Navigating Ligand Parameterization Errors in Molecular Dynamics: From Force Field Pitfalls to Reliable Drug Discovery

Accurate ligand parameterization is a critical, yet often error-prone, foundation for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sources, impacts, and solutions for ligand parameterization errors. We explore the fundamental limitations of traditional force fields and the challenges of covering expansive chemical space. The discussion then progresses to modern methodological advances, including automated, data-driven, and machine learning-aided parameterization strategies. A practical troubleshooting guide addresses common optimization challenges, while a final section establishes robust validation and benchmarking protocols. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications and validation frameworks, this article serves as an essential resource for researchers aiming to enhance the predictive power and reliability of their MD-driven projects.

Navigating Ligand Parameterization Errors in Molecular Dynamics: From Force Field Pitfalls to Reliable Drug Discovery

Abstract

Accurate ligand parameterization is a critical, yet often error-prone, foundation for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the sources, impacts, and solutions for ligand parameterization errors. We explore the fundamental limitations of traditional force fields and the challenges of covering expansive chemical space. The discussion then progresses to modern methodological advances, including automated, data-driven, and machine learning-aided parameterization strategies. A practical troubleshooting guide addresses common optimization challenges, while a final section establishes robust validation and benchmarking protocols. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications and validation frameworks, this article serves as an essential resource for researchers aiming to enhance the predictive power and reliability of their MD-driven projects.

The Root of the Problem: Understanding Ligand Parameterization Errors and Their Impact on Simulation Outcomes

Troubleshooting Guides

Geometry Optimization Failures Due to Bond Order Discontinuity

Problem Description: During geometry optimization with reactive force fields like ReaxFF, the calculation fails to converge. The energy and forces exhibit sudden, discontinuous changes between optimization steps, causing the optimizer to become unstable.

Root Cause:

The primary cause is a discontinuity in the derivative of the ReaxFF energy function. This is often related to the bond order cutoff (Engine ReaxFF%BondOrderCutoff), which has a default value of 0.001. This cutoff determines whether valence or torsion angle terms are included in the energy calculation. When the order of a bond crosses this cutoff value between steps, the force (energy derivative) experiences a sudden jump [1].

Solution Steps:

- Enable 2013 Torsion Angles: Set

Engine ReaxFF%Torsionsto2013. This makes the torsion angles change more smoothly at lower bond orders, though it does not affect valence angles. Be aware that this changes the bond order dependence of the 4-center term [1]. - Decrease the Bond Order Cutoff: Reduce the value of

Engine ReaxFF%BondOrderCutoff(e.g., from 0.001 to a lower value). This significantly reduces the discontinuity in valence angles and somewhat in torsion angles, at the cost of increased computational time because more angles must be included [1]. - Use Tapered Bond Orders: Implement the tapered bond order method by Furman and Wales by setting

Engine ReaxFF%TaperBO. This approach smoothens the bond order function itself, mitigating discontinuities [1].

Table: Solutions for Geometry Optimization Failures in ReaxFF

| Solution | Command/Setting | Effect | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enable 2013 Torsions | Engine ReaxFF%Torsions = 2013 |

Smoother torsion potentials at low bond orders | Alters 4-center term bond order dependence |

| Decrease Bond Order Cutoff | Engine ReaxFF%BondOrderCutoff = [lower value] |

Reduces discontinuity in valence and torsion terms | Increases computational cost |

| Activate Tapered Bond Orders | Engine ReaxFF%TaperBO |

Smoothens the bond order function | Implements method from Furman and Wales [1] |

Handling Missing Force Field Parameters

Problem Description:

When setting up a simulation for a novel molecule (e.g., a non-standard ligand), the parameterization tool (such as antechamber, tleap, or EMC) fails with errors indicating missing parameters for specific bonded terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals) or non-bonded increments.

Root Cause:

Standard molecular mechanics force fields (like GAFF, AMBER, PCFF) are built from parameter tables. If a molecule contains a chemical moiety, atom type, or interaction (e.g., a specific bond between atom types S and CM) not defined in the force field's table, the simulation engine cannot assign the necessary forces [2] [3].

Solution Steps:

- Identify Missing Parameters: Carefully read the error message to identify the exact atom types and interaction type (bond, angle, dihedral) that is missing. For example:

Could not find bond parameter for atom types: S - CM[2]. - Manual Parameterization: Derive the missing parameters. This typically involves:

- Quantum Mechanics (QM) Calculations: Performing geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency calculations on a small model molecule containing the functional group in question.

- Parameter Fitting: Fitting the bond, angle, and dihedral parameters to the QM-calculated energy surface or Hessian matrix. Tools like

Q-Forcecan automate parts of this process [4]. - Add Parameters to Force Field File: Manually add the new parameters to the force field file (e.g., a

frcmodfile in AMBER) in the correct format.

- Use a Data-Driven Force Field: Consider using a modern, data-driven force field like

ByteFForEspalomathat uses machine learning to predict parameters for a vast chemical space, reducing the chance of missing parameters [5]. - Bond Increment Warnings (EMC Specific): For missing bond increment parameters (related to partial charge assignment) in

EMC, you can change the software's behavior. Instead of throwing an error, setfield_incrementtowarnorignorein your.eshscript, which will assign a zero contribution to the charge for that missing increment [3].

Inaccurate Atomic Dynamics and Rare Event Prediction with MLIPs

Problem Description: A Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) reports low root-mean-square errors (RMSE) for energies and forces on a standard test set. However, when used in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, it fails to accurately reproduce key physical properties or atomic dynamics, such as diffusion energy barriers, rare events (e.g., vacancy migration), or radial distribution functions [6].

Root Cause: Conventional testing of MLIPs using average errors (e.g., MAE, RMSE) on random test sets is insufficient. These tests do not guarantee accuracy on specific, critical configurations encountered during MD, such as transition states or defect migrations. The MLIP may have learned the training data well but fails to generalize to the complex potential energy surface of real dynamics [6].

Solution Steps:

- Develop Targeted Evaluation Metrics: Move beyond average errors. Create specialized test sets that focus on the physical phenomena of interest, such as:

- Enhance Training Data: Augment the MLIP training dataset to include configurations relevant to the failing dynamics. This includes transition states, defect structures, and non-equilibrium geometries sampled from AIMD [6].

- Validate with Physical Properties: Always validate the final MLIP by running short MD simulations and comparing key outputs (e.g., diffusion coefficients, vacancy formation energies, RDFs) directly against AIMD or experimental data, not just against energy and force errors [6].

Table: Advanced Error Metrics for MLIP Validation

| Metric Type | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Rare Event (RE) Test Sets | Snapshots from AIMD of migrating point defects (vacancies, interstitials) | Tests MLIP accuracy on critical, non-equilibrium configurations crucial for diffusion [6] |

| Force Errors on RE Atoms | Measures force RMSE/MAE specifically on the few atoms actively involved in the migration | A more sensitive indicator of dynamics performance than global force error [6] |

| Property-based Validation | Direct comparison of MD-predicted properties (e.g., energy barriers, RDFs) with reference data | Ensures the MLIP reproduces the target physical phenomena, not just low static errors [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I see a warning about "Inconsistent vdWaals-parameters in forcefield." What does this mean? This warning indicates that not all atom types in your force field file have consistent Van der Waals screening and inner core repulsion parameters. While the calculation may proceed, it signals a potential inconsistency in how non-bonded interactions are defined, which could lead to unphysical behavior. You should check the parameter definitions for your atom types [1].

Q2: What is a "polarization catastrophe" in the context of force fields, and how can I avoid it?

A polarization catastrophe is a force field failure where, at short interatomic distances, the electronegativity equalization method (EEM) predicts an unphysically large charge transfer between two atoms. This occurs when the EEM parameters for an atom type (eta and gamma) do not satisfy the relation eta > 7.2*gamma. To avoid this, ensure your force field's EEM parameters meet this stability criterion. The ReaxFF EEM routine checks that atomic charges stay within [-10, Z] and will throw an error if this fails [1].

Q3: My simulation crashes with errors about missing torsion or angle parameters after I manually created a bond between a protein residue and a ligand. What went wrong?

