Solvation in Molecular Dynamics: From Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

This article explores the critical role of solvation modeling within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a cornerstone for advancing drug discovery and development.

Solvation in Molecular Dynamics: From Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

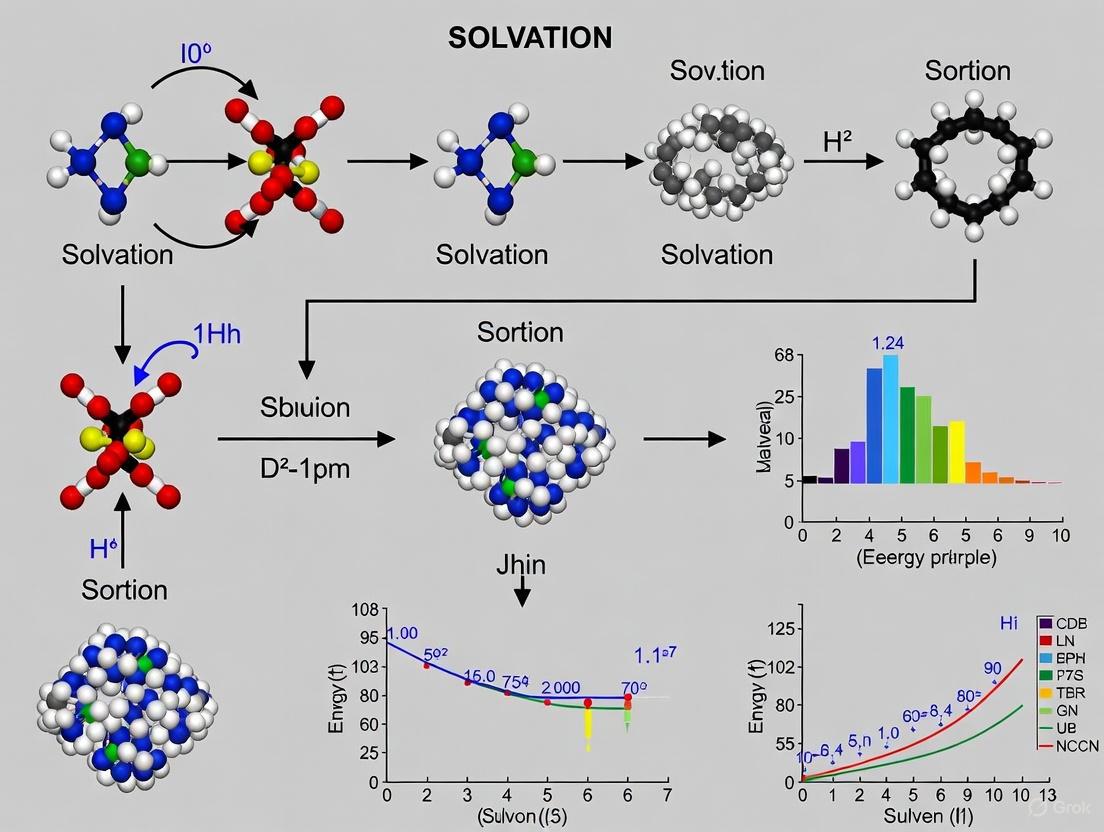

This article explores the critical role of solvation modeling within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a cornerstone for advancing drug discovery and development. It covers foundational principles, including key properties like Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) and solvation free energy that govern solute-solvent interactions. The piece details methodological advances, particularly the powerful integration of MD with machine learning (ML) to predict crucial properties such as drug solubility and electrolyte performance. It further addresses strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing simulations, such as using deep learning to bypass costly Poisson-Boltzmann calculations, and provides a framework for validating and comparing solvation models against experimental data. Aimed at researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, this resource synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends for leveraging solvation dynamics to accelerate rational drug design.

Understanding the Basics: How Solvation Dynamics Govern Molecular Behavior

Solvation describes the fundamental interaction between a solvent and a solute, representing the process by which solute and solvent molecules or ions rearrange to form solvated complexes [1]. At its core, solvation involves the dissolution of solutes in solvents, where individual solute molecules or ions become tightly enveloped by solvent molecules within a solution system [1]. This phenomenon possesses a strong theoretical research background in classical solution chemistry and electrolyte electrochemistry, making it a cornerstone of physical and chemical research over the past century [1]. In electrochemical systems, for instance, electrolytes contain ions that do not exist in isolation but form a solvated ionic atmosphere by interacting with solvent molecules [1]. The importance of solvation extends across multiple disciplines, including electrochemical energy storage, electrocatalysis, chemical synthesis, biochemistry, and drug formulation, where understanding solvation mechanisms is critical for optimizing processes and developing new technologies [1] [2].

From a thermodynamic perspective, solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) gives the free energy change associated with the transfer of a molecule between ideal gas and solvent at a specific temperature and pressure [3]. This fundamental thermodynamic quantity represents the difference in the free energy of the solute in vacuum and in the solvent phase, providing crucial insights into how solvent behaves in different molecular environments [3] [4]. Accurately predicting solvation free energy is essential for multiple research fields, as it relates to a broad range of physical properties including infinite dilution activity coefficients, Henry's law constants, solubilities, and the distribution of chemical species between immiscible solvents or different phases [3].

Theoretical Foundations and Quantitative Descriptors

Thermodynamic Framework

The quantitative understanding of solvation begins with its thermodynamic definition. Solvation free energies are differences in thermodynamic potentials that describe the relative populations of a chemical species in solution and gas phase at equilibrium [3]. In the thermodynamic limit in the solvated phase and the ideal gas limit in the gas phase, the solvation free energy ΔGsolv of component i is equal to μi,solv − μi,gas, the difference in chemical potentials in the two phases [3]. In the additional limit of one molecule of component i at infinite dilution, these become the infinite dilution excess chemical potentials in the respective solvents.

The Gibbs energy of solvation serves as the direct bridge between molecular calculations and real-world observables like solubilities, partition ratios, and equilibrium constants, which dictate concentrations, yields, and distribution of compounds under realistic conditions [5]. For any experimental equilibrium, the equation:

ΔG = -RTlnK

states the relationship between the equilibrium constant K and the difference in Gibbs energy ΔG for the respective process at temperature T, with R being the ideal gas constant [5]. This fundamental relationship enables researchers to connect microscopic solvation phenomena with macroscopic observable properties.

Key Quantitative Descriptors

Table 1: Key Quantitative Descriptors in Solvation Science

| Descriptor | Symbol | Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvation Free Energy | ΔGsolv | Free energy change for transferring a solute from ideal gas to solvent | Fundamental measure of solute-solvent affinity; predicts solubility & partitioning |

| Hydration Free Energy | ΔGhyd | Special case of ΔGsolv for water as solvent | Particularly valuable in biochemistry & drug design for aqueous environments |

| Partition Ratio | logKα/β | Equilibrium constant for solute partitioning between two immiscible phases | Predicts distribution of compounds in multiphase systems |

| Transfer Free Energy | ΔtrG | ΔGsolv,B - ΔGsolv,A for transfer between solvents A and B | Quantifies relative solvation in different media |

| Henry's Law Constant | HLC | Partitioning between solution phase and gas phase | Environmental fate modeling & gas absorption processes |

Partition ratios describe the equilibrium of a substance between two immiscible solution phases, while Henry's Law constants denote the partitioning of a substance between a solution phase and the gas phase [5]. Both can be used to obtain the respective Gibbs energy difference, providing crucial information about how compounds distribute themselves in complex systems [5].

Computational Methodologies for Solvation Analysis

Explicit Solvation Models

Explicit solvation approaches include solvent molecules directly in the calculation, providing the most detailed representation of solute-solvent interactions [5]. These methods commonly use free-energy perturbation or thermodynamic integration with dynamic simulations, requiring exhaustive sampling of the configurational space [5]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have evolved as a powerful tool to describe the complex behavior of components in deep eutectic solvents and other complex solvent systems [2]. In a recent study on the solvation of heteroaromatic drugs in reline (a deep eutectic solvent), MD simulations revealed how drug molecules undergo self-association through π-stacking and other intermolecular interactions, with aggregates that are transient and limited in size rather than persistent or large [2]. These simulations typically employ periodic boundary conditions with a short-range cut-off (e.g., 1.2 nm) and utilize the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) procedure to model electrostatic interactions of atom pairs further apart than 1.5 nm [2].

