Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Validation and Biomolecular Analysis

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) is a critical metric in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations for quantifying local protein flexibility and validating simulation stability.

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Validation and Biomolecular Analysis

Abstract

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) is a critical metric in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations for quantifying local protein flexibility and validating simulation stability. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational theory of RMSF, its calculation and application in drug discovery projects, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing analyses, and robust methods for validating results against experimental data. By integrating practical guidance with insights from recent studies on targets like SARS-CoV-2 proteases and HPSE, we demonstrate how rigorous RMSF analysis can elucidate mechanisms of ligand binding, allosteric regulation, and ultimately accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

Understanding RMSF: The Cornerstone of Analyzing Protein Flexibility in MD Simulations

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) serves as a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, providing crucial insights into protein flexibility and structural stability at the atomic level. Unlike its counterpart Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which measures global structural changes over time, RMSF quantifies the local flexibility of individual residues or atoms around their average positions [1] [2]. This distinction positions RMSF as an indispensable tool for researchers investigating the relationship between protein dynamics and biological function, particularly in pharmaceutical development where understanding molecular flexibility informs drug design strategies.

In structural biology, RMSF calculations enable scientists to identify rigid and flexible regions within protein structures, mapping functional domains responsible for catalytic activity, ligand binding, and allosteric regulation [3]. The conservation of dynamic patterns across enzyme superfamilies suggests an evolutionary pressure to maintain specific flexibility profiles essential for biological function [3]. This guide examines RMSF from computational, experimental, and applied perspectives, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing RMSF validation within molecular dynamics research.

Theoretical Foundations: RMSF Mathematical Definition and Interpretation

Mathematical Formulation

The RMSF calculation for a biomolecular system follows a standardized mathematical approach. For N atoms over M simulation frames, the RMSF for atom i is calculated as [2]:

RMSF(i) = √(1/M × Σₜ[τᵢ(t) - τ̅ᵢ]²)

Where:

- τᵢ(t) = position vector of atom i at time t

- τ̅ᵢ = time-averaged position of atom i

- M = total number of frames in the trajectory

- The summation runs over all time points in the simulation

This formula computes the standard deviation of atomic positions from their mean location, providing a quantitative measure of positional variability [1] [2]. Typically measured in Ångströms (Å, 10⁻¹⁰ m), RMSF values enable direct comparison of flexibility across different molecular systems [2].

Comparative Analysis: RMSF vs. RMSD

Understanding the distinction between RMSF and RMSD is crucial for proper data interpretation. The table below outlines key differences:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of RMSF and RMSD in Molecular Dynamics

| Feature | RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) | RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Measures local flexibility of individual residues/atoms | Measures global structural change from reference |

| Typical Output | Per-residue/atom value plot vs. residue number | Single value plot over simulation time |

| Biological Insight | Identifies flexible/rigid regions, functional domains | Tracks overall conformational stability, equilibration |

| Reference Structure | Average position over trajectory | Fixed initial or crystal structure |

| Application Example | Identifying flexible binding loops, hinge regions | Monitoring protein folding/unfolding transitions |

Computational Methodologies: RMSF Calculation and Workflow

Standardized Calculation Protocols

RMSF analysis employs specialized software tools implementing the mathematical principles described in Section 2.1. The AMBER molecular dynamics package, particularly its cpptraj module, provides a widely-used implementation requiring careful preparation of input scripts [1]:

This script specifies trajectory input, initial RMSD-based alignment to remove global rotation/translation, and RMSF calculation for protein backbone atoms (Cα, C, N) grouped by residue [1]. The alignment step is critical as it eliminates artifacts from whole-molecule diffusion, ensuring calculated fluctuations reflect internal flexibility rather than global movement.

Alternative computational environments like MDTraj in Python provide complementary approaches:

Experimental Workflow Integration

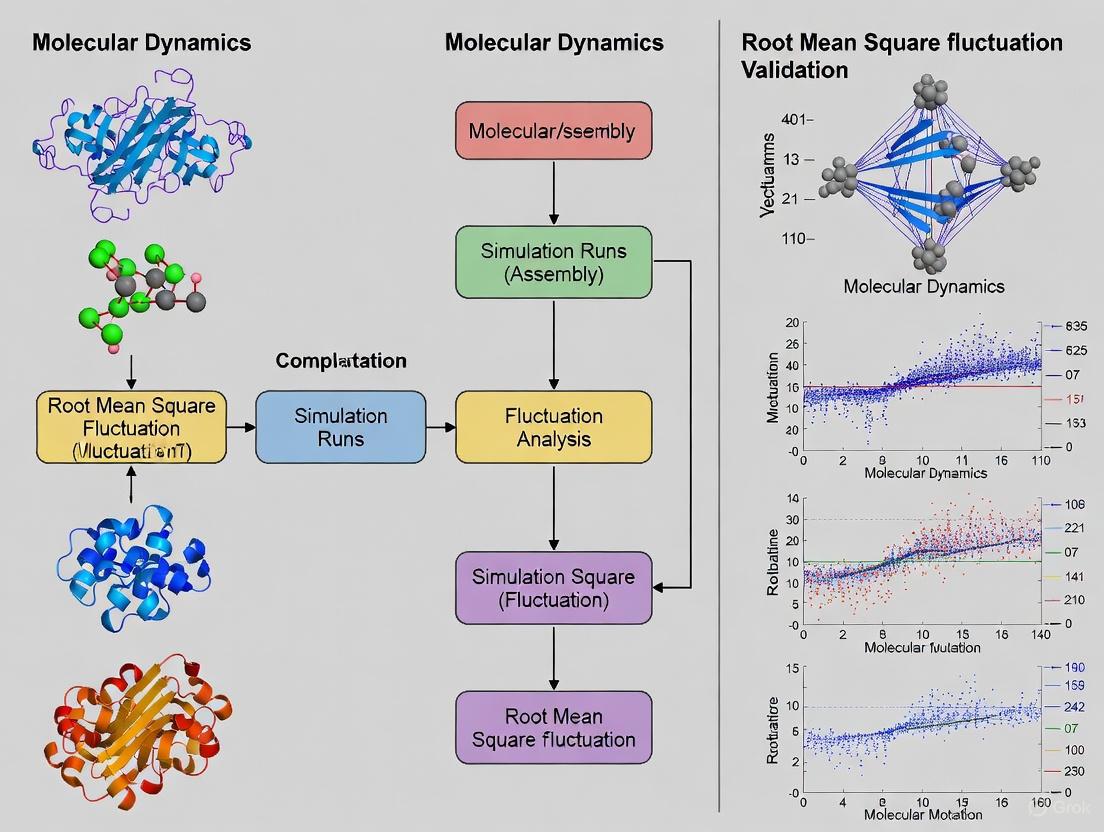

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for RMSF validation in drug discovery research:

Experimental Validation: Correlating Computational and Empirical Data

Biophysical Validation Techniques

While RMSF originates from computational simulations, its biological relevance requires experimental validation through biophysical techniques that probe atomic-level flexibility:

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) serves as the gold standard for experimental RMSF validation, directly measuring atomic positional fluctuations through relaxation parameters (R₁, R₂, and NOE) [3]. These parameters report on ps-ns timescale motions corresponding closely to MD simulation timeframes. For example, studies on pancreatic RNase superfamily members demonstrated conserved dynamic patterns within functional subfamilies, with NMR-derived order parameters validating MD-predicted flexibility profiles [3].

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) provides complementary validation by measuring backbone amide hydrogen exchange rates, reflecting flexibility in secondary structural elements. More flexible regions exhibit higher exchange rates due to increased solvent accessibility from transient structural openings.

Integrated Validation Protocols

Successful RMSF validation employs a hierarchical approach:

- Backbone Atom Validation: Focus initial validation on protein backbone atoms (Cα, N, C) which exhibit more predictable dynamics and have direct NMR observables [1]

- Timescale Correlation: Ensure experimental methods probe similar timescales as MD simulations (typically ps-ns for RMSF)

- Comparative Analysis: Validate relative rather than absolute fluctuation magnitudes between protein regions or related systems

- Mutational Support: Confirm functional significance of flexible regions through targeted mutagenesis of high-RMSF residues

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for RMSF Validation

| Technique | Structural Information | Timescale | Sample Requirements | Complementarity to MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Relaxation | Atomic-resolution dynamics | ps-ns | 0.1-1 mM, ¹⁵N/¹³C-labeled | Direct measurement of atomic fluctuations |

| HDX-MS | Backbone flexibility & solvent accessibility | ms-min | < 1 nmol, unlabeled | Identifies flexible regions with structural context |

| X-ray B-factors | Static disorder in crystal lattice | N/A | Crystallizable protein | Correlates with RMSF but includes crystal packing effects |

| SAXS | Global flexibility & ensemble characteristics | ns-ms | 0.1-1 mg/mL | Validates overall flexibility profiles |

Biological Significance: From Fluctuations to Function

Functional Dynamics in Enzyme Superfamilies

RMSF analysis transcends structural measurement to provide insights into biological function. Studies on pancreatic-type RNase superfamily members revealed that enzymes sharing common chemical and biological functions maintain conserved dynamic patterns despite structural similarities [3]. This conservation of dynamics suggests evolutionary pressure to preserve flexibility profiles essential for function.

In this superfamily, phylogenetic classification grouped sequences into functionally distinct subfamilies with characteristic RMSF profiles. Loop swapping experiments demonstrated that transferring flexible elements could transplant dynamical behavior between homologs, confirming the causal relationship between local flexibility and functional specialization [3].

Allosteric Regulation and Signal Transduction

RMSF effectively maps allosteric networks and signal transduction pathways by identifying residues with correlated fluctuations. In transcriptional complexes like the RNA Polymerase II pre-initiation complex, integrative structural biology approaches combining MD simulations with experimental data revealed dynamic linkages between protein modules [4]. These analyses showed that flexible hinge regions enable the structural transitions necessary for transcription initiation, with RMSF peaks identifying key regulatory sites.

Pharmaceutical Applications: RMSF in Drug Discovery

Binding Stability and Drug-Target Interactions

In pharmaceutical development, RMSF analysis provides critical insights into drug-target interactions and binding stability. Molecular dynamics simulations with RMSF calculations routinely complement docking studies to evaluate how ligand binding affects protein flexibility [5] [6] [7].

A study on emodin derivatives for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment demonstrated that the most potent compound (TAEM) not only showed the strongest binding affinity to EGFR and KIT targets but also induced the most stable binding complex with reduced RMSF values in key binding residues [7]. Similarly, investigations into naringenin's anti-breast cancer activity combined molecular docking with 100ns MD simulations, using RMSF to confirm stable protein-ligand interactions with key targets including SRC, PIK3CA, BCL2, and ESR1 [5].

Mechanism of Action Elucidation

RMSF further contributes to elucidating therapeutic mechanisms of action. Research on dapagliflozin's protective effects against diabetic liver injury employed MD simulations to validate interactions between the drug and key signaling proteins (ERK1/2, IKKβ, NF-κB) [6]. RMSF analysis confirmed that dapagliflozin stabilized specific conformational states in these targets, providing mechanistic insights into its anti-inflammatory effects observed in vitro and in vivo [6].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for RMSF Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for RMSF Studies

| Reagent/Software | Specific Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER cpptraj | RMSF trajectory analysis | Calculates residue-specific fluctuations from MD trajectories [1] |

| MDTraj Python Library | RMSF computation & visualization | Enables programmatic RMSF analysis and integration with data science workflows [1] |

| NMR Isotope Labels (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Experimental dynamics measurement | Validates computational RMSF predictions through relaxation measurements [3] |

| HDX-MS Buffers | Solvent accessibility mapping | Correlates flexible regions with hydrogen exchange rates [3] |

| GPU Computing Clusters | Accelerated MD simulations | Enables µs-timescale simulations for comprehensive sampling [5] [6] [7] |

| Force Fields (AMBER 14SB, GAFF) | Molecular mechanics parameters | Determines accuracy of simulated atomic fluctuations [7] |

RMSF analysis represents a powerful bridge between computational predictions and experimental validation in structural biology and drug discovery. As demonstrated across multiple applications—from enzyme evolution studies to cancer drug development—RMSF provides unique insights into protein flexibility that complement static structural information. The most robust research approaches integrate computational RMSF calculations with experimental validation through NMR, HDX-MS, or functional assays, creating a consensus view of protein dynamics relevant to biological function.

For pharmaceutical researchers, RMSF has become an indispensable tool in the mechanistic toolkit, providing atomic-level explanations for drug efficacy and enabling rational design of compounds that modulate protein flexibility. As MD simulations continue increasing in temporal and spatial scope, RMSF analysis will likely grow correspondingly more sophisticated, potentially revealing dynamical networks underlying complex biological processes and opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The Mathematical Relationship Between RMSF, RMSD, and Experimental B-Factors

In the fields of structural biology and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, accurately describing and validating protein dynamics is fundamental to understanding function, guiding drug design, and interpreting experimental data. Three pivotal metrics used in this endeavor are Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and experimental B-factors (also known as temperature or Debye-Waller factors). While these parameters are often discussed in isolation, a deep understanding of their mathematical and practical interrelationships is crucial for robust molecular dynamics root mean square fluctuation validation research. This guide provides a objective comparison of these metrics, detailing their theoretical connections, the experimental and computational protocols for their determination, and their respective strengths and limitations as revealed by scientific studies.

Defining the Core Metrics

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF)

RMSF measures the local flexibility of a protein structure over time. It quantifies the average deviation of each atom from its mean position throughout a simulation or an ensemble of structures. It is calculated using the formula: $$ \text{RMSF}i = \sqrt{\frac{1}{T} \sum{t=1}^{T} \lVert \mathbf{r}i(t) - \bar{\mathbf{r}}i \rVert^2 } $$ where ( \mathbf{r}i(t) ) is the position of atom ( i ) at time ( t ), ( \bar{\mathbf{r}}i ) is the time-averaged position of atom ( i ), and ( T ) is the total number of time frames. RMSF is therefore a per-atom measure of local stability and flexibility.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

RMSD is a measure of global structural similarity. It calculates the average distance between the atoms of two or more superimposed structures after optimal roto-translation. The pairwise RMSD between two structures is given by: $$ \text{RMSD} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \lVert \mathbf{r}i^{(A)} - \mathbf{r}i^{(B)} \rVert^2 } $$ where ( N ) is the number of atoms, and ( \mathbf{r}i^{(A)} ) and ( \mathbf{r}_i^{(B)} ) are the coordinates of atom ( i ) in structures A and B after alignment. The ensemble-average pairwise RMSD, ( \langle \text{RMSD}^2 \rangle^{1/2} ), provides a single metric for the global structural heterogeneity of an entire ensemble [8].

Experimental B-Factors

In X-ray crystallography, the B-factor describes the smearing of electron density around an atom's center. It is formally defined as ( B = 8\pi^2 \langle u^2 \rangle ), where ( \langle u^2 \rangle ) is the mean-square displacement of the atom from its average position. Assuming isotropic motion, B-factors can be directly related to RMSF through the equation: $$ \text{RMSF}i^2 = \frac{3Bi}{8\pi^2} $$ This equation allows for a direct comparison between atomic fluctuations observed in MD simulations (RMSF) and experimental X-ray data [8].

Mathematical Relationship and Theoretical Framework

The foundational link between these three metrics was rigorously derived by demonstrating that the ensemble-average pairwise RMSD is directly proportional to the average B-factors and thus to the RMSF for a single molecular species [8].

This relationship is elegantly analogous to the two definitions of the radius of gyration (( R_g )) in polymer physics:

- The first definition uses the pairwise distances between all monomers (Eq. 2, analogous to pairwise RMSD).

- The second uses the distance of each monomer from the center of mass (Eq. 3, analogous to RMSF) [8].

The study established that, under a set of conservative assumptions, the root mean-square ensemble-average of an all-against-all distribution of pairwise RMSD, ( \langle \text{RMSD}^2 \rangle^{1/2} ), is mathematically equivalent to the root mean-square average deviation between each structure and the average structure of the ensemble, ( \langle \text{RMSF}^2 \rangle^{1/2} ) [8]. This provides a basis for quantifying the global structural diversity of macromolecules in crystals directly from experimental B-factors. The study estimated that the ensemble-average pairwise backbone RMSD for a typical protein X-ray structure is approximately 1.1 Å, assuming conformational variability is the principal contributor to B-factors [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical and mathematical relationships between these core metrics and the computational workflows used in their analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Metrics and Their Validation

A direct comparison of the properties, applications, and limitations of RMSF, RMSD, and B-factors is essential for selecting the right metric for a given research question.

Table 1: Objective Comparison of RMSF, RMSD, and B-Factors

| Feature | RMSF (from MD) | RMSD (from MD) | Experimental B-Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Information | Local, per-atom flexibility | Global, whole-structure deviation | Apparent atomic displacement from electron density |

| Typical Experimental Use | Analyzing MD simulation trajectories | Monitoring simulation convergence, clustering structures | Assessing local flexibility & disorder in crystal structures |

| Key Strengths | Identifies flexible/rigid regions (e.g., loops vs. cores) | Simple, intuitive measure of overall structural change | Direct experimental observable |

| Key Limitations | Sensitive to force field inaccuracies & sampling | Can be dominated by large motions in flexible regions, masking smaller changes | Contain contributions from conformational disorder, crystal defects, and refinement errors [9] |

| Quantitative Accuracy (from studies) | Varies with force field and MD package [10] | N/A (comparative metric) | Estimated error: ~9 Ų (ambient T), ~6 Ų (cryo T) [9] |

| Reproducibility | High within same simulation setup; varies between force fields/MD packages [10] | High for a given ensemble | Modest; differs between structures of the same protein [9] |

The accuracy of B-factors derived from crystallographic experiments is a critical consideration when using them for validation. A 2022 study that analyzed over 400 structures of Gallus gallus lysozyme estimated the accuracy of B-factors to be approximately 9 Ų for ambient-temperature structures and 6 Ų for low-temperature structures [9]. This level of error, which has shown little improvement over the past two decades, must be considered when comparing simulation-derived RMSF to experimental B-factors, as it sets a fundamental limit on the agreement one can expect [9].

Furthermore, MD simulations themselves are subject to variations that affect the computed RMSF and RMSD. A comparative study using four different MD packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) revealed that while overall agreement with experiment at room temperature was good, there were "subtle differences in the underlying conformational distributions and the extent of conformational sampling" [10]. This indicates that the choice of simulation software and force field can influence the results, leading to ambiguity about which results are most correct.

Table 2: Analysis of B-Factor Limitations and Contributing Factors

| Factor | Impact on B-Factor / RMSF Comparison |

|---|---|

| Static & Dynamic Disorder | B-factors conflate true atomic motion with static conformational variability in the crystal, while RMSF from a single MD simulation typically captures only dynamics [8]. |

| Crystal Packing Contacts | Can restrict motion in crystal, making B-factors lower than RMSF from a solution-state simulation [8]. |

| Refinement Errors & Lattice Defects | Introduce non-physical noise into B-factor values, complicating direct comparison [9]. |

| Overall B-Factor Accuracy | The ~6-9 Ų error implies that differences between simulated and experimental values within this range may not be significant [9]. |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol: Relating Ensemble RMSD to B-Factors

This methodology outlines the procedure for validating the mathematical relationship between ensemble-average RMSD and experimental B-factors, as described in the foundational study [8].

- Generate a Structural Ensemble: Perform molecular dynamics simulations to generate a large ensemble of protein structures. The study used thousands of independent trajectories of the villin headpiece domain generated via the Folding@Home distributed computing project [8].

- Calculate Pairwise RMSD: For a cluster of structures from the ensemble, perform an all-against-all comparison. For each pair of structures, optimally align their backbone atoms (C, N, Cα) and calculate the non-weighted pairwise RMSD [8].

- Compute Ensemble-Average Pairwise RMSD: Calculate the quadratic mean (root mean square) of the entire distribution of pairwise RMSD values to obtain ( \langle \text{RMSD}^2 \rangle^{1/2} ) [8].

- Calculate RMSF from B-Factors: Obtain the experimental B-factors from a high-resolution protein crystal structure (e.g., from the PDB). Convert the B-factors to RMSF values using the equation ( \text{RMSF}i = \sqrt{3Bi / 8\pi^2} ) [8].

- Compare Global Metrics: Calculate the average B-factor, ( \langle B \rangle ), and the quadratic mean of the RMSF, ( \langle \text{RMSF}^2 \rangle^{1/2} ), across the protein backbone atoms. Compare this value to the ensemble-average pairwise RMSD computed in Step 3 to test the theoretical relationship [8].

Protocol: Validating MD Simulations with Experimental B-Factors

This is a common workflow for assessing the accuracy of a molecular dynamics force field by comparing simulation-derived dynamics to experimental data.

- System Setup:

- Obtain initial coordinates from a protein crystal structure (e.g., from the PDB).

- Solvate the protein in an explicit water box (e.g., using TIP4P-EW water models) with ions to neutralize the system [10].

- Simulation Execution:

- Use an MD package (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD) with a modern force field (e.g., AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36).

- Perform energy minimization, followed by equilibration (e.g., in the NVT and NPT ensembles).

- Run production simulations (e.g., multiple independent replicates of 200 ns or longer) under conditions matching the experiment (temperature, pH) [10].

- Trajectory Analysis - RMSF Calculation:

- After aligning the trajectory to a reference structure to remove global rotation and translation, calculate the RMSF for each protein backbone atom.

- Conversion and Comparison:

- Convert the simulated RMSF values to "predicted" B-factors using the inverse relationship: ( Bi^{\text{pred}} = (8\pi^2 / 3) \times \text{RMSF}i^2 ) [8].

- Compare the profile of predicted B-factors directly to the experimental B-factor profile from the crystal structure, typically by calculating a Pearson correlation coefficient or by visual inspection of the per-residue plots.

Protocol: Assessing B-Factor Accuracy from Crystallographic Data

This protocol, derived from a 2022 study, describes how to estimate the intrinsic accuracy of B-factors in the PDB [9].

- Data Curation:

- Select a large set of independent crystal structures of the same wild-type protein (e.g., Gallus gallus lysozyme) determined in the same space group.

- Filter structures to include only those with similar, high-resolution data and without excessive heteroatoms. Separate structures by data collection temperature (ambient vs. cryo) [9].

- Calculation of Differences:

- For each pair of structures (X, Y), compute the absolute difference in B-factors for the same atom A: ( \Delta BA = | B{A,X} - B_{A,Y} | ) [9].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Analyze the distribution of these absolute difference values across all comparable atoms and structures.

- Use normal probability plots (NPPs) to compare the two sets of B-factor data and estimate the typical error [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Data Resources for Dynamics Validation

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [10] | MD Software Package | High-performance MD engine for running simulations and calculating RMSD/RMSF. |

| AMBER [10] | MD Software Package & Force Field | Suite for MD simulation and force fields like ff99SB-ILDN used in dynamics studies. |

| NAMD [10] | MD Software Package | Parallel MD software designed for large biomolecular systems. |

| CHARMM36 [10] | Force Field | Empirical energy function for MD simulations, used in packages like NAMD. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [8] | Database | Repository for experimental protein structures and their associated B-factors. |

| Folding@Home [8] | Distributed Computing Project | Generates massive simulation ensembles for robust statistical analysis of RMSD/RMSF. |

| PMC | Literature Database | Provides open access to critical scientific literature for methodology details. |

The mathematical relationship between RMSF, RMSD, and experimental B-factors provides a powerful framework for bridging computational simulations and experimental data. The derivation showing that ensemble-average pairwise RMSD is proportional to average B-factors establishes a quantitative link between global structural heterogeneity and local atomic fluctuations [8]. However, practitioners must be aware of the significant limitations and errors inherent in both computational and experimental approaches. The accuracy of experimental B-factors is modest, with errors of 6-9 Ų, and has not substantially improved in decades [9]. Meanwhile, MD-derived metrics like RMSF are sensitive to the choice of force field and simulation package [10]. Therefore, successful validation requires not just a theoretical understanding of these relationships but also a critical appreciation of the practical uncertainties in both domains. Future efforts integrating larger simulation ensembles, improved force fields, and more sophisticated crystallographic refinement methods hold the promise of deepening our understanding of protein dynamics.

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that quantifies the deviation of a particle, typically an atom, from its average position over time. It provides crucial insights into protein flexibility by measuring the average magnitude of atomic movements during a simulation, effectively capturing the local deformability of protein regions [11]. In structural biology, RMSF serves as a powerful tool for characterizing regional stability, identifying flexible loops, recognizing rigid domains, and detecting potential allosteric sites—regions where ligand binding can remotely influence protein function [2] [12].

The mathematical foundation of RMSF calculation involves computing the square root of the average squared deviation of atomic positions from their reference structure. For a simulation with T frames and N atoms, the RMSF for atom i is calculated as:

RMSF(i) = √(1/T ∑(t=1 to T) ||ri(t) - ri,ref||²)

where ri(t) is the position of atom i at time t, and ri,ref is its reference position, typically the average structure or the initial coordinates [2]. This calculation produces a profile where peaks indicate high-flexibility regions and troughs correspond to structurally stable areas, providing a quantitative map of protein dynamics essential for understanding function and facilitating drug discovery efforts.

Methodologies for RMSF Analysis and Interpretation

Standard RMSF Calculation Protocols

The standard protocol for RMSF analysis begins with a thoroughly equilibrated MD system. Researchers typically simulate the solvated protein in a physiological buffer (e.g., 150mM NaCl) using periodic boundary conditions at 310K for 50-100 nanoseconds, though longer simulations may be required for complex conformational changes [13] [14]. The simulation box size should provide at least 1.0 nm clearance between the protein and box edges, with energy minimization performed using steepest descent algorithms (approximately 50,000 steps) until the maximum force is <1000 kJ/mol/nm [13]. Following minimization, systems undergo equilibration in two phases: NVT ensemble for 100ps at 310K using the V-rescale thermostat, followed by NPT ensemble for 100ps at 310K and 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, with position restraints applied to protein heavy atoms [13].

For production simulations, the LINCS algorithm constrains bonds involving hydrogen atoms, allowing a 2fs time step, while Particle Mesh Ewald handles long-range electrostatics [13]. Trajectories are typically saved every 10ps for subsequent analysis. RMSF values are calculated after aligning each trajectory frame to a reference structure (usually the initial protein coordinates or an average structure) using backbone atoms to remove global rotation and translation [12]. This alignment is crucial for distinguishing internal protein fluctuations from whole-molecule movement. Specialized software packages like GROMACS, AMBER, or CHARMM implement these calculations, with MDLovoFit offering advanced robust alignment capabilities that automatically identify and align the least mobile substructures for improved interpretation [12].

Advanced Robust Alignment Techniques

Traditional RMSF analysis suffers from a significant limitation: highly mobile regions can dominate the structural alignment, obscuring the accurate quantification of fluctuations in more rigid areas. The MDLovoFit algorithm addresses this through a Low-Order-Value-Optimization (LOVO) strategy that iteratively identifies and aligns the most rigid substructures [12]. The algorithm proceeds through six key steps: (1) compute per-atom deviations after initial alignment; (2) sort these deviations in increasing order; (3) select the fraction φ (φ < 1) of atoms with smallest deviations; (4) perform rigid-body alignment using only this subset; (5) apply the resulting translation/rotation to the entire structure; (6) iterate until convergence of the mean square displacement of the selected subset [12]. This approach automatically identifies rigid cores without prior knowledge, providing a clearer picture of structural fluctuations and enabling more accurate quantification of flexibility patterns relevant to biological function.

Table 1: Comparison of RMSF Analysis Methods

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard RMSF | Alignment to reference structure using all atoms | Simple implementation; Intuitive interpretation | Mobile regions dominate alignment; May obscure local flexibility |

| MDLovoFit | Iterative alignment of least-mobile substructures | Automatic rigid core identification; Robust to high-flexibility regions | Computationally more intensive; Requires parameter tuning (φ) |

| Principal Component Analysis | Projection of motions onto collective coordinates | Identifies correlated motions; Separates global from local dynamics | Complex interpretation; Requires significant structural sampling |

| Time-dependent RMSF | Calculation over different trajectory segments | Captures temporal flexibility changes; Identifies conformational transitions | Requires long simulations; Sensitive to sampling quality |

Experimental Validation Correlations

Validating computational RMSF predictions requires integration with experimental data. X-ray crystallography B-factors (temperature factors) provide the most direct experimental correlate to RMSF, as both parameters quantify atomic displacement [11]. High correlation between predicted RMSF and experimental B-factors strengthens the validity of MD simulations. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers additional validation through residual dipolar couplings and order parameters that reflect bond vector mobility [15]. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) increasingly contributes to flexibility analysis through variability in reconstructed densities across multiple particles [15]. For allosteric proteins, biochemical assays measuring functional changes upon mutagenesis of predicted flexible or rigid regions can confirm computational predictions [16] [17]. This multi-technique validation framework ensures RMSF interpretations reflect biological reality rather than computational artifacts.

Interpreting RMSF Profiles for Protein Structural Elements

Identifying Rigid Domains

Rigid domains in RMSF profiles appear as troughs or flat regions with low fluctuation values (typically <1.0 Å), indicating structural regions that maintain their conformation throughout simulations [12]. These regions frequently correspond to secondary structure elements like α-helices and β-sheets that form the stable core of protein domains. In enzymatic proteins, catalytic domains often display coordinated rigidity that maintains precise atomic positioning for substrate binding and chemical transformation [11]. Rigid domains identified through RMSF analysis frequently serve as structural anchors that facilitate allosteric communication by transmitting rather than absorbing conformational changes [17].

The functional significance of rigid domains extends beyond mere structural stability. In allosteric proteins like beta-lactamases, rigid domains form conserved architectural elements that enable long-range communication between distinct binding sites [17]. Similarly, in kinases, rigid domains provide the structural framework upon which functional motions occur, with specific rigid elements crucial for coordinating conformational changes during catalytic cycles [17]. When analyzing RMSF profiles, consistently low fluctuations across multiple parallel simulations strongly suggest genuine structural rigidity rather than sampling limitations. MDLovoFit significantly enhances rigid domain identification by specifically aligning structures based on their most rigid components, preventing highly flexible regions from obscuring genuine stability patterns [12].

Characterizing Flexible Loops

Flexible loops manifest as distinct peaks in RMSF profiles, with fluctuation values often exceeding 2.0 Å and sometimes reaching 4-5 Å for highly mobile regions [11]. These regions typically correspond to solvent-exposed loops connecting secondary structure elements, where reduced structural constraints permit greater mobility. Beyond their obvious role in linkers connecting structured domains, flexible loops frequently participate in critical biological functions, including substrate access to active sites, ligand binding and release, and conformational switches that regulate protein activity [11] [14].

In the SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro), MD simulations revealed significant flexibility in loops surrounding the substrate-binding sites S3, S4, and SUb2, enabling conformational adaptations necessary for substrate recognition and catalysis [14]. Similarly, in allosteric studies of beta-lactamases, flexible loops function as dynamic gates that control access to active sites, with their motions directly influencing antibiotic resistance profiles [17]. When interpreting loop flexibility, it's essential to distinguish between intrinsic flexibility relevant to biological function and simulation artifacts resulting from insufficient sampling. Complementary analyses, such as examination of hydrogen bonding patterns, solvation, and contact maps, can help validate the biological significance of predicted flexible loops.

Detecting Allosteric Sites

Allosteric sites represent particularly valuable targets in drug discovery due to their potential for precise functional modulation. In RMSF profiles, allosteric regions often exhibit intermediate flexibility—more rigid than surface loops but more flexible than core structural domains—with values typically ranging from 1.0-2.0 Å [16] [17]. These regions may display distinctive dynamic patterns when comparing apo and holo simulations, with allosteric binding sites frequently showing reduced flexibility upon ligand binding while simultaneously inducing flexibility changes at distant active sites [16].

Molecular dynamics simulations have proven exceptionally valuable for identifying cryptic allosteric sites—transient pockets not visible in static crystal structures. In studies of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase (BCKDK), conventional crystallography failed to reveal certain allosteric sites, while MD simulations captured conformational transitions that exposed these cryptic pockets [16]. Enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and accelerated MD further facilitate allosteric site discovery by promoting transitions between conformational states [16]. For example, metadynamics applies bias potentials to collective variables to accelerate exploration of conformational space, while replica exchange MD simulates multiple copies at different temperatures to enhance sampling efficiency [16].

Table 2: Characteristic RMSF Values for Protein Structural Elements

| Structural Element | Typical RMSF Range | Functional Significance | Drug Targeting Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Domains | 0.5 - 1.0 Å | Structural stability; Catalytic precision | Orthosteric site targeting; Stability enhancement |

| Allosteric Sites | 1.0 - 2.0 Å | Signal transmission; Regulatory control | Allosteric modulators; Specific regulation |

| Flexible Loops | 2.0 - 5.0 Å | Substrate access; Conformational switching | Difficult to target directly; Stabilization strategies |

| Termini | 1.5 - 4.0 Å | Often inherently flexible | Limited direct targeting; Engineering opportunities |

Integrated Workflow for RMSF-Based Analysis

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process for interpreting RMSF profiles to identify structural elements and allosteric sites:

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for RMSF-based analysis of protein dynamics, from trajectory processing to functional interpretation.

Research Reagent Solutions for RMSF Analysis

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RMSF Analysis

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Simulation Engine | Production MD simulations | High performance; Free software; Extensive analysis tools |

| AMBER | MD Simulation Suite | Production MD simulations | Force field development; Enhanced sampling; Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics |

| MDLovoFit | Robust Trajectory Alignment | RMSF calculation | Automatic rigid substructure identification; Improved flexibility quantification |

| drMD | Automated MD Pipeline | Accessibility for non-experts | User-friendly interface; Automated protocols; Open source |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Allosteric ligand screening | Template-independent blind docking; Binding pose prediction |

| PASSer | Allosteric Site Prediction | Allosteric drug discovery | Machine learning approach; High prediction accuracy |

| PyMOL | Molecular Visualization | Structural interpretation | Publication-quality graphics; Plugin architecture |

| CHARMM-GUI | System Preparation | Simulation setup | Web-based interface; Membrane system building |

RMSF analysis represents a powerful approach for deciphering protein dynamics and linking structural flexibility to biological function. Through rigorous application of the methodologies outlined in this guide—including robust alignment strategies, multi-technique validation, and integrated workflow implementation—researchers can reliably identify rigid domains, characterize flexible loops, and detect allosteric sites from MD simulations. The continuing integration of machine learning approaches with traditional RMSF analysis promises further advances in predictive accuracy and biological insight [18] [15]. As these computational methodologies mature alongside experimental validation techniques, RMSF profiling will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technique in structural biology and rational drug design, enabling researchers to bridge the crucial gap between static structures and dynamic function.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, analyzing protein dynamics and conformational heterogeneity is crucial for understanding biological function. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), root mean square deviation (RMSD), and principal component analysis (PCA) represent three foundational analytical techniques that operate across complementary spatiotemporal scales. This guide objectively compares their performance, demonstrating that RMSF does not merely duplicate but critically integrates information from both global trajectory (RMSD) and collective motion (PCA) analyses. Experimental data and case studies reveal that RMSF provides unique, residue-level insights into flexibility that are essential for interpreting RMSD convergence and PCA subspace dimensions, effectively bridging local fluctuations with global conformational changes.

MD simulations generate vast amounts of data on protein motion, necessitating robust analytical methods to extract meaningful biological insights. RMSD, RMSF, and PCA form a core triad of approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations.

- RMSD quantifies global structural drift over time, typically relative to an initial reference structure, helping researchers identify when a simulation has stabilized (reached equilibrium) and characterize large-scale conformational transitions [2] [1].

- RMSF measures local flexibility of individual residues, calculating the average deviation of each atom from its mean position. This residue-level analysis identifies flexible loops, hinge regions, and rigid structural elements crucial for function and ligand binding [2] [1].

- PCA identifies collective motions by projecting trajectory data into a low-dimensional space defined by the largest variances. It separates large-scale, correlated motions that often underlie biological function from uncorrelated background noise [19] [20].

The thesis of this work is that RMSF provides an indispensable bridge that connects the global stability information from RMSD with the correlated motion patterns revealed by PCA, creating a more complete picture of protein dynamics than any single metric can provide.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Definitions

Fundamental Equations and Their Physical Interpretations

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures [2]:

- Equation: ( \text{RMSD}(t) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \| \mathbf{x}i(t) - \mathbf{x}_i^{\text{ref}} \|^2 } )

- Parameters: ( N ) atoms, position ( \mathbf{x}i(t) ) of atom ( i ) at time ( t ), reference position ( \mathbf{x}i^{\text{ref}} )

- Application: Typically calculated after optimal rigid-body alignment to remove rotational and translational motion [2] [21].

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) quantifies the average fluctuation of each atom around its mean position [22] [2]:

- Equation: ( \text{RMSF}(i) = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{T} \sum{t=1}^{T} \| \mathbf{x}i(t) - \bar{\mathbf{x}}_i \|^2 } )

- Parameters: ( \bar{\mathbf{x}}_i ) is the time-averaged position of atom ( i ) over trajectory frames

- Application: Usually calculated for Cα atoms to analyze residue-level flexibility [19] [1].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identifies dominant conformational changes through eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix built from atomic coordinates [19] [20].

Analytical Complementarity Visualized

The following diagram illustrates how these three analyses connect to provide a comprehensive view of protein dynamics:

Experimental Comparisons and Performance Benchmarks

Case Study: Shikimate Kinase Conformational Sampling

A comparative study of autoencoder models trained on MD data of Shikimate Kinase demonstrated the complementary nature of these analyses [19]. The enzyme's three flexible domains (SB, β, and LID) showed characteristic patterns across methods:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Shikimate Kinase Dynamics from MD and Machine Learning Models

| Method | RMSD Peak (Å) | Domain Flexibility Pattern | PCA Sampling | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD (Reference) | 2.4 | All three domains show high flexibility | Broad coverage | Ground truth ensemble |

| Variational Autoencoder | 2.25 | Similar pattern to MD | Learns structural patterns from dynamics | Good correlation (SpCC ~0.99) |

| Wasserstein Autoencoder | 2.25 | Reduced fluctuations | Limited exploration | Captures trends but underestimates flexibility |

| Denoising Autoencoder | ~2.25 | Significantly reduced fluctuations | Highly restricted | Oversmoothing of flexible regions |

The study found that while generated structures showed excellent Spearman correlation coefficients (~0.99) with original MD data, RMSF analysis revealed that machine learning models systematically underestimated flexibility, particularly in the LID domain [19]. This critical insight would be missed by examining only RMSD or PCA projections.

Performance Metrics Across Biological Systems

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Different Protein Systems

| Protein System | RMSD Convergence Time (ns) | High RMSF Regions | PCA Dominant Motions | Integrated Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB3 Domain | 2-4 (by lagged RMSD) [21] | Border regions of secondary structures [23] | First 2-3 PCs explain ~70% variance [23] | RMSF peaks correspond to essential subspace dimensions |

| TCR-pMHC Complexes | 20-50 (dependent on system) [21] | Complementary determining regions, peptide interface | Binding groove deformation modes | Combined analysis reveals allosteric communication |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro | Varies with inhibitors | Catalytic dyad (His41, Cys145), flexible loops [24] | Domain motions correlated with substrate binding | RMSF validates PCA-clustered conformational states [24] |

| Short Antimicrobial Peptides | Highly variable (unstable) [25] | Terminal residues, hydrophobic cores [25] | Limited collective motions (small systems) | RMSF guides algorithm selection (AlphaFold vs PEP-FOLD) [25] |

Methodological Protocols for Integrated Analysis

Standardized Workflow for Correlation Analysis

Trajectory Preparation and Alignment

- Load trajectory and topology files using MD analysis frameworks (MDTraj, cpptraj) [1]

- Superimpose all frames to a reference structure (usually the first frame or average structure) using backbone atoms (C, CA, N) to remove global rotation/translation [1]

- Specific command (cpptraj):

rmsd @C,CA,N first[1]

RMSD Convergence Analysis

- Calculate time-lagged RMSD using block averaging approaches to identify equilibrium phases [21]

- Apply Hill equation fitting: ( \text{RMSD}(\Delta t) = \frac{a \cdot \Delta t^\gamma}{\tau + \Delta t^\gamma} ) to quantify saturation behavior [21]

- Exclude initial non-equilibrium phase (typically 10-20% of trajectory) from subsequent analyses [21]

RMSF Calculation and Mapping

- Compute per-residue fluctuations using backbone atoms:

atomicfluct out rmsf.dat @C,CA,N byres[1] - Map high-RMSF regions onto protein structure to identify flexible loops, hinges, and binding interfaces

- Correlate with secondary structure – typically, loops show 2-3× higher RMSF than structured elements [23]

PCA and Dimensionality Reduction

- Build covariance matrix of atomic positions after alignment

- Perform eigenvalue decomposition to obtain principal components (PCs)

- Project trajectory onto first 2-3 PCs to visualize conformational clustering [19] [20]

- Identify functional motions by analyzing atomic displacements in dominant PCs

Cross-Analysis Validation

- Color structures by RMSF and visualize along PC projections

- Check consistency – high-RMSF regions should contribute significantly to dominant PCs

- Relate RMSD jumps to transitions between PCA-clustered states

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Integrated MD Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [21] | MD simulation engine with built-in analysis | RMSD/RMSF calculation during production simulations |

| AMBER/cpptraj [22] [1] | Trajectory analysis toolkit | Professional RMSF calculation with extensive atom selection options |

| MDTraj (Python) [1] | Lightweight trajectory analysis | Rapid prototyping and custom analysis scripts |

| EnsembleFlex [20] | Ensemble analysis suite | Integrated RMSD/RMSF/PCA with clustering and visualization |

| BioEmu [26] | Neural emulator for conformation sampling | Generating structural ensembles beyond MD sampling limitations |

| RMSF-net [22] | Deep learning for flexibility prediction | Predicting RMSF from cryo-EM maps in seconds instead of MD simulations |

| VMD [19] | Molecular visualization and analysis | Visualization of RMSF-mapped structures and dynamic properties |

Discussion: Bridging the Scales of Protein Motion

The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that RMSF serves as the critical connection between global and local analyses. In the GB3 domain study, MD simulations using modern force fields (OPLS-AA, AMBER ff99SB, ff03) overestimated backbone flexibility at secondary structure borders compared to NMR experiments – a discrepancy clearly visible in RMSF profiles but obscured in overall RMSD [23]. This highlights RMSF's precision in identifying force field limitations.

For drug discovery applications, particularly against SARS-CoV-2 main protease, RMSF analysis revealed that despite stable global RMSD (<2Å), specific flexible loops surrounding the catalytic site showed elevated fluctuations (>3Å) that directly impacted inhibitor binding [24]. These local flexibility patterns correlated with essential motions identified by PCA, enabling researchers to distinguish true allosteric mechanisms from random fluctuations.

In studies of short antimicrobial peptides, where traditional RMSD analysis often fails due to inherent instability, RMSF emerged as the decisive metric for evaluating computational models [25]. The finding that "PEP-FOLD gives both compact structure and stable dynamics for most of the peptides" was derived primarily from RMSF comparisons, guiding algorithm selection based on peptide physicochemical properties [25].

Emerging machine learning approaches like BioEmu [26] and RMSF-net [22] further validate this integrative framework. RMSF-net specifically demonstrates that RMSF patterns can be predicted from cryo-EM density maps, achieving correlation coefficients of 0.765±0.109 with actual MD simulations [22] – providing a rapid bridge between experimental data and dynamic insights that previously required massive computational resources.

Through rigorous comparative analysis across diverse protein systems, RMSF establishes itself not as a redundant metric but as an essential bridging analysis that connects the global perspective of RMSD with the collective motion description of PCA. For researchers and drug development professionals, this integrated analytical approach provides a more complete, multiscale understanding of protein dynamics. The experimental protocols and toolkit resources outlined here offer a practical roadmap for implementing this powerful trifecta of analyses, ensuring that critical insights into protein flexibility and function are no longer obscured by the limitations of any single analytical method.

The Critical Role of RMSF in Validating the Equilibration and Convergence of MD Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that provides atomic-level insights into the structural and dynamic behavior of biomolecules, complementing experimental approaches [27]. A fundamental, yet often overlooked, assumption in most MD studies is that the simulated system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium, ensuring that the measured properties are converged and reliable [27]. The failure to verify this assumption can profoundly invalidate simulation results, raising a critical question for the field: are the conclusions drawn from many MD studies even valid? [27]

The process typically begins with an experimentally derived structure, which exists under non-physiological conditions (e.g., a crystal lattice) and is therefore not in equilibrium for a solution-state simulation [27]. The system undergoes energy minimization and equilibration steps to relax. However, determining when true equilibrium is attained is challenging. While properties like potential energy and the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) relative to the starting structure are commonly used to check for equilibration, their limitations are severe [28]. Visual inspection of RMSD plots has been shown to be highly subjective and unreliable, with scientists showing no mutual consensus on the point of equilibrium, their decisions biased by factors such as plot scaling and color [28].

This context underscores the necessity for robust, quantitative metrics to assess equilibration and convergence. Among these, Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) serves as a critical tool. RMSF measures the standard deviation of atomic positions over time, typically after fitting the structures to a reference frame to remove global translational and rotational motion [29]. It provides a residue-by-residue or atom-by-atom picture of structural flexibility and local stability, offering a more granular and informative view of system behavior than global RMSD alone.

RMSF and B-Factors: A Bridge Between Simulation and Experiment

RMSF is intrinsically linked to experimental observables, most notably the B-factor (or temperature factor) found in crystal structures of proteins and other biomolecules. The B-factor quantifies the smearing of electron density around an atom, which arises from both static disorder and dynamic atomic motion [30].

A key mathematical derivation shows that, under a set of conservative assumptions, the ensemble-average pairwise RMSD for a molecular species is directly related to the average B-factors [30]. This relationship provides a formal basis for quantifying global structural diversity from experimental data. In practice, MD suites like GROMACS include functionalities to directly convert calculated RMSF values into B-factors, which can then be written to a PDB file for straightforward comparison with experimental structures [29]. This direct comparability makes RMSF an indispensable metric for validating the realism of a simulation against experimental data. If the pattern of flexibility from the simulation (RMSF) matches the pattern of disorder from the crystal structure (B-factors), it increases confidence that the simulation is accurately capturing the molecule's native dynamics.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing MD Convergence and Their Characteristics

| Metric | Description | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSF | Standard deviation of atomic positions after fitting [29]. | Measuring local flexibility and stability; validating against experimental B-factors [30] [29]. | Direct link to experiment; per-residue insight. | Requires a stable reference; sensitive to fitting procedures. |

| RMSD | Global measure of structural drift from a reference structure [21]. | Initial, coarse assessment of structural stability. | Intuitive measure of global change. | Unreliable for determining equilibrium; insensitive to local changes [28]. |

| "Lagged RMSD" | RMSD between configurations separated by a specific time lag, Δt [21]. | Assessing the convergence of structural sampling over time. | Probes structural memory decay; more specific than standard RMSD. | Computationally intensive; requires long trajectories. |

| Energy | Total potential or kinetic energy of the system. | Monitoring the stability of fundamental thermodynamic quantities. | Essential for establishing thermal equilibrium. | Can plateau before structural equilibrium is achieved [31]. |

Comparative Analysis of Convergence Metrics: Why RMSF is Indispensable

While several metrics are available, a comparative analysis reveals the unique value of RMSF while also highlighting the importance of a multi-metric approach.

The Pitfalls of Relying Solely on RMSD

The RMSD of a biomolecule with respect to its starting structure is one of the most ubiquitous plots in MD literature. A plateau in the RMSD time series is often intuitively taken as a sign that the system has equilibrated. However, this method is fraught with subjectivity. A formal survey of scientists demonstrated that there is no consistent agreement on where equilibrium begins based on RMSD plots, with decisions being influenced by non-scientific factors like graph scaling and color [28]. Furthermore, a system can become trapped in a local energy minimum, leading to a stable RMSD that gives a false impression of global equilibrium, while significant conformational degrees of freedom remain unexplored [27].

The "Lagged RMSD" Analysis

This advanced RMSD-based method offers a more robust check for non-convergence. Instead of measuring deviation from time zero, it calculates the average RMSD between all pairs of configurations in the trajectory separated by a specific time interval, Δt [21]. The resulting curve, RMSD(Δt), is then modeled, for instance, with a Hill equation. Unless the RMSD(Δt) function reaches a stationary shape (a plateau), the simulation has not converged, as the structures continue to "drift" further apart over increasing time lags [21]. This method is a powerful tool to judge if a simulation has not run long enough.

The Critical Role of RMSF

RMSF provides a critical layer of analysis that complements global metrics. Its utility in convergence validation is multi-faceted:

- Detection of Localized Instability: Global RMSD or energy can appear stable while individual regions of the molecule, such as flexible loops or terminal, remain unstable. RMSF readily identifies these localized dynamics, preventing premature conclusions about the system's overall equilibrium [31].

- Indicator of "Partial Equilibrium": A system can be in partial equilibrium where some properties have converged while others have not [27]. The stabilization of RMSF profiles for specific domains or the entire backbone, especially when it aligns with experimental B-factor trends, is strong evidence that at least the structural sampling of local fluctuations has converged, even if rare, large-scale transitions have not.

- Revealing Underlying Heterogeneity: Studies on complex systems like hydrated amorphous xylan have shown that standard indicators (density, energy) can remain constant while the system undergoes slow processes like phase separation [31]. Parameters coupled to structural and dynamical heterogeneity, like RMSF, are essential to detect such phenomena and confirm true equilibration, which in some cases may require microsecond-long simulations [31].

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for validating MD equilibration that integrates RMSF with other key metrics:

A workflow for validating MD equilibration integrating RMSF with other metrics.

Experimental Protocols for RMSF Validation in Practice

Standard Protocol for RMSF Calculation and Analysis

A typical protocol for using RMSF in convergence validation, as implemented in tools like GROMACS's gmx rmsf, involves several key steps [29]:

- Trajectory Preparation: A production trajectory is generated after initial minimization and equilibration. To ensure analysis of equilibrated data, an initial portion of the trajectory (e.g., the first 10-100 ns) is often discarded as "additional equilibration."

- Least-Squares Fitting: Each frame of the trajectory is fit to a reference structure (e.g., the initial or an average structure) on a selected set of atoms (e.g., protein backbone atoms) to remove global rotation and translation. This step is crucial for isolating internal fluctuations [29].

- RMSF Calculation: The RMSF for each atom i is calculated as the square root of the time-average of the squared deviation from its mean position: RMSFᵢ = √⟨(rᵢ(t) - ⟨rᵢ⟩)²⟩, where rᵢ(t) is the position of atom i at time t and ⟨rᵢ⟩ is its time-averaged position [29].

- Time-Blocked Analysis: To test for stability, the trajectory is split into consecutive blocks (e.g., two or three blocks). The RMSF is calculated independently for each block. A converged simulation will show similar RMSF profiles across all blocks, indicating that the pattern of flexibility is no longer changing with time.

- Comparison with Experiment: The calculated RMSF values are converted to B-factors using the formula Bᵢ = 8π² * (RMSFᵢ)² / 3 and written to a PDB file [29]. The correlation between the simulated and experimental B-factor profiles provides a strong, objective validation of the simulation's realism.

Case Study: Ligand Binding Validation

In a study targeting Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), RMSF played a pivotal role in validating the stability of a phytochemical lead molecule (2-hydroxynaringenin) bound to the Androgen Receptor (AR). After performing molecular docking, researchers subjected the complex to a multi-nanosecond MD simulation. The stability of the complex and the convergence of the simulation were evaluated by analyzing the RMSF of the protein backbone and the ligand. The low and stable RMSF values observed for both provided critical evidence that the protein-ligand complex had reached a stable equilibrium, thereby validating the binding pose identified by docking and supporting the conclusion of a high-binding affinity interaction [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulation and RMSF Analysis

| Tool/Reagent Name | Type | Primary Function in RMSF/MD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software Suite | A high-performance MD simulation package; its gmx rmsf module is used specifically for calculating RMSF and converting it to B-factors [29]. |

| AMBER | Software Suite | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs that includes tools for trajectory analysis, including RMSF calculation. |

| CHARMM | Software Suite | A versatile program for atomic-level simulation, including energy minimization, dynamics, and trajectory analysis (RMSD, RMSF). |

| GROMOS Force Field | Parameter Set | A family of force fields integrated with GROMACS; used to define energy functions and parameters for MD simulations [21]. |

| AlphaFold | Modeling Algorithm | A deep learning-based system for highly accurate protein structure prediction; often used to generate initial structures for simulation when experimental structures are unavailable [25]. |

| PEP-FOLD | Modeling Algorithm | A de novo approach for predicting peptide structures from amino acid sequences; useful for simulating short peptides [25]. |

| RaptorX | Web Server | A tool for predicting secondary structure, solvent accessibility, and disordered regions of proteins, which can inform RMSF expectations [25]. |

| UCSF Chimera | Visualization & Analysis | A highly extensible program for interactive visualization and analysis of molecular structures and trajectories, including RMSF and B-factor analysis. |

| VADAR | Web Server | A volume, area, dihedral angle, and RMSF analyzer used for comprehensive assessment of protein structures from PDG files. |

In the critical task of validating the equilibration and convergence of MD simulations, RMSF emerges as an indispensable metric that transcends the capabilities of global measures like RMSD. Its strength lies in its granularity, providing a residue-specific view of stability, its direct link to experimental observables through B-factors, and its sensitivity to localized dynamics that can persist even when a system appears globally stable. While no single metric can definitively prove that a simulation has achieved full thermodynamic equilibrium and sampled all relevant conformational space, the consistent stabilization of the RMSF profile, especially when validated against experimental data and supported by other convergence checks like lagged RMSD analysis, provides a robust and multi-faceted argument for partial equilibrium at a minimum. For researchers in drug development and structural biology, incorporating this rigorous, RMSF-informed protocol is essential for ensuring that the insights derived from MD simulations are built upon a reliable and validated foundation.

Calculating and Applying RMSF in Drug Discovery: From Theory to Practice

A Step-by-Step Workflow for RMSF Calculation in GROMACS and AMBER

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that quantifies the deviation of individual atoms or residues from their average positions over time. Unlike Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which measures global structural changes, RMSF provides insights into local flexibility, identifying rigid and mobile regions within a protein structure [33] [1]. This measurement is crucial for validating simulation stability and understanding biological function, particularly in drug development where flexibility influences binding site accessibility and allosteric regulation.

Within the broader context of molecular dynamics validation research, RMSF analysis serves as a critical bridge between computational predictions and experimental observations. The RMSF (ρ) for a given atom i is calculated as the square root of the variance of its positional fluctuations: ρ~i~ = √⟨(r~i~ - ⟨r~i~⟩)²⟩, where r~i~ represents the atomic coordinates and ⟨r~i~⟩ denotes the average position [34] [33]. This quantitative approach allows researchers to identify regions of structural stability and flexibility, providing invaluable insights for interpreting simulation data within pharmacological and structural biology applications.

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Significance

RMSF Mathematical Formalism and Interpretation

The RMSF calculation provides a time-averaged measure of atomic positional variability around the mean structure. A region characterized by high RMSF values indicates significant divergence from the average position and therefore high structural mobility, whereas low RMSF values suggest more rigid regions that maintain their structural integrity throughout the simulation [33]. This distinction is particularly valuable for identifying flexible loops, terminal regions, and dynamic domains that may play crucial roles in molecular recognition and function.

For meaningful RMSF analysis, the system must first reach equilibrium, typically confirmed through RMSD plateauing [33] [1]. The calculation requires structural alignment (fitting) to a reference frame to remove overall translational and rotational motion that would otherwise dominate the fluctuation measurements [29] [34]. In protein studies, RMSF is commonly calculated for Cα atoms, which represent backbone flexibility, though it can be extended to side chains for investigating specific interactions [33].

Relationship to Experimental Observables

RMSF values can be directly converted to crystallographic B-factors using the relationship B = 8π²⟨ρ²⟩/3, allowing direct comparison with experimental X-ray diffraction data [29] [34] [33]. This conversion enables researchers to validate their simulation parameters and force field choices against empirical structural data. The gmx rmsf module includes functionality to output PDB files with B-factors derived from RMSF values, facilitating visualization in molecular graphics software like PyMOL or VMD [29] [33].

