Teleological Thinking in Biomedicine: From Cognitive Bias to Innovation Catalyst in Drug Development

This article explores the dual role of intuitive teleological concepts—the cognitive bias to attribute purpose and goal-directedness to biological entities and processes—within biomedical research and drug development.

Teleological Thinking in Biomedicine: From Cognitive Bias to Innovation Catalyst in Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the dual role of intuitive teleological concepts—the cognitive bias to attribute purpose and goal-directedness to biological entities and processes—within biomedical research and drug development. We first establish the foundational science, detailing the persistence of teleological, essentialist, and anthropocentric thinking even among experts. The content then examines methodologies to detect these biases in R&D settings and analyzes how they can both hinder scientific understanding and, when properly harnessed, fuel creative intuition. We subsequently evaluate evidence-based interventions, including refutation texts and metacognitive training, to mitigate misleading biases while preserving beneficial intuition. Finally, we compare the limitations of artificial intelligence with the unique strengths of human creative reasoning, concluding with a framework for leveraging cognitive construals to enhance innovation and problem-solving in pharmaceutical research.

The Cognitive Bedrock: Deconstructing Intuitive Teleology in Biological Reasoning

Within the realm of biological cognition, humans naturally and effortlessly employ systematic intuitive reasoning patterns to make sense of the living world. These patterns, known as cognitive construals, represent informal, often implicit ways of thinking that influence how we interpret biological entities, structures, and processes [1]. Decades of research in cognitive psychology and science education have identified three recurrent construals that shape biological reasoning: teleological, essentialist, and anthropocentric thinking [1] [2]. These construals provide foundational cognitive frameworks that help reduce complexity by organizing biological knowledge and guiding inferences about unknown biological phenomena [1]. While often adaptive in everyday reasoning, these intuitive patterns can persist into advanced scientific training, potentially leading to systematic misconceptions that impact research interpretation and science education [1] [2]. Understanding these construals is particularly crucial within research on intuitive teleological concepts about living beings, as they represent the cognitive underpinnings that such research seeks to characterize and explain.

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Teleological Thinking

Teleological thinking constitutes a form of causal reasoning in which the goal, purpose, function, or outcome of an event is treated as the cause of that event itself [3] [2]. This construal represents a bias toward explaining biological phenomena by reference to their presumed purposes rather than their antecedent physical causes [1]. In biological contexts, this manifests as explaining traits or processes in terms of what they are "for" – for example, stating that "bones exist to support the body" or "enzymes work to regulate chemical reactions" [3]. A central philosophical puzzle arises because such purposive explanations appear absent from other natural sciences like physics or chemistry, yet seem intuitively compelling and potentially necessary in biology [3]. The developmental trajectory of teleological thinking indicates a pattern of "pruning" – while young children apply it promiscuously to both living and non-living nature, adults become more selective, yet still consistently apply it to biological phenomena [2]. Research shows undergraduates endorse unwarranted teleological statements about biological phenomena 35% of the time, rising to 51% under time pressure [2].

Essentialist Thinking

Essentialist thinking reflects the intuitive tendency to believe that category membership is determined by an underlying, unobservable essence that conveys identity and causes observable similarities among category members [1] [2]. This cognitive construal involves the assumption that a core inherent property or "true nature" defines what something is and explains its observable characteristics [4] [1]. In biological reasoning, essentialism leads to several predictable patterns: (1) assumptions of within-category uniformity (members of a category are fundamentally similar because they share an essence), (2) belief in innate potential (category membership determines developmental trajectories), and (3) identity constancy (superficial transformations don't affect category membership because the underlying essence remains unchanged) [1] [2]. Historically, biological essentialism predated evolutionary theory, with Platonic idealism positing ideal forms for all living things [5]. From a cognitive perspective, essentialist thinking provides an important tool for reducing informational complexity by assuming homogeneity within categories and stability across transformations [1].

Anthropocentric Thinking

Anthropocentric thinking involves reasoning about the biological world through a human-centered lens, either by attributing human characteristics to non-human biological entities or by using humans as the primary reference point for understanding other organisms [1] [2]. This construal manifests in two primary ways: (1) viewing humans as unique and biologically discontinuous from other animals, and (2) reasoning about unfamiliar biological species or processes by analogy to humans [1] [6]. This "human exceptionalism" persists despite genetic evidence establishing humans as African great apes who share a recent common ancestor with chimpanzees [2]. Cognitive psychology research defines anthropocentric thinking specifically as "the tendency to reason about unfamiliar biological species or processes by analogy to humans" [6]. This analogical reasoning strategy can lead to both overattribution of human characteristics to similar organisms and underattribution of biological universals to dissimilar organisms [1]. The developmental emergence of this perspective is culturally mediated, appearing between ages 3-5 in urban children but being less prevalent in children with substantial exposure to nature [7] [6].

Quantitative Evidence and Research Findings

Persistence Across Development and Education

Research demonstrates the remarkable persistence of cognitive construals across different educational levels. The table below summarizes findings from a study comparing intuitive biological reasoning among 8th graders and university students [2].

| Population | Teleological Thinking | Essentialist Thinking | Anthropocentric Thinking |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8th Graders | Persistent intuitive reasoning | Persistent intuitive reasoning | Persistent intuitive reasoning |

| University Non-Biology Majors | Persistent with small decline | Persistent with small decline | Persistent with small decline |

| University Biology Majors | Persistent, minimal education effect | Persistent, minimal education effect | Persistent, minimal education effect |

| Key Finding | Consistent but small developmental differences | Consistent but small influence of biology education | Clear evidence of persistent intuitive reasoning |

The results reveal consistent but surprisingly small differences between 8th graders and college students on measures of intuitive biological thought, and similarly small influences of increasing biology education on reducing construal-based reasoning [2]. This persistence highlights the robustness of these cognitive patterns even in the face of formal scientific education.

Association with Biological Misconceptions

Research has documented specific linkages between cognitive construals and persistent biological misconceptions among biology students. The table below illustrates associations between specific construals and misconceptions observed in undergraduate biology majors [1].

| Cognitive Construal | Associated Misconception | Strength of Association |

|---|---|---|

| Teleological Thinking | "Evolution occurs for a purpose" | Stronger among biology majors |

| Essentialist Thinking | "Species are discrete with immutable essences" | Stronger among biology majors |

| Anthropocentric Thinking | "Humans are biologically unique/discontinuous" | Stronger among biology majors |

| Key Finding | Construal-misconception associations were stronger among biology majors than nonmajors |

Strikingly, the associations between specific construals and the misconceptions hypothesized to arise from those construals were stronger among biology majors than nonmajors [1]. This raises intriguing questions about whether university-level biology education may inadvertently reify construal-based thinking and related misconceptions rather than supplanting them with scientific conceptual frameworks.

Experimental Paradigms and Methodologies

Induction Task for Anthropocentric Thinking

The modified induction task pioneered by Carey and refined by later researchers provides a robust methodological approach for assessing anthropocentric reasoning [7]. This experimental protocol measures the tendency to privilege humans as an inductive base for projecting biological properties to other organisms.

Experimental Protocol:

- Participants: 64 urban children (32 3-year-olds and 32 5-year-olds) [7]

- Procedure: Children are introduced to one biological entity (either a human or a dog) and taught about a novel biological property that characterizes it (e.g., "People [or dogs] have andro inside") [7]

- Task Structure: The protocol is embedded within a guessing game context with "silly puppets" who need the child's help. For each question (e.g., "Do bees have andro inside?"), one puppet answers affirmatively while the other denies [7]

- Experimental Measure: The child decides which puppet is right for a series of different objects, including humans, nonhuman animals, plants, and artifacts [7]

- Key Dependent Variables: (i) Projections of novel biological property from human to dog versus dog to human; (ii) Strength of projections when property introduced with human versus dog [7]

Results Interpretation: The signatures of anthropocentric reasoning include: (1) greater willingness to draw inferences from human to nonhuman animal than vice versa; and (2) stronger projections to other animals when properties are introduced with human rather than nonhuman animal [7]. This paradigm successfully demonstrated that anthropocentrism is an acquired perspective that emerges between 3-5 years in urban children, rather than an obligatory first step in biological reasoning [7].

