and breadth of the training data; a "black box" nature can complicate interpretation. |

Quantifying Uncertainty and Sampling Quality

Once a simulation is complete, rigorous analysis is required to quantify the uncertainty of the results and assess the quality of the sampling. The International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM) provides standardized definitions for key statistical terms essential for this process [19].

- Arithmetic Mean ((\bar{x})): The estimate of the true expectation value of an observable, calculated from (n) observations as (\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n}\sum{j=1}^{n}xj) [19].

- Experimental Standard Deviation ((s(x))): The estimate of the true standard deviation of a random quantity, which measures the spread of the observations. It is calculated as (s(x) = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{j=1}^{n}(x{j} - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}}) [19].

- Standard Uncertainty: The uncertainty in a result expressed as a standard deviation. For the mean, this is the experimental standard deviation of the mean, given by (s(\bar{x}) = s(x)/\sqrt{n}) [19]. This quantity is colloquially known as the "standard error."

- Correlation Time ((\tau)): The longest separation in time for which a measurable correlation exists in a time-series of an observable. This is critical because successive frames in an MD trajectory are not statistically independent. A fundamental concept is the effective sample size, which is the total simulation time divided by the correlation time. As a rule of thumb, any average estimate based on fewer than ~20 statistically independent samples should be considered unreliable, as the uncertainty of the uncertainty estimate itself becomes large [17].

Table 2: Key Metrics and Tools for Assessing Sampling and Model Quality

| Assessment Category | Specific Metric / Tool | Description and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Quality | Ramachandran Plot | Assesses the stereochemical quality of a protein structure by visualizing backbone dihedral angles [6]. |

| Structural Quality | VADAR | Analyzes multiple structural parameters including volume, packing, and solvent accessibility [6]. |

| Convergence & Dynamics | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) / Essential Dynamics (ED) | Identifies the large-amplitude, collective motions in a trajectory by diagonalizing the covariance matrix of atomic coordinates [21]. |

| Convergence & Dynamics | Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | Measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures, used to track structural stability over time. |

| Convergence & Dynamics | JEDi Toolkit | A comprehensive software for PCA and essential dynamics analysis, offering multiple statistical models and visualization tools [21]. |

| Statistical Sampling | Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) & Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Statistic | Quantifies how well each degree of freedom has been sampled across the trajectory [21]. |

| Statistical Sampling | Effective Sample Size | The number of statistically independent configurations in a simulation, crucial for reliable uncertainty estimates [17]. |

Best Practices and Experimental Protocols for Assessment

A Workflow for Robust Sampling Assessment

Adopting a tiered approach to modeling and analysis is considered a best practice [19]. Workflows should begin with feasibility calculations, followed by simulation, semi-quantitative checks for sampling adequacy, and finally, the estimation of observables and their uncertainties. This iterative process helps avoid wasteful computations and identifies potentially misleading results from poorly sampled simulations.

Protocol: Evaluating Conformational Ensembles with Experimental Data

A rigorous method for benchmarking computational predictions involves comparing them against an ensemble of experimental structures.

- Objective: To evaluate whether a computationally generated conformational ensemble matches the diversity and characteristics of experimentally resolved structures for the same protein.

- Method: This unbiased comparison uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project both the experimental structures and the computationally generated conformers into a common space defined by the principal components of structural change [18].

- Procedure:

- Collect Experimental Ensemble: Gather multiple experimentally determined structures (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or NMR) for a target protein, ensuring they represent different conformational states.

- Generate Computational Ensemble: Use the method under evaluation (e.g., hybrid MD, AI) to produce a diverse set of conformers.

- Perform Comparative PCA: Combine all experimental and computational structures. Perform PCA on the combined set or project the computational ensemble onto the PCs defined by the experimental set (or vice-versa).

- Analyze Overlap: Visually and quantitatively assess the overlap between the experimental and computational distributions in the low-dimensional PC space. A well-sampled simulation should encompass the experimental conformations and explore a similar region of space [18].

Protocol: Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for Essential Dynamics

PCA is a cornerstone technique for analyzing the collective motions sampled in a trajectory.

- Objective: To reduce the high-dimensionality of a molecular trajectory and extract the large-amplitude, functionally relevant "essential motions" [21].

