Theoretical Population Genomics Models: From Foundational Principles to Drug Development Applications

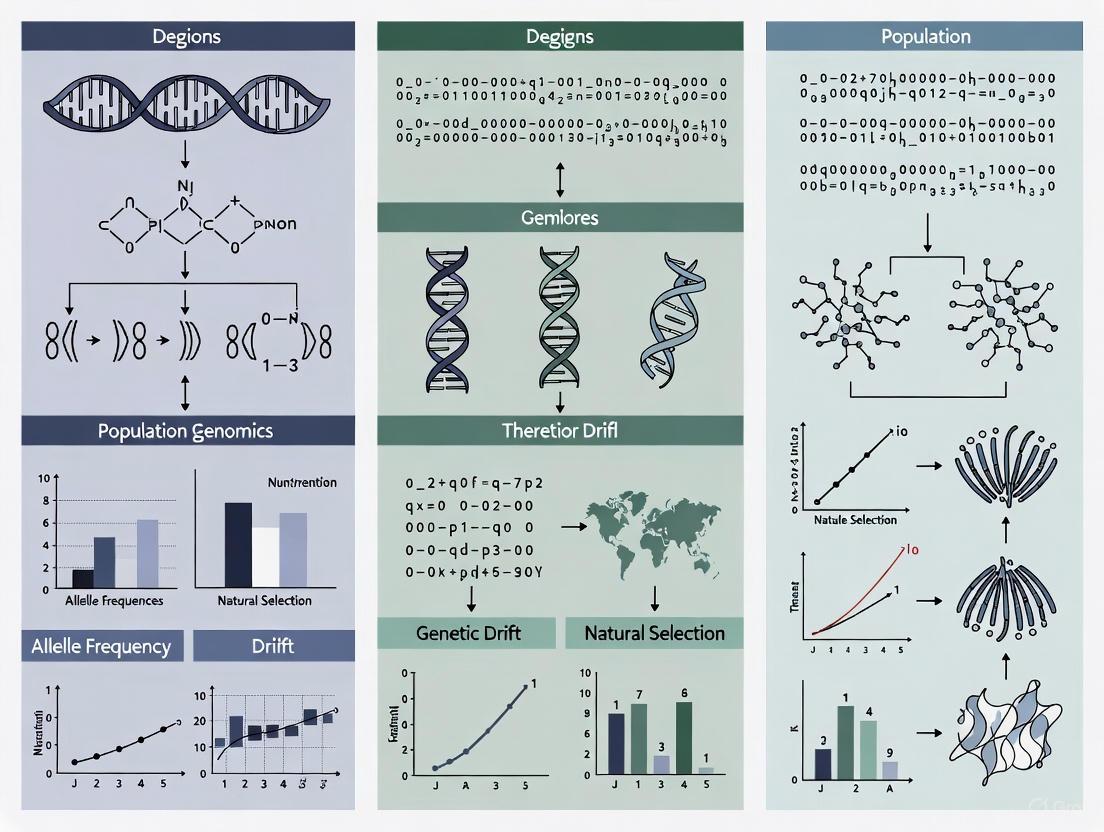

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of theoretical population genomics models, bridging foundational concepts with practical applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Theoretical Population Genomics Models: From Foundational Principles to Drug Development Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of theoretical population genomics models, bridging foundational concepts with practical applications in biomedical research and drug development. It begins by establishing the core principles of genetic variation and population parameters, then details key methodological approaches for inference and analysis. The content addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for model accuracy in real-world scenarios, and concludes with rigorous validation and comparative frameworks for benchmarking model performance. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current methodologies to enhance the application of population genomics in identifying causal disease genes and validating therapeutic targets, thereby potentially increasing drug development success rates.

Core Principles and Genetic Variation Patterns in Populations

This technical guide delineates three foundational parameters in theoretical population genomics: theta (θ), effective population size (Ne), and exponential growth rate (R). These parameters are indispensable for quantifying genetic diversity, modeling evolutionary forces, and predicting population dynamics. The document provides rigorous definitions, methodological frameworks for estimation, and visualizes the interrelationships between these core concepts, serving as a reference for researchers and scientists in genomics and drug development.

Theta (θ): The Population Mutation Rate

Theta (θ) is a cornerstone parameter in population genetics that describes the rate of genetic variation under the neutral theory. It is fundamentally defined by the product of the effective population size and the neutral mutation rate per generation. Theta is not directly observed but is inferred from genetic data, and several estimators have been developed based on different aspects of genetic variation [1].

Primary Definitions and Estimators of θ

| Estimator Name | Basis of Calculation | Formula | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Heterozygosity | Expected genetic diversity under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [1] | H = 4_N_ₑμ (for diploids) | Provides a theoretical expectation for within-population diversity. |

| Pairwise Nucleotide Diversity (π) | Average number of pairwise differences between DNA sequences [1] | π = 4_N_ₑμ | Directly calculable from aligned sequence data; reflects the equilibrium between mutation and genetic drift. |

| Watterson's Estimator (θ_w) | Number of segregating (polymorphic) sites in a sample [1] | θw = _K / aₙ where K is the number of segregating sites and aₙ is a scaling factor based on sample size n. | Useful when full sequence data is unavailable; based on the site frequency spectrum. |

Experimental Protocol: Estimating θ from Sequence Data

A standard methodology for estimating θ involves high-throughput sequencing and subsequent bioinformatic analysis [2].

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Collect tissue or blood samples from a representative set of individuals from the population of interest. Extract high-molecular-weight DNA.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare whole-genome sequencing libraries following standard protocols (e.g., Illumina). Sequence to an appropriate depth (e.g., 30x) to confidently call variants.

- Variant Calling: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome using tools like BWA or Bowtie2. Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) using variant callers such as GATK or SAMtools.

- Calculation of θ Estimators:

- For π: Use software like VCFtools or PopGen to calculate the average number of nucleotide differences between all possible pairs of sequences in the sample.

- For θw: Use the same software to count the total number of segregating sites (K) in your SNP dataset and apply the formula with the appropriate sample size scaling factor _aₙ.

Effective Population Size (Ne)

The effective population size (Nâ‚‘) is the size of an idealized population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift or inbreeding as the real population under study [1] [3]. It is a critical parameter because it determines the strength of genetic drift, the efficiency of selection, and the rate of loss of genetic diversity. The census population size (N) is almost always larger than Nâ‚‘ due to factors such as fluctuating population size, unequal sex ratio, and variance in reproductive success [1] [4].

Key Formulations and Factors Reducing Ne

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of Nâ‚‘ and the primary demographic factors that cause it to deviate from the census size.

Table: Common Formulas for Effective Population Size (Nâ‚‘)

| Scenario | Formula | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Variance in Reproductive Success [1] | Nâ‚‘^(v) = (4N - 2D) / (2 + var(k)) | N = census size; D = dioeciousness (0 or 1); var(k) = variance in offspring number. |

| Fluctuating Population Size (Harmonic Mean) [1] [4] | 1 / Nₑ = (1/t) * Σ (1 / Nᵢ) | t = number of generations; Nᵢ = census size in generation i. |

| Skewed Sex Ratio [4] | Nₑ = (4 * Nₘ * Nƒ) / (Nₘ + Nƒ) | Nₘ = number of breeding males; Nƒ = number of breeding females. |

Experimental Protocol: Estimating Ne via Temporal Method

The temporal method, which uses allele frequency changes over time, is a powerful approach to estimate Nâ‚‘ [4].

- Study Design: Collect genetic samples from the same population at two or more distinct time points (e.g., generations tâ‚€ and tâ‚). The number of generations between samples should be known.

- Genotyping: Genotype all samples at a set of neutral, independently segregating markers (e.g., microsatellites or SNPs).

- Allele Frequency Calculation: Calculate the allele frequencies for each marker in each temporal sample.

- Variance Calculation: For each allele, compute the variance in its frequency change between time points. The average variance across all alleles is used as

var^(p)in the formula below. - Estimation: Calculate the variance effective size using the formula [1]:

Nâ‚‘^(v) = p(1-p) / (2 *

var^(p)) where p is the initial allele frequency. This calculation is typically performed using specialized software like NeEstimator or MLNE, which account for sampling error and use maximum likelihood or Bayesian approaches.