This is a common issue when parameterizing covalently bound ligands. Standard parameterization tools often only generate parameters for the ligand itself, not for the new interfacial bonds and angles created when it is linked to a protein residue (e.g., a cysteine). You must manually define the parameters for these new interaction terms (e.g., S - CM bond, S - CM - CM angle, 2C - S - CM angle, and associated dihedrals) and add them to the system, typically via a frcmod file loaded in tleap [2].

Q4: Are low average errors on a test set a reliable indicator that my MLIP will perform well in MD simulation? No. It has been demonstrated that MLIPs can have low root-mean-square errors (RMSE) on standard test sets yet still produce significant discrepancies in molecular dynamics simulations. These discrepancies can include inaccurate diffusion barriers, defect properties, and rare events. It is crucial to use targeted evaluation metrics and validate the MLIP's performance on actual MD properties [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Evaluating Force Field Errors using Fragment Interaction Energies

This protocol provides a rigorous method for quantifying systematic and random errors in force fields or scoring functions, particularly for protein-ligand binding studies [7].

1. System Decomposition:

- Select a protein-ligand complex of interest (e.g., HIV-II protease with indinavir).

- Decompose the complex into chemically meaningful, interacting fragment pairs (e.g., a ligand hydroxyl group hydrogen-bonded to a protein backbone carbonyl).

2. Quantum Mechanics Reference Calculations:

- For each isolated fragment pair, compute the electronic interaction energy (ΔE_ref) using a high-level quantum mechanics method, such as CCSD(T)/CBS, which serves as the reference standard [7].

- The interaction energy is calculated as:

ΔE_ref = E(fragment_pair) - E(fragment1) - E(fragment2)[7].

3. Force Field Calculations:

- Compute the interaction energy (ΔE_FF) for the same fragment pair geometries using the force field or scoring function you are evaluating.

4. Error Analysis and Propagation:

- Calculate the error for each fragment pair:

Error_fragment = ΔE_FF - ΔE_ref. - Construct a probability density function (e.g., a Gaussian distribution) of the errors to characterize the systematic error (mean, μ) and random error (standard deviation, σ) of the method [7].

- Estimate the Best-Case Scenario (BCS) error for the entire protein-ligand complex by propagating the random errors from all N fragment pairs as the square root of the sum of squares [7]:

BCS_error = √[ (Errorâ‚)² + (Errorâ‚‚)² + ... + (Error_N)² ]

- This BCS_error is a lower-bound estimate for the total error in the computed binding energy, as it ignores errors from enthalpy, entropy, and solvation terms [7].

Protocol for Assessing MLIP Accuracy on Atomic Dynamics

This protocol outlines steps to thoroughly test a Machine Learning Interatomic Potential beyond standard static error metrics [6].

1. Create Specialized Testing Sets:

- Rare Event (RE) Sets: Use ab initio MD (AIMD) simulations at relevant temperatures to generate atomic trajectories containing migrating point defects (e.g., vacancies, interstitials). Extract hundreds of snapshots from these trajectories to create

D_RE-VTestingandD_RE-ITestingdatasets [6]. - Ensure these configurations are not included in the MLIP's training set.

2. Perform Targeted Error Quantification:

- Calculate the RMSE of energies and forces for the MLIP on the standard test set and the RE test sets.

- Compute a Force Performance Score by focusing the force error analysis specifically on the atoms identified as participating in the rare event (the migrating atom and its immediate neighbors) [6].

3. Validate with Molecular Dynamics and Properties:

- Run full MD simulations using the MLIP.

- Compare the following outputs directly against AIMD reference data:

- Radial distribution functions (RDFs).

- Mean-squared displacement (MSD) and diffusion coefficients.

- Energy barriers for defect migration computed from the MD trajectory.

- An MLIP that accurately reproduces these properties is considered more reliable for dynamic simulations, even if its standard test set RMSE is similar to another, less robust potential [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Force Field Parameterization and Error Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| ByteFF | Data-Driven Force Field | An Amber-compatible force field for drug-like molecules that uses a graph neural network to predict parameters across a broad chemical space, reducing missing parameter issues [5]. |

| Q-Force Toolkit | Automated Parameterization Tool | A framework for the systematic and automated parameterization of force fields, including the derivation of bonded coupling terms for 1-4 interactions [4]. |

| LUNAR Software | Force Field Development | Provides a user-friendly interface and methods for reparameterizing Class II force fields, such as integrating Morse potentials for bond dissociation [8]. |

| Rare Event (RE) Test Sets | Evaluation Metric | Specialized datasets of atomic configurations from AIMD simulations used to test MLIP accuracy on diffusion and defect migration events [6]. |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer | Quantum Chemistry Utility | An optimizer used in quantum chemistry workflows for geometry optimizations, often employed during the generation of training data for force fields [5]. |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | Quantum Chemistry Method | A high-level ab initio method considered a "gold standard" for generating reference interaction energies used in force field error benchmarking [7]. |

| Oxfendazole | Oxfendazole, CAS:53716-50-0, MF:C15H13N3O3S, MW:315.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Elagolix Sodium | Elagolix Sodium|GnRH Antagonist for Research | Elagolix sodium is a potent, oral GnRH receptor antagonist for researching endometriosis and hormone-dependent pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Bond Formation and Breaking Failures

Problem: Your molecular dynamics simulation fails to model chemical reactions, such as a ligand forming a covalent bond with a protein target. The simulation may crash or produce unphysical results when bonds break.

Explanation: Classical force fields use fixed, harmonic potentials for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals). This functional form is incapable of describing the process of bond breaking and formation, which is fundamental to chemical reactivity [9].

Solution:

- Switch to Reactive Force Fields: Implement a reactive force field like ReaxFF, which uses bond-order formalism to allow dynamic bond formation/breaking [9] [10].

- Apply Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF): Train or use pre-trained MLFFs on quantum mechanical data for reactive pathways [10] [11].

- Hybrid QM/MM Approach: For specific reactive sites, use quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics where the reactive core is treated with QM methods [12].

Validation Protocol:

- Compare bond distances and energies against quantum mechanical benchmarks

- Test on known reaction pathways before applying to novel systems

- Verify energy conservation in reactive molecular dynamics simulations

Guide :

Problem: A force field parameterized for one chemical system (e.g., drug-like molecules) performs poorly when applied to a different system (e.g., polymers or inorganic complexes), yielding inaccurate geometries or energies.

Explanation: Classical force fields have limited transferability because their parameters are typically fitted to specific chemical environments and lack the flexibility to adapt to new bonding situations [10].

Solution:

- System-Specific Parameterization: Derive new parameters using quantum mechanical data for the specific chemical moieties in your system [9].

- Utilize Foundational MLFFs: Implement universal MLFFs like those trained on the OMol25 dataset, which cover broad chemical spaces [11].

- Leverage Multi-Element Force Fields: Use force fields parameterized for diverse elements rather than specialized ones [10].

Validation Protocol:

- Calculate formation energies against experimental or high-level QM data

- Compare radial distribution functions with experimental scattering data

- Validate thermodynamic properties (density, heat capacity) against measurements

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Approaches for Addressing Transferability

| Force Field Type | Parameter Transferability | Required Reparameterization | Typical Elements Covered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF | Low | Extensive for new chemistries | Limited sets (e.g., C, H, N, O, S, P) [10] |

| Reactive FF (ReaxFF) | Medium | Moderate for new elements | Broad (including metals) [9] |

| Machine Learning FF | High | Minimal (retraining with new data) | Very broad (H, C, N, O, F, Si, S, Cl, etc.) [10] [11] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my simulation of polymer density deviate significantly from experimental values?

Answer: Classical force fields often struggle with polymer systems due to their complex interplay of intra- and intermolecular interactions. The fixed harmonic potentials cannot adequately capture the conformational flexibility and weak interactions that govern bulk polymer properties [10].

Recommended Action:

- Implement MLFFs specifically trained on polymeric systems, such as those using the Vivace architecture on PolyData datasets [10].

- Validate against multiple experimental properties (density, glass transition temperature) rather than single metrics.

- Ensure sufficient sampling of polymer chain configurations in your simulations.

Q2: How can I improve protein-ligand binding affinity predictions given force field limitations?