- Method: The JEDi toolkit implements PCA on three different statistical models: the covariance matrix (Q), the correlation matrix (R), and the partial correlation matrix (P) [21].

- Procedure:

- Trajectory Alignment: Align all frames of the trajectory to a reference structure to remove global rotational and translational motions [21].

- Construct Data Matrix: Create a data matrix (A) where rows represent the 3N Cartesian coordinates of N atoms and columns represent the different trajectory frames, with the mean conformation subtracted.

- Calculate Covariance/Correlation Matrix: Compute the covariance matrix (Q = (AA^T)/(n-1)). For correlation-based analysis, compute the correlation matrix (R) or partial correlation matrix (P).

- Diagonalization: Diagonlize the matrix to obtain eigenvectors (principal components, or "modes") and eigenvalues. The eigenvectors define the directions of collective motion, and the eigenvalues indicate the mean square fluctuation along those directions.

- Projection and Analysis: Project the trajectory onto the top few principal components to visualize the free energy landscape and identify metastable states.

Figure 1: A simplified workflow for performing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on a molecular dynamics trajectory, as implemented in tools like JEDi [21].

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Conformational Sampling and Analysis

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| JEDi [21] | Trajectory Analysis | A comprehensive, user-friendly toolkit for performing Essential Dynamics (PCA) on molecular trajectories with multiple statistical models and visualization options. |

| ICoN [20] | Generative AI | A deep learning model that uses internal coordinates to rapidly generate novel, thermodynamically stable protein conformations. |

| ClustENM / ClustENMD [18] | Hybrid Sampling | Generates conformers by deformation along normal modes, followed by clustering and energy minimization (ClustENM) or short MD refinement (ClustENMD). |

| MDeNM [18] | Hybrid Sampling | A multi-replica MD method that enhances exploration by introducing velocities along combinations of low-frequency normal modes. |

| Bio3D [21] | Trajectory Analysis | An R package for the analysis of protein structure and trajectory data, including PCA. |

| ModeTask [21] | Trajectory Analysis | A tool for PCA and normal mode analysis, available as a command-line tool or PyMol plugin. |

The accurate computational characterization of multidomain proteins is fundamentally linked to the adequate sampling of their conformational landscape. As this guide has detailed, a suite of methods—from long-timescale MD and hybrid techniques to emerging generative AI models—provides researchers with powerful tools for this task. The critical step, however, is the rigorous, statistical assessment of sampling quality using the protocols and metrics outlined herein, such as effective sample size and comparison to experimental ensembles.

Future progress in the field will likely involve the increased integration of experimental data, such as NMR residual dipolar couplings and pseudocontact shifts [22], to validate and restrain computational explorations. Furthermore, the development of more automated and intelligent workflows that seamlessly integrate sampling and assessment will be crucial for making robust conformational analysis accessible to a broader community of researchers in structural biology and drug discovery.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations serve as "virtual molecular microscopes," providing atomistic details of protein dynamics that are often obscured from traditional biophysical techniques [23]. However, two fundamental limitations constrain their predictive capabilities: the sampling problem (requiring lengthy simulations to describe dynamical properties) and the accuracy problem (insufficient mathematical descriptions of physical and chemical forces) [23]. The most compelling measure of a force field's accuracy is its ability to recapitulate and predict experimental observables, yet challenges persist in validation since experimental data represent averages over space and time, potentially obscuring underlying distributions and timescales [23]. This creates significant ambiguity in quality assessment, as multiple conformational ensembles may produce averages consistent with experiment [23].

Methodological Framework: Benchmarking MD Performance

Experimental Design for Comparative Validation

To quantitatively assess MD performance, researchers conducted a systematic comparison utilizing four simulation packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) with three different protein force fields (AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, Levitt et al., and CHARMM36) applied to two globular proteins with distinct topologies: the Engrailed homeodomain (EnHD) and Ribonuclease H (RNase H) [23]. This experimental design enabled direct comparison of how different software/force field combinations reproduce diverse experimental data.

All simulations were performed under conditions consistent with experimental data collection: EnHD at neutral pH (7.0) at 298 K, and RNase H at acidic pH (5.5, histidine residues protonated) at 298 K [23]. Each simulation was conducted in triplicate for 200 nanoseconds using periodic boundary conditions and explicit water molecules with "best practice parameters" determined by recent literature from software developers [23]. This rigorous methodology ensured meaningful comparison across platforms while maintaining biological relevance.