Exponential Growth Rate (R)

Exponential growth occurs when a population's instantaneous rate of change is directly proportional to its current size, leading to growth that accelerates over time. The growth rate R (often denoted as r in ecology) quantifies this per-capita rate of increase [5]. While rapid exponential growth is unsustainable in the long term in natural populations, the model is crucial for describing initial phases of population expansion, bacterial culture growth, or viral infection spread [5].

Mathematical Formulations and Population Impact

The core mathematical expression for exponential growth and its key derivatives are summarized below.

Table: Key Formulas for Exponential Growth

| Parameter | Formula | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Discrete Growth [5] | x({}{t}) = _xâ‚€(1 + R)({}^{t}) | xâ‚€ = initial population size; R = growth rate per time interval; t = number of time intervals. |

| Continuous Growth [5] [6] | x(t) = xâ‚€ * e({}^{R*t} | e is the base of the natural logarithm (~2.718). |

| Doubling Time [5] | T({}{double}) = ln(2) / _R ≈ 70 / (100*R) | The "Rule of 70" provides a quick approximation for the time required for the population to double in size. |

The following diagram illustrates how exponential growth influences genomic diversity, a key consideration in population genomic models.

Experimental Protocol: Inferring Historical Growth from Genetic Data

Demographic history, including periods of exponential growth, can be inferred from genomic data using coalescent-based models [1].

- Data Generation: Obtain whole-genome sequence data from a random sample of individuals from the population. High-quality, high-coverage data is preferred.

- Site Frequency Spectrum (SFS) Construction: Calculate the SFS, which is a histogram of allele frequencies in the sample. This spectrum summarizes the proportion of sites with derived alleles found in 1, 2, 3, ..., n-1 of the n chromosomes.

- Model Selection and Fitting: Use software such as ∂a∂i (for allele frequency data) or BEAST (for phylogenetic trees) to fit a demographic model that includes an exponential growth parameter (R or a related parameter like growth rate g). The software compares the observed SFS to SFSs generated under different models and parameters.

- Parameter Estimation: The fitting algorithm (e.g., maximum likelihood or Bayesian inference) will estimate the value of R that best explains the observed genetic data, along with other parameters like the timing of the growth and the initial population size.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Population Genomic Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Critical for accurate PCR amplification during library preparation for sequencing and genotyping of molecular markers like microsatellites and SNPs [2]. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Kit | (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq). Provides the raw sequence data required for estimating θ, inferring demography, and calling variants for Nₑ estimation [2]. |

| SNP Genotyping Array | A cost-effective alternative to WGS for scoring hundreds of thousands to millions of SNPs across many individuals, useful for estimating Nâ‚‘ and genetic diversity [2]. |

| Bioinformatics Software (e.g., GATK, VCFtools, ∂a∂i, BEAST) | Software suites for variant calling, data quality control, and demographic inference. They are essential for transforming raw sequence data into estimates of θ, Nₑ, and R [1] [2]. |

| Tin tetrabutanolate | Tin Tetrabutanolate|CAS 14254-05-8|Supplier |

| (S)-(-)-Nicotine-15N | (S)-(-)-Nicotine-15N|High-Purity Isotope for Research |

In the field of theoretical population genomics, understanding the processes that shape the distribution of genetic variation is fundamental. Two predominant models explaining patterns of genetic differentiation are Isolation by Distance (IBD) and Isolation by Environment (IBE). IBD describes a pattern where genetic differentiation between populations increases with geographic distance due to the combined effects of limited dispersal and genetic drift [7]. In contrast, IBE describes a pattern where genetic differentiation increases with environmental dissimilarity, independent of geographic distance, often as a result of natural selection against migrants or hybrids adapted to different environmental conditions [8]. Disentangling the relative contributions of these processes is crucial for understanding evolutionary trajectories, local adaptation, and for informing conservation strategies [9] [10]. This guide provides a technical overview of the theoretical foundations, methodologies, and applications of IBD and IBE for researchers and scientists.

Theoretical Foundations and Prevalence

Core Concepts and Definitions

Isolation by Distance (IBD) is a neutral model grounded in population genetics theory. It posits that gene flow is geographically limited, leading to a positive correlation between genetic differentiation and geographic distance. This pattern arises from the interplay of localized dispersal and genetic drift, which creates a genetic mosaic across the landscape [7]. The model was initially formalized by Sewall Wright, who showed that limited dispersal leads to genetic correlations among individuals based on their spatial proximity.

Isolation by Environment (IBE) is a non-neutral model that emphasizes the role of environmental heterogeneity in driving genetic divergence. IBE occurs when gene flow is reduced between populations inhabiting different environments, even if they are geographically close. This can result from several mechanisms, including:

- Natural selection against maladapted immigrants.

- Biased dispersal toward familiar environments.

- Natural or sexual selection against hybrids [8]. IBE can affect both adaptive loci and, through processes like genetic hitchhiking, neutral loci across the genome [9].

Relative Prevalence of IBD and IBE

A survey of 70 studies found that IBE is a common driver of genetic differentiation, underscoring the significant role of environmental selection in shaping population structure [11].

Table 1: Prevalence of Isolation Patterns across Studies

| Pattern of Isolation | Prevalence in Studies (%) | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|

| Isolation by Environment (IBE) | 37.1% | Genetic differentiation is primarily driven by environmental differences [11]. |

| Both IBE and IBD | 37.1% | Both geographic distance and environment contribute significantly to genetic differentiation [11]. |

| Isolation by Distance (IBD) | 20.0% | Genetic differentiation is primarily driven by geographic distance [11]. |

| Counter-Gradient Gene Flow | 10.0% | Gene flow is highest among dissimilar environments, a potential "gene-swamping" scenario [11]. |

The combined data shows that 74.3% of studies exhibited significant IBE patterns, suggesting it is a predominant force in nature and refuting the idea that gene swamping is a widespread phenomenon [11].

Methodological Approaches for Disentangling IBD and IBE

Experimental Design and Data Collection

Robust testing for IBD and IBE requires data on population genetics, geographic locations, and environmental variables.

- Genetic Data: Studies commonly use genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [8] or other molecular markers like inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSRs) [9] to estimate genetic differentiation.

- Geographic Data: Precise geographic coordinates for all sampled populations are essential for calculating geographic distance matrices.

- Environmental Data: Climatic and edaphic variables (e.g., precipitation seasonality, temperature, soil pH) are obtained from field measurements or geographic information systems (GIS) [9] [8].

Statistical Frameworks and Analysis

The following statistical protocols are used to partition the effects of IBD, IBE, and other processes.

Protocol 1: Partial Mantel Tests and Maximum Likelihood Population Effects (MLPE) Models

- Purpose: To test the correlations between genetic distance, geographic distance, and environmental distance while controlling for the covariance between predictors.

- Procedure:

- Compute pairwise matrices for genetic distance (e.g., ( F_{ST} )), geographic distance (Euclidean or resistance-based), and environmental distance (e.g., Euclidean distance of standardized climate variables).

- Perform a partial Mantel test to assess the correlation between genetic and environmental distance while controlling for geographic distance, and vice versa.

- Use MLPE models, a linear mixed-modeling approach, to compare the support for IBD, IBE, and IBR (Isolation by Resistance) models, which account for non-independence of pairwise data [9].

- Application: This method identified winter and summer precipitation as the main drivers of genetic differentiation in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus, supporting a primary IBE pattern [9] [12].

Protocol 2: Variance Partitioning via Redundancy Analysis (RDA)

- Purpose: To quantify the unique and shared contributions of geographic distance (IBD), environmental factors (IBE), and landscape barriers (IBB) to genetic variation.

- Procedure:

- Perform data preparation and compute pairwise genetic distance matrices from neutral genetic markers.

- Define predictor variable groups: geographic distances, environmental distances, and resistance distances.

