Validating Protein-Ligand Binding with Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Practice

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate protein-ligand binding using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Validating Protein-Ligand Binding with Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Practice

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate protein-ligand binding using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. It covers foundational principles, from understanding force fields and sampling limitations to advanced methodological applications like absolute binding free energy calculations and enhanced sampling. The guide details practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for simulation stability and performance and establishes rigorous protocols for validating results against experimental data and benchmarking across methods. By integrating these four core intents, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of MD simulations in drug discovery pipelines.

Understanding the Foundations: Why MD is a Powerful Tool for Binding Validation

The Critical Role of Binding Free Energy in Drug Discovery

In rational drug design, the binding free energy (ΔG) quantifies the strength of the interaction between a potential drug molecule (ligand) and its biological target (receptor) [1]. Accurate prediction of ΔG is paramount as it directly influences a drug's potency and efficacy, guiding researchers toward promising compounds and away from likely failures [2] [3]. Computational methods for predicting binding free energy have thus become indispensable tools, capable of significantly compressing the traditional 10-12 year drug discovery timeline and reducing the immense costs, which can exceed $2.6 billion per new drug [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the primary computational methods used to predict binding free energy, detailing their protocols, accuracy, and application within the broader context of validating protein-ligand interactions through molecular dynamics research.

Comparative Analysis of Binding Free Energy Methods

The following table summarizes the key computational techniques used for binding free energy prediction, comparing their theoretical basis, applications, and performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Computational Methods for Binding Free Energy Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Primary Application | Reported Accuracy | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | End-state analysis using molecular mechanics and implicit solvation [1] | Virtual screening, binding affinity ranking [1] | Lower accuracy; improves docking results but limited precision [1] | Moderate |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Alchemical transformation through intermediate λ states [4] [5] [6] | Relative binding affinity for congeneric series [3] [6] | ~1-2 kcal/mol RMSE; approaching experimental reproducibility [3] [6] | High |

| Thermodynamic Integration (TI) | Alchemical transformation using ∂U/∂λ [1] [4] | Relative binding affinity calculations [1] | Comparable to FEP [1] [4] | High |

| Nonequilibrium Switching (NES) | Short, bidirectional out-of-equilibrium transformations [2] | High-throughput relative binding free energy [2] | Comparable to FEP/TI with 5-10X higher throughput [2] | Moderate-High |

| Potential of Mean Force (PMF) | Reversible work along a physical reaction coordinate [5] [3] | Absolute binding free energy, ligand pathways [5] | Computationally expensive; convergence challenges [5] | Very High |

| Accelerated MD (aMD) | Enhanced sampling with boost potential [7] | Ligand binding pathways and kinetics [7] | Captures binding events faster than conventional MD [7] | High |

The selection of an appropriate method depends on the specific drug discovery context. Relative binding free energy methods like FEP and TI are particularly valuable for lead optimization, where small, systematic modifications are made to a lead compound [3]. These alchemical methods calculate the free energy difference between two similar ligands by transforming one into another in both the bound and unbound states [3]. For projects requiring high throughput, NES offers a distinct advantage by replacing slow equilibrium simulations with many rapid, independent transitions that can be run concurrently, achieving 5-10 times higher throughput than traditional methods [2].

Table 2: Analysis of Method Capabilities and Limitations

| Method | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM/PBSA/GBSA | Fast; good for post-docking refinement; less demanding than FEP [1] | Limited precision; accuracy depends on parameter tuning [1] | Initial screening and ranking of large compound libraries |

| FEP/TI | High accuracy for small modifications; widely validated [3] [6] | Challenging for large conformational changes or dissimilar ligands [3] | Lead optimization of congeneric series |

| NES | High throughput; highly parallelizable; fault-tolerant [2] | Relatively newer method with less established track record [2] | Large-scale compound evaluation in cloud environments |

| Enhanced Sampling (aMD) | Captures binding kinetics and pathways [7] | Specialized analysis required; not purely for affinity prediction [7] | Understanding binding mechanisms and metastable states |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Alchemical Free Energy Calculation Protocol

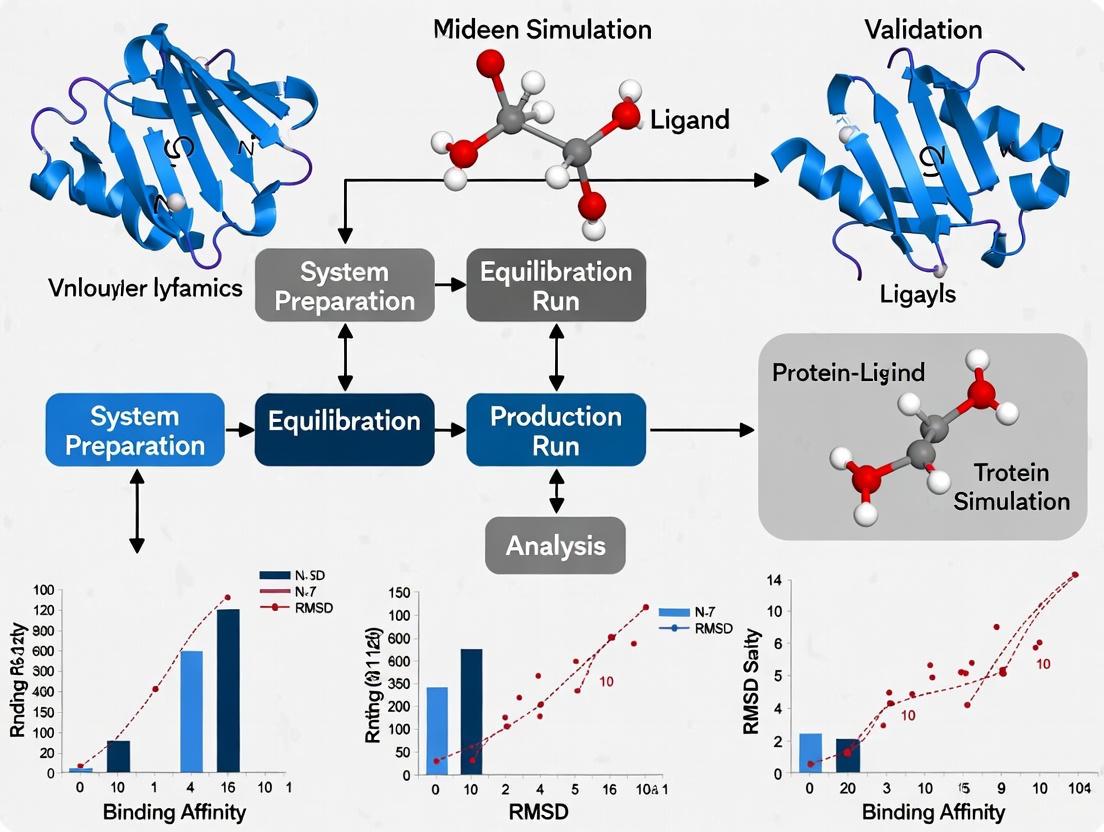

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for alchemical free energy calculations, common to FEP and TI approaches:

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for alchemical binding free energy calculations.

The standard protocol involves several key stages [4]:

System Preparation: The process begins with a high-quality receptor structure, often from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM. Critical preparatory steps include:

- Adding missing loops or flexible regions

- Assigning correct protonation states of binding site residues at physiological pH

- Determining ligand tautomeric states

- Adding hydrogens, solvation, and counterions to neutralize the system

Thermodynamic Cycle Definition: Alchemical methods employ a non-physical pathway that connects the two end states of interest through a series of intermediate states characterized by a coupling parameter λ [4]. This parameter progressively transforms the Hamiltonian of the system from describing one ligand to describing the other.