Benchmarking as a Quality Improvement Process

Benchmarking in this context represents more than simple indicator comparison; it constitutes a comprehensive tool based on voluntary collaboration among several approaches to create competition and apply best practices [24]. The key feature of benchmarking is its integration within a participatory policy of continuous quality improvement (CQI) [24]. For MD simulations, this involves careful preparation, monitoring of relevant indicators, and cross-validation between computational and experimental approaches.

Workflow for MD Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for validating molecular dynamics simulations against experimental observables:

Comparative Performance Analysis of MD Software

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Platforms

The table below summarizes the comparative performance of four MD simulation packages in reproducing experimental observables for two model proteins:

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of MD Simulation Packages [23]

| Software Package | Force Field | Water Model | Room Temperature Performance (EnHD) | Room Temperature Performance (RNase H) | Thermal Unfolding (498K) Accuracy | Conformational Sampling Extent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | TIP4P-EW | Reproduced experimental observables well | Reproduced experimental observables well | Moderate deviations from experiment | Moderate sampling |

| GROMACS | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | Not specified | Reproduced experimental observables well | Reproduced experimental observables well | Some packages failed to unfold | Subtle differences in distributions |

| NAMD | CHARMM36 | Not specified | Reproduced experimental observables well | Reproduced experimental observables well | Results at odds with experiment | Subtle differences in distributions |

| ilmm | Levitt et al. | Not specified | Reproduced experimental observables well | Reproduced experimental observables well | Variable performance | Subtle differences in distributions |

Key Findings from Comparative Analysis

While all four MD packages reproduced experimental observables equally well overall at room temperature for both proteins, researchers identified subtle differences in underlying conformational distributions and the extent of conformational sampling obtained [23]. This divergence became more pronounced when examining larger amplitude motions, particularly during thermal unfolding processes simulated at 498 K [23].

Critical findings revealed that some packages failed to allow the protein to unfold at high temperature or provided results contradictory to experimental evidence [23]. This demonstrates that force fields alone cannot explain all deviations, with factors including water models, algorithms constraining motion, treatment of atomic interactions, and simulation ensemble significantly influencing outcomes [23].

Software Comparison Logic

The decision process for selecting and validating MD software packages follows this logical structure:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

System Preparation and Simulation Parameters

The validation study employed rigorous system preparation protocols. Initial coordinates for EnHD simulations came from the 2.1 Å resolution X-ray crystal structure (PDB ID: 1ENH), while RNase H coordinates came from a 1.48 Å resolution crystal structure (PDB ID: 2RN2) [23]. Researchers removed crystallographic solvent atoms and performed conventional MD simulations using best practice parameters as determined by recent literature from software developers [23].

Specific protocols varied by software. For AMBER simulations, researchers used the AMBER14 package with ff99SB-ILDN force field, solvating proteins with explicit TIP4P-EW waters in a periodic truncated octahedral box extending 10 Å beyond any protein atom [23]. Systems underwent minimization in three stages: solvent atoms only, solvent with protein restraints, then full system minimization [23].

Trajectory Analysis Framework

MD trajectories represent sequential snapshots of simulated molecular systems at specific time periods, containing atomic coordinates that require specialized processing to extract meaningful information [25]. Ideal analysis software must support visualization of trajectories (molecular animation), rapid processing of large data volumes, and diverse analysis options [25].

Analysis programs must handle enormous trajectory files through various approaches. Some copy entire trajectory files to memory, while others like TAMD (Trajectory Analyzer of Molecular Dynamics) use random access buffers to maintain performance with large files [25]. VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics) represents one of the most comprehensive systems, supporting visualization, analysis of biological systems, multiple file formats, and integration with NAMD [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The Scientist's Toolkit for MD Validation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions for MD Validation [23] [25]

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, ilmm, CHARMM | Numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion | Generating conformational ensembles for comparison with experiment |

| Force Fields | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, Levitt et al. | Mathematical description of potential energy surfaces | Determining accuracy of physical/chemical forces in simulations |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | VMD, TAMD, HyperChem | Processing trajectory files, calculating properties over time | Extracting experimental observables from raw coordinate data |

| Visualization Systems | VMD with OpenGL/DirectX support | Molecular animation and rendering | Qualitative assessment of conformational changes and dynamics |

| Experimental Data Sources | PDB structures, NMR data, chemical shift databases | Providing empirical constraints | Benchmarking target data for simulation validation |