- Run a series of RDAs with the genetic data as the response variable and the distance matrices as predictors.

- Calculate the adjusted ( R^2 ) for each set of predictors to partition the variance into unique and shared components [10].

- Application: This approach revealed that for the plains pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius), a major river acted as a barrier explaining the most genetic variation (IBB), while geographic distance (IBD) was most important for a subspecies, and soil properties contributed a smaller, unique effect (IBE) [10].

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for designing studies and analyzing data to distinguish between Isolation by Distance (IBD) and Isolation by Environment (IBE).

Research Reagent and Computational Toolkit

A successful study requires both wet-lab reagents for genetic data generation and dry-lab computational tools for analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for IBD/IBE Studies

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Markers | ||

| Genome-wide SNPs | [8] | High-resolution genotyping for estimating genetic diversity and differentiation. |

| Microsatellites | [10] | Co-dominant markers useful for population-level studies. |

| ISSR (Inter-Simple Sequence Repeats) | [9] | Dominant, multilocus markers for assessing genetic variation. |

| Software for Analysis | ||

PLINK |

[13] | Whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses; includes IBD detection. |

GERMLINE |

[13] | Efficient, linear-time detection of IBD segments in pairs of individuals. |

BEAGLE/RefinedIBD |

[13] | Detects IBD segments using a hashing method and evaluates significance via likelihood ratio. |

R packages (e.g., vegan, adegenet) |

[9] [8] [10] | Statistical environment for performing Mantel tests, RDA, and other spatial genetic analyses. |

| Ned-K | Ned-K, MF:C31H31N5O3, MW:521.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ATTO488-ProTx-II | ATTO488-ProTx-II is a fluorescently labeled, high-affinity blocker for Nav1.7 channels. This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. |

Case Studies in Plants and Animals

Plant Systems

Case Study: Ammopiptanthus mongolicus

- Background: This endangered desert shrub was previously thought to exhibit IBD.

- Methods: Researchers used ISSR markers on 10 populations and analyzed data with partial Mantel tests and MLPE models.

- Findings: Genetic differentiation was primarily driven by climate differences (IBE), specifically summer and winter precipitation, rather than geographic distance (IBD). This led to a conservation recommendation focused on collecting germplasm from differentiated populations rather than creating connectivity corridors [9] [12].

Case Study: Arabidopsis thaliana

- Background: A model organism used to study genetic structure across the Iberian Peninsula.

- Methods: Analysis of 1772 individuals from 278 populations using genome-wide SNPs.

- Findings: Both IBD and IBE were significant drivers of genetic differentiation, with precipitation seasonality and topsoil pH being key environmental factors. The relative importance of these drivers varied among distinct genetic clusters within the region [8].

Animal Systems

Case Study: Plains Pocket Gopher (Geomys bursarius)

- Background: A subterranean rodent with a wide distribution across the Great Plains.

- Methods: Variance partitioning with microsatellite data was used to separate the effects of IBB, IBD, and IBE.

- Findings: At the species level, a major river (IBB) was the strongest isolating factor. For the subspecies G. b. illinoensis, IBD was the dominant pattern. IBE, associated with soil sand percent and color (likely related to burrowing costs and crypsis), explained a smaller but significant portion of genetic variance [10].

Figure 2: A conceptual diagram showing the primary evolutionary forces and their mechanisms behind IBD and IBE, with example outcomes from key case studies.

Implications for Conservation and Management

Identifying whether IBD or IBE is the dominant pattern has direct, and often divergent, implications for conservation policy and management.

When IBE is Dominant: Conservation efforts should prioritize preserving genetic diversity across different environmental gradients. For A. mongolicus, this meant that collecting germplasm resources from genetically differentiated populations was a more effective strategy than establishing corridors to enhance gene flow [9]. This "several-small" approach conserves locally adapted genotypes.

When IBD is Dominant: Conservation should focus on maintaining landscape connectivity to facilitate natural gene flow between neighboring populations. This aligns with a "single-large" strategy, as genetic diversity is maintained through proximity and gene flow [9] [10].

Integrated Management: Many systems, like A. thaliana and the pocket gopher, show hierarchical structuring where different processes dominate at different spatial scales [8] [10]. Management must therefore be scale-aware, considering major barriers (IBB) at a regional scale while also addressing fine-scale environmental adaptation (IBE) and dispersal limitation (IBD).

Demographic processes are fundamental forces shaping the genetic architecture of populations. Theoretical population genomics relies on models that integrate these demographic forces—bottlenecks, expansions, and genetic drift—to interpret patterns of genetic variation and make inferences about a population's history [14]. These forces directly affect key genetic parameters, including the loss of genetic diversity, increased homozygosity, and the accumulation of deleterious mutations, which can reduce a population's evolutionary potential and its ability to adapt to environmental change [15]. Understanding these impacts is crucial not only for conservation biology and evolutionary studies but also for the design of robust genetic association studies in drug development, where unrecognized population structure can confound the identification of genuine disease-susceptibility genes [14]. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the mechanisms, measurement, and consequences of these demographic events, framed within contemporary research in theoretical population genomics.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Genetic Foundations

Genetic Drift, Effective Population Size, and Variance

Genetic drift describes the random fluctuation of allele frequencies in a population over generations. Its intensity is inversely proportional to the effective population size (Ne), a key parameter in population genetics that determines the rate of loss of genetic diversity and the efficacy of selection. The fundamental variance in allele frequency change due to genetic drift from one generation to the next is given by:

σ2Δq = pq / 2Ne

where p and q are allele frequencies [16]. This equation highlights that smaller populations experience stronger drift, leading to rapid fixation or loss of alleles and a consequent reduction in heterozygosity at a rate of 1/(2Ne) per generation.

Partitioning Genetic Variance

In quantitative genetics, the genetic variance (σ²G) of a trait can be partitioned into additive (σ²A) and dominance (σ²D) components, expressed as σ²G = σ²A + σ²D [16]. The additive genetic variance is the primary determinant of a population's immediate response to selection and is therefore critical for predicting evolutionary outcomes. Demographic events drastically alter these variance components. The additive genetic variance is a function of allele frequencies (p, q) and the average effect of gene substitution (α), defined as σ²A = 2pqα² [16]. Population bottlenecks and expansions cause rapid shifts in allele frequencies, directly impacting σ²A and, consequently, the evolutionary potential of a population.

Demographic Events: Mechanisms and Genetic Consequences

Population Bottlenecks

A population bottleneck is a sharp, often temporary, reduction in population size. The severity of a bottleneck is determined by its duration and the minimum number of individuals, which dictates the extent of genetic diversity loss and the strength of genetic drift [17] [15].

- Mechanism and Genetic Consequences: During a bottleneck, the small number of surviving individuals represents only a small fraction of the original population's gene pool. This leads to a sudden drop in heterozygosity and the possible loss of rare alleles. Following the bottleneck, genetic diversity remains low and can only be restored slowly through mutation or via gene flow from other populations [15]. Furthermore, the increased rate of inbreeding in small populations can lead to inbreeding depression, reducing fitness [15].

- Examples from Research:

- Northern Elephant Seals: Hunted to a mere ~20 individuals in the 1890s. Despite a recovery to over 30,000 individuals, they exhibit drastically reduced genetic variation compared to closely related species that did not experience such intense hunting [17] [15].

- Sophora moorcroftiana: Genomic analysis of this Tibetan shrub revealed distinct subpopulations that underwent severe bottlenecks. The subpopulation P1 (Gongbu Jiangda County) showed the lowest genetic diversity (Ï€ = 1.1 × 10â»â´) and the smallest effective population size, a clear genetic signature of a past bottleneck [18].