Answer: The rigidity of harmonic potentials in classical force fields leads to inaccurate descriptions of flexible ligand conformations and protein-ligand interactions, particularly for large, flexible signaling molecules [13].

Recommended Action:

- Combine MD with machine learning (MD/ML approach) to predict binding affinity rankings [13].

- Use tools like PLIP to analyze interaction patterns and identify key residues [14].

- Leverage curated datasets like MISATO that combine quantum mechanical properties with MD simulations [12].

Q3: What are the practical alternatives when my research involves chemical environments not covered by existing force fields?

Answer: Traditional parameterization for new chemical spaces is time-consuming and requires expertise. New approaches dramatically expand coverage [11].

Recommended Action:

- Use pre-trained universal models like Meta's UMA or eSEN trained on the OMol25 dataset [11].

- For polymers, utilize specialized MLFFs like Vivace with PolyData [10].

- For biomolecular systems, leverage datasets like MISATO that provide quantum-mechanically refined structures [12].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Force Field Methods

| Force Field Method | Computational Cost (Relative to QM) | Typical System Size | Time Scale | Accuracy for Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF | 10³–10ⶠfaster [9] | 10–100 nm [9] | Nanoseconds to microseconds [9] | Cannot model |

| Reactive FF (ReaxFF) | 10–1000 faster than QM [9] | Larger than QM [9] | Picoseconds to nanoseconds [9] | Medium |

| Machine Learning FF | 10³–10ⶠfaster than QM [10] | Similar to classical FF [10] | Nanoseconds [10] | High [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PLIP (Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler) | Analyzes molecular interactions in protein structures [14] | Detecting key residues in protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions |

| MISATO Dataset | Provides quantum-mechanically refined protein-ligand complexes with MD trajectories [12] | Training ML models for drug discovery; benchmark validation |

| OMol25 Dataset | Massive dataset of high-accuracy computational chemistry calculations [11] | Training universal MLFFs; diverse chemical space coverage |

| PolyData/PolyArena | Benchmark and dataset for polymer properties [10] | Developing and validating MLFFs for polymeric systems |

| ReaxFF | Reactive force field for bond formation/breaking [9] [10] | Simulating chemical reactions where classical FFs fail |

| Vivace MLFF | Machine learning force field for polymers [10] | Predicting polymer densities and glass transition temperatures |

| Cefclidin | Cefclidin|High-Purity Reference Standard | Cefclidin: A fourth-generation, parenteral cephalosporin antibiotic for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| (3E,5Z)-undeca-1,3,5-triene | (3E,5Z)-undeca-1,3,5-triene|High Purity| |

Experimental Workflow: Identifying Parameterization Errors

Validation Methodologies

Protocol 1: Quantum Mechanical Validation of Force Field Performance

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the accuracy of a force field for specific chemical systems against high-level quantum mechanical benchmarks.

Procedure:

- Select Representative Structures: Choose 10-20 molecular configurations spanning the relevant conformational space [12].

- Calculate Reference Data: Compute energies and forces using high-level QM methods (e.g., ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD as in OMol25) [11].

- Compare Force Field Predictions: Calculate the same properties using the force field.

- Statistical Analysis: Compute root-mean-square errors (RMSE) for energies and forces.

- Threshold: For reliable results, energy RMSE should be < 1 kcal/mol per atom for MLFFs [11].

Protocol 2: Experimental Property Validation

Purpose: To validate force field performance against experimentally measurable properties.

Procedure:

- Select Target Properties: Choose density, glass transition temperature (polymers), or binding affinity (drug discovery) [10].

- Run MD Simulations: Perform extensive sampling using the force field.

- Calculate Properties:

- Density: From NPT simulations

- Glass transition: From density vs. temperature curves

- Binding affinity: From free energy calculations

- Compare with Experiment: Calculate percentage errors and statistical significance.

Acceptance Criteria:

- Density errors < 2%

- Glass transition temperature errors < 10K

- Binding affinity rankings consistent with experimental trends [13]

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Systematic and Random Errors in Free Energy Calculations

Problem: My calculated binding free energies show significant deviations from experimental measurements. I suspect errors are propagating from the underlying energy models.

Background: In computational models, approximate energy functions rely on parameterization and error cancellation to agree with experiments. Errors in the energy of each microstate (conformation) of your system will propagate into your final thermodynamic quantities, like binding free energy [15].

Solution Steps:

- Diagnose Error Type: Determine if the error is systematic (consistent bias) or random (uncertainty). Systematic errors arise from consistent force field inaccuracies, while random errors relate to the precision of the energy model [15].

- Quantify Microstate Errors: Estimate the error for individual molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals contacts) in each sampled microstate. This can be done using fragment-based error databases [15].

- Propagate Errors Correctly:

- The systematic error in the free energy (A) is the Boltzmann-weighted average of the systematic errors of all sampled microstates:

δA_sys = Σ(P_i * δE_iSys), whereP_iis the probability of microstate i [15]. - The random error is the Pythagorean sum of the weighted random errors:

δA_rand = √[ Σ(P_i * δE_iRand)² ][15].

- The systematic error in the free energy (A) is the Boltzmann-weighted average of the systematic errors of all sampled microstates:

- Mitigation Strategy: Avoid end-point (single-structure) methods, as they maximize the impact of random errors. Instead, use methods that incorporate local sampling around energy minima, as this averaging effect naturally reduces random error in the final free energy estimate [15].

Guide 2: Resolving Physically Unrealistic Ligand Poses from Deep Learning Models

Problem: My deep learning-based docking or co-folding prediction results in ligand poses with steric clashes, incorrect bond lengths, or placements that defy chemical logic, even when the overall pose RMSD seems acceptable.

Background: Advanced co-folding models (e.g., AlphaFold3, RoseTTAFold All-Atom) can be vulnerable to adversarial examples. They may memorize patterns from training data rather than learning underlying physical principles, leading to failures when presented with perturbed systems [16].

Solution Steps:

- Identify Failure Mode: Run a series of diagnostic challenges on your model using a known protein-ligand complex (e.g., ATP-bound CDK2) [16]:

- Binding Site Removal: Mutate all binding site residues to glycine. A physically aware model should displace the ligand when favorable interactions are removed.

- Binding Site Occlusion: Mutate residues to bulky amino acids like phenylalanine. This tests the model's ability to handle steric exclusion.

- Chemical Perturbation: Modify the ligand to interrupt key interactions (e.g., removing a charged group). This checks if the model understands electrostatics.

- Interpret Results: If the model persists in placing the ligand in the original, now-unfavorable site, it indicates overfitting and a lack of genuine physical understanding [16].

- Mitigation Strategy: For critical applications, do not rely solely on deep learning predictions. Use these poses as initial guesses for refinement with physics-based methods (e.g., molecular dynamics with a traditional force field) or experimental validation.

Guide 3: Correcting for Data Bias in Machine Learning Affinity Predictions

Problem: My deep learning scoring function performs excellently on standard benchmarks but fails dramatically when applied to my own, novel protein-ligand complexes.

Background: A significant issue in the field is train-test data leakage between popular training sets (e.g., PDBbind) and benchmark sets (e.g., CASF). Models can achieve high benchmark scores by memorizing structural similarities rather than learning generalizable principles of binding, leading to poor real-world performance [17].

Solution Steps:

- Check Dataset Independence: If using a pre-trained model, verify the training data. For model development, use rigorously filtered datasets like PDBbind CleanSplit, which removes complexes from the training set that are highly similar to those in the test sets [17].

- Employ Robust Splitting: Avoid random splits of your data. Use structure-based clustering that accounts for protein similarity, ligand similarity, and binding pose similarity to ensure training and test sets are truly independent [17] [18].

- Validate Generalization: Test your model on a small, carefully curated set of in-house data that is guaranteed to be independent and novel before deploying it for virtual screening.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: I keep getting "Residue not found in topology database" errors in GROMACS. What should I do?

This error means the force field you selected does not have parameters for the residue in your coordinate file.

- First, check residue naming: Ensure the residue name in your file matches the expected name in the force field's database.