Table: Key Differences Between RMSD and RMSF in MD Analysis

| Feature | RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) | RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Measures global structural change | Measures local flexibility |

| Reference | Typically uses initial frame | Uses average structure over trajectory |

| Plotting | Versus time | Versus residue or atom number |

| Application | System equilibration assessment | Identification of flexible/rigid regions |

| Biological Insight | Overall structural stability | Domain mobility, binding sites, allosteric regions |

RMSF Calculation in GROMACS: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Preparation and Basic Command Implementation

The GROMACS gmx rmsf module provides a comprehensive toolkit for calculating atomic fluctuations from MD trajectories. A fundamental workflow begins with these essential steps:

Trajectory Preparation: Ensure your trajectory (

traj.xtc) and run input file (topol.tpr) are properly prepared. For accurate results, use the equilibrated portion of your trajectory by specifying time ranges with the-b(begin time) and-e(end time) flags [29] [33].Basic RMSF Calculation: Execute the core command to compute fluctuations:

This command generates an output file (

rmsf.xvg) containing RMSF values. The-resflag instructs GROMACS to compute the average fluctuation per residue rather than per atom [29] [33].Atom Selection: When prompted, select

C-alphato analyze backbone fluctuations, which provides the most biophysically relevant information about protein flexibility [33].

Advanced Applications and Output Options

Beyond basic fluctuation analysis, GROMACS offers several specialized outputs for enhanced structural interpretation:

B-factor Conversion: To convert RMSF values to B-factors and write them to a PDB file for visualization:

The resulting

bfac.pdbfile can be opened in molecular visualization software, where B-factor values are typically represented by color gradients, allowing immediate identification of flexible regions [29] [33].Anisotropic Displacement Parameters: For more sophisticated analyses of directional fluctuations, use the

-anisoflag to compute anisotropic temperature factors, which output ANISOU records in the PDB format [29].Trajectory Frame Selection: To analyze specific temporal segments of your simulation, incorporate the

-band-eflags. For example, to analyze only the production phase from 1000 ps to 10000 ps:This excludes equilibration phases where the structure hasn't stabilized [33].

The following diagram illustrates the complete GROMACS RMSF analysis workflow:

RMSF Calculation in AMBER/CPPTRAJ: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Input Preparation and CPPTRAJ Execution

The AMBER software suite employs CPPTRAJ for trajectory analysis, including RMSF calculations. The implementation differs from GROMACS but produces equivalent physical insights:

Input File Creation: Create a text file (e.g.,

rmsf.in) containing the analysis commands:The

rmsdcommand aligns each frame to the first frame using the protein backbone (C, CA, N atoms) to remove overall rotation and translation. Theatomicfluctcommand with thebyresflag calculates the average fluctuation per residue [34] [1].Script Execution: Run CPPTRAJ using your topology file and the input script:

This generates

rmsf.datcontaining residue indices and their corresponding RMSF values [1].

Advanced Features and Mass-Weighting Options

CPPTRAJ offers specialized functionality for specific research applications:

B-factor Calculation: The

atomicfluctcommand can directly compute B-factors using thebfactorkeyword, which squares the RMSF values and applies the appropriate conversion factor [34].Mass-Weighted Fluctuations: By default, CPPTRAJ calculates mass-weighted fluctuations, which account for atomic mass differences, providing more physically accurate representations of molecular motions [34].

Anisotropic Displacement Parameters: Similar to GROMACS, CPPTRAJ can compute anisotropic parameters using the

calcadpkeyword, which automatically implies B-factor calculation [34].

A comprehensive CPPTRAJ workflow for coordinate averaging, fitting, and fluctuation calculation can be implemented in a single execution sequence [34]:

Comparative Analysis of GROMACS and AMBER Methodologies

Command Structure and Implementation Differences

While both packages compute equivalent physical properties, their command structures and theoretical approaches reveal significant philosophical differences in MD analysis:

Table: Command Comparison for RMSF Analysis Tasks

| Analysis Task | GROMACS Command | AMBER/CPPTRAJ Command |

|---|---|---|

| Basic RMSF | gmx rmsf -f traj.xtc -s topol.tpr -o rmsf.xvg |

atomicfluct out rmsf.dat @C,CA,N |

| Per-residue | -res flag |

byres keyword |

| B-factor | -oq bfac.pdb |

bfactor keyword |

| Anisotropic | -aniso flag |

calcadp keyword |

| Reference | Structure file (-s) |

rmsd first (before atomicfluct) |

| Fitting | -fit (enabled by default) |

Separate rmsd command |

GROMACS employs an integrated command approach where fitting and fluctuation calculation occur within a single command, while CPPTRAJ utilizes a modular strategy where each operation is specified sequentially [29] [34] [1]. This distinction reflects GROMACS's design as an integrated toolkit versus AMBER's ecosystem of specialized tools.

Performance Considerations and Output Management

In terms of computational efficiency, both packages are highly optimized for performance, though specific advantages emerge in different scenarios. GROMACS is renowned for its exceptional simulation speed through advanced GPU acceleration [35], while CPPTRAJ offers unparalleled flexibility in analyzing trajectories from various MD engines, including GROMACS itself [34].

Output management also differs substantially between the ecosystems. GROMACS primarily utilizes XVG files for numerical data and PDB files for structural outputs with B-factors, while CPPTRAJ generates plain text data files that can be easily parsed for custom plotting routines [29] [34] [33]. For researchers requiring highly customized analysis, CPPTRAJ's scripting capabilities provide finer control, whereas GROMACS offers greater simplicity for standard workflows.

Experimental Validation and Research Applications

Case Studies in Drug Discovery and Protein Engineering

Recent literature demonstrates the critical importance of RMSF validation in diverse research contexts, particularly in pharmaceutical development:

SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 Inhibition: In a 2025 study investigating potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 protein, RMSF analysis validated that lead compounds ZINC-089639800, ZINC-157610683, ZINC-075484852, ZINC-016611776, and ZINC-141457420 caused "no significant deviation from the NSP6-apo protein" in flexibility patterns, confirming compound binding without disruptive structural consequences [36].

Aptamer-Capsid Protein Interactions: Research on Macrobrachium rosenbergii nodavirus utilized 1000-ns simulations with RMSF analysis to reveal how truncated DNA aptamers induced "significant conformational changes and structural rearrangements in the capsid protein," demonstrating the antiviral potential of interfering with capsid self-assembly processes [37].

mTOR Inhibitor Screening: A 2025 virtual screening study for ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors employed RMSF alongside RMSD to quantitatively analyze structural stability, identifying three compounds (Top1, top2, and top6) that formed stable interactions with key residues including VAL-2240 and TRP-2239 [38].

Experimental Parameters and Protocol Specifications

These studies share common methodological frameworks for RMSF validation:

Table: Experimental Parameters from Recent RMSF Studies

| Study Focus | Simulation Length | Force Field | Key RMSF Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 [36] | 100 ns | Not specified | Selected compounds showed similar flexibility to apo protein |

| Viral Capsid Proteins [37] | 1000 ns | CHARMM36 | Aptamer binding induced structural rearrangements |

| mTOR Inhibitors [38] | Not specified | AMBER99SB-ILDN/GAFF | Stable binding with key residue interactions |

| Colorectal Cancer Biomarkers [39] | Not specified | Not specified | Identified valproic acid, cyclosporine, genistein as potential therapeutics |

The consistent application of RMSF across these diverse research areas highlights its role as a validation cornerstone in structural bioinformatics. The typical simulation length ranges from 100 ns for initial screening to 1000 ns for detailed mechanistic studies, with CHARMM36 and AMBER force fields being predominant choices [36] [37] [38].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful RMSF analysis requires both specialized software and carefully prepared input data. The following table catalogues essential components for conducting these experiments:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for RMSF Analysis

| Reagent/Software | Function in RMSF Analysis | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [29] [33] | MD simulation and trajectory analysis | gmx rmsf module with trajectory (.xtc) and topology (.tpr) inputs |

| AMBER/CPPTRAJ [34] [1] | Trajectory analysis and fluctuation calculation | atomicfluct command with topology (.prmtop) and trajectory (.nc) inputs |

| Molecular Visualization [33] | B-factor visualization and structural interpretation | PyMOL, VMD for coloring structures by B-factor values |