Table 1: Quantified Genetic Consequences of Documented Population Bottlenecks

| Species | Bottleneck Severity | Key Genetic Metric | Post-Bottleneck Value | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Elephant Seal | Reduced to ~20 individuals | Genetic Diversity (vs. Southern seals) | Much lower | [17] [15] |

| Sophora moorcroftiana (P1) | Severe bottleneck | Nucleotide Diversity (Ï€) | 1.1 × 10â»â´ | [18] |

| Wollemi Pine | < 50 mature individuals | Genetic Diversity | Nearly undetectable | [15] |

| Greater Prairie Chicken | 100 million to 46 (in Illinois) | Genetic Decline (DNA analysis) | Steep decline | [15] |

Founder Effects

A founder effect is a special case of a bottleneck that occurs when a new population is established by a small number of individuals from a larger source population. The new colony is characterized by reduced genetic variation and a gene pool that is a non-representative sample of the original population [17].

- Mechanism and Genetic Consequences: The founding group carries only a small, random subset of the alleles from the parent population. This can lead to the rapid emergence of rare diseases in the new population if the founders by chance carry deleterious alleles. An iconic example is the Afrikaner population in South Africa, which has an unusually high frequency of the gene causing Huntington's disease due to its high prevalence among the few original Dutch colonists [17].

Population Expansions

Population expansions occur when a population experiences a significant increase in size, often following a bottleneck or after colonizing new habitats. While expansions increase the absolute number of individuals and mutation supply, they leave a distinct genetic signature.

- Mechanism and Genetic Consequences: A rapid expansion from a small founder population can create a genome-wide pattern of rare, low-frequency alleles due to the influx of new mutations in the growing population. Analysis of Sophora moorcroftiana subpopulations using SMC++ analyses demonstrated that the species' demographic history was marked not only by bottlenecks but also by population expansion events, likely driven by glacial-interglacial cycles and geological events [18].

Interaction of Demography with Selection

Demographic history profoundly influences the effectiveness of natural selection. In large, stable populations, selection is efficient at removing deleterious alleles and fixing beneficial ones. In populations undergoing repeated bottlenecks or founder events, however, genetic drift can overpower selection. This can lead to the random fixation of slightly deleterious alleles, a process known as the "drift load," reducing the mean fitness of the population [15]. This is a critical consideration in conservation and biomedical genetics, as small, isolated populations may accumulate deleterious genetic variants.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between different demographic events and their primary genetic consequences.

Diagram 1: Logical flow from demographic events to genetic consequences. Bottlenecks and founder effects trigger strong genetic drift and reduce Ne, leading to a cascade of negative genetic outcomes.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Modern population genomics employs a suite of computational and statistical tools to detect and quantify the impact of past demographic events.

Inferring Population Structure and Demography

Protocol 1: Population Genomic Analysis for Demographic Inference

- Sample Collection and Sequencing: Collect tissue samples (e.g., leaves, blood) from multiple individuals across the species' geographic range. For plants, formally identify species and deposit voucher specimens in a herbarium [18].

- Genotyping: Perform high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Whole-Genome Sequencing, Genotyping-by-Sequencing [GBS]) to generate genome-wide data. Align sequence reads to a reference genome and perform variant calling to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [18].

- Population Genomic Statistics:

- Calculate genetic diversity within populations (e.g., nucleotide diversity, π).

- Estimate genetic differentiation between populations (e.g., F-statistics, FST). The Sophora study found an average FST of 0.2477 for the most differentiated subpopulation [18].

- Analyze population structure using algorithms like ADMIXTURE, STRUCTURE, or PCA [19].

- Demographic History Modeling:

Protocol 2: Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) Analysis

- Environmental Data Collection: Gather geo-referenced environmental data (e.g., altitude, temperature, precipitation) for each sample location [18].

- Statistical Testing: Perform genotype-environment association analyses (e.g., using RDA, BayPass, or LFMM) to identify SNPs whose frequencies are significantly correlated with environmental variation [18].

- Gene Annotation: Annotate significant SNPs to identify candidate genes involved in local adaptation, which may have been targets of selection during demographic shifts. The Sophora study annotated 55 significant SNPs to 20 candidate genes [18].

Visualization and Analysis Toolkit

The complexity of genomic data necessitates advanced visualization platforms. PopMLvis is an interactive tool designed to analyze and visualize population structure using genotype data from GWAS [19]. Its functionalities include:

- Input Flexibility: Accepts raw genotype data, principal components, and admixture coefficient matrices.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Performs PCA, t-SNE, and PC-Air (which accounts for relatedness).

- Clustering and Outlier Detection: Integrates K-means, Hierarchical Clustering, and machine learning-based outlier detection.

- Interactive Visualization: Generates scatter plots, admixture bar charts, and dendrograms for publication-ready figures [19].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Population Genomic Studies

| Item/Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBS / WGS Library Prep | Wet-lab Kit | High-throughput sequencing to generate genome-wide SNP data | Genotyping of non-model organisms [18] |

| Reference Genome | Data | A sequenced and annotated genome for read alignment and variant calling | Essential for accurate SNP calling and annotation [18] |

| VCFtools / BCFtools | Software | Filtering and manipulating variant call format (VCF) files | Pre-processing of SNP data before analysis [19] |

| ADMIXTURE | Software | Model-based estimation of individual ancestries from multi-locus SNP data | Inferring population structure and admixture proportions [19] |

| SMC++ | Software | Inferring population size history from whole-genome data | Detecting historical bottlenecks and expansions [18] |

| R/qtl / BayPass | Software | Identifying correlations between genetic markers and environmental variables | Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) analysis [18] |

| PopMLvis | Web Platform | Interactive visualization of population structure results from multiple algorithms | Integrating and interpreting clustering and ancestry results [19] |

| BDS-I | BDS-I, MF:C210H297N57O56S6, MW:4708.37 Da | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Azidoethanol-d4 | 2-Azidoethanol-d4, MF:C₂HD₄N₃O, MW:91.11 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for a population genomic study, from sampling to demographic inference.

Diagram 2: A workflow for population genomic analysis to infer demographic history, from sampling to synthesis.

Demographic processes—bottlenecks, expansions, and the persistent force of genetic drift—are inseparable from the patterns of genetic variation observed in natural populations. The integration of theoretical population genetics with modern genomic technologies allows researchers to reconstruct a population's history with unprecedented detail, revealing how past climatic events, geological upheavals, and human activities have shaped genomes. For drug development professionals, a rigorous understanding of these dynamics is critical. Unaccounted-for population structure can create spurious associations in genetic association studies, while a thorough characterization of demographic history can help isolate true signals of adaptive evolution and identify genetic variants underlying complex diseases. As genomic datasets grow in size and complexity, the continued refinement of demographic models and analytical tools will be essential for accurately interpreting the genetic tapestry of life.

Functional genomics provides the critical methodological bridge that connects static genomic sequences (genotype) to observable characteristics (phenotype), a central challenge in modern biology. Framed within theoretical population genomics models, this discipline leverages statistical and computational tools to understand how evolutionary processes like mutation, selection, and drift shape the genetic underpinnings of complex traits. This whitepaper details the core principles, methodologies, and analytical frameworks that empower researchers to map and characterize the functional elements of genomes, thereby illuminating the path from genetic variation to phenotypic diversity and disease susceptibility.

The relationship between genotype and phenotype is foundational to evolutionary biology and genetics. Historically, geneticists sought to understand the processing of gene expression into phenotypic design without the molecular tools available today [20]. The core challenge lies in the fact that this relationship is rarely linear; it is shaped by complex networks of gene interactions, regulation, and environmental factors. Theoretical population genomics provides the models to understand how these functional links evolve—how natural selection acts on phenotypic variation that has a heritable genetic basis, and how demographic history and genetic drift shape the architecture of complex traits.

Functional genomics addresses this by systematically identifying and characterizing the functional elements within genomes. It moves beyond correlation to causation, asking not just where genetic variation occurs, but how it alters molecular functions and, ultimately, organismal phenotypes. This guide outlines the key experimental and computational protocols that make this possible, with a focus on applications in biomedical and evolutionary research.

Methodological Foundations: Key Experimental Protocols

The following section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments that link genotype to phenotype, from data acquisition to functional validation.

Genomic Data Acquisition and Analysis Using Public Browsers

Principle: Public genome browsers are indispensable for initial genomic annotation and comparison. They provide reference genomes and annotated features (genes, regulatory elements, variants) for a wide range of species, enabling researchers to contextualize their genomic data [21].