- For new molecules: You cannot use

pdb2gmxfor arbitrary molecules unless you build a residue topology database entry yourself. You will need to parameterize the molecule separately using another tool, create a topology file (.itp), and include it in your main topology file [19].

FAQ 2: What is the difference between systematic and random error propagation in free energy calculations?

- Systematic Error is a consistent bias in the energy of microstates. When propagated, it corrects by subtracting the Boltzmann-weighted average of these biases from your computed free energy [15].

- Random Error represents the uncertainty in the energy of each microstate. Its propagation provides an uncertainty estimate (error bar) for your final free energy value. Incorporating multiple microstates through sampling reduces this random error [15].

FAQ 3: Why do deep learning models for docking sometimes predict poses with severe steric clashes?

These models are trained on data and may not have internalized fundamental physical constraints like steric exclusion. They can be biased toward poses seen in training data, even when the local geometry is perturbed. This indicates a limitation in their physical reasoning and generalization capability [16].

FAQ 4: My molecular dynamics simulation results are very close to theoretical values, but the statistical error bars are tiny and don't encompass the true value. What's wrong?

This is a classic sign of underestimated statistical error, often due to persistent time correlations in your data. Your sampling interval might be too short. Solutions include:

- Using block averaging analysis to account for correlations.

- Running multiple independent simulations and calculating the standard error of the mean from the final averages of these independent runs [20].

Table 1: Blind Test of Free Energy Calculations for Charged Ligand Binding [21]

| Compound | Experimental ΔGbind (kcal/mol) | Predicted ΔGbind (kcal/mol) | Pose RMSD (Å) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -5.8 | -5.8 ± 0.1 | 1.1 | Correct |

| 2 | -5.8 ± 0.2 | -5.1 ± 0.2 | 0.6 | Correct |

| 3 | -5.1 ± 0.2 | -4.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 | Correct |

| 4 | -4.4 ± 0.2 | -2.2 ± 0.2 | 3.1 | False Negative |

| 5 | -3.4 ± 0.4 | -1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.9 / 0.5 | False Negative |

| 6 | -7.1 ± 0.2 | -4.2 ± 0.3 | 0.6 | False Negative |

| 10 | -4.8 ± 0.2 | -7.9 ± 0.4 | 1.0 | Large Error |

Table 2: Impact of Data Splitting on Model Generalization (Pearson R) [18]

| Data Partitioning Strategy | Model Performance | Generalization Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Random Partitioning | High (Up to 0.70) | Overestimated / Inflated |

| UniProt-Based Partitioning | Significantly Lower | More Realistic |

Table 3: Performance of Co-folding Models on Adversarial Challenges (ATP-CDK2 System) [16]

| Model | Wild-Type RMSD (Ã…) | Binding Site Removal (All Gly) | Binding Site Occlusion (All Phe) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 | 0.2 | Predicts same binding mode | Predicts same binding mode, steric clashes |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | 2.2 | Predicts same binding mode | Ligand remains in site, steric clashes |

| Boltz-1 | Information Missing | Predicts same binding mode | Altered phosphate position |

| Chai-1 | Information Missing | Predicts same binding mode | Ligand remains in site |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Error Propagation Analysis for Free Energy Calculations

Objective: To quantify the propagation of systematic and random errors from a force field into a calculated free energy.

Methodology:

- System Setup: Define your molecular system and the thermodynamic process of interest (e.g., ligand binding).

- Microstate Sampling: Use molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo simulations to generate an ensemble of microstates (conformations) for the system.

- Error Assignment: For each microstate i, estimate its energy error (

δE_i). This can be decomposed into: - Statistical Analysis:

- Calculate the Boltzmann weight for each microstate:

P_i = exp(-βE_i) / Q, whereQis the partition function. - Compute the propagated systematic error:

δA_sys = Σ(P_i * δE_iSys). - Compute the propagated random error:

δA_rand = √[ Σ(P_i * δE_iRand)² ][15].

- Calculate the Boltzmann weight for each microstate:

- Interpretation: Report the final free energy as

A_calculated - δA_sys ± δA_rand, which provides a corrected central value with an uncertainty estimate.

Protocol 2: Robustness Testing for Deep Learning Co-folding Models

Objective: To evaluate whether a deep learning-based structure prediction model adheres to fundamental physical principles.

Methodology:

- Baseline Structure: Select a high-resolution crystal structure of a protein-ligand complex (e.g., CDK2 with ATP).

- Adversarial Challenges: Prepare a series of modified inputs [16]:

- Challenge 1 (Binding Site Removal): Mutate all binding site residues to glycine.

- Challenge 2 (Binding Site Occlusion): Mutate all binding site residues to phenylalanine.

- Challenge 3 (Dissimilar Mutation): Mutate each binding site residue to a chemically dissimilar amino acid (e.g., Asp to Val, Lys to Ala).

- Model Prediction: Input each challenged protein sequence and the original ligand into the co-folding model to predict the complex structure.

- Analysis:

- Calculate the RMSD of the predicted ligand pose against the original crystal structure pose.

- Visually inspect for steric clashes and loss of key interactions.

- A physically robust model should show significant pose changes or displace the ligand in Challenges 2 and 3. A model that persists with the original pose is likely overfit [16].

Diagrams

Error Propagation in Free Energy Calculation

Adversarial Testing for Co-folding Models

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function / Description | Relevance to Error Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment-Based Error Database | A reference containing mean errors (μk) and variances (σ²k) for specific molecular interactions (e.g., H-bonds). | Enables estimation of systematic and random errors for individual microstates prior to ensemble averaging [15]. |

| PDBbind CleanSplit Dataset | A curated version of the PDBbind database with structural similarities and data leakage between training and test sets removed. | Provides a robust benchmark for training and evaluating ML scoring functions, ensuring reported performance reflects true generalization [17]. |

| Block Averaging Scripts | Tools for performing block averaging analysis on correlated time-series data from MD simulations. | Corrects for underestimated statistical errors by accounting for temporal correlations in sampled data [20]. |

| Adversarial Test Suite | A collection of scripts and input files for running binding site mutagenesis and ligand perturbation tests. | Systematically evaluates the physical realism and robustness of deep learning-based structure prediction models [16]. |

| Alchemical Free Energy Software | Programs (e.g., GROMACS with FEP plugins) that calculate free energies by sampling multiple states between endpoints. | Reduces random error in binding affinity predictions by sampling multiple microstates instead of relying on a single endpoint [15] [21]. |

| [D-Phe12,Leu14]-Bombesin | [D-Phe12,Leu14]-Bombesin, MF:C75H114N22O18, MW:1611.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Donepezil hydrochloride | Donepezil Hydrochloride | Donepezil hydrochloride is a potent, selective AChEI for neuroscience research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Modern Parameterization Strategies: Data-Driven and Automated Solutions for Accurate Ligand Modeling

Leveraging High-Quality Quantum Mechanics Datasets for Parameter Training

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key high-quality QM datasets available for training force fields and molecular models?

Several core datasets provide high-quality quantum mechanical calculations essential for training and benchmarking molecular models. The table below summarizes the primary datasets, their scope, and applications. [22] [23]

Table 1: Key Quantum-Mechanical Datasets for Parameter Training

| Dataset Name | Molecular Coverage & Size | Key Properties Calculated | Primary Application in Parameter Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM7/QM7b [22] | ~7,200 small organic molecules (up to 7 heavy atoms). | Atomization energies (QM7), plus 13 properties including polarizability, HOMO/LUMO (QM7b). | Benchmarking model accuracy for molecular property prediction. |

| QM9 [22] | ~134,000 stable small organic molecules (up to 9 heavy atoms CONF). | Geometric, energetic, electronic, and thermodynamic properties. | Training and validating models across a broad chemical space of small molecules. |

| QCell [23] | 525k biomolecular fragments (lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids, ions). | Energy and forces from hybrid DFT with many-body dispersion. | Specialized training of ML force fields for biomolecular systems beyond small molecules and proteins. |

| GEMS [23] | Protein fragments in gas phase and aqueous environments. | Energy and forces from PBE0+MBD. | Developing ML force fields for protein simulations, capturing solvation effects. |

Q2: My molecular dynamics simulations of a drug-like molecule show inaccurate ligand-protein binding energies. Which dataset should I use to refine the ligand parameters?

