Solving Molecular Dynamics Energy Minimization Failures: A Troubleshooting Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and resolving common failures in molecular dynamics (MD) energy minimization.

Solving Molecular Dynamics Energy Minimization Failures: A Troubleshooting Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and resolving common failures in molecular dynamics (MD) energy minimization. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles of minimization algorithms, practical application of methods like steepest descent and conjugate gradients, systematic diagnosis of convergence problems and force field errors, and validation techniques to ensure result reliability. By integrating traditional approaches with emerging machine learning solutions, this guide aims to enhance simulation stability and accuracy in biomedical research, from drug discovery to protein folding studies.

Understanding Energy Minimization: Core Principles and Common Pitfalls

The Critical Role of Energy Minimization in Stable MD Simulations

Energy minimization is a foundational step in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, crucial for relieving atomic clashes and preparing a stable system for production runs. Without proper minimization, simulations can fail due to unphysically high forces that lead to numerical instabilities, integration errors, or complete simulation collapse. This technical guide addresses the critical role of energy minimization and provides targeted troubleshooting for common failure scenarios encountered by researchers.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Energy Minimization Failures

Diagnostic Table of Common Errors

The table below summarizes frequent energy minimization issues, their symptoms, and initial diagnostic steps.

| Error Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Initial Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Infinite forces (Fmax = inf) and "atoms are overlapping" message [1] | Severe atomic clashes; Topology-coordinate mismatch [1] | Check atom identities in topology vs. coordinate files [1] |

| Forces not converging to requested Fmax despite machine precision convergence [2] | Systematically poor initial structure; Inadequate minimization parameters [2] | Verify initial structure quality; Consider multi-stage minimization [3] |

| Segmentation fault during minimization or subsequent equilibration [2] | Critical software error; Possible hardware/GPU incompatibility [2] | Run on CPU only; Check for system corruption; Verify installation |

| "Residue not found in topology database" during topology generation [4] | Missing force field parameters for molecule/residue [4] | Verify residue naming; Use external tools for parameterization [4] |

| "Long bonds and/or missing atoms" [4] | Incomplete molecular structure in initial coordinates [4] | Inspect PDB file for REMARK 465/470 (missing atoms); Model missing atoms |

Resolving Atomic Overlaps and Infinite Forces

Atomic overlaps creating infinite forces represent one of the most common and critical failures in energy minimization.

Problem Analysis: When atoms are placed impossibly close in the initial configuration, the potential energy and forces calculated by the force field can become astronomically high (e.g., ~10¹⁹ kJ/mol) [1], causing the minimizer to fail immediately. This often manifests with warnings like "the force on at least one atom is not finite" [1].

Solution Protocol:

- Inspect the Offending Atom: The minimization log identifies the problematic atom (e.g., "Maximum force = inf on atom 1251") [1]. Visualize this atom and its local environment using molecular visualization software.

- Verify Topology-Coordinate Consistency: A frequent cause is a mismatch between the atom names or types in the structure file (.gro, .pdb) and the topology file (.top). Meticulously check that the ligand or residue in question matches the definition in the force field's residue topology database (rtp) [1] [4].

- Rebuild Problematic Fragments: If the initial model was built with missing atoms (often noted in REMARK 465/470 of PDB files), use modeling software to reconstruct the missing portions before minimization [4].

- Use a Multi-Stage Minimization Approach: Start with a gentle minimizer like steepest descent for a few steps to relieve the worst clashes, then switch to a more efficient algorithm like conjugate gradient for finer convergence [3].

Addressing Force Convergence Failures

Sometimes minimization stops without achieving the desired force tolerance (Fmax), reporting convergence only to machine precision.

Problem Analysis: This indicates the minimizer cannot find a direction to move atoms that further lowers the energy, given the numerical constraints of the algorithm and the system's current configuration. This does not necessarily mean the system is stable enough for dynamics [2].

Solution Protocol:

- Adjust Minimization Parameters: In your molecular dynamics parameter (.mdp) file, consider increasing the maximum number of steps (

nsteps). For steepest descent, slightly increasing the initial step size (emstep) can sometimes help, but caution is required to maintain stability [5] [2]. - Switch Minimization Algorithms: If steepest descent fails to converge, try the conjugate gradient (

integrator = cg) or L-BFGS (integrator = l-bfgs) algorithms, which are more efficient for finding minima in complex landscapes [5]. - Consider Double Precision: While single precision is often sufficient, for systems with particularly difficult energy landscapes, compiling and running GROMACS in double precision can provide the necessary numerical accuracy to achieve convergence [1].

- Iterative Minimization and Equilibration: It is sometimes effective to run a short, gentle minimization, followed by a brief position-restrained MD (NVT) simulation, and then another round of minimization. This can help "nudge" the system out of a difficult configuration.

Handling Segmentation Faults and Crashes

Segmentation faults during or immediately after minimization are often related to deeper software or system issues.

Problem Analysis: A segmentation fault indicates the program tried to access memory it was not permitted to, leading to a crash. This can be caused by corrupted input files, bugs in the code, or hardware incompatibilities, especially with GPU acceleration [2].

Solution Protocol:

- Test on CPU: Run the same simulation using only CPU resources (e.g., remove flags like

-nb gpu -pme gpu). If it runs, the issue is likely with the GPU setup or code paths [2]. - Check Input File Integrity: Ensure all input files (.tpr, .gro, .top) are complete and uncorrupted. Try regenerating the .tpr file with

gmx grompp. - Verify System Components: Scrutinize the topology for any unusual molecules, parameters, or inclusions that might trigger a software bug. Pay special attention to non-standard residues and metal ions.

Energy Minimization Workflow and Best Practices

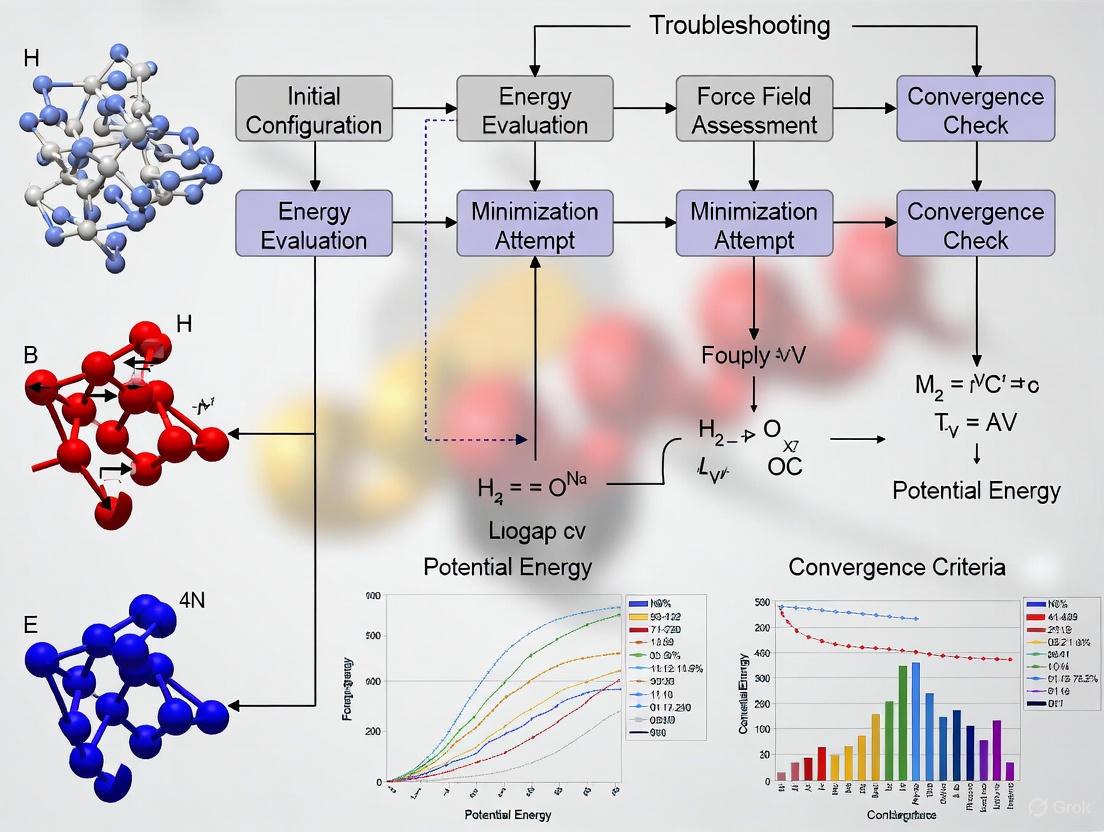

The following diagram illustrates a robust, decision-based workflow for successful energy minimization, integrating the troubleshooting steps outlined above.

Diagram Title: Energy Minimization Troubleshooting Workflow

Step-by-Step Minimization Protocol

- Initial System Preparation: Before minimization, ensure your system's topology and coordinates are consistent. Use tools like

pdb2gmxor external parameterization software correctly, especially for non-standard molecules [4]. - Stage 1: Steepest Descent: This algorithm is robust for relieving severe clashes and should be used first. A typical parameterization in a GROMACS

.mdpfile is [5] [2]: - Stage 2: Conjugate Gradient: After the largest forces are eliminated, switch to a more efficient algorithm for final convergence.

- Validation: Before moving to equilibration, verify the potential energy of the system has dropped to a reasonable, negative value (e.g., for a solvated protein system, typically on the order of -10⁵ to -10⁶ kJ/mol), indicating favorable non-bonded interactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists critical "research reagents" – software tools, parameters, and methods – essential for successful energy minimization.

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descents Algorithm [5] | Initial "coarse" minimization; Highly effective at relieving severe atomic clashes. | Robust but inefficient for fine convergence; Use first. |

| Conjugate Gradient / L-BFGS [5] [6] | Subsequent "fine" minimization; More efficiently finds local minima after clashes are relieved. | Use after steepest descent; L-BFGS is often faster but may have compatibility constraints [5]. |

| Force Fields (e.g., AMBER ff14SB, GAFF) [3] | Provides the functional form and parameters (bonds, angles, charges) to calculate potential energy. | Choice is system-dependent; Non-standard residues require parameterization (e.g., with GAFF) [3]. |

| Molecular Viewers (e.g., Chimera, VMD) | Visual inspection of atomic overlaps, missing atoms, and post-minimization structure. | Critical for diagnosing atom-specific errors identified in log files [1]. |

| Antechamber [3] | Automates assignment of force field parameters and charges for non-standard residues and small molecules. | Necessary for generating topologies for ligands not in standard force field databases [3]. |

| Position Restraints | Harmonically restraints heavy atoms or specific groups during initial minimization/equilibration. | Allows solvent to relax around a fixed solute, preventing unrealistic protein backbone movements. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My minimization fails with "atoms are overlapping," but my structure looks fine visually. What should I do?

The problem is often not a visual overlap but a mismatch between your coordinate file and topology. The energy calculation expects specific atom names and types defined in the force field's residue database. An atom named "CB1" in your coordinate file will not be recognized if the topology expects "CB". Carefully check the atom names in your input structure against the names in the force field's residue topology (.rtp) file [1] [4].

Q2: What is the difference between "steepest descent" and "conjugate gradient," and when should I use each?

- Steepest Descent: This algorithm always moves atoms in the direction of the negative gradient (steepest energy decrease). It is very robust and effective at quickly reducing large forces and energies from severe clashes. It should be used for the initial stage of minimization [3].

- Conjugate Gradient: This method uses information from previous steps to choose a more efficient search direction. It converges much faster than steepest descent once the system is near a minimum but can be less stable with large initial forces. Use it for the second stage of minimization after the worst clashes are resolved [5] [3].

Q3: How do I know if my energy minimization was successful?

A successful minimization is typically judged by two criteria:

- Convergence: The maximum force (Fmax) in the system falls below your specified tolerance (

emtol). This is the primary success metric [5]. - Reasonable Potential Energy: The total potential energy should be a large, negative value, indicating favorable van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. A positive or extremely high negative energy suggests persistent problems [2].

Q4: Can I use energy minimization to find the global minimum of my protein structure?

No. Energy minimization locates the nearest local minimum on the potential energy surface. It does not cross energy barriers. To search for a global minimum or sample different conformations, you must use methods like molecular dynamics simulation at finite temperature, replica-exchange MD, or other enhanced sampling techniques [7] [3]. Minimization is for "relaxing" a given structure, not for folding or extensive conformational searching.

PES Fundamentals FAQ

What is a Potential Energy Surface (PES)? A Potential Energy Surface describes the energy of a system, especially a collection of atoms, in terms of certain parameters, normally the positions of the atoms. The PES is a conceptual tool for analyzing molecular geometry and chemical reaction dynamics, creating a smooth energy "landscape" where chemistry can be viewed from a topology perspective of particles evolving over "valleys" and "passes" [8] [9]. For a system with two degrees of freedom, the value of the energy is analogous to the height of the land as a function of two coordinates [9].

What are stationary points on a PES? Stationary points are points on the PES where the gradient (first derivative of energy with respect to position) is zero [8]. The two most important types of stationary points are:

- Minima: Correspond to the most stable structures of a molecule, such as reaction intermediates or stable products [8]. At a minimum, the potential energy surface curves upwards [8].

- Saddle Points: Correspond to transition states—the highest energy point on the lowest energy pathway connecting two minima [9]. These are maxima along the reaction coordinate but minima in all other directions [9].

What is the mathematical foundation of a PES? The PES originates from solving the time-independent Schrödinger equation, $\hat H \Psi(r, R) = E \Psi(r, R)$, under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [8]. This approximation separates nuclear and electronic motion, allowing the wavefunction to be approximated as $\Psi(r, R) \approx \Psi(r)\Phi(R)$ [8]. The total energy for a given nuclear configuration $R$ is then $E{tot \; R} = E{el \; R} + E_{nuc \; R}$ [8].

What are internal coordinates and why are they important? Internal coordinates describe molecular geometry in terms of bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles, eliminating the "external coordinates" related to translation and rotation [8]. For a system of N atoms, this typically results in $3N - 6$ internal coordinates (or $3N - 5$ for linear molecules) [8]. This representation is computationally more efficient than Cartesian coordinates and directly relevant to chemical bonding [8].

Troubleshooting Energy Minimization Failures

Why does my energy minimization stop abruptly without force convergence? This common error in molecular dynamics simulations occurs when:

- The minimization algorithm attempts steps that are too small to significantly reduce forces [2] [10]

- There is no change in energy between consecutive steps despite persistent high forces [2] [10]

- The system contains severe atomic clashes generating excessively high potential energies and forces [10]

Table 1: Common Energy Minimization Error Messages and Causes

| Error Message | Possible Causes | System Context |

|---|---|---|

| "Energy minimization has stopped, but the forces have not converged..." [2] | - Severe atomic clashes [10]- Incorrect position restraints [10]- Inappropriate constraint settings [2] | Protein-DNA complex [2] |

| "Potential Energy = 1.3146015e+32 Maximum force = 1.3916486e+11" [10] | - Initial structure with overlapping atoms [10]- Incorrect system building [10] | Phospholipid membrane simulation [10] |

| Segmentation fault during minimization [2] | - Software/hardware compatibility issues- Problematic position restraint files | After minimization during equilibration [2] |

How can I resolve atomic clashes causing minimization failures?

- Visualize the system: Identify atoms with extremely high forces and check for steric clashes [10]

- Check system building procedures: Ensure the initial structure was built correctly without overlapping atoms [10]

- Remove unnecessary restraints: Position restraints (

define = -DPOSRES) may interfere with minimization and should be temporarily removed [10]

What algorithmic adjustments can improve minimization?

- Switch algorithms: If steepest descent fails, try conjugate gradient methods [2]

- Adjust parameters: Modify the maximum force tolerance (

emtol) or step size (emstep) [2] - Multiple minimization rounds: Perform successive minimizations with different parameters [2]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

PES Stationary Point Identification Protocol

Objective: Systematically identify and characterize stationary points on a PES [11]

Methodology:

- Energy Calculation: Compute the energy for atomic arrangements using quantum chemical methods (e.g., Density Functional Theory) [11]

- Gradient Evaluation: Calculate the first derivatives of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates [8]

- Geometry Optimization: Iteratively adjust nuclear coordinates until the gradient approaches zero [8]

- Hessian Analysis: Compute second derivatives to characterize the nature of stationary points [11]

High-Index Saddle Dynamics (HiSD) Method: Recent advanced approaches use improved HiSD schemes combined with downward and upward searches to systematically enumerate stationary points and their connections [11]. This method introduces generalized coordinates to encode crystals that satisfy translational and rotational invariance [11].

Diagram Title: PES Exploration Workflow

Stationary-Point Network Construction

Objective: Create a comprehensive representation of PES topology using a stationary-point network (SPN) [11]

Procedure:

- Stationary Point Identification: Locate all minima and saddle points where the gradient vanishes [11]

- Connection Mapping: Establish pathways between connected stationary points [11]

- Network Construction: Build a graph with nodes representing stationary points and edges representing their connections [11]

- Visualization: Create SPN diagrams to visualize and analyze complex PES terrains [11]

Application Example: For crystalline materials like GaN and Si, this approach has discovered hidden transition pathways with lower enthalpy barriers than previously known [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for PES Exploration

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [2] [12] | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Energy minimization, force field applications [2] |

| xtb Software [8] | Quantum chemical geometry optimization | Fast optimization for structures under 100 atoms [8] |

| VASP Package [11] | First-principles density functional theory calculations | Energy and force calculations for crystalline systems [11] |

| AMBER Force Fields (ff19SB) [2] | Protein force field parameters | Protein-DNA complex simulations [2] |

| pdb2gmx [12] | Topology generation from PDB files | Building block assembly and topology creation [12] |

Advanced PES Topology Visualization

Diagram Title: PES Topology with Stationary Points

The Stationary-Point Network (SPN) provides a powerful framework for visualizing complex PESs, where nodes represent stationary points and edges represent their connections [11]. This approach enables researchers to discover hidden transition pathways with low energy barriers that might be missed with conventional sampling methods [11].

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, energy minimization is a critical first step used to find the stable, low-energy configuration of a molecular system before beginning a production run. It involves adjusting atomic coordinates to reduce the net forces on atoms until a minimum on the potential energy surface is reached. This process helps avoid unrealistic high-energy configurations that could lead to simulation instability or failure. The three most common algorithms for this task are Steepest Descent, Conjugate Gradient, and L-BFGS, each with distinct mathematical foundations and performance characteristics that make them suitable for different scenarios in computational drug development and research.

Algorithm Mechanics and Mathematical Foundations

Steepest Descent Method

The Steepest Descent method is one of the simplest optimization algorithms. It relies exclusively on first-derivative information (the gradient) to find the minimum of a function.

Mathematical Formulation: The core update formula for Steepest Descent is: [ x{new} = x{old} - \gamma \nabla E(x{old}) ] where ( \nabla E(x{old}) ) is the gradient of the potential energy function at the current geometry, and ( \gamma ) is a constant step size parameter [13].

Mechanism: The algorithm moves in the direction opposite to the largest gradient (i.e., the steepest descent) at the current point. Once a minimum in that direction is found, a new minimization begins from that point in the new steepest direction. This process continues until a minimum is reached in all directions within a specified tolerance [13].

Key Characteristics:

- Uses only gradient information (first derivative)

- Assumes the second derivative is constant

- Generally requires more steps than higher-order methods

- Often exhibits oscillatory behavior when approaching the minimum

Conjugate Gradient Method

The Conjugate Gradient (CG) method improves upon Steepest Descent by incorporating information from previous search directions to achieve more efficient convergence.

Mathematical Formulation:

CG uses the following iterative process:

[

x{k+1} = xk + \alphak pk

]

[

pk = rk - \sum{i

Conjugacy Principle: Two vectors ( u ) and ( v ) are conjugate with respect to a positive definite matrix ( A ) if: [ u^T A v = 0 ] This conjugacy condition ensures that each step minimizes the function in a direction that does not spoil the minimization achieved in previous directions [14] [15].

Mechanism: Unlike Steepest Descent, CG mixes in a component of the previous search direction when determining the new direction. This approach prevents the oscillatory behavior typical of Steepest Descent and typically converges in at most n steps for an n-dimensional quadratic problem [13] [15].

L-BFGS Algorithm

The Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (L-BFGS) algorithm is a quasi-Newton method that approximates the second derivative (Hessian) information without explicitly storing the full matrix.

Mathematical Foundation: L-BFGS builds upon the BFGS update formula: [ B{k+1} = Bk - \frac{Bk sk sk^T Bk^T}{sk^T Bk sk} + \frac{yk yk^T}{yk^T sk} ] where ( sk = x{k+1} - xk ) is the change in parameters and ( yk = \nabla f{k+1} - \nabla f_k ) is the change in the gradient [16].

Limited-Memory Approach: Instead of storing the complete Hessian approximation (which would require O(n²) memory), L-BFGS stores only the last m vector pairs (typically m = 3-20), significantly reducing memory usage to O(n·m) [17] [16] [18].

Two-Loop Recursion: L-BFGS uses an efficient two-loop recursion to compute the search direction:

- First Loop (Forward): Computes intermediate quantities using recent vector pairs

- Middle Step: Applies initial Hessian approximation

- Second Loop (Backward): Refines the search direction using stored vectors [16]

This approach allows L-BFGS to maintain curvature information without the computational burden of storing and manipulating large matrices.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Analysis

Table 1: Algorithm Characteristics Comparison

| Characteristic | Steepest Descent | Conjugate Gradient | L-BFGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Derivative Order | First-order | First-order | Quasi-Second-order |

| Memory Requirements | O(n) | O(n) | O(n·m) |

| Convergence Rate | Linear | Superlinear (theoretical) | Superlinear |

| Computational Cost per Step | Low | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Typical Use Cases | Initial minimization, very rough surfaces | Medium to large systems, good initial guess | Large systems, expensive gradients |

Table 2: Empirical Performance on Rosenbrock Function

| Algorithm | Iterations | Function Evaluations | Time (seconds) | Solution Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-BFGS | 24 | 24 | 0.0046 | 0.00000 |

| Conjugate Gradient | 2129 | ~3000 | 0.0131 | 0.00001 |

| Steepest Descent | ~5000* | ~5000* | ~0.0300* | 0.00001* |

Note: Steepest Descent values are estimates based on typical performance; actual values may vary [17] [18].

Table 3: GROMACS Implementation Comparison

| Algorithm | GROMACS Integrator | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | steep |

Initial stages of minimization | Slow convergence near minimum |

| Conjugate Gradient | cg |

Pre-normal mode analysis | Requires occasional steepest descent steps |

| L-BFGS | l-bfgs |

Fast convergence for large systems | Not yet parallelized in GROMACS |

Troubleshooting Common Energy Minimization Failures

Convergence Problems

Problem: Minimization fails to converge within the allowed steps.

- Cause 1: Poor initial structure with severe steric clashes.

- Solution: Use stronger minimization parameters initially (e.g., Steepest Descent with large initial step size) before switching to more advanced algorithms.

- Cause 2: Incorrect convergence criteria.

- Solution: Adjust the force tolerance (

emtolin GROMACS). For stable minimization, the maximum force should typically be < 1000 kJ/mol/nm initially, and < 10-50 kJ/mol/nm for final minimization [5].

- Solution: Adjust the force tolerance (

- Cause 3: Incompatible force field parameters.

- Solution: Verify bond lengths, angles, and dihedral parameters match your molecular system.

Problem: Convergence is unacceptably slow.

- Cause 1: Using Steepest Descent near the minimum.

- Solution: Switch to Conjugate Gradient or L-BFGS after initial rough minimization.

- Cause 2: Poorly conditioned problem with variables of vastly different scales.

- Solution: Implement variable scaling or preconditioning [18].

- Cause 3: Memory parameter too small in L-BFGS.

- Solution: Increase the number of stored vector pairs (typically to 10-15).

Numerical Instabilities

Problem: Energy becomes NaN during minimization.

- Cause 1: Extremely high forces from atomic overlaps.

- Solution: Reduce initial step size; use Steepest Descent with small steps initially.

- Cause 2: Incorrect charge assignments or missing parameters.

- Solution: Check topology for missing parameters or unrealistic charge distributions.

- Cause 3: Numerical overflow in force calculations.

- Solution: Verify cut-off schemes and neighbor searching parameters.

Problem: Forces oscillate without decreasing.

- Cause 1: Step size too large for the potential energy surface.

- Solution: Reduce step size parameter; for L-BFGS, ensure line search is enabled.

- Cause 2: Incorrect gradient calculations.

- Solution: Verify analytical gradients against numerical approximations if possible.

Algorithm-Specific Issues

L-BFGS Problems:

- Hessian approximation becomes inaccurate: Reset the Hessian approximation or switch to Steepest Descent briefly [19] [16].

- Memory issues with large systems: Reduce the number of stored vectors (m) or switch to Conjugate Gradient.

Conjugate Gradient Problems:

- Loss of conjugacy due to round-off error: Periodically reset the search direction to the steepest descent direction [5] [15].

- Slow convergence on ill-conditioned problems: Implement preconditioning using diagonal Hessian approximations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which algorithm should I choose for my biomolecular system?

- A: Use Steepest Descent for the first 50-100 steps to eliminate large forces, then switch to L-BFGS for faster convergence. For very large systems (>100,000 atoms) with memory constraints, use Conjugate Gradient [5] [18].

Q2: How do I know if my minimization has converged properly?

- A: Check that the maximum force is below your tolerance (typically 10-100 kJ/mol/nm for biomolecular systems) and that the energy has stabilized. Also verify that the energy decrease per step approaches zero [19] [5].

Q3: Why does L-BFGS sometimes perform worse than Conjugate Gradient?

- A: For computationally inexpensive functions, L-BFGS's overhead per iteration may make it slower than CG despite fewer iterations. Also, on extremely ill-conditioned problems, L-BFGS can degenerate to Steepest Descent behavior [18].

Q4: How do I set the optimal memory parameter for L-BFGS?

- A: Start with m=5-10 for small systems (<10,000 atoms) and m=10-15 for larger systems. Increase if convergence is slow, decrease if memory is limited [16] [18].

Q5: Can I restart a minimization from a previous run?

- A: Yes, most MD packages support restart capabilities. For L-BFGS and BFGS, it's crucial to also save the Hessian approximation or trajectory to maintain convergence properties [19].

Q6: How do I handle minimization failures with membrane proteins or complex systems?

- A: Use multi-stage minimization: (1) Steepest Descent with position restraints on protein backbone, (2) Steepest Descent on all atoms, (3) Conjugate Gradient or L-BFGS for final convergence.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Energy Minimization Protocol

Diagram 1: Energy Minimization Workflow

Force Tolerance Selection Guidelines

For molecular dynamics simulations, the appropriate force tolerance depends on your subsequent simulation type:

- Equilibration MD: 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm

- Production MD: 10-100 kJ/mol/nm

- Normal Mode Analysis: < 1 kJ/mol/nm (requires double precision)

Algorithm Switching Protocol

When transitioning between algorithms:

- From Steepest Descent to CG/L-BFGS: Wait until energy decrease per step becomes gradual (not oscillatory)

- Between CG variants: Possible without loss of information

- To/from L-BFGS: Save trajectory information to preserve Hessian approximation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Software Tools for Energy Minimization

| Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation package with multiple minimizers | Biomolecular systems, high performance |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python package for structure optimization | Materials science, surface chemistry |

| ALGLIB | Numerical optimization library | Custom optimization implementations |

| AMBER | MD package with minimization capabilities | Biomolecular simulations, drug design |

| NAMD | Scalable MD software | Large biomolecular complexes |

Table 5: Critical Parameters and Their Functions

| Parameter | Function | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|

| Force Tolerance (emtol) | Determines convergence criterion | 10-1000 kJ/mol/nm |

| Step Size (emstep) | Maximum displacement per step | 0.001-0.1 nm |

| L-BFGS Memory (m) | Number of stored vector pairs | 3-20 |

| CG Steepest Descent Frequency | How often to reset to steepest descent | Every 10-100 CG steps |

| Update Frequency | How often to update neighbor lists | Every 10-20 steps |

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Preconditioning Techniques

Preconditioning transforms the optimization problem to improve its conditioning and accelerate convergence:

Diagonal Preconditioning:

- Scales variables based on their magnitudes

- Essential when atomic masses vary significantly

- Implemented via variable scaling functions in optimization packages [18]

Incomplete Cholesky Factorization:

- Approximates the Hessian for more effective preconditioning

- Particularly useful for systems with varying stiffness

Hybrid Approaches

For challenging systems, combine multiple algorithms:

- Stage 1: Steepest Descent with position restraints to remove severe clashes

- Stage 2: Pure Steepest Descent to reduce forces below 1000 kJ/mol/nm

- Stage 3: L-BFGS with moderate memory (m=10) for rapid convergence

- Stage 4: Conjugate Gradient for final polishing if needed

Monitoring and Diagnostics

Implement these checks to detect minimization problems early:

- Energy Conservation: Monitor energy decrease per step; sudden increases indicate problems

- Gradient Norm: Should decrease monotonically in well-behaved minimization

- Parameter Updates: Watch for unusually large coordinate changes

- Convergence History: Track force reduction rates to identify stagnation

Diagram 2: Minimization Troubleshooting Decision Tree

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

1. My system's energy and density stabilize quickly, but the pressure remains unstable. Is the simulation converged?

No, your simulation has likely not reached full equilibrium. While energy and density can converge rapidly in the initial stages of a simulation, pressure often requires a significantly longer time to stabilize. [20] Relying solely on energy and density as indicators is insufficient and can lead to inaccurate results. You should monitor additional properties, such as the Radial Distribution Function (RDF), particularly for key molecular components like asphaltenes, which converge much slower and are a better indicator of true system equilibrium. [20]

2. What is a more reliable metric than energy for assessing the equilibrium of my molecular dynamics (MD) system?

The convergence of the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) curve is a more robust indicator of system equilibrium, especially for complex components. [20] In systems such as asphalt, the resin, aromatics, and saturates may converge quickly, but the asphaltene-asphaltene RDF curve converges much slower. The simulation can only be considered truly balanced once this curve has stabilized. [20] Non-converged RDF curves often appear as a superposition of multiple irregular peaks and exhibit considerable fluctuations. [20]

3. How can I simulate bond breaking in my MD study, as my current harmonic force field does not allow it?

You can replace the harmonic bond potentials in your force field with reactive Morse potentials, as implemented in methods like the Reactive INTERFACE Force Field (IFF-R). [21] This substitution allows for bond dissociation while maintaining the accuracy of the original non-reactive force field and is compatible with common force fields like CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS-AA. [21] This approach is about 30 times faster than complex bond-order potentials like ReaxFF. [21] The key parameters required are the bond dissociation energy ((D{ij})) and the equilibrium bond length ((r{0,ij})), which can be derived from experimental data or quantum mechanical calculations. [21]

4. What are the primary causes of force divergence and structural instability during energy minimization and equilibration?

Force divergence often stems from:

- Excessive repulsive forces in the initial system configuration, which can cause atomic velocities to become too high. [20]

- Incorrect force field parameters for the specific atoms and bonds in your system.

- Insufficient energy minimization before starting the dynamics simulation, failing to relieve high-energy clashes. Structural instability can arise from improper thermostat/barostat settings, an unstable integration time step, or modeling chemical reactions with a non-reactive (harmonic) force field. [21]

5. How can machine learning help troubleshoot issues related to molecular properties?

Machine Learning (ML) can analyze MD-derived properties to predict complex behaviors like solubility, potentially identifying the root cause of simulation instability. [22] For instance, ML models can use properties such as Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies (LJ), and Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to predict aqueous solubility, which is critical for drug development. [22] If a simulated molecule is predicted to have poor solubility based on these MD properties, it might indicate underlying stability issues in the simulation that reflect real-world physicochemical challenges. [22]

Quantitative Data and Parameter Reference

| System Property | Typical Relative Convergence Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (Potential, Kinetic) | Fast | Stabilizes quickly in initial stages; not a sole indicator of equilibrium. |

| Density | Fast | Stabilizes quickly in initial stages; not a sole indicator of equilibrium. |

| Pressure | Slow | Requires much longer time to equilibrate compared to energy/density. |

| RDF (Aromatics, Resins) | Moderate | Faster than asphaltenes. |

| RDF (Asphaltene-Asphaltene) | Very Slow | The definitive indicator for full system equilibrium. |

| Morse Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Description / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Energy | (D_{ij}) | System-dependent | Bond dissociation energy; from experiment or quantum mechanics (CCSD(T), MP2). |

| Equilibrium Bond Length | (r_{0,ij}) | System-dependent | Same as in the original harmonic potential. |

| Width Parameter | (\alpha_{ij}) | ~2.1 ± 0.3 Å⁻¹ | Fits the Morse curve to the harmonic curve near the resting state; can be refined via IR/Raman spectroscopy. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Validating System Convergence via RDF Analysis

Objective: To determine if an MD simulation has reached true thermodynamic equilibrium beyond energy and density stabilization. [20]

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Construct your initial model with a density much lower than the target final density to ensure a random molecular distribution. [20]

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to eliminate excessive repulsive forces and prevent unstable atomic velocities. [20]

- Equilibration: Run a relatively long equilibration simulation under the desired temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble). [20]

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate the RDFs for all key molecular components in your system throughout the simulation trajectory.

- Convergence Check: Monitor the RDF curves over time. The system is considered equilibrated only when the RDF for the slowest-converging component (e.g., asphaltene-asphaltene) shows a stable, smooth profile with a distinct peak. [20]

Protocol 2: Implementing Reactivity with Morse Potentials

Objective: To simulate bond dissociation and failure in materials using a reactive force field. [21]

Methodology:

- Parameter Identification: Identify the specific bond types (atom pairs ij) you wish to make reactive.

- Parameter Acquisition: For each reactive bond type, obtain:

- The equilibrium bond length ((r{0,ij})) from your existing harmonic force field.

- The bond dissociation energy ((D{ij})) from experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations.

- The width parameter ((\alpha_{ij})), initially set to ~2.1 Å⁻¹ and refined against experimental vibrational spectra. [21]

- Force Field Modification: In your simulation input, replace the harmonic bond potential for the specified atom types with a Morse potential term: (E{\text{bond}} = D{ij} [1 - e^{-\alpha{ij}(r{ij} - r_{0,ij})}]^2).

- Simulation and Validation: Run the simulation with the modified parameters. Validate that the bulk and interfacial properties of the non-reactive parts of the system remain accurate. [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MD Troubleshooting

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [22] [23] | A high-performance MD simulation package. | Used for running simulations, energy minimization, and equilibration in various fields, including drug solubility studies. [22] |

| CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA [21] [23] | Biomolecular force fields. | Provide the foundational parameters for simulating proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. Can be extended with reactive potentials. [21] |

| IFF-R (Reactive INTERFACE FF) [21] | A reactive force field using Morse potentials. | Enables bond breaking in complex materials and biomolecular systems; compatible with several standard force fields. [21] |

| ReaxFF [21] | A reactive bond-order force field. | An alternative method for simulating chemical reactions; generally more computationally expensive than Morse potential approaches. [21] |

| AlphaFold [24] | Protein structure prediction tool. | Provides accurate 3D structural models of protein targets when experimental structures are unavailable, crucial for setting up valid simulations. [24] |

| Machine Learning Models [22] | Predictive analysis of MD properties. | Uses descriptors like SASA and DGSolv to predict properties like solubility, helping to diagnose and anticipate simulation outcomes. [22] |

Force Field Limitations and Their Impact on Minimization Success

Energy minimization is a foundational step in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, essential for relieving steric clashes and preparing a stable system for production runs. The success of this process is intrinsically linked to the choice and parameterization of the molecular mechanics force field. Force fields provide the mathematical framework and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates. Limitations in these force fields—whether due to incomplete parameter sets, inaccurate functional forms, or improper application—can directly lead to minimization failures, including non-convergence, unphysical structures, or catastrophic simulation instability. This guide addresses these critical failure points within the context of academic research, providing troubleshooting methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

FAQs: Addressing Common Force Field and Minimization Issues

Q1: My energy minimization fails with a message that "the forces have not converged" and shows a very high maximum force. What force field-related issues could cause this?

This common error indicates the minimizer cannot find a geometry where the maximum force is below the specified threshold. Force field-related causes often include [25] [2]:

- Missing or Incorrect Parameters: The topology may be missing bond, angle, or dihedral parameters for certain residues or ligands, leading to uncontrolled movement and high forces.

- Steric Clashes from Poor Initial Structure: Incorrect initial structures, often stemming from earlier force field application issues in building (e.g., with

pdb2gmx), can create severe atomic overlaps that the minimizer cannot resolve. - Incompatible Force Fields: Mixing parameters from different force fields (e.g., using a protein from CHARMM and a ligand from AMBER without proper cross-term parameterization) creates internal contradictions in the energy landscape, preventing convergence [25].

- Incorrect Treatment of Terminal Residues: As highlighted in GROMACS documentation, improper naming of N- or C-terminal residues (e.g., using "ALA" instead of "NALA" for the N-terminus in AMBER force fields) leads to missing atoms or incorrect bonding patterns, causing large forces [25].

Q2: During system setup, I get an error that a residue is not found in the residue topology database. How should I proceed?

This pdb2gmx error means the force field you selected does not contain a definition for the specified residue (e.g., a non-standard amino acid or a novel drug molecule) [25]. Your options are:

- Rename the Residue: If the residue is standard but named differently in the force field's database, rename it in your coordinate file [25].

- Use a Different Force Field: Switch to a force field that includes parameters for your residue.

- Manually Provide a Topology: You cannot use

pdb2gmxfor arbitrary molecules. You must create a topology for the residue manually or using other tools (e.g.,x2topor external programs likeACPYPEorPRODRG), and then include it in your system's top file [25]. - Parameterize the Residue: As a last resort, you may need to derive new parameters for the residue yourself, a complex process that requires significant expertise [25].

Q3: My simulation fails with a "segmentation fault" or "non-numeric atom coords - simulation unstable" error during or after minimization. Could this be force field-related?

Yes. While segmentation faults can have computational causes (faulty hardware, compiler issues), they often follow minimization and indicate profound instability, frequently tied to force field problems [2] [26].

- Severe Parameter Inconsistency: The force field parameters may be physically unrealistic for the system, leading to "blowing up" as atoms are propelled with enormous velocities. This is a known risk in reactive force fields like ReaxFF if parameters are inconsistent [27] [26].

- Topology Errors: Incorrect atom ordering, charge assignments, or bonded terms in the topology can generate impossible forces.

- Long-Range Electrostatics Mismanagement: Improper treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions can cause artifacts that destabilize the simulation.

Q4: What are the fundamental limitations of traditional force fields that can affect simulation accuracy?

Traditional, widely-used biomolecular force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA, GROMOS) have inherent limitations that can impact minimization and subsequent dynamics [28] [29]:

- Fixed Atomic Charges: They use atom-centered point charges that do not account for polarization effects—the change in electron distribution due to the chemical environment. This can lead to inaccurate descriptions of interactions in heterogeneous systems like protein-ligand complexes [28].

- Non-Reactive Potentials: They use harmonic potentials for bonds, which cannot describe bond breaking and formation. This limits their application in studying chemical reactions or mechanical failure [29].

- Functional Form: The relatively simple functional form of the potential energy may not fully capture the complexity of quantum mechanical potential energy surfaces, sometimes requiring empirical corrections to compensate [28].

- Training Set Bias: Each force field is derived from a specific training set of molecules and properties, which can introduce a bias and reduce transferability to novel molecular systems [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Workflow

Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and resolve force field-related minimization problems. The diagram below outlines the key decision points.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic and Resolution Procedures

Step 1: Analyze the Error Message and Log File Carefully read the minimization output and log file. Specific warnings before the failure are crucial. Note the value and location of the maximum force, as this points to the problematic atom group [2].

Step 2: Check Topology and Parameter Files

- Diagnostic: Use tools like

gmx pdb2gmx -horgmx grompp -vto check for warnings about missing parameters or duplicate directives. The error "Found a second defaults directive" indicates multiple[defaults]sections in your topology, often from incorrectly includeditpfiles [25]. - Resolution: Ensure the

[defaults]directive appears only once in your main topology file. Comment out extra[defaults]sections in includeditpfiles. For missing parameters, consult the force field's literature or use parameter derivation tools [25].

Step 3: Validate the Initial Structure

- Diagnostic: Look for warnings about "long bonds," "missing atoms," or "atom ... not found in rtp entry" during

pdb2gmxexecution [25]. - Resolution: For missing hydrogens, consider using the

-ignhflag to letpdb2gmxadd them correctly. For missing heavy atoms, you must model them using external software before proceeding [25].

Step 4: Review the Minimization Protocol (mdp Parameters)

- Diagnostic: The minimizer stops but reports an unacceptably high maximum force [2].

- Resolution: The Steepest Descent algorithm, while robust for initial steps, can have slow convergence. As a hybrid approach, start with Steepest Descent to remove severe clashes, then switch to the Conjugate Gradient algorithm for finer convergence [30]. Ensure your

emtol(force tolerance) is realistic (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm for initial minimization, 10-100 for finer minimization). Temporarily increasing theemstep(step size) can also help escape high-energy states.

Step 5: Test with a Simpler System If the complex system fails, isolate the problem. Run minimization on individual components: the protein alone, the ligand alone, and the solvent box alone. This identifies which component's topology or parameters are causing the instability.

Step 6: Verify Force Field Consistency Ensure all components of your system (protein, DNA, ligand, ions, water) are parameterized with the same force field family. Mixing force fields (e.g., AMBER for protein and CHARMM for water) without validated cross-compatibility is a common source of instability [25] [29].

Advanced Topic: Selecting and Evaluating Force Fields

Performance Comparison of Modern DNA Force Fields

Recent assessments of the AMBER force field family for DNA simulations reveal performance variations. The following table summarizes key findings from a 2023 study comparing force fields when paired with different water models [31].

Table: Performance Assessment of Recent AMBER DNA Force Fields (2023)

| Force Field | Recommended Water Model | Performance with B-DNA | Performance with Z-DNA | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL21 | OPC | Excellent, currently recommended | Significantly better than Tumuc1 | Incremental improvement from OL15; refined α/γ dihedrals [31]. |

| Tumuc1 | OPC or TIP3P | Similar to OL21 | Discrepancies observed | Comprehensive reparameterization of bonded terms using QM [31]. |

| bsc1 | TIP3P or SPC/E | Good | Adequate | Includes bsc0 modifications plus refinements to χ, ε, ζ dihedrals [31]. |

| OL15 | TIP3P or SPC/E | Good | Adequate | Predecessor to OL21; includes improvements to β dihedral [31]. |

Experimental Protocol: Force Field Assessment for DNA Systems

The quantitative data in the previous table was generated using the following detailed methodology, which can serve as a template for evaluating force fields in your own research context [31]:

- System Preparation: Start with experimental structures (NMR or high-resolution X-ray crystal structures). Remove crystallographic water and counterions to ensure a clean starting point.

- Solvation and Ion Addition: Solvate the DNA in a truncated octahedron box with a 10 Å buffer using the chosen water model (e.g., TIP3P, OPC). Add net-neutralizing counterions (Na⁺, Cl⁻) using the Joung and Cheatham ion parameters, plus excess salt to achieve a physiological concentration of ~200 mM.

- Equilibration: Perform a multi-step equilibration:

- Hold the solute under strong positional restraints (5 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²) for 1 ns.

- Gradually reduce the restraints (0.5, then 0.1 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²) in successive 1 ns simulations.

- Conclude with a short (1 ns) unrestrained equilibration. Use a 1 fs integration time step during equilibration.

- Production Simulation: Run multiple independent replicas (e.g., 5 per system) for an extended time (microsecond scale) in the NPT ensemble at 300 K. Use Langevin dynamics for temperature control and a barostat for pressure regulation. An integration time step of 4 fs can be enabled by employing hydrogen mass repartitioning.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the aggregated simulation time from all replicas, discarding the initial segment (e.g., first 1000 ns) as additional equilibration. Compare properties like helical parameters, backbone dihedrals, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to experimental data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Resources for Force Field Parameterization and Validation

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Residue Topology Database (RTP) | Defines atom types, connectivity, and bonded interactions for molecular building blocks (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides) [25]. | Essential for pdb2gmx to generate topologies for standard residues. |

| Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) | A method for deriving atomic partial charges by fitting to the quantum mechanically calculated electrostatic potential [28]. | Used in AMBER force fields to assign charges for new molecules. |

| Joung-Cheatham Ion Parameters | Optimized parameters for monovalent ions (Na⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺) for use with specific water models like TIP3P and SPC/E [31]. | Critical for achieving physiological ionic conditions in simulations. |

| Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) | A technique that allows for a larger MD integration time step (4 fs) by redistributing mass from hydrogens to the bonded heavy atoms [31]. | Used to accelerate production simulations after equilibration. |

| Reactive INTERFACE Force Field (IFF-R) | A reactive force field that replaces harmonic bonds with Morse potentials to simulate bond breaking and formation [29]. | Used for simulating chemical reactions, polymer failure, and other reactive processes. |

Force field limitations present significant but surmountable challenges in molecular dynamics minimization. Success hinges on a systematic approach: a thorough understanding of the force field's scope and parameters, careful system construction, and methodical troubleshooting. The field continues to advance with more accurate, polarizable, and reactive force fields. By applying the diagnostics and solutions outlined in this guide, researchers can effectively overcome minimization failures and build a solid foundation for reliable and meaningful molecular dynamics simulations.

Practical Implementation: Algorithm Selection and Parameter Optimization

Algorithm Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the Steepest Descent and L-BFGS algorithms to help you make an informed choice.

| Feature | Steepest Descent | L-BFGS |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Follows the direction of the negative gradient (force) [32]. | Uses gradient and position history to approximate the Hessian (curvature) for a smarter search direction [33]. |

| Convergence Speed | Slow, linear convergence rate [34]. | Fast, superlinear convergence rate near the minimum [35]. |

| Computational Cost per Step | Very low; requires only force calculations [32]. | Low; requires force calculations and vector-vector operations [36] [33]. |

| Memory Usage | Very low (O(1)) [32]. |

Low (O(m*N), where m is memory size) [33]. |

| Robustness | High; guaranteed progress at every step [32] [35]. | Moderate; can fail on very ill-conditioned or non-convex problems without safeguards [35] [37]. |

| Typical Use Case in MD | Initial minimization from poor starting structures, systems with clashes [32] [2]. | Final minimization stages, geometry optimization of stable structures [36] [32]. |

Understanding the Algorithms

Steepest Descent

This is one of the simplest optimization algorithms. It calculates the force (the negative gradient of the potential energy) on each atom and moves the atoms in the direction of the force to lower the energy [32]. The step size is adaptive: it is increased by 20% after a successful step that lowers the energy and drastically reduced by 80% after a step that increases the energy [32]. While this makes it very robust and stable, even from poor starting points, its convergence is slow because it does not use information about the curvature of the energy landscape.

L-BFGS (Limited-Memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno)

L-BFGS is a quasi-Newton method. It significantly improves upon Steepest Descent by using information from the last few steps to build an approximation of the energy landscape's curvature (the inverse Hessian matrix) [33]. This allows it to find better search directions and converge much faster once it's near a minimum. Its "Limited-Memory" nature means it does not store a dense matrix, making it suitable for large systems with thousands of atoms [36] [33].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

My energy minimization stops abruptly without force convergence.

This is a common issue, often encountered with Steepest Descent. The simulation stops because the algorithm can no longer find a step that lowers the energy, even though the forces are still high.

- Problem Analysis: This typically indicates your system is stuck in a very flat region of the energy landscape or on a "ledge" where tiny steps no longer yield progress [2]. The algorithm's adaptive step size becomes so small that it cannot make meaningful progress.

- Solution:

- Switch Algorithms: As suggested in forum discussions, use the output from the failed Steepest Descent run as the input for a more efficient algorithm like L-BFGS or Conjugate Gradient [2]. L-BFGS, with its curvature information, is often better at escaping these flat regions.

- Check System Integrity: Verify your initial structure for unphysical clashes, incorrect bond lengths, or missing parameters that might create insurmountable energy barriers [2].

L-BFGS fails to start or converges poorly after many steps.

- Problem Analysis: L-BFGS relies on the history of steps and gradients. If the initial geometry is pathological or the energy landscape is highly non-convex, the history can contain inconsistent information, leading to a poor search direction [35] [37].

- Solution:

- Use Steepest Descent First: Always use a few dozen steps of Steepest Descent to first relax the worst steric clashes and bring the system to a smoother region of the energy landscape. Then, switch to L-BFGS for efficient convergence [32] [2].

- Ensure Proper Conditioning: The performance of L-BFGS, like other gradient-based methods, can be sensitive to the scaling of different variables. Poor conditioning can lead to slow convergence [34].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational "reagents" for your energy minimization experiments.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Steepest Descent Algorithm | Provides a robust, fall-back minimizer for initial stabilization of poorly configured systems and for overcoming initial steric clashes [32]. |

| L-BFGS Algorithm | The workhorse for efficient, high-precision energy minimization in most production scenarios, offering a good balance of speed and accuracy [36] [32]. |

| Position Restraints | Allows for the selective relaxation of parts of a system (e.g., solvent) while holding critical regions (e.g., protein backbone) fixed, which is a common equilibration protocol [2]. |

| Line Search (e.g., BFGSLineSearch) | An advanced component that determines the optimal step size along a search direction, stabilizing optimization and preventing oscillation [36]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Minimization Workflow

For a typical molecular system (e.g., a protein-DNA complex in solvent), follow this two-stage protocol to ensure robust and efficient minimization [32] [2]:

Initial Robust Minimization with Steepest Descent

- Objective: Remove any severe steric clashes and bring the system to a stable, albeit not fully minimized, state.

- Integrator:

steep - Force Tolerance (

emtol):1000.0kJ/mol/nm (or a similarly loose tolerance) - Maximum Steps (

nsteps):500 - 1000 - This stage is expected to converge to machine precision but not to the desired force tolerance.

High-Precision Minimization with L-BFGS

- Objective: Achieve the desired force convergence for a stable starting configuration for molecular dynamics.

- Integrator:

l-bfgs - Force Tolerance (

emtol):10.0 - 500.0kJ/mol/nm (dependent on your production run requirements) - Maximum Steps (

nsteps):1000 - 5000 - Use the final structure from the Steepest Descent run as the input for this stage.

Decision Workflow for Energy Minimization

The following diagram outlines the logical process for selecting and troubleshooting energy minimization algorithms in your research.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most critical parameters for energy minimization in molecular dynamics?

The most critical parameters are the force tolerance (emtol), the maximum number of iterations (nsteps), and for the steepest descent algorithm, the initial step size (emstep). Proper tuning of these parameters is essential for achieving a stable, minimized system as a prerequisite to molecular dynamics production runs. [5]

2. My minimization fails to converge. What should I check first?

First, verify that your force tolerance (emtol) is set to an appropriate value, typically 100-1000 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹, and that the maximum number of iterations (nsteps) is high enough to allow the convergence to occur. Secondly, for the steepest descent integrator, ensure the initial step size (emstep) is not too large, as this can cause instability. A good starting point is 0.01 nm. [5]

3. How do I know if my energy minimization has been successful?

A successful minimization will terminate when the maximum force in the system falls below the value specified by emtol. The log file will typically state "converged to within the requested tolerance" or similar. You should also observe a steady, significant decrease in the potential energy throughout the process. [5]

4. Should I use steepest descent or conjugate gradient for minimization?

Steepest descent (integrator = steep) is more robust for initially relieving severe steric clashes in a structure, as it is less likely to fail on the first steps. The conjugate gradient algorithm (integrator = cg) is more efficient for later stages of minimization and for achieving a more precise minimum but can be less stable with poorly starting structures. [5]

5. What is the function of the nstcgsteep parameter?

The nstcgsteep parameter specifies how often a steepest descent step is performed when using the conjugate gradient algorithm. Periodically using steepest descent can improve the efficiency and stability of the conjugate gradient minimization. The default in GROMACS is to do this every 1000 steps. [5]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Energy Minimization Fails to Converge

- Symptoms: The minimization hits the maximum number of iterations (

nsteps) without the maximum force dropping below the specified tolerance (emtol). The log file may show that the energy or force is no longer decreasing. - Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Force tolerance is too strict: A very low

emtol(e.g., 1 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹) requires an extremely precise minimum and can take a prohibitively long time to achieve.- Solution: Increase

emtolto a more reasonable value. For a preliminary minimization before a molecular dynamics run, a value of 100-1000 is often sufficient. [5]

- Solution: Increase

- Maximum iterations is too low: The system simply needs more steps to find the minimum.

- Solution: Increase the

nstepsparameter. For large or highly distorted systems, several thousand steps may be necessary.

- Solution: Increase the

- Underlying structural problems: Severe atomic clashes, missing atoms, or incorrect bonds can create forces that cannot be minimized effectively. [12]

- Solution: Inspect your initial structure for anomalies. Check the output of

pdb2gmxfor warnings about missing atoms or long bonds, and correct your input structure accordingly. [12]

- Solution: Inspect your initial structure for anomalies. Check the output of

- Force tolerance is too strict: A very low

Problem: Minimization Becomes Unstable (Crash or Blowing Up)

- Symptoms: The simulation crashes, or the potential energy becomes astronomically high (e.g.,

1e+NaN). - Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Step size is too large: This is a common cause with the steepest descent algorithm. A large initial step can cause atoms to be moved too far, leading to even larger forces and instabilities. [5]

- Solution: Drastically reduce the

emstepparameter. Tryemstep = 0.001nm. Theemstepvalue is also used as the initial step for the first step of conjugate gradient minimization. [5]

- Solution: Drastically reduce the

- Incorrect constraints: Using

constraints = all-bondswith a simple minimization integrator can sometimes cause issues.- Solution: For initial minimization, try using

constraints = noneor use the LINCS constraint algorithm (constraints = h-bondsorconstraints = h-angles). [38]

- Solution: For initial minimization, try using

- Step size is too large: This is a common cause with the steepest descent algorithm. A large initial step can cause atoms to be moved too far, leading to even larger forces and instabilities. [5]

Problem: Minimization is Inefficient (Extremely Slow)

- Symptoms: The energy is decreasing consistently but at a very slow rate, making it impractical to reach the desired tolerance.

- Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Inefficient algorithm for the stage of minimization:

- Solution: Use a hybrid approach. Start with the robust steepest descent algorithm (

integrator = steep) for 50-100 steps to relieve the worst clashes, then switch to the more efficient conjugate gradient (integrator = cg) to refine the structure to the desired tolerance. [5]

- Solution: Use a hybrid approach. Start with the robust steepest descent algorithm (

- Conjugate gradient is stuck:

- Solution: The

nstcgsteepparameter forces a steepest descent step periodically during conjugate gradient minimization, which can help the algorithm escape from shallow regions. Ensure this is enabled (default is every 1000 steps). [5]

- Solution: The

- Inefficient algorithm for the stage of minimization:

Parameter Tables for Energy Minimization

Table 1: Core Energy Minimization Parameters in GROMACS

| Parameter | MDP Option | Description | Typical Values / Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | integrator |

Algorithm used for minimization. [5] | steep (steepest descent), cg (conjugate gradient) [5] |

| Force Tolerance | emtol |

Convergence criterion; minimization stops when the maximum force is below this value. [5] | 10.0 - 1000.0 [kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹] [5] |

| Max Iterations | nsteps |

Maximum number of minimization steps allowed. [5] | 100 - 50000 (system dependent) |

| Initial Step Size | emstep |

Initial step size (in nm) for the steepest descent algorithm. [5] | 0.001 - 0.01 [nm] [5] |

| CG Steepest Desc. Freq. | nstcgsteep |

Frequency of steepest descent steps during conjugate gradient minimization. [5] | 1000 [steps] (default) [5] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide Summary Table

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Suggested Action |

|---|---|---|

| Fails to converge | emtol too low or nsteps too small. [5] |

Increase emtol; increase nsteps. |

| Crashes immediately | Severe steric clashes; emstep too large. [12] [5] |

Check structure for clashes; reduce emstep to 0.001. |

| Energy becomes NaN | Instability from large forces/step size. [5] | Reduce emstep; try a more robust integrator (steep). |

| Extremely slow progress | Inefficient algorithm for the current state. | Use steep first, then switch to cg; check nstcgsteep. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Two-Stage Energy Minimization for a Solvated Protein-Ligand System

This protocol is designed to efficiently minimize a typical system while avoiding instability.

- System Preparation: The system (e.g., protein, ligand, solvated in a water box with ions) is prepared using the standard

gromppcommand to generate a run input file (.tpr). A sample.mdpfile for the first stage is provided below. - Stage 1 - Steepest Descent: Run the first minimization stage using a robust steepest descent algorithm to relieve major atomic clashes.

- MDP Parameters:

integrator = steepemtol = 1000.0nsteps = 500emstep = 0.01

- Execution:

gmx grompp -f stage1.mdp -c system.gro -p topol.top -o min1.tprgmx mdrun -v -deffnm min1

- MDP Parameters:

- Stage 2 - Conjugate Gradient: Use the output from Stage 1 as input for a more precise minimization using the conjugate gradient algorithm.

- MDP Parameters:

integrator = cgemtol = 10.0nsteps = 5000nstcgsteep = 1000

- Execution:

gmx grompp -f stage2.mdp -c min1.gro -p topol.top -o min2.tprgmx mdrun -v -deffnm min2

- MDP Parameters:

- Validation: Check the output of

gmx energyfor the potential energy of themin2run to ensure a steady decrease and final convergence.

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting Severe Steric Clashes

If a system fails the standard protocol with instabilities, this aggressive protocol can be used.

- Ultra-Conservative Steepest Descent:

- MDP Parameters:

integrator = steepemtol = 1000.0nsteps = 100emstep = 0.001# Very small step size for stabilityconstraints = none# Remove constraints to simplify initial minimization

- Run this step and visually inspect the resulting structure. If stable, use its output as input for Protocol 1.

- MDP Parameters:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Analysis Tools

| Item | Function | Source / Command |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package used for energy minimization and production runs. [22] | https://www.gromacs.org |

| pdb2gmx | GROMACS tool to generate topology and coordinates from a PDB file. Critical for preparing the initial system. [12] | gmx pdb2gmx -f protein.pdb -p topol.top -ff forcefield |

| grompp | GROMACS preprocessor. Assembles the .tpr run input file from the .mdp parameters, topology, and coordinates. [12] |

gmx grompp -f min.mdp -c system.gro -p topol.top -o min.tpr |

| mdrun | GROMACS MD engine. Executes the minimization or simulation. [22] | gmx mdrun -v -deffnm min |

| energy | GROMACS analysis tool to extract energy terms (like Potential Energy) from the output file for plotting and validation. | gmx energy -f min.edr -o potential.xvg |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Energy Minimization Troubleshooting Workflow

Relationship Between Key Minimization Parameters

FAQs: Core Parameter Definitions and Selection

Q1: What are the precise definitions of emtol and emstep, and what are their typical units and value ranges?

emtol and emstep are critical parameters that control the convergence and step size in GROMACS energy minimization.

Table 1: Core Energy Minimization Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Units | Typical Value Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

emtol |

The convergence tolerance; minimization stops when the maximum force (Fmax) on any atom falls below this value. |

kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹ | 10 - 1000 (MD prep) [39] [40] [41] | Sets the quality of the minimized structure. |

emstep |

The initial step size for the steepest descent algorithm. | nm | 0.001 - 0.01 [39] [40] | Controls how far atoms move in each step. |

Q2: How do I choose the correct integrator for energy minimization?

The integrator mdp option specifies the algorithm used for minimization. For energy minimization, the primary choices are steep (steepest descent) and cg (conjugate gradient) [5].

steep: A robust steepest descent algorithm. It is less efficient than conjugate gradient but is more stable for poorly structured starting configurations, making it ideal for the initial stages of minimization [5].cg: A conjugate gradient algorithm. It is more efficient than steepest descent once the initial large forces have been reduced, but it may fail if the initial forces are very high [5] [40]. The parameternstcgsteepdetermines how often a steepest descent step is performed during a conjugate gradient minimization to improve stability [5].

Q3: My minimization fails with "forces have not converged to the requested precision." What are the primary causes?

This is a common error indicating that the minimization stopped before the forces reached the desired emtol. The two most frequent underlying causes are:

- Extremely high initial forces: The algorithm cannot reduce the forces to the target

emtolbecause the starting configuration is too unstable [39] [41]. This can be due to atomic overlaps, incorrect topology, or misplaced molecules. - Machine precision limit: The minimization has converged to the lowest energy possible for the given configuration and precision setting, but this is still above the requested tolerance [39] [40]. The message often states it "converged to machine precision."

Troubleshooting Guide: Energy Minimization Failures

Error: Incomplete Convergence and High Forces

Problem Description

The energy minimization run terminates with a warning that the forces have not converged to the requested Fmax < [emtol], despite the Potential Energy (Epot) becoming more negative. The maximum force (Fmax) remains orders of magnitude too high, for example, 1.91991e+05 versus a target of 10 [39].

Diagnosis Methodology This error requires a systematic diagnosis to isolate the root cause. The following workflow outlines the recommended investigative process, from initial checks to advanced solutions.

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting workflow for minimization convergence failures.

Experimental Protocols for Resolution

Protocol A: Two-Stage Minimization with Optimized Parameters This protocol is effective when dealing with severe atomic overlaps or a poor initial structure [42].

- Stage 1 - Coarse Minimization:

- Objective: Quickly relieve severe clashes and high-energy contacts.

- Parameters: Use the

steepintegrator with a relaxedemtolof 100-1000 and a conservativeemstepof 0.001. A higheremtolprevents the algorithm from getting stuck on machine precision for a very bad configuration [39] [40]. - Sample MDP Snippet:

- Stage 2 - Fine Minimization:

Protocol B: Topology and Charge Validation Incorrect system topology or net charge is a major source of high, irresolvable forces [42].

- Validate Residue Topologies: Ensure all molecules (protein, ligand, ions) have correct residue topology (

rtp) entries in the force field database. The errorResidue not found in residue topology databaseindicates a missing entry [43]. - Check Total System Charge: Use

gmx gromppto report the total charge of the system. A large net charge in a periodic system creates infinite electrostatic energy, preventing minimization. Neutralize the system by adding appropriate counter-ions usinggmx genion[42].

Protocol C: Constraint Handling Overly rigid constraints can prevent the system from relaxing properly.

- Action: In the minimization mdp file, set

constraints = none. This allows all atoms, including bond vibrations, to move freely during minimization, which can help resolve clashes [39] [41]. Constraints should be re-enabled for the subsequent equilibration and production runs.

Error: Minimization Stalls with No Energy Change

Problem Description

The minimization stops after very few steps (e.g., 15 steps) with a message that there was "no change in the energy since last step" or that the step size was too small, even though Fmax is still very high [39] [41].

Diagnosis and Solution This typically indicates that the steepest descent algorithm can no longer find a downhill direction given its current step size and the local energy landscape.

Table 2: Advanced MDP Parameters for Stalled Minimization

| Parameter | Function | Recommended Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

emstep |

Initial step size for steepest descent. | Increase cautiously (e.g., to 0.01 or 0.02) to allow the algorithm to escape shallow local minima [40]. |

nstcgsteep |

Frequency of steepest descent steps during CG minimization. | For integrator=cg, setting this (e.g., nstcgsteep = 1000) periodically resets the search direction, improving stability [5] [40]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Energy Minimization Setup

| Reagent / Component | Function | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field (.itp files) | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for all molecules. | Examples: AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36. Must be consistent for all components [44]. |

| Molecular Topology (.top file) | Describes the system composition: atoms, bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions. | Generated via pdb2gmx or manually assembled. Must be error-free [43] [42]. |

| Coordinate File (.gro/.pdb) | Contains the initial 3D atomic coordinates of the system. | Must be structurally sound, with no severe atomic overlaps or missing atoms [43]. |

| Water Model | Solvates the system and provides a realistic environment. | Examples: SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P. Chosen for compatibility with the force field [44]. |

| Ions | Neutralizes the system's net charge and mimics physiological conditions. | Added via gmx genion. Critical for managing electrostatic interactions in Periodic Boundary Conditions [42]. |

FAQs

Q1: Why does my simulation become unstable immediately after adding solvent?

This is often caused by atomic overlaps between the solute and solvent molecules during the insertion process. These overlaps create extremely high potential energy points that the energy minimization cannot resolve, leading to a simulation "crash." To prevent this, ensure you use the correct commands and parameters for solvent addition, such as gmx solvate, which includes algorithms to minimize these overlaps. Always check the final system density after solvation to ensure it is realistic [42].

Q2: How can I tell if my system is properly neutralized, and why is it important?