Protocol 1: Genome Identification and Annotation via ENSEMBL

- Aim: To annotate and compare a genomic sequence of interest against a reference database.

- Method: [21]

- Navigate to the ENSEMBL website (e.g.,

https://asia.ensembl.org). - Input the genomic sequence (e.g., from a test organism) or the name of the organism.

- Utilize integrated tools such as BLAST or BLAT for sequence alignment.

- Use the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) to annotate and predict the functional consequences of genetic variants.

- Browse the genomic landscape to identify genes, regulatory regions, and homologous sequences.

- Navigate to the ENSEMBL website (e.g.,

- Results: Save the annotated data for downstream analysis. The output provides a preliminary functional annotation of the genomic region.

Protocol 2: Comparative Genomics and Evolutionary Analysis via UCSC Genome Browser

- Aim: To visualize a genomic region and its evolutionary conservation across species.

- Method: [21]

- Access the UCSC Genome Browser (

https://genome.ucsc.edu). - Select the relevant genome assembly and input the genomic coordinates or sequence.

- Enable comparative genomics tracks, such as conservation scores (e.g., PhastCons, PhyloP) and multiple sequence alignments.

- Analyze the data to identify evolutionarily constrained regions, which are putative functional elements.

- Access the UCSC Genome Browser (

- Results: Save conservation scores and multiple alignment data. Highly conserved non-coding elements often indicate regulatory function.

Functional Validation via Genomic Perturbation

Principle: Establishing causality requires experimental perturbation of a genetic element and observation of the phenotypic consequence. This protocol outlines a general workflow for functional validation.

- Aim: To determine the phenotypic impact of a specific genetic variant or gene.

- Method:

- Target Identification: Based on GWAS or QTL mapping, select a candidate gene or non-coding variant for testing.

- Perturbation Design:

- For coding genes: Design CRISPR-Cas9 guides for gene knockout or use RNAi for knockdown.

- For non-coding variants: Use base-editing or prime-editing to introduce the specific allele in an isogenic background.

- Delivery: Introduce the perturbation construct into the target cell line (e.g., via transfection) or model organism (e.g., via microinjection).

- Phenotypic Screening: Assay for relevant phenotypic changes.

- Molecular Phenotypes: RNA-seq (transcriptome), ATAC-seq (chromatin accessibility), proteomics.

- Cellular Phenotypes: Cell proliferation, migration, or apoptosis assays.

- Organismal Phenotypes: Morphological, physiological, or behavioral assessments.

- Results: A significant change in the assayed phenotype upon genetic perturbation confirms a functional link between the genotype and phenotype.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the core iterative process of linking genotype to phenotype.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful functional genomics research relies on a suite of essential reagents and computational tools. The table below details key resources for major experimental workflows.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Functional Genomics

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| ENSEMBL Browser [21] | Genome annotation, variant analysis, and comparative genomics. | Integrated tools like BLAST, BLAT, and the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP). |

| UCSC Genome Browser [21] | Visualization of genomic data and evolutionary conservation. | Customizable tracks for conservation (PhastCons), chromatin state (ENCODE), and more. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted gene knockout or editing for functional validation. | High precision and programmability for disrupting genetic elements. |

| RNAi Libraries | High-throughput gene knockdown screens. | Allows for systematic silencing of genes to assess phenotypic impact. |

| Bulk/Single-Cell RNA-seq | Profiling gene expression across samples or cell types. | Quantifies transcript abundance, identifying expression QTLs (eQTLs). |

| ATAC-seq | Assaying chromatin accessibility and open chromatin regions. | Identifies active regulatory elements (e.g., promoters, enhancers). |

| Statistical Genomics Tools [22] | Computational analysis of genomic data sets. | Provides protocols for QTL mapping, association studies, and data integration. |

| CYT387-azide | CYT387-azide|JAK Inhibitor Probe|Research Use Only | CYT387-azide is a functionalized JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor for synthesizing bioconjugates. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. |

Data Integration and Analysis: A Quantitative Framework

Integrating data from multiple genomic layers is essential for a holistic view. The following table provides a comparative overview of key quantitative data types and their analytical interpretations within population genomics models.

Table 2: Quantitative Data Types and Their Interpretation in Functional Genomics

| Data Type | Typical Measurement | Population Genomics Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Strength | Composite Likelihood Ratio (e.g., CLR test) | Identifies genomic regions under recent positive or balancing selection. |

| Population Differentiation | FST (Fixation Index) | Highlights loci with divergent allele frequencies between populations, suggesting local adaptation. |

| Allele Frequency Spectrum | Tajima's D | Deviations from neutral expectations can indicate population size changes or selection. |

| Variant Effect | Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) Score | Prioritizes deleterious functional variants likely to impact phenotype. |

| Expression Heritability | Expression QTL (eQTL) LOD Score | Quantifies the genetic control of gene expression levels. |

| Genetic Architecture | Number of loci & Effect Size Distribution | Informs whether a trait is controlled by few large-effect or many small-effect variants. |

Analytical Framework: From Data to Biological Insight

The path from raw genomic data to a validated genotype-phenotype link requires a structured analytical pipeline. The following diagram visualizes this multi-step computational and experimental workflow, which is central to functional genomics.

Functional genomics has transformed our ability to decipher the functional code within genomes, moving from associative links to causal mechanisms underlying phenotypic variation. The integration of these approaches with theoretical population genomics models is crucial for understanding the evolutionary forces that have shaped these links. Looking ahead, the field is moving towards the widespread adoption of multiomics, which integrates data from genomics, transcriptomics, epigenetics, and proteomics [23]. This integrated approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of molecular changes and is expected to drive breakthroughs in drug development and improve patient outcomes. Furthermore, advancements in population genomics, including the collection of diverse genetic datasets and the application of whole genome sequencing in clinical diagnostics (e.g., for cancer and tuberculosis), hold transformative potential for personalized medicine [23]. As these technologies mature, they will further illuminate the intricate path from genotype to phenotype, empowering researchers and clinicians to better predict, diagnose, and treat complex diseases.

Key Models and Their Application in Genomic Selection and Drug Discovery

Genomic Selection (GS) is a revolutionary methodology in modern breeding and genetic research that enables the prediction of an individual's genetic merit based on dense genetic markers covering the entire genome. First conceptualized by Meuwissen, Hayes, and Goddard in 2001, GS represents a fundamental shift from marker-assisted selection (MAS) by utilizing all marker information simultaneously, thereby capturing both major and minor gene effects contributing to complex traits [24] [25]. This approach has become standard practice in major dairy cattle, pig, and chicken breeding programs worldwide, providing multiple quantifiable benefits to breeders, producers, and consumers [26]. The core principle of GS involves first estimating marker effects based on genotypic and phenotypic values of a training population, then applying these estimated effects to compute genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for selection candidates in a test population having only genotypic information [24]. This allows for selection decisions at an early growth stage, significantly reducing breeding time and costs, particularly for traits that express later in life or are costly to phenotype [24].

The accuracy of GEBVs is paramount to the success of genomic predictions and is influenced by several factors including trait heritability, marker density, quantitative trait loci (QTL) number, linkage disequilibrium between QTL and associated markers, size of the reference population, and genetic relationship between reference and test populations [24] [27]. With the advent of low-cost genotyping technologies such as single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays and genotyping by sequencing, GS has become increasingly accessible, enabling more efficient breeding programs across animal and plant species [24].

Theoretical Foundations of Genomic Selection Models

Statistical Framework

Genomic selection methods can be broadly classified into parametric, semi-parametric, and non-parametric approaches [24] [27]. Parametric methods assume specific distributions for genetic effects and include BLUP (Best Linear Unbiased Prediction) alphabets and Bayesian alphabets. Semi-parametric methods include approaches like reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS), while non-parametric methods comprise mostly machine learning techniques [24]. The fundamental statistical model for genomic prediction can be represented as:

y = 1μ + Xg + e

Where y is the vector of phenotypes, μ is the overall mean, X is the matrix of genotype indicators, g is the vector of random marker effects, and e is the vector of residual errors [28]. In this model, the genomic estimated breeding value (GEBV) for an individual is calculated as the sum of all marker effects according to its marker genotypes [28].