For drug-like molecules, the QM7-X dataset is a suitable starting point. It contains over 4 million molecular conformations for 4.2 million organic molecules with up to 7 heavy atoms (C, N, O, S, Cl), calculated at the PBE0+MBD level of theory. [23] This dataset provides extensive coverage of conformational space and non-covalent interactions, which are critical for accurately modeling binding. The AQM dataset is also relevant, as it contains nearly 60,000 medium-sized, drug-like molecules. [23]

For troubleshooting, follow this workflow to identify and address the root cause:

Q3: When deriving new force field parameters from QM data, why do my results show high errors on bonded terms (bonds, angles) for biomolecular fragments?

High errors in bonded terms often stem from inadequate representation of the specific chemical environments in biomolecules. General small-molecule datasets (like QM9) may not sufficiently sample the relevant conformational space of complex fragments like glycosidic linkages in carbohydrates or backbone torsions in nucleic acids. [23]

Solution: Incorporate specialized datasets like QCell, which provides deep conformational sampling for fundamental biomolecular building blocks. Its workflow involves extensive conformational sampling using molecular dynamics and conformer-generation tools before high-quality QM calculations, ensuring broad coverage of the relevant torsional and angular potentials. [23] The protocol below ensures robust parameter derivation.

Experimental Protocol: Deriving Bonded Terms from the QCell Dataset

- Fragment Selection: Identify relevant building blocks in the QCell dataset (e.g., disaccharides for carbohydrate parameters, specific lipid head groups). [23]

- Data Extraction: Access the Cartesian coordinates and energy for the thousands of conformers available for your target fragment.

- Parameter Optimization: In your parameter fitting software (e.g., within tools like

fftkorparmed), use the QM-calculated energies as the target. The objective is to find bonded parameters (force constants for bonds, angles, and dihedrals) that, when applied to the same set of conformations, reproduce the QM energy landscape as closely as possible. - Cross-Validation: Validate the newly derived parameters on a separate, held-out set of conformations from the same QCell fragment class to ensure they have not been over-fitted.

Q4: How can I assess if my Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) is overfitting when trained on a limited set of QM data?

Overfitting is a fundamental challenge, especially when the chemical space of your system is not fully represented in the training data. [24] This can be systematically evaluated by monitoring performance across different datasets.

Table 2: Troubleshooting MLFF Overfitting

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low error on training data (e.g., QM9), but high error on validation data from the same set. | Model is too complex and memorizes training examples. | Implement k-fold cross-validation. Use simpler models or stronger regularization. |

| Good performance on general small molecules (QM9) but poor performance on specific biomolecular fragments (e.g., from QCell). | Dataset bias; the training data lacks specific chemical motifs. [23] | Test your model on specialized datasets like QCell or GEMS. Augment training data with targeted fragments from these resources. |

| Performance degrades when simulating large biomolecules, even if small-fragment accuracy is good. | Poor transferability due to lack of long-range or many-body effects in training. | Incorporate larger fragments from datasets like GEMS (top-down) or QCell (solvated dimers/trimers) that capture more complex interactions. [23] |

Q5: What is the recommended high-accuracy QM method used in modern datasets for generating reliable training data?

The consistently recommended method across several modern, high-quality datasets is hybrid density functional theory with many-body dispersion corrections, specifically PBE0+MBD(-NL). [23]

This level of theory is used in the QCell, GEMS, QM7-X, and AQM datasets. [23] It provides a robust balance between accuracy and computational cost by combining the PBE0 hybrid functional, which accurately describes electronic structure, with the MBD method, which captures long-range van der Waals interactions critical for biomolecular assembly and non-covalent binding. Using datasets that share a consistent level of theory facilitates the creation of unified and transferable training sets for MLFFs. [23]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for QM Data-Driven Parameter Training

| Resource / Tool | Function & Role in Parameter Training | Example in Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Composite Datasets | Provide a unified resource covering diverse chemical spaces, ensuring model robustness. | The combination of QCell, QCML, QM7-X, and GEMS covers 41 million data points across 82 elements. [23] |

| Benchmarking Coresets | Standardized sets of molecules for fair and consistent evaluation of model performance against known benchmarks. | The CASF-2016 coreset is used to compare scoring function performance on 285 protein-ligand complexes. [24] |

| Specialized Biomolecular Datasets | Provide quantum-mechanical data for key biomolecular classes (lipids, nucleic acids, carbs) absent from small-molecule sets. | QCell provides 525k calculations for biomolecular fragments like solvated DNA base pairs and disaccharides. [23] |

| Consistent QM Theory Level | Using data computed at the same level (e.g., PBE0+MBD) avoids introducing systematic biases when combining data sources for training. | PBE0+MBD(-NL) is the common theory level for QCell, GEMS, QM7-X, and AQM. [23] |

| Mardepodect | Mardepodect, CAS:1292799-56-4, MF:C25H20N4O, MW:392.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bifeprofen | Bifeprofen | Bifeprofen for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Automated Parametrization

Q1: My automated parametrization run produces molecules with incorrect partitioning behavior (log P values). What could be wrong? This is often due to issues with the fitness function or target data. First, verify that the experimental log P value you are using as a target is accurate and measured under conditions relevant to your simulation [25]. Second, check the implementation of the free energy calculation within your pipeline. The Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) method is recommended for accuracy, as direct calculation of solvation free energies can have large errors [25]. Ensure your training systems (water and octanol boxes) are correctly built and equilibrated.

Q2: After parametrization with CGCompiler, my small molecule does not embed correctly in the lipid bilayer. How can I fix this? Reproducing atomistic density profiles in lipid bilayers is a complex target. If the insertion depth or orientation is wrong, your parametrization may be overly reliant on the log P value alone [25]. Review the weight given to the density profile target in your fitness function versus the weight for the log P target. It may be necessary to increase the influence of the membrane-specific data to better capture the correct orientation and insertion behavior [25].

Q3: I am getting a "Residue not found in residue topology database" error when trying to generate a topology for a novel ligand. What are my options? This is a common error indicating that the force field does not have a pre-defined entry for your molecule [26]. Your options are:

- Use an Automated Parametrization Tool: This is the ideal solution. Tools like CGCompiler are designed specifically for this purpose, automating the process of creating parameters for molecules not in the database [25].

- Manual Parametrization: If automation fails, you must parameterize the molecule yourself. This involves defining atom types, charges, and bonded parameters, which is a complex and expert-level task [26].

- Find Existing Parameters: Search the primary literature or other force field databases for a compatible topology file you can incorporate into your system [26].

Q4: What are the best practices for validating an automatically generated coarse-grained model? Automated parametrization requires rigorous validation. Do not rely solely on the optimization algorithm's fitness score.

- Compare with Atomistic Simulations: The gold standard is to compare the behavior of your coarse-grained model against atomistic reference simulations, not just on the optimization targets but also on other properties [25].

- Use Experimental Data: If available, validate against experimental data that was not used in the parametrization, such as membrane permeability or binding affinity data [25] [27].

- Perform MD Refinement: Run molecular dynamics simulations, such as spontaneous membrane insertion assays, to visually and quantitatively check if the molecule behaves as expected [27].

Q5: Why does my ligand act as a "false positive" in docking studies, and can better parametrization help? False positives—ligands that dock well but fail experimentally—can arise from many factors, including poor parametrization [27]. An inaccurate force field can lead to incorrect ligand conformation, flexibility, or interaction energies. Using an automated, high-fidelity parametrization pipeline that reproduces key properties like log P and membrane density profiles can generate more realistic ligand models [25] [27]. This improves the reliability of subsequent docking and MD simulations by ensuring the ligand's physicochemical behavior is correct.

