Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Research and Drug Discovery

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, providing critical insights into biomolecular structural stability, conformational changes, and ligand-binding interactions.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, providing critical insights into biomolecular structural stability, conformational changes, and ligand-binding interactions. This article offers a comprehensive exploration of RMSD, from its mathematical foundations and calculation methodologies to its advanced applications in drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we detail practical protocols for RMSD analysis using common tools like GROMACS and Python's MDAnalysis, address common pitfalls and optimization strategies, and validate its role through case studies in structure-based drug design. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the expertise to leverage RMSD effectively, enhancing the reliability and predictive power of their computational research.

What is RMSD? Understanding the Core Concepts and Mathematical Foundation

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a foundational metric in structural biology and computational chemistry, serving as a standard measure for quantifying the average distance between the atoms of superimposed molecular structures [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, RMSD provides a crucial numerical representation of structural similarity or dissimilarity, enabling objective comparisons between different molecular conformations [2]. In the context of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, RMSD is indispensable for evaluating structural stability, flexibility, and conformational changes of biomolecules over time [3]. By tracking how much a structure deviates from a reference state—such as an initial crystal structure or an average conformation—RMSD offers insights into protein folding, ligand binding, and functional dynamics that are essential for rational drug design [3] [1].

The calculation of RMSD involves a specific mathematical approach that measures the atomic positional differences after optimal structural alignment. The standard formula for calculating RMSD between two sets of atomic coordinates is expressed as:

RMSD = √(1/N ∑(vi - wi)²) [1]

where N represents the number of atoms being compared, vi represents the coordinates of atom i in the target structure, and wi represents the coordinates of the corresponding atom in the reference structure [1]. The result is expressed in length units, typically Ångströms (Å), where 1 Å equals 10⁻¹⁰ meters [1]. This measurement is most commonly applied to backbone atoms (C, N, O, Cα) or sometimes exclusively to Cα atoms to characterize protein structural changes while minimizing noise from highly flexible side chains [1].

Fundamental Principles and Calculation Methods

Core Mathematical Foundation

The RMSD calculation process involves two critical steps: structural superposition followed by deviation calculation. The superposition step involves finding the optimal rotation and translation that minimizes the RMSD between two structures through algorithms such as the Kabsch algorithm or quaternion-based methods [1]. This alignment ensures that the calculated RMSD reflects genuine structural differences rather than arbitrary rotational or translational orientations [2].

Once aligned, the algorithm calculates the Euclidean distance between each pair of corresponding atoms, squares these distances, sums them, divides by the number of atoms, and finally takes the square root to arrive at the RMSD value [2]. Advanced methods may incorporate weighted calculations where different atoms contribute differently to the final RMSD based on their importance or uncertainty [2].

Reference and Fit Selection Strategies

A critical consideration in RMSD analysis is selecting which atoms to use for structural fitting versus which atoms to measure for deviation. These selections do not need to be identical [4]. For example, a protein is typically fitted on backbone atoms (N, Cα, C) to establish a common frame of reference, while the RMSD can be computed for either the backbone alone or the entire protein structure [4]. This approach allows researchers to focus on specific aspects of structural conservation or variation.

Additionally, instead of always comparing structures to an initial reference (e.g., a crystal structure at time t=0), researchers can calculate RMSD between structures at different time points (t₁ and t₂ = t₁ - τ) to analyze structural mobility as a function of time separation [4]. When RMSD is calculated as a function of both t₁ and t₂, it generates a matrix that provides a comprehensive graphical interpretation of structural evolution throughout a trajectory, clearly highlighting structural transitions when they occur [4].

Alternative RMSD Formulations

Beyond the standard atomic position RMSD, alternative formulations offer complementary structural insights. The fit-free RMSD method implemented in tools like gmx rmsdist calculates deviations based on inter-atomic distances rather than absolute positions:

RMSD(t) = [1/N² ∑∑‖rij(t) - rij(0)‖²]^(1/2) [4]

where r_ij represents the distance between atoms i and j at time t compared to time 0 [4]. This approach eliminates the need for structural alignment and can be particularly valuable for analyzing structural changes in systems where defining a common reference frame is challenging.

Specialized domain-specific RMSD approaches have also been developed, such as the 7x7 RMSD matrix method specifically designed for comparing the characteristic seven transmembrane bundle structures of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) [5]. Unlike conventional RMSD that produces a single value, this method generates a 7×7 matrix containing 49 parameters that reveal changes in the relative orientations of the seven transmembrane helices, providing significantly more detailed information about helix movements during receptor activation [5].

Applications in Drug Development and Molecular Dynamics

Stability Assessment and Conformational Analysis

In molecular dynamics simulations, RMSD serves as a primary metric for assessing the stability of biomolecular systems and identifying conformational changes [3]. By tracking RMSD over simulation time, researchers can determine when a structure has stabilized, identify major conformational transitions, and validate the reliability of their simulations [3]. Low RMSD values (typically < 1-2 Å) indicate structural stability, where the molecule maintains its overall conformation relative to the reference structure [3]. Moderate RMSD values (1-3 Å) suggest structural flexibility but maintenance of the overall fold, while higher RMSD values (>3 Å) often indicate substantial conformational changes or potential unfolding events [3].

Table 1: Interpretation of RMSD Values in Protein Analysis

| RMSD Range (Å) | Structural Interpretation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 | Very high similarity | Same protein in slightly different conformational states or under different experimental conditions |

| 1.0 - 3.0 | Moderate structural differences | Conformational changes induced by ligand binding, pH changes, or other environmental factors |

| > 3.0 | Substantial structural differences | Potentially different protein folds, major conformational changes, or poor structural alignment |

Role in Drug Discovery Workflows

RMSD analysis plays multiple critical roles throughout the drug discovery pipeline:

- Target Identification and Validation: RMSD is used to compare structural models derived from different experimental methods or to assess the quality of homology models against known structures [2].

- Ligand Binding Analysis: In protein-ligand complexes, RMSD calculations for both the receptor and ligand help evaluate binding stability and identify conformational changes induced by molecular recognition [6].

- Structure-Based Drug Design: During virtual screening and lead optimization, RMSD measurements help classify binding modes and assess the structural conservation of binding sites across related targets [7].

- Solubility and ADME Prediction: Recent research has identified RMSD as one of seven key MD-derived properties highly effective in predicting aqueous solubility of drug candidates when combined with machine learning approaches [8].

The integration of RMSD analysis with other computational and experimental techniques—including omics technologies, bioinformatics, and network pharmacology—has created powerful multidisciplinary frameworks for modern cancer drug development [9]. These integrated approaches systematically leverage RMSD and other molecular dynamics parameters to identify novel therapeutic targets, optimize drug candidates at the molecular level, and develop personalized treatment strategies [9].

Experimental Protocols

RMSD Calculation Using GROMACS

For MD simulations using GROMACS, the following protocol enables efficient RMSD calculation and analysis:

Step 1: Run RMSD Analysis

This command calculates RMSD over the entire trajectory stored in trajectory.xtc using the structure in protein.tpr as a reference and outputs the results to rmsd.xvg [3].

Step 2: Select Atom Group When prompted, select the appropriate atom group for analysis. For protein stability assessment, the backbone atoms (typically option 4) provide the most meaningful results by excluding highly flexible side chains [3].

Step 3: Visualize RMSD Profile

Visualization allows researchers to identify stabilization periods, conformational transitions, and overall simulation stability [3].

RMSD Calculation Using Python MDAnalysis

For custom analysis or integration with other computational workflows, Python's MDAnalysis package provides flexible RMSD calculation capabilities:

Step 1: Install MDAnalysis

Step 2: Compute and Visualize RMSD

This script generates a temporal RMSD profile that can be analyzed for structural stability and transitions [3].