Intermediate λ State Selection: The transformation is divided into discrete windows (typically 10-20), with careful attention to ensuring sufficient phase space overlap between adjacent windows for convergence [4] [5]. For example, a transformation might use λ values of 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 0.9, and 1.0 [5]. Electrostatic and van der Waals transformations are often separated or use soft-core potentials to avoid singularities [4].

Equilibration and Production Sampling: Each λ window undergoes energy minimization, equilibration, and finally production molecular dynamics simulation. The conformational sampling must be adequate to represent the Boltzmann distribution for each state.

Free Energy Analysis: Using methods such as the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) [5] or Multistate BAR (MBAR) [4], the free energy differences between adjacent states are calculated and summed to give the total free energy difference.

Enhanced Sampling for Binding Pathways

While alchemical methods predict affinity, enhanced sampling techniques like accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) provide insights into binding kinetics and pathways [7]. In aMD, a non-negative boost potential is added to the system's potential energy when it drops below a predefined threshold, effectively reducing energy barriers and accelerating transitions between low-energy states [7]. This approach has successfully captured millisecond-timescale events, such as the binding of agonists and antagonists to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), in significantly shorter simulation times [7].

Validation Against Experimental Data

The gold standard for validating computational predictions is comparison with experimentally measured binding affinities, typically reported as dissociation constants (Kd), inhibition constants (Ki), or half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) [6]. The accuracy of experimental measurements themselves sets the upper limit for achievable predictive accuracy. Recent analyses suggest:

- The reproducibility of relative binding affinity measurements between different experimental assays has a root-mean-square difference of approximately 0.56-0.69 pKi units (0.77-0.95 kcal/mol) [6].

- Well-executed FEP calculations can achieve accuracy comparable to this experimental reproducibility, with errors in the range of 1-2 kcal/mol for many systems [3] [6].

- For congeneric series with careful system preparation, FEP has demonstrated the ability to achieve errors approaching 1 kcal/mol [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Provide parameters for potential energy calculations; critical accuracy determinant [7] [6] |

| Solvation Models | TIP3P, GBSA, PBSA | Represent solvent effects; implicit vs. explicit trade-offs [1] [5] |

| Software Platforms | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, DESMOND, FEP+ | MD simulation engines with free energy capabilities [4] [5] |

| Enhanced Sampling | GaMD, MetaD, aMD | Accelerate rare events sampling; study binding pathways [7] [1] |

| System Preparation | GAAMP, CGenFF, tleap | Generate ligand parameters; prepare simulation systems [7] |

| Analysis Tools | alchemical-analysis.py, fastDRH | Analyze free energy calculations; automate workflows [1] [4] |

The following diagram illustrates how these tools integrate within a typical research workflow for binding free energy validation:

Figure 2: Tool integration in a binding free energy research workflow.

Binding free energy calculations have matured into powerful tools that provide critical insights for drug discovery. The current state of the art enables researchers to predict relative binding affinities with accuracy approaching experimental reproducibility for many systems. Method selection involves important trade-offs: MM/PB(GB)SA offers speed for initial screening, while FEP/TI provides higher accuracy for lead optimization at greater computational cost. Emerging methods like NES promise enhanced throughput through massive parallelism.

Future advancements will likely focus on improving force field accuracy, expanding the domain of applicability to more challenging targets like membrane proteins, and integrating machine learning approaches to accelerate sampling. As these methods continue to evolve, their role in rational drug design will expand, potentially transforming the efficiency and success rate of pharmaceutical development. For now, rigorous validation against experimental data and careful system preparation remain essential for obtaining reliable predictions that can genuinely guide drug discovery efforts.

The fundamental challenge in simulating protein-ligand binding with molecular dynamics (MD) is the vast disparity between computational and biological timescales. While functional conformational changes and binding events occur from microseconds to seconds in nature, all-atom MD simulations are typically limited to microsecond scales, creating a critical sampling bottleneck [8] [9]. This "sampling problem" arises because biomolecules navigate rough energy landscapes with multiple local minima separated by high energy barriers, causing simulations to become trapped in non-functional states [10]. For drug discovery professionals, this limitation is particularly acute as accurate binding affinity prediction requires sufficient sampling of all relevant conformational substates [10] [11].

In the post-AlphaFold era, where static protein structures have become readily available, the major frontier has shifted to understanding dynamic conformational transitions between functionally important states [12] [8]. This review comprehensively compares current enhanced sampling methodologies, evaluating their performance in overcoming temporal barriers for protein-ligand binding validation, with specific emphasis on computational efficiency, predictive accuracy, and practical implementation requirements.

Enhanced Sampling Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Collective Variable-Based Enhanced Sampling

Collective variable (CV)-based methods enhance sampling by applying bias potentials along carefully selected reaction coordinates that describe the slowest degrees of freedom during conformational transitions [13].

- Metadynamics discourages revisiting previously sampled states by "filling free energy wells with computational sand" through the addition of repulsive Gaussian potentials, enabling exploration of the entire free energy landscape for applications including protein folding and conformational changes [10].

- Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) employs parallel simulations at different temperatures, with periodic exchange of configurations between replicas based on Metropolis criteria, allowing efficient barrier crossing in higher-temperature replicas while maintaining proper Boltzmann sampling at the target temperature [10].

- True Reaction Coordinate (tRC) Methods represent a recent breakthrough where bias is applied specifically along the few essential coordinates that determine the committor probability. These tRCs control both conformational changes and energy relaxation, enabling dramatic acceleration of processes like HIV-1 protease flap opening and ligand unbinding by 10⁵ to 10¹⁵-fold compared to standard MD [8].

Advanced Sampling Without Predefined Coordinates

For systems where suitable CVs are unknown a priori, several methods enable enhanced sampling without requiring predefined reaction coordinates.

- FRESEAN Mode Analysis identifies anharmonic low-frequency vibrations from short equilibrium trajectories, providing highly reproducible collective variables that naturally drive conformational transitions. This approach has successfully sampled conformational changes in proteins including lysozyme, HIV-1 protease, and KRAS within a single day on standard HPC hardware [9].

- Generalized Simulated Annealing (GSA) employs an artificial temperature that decreases during simulation, making it particularly suitable for characterizing very flexible systems and large macromolecular complexes at relatively low computational cost [10].

Free Energy Calculation Methods

Accurate binding affinity prediction requires calculating free energy differences between bound and unbound states.

- MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods compute binding free energies by combining molecular mechanics energy with Poisson-Boltzmann or Generalized Born solvation terms, and surface area-based nonpolar contributions. Recent advancements enable application to membrane protein-ligand systems through multitrajectory approaches and automated membrane parameter calculation [14].

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI) provide high accuracy but require extensive sampling of intermediate states, making them computationally prohibitive for large-scale screening [15] [11].