Implicit Solvation and Alchemical Approaches

Implicit solvation models approximate the solvent as a continuum, drastically improving computational cost and enhancing applicability [5]. Most implicit solvation models are based on a quantum-mechanical treatment of the solute, while the continuum is often treated classically [5]. Popular approaches include polarizable continuum models based on solving the Poisson equation around a molecular cavity, sometimes with additional terms to describe specific solvent-solute interactions like hydrogen bonding, dispersion interactions, and cavitation energy [5].

Alchemical free energy methods simulate a series of non-physical intermediates to compute the free energy of transferring a solute from solution to gas phase or vice versa [3]. This alchemical path provides an efficient way to move the solute between phases by perturbing its interactions in a non-physical way, and since free energy is path-independent, this non-physical process still yields the correct free energy change for transfer of the solute from solvent to gas [3]. A particularly efficient set of intermediate states uses a two-step process, first turning off the van der Waals interactions using one parameter λv, and another turning off the electrostatic interactions using a second parameter λe [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Approaches for Solvation Free Energy

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Best Use Cases | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent MD | Very High | High (0.4 kJ·mol-1 or better) | Small molecules, detailed interaction analysis | Computationally demanding; requires extensive sampling |

| Alchemical Free Energy | High | High (when properly converged) | Drug-like molecules, SAMPL challenges | Careful pathway design needed; possible end-state problems |

| Implicit Solvent (PCM) | Moderate | Variable (system-dependent) | Initial screening, QM studies of solvation | Misses specific solute-solvent interactions |

| Machine Learning | Low (after training) | Good (R² ~0.87 demonstrated) | High-throughput screening, drug development | Limited by training data quality and diversity |

| QSPR/Descriptor-Based | Very Low | Moderate for similar compounds | Early-stage property estimation | Limited transferability across chemical classes |

Machine Learning and Emerging Approaches

Recent advances have integrated machine learning with molecular dynamics to predict solvation-related properties. One study statistically examined the impact of ten MD-derived properties, along with the octanol-water partition coefficient (logP), on the aqueous solubility of drugs using machine learning techniques [6]. Through rigorous analysis, seven properties were identified as having the most significant influence on solubility: logP, Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic interactions, Lennard-Jones interactions, Estimated Solvation Free Energies, Root Mean Square Deviation, and the Average number of solvents in the Solvation Shell [6]. The Gradient Boosting algorithm achieved the best performance with a predictive R² of 0.87 and an RMSE of 0.537 in the test set, demonstrating the potential of integrating MD simulations with ML methodologies to improve the accuracy and efficiency of aqueous solubility predictions in drug development [6].

Experimental Characterization and Benchmarking

Spectroscopic and Analytical Techniques

The characterization and prediction of solvation structure is an important part of the research field of ionic solvation [1]. Current popular characterization methods include Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and NMR spectroscopy [1]. These techniques provide indirect information about solvation structures and dynamics by probing the chemical environment around solute molecules.

Recent breakthroughs in the visual observation of solvation have established new milestones in the field [1]. In November 2023, H. Stapelfeldt and co-workers were the first to instrumentally demonstrate the ion solvation process, capturing the dynamic solvation of sodium ions in helium droplets using femtosecond optics for the first time [1]. This breakthrough, achieved through the integration of theoretical principles, experimental results, and precise simulations, has significantly advanced the field of solvation science by providing direct observational data of this fundamental process.

Benchmark Sets and Validation

The development of reliable computational models requires robust benchmarking against experimental data. The FlexiSol benchmark set represents a significant advancement, combining structurally and functionally complex, highly flexible solutes with exhaustive conformational sampling for systematic testing of solvation models [5]. This dataset contains 824 experimental solvation energy and partition ratio data points with over 25000 theoretical conformer/tautomer geometries across all phases, focusing on drug-like, medium-to-large flexible molecules [5]. Such comprehensive datasets are crucial for validating computational approaches and identifying their limitations.

Evaluation using this benchmark has revealed that partition ratios are generally computed more accurately compared to solvation energies, likely due to partial error cancellation, yet most models still systematically underestimate strongly stabilizing interactions while overestimating weaker ones in both solvation energies and partition ratios [5]. Additionally, research has shown that full Boltzmann-weighted ensembles or just the lowest-energy conformers yield very similar accuracy – but both require conformational sampling – whereas random single-conformer selection degrades performance, especially for larger and flexible systems [5].

Practical Protocols for Solvation Free Energy Calculation

Alchemical Free Energy Protocol

The following protocol outlines the steps for calculating solvation free energy using alchemical methods with GROMACS and PMX, as demonstrated for an aniline molecule [4]:

System Preparation:

- Force Field Parameterization: Generate force field parameters for the solute molecule. For aniline, GAFF2 parameters can be obtained using AmberTools.

- Topology Preparation: Create topology files defining the molecular structure and interaction parameters.

- Simulation Box Setup: Use GROMACS editconf to create a simulation box (e.g., dodecahedron with 1.5 nm distance) and solvate with water model (e.g., TIP3P).

End-State Simulations:

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization for both end states (λ=0 and λ=1) using the steepest descent algorithm to remove steric clashes.

- NVT Equilibration: Conduct 10 ps of NVT equilibration using the velocity-rescale thermostat to stabilize temperature.

- NPT Production: Run 6 ns of NPT simulation, discarding the first 1 ns as equilibration and using the remaining 5 ns for analysis.

Non-Equilibrium Transitions:

- Frame Extraction: Extract 100 frames from the production trajectory, dumping every 50 ps.

- Short Transitions: Perform 100 short non-equilibrium transitions (200 ps each) between end states.

- Free Energy Calculation: Use the Jarzynski equality or Bennett Acceptance Ratio to compute the free energy difference from work values.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Computational Solvation Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Molecular simulation engines | Explicit solvent simulations; free energy calculations |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian, ORCA | Electronic structure calculations | Implicit solvation; parameter derivation |

| Solvation Databases | FreeSolv, MNSOL, FlexiSol | Experimental reference data | Method validation; benchmarking |

| Force Fields | GAFF, OPLS, CHARMM | Molecular interaction parameters | MD simulations; consistent energy evaluation |

| Analysis Tools | PMX, VMD, MDAnalysis | Trajectory analysis; visualization | Solvation structure analysis; free energy estimation |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Reline (ChCl:Urea 1:2) | Green solvent for drug solubilization | Pharmaceutical applications; sustainable chemistry |

Applications in Drug Development and Materials Science

Pharmaceutical Applications

Solvation plays a decisive role in pharmaceutical development, particularly in addressing challenges of drug solubility and bioavailability. The Biopharmaceutical Classification System sorts drugs along their solubility and permeability, and for drug development both aspects must be considered [2]. The use of co-solvents to increase the solubility of drugs with inherently low water solubility has been previously employed including ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents [2]. Various uses of deep eutectic solvents for therapeutic applications have been reported in the last two decades, including the solubilization of heteroaromatic drugs such as the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs celecoxib or piroxicam by the use of choline-based deep eutectic solvents [2].

Molecular-level understanding of drug-solvent interactions enables rational design of optimized drug delivery systems. In a study on the solvation of heteroaromatic drugs in reline, combined MD simulation and DFT analysis revealed the formation of drug aggregates through π-stacking with energies ranging from -10 kcal mol-1 for allopurinol to -32 kcal mol-1 for losartan, showing interplanar distances ranging from 0.36 to 0.47 nm [2]. These observations provide crucial insights for designing optimized deep eutectic solvents for drug delivery by understanding the balance between solvation and self-aggregation [2].