Specialized Protocol: 7x7 RMSD Matrix for GPCRs

For advanced applications involving GPCR structures, the 7x7 RMSD matrix protocol provides detailed insights into helix movements:

Step 1: Structure Preparation

- Obtain the reference and target GPCR structures (typically in PDB format)

- Ensure consistent residue numbering and alignment of the seven transmembrane helices

Step 2: Matrix Calculation

- For each TM helix (i = 1 to 7), fit only that specific helix between reference and target structures

- For each fit, calculate RMSD for all seven TM helices (j = 1 to 7)

- Populate the 7×7 matrix where element (i,j) contains the RMSD of helix j when helix i is fitted

Step 3: Data Interpretation

- Analyze diagonal elements to identify conformational changes within individual helices

- Examine off-diagonal elements to detect relative helix movements and changes in orientation within the 7TM bundle

- Compare matrices between different functional states (e.g., inactive vs. active) to quantify activation-associated structural changes [5]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RMSD Analysis

| Reagent/Software | Function in RMSD Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation suite with built-in RMSD analysis tools | Calculating RMSD from MD trajectories of proteins, membranes, and nucleic acids |

| MDAnalysis | Python library for trajectory analysis | Custom RMSD analysis scripts and integration with machine learning workflows |

| Amber with χOL3 | RNA-specific force field for MD simulations | RMSD analysis of RNA structures and refinement of RNA models |

| PyMOL/ChimeraX | Molecular visualization software | Visual inspection of aligned structures and validation of RMSD calculations |

| CGenFF Suite | MD simulation utilities for proteins and ligands | Ligand RMSD calculations and protein-ligand complex stability assessment |

| ANM (Anisotropic Network Model) | Efficient conformational sampling tool | Generating plausible conformers for ensemble docking and RMSD-based clustering |

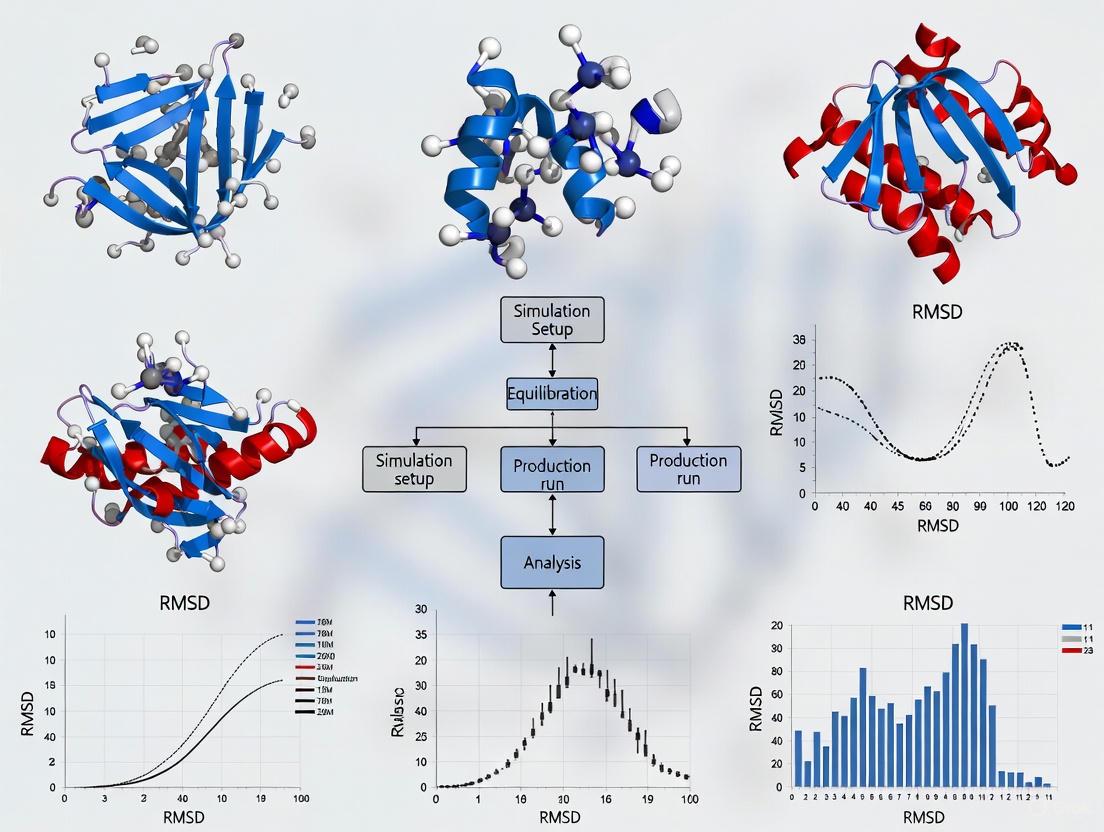

Workflow Visualization

RMSD Analysis Workflow

Advanced Applications and Guidelines

Practical Considerations for RMSD Interpretation

Effective application of RMSD analysis requires careful consideration of several factors:

- Starting Model Quality: Research indicates that MD simulations (and consequent RMSD analysis) provide the most value when applied to already high-quality starting models. For RNA structures, short simulations (10-50 ns) can modestly improve good models but rarely benefit poor models, which often deteriorate further [10].

- Simulation Length: Longer simulations (>50 ns) may induce structural drift and reduce fidelity to the experimental structure. Shorter, targeted simulations often provide more reliable refinement [10].

- Comparative Analysis: When comparing multiple structures or conformations, ensure consistent selection of reference structures, fitting atoms, and calculation parameters to enable valid comparisons.

Emerging Applications in Drug Development

Recent advances have expanded RMSD applications in pharmaceutical research:

- Machine Learning Integration: RMSD values serve as important features in machine learning models predicting drug properties such as aqueous solubility, with studies demonstrating that RMSD combined with other MD-derived properties can achieve high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.87) for solubility prediction [8].

- Ensemble Docking: RMSD-based clustering of MD trajectories helps identify representative conformations for ensemble docking, accounting for receptor flexibility in drug screening [7].

- Multi-Scale Modeling: Combined all-atom/coarse-grained approaches use RMSD to validate mixed-resolution models and ensure structural integrity while reducing computational costs for large systems [7].

Table 3: Comparison of RMSD Variants and Applications

| RMSD Type | Calculation Method | Best Suited Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Atomic RMSD | Optimal superposition of atomic coordinates | Protein folding studies, general stability assessment | Intuitive interpretation, wide software support |

| Backbone RMSD | Superposition using only backbone atoms (Cα, C, N, O) | Protein structural comparison, dynamics of globular domains | Reduced noise from flexible side chains |

| Ligand RMSD | Measurement of ligand heavy atom positions | Binding mode stability, conformational selection in drug binding | Direct assessment of ligand behavior in binding site |

| Fit-free RMSD | Based on interatomic distances without superposition | Systems where alignment is problematic, distance-based similarity | Avoids alignment artifacts, complementary perspective |

| 7x7 Matrix RMSD | Successive fitting of individual TM helices in GPCRs | Quantifying helix movements in membrane proteins | Detailed mechanistic insights into relative helix orientations |

RMSD remains an indispensable quantitative measure in structural biology and drug discovery, providing critical insights into molecular stability, conformational dynamics, and structural relationships. Its applications span from basic structural validation to advanced drug design workflows, where it integrates with multidisciplinary approaches including MD simulations, machine learning, and experimental validation. As computational methods continue to evolve, RMSD maintains its fundamental role as a robust, interpretable metric for quantifying structural deviations—a cornerstone of molecular dynamics analysis and rational drug development.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a foundational metric in structural biology and computational chemistry, serving as a quantitative measure of the average distance between atoms of superimposed molecular structures. The RMSD provides a single numerical value that captures the structural similarity or dissimilarity between conformational states, making it indispensable for monitoring structural changes in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, evaluating protein structure predictions, and assessing the quality of molecular docking experiments [11] [12] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the mathematical formulation of RMSD is crucial for proper interpretation of results and avoidance of common pitfalls in structural analysis.

The significance of RMSD extends across numerous applications in molecular analysis. In drug discovery, RMSD calculations help validate docking poses by comparing predicted ligand conformations to experimentally determined structures [13]. In molecular dynamics simulations, RMSD tracks protein folding pathways, conformational changes, and system stability over time [8] [14]. The metric also plays a vital role in assessing structural ensembles from NMR spectroscopy, comparing crystal structures, and analyzing the effects of mutations on protein structure [12]. Despite its widespread use, the mathematical nuances of RMSD calculation and interpretation require careful consideration to ensure biologically relevant conclusions.