- Fragmentation Approaches like the Generalized Many-Body Expansion for Density Matrices (GMBE-DM) partition large biomolecules into smaller fragments for quantum mechanical calculations, achieving strong correlation with experimental binding free energies (R² = 0.84) in under 5 minutes per complex [11].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Enhanced Sampling and Binding Affinity Methods

| Method | Acceleration/Speed | Accuracy (Correlation/Success) | System Size Limitations | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Reaction Coordinates [8] | 10⁵ to 10¹⁵-fold acceleration | Follows natural transition pathways; enables NRT generation | Requires energy relaxation simulations | HIV-1 protease flap opening, PDZ allostery |

| FRESEAN Mode Analysis [9] | ~1 day computation time | Reproducible low-frequency modes (correlation >0.9) | Tested on proteins up to multi-domain systems | Lysozyme, HIV-1 Pr, MCL-1, RBP, KRAS dynamics |

| GMBE-DM [11] | <5 minutes per complex | R² = 0.84 with experimental ΔG | 200-400 atom binding pockets | CDK2 and JAK1 ligand ranking |

| D3-ML [11] | <1 second per complex | R² = 0.87 with experimental ΔG | Scalable to large systems | High-throughput virtual screening |

| MMPBSA with Ensemble [14] | Medium throughput | Significant improvement over single-trajectory | Adapted for membrane proteins | P2Y12R conformational changes |

| Metadynamics [10] [13] | Dependent on CV quality | Accurate FES with optimal CVs | Low-dimensional CVs essential | Protein folding, molecular docking |

| REMD [10] | More efficient than MD with positive activation energy | Broad conformational sampling | Many replicas needed for large systems | Peptide and protein folding |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

True Reaction Coordinate Identification Protocol

The identification and application of true reaction coordinates involves a rigorous multi-step process [8]:

- Potential Energy Flow Calculation: Compute energy flows through individual coordinates using the equation (d{W}{i}=-\frac{\partial U\left({{\bf{q}}}\right)}{\partial {q}{i}}d{q}_{i}), which represents the energy cost of motion for each coordinate.

- Generalized Work Functional Analysis: Generate an orthonormal coordinate system (singular coordinates) that disentangles true reaction coordinates from non-essential coordinates by maximizing potential energy flows.

- tRC Validation: Verify that identified coordinates control both conformational changes and energy relaxation processes.

- Enhanced Sampling: Apply bias potentials directly to the identified tRCs to achieve dramatic acceleration of conformational transitions while maintaining physical pathways.

This protocol successfully accelerated the ligand dissociation process in HIV-1 protease, which has an experimental lifetime of 8.9×10⁵ seconds, to just 200 picoseconds in simulation [8].

FRESEAN Mode Analysis Workflow

The FRESEAN (Frequency-Selective Anharmonic) mode analysis protocol enables rapid identification of collective variables without prior knowledge of conformational changes [9]:

- Equilibrium Simulation: Run five independent 20-ns all-atom MD trajectories with randomized initial velocities.

- Coarse-Graining: Convert all-atom trajectories to a simplified representation (two beads per residue) preserving collective low-frequency vibrations.

- Mode Calculation: Apply FRESEAN analysis to isolate anharmonic low-frequency vibrations contributing most to the zero-frequency vibrational density of states.

- CV Selection: Select modes 7-9 (excluding translational and rotational modes 1-6) as collective variables for enhanced sampling.

- Biased Sampling: Perform enhanced sampling simulations using the identified low-frequency modes as CVs to explore conformational transitions.

This workflow consistently reproduces low-frequency vibrational modes across independent replicas (with 2D subspace correlations >0.9) and has successfully captured known conformational transitions in test proteins including lysozyme, HIV-1 protease, and KRAS [9].

MMPBSA for Membrane Proteins Protocol

Advanced MMPBSA calculations for membrane protein-ligand systems require specific modifications to address the membrane environment [14]:

- System Preparation: Model missing loops using tools like Modeller, select appropriate membrane lipid composition, and embed the protein in a lipid bilayer using CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder.

- Multi-Trajectory Approach: Assign distinct protein conformations (pre- and post-ligand binding) as receptors and complexes instead of using a single trajectory.

- Ensemble Simulations: Run multiple replicas to improve conformational sampling depth.

- Membrane Parameter Automation: Use enhanced tools in Amber to automatically determine membrane thickness and location rather than relying on default values.

- Entropy Corrections: Apply truncated normal mode analysis for more efficient entropy calculations.

- Continuum Dielectric Treatment: Ensure consistent dielectric treatment in electrostatic energy calculations between GB and PB calculations.

This protocol demonstrated significant improvement in accuracy for simulating P2Y12R conformational changes upon ligand binding [14].

Diagram 1: Method Selection Framework for Enhanced Sampling. This roadmap guides researchers in selecting appropriate sampling strategies based on their system characteristics and available prior knowledge.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Enhanced Sampling Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Key Features | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| PySAGES [13] | Advanced sampling library | GPU acceleration, multiple backend support, ML framework integration | Open-source, Python-based |

| AMBER [14] | MD simulation package | Enhanced MMPBSA for membrane proteins, automated membrane parameters | Commercial with academic licensing |

| FRESEAN Analysis [9] | Low-frequency mode identification | Anharmonic vibrations, coarse-grained representation, high reproducibility | Custom implementation |

| LABind [16] | Binding site prediction | Graph transformer, cross-attention mechanism, unseen ligand capability | Open-source |

| GMBE-DM [11] | Quantum fragmentation | Density matrix reconstruction, linear-scaling, high accuracy | Research implementation |

| True RC Method [8] | Reaction coordinate identification | Energy relaxation analysis, natural pathway preservation | Research implementation |

| GPCRmd [12] | Specialized database | MD trajectories for GPCR proteins, standardized analysis | Public database |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Acceleration Efficiency and Binding Affinity Accuracy

Recent methodological advances demonstrate dramatic improvements in both sampling efficiency and binding affinity prediction accuracy.

Sampling Acceleration: True reaction coordinate methods have achieved unprecedented acceleration factors of 10⁵ to 10¹⁵ for protein conformational changes, reducing processes that would require years of standard MD simulation to tractable timescales [8]. FRESEAN mode analysis enables complete characterization of protein conformational ensembles within approximately one day on standard HPC hardware [9].

Binding Affinity Prediction: Quantum fragmentation methods like GMBE-DM achieve strong correlation with experimental binding free energies (R² = 0.84) while requiring less than 5 minutes per complex without extensive parallelization [11]. The machine learning-corrected dispersion potential D3-ML demonstrates even stronger ranking performance (R² = 0.87) with sub-second runtime per complex, making it ideal for high-throughput virtual screening [11].

Membrane Protein Advancements: Enhanced MMPBSA protocols for membrane proteins significantly improve accuracy for systems like P2Y12R, addressing critical challenges in simulating membrane protein-ligand interactions [14].

Table 3: Acceleration Factors and Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

| Method | Time Scale/Throughput | Acceleration Factor | Binding Affinity Correlation | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard MD [8] | Microseconds to milliseconds | 1x (reference) | Not applicable for slow processes | Physical accuracy without bias |

| True RC Method [8] | 200 ps for 8.9×10⁵ s process | 10⁵ to 10¹⁵-fold | Natural reactive trajectories | Follows physical pathways |

| FRESEAN Sampling [9] | ~1 day per protein | Enables previously inaccessible transitions | Captures conformational ensembles | No prior knowledge required |

| GMBE-DM [11] | <5 min per complex | N/A | R² = 0.84 | Quantum accuracy with high throughput |

| D3-ML [11] | <1 second per complex | N/A | R² = 0.87 | Extreme speed with high accuracy |

| MMPBSA Ensemble [14] | Medium throughput | N/A | Significant improvement over standard | Membrane protein capability |

Diagram 2: Workflow Comparison of Three Enhanced Sampling Protocols. Each pathway represents a distinct strategic approach to overcoming the sampling problem, from physics-based tRC identification to automated CV discovery and specialized membrane protein methods.