Troubleshooting Common Parametrization Errors

The following table outlines specific errors, their likely causes, and solutions relevant to automated molecular parametrization workflows.

| Error / Issue | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect log P value | Inaccurate experimental target data or errors in free energy calculation [25]. | Verify experimental values; implement the MBAR method for more robust free energy calculations [25]. |

| Poor membrane insertion | Over-reliance on bulk partitioning (log P) without membrane-specific targets [25]. | Add atomistic density profiles from lipid bilayers to the fitness function to guide orientation and depth [25]. |

| "Residue not found in database" | The force field lacks parameters for your novel small molecule or residue [26]. | Use an automated parametrization pipeline like CGCompiler instead of standard topology builders [25] [26]. |

| Unphysical molecular shape/volume | Bonded parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals) are poorly optimized. | Include structural targets like Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) in the optimization to capture overall shape and volume [25]. |

| False positives in docking | Oversimplified scoring functions and incorrect ligand representation in simulations [27]. | Refine docked complexes with MD simulations and use MM-PBSA/MM-GBSA for binding affinity; ensure ligands are accurately parametrized [27]. |

Experimental Protocol: Automated Parametrization with CGCompiler

This protocol details the steps for parametrizing a small molecule using the CGCompiler approach, which uses a mixed-variable particle swarm optimization (PSO) guided by experimental and atomistic simulation data [25].

1. Initial Mapping and Setup

- Input: Obtain the atomistic structure of the small molecule (e.g., dopamine, serotonin).

- Mapping: Define the coarse-grained mapping by grouping multiple heavy atoms into single interaction sites (beads). This can be done manually or using an automated tool like Auto-Martini [25].

- System Preparation: Create the necessary training systems for simulation:

- A box of water molecules.

- A box of octanol molecules.

- A hydrated lipid bilayer system.

2. Defining the Fitness Function and Targets The core of the automated optimization is a fitness function that evaluates how well a candidate parametrization reproduces key properties. The primary targets should be:

- Experimental log P Value: The octanol-water partition coefficient is a primary indicator of hydrophobicity [25].

- Atomistic Density Profiles: Reference density data for the molecule within a lipid bilayer from detailed atomistic simulations, which captures correct orientation and insertion [25].

- Structural Properties: Such as the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), averaged from high-sampling atomistic simulations, to guide overall molecular shape [25].

3. Running the Optimization with CGCompiler

- Algorithm: The CGCompiler package employs a mixed-variable PSO to simultaneously optimize both discrete variables (selection of bead types from the Martini force field) and continuous variables (bond lengths, angles, etc.) [25].

- Workflow: The algorithm iteratively:

- Generates candidate parameters.

- Runs MD simulations of the training systems using GROMACS.

- Calculates the fitness score by comparing simulation results to the targets.

- Updates the candidate parameters based on the swarm's knowledge.

- Repeats until convergence criteria are met [25].

4. Validation

- Independent Simulation: Use the final parametrized model in a new simulation (e.g., of the molecule interacting with a different membrane type or a protein) that was not part of the training set.

- Compare to Data: Validate the model's behavior against additional experimental data or higher-level simulation results that were not used in the parametrization process.

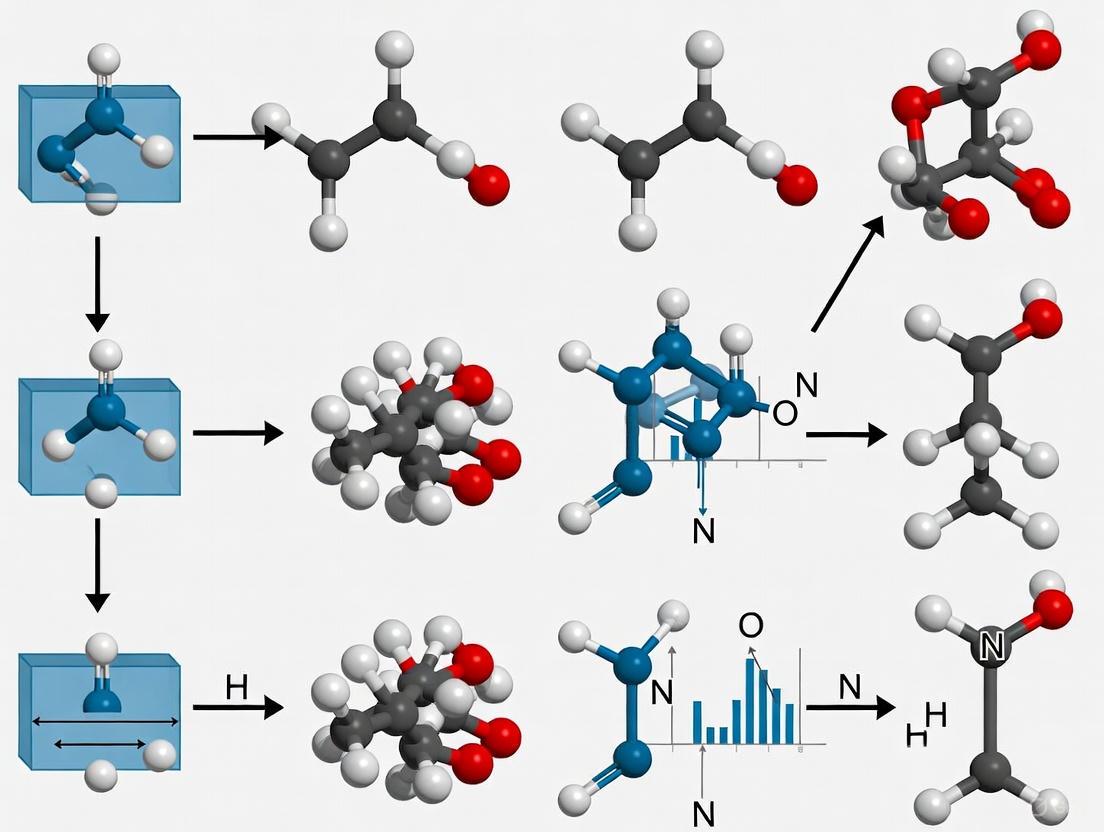

Workflow Visualization: Automated Parametrization Pipeline

The diagram below illustrates the automated parametrization pipeline, from initial input to final validated model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software tools and methods essential for developing and running automated parametrization pipelines.

| Item / Reagent | Function in Automated Parametrization |

|---|---|

| CGCompiler | A Python package that automates high-fidelity parametrization within the Martini 3 force field using a mixed-variable particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm [25]. |

| GROMACS | The molecular dynamics simulation engine used by CGCompiler to run the coarse-grained simulations and calculate properties for the fitness function [25]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | An evolutionary algorithm that efficiently explores the complex, multidimensional parameter space (both discrete bead types and continuous bonded parameters) to find the optimal solution [25]. |

| Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) | A robust method implemented to accurately compute the free energy of transfer for calculating partition coefficients (log P), overcoming inaccuracies from direct solvation free energy calculations [25]. |

| Auto-Martini | An automated mapping tool that provides a valuable starting point for the coarse-grained mapping and initial parametrization, which can then be refined by CGCompiler [25]. |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | A key metric used as a target in the fitness function to ensure the coarse-grained model captures the overall molecular shape and volume of the atomistic reference [25]. |

| 4-Hydroxypiperidine-1-carboximidamide | 4-Hydroxypiperidine-1-carboximidamide |

| Schisanhenol B | Schisanhenol B |

The Rise of Graph Neural Networks for End-to-End Force Field Parameter Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My MD simulation fails with "Atom does not have a type" for a ligand. How can a GNN-based force field help?

Traditional parameterization tools rely on look-up tables for standard atom types. This error occurs when a non-standard ligand contains chemical environments not in these tables [28]. GNN-based force fields like ByteFF or Espaloma address this by predicting parameters end-to-end from molecular structure, eliminating dependency on pre-defined atom type libraries [5]. The GNN intelligently infers parameters for any given ligand topology by learning from quantum mechanics data.

Q2: How reliable are GNN-predicted force fields for simulating complex molecular interactions in drug discovery?

GNN force fields demonstrate high accuracy across expansive chemical spaces. ByteFF, for instance, was trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragments and 3.2 million torsion profiles, achieving state-of-the-art performance in predicting geometries, torsional energies, and conformational forces [5]. Their reliability stems from:

- Data-Driven Parameterization: Learns directly from high-quality QM data (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level of theory), capturing subtle interactions often missed by classical models [5].

- Solid-State Generalizability: GNNs trained on simple systems (e.g., LJ Argon) can successfully predict properties like phonon density of states and vacancy migration rates in unseen solid-state configurations [29].