Electrochemical Systems

In electrochemical systems, solvation effects cannot be ignored, whether in electrocatalysis, supercapacitors, or secondary metal batteries [1]. Ion solvation is one of the decisive factors for exploring electrochemical mechanisms and optimizing electrochemical performances [1]. Specifically, in lithium-based rechargeable batteries, understanding and controlling electrolyte solvation structure is crucial for improving battery efficiency, lifespan, and safety [1]. Recent advances in high-concentration electrolytes ("water-in-salt" electrolytes) have spurred chemists to explore the mechanisms and impacts of solvation chemistry in electrochemical electrolytes [1].

Solvation effects significantly influence electrocatalytic processes, including the oxygen reduction reaction, which is fundamental to fuel cell technology. Theoretical studies have revealed that solvent effects can distinctly modify intermolecular interactions of water and influence the adsorption behavior of reaction intermediates on catalyst surfaces [1]. Understanding these solvation effects enables the design of more efficient electrocatalysts by tuning interfacial hydrogen bonds and optimizing the electrochemical interface structure [1].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, solvation science continues to face important challenges. Accurate understanding of the structure-activity relationship and mechanism of action between solvation and its applications remains an important challenge [1]. The process occurs on very small scales and involves rapid time scales, with interactions typically taking place within picoseconds to femtoseconds, making direct observation extremely challenging [1]. While recent breakthroughs in visual observation have established new milestones, further methodological developments are needed to fully resolve solvation dynamics across diverse systems.

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating multiple computational approaches with advanced experimental characterization. The combination of conventional experimental characterization with theoretical simulations, along with recent developments in advanced femtosecond time-resolved coulomb explosion imaging and time-of-flight mass spectrometer technology, is expected to advance the pace of theoretical exploration and practical application of solvation [1]. Additionally, the development of more comprehensive benchmark sets that include flexible molecules and conformer ensembles will enable more systematic development and evaluation of solvation models [5].

Machine learning approaches will continue to enhance our ability to predict solvation properties, with recent research demonstrating that MD-derived properties combined with traditional descriptors can achieve high predictive accuracy for drug solubility [6]. As these models become more sophisticated and are trained on more diverse datasets, they will increasingly support drug development and materials design by providing accurate predictions of solvation-related properties before synthetic efforts are undertaken.

The ongoing development of therapeutic deep eutectic solvents and volatile deep eutectic solvents as novel approaches for enhancing the solubility of active pharmaceutical ingredients and controlling crystal growth represents another promising direction [2]. These systems leverage our growing understanding of solvation mechanisms to design improved drug formulations with enhanced bioavailability and stability profiles.

Solvation, the interaction between a solute and surrounding solvent molecules, is a fundamental driving force in numerous biological processes, including biomolecular recognition, self-assembly, and protein folding and function [7]. Within the framework of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, solvation can be studied with atomistic detail, providing invaluable insights into the physicochemical properties that govern molecular behavior in solution. MD simulations provide a powerful computational tool for modeling various properties by offering a detailed perspective on molecular interactions and dynamics [8]. This technical guide focuses on four key properties derived from MD simulations that are critical for understanding and predicting solvation phenomena: the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Lennard-Jones (LJ) interaction energy, Coulombic interaction energy, and Solvation Shell analysis. The accurate characterization of these properties is particularly crucial in fields like drug discovery, where they are used to predict essential parameters such as aqueous solubility, which significantly influences a medication's bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy [8].

Theoretical Foundations of Key Properties

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

SASA is a geometric descriptor that quantifies the surface area of a solute molecule that is accessible to a solvent probe. It provides a simple yet powerful way to estimate the hydrophobic contribution to solvation, as larger SASA values often correlate with greater disruption of the solvent network. In continuum solvation models, the hydrophobic effect is frequently accounted for by a term that is linearly proportional to the SASA [7]. Beyond hydrophobicity, SASA is often subdivided into hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and aromatic components to provide a more nuanced picture of the solute-solvent interface [8].

Lennard-Jones and Coulombic Interaction Energies

The non-bonded interactions between a solute and its solvent environment are primarily described by the Lennard-Jones (LJ) and Coulombic potentials.

- Lennard-Jones (LJ) Energy: This term represents the van der Waals interactions, encompassing both short-range repulsion (Pauli exclusion) and longer-range attraction (London dispersion forces). In MD force fields, it is typically modeled by a 12-6 Lennard-Jones potential [7]. The LJ interaction between a solute and the solvent is a key component of the solvation free energy functional in methods like the Variational Implicit Solvent Method (VISM) [7].

- Coulombic Energy: This term describes the electrostatic interaction between the partial atomic charges of the solute and the solvent. It is a fundamental component for modeling polar and charged species in solution. The accurate calculation of electrostatic contributions is a central challenge in solvation models, often addressed using methods ranging from the Poisson-Boltzmann equation to simpler approximations like the Coulomb Field Approximation [7].

Solvation Shell Analysis

The solvation shell is the first few layers of solvent molecules surrounding a solute. Its structure and dynamics are critical for understanding specific solute-solvent interactions. Key metrics for analyzing the solvation shell include:

- Average Number of Solvents in the Solvation Shell (AvgShell): A count of solvent molecules within a defined cutoff distance from the solute, providing a measure of solvation coordination [8].

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): A statistical measure that describes the probability of finding a solvent particle at a specific distance from a reference point in the solute, thereby elucidating the local solvent structure [9]. When combined with angular distributions, it can reveal complex interaction geometries, such as those in π-stacking [2].

Quantitative Data from MD Studies

The following tables summarize the quantitative findings and performance metrics of these properties from recent MD investigations.

Table 1: Influence of key MD-derived properties on aqueous solubility prediction in a machine learning model [8].

| Property | Description | Role in Solubility (logS) Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| logP | Octanol-water partition coefficient | One of the most influential experimental properties; included for comparison |

| SASA | Solvent Accessible Surface Area | Identified as a highly effective predictor |

| LJ | Lennard-Jones interaction energy | Identified as a highly effective predictor |

| Coulombic_t | Coulombic interaction energy over time | Identified as a highly effective predictor |

| DGSolv | Estimated Solvation Free Energy | Identified as a highly effective predictor |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation | Identified as a highly effective predictor |

| AvgShell | Average number of solvents in solvation shell | Identified as a highly effective predictor |

Table 2: Aggregation properties of heteroaromatic drugs in Reline (a deep eutectic solvent) from a combined MD and DFT study [2].

| Drug Molecule | Average Aggregation Number | π-Stacking Interaction Energy (DFT) | Interplanar Distance (DFT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allopurinol | ~2.6 molecules | -10 kcal mol⁻¹ | 0.36 nm |

| Omeprazole | ~4.3 molecules | Not Specified | 0.47 nm |

| Losartan | ~5.5 molecules | -32 kcal mol⁻¹ | Not Specified |

Table 3: Performance of ensemble machine learning algorithms using key MD-derived properties for solubility prediction [8].

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Predictive R² (Test Set) | RMSE (Test Set) |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | 0.87 | 0.537 |

| XGBoost | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Random Forest | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Extra Trees | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Workflow for MD Simulation and Property Calculation

The process of extracting the key properties from an MD simulation follows a standardized workflow, from system setup to trajectory analysis.

Detailed Methodology for an Aqueous Solubility Study

The following protocol is adapted from a study that used MD properties to predict the aqueous solubility of 211 drugs with machine learning [8].

System Setup for MD Simulation:

- Software: GROMACS.

- Ensemble: Simulations are conducted in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble.

- Force Field: A specific force field (e.g., GROMOS96 53A6) is selected for its reliability in capturing hydrogen bonding and solvation behavior [2].

- Electrostatics: The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) procedure is utilized for long-range electrostatic interactions [2].

- Thermostat/Coupler: A velocity-rescaling thermostat is used for temperature coupling [2].

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- Energy Minimization: Perform an initial energy minimization to eliminate steric clashes and close contacts in the structure [2] [4].

- NVT Equilibration: Execute an equilibration run in the canonical (NVT) ensemble for a sufficient duration (e.g., >5 ns) to stabilize the system temperature [2].