The differences between various GS methods primarily lie in the assumptions regarding the distribution of marker effects and how these effects are estimated [24]. These methodological differences lead to varying performance across traits with different genetic architectures, making the selection of an appropriate statistical model crucial for accurate genomic prediction.

Key Methodological Distinctions

The BLUP and Bayesian approaches differ fundamentally in their treatment of marker effects. BLUP alphabets assume all markers contribute to trait variability, with marker effects following a normal distribution, implying that many QTLs govern the trait, each with small effects [24]. In contrast, Bayesian methods assume only a limited number of markers have effects on trait variance, with different prior distributions specified for different Bayesian models [24]. Additionally, BLUP methods assign equal variance to all markers, while Bayesian methods assign different weights to different markers, allowing for variable contributions to the genetic variance [24].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between BLUP and Bayesian Approaches

| Feature | BLUP Alphabets | Bayesian Alphabets |

|---|---|---|

| Method Type | Linear parametric | Non-linear parametric |

| Marker Effect Assumption | All markers have effects | Limited number of markers have effects |

| Marker Effect Distribution | Normal distribution | Various prior distributions depending on method |

| Variance Treatment | Common variance for all marker effects | Marker-specific variances (except BayesC and BRR) |

| Estimation Method | Linear mixed model with spectral factorization | Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) with Gibbs sampling |

| Computational Efficiency | High | Variable, generally lower than BLUP |

G-BLUP (Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Prediction)

Theoretical Basis and Methodology

G-BLUP is a linear parametric method that has gained widespread adoption due to its computational efficiency and similarity to traditional BLUP methods [29]. In G-BLUP, the genomic relationship matrix (G-matrix) derived from markers replaces the pedigree-based relationship matrix (A-matrix) used in traditional BLUP [29]. The model can be represented as:

y = 1μ + Zu + e

Where y is the vector of phenotypes, μ is the overall mean, Z is an incidence matrix relating observations to individuals, u is the vector of genomic breeding values with variance-covariance matrix Gσ²_u, and e is the vector of residual errors [28]. The G matrix, or realized relationship matrix, is constructed using genotypes of all markers according to the method described by VanRaden (2008) [28].

The primary advantage of G-BLUP lies in its computational efficiency, as it avoids the need to estimate individual marker effects directly [29]. Instead, it focuses on estimating the total genomic value of each individual, making it particularly suitable for applications with large datasets. The method assumes that all markers contribute equally to the genetic variance, which works well for traits influenced by many genes with small effects [24].

Experimental Implementation

Implementing G-BLUP requires several key steps. First, quality control of genotype data is performed, including filtering based on minor allele frequency (typically <5%), call rate, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [27]. The genomic relationship matrix G is then constructed using the remaining markers. Different algorithms exist for constructing G, with VanRaden's method being among the most popular [28].

Variance components are estimated using restricted maximum likelihood (REML), which provides unbiased estimates of the genetic and residual variances [28]. These variance components are then used to solve the mixed model equations to obtain GEBVs for all genotyped individuals. The accuracy of GEBVs is typically evaluated using cross-validation approaches, where the data is partitioned into training and validation sets, and the correlation between predicted and observed values in the validation set is calculated [24] [27].

In practice, G-BLUP has been extensively applied to actual datasets to evaluate genomic prediction accuracy across various species and traits [24]. Its implementation has been facilitated by the development of specialized software packages that efficiently handle the computational demands of large-scale genomic analyses.

Bayesian Alphabet Methods

Theoretical Foundations

Bayesian methods for genomic selection represent a different philosophical approach from BLUP methods, treating all markers as random effects and offering flexibility through the use of different prior distributions [24]. The Bayesian framework allows for the incorporation of prior knowledge about the distribution of marker effects, which is particularly valuable for traits with suspected major genes [24]. The general Bayesian model for genomic selection can be represented as:

y = 1μ + Xg + e

Where the key difference lies in the specification of prior distributions for the marker effects g [28]. Unlike BLUP methods that assume a homogeneous variance structure across all markers, Bayesian methods allow for heterogeneous variances, enabling some markers to have larger effects than others [24].

The Bayesian approach employs Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, particularly Gibbs sampling, to estimate the posterior distributions of parameters [24]. This computational intensity represents both a strength and limitation of Bayesian methods - while allowing for more flexible modeling of genetic architecture, it requires substantial computational resources, especially for large datasets [24].

Key Bayesian Methods

BayesA

BayesA assumes that all markers have an effect, but each has a different variance [24]. The prior distribution for marker effects follows a scaled t-distribution, which has heavier tails than the normal distribution, allowing for larger marker effects [24]. This makes BayesA particularly suitable for traits influenced by a few genes with relatively large effects. The method requires specifying degrees of freedom and scale parameters for the prior distribution, which influence the extent of shrinkage applied to marker effects.

BayesB

BayesB extends BayesA by introducing a mixture distribution that allows some markers to have zero effects [24]. It assumes that a proportion π of markers have no effect on the trait, while the remaining markers have effects with different variances [24]. This method is particularly useful for traits with a known sparse genetic architecture, where only a small number of markers are expected to have substantial effects. The proportion π can be treated as either a fixed parameter or estimated from the data.

BayesC

BayesC modifies the BayesB approach by assuming that markers with non-zero effects share a common variance [24]. Similar to BayesB, it assumes that only a fraction of markers have effects on the trait, but unlike BayesB, these effects are drawn from a distribution with common variance [24]. This method represents a compromise between the sparse model of BayesB and the dense model of BayesA, reducing the number of parameters that need to be estimated.

Bayesian LASSO

Bayesian LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) uses a double exponential (Laplace) prior for marker effects, which induces stronger shrinkage of small effects toward zero compared to normal priors [24]. This approach is particularly effective for variable selection in high-dimensional problems, as it tends to produce sparse solutions where many marker effects are estimated as zero. The Bayesian implementation of LASSO allows for estimation of the shrinkage parameter within the model, avoiding the need for cross-validation.

Bayesian Ridge Regression

Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR) assumes that all marker effects have a common variance and follow a Gaussian distribution [24]. This results in shrinkage of estimates similar to ridge regression, with all effects shrunk toward zero to the same degree. BRR is most appropriate for traits governed by many genes with small effects, as it does not allow for potentially large effects at individual loci.

Table 2: Comparison of Bayesian Alphabet Methods

| Method | Marker Effects | Variance Structure | Prior Distribution | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BayesA | All markers have effects | Marker-specific variances | Scaled t-distribution | Traits with few genes of moderate to large effects |

| BayesB | Some markers have zero effects | Marker-specific variances for non-zero effects | Mixture distribution with point mass at zero | Traits with sparse genetic architecture |

| BayesC | Some markers have zero effects | Common variance for non-zero effects | Mixture distribution with point mass at zero | Balanced approach for various genetic architectures |

| Bayes LASSO | All markers have effects, but many shrunk to zero | Implicitly marker-specific through shrinkage | Double exponential (Laplace) | Variable selection in high-dimensional settings |

| Bayes Ridge Regression | All markers have effects | Common variance for all effects | Gaussian distribution | Highly polygenic traits |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Comparisons

Standard Evaluation Framework

To ensure fair comparison between different genomic selection methods, researchers have established standardized evaluation protocols. These typically involve fivefold cross-validation with 100 replications to measure genomic prediction accuracy using Pearson's correlation coefficient between GEBVs and observed phenotypic values [24]. The bias of GEBV estimation is measured as the regression of observed values on predicted values [24].

The general workflow for comparative studies involves several key steps. First, datasets are divided into training and validation populations, with the validation population comprising individuals with genotypes but no phenotypic records [28]. Each method is then applied to the training population to estimate marker effects or genomic values. These estimates are used to predict GEBVs for the validation population, and accuracy is assessed by comparing predictions to true breeding values when available or through cross-validation [24] [28].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comparing genomic selection methods

Performance Across Genetic Architectures

Comprehensive studies comparing three BLUP and five Bayesian methods using both actual and simulated datasets have revealed important patterns in method performance relative to trait genetic architecture [24]. Bayesian alphabets generally perform better for traits governed by a few genes/QTLs with relatively larger effects, while BLUP alphabets (GBLUP and CBLUP) exhibit higher genomic prediction accuracy for traits controlled by several small-effect QTLs [24]. Additionally, Bayesian methods perform better for highly heritable traits and perform at par with BLUP methods for other traits [24].

The performance differences between methods can be substantial. In one study comparing GBLUP and Bayesian methods, the correlations between GEBVs by different methods ranged from 0.812 (GBLUP and BayesCÏ€) to 0.997 (TABLUP and BayesB), with accuracies of GEBVs (measured as correlations between true breeding values and GEBVs) ranging from 0.774 (GBLUP) to 0.938 (BayesCÏ€) [28]. These results highlight the importance of matching method selection to the expected genetic architecture of the target trait.

Table 3: Performance Comparison Across Different Genetic Architectures

| Genetic Architecture | Heritability | Best Performing Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Few QTLs with large effects | High | BayesB, BayesA, Bayesian LASSO | Bayesian methods significantly outperform GBLUP by capturing major effect QTLs |

| Many QTLs with small effects | Moderate to High | GBLUP, Bayes Ridge Regression | BLUP methods perform similarly or better than Bayesian approaches |

| Mixed architecture | Variable | BayesC, Bayesian LASSO | Flexible methods that balance sparse and dense models perform best |

| Low heritability traits | Low | Compressed BLUP (cBLUP) | Specialized BLUP variants outperform standard methods for low heritability |

Bias and Reliability Assessment

Beyond prediction accuracy, the bias of GEBV estimation is an important consideration in method selection. Studies have identified GBLUP as the least biased method for GEBV estimation [24]. Among Bayesian methods, Bayesian Ridge Regression and Bayesian LASSO were found to be less biased than other Bayesian alphabets [24]. Bias is typically measured as the regression of true breeding values on GEBVs, with values closer to 1.0 indicating less bias [28].

The reliability of predictions, particularly in the context of breeding applications, is another critical metric. Not separating dominance effects from additive effects has been shown to decrease accuracy and reliability while increasing bias of predicted genomic breeding values [30]. Including dominance genetic effects in models generally increases the efficiency of genomic selection, regardless of the statistical method used [30].

Advanced Extensions and Methodological Innovations

Expanding the BLUP Alphabet

Recent research has focused on expanding the BLUP alphabet to maintain computational efficiency while improving prediction accuracy across diverse genetic architectures. Two notable innovations include SUPER BLUP (sBLUP) and compressed BLUP (cBLUP) [29]. sBLUP substitutes all available markers with estimated quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs) to derive kinship, while cBLUP compresses individuals into groups based on kinship and uses groups as random effects instead of individuals [29].

These expanded BLUP methods offer flexibility for evaluating a variety of traits covering a broadened realm of genetic architectures. For traits controlled by small numbers of genes, sBLUP can outperform Bayesian LASSO, while for traits with low heritability, cBLUP outperforms both GBLUP and Bayesian LASSO methods [29]. This development represents an important advancement in making BLUP approaches more adaptable to different genetic architectures while maintaining computational advantages.

Integration of Dominance and Epistatic Effects

Traditional GS models have primarily focused on additive genetic effects, but non-additive effects can contribute significantly to trait variation. Recent methodological advances have incorporated dominance and epistatic effects into genomic prediction models [30]. Studies have shown that not separating dominance effects from additive effects leads to decreased accuracy and reliability and increased bias of predicted genomic breeding values [30].

Bayesian methods generally show better performance than GBLUP for traits with non-additive genetic architecture, exhibiting higher prediction accuracy and reliability with less bias [30]. The inclusion of dominance effects is particularly important for traits where heterosis or inbreeding depression are significant factors, such as in crossbreeding systems or for fitness-related traits.

Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic Selection Studies

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | Illumina SNP arrays, Affymetrix Axiom arrays, Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) | Generate dense genetic marker data for training and validation populations |

| Reference Genomes | Species-specific reference assemblies (e.g., ARS-UCD1.2 for cattle, GRCm39 for mice) | Provide framework for aligning sequences and assigning marker positions |

| Biological Samples | DNA from blood, tissue, or semen samples (animals), leaf tissue (plants) | Source material for genotyping and establishing training populations |

| Phenotypic Databases | Historical breeding records, field trial data, clinical measurements | Provide phenotypic measurements for model training and validation |

| Software Packages | GAPIT, BGLR, DMU, ASReml, BLUPF90 | Implement various GS methods and statistical analyses |

Computational Implementation

The implementation of genomic selection methods requires specialized software tools. The R package BGLR (Bayesian Generalized Linear Regression) provides comprehensive implementations of Bayesian methods, allowing users to specify different prior distributions for marker effects [30]. For BLUP-based approaches, the Genome Association and Prediction Integrated Tool (GAPIT) implements various BLUP alphabet methods including the newly developed sBLUP and cBLUP [29].

Computational requirements vary significantly between methods. GBLUP and related BLUP methods are generally the fastest, while Bayesian methods requiring MCMC sampling are computationally intensive [24] [30]. Boosting algorithms have been identified as among the slowest methods for genomic breeding value prediction [30]. This computational efficiency differential is an important practical consideration when selecting methods for large-scale applications.

The comparison between G-BLUP and Bayesian alphabet methods reveals a complex landscape where no single method universally outperforms others across all scenarios. The optimal choice depends critically on the genetic architecture of the target trait, with Bayesian methods generally superior for traits governed by few genes of large effect, and G-BLUP performing well for highly polygenic traits [24]. Recent expansions to the BLUP alphabet, such as sBLUP and cBLUP, show promise in bridging this performance gap while maintaining computational efficiency [29].

Future developments in genomic selection will likely focus on integrating multi-omics data, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics, to improve prediction accuracy [31]. The incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches represents another frontier, with tools like Google's DeepVariant already showing improved variant calling accuracy [31]. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and costs decrease, the application of whole-genome sequence data in genomic selection promises to further enhance prediction accuracy by potentially capturing causal variants directly.

The ongoing challenge for researchers and breeders remains the appropriate matching of methods to specific applications, considering both statistical performance and practical constraints. As genomic selection continues to evolve, the development of adaptable, computationally efficient methods that perform well across diverse genetic architectures will be crucial for maximizing genetic gain in breeding programs and advancing our understanding of complex trait genetics.

Identity-by-Descent (IBD) Detection in High-Recombining Genomes

Identity-by-Descent (IBD) refers to genomic segments inherited by two or more individuals from a common ancestor without recombination [13]. These segments are "maximal," meaning they are bounded by recombination events on both ends [13]. In theoretical population genomics, IBD analysis is a cornerstone for inferring demographic history, detecting natural selection, estimating effective population size (Ne), and understanding fine-scale population structure [32] [33].

The reliability of these inferences is highly dependent on the accurate detection of IBD segments. This presents a significant challenge when studying organisms with high recombination rates, such as the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum). In these genomes, high recombination relative to mutation leads to low marker density per genetic unit, which can severely compromise IBD detection accuracy [32] [34] [33]. This technical guide explores the specific challenges of IBD detection in high-recombining genomes, provides benchmarking data for contemporary tools, outlines optimized experimental protocols, and discusses implications for genomic surveillance and drug development.

The Challenge of High-Recombining Genomes

High-recombining genomes like P. falciparum exhibit evolutionary parameters that diverge significantly from the human genome, for which many IBD detection tools were originally designed. The core of the challenge lies in the balance between recombination and mutation rates.

P. falciparum recombines approximately 70 times more frequently per unit of physical distance than humans [32] [33]. However, it shares a similar mutation rate with humans, on the order of 10â»â¸ per base pair per generation [32] [33]. This high recombination-to-mutation rate ratio results in a drastically reduced number of common variants, such as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), per centimorgan (cM). While large human whole-genome sequencing datasets typically provide millions of common biallelic SNPs, P. falciparum datasets only contain tens of thousands [32] [33]. Consequently, the per-cM SNP density in P. falciparum can be two orders of magnitude lower than in humans (approximately 25 SNPs/cM vs. 1,660 SNPs/cM) [33], often providing insufficient information for accurate IBD segment detection.

This low marker density per genetic unit disproportionately affects the detection of shorter IBD segments, which are critical for analyzing older relatedness and complex demographic histories. Performance degradation manifests as elevated false negative rates (failure to detect true IBD segments) and/or false positive rates (erroneous inference of non-existent segments) [32] [33].

Benchmarking IBD Detection Tools

A unified benchmarking framework for high-recombining genomes has revealed that the performance of IBD callers varies significantly under low SNP density conditions. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and performance of several commonly used and recently developed tools.

Table 1: Benchmarking of IBD Detection Tools for High-Recombining Genomes

| Tool | Underlying Method | Key Features | Performance in High Recombination |

|---|---|---|---|

| hmmIBD / hmmibd-rs [32] [35] | Probabilistic (Hidden Markov Model) | Designed for haploid genomes; robust to low SNP density. | Superior accuracy for shorter segments; provides less biased Ne estimates; low false positive rate [32] [34]. |

| isoRelate [33] | Probabilistic (Hidden Markov Model) | Designed for Plasmodium species. | Better IBD quality with lower marker densities; suffers from high false negative rates for shorter segments [33]. |

| Refined IBD [33] | Identity-by-State-based | Originally designed for human genomes. | High false negative rates for shorter segments in P. falciparum-like genomes [33]. |

| hap-IBD [33] | Identity-by-State-based | Scales well to large sample sizes and genomes. | High false negative rates for shorter segments in P. falciparum-like genomes [33]. |

| phased IBD [33] | Identity-by-State-based | Recent advancement in IBD detection. | High false negative rates for shorter segments in P. falciparum-like genomes [33]. |

| KinSNP [36] | IBD segment-based | Used for human identification in forensic contexts. | Validated for human data; accuracy maintained with up to 75% simulated missing data, but sensitive to sequence errors [36]. |

The benchmarking results indicate that hmmIBD consistently outperforms other methods in the context of high-recombining genomes, particularly for quality-sensitive downstream analyses like effective population size estimation [32] [34]. Its probabilistic framework, specifically tailored for haploid genomes, makes it more robust to the challenges of low SNP density.

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking Results from Simulated P. falciparum-like Genomes

| Performance Metric | hmmIBD | isoRelate | Refined IBD | hap-IBD | phased IBD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| False Negative Rate (Shorter segments) | Lower | High | High | High | High |

| False Positive Rate | Low | Lower | Higher | Varies | Varies |

| Bias in Ne Estimation | Less Biased | N/A | Biased | N/A | N/A |

| Sensitivity to Parameter Optimization | Beneficial | Beneficial | Critical | Critical | Critical |

Optimized Workflows and Protocols

Core IBD Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for accurate IBD detection in high-recombining genomes, from data preparation to downstream analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for IBD Detection

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Input Data: Begin with genotype data in Binary VCF (BCF) or VCF format.

- Quality Filtering: Use tools like

hmmibd-rsorbcftoolsto filter samples and sites based on genotype missingness. This ensures a balance between retaining a sufficient number of markers and samples while maintaining data quality [35]. - Haploid Genome Construction: For haploid organisms like P. falciparum from monoclonal samples, construct haploid genomes by replacing heterozygous calls. A common heuristic is to use the dominant allele if supported by a high fraction of reads (e.g., >90% read support) and a minimum total depth; otherwise, set the genotype to missing [35].

Step 2: Incorporating a Recombination Rate Map

- Using a non-uniform recombination rate map significantly enhances accuracy. Tools like

hmmibd-rsallow the use of a user-provided genetic map to calculate genetic distances between markers for the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) inference and subsequent IBD segment length filtration [35]. - Benefit: This mitigates the overestimation of IBD breakpoints in recombination "cold spots" and their underestimation in "hot spots," leading to more precise IBD segment boundaries and better length-based filtering [35].

Step 3: Running IBD Detection with Optimized Parameters

- Tool Selection: Based on benchmarking,

hmmIBDor its enhanced versionhmmibd-rsis recommended for high-recombining genomes [32] [34] [35]. - Parameter Optimization: Key parameters related to marker density and HMM transitions must be optimized. This often involves adjusting the minimum SNP density and HMM transition probabilities to account for the high recombination rate [32] [33]. For

hmmibd-rs, leverage its parallel processing capability to handle large datasets efficiently. - Execution: The following diagram details the core computational process of an HMM-based IBD caller.

Step 4: Post-processing and Downstream Analysis

- Segmentation Filtering: Filter detected IBD segments by length (in centimorgans) to remove likely false positives. The high variance in segment length estimates means short segments are more error-prone [35]. A common threshold is retaining segments ≥ 2 cM [35].

- Downstream Applications: Use the high-confidence IBD segments to infer:

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

A successful IBD analysis pipeline relies on a suite of specialized software tools and curated datasets.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for IBD Analysis

| Category | Item / Software | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Primary IBD Callers | hmmibd-rs [35] | Enhanced, parallelized implementation of hmmIBD; supports genetic maps for accurate IBD detection in high-recombining genomes. |

| isoRelate [33] | HMM-based IBD detection tool designed specifically for Plasmodium species. | |

| Benchmarking & Simulation | Population Genetic Simulators (e.g., msprime, SLiM) |

Generate simulated genomes with known ground-truth IBD segments under realistic demographic models for tool benchmarking [32] [33]. |

| tskibd [33] | Used in benchmarking studies to establish the "true" IBD segments from simulated data. | |

| Data & Validation | MalariaGEN Pf7 Database [32] [34] [33] | A public repository of over 20,000 P. falciparum genome sequences, essential for empirical validation of IBD findings. |

| Data Preprocessing | BCF Tools / bcf_reader (in hmmibd-rs) [35] |

Utilities for processing, filtering, and manipulating genotype files in VCF/BCF format. |

| Ancillary Analysis | DEPloid / DEPloidIBD [35] | Tools for deconvoluting haplotypes from polyclonal infections, a critical preprocessing step for complex samples. |

Implications for Genomic Surveillance and Drug Development

Accurate IBD detection in high-recombining pathogens like P. falciparum directly enhances genomic surveillance, which is crucial for public health interventions and drug development.

- Tracking Transmission and Resistance: In low transmission settings, IBD can differentiate local transmission from imported cases [32] [33]. It also helps identify and monitor the emergence and spread of haplotypes under positive selection, such as those conferring antimalarial drug resistance [32] [33]. This is vital for monitoring the efficacy of existing drugs and guiding the development of new ones.

- Evaluating Interventions: A rapid decrease in genetic diversity and effective population size, inferred from IBD patterns, can indicate successful malaria intervention programs [32] [33]. This provides a molecular metric for assessing the impact of public health campaigns.

- Informing Vaccine Development: Understanding fine-scale population structure and relatedness through IBD can reveal conserved genomic regions that may serve as potential targets for vaccine development.

The continuous improvement of computational methods, such as the development of hmmibd-rs which reduces computation time from days to hours for large datasets, makes large-scale genomic surveillance increasingly feasible and timely [35].

Identity-by-descent analysis remains a powerful approach in theoretical population genomics. For high-recombining genomes, the challenge of low marker density per genetic unit necessitates context-specific evaluation and optimization of IBD detection methods. Benchmarking studies consistently show that probabilistic methods like hmmIBD and its successor hmmibd-rs are superior in this context, especially when parameters are optimized and non-uniform recombination maps are incorporated. Adopting the rigorous workflows and tools outlined in this guide enables researchers to generate more reliable IBD data, thereby paving the way for more accurate genomic surveillance, a deeper understanding of pathogen evolution, and informed strategies for disease control and drug development.

Correcting for Sequencing Error in Parameter Estimation (MCLE Methods)