Q3: What are the primary sources of error, and how can I quantify uncertainty when using a GNN force field?

Errors can arise from systematic and random sources [30]:

- Systematic Errors: Inaccuracies from the underlying QM reference data, the GNN model's architectural limitations, or its training dataset's coverage [30] [5].

- Random (Stochastic) Errors: Intrinsic chaos in MD simulations, leading to noise in observable predictions [30].

For uncertainty quantification, implement ensemble methods:

- Run multiple MD simulations (ensembles) using models with varied initializations or trained on different data subsets.

- Analyze the statistical variance of your results (e.g., binding free energies, diffusion rates) to estimate prediction uncertainty [30]. This is crucial for making reliable, actionable decisions in drug discovery.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Ligand Conformations and Torsional Profiles

Issue: Simulations using GNN-predicted parameters produce unrealistic ligand conformations or incorrect torsional energy profiles, compromising binding affinity predictions.

Diagnosis and Solution: This often indicates insufficient coverage of relevant chemical space in the GNN's training data or errors in the torsion parameter prediction.

- Step 1: Validate Torsion Predictions. Isolate the problematic torsion dihedral and calculate its energy profile using the GNN force field. Compare it against a reference quantum mechanics (QM) calculation and the output of traditional force fields (e.g., OPLS3e).

- Step 2: Curate Targeted Training Data. If a discrepancy is found, generate high-quality QM data (torsion scans and optimized geometries) for molecular fragments that specifically cover the underperforming chemical motif [5].

- Step 3: Model Retraining. Fine-tune the GNN force field on this new, curated dataset to improve its performance for the specific chemical environment [5].

Problem: Low Simulation Reliability and Reproducibility

Issue: Results from MD simulations using the GNN force field lack reproducibility, making it difficult to draw reliable scientific conclusions.

Diagnosis and Solution: This is a fundamental challenge in MD, often stemming from the chaotic nature of dynamics and a lack of rigorous UQ [30].

- Step 1: Implement Ensemble Simulations. Do not rely on a single, long simulation. Instead, run an ensemble of multiple concurrent, shorter simulations starting from different initial conditions [30].

- Step 2: Perform Statistical Analysis. For your quantity of interest (e.g., root-mean-square deviation, radius of gyration), calculate the mean and standard deviation across all replicas in the ensemble. A large variance indicates high uncertainty.

- Step 3: Report Results with Error Bars. Always present simulation results with confidence intervals (e.g., mean ± standard deviation) derived from the ensemble analysis to provide a measure of reliability [30].

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

This section provides methodologies for validating GNN force field performance, which is critical before applying them to production drug discovery projects.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Solid-State Properties

Purpose: To evaluate the transferability of a GNN force field to solid-state phenomena not explicitly included in its training data, such as defects and finite-temperature effects [29].

Workflow:

- System Preparation: Construct a perfect face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal and an imperfect crystal containing a mono-vacancy.

- Phonon Density of States (PDOS) Calculation:

- Vacancy Migration Analysis:

Protocol 2: Evaluating Force Field Chemical Accuracy

Purpose: To rigorously assess the accuracy of a GNN-predicted force field across a diverse chemical space [5].

Workflow:

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a benchmark set of molecules not seen during the GNN's training. This set should have high-quality reference QM data.

- Property Calculation:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize molecular geometries using the GNN force field and compare the resulting bond lengths and angles against reference QM-optimized structures [5].

- Torsion Profile Scans: Perform single-point energy calculations along specific torsion dihedrals and plot the energy profile against QM reference data [5].

- Conformational Energy & Forces: For a set of diverse conformers, compute the single-point energy and atomic forces for each, comparing them to QM references [5].

- Error Metrics: Quantify performance using standard metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for energies and forces.

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Benchmarking GNN Force Field Accuracy on Molecular Properties [5]

| Benchmark Metric | GNN Force Field (ByteFF) | Traditional MMFF (GAFF) | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Length MAE (Ã…) | 0.005 | 0.008 | QM (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) |

| Angle MAE (degrees) | 0.7 | 1.1 | QM (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) |

| Torsion Energy MAE (kcal/mol) | < 0.5 | ~1.0 | QM (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) |

| Conformational Energy RMSE (kcal/mol) | Low (~0.5) | Higher | QM (B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) |

Table 2: GNN Application in Other Scientific Domains

| Application Domain | Key Achievement | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Superconducting Quantum Circuit Design [31] | Used GNNs for scalable parameter design to mitigate quantum crosstalk. | For an ~870-qubit circuit: 51% lower error and time reduced from 90 min to 27 sec. |

| Solid-State Property Prediction [29] | GNN-MLFF trained on LJ Argon accurately predicted PDOS and vacancy migration in unseen configurations. | Good agreement with reference data for perfect and imperfect crystal properties. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for GNN Force Field Development

| Item Name | Function & Purpose | Relevance to GNN Force Fields |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Model | A symmetry-preserving, edge-augmented molecular GNN. | Core architecture that maps molecular graph to force field parameters, ensuring permutational and chemical invariance [5]. |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Dataset | A large, diverse dataset of molecular geometries, Hessians, and torsion profiles. | High-quality training data generated at levels like B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP. Critical for model accuracy and chemical space coverage [5]. |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer [5] | A geometry optimizer for QM calculations. | Used to generate optimized molecular structures and Hessian matrices for the training dataset [5]. |

| Antechamber [28] | A tool for generating force field parameters for organic molecules. | A traditional baseline tool; its failures highlight the need for modern GNN approaches [28]. |

| Spectral Energy Density (SED) [29] | A method for computing phonon properties from MD trajectories. | Used for validating GNN force fields on finite-temperature solid-state properties [29]. |

| Sematilide | Sematilide|High-Purity Research Compound|RUO | High-purity Sematilide, a class III antiarrhythmic agent. Explore its applications in cardiac ion channel research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Methodology Visualization

GNN Force Field Parameter Prediction Workflow

GNN Force Field Training Data Pipeline

A Practical Guide to Troubleshooting and Optimizing Ligand Parameters in MD Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My free energy calculations show high hysteresis between forward and reverse transformations. What could be the cause? High hysteresis in results often stems from inconsistent hydration environments between the different states of your simulation. If the ligand in the forward direction samples a different water structure than the starting ligand in the reverse direction, the calculated energies will not agree. This can also be a sign of insufficient sampling, where the system has not been simulated long enough to explore all relevant conformational states [32].

Q2: My ligand is predicted to bind strongly in docking but fails in experimental validation. What are the common computational pitfalls? This is a classic case of a false positive. Common computational causes include:

- Oversimplified Scoring Functions: Many docking scoring functions over-rely on shape complementarity and underestimate the significant entropic penalties and desolvation costs associated with binding [27].

- Rigid Receptor Assumption: Proteins are flexible. Docking to a single, rigid protein conformation may allow the ligand to bind to a state that is not physiologically relevant or stable in solution [27].

- Incorrect Solvent Modeling: Implicit solvent models can fail to capture key, water-mediated hydrogen bonds. A ligand predicted to displace a tightly bound water molecule may not do so in reality, leading to a poor experimental binding affinity [27].

Q3: How can I tell if my force field is inadequately describing my ligand? A major red flag is the poor description of ligand torsion angles. If the force field lacks accurate parameters for specific chemical moieties in your ligand, it can lead to unrealistic conformational behavior and skewed energy calculations. This often manifests as the ligand adopting an unphysical pose or geometry during simulation [32].

Q4: What does it mean if my Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations have a consistent off-set error compared to experiment? A systematic off-set error in ABFE often points to an over-simplistic description of the binding process. The standard ABFE cycle typically does not account for conformational changes in the protein or changes in the protonation states of binding site residues that occur upon ligand binding. This unaccounted-for energy difference translates to a consistent error in the calculated ΔG [32].

Q5: Are there specific challenges when modeling charged ligands? Yes, perturbations involving formal charge changes are inherently less reliable and require special care. The electrostatic interactions are long-range and require more simulation time to converge properly compared to perturbations between neutral molecules [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Binding Affinity Predictions due to Force Field Limitations

- Symptoms: Poor correlation between calculated and experimental binding free energies, especially for a series of similar ligands; unphysical ligand conformations in the binding site.