Mathematical Foundation of RMSD

Core RMSD Equation

The fundamental RMSD equation calculates the deviation between two sets of atomic coordinates after optimal superposition. For two structures with N equivalent atoms, the RMSD is defined as:

RMSD = √(1/N × ∑ᵢ₌₁ᴺ dᵢ²) [13]

where dᵢ represents the Euclidean distance between the coordinates of the i-th pair of corresponding atoms after optimal alignment. The calculation involves summing the squared distances between all corresponding atom pairs, dividing by the total number of atom pairs, and taking the square root of the result [11] [2]. This formulation provides a dimensioned measure (typically in Ångströms, Å) of the average structural displacement.

The mathematical derivation begins with the assumption of two coordinate sets: A = {a₁, a₂, ..., aₙ} and B = {b₁, b₂, ..., bₙ}, where each aᵢ and bᵢ represents the 3D coordinates of atoms in structures A and B, respectively. The RMSD is minimized when the structures are optimally aligned through rotation and translation, a process known as the Kabsch algorithm or Wahba's problem in more general terms [12]. The optimal alignment involves centering both structures at their centroid then finding the rotation that minimizes the sum of squared distances between corresponding points.

RMSD as an Estimator

In statistical terms, RMSD serves as an estimator for the difference between an estimated parameter and its true value. For an estimator θ̂ of parameter θ, the RMSD is defined as:

RMSD(θ̂) = √MSE(θ̂) = √E((θ̂ - θ)²) [11]

where MSE represents the Mean Square Error. For unbiased estimators, the RMSD equals the standard deviation, representing the root mean square of the differences between predicted values and observed values [11]. This statistical formulation highlights RMSD's role in quantifying predictive accuracy across various scientific domains.

Table 1: Key RMSD Equations and Their Applications

| Equation Type | Mathematical Formulation | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sample RMSD | RMSD = √[1/n × ∑ᵢ₌₁ⁿ(Xᵢ - x₀)²] | Comparing sample observations to true values [11] |

| Predictive RMSD | RMSD = √[∑ₜ₌₁ᵀ(yₜ - ŷₜ)²/T] | Evaluating model predictions against observed data [11] |

| Pairwise Structural RMSD | RMSD = √[∑ᵢ₌₁ᴺ ‖rᵢ - rᵢ'‖²/N] | Comparing two molecular structures after alignment [12] |

| Ensemble RMSD | <RMSD²>¹/² = √[1/Nₘ² × ∑ᵢⱼ ‖rᵢ - rⱼ‖²] | Analyzing structural diversity in molecular ensembles [12] |

Critical Considerations in RMSD Calculation

Molecular Symmetry and Atom Mapping

A significant challenge in RMSD calculation arises with symmetric molecules, where direct atomic correspondence may not reflect chemically equivalent structures. Naïve RMSD calculations that assume direct file order atomic correspondence can artificially inflate RMSD values for symmetric molecules like benzene or ibuprofen, where multiple valid atomic mappings exist [13]. For example, rotating a symmetric molecule along its axis of symmetry should yield an RMSD of zero, but incorrect atom mapping can produce erroneously high values.

Advanced approaches like the DockRMSD algorithm address this by formulating atomic correspondence as a graph isomorphism problem [13]. The algorithm:

- Represents molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges

- Identifies chemically equivalent atoms through neighborhood topology matching

- Performs an exhaustive search with dead-end elimination to find the minimal RMSD mapping

- Maintains bonding network consistency throughout the mapping process

This method ensures physically meaningful atomic correspondences that respect molecular symmetry, providing biologically relevant RMSD values rather than artificially inflated measurements [13].

Normalization and Scale Dependence

RMSD is inherently scale-dependent, making direct comparisons across different molecular systems problematic [11]. A 2Å RMSD for a small drug molecule represents substantial structural deviation, while the same value for an entire protein complex might indicate remarkable similarity. To address this limitation, normalized RMSD (NRMSD) approaches have been developed:

NRMSD = RMSD/(ymax - ymin) or NRMSD = RMSD/ȳ [11]

where ymax and ymin represent the range of observed values, and ȳ represents the mean value. Normalization enables more meaningful comparisons between datasets or models with different scales [11]. The Coefficient of Variation of RMSD (CV(RMSD)) provides another normalization approach by dividing RMSD by the mean of measured data, analogous to the coefficient of variation using standard deviation [11].

For distributions with outliers, dividing RMSD by the interquartile range (IQR) creates a normalized value less sensitive to extreme values:

RMSD_IQR = RMSD/IQR where IQR = Q₃ - Q₁ [11]

This approach improves robustness when comparing systems with different levels of structural heterogeneity or when outlier conformations disproportionately influence the standard RMSD value.

Experimental Protocols for RMSD Analysis

RMSD Calculation in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations generate structural trajectories that require RMSD analysis to assess conformational stability and changes. The following protocol outlines the standard workflow for RMSD analysis using VMD software:

Trajectory Loading: Load the MD trajectory file and corresponding protein structure into VMD using the "File" menu. Ensure all trajectory frames are properly read and coordinates are intact [15].

Region Selection: Access the RMSD Trajectory Tool through "Extensions" → "Analysis" → "RMSD Trajectory Tool." Select the region of interest by entering appropriate selection commands:

- Entire protein: "protein"

- Backbone only: Check "backbone" box

- Specific residues: "resid 1 to 100" [15]

Reference Frame Specification: Set the reference frame for alignment. By default, VMD uses the first frame (frame 0), but this can be modified to any frame in the trajectory based on analysis needs [15].

RMSD Calculation: Click the "RMSD" button to perform the calculation. The tool will superpose each frame onto the reference structure using the selected atoms and compute the RMSD values across the trajectory [15].

Result Visualization and Export: View results in the data table or plot RMSD versus time. Export data for further analysis by saving in the default .dat format or other compatible formats [15].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RMSD Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| VMD RMSD Trajectory Tool | Trajectory RMSD analysis | Built-in VMD module, backbone/specific region selection, graphical plotting [15] | MD simulation analysis, conformational stability assessment |

| DockRMSD | Symmetry-corrected RMSD | Graph isomorphism for atom mapping, MOL2 format support, open-source [13] | Docking pose comparison, symmetric molecule evaluation |

| PyMOL | Structural visualization & RMSD | Superposition algorithms, visualization of structural alignments [2] | General structural biology, publication-quality images |

| MDAnalysis | Programmatic trajectory analysis | Python library, batch processing, integration with data science workflows [2] | High-throughput analysis, custom analysis pipelines |

| GROMACS | MD simulation & analysis | Built-in RMSD modules, trajectory analysis, production-quality simulations [8] | Biomolecular simulation, force field applications |

Workflow for Docking Pose Validation

Validating docking predictions requires comparing computed ligand poses with experimental reference structures. The following protocol ensures proper RMSD calculation for docking validation:

Structure Preparation: Prepare the predicted and reference ligand structures in MOL2 format, ensuring identical atom types and bonding information. Remove water molecules and ions unless specifically relevant to the binding mode [2] [13].

Receptor Alignment: Superimpose the protein structures from the predicted and reference complexes using conserved binding site residues or the entire protein backbone. This ensures the ligand comparison occurs in the same reference frame [13].

Symmetry Assessment: Identify symmetric elements in the ligand structure, including rotatable symmetric groups, aromatic systems, and symmetric functional groups. Tools like DockRMSD automatically detect molecular symmetry through graph isomorphism searching [13].

Atom Mapping Optimization: For symmetric molecules, determine the optimal atomic correspondence that minimizes RMSD while maintaining chemical validity. DockRMSD employs an exhaustive search with dead-end elimination to identify the minimal RMSD mapping [13].

RMSD Calculation and Interpretation: Compute the symmetry-corrected RMSD and interpret results using established thresholds:

Advanced Applications and Interpretation

Relationship to Other Structural Metrics

RMSD maintains important mathematical relationships with other structural metrics. In X-ray crystallography, the ensemble-average pairwise RMSD relates to average B-factors through the equation:

<RMSD²>¹/² ∝ <B> [12]

where <B> represents the average B-factor (Debye-Waller factor). This relationship enables estimation of global structural diversity in protein ensembles directly from experimental B-factors [12]. The connection emerges from the mathematical analogy between RMSD and the radius of gyration (Rg), where pairwise RMSD distributions mirror the pairwise distance calculations used to determine Rg [12].

For RNA structural analysis, the Deformation Index (DI) incorporates RMSD but adds base interaction fidelity:

DI = RMSD/INF [16]

where INF represents the Interaction Network Fidelity calculated using the Matthews Correlation Coefficient between base-pairing and base-stacking interactions of compared structures [16]. This hybrid metric addresses RMSD's limitation in capturing the specific base interaction patterns crucial for RNA function.

Limitations and Complementary Approaches

While RMSD provides valuable global structural comparison, it has recognized limitations. RMSD spreads errors uniformly across the entire structure, making it difficult to localize structural discrepancies [16]. The metric is sensitive to outlier regions where large deviations can disproportionately influence the final value [11]. Additionally, RMSD values depend on the number of atoms included in the calculation, with all-atom RMSD typically yielding higher values than backbone-only calculations [2].

Complementary metrics address these limitations:

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Analyzes local flexibility by measuring atomic position variance around average positions [12]

- Interaction Network Fidelity (INF): Quantifies reproduction of specific base-pairing and base-stacking interactions [16]

- Deformation Profile (DP): Localizes structural differences at nucleotide resolution for RNA molecules [16]

These complementary approaches combined with RMSD provide a more comprehensive structural analysis framework, particularly for complex biomolecules with specific functional interactions.

Visualization of RMSD Analysis Workflows

RMSD Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for calculating RMSD between molecular structures, highlighting critical steps including symmetry assessment and atom mapping that ensure accurate results.

RMSD Research Applications: This diagram showcases the primary research applications of RMSD calculations in molecular analysis and the key insights derived from each application area.

Within the framework of molecular dynamics (MD) analysis, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) serves as a fundamental metric for quantifying conformational similarity and tracking the evolution of a molecular system over time [17]. The reliability of any RMSD-based analysis, however, is critically dependent on two foundational elements: the choice of the initial reference structure and the application of a proper structural alignment protocol [18]. A reference structure provides the baseline coordinate set against which all subsequent conformational changes are measured, while alignment corrects for overall rotational and translational motion that is irrelevant to internal conformational dynamics [19]. Neglecting these steps can lead to RMSD values that are dominated by whole-molecule rotation and translation rather than meaningful biological fluctuations, thereby obscuring true functional insights [17] [19]. This application note details the protocols and considerations essential for ensuring that RMSD analyses accurately reflect the internal dynamics of biological macromolecules, with a specific focus on proteins and RNA nanostructures in drug development research.

Theoretical Foundation

The RMSD Metric and its Interpretation

The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a standard measure of the average distance between atoms in two superimposed molecular structures [1]. For two sets of coordinates, v and w, each containing n equivalent atoms, the RMSD is mathematically defined as:

[RMSD(\mathbf{v}, \mathbf{w}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} \|\mathbf{v}i - \mathbf{w}_i\|^2}]

In the context of MD simulations, one set of coordinates typically comes from a reference structure (e.g., the starting frame), and the other from a simulated snapshot [19]. The summation occurs over all selected atom pairs after an optimal rigid-body rotation and translation have been applied to minimize this value [1] [19]. The result is expressed in units of length (Ångströms, Å), with a value of 0 indicating perfect atomic overlap between the two structures [11] [1].

The biological interpretation of RMSD is nuanced. While a lower RMSD generally suggests greater structural similarity to the reference, and a stable RMSD over time can indicate conformational convergence, the metric suffers from degeneracy [19]. Many different conformational states can share the same RMSD value relative to a single reference. Furthermore, the global RMSD can be dominated by the displacement of a few, potentially flexible regions (like long loops or termini), masking the stability of the structural core [18]. Consequently, a careful selection of which atoms to include in the RMSD calculation is paramount for drawing biologically relevant conclusions.

The Necessity of Alignment

MD simulations allow molecules to freely rotate and translate in space. The RMSD calculated from these raw, unaligned coordinates would be artificially inflated by this global motion, providing little information about internal conformational changes, such as hinge movements in enzymes or loop rearrangements in binding pockets [17] [19].

To isolate internal dynamics, an alignment step is performed prior to RMSD calculation. This involves superposing the structure of interest onto a reference structure by finding the optimal rotation matrix and translation vector that minimize the RMSD for a selected subset of atoms, typically the stable structural core [19]. After this superposition, the RMSD is recalculated, now reflecting only the internal conformational differences. As illustrated in the protocol below, this step is crucial for obtaining a meaningful analysis of flexibility and stability [17].

Protocols for Reference Structure Selection and Alignment

Criteria for Selecting an Optimal Reference Structure

The choice of reference structure sets the baseline for all subsequent RMSD analyses. An inappropriate reference can systematically skew results and lead to incorrect interpretations.

Table 1: Criteria for Selecting a Reference Structure

| Criterion | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Source | Prefer high-resolution structures from X-ray crystallography (<2.0 Å) or NMR ensembles [20] [18]. | Ensures atomic-level accuracy and reliability of the initial coordinates. |

| Biological Relevance | The structure should represent a functionally relevant state (e.g., active vs. inactive conformation) [18]. | Ensures dynamics are interpreted in the correct functional context. |

| Structural Completeness | The structure should have minimal missing residues, particularly in the regions of interest (e.g., active site) [20]. | Prevents artificial fluctuations due to undefined atomic positions. |

| Computational Models | For designed molecules (e.g., RNA nanostructures), use a model that has undergone energy minimization to fix steric clashes [20]. | Provides a physically realistic and stable starting point for simulation. |

A Standard Protocol for Structural Alignment and RMSD Calculation

The following protocol, adaptable for tools like MDAnalysis [17] [19] and Amber [20], outlines the key steps for proper alignment and RMSD analysis.

Step 1: Prepare the Topology and Trajectory

- Load the initial reference structure (e.g., a PDB file) and the MD trajectory file (e.g., DCD, XTC) into your analysis universe [19].

Step 2: Select Atoms for Alignment

- Choose a stable set of atoms to define the superposition. For proteins, the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C) or just the Cα atoms are commonly used, as they filter out noise from flexible side-chain motions [19]. For RNA, the phosphate backbone atoms often serve a similar purpose [20].

- Example selection in MDAnalysis:

select='backbone'orselect='name CA'[19].

Step 3: Perform Trajectory Alignment

- Iterate through each frame of the trajectory. For each frame, calculate the optimal rotation and translation that minimizes the RMSD of the selected alignment atoms to their positions in the reference frame.

- Apply this same transformation to all atoms in the system. This ensures the entire molecule (including ligands, solvent, etc.) is correctly positioned for analysis [17].

- In MDAnalysis, this is efficiently done using the

AlignTrajfunction [17].

Step 4: Calculate RMSD for Regions of Interest

- After alignment, calculate the RMSD time series. You can calculate a global RMSD using the same selection as for alignment, or, more informatively, calculate RMSD for specific domains or residues using

groupselections[19]. - Example: For adenylate kinase, one can calculate separate RMSDs for the CORE, LID, and NMP domains to quantify hinge motion independently of the stable core [19].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of RMSD Metrics

Presenting RMSD data effectively requires clarity about which atoms were used for both alignment and calculation. The table below demonstrates how different selections reveal distinct aspects of molecular dynamics.

Table 2: RMSD Analysis of Adenylate Kinase (AdK) Domain Motions

| Frame | Time (ns) | Global Backbone (Å) | CORE Domain (Å) | LID Domain (Å) | NMP Domain (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 50 | 50.00 | 3.50 | 1.20 | 8.10 | 7.20 |

| 100 | 100.00 | 6.82 | 3.51 | 11.39 | 10.37 |

Note: Data is illustrative, based on analysis concepts from [19]. The table reveals that while the CORE domain remains relatively stable, the LID and NMP domains undergo large conformational changes, which is the functional motion of AdK. A global RMSD alone would mask this detail.

Advanced and Alternative Measures

While standard RMSD is powerful, researchers should be aware of its limitations and the availability of advanced measures.

- Weighted RMSD (wRMSD): This method uses a Gaussian weighting function during superposition, giving higher weight to atoms that move less between two conformations. This automatically focuses the alignment on the most stable structural core, providing a clearer picture of flexibility, especially for proteins with large hinged domains [21].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Unlike RMSD, which measures deviation from a reference over time, RMSF calculates the fluctuation of each atom around its average position. It is excellent for identifying flexible and rigid regions within a structure, often visualized as a plot per residue [17].

- Contact-Based Measures: These superimposition-independent methods quantify similarity based on conserved atomic or residue contacts. They are more robust than RMSD when comparing structures with significant conformational differences or domain rearrangements [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

A successful MD analysis project relies on a suite of specialized software and resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Amber | A comprehensive MD software package with specialized force fields for proteins and nucleic acids [20]. | Widely used for simulating and analyzing biomolecules; includes tools for energy minimization and MD setup [20]. |

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD simulation package, free and open-source [22]. | Known for its speed and efficiency; commonly used for large systems and long timescales [22]. |

| MDAnalysis | A Python library for analyzing MD trajectories [17] [19]. | Provides a flexible environment for scripting custom analyses, including RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen bonding [19]. |

| VMD | A molecular visualization program with built-in analysis tools [20]. | Used for visualizing trajectories, creating publication-quality images, and initial system setup [20]. |

| Experimental Structure Database (PDB) | The primary repository for experimentally-determined macromolecular structures [18]. | The primary source for high-quality reference structures for simulations and analysis [18]. |

| Force Field (e.g., ff14SB, ff19SB) | A parameter set defining the potential energy function for atoms in a simulation [20] [23]. | The choice of force field is critical for simulation accuracy; modern force fields have significantly improved the realism of MD [20] [23]. |

The rigorous application of protocols for reference structure selection and structural alignment is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational component of meaningful MD analysis. By carefully choosing a biologically relevant, high-resolution reference and employing a proper alignment strategy focused on stable structural elements, researchers can ensure that the resulting RMSD values accurately reflect internal conformational dynamics. This, in turn, enables reliable insights into mechanisms of drug binding, allostery, and protein flexibility. As MD simulations continue to grow in importance for drug discovery, adhering to these disciplined practices will be crucial for generating robust, interpretable, and actionable data.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a fundamental statistical measure used to quantify the average magnitude of difference between two sets of atomic coordinates. In structural biology and computational chemistry, RMSD provides a standardized approach for assessing conformational changes, evaluating model accuracy, and measuring structural convergence in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [11] [1]. The RMSD value represents the square root of the average of squared distances between corresponding atoms in superimposed molecular structures, typically measured in Ångströms (Å), where 1 Å equals 10⁻¹⁰ meters [1].

The mathematical formulation for calculating RMSD between two sets of atomic coordinates v and w is expressed as:

RMSD(v,w) = √[1/n × Σ‖vᵢ - wᵢ‖²] [1]

Where:

- n = number of equivalent atoms being compared

- vᵢ and wᵢ = coordinates of the i-th atom in the two structures

- ‖vᵢ - wᵢ‖ = Euclidean distance between corresponding atoms

In molecular dynamics simulations, RMSD serves as a crucial reaction coordinate for tracking structural evolution over time, providing insights into protein folding pathways, conformational stability, and the effects of ligand binding on macromolecular structure [1]. For drug discovery professionals, understanding RMSD interpretation is essential for validating docking poses, assessing predicted model quality, and making informed decisions about compound prioritization based on structural data.

Quantitative Interpretation of RMSD Values

General Guidelines for RMSD Assessment

The interpretation of RMSD values depends on contextual factors including the molecular system, comparison methodology, and research objectives. The following table provides general guidelines for interpreting global backbone RMSD values in protein structural analysis:

Table 1: General Interpretation Guidelines for Global Protein Backbone RMSD

| RMSD Range | Structural Interpretation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 - 1.5 Å | Very high similarity; often within experimental error or thermal fluctuation range [18] | Comparing multiple determinations of the same structure; assessing simulation convergence |

| 1.0 - 2.0 Å | High similarity; essentially identical structures [24] | Validating high-accuracy homology models; comparing closely related homologs |

| 2.0 - 3.0 Å | Moderate similarity; structurally related with some local variations [24] | Assessing acceptable homology models; comparing structures with conservative substitutions |

| 3.0 - 4.0 Å | Low similarity; notable structural differences, but potentially shared fold [24] | Detecting distant evolutionary relationships; evaluating low-accuracy models |

| > 4.0 Å | Very low similarity; substantially different structures [24] | Identifying different protein folds; rejecting poor-quality models |

Context-Dependent RMSD Evaluation

The general guidelines in Table 1 require careful consideration of specific research contexts:

Molecular size considerations: RMSD values tend to increase with protein size due to the cumulative effect of small deviations across more atoms. A 2.0 Å RMSD might indicate excellent agreement for a large multi-domain protein (e.g., >500 residues) but only moderate agreement for a small protein domain (e.g., <100 residues) [18].

Comparison scope: Global RMSD (calculated over entire structures) provides an overall similarity measure but can be dominated by flexible regions. Local RMSD (calculated over specific regions like binding sites) often provides more functionally relevant information for drug discovery applications [18] [24].

Structural flexibility: Regions with inherent flexibility (loops, termini) often exhibit higher RMSD values than structured elements (α-helices, β-sheets). Analysis should differentiate between rigid-body movements, flexible region variations, and overall structural deviations [18].

Reference structure quality: When comparing against experimental structures, consider the resolution and quality of the reference data. RMSD values near or below the experimental resolution may not be statistically significant [18].

Experimental Protocols for RMSD Analysis

Standard Workflow for RMSD Calculation in Molecular Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the standard protocol for RMSD calculation and interpretation in MD simulations:

Protocol Details

Step 1: Structure Preparation

- Input Structures: Obtain reference and target structures in PDB format. Reference structures are typically experimental coordinates or a stable simulation frame [1].

- System Uniformity: Ensure identical atom naming, residue numbering, and chain identifiers between compared structures. Remove non-standard residues or crystallographic additives that might interfere with alignment [25].

- Protonation States: Assign appropriate protonation states for histidine residues and other titratable groups based on physiological pH (7.4) [25].

Step 2: Structural Superposition

- Alignment Algorithm: Implement the Kabsch algorithm or quaternion-based rotation for optimal rigid-body superposition, minimizing the RMSD between equivalent atoms [1].

- Reference Frame: Align all structures to a common reference frame, typically the initial simulation structure or experimental coordinates.

- Iterative Refinement: For structures with significant local variations, consider iterative superposition methods that down-weight outliers to identify the maximal common substructure [18].

Step 3: Atom Selection

- Backbone Atoms (N, Cα, C, O): Most common selection for protein structural comparisons, providing a balance between sensitivity and robustness to side-chain conformational changes [1].

- Cα Atoms Only: Simplified representation useful for large-scale comparisons and fold recognition, particularly effective for identifying global structural similarity [24].

- Binding Site Atoms: Specific selection of residues forming active sites or ligand-binding pockets, crucial for functional analysis in drug discovery [25].

- Heavy Atoms: Comprehensive comparison including all non-hydrogen atoms, most sensitive to conformational differences but susceptible to noise from side-chain rotations.

Step 4: RMSD Calculation

- Mathematical Implementation: Apply the RMSD formula after optimal superposition. Most molecular visualization and analysis packages (VMD, PyMOL, GROMACS) include built-in RMSD calculation functions [1].

- Time Series Analysis: For MD trajectories, calculate RMSD as a function of simulation time to monitor structural stability and convergence.

- Ensemble Comparisons: When comparing structural ensembles, calculate pairwise RMSD matrices to assess overall conformational diversity.

Step 5: Interpretation and Validation

- Contextual Analysis: Interpret RMSD values relative to system-specific benchmarks (see Table 1) and research objectives.

- Complementary Metrics: Validate findings using additional structural similarity measures (TM-score, GDT, RMSF) to ensure robust conclusions [18] [24].

- Statistical Significance: Assess whether observed RMSD differences are statistically significant through replicate simulations or ensemble comparisons.

Protocol for Docking Pose Validation Using RMSD

The application of RMSD in validating molecular docking predictions requires specific methodological considerations:

Experimental Workflow

Table 2: RMSD Protocol for Docking Validation

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Prepare protein and ligand structures using molecular visualization software (AutoDockTools, OpenBabel) [25]. | Gasteiger charges, protonation states at pH 7.4, removal of crystallographic water molecules [25]. |

| Reference Setup | Obtain experimental ligand-protein complex structure as reference. | High-resolution crystal structure (<2.5 Å) with minimal missing residues in binding site. |

| Docking Execution | Perform molecular docking using preferred software (AutoDock Vina, QuickVina-w) [25]. | Appropriate search space dimensions; for blind docking, box size slightly larger than protein dimensions [25]. |

| Pose Extraction | Extract top-ranked docking poses based on scoring function. | Multiple poses (typically 5-20) should be considered to account for scoring function limitations. |

| RMSD Calculation | Superimpose protein structures, then calculate ligand heavy atom RMSD between docked and crystallographic poses. | Optimal rigid-body superposition of protein binding site residues prior to ligand comparison. |

| Validation | Compare calculated RMSD against acceptance thresholds. | Poses with RMSD < 2.0 Å generally considered successful predictions [25]. |

Performance Expectations

- Site-Specific Docking: When the binding site is known and appropriately defined, success rates (RMSD < 2.0 Å) typically approach 90% for standard docking benchmarks like CASF-2016 [25].

- Blind Docking: When searching the entire protein surface, success rates decrease substantially to approximately 34-47% (RMSD < 2.0 Å) due to increased search space and false minima [25].

- Exhaustiveness Settings: Higher exhaustiveness parameters in docking software can improve accuracy but increase computational cost 8-fold or more [25].

Complementary Metrics for Structural Comparison

Limitations of RMSD and Alternative Approaches

While RMSD remains widely used, several limitations necessitate complementary assessment metrics:

- Sensitivity to Outliers: RMSD is dominated by the largest deviations in a structure, meaning that a small region with large structural differences can disproportionately influence the global RMSD value [11] [18].

- Size Dependency: Global RMSD values tend to increase with protein size, making comparisons between different-sized proteins problematic [18].

- Alignment Dependence: RMSD calculation requires prior structural alignment, and different alignment methods can produce substantially different RMSD values [18].

- Limited Functional Relevance: Global RMSD may not correlate with functional properties, as key functional regions might be conserved while other regions diverge [18].

Integrated Assessment Framework

The following diagram illustrates how multiple metrics provide complementary structural information:

Table 3: Complementary Structural Comparison Metrics

| Metric | Type | Interpretation | Advantages Over RMSD |

|---|---|---|---|

| TM-score | Global | Normalized score (0,1]; >0.5 indicates same fold; <0.17 random similarity [24] | Size-independent; better fold-level discrimination; more intuitive interpretation [24] |

| GDT (Global Distance Test) | Global | Percentage of residues under specific distance cutoffs (e.g., 1Å, 2Å, 4Å) [24] | Less sensitive to outliers; emphasizes conserved regions; standard in CASP assessments [24] |

| LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test) | Local | Score (0-100) assessing local distance differences; >80 high quality [24] | Superposition-independent; evaluates local environment preservation; used in AlphaFold2 [24] |

| RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) | Local | Measures deviation from average position over time [1] | Quantifies flexibility; identifies rigid vs. flexible regions in dynamics simulations [1] |

Application in Drug Discovery: Case Studies and Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions for RMSD Analysis

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for RMSD Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Application in RMSD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS [8], AMBER, NAMD | Perform MD simulations and calculate RMSD time series with built-in functions |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis, MDTraj, CPPTRAJ | Process simulation trajectories; compute RMSD and related properties |

| Molecular Visualization | PyMOL, VMD, ChimeraX | Structural superposition; visual validation of RMSD calculations |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina [25], QuickVina-w [25] | Generate ligand poses for binding mode validation via RMSD |

| Structural Alignment | Kabsch algorithm [1], Quaternions [1] | Optimal rigid-body superposition for RMSD minimization |

| Specialized Assessment | LGA [18], TM-score [24] | Implement alternative metrics to complement RMSD analysis |

Case Study: RMSD in Binding Pose Validation

A comprehensive assessment of blind docking methods on the CASF-2016 benchmark (285 protein-ligand complexes) revealed critical insights about RMSD interpretation in drug discovery contexts [25]:

- Success Rate Analysis: Only 34-47% of blind docking predictions achieved RMSD values < 2.0 Å relative to crystallographic reference structures, compared to 90.2% success for site-specific docking [25].

- Absolute RMSD Values: The median RMSD values for blind docking predictions ranged from 2.207-3.370 Å depending on software and exhaustiveness settings [25].

- Correlation with Experimental Data: Binding affinities calculated from blind docking showed very low correlation with experimental values (R² ≈ 0.15), indicating that RMSD alone does not guarantee predictive binding energy calculations [25].

Case Study: RMSD in Molecular Dynamics for Solubility Prediction

Recent research integrating MD simulations with machine learning identified RMSD as one of seven key MD-derived properties for predicting drug solubility [8]:

- Feature Importance: In a study of 211 drugs, RMSD (along with logP, SASA, Coulombic interactions, Lennard-Jones potentials, solvation free energies, and solvation shell properties) contributed significantly to accurate solubility prediction [8].

- Predictive Performance: Gradient Boosting algorithms utilizing these MD-derived properties achieved R² = 0.87 and RMSE = 0.537 for solubility prediction, demonstrating the value of RMSD in quantitative structure-property relationship models [8].

- Protocol Implementation: MD simulations were conducted in GROMACS 5.1.1 using the GROMOS 54a7 force field, with RMSD calculated for solute conformations throughout production trajectories [8].

The interpretation of RMSD values requires careful consideration of research context, system characteristics, and methodological parameters. While general guidelines suggest RMSD values below 2.0 Å indicate high structural similarity and values above 3.0-4.0 Å reflect significant differences, these thresholds must be adapted to specific applications in molecular dynamics and drug discovery. The integration of RMSD with complementary metrics like TM-score, GDT, and LDDT provides a more robust framework for structural assessment, overcoming individual limitations of each measure. For drug development professionals, RMSD remains an essential tool for validating docking poses, assessing conformational stability in MD simulations, and building predictive models of molecular properties, though its limitations necessitate careful implementation within a comprehensive structural analysis workflow.

In the post-AlphaFold era, where the prediction of static protein structures has been revolutionized by deep learning, the focus of structural biology is increasingly shifting toward understanding protein dynamics [26]. Proteins are not static entities; they function as conformational ensembles, and their biological activity is fundamentally governed by dynamic transitions between these states [26]. Within this paradigm, Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analyzed as a function of simulation time serves as a crucial metric for quantifying conformational stability and tracking structural evolution in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

RMSD measures the average distance between the atoms of a simulated structure and a reference structure after optimal alignment [27]. When plotted over time, it provides a trajectory of structural change, revealing stability, unfolding events, and transitions between conformational states. This application note details the protocols for calculating and interpreting time-dependent RMSD, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to integrate dynamic structural analysis into their work.

Essential Concepts and Quantitative Foundations

The RMSD Metric: A Mathematical Definition

The RMSD quantifies the deviation between two molecular structures. For a simulation trajectory, it is typically calculated for each frame ( t ) relative to a reference frame (often the initial structure at ( t=0 )) [28] [27]. The fundamental formula is:

[ RMSD(t) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N wi \lVert \mathbf{x}i(t) - \mathbf{x}i^{\text{ref}} \rVert^2} ]

where:

- ( N ) is the number of atoms used in the calculation.

- ( \mathbf{x}_i(t) ) is the position of atom ( i ) at time ( t ).

- ( \mathbf{x}_i^{\text{ref}} ) is the position of atom ( i ) in the reference structure.

- ( w_i ) is the weight assigned to atom ( i ), often its mass or simply ( 1/N ) for an unweighted average [28].

A critical step before RMSD calculation is the superposition (or fitting) of the simulated structure onto the reference structure to remove global translation and rotation, ensuring the metric reflects internal conformational changes only [28] [27]. This is often done using a subset of atoms, such as the protein backbone.

Interpreting the RMSD vs. Time Plot

The trajectory of RMSD over time provides direct insight into system behavior:

- Rapid Convergence and Stable Plateau: A system that quickly reaches a stable, low RMSD value (e.g., below 1-2 Å for a protein backbone) suggests the simulation has equilibrated and the structure is stable, closely resembling the reference [29].

- Progressive Drift: A steady, continuous increase in RMSD can indicate that the structure is undergoing a significant conformational change or drifting away from the reference state, possibly due to an inadequate force field or the lack of a necessary stabilizing factor [10].

- Sharp Jumps or Transitions: Sudden increases in RMSD often mark discrete conformational transitions, such as domain movements or partial unfolding events [30].

- High Initial Fluctuations: Large, unstable oscillations at the beginning of a simulation can suggest the initial structure is in a high-energy state and is relaxing, or that the system has not yet equilibrated.

Table 1: Key Interpreations of RMSD vs. Time Trajectories

| RMSD Profile | Structural Implication | Common Cause / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Stable, Low Plateau | Conformational stability | Native state is stable under simulation conditions. |

| Progressive Drift | Conformational shift or force field inaccuracy | Ligand dissociation, domain movement, or insufficient sampling. |

| Sharp Jumps | Discrete conformational transition | Ligand binding/unbinding, allosteric change, or partial unfolding. |

| High Initial Fluctuations | System equilibration or unstable starting structure | Relaxation from a non-equilibrium starting conformation. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Standard Protocol for RMSD Analysis in GROMACS

This protocol outlines the steps for performing a basic RMSD analysis on a protein backbone using the GROMACS MD package [31] [27].

1. Simulation Preparation:

- Obtain an initial structure (e.g., from PDB, AlphaFold prediction [31]).

- Solvate the protein in a suitable water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Minimize the energy of the system to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibrate the system, first under an NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and then under an NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature).

2. Production MD Simulation:

- Run a production simulation, typically for tens to hundreds of nanoseconds, saving trajectory frames at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 ps).

3. Trajectory Preprocessing (Post-Simulation):

- Make the molecule whole: If periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are used, ensure molecules are not split across the box.

- Center the system: Place the protein at the center of the box.

- Remove system jumps and rotations: Fit the trajectory to a reference structure (e.g., the initial protein backbone) to remove global motion.

4. RMSD Calculation:

- Calculate the RMSD of the protein backbone (or other atom selection) over time relative to the reference structure. When prompted, select "Backbone" for both the fitting and the RMSD calculation groups.

The resulting .xvg file can be plotted to visualize RMSD as a function of simulation time.

Advanced Protocol: Multi-Domain RMSD Analysis

For proteins with multiple domains, analyzing RMSD for the entire protein can mask distinct behaviors of individual domains. This protocol, implementable in MDAnalysis [28] or GROMACS, allows for simultaneous tracking of global and local dynamics.

1. Define Atom Groups:

- Identify the atoms for the global fit (e.g., entire protein backbone).

- Define selections for specific domains or regions of interest (e.g., CORE, LID, and NMP domains as in the adenylate kinase example [28]).

2. Execute Analysis with Group Selections:

- Using MDAnalysis, the

RMSDclass can compute the RMSD for the global fit and for multiple group selections simultaneously.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common RMSD Analysis Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| RMSD never stabilizes | System is not equilibrated; protein is unfolding or undergoing large conformational change. | Check simulation parameters (temperature, pressure). Extend equilibration. Verify starting structure quality. |

| Unphysical RMSD jumps | Periodic boundary condition (PBC) artifacts; molecule is "jumping" across the box. | Use gmx trjconv -pbc whole (or equivalent) to make molecules whole before fitting and analysis [27]. |

| High RMSD from the start | Poor reference structure (e.g., low-quality model or incorrect state). | Use a high-resolution experimental structure or a high-confidence AlphaFold model (with high pLDDT) as reference [31]. |

| Noisy RMSD signal | Trajectory is not properly fitted to remove global rotation/translation. | Ensure the fitting step (-fit rot+trans in GROMACS, superposition=True in MDAnalysis) is correctly applied [28] [27]. |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biotherapeutics

Time-dependent RMSD analysis is a cornerstone in computational drug discovery, providing critical insights into ligand binding, stability, and mechanism of action.

Evaluating Ligand-Protein Complex Stability

In virtual screening campaigns, RMSD is used to filter and prioritize hit compounds. After docking potential inhibitors into a target's binding site, MD simulations are run on the top complexes. A stable, low RMSD for both the ligand and the binding site residues indicates a stable binding pose and a promising hit [29]. For example, a study on mTOR inhibitors used RMSD to identify compounds that remained stably bound in the active site, forming key interactions with residues like VAL-2240 and TRP-2239 [29]. In contrast, a climbing RMSD for the ligand often signifies pose inversion or dissociation.

Assessing the Impact of Mutations and Environmental Changes

RMSD analysis can reveal the structural consequences of mutations or changes in environmental conditions (e.g., pH, temperature). The iGEM team at UBC Vancouver, for instance, used MD simulations at different pH levels (4, 6, 7, 9) to analyze the stability of fusion proteins for biocement applications. They monitored both RMSD and the Radius of Gyration (Rg) to understand how pH affected structural compactness and divergence from the starting conformation [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for RMSD Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in RMSD Analysis | Reference / Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software Package | High-performance MD engine; includes gmx rms for RMSD calculation. |

https://www.gromacs.org [27] [8] |

| AMBER | Software Package | MD suite with cpptraj for trajectory analysis, including RMSD. |

https://ambermd.org [10] |

| MDAnalysis | Python Library | Tool for analyzing MD trajectories; flexible RMSD analysis API. | https://www.mdanalysis.org [28] |

| AlphaFold | Web Server / Software | Generates high-accuracy predicted structures for use as reference models. | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk [26] [31] |

| PyMOL | Molecular Viewer | Visualizes structures and trajectories; used for structural alignment and validation. | https://pymol.org [31] |

| ATLAS Database | MD Database | Repository of pre-computed MD trajectories for reference and validation. | https://www.dsimb.inserm.fr/ATLAS [26] |

Limitations and Complementary Techniques

While RMSD is indispensable, it has limitations. As a global average, it can conceal localized fluctuations and is sensitive to the choice of reference structure and fitting procedure [30]. To build a comprehensive dynamic picture, RMSD should be used in conjunction with other metrics:

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Measures per-residue fluctuation around the average position, identifying flexible and rigid regions [30] [29].

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Quantifies the overall compactness of a structure, useful for detecting unfolding or compaction events [31].

- Trajectory Maps: A novel visualization method that plots residue backbone movements as a heatmap, revealing the location, time, and magnitude of conformational changes that may be averaged out in RMSD [30].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies the large-scale, collective motions that account for the most variance in the trajectory, moving beyond single-atom deviations [32].

The analysis of RMSD as a function of simulation time provides a foundational, powerful lens through which to view protein dynamics. It is a critical tool for validating simulation stability, quantifying conformational changes, and assessing ligand interactions in drug discovery. While its simplicity and interpretability make it a first step in nearly all MD analyses, its true power is unlocked when used as part of a broader, multi-faceted approach that includes residue-level fluctuations, collective motion analysis, and innovative visualization. As the field moves beyond single static structures, mastering these dynamic analysis techniques, with time-dependent RMSD at their core, is essential for unraveling the mechanistic basis of protein function and regulation.

How to Calculate and Apply RMSD: Practical Protocols in Biomolecular Simulation

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) is a cornerstone analysis metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, providing a quantitative measure of conformational change by calculating the average distance between atoms of a macromolecule, most commonly a protein, and a reference structure over time [33]. Within the broader context of molecular dynamics analysis, RMSD serves as a fundamental tool for assessing structural stability, identifying conformational changes, and determining the convergence of a simulation towards an equilibrium state [33]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a flat or stable RMSD profile often indicates that the protein has reached a stable conformation, whereas significant jumps or sustained shifts can signal major structural rearrangements or potential simulation artefacts [33] [34]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for performing robust RMSD analysis on protein trajectories using GROMACS, from initial trajectory preparation to advanced analysis and troubleshooting.

Theoretical Foundation of RMSD

The RMSD calculation quantifies the deviation between two molecular structures. For a structure with N atoms, the RMSD between a given conformation (r) and a reference structure (r^ref^) is calculated using the following equation, which involves a least-squares fitting procedure before the deviation is computed [35] [33]:

$$RMSD(t) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\displaystyle\sum{i=1}^N \deltai (ri(t) - ri^{ref})^2}$$

Here, r~i~^ref^ represents the coordinates of the i-th atom in the reference structure, while r~i~(t) are the coordinates of the same atom at time t in the trajectory [33]. The variable δ~i~ is a weighting factor, which is often the mass of the atom (m~i~) for mass-weighted RMSD calculations, or simply 1 for non-mass-weighted calculations [35] [36]. GROMACS can compute RMSD using different fitting strategies (e.g., rot+trans, translation, or none) and allows the user to specify different groups of atoms for the fitting and the RMSD calculation itself, providing significant flexibility in the analysis [35] [36].

An alternative, fit-free method involves calculating the RMSD based on internal distances, which is implemented in the gmx rmsdist tool [35]:

$$RMSD(t) ~=~ \left[\frac{1}{N^2}\sum{i=1}^N \sum{j=1}^N \|{\bf r}{ij}(t)-{\bf r}{ij}(0)\|^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}$$

This approach compares the distance r~ij~ between all pairs of atoms i and j at time t with their distances in the reference structure, eliminating the need for prior rotational and translational fitting [35].

Computational Methodology

Essential Software and Tools

A specific set of software tools is required to perform MD simulations and analyze trajectories effectively. The table below lists the key research reagent solutions and their functions in RMSD analysis.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for RMSD Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in RMSD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [33] [36] | MD Simulation Suite | Provides the gmx rms and gmx confrms utilities for calculating RMSD from trajectories. |

| VMD [37] [15] | Molecular Visualization | Enables visual inspection of trajectories and offers an integrated RMSD calculation tool. |

| PyMOL [37] | Molecular Visualization | Useful for high-quality rendering of protein structures before or after simulation. |

| Grace/Matplotlib [33] [37] | Data Plotting | Software libraries for graphing the resulting RMSD data from .xvg files. |

gmx trjconv [38] [37] |

Trajectory Processing Tool | Critical for correcting periodic boundary conditions and preparing trajectories for analysis. |

Pre-analysis: Trajectory Preparation

A crucial first step before any analysis is to process the raw trajectory to account for periodic boundary conditions (PBC), which can cause molecules to appear "broken" as they diffuse across the unit cell [38]. This is done using the gmx trjconv utility:

When prompted, select "Protein" as the group to center and "System" for output [38]. This command ensures that the protein remains whole and centered in the box throughout the trajectory, creating a corrected trajectory file (md_0_10_noPBC.xtc) that should be used for all subsequent RMSD analysis to avoid artefacts [38] [39].

Core Protocol: RMSD Calculation Usinggmx rms

The primary method for RMSD calculation in GROMACS is the gmx rms command. The following workflow outlines the complete procedure.

Figure 1: A workflow diagram for calculating RMSD using the GROMACS gmx rms module.

Step 1: Basic Command Execution

The fundamental command for RMSD calculation is:

-s: Specifies the reference structure file (typically a.tpror.grofile) [33] [38].-f: Provides the corrected trajectory file (.xtc) for analysis [33].-o: Defines the output file where RMSD time series data will be stored [33].-tu ns: An optional flag to set the time unit in the output file to nanoseconds for easier interpretation [33] [38].

Step 2: Atom Selection Strategy

Upon execution, the command will prompt you to select two atom groups interactively [33]:

- Group for least-squares fit: The set of atoms used to superimpose each frame of the trajectory onto the reference structure through rotational and translational fitting. This step minimizes the RMSD due to global motion [35].

- Group for RMSD calculation: The set of atoms for which the RMSD is actually computed after the fitting is complete.

It is a standard practice for protein simulations to use the "Backbone" atoms (group 4) for both fitting and RMSD calculation, as the backbone is a good indicator of the overall protein conformational change [33] [38]. This "backbone-to-backbone" RMSD provides a core measure of structural stability. The fitting and calculation groups do not need to be identical; for example, a protein can be fitted on the backbone atoms, but the RMSD can be computed for all protein atoms [35].

To automate the selection and avoid the interactive prompts, you can pipe the selections to the command:

Advanced Applications and Variations

Using a Different Reference Structure

While the default is to use the initial frame (t=0) as a reference, you can compute the RMSD relative to any structure, such as an experimental crystal structure (e.g., from a PDB file). This is useful for assessing deviation from a native state rather than the starting structure of the simulation [38].

Here, em.tpr is assumed to contain the coordinates from the original PDB file [38].

Analyzing Specific Subsets

To calculate the RMSD for a specific protein domain, a subset of residues, or a custom group of atoms, you must first create a custom index file using gmx make_ndx [33]. You then reference this file during the RMSD calculation:

This is particularly valuable for multi-domain proteins, where analyzing individual domains can isolate local flexibility from the overall motion of the protein [39].

RMSD Matrix Analysis

A powerful analysis involves calculating the pairwise RMSD between every frame in the trajectory, generating an RMSD matrix. This can reveal transitions between distinct conformational states, which appear as blocks along the matrix diagonal [35] [36].

The -m flag directs the output to an .xpm file, which can be visualized with gmx xpm2ps or other supporting viewers [36].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Quantitative Interpretation Guidelines

After generating an RMSD plot, correct interpretation is crucial. The following table provides general guidelines for understanding RMSD values in the context of protein stability.

Table 2: Interpretation of RMSD Values for Protein Structures

| RMSD Value (nm) | RMSD Value (Å) | Typical Interpretation | Structural Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.05 - 0.15 nm | 0.5 - 1.5 Å | Very Low | Excellent structural stability; minimal deviation from reference. |

| 0.15 - 0.25 nm | 1.5 - 2.5 Å | Low | Good stability; typical for a well-equilibrated, folded protein. |

| 0.25 - 0.35 nm | 2.5 - 3.5 Å | Moderate | Significant flexibility, possibly from loops, tails, or domain movements. |

| > 0.35 - 0.40 nm | > 3.5 - 4.0 Å | High | Large conformational changes; may indicate domain rearrangements or partial unfolding. |

It is critical to note that these values are general guidelines. Larger proteins and those with inherent flexibility, such as multi-domain proteins connected by flexible linkers, will naturally exhibit higher RMSD values (e.g., 1.5-2.5 nm) even in the absence of unfolding, due to the accumulation of small deviations across many atoms and the relative motion of domains [39]. A deviation of 2 Å (0.2 nm) is often considered a benchmark for good structural stability [34].

Visualization and Plotting

GROMACS outputs RMSD data in .xvg format, which can be plotted using various tools. The following Python code using Matplotlib provides a customizable way to visualize your results:

This script produces a clear line plot of RMSD versus time, allowing for direct observation of equilibration, stability, and any major conformational transitions [33].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with a correct workflow, several common issues can affect RMSD analysis.

High RMSD Values: If your RMSD is unusually high (e.g., > 2-3 nm), first visually inspect the trajectory in a program like VMD to check for unfolding or major artefacts [39]. For multi-domain proteins, calculate the RMSD for individual domains; if domain-specific RMSDs are low (e.g., 0.2-0.5 nm) while the global RMSD is high, the large value likely arises from the relative motion of rigid domains rather than unfolding [39]. You can also try excluding highly flexible terminal residues from the RMSD calculation, as their unfolding can disproportionately influence the result [39].

Sudden Jumps in RMSD: Discrete jumps in an otherwise stable RMSD profile are often a symptom of incomplete PBC correction. Re-running the

trjconvcommand with different options (-pbc clusterfollowed by-pbc nojump) can resolve this [37] [39]. The following sequence is a more robust post-processing protocol:Assessing Convergence and Stability: A stable or "flat" RMSD curve after an initial rise is typically interpreted as the system having reached equilibrium [33]. However, RMSD alone cannot definitively prove convergence, as it is a degenerate metric—different conformational changes can produce the same RMSD value [38]. It should therefore be used in conjunction with other analyses, such as Radius of Gyration (Rg) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), to build a comprehensive picture of protein dynamics [39].