The field of enhanced sampling for protein-ligand binding validation is rapidly evolving toward higher accuracy, greater computational efficiency, and broader applicability to challenging systems like membrane proteins. True reaction coordinate methods represent a paradigm shift by providing both dramatic acceleration and preservation of natural transition pathways [8]. Simultaneously, machine learning approaches are delivering exceptional speed for binding affinity ranking while maintaining quantum-level accuracy [11].

For research teams with specific protein systems and known conformational changes, true RC methods and advanced metadynamics provide the most physically accurate sampling. For high-throughput virtual screening of diverse chemical libraries, D3-ML and GMBE-DM offer unprecedented combination of speed and accuracy. When studying systems where relevant collective variables are unknown, FRESEAN mode analysis enables rapid, automatic discovery of effective coordinates for enhanced sampling [9].

Future methodological development will likely focus on integrating machine learning more deeply with physical principles, improving membrane and multi-protein complex simulations, and developing automated workflows that reduce expert intervention requirements. As these methods mature and become more accessible, comprehensive sampling of protein conformational landscapes will transition from extraordinary challenge to routine component of drug discovery pipelines.

Force fields (FFs) serve as the fundamental mathematical models that describe the potential energy and interactions between all components in a biomolecular system at the molecular mechanics level [17]. As the underlying engine of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, force fields provide the physics-based framework for understanding molecular interactions, conformational dynamics, and thermodynamic properties [17]. The accuracy of these force fields directly determines the reliability of MD simulations in probing biological processes and predicting molecular behavior.

In the context of protein-ligand binding validation—a critical application in drug discovery—force field limitations can significantly impact the predictive power of simulations [17]. The development of biomolecular force fields has evolved significantly since the first all-atom MD simulation of a protein in 1977, with continuous refinements aimed at improving their accuracy and broadening their applications in biological and therapeutic discoveries [17]. Understanding the current capabilities and limitations of different force field approaches is therefore essential for researchers relying on computational methods for drug development.

Force Field Types and Their Fundamental Differences

Additive All-Atom Force Fields

Additive all-atom force fields are the most routinely used FFs in MD simulations of biomolecules [17]. These are characterized by fixed partial charges assigned to each atom, with nonbonded electrostatic interactions calculated using a pairwise additive approximation [17]. The potential energy for a given configuration is calculated as the sum of bonded and nonbonded interactions. Popular additive force families include:

- AMBER: Frequently used for nucleic acids and proteins [18]

- CHARMM: Popular for membrane-bound proteins and increasingly used for nucleic acids, especially since the CHARMM36 update [18]

- OPLS: Commonly employed in drug discovery applications [19]

- GROMOS: Applied for various biomolecular systems [18]

Polarizable Force Fields

Unlike additive force fields with fixed partial charges, polarizable force fields incorporate electronic response to the environment by allowing charges or dipoles to fluctuate during simulations [17]. This more physically realistic representation comes at significantly increased computational cost but can provide more accurate modeling of electrostatic interactions in heterogeneous environments.

Coarse-Grained Models

Coarse-grained (CG) models reduce computational cost by representing multiple atoms with single interaction sites [18]. For example, a single particle may substitute for atoms in an amino acid residue within a protein [18]. This simplification decreases the number of interaction calculations and allows larger time steps, drastically saving computation time and costs [18]. The trade-off is loss of atomic-level detail, making CG models problem-dependent [18].

Machine Learning Potentials

The recent deep learning revolution has led to new opportunities in force field parametrization [17]. Machine learning potentials replace traditional energy function forms with neural networks trained on quantum mechanical data, potentially offering both accuracy and computational efficiency [17].

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment: Performance Comparison

Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction

Free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations directly probe force field accuracy for protein-ligand binding, a critical application in drug discovery. The table below summarizes performance data across different force field combinations:

Table 1: Force Field Performance in Binding Free Energy Prediction

| Force Field Combination | Water Model | Charge Model | MUE (kcal/mol) | RMSE (kcal/mol) | Correlation (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS2.1 [19] | SPC/E [19] | CM1A-BCC [19] | 0.77 [19] | 0.93 [19] | 0.66 [19] |

| AMBER ff14SB [19] | SPC/E [19] | AM1-BCC [19] | 0.89 [19] | 1.15 [19] | 0.53 [19] |

| AMBER ff14SB [19] | TIP3P [19] | AM1-BCC [19] | 0.82 [19] | 1.06 [19] | 0.57 [19] |

| AMBER ff14SB [19] | TIP4P-EW [19] | AM1-BCC [19] | 0.85 [19] | 1.11 [19] | 0.56 [19] |

| AMBER ff15ipq [19] | SPC/E [19] | AM1-BCC [19] | 0.85 [19] | 1.07 [19] | 0.58 [19] |

| AMBER ff14SB [19] | TIP3P [19] | RESP [19] | 1.03 [19] | 1.32 [19] | 0.45 [19] |

| AMBER ff15ipq [19] | TIP4P-EW [19] | AM1-BCC [19] | 0.95 [19] | 1.23 [19] | 0.49 [19] |

The mean unsigned error (MUE) values around 0.8-1.0 kcal/mol demonstrate that current force fields can achieve accuracy comparable to experimental reproducibility when careful preparation of protein and ligand structures is undertaken [6].

pKa Prediction and Electrostatic Properties

Force field performance in predicting pKa values reveals limitations in modeling electrostatic interactions and solvation:

Table 2: Force Field Limitations in pKa Prediction

| Force Field | Water Model | Key Limitation | Affected Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amber ff19SB [20] | OPC [20] | Significantly overestimated pKa downshifts [20] | Buried His, salt-bridge Glu/Asp [20] |

| Amber ff14SB [20] | TIP3P [20] | Larger pKa errors than ff19SB/OPC [20] | Buried His, salt-bridge Glu/Asp [20] |

| CHARMM c22/CMAP [20] | CHARMM TIP3P [20] | Similar error patterns but smaller magnitude [20] | Buried His, salt-bridge Glu/Asp [20] |

These errors primarily stem from undersolvation of neutral histidines and overstabilization of salt bridges, highlighting specific limitations in electrostatic modeling [20].

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Validation

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol

The assessment of force field accuracy for protein-ligand binding typically follows rigorous FEP protocols:

System Preparation:

- Protein structures are obtained from PDB with termini properly treated (N-termini as protonated amine, C-termini as charged carboxylate) [19]

- Protonation states of binding residues are carefully assigned [6]

- Ligand parameters are generated using charge models (AM1-BCC or RESP) and assigned to appropriate force fields [19]

- Solvation in explicit water boxes with minimum 15 Å padding [20]

- Neutralization with counterions and addition of salt to physiological concentration (150 mM) [20]

Simulation Protocol:

- Energy minimization with restrained heavy atoms [20]

- Gradual heating from 100 to 300 K [20]

- Equilibration in NPT ensemble with reducing restraints [20]

- Production runs using Hamiltonian replica exchange with solute tempering (REST) to enhance sampling [19]

- Aggregate simulation times of hundreds of nanoseconds per system [19]

Analysis:

- Calculation of relative binding free energies between congeneric compounds [19]

- Comparison with experimental measurements using MUE, RMSE, and correlation coefficients [19]

- Assessment of convergence through statistical analysis [6]

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To address inadequate sampling—a key limitation in biomolecular simulations—several enhanced sampling methods are employed:

- Replica-Exchange MD (REMD): Multiple replicas at different temperatures are simulated in parallel, with exchanges attempted according to the Metropolis criterion [20]

- Umbrella Sampling: Bias potentials along predefined collective variables allow efficient exploration of barrier regions [18]

- Metadynamics: History-dependent bias potentials are added to encourage escape from local minima [18]

- Accelerated MD: Potential surface is modified to lower energy barriers [18]

These methods help overcome the timescale limitations of conventional MD, particularly for large-scale conformational changes.