- Diagnosis: This often occurs when the standard force field lacks specific parameters for unique torsions or chemical groups in your ligands [32].

- Solution:

- Identify Problematic Torsions: Analyze the ligand's chemical structure for motifs not commonly found in standard biomolecular force fields.

- Parameter Optimization: Run quantum mechanics (QM) calculations to derive improved torsion parameters for the identified moieties.

- Incorporate and Validate: Integrate the new parameters into your simulation and validate them against known experimental data or higher-level calculations [32].

Issue 2: Poor Convergence in Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

- Symptoms: High hysteresis between forward and reverse transformations; large standard errors in the calculated free energy difference.

- Diagnosis: The system is not sufficiently sampled along the alchemical pathway (lambda dimension) or in conformational space [33] [32].

- Solution:

- Automate Lambda Scheduling: Use tools that employ short exploratory calculations to automatically determine the optimal number and spacing of lambda windows, ensuring efficient sampling [32].

- Extend Simulation Time: For particularly slow degrees of freedom or for transformations involving charge changes, simply running longer simulations is often necessary to achieve convergence [32].

- Employ Enhanced Sampling: For complex systems with high energy barriers, consider using enhanced sampling methods like Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD) or Metadynamics to improve phase space exploration [33].

Issue 3: False Positives from Molecular Docking

- Symptoms: Ligands rank highly in virtual screening but show no activity in subsequent assays.

- Diagnosis: The initial docking predictions are based on simplified models that ignore critical aspects of molecular recognition [27].

- Solution:

- Refine with MD: Use short Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to relax the docked pose and account for protein flexibility and solvation.

- Recalculate with Refined Methods: Apply more rigorous, but computationally expensive, methods like MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA on frames from the MD trajectory to get a better estimate of the binding affinity [33] [27].

- Validate Experimentally: Always confirm key computational predictions with experimental techniques such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Refining Docking Poses with MD and MM/GBSA

This protocol is used to validate and rescore top hits from a virtual screen to reduce false positives [27].

- System Preparation: Obtain the protein-ligand complex from docking. Add missing hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and embed the complex in a solvation box.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a brief energy minimization to remove any steric clashes introduced during the setup.

- Equilibration: Run a short MD simulation (e.g., 100-200 ps) in the NVT and NPT ensembles to equilibrate the solvent and ions around the protein-ligand complex.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained MD simulation (e.g., 10-100 ns) at constant temperature and pressure.

- Trajectory Analysis: Extract snapshots evenly from the production run (e.g., every 100 ps).

- MM/GBSA Calculation: Calculate the binding free energy for each snapshot using the MM/GBSA method. The final binding affinity is reported as the average over all snapshots [33].

Table: Key Parameters and Recommended Values for MM/PB(GB)SA Calculations

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Value / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Dielectric Constant | Represents the protein interior's dielectricity. | A value of 1.0-4.0 is typical for proteins; for membrane proteins, a value of 20.0 has been recommended [33]. |

| Membrane Dielectric Constant | For simulations involving membrane proteins. | A value of 7.0 has been suggested for accuracy [33]. |

| Interaction Entropy (IE) | Method to calculate entropy. | Can improve accuracy for protein-ligand systems but may reduce it for protein-protein interactions; testing is required [33]. |

| Salt Concentration | Ionic strength of the solvent. | Typically set to 0.1-0.15 M to mimic physiological conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Context of Ligand Parameterization |

|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software | Used to generate high-quality electronic structure data for deriving improved force field parameters, especially for ligand torsions not well-described by standard force fields [32]. |

| Open Force Field (OpenFF) Initiative Parameters | A continuously updated set of accurate, chemically aware force field parameters specifically designed for modeling drug-like small molecules in the context of biomolecular simulations [32]. |

| Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) Methods | A sampling technique used to ensure the binding site is correctly hydrated by allowing water molecules to be inserted and deleted during the simulation, addressing hydration-related hysteresis [32]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms (e.g., GaMD, MetaD) | Advanced simulation methods that accelerate the exploration of conformational space and the crossing of energy barriers, providing better convergence for binding free energy and kinetics calculations [33]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Troubleshooting Workflow for Energy Instabilities

Protocol for Validating Docking Poses

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the reproduction of experimental log P values so crucial in small molecule parametrization?

Reproduction of experimental octanol-water partition coefficients (log P) is crucial because they serve as primary indicators of a compound's hydrophobicity and membrane permeability. This makes them essential tools for assessing a compound's potential as a drug candidate. Given that the octanol-water partition coefficients of common small molecules have been well experimentally determined, reproducing these coefficients represents the primary goal in guiding the parametrization of small molecules within coarse-grained models like Martini 3 [34].

Q2: My coarse-grained model reproduces log P well but shows incorrect membrane insertion. What additional experimental data should I use for optimization?

When log P values alone don't yield accurate membrane behavior, incorporating atomistic density profiles within lipid bilayers provides a complementary and membrane-specific target for parametrization. Unlike bulk partitioning, density profiles investigate the spatial distribution and orientation of molecules across the heterogeneous lateral membrane interface directly, capturing interactions with different chemical groups within the lipid and the insertion depth within the bilayer. Incorporating such information allows coarse-grained models to more precisely account for additional structural and electrostatic effects that are often absent when optimizing solely against octanol-water partitioning free energies [34].

Q3: What are the advantages of automated parametrization approaches like CGCompiler over manual parameter tweaking?

Automated parametrization using approaches like CGCompiler with mixed-variable particle swarm optimization provides significant advantages by overcoming the inherent dependency between nonbonded and bonded interactions that makes manual parametrization frustrating and tedious. This method performs multiobjective optimization that matches provided targets derived from atomistic simulations as well as experimentally derived targets, thereby facilitating more accurate and efficient parametrization without the need for manual tweaking of parameters [34].

Q4: How can I validate that my optimized parameters produce physically realistic molecular behavior beyond matching target values?

Beyond matching target log P and density profiles, including Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) as an objective provides a useful guide for capturing the overall molecular shape and solvent-exposed surface during parametrization. Due to the reduced resolution of coarse-grained models, perfect agreement with atomistic SASA is not expected, but it serves as a valuable metric for ensuring physical realism in molecular shape and volume [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Correlation with Experimental Partition Coefficients

Problem: Your coarse-grained model fails to reproduce experimental log P values, indicating inaccurate hydrophobicity representation.

Solution:

- Implement Free Energy Calculations: Utilize the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) method to accurately compute the necessary free energy of transfer for determining partition coefficients [34].

- Employ Chemical Perturbation: Implement a chemical perturbation scheme utilizing a fixed reference topology with a predetermined value to calculate transfer free energies for newly parametrized molecules according to the equation: ΔG{trans}^{new} = ΔG{trans}^{ref} + (ΔG{new} - ΔG{ref}) where ΔG_{trans}^{ref} represents the known reference free energies of a predefined reference molecule [34].

- Verify Force Field Compatibility: Ensure nonbonded interaction types are properly optimized for your specific molecule class, as standard building blocks may not capture unique chemical features.

Prevention: Always include multiple reference compounds with known log P values in your parametrization workflow to ensure force field transferability across similar chemical spaces.

Issue 2: Inaccurate Membrane Density Profiles Despite Correct log P

Problem: Your model matches experimental log P values but shows incorrect spatial distribution in lipid bilayers.

Solution:

- Expand Optimization Targets: Simultaneously optimize against both octanol-water partitioning free energies and atomistic density profiles within lipid bilayers [34].

- Analyze Molecular Orientation: Examine the density profiles of individual beads corresponding to the orientation of molecules in the membrane, enabling more precise parametrization of the local molecular chemistry within molecules that are not uniquely determined by log P values alone [34].

- Incorporate SASA Metrics: Include Solvent Accessible Surface Area as an additional optimization target to better capture molecular shape and volume aspects [34].

Prevention: During parametrization, always run preliminary membrane simulations to identify orientation issues early rather than relying solely on bulk partitioning properties.

Issue 3: Structural Instability or Unphysical Conformations

Problem: Optimized parameters produce molecules with unstable structures or unphysical conformational sampling.

Solution: