Molecular Markers in Population Genetics: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular marker technology and its critical role in deciphering population structure for researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Markers in Population Genetics: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular marker technology and its critical role in deciphering population structure for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of major marker types, including SNPs and SSRs, and explores advanced methodologies like whole-genome resequencing and SLAF-seq. The content addresses common analytical challenges, offers optimization strategies, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating current research and emerging trends such as quantum computing, this resource serves as a practical guide for selecting, applying, and validating molecular markers to advance genetic studies, drug discovery, and personalized medicine.

The Building Blocks of Genetic Analysis: Understanding Molecular Marker Types and Their Core Principles

A molecular marker, specifically a DNA marker, is a DNA sequence with a known physical location on a chromosome that serves as a landmark for genetic exploration [1]. Conceptually, these markers function much like geographical landmarks—just as the Washington Monument helps visitors navigate to the nearby White House, molecular markers help geneticists locate specific genes or chromosomal regions of interest [1]. The fundamental principle underlying their utility is that DNA segments close to each other on a chromosome tend to be inherited together, enabling researchers to track the inheritance of nearby genes that may not yet be identified [1]. Molecular markers represent genetic differences (polymorphisms) between individuals or species at the DNA level, arising from various mutation events including point mutations, insertions, deletions, duplications, translocations, and inversions [2].

These markers are characterized by two fundamental features: heritability and the ability to be distinguished [3]. Essentially, any genetic mutation leading to discernible differences can serve as a genetic marker, making them vital tools in genetic research and analysis [3]. Molecular markers are particularly powerful because they are not constrained by environmental factors, tissue types, developmental stages, or seasons, offering direct insight into genomic distinctions between biological individuals or populations [3]. This technical guide explores the classification, applications, and methodologies of molecular markers within the context of population structure research, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical experimental frameworks.

Classification and Evolution of Molecular Marker Systems

Molecular markers have evolved significantly since the 1980s, progressing through three major technological generations with increasing density, precision, and throughput [2] [3]. Each marker system offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research applications and resource availability scenarios.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major DNA Molecular Marker Technologies

| Marker Type | Genetic Characteristics | Throughput | Polymorphism Level | Technical Requirements | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism) | Co-dominant | Low | Moderate | Restriction enzymes, electrophoresis, hybridization | Genetic mapping, diversity studies [3] |

| RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA) | Dominant | Medium | High | Random primers, PCR | Diversity analysis, fingerprinting [3] |

| SSR (Simple Sequence Repeat) | Co-dominant | Medium | High | Sequence-specific primers, PCR | Population genetics, linkage mapping [3] |

| AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism) | Dominant/Co-dominant | High | High | Restriction enzymes, adapter ligation, PCR | Genetic diversity, cultivar identification [3] |

| SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) | Co-dominant | Very High | Very High | Sequencing, chip arrays | Genome-wide association studies, population genomics [3] |

The selection of an appropriate marker technology depends on multiple factors, including research objectives, anticipated genetic variation, sample size, availability of technical expertise and facilities, time constraints, and financial considerations [2]. No single marker system is ideal for all applications, requiring researchers to carefully match methodology to experimental goals [2].

First-Generation Markers: RFLP

As the first generation of molecular markers, RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism) detects variations in DNA fragments resulting from changes that affect restriction endonuclease recognition sites [3]. The technique involves digesting genomic DNA with restriction enzymes, separating fragments via electrophoresis, transferring them to a membrane, and hybridizing with labeled probes [3]. While RFLP markers are predominantly co-dominant and offer high reproducibility, they have largely been superseded by PCR-based methods due to their complex procedures, lengthy detection periods, high costs, and limited suitability for large-scale applications [3].

Second-Generation Markers: PCR-Based Systems

The development of PCR-based markers revolutionized molecular genetics by enabling rapid amplification of specific DNA regions. Key technologies in this category include:

- RAPD (Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA): Utilizes short, random primers (8-10 bp) to amplify genomic DNA [3]. While simple and rapid, RAPD markers are dominant and show limited reproducibility due to sensitivity to experimental conditions [3].

- SSR (Simple Sequence Repeat): Also known as microsatellites, SSRs consist of tandem repeats of 1-6 nucleotide units [3]. They are co-dominant, highly polymorphic, and offer excellent reproducibility, but require prior sequence knowledge for primer development [3].

- AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism): Combines restriction enzyme digestion with PCR amplification, enabling simultaneous detection of numerous fragments [3]. This technique offers both dominant and co-dominant markers without requiring prior sequence information, but demands high DNA quality [3].

Third-Generation Markers: SNPs and Beyond

SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) represent the current standard in molecular marker technology, capturing single nucleotide variations throughout the genome [3]. As the most abundant polymorphism type in genomes, SNPs offer high stability, co-dominant inheritance, and suitability for large-scale screening [3]. Advances in sequencing technologies have enabled massive SNP discovery, as demonstrated in recent studies identifying 33,121 high-quality SNPs in Lycium ruthenicum [4], 944,670 SNPs in peach germplasm [5], and 39 million SNPs in durian accessions [6]. The primary limitation of SNP markers has been the historically high cost of detection methods, though sequencing expenses have decreased substantially in recent years [3].

Molecular Markers in Population Structure Research: Current Applications

Molecular markers serve as indispensable tools for deciphering population structure, genetic diversity, and evolutionary relationships across diverse species. Recent studies demonstrate their powerful applications in both plant and animal genomics:

Plant Population Genomics

In Black goji (Lycium ruthenicum), researchers employed specific-locus amplified fragment sequencing (SLAF-seq) to develop 33,121 genome-wide SNP markers across 213 accessions [4]. Population genetic analysis revealed three distinct genetic clusters with less than 60% geographic origin consistency, indicating weakened isolation due to anthropogenic germplasm exchange [4]. The Qinghai Nuomuhong population exhibited the highest genetic diversity (Nei's index = 0.253; Shannon's index = 0.352), while low overall polymorphism (average PIC = 0.183) likely reflected SNP biallelic limitations and domestication bottlenecks [4].

Korean peach (Prunus persica) research utilized whole-genome sequencing to identify 944,670 high-confidence SNPs across 445 accessions [5]. Population structure analysis using fastSTRUCTURE, principal component analysis (PCA), and phylogenetic reconstruction revealed substantial genetic variation and complex population structure, enabling the establishment of a representative core collection capturing the majority of the species' genetic diversity [5].

A study of durian (Durio zibethinus) applied whole-genome resequencing of 114 accessions, identifying 39,266,608 high-quality SNPs [6]. Population structure analysis revealed three major genetic clusters, with populations POP1 and POP2 being more closely related while POP3 was more differentiated [6]. Genetic diversity metrics varied among populations (π = 0.0019 for POP1, 0.0016 for POP2, and 0.0012 for POP3), informing conservation strategies and breeding programs [6].

Animal Population Genomics

In Hetian sheep, whole-genome resequencing of 198 individuals identified 5,483,923 high-quality SNPs for population genetic analysis [7]. The population exhibited substantial genetic diversity with generally low inbreeding levels, and kinship analysis grouped 157 individuals into 16 families based on third-degree kinship relationships [7]. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified 11 candidate genes associated with litter size, demonstrating the application of molecular markers for linking genetic variation to economically important traits [7].

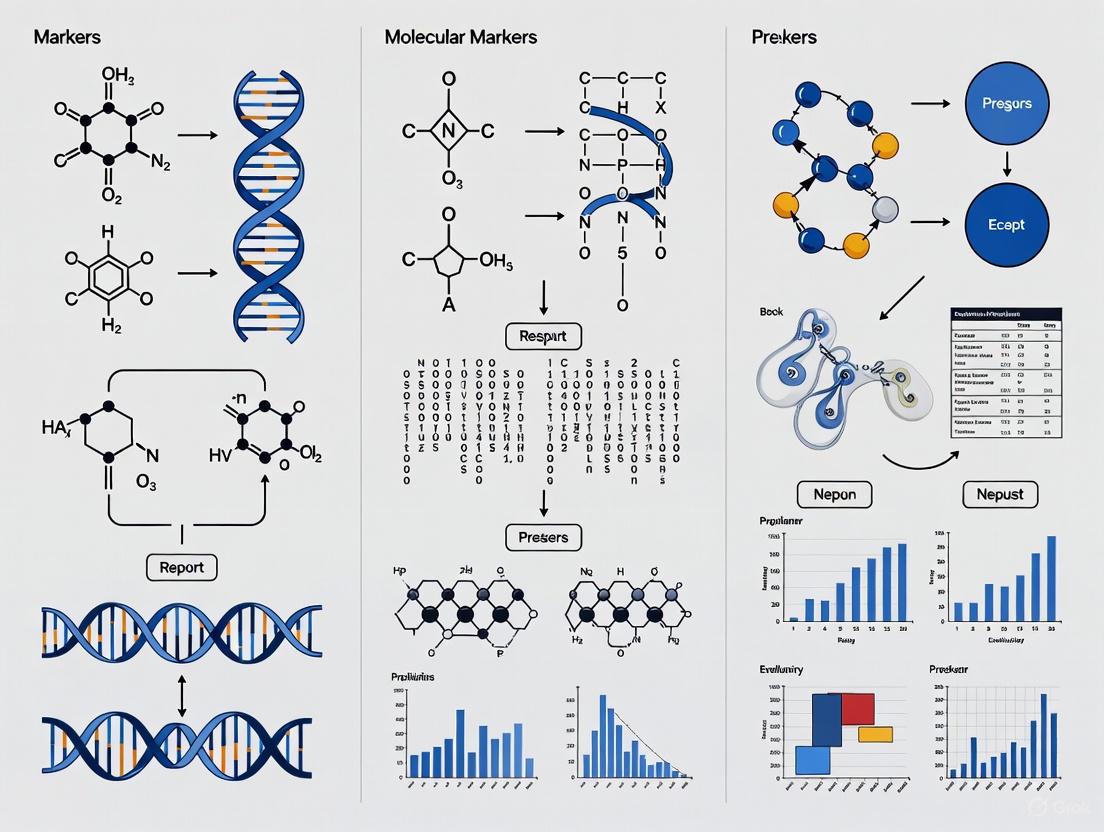

Diagram 1: Molecular Marker Research Workflow for Population Studies

Essential Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genomic DNA Extraction: CTAB Protocol

High-quality DNA is fundamental for successful molecular marker analysis. The CTAB (Cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide) method has been widely adopted across diverse taxa [4] [5] [7]:

- Tissue Homogenization: Grind 100 mg of fresh young leaf tissue or other source material in liquid nitrogen using a homogenizer at 1500 rpm for 40 seconds [4].

- Cell Lysis: Incubate ground tissue in preheated CTAB lysis buffer containing 2% β-mercaptoethanol at 65°C for 40-60 minutes [4].

- Purification: Remove protein contaminants through two rounds of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes [4].

- DNA Precipitation: Add isopropanol and 3M sodium acetate (10:1 v/v) and incubate at -20°C for 1 hour [4].

- Washing and Resuspension: Pellet DNA by centrifugation, wash with 75% ethanol, air-dry, and dissolve in RNase A-treated ddH₂O [4].

- Quality Assessment: Verify DNA integrity via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and assess purity using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0) [4] [5].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Molecular Marker Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Type | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTAB Lysis Buffer | CTAB, NaCl, EDTA, Tris-HCl, β-mercaptoethanol | Cell membrane disruption, DNA release | Plant genomic DNA extraction [4] [5] |

| Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol | 24:1 ratio | Protein removal and purification | DNA purification phase separation [4] |

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, MseI, etc. | Specific DNA sequence recognition and cleavage | AFLP, RFLP analysis [3] |

| PCR Reagents | Taq polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, primers | DNA fragment amplification | SSR, RAPD, SNP genotyping [3] |

| Agarose | Polysaccharide polymer | Matrix for electrophoretic separation | DNA fragment size separation [8] |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina NovaSeq, etc. | High-throughput DNA sequencing | WGS, SLAF-seq, SNP discovery [4] [5] |

High-Throughput Sequencing Approaches

Modern population genomics increasingly relies on reduced-representation or whole-genome sequencing approaches:

SLAF-seq (Specific-Locus Amplified Fragment Sequencing):

- Restriction Enzyme Selection: Perform in silico restriction enzyme prediction based on reference genome characteristics including size, GC content, and fragment distribution [4].

- Library Construction: Digest genomic DNA with selected restriction enzymes, A-tail fragments, ligate dual-index adapters, and PCR-amplify [4].

- Size Selection and Sequencing: Purify amplified products via agarose gel electrophoresis and sequence on Illumina platforms [4].

Whole-Genome Resequencing:

- Library Preparation: Fragment high-quality DNA and prepare libraries using kits such as TruSeq DNA Nano 550 bp Kit [5].

- Sequencing: Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 150 bp paired-end reads at minimum 30× coverage [5].

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using FastQC, remove adapter contamination and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic, and discard reads shorter than 36 bp [5].

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of molecular marker data involves multiple steps:

- Read Alignment: Map quality-filtered reads to reference genome using BWA-MEM v0.7.17 [4] [5] [7].

- Variant Calling: Identify SNPs using GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) with appropriate filtering parameters [4] [5] [7].

- Population Genetics Analysis:

- Genetic Diversity: Calculate nucleotide diversity (π), heterozygosity, and other diversity indices [6].

- Population Structure: Perform principal component analysis (PCA), ADMIXTURE analysis, and construct neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees [5] [7] [6].

- Linkage Disequilibrium: Measure non-random association of alleles across populations [7].

- Association Mapping: Implement genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using general linear models (GLM) or mixed linear models (MLM) to identify marker-trait associations [7].

Diagram 2: Bioinformatics Pipeline for Population Genomics

Molecular markers have revolutionized population genetics research, enabling precise characterization of genetic diversity, population structure, and evolutionary relationships. The transition from traditional markers like RFLP and RAPD to high-density SNP systems has dramatically increased resolution and throughput, facilitating genome-wide association studies and marker-assisted selection [2] [3]. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and costs decrease, the application of molecular markers will expand further, particularly for non-model organisms and underutilized crops [2].

The integration of molecular marker data with other omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) promises to provide more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between genetic variation and phenotypic expression [4] [7]. Furthermore, the development of standardized core collections based on molecular characterization, as demonstrated in peach and durian research [5] [6], will enhance germplasm conservation and utilization efficiency. For population structure research specifically, molecular markers serve not only as descriptive tools but as analytical instruments for deciphering evolutionary history, migration patterns, and adaptive processes across diverse species and ecosystems.

The study of population structure provides critical insights into evolutionary history, genetic diversity, and the distribution of traits within and across populations. Molecular markers serve as the fundamental toolkit for deciphering these complex genetic architectures, having evolved from basic fingerprinting techniques to sophisticated whole-genome scanning technologies. This evolution has transformed our capacity to characterize populations with unprecedented resolution, enabling applications ranging from conservation genetics to pharmaceutical development. The transition from Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLPs) to Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) represents a paradigm shift in analytical power, density, and throughput, each marker system offering distinct advantages and limitations for specific research contexts [9].

Understanding the technical properties, applications, and methodological requirements of each marker class is essential for designing robust population studies. Each system varies in its polymorphism rate, genomic distribution, technical requirements, and information content, making certain markers better suited for particular evolutionary timescales or population genetic questions. This review provides a comprehensive classification of marker technologies, places them within the context of population structure prediction, and offers detailed experimental frameworks for their application in modern genetic research. By tracing the development of these systems and their practical implementation, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to select optimal markers for their specific population genetics objectives.

Historical Progression and Technical Classification of Marker Systems

Molecular markers have progressed through distinct technological generations, each expanding our capacity to detect genetic variation. The following sections provide a detailed technical classification of the primary marker systems used in population genetics.

First-Generation Markers: RFLPs and the Dawn of DNA Fingerprinting

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLPs) represent one of the earliest forms of DNA-based markers and provided the foundation for molecular population genetics. The technique relies on detecting variations in DNA fragment lengths generated by restriction enzyme digestion, which reveal nucleotide sequence polymorphisms at specific recognition sites [10].

Experimental Protocol for RFLP Analysis:

- DNA Isolation: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from target samples using CTAB or phenol-chloroform methods.

- Restriction Digestion: Digest DNA (5-10 µg) with restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoRI, HindIII) recognizing 4-6 base pair sequences.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Separate digested fragments (0.8-1.0% agarose gel, 30-40V, 16-20 hours) by size.

- Southern Blotting: Transfer DNA from gel to nitrocellulose or nylon membrane via capillary action.

- Hybridization: Incubate membrane with labeled (radioactive or chemiluminescent) DNA probes complementary to target sequences.

- Detection: Visualize polymorphic fragments via autoradiography or imaging systems [10].

RFLPs are co-dominant markers, distinguishing heterozygotes from homozygotes, but their limited polymorphism, requirement for large DNA quantities, and reliance on radioisotopes restricted their scalability [9].

PCR-Based Markers: Microsatellites and Fragment Analysis

The invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) enabled a new class of markers characterized by higher polymorphism and reduced DNA requirements. Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs or microsatellites), consisting of tandemly repeated 1-6 base pair units, became the dominant marker system in the 1990s and early 2000s [9].

Experimental Protocol for SSR Analysis:

- Primer Design: Develop primers flanking microsatellite regions from genomic libraries or sequenced genomes.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify loci with fluorescently labeled primers in multiplex reactions.

- Fragment Analysis: Separate amplified products by size using capillary electrophoresis on automated sequencers.

- Genotype Scoring: Determine allele sizes using internal size standards and specialized software [11].

SSRs offered high polymorphism information content (PIC) and required minimal DNA, but developing species-specific primers was costly and cross-species transferability was often limited [9].

Modern Marker Systems: SNPs and High-Throughput Genotyping

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) represent single base-pair differences in DNA sequences and have become the marker of choice for contemporary population genomics. Their biallelic nature, genome-wide distribution, and compatibility with high-throughput automated platforms make them ideal for large-scale population studies [11] [7].

Experimental Protocol for SNP Discovery and Genotyping:

- Library Preparation: For reduced-representation approaches like SLAF-seq, digest genomic DNA with restriction enzymes, then ligate barcoded adapters for multiplexing [4].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence libraries on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq with PE150 configuration.

- Variant Calling: Map reads to a reference genome using BWA, then identify SNPs using GATK with quality filtering (Q30) [7].

- Genotype Validation: Confirm SNP associations using targeted platforms like Sequenom MassARRAY [7].

SNP arrays provide exceptional density and reproducibility, enabling genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and精细population structure analysis [11].

Figure 1: Historical progression of molecular marker technologies and their primary applications in genetic research.

Comparative Analysis of Marker Systems

The selection of appropriate molecular markers depends on multiple factors including the research question, available resources, and biological system. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of the major marker types used in population structure analysis.

Table 1: Technical comparison of major molecular marker systems for population genetics

| Parameter | RFLP | SSR/Microsatellites | SNP Arrays | Sequencing-Based SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism Nature | Co-dominant | Co-dominant | Co-dominant | Co-dominant |

| Genomic Distribution | Low-copy coding regions | Genome-wide, often non-coding | Genome-wide (predesigned) | Genome-wide (unbiased) |

| Level of Polymorphism | Low | High | Medium | High |

| Typical Number of Loci | 10-100 | 10-1000 | 1,000-1,000,000 | 10,000-10,000,000+ |

| Development Cost | Low | High | Medium | High |

| Analysis Cost Per Sample | High | Medium | Low | Medium-High |

| Throughput | Low | Medium | High | Very High |

| Automation Potential | Low | Medium | High | High |

| Information Content | Low | High | Medium | High |

| Reproducibility | Medium | Medium-High | High | High |

| Data Quality | Variable | High | High | Variable (depends on coverage) |

| Primary Applications in Population Structure | Early diversity studies, pedigree analysis | Fine-scale structure, kinship, conservation genetics | GWAS, genomic prediction, breed differentiation | Population genomics, demographic history, selection signatures |

Performance Metrics in Practical Applications

Quantitative comparisons demonstrate the enhanced power of SNP markers for population discrimination. In alfalfa, molecular markers provided substantially greater cultivar distinctness than morphophysiological traits. DArTag markers reduced non-distinct cultivar pairs from 39 to 11 in paired comparisons and increased completely distinct cultivars from 3 to 11, based on principal components analysis of allele frequencies [12]. Similarly, in rutabaga, 6,861 SNP markers successfully differentiated Icelandic accessions from other Nordic populations (P < 0.05), with Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, and Danish subpopulations showing 88.5-99.6% polymorphic loci compared to 67.9% in Icelandic subpopulations [11].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the standard analytical pipeline for population structure analysis using modern SNP data:

Figure 2: Standard analytical workflow for population structure analysis using SNP data, from sample collection to visualization and interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Successful population genetics research requires specific laboratory reagents, instrumentation, and bioinformatic tools. The following table details essential components of the molecular marker toolkit.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and platforms for molecular marker analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | CTAB method, Commercial kits | High-quality DNA isolation from diverse tissues | Rutabaga leaf tissue [11], Sheep blood [7], Chicken feathers [10] |

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, HindIII, MseI, Frequent cutters | DNA digestion for RFLP or reduced-representation libraries | SLAF-seq library preparation [4], RFLP analysis [10] |

| PCR Components | Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, primers, buffers | Amplification of target loci for SSR or candidate genes | Microsatellite amplification [9], SNP validation [7] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, HiSeq2500 | High-throughput DNA sequencing for SNP discovery | Whole-genome resequencing in sheep [7], SLAF-seq in Lycium ruthenicum [4] |

| Genotyping Arrays | Species-specific SNP chips | Multiplex SNP genotyping for population screens | Brassica 15K SNP array [11], Chicken 600K SNP array [10] |

| Variant Callers | GATK, Samtools, BCFtools | SNP identification from sequence data | Hetian sheep WGRS analysis [7], Lycium ruthenicum SNP discovery [4] |

| Population Genetics Software | STRUCTURE, ADMIXTURE, Arlequin, PLINK | Population structure, diversity, and differentiation analysis | Rutabaga population structure [11], Hetian sheep kinship [7] |

Case Studies in Population Structure Analysis

Crop Plants: Rutabaga Accessions from Nordic Countries

A comprehensive study of 124 rutabaga accessions from five Nordic countries utilized 6,861 SNP markers to investigate population structure. Results demonstrated that Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, and Danish accessions were not genetically distinct, suggesting extensive gene flow and shared genetic backgrounds. In contrast, Icelandic accessions formed a distinct genetic cluster, exhibiting significantly lower genetic diversity (67.9% polymorphic loci vs. 88.5-99.6% in other populations) [11]. This differentiation likely resulted from genetic drift and limited gene flow in the isolated Icelandic population. The study employed multiple analytical approaches including principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), UPGMA clustering, and Bayesian analysis with STRUCTURE software, demonstrating how complementary methods provide robust insights into population relationships.

Livestock Species: Hetian Sheep Population Genomics

Whole-genome resequencing of 198 Hetian sheep identified 5,483,923 high-quality SNPs used to decipher population structure and kinship dynamics. Analysis revealed substantial genetic diversity and generally low inbreeding levels within the population. Kinship analysis grouped 157 individuals into 16 families based on third-degree relationships (kinship coefficients 0.12-0.25), while 41 individuals showed no detectable relatedness, indicating substantial genetic independence [7]. This detailed understanding of population structure enabled a more powerful genome-wide association study that identified 11 candidate genes associated with litter size, demonstrating how population structure analysis serves as a critical foundation for trait mapping.

Conservation Genetics: Lycium ruthenicum in China

Population structure analysis of 213 Lycium ruthenicum accessions using SLAF-seq generated 33,121 high-quality SNPs uniformly distributed across 12 chromosomes. Genetic analyses revealed three distinct clusters with less than 60% consistency with geographic origin, indicating weakened isolation due to anthropogenic germplasm exchange [4]. The Qinghai Nuomuhong population exhibited the highest genetic diversity (Nei's index = 0.253; Shannon's index = 0.352), while low overall polymorphism (average PIC = 0.183) reflected both SNP biallelic limitations and domestication bottlenecks. Notably, SNP-based clustering showed less than 40% concordance with phenotypic trait clustering (31 traits), underscoring environmental plasticity as a key driver of morphological variation [4].

The progression from RFLPs to SNP markers has fundamentally transformed population genetics from a descriptive discipline to a predictive science. While RFLPs provided the initial framework for DNA-based diversity assessment, and SSRs offered enhanced resolution for fine-scale structure, SNPs have unlocked the potential for genome-wide analyses with unprecedented precision and throughput. Each marker system retains value for specific applications: RFLPs for retrospective analysis of historical data, SSRs for studies requiring high per-locus polymorphism, and SNPs for comprehensive genome-wide assessment.

The future of population structure research lies in the integration of marker technologies with functional genomics, gene expression data, and environmental variables. As sequencing costs continue to decline, whole-genome approaches will become standard, enabling not only neutral diversity assessment but also identification of adaptive variants under selection. This integrated framework will empower more precise predictions of population responses to environmental change, disease pressures, and conservation interventions, ultimately fulfilling the promise of molecular markers to bridge genomic variation with organismal fitness and evolutionary potential.

Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs), or microsatellites, represent one of the most versatile and informative classes of molecular markers in genetic research. Their distinctive characteristics—abundance throughout eukaryotic genomes, codominant inheritance patterns, and high degree of polymorphism—make them particularly valuable for predicting population structure. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of SSR biology, methodologies, and applications within population genetics. We synthesize current protocols for SSR marker development using next-generation sequencing, data analysis pipelines, and experimental validation procedures. Furthermore, we present quantitative analyses of SSR distribution across species and discuss how their codominant nature enables precise determination of population allelic frequencies. The integration of SSR markers into population structure prediction models offers researchers powerful tools for elucidating genetic diversity, gene flow patterns, and evolutionary relationships across diverse organisms.

Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs), also known as microsatellites or Short Tandem Repeats (STRs), are tandemly repeated DNA sequences with basic units of 1 to 6 nucleotides that are widely distributed throughout the genomes of most eukaryotes [13] [14]. These sequences mutate at rates between 10³ and 10⁶ per cell generation—up to 10 orders of magnitude greater than point mutations—primarily through polymerase strand-slippage during DNA replication or recombination errors [15]. This high mutational rate generates significant length polymorphisms across individuals, forming the basis of their application as genetic markers.

SSRs have transitioned from being considered "junk DNA" to being recognized as important elements with significant impacts on "gene activity, chromatin organization, and protein function" [14]. The flanking regions surrounding microsatellite loci are generally conserved, enabling the design of specific primers for PCR amplification across individuals and populations [14]. The resulting amplification products display length variations classified as simple sequence length polymorphisms (SSLPs), with each amplification site representing an equivalent allele [13].

Within population structure research, SSRs provide the critical advantage of being codominant markers, allowing researchers to distinguish between homozygous and heterozygous individuals within populations—a capability absent in dominant marker systems [13]. This characteristic, combined with their multi-allelic nature and high polymorphism, makes SSRs particularly suited for analyses requiring precise determination of allele frequencies, heterozygosity estimates, and population differentiation metrics [15].

Core Characteristics of SSRs

Genomic Abundance and Distribution

SSRs are ubiquitously distributed throughout eukaryotic genomes, though their distribution is highly non-random and varies across genomic regions and species [15]. Comprehensive analysis of 112 plant species revealed 249,822 SSRs from 3,951,919 genes, with trinucleotide repeats being the most common type across all taxonomic groups [16]. The density and abundance of SSRs make them ideal for constructing high-density genetic maps and conducting genome-wide association studies.

In a study of three Broussonetia species, SSR frequency showed positive correlation with chromosome length, with density measurements of 971.05, 921.76, and 806.55 SSRs per Mb in B. papyrifera, B. monoica, and B. kaempferi, respectively [14]. Similarly, analysis of the Camellia chekiangoleosa transcriptome identified 97,510 SSR loci from 65,215 unigene sequences, with a frequency of 74.03% and an average of one SSR every 1.93 kb [17]. These quantitative measures demonstrate the remarkable abundance of SSRs across plant genomes.

Table 1: SSR Distribution Characteristics Across Species

| Species | Total SSRs Identified | SSR Frequency | Density | Predominant Motif |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broussonetia papyrifera | 369,557 | 99.39% mapped to chromosomes | 971.05/Mb | 'A/T' for mononucleotides (98.67%) [14] |

| Camellia chekiangoleosa | 97,510 | 74.03% of sequences contained SSRs | 1/1.93 kb | Mononucleotide (51.29%) [17] |

| 112 Plant Species | 249,822 from 3,951,919 genes | Variable across species | N/A | Trinucleotide (64.14% average in eudicots) [16] |

| Broussonetia kaempferi | 276,245 | 99.81% mapped to chromosomes | 806.55/Mb | 'AT/AT' for dinucleotides (59.02-62.56%) [14] |

Codominant Inheritance

The codominant nature of SSR markers represents one of their most valuable attributes for population genetics research. Unlike dominant markers such as RAPDs or AFLPs, SSRs allow researchers to identify all alleles at a specific locus, distinguishing clearly between homozygous and heterozygous states in diploid organisms [13]. This capability is fundamental for accurate calculation of population genetic parameters including allele frequencies, observed and expected heterozygosity, and deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

The molecular basis for this codominance lies in the primer design strategy for SSR analysis. Primers are developed to target the conserved flanking regions surrounding the variable repeat motif, enabling specific amplification of the target locus [13]. As noted in technical documentation, "SSR markers enable the detection of allelic differences in heterozygotes, allowing for the discrimination between homozygous and heterozygous individuals, thereby providing investigators with more comprehensive genetic information" [13]. The resulting PCR products vary in length depending on the number of repeat units in different alleles, and these fragments can be separated by electrophoresis according to size differences, ultimately enabling the identification of distinct allelic variants [13].

High Polymorphism

The polymorphism of SSR markers primarily arises from variation in the number of tandem repeat units at a given locus, though nucleotide substitutions and unequal crossing-over events also contribute to diversity [13]. The mutation rate of microsatellites is substantially higher than that of other genomic regions, leading to the generation of numerous alleles within populations [15]. This polymorphism manifests as length differences that can be easily detected through electrophoretic separation.

Research has demonstrated that longer repeat sequences generally exhibit higher degrees of polymorphism. As noted in studies of SSR characteristics, "the longer and purer the repeat, the higher the mutation frequency, whereas shorter repeats with lower purity have a lower mutation frequency" [15]. This relationship between repeat length and variability has practical implications for marker selection in population studies, where highly polymorphic markers are often preferred for their ability to discriminate between closely related individuals.

In the study of Camellia chekiangoleosa, examination of different SSR repeat types revealed an inverse relationship between repeat unit length and degree of length variation, with mononucleotide repeats showing the highest variation and pentanucleotide repeats the lowest [17]. This detailed understanding of polymorphism patterns enables researchers to select appropriate marker types for specific applications.

Table 2: SSR Polymorphism Characteristics

| Characteristic | Impact on Polymorphism | Research Example |

|---|---|---|

| Repeat Length | Longer repeats generally show higher mutation rates | Camellia chekiangoleosa: mononucleotides showed highest length variation [17] |

| Motif Type | Dinucleotide and trinucleotide repeats often highly polymorphic | Barley EST-SSRs: 47 markers showed polymorphism useful for diversity analysis [18] |

| Genomic Location | UTR regions often contain more polymorphic SSRs | C. chekiangoleosa: Dinucleotide SSRs in UTRs produced more polymorphic markers [17] |

| Purity of Repeats | Perfect repeats without interruptions tend to be more polymorphic | Comparison of perfect vs. imperfect repeats shows different mutation potentials [15] |

SSR Development and Analysis Workflow

Marker Development Through Sequencing Technologies

Traditional methods for SSR marker development involved constructing genomic libraries and screening with hybridized probes, processes that were time-consuming and labor-intensive [19]. The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized this process, enabling rapid identification of thousands of potential SSR markers across entire genomes [19] [14].

The general workflow for SSR development through NGS begins with DNA library preparation and shotgun sequencing, typically using the Illumina platform [19]. The resulting sequences are then processed through bioinformatics toolsets such as MISA (MIcroSAtellite identification tool), SSR Finder, or Tandem Repeats Finder to identify potential microsatellite loci [13] [16]. Following identification, primers are designed for the flanking regions of candidate SSRs, synthesized, and tested on multiple individuals to assess amplification efficiency and polymorphism levels [19].

This NGS-based approach offers significant advantages over traditional methods, including massive data acquisition, comprehensive genomic coverage, automation potential, and reduced per-marker costs [19]. The development of full-length transcriptome sequencing (Iso-Seq) based on third-generation sequencing technology has further enhanced SSR marker development by providing more accurate gene models and enabling the development of functional SSR markers linked to expressed genes [17].

Genotyping and Data Analysis

The experimental process for SSR analysis begins with sample collection based on research objectives, followed by DNA extraction using standardized protocols such as the CTAB method or commercial kits [13]. PCR amplification is then performed using species-specific SSR primers, with careful optimization of annealing temperatures typically tested in a gradient from 50-65°C [13].

Fragment analysis represents a critical step in SSR genotyping, with two primary methods employed: polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis ("big board gel") with silver staining detection, or capillary electrophoresis using fluorescently labeled primers [13]. Capillary electrophoresis offers superior resolution (up to 0.1 bp) and higher throughput, making it preferable for large-scale population studies [13].

Data analysis utilizes specialized software tools for different aspects of population genetic investigation. For basic genetic diversity assessment, programs like Popgene and ARLEQUIN calculate parameters such as polymorphism information content (PIC), observed and expected heterozygosity, and F-statistics [18] [13]. For population structure analysis, software such as Structure employs Bayesian clustering algorithms to infer genetic populations and assign individuals to populations based on their SSR genotypes [13]. Additional tools like Tassel and SPAGeDi facilitate association analysis and spatial genetic structure examination [13].

Applications in Population Structure Research

Predicting Population Structure

SSR markers have become a cornerstone technology for elucidating population structure across diverse species. Their high polymorphism makes them particularly effective for discriminating between closely related populations and detecting fine-scale genetic patterns. In a study of 82 barley cultivars, EST-SSR markers successfully differentiated between naked, hulled, and malting barley types, revealing a polymorphism information content of 0.519, which indicated low genetic diversity among Korean barley cultivars [18]. This level of resolution enables researchers to identify distinct subpopulations and understand their genetic relationships.

The application of SSR markers in population structure analysis extends to wild species as well. Research on Camellia chekiangoleosa populations demonstrated that developed SSR markers "had higher levels of polymorphism" suitable for investigating genetic diversity within this species [17]. Similarly, studies of Broussonetia species utilized SSR markers to examine genetic relationships between three closely related species, providing insights for "further research on the origin, evolution, and migration of Broussonetia species" [14]. These applications highlight the value of SSRs in tracing historical migration patterns and understanding evolutionary processes.

Integration with Other Molecular Markers

While SSR markers provide powerful tools for population genetics, they are increasingly integrated with other marker systems to provide complementary insights. Next-generation sequencing technologies now allow for simultaneous discovery of SSRs and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the same dataset, enabling researchers to combine the high polymorphism of SSRs with the abundance and genomic distribution of SNPs [19]. This integrated approach provides a more comprehensive view of population structure and evolutionary history.

The development of expressed sequence tag SSRs (EST-SSRs) has further enhanced the application of microsatellites in functional population genomics. Unlike genomic SSRs, EST-SSRs are derived from transcribed regions and may be associated with functional genes, potentially linking population structure patterns with adaptive variation [18] [17]. As noted in barley research, EST-SSR markers can be used "for quantitative trait locus analysis to improve both the quantity and the quality of cultivated barley" [18], demonstrating the utility of these markers in connecting neutral and adaptive genetic variation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SSR Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA | Template for PCR amplification | 1 µg high molecular weight DNA; tissue preserved in ethanol, silica gel, or freezing [19] |

| SSR Primers | Target-specific amplification | Designed from flanking sequences; 18-25 nucleotides; species-specific or cross-transferable [13] |

| PCR Reagents | Amplification of target loci | Optimized annealing temperature (50-65°C gradient); fluorescent labeling for detection [13] |

| Electrophoresis Systems | Fragment separation by size | Polyacrylamide gel ("big board gel") with silver staining or capillary electrophoresis [13] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | SSR identification and data analysis | MISA, SSR Finder, Tandem Repeats Finder for identification; Structure, ARLEQUIN for population genetics [13] [16] |

| Reference Databases | Comparative analysis and marker transfer | Plant SSR database (PSSRD) with 249,822 SSRs from 112 plants; genomic databases [16] |

SSR markers continue to be indispensable tools in population genetics research, offering an optimal combination of abundance throughout genomes, codominant inheritance, and high polymorphism. These characteristics make them particularly valuable for predicting population structure, assessing genetic diversity, and understanding evolutionary relationships. While newer marker systems have emerged, SSRs maintain their relevance through continuous methodological refinements, particularly through integration with high-throughput sequencing technologies.

The future of SSR applications in population research lies in their integration with other genomic data types and the development of functional SSR markers linked to expressed genes. As genomic resources expand across more species, SSR markers will continue to provide robust, cost-effective solutions for addressing fundamental questions in population genetics, conservation biology, and breeding programs. Their demonstrated utility across diverse organisms—from plants to animals—ensures that SSRs will remain a cornerstone technology in molecular ecology and evolutionary biology for the foreseeable future.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) represent the most abundant form of genetic variation in genomes, serving as fundamental markers for deciphering population structure, evolutionary history, and trait architecture. Their widespread distribution, coupled with inherent stability compared to other marker types, underpins their utility in genomics research. This technical guide explores the core characteristics of SNPs—their genomic abundance, molecular stability, and distribution patterns—within the context of molecular markers for predicting population structure. We provide a comprehensive overview of quantitative benchmarks, detailed experimental methodologies for SNP discovery and validation, and essential analytical tools, offering researchers a framework for employing SNPs in population genomics and association studies.

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) are single-base substitutions in DNA sequences that occur at specific positions in a genome, typically with a minor allele frequency of greater than 1% in a population [20]. As one of the most common types of genetic variation, SNPs serve as crucial molecular markers for studying genetic diversity, population structure, and the genetic basis of complex diseases and agronomic traits. Their abundance and distribution across the genome make them particularly powerful for genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which test hundreds of thousands of genetic variants across many genomes to find those statistically associated with a specific trait or disease [21].

The stability of SNPs refers to their low mutation rate compared to other markers like microsatellites, making them evolutionarily stable and excellent for tracing population histories and genetic relationships. Furthermore, non-synonymous SNPs (nsSNPs), which result in amino acid changes in protein-coding sequences, can have direct functional consequences on protein structure, stability, and function, thereby influencing phenotypic variation and disease susceptibility [22] [23] [24].

Quantitative Profile of SNPs

The abundance and diversity of SNPs can be quantified using several key metrics derived from genotyping studies. The table below summarizes representative data from recent genomic studies across different species, illustrating the typical scale and diversity indices associated with SNP datasets.

Table 1: SNP Abundance and Diversity Metrics from Genomic Studies

| Species / Study | Total SNPs | Mean Gene Diversity | Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) | Observed Heterozygosity (Hₒ) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human (NTRK1 Gene) [22] | 2,070 nsSNPs analyzed | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 8 deleterious nsSNPs identified affecting protein stability. |

| Sugar Beet [20] | 4,609 (high-quality) | 0.31 (SNP data) | 0.22 (SNP data) | Not specified | A good level of conserved genetic diversity was found. |

| Sorghum [25] | 7,156 | 0.3 | Not specified | 0.07 | Low heterozygosity is typical for self-pollinating species. |

| Human (Forensic Panel) [26] | 900 - 9,000 panels evaluated | Not specified | Selection criterion | Not specified | Minimal panels enable accurate genetic record-matching. |

These quantitative measures are critical for assessing the informativeness of SNP datasets. For instance, the moderately high gene diversity and MAF reported in the sugar beet study [20] indicate a genetically diverse population suitable for association mapping. In contrast, the low observed heterozygosity in sorghum is characteristic of a self-pollinating crop [25].

Genomic Distribution and Density

SNPs are distributed throughout the genome, residing in both coding and non-coding regions. Their density is influenced by factors such as mutation rates, selective pressures, and recombination rates. In practice, the distribution is often analyzed by mapping SNPs to a reference genome.

Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) and SNP arrays are common methods for generating genome-wide SNP data. For example, a sugar beet study used 4,609 high-quality SNPs to analyze 94 accessions, revealing population structure correlated with geographical origin [20]. Similarly, a sorghum study used 7,156 SNPs to characterize the genetic diversity of 543 accessions [25].

The concept of "SNP neighborhoods" is important for applications like genetic record-matching, where SNPs located near specific target loci (e.g., within 1-megabase windows of forensic STRs) are selected to leverage linkage disequilibrium for accurate imputation and matching [26]. This non-random distribution and linkage with functional elements form the basis for many analytical techniques.

Stability of SNPs and Functional Impacts

Molecular Stability

SNPs exhibit greater stability than other genetic markers like Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) due to a lower mutation rate. This makes them particularly valuable for evolutionary studies and forensic applications where profile stability is paramount. Research into developing minimal SNP sets for backward-compatibility with existing STR profile databases highlights this utility, with studies showing that panels of just 900-9,000 strategically selected SNPs can achieve high-accuracy genetic record-matching [26].

Functional Stability of Non-Synonymous SNPs

The functional impact of nsSNPs is a critical aspect of their stability at the protein level. nsSNPs can alter amino acid sequences, potentially disrupting protein structure, stability, and function. Computational tools are essential for predicting these deleterious effects.

Table 2: In Silico Tools for Predicting Deleterious nsSNPs and Their Functions

| Tool Category | Example Tools | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Function Prediction | SIFT, PolyPhen-2, PROVEAN, PANTHER, SNPs&GO, PredictSNP, MutPred2 | Predicts whether an amino acid substitution is likely to be deleterious or neutral based on sequence conservation, physicochemical properties, and other features. [22] [23] [24] |

| Stability Prediction | I-Mutant 2.0, MUpro, DynaMut2 | Assesses the impact of a mutation on protein stability (e.g., change in free energy, ΔΔG). [22] [23] [24] |

| Conservation Analysis | ConSurf | Evaluates the evolutionary conservation of amino acid residues. [22] [23] |

| Structural Analysis | HOPE, Missense3D, Swiss-PDB Viewer | Models and visualizes the structural impact of mutations on proteins. [22] [24] |

For example, a comprehensive analysis of the NTRK1 gene identified eight deleterious nsSNPs (including L346P and G577R) that were predicted to decrease protein stability and disrupt ligand-binding interactions [22]. Similarly, studies on hypertension-related genes and ApoE in Alzheimer's disease have identified specific deleterious nsSNPs that alter protein stability, evolutionary conserved residues, and interaction networks, demonstrating their potential role in disease pathogenesis [23] [24].

Experimental Protocols for SNP Analysis

A robust workflow for SNP discovery and analysis is crucial for population structure research. The following protocol outlines the key steps from genotyping to validation.

Figure 1: Workflow for SNP discovery and analysis in population studies.

Genotyping and Data Generation

- Genotyping Methods: High-throughput methods include Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) [20] [25] and SNP arrays [27]. These methods generate raw genotype data across thousands to millions of markers for numerous samples.

- Variant Calling: Sequence data are aligned to a reference genome, and bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., GATK) are used to identify SNP positions and call genotypes, typically outputting a Variant Call Format (VCF) file [28].

Quality Control (QC) and Filtering

QC is critical to ensure data reliability. Standard filters include:

- Individual and Marker Missingness: Remove samples and SNPs with high rates of missing data (e.g., >10-20%) [20].

- Minor Allele Frequency (MAF): Filter out very rare SNPs (e.g., MAF < 0.01-0.05) to reduce noise in association tests [27].

- Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE): Significant deviations from HWE may indicate genotyping errors.

Population Genetics and GWAS Analysis

- Population Structure: Analyze genetic structure using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), ADMIXTURE, or similar tools to control for stratification in GWAS [25] [21].

- Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS): Identify marker-trait associations using statistical models (e.g., mixed models) that account for population structure and genetic relatedness [25] [21] [27].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Move beyond single-marker analysis by testing if SNPs within biological pathways are collectively associated with a trait. Methods like SNP Set Enrichment Analysis (SSEA) address challenges such as selecting representative SNPs for each gene [29].

In Silico Functional Validation of nsSNPs

For candidate nsSNPs identified from GWAS, a computational validation pipeline can be implemented:

- Retrieve nsSNPs: Extract nsSNPs from databases like dbSNP, ClinVar, and DisGeNET [24].

- Predict Deleterious Effects: Use a consensus of multiple tools (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2, PROVEAN, PANTHER) to identify high-risk variants [22] [23] [24].

- Assess Protein Stability: Utilize tools like I-Mutant, MUpro, and DynaMut2 to calculate stability changes (ΔΔG) [22] [23].

- Model Structural Impact: Employ molecular docking (e.g., with AutoDock Vina) and dynamics simulations (e.g., 100 ns simulations) to visualize and quantify changes in protein-ligand interactions and conformational stability [22] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for SNP Analysis

| Category | Item / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping | DArTseq / GBS | High-throughput sequencing methods for genome-wide SNP discovery. [20] [25] |

| Analysis Software | PLINK [21], SNP & Variation Suite (SVS) [27], GCViT [28] | Software for quality control, population genetics, GWAS, and visualization of SNP data. |

| In Silico Prediction | SIFT, PolyPhen-2, PROVEAN, I-Mutant 2.0, DynaMut2 | Computational tools for predicting the functional and structural impact of nsSNPs. [22] [23] [24] |

| Reference Databases | dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, ClinVar | Public repositories for SNP validation, frequency data, and clinical annotation. [24] [27] |

| Imputation Tool | BEAGLE | Software for imputing missing genotypes or STRs from SNP haplotypes using a reference panel. [26] [27] |

SNPs, characterized by their high abundance, genomic-wide distribution, and molecular stability, are indispensable tools in modern genetics for elucidating population structure and the genetic basis of complex traits. The quantitative frameworks and experimental protocols detailed in this guide provide a roadmap for researchers to leverage SNPs effectively. As genotyping technologies advance and computational methods for predicting functional impacts become more sophisticated, the resolution and applicability of SNPs in predictive genomics, personalized medicine, and crop improvement will continue to expand, solidifying their role as a cornerstone of molecular marker research.

In the field of population genetics, molecular markers serve as powerful tools for deciphering population structure, evolutionary history, and adaptive potential. Among the various metrics employed, Expected Heterozygosity (He) and Allelic Richness are two fundamental measures of genetic diversity, each providing unique and critical insights. While often related, these metrics capture different aspects of a population's genetic variation and are sensitive to different evolutionary forces. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core metrics, detailing their theoretical foundations, calculation methodologies, and interpretation within the context of population structure research. Understanding their distinct behaviors and applications is essential for researchers in conservation genetics, breeding programs, and evolutionary biology aiming to make informed predictions and decisions based on genetic data.

Expected Heterozygosity (He)

Definition and Theoretical Foundation

Expected Heterozygosity (He), also known as Nei's gene diversity (D), is a cornerstone metric of genetic diversity. It is formally defined as the probability that two randomly sampled allele copies from a population are different [30]. Conceptually, it represents the proportion of heterozygous genotypes expected in a population assuming it is in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE)—that is, under conditions of random mating, absence of selection, mutation, and genetic drift [31]. Its value ranges from 0, indicating no heterozygosity (all individuals are homozygous for the same allele), to nearly 1.0 for a system with a large number of equally frequent alleles [32]. For a single locus, it is calculated as one minus the sum of the squared allele frequencies:

He = 1 - ∑(pi)²

Where pi is the frequency of the ith allele at a locus [32] [31]. This formula effectively subtracts the total homozygosity from 1 to arrive at heterozygosity. With just two alleles, the expected heterozygosity is given by 2pq, which is equivalent to the more general formula [32]. The metric is maximized when all alleles have equal frequencies.

Estimation and Interpretation in Research

In practice, Observed Heterozygosity (Ho) is the straightforward count of heterozygous individuals in a sample divided by the total sample size. However, He is less sensitive to sample size than Ho and is therefore generally preferred for characterizing and comparing genetic diversity across populations and studies [31]. The comparison between Ho and He is biologically informative. A significantly lower Ho than He suggests potential inbreeding or Wahlund effect (a substructure within the sampled population), whereas a higher Ho than expected may indicate isolate-breaking, the mixing of two previously isolated populations [32] [31].

Advanced estimation methods account for non-ideal samples. For instance, related or inbred individuals in a sample introduce dependence among allele copies, causing the classic estimator (which assumes independent samples) to be biased downward. General unbiased estimators have been developed that incorporate a kinship coefficient (Φ) to correct for this bias [30]. Furthermore, using the Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) of allele frequencies, which incorporates the kinship matrix, can yield an estimator of He (termed H~BLUE) with a lower mean squared error, providing improved precision for samples with complex pedigrees [30].

Workflow for Genetic Diversity Assessment

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for assessing genetic diversity and population structure using molecular markers, from sampling through to data analysis and interpretation.

Allelic Richness

Definition and Conceptual Importance

Allelic Richness is a more direct measure of genetic diversity, defined as the number of distinct alleles per locus in a population [33] [34]. Unlike He, which is heavily influenced by the frequencies of the most common alleles, allelic richness gives equal weight to all alleles, regardless of their frequency. This makes it a crucial metric for assessing a population's long-term adaptive potential and evolutionary plasticity [33] [34]. The raw number of alleles observed in a sample is highly dependent on sample size, making straightforward comparisons invalid if sample sizes differ. Therefore, statistical methods like rarefaction or extrapolation are required to estimate allelic richness for a standardized sample size [35].

Sensitivity to Evolutionary Forces

Allelic richness is particularly sensitive to population bottlenecks and founder events [33]. During such events, rare alleles are easily lost by chance (genetic drift). Since these rare alleles contribute little to the overall heterozygosity (He), He may remain relatively high even as allelic richness drops significantly. For example, a population that loses several rare alleles might still have a high He if the remaining alleles are at intermediate frequencies. Consequently, allelic richness is often considered a more sensitive indicator of past demographic contractions and a better predictor of a population's future evolutionary capacity than He [33]. The loss of alleles represents a permanent reduction in the "raw material" for natural selection.

Estimation Methodologies

To compare allelic richness across populations with differing sample sizes, the rarefaction method is widely used. This technique estimates the expected number of alleles in a smaller, standardized sample size (e.g., the smallest number of genes examined in any population) by repeatedly resampling from the larger datasets [35]. An alternative approach is extrapolation, which adds the expected number of missing alleles (given the sample size and the allelic frequencies observed over the entire set of populations) to the number of alleles actually observed in a population [35]. This method may be recommended when population sample sizes are low on average or highly unbalanced. Both methods can be extended to measure "private allelic richness"—the number of alleles unique to a particular population—which is a valuable criterion for assessing uniqueness in conservation genetics [35].

Comparative Analysis of He and Allelic Richness

Key Differences and Behavioral Contrasts

While both He and Allelic Richness measure genetic diversity, they are based on different mathematical principles and can behave quasi-independently across populations, providing complementary information [35]. The table below summarizes their core differences.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Expected Heterozygosity and Allelic Richness

| Feature | Expected Heterozygosity (He) | Allelic Richness |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Probability two random alleles are different [30]. | Number of distinct alleles per locus [34]. |

| Mathematical Basis | Function of squared allele frequencies (1 - ∑pi²) [32]. |

Simple count of alleles, standardized for sample size [35]. |

| Sensitivity to Rare Alleles | Low; heavily weighted by common alleles. | High; all alleles contribute equally. |

| Response to Bottlenecks | Less sensitive; can remain high if allele frequencies equalize. | Highly sensitive; rapid loss of rare alleles [33]. |

| Primary Interpretation | Short-term fitness, inbreeding risk. | Long-term adaptive potential, evolutionary capacity [33]. |

| Standardization Need | Less sensitive to sample size, but requires HWE assumptions. | Requires rarefaction/extrapolation for sample size correction [35]. |

Empirical Evidence from Research Studies

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate the distinct behaviors of these metrics. A study on the argan tree of Morocco using isozyme loci found a higher level of population differentiation for allelic richness than for gene diversity (He) [35]. This indicates that genetic drift has a stronger differentiating effect on allelic richness than on He. Research on founder events has shown both theoretically and empirically that allelic richness is more sensitive to population contractions than heterozygosity, as the loss of rare alleles has a minimal impact on He but directly reduces the allele count [33]. Furthermore, simulation models suggest that conservation guidelines like the "One Migrant per Generation" rule, derived from heterozygosity-based models, may be inadequate for preserving allelic richness, underscoring the importance of using both metrics for management decisions [33].

Table 2: Genetic Diversity Metrics from Recent Genomic Studies

| Study Organism | Marker Type | Mean Expected Heterozygosity (He) | Notes on Allelic Richness / Diversity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asparagus officinalis (64 lines) | 12,886 GBS-SNPs | 0.370 (mean) | Population structure revealed 4 distinct sub-populations. | [36] |

| Angiopteris fokiensis (fern) | 15 genomic SSRs | Reported for populations (Range: ~0.166 - 0.203) | 4,327,181 SSR loci identified; 55% of variation within populations. | [37] |

| Extra-Early Orange Maize (187 lines) | 9,355 DArTseq-SNPs | 0.36 (mean) | PIC averaged 0.29; population structure analysis revealed K=4 groups. | [38] |

| Sour Passion Fruit | 28 ISSR markers | Reported for populations (Range: 0.166 - 0.203) | 55% of molecular variance found within populations. | [39] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, software, and materials essential for conducting genetic diversity studies using molecular markers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Genetic Diversity Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB Extraction Buffer | Gold-standard protocol for high-quality DNA extraction from plant tissues, which contain polysaccharides and polyphenols [39]. | Contains Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide to lyse cells and separate DNA from other molecules. |

| DArTseq / GBS Platforms | High-throughput sequencing methods for discovering and genotyping thousands of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome [36] [38]. | Reduces genome complexity using restriction enzymes, cost-effective for large-scale genotyping. |

| Microsatellite (SSR) Markers | Co-dominant, highly polymorphic markers for fine-scale population genetics, parentage analysis, and diversity assessment [37]. | Developed from genome surveys or transcriptomes; high polymorphism information content (PIC). |

| ISSR Primers | PCR-based dominant markers for rapid assessment of genetic diversity and structure without prior sequence knowledge [39]. | Targets inter-simple sequence repeat regions; high multiplex ratio and reproducibility. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Essential enzyme for the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), used to amplify specific DNA regions for genotyping [39]. | Thermostable; choice of enzyme can affect fidelity and efficiency of amplification. |

| Analysis Software (TASSEL, GAPIT, STRUCTURE) | Bioinformatics packages for analyzing molecular data; perform population structure, PCA, kinship, and LD analysis [36]. | Critical for transforming raw genotyping data into interpretable genetic metrics and models. |

Expected Heterozygosity (He) and Allelic Richness are both indispensable, yet distinct, metrics in the population geneticist's toolkit. He provides a robust measure of the diversity available for immediate fitness and short-term evolutionary potential, weighted towards common alleles. In contrast, Allelic richness serves as a sensitive barometer of a population's demographic history and its reservoir of genetic variants for long-term adaptation. A comprehensive molecular study predicting population structure must integrate both metrics to fully capture the dynamics of genetic diversity. This integrated approach reveals not only the current genetic health of populations but also their historical trajectories and future resilience, thereby enabling more effective and predictive conservation, breeding, and management strategies.