- NPT Equilibration: Conduct a subsequent equilibration in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble (e.g., for 5 ns) to stabilize the system density and pressure [2].

Production MD Run:

Property Extraction from Trajectory:

- SASA: Calculate using a tool like

gmx sasain GROMACS, which rolls a solvent probe over the van der Waals surface of the solute. - LJ and Coulombic Energies: These non-bonded interaction energies between the solute and solvent can be computed using the

gmx energyutility or through analysis modules that process the trajectory. - Solvation Shell (AvgShell): Calculate the average number of solvent molecules within a specified cutoff distance (e.g., the first minimum of the solute-solvent RDF) for each frame, then average over the entire production trajectory.

- SASA: Calculate using a tool like

Data Integration for Machine Learning:

- Compile the extracted MD-derived properties (SASA, LJ, Coulombic_t, DGSolv, RMSD, AvgShell) along with the experimental logP value for each compound in the dataset.

- Use these features as input for ensemble machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting) to build a predictive model for logarithmic solubility (logS).

Protocol for Solvation Free Energy Calculation using Alchemical Methods

The solvation free energy (DGSolv) is a critical integrative property. It can be calculated precisely using non-equilibrium alchemical free energy methods [4].

End-State Definition:

- State A (λ=0): The fully solvated solute, with all interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic) enabled.

- State B (λ=1): The solute in vacuum, achieved by turning off all its non-bonded interactions with the solvent.

Simulation Steps:

- Prepare the topology file for the solute, defining the

couple-moltypeand settingcouple-lambda0tovdw-qandcouple-lambda1tonone[4]. - For each end state, perform independent system preparation (simulation box generation, solvation), energy minimization, and equilibration (NVT and NPT) [4].

- Run an NPT production simulation for each state. Extract multiple frames from the equilibrated trajectory of each state.

- Prepare the topology file for the solute, defining the

Non-Equilibrium Transitions:

- Use the extracted frames to initiate many short (e.g., 200 ps) non-equilibrium simulations. These transitions are controlled by a

delta-lambdaparameter, which defines the rate at which the Hamiltonian is switched from one state to the other [4]. - Perform transitions in both directions (from λ=0 to λ=1, and from λ=1 to λ=0).

- Use the extracted frames to initiate many short (e.g., 200 ps) non-equilibrium simulations. These transitions are controlled by a

Free Energy Analysis:

- The work values from the non-equilibrium transitions are analyzed, typically using methods like Jarzynski's equality, to obtain the final solvation free energy estimate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential software, force fields, and solvents used in MD solvation studies.

| Category | Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software | Simulation Suites | GROMACS [8] [2] [4], CHARMM | Engine for running MD simulations; integrates force fields, solvation models, and analysis tools. |

| Force Fields | Biomolecular FF | GROMOS96 53A6 [2], CHARMM36 [7] | Defines potential energy functions and parameters (masses, charges, LJ parameters) for molecules. |

| Solvent Models | Explicit Water | TIP3P [4] [7] | Explicitly models water molecules for realistic solvation dynamics and interaction sampling. |

| Solvent Models | Deep Eutectic Solvents | Reline (Choline Chloride/Urea) [2] | A green solvent alternative for studying solubilization of poorly water-soluble drugs. |

| Continuum Solvents | Implicit Solvent | 3D-RISM [10], VISM [7], PBSA [11] | Represents solvent as a continuous medium, drastically reducing computational cost for free energy calculations. |

| Analysis Tools | Trajectory Analysis | GROMACS built-in tools (gmx sasa, gmx energy), PMX [4] |

Extracts quantitative properties (SASA, energies, RDFs) from MD trajectory files. |

| Analysis Tools | Visualization | AMSview [10] | Visualizes complex results, such as 3D solvent distribution functions from RISM calculations. |

The integration of Molecular Dynamics simulations to compute properties like SASA, Lennard-Jones energy, Coulombic energy, and solvation shell metrics provides a powerful, atomistic lens through which to view solvation. As demonstrated, these properties are not merely descriptors; they are highly effective predictors of critical outcomes like aqueous solubility when fed into modern machine learning models [8]. Furthermore, advanced solvation theories like VISM and 3D-RISM offer robust frameworks for connecting these molecular interactions to thermodynamic quantities such as solvation free energy [10] [7]. The continued refinement of force fields, sampling algorithms, and multi-scale approaches ensures that MD-derived properties will remain indispensable for advancing molecular research in drug development, materials science, and beyond.

Solvation, the molecular process where solvent molecules surround and interact with solute molecules or ions, forms the critical foundation for understanding drug solubility and bioavailability [1]. In electrochemical and pharmaceutical systems, drug ions do not exist in isolation; rather, they form a solvated ionic atmosphere through specific interactions with solvent molecules [1]. This solvation process involves the rearrangement of solute and solvent molecules to form stabilized complexes where individual solute units become enveloped by multiple solvent molecules, thereby fundamentally modifying the chemical environment surrounding the drug molecule [1]. The importance of solvation science has recently been amplified by groundbreaking experimental advances, including the first instrumental demonstration of the ion solvation process using femtosecond optics to capture the dynamic solvation of ions, establishing new milestones for the field [1].

For pharmaceutical researchers and development professionals, understanding solvation is not merely academic—it represents a pivotal factor in overcoming the most persistent challenge in modern drug development: poor aqueous solubility. With approximately 40% of past developed drugs and 70-90% of current drug candidates exhibiting poor water solubility, the pharmaceutical industry faces formidable barriers in formulating effective therapeutics [12]. The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) categorizes drug compounds into four classes based on solubility and permeability characteristics, with Class II (high permeability, low solubility) and Class IV (low permeability, low solubility) compounds presenting the most significant development challenges [13]. For these problematic compounds, solvation effects directly influence dissolution rates, absorption potential, and ultimately, therapeutic efficacy, making the thorough understanding of solvation processes an indispensable component of modern drug development pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations of Solvation Chemistry

Molecular Mechanisms of Solvation

At the molecular level, solvation encompasses complex interactions between drug molecules and their solvent environments. The process is governed by the principle that solute-solvent interactions must overcome the crystal lattice energy of the solid drug and the cohesive energy of the solvent to achieve dissolution [14]. When a drug molecule enters a solution, its chemical groups induce reorganization of surrounding solvent molecules to form solvation shells—structured layers of solvent molecules that interact with specific regions of the drug molecule through various intermolecular forces [1]. These interactions include hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions, van der Waals forces, and ion-dipole interactions for charged molecules, collectively determining the thermodynamic stability of the solvated complex [1].

The strength and characteristics of these interactions are quantified by the solvation free energy (ΔG°solv), a fundamental thermodynamic property directly related to solubility [15]. This property represents the free energy change associated with transferring a solute from an ideal gas phase to solution, effectively measuring the stability of the solvated drug molecule [16]. Computational studies have demonstrated that accurate prediction of solvation free energy can be achieved using continuum solvation models like uESE with single molecular mechanics-generated conformations, providing researchers with efficient tools for solubility screening [15]. The ability to predict this parameter is particularly valuable in early drug development stages, where resource constraints necessitate prioritization of compounds with favorable solubility profiles.

Computational Approaches to Modeling Solvation

Modern computational chemistry provides powerful methods for investigating solvation phenomena at the atomic level. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as particularly valuable tools for modeling the dynamic behavior of drug molecules in solution, offering insights into solvation structures and dynamics that are challenging to observe experimentally [17]. These simulations track the temporal evolution of drug-solvent systems, revealing critical molecular properties that influence solubility, including solvent accessible surface area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies, and characteristics of the solvation shell [17].

Advanced computational strategies combine multiple theoretical approaches to overcome the limitations of individual methods. Recent innovations include integrating graph neural networks (GNNs) with first-principles calculations through semi-supervised distillation frameworks to predict solubility in multicomponent solvent systems [16]. These models successfully unify experimental data with computationally derived COSMO-RS data, significantly expanding the accessible chemical space and improving prediction accuracy for complex pharmaceutical systems [16]. For solvent-sensitive compounds, studies have demonstrated that explicit solvent modeling provides superior accuracy compared to implicit solvation models, particularly for predicting photophysical behavior and excited-state dynamics relevant to photodegradation pathways [18].

Table 1: Key Molecular Dynamics Properties Influencing Drug Solubility

| Property | Description | Influence on Solubility |

|---|---|---|

| Solvation Free Energy (DGSolv) | Free energy change for transferring solute from gas to solution | Direct thermodynamic determinant of solubility; more negative values favor dissolution |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | Surface area accessible to solvent molecules | Larger SASA generally increases solvent interactions and solubility |

| Coulombic Interaction Energy | Electrostatic interactions between solute and solvent | Stronger interactions with polar solvents (e.g., water) enhance solubility of ionic species |

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Van der Waals attraction and Pauli repulsion | Governs non-polar interactions; important for hydrophobic drug partitioning |

| Solvation Shell Characteristics | Number and arrangement of solvent molecules around solute | Dense, well-ordered solvation shells stabilize dissolved drugs |

Experimental Methodologies for Solvation and Solubility Analysis

Spectroscopic and Analytical Techniques

Experimental characterization of solvation structures employs sophisticated spectroscopic methods that probe different aspects of solute-solvent interactions. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and Raman spectroscopy provide information about vibrational modes that shift in response to solvent environment, revealing specific molecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding and dipole reorientation [1]. These techniques can identify solvation-induced changes in functional group vibrations, such as shifts in carbonyl stretching frequencies or modifications in hydrogen bonding patterns around ionizable groups [19].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly pulsed-field gradient methods, offers insights into molecular diffusion and rotational correlation times that reflect solvation dynamics [1]. Time-resolved terahertz-Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful technique for capturing the rapid dynamics of solvent reorganization around drug molecules, with studies demonstrating that cations and anions distinctly modify intermolecular interactions of water [1]. For solid-state characterization, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) are indispensable for identifying polymorphic forms and monitoring phase transformations that may occur during solvation or processing [14].

Solubility Measurement Protocols

Accurate determination of solubility remains fundamental to pharmaceutical development, with two primary conceptual frameworks guiding measurement approaches:

Thermodynamic Solubility: Measured using the shake-flask method where an excess of drug is equilibrated in solvent with agitation until saturation is achieved, followed by phase separation through centrifugation or filtration and quantification of dissolved solute [17]. This method establishes the equilibrium concentration where dissolution and crystallization rates are balanced.

Kinetic Solubility: Determined through methods such as HPLC-UV, nephelometry, or turbidimetry that identify the concentration at which precipitation begins from a supersaturated solution [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for early screening when compound amounts are limited.

For conversion between experimental measurements, molar solubility (logS) can be related to solvation free energy (ΔG°solv) using the equation:

[ \Delta G°{solv} = -RT \ln \left( \frac{S}{M°} \right) + RT \ln \left( \frac{P{vap}}{P°} \right) ]

where R is the gas constant, T is temperature, S is the molar solubility, M° is the standard state molarity (1 mol L⁻¹), Pvap is the vapor pressure of the solute, and P° is the pressure of an ideal gas at 1 mol L⁻¹ and 298 K (24.45 atm) [16]. This thermodynamic relationship allows researchers to connect experimental solubility measurements with computational predictions of solvation energetics.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Solvation and Solubility Characterization

| Technique | Application | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Molecular interaction analysis | Hydrogen bonding, functional group solvation, molecular complexation |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Solid form and solution analysis | Polymorph identification, solute-solvent interactions |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Molecular dynamics and structure | Solvation shell composition, molecular mobility, drug conformation |

| Powder XRD | Solid-state characterization | Crystal structure, polymorph identity, phase transformations |

| DSC/TGA | Thermal behavior analysis | Melting point, glass transitions, hydrate/ solvate formation |

| Shake-Flask Method | Thermodynamic solubility | Equilibrium solubility, pH-solubility profile |

Solvation-Driven Formulation Strategies for Bioavailability Enhancement

Solid State Manipulation Approaches

Pharmaceutical scientists employ various solid-state manipulation strategies to optimize drug solvation and enhance dissolution rates. These approaches target the fundamental energy barriers to dissolution by modifying the physical form of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API):

Salt Formation: Ionizable drugs can be converted to salt forms that typically exhibit higher aqueous solubility through improved solvation of the ionic species [14]. Salt selection must consider toxicological implications of counterions and physical stability, as salt dissociation in the dosage form can lead to reversion to less soluble forms [14].

Polymorph Selection: Different crystal forms of the same API can display significantly different solubility and dissolution characteristics, with metastable polymorphs often providing enhanced solubility at the cost of thermodynamic stability [14]. The case of ritonavir exemplifies the "polymorph problem," where late-appearance of a more stable polymorph compromised original product performance, necessitating product withdrawal and reformulation [14].

Amorphous Solid Dispersions: Non-crystalline APIs prepared through methods like hot melt extrusion or spray drying can provide substantial solubility enhancement but require stabilization using polymers to prevent crystallization and maintain performance advantages [14] [20]. The glass transition temperature (Tg) serves as a critical parameter for predicting physical stability, with higher Tg values generally indicating greater stability against crystallization [14].

Particle Size Reduction: Technologies such as nano-milling increase specific surface area, leading to enhanced dissolution rates through more extensive solute-solvent contact [12] [14]. This approach is particularly effective for BCS Class II compounds where dissolution rate limits absorption.

Advanced Nanotechnologies and Delivery Systems

Novel nano-technologies represent the cutting edge of solubility enhancement, employing engineered systems to optimize drug solvation and bioavailability. Nano-suspensions stabilize sub-micron drug particles using stabilizers to prevent aggregation and Ostwald ripening, creating high-surface-area systems with enhanced dissolution velocity [12]. Co-crystal engineering designs new crystalline entities through hydrogen bonding between API and co-formers, creating structures with optimized solvation characteristics while maintaining adequate stability [14]. These systematically designed materials have generated considerable interest for their potential to improve API solubility while maintaining acceptable solid-state stability.

The implementation of Quality-by-Design (QbD) principles provides a structured framework for formulation development, ensuring that solvation-related quality attributes are built into the product from conception [20]. This science-based, data-driven approach helps developers identify key parameters influencing solubility and bioavailability, mitigating cost and time implications of late-stage development setbacks through systematic understanding of formulation and process variables [20].

Computational Prediction and Machine Learning in Solvation Science

Molecular Dynamics and Property Prediction

Molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable tools for predicting solvation-related properties early in drug development. Research has demonstrated that specific MD-derived properties show exceptional correlation with experimental solubility measurements, enabling virtual screening of candidate compounds before synthesis [17]. Analysis of 211 drugs from diverse classes identified seven key properties that effectively predict aqueous solubility: logP, solvent accessible surface area (SASA), Coulombic interaction energy, Lennard-Jones potential, estimated solvation free energy (DGSolv), root mean square deviation (RMSD), and average number of solvents in the solvation shell (AvgShell) [17].

Machine learning algorithms successfully leverage these properties to build predictive models with performance comparable to structure-based approaches. In comprehensive evaluations, Gradient Boosting algorithms achieved superior performance with a predictive R² of 0.87 and RMSE of 0.537 on test sets, demonstrating the power of MD-derived properties as predictive features [17]. These models enable researchers to prioritize compounds with optimal solubility profiles during early discovery phases, potentially reducing late-stage attrition due to poor biopharmaceutical properties.

Emerging AI and Graph Neural Network Applications

The integration of artificial intelligence with solvation science represents the frontier of computational pharmaceutics. Graph neural networks (GNNs) have shown remarkable capability in modeling solubility in multicomponent solvent systems, addressing the complex interactions between solutes and multiple solvent components [16]. Advanced architectures including "concatenation" and "subgraph" approaches effectively capture the relationship between molecular structure and solvation free energy, with semi-supervised distillation frameworks significantly expanding chemical space coverage and correcting previously high error margins [16].

These computational approaches are particularly valuable for predicting behavior in complex solvent systems, such as the hexane-ethyl acetate-methanol-water (HEMWat) system used to separate lignin-derived monomers, or optimized cosolvent mixtures that enhance solubility of water-insoluble drugs [16]. By unifying experimental and computational data in robust, flexible GNN-SSD pipelines, researchers can achieve greater coverage, improved accuracy, and enhanced applicability of solubility models for pharmaceutical development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Solvation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Solvation Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| COSMO-RS Solvation Model | Predicts solvation free energies and activity coefficients | Screening solvent systems for optimal drug solubility [16] |

| Classical Force Fields (CFF) | Models intermolecular interactions in MD simulations | Studying drug-polymer interactions in amorphous dispersions [18] |

| B3LYP/cc-pVDZ Basis Set | Quantum chemical calculation of molecular properties | Determining solvatochromic effects on electronic transitions [19] |

| GROMACS Software | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Calculating MD-derived properties for solubility prediction [17] |

| Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide (HPAM) | Polymer for studying adsorption behavior | Modeling drug-polymer interactions in solid dispersions [18] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous materials for selective adsorption | Studying molecular encapsulation and release mechanisms [18] |

Solvation science represents far more than an academic curiosity—it forms the fundamental bridge between drug molecular structure and biological performance. As research continues to unravel the complex relationships between solvation structures, solubility, and bioavailability, new opportunities emerge for rational design of enhanced pharmaceutical products. The integration of advanced computational methods with high-resolution experimental techniques promises to accelerate this understanding, enabling predictive approaches to formulation design rather than empirical optimization.

Future advancements will likely focus on multiscale modeling approaches that connect quantum mechanical insights with macroscopic product performance, and the development of more sophisticated AI tools that can navigate the complex chemical space of drug formulations. Additionally, the growing emphasis on sustainable chemistry in pharmaceutical manufacturing will drive interest in solvent systems that balance solvation efficiency with environmental considerations. Through continued interdisciplinary research that links molecular-level solvation phenomena to clinical performance, scientists can overcome the persistent challenge of poor solubility and deliver more effective therapeutics to patients.

The radial distribution function (RDF) serves as a fundamental statistical mechanics concept that characterizes the spatial arrangement of particles in a system, describing the probability of finding a particle at a specific distance from a reference particle [21]. This technical guide explores the crucial role of RDFs in quantifying molecular interactions within hydrogen-bonded networks, with particular emphasis on solvation effects in molecular dynamics research. By bridging microscopic interactions with macroscopic thermodynamic properties, RDF analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with powerful insights into molecular recognition processes, protein folding, and solvent effects that dominate biological systems [21] [22]. This whitepaper presents comprehensive methodologies for obtaining and interpreting RDF data, with specific applications to hydrogen-bonded binary mixtures relevant to pharmaceutical research.

Theoretical Foundations of Radial Distribution Functions

Mathematical Formulation and Physical Interpretation

The radial distribution function, denoted as g(r), is formally defined as a function that describes the probability of finding a particle at a distance r from a reference particle in a homogeneous and isotropic system relative to what would be expected for a completely random distribution [21]. The mathematical methodology for calculating g(r) involves selecting a reference atom within the system and constructing concentric spherical shells of thickness dr around it. Through systematic sampling of molecular configurations, the average number of particles in each shell is computed and normalized by the volume of the shell and the system's number density [21].

The RDF exhibits characteristic features that provide immediate physical insights:

- Short-range order: At very small interatomic distances (r → 0), the RDF approaches zero due to strong repulsive forces that prevent molecular overlap [21]

- Contact distance: The first maximum occurs at approximately the molecular diameter (σ), representing the most probable distance between neighboring particles [21]

- Long-range behavior: As r → ∞, g(r) approaches unity, indicating the loss of positional correlation between particles at large distances [21]

RDFs in Thermodynamic Property Calculations

The RDF serves as the fundamental link between microscopic intermolecular interactions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties in fluids and fluid mixtures [21]. Key thermodynamic properties can be directly calculated from the RDF:

- Internal energy (E): Derived from the integral of the pair potential weighted by the RDF

- Pressure (P): Calculated using the virial equation incorporating RDF data

- Compressibility (κ): Related to the long-wavelength limit of the structure factor, which is the Fourier transform of g(r)

- Chemical potential (μ): Determined through thermodynamic integration methods using RDFs

Table 1: Thermodynamic Properties Calculable from RDF Data

| Property | Mathematical Relationship | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy | E = (3/2)NkT + 2πNρ ∫u(r)g(r)r²dr | Pure fluids and mixtures |

| Pressure | P = ρkT - (2πρ²/3) ∫(du/dr)g(r)r³dr | Equation of state development |

| Compressibility | ρkTκ_T = 1 + 4πρ ∫[g(r) - 1]r²dr | Phase behavior prediction |

| Surface Tension | γ = (π/8)ρ² ∫(du/dr)g(r)r⁴dr | Interface studies |

Computational Methodologies for RDF Determination

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocols

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations represent one of the most powerful approaches for obtaining RDFs from first principles [21]. The following protocol outlines a standardized methodology for RDF calculation:

System Preparation

- Initial Configuration: Construct simulation box with appropriate number of molecules (typically 500-10,000 molecules) using Packmol or similar tools

- Force Field Selection: Employ biomolecular force fields (OPLS/AA, CHARMM, AMBER) with specific parameterization for hydrogen-bonding interactions [23]

- Solvation: Embed solute molecules in explicit solvent boxes with appropriate periodic boundary conditions

Equilibration Protocol

- Energy Minimization: Apply steepest descent algorithm for 5,000-50,000 steps to remove bad contacts

- NVT Ensemble: Equilibrate for 100-500 ps at target temperature using Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover thermostats

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate for 100-500 ps at target pressure using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Production Run: Conduct extended simulation (10-100 ns) with 1-2 fs time step

RDF Calculation from Trajectory

- Trajectory Analysis: Use GROMACS, VMD, or custom scripts to compute g(r) [23]

- Sampling Interval: Extract frames every 1-10 ps for analysis

- Bin Size Selection: Typically 0.01-0.02 Å for optimal resolution

- Statistical Averaging: Average over all reference particles and time frames

Experimental Validation Techniques

RDFs can be experimentally validated through several scattering techniques [21]:

- X-ray Scattering: Measures electron density correlations, providing g(r) for atomic positions

- Neutron Scattering: Particularly sensitive to hydrogen positions due to strong neutron-proton interaction

- EXAFS (Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure): Probes local structure around specific atomic species

Table 2: Comparison of RDF Determination Methods

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Time Resolution | System Limitations | Hydrogen Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation | Atomic (0.1 Å) | Femtoseconds | Force field accuracy | High with explicit atoms |

| X-ray Scattering | 0.5-1.0 Å | Milliseconds | Crystalline samples | Low |

| Neutron Scattering | 0.5-1.0 Å | Milliseconds | Deuterium labeling often needed | High |

| EXAFS | 0.02 Å | Seconds | Element-specific | Low |

Hydrogen Bonding Networks: Analysis and Quantification

RDF Signatures of Hydrogen Bonds

In hydrogen-bonded systems, RDFs exhibit characteristic peaks that provide quantitative insight into molecular structure [21]. The first peak between hydrogen (donor) and acceptor atoms (O-H or N-H groups) typically appears at 1.5-2.5 Å, with the intensity of this peak correlating directly with hydrogen bond strength [21]. This specific signature allows researchers to identify and quantify hydrogen bonding interactions in complex biological systems, including protein folding and protein-ligand interactions [21].

For alcohol-aniline binary mixtures, RDF analysis reveals the predominance of OH···O interactions over other hydrogen bond types, with coordination numbers and hydrogen bond statistics showing distinct bunching of alcohol-alcohol hydrogen bonds at lower aniline concentrations [23]. Notably, aniline-aniline interactions remain largely unaffected by concentration changes, demonstrating the selective nature of hydrogen bonding networks [23].

Graph Theoretical Analysis of Hydrogen Bond Networks

Graph theoretical analysis (GTA) provides a complementary approach to RDF for understanding hydrogen bonding topology [23]. Using tools like the NetworkX Python package, researchers can:

- Network Representation: Represent molecules as nodes and hydrogen bonds as edges

- Connectivity Analysis: Identify cyclic structures, chains, and branching patterns

- Cluster Statistics: Quantify the size distribution of hydrogen-bonded aggregates

- Percolation Analysis: Determine conditions for system-spanning hydrogen bond networks

The combination of RDF and GTA offers a comprehensive picture of both local structure (via RDF) and global connectivity (via GTA) in hydrogen-bonded systems [23].

Diagram 1: Hydrogen bonding analysis workflow from MD simulation to graph theory.

Solvation Effects in Molecular Recognition

The Critical Role of Solvent in Molecular Dynamics

Solvation effects play a decisive role in molecular recognition processes, yet they present significant challenges for computational analysis [22]. Implicit solvation models often fail to comprehensively account for the specific nature of solvent effects, while explicit models incur prohibitively high computational costs [22]. This solvation bottleneck particularly impacts drug development professionals seeking to understand protein-ligand interactions, where competitive solvation and solvent cohesion provide thermodynamic driving forces for association [22].

RDF analysis offers a powerful approach to quantify these solvent effects by directly measuring the reorganization of solvent molecules around solutes. The RDF between solute atoms and solvent molecules provides detailed information on:

- Solvation shell structure: Number and arrangement of solvent molecules in direct contact with solute

- Solvent ordering: Degree of orientation correlation between solute and solvent molecules

- Desolvation penalties: Energetic costs associated with displacing solvent molecules during binding

Molecular Balances for Quantifying Solvent Effects

Molecular balances and supramolecular complexes have emerged as valuable experimental tools for dissecting the physicochemical basis of solvent effects in molecular recognition [22]. These systems enable combined experimental and computational analyses, facilitating theoretical analyses that work in concert with experiment [22]. Advanced computational techniques like symmetry adapted perturbation theory (SAPT) and natural bonding orbital (NBO) analysis have been married with experimental observations to elucidate the influence of effects that are difficult to resolve experimentally, such as London dispersion and electron delocalization [22].

Diagram 2: Solvation shells around a solute molecule showing ordering effects.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for RDF and Hydrogen Bond Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Biomolecular systems, liquid mixtures | High performance, free software [23] |

| OPLS/AA Force Field | Potential energy function parameterization | Organic molecules, biomolecules | Optimized for liquids [23] |

| VMD | Molecular visualization and analysis | Trajectory analysis, RDF calculation | Graphical interface, scripting [23] |

| NetworkX | Graph theory analysis | Hydrogen bond network analysis | Python library, complex network metrics [23] |

| Gaussian 09 | Electronic structure calculations | Interaction energy computation | DFT methods (B3LYP) [23] |

Case Study: Alcohol-Aniline Binary Mixtures

Experimental Protocol and Results

A recent molecular dynamics study on mixtures of aniline with 8 primary alcohols (CRH2R+1-OH, R = 1 to 8) provides a exemplary case study of RDF analysis in hydrogen-bonded systems [23]. The research methodology followed this rigorous protocol:

Energy Calculations

- Interaction energies calculated using B3LYP/6-311G++(d,p) density functional theory

- Gaussian 09 software package employed for electronic structure calculations

Molecular Dynamics Parameters

- Simulations performed with GROMACS (V 2020.6)

- OPLS/AA force field for all interactions

- Simulation box visualized using VMD

- Production runs with complete concentration sampling

Analysis Techniques

- RDF calculations for all atomic pairs

- Hydrogen bond statistics using geometric criteria (distance and angle)

- Graph theoretical analysis using NetworkX Python package

The results demonstrated that OH···O interactions dominate the hydrogen bonding network, with alcohol-alcohol interactions showing significant bunching at lower aniline concentrations [23]. This case study highlights how RDF analysis can reveal subtle concentration-dependent effects in hydrogen-bonded binary mixtures with relevance to pharmaceutical formulations.

Thermodynamic Implications

The structural information obtained from RDF analysis of alcohol-aniline mixtures directly explains macroscopic thermodynamic behavior. The bunching of alcohol-alcohol hydrogen bonds at low aniline concentrations creates micro-heterogeneities that influence:

- Excess thermodynamic properties: Deviation from ideal mixing behavior

- Transport properties: Diffusion coefficients and viscosity

- Phase behavior: Miscibility gaps and critical points

These findings underscore the critical role of RDF analysis in connecting molecular-level organization to bulk material properties in hydrogen-bonded systems.

Radial distribution functions provide an essential bridge between the microscopic world of molecular interactions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties, with particular utility in understanding hydrogen-bonded networks and solvation effects [21]. As molecular dynamics simulations continue to advance in temporal and spatial resolution, RDF analysis will play an increasingly important role in drug development efforts, particularly in understanding protein-ligand recognition, solvent effects in binding pockets, and the molecular basis of aqueous solubility.

The integration of RDF analysis with graph theoretical approaches represents a promising direction for extracting more sophisticated topological information from hydrogen-bonded networks [23]. Furthermore, the development of machine learning methods for predicting RDFs from molecular structure may eventually enable rapid screening of solvent effects in pharmaceutical development, potentially reducing the computational cost of explicit solvation models while maintaining physical accuracy [21]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of RDF analysis techniques provides a powerful tool for unraveling the complex role of solvation in molecular recognition and binding.

Simulation in Action: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the influence of the solvent environment is not a mere background detail but a fundamental determinant of biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function. Simulating solvation effects accurately is paramount for achieving predictive power in computational studies, particularly in drug development where ligand binding, protein folding, and molecular recognition all occur in an aqueous, cellular milieu. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the three foundational pillars of setting up solvation simulations: the selection and application of force fields, the choice between solvent models, and the appropriate use of statistical ensembles. Mastering these components enables researchers to construct computationally efficient and physically accurate models of biological processes in their native-like environments.

Force Fields: The Foundation of Molecular Mechanics

Definition and Components

In the context of chemistry and molecular modeling, a force field is a computational model that describes the forces between atoms within molecules or between molecules [24]. It consists of a specific functional form and a set of parameters used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms [24]. In classical MD, which is based on Molecular Mechanics, force fields serve as an approximation to quantum mechanics, making simulations of large systems such as proteins computationally tractable [25] [26].

Force fields calculate the total potential energy of a system as a sum of several contributions, typically divided into bonded and non-bonded interactions [24] [25]. The general form of an additive force field can be expressed as: [ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E{\text{nonbonded}} ] where ( E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} ), and ( E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E{\text{van der Waals}} ) [24].

Table 1: Core Components of a Typical Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Interaction Type | Functional Form (Example) | Description | Atoms Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij}-l{0,ij})^2 ) [24] | Energy cost to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its equilibrium length. | 2 |

| Angle Bending | ( E{\text{angle}} = \frac{k{\theta}}{2}(\theta - \theta_0)^2 ) | Energy cost to bend the angle between three connected atoms from its equilibrium value. | 3 |

| Dihedral/Torsional | ( E{\text{dihedral}} = \frac{Vn}{2}(1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)) ) | Energy associated with rotation around a central bond, dictated by periodicity and phase. | 4 |

| van der Waals | ( E_{\text{vdW}} = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^6 \right] ) (Lennard-Jones) [24] | Models short-range repulsion and London dispersion attraction between non-bonded atoms. | 2 (non-bonded) |

| Electrostatic | ( E{\text{Coulomb}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{r_{ij}} ) [24] | Long-range interaction between permanent partial charges on atoms. | 2 (non-bonded) |

Force Field Types and Parametrization

Force fields can be categorized based on their scope and resolution:

- All-atom: Provide parameters for every atom in a system, including hydrogen [24].

- United-atom: Treat hydrogen atoms in specific groups (e.g., methyl or methylene groups) as a single interaction center with the carbon atom to reduce computational cost [24].

- Coarse-grained: Further sacrifice chemical details by grouping multiple atoms into "pseudo-atoms" to enable simulations of larger systems and longer timescales [24] [26].

- Component-specific vs. Transferable: A component-specific force field is developed for a single substance (e.g., water), while a transferable force field is designed with building blocks (e.g., a methyl group) that can be applied to different molecules [24].

The parameters for these energy functions are derived through a process called parametrization, which uses data from classical laboratory experiments, quantum mechanical calculations, or a combination of both [24]. The assignment of atomic charges, which dominate electrostatic interactions, is particularly critical and often follows quantum mechanical protocols mixed with heuristic approaches [24]. "Atom types" are a key concept, defined not only by the element but also by its chemical environment (e.g., an sp2 carbon in an aromatic ring versus an sp3 carbon in an alkane chain), which determines the set of parameters used [25].

Selection and Application Protocols

Choosing an appropriate force field is critical for the success of a simulation. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for researchers:

- Consult Expert Recommendations: Many force field development groups provide updated web pages with their current recommendations for specific systems (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids, lipids) [25].

- Review Literature for Your System Type: Prioritize force fields that have been successfully validated and are commonly used for systems similar to yours (e.g., specific membrane proteins, carbohydrate polymers). Pay attention to papers that compare force field performance for your molecule of interest [25].

- Prioritize Recent, Well-Maintained Force Fields: Using a recently published force field (e.g., within the last 5 years) from a group with a strong track record generally ensures good results, barring any known, specific issues with your system [25].

- Consider the Need for Reactivity: Standard biomolecular force fields cannot simulate bond breaking and forming. For processes involving chemical reactions, specialized reactive force fields (e.g., ReaxFF) are required [25] [26].

- Ensure Comprehensive Parametrization: Before starting a simulation, verify that all components of your system (e.g., protein, water, ions, ligands, cofactors) have been parametrized for your chosen force field. This may require finding or generating parameter files for non-standard molecules.

Solvent Models: Implicit vs. Explicit Approaches

Implicit Solvent (Continuum) Models

Implicit solvent models replace explicit solvent molecules with a homogeneously polarizable medium, characterized primarily by its dielectric constant (ε) [27] [28]. The solute is embedded in a cavity within this continuum, and the model calculates the solvent's effect as a potential of mean force (PMF) [28]. The solvation free energy (( \Delta G{\text{sol}} )) is typically decomposed into several contributions [28]: [ \Delta G{\text{sol}} = \Delta G{\text{cav}} + \Delta G{\text{vdW}} + \Delta G{\text{ele}} ] where ( \Delta G{\text{cav}} ) is the energy cost of creating a cavity in the solvent, ( \Delta G{\text{vdW}} ) represents van der Waals interactions, and ( \Delta G{\text{ele}} ) is the electrostatic component [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Popular Implicit Solvent Models

| Model Name | Underlying Equation | Key Features | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| SASA (Solvent-Accessible Surface Area) [28] | ( V{\text{solv}}^{\text{SASA}} = \sumi \sigmai^{\text{SASA}} \cdot \text{SASA}i ) | Models solvation energy as proportional to the surface area of the solute. Fast to compute. | Often used to model non-polar contributions, or the entire solvation energy in conjunction with specific parametrization. |

| Generalized Born (GB) [28] | ( \Delta G{\text{solv}} \approx -\frac{1}{2} \left(1 - \frac{1}{\epsilon}\right) \sum{i,j} \frac{qi qj}{f{GB}(r{ij}, Ri, Rj)} ) | An approximation to the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. Computationally efficient for electrostatic solvation. | Default implicit solvent in many MD packages for rapid equilibration and folding/unfolding studies. |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) [28] | ( \vec{\nabla} \cdot [\epsilon(\vec{r}) \vec{\nabla} \Phi(\vec{r})] = -\frac{\rho(\vec{r})}{\epsilon_0} ) (Poisson) | Solves for the electrostatic potential numerically. Generally more accurate but computationally heavier than GB. | Detailed electrostatic analysis, such as binding free energy calculations where electrostatic accuracy is paramount. |

| PCM (Polarizable Continuum Model) [27] | - | A variant of PB that uses a more sophisticated cavity construction. | Widely used in quantum chemistry calculations and their MD/MM extensions. |

| COSMO (Conductor-like Screening Model) [27] | - | Uses a scaled conductor boundary condition, a robust approximation to dielectric equations. | Popular in quantum chemistry and increasingly in MD applications. |

Advantages and Limitations: The primary advantage of implicit models is computational efficiency, as they add few or no degrees of freedom to the simulation [27] [28]. This makes them ideal for conformational searches, rapid equilibration, and any application where the specific interactions of individual water molecules are not critical. However, they fail to capture specific solvent effects such as hydrogen bond fluctuations at the solute surface, water dipole reorientation in response to conformational changes, and the presence of bridging water molecules [27] [28]. They are a good approximation where the solvent is isotropic and bulk-like.

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvent models treat solvent molecules as individual, discrete molecules with their own coordinates and degrees of freedom [27]. This provides a more physically realistic picture, allowing for the simulation of specific solute-solvent interactions, solvent structuring (e.g., hydration shells), and the microscopic details of hydrophobic effects.

The most common explicit solvent is water, for which many optimized models exist. These are often rigid, three-site models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC) that fix bond lengths and angles to allow for a larger integration timestep [27] [26]. The parameters for these models, including point charges and Lennard-Jones parameters, are fitted to reproduce experimental bulk properties like density and enthalpy of vaporization [27]. A new generation of polarizable force fields (e.g., AMOEBA) is also being developed, which account for changes in the molecular charge distribution in response to the environment, offering higher accuracy at a greater computational cost [27].

Advantages and Limitations: The key advantage is physical realism, as they can capture all specific and local solvent effects. The main disadvantage is the high computational cost, as typically thousands of solvent molecules must be added to solvate a solute, drastically increasing the number of particles and the complexity of non-bonded interactions.

Hybrid Solvent Models

Hybrid methodologies attempt to balance the efficiency of implicit models with the spatial resolution of explicit models [27]. The most prominent is the QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) scheme, where a small, chemically active region (e.g., an enzyme's active site) is treated with accurate QM methods, the surrounding biomolecule is treated with a classical MM force field, and the distant solvent is treated as an implicit continuum [27]. Another approach is the Reference Interaction Site Model (RISM), which allows the solvent density to fluctuate in the local environment, providing a description of the solvent shell behavior while being closer to an implicit representation [27].

Figure 1: A decision workflow for selecting an appropriate solvent model for a molecular dynamics simulation.

Statistical Ensembles: Controlling Thermodynamic Conditions

In molecular dynamics, a statistical ensemble defines the set of possible system states that are consistent with specific macroscopic constraints (e.g., constant temperature, pressure) [29]. The choice of ensemble is crucial for mimicking experimental conditions and for calculating the appropriate thermodynamic free energies [30].

Table 3: Key Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Acronym | Fixed Variables | Controlled via | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical | NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | No thermostat or barostat. | Studying isolated systems; production runs after equilibration for spectral calculations [29] [30]. |

| Canonical | NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Langevin) [29] [31]. | Conformational searches in vacuum; simulations where pressure is not defined or not critical [29]. |

| Isothermal-Isobaric | NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Thermostat and Barostat. | Simulating condensed phases (liquids, solids) to achieve correct density, volume, and pressure; mimics most lab experiments [29] [30]. |

| Isobaric-Isenthalpic | NPH | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Enthalpy (H) | Barostat without temperature control. | Less common; analogue of NVE for constant pressure [29]. |

Selection Criteria and Practical Considerations

The choice of ensemble should be guided by the experiment you wish to simulate or the thermodynamic free energy you need to calculate [30]:

- For a gas-phase reaction without a buffer gas, the NVE ensemble may be appropriate [30].

- For processes in the liquid phase, the NPT ensemble is almost always the most realistic choice, as bench experiments are typically conducted at constant pressure and temperature [30].