The rigorous benchmarking of MD simulations against experimental observables reveals that while modern force fields and software packages show remarkable overall performance in reproducing experimental data at room temperature, significant challenges remain in simulating large conformational changes and thermal unfolding [23]. This validation approach underscores that force field improvements alone cannot solve all accuracy problems, with integration algorithms, water models, and simulation parameters playing crucial roles [23]. For researchers in drug development and protein science, these findings emphasize the importance of multi-software validation and experimental cross-checking when employing MD simulations for predictive modeling of molecular behavior. The continuous quality improvement cycle inherent in proper benchmarking methodology ensures that molecular dynamics will remain an indispensable tool in the structural biology and drug discovery pipeline.

Advanced Protocols and Practical Applications: QEBSS Framework and Automated Analysis Platforms

Characterizing the structural ensembles and dynamics of multidomain proteins, which contain both folded and intrinsically disordered regions, presents a significant challenge in structural biology. This comparison guide examines the Quality Evaluation Based Simulation Selection (QEBSS) protocol, a novel method that integrates molecular dynamics simulations with NMR validation to select the most realistic conformational ensembles. We objectively evaluate QEBSS against alternative computational approaches, providing supporting experimental data and implementation details. Within the broader context of molecular dynamics trajectory quality assessment research, QEBSS represents a systematic framework for quantifying simulation quality, addressing a critical need in the field for robust validation methodologies, especially for flexible protein systems with relevance to drug design and development.

Multidomain proteins containing both folded and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) play crucial roles in biological processes, yet characterizing their dynamic conformational ensembles remains technically challenging [26]. Traditional structural biology methods often fall short for these flexible systems because they require well-defined, static structures. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can model this flexibility but face limitations including force field inaccuracies and insufficient sampling [27]. The molecular dynamics trajectory quality assessment field has consequently sought robust protocols to evaluate and select the most physically realistic simulations.

The Quality Evaluation Based Simulation Selection (QEBSS) protocol, recently introduced in Communications Chemistry, addresses this need by providing a systematic approach for selecting conformational ensembles with the most realistic dynamics from multiple MD simulations [26]. This guide comprehensively examines QEBSS implementation, experimentally benchmarks its performance against alternative methods, and provides practical resources for researchers seeking to apply this protocol to multidomain protein systems.

QEBSS Workflow and Implementation

Core Principles and Methodology

QEBSS operates on the fundamental principle that molecular dynamics simulations should reproduce experimental observables to be considered physically realistic. The protocol specifically uses protein backbone 15N T1 and T2 spin relaxation times and heteronuclear NOE (hetNOE) values from NMR spectroscopy as validation metrics [26] [28]. These NMR parameters are sensitive to molecular motions across picosecond-to-microsecond timescales, making them ideal for probing the dynamics of flexible multidomain proteins [26].

The protocol selects simulation ensembles that simultaneously reproduce all experimental spin relaxation parameters (T1, T2, and hetNOE), as these provide complementary information about different dynamic timescales [26]. This multi-parameter validation is crucial for ensuring the selected ensembles capture realistic dynamics rather than artificially optimizing for a single observable.

Step-by-Step Protocol Implementation

- Initial Structure Preparation: Generate multiple starting structures for the target protein to ensure diverse conformational sampling.

- Diverse Simulation Execution: Run MD simulations using multiple force fields and different initial configurations. In the foundational study, researchers ran 1-microsecond MD simulations from five different starting structures using five different force fields (a99SB-ILDN, DESamber, a99SB-disp, aff03ws, a99SB-ws), producing 25 total simulations per protein [26].

- Calculation of NMR Observables: From each trajectory, calculate theoretical backbone 15N spin relaxation times (T1 and T2) and hetNOE values for comparison with experimental data.

- Quality Evaluation and Selection: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) averaged over residues between simulated and experimental T1, T2, and hetNOE values. Select simulation trajectories where RMSDs for all spin relaxation parameters deviate less than 50% from the best-performing simulation [26].

The following diagram illustrates the overall QEBSS workflow:

Experimental Comparison with Alternative Methods

Performance Benchmarking

QEBSS has been experimentally validated on multiple multidomain proteins with complex dynamics, including calmodulin, EN2, MANF, and CDNF [26]. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of QEBSS in selecting realistic conformational ensembles across these different protein systems:

Table 1: QEBSS Performance Across Multidomain Protein Systems

| Protein Target | Domain Architecture | Number of Simulations Selected by QEBSS | Key Biological Insights Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calmodulin | Two folded domains + flexible linker | 2 out of 25 | Calcium-dependent conformational sampling enabling binding to various targets [26] |

| CDNF | N-terminal domain + partially unfolded C-terminal domain | 13 out of 25 | Distinct domain functions for intra- and extracellular activities [26] |

| MANF | N-terminal domain + partially unfolded C-terminal domain | 3 out of 25 | Structural insights relevant to neuroprotective effects [26] |

| EN2 | Folded homeodomain + flexible linker + Pbx-binding domains | 2 out of 25 | DNA binding specificity and affinity mechanisms [26] |

| TonBCTD (Control) | Single folded domain | 9 out of 25 | Reference for folded protein behavior [26] |

Comparative Analysis with Other Ensemble Determination Methods

QEBSS occupies a distinct position in the landscape of molecular dynamics validation and ensemble determination methods. The following table compares its approach and capabilities with alternative methodologies:

Table 2: Method Comparison for Conformational Ensemble Determination

| Method | Approach | Experimental Validation | Handles Multi-domain Proteins | Force Field Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QEBSS | Selection of best MD ensembles from multiple simulations | NMR spin relaxation (T1, T2, hetNOE) | Yes (explicitly designed for) | Quantitative comparison of multiple force fields |

| HREMD | Enhanced sampling via replica exchange | SAXS/SANS and NMR chemical shifts | Limited demonstration | Requires a priori force field selection |

| Bayesian/MaxEnt | Reweighting of MD ensembles to match experiments | Various (SAXS, NMR, etc.) | Yes, but with ensemble degeneracy challenges | Dependent on initial simulation quality |

| Standard MD | Single simulation with one force field | Often only NMR chemical shifts | Often insufficient sampling | No built-in comparison mechanism |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between QEBSS and other major approaches in the field:

Technical Implementation Guide

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of QEBSS requires specific computational tools and parameters. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in the protocol:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for QEBSS Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function in QEBSS Protocol | Examples/Options |

|---|---|---|

| MD Force Fields | Generate physically realistic conformational ensembles | a99SB-ILDN, DESamber, a99SB-disp, aff03ws, a99SB-ws [26] |

| MD Simulation Software | Execute molecular dynamics trajectories | GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM (via drMD for accessibility) [29] |

| NMR Relaxation Calculators | Compute theoretical NMR parameters from trajectories | In-house scripts, MDTraj, NMR-specific analysis packages |

| Initial Structure Generator | Create diverse starting configurations for enhanced sampling | Molecular modeling software, experimental structures, conformational sampling tools |

| Quality Assessment Scripts | Calculate RMSD between simulated and experimental data | Python/MATLAB scripts for RMSD calculation and selection criteria application |

Force Field Performance Insights

A critical finding from QEBSS applications is that force field performance is system-dependent, with no single force field universally outperforming others across all protein systems [26]. For instance:

- a99SB-ILDN (optimized for folded proteins) performed well for the fully folded TonBCTD control and calmodulin, but predicted overly compact ensembles for CDNF, MANF, and EN2 compared to force fields optimized for disordered proteins [26].

- Disorder-optimized force fields (a99SB-disp, aff03ws, a99SB-ws) generally produced more realistic ensembles for proteins with significant intrinsically disordered regions [26].

- Sampling considerations: Differences between individual simulation replicas were often larger than differences between force field averages, highlighting the importance of using multiple starting configurations to achieve sufficient conformational sampling [26].

Discussion and Research Implications

Advantages and Limitations

The QEBSS protocol provides several key advantages for molecular dynamics trajectory quality assessment. It offers quantitative quality evaluation of simulations through direct comparison with experimental data, enables systematic force field assessment for specific protein systems, and facilitates identification of the most realistic conformational ensembles for biological interpretation [26]. The method is particularly valuable for drug design applications where understanding flexible multidomain protein dynamics can inform therapeutic development strategies [26] [30].

Current limitations include substantial computational resource requirements (multiple long simulations), and dependence on the availability of experimental NMR relaxation data for validation. Additionally, while QEBSS selects the best available ensembles from generated simulations, it cannot improve inherently poor force field performance.

Integration with Emerging Methodologies

QEBSS complements rather than replaces other ensemble determination methods. It could potentially be integrated with enhanced sampling approaches like HREMD to generate better initial simulation ensembles [27]. The quantitative quality metrics provided by QEBSS also make it valuable for machine learning force field development and validation [31].

The protocol's extension beyond multidomain proteins to intrinsically disordered proteins [32] demonstrates its general applicability for complex biomolecular systems. As force fields continue to improve, QEBSS provides a framework for objectively evaluating these advances and selecting optimal parameters for specific research applications.

QEBSS represents a significant advancement in molecular dynamics trajectory quality assessment, specifically addressing the challenge of characterizing flexible multidomain proteins. By providing a systematic protocol for selecting ensembles that best reproduce experimental NMR relaxation data, QEBSS enables more reliable interpretation of conformational dynamics in biologically important systems. The method's demonstrated applications to proteins with therapeutic relevance, including neurotrophic factors and DNA-binding proteins, highlight its potential impact on drug discovery and development. As computational structural biology continues to grapple with complex, dynamic biomolecular systems, protocols like QEBSS that integrate computational and experimental data through quantitative validation will become increasingly essential for generating physiologically meaningful insights.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation stands as a fundamental technique in structural biology and drug development, enabling researchers to observe the dynamic evolution of biomolecular systems over time. However, the value of these simulations is fully realized only through rigorous analysis of the resulting trajectories, particularly the identification of flexible regions that are crucial for understanding protein function and stability. The automated identification of high-fluctuation motifs within MD trajectories represents a significant advancement in quality assessment, moving beyond visual inspection to quantitative, reproducible metrics. This capability is especially valuable for evaluating the reliability of computationally predicted protein 3D structures, where dynamic properties can indicate potential structural weaknesses or functional regions.

The ProProtein platform emerges as a specialized solution to this analytical challenge, offering researchers an integrated workflow for running MD simulations and automatically identifying protein fragments characterized by significant structural instability. By implementing a dedicated heuristic algorithm that analyzes spatial neighborhoods throughout the trajectory, ProProtein provides insights into flexibility patterns that traditional analysis methods might overlook [33]. This capacity for pinpointing dynamic hotspots makes it particularly relevant for pharmaceutical researchers investigating allosteric sites, protein-ligand interactions, and conformational changes relevant to drug design.

ProProtein: Core Methodology and Technological Implementation

Architectural Framework and Workflow

ProProtein operates through a sophisticated multilayer architecture designed for both computational efficiency and user accessibility. The platform employs a React-based frontend compatible with web browsers and mobile devices, while the backend, implemented in TypeScript on the Express framework, manages the computationally intensive MD simulations through Gromacs [33]. This separation of concerns allows the system to handle resource-heavy calculations on server infrastructure while providing researchers with an intuitive interface for configuring experiments and visualizing results.

The analytical workflow follows four methodical stages:

- Structure Upload and Validation: Users provide a 3D protein structure in PDB format, which undergoes automatic validation where non-protein chains, ligands, and ions are discarded, and amino acids with missing atom coordinates are rejected.

- MD Simulation Execution: The platform runs molecular dynamics simulations using Gromacs with user-configurable parameters for force field, water model, simulation length, and saving frequency.

- High-Fluctuation Motif Identification: A dedicated heuristic algorithm analyzes the trajectory to identify 3D fragments with high instability.

- Visualization and Output: Results are presented through the Mol* viewer with high-fluctuation regions highlighted, and comprehensive output files are available for download [33].

This integrated approach eliminates the need for researchers to master multiple specialized tools or navigate complex data conversion pipelines, creating a streamlined analytical process from initial structure to final flexibility assessment.

Algorithmic Innovation: Spatial Neighborhood Fluctuation Analysis

The core innovation of ProProtein lies in its heuristic algorithm for identifying high-fluctuation motifs, which moves beyond traditional atomic fluctuation measures to analyze spatial neighborhoods throughout the trajectory. The algorithm implements a novel approach to structural flexibility quantification:

Spatial Neighborhood Construction: For each residue (Cα atom) in the target frame (typically the first frame), the algorithm constructs a sphere encompassing all atoms within a user-definable spatial proximity threshold (adjustable from 2 to 8 Å) [33].