Visualization of Force Field Selection and Application Workflow

Force Field Selection Workflow

This workflow illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate force fields based on the biomolecular system and research objectives, highlighting how different force field types are suited to specific applications.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Force Field Applications

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Component | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Force Fields | Describes intramolecular and intermolecular interactions for proteins | AMBER ff19SB, ff14SB [20]; CHARMM c36, c22/CMAP [20]; Selection depends on system and property of interest |

| Water Models | Represents solvent effects and solvation properties | TIP3P [19], SPC/E [19], TIP4P-EW [19], OPC [20]; Significantly impacts electrostatic properties and pKa prediction [20] |

| Charge Methods | Assigns partial atomic charges for small molecules | AM1-BCC [19], RESP [19]; RESP can be more accurate but may require careful parameterization [19] |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Accelerates conformational sampling and barrier crossing | Replica exchange [18], Umbrella sampling [18], Metadynamics [18]; Essential for achieving convergence in binding free energies |

| Validation Datasets | Benchmarks force field performance against experimental data | JACS set [19], pKa benchmarks [20]; Critical for assessing transferability and limitations |

Key Limitations and Challenges in Current Force Fields

Chemical Diversity and Transferability

Existing molecular representation frameworks in force fields limit the exploration of exponentially expanding chemical space [17]. This manifests particularly in modeling:

- Post-translational modifications: 76 types of PTMs have been identified, encompassing over 200 distinct chemical modifications of amino acids [17]

- Small molecule ligands: Parameters are often developed asynchronously with protein force fields [17]

- Emerging modalities: Molecular glues and PROTACs present challenges for modeling complex three-body systems [17]

Timescale and Sampling Limitations

Despite advances in computing hardware, MD simulations face inherent timescale limitations [18]. Using all-atom models, the accessible timescale is only nanoseconds to milliseconds, which may not capture slow biological processes [18]. While coarse-grained models extend these limits, they sacrifice atomic-level detail [18].

Electrostatic Modeling Challenges

Current additive force fields struggle with modeling polarization and charge transfer effects [17]. This impacts the accurate representation of:

- Buried charges and their solvation [20]

- Salt bridge stability and lifetime [20]

- pKa values of titratable groups [20]

- Ion binding specificity [20]

The field of biomolecular force fields continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions emerging:

Integration of Machine Learning: Machine learning approaches are being widely adopted for force field parametrization, potentially addressing transferability issues [17]. Examples include neural network potentials and message-passing representations of molecules [17].

Polarizable Force Fields: Development of computationally efficient polarizable force fields promises more accurate electrostatic modeling without prohibitive computational cost [17].

Systematic Validation: Community efforts toward standardized reference data and force field validation benchmarks will enable more rigorous comparisons [21].

Automated Parameterization: Approaches to automate or eliminate atom typing—traditionally a manual, labor-intensive process—are gaining traction [17].

In conclusion, while modern force fields have achieved significant accuracy in predicting protein-ligand binding affinities with errors approaching experimental reproducibility, important limitations remain. The optimal choice of force field depends strongly on the specific biological question and system under investigation. Researchers should carefully consider the trade-offs between different force field types and validate predictions against experimental data where possible. As force fields continue to evolve through interdisciplinary approaches, their accuracy and applicability in drug discovery and basic research will further expand.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in structural biology and drug discovery, providing near-realistic insights into the behavior of biological molecules. When validating protein-ligand binding, simulations move beyond static snapshots to capture the dynamic interplay that governs molecular recognition. This guide focuses on three key observables—Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA), and Hydrogen-Bond Occupancy—that provide a foundational framework for interpreting simulation data and assessing the stability and quality of a protein-ligand complex [22].

The Conceptual Foundation: From Trajectories to Validation

At its core, an MD simulation generates a trajectory—a series of snapshots detailing the atomic positions of a molecular system over time. The analysis of this trajectory involves computing specific physicochemical parameters to quantify structural and dynamic changes. The relationship between these observables and the overarching goal of binding validation can be visualized as a cohesive workflow.

Quantifying the Key Observables

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

RMSD measures the average displacement of atoms (typically the backbone) from a reference structure, serving as a primary indicator of structural stability and convergence. A stable or fluctuating RMSD within a defined range suggests the simulation has reached an equilibrium state, while a continual drift may indicate ongoing structural changes [23] [22].

Typical Experimental Ranges (from protein-ligand complex analyses):

| System Component | Median RMSD (Å) | 25th-75th Percentile (IQR) | Interpretation Guide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Backbone | 1.5 - 4.0 | N/A | System is stable and well-equilibrated [22]. |

| Binding Residue Backbone | 1.2 | 0.7 - 1.5 (IQR=0.8) | Core binding site is structurally rigid [22]. |

| Ligand Atoms | 1.6 | 1.0 - 2.0 (IQR=1.0) | Ligand is firmly positioned in the binding pocket [22]. |

Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

SASA quantifies the surface area of a protein or ligand accessible to a water molecule. Changes in SASA can reveal shielding of hydrophobic residues upon binding (a key driving force for affinity) or detect partial unfolding events [22].

Typical Experimental Ranges for Binding Residues:

| SASA Metric | Median Value (Ų) | 25th-75th Percentile (IQR) | Overall Range (Ų) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum SASA | 2.68 | 2.29 - 2.72 (IQR=0.43) | 1.9 - 3.92 [22] |

| Maximum SASA | 3.2 | 3.03 - 3.62 (IQR=0.59) | 1.9 - 3.92 [22] |

Hydrogen-Bond Occupancy

This metric calculates the percentage of simulation time a specific hydrogen bond between the protein and ligand remains formed. High-occupancy H-bonds are critical for binding specificity and affinity, indicating strong, persistent interactions [22] [24].

Statistical Prevalence in Stable Complexes:

| Occupancy Cluster | Simulation Time | Percentage of Residues |

|---|---|---|

| Low Occupancy | 0 - 30 ns | 7.2% |

| Moderate Occupancy | 31 - 70 ns | 6.3% |

| High Occupancy | 71 - 100 ns | 86.5% |

A Comparative Look at MD Software and Analysis Tools

The choice of software can influence the efficiency and scale of MD simulations. The table below benchmarks popular MD engines and specialized analysis tools based on their capabilities and performance.

Software for MD Simulation and Analysis:

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Key Features & Performance | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Simulation | High performance, highly optimized for CPUs & GPUs, comprehensive analysis suite [25] [26] [27]. | Free Open Source (GPL) |

| AMBER | MD Simulation | Specialized for biomolecules, widely used in drug discovery, includes PMEMD for GPU acceleration [25] [28] [26]. | Proprietary / Free |

| NAMD | MD Simulation | Excellent parallel scaling, object-oriented, integrates well with VMD for visualization [25] [28]. | Free for Academic Use |

| OpenMM | MD Simulation | High performance, highly flexible, Python-scriptable, GPU-accelerated [25]. | Free Open Source (MIT) |

| MDAnalysis | Analysis | Python library, flexible trajectory analysis, supports multiple file formats [27]. | Free Open Source |

| MDTraj | Analysis | Python library, fast and efficient, including RMSD calculations [15] [27]. | Free Open Source |

| CPPTRAJ | Analysis | Versatile analysis tool within AmberTools, extensive analysis functions [27]. | Free Open Source |

| gmx_MMPBSA | Free Energy | Python-based, calculates binding free energies (MM/PBSA/GBSA) with GROMACS [27]. | Free Open Source |

Experimental Protocols for Measurement and Analysis

Standard Workflow for Protein-Ligand System Analysis

The following protocol outlines the general steps for setting up, running, and analyzing a protein-ligand complex, leveraging tools like GROMACS or AMBER.

Detailed Methodology:

System Preparation:

- Start with a high-resolution experimental structure (e.g., from the RCSB PDB). A rigorous selection of crystal structures with atomic-level resolution is recommended to minimize bias [22] [29].

- Parameterize the ligand using tools from AMBER or CGenFF. Note that databases like MISATO have shown that roughly 20% of ligands in structural databases require refinement to correct protonation states or heteroatom geometry [29].

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P model) and add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

Equilibration and Production:

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) over 100+ ps under NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) conditions. Then, equilibrate for 100+ ps under NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) to achieve correct solvent density. Allow sufficient time (e.g., 10 ns) for equilibration before data collection [15].

- Production MD: Run a simulation long enough to capture relevant biological processes. For initial binding assessments, simulations often range from 50 ns to several hundred nanoseconds. For analysis, snapshots are typically saved every 10-100 ps, resulting in hundreds to thousands of frames for analysis [15] [22].

Trajectory Analysis:

- RMSD Calculation: After aligning the trajectory to a reference structure (usually the first frame or the crystal structure) to remove global rotation/translation, calculate the RMSD for the protein backbone, binding site residues, and ligand heavy atoms. This can be done with

gmx rmsin GROMACS or thecpptrajmodule in AMBER [23] [27]. - SASA Calculation: Compute the SASA for the binding site residues or the entire ligand over the trajectory. The

gmx sasatool in GROMACS orMDTrajin Python are commonly used for this purpose [27]. - H-Bond Occupancy Calculation: Define donor and acceptor atoms for potential key interactions. Use a tool like

gmx hbondin GROMACS with geometric criteria (e.g., donor-acceptor distance < 3.5 Å, donor-H-acceptor angle > 135°) to determine the existence of an H-bond in each frame. The occupancy is the percentage of time a specific bond is formed [22] [24].

- RMSD Calculation: After aligning the trajectory to a reference structure (usually the first frame or the crystal structure) to remove global rotation/translation, calculate the RMSD for the protein backbone, binding site residues, and ligand heavy atoms. This can be done with

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for conducting robust MD research on protein-ligand systems.

| Item Name | Function & Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Mathematical functions and parameters describing interatomic potentials. | AMBER (e.g., ff19SB), CHARMM, and GROMOS are common for biomolecules. Choice affects conformational sampling and energy accuracy. |

| Explicit Solvent Models | Represent water molecules individually to capture solvation effects. | TIP3P and SPC/E are widely used. Critical for accurate simulation of H-bonding, hydrophobic effect, and ion interactions. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suites (e.g., MDAnalysis, CPPTRAJ) | Software to process and analyze MD trajectory data. | Used to compute observables like RMSD, SASA, and H-bonds. Their flexibility allows for custom analysis scripts [27]. |

| Validation Datasets (e.g., MISATO) | Community benchmarks combining experimental structures with MD and QM data. | Provides a curated set of protein-ligand complexes for method validation and ML training. Includes over 170 μs of MD data [29]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins (e.g., PLUMED) | Library for accelerating rare events and calculating free energies. | Essential for probing binding/unbinding pathways and computing binding affinities beyond standard observables [27]. |

In protein-ligand molecular dynamics (MD) research, the initial stages of system preparation, solvation, and equilibration fundamentally determine the validity and reliability of binding validation outcomes. These preliminary steps, often perceived as merely technical prerequisites, actually establish the physical conditions under which binding events unfold in simulation. Proper execution ensures that observed binding modes, affinity calculations, and mechanistic insights reflect biologically plausible phenomena rather than computational artifacts.

Recent benchmarking studies emphasize that inconsistencies in system setup contribute significantly to variability in free energy calculations across research groups [30]. The "protein-ligand-benchmark" community effort has identified that standardized preparation protocols reduce inter-method variance by up to 40%, enabling more meaningful comparisons between different MD approaches and force fields [30]. This guide synthesizes current best practices with experimental data to objectively compare methodologies, providing researchers with a framework for optimizing these critical preliminary stages in their binding validation workflows.

System Preparation: Architectural Considerations

Initial Structure Curation and Assessment

The selection and preparation of initial protein structures represents the first critical decision point. Research demonstrates that structure quality profoundly impacts downstream binding validation outcomes, particularly for proteins exhibiting conformational flexibility. A recent systematic evaluation of docking protocols revealed that models generated by AlphaFold2 perform comparably to experimentally solved structures in molecular docking when proper quality metrics are applied [31].

Key assessment metrics for starting structures include:

- Interface predictive scores (pDockQ, ipTM) for protein-protein complexes

- Structural completeness regarding binding site residues

- Comparison to apo/holo conformations to identify pre-existing binding-competent states

Studies show that for 16 protein-protein interactions benchmarked, AlphaFold2 models with ipTM+pTM scores >0.7 consistently produced high-quality structures suitable for docking studies (median TM-score: 0.972) [31]. However, using full-length versus truncated proteins significantly impacts model quality, with AFfull models showing decreased pDockQ2 scores (<0.23) due to unstructured regions [31].

Force Field Selection and Parameterization

Force field selection fundamentally determines the physical behavior of simulated systems. Contemporary benchmarks indicate that modern force fields (OPLS3e, CHARMM36, AMBER19SB) have reduced mean unsigned errors in binding free energy calculations to <1.2 kcal/mol for congeneric series [30].

Table 1: Force Field Performance in Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Force Field | Type of Calculation | Average Error (kcal/mol) | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPLS3e | RBFE | <1.2 | Lead optimization for drug-like molecules |

| CHARMM36 | ABFE | 1.0-1.5 | Membrane-associated systems |

| AMBER19SB | RBFE/ABFE | 1.1-1.6 | Diverse protein families |

| GAFF2 | Small molecule parameters | Varies by parent FF | Drug-like molecule parameterization |

The parameterization of novel ligands requires special attention. Best practices recommend deriving partial charges using quantum mechanical methods at the REDF2/6-31G(d) level or higher, with initial conformation searches performed using molecular mechanics force fields (MMFF) to identify the most stable conformers [32]. For l-amino acid-based drug candidates, this approach has successfully produced structures with high similarity to parent compounds (ketorolac) while improving hydrogen bonding capability [32].

Solvation and Ionization: Creating the Physiological Environment

Solvent Model Selection

Solvent models establish the dielectric environment that critically influences electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and binding energetics. The explicit inclusion of water molecules is particularly important for capturing specific hydration effects in binding sites, which can significantly impact ligand affinity [30].

Water displacement during binding remains a challenging phenomenon for free energy calculations, with some studies reporting difficulties in accurately modeling this effect [30]. The use of explicit solvent models (TIP3P, TIP4P-EW) provides more realistic sampling of water-mediated interactions compared to implicit solvation approaches, though at increased computational cost.

For the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein system, employing explicit TIP3P water in a triclinic box with 1.5 nm padding ensured complete coverage of the flexible receptor-binding domain during simulations [33]. This approach maintained physiological conditions while allowing for natural protein dynamics.

Ionization and Ionic Strength

Proper system ionization establishes physiological ionic strength and neutralizes system charge. The multiscale simulation approach developed for protein-ligand binding kinetics utilizes particle mesh Ewald (PME) for long-range electrostatic interactions combined with appropriate ion concentrations to match experimental conditions [34].

Table 2: Solvation Protocol Impact on Binding Kinetics Calculations

| Solvation Parameter | Settings | Impact on k~on~ Calculation | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Model | TIP3P vs. TIP4P | <5% variation in association rates | General binding studies |

| Ionic Strength | 0.15M NaCl | Shields unrealistic electrostatics | Physiological simulations |

| Box Type | Triclinic vs. Dodecahedron | Minimal effect with sufficient padding | Membrane systems |

| Neutralization | Counterions only vs. Added salt | Significant for charged binding interfaces | Nucleic acid systems |

Benchmarking studies recommend using ion concentrations that match experimental conditions (typically 0.15M NaCl for physiological studies), as this significantly affects electrostatically steered associations while having minimal impact on hydrophobic-driven binding [34]. For the trypsin-benzamidine complex, proper ionization was critical for obtaining k~on~ values within a factor of 3 of experimental measurements (calculated: (8.6 ± 0.7) × 10⁶ M⁻¹ s⁻¹ vs. experimental: 2.9 × 10⁷ M⁻¹ s⁻¹) [34].

Equilibration Protocols: Achieving Stable Starting Conditions

Minimization and Thermalization

Gradual relaxation of constraints prevents unrealistic forces that can distort binding site geometry. The combined Brownian dynamics (BD) and molecular dynamics (MD) pipeline employs careful minimization and thermalization to generate stable starting configurations for binding kinetics calculations [34].

A recommended protocol consists of:

- Steepest descent minimization (5,000 steps) with positional restraints on protein heavy atoms

- Solvent relaxation with restrained protein and ligands

- Gradual thermalization from 0K to target temperature over 100ps

- Gradual release of restraints in a stepwise manner

This approach has demonstrated improved computational efficiency while preserving accuracy in k~on~ calculations for diverse protein-ligand complexes [34].

Equilibration Assessment Metrics

Validation of proper equilibration requires monitoring multiple thermodynamic and structural properties. The "protein-ligand-benchmark" recommends tracking the following metrics to establish equilibration before production simulations [30]:

- Potential energy stability (drift < 0.1 kJ/mol/ns)

- Temperature and pressure stability (fluctuation within 5% of target)

- Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone (plateau within 2Å)

- Binding site residue stability specifically for key interaction residues

For the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein system, equilibration was confirmed when the RMSD of the receptor-binding domain plateaued at approximately 1.5Å, indicating structural stability before production simulations [33]. Similarly, in the design of l-amino acid-based alternatives to ketorolac, RMSD and RMSF plots confirmed the stability of the dynamic structure of the substituted ligand before binding analysis [32].

System Preparation and Equilibration Workflow

Comparative Analysis: Methodological Impact on Binding Validation

Solvation Method Comparison

Different solvation approaches significantly impact the accuracy and efficiency of binding calculations. A comparative analysis of implicit versus explicit solvation revealed trade-offs between computational cost and predictive accuracy for binding free energies.

Table 3: Solvation Method Performance in Binding Studies

| Solvation Method | Setup Complexity | Computational Cost | Binding Affinity Accuracy | Recommended Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit TIP3P | High | 100% (reference) | High (reference) | Binding kinetics, Water-mediated interactions |

| Explicit TIP4P | High | 110-120% | Similar to TIP3P | Polar binding sites |

| GB/SA Implicit | Medium | 10-20% | Moderate (RMSE 1.5-2.5 kcal/mol) | Initial screening, Large-scale FEP |

| PBSA Implicit | Medium | 15-25% | Moderate to High | End-point calculations |

For absolute binding free energy (ABFE) calculations, explicit solvent models remain the gold standard, with OPLS3e achieving errors <1.2 kcal/mol on curated benchmark sets [30]. However, advanced implicit solvent models like GBSA offer reasonable approximations for relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations at substantially reduced computational cost, particularly for lead optimization series involving congeneric ligands [30].

Equilibration Protocol Efficacy

The relationship between equilibration quality and binding validation outcomes can be quantified through specific benchmark metrics. Inadequate equilibration consistently produces artifactual binding poses and inaccurate affinity predictions.

A systematic study of 8 protein targets and 199 ligands demonstrated that proper equilibration protocols reduced calculation variance by 30% compared to minimal equilibration [30]. Specifically, for the trypsin-benzamidine complex, which requires careful treatment of charged binding interfaces, extended equilibration (≥5ns) was necessary to obtain k~on~ values within a factor of 3 of experimental measurements [34].

The hybrid Brownian dynamics-molecular dynamics approach demonstrates that efficient equilibration of encounter complexes significantly improves association rate calculations, with optimized sampling reducing MD simulation time while preserving accuracy [34]. This method has been validated across diverse protein-ligand complexes varying in size, flexibility, and binding properties.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 Force Field | Defines atomic interactions | Protein-ligand MD simulations |

| AMBER19SB Force Field | Alternative protein force field | Comparative binding studies |

| GAFF2 Parameters | Small molecule parameterization | Drug-like molecule simulations |

| TIP3P Water Model | Explicit solvent representation | Physiological binding conditions |

| Particle Mesh Ewald | Long-range electrostatics | Accurate Coulombic interactions |

| LINCS Algorithm | Bond constraint management | Enables longer time steps |

| AlphaFold2 Models | Protein structure source | When experimental structures unavailable |

| GROMACS | MD simulation engine | High-performance molecular dynamics |

| SEEKR | BD-MD hybrid methodology | Binding kinetics calculations |

System preparation, solvation, and equilibration collectively form the critical foundation for valid protein-ligand binding studies using molecular dynamics. The experimental data and comparative analyses presented demonstrate that methodological choices in these preliminary stages significantly impact binding mode prediction, affinity calculation accuracy, and ultimately, the reliability of scientific conclusions drawn from simulations.

By adopting the standardized benchmarking approaches and quality control metrics outlined here, researchers can enhance the reproducibility and predictive power of their binding validation studies. As the field progresses toward more complex binding targets, including protein-protein interfaces and membrane-associated systems, these foundational practices will become increasingly vital for generating biologically meaningful insights from computational approaches.

Methodologies in Action: A Practical Guide to Binding Free Energy Calculations

In the field of computational drug discovery, the accurate prediction of how tightly a small molecule binds to its protein target is a fundamental challenge. Binding free energy calculations, grounded in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, provide a powerful in silico tool for this purpose. These methods primarily fall into two categories: Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations, which predict the binding affinity of a single ligand, and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations, which predict how a chemical modification affects the binding affinity between two or more ligands [35]. The choice between these approaches has profound implications for a project's computational strategy, cost, and likelihood of success. This guide provides an objective comparison of both methodologies, detailing their theoretical bases, applicable use cases, performance, and practical implementation, to help researchers validate protein-ligand binding effectively.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) Calculations

ABFE calculations aim to directly compute the standard binding free energy ((\Delta Gb^\circ)) for a single protein-ligand complex. This quantity is related to the experimental binding affinity ((Ka)) by the equation:

[\Delta Gb^\circ = -RT \ln(KaC^\circ)]

where (R) is the gas constant, (T) is the temperature, and (C^\circ) is the standard-state concentration (1 M) [35].

The core of many ABFE methods involves simulating a non-physical, or alchemical, pathway to decouple the ligand from its environment. A common strategy is the Double Decoupling Method (DDM), where the ligand is first decoupled from the bulk solvent and then from the protein binding site, or vice versa [35] [36]. During this process, the ligand's interactions with its surroundings are gradually turned off. To improve sampling efficiency and convergence, restraining potentials are often applied to control the ligand's position, orientation, and conformation within the binding site [37] [36]. The free energy contributions of applying and removing these restraints are accounted for analytically to yield the final binding free energy.

An alternative to the alchemical route is the geometrical pathway. In this approach, the ligand is physically separated from the protein along a carefully chosen coordinate, and the potential of mean force (PMF) is computed to obtain the free energy change [37]. Both routes, when executed correctly, yield equivalent results [37].

Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Calculations

In contrast, RBFE calculations do not aim to compute a binding free energy from first principles. Instead, they exploit the similarity between two ligands to compute the difference in their binding free energies ((\Delta\Delta G_{bind})) [38]. This is achieved through the use of a thermodynamic cycle, which allows the replacement of a physical binding process with computationally tractable alchemical transformations.

The relevant cycle for RBFE is shown in the diagram below. The direct calculation of (\Delta G{bind}^{L2} - \Delta G{bind}^{L1}) is challenging. Instead, the vertical legs of the cycle are computed: the alchemical transformation of L1 into L2 is performed both in the protein's binding site ((\Delta G{complex}^{L1 \rightarrow L2})) and in solution ((\Delta G{solvent}^{L1 \rightarrow L2})). The relative binding free energy is then given by:

[\Delta\Delta G{bind}^{L1 \rightarrow L2} = \Delta G{complex}^{L1 \rightarrow L2} - \Delta G_{solvent}^{L1 \rightarrow L2}]

This approach is advantageous because the alchemical transformation between two similar ligands typically involves a smaller perturbation, leading to faster convergence and higher precision compared to ABFE [35] [38].

Two primary methodologies exist for executing these alchemical transformations. The more traditional equilibrium free energy perturbation (FEP) uses discrete, parallel simulations at multiple intermediate states (lambda values) along the alchemical path [39]. Conversely, non-equilibrium switching (NES) involves running many independent, short simulations that rapidly drive the system from one end state to the other, with the free energy estimated from the work distribution of these "fast switches" [39] [40]. NES is particularly well-suited for highly parallel computing environments [40].

A key development in RBFE is the Common Core/Serial-Atom-Insertion (CC/SAI) approach, implemented in tools like transformato [38]. Instead of transforming one ligand directly into another, both are mutated to a shared, non-physical intermediate or "common core." This method simplifies the handling of differing atom counts and can be more easily deployed across different MD engines [38].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental thermodynamic cycle underlying RBFE calculations and contrasts the traditional direct transformation with the CC/SAI approach.

Comparative Analysis and Practical Application

Direct Comparison of ABFE and RBFE Approaches

The decision to use ABFE or RBFE is primarily dictated by the drug discovery context, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: A direct comparison of Absolute vs. Relative Binding Free Energy calculations.

| Feature | Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Predict the absolute binding affinity of a single ligand [35]. | Predict the change in binding affinity between two or more ligands [38]. |

| Typical Use Case | Virtual screening of diverse compounds [41]; systems without a known reference ligand. | Lead optimization within a congeneric series [35] [39]. |

| Ligand Requirements | Can be applied to any ligand, regardless of structural similarity to others. | Requires chemically similar ligands with a shared core structure [35] [38]. |

| Computational Cost | High per compound (often days of simulation) [37]. | Lower per perturbation when comparing similar compounds [35]. |

| Typical Accuracy | Challenging to achieve errors < 1 kcal/mol; more prone to sampling issues [35]. | Highly accurate for similar ligands; often achieves errors of ~1 kcal/mol or less [39] [38]. |

| Key Challenges | Requires a high-quality ligand pose; capturing full protein and ligand flexibility [41] [35]. | Designing alchemical paths for dissimilar ligands; managing large binding mode changes [35]. |

| Pose Dependency | Highly dependent on a correct initial binding pose [41]. | Less sensitive if binding mode is conserved across the series. |

Performance and Validation Data

Both methods have been rigorously validated against experimental data. A 2022 study on ABFE demonstrated its utility as a post-docking filter. After docking ~70,000 compounds for targets BACE1, CDK2, and thrombin, ABFE calculations successfully improved the enrichment of true active compounds over decoys compared to docking scores alone [41]. This shows that ABFE can add significant value in a virtual screening context, though it relies on good initial poses.

RBFE methods have matured to a point where they are considered a "gold standard" for lead optimization. A study on the transformato package, which uses the CC/SAI approach, reported an overall root-mean-squared error (RMSE) of 1.17 kcal/mol and a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.73 across 76 relative binding free energy differences for five different protein-ligand systems [38]. This level of accuracy is sufficient to guide synthetic decisions in a drug discovery project.

Another critical factor for successful RBFE calculations is the quality of the initial ligand pose. Research has shown that both commercial (e.g., Glide) and open-source (e.g., AutoDock Vina) docking engines can generate poses that lead to good correlation with experimental data, especially when using constraints based on a maximum common substructure (MCS) to maintain a consistent binding mode [39].

Decision Workflow and Emerging Trends

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for choosing between ABFE and RBFE based on the research objective and ligand set characteristics.

The field of binding free energy calculations is rapidly evolving. Key trends aim to address the primary limitation of these methods: their computational expense.

- Machine Learning and Enhanced Sampling: The integration of machine learning with enhanced sampling methods is a powerful strategy to reduce simulation time. ML can help identify relevant collective variables or generate pathways, while enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics help overcome energy barriers more efficiently [35] [42].

- Kinetics-Enabled Methods: While most methods focus on binding affinity (a thermodynamic property), drug efficacy is also influenced by the binding residence time (a kinetic property). New methods like ModBind are being developed to predict ligand dissociation rates ((k_{off})) in a high-throughput manner, offering a more holistic view of molecular efficacy [43].

- Dynamic Docking: Traditional docking treats proteins as rigid, which is a major limitation. New deep learning methods like DynamicBind can predict ligand-specific protein conformational changes, effectively performing "dynamic docking" to generate more realistic complex structures for subsequent free energy calculations [44].

Essential Research Toolkit

Success in free energy calculations relies on a combination of software tools, force fields, and careful experimental design.

Table 2: Key research reagents and software solutions for free energy calculations.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to ABFE/RBFE |

|---|---|---|---|

| BFEE2 [37] | Software | Automated setup of ABFE calculations via geometrical or alchemical routes. | ABFE |

| Transformato [38] | Software | Setup of RBFE calculations using the Common Core approach; engine-independent. | RBFE |

| OpenMM [43] | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulation library, often used as a backend for FEP. | Both |

| PMX [40] | Software Library | Automated protein and ligand topology generation for alchemical transformations. | RBFE |

| GAFF/GAFF2 [39] [43] | Force Field | General Amber Force Field for small molecules. | Both |

| Glide [41] [39] | Docking Software | Generation of initial ligand poses for ABFE or RBFE setup. | Both |

| AutoDock Vina [39] [43] | Docking Software | Open-source alternative for generating initial ligand poses. | Both |

| Icolos [39] | Workflow Manager | Orchestrates end-to-end automated RBFE workflows from SMILES strings. | RBFE |

The choice between absolute and relative binding free energy calculations is not a matter of which method is superior, but which is the right tool for the task at hand. RBFE is the undisputed champion for lead optimization, where it provides highly accurate affinity predictions for congeneric series with manageable computational cost. In contrast, ABFE is a versatile tool for virtual screening and projects without a