Teleological Explanation Assessment

Kelemen's research program has developed reliable measures for assessing promiscuous teleological thinking across development [2]. The methodology examines the tendency to endorse purpose-based explanations for both living and non-living natural phenomena.

Experimental Protocol:

- Participants: Ranges from young children to university undergraduates [2]

- Procedure: Participants are presented with statements about various phenomena and asked to judge their validity [2]

- Stimuli Examples: "The rocks were pointy so that animals wouldn't sit on them and smash them" (non-living natural object); "Birds exist for flying" (biological kind); "Earthworms tunnel underground to aerate the soil" (biological process) [2]

- Testing Conditions: Can be administered under normal conditions or under cognitive load/time pressure to assess intuitive versus reflective responses [2]

- Key Dependent Measure: Proportion of unwarranted teleological statements endorsed across different domains [2]

Results Interpretation: Young children (6-year-olds) typically favor teleological explanations for a broad range of phenomena, while adults become more selective but still consistently endorse biological teleology [2]. Under time pressure, undergraduate students' endorsement of unwarranted teleological biological statements increases from 35% to 51%, indicating that this construal remains available as an intuitive reasoning strategy [2].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table details key methodological approaches and their functions in researching cognitive construals about living beings.

| Research Approach | Function in Construal Research |

|---|---|

| Modified Induction Task | Measures anthropocentric reasoning patterns through property projection from human vs. nonhuman bases [7] |

| Teleological Statement Battery | Assesses promiscuous teleology through endorsement of purpose-based explanations [2] |

| Essentialist Reasoning Measures | Evaluates assumptions about category uniformity, innate potential, and identity constancy [1] |

| Cross-Cultural Comparative Design | Distinguishes universal cognitive tendencies from culturally acquired perspectives [7] [6] |

| Cognitive Load Methodology | Differentiates between intuitive versus reflective reasoning patterns [2] |

| Developmental Trajectory Analysis | Tracks emergence and persistence of construals across age and education levels [2] |

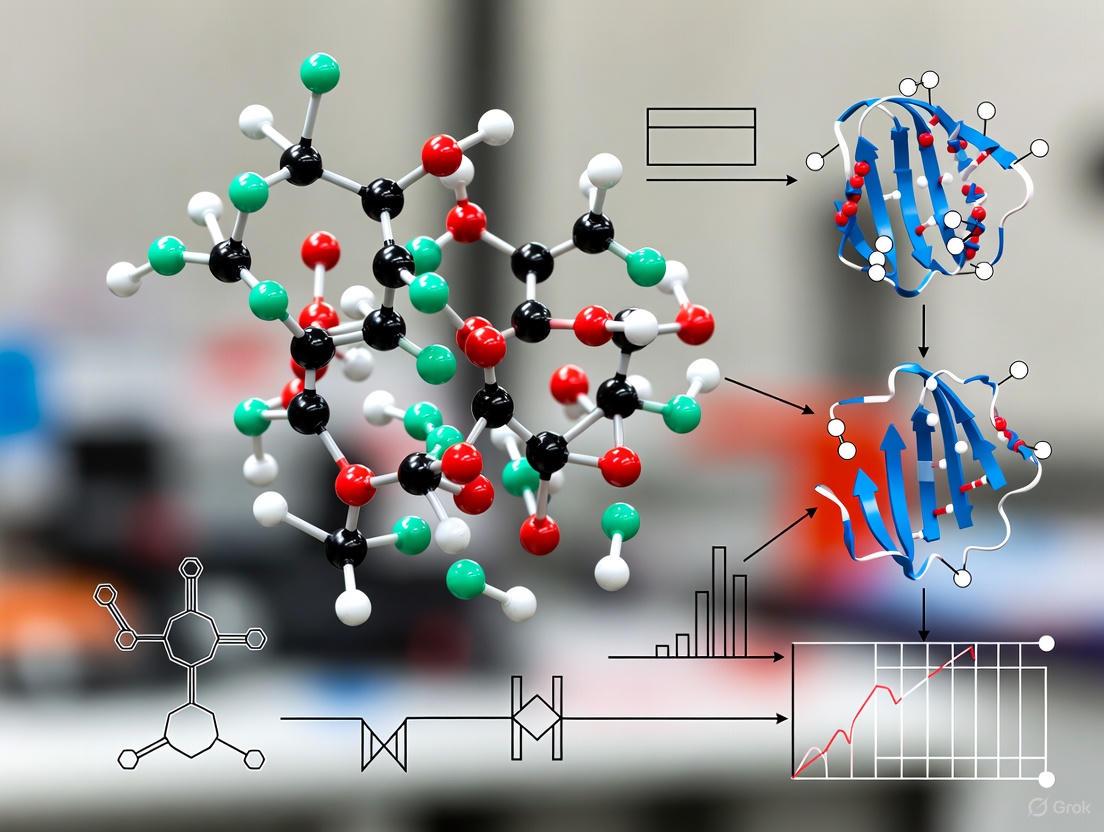

Conceptual Relationships and Research Workflows

Cognitive Construals Conceptual Framework

Experimental Assessment Workflow

Implications for Research and Education

The documented persistence of cognitive construals among biology students and professionals has significant implications for both biology education and scientific research practice. Research indicates that these intuitive patterns of thought remain available as reasoning strategies even after extensive scientific training [2]. This persistence suggests that mastery of scientific concepts may not necessarily replace intuitive construals but rather exists alongside them, with contextual factors determining which reasoning system is activated [2]. For biology education, this underscores the necessity of explicitly addressing intuitive conceptions rather than assuming they will be automatically overwritten by formal instruction [1] [2]. For research professionals, particularly in fields like drug development where accurate biological reasoning is crucial, awareness of these cognitive tendencies can help mitigate their potential influence on experimental design and interpretation. The stronger association between construals and misconceptions among biology majors compared to nonmajors further suggests that specialized biology education may sometimes strengthen rather than weaken these intuitive links, possibly through the use of shorthand explanations that inadvertently activate construal-based thinking [1]. This highlights the importance of developing educational approaches that directly target the implicit assumptions underlying these cognitive construals.

Teleology, derived from the Greek telos (end, purpose), represents a mode of explanation in which phenomena are accounted for by reference to the ends or goals they serve rather than solely by antecedent causes [8]. Within biological sciences, this manifests as the attribution of functions, purposes, or goals to biological traits—for example, stating that "the chief function of the heart is the transmission and pumping of the blood" or that "the primate hand is designed (by natural selection) for grasping" [9] [8]. The persistence of teleological reasoning represents a fascinating continuum from childhood cognitive intuitions to sophisticated methodological frameworks employed by professional scientists. This persistence is particularly noteworthy in biology, where teleological language remains largely ineliminable from disciplines including evolutionary biology, genetics, medicine, ethology, and psychiatry because it plays an important explanatory role [9].

The fundamental question surrounding teleology in biology concerns how apparently goal-directed explanations can be legitimate in a post-Darwinian scientific context that has explicitly rejected divine design and vitalistic forces [9] [8]. This paper examines the trajectory of teleological thinking from its origins as a deep-seated cognitive intuition in childhood through its various transformations into the methodologically sophisticated frameworks utilized by research scientists. Understanding this continuum is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who must navigate the complex interplay between intuitive reasoning patterns and disciplined scientific explanation in their work, particularly when conceptualizing complex biological systems and therapeutic mechanisms.

Developmental Foundations: The Origins of Teleological Thinking

Childhood Teleological Intuitions

Research in cognitive development has revealed that children exhibit a robust tendency to provide teleological explanations for the features of organisms and artifacts from a very early age (3-4 years old) [10]. This intuitive teleology represents a default cognitive framework through which young children make sense of the natural world, attributing purposes not only to biological traits but often extending these explanations to non-living natural phenomena as well.

Table 1: Developmental Shift in Children's Teleological Explanations

| Age Group | Explanatory Pattern | Example Explanations |

|---|---|---|

| 3-4 years | Non-selective teleology | "Mountains are for climbing," "Clouds are for raining" [10] |

| 5-7 years | Transitional phase | Beginning to distinguish between organisms and artifacts |

| 8+ years | Selective teleology | "Eyes are for seeing" (organisms) but not "Rocks are for sitting" (natural objects) [10] |

The pervasiveness of teleological thinking in childhood has been documented through structured experimental protocols. In one representative study, children aged 5-8 were presented with various entities (organisms, artifacts, and non-living natural objects) and asked to explain particular features such as color and shape [10]. The research demonstrated a clear developmental shift from what Kelemen terms "promiscuous teleology" in preschool children to a more selective teleology in second-grade children, who provided teleological explanations mostly for the shape of organisms' feet and the shape of artifacts, while increasingly rejecting such explanations for non-living natural objects [10].

Theoretical Accounts of Childhood Teleology

Two prominent theoretical accounts have emerged to explain the origins and persistence of teleological thinking in development:

Selective Teleology Account (Keil): Proposes that children naturally distinguish between organisms and artifacts, applying teleological explanations selectively to these domains based on their understanding that the properties of organisms serve the organisms themselves, whereas the properties of artifacts serve the purposes of the agents who use them [10].

Promiscuous Teleology Account (Kelemen): Suggests that children's teleological bias derives from an early sensitivity to intentional agents as object makers and users, leading them to view objects as "made for some purpose" across all domains initially, with differentiation developing through education and cognitive maturation [10].

These developmental patterns are not merely of theoretical interest; they represent foundational cognitive biases that persist into adulthood and can resurface in scientific contexts when complex biological phenomena require explanation.

Philosophical and Historical Context: The Legitimacy Debate

Historical Transitions in Biological Teleology

The status of teleology in biology has undergone significant transformations throughout the history of science:

Table 2: Historical Transitions in Biological Teleology

| Historical Period | Conceptual Framework | Representative Thinkers | Status of Teleology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Darwinian | Natural Theology | John Ray, William Paley | Explicitly theological; Evidence of divine design [8] |

| Early Darwinian | Natural Selection | Charles Darwin | Controversial; Purged or revived teleology? [9] |

| Modern Synthesis | Neo-Darwinism | Ernst Mayr, G.G. Simpson | Largely rejected; Suspicion of orthogenesis [8] |

| Contemporary | Multiple Frameworks | Ayala, Lennox, Toepfer | Naturalized; Recognized as ineliminable [9] [11] |

Prior to Darwin, the appearance of function in nature was predominantly interpreted through the lens of natural theology, with biological structures understood as evidence of conscious design by a benevolent creator [8]. William Paley's watchmaker analogy epitomized this view, arguing that just as a watch implies a watchmaker, biological complexity implies a divine designer [8]. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection provided a naturalistic alternative to explain apparent design, yet Darwin himself continued to use the language of "final causes" throughout his career [9].

Contemporary Philosophical Positions

Modern philosophical debates reveal divergent perspectives on the legitimacy of teleology in biological science:

Eliminativist Position: Advocates for the complete elimination of teleological language from biology, viewing it as an outdated prescientific holdover. Proponents argue that teleological statements can and should be rephrased in purely causal terms without loss of meaning [8].

Shorthand Position: Acknowledges the pervasiveness of teleological language but treats it as a convenient shorthand that can be translated into non-teleological explanations referencing natural selection and evolutionary history [8].

Irreducibility Position: Maintains that teleological explanations are ineliminable from biology because they capture aspects of biological phenomena that cannot be fully captured by non-teleological explanations [8]. Philosopher Francisco Ayala, for instance, argues that teleological explanations are appropriate in three separate contexts: when agents consciously anticipate goals, when mechanisms serve functions despite no conscious anticipation, and when biological traits can be explained by reference to natural selection [8].

Georg Toepfer has advanced a particularly strong version of the irreducibility position, arguing that "Nothing in biology makes sense, except in the light of teleology" and that fundamental biological concepts like 'organism' and 'ecosystem' are only intelligible within a teleological framework [11]. On this view, evolutionary theory cannot provide the foundation for teleology because it already presupposes the existence of organisms as organized, functional systems [11].

Methodological Approaches: Investigating Teleological Reasoning

Experimental Paradigms for Studying Teleology

Research on teleological reasoning employs standardized experimental protocols to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of this cognitive tendency across different populations:

Table 3: Key Methodological Approaches in Teleology Research

| Method Type | Population | Core Protocol | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explanation Selection | Children (3-8 years) | Presentation of entities (organisms, artifacts, natural objects) with request for explanations [10] | Preference for teleological vs. physical explanations |

| Forced-Choice Tasks | Secondary students | Choice between teleological and mechanistic explanations for biological phenomena [12] | Consistency of teleological preferences |

| Conceptual Analysis | Biology experts | Analysis of functional language in biological literature [9] [8] | Prevalence and type of teleological formulations |

| Interview Protocols | All ages | Open-ended questions about biological phenomena [12] | Spontaneous use of teleological reasoning |

These methodologies reveal that teleological explanations are not restricted to biological phenomena but may be given for chemical and physical phenomena as well, with students sometimes believing that "atoms react in order to form molecules because they need to achieve a full outer shell" or that "things fell because they had to" [10].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key methodological components used in teleology research:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Teleology Studies

| Research Component | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Sets | Standardized materials for eliciting explanations | Photographs or drawings of organisms, artifacts, and natural objects with distinctive features [10] |

| Explanation Coding Systems | Systematic categorization of responses | Coding schemas distinguishing teleological, mechanistic, and other explanation types [10] [12] |

| Standardized Interview Protocols | Consistent data collection across participants | Structured questions about feature functionality (e.g., "Why do birds have wings?") [10] |

| Control Conditions | Isolate teleological reasoning from other factors | Comparison between functional and non-functional features [10] |

| Longitudinal Designs | Track developmental trajectories | Repeated measures across age groups from preschool to adulthood [10] |

Teleology in Professional Biological Practice

The Functional Reasoning Framework

Despite historical controversies, teleological language remains pervasive in professional biological literature, evident in claims such as "The Predator Detection hypothesis remains the strongest candidate for the function of stotting [by gazelles]" or discussions of how "other antimalarial genes take over the protective function of the sickle-cell gene" [9]. This persistence suggests that teleological framing serves important epistemic functions in biological practice.

The distinction between ontological and epistemological uses of teleology is crucial for understanding its legitimate role in biological science. Ontological teleology assumes that goals or purposes actually exist in nature and direct natural mechanisms, a position rejected by modern biology. Epistemological teleology, in contrast, uses the notion of purpose as a methodological tool for organizing biological knowledge without attributing conscious agency or vital forces to nature [12]. This epistemological approach has been formalized through the concept of "teleonomy," introduced by Pittendrigh (1958) to distinguish legitimate functional analysis from illegitimate metaphysical teleology [12].

Conceptual Framework of Biological Teleology

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual structure of teleological reasoning in biological contexts:

Naturalizing Teleology: Selected Effects and Beyond

Contemporary philosophical accounts have developed naturalized approaches to biological teleology that avoid supernatural or vitalistic commitments. The most influential of these is the selected effects theory of function, which defines the function of a trait as the effect for which it was selected by natural selection in the past [9] [8]. On this account, stating that "the function of the heart is to pump blood" is shorthand for "hearts were selected by natural selection because they pumped blood."

However, alternative naturalistic accounts include:

Causal Role Theories: Define functions in terms of the contemporary causal contributions that traits make to the systems of which they are parts, without reference to evolutionary history [9].

Organizational Theories: Ground biological teleology in the self-maintaining organizational closure of living systems, where the function of a trait is its contribution to the maintenance of the organization that in turn maintains the trait [11].

These naturalized frameworks allow biologists to employ functional language while remaining committed to a thoroughly naturalistic, mechanistic understanding of living systems.

Implications for Research and Education

Challenges in Biological Education

Teleological reasoning represents a significant conceptual obstacle in biology education, particularly in understanding evolution by natural selection [10] [12]. Students frequently misinterpret evolutionary processes as goal-directed, believing that traits evolve "in order to" fulfill needs or that evolution itself is progressive and directional [8] [12]. This tendency persists even after instruction and is not limited to biological novices; research has documented teleological reasoning among secondary students, undergraduate biology majors, and even graduate students [12].

The problem extends beyond evolution education to physiology, where students might explain that "we have kidneys to excrete waste products" without being able to elaborate the underlying physiological mechanisms [13] [12]. This teleological reasoning tendency distorts biological relationships between mechanisms and functions and has been argued to be closely related to the intentionality bias—a predisposition to assume an intentional agent—and even to creationist beliefs [12].

Addressing Teleological Reasoning in Professional Contexts

For research scientists and drug development professionals, awareness of teleological reasoning patterns is crucial for avoiding conceptual pitfalls in experimental design and interpretation. Several strategies can help mitigate misleading teleological influences:

Explicit Mechanism Tracing: When employing functional language, consciously elaborate the underlying causal mechanisms that realize the function.

Historical Awareness: Recognize the distinction between evolutionary origins (phylogeny) and current utility, acknowledging that traits may be co-opted for new functions (exaptation) [8].

Conceptual Clarification: Distinguish between heuristic uses of teleological language and commitment to teleological metaphysics in scientific reasoning.

Educational Intervention: Develop explicit instructional approaches that address teleological intuitions directly rather than ignoring them or allowing them to persist unchallenged.

The conceptual overlap between biological function and teleology lies in the shared notion of telos (end, goal), creating an educational challenge: while biologists use telos as an epistemological tool for identifying phenomena functionally, students easily slip from functional reasoning into inadequate teleological reasoning that assumes purposes exist in nature [12]. Addressing this challenge requires both conceptual clarity about the legitimate role of functional reasoning in biology and psychological awareness of the cognitive factors that make teleological explanations intuitively compelling.

The persistence of teleology from childhood to expert-level scientists reveals both the deep cognitive roots of purpose-based explanation and the possibility of developing these intuitions into methodologically sophisticated frameworks for biological investigation. Rather than attempting to eliminate teleological language entirely—a project that would likely prove both impossible and undesirable—the scientific community benefits from cultivating reflective awareness of the legitimate and illegitimate uses of teleological reasoning.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this means employing functional language with conscious attention to its naturalistic foundations, recognizing that the appearance of purpose in biological systems emerges from the complex interplay of evolutionary history, self-organizing dynamics, and mechanistic processes. By navigating the continuum between intuitive teleology and scientific explanation with intentionality and conceptual clarity, biological science can continue to harness the heuristic power of functional reasoning while remaining grounded in naturalistic methodology.

Teleological Misconceptions as Conceptual Obstacles in Understanding Evolution and Mechanisms

Teleological misconceptions represent a significant conceptual obstacle in evolution education, characterized by the intuitive reasoning that features exist or changes occur to fulfill a specific future purpose or goal. This cognitive bias leads to explanations such as "bacteria mutate in order to become resistant to antibiotics" or "polar bears became white because they needed to disguise themselves in the snow" [14]. These misconceptions are not merely factual errors but function as epistemological obstacles – intuitive ways of thinking that are both transversal (applicable across domains) and functional (serving cognitive purposes) yet substantially interfere with scientific understanding [14]. The persistence of teleological reasoning across age groups and educational levels establishes it as a fundamental challenge in biological education, particularly in understanding evolutionary mechanisms [15] [16].

Research indicates that teleological thinking persists because it fulfills important cognitive functions, including heuristic, predictive, and explanatory roles [14]. This thinking style is deeply rooted in human cognition, with studies revealing that not only children but also educated adults and even professional scientists demonstrate tenacious teleological tendencies when under cognitive load or time pressure [16] [14]. The central problem for evolution education lies in the underlying consequence etiology – whether a trait exists because of its selection for positive consequences (scientifically legitimate) or because it was intentionally designed or simply needed for a purpose (scientifically illegitimate) [15].

The Psychological and Cognitive Foundations of Teleological Reasoning

Forms and Prevalence of Intuitive Reasoning

Teleological reasoning exists within a constellation of intuitive reasoning patterns that impact biological understanding. Research has identified three primary forms of intuitive reasoning linked to biological misconceptions:

Teleological Reasoning: A causal form of intuitive reasoning that assumes implicit purpose and attributes goals or needs as contributing agents for changes or events [16]. This manifests in statements like "finches diversified in order to survive" or "fungi grow in forests to help with decomposition" [16].

Essentialist Reasoning: The tendency to assume members of a categorical group are relatively uniform and static due to a core underlying property or "essence" [16]. This thinking disregards the importance of variability in natural selection and often underlies "transformational" views of evolution where entire populations gradually transform as a unit.

Anthropocentric Reasoning: Reasoning by analogy to humans, either by inappropriately attributing biological importance to humans relative to other organisms or by projecting human qualities onto non-human organisms or processes [16].

Studies with undergraduate populations reveal the striking prevalence of these reasoning patterns. In investigations of students' understanding of antibiotic resistance, intuitive reasoning was present in nearly all students' written explanations, and acceptance of misconceptions was significantly associated with the production of intuitive thinking (all p ≤ 0.05) [16].

Theoretical Frameworks: From "Promiscuous Teleology" to "Relational-Deictic" Reasoning

The dominant theory of "promiscuous teleology" suggests humans are naturally biased to mistakenly construe natural kinds as if they were intentionally designed for a purpose [17]. However, this theory introduces developmental and cultural paradoxes. If infants readily distinguish natural kinds from artifacts, why do school-aged children erroneously conflate this distinction? Furthermore, if Western scientific education is required to overcome promiscuous teleological reasoning, how can one account for the ecological expertise of non-Western educated, indigenous populations? [17]

An alternative relational-deictic framework proposes that teleological statements may not necessarily reflect a deep-rooted belief that nature was designed for a purpose, but instead may reflect an appreciation of the perspectival relations among living things and their environments [17]. This framework suggests that purposes should be seen as plural, context-dependent properties of relations rather than as intrinsic properties of individual entities, which aligns with ecological reasoning across development and cultural communities [17].

Table 1: Association Between Intuitive Reasoning and Acceptance of Misconceptions in Undergraduate Biology Students [16]

| Student Group | Accept Misconceptions | Teleological Reasoning | Essentialist Reasoning | Anthropocentric Reasoning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entering Biology Majors | Strong association | Strong association | Strong association | Strong association |

| Advanced Biology Majors | Significant association | Significant association | Significant association | Significant association |

| Non-Biology Majors | Moderate association | Moderate association | Moderate association | Moderate association |

| Biology Faculty | Not assessed | Present under cognitive load | Present under cognitive load | Present under cognitive load |

Epistemological Analysis: The Problem of Teleology in Biology

Historical and Philosophical Context

The Western philosophical tradition of explaining the natural world through teleological assumptions dates back to Plato and Aristotle [15] [14]. Plato considered the universe as the artifact of a Divine Craftsman (Demiurge), where final causes determined transformations [15]. Aristotle, while rejecting intentional design, maintained that organisms acquired features because they were functionally useful, representing a "natural" teleology without intention or design [15].

The Scientific Revolution questioned teleology's validity for three primary reasons: (1) historical association with religious perspectives and supernatural assumptions; (2) apparent inversion of cause and effect incompatible with classical causality; and (3) misalignment with the nomological-deductive model of scientific explanation [14]. Despite Darwin's naturalistic explanation of adaptation through natural selection, which rendered divine design references unnecessary, teleological language persisted in biological discourse [14]. This creates the central "problem of teleology in biology" – the discipline retained teleological explanations even after providing naturalistic mechanisms for adaptive complexity.

Distinguishing Legitimate and Illegitimate Teleology in Evolution

A crucial distinction exists between legitimate and illegitimate teleological explanations in evolutionary biology. As Kampourakis (2020) argues, the problem is not teleology per se but the underlying "design stance" – the intuitive perception of design in nature independent from religiosity [15]. This distinction can be understood through different causal explanations for biological features:

- Evolutionary Explanation: Backward-looking, referencing ultimate causes (evolution) at population level

- Developmental Explanation: Backward-looking, referencing proximate causes (development) at individual level

- Teleological Explanation: Forward-looking, referencing final causes (function) at population or individual level [15]

Scientifically legitimate teleological explanations in biology are those that rely on consequence etiology grounded in natural selection – a trait exists because of its selection for positive consequences for its bearers [15]. In contrast, illegitimate teleological explanations assume intentional design or that traits arise because they are needed [15]. The educational challenge therefore centers on helping students distinguish between selection-based and design-based consequence etiologies.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Assessing Teleological Reasoning: Protocol Design

Research into teleological misconceptions employs specific methodological approaches to identify and quantify these reasoning patterns:

Written Assessment Protocol [16]:

- Tool: Open-response written assessments presenting evolutionary scenarios (e.g., antibiotic resistance)

- Coding Framework: Systematic analysis of responses for teleological, essentialist, and anthropocentric reasoning indicators

- Validation: Coupled with Likert-scale agreement measures for common misconceptions

- Population Application: Administered across diverse educational levels (entering majors, advanced majors, non-majors, faculty)

Teleological Statement Classification [15] [14]:

- Identification: Categorizing explanations containing "...in order to...", "...for the sake of...", "...so that..." constructions

- Etiology Analysis: Distinguishing between selection-based vs. design-based consequence etiologies

- Context Evaluation: Assessing reasoning across biological phenomena (origin of traits, evolutionary change, ecosystem functions)

Intervention Studies: Experimental Design Principles

Intervention research employs rigorous experimental design to test effectiveness of instructional approaches:

Power Analysis and Sample Size Optimization [18]:

- Component Definition: Pre-specification of (1) sample size, (2) expected effect size, (3) within-group variance, (4) false discovery rate, and (5) statistical power

- Effect Size Estimation: Derived from pilot studies, published literature, or theoretical principles

- Variance Consideration: Higher within-group variance relative to between-group variance requires larger samples

Avoiding Pseudoreplication [18]:

- Independent Replication: Ensuring correct unit of replication (independently assigned treatment conditions)

- Statistical Control: Using mixed-effects modeling to account for non-independence when unavoidable

- Experimental Evolution Example: Maintaining independent sub-populations assigned to different selective environments

Table 2: Quantitative Findings on Teleological Reasoning Prevalence Across Populations [16]

| Population | Sample Characteristics | Teleological Reasoning Prevalence | Association with Misconceptions | Contextual Influences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool Children | Multiple studies | Extensive teleological explanations | Strong for natural phenomena | Artifacts and living things |

| Elementary Students | Cross-sectional | "Made for something" reasoning | Strong across domains | Artifacts and organisms |

| High School Students | International samples | Persistent need-based explanations | Strong in evolutionary contexts | Adaptation explanations |

| Undergraduate Biology Majors | Entering vs. advanced | Significant in written explanations | p ≤ 0.05 | Antibiotic resistance context |

| Biology Graduate Students | Limited studies | Present under constrained conditions | Moderate | Complex evolutionary scenarios |

| Professional Scientists | Physics specialists | Tenacious under cognitive load | Not assessed | Time-pressure conditions |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Teleology Research

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Response Assessment Tools | Elicit naturalistic explanations | Written responses to evolutionary scenarios [16] |

| Teleological Coding Framework | Systematically classify reasoning | Identification of "...in order to..." statements with consequence etiology analysis [15] |

| Likert-Scale Agreement Measures | Quantify misconception acceptance | Agreement levels with teleological statements across contexts [16] |

| Cognitive Load Manipulations | Test robustness of scientific understanding | Time-pressure conditions with conceptual questions [14] |

| Cross-Cultural Comparisons | Distinguish universal vs. culturally-specific patterns | Western vs. indigenous communities' ecological reasoning [17] |

| Developmental Trajectory Tracking | Map conceptual change across ages | Longitudinal studies from childhood through adulthood [16] |

| Intervention-Specific Protocols | Test educational approaches | Pre-/post-test designs with experimental and control groups [14] |

Educational Implications and Intervention Strategies

From Elimination to Metacognitive Regulation

Traditional "eliminative" approaches that seek to completely eradicate teleological thinking have proven ineffective [14]. Instead, research supports educational approaches focused on developing metacognitive vigilance – sophisticated ability for regulating teleological reasoning [14]. This approach comprises three key components:

- Declarative Knowledge: Knowing what teleology is and its various forms

- Procedural Knowledge: Knowing how to recognize teleological reasoning in multiple contexts

- Conditional Knowledge: Knowing why and when teleological reasoning is or isn't appropriate [14]

This regulatory framework aligns with the understanding that teleological reasoning functions as an epistemological obstacle that cannot be entirely eliminated but can be effectively managed through educational interventions.

Specific Instructional Methodologies

Effective interventions for addressing teleological misconceptions include:

Tree-Reading Instruction [19]:

- Challenge: Teleological interpretations of evolutionary trees as linear progressions

- Intervention: Explicit instruction in tree-reading skills, focusing on branching patterns and relative relationships

- Outcome: Reduced perception of evolutionary "goals" or "targets"

Design Stance Addressing [15]:

- Challenge: Intuitive perception of design in nature independent of religiosity

- Intervention: Contrasting selection-based vs. design-based consequence etiologies

- Outcome: Improved distinction between legitimate and illegitimate teleology

Relational-Deictic Framework Application [17]:

- Challenge: Oversimplified attribution of single purposes to biological features

- Intervention: Emphasizing multiple, context-dependent functions within ecological systems

- Outcome: More nuanced understanding of biological functions beyond simple teleology

Teleological misconceptions represent profound conceptual obstacles rooted in intuitive reasoning patterns that persist across development and educational levels. The research evidence indicates that effective approaches must move beyond simple correction of misconceptions toward developing metacognitive regulatory skills. The distinction between legitimate selection-based teleology and illegitimate design-based teleology provides a crucial framework for both research and instruction.

Future research directions should further explore the relational-deictic framework as an alternative to promiscuous teleology accounts, investigate cross-cultural variations in teleological reasoning, and develop more refined assessment tools that distinguish between different types of consequence etiologies. For educational practice, interventions should explicitly address the design stance underlying teleological explanations while recognizing that teleological thinking cannot be entirely eliminated but can be effectively regulated through targeted metacognitive development.

The integration of epistemological, psychological, and educational perspectives provides the most comprehensive approach to addressing teleological misconceptions as conceptual obstacles, ultimately supporting more sophisticated understanding of evolutionary mechanisms and biological systems.

Anthropocentric Thinking and Its Impact on Model Organism Selection and Generalizability

Anthropocentric thinking, a cognitive construal that places humans at the center of our understanding of the natural world, significantly influences multiple facets of biology education and research [20]. This thinking manifests through the use of human analogies to explain non-human concepts, beliefs in human uniqueness and superiority, and the attribution of human properties to non-human entities [20]. Concurrently, teleological reasoning—the explanation of phenomena by reference to goals or purposes—represents a pervasive cognitive bias in understanding biological systems [21] [9]. These two cognitive frameworks are deeply interconnected, often leading researchers to intuitively attribute purpose to natural entities and processes, frequently with humans as the implicit or explicit beneficiaries of these purposes [22].

Within scientific research, particularly in preclinical drug development, these cognitive biases significantly impact model organism selection and the subsequent generalizability of findings to human applications. The presumption that biological processes are conserved and function with human-centric purposes can lead to inappropriate model selection and overestimation of translational potential [20]. This review examines the psychological underpinnings of these biases, presents experimental evidence of their impact, and proposes methodological frameworks to mitigate their effects in biomedical research.

Theoretical Foundations: Cognitive Origins of Anthropocentric and Teleological Biases

Developmental and Cultural Emergence of Anthropocentrism

Contrary to long-held developmental theories, recent evidence suggests that anthropocentrism is not an initial step in children's reasoning about the biological world but rather an acquired perspective that emerges between 3 and 5 years of age in children raised in urban environments [7]. Urban 5-year-olds demonstrate robust anthropocentric patterns in biological reasoning, while 3-year-olds show no hint of this bias [7]. This developmental trajectory indicates that anthropocentrism is culturally mediated rather than biologically predetermined.

Cultural and experiential factors significantly influence these cognitive patterns. Research comparing urban and rural children reveals that those with direct experience with nonhuman animals (typically rural children) do not privilege humans over nonhuman animals when reasoning about biological phenomena [7]. This suggests that limited direct experience with diverse biological species fosters reliance on human-centered reasoning frameworks.

Promiscuous Teleology and Intentional Stance

The theory of promiscuous teleology posits that humans naturally default to teleological explanations because we overextend an "intentional stance"—the attribution of beliefs and desires to agents [21]. This theory holds that children and adults readily endorse functional explanations not just for human-made artifacts and properties of biological organisms, but also for whole biological organisms and natural non-living objects [21].

An alternative "relational-deictic" interpretation proposes that the teleological stance may not necessarily reflect a deep-rooted belief that nature was designed for a purpose, but instead may reflect an appreciation of the perspectival relations among living things and their environments [22]. This framework helps explain why indigenous populations with extensive ecological knowledge may employ teleological language without necessarily holding creationist beliefs about natural kinds [22].

Table 1: Theoretical Accounts of Teleological Reasoning

| Theory | Core Mechanism | Developmental Pattern | Cultural Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promiscuous Teleology | Overextension of intentional stance | Decreases with scientific education | Higher in Western-educated populations |

| Selective Teleology | Domain-specific teleological bias | Remains stable across development | Limited cultural variation |

| Relational-Deictic | Ecological perspective-taking | Increases with environmental expertise | Higher in indigenous populations |

Experimental Evidence: Documenting Anthropocentric Bias in Biological Reasoning

Induction Task Methodology

The foundational experimental paradigm for investigating anthropocentric reasoning in biological domains employs an inductive reasoning task [7]. The standardized protocol involves:

- Participants: 64 urban children (32 3-year-olds and 32 5-year-olds)

- Stimuli: Biological entities (human or dog) paired with novel biological properties

- Procedure:

- Introduction to one biological entity (either human or dog)

- Teaching about a novel biological property characterizing it (e.g., "has andro inside")

- Inquiry whether this property exists inside other entities (humans, nonhuman animals, plants, artifacts)

- Embedded within a puppet game to engage children systematically

- Controls: Counterbalancing of base entity and property assignment

- Dependent Measures: Patterns of property projection across biological categories

This modified protocol successfully engages children as young as 3 years, generating systematic responding where previous methods failed [7].

Anthropocentric Language in Biology Education

Recent research investigates how anthropocentric language impacts biology misconceptions in undergraduate education [20]. The experimental design involves:

- Participants: Undergraduates at Northeastern University

- Stimuli: Passages about biology concepts (neuroscience of emotion or antibiotic resistance)

- Conditions:

- Control group: Passage without human-specific language

- Active group: Passage using human examples to explain concepts

- Measures:

- Free response explanations analyzed for accuracy, misconceptions, and anthropocentrism

- Human exceptionalism measures (e.g., common ancestor recognition across species)

- Analysis: Quantitative assessment of misconception prevalence between conditions

Preliminary results indicate that preexisting anthropocentrism, rather than experimental manipulation, most strongly predicts exceptionalist ideas in responses [20].

Table 2: Experimental Paradigms for Investigating Anthropocentric Bias

| Methodology | Key Manipulation | Primary Measures | Population Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inductive Reasoning Task | Base entity (human vs. non-human) | Pattern of property generalization | Children (3-5 years), urban vs. rural |

| Language Intervention Study | Anthropocentric vs. non-anthropocentric explanations | Concept accuracy, misconceptions | Undergraduate students |

| Human Exceptionalism Assessment | Common ancestor recognition tasks | Inclusion of various species as human relatives | Diverse educational backgrounds |

Impact on Model Organism Research: From Cognitive Bias to Methodological Challenge

Taxonomic Range and Evolutionary Distance

Anthropocentric thinking influences model organism selection through taxonomic chauvinism—the preferential use of organisms perceived as more closely related to humans [20]. This bias manifests in research design through:

- Limited phylogenetic representation in experimental systems

- Overemphasis on mammalian models despite relevant biological processes in distantly related organisms

- Underutilization of informative invertebrate and microbial systems for understanding conserved biological processes

Research on human exceptionalism demonstrates that individuals consistently underestimate the degree to which biological processes are shared across diverse taxa [20]. When presented with species ranging from insects to primates and asked which share a common ancestor with humans, participants frequently select only primates or no species, despite all species sharing common ancestry with humans [20].

Teleological Assumptions in Experimental Design

Teleological reasoning influences model organism research through implicit assumptions about biological purpose [21] [9]. Researchers may unconsciously:

- Design experiments assuming traits evolved "for" specific human-relevant functions

- Interpret results through human-centric functional frameworks

- Overlook alternative evolutionary explanations that don't center human biology

The intention-based teleology observed in experimental settings leads researchers to attribute design-like purpose to biological traits, potentially obscuring their actual evolutionary history and constraining hypothesis generation [21].

Methodological Recommendations: Mitigating Anthropocentric Bias in Research Design

Model System Selection Framework

To counter anthropocentric bias in organism selection, researchers should adopt a deliberative selection framework:

- Explicit justification of model system choice based on biological criteria relevant to research question

- Comparative approaches incorporating multiple species across wider taxonomic ranges

- Consideration of evolutionary distance in relation to biological process being studied

- Documentation of selection rationale in research protocols and publications

Teleological Bias Awareness Protocol

Incorporating awareness of teleological reasoning into experimental design:

- Assumption auditing to identify implicit teleological statements in hypotheses

- Alternative explanation generation for biological functions without reference to human-centric purposes

- Historical contingency emphasis in evolutionary interpretations rather than optimal design narratives

Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Approaches

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Mitigating Anthropocentric Bias

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Bias Mitigation Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Organism Databases | ZFIN (zebrafish), FlyBase, WormBase | Genomic and phenotypic data across species | Facilitates informed selection beyond mammalian models |

| Comparative Genomics Platforms | UCSC Genome Browser, ENSEMBL | Cross-species sequence and functional comparison | Enables evolutionary context for human biology |

| Biological Icon Repositories | Bioicons, Phylopic, Noun Project | Standardized visual representations | Reduces anthropomorphic visualization in scientific communication |

| Organism Stock Centers | ATCC, Jackson Laboratory, CGC | Access to diverse model organisms | Supports practical implementation of comparative approaches |

Experimental Visualization: Mapping Anthropocentric Bias Assessment

Anthropocentric thinking and teleological reasoning represent deeply embedded cognitive patterns that systematically influence model organism selection and generalizability assessment in biological research [7] [20]. The experimental evidence demonstrates that these biases emerge developmentally and are modulated by cultural and educational factors [7] [22]. Addressing these challenges requires both individual-level awareness and structural methodological adjustments in research design and reporting practices. By implementing deliberative organism selection frameworks, comparative approaches, and explicit bias monitoring protocols, researchers can enhance the translational validity and biological generality of their findings while advancing a more scientifically rigorous approach to biological research beyond human-centric perspectives.

Essentialist biases are intuitive cognitive shortcuts that lead us to assume that categories in nature are defined by underlying, immutable "essences." These biases profoundly impact biological and biomedical research, particularly when researchers unconsciously assume that members of a biological category (e.g., a species, cell type, or emotional state) are more uniform than they actually are, thereby skewing experimental design and interpretation. This phenomenon is rooted in what developmental psychologists term intuitive teleology—the innate human tendency to explain phenomena by reference to purposes or ends, which emerges in early childhood and often persists into scientific thinking [10]. When researchers approach living systems with these pre-scientific assumptions, they may design experiments that fail to account for the inherent variability and context-dependency of biological processes, ultimately compromising research validity and reproducibility.

The core problem lies in what we might call the "uniformity fallacy"—the assumption that all instances of a biological category share identical properties, developmental pathways, or responses to experimental manipulations. This fallacy manifests across multiple domains of biological research, from assuming that a specific brain region consistently corresponds to the same emotional state across all individuals, to expecting that a particular genetic manipulation will yield identical phenotypic effects across a population. This paper examines how these essentialist biases emerge from intuitive teleological reasoning, documents their effects on experimental design across key domains, and provides practical methodological frameworks for mitigating their influence in scientific practice.

The Psychological Underpinnings: From Intuitive Teleology to Essentialist Biases

Developmental Origins and Persistence in Scientific Thinking

Research in cognitive development reveals that teleological explanations emerge early in human development. Children as young as 3-4 years routinely provide purpose-based explanations for natural phenomena, asserting that "things fell because they had to" or that "clouds exist to give rain" [10]. This intuitive teleology represents a fundamental mode of reasoning that appears across diverse cultural contexts and educational backgrounds. While this cognitive predisposition may have offered evolutionary advantages for rapid categorization and prediction, it becomes problematic when it persists unchallenged into scientific reasoning domains.

This teleological predisposition intertwines with what cognitive scientists term psychological essentialism—the intuitive belief that category members share underlying, immutable essences that determine their identity and properties. Studies demonstrate that this essentialist bias manifests specifically in reasoning about biological kinds, where individuals assume that innate traits must possess a special immutable essence that is physically embodied [23] [24]. For instance, when children reason about biological inheritance, they assert that a puppy inherits its brown color from its mother through the transfer of "tiny brown pieces of matter," localizing this essence within the material body [23] [24]. This embodied essentialism creates a powerful cognitive framework that shapes reasoning throughout development and into professional scientific practice.

The Embodiment-Innateness Fallacy in Experimental Design

The essentialist link between embodiment and innateness creates a specific cognitive bias that researchers term the "embodiment-innateness fallacy"—the incorrect inference that if a psychological trait is embodied (expressed in specific physical structures), it must therefore be innate [23] [24]. This fallacy has profound implications for experimental design across biological and psychological sciences. Research demonstrates that this link is not merely correlational but causal: when study participants were told that emotions were localized in specific brain areas, they were significantly more likely to conclude those emotions were innate, and this bias persisted even when participants were explicitly informed that the emotions were acquired through learning [24].

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for the Embodiment-Innateness Fallacy

| Experiment | Sample Size | Key Manipulation | Primary Finding | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | 60 participants | Ratings of emotion embodiment vs. innateness | Reliable correlation between perceived embodiment and innateness | p < .05 (exact value not reported) |

| Experiment 2 | 60 participants/group | Embodiment manipulation (brain localization) | Causal effect: embodied description increased innateness ratings | p < .05 (exact value not reported) |

| Experiment 3 | 60 participants/group | Explicit learning instruction | Bias persisted despite explicit counter-evidence | p < .05 (exact value not reported) |

This fallacy translates directly into experimental design flaws when researchers assume that biological localization (e.g., specific neural circuits, genetic loci, or biochemical pathways) indicates fixed, universal characteristics rather than context-dependent, variable processes. The following diagram illustrates the cognitive pathway through which intuitive teleology leads to experimental bias:

Domain-Specific Manifestations in Experimental Design

Neuroscience and Behavioral Research

In neuroscience research, the embodiment-innateness fallacy manifests when researchers assume that neural localization indicates functional universality. For instance, early research on emotions identified specific brain regions (like the amygdala for fear) and assumed these mappings were universal across all humans, designing experiments that failed to account for individual and cultural differences in emotional experience [23] [24]. This essentialist bias led to experimental designs that used overly simplistic stimuli, failed to control for cultural background, and interpreted results as revealing "hardwired" emotional circuits rather than potentially plastic, experience-dependent systems.

Essentialist biases also affect behavioral phenotyping in animal research. When researchers assume that a specific genetic manipulation will produce identical behavioral effects across all individuals, they often employ inadequate sample sizes that fail to capture true population variability. Studies have shown that this bias toward assuming uniformity leads to underpowered experiments that both overestimate effect sizes and fail to replicate across labs [25]. The solution involves designing experiments that explicitly model and account for sources of variation rather than assuming they are noise around a universal essence.

Molecular and Cellular Biology

In molecular biology, essentialist biases manifest as assumptions of cellular uniformity—that genetically identical cells in culture or tissue samples will exhibit identical molecular profiles under standardized conditions. This bias leads to experimental designs that pool samples without accounting for single-cell heterogeneity, potentially masking biologically significant subpopulations. Research has demonstrated that even clonal cell populations exhibit substantial phenotypic variability that can be critical for understanding drug resistance, differentiation capacity, and physiological responses.

Similarly, in genetics and genomics, essentialist biases appear when researchers assume that genes have fixed, context-independent functions—what historians of science term "gene essentialism." This leads to experimental designs that fail to account for pleiotropy, epistasis, and environmental influences on gene expression. For instance, early genome-wide association studies often assumed one-to-one mappings between genetic variants and phenotypic traits, neglecting the complex network interactions that characterize actual biological systems.

Quantifying the Impact: Data on Experimental Bias

The impact of essentialist biases on experimental outcomes can be quantified through methodological reviews and replication studies. While the search results don't provide comprehensive statistical data across all domains, they do offer indicative findings from specific research areas:

Table 2: Documented Impacts of Essentialist Biases on Research Quality

| Research Domain | Type of Bias | Impact on Research | Evidence Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Research | Embodiment-innateness fallacy | Persistent debate about universality vs. cultural construction of emotions | Multiple experimental studies [23] [24] |

| Evolution Education | Teleological reasoning | Conceptual obstacle to understanding natural selection | Developmental studies across age groups [10] |

| Experimental Design | Assumption of uniformity | Reduced reproducibility of preclinical research | Methodological reviews [25] |

| Neuroimaging | Localization assumption | Oversimplified mapping of cognitive functions | Analytical reviews of fMRI literature |

The methodological consequences of these biases are profound. Research into the reproducibility crisis in preclinical studies has identified unintentional biases in experimental planning and execution as major contributors to irreproducible findings [25]. Specifically, assumptions of uniformity lead to inadequate randomization, insufficient blinding, and inappropriate statistical analyses that assume normally distributed data without verifying this assumption.

Methodological Remedies: Countering Essentialist Biases

Experimental Design Framework

To counter essentialist biases in biological research, we propose a systematic framework for experimental design that explicitly incorporates anti-essentialist considerations:

This framework emphasizes several critical methodological adjustments. First, researchers should explicitly sample for heterogeneity rather than assuming uniformity—for example, by ensuring that animal models include both sexes, multiple genetic backgrounds, and varied environmental conditions when these factors represent meaningful biological variables rather than nuisance parameters [25]. Second, experimental designs should incorporate systematic randomization and blinding procedures to minimize unconscious bias in treatment allocation and outcome assessment, particularly when subjective judgments are involved in measurements.

Practical Implementation Toolkit

Implementing these methodological remedies requires specific practical tools and approaches. The following table outlines key resources for minimizing essentialist biases in experimental design:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Essentialist Biases

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Implementation Example | Bias Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blinding Protocols | Prevent observer bias | Code treatment groups; use third-party allocator | Confirmation bias in data collection |

| Systematic Random Sampling | Ensure representative sampling | Use random number generators for subject selection | Assumption of uniformity |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Verify experimental sensitivity | Include known responders and non-responders | Interpretation bias |

| Sample Size Justification | Ensure adequate power | Conduct power analysis based on pilot data | Underestimation of variability |

| Heterogeneity Modeling | Account for population variation | Include random effects in statistical models | Essentialist categorization |

Additionally, researchers should adopt heterogeneity-aware statistical models that explicitly represent rather than collapse across sources of variation. Mixed-effects models that include both fixed effects (experimental manipulations) and random effects (individual differences, batch effects, etc.) provide a more accurate representation of biological reality than models that assume homogeneous responses. Quality control measures should also include verification of measurement reliability across the expected range of biological variability, not just under optimal conditions.

Essentialist biases rooted in intuitive teleology present significant but addressable challenges to rigorous experimental design in biological and biomedical research. By recognizing the psychological underpinnings of these biases—particularly the embodied essentialism that links physical localization to assumptions of innateness and uniformity—researchers can implement methodological safeguards that produce more reliable, reproducible, and biologically valid findings. The frameworks and tools presented here provide a starting point for this methodological refinement, emphasizing strategic sampling, blinding, control procedures, and heterogeneity modeling as concrete antiodotes to essentialist assumptions. As the scientific community increasingly recognizes the costs of these cognitive biases, adopting these non-essentialist approaches will be crucial for advancing our understanding of complex, variable biological systems.

From Bias to Tool: Detecting and Harnessing Intuition in the R&D Pipeline

Teleological reasoning—the cognitive tendency to explain phenomena by reference to purposes, goals, or functions—represents a fundamental aspect of human cognition that influences understanding across scientific domains, particularly in biology and evolution. Research within the framework of intuitive teleological concepts about living beings requires rigorous methodological approaches for reliable assessment. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to established and emerging methods for documenting and measuring teleological reasoning in research populations, with specific application to studies involving scientists, educators, and drug development professionals. The assessment approaches detailed herein enable researchers to quantify the presence and strength of teleological biases, track conceptual change through educational interventions, and investigate the cognitive underpinnings of purpose-based reasoning about biological systems.

The critical importance of accurate assessment methodologies stems from the demonstrated impact of teleological reasoning on scientific understanding. Recent studies indicate that teleological biases persist even among scientifically literate populations and can significantly influence reasoning about natural phenomena [26]. Proper documentation and measurement of these cognitive tendencies provide essential data for developing targeted interventions, improving science communication, and understanding the conceptual foundations of biological reasoning among professionals in drug development and related fields.

Standardized Survey Instruments

Standardized surveys provide efficient, quantifiable measures of teleological reasoning tendencies across populations. The table below summarizes key validated instruments used in research settings.

Table 1: Standardized Survey Instruments for Teleological Reasoning Assessment

| Instrument Name | Construct Measured | Format & Sample Items | Reliability & Validity | Key Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief in Purpose of Random Events Survey | Tendency to ascribe purpose to unrelated life events | Participants rate agreement with statements linking unrelated events (e.g., "To what extent did the power outage happen in order to help you get a raise?") on Likert scales | Correlated with delusion-like ideas (r = 0.35-0.42); Strong discriminant validity | [27] [28] |

| Teleological Statements Scale | Endorsement of purpose-based explanations for natural phenomena | Forced-choice or agreement ratings with statements like "Rocks are pointy to prevent animals from sitting on them" | High internal consistency (α = .84); Predictive of natural selection understanding | [26] [29] |

| Inventory of Student Evolution Acceptance (I-SEA) | Acceptance of evolutionary theory dimensions | Measures acceptance of microevolution, macroevolution, and human evolution subscales | Validated with multiple student populations; High test-retest reliability | [26] |

| Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Understanding of natural selection mechanisms | Multiple-choice questions addressing key concepts like variation, inheritance, and selection | Established measure of evolutionary understanding; Pre-post sensitivity | [26] |

Survey implementation should follow established protocols to ensure data quality. Standardized administration procedures include clear instruction scripts, consistent response formats, and counterbalancing of items to control for order effects. For the Belief in Purpose of Random Events Survey, participants typically rate between 15-20 scenario pairs using 6-point Likert scales ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree," with higher scores indicating stronger teleological tendencies [27]. The Teleological Statements Scale often adapts items from Kelemen et al.'s (2013) instrument, which was originally used to demonstrate persistent teleological tendencies among physical scientists [26].

Analysis of survey data typically employs both composite scoring and factor analysis approaches. Composite scores provide an overall measure of teleological tendency, while factor analysis can reveal subdimensions such as external design teleology (attributing purpose to an intelligent designer) versus internal design teleology (attributing purpose to nature itself) [26]. These instruments have demonstrated sensitivity to change through educational interventions, with one study reporting significant decreases in teleological reasoning following explicit instruction (p ≤ 0.0001) [26].

Scenario-Based Experimental Protocols

Scenario-based experiments provide powerful tools for investigating the cognitive mechanisms underlying teleological reasoning through controlled presentation of stimuli and measurement of responses. The Kamin blocking paradigm, adapted from causal learning research, offers a particularly refined method for dissecting the associative learning components of teleological thought [27] [28].

Kamin Blocking Paradigm for Teleological Reasoning Assessment

The Kamin blocking paradigm tests an individual's tendency to form spurious associations between unrelated events—a cognitive process implicated in excessive teleological thinking. The experimental protocol involves a structured learning task typically implemented through computer-based presentation.

Table 2: Experimental Phases in the Kamin Blocking Paradigm

| Phase | Trials | Purpose | Sample Stimuli | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Learning | 6-8 trials | Establish outcome expectancies | Single food cues (I+, J+) paired with allergy outcomes; Compound cues (IJ+) with stronger outcomes | Baseline accuracy, Response times |

| Learning | 16-20 trials | Establish blocking cues | Cues A1, A2 paired with allergy outcomes; Cues C1, C2 paired with no allergy | Learning curves, Prediction accuracy |

| Blocking | 16-20 trials | Introduce redundant cues | Compound cues A1B1, A2B2 paired with same outcomes as A1, A2 alone; Controls C1D1, C2D2 | Blocking magnitude, Response patterns |