Frame-to-Frame Deviation Calculation: Rather than comparing positions to a static reference, the algorithm calculates Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) scores for atoms within each spatial neighborhood between subsequent frames in the trajectory [33].

Dynamic Neighborhood Tracking: As the protein evolves throughout the simulation, the algorithm dynamically tracks the same spatial neighborhoods identified in the target frame, allowing consistent monitoring of local flexibility regions despite global conformational changes.

Motif Selection and Ranking: The algorithm ranks all spatial neighborhoods by their RMSD scores and selects a user-defined percentage of motifs with the highest fluctuation values for visualization and further analysis [33].

This spatial neighborhood approach differs fundamentally from traditional methods like Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) or time-based RMSF (tRMSF), which measure atomic fluctuations relative to mean positions across the trajectory. By focusing on frame-to-frame deviations of local structural environments, ProProtein captures nuances of flexibility that reflect the dynamic evolution of the protein structure in a more physiologically relevant manner.

Table 1: Key Parameters in ProProtein's High-Fluctuation Motif Identification Algorithm

| Parameter | Description | Default Range | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sphere Radius | Euclidean distance for defining spatial neighborhoods around residues | 2-8 Å | Larger radii include more atoms, capturing broader structural contexts |

| Motifs of Interest | Percentage of highest-fluctuation fragments selected | User-defined | Higher percentages identify more flexible regions, potentially including borderline cases |

| Simulation Length | Duration of MD simulation | Configurable | Longer simulations improve statistical significance but increase computation time |

| Saving Step | Frequency of trajectory frame storage | Configurable | Higher frequency captures more temporal detail but increases storage requirements |

Figure 1: ProProtein workflow for high-fluctuation motif identification, highlighting the specialized analysis engine that differentiates it from conventional MD tools.

Comparative Analysis of Motif Discovery Approaches

Performance Benchmarking Framework

Evaluating bioinformatics tools requires robust benchmarking frameworks that employ standardized datasets, multiple performance metrics, and comparisons against established alternatives. Comprehensive testing should include ROC curves, precision-recall metrics, and correlation coefficients to provide a complete picture of predictive accuracy [34]. Proper benchmarking avoids subjective assertions of performance in favor of quantitative measures that enable direct comparison between tools.

For MD trajectory analysis specifically, assessment typically involves running different platforms on the same protein structures and comparing the biological relevance of identified flexible regions, computational efficiency, and usability for domain scientists. The MoDEL database provides a valuable resource for benchmarking, containing over 1,700 trajectories of representative monomeric soluble structures from the PDB, simulated under near-physiological conditions [35]. This repository offers a standardized foundation for comparative evaluation of flexibility analysis tools.

ProProtein vs. Alternative Motif Discovery Platforms

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of ProProtein Against Alternative Motif Discovery Approaches

| Platform | Primary Methodology | Application Domain | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProProtein | Spatial neighborhood RMSD analysis in MD trajectories | Protein flexibility identification from MD simulations | Integrated workflow, specialized for flexibility analysis, anonymous access | Newer platform with less established track record |

| idMotif | Deep learning (ProtBert) with SHAP explanation | Protein sequence motif discovery | High accuracy in motif identification, interactive visualization | Requires pre-grouped sequences, different problem domain |

| MEME | Probabilistic (PWM) modeling | DNA/protein sequence motif discovery | Extensive validation, wide adoption | Not designed for 3D structural motifs |

| DREME | Word enumeration with Fisher's Exact test | DNA motif discovery | Rapid processing for short motifs | Limited to sequence-based patterns |

| Weeder | Suffix tree-based enumeration | DNA motif discovery | Efficient for planted motif problem | Specialized for specific motif types |

When compared to sequence-based motif discovery tools like MEME and DREME, ProProtein operates in a fundamentally different domain. While these established tools excel at identifying conserved patterns in linear amino acid or nucleotide sequences [36], ProProtein specializes in extracting dynamic motifs from three-dimensional structural trajectories. This distinction highlights how the definition of "motif" varies significantly across bioinformatics subfields, from conserved sequence patterns to flexible structural regions.