Understanding the genetic architecture of complex traits is a fundamental objective in genetics, with profound implications for agriculture, medicine, and evolutionary biology. Complex traits, including many diseases and agriculturally important features, are typically controlled by multiple genes and influenced by environmental factors, making them difficult to study. Genetic linkage mapping and Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) analysis are powerful statistical methods that bridge the gap between molecular markers and phenotypic variation. These techniques enable researchers to identify chromosomal regions associated with traits of interest by exploiting the natural process of genetic recombination [40] [41].

Within population genetics research, understanding population structure—the systematic difference in allele frequencies between subpopulations—is crucial as it can confound genetic association studies [42]. Molecular markers provide the essential tools for delineating this structure, and when integrated with trait data, they reveal how genetic variation is organized and maintained within and between populations. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of how genetic linkage and QTL mapping transform molecular markers into powerful predictors of phenotypic variation within the broader context of population structure research.

Core Principles: Linkage, Recombination, and QTLs

Genetic Linkage and Linkage Mapping

Genetic linkage describes the tendency for genes and other genetic markers that are physically close together on a chromosome to be inherited together during meiosis. This occurs because closely positioned markers are less likely to be separated by chromosomal crossover events. The fundamental unit of measurement in linkage mapping is the recombination frequency, which quantifies the likelihood of a crossover event occurring between two markers. A 1% recombination frequency is defined as one centimorgan (cM), providing a relative measure of genetic distance rather than a specific physical distance [41].

A genetic linkage map is a graphical representation showing the relative positions of known genes or genetic markers on a chromosome based on their recombination frequencies, unlike a physical map which shows the actual physical location in base pairs [41]. The resolution of a genetic map is relatively coarse, approximately one million base pairs, and is influenced by uneven recombination rates along chromosomes, with areas of hotspot and coldspot recombination [41].

Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Analysis

Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) analysis is a statistical framework that links phenotypic data (trait measurements) with genotypic data (molecular markers) to explain the genetic basis of variation in complex traits [40]. The primary goal of QTL analysis is to identify the number, location, action, and interaction of chromosomal regions that influence quantitative traits. A key question addressed by QTL analysis is whether phenotypic differences are primarily due to a few loci with fairly large effects, or to many loci, each with minute effects. Research suggests that for many quantitative traits, a substantial proportion of phenotypic variation can be explained by few loci of large effect, with the remainder due to numerous loci of small effect [40].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Genetic Mapping

| Term | Definition | Unit of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Linkage | Tendency for genes close together on a chromosome to be inherited together | N/A |

| Recombination Frequency | The likelihood of a crossover event between two genetic markers | Percentage (%) |

| Centimorgan (cM) | A unit of genetic distance representing a 1% recombination frequency | cM |

| Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) | A chromosomal region associated with a quantitative trait | Chromosomal position |

| LOD Score | A statistical measure of the strength of evidence for linkage | Log-odds unit |

Molecular Markers: The Foundation of Genetic Mapping

Molecular markers are identifiable DNA sequences with known locations on chromosomes that serve as landmarks for genetic mapping. These markers are preferred for genotyping because they are unlikely to affect the trait of interest directly and can be easily tracked across generations [40].

Table 2: Common Molecular Marker Types Used in Genetic Mapping

| Marker Type | Full Name | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSR | Simple Sequence Repeat (Microsatellite) | Short, repeating DNA sequences (2-6 bp); highly polymorphic, codominant, multi-allelic [40] [43] | Genetic diversity studies, linkage mapping, population structure [43] [44] |

| SNP | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism | Single base-pair variation; most abundant marker type [40] [45] | High-density genetic maps, genome-wide association studies [45] [7] |

| RFLP | Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism | Variation in restriction enzyme cutting sites; early marker type [40] [41] | Early genetic mapping studies |

| AFLP | Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism | Combines restriction enzyme digestion with PCR amplification [41] | Genetic linkage analysis where polymorphism rate is low |

The choice of marker depends on the specific research goals, available resources, and the biological system under investigation. For determining genetic diversity, SSR markers are often preferred because they are highly polymorphic, codominant, multi-allelic, highly reproducible, and have good genome coverage [43]. In contrast, SNP markers are ideal for high-density mapping due to their abundance throughout the genome [45].

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Population Design for QTL Analysis

The foundation of a successful QTL mapping experiment lies in careful population design. The basic requirements include: 1) two or more strains of organisms that differ genetically for the trait of interest, and 2) genetic markers that distinguish between these parental lines [40]. A typical crossing scheme involves crossing parental strains to produce heterozygous F1 individuals, which are then crossed using various schemes (e.g., F2 population, backcross, recombinant inbred lines) to produce a derived population for phenotyping and genotyping [40].

For traits controlled by tens or hundreds of genes, the parental lines need not actually be different for the phenotype in question; rather, they must simply contain different alleles, which are then reassorted by recombination in the derived population to produce a range of phenotypic values [40]. Markers that are genetically linked to a QTL influencing the trait of interest will segregate more frequently with trait values, whereas unlinked markers will not show significant association with phenotype [40].

Genotyping and Linkage Map Construction

Modern genotyping approaches leverage high-throughput technologies:

- DNA Extraction and Quality Control: High-quality genomic DNA is extracted from all individuals in the mapping population. Quality is assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis and ultraviolet spectrophotometry to ensure integrity, concentration, and purity [7].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: For SNP-based mapping, sequencing libraries are prepared from qualified DNA. In a papaya QTL study, libraries with appropriate fragment sizes were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platform [45].

- Variant Detection: Raw sequencing data undergoes quality control (using tools like FASTP) to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases. Clean reads are aligned to a reference genome using aligners like BWA, followed by variant (SNP) calling and genotyping using tools such as the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) [7].

- Linkage Map Construction: Filtered SNPs are used for linkage analysis. Software like JoinMap or MapMaker is employed to group markers into linkage groups and estimate genetic distances based on recombination frequencies [41] [45]. The initial map may contain many distorted markers; thus, a final map is typically constructed using only markers that segregate as expected [45].

QTL Analysis Workflow

Once a linkage map is constructed, QTL analysis proceeds through these key steps:

- Phenotyping: Precise measurement of the target trait(s) across all individuals in the mapping population.

- Interval Mapping: Statistical analysis tests for associations between marker genotypes and phenotypic values. Composite interval mapping with a sliding window is commonly used to detect QTLs [45].

- Significance Testing: LOD (Logarithm of Odds) scores are calculated to determine the statistical significance of detected QTLs. Permutation tests are often used to establish significance thresholds.

- Variance Explanation: For significant QTLs, the percentage of phenotypic variance explained (PVE) is calculated [45].

- Candidate Gene Identification: With high-density maps, researchers can narrow QTL regions to identify candidate genes using positional cloning, bioinformatics, and functional validation [40].

Figure 1: QTL Mapping Experimental Workflow. This diagram illustrates the key steps from population development to candidate gene identification.

Case Study: QTL Mapping of Fruit Quality Traits in Papaya

A comprehensive study on papaya (Carica papaya L.) demonstrates the practical application of QTL mapping for fruit quality traits [45]. Researchers employed a genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach to identify QTLs conditioning desirable fruit quality traits.

Methodology and Results

A linkage map was constructed comprising 219 SNP loci across 10 linkage groups covering 509 cM [45]. In total, 21 QTLs were identified for seven key fruit quality traits: flesh sweetness, fruit weight, fruit length, fruit width, skin freckle, flesh thickness, and fruit firmness [45]. The proportion of phenotypic variance explained by a single QTL ranged from 3.1% to 19.8% [45].