Solving Molecular Dynamics Equilibration: A Practical Guide to Temperature and Pressure Control for Reliable Simulations

Achieving proper temperature and pressure equilibration in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations is a critical yet often challenging step for obtaining physically meaningful results in biomedical research, particularly in drug development.

Solving Molecular Dynamics Equilibration: A Practical Guide to Temperature and Pressure Control for Reliable Simulations

Abstract

Achieving proper temperature and pressure equilibration in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations is a critical yet often challenging step for obtaining physically meaningful results in biomedical research, particularly in drug development. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists to systematize this process, moving from foundational principles to advanced optimization. We explore the root causes of equilibration failures, evaluate initialization methods and thermostating protocols, and present a troubleshooting guide for common issues. Furthermore, we introduce quantitative validation techniques, including uncertainty quantification and temperature forecasting, to replace heuristic checks with rigorous, criterion-driven termination. By synthesizing recent methodological advances, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of MD simulations for predicting crucial drug properties like solubility and beyond.

Why Equilibration Fails: Understanding the Foundations of Temperature and Pressure Instability

The Critical Role of Equilibration in Physically Meaningful MD Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I be sure my simulation has reached thermal equilibrium?

A1: Thermal equilibrium is reached when the kinetic energy is evenly distributed throughout the system. You can monitor this by:

- Plotting temperatures: Calculate and plot the instantaneous temperature of different system components (e.g., protein, solvent, ions) separately. When these temperatures converge and fluctuate around the same average value, the system is thermally equilibrated [1].

- Monitor energy and RMSD: The total potential and kinetic energy of the system, as well as the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the biomolecule, should reach a stable plateau over time, indicating that the system is no longer drifting [2].

- Use a solvent-coupled protocol: A more physical approach involves coupling only the solvent atoms to the heat bath and monitoring the protein's temperature until it matches the solvent's temperature. This provides a unique measure of when equilibration is complete [1].

Q2: What are the consequences of insufficient equilibration?

A2: Insufficient equilibration can lead to non-equilibrium artifacts that invalidate your simulation results [2]. Specific consequences include:

- Inaccurate property averages: Properties like energy, pressure, and structural metrics will not reflect the true equilibrium state of the system, leading to incorrect conclusions.

- Energy drift: The total energy of the system may show a steady increase or decrease, indicating that the simulation is not stable.

- Unphysical structural divergence: The protein may exhibit unrealistic large-scale structural changes because it started from a non-equilibrated, high-energy state.

Q3: My simulation energy is drifting. What should I check?

A3: An energy drift often points to a problem in the simulation setup or parameters. Focus on these key areas:

- Check the pair-list buffer: In GROMACS, a pair-list buffer that is too small can cause energy drift. Using an automated buffer tuning is recommended [3].

- Review constraint algorithms: Incorrect application of algorithms like SHAKE to constrain bond vibrations can introduce errors. Ensure the constraints are applied consistently [3].

- Verify thermostat/barostat settings: Ensure that the time constants (tau) for temperature and pressure coupling are not too tight, as this can artificially drive system dynamics or suppress natural fluctuations [4] [5].

- Re-examine initial equilibration: Confirm that the system was properly minimized and that the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) equilibration phases were long enough for energies and density to stabilize [5] [6].

Q4: I get the error "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds." What does this mean?

A4: This common error in GROMACS typically occurs when the atom indices in your position restraint file (posre.itp) do not match the actual atom order in the molecule topology [7]. To fix this:

- Check include order: Ensure that the position restraint file for a specific molecule is included immediately after its own

[ moleculetype ]directive in the top-level topology (.top) file. Placing all restraint files at the end of the topology is incorrect [7].- Correct order:

- Regenerate restraints: If the problem persists, try regenerating the position restraint file for the molecule using

pdb2gmxor the appropriate tool.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: System Fails to Reach Target Temperature or Pressure

Problem: During NVT or NPT equilibration, the system temperature or pressure does not converge to the target value.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Step 1: Check Thermostat/Barostat Parameters

- Tau (τ): This coupling time constant determines how strongly the heat bath interacts with the system. A value that is too small can cause overly aggressive coupling and large temperature oscillations. A value that is too large will be ineffective. Common values are in the range of 0.1 - 1.0 ps [4].

- Coupling Groups: For larger systems, consider coupling the protein and solvent to the thermostat separately to account for different heating rates [1].

Step 2: Verify Initial Velocities

- Ensure that initial velocities are generated from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the correct target temperature. Most MD packages can do this automatically [3].

- If restarting from a previous simulation, confirm you are using the final velocities from the equilibration phase, not the beginning.

Step 3: Ensure Proper Energy Minimization

- An un-minimized structure with high-energy clashes can prevent stable equilibration. Always run a thorough energy minimization until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) before starting the heating phase [6].

Issue 2: Simulation Becomes Unstable or "Blows Up"

Problem: The simulation crashes with errors about "constraint failure" or atoms moving excessively.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Step 1: Review the Time Step

Step 2: Check for Steric Clashes

- "Blow-ups" are often caused by severe atomic overlaps introduced during system building (e.g., solvation, ion placement).

- Solution: Go back and run a more robust energy minimization, potentially using a steepest descent algorithm first. You can also use a short simulation with position restraints on the solute and very low time steps (e.g., 0.5 fs) to gently relax the system.

Step 3: Verify Force Field Parameters

- Missing or incorrect parameters for ligands, unusual residues, or ions will cause unphysical forces. Double-check that all molecules in your system have correct and consistent topology definitions [7].

Issue 3: Property Averages Fail to Converge in Production Run

Problem: Even after a long simulation, calculated properties like radius of gyration or side-chain distances continue to drift.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Step 1: Extend Equilibration

- The system may appear thermally equilibrated but might be trapped in a local energy minimum. Continue the NPT equilibration until key structural properties (e.g., density, RMSD) are stable.

- There is no universal rule for equilibration length; it must be determined by monitoring the system [2].

Step 2: Assess Convergence

- Use the following table to monitor key metrics. A system can be considered equilibrated when these metrics stabilize.

| Metric | What it Monitors | Interpretation of Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Total Energy | Stability of the entire system's energy. | Should fluctuate around a stable average value [2]. |

| Temperature | Kinetic energy distribution. | Protein and solvent temps should match and fluctuate around the target [1]. |

| Pressure | Stability of the barostat coupling. | Should fluctuate around the target value (e.g., 1 bar). |

| Density | Proper solvent packing. | For water, should reach ~1000 kg/m³ and be stable [5]. |

| RMSD | Structural stability of the biomolecule. | Should reach a plateau, indicating the structure is not undergoing large drifts [2]. |

- Step 3: Consider Enhanced Sampling

- For systems with slow conformational dynamics (e.g., large domain movements, ligand unbinding), standard MD may be insufficient to sample phase space adequately. If properties related to these slow motions are not converging, you may need to use enhanced sampling techniques (e.g., metadynamics, replica exchange) to accelerate the sampling of rare events [4] [2].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard Multi-Stage Equilibration

This is a typical workflow for equilibrating a solvated protein-ligand system, as implemented in major MD suites like GROMACS, NAMD, and AMBER.

Protocol 2: Solvent-Coupled Thermal Equilibration

This novel protocol, as described in [1], uses the solvent as a more physical heat bath.

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Solvate the protein and minimize the energy with protein atoms fixed.

- Solvent Heating: Couple only the solvent atoms (water and ions) to a thermostat at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K). The protein atoms start at 0 K.

- Monitoring: Calculate the temperature of the protein and the solvent separately during the simulation.

- Criterion for Completion: Thermal equilibrium is defined as the point where the temperature of the protein and the temperature of the solvent become equal and fluctuate around the same average value.

Advantages: This method provides an unambiguous, objective measure of when thermal equilibration is complete, avoiding the heuristic "guesswork" of traditional protocols [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Item | Function / Role | Example Use in MD Equilibration |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for all atoms. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS. Provides the physical model for forces during minimization and dynamics [6]. |

| Water Model | Represents solvent molecules as a set of interacting particles. | TIP3P, SPC/E. Critical for realistic solvation and proper density during NPT equilibration [6]. |

| Thermostat | Algorithm to regulate the system temperature. | Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover, Velocity Rescale. Maintains target temperature during NVT and NPT stages [4] [1]. |

| Barostat | Algorithm to regulate the system pressure. | Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman. Maintains target pressure during NPT equilibration to achieve correct system density [4]. |

| Constraint Algorithm | Freezes the fastest bond vibrations to allow a larger time step. | LINCS (GROMACS), SHAKE (AMBER). Applied to bonds involving H, enabling a 2 fs time step [3] [6]. |

| Analysis Suite | Software for trajectory analysis and property calculation. | GROMACS tools, VMD, MDAnalysis. Used to monitor RMSD, energy, density, and other convergence metrics [1] [2]. |

FAQ: How can I tell if my system has poor thermal equilibration?

The most direct symptom of poor thermal equilibration is significant, sustained fluctuation in the system's temperature and energy readings when they should have stabilized. You should monitor the instantaneous temperature and the total energy (Etot) of the system. In a well-equilibrated simulation, these values will plateau and show stable fluctuations around a constant average value [2] [8].

A more specific diagnostic method involves monitoring the temperature difference between your solute (e.g., a protein) and the solvent (e.g., water). According to a novel procedure, thermal equilibrium is achieved when the separately calculated temperatures of the macromolecule and the surrounding solvent become equal [1]. A persistent difference between these two temperatures is a clear sign that the system has not yet reached a thermally equilibrated state [1].

Quantitative Indicators of Poor Equilibration

| Metric | Well-Equilibrated System | Poorly Equilibrated System |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (TEMP) | Fluctuates around a stable plateau [2] [8] | Shows large, systematic drifts or trends [9] |

| Total Energy (Etot) | Reaches a steady average value [8] | Fails to converge; shows continuous drift [2] |

| Protein vs. Solvent Temp | Temperatures are equal [1] | A significant, persistent difference exists [1] |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) | Fluctuates around a stable value [2] | Fails to converge; shows continuous increase [1] [2] |

FAQ: What are the signs of inadequate density equilibration?

During the constant-pressure (NPT) phase of simulation, the primary signs of inadequate density equilibration are significant drifts in system pressure, volume, and density. These values should also reach a stable plateau. For example, in a properly equilibrated system, the density should stabilize around the expected value for the solvent (e.g., approximately 1.0087 g/cm³ for water) [8]. If the density, pressure, or volume of the simulation box have not converged, the system has not completed the density equilibration phase [8].

Quantitative Indicators of Poor Density Equilibration

| Metric | Well-Equilibrated System | Poorly Equilibrated System |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Fluctuates around the experimental value (e.g., ~1.00 g/cm³ for water) [8] | Shows a consistent drift away from the expected value |

| Pressure (PRESS) | Fluctuates around the target value (e.g., 1 atm) [8] | Shows large, unstable fluctuations or systematic drift [8] |

| Volume | Reaches a stable average value [8] | Does not stabilize; continues to expand or contract |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing Equilibration Issues

Protocol 1: Solvent-Coupling Method for Thermal Equilibration

This protocol provides a less ambiguous method for determining when thermal equilibrium is reached by using the solvent as a heat bath [1].

- System Preparation: Solvate your molecular system (e.g., a protein) and add neutralizing counterions. Perform energy minimization with protein atoms fixed [1].

- Solvent-Only Coupling: During the thermal equilibration phase, couple only the solvent atoms to the thermal bath (e.g., using Berendsen or Langevin methods). Do not directly couple the solute (protein) to the heat bath [1].

- Monitoring: Separately calculate the instantaneous temperatures of both the solute and the solvent throughout the simulation [1].

- Termination Criterion: Thermal equilibrium is achieved when the average temperature of the solute equals the average temperature of the solvent. The length of simulation time required is uniquely defined by this point of convergence [1].

Protocol 2: Standard Multi-Step Equilibration

This is a more traditional protocol involving sequential steps to bring temperature and density to target values [8].

- Heating (NVT Ensemble): Gradually increase the system temperature from 0 K to the target (e.g., 298 K) over a sufficient period (e.g., 30 ps) using a temperature ramp. This is done at constant volume (

ntb=1,ntp=0). Using a ramp helps avoid system instability due to bad atomic contacts [8]. - Density Equilibration (NPT Ensemble): Using the output from the heating stage as a restart, switch to constant-pressure simulation (

ntb=2,ntp=1). Maintain the target temperature and allow the volume of the simulation box to fluctuate until the density stabilizes at the correct value (e.g., ~1.00 g/cm³ for water) [8]. - Analysis: Use tools like Amber's

process_mdout.perlto extract and plot thermodynamic data (TEMP, PRES, DENSITY, ETOT, etc.) over time. Visually inspect these plots to confirm that all properties have reached a plateau before starting production simulations [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, Langevin, Nosé-Hoover) | Gently couples the system to an external heat bath to maintain the target temperature [10]. |

| Barostat (e.g., Berendsen) | Applies pressure scaling to maintain the target pressure during NPT simulations, allowing the box size and density to equilibrate [8]. |

| SHAKE Algorithm | Constrains bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms, permitting the use of a larger MD timestep (e.g., 2 fs) for improved efficiency [1] [8]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Software (e.g., XPLOR, bio3d) | Used to calculate and monitor key properties, such as RMSD, principal components, and separate temperatures for solute and solvent [1]. |

Scripts for Data Triage (e.g., process_mdout.perl) |

Automates the extraction and organization of key thermodynamic data from simulation log files for easier analysis and visualization [8]. |

Troubleshooting Workflow for Equilibration Drift

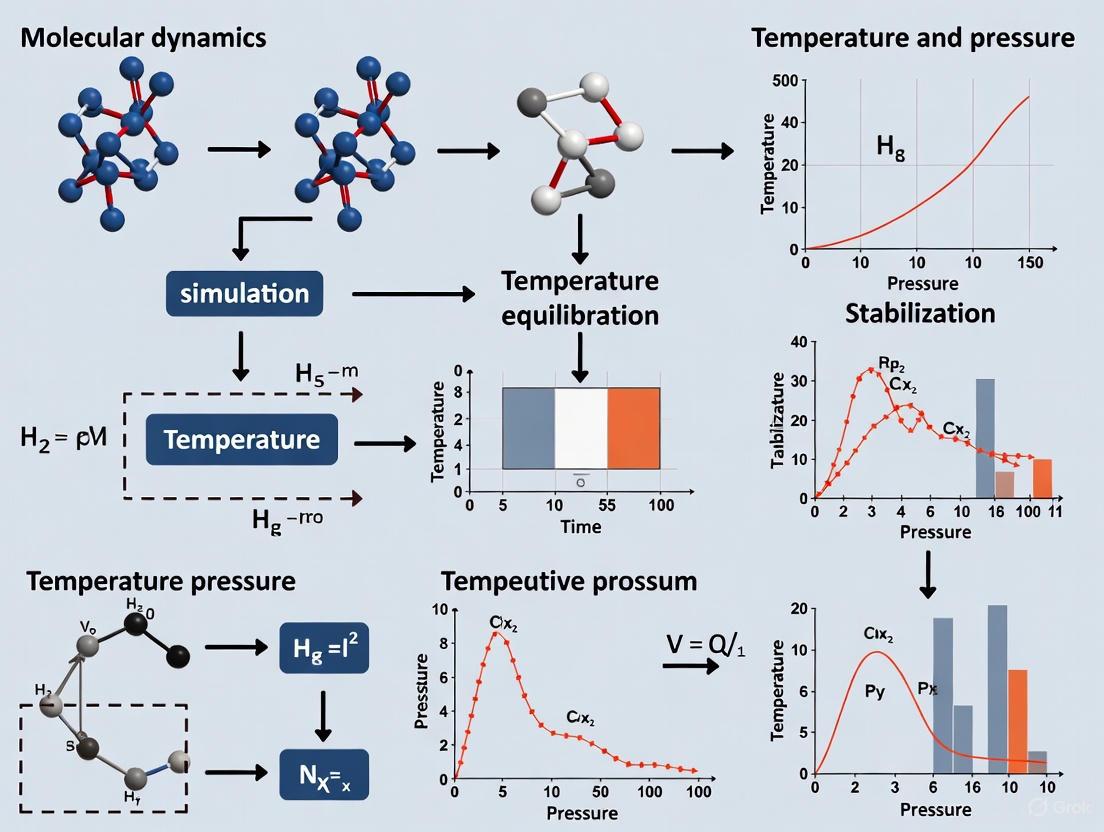

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing common equilibration problems.

Troubleshooting Guide for Equilibration Drift

A Note on Convergence and True Equilibrium

It is critical to understand that "thermal equilibration" in the kinetic sense (the focus of this guide) is different from full "thermodynamic equilibrium" [1] [2]. A system can have its kinetic energy well distributed (be thermally equilibrated) long before it has fully explored its conformational space [1]. Some biologically relevant average properties may converge in multi-microsecond trajectories, while others, like transition rates to rare conformations, may require much more time [2]. Therefore, the convergence of basic metrics like temperature and density is a necessary prerequisite for a stable production simulation, but it does not guarantee that the system is in a complete state of thermodynamic equilibrium [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I be concerned about initial particle placement if my simulation runs without crashing? Even simulations that run technically stable can produce scientifically inaccurate results if started from poor initial conditions. The initial atomic coordinates determine the starting point on the energy landscape. Placement that creates steric clashes or high-energy conformations can trap the system in local energy minima, preventing it from exploring the true equilibrium state. This leads to non-converged properties and unreliable conclusions, even if the simulation appears stable [11].

Q2: My system's Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) has plateaued. Does this guarantee it is equilibrated? No, a flat RMSD curve is a necessary but not sufficient indicator of equilibration. A system can be stuck in a metastable state, showing a stable RMSD while other crucial thermodynamic properties like energy, pressure, or local structural features have not yet stabilized. Effective equilibration requires that multiple, diverse properties—including total energy, density, and specific structural metrics—have all reached a stable plateau [2] [11].

Q3: What is the practical difference between "convergence" and "equilibration" in MD? In practice, these terms are often used interchangeably, but a subtle distinction can be made:

- Equilibration refers to the process where the system loses memory of its initial artificial state and its macroscopic properties (temperature, pressure, energy) stabilize, fluctuating around a steady average [2].

- Convergence typically means that the statistical averages of the properties you are measuring (e.g., diffusion coefficient, binding affinity) do not change significantly as the simulation is extended. A system can be equilibrated (stable in time) but not converged (insufficient sampling for a reliable average) [12].

Q4: How long should I equilibrate my system before starting production? There is no universal timescale for equilibration. The required time depends on the system size, complexity, and the properties of interest. Instead of relying on a fixed time, you should monitor key properties like potential energy, temperature, and density, and only begin production once these values have stabilized and are fluctuating around a steady average [11]. For complex biomolecules, equilibration may require microseconds [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Simulation Results are Strongly Dependent on Initial Coordinates

Symptoms:

- Different simulations of the same system, starting from slightly different initial structures, yield drastically different results.

- The system's properties (e.g., radius of gyration, cluster formation) show a persistent drift even after long simulation times.

- The simulation fails to reproduce known experimental or theoretical data.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Visual Inspection | Visually inspect your initial structure using molecular visualization software (e.g., VMD, PyMOL). Look for unrealistic atomic overlaps, distorted geometries, or incorrect bond lengths. | Rationale: Gross structural errors can introduce enormous potential energy, forcing the system into an unrealistic relaxation path. |

| 2. Energy Minimization | Perform thorough energy minimization until the maximum force is below a reasonable threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm). Use robust algorithms like conjugate gradient if steepest descent fails to converge. | Outcome: The potential energy drops significantly and minimization converges. Rationale: This relieves local strains and steric clashes from the initial structure, providing a stable starting point for dynamics [11]. |

| 3. Multi-Stage Equilibration | Equilibrate in stages. First, apply position restraints on solute atoms and equilibrate the solvent (NVT, then NPT ensembles). Subsequently, remove restraints and allow the entire system to equilibrate. | Rationale: This allows the solvent to relax around the solute, preventing large, destabilizing motions initially and leading to a more physically sound equilibrium state [11]. |

| 4. Validate with Replicas | Run multiple independent simulations starting from different initial velocity distributions or slightly randomized atomic positions. | Outcome: If the results from independent replicas agree, you can be more confident that they are representative and not an artifact of the initial conditions [11]. |

Problem 2: Inconsistent or Unphysical Pressure/Temperature Fluctuations

Symptoms:

- The system pressure or temperature drifts significantly without stabilizing.

- Reported values for properties like diffusion coefficients are orders of magnitude off from expected values.

- The simulated density of a known material is incorrect.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Thermostat/Barostat | Verify that your thermostat and barostat coupling constants are appropriate for your system size and timestep. A constant that is too tight can suppress natural fluctuations, while one too loose will fail to control the ensemble. | Rationale: Inappropriate coupling constants can prevent the system from reaching the correct thermodynamic state or can produce artificial dynamics [11]. |

| 2. Monitor Multiple Properties | During equilibration, plot not just one, but several properties: total energy, potential energy, temperature, pressure, and density. | Outcome: All monitored properties should fluctuate around a stable average. Rationale: Convergence of multiple independent metrics is a stronger indicator of true equilibration than a stable RMSD alone [11]. |

| 3. Ensure Minimization | Confirm that energy minimization converged successfully before beginning the equilibration in the NVT or NPT ensemble. | Rationale: Equilibrating from a high-energy, un-minimized structure can lead to unstable dynamics and failure to regulate temperature and pressure [11]. |

Quantitative Data on Equilibration and Convergence

The table below summarizes key metrics and their expected behavior when a system is properly equilibrated, as identified in the literature.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing MD Equilibration and Convergence [2] [12] [11]

| Metric | Stable State Indicator | Common Pitfalls & Interpretation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total Energy | Fluctuates around a constant mean value. | A drifting baseline indicates the system is not equilibrated. Large, sudden jumps may signal instability. |

| Temperature | Fluctuates around the target value. | The average must match the target. Consistent deviation suggests issues with the thermostat or force field. |

| Pressure | Fluctuates around the target value. | Similar to temperature, the average is key. Large oscillations can indicate poor barostat settings or an undersized system. |

| System Density | Reaches a plateau value consistent with the experimental or theoretical density. | Failure to converge suggests the system is not at the correct state point for production data collection. |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) | Reaches a plateau, indicating the structure is no longer drifting from its initial state. | A plateaued RMSD does not guarantee equilibrium; the system may be trapped in a local minimum [11]. |

| Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF) | Pattern and magnitude of fluctuations become reproducible in independent simulation segments. | Directly related to the Debye-Waller factor (B-factor) from crystallography, useful for validation [11]. |

| Diffusion Coefficient | A plot of the mean-squared displacement (MSD) vs. time becomes linear, confirming normal diffusive behavior. | Sub-diffusive behavior at short times must transition to diffusive; analysis must confirm this transition [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Establishing Equilibration via Property Stabilization

This protocol provides a general method to determine when a system has reached equilibrium.

- System Preparation: Begin with a structurally sound initial model, ensuring correct protonation states and no steric clashes [11].

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the system energy using an algorithm like conjugate gradient until convergence (e.g., maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Initial Equilibration: Run a short simulation with position restraints on heavy atoms of the solute (e.g., protein, DNA) in the NVT ensemble to stabilize the temperature.

- Pressure Coupling: Switch to the NPT ensemble (still with restraints) to adjust the system density to the target pressure.

- Unrestrained Equilibration: Remove all restraints and run an unrestrained NPT simulation.

- Analysis: Calculate the properties listed in Table 1 (energy, temperature, pressure, density, RMSD) as a function of time. The equilibration time (

t_eq) is the point after which all these properties fluctuate around a stable baseline. - Production: Begin the production simulation, discarding the data from

t=0tot=t_eq.

Protocol 2: Assessing Convergence via Multiple Independent Replicas

This protocol checks if observed properties are reproducible and not artifacts of a single trajectory.

- Replica Generation: From the same minimized and pre-equilibrated structure, create at least 3-5 independent simulation replicas by assigning different random seeds for initial velocity generation [11].

- Parallel Execution: Run each replica for the same total simulation time, following the same equilibration and production protocol.

- Comparative Analysis: Calculate the property of interest (e.g., average radius of gyration, end-to-end distance, ligand-binding distance) for each replica.

- Evaluation: Plot the time evolution of the property for all replicas on the same graph. The property is considered converged when the average and fluctuation patterns across all replicas are consistent. Significant divergence between replicas indicates insufficient sampling or a lack of equilibrium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Analysis Tools for MD Equilibration Studies

| Tool / "Reagent" | Primary Function | Application in Equilibration Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Visualizer (VMD, PyMOL) | Visualization of 3D structures and trajectories. | Critical for initial inspection of particle placement, identifying clashes, and visually monitoring conformational changes during equilibration. |

| MD Engine (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS, OpenMM) | Core software that performs the numerical integration of the equations of motion. | Provides the algorithms for minimization, thermostats, barostats, and constrained dynamics. Its parameters must be chosen carefully [14] [11]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suite (MDAnalysis, cpptraj) | Programmatic or script-based analysis of trajectory data. | Used to compute quantitative metrics like RMSD, RMSF, energy, density, and diffusion properties from the simulation output. |

| Force Field (CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS) | A parameterized set of equations describing the potential energy of the system. | Determines the physical forces between atoms. Selection of an appropriate, modern force field is critical for realistic dynamics and convergence [11]. |

Workflow Diagrams for Equilibration and Convergence Analysis

The following diagrams outline the logical workflow for standard equilibration protocols and for diagnosing convergence issues related to initial conditions.

Standard MD Equilibration Protocol

Diagnosing Initial Condition Problems

Core Concepts: The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

What is the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and why is it fundamental to MD simulations?

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is a probability distribution that describes the speeds of particles in an idealized gas at thermodynamic equilibrium. In molecular dynamics simulations, it provides the statistical foundation for initializing particle velocities, ensuring our simulations start from a physically realistic state. The distribution arises from kinetic theory and applies to systems that have reached thermal equilibrium.

For a three-dimensional system, the probability density function for particle speeds is given by:

[ f(v) = \left( \frac{m}{2\pi kB T} \right)^{3/2} 4\pi v^2 \exp\left(-\frac{mv^2}{2kB T}\right) ]

where:

- ( v ) is the particle speed

- ( m ) is the particle mass

- ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant

- ( T ) is the absolute temperature

This distribution emerges naturally in MD simulations of non-interacting, non-relativistic classical particles in thermodynamic equilibrium, and forms the basis for initial velocity generation in most MD packages [15].

How does the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution relate to system temperature?

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is directly parameterized by temperature. When we initialize velocities according to this distribution, we are essentially ensuring that the initial kinetic energy of the system corresponds to the desired simulation temperature. The distribution has several important characteristic speeds that relate to temperature [16]:

Table 1: Characteristic Speeds from the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

| Speed Type | Mathematical Expression | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Most probable speed | ( v{mp} = \sqrt{\frac{2kB T}{m}} ) | Maximum of the distribution curve |

| Average speed | ( v{avg} = \sqrt{\frac{8kB T}{\pi m}} ) | Arithmetic mean of all speeds |

| Root-mean-square speed | ( v{rms} = \sqrt{\frac{3kB T}{m}} ) | Square root of the average squared speed |

These speeds always maintain the relationship: ( v{mp} < v{avg} < v_{rms} ) for any given temperature [16]. The width and shape of the distribution are entirely determined by the temperature and particle mass, with higher temperatures resulting in broader distributions and higher average speeds.

Implementation in MD Simulations

How do MD packages implement Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity initialization?

Most molecular dynamics software, including GROMACS, CP2K, and AMS, generate initial velocities following the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. The implementation typically involves these steps [17] [18]:

Component generation: For each particle, three independent velocity components (vx, vy, vz) are generated as normal distributions with zero mean and standard deviation ( \sqrt{k_B T/m} ).

Momentum removal: The total center-of-mass motion is set to zero to prevent overall drift of the system.

Temperature scaling: Velocities are scaled so that the total kinetic energy corresponds exactly to the desired temperature.

In GROMACS, for example, normally distributed random numbers are generated by adding twelve random numbers Rk in the range 0 ≤ Rk < 1 and subtracting 6.0, then multiplying by the standard deviation of the velocity distribution ( \sqrt{kT/m_i} ) [17].

The following diagram illustrates the complete velocity initialization workflow in typical MD packages:

What are the key mathematical considerations for different system dimensions?

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution differs significantly based on the dimensionality of the system. While most production MD simulations operate in three dimensions, some educational or simplified simulations may use two-dimensional systems.

Table 2: Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution Across Dimensions

| Dimension | Probability Density Function | Most Probable Speed |

|---|---|---|

| 2D | ( f(v) = \frac{mv}{kB T} \exp\left(-\frac{mv^2}{2kB T}\right) ) | ( \sqrt{\frac{k_B T}{m}} ) |

| 3D | ( f(v) = \left( \frac{m}{2\pi kB T} \right)^{3/2} 4\pi v^2 \exp\left(-\frac{mv^2}{2kB T}\right) ) | ( \sqrt{\frac{2k_B T}{m}} ) |

In two-dimensional systems, the distribution has a different functional form, as shown in the table above [19]. This is important to recognize when working with simplified or educational MD codes that might operate in 2D for computational efficiency or visualization clarity.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Why does my system show large temperature fluctuations after initialization?

Significant temperature fluctuations following velocity initialization typically indicate one of several issues:

Small system size: Temperature fluctuations are proportional to ( 1/\sqrt{N} ), where N is the number of atoms [9]. For systems with fewer than 1000 atoms, fluctuations of 5-10% are normal and expected.

Inadequate equilibration: The system may require additional equilibration time to properly distribute energy across all degrees of freedom.

Incorrect thermostat configuration: As identified in CP2K simulations, using the "REGION GLOBAL" thermostat setting couples only 1-3 degrees of freedom to the thermostat, whereas "REGION MASSIVE" couples 3 degrees of freedom per atom, leading to faster equipartition and more stable temperature [9].

Insufficient simulation time: The system may not have been allowed enough time to reach true equilibrium after initialization.

For a 76-atom system, as mentioned in one case study, temperature fluctuations are expected to be substantial due to the small system size alone [9].

How can I verify that my velocity initialization is correct?

To validate your velocity initialization, several diagnostic approaches are recommended:

Speed distribution analysis: Collect particle speeds during the early simulation stages and compare them to the theoretical Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for your target temperature.

Kinetic energy monitoring: Track the kinetic energy and ensure it fluctuates around the expected value of ( \frac{3}{2}Nk_BT ) for a 3D system.

Velocity autocorrelation: Check that velocities decorrelate properly over time, indicating realistic dynamics.

The following Python code snippet demonstrates how to verify the speed distribution in a simple MD simulation [19]:

Advanced Considerations & Best Practices

What are the limitations of Maxwell-Boltzmann initialization for non-ideal systems?

While the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is appropriate for most classical MD simulations, several scenarios require alternative approaches:

Non-equilibrium systems: When studying systems intentionally prepared far from equilibrium, alternative distributions may be more appropriate.

Quantum systems: At low temperatures or for light atoms, quantum effects become significant, and classical statistics may not apply.

Specialized ensembles: Some advanced sampling techniques require modified initial distributions.

Non-thermal initial conditions: For studies of radiation damage or other non-thermal processes, the initial velocities may need to reflect specific experimental conditions.

In these cases, the standard Maxwell-Boltzmann approach should be modified or replaced with distribution functions appropriate to the specific physical context.

How does velocity initialization affect subsequent equilibration?

Proper velocity initialization significantly impacts the efficiency of system equilibration:

Reduced equilibration time: Starting with physically realistic velocities can reduce equilibration time by 20-50% compared to starting from zero velocities or uniform distributions.

Improved stability: Correctly initialized systems typically show more stable thermodynamic properties throughout the simulation.

Minimized artifacts: Proper initialization helps avoid unphysical transient behaviors that can occur when the system abruptly adjusts from artificial initial conditions.

For production simulations, it's often beneficial to run a short (10-20 ps) equilibration phase even after proper velocity initialization to allow the system to fully adjust to the force field and establish proper structural correlations.

Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Velocity Initialization

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS mdrun | MD engine with MB velocity initialization | Uses Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with automatic momentum removal [17] |

| CP2K FIST/MD | MD module for complex systems | Supports various thermostats; REGION MASSIVE recommended for fast equilibration [9] |

| AMS NVEJob | Python API for MD simulations | temperature parameter auto-initializes velocities with MB distribution [18] |

| Custom MB Sampler | Specialized initialization code | NumPy implementation: np.random.normal(0, np.sqrt(kT/mass)) for each component |

| Velocity Verifier | Distribution validation tool | Compares simulated speed histogram to theoretical MB curve [19] |

| Thermostat Coupler | Temperature control | Critical for maintaining desired temperature after MB initialization |

Frequently Asked Questions

My temperature deviates significantly from the target after initialization. What should I check?

First, verify that you're calculating temperature correctly using ( T = \frac{2\langle Ek \rangle}{3NkB} ) for a 3D system. Common issues include:

Incorrect degree of freedom count: Ensure you're accounting for constrained degrees of freedom (e.g., from bond constraints) in your temperature calculation.

Unit inconsistencies: Check that all quantities (mass, velocity, kB) are in consistent units.

Implementation error: Verify that your velocity generation uses the correct standard deviation ( \sqrt{k_B T / m} ) for each atom type.

How do I handle velocity initialization for systems with multiple atom types?

For systems with multiple atom types (different masses), you must generate velocities for each atom with the appropriate mass-dependent standard deviation:

This ensures that all atom types have the same average kinetic energy at the target temperature, satisfying the equipartition theorem.

Can I use Maxwell-Boltzmann initialization for non-equilibrium MD simulations?

Yes, Maxwell-Boltzmann initialization is appropriate as a starting point for many non-equilibrium MD simulations, provided that:

- The initial equilibrium state is physically relevant to your study

- The subsequent non-equilibrium perturbation is applied correctly

- You allow for adequate equilibration before applying perturbations

For studies of systems with inherent non-equilibrium conditions (like shear flows or temperature gradients), specialized initial conditions may be more appropriate.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is energy drift and why is it a problem in molecular dynamics simulations? Energy drift refers to the gradual change in the total energy of a closed system over time in computer simulations. According to the laws of mechanics, the energy should be a constant of motion in a closed system, but in molecular dynamics simulations, the energy can fluctuate and increase or decrease over long time scales due to numerical integration artifacts. This is problematic because it indicates non-conservation of energy, which can compromise the physical validity of your simulation results and their reliability for scientific conclusions [20].

2. My simulation "blew up" with LINCS warnings during NPT equilibration. What went wrong? This is a common issue often related to incorrect simulation parameters rather than software bugs. Based on user reports, the problem can frequently be traced to:

- Incorrect compressibility settings: Using the wrong isothermal compressibility value for your solvent (e.g., 1.05e-2 instead of 4.5e-5 for water) can cause instability [21].

- Insufficient equilibration: The NVT phase may need to be run longer before proceeding to NPT [21].

- System preparation issues: Inadequate energy minimization or initial structural problems can manifest during equilibration [21].

3. Why do I see "broken bonds" when visualizing my simulation, and are they real? In most cases, what appears as "broken bonds" in visualization software like VMD is actually a visualization artifact rather than true bond breaking. Since bonds are typically constrained in molecular dynamics simulations, they cannot actually break in classical force fields. The visual discrepancy occurs because visualization tools connect atoms based on proximity rather than the actual bond constraints used in the simulation [21].

4. How can I determine if my energy drift is acceptable for my system? Energy drift should be measured as a rate of absolute deviation after the system has equilibrated, not during equilibration. The metric is typically system-size dependent, with drifts often reported per atom or degree of freedom. While there's no universal threshold, significant drift (e.g., 7% over 50,000 steps) generally indicates potential problems with integration accuracy or force calculation [22].

5. What is the impact of timestep on energy drift and simulation accuracy? Recent research demonstrates a strong correlation between increasing timestep and energy drift. Studies comparing timesteps from 0.5 to 4 fs show that while 2 fs timesteps with hydrogen mass repartitioning (HMR) and SHAKE maintain reasonable accuracy, 4 fs timesteps can cause deviations up to 3 kcal/mol in alchemical free energy calculations. For accurate results, a maximum timestep of 2 fs is recommended when using HMR and SHAKE [23].

Quantitative Analysis of Energy Drift Factors

Table 1: Impact of Timestep on Energy Drift and Simulation Accuracy

| Timestep (fs) | Energy Drift | Accuracy in AFE Calculations | Stability without SHAKE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | Low | High accuracy | Stable |

| 1.0 | Moderate | High accuracy | Mostly stable |

| 2.0 | Noticeable | Good accuracy | Borderline |

| 4.0 | High | Deviations up to 3 kcal/mol | Unstable |

Table 2: Common Parameter Errors and Their Effects

| Incorrect Parameter | Typical Error | Consequence | Correct Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal compressibility | 1.05e-2 for chloroform | System instability | ~1e-4 bar⁻¹ |

| Timestep with HMR | 4 fs | Significant energy drift | 2 fs recommended |

| Constraint algorithm | Missing LINCS | Bond instability | LINCS with appropriate iterations |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Energy Drift Issues

Follow this systematic approach to identify and resolve energy drift problems in your molecular dynamics simulations:

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol

1. Timestep Validation

- Reduce timestep to 1 fs or lower as a test

- For systems with hydrogen mass repartitioning, do not exceed 2 fs timesteps

- Monitor if energy drift decreases with smaller timesteps [23]

2. Integration Scheme Check

- Verify use of symplectic integrators (e.g., Verlet) rather than non-symplectic ones (e.g., Runge-Kutta)

- Understand that symplectic integrators conserve a "shadow Hamiltonian" rather than the true Hamiltonian [20]

3. Force Calculation Audit

- Examine electrostatic treatment: Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) versus cutoff methods

- Check for sufficient smoothing at cutoff boundaries

- Validate long-range interaction parameters [20] [24]

4. Thermostat and Barostat Configuration

- Confirm appropriate coupling constants (taut, taup)

- For charged systems like lipopolysaccharides, implement stepwise thermalization (NVT before NPT)

- Use C-rescale barostat rather than Berendsen for production simulations [24] [21]

5. System Preparation Review

- Ensure sufficient energy minimization before dynamics

- Verify initial structure quality and absence of steric clashes

- For complex systems like glycolipids, use progressive equilibration protocols [24]

Experimental Protocols for Energy Drift Assessment

Protocol 1: Timestep Optimization for Minimal Drift

Objective: Determine the maximum stable timestep for your specific system while maintaining acceptable energy drift.

Methodology:

- Prepare your system with standard energy minimization

- Run a series of short NVE simulations (50-100 ps) with different timesteps (0.5, 1, 2, 4 fs)

- Use the same initial configuration for all simulations

- Calculate energy drift as:

drift = (E_final - E_initial) / (number_of_atoms * number_of_steps) - Plot energy drift versus timestep to identify the stability threshold [23]

Expected Outcomes: You should observe increasing energy drift with larger timesteps. Select the largest timestep where drift remains below your acceptable threshold.

Protocol 2: Equilibration Quality Assessment for Charged Systems

Objective: Ensure proper equilibration of charged biomolecules like lipopolysaccharides to prevent artifactual energy drift.

Methodology:

- Implement a stepwise thermalization protocol: NVT (100K) → NVT (200K) → NPT (300K)

- Use shorter timesteps (1 fs) during initial equilibration phases

- Apply position restraints to heavy atoms, gradually releasing them

- Monitor box dimensions for sudden expansions indicating instability

- Check for water molecules trickling into hydrophobic regions [24]

Key Parameters:

- NVT duration: 100-500 ps depending on system size

- Temperature coupling: V-rescale or Nose-Hoover

- Pressure coupling: Parrinello-Rahman or C-rescale

- Restraint forces: Gradually reduced from 1000 to 0 kJ/mol/nm²

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Critical Tools for Energy Drift Diagnosis and Resolution

| Tool/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Verlet Integrator | Symplectic integration | Minimizes long-term energy drift compared to non-symplectic methods [20] |

| Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) | Allows longer timesteps | Permits 2-4 fs timesteps while maintaining stability [23] |

| LINCS Algorithm | Constraint satisfaction | Prevents bond stretching instability, essential for longer timesteps [21] |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | Electrostatic treatment | Reduces artifacts from electrostatic cutoffs that contribute to energy drift [20] |

| Stepwise Thermalization | Gradual system equilibration | Prevents "leaky membrane" effect in charged systems like glycolipids [24] |

| C-rescale Barostat | Pressure coupling | Provides better stability than Berendsen barostat for production simulations [21] |

Advanced Diagnostic Techniques

Energy Drift Root Cause Analysis

For persistent energy drift issues, implement this comprehensive diagnostic workflow:

Implementation Notes:

- Force Field Validation: Cross-check parameters with established literature values, paying special attention to partial charges and bonded terms [7]

- Constraint Analysis: Verify that all bonds involving hydrogens are properly constrained and that LINCS parameters (iterations, order) are appropriately set [21]

- Numerical Precision Assessment: Run comparative tests in single versus double precision to identify precision-sensitive operations [22]

Special Considerations for Complex Biomolecular Systems

Charged Glycolipids and Membranes:

- Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) membranes are particularly sensitive to equilibration protocols due to their highly charged nature

- The "leaky membrane effect" (water penetration into hydrophobic regions) can result from improper equilibration and contribute to energy drift

- Recommended approach: Always use a stepwise NVT/NPT protocol rather than NPT-only equilibration [24]

Protein-Ligand Systems:

- Ensure proper parameterization of non-standard residues and ligands

- Validate protonation states at simulation pH

- Use enhanced sampling techniques for insufficient sampling rather than increasing timestep excessively [7]

Equilibration in Practice: Protocols, Thermostats, and Barostats for Robust Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the initial configuration of atoms so critical in molecular dynamics simulations? The initial configuration directly impacts how quickly your system reaches true thermodynamic equilibrium. A poor initial guess can lead to prolonged equilibration times, unstable simulations, or failure to sample the correct physical state. Choosing a method that closely resembles the expected final structure can significantly reduce the computational cost of equilibration [25].

2. My simulation has large pressure fluctuations. Does this mean it has not equilibrated? Not necessarily. Large instantaneous pressure fluctuations are normal, especially in nanoscale simulations of condensed systems like water, due to the low compressibility of liquids [26]. The system can be considered equilibrated when the average pressure over time stabilizes at the target value. For a 2 nm cubic box of water, fluctuations of ±500 bar around the mean can be statistically reasonable [26].

3. What is a more reliable indicator of system equilibration than energy or density? While potential energy and density often stabilize quickly, they can be insufficient to prove full equilibration [27]. The convergence of the Radial Distribution Function (RDF), particularly for key interacting components like asphaltene-asphaltene in complex systems, is a more robust indicator of structural equilibrium [27]. Pressure also typically takes much longer to converge than energy or density [27].

4. Should I use the NVT or NPT ensemble for equilibration? A common and effective protocol is to perform equilibration in stages:

- First, use the NPT ensemble to allow the system's density and box vectors to adjust to the target temperature and pressure, achieving the correct equilibrium density [28].

- Then, switch to the NVT ensemble for production dynamics, using the average box size from the NPT equilibration. This ensures the solvent molecules are well-equilibrated and the system samples configurations at the correct density [28].

5. How does the thermostat choice affect equilibration speed and quality? The thermostat algorithm controls how temperature is maintained and can influence both how quickly the system equilibrates and the quality of the resulting ensemble.

- For fast relaxation toward a target temperature, the Berendsen thermostat is robust and converges predictably, but it does not generate a correct thermodynamic ensemble and should be avoided for production simulations [29].

- For correct sampling of the canonical (NVT) ensemble, the Nosé-Hoover thermostat or Bussi stochastic velocity rescaling are better choices, though they may take longer to converge [29]. Weaker coupling strengths for these thermostats generally require fewer equilibration cycles [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow or Failed Equilibration

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Energy, density, or pressure does not stabilize | Poor initial atomic configuration causing high local energy/repulsion | Switch from a uniform random placement to a physics-informed method like a perturbed lattice [25]. Always perform energy minimization before dynamics. |

| Slow convergence of structural properties (e.g., RDF) | System is glassy or has high-energy barriers; temperature may be too low | Increase the simulation temperature to accelerate dynamics [27]. For solids, ensure the initial lattice matches the expected crystal structure. |

| Large drift in average pressure | NPT simulation is too short; barostat coupling may be too strong | Extend simulation time as pressure converges much slower than energy [27]. Use a weaker coupling (larger tau_p parameter) for the barostat. |

Problem: Unphysical Simulation Behavior

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Extremely large pressure fluctuations (100s of bar) | This may be normal for small system sizes [26]. | Calculate the running average of the pressure. If the average converges to the target, the fluctuations are likely statistical and not a problem. Increase system size to reduce fluctuation magnitude. |

| "Vacuum bubbles" or voids forming in the simulation box | Initial density was set too low [26]. | Restart the simulation with a higher initial density. Use a more compact initial structure or a longer NPT equilibration to slowly compress the system. |

| Hot solvent and cold solute during NVT simulation | Slow heat transfer in the system when using a global thermostat [29]. | Use a local thermostat that controls the temperature of the solute and solvent independently, or allow for a much longer equilibration time for the system. |

Initialization Methodologies for MD Simulations

The choice of initialization method has a quantified impact on equilibration efficiency. Research evaluating seven approaches demonstrates that the best method can depend on the system's coupling strength [25].

The table below summarizes key initialization methods and their characteristics:

| Method | Description | Best Use Case | Performance & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Random | Atoms placed randomly in simulation box [25]. | Simple fluids, initial system generation. | Can cause high initial repulsion; inefficient at high coupling strengths [25]. |

| Uniform Random with Rejection | Random placement with minimum distance criteria [25]. | Avoiding extreme atomic overlaps. | Improved over pure random but may still be suboptimal. |

| Low-Discrepancy Sequences (Halton, Sobol) | Uses mathematically deterministic, uniform point sets [25]. | Providing more uniform sampling than pure random. | More efficient sampling than random methods. |

| Perfect Lattice | Atoms placed on ideal crystal lattice points [25]. | Ordered solids, crystal simulations. | A physics-informed starting point for crystalline materials. |

| Perturbed Lattice | Atoms randomly displaced from a perfect lattice [25]. | Solids, dense liquids, melting studies. | Physics-informed; superior performance at high coupling strengths [25]. |

| Monte Carlo Pair Distribution | Uses Monte Carlo to match a target radial distribution [25]. | Complex liquids where target structure is known. | A sophisticated physics-informed method that can greatly reduce equilibration time. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Equilibration Procedure

- System Building: Construct your initial model with all molecules in a large box with low initial density to ensure a random distribution and avoid local energy concentrations [27].

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to eliminate any unrealistically high repulsive forces that exist in the initial configuration, preventing simulation instability [27].

- Equilibration in NPT Ensemble: Run a simulation in the NPT ensemble.

- Goal: Allow the system's density and box size to adjust to the target temperature and pressure.

- Thermostat/Barostat: Use a robust scheme like the Berendsen thermostat/barostat for this initial relaxation [29].

- Duration: Run until density stabilizes and the average pressure converges to the target value. Monitor the potential energy and RDF for key interactions for further verification [27].

- Production in NVT Ensemble: Using the final box size from the NPT equilibration, run a production simulation in the NVT ensemble with a thermostat that generates a correct thermodynamic ensemble, such as Nosé-Hoover or Bussi stochastic velocity rescaling [29] [28].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-stage equilibration protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | Parametrically solve complex equations like the Boltzmann equation for freeze-in dark matter in alternative cosmologies, helping to determine physical attributes from experimental data [30]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Serve as a bridge between electronic structure calculations and multiscale modeling, enabling large-scale molecular dynamics simulations with DFT-level accuracy but much higher efficiency [31]. Examples include the EMFF-2025 model for energetic materials. |

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | A key analytical tool used to study intermolecular interactions and nanoscale structural characteristics. The convergence of RDF curves, especially for key components like asphaltenes, is a critical indicator of system equilibrium [27]. |

| Berendsen Thermostat | A weak-coupling thermostat known for its predictable convergence and robustness. It is highly useful for the initial relaxation and heating/cooling stages of a simulation but should not be used for production runs as it does not produce a correct thermodynamic ensemble [29]. |

| Nosé-Hoover Thermostat | An extended system thermostat that provides correct sampling of the canonical (NVT) ensemble without involving random numbers, making it suitable for studying kinetics and diffusion properties [29]. |

Your Thermostat Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the core operating principles, key features, and recommended use cases for the Berendsen, Langevin, and Nose-Hoover thermostats to help you make an informed choice.

| Thermostat | Operating Principle | Key Features & Parameters | Statistical Ensemble | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen [32] [33] | Weak coupling to an external heat bath; scales velocities to minimize difference between instantaneous and target temperature. [33] | Parameter: Coupling time constant (τ). [34]Pros: Very stable and efficient for equilibration. [32] [33]Cons: Does not generate a correct canonical ensemble; suppresses legitimate temperature fluctuations. [34] [33] | Does not sample the exact NPT ensemble. [34] | Equilibration only. Fast initial heating and equilibration of a system before switching to a different thermostat for production runs. [34] |

| Langevin [32] [33] | Stochastic dynamics; applies a friction force and a random force to particles. [33] | Parameters: Damping coefficient (γ) or friction. [32] [35]Pros: Good for free energy calculations; enhances conformational sampling. [32]Cons: Introduces random noise, so trajectories do not follow Newton's equations. [32] | Generates a canonical ensemble. [33] | Production runs, especially for systems requiring enhanced sampling or where physical trajectory continuity is less critical. [32] |

| Nose-Hoover [32] [33] | Extended system; introduces a fictitious thermal reservoir particle coupled to the system. [32] [33] | Parameter: Fictitious mass of the thermostat particle (Q). [33]Pros: Generates an exact canonical distribution; time-reversible. [33]Cons: Can be less stable for small or poorly equilibrated systems; requires careful parameterization of Q. [33] | Generates the exact canonical ensemble. [33] | Production runs for accurate thermodynamic sampling once the system is reasonably equilibrated. [32] |

Troubleshooting Common Thermostat Problems

FAQ 1: Why is my system's temperature unstable even with a thermostat applied?

Several factors can cause temperature instability:

- Poor Initial Configuration: If particles are initialized too close together (e.g., using a simple uniform random placement), large repulsive forces can inject a massive amount of energy into the system, leading to significant temperature spikes and prolonged equilibration times. [36]

- Incorrect Thermostat Parameters: The stability of the Nose-Hoover thermostat is highly dependent on the fictitious mass parameter (Q). A poorly chosen value can lead to temperature oscillations and numerical instability. [33] For the Langevin thermostat, a damping coefficient that is too high can overly restrict atom motion. [35]

- Small System Size: In the thermodynamic limit, temperature fluctuations are small. However, for very small systems (e.g., only a few particles), the instantaneous kinetic temperature naturally exhibits large fluctuations, scaling with

1/sqrt(N). A thermostat will correct the average temperature, but you should expect to see larger oscillations in a small system. [37]

FAQ 2: How do I choose a damping coefficient or coupling constant for my thermostat?

There are no universal values, but the following guidelines apply:

- Langevin Damping (γ): This parameter determines the friction atoms experience. A higher value leads to more "sticky" dynamics. This choice can dramatically affect dynamic properties like the diffusion coefficient. [35] For example, in a simulation of TIP3P water, a damping coefficient of 5/ps was found to best reproduce the experimental diffusion coefficient of water. [35] Choose a value that balances efficient temperature control with the desired physical dynamics of your system.

- Berendsen / Nose-Hoover Coupling Time Constant (τ): This parameter determines how aggressively the thermostat corrects deviations from the target temperature. A small τ value results in tight coupling and rapid correction, but can artificially suppress natural fluctuations. A large τ value provides weaker coupling, allowing for more natural fluctuations but slower equilibration. Research suggests that weaker thermostat coupling generally requires fewer equilibration cycles. [36]

FAQ 3: My NPT simulation has huge pressure fluctuations. Is this normal?

Like temperature, pressure fluctuations are inherent to the statistical ensemble. Their magnitude is inversely related to system size. For a very small simulation box, instantaneous pressure values can swing to very high positive or negative values, which is consistent with statistical mechanics. [38] If the fluctuations are unmanageably large, consider:

- Increasing system size.

- Adjusting barostat parameters, such as increasing the time constant for the Berendsen barostat or the piston mass for the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, to provide more damping. [34] Rapid changes in system size due to large pressure differences can crash the simulation. [34]

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Robust Equilibration Workflow

A systematic equilibration protocol is crucial for reliable production data.

- Initialization: Use a physics-informed initial configuration. For dense liquids or solids, a perturbed lattice is often better than purely random placement, as it minimizes extreme forces. [36]

- Energy Minimization: Perform an energy minimization on the initial structure to remove any bad contacts and avoid a "crash" in the first MD step.

- Equilibration with Berendsen: Start with an NVT simulation using the Berendsen thermostat with a moderate coupling constant (e.g., 0.1-1 ps) to rapidly bring the system to the target temperature. [35]

- Production with a Deterministic Thermostat: Switch to an NVT production simulation using the Nose-Hoover thermostat (or Nose-Hoover chains for better stability) for correct ensemble sampling. [32] [33]

- Pressure Equilibration (if needed): For NPT simulations, introduce a barostat only after the temperature has stabilized. Research indicates that an OFF-ON sequence for the thermostat (turning it off for a short time after initialization, then on) can outperform a constant-ON approach for some initialization methods. [36]

Protocol 2: Verifying Thermostat Performance

To confirm your thermostat is working correctly:

- Check Velocity Distribution: For a correctly thermostatted classical system, the particle velocities should follow the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for the target temperature. [33]

- Monitor Running Average: Plot the instantaneous temperature and its running average. A stable running average around the target value indicates successful thermalization.

- Use Conserved Quantity (for Nose-Hoover): In Nose-Hoover dynamics, the extended system energy (Eext) is a conserved quantity. Monitoring the drift of Eext is a excellent check for the stability and accuracy of the integration. [33]

Thermostat Selection and Workflow

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for selecting and applying thermostats in your molecular dynamics simulations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Method | Function in MD Simulation |

|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet Integrator [33] | The fundamental algorithm for integrating Newton's equations of motion, updating particle positions and velocities over time. |

| RESPA (Multiple-Time-Step Integrator) [33] | Increases simulation efficiency by calculating fast-varying forces (e.g., bond vibrations) with a short time step and slow-varying forces (e.g., non-bonded interactions) with a longer time step. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [35] | An accurate and efficient algorithm for handling long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic systems. |

| Energy Minimization | A preliminary step that relaxes the initial atomic configuration to the nearest local energy minimum, removing high-energy clashes before dynamics begin. |

| Monte Carlo Barostat [34] [39] | A stochastic method for pressure control that samples volume fluctuations by randomly changing the box size and accepting/rejecting the change based on a Metropolis criterion. |

Technical FAQs: Resolving Common Equilibration Issues

FAQ 1: My simulation crashes during NVT with an extremely high potential energy error. What should I do?

This common error is typically caused by a badly-equilibrated initial configuration, incorrect interactions, or parameters in the topology [40]. The solution involves a systematic diagnostic approach:

- Verify Initial Structure: Ensure your system has undergone successful energy minimization before starting NVT equilibration. A poorly minimized structure with overlapping atoms or high steric clashes will cause instability when velocities are applied [41] [40].

- Check Topology and Parameters: Carefully review your topology file for incorrect bonded parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals) or nonbonded parameters. Ensure all force field parameters are consistent and appropriate for your molecular system [40].

- Use a Thermostat with a Stochastic Term: For more robust temperature control, especially at the start of equilibration, use the v-rescale thermostat, which includes a stochastic term that helps in handling such situations [41].

- Consider Initial Velocities: If you are generating initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, using a slightly lower temperature (e.g., 200 K) can sometimes prevent the system from being pushed into a high-energy region of the potential energy surface, particularly important for machine-learning potentials [42].

FAQ 2: How long should I run NVT and NPT equilibration?

The required equilibration time is system-dependent and should be determined by monitoring the stabilization of key properties, not by a fixed duration [43].

- NVT Duration: Typically, 50-100 picoseconds (ps) is sufficient for the temperature to stabilize [41]. Monitor the temperature plot; the running average should reach a plateau at the desired value. If it hasn't stabilized, simply run the NVT step again using the output of the previous run as input [41].

- NPT Duration: Run until the system density has flat-lined around the desired value [44]. For simple systems, this may take 100 ps, but for more complex systems (e.g., organic solvents like cyclohexane), it could require 20 nanoseconds or more [45]. There is no universal "correct" time; stability of the property of interest (density for NPT, temperature for NVT) is the key metric [43] [44].

FAQ 3: Water molecules are leaking into the hydrophobic region of my membrane during equilibration. What is causing this?

This "leaky membrane effect" is a known issue for highly charged glycolipid bilayers but can occur in other systems. It is often triggered by a large initial pressure spike at the beginning of the NPT equilibration phase, which causes a momentary box expansion that allows water to penetrate [46].

- Solution: Implement a Stepwise Protocol: Instead of a direct NPT equilibration, introduce a short NVT equilibration phase before the NPT phase. This NVT pre-equilibration allows the particle distances and forces to partially relax at a fixed volume, thereby reducing the initial pressure spike when the barostat is switched on in the subsequent NPT step. This protocol is recommended for charged glycolipids and can prevent this destabilizing effect [46].

Essential Parameters and Research Reagents

The following table summarizes key parameters for NVT and NPT equilibration phases, serving as a starting point for researchers.

Table 1: Standard Equilibration Parameters for GROMACS

| Parameter | NVT Equilibration Value | NPT Equilibration Value | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | md (leap-frog) |

md (leap-frog) |

Molecular dynamics integrator [40] [45]. |

Time Step (dt) |

0.002 ps (2 fs) | 0.002 ps (2 fs) | Integration time step [40] [45]. |

| Constraints | h-bonds |

h-bonds |

Constrains bonds involving hydrogen atoms [40] [45]. |

Temperature Coupling (tcoupl) |

V-rescale |

V-rescale |

A modified Berendsen thermostat that uses a stochastic term for correct kinetics [41] [40]. |

Reference Temperature (ref_t) |

e.g., 300 K | e.g., 300 K | Target temperature for the simulation [40] [45]. |

Temperature Coupling Groups (tc-grps) |

Protein Non-Protein |

System or specific groups |

Coupling groups can be separated for more accurate temperature control [41] [40]. |

Pressure Coupling (pcoupl) |

no |

C-rescale (or Parrinello-Rahman) |

Barostat algorithm for pressure control. C-rescale is recommended for its improved performance over the older Berendsen barostat [45]. |

Reference Pressure (ref_p) |

— | 1.0 bar | Target pressure for the simulation [45]. |

| Compressibility | — | 4.5e-5 bar⁻¹ | Isothermal compressibility of water, a standard value for systems including water [45]. |

| Gen Vel | yes |

no |

Generate initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Typically done only at the start of NVT [40] [45]. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Equilibration |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile software package for performing molecular dynamics simulations; the primary engine for running NVT and NPT equilibration [46]. |

| Force Field (e.g., CHARMM, GROMOS) | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for all atoms in the system, governing bonded and non-bonded interactions [46] [40]. |

| Water Model (e.g., TIP4p) | Solvent model that defines the properties of water molecules in the simulation box [40]. |

| Thermostat (e.g., v-rescale, Nose-Hoover) | Algorithm that regulates the temperature of the system by scaling particle velocities [41] [46]. |

| Barostat (e.g., C-rescale, Parrinello-Rahman) | Algorithm that regulates the pressure of the system by scaling the simulation box dimensions [46] [45]. |

| Ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-, Ca2+) | Used to neutralize the total charge of the system and to simulate a specific ionic concentration, crucial for electrostatic interactions and system stability [46]. |

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard equilibration workflow, incorporating troubleshooting loops.

Workflow Diagram for NVT and NPT Equilibration

Detailed Methodology

Input Structure Preparation: Begin with a successfully energy-minimized system structure (GRO file). This ensures steric clashes and other high-energy interactions are resolved [41] [44]. In tools like the SAMSON GROMACS Wizard, an auto-fill function can be used to directly load the output from the minimization step [41].

NVT (Canonical) Equilibration:

- Objective: Bring the system to the target temperature and stabilize it by allowing the kinetic energy distribution to equilibrate, while keeping the volume fixed [41].

- Procedure:

- Set the

integratortomd. - Use a

dtof 0.002 ps (2 fs) is standard [40]. - Set the

tcoupltoV-rescaleand define theref_tfor your system (e.g., 300 K). It is often more accurate to couple different molecular groups (e.g.,ProteinandNon-Protein) separately [41] [40]. - Set

gen_vel = yesto assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution atgen_temp[40]. - Run for a sufficient number of steps (e.g., 50,000 steps for 100 ps).

- Set the

- Verification: After the run, plot the temperature time series. The temperature should fluctuate around the reference value. If the average temperature has not reached a plateau, the NVT equilibration must be extended by running it again, using the output of the previous run as the new input [41].

NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) Equilibration:

- Objective: Allow the system to reach the correct density by adjusting the volume of the simulation box under constant pressure conditions, following temperature stabilization in NVT [41] [44].

- Procedure:

- Continue with

continuation = yes. - Maintain the same temperature coupling settings from NVT.

- Switch pressure coupling on (

pcoupl) using a modern barostat likeC-rescale(or Parrinello-Rahman). Set theref_p(e.g., 1.0 bar) and thecompressibility(e.g., 4.5e-5 bar⁻¹ for water) [45]. - Set

gen_vel = noas velocities are already present from the NVT step [45]. - Run for a sufficient number of steps. The required time can vary significantly based on system complexity [45] [43].

- Continue with

- Verification: The primary metric for success is the stabilization of the system density. Plot the density over time; it should oscillate around a stable average value. If the density has not converged, the NPT equilibration must be restarted or extended using the last frame of the previous run [44].

Specialized Protocol for Challenging Systems

For systems that are highly sensitive to pressure changes, such as charged glycolipid membranes, a stepwise-thermalization protocol is recommended to avoid the "leaky membrane effect" [46]:

- Step 1: Perform a short NVT equilibration at a low temperature (e.g., 100 K) for a brief period (a few picoseconds). This allows interatomic forces to partially relax without introducing large pressure fluctuations.

- Step 2: Proceed with the standard NVT equilibration at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) as described above.

- Step 3: Continue with the standard NPT equilibration. This sequential approach mitigates the initial high-pressure spike that can cause box expansion and membrane instability [46].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why is a temperature ramp necessary instead of an instantaneous temperature jump? A: An instantaneous jump can cause excessive forces on atoms, leading to unphysical bond stretching, atomic overlaps, and simulation instability. A gradual ramp allows the system's energy to distribute more evenly, avoiding these "blow-up" scenarios and promoting stable equilibration [47].

Q: What is a safe rate for increasing temperature during a ramp? A: The safe rate is system-dependent. A general best practice is to start from a low temperature and increase it to about 30% above the desired application temperature [47]. The specific ramp rate should be determined through careful monitoring of system stability.

Q: My simulation still becomes unstable during the ramp. What should I check? A: First, verify your integration time step (POTIM). For systems with light elements like hydrogen, the time step should not exceed 0.7 fs; for oxygen-containing compounds, it should be less than 1.5 fs [47]. Second, ensure your electronic minimization routines are fully converged at each step to provide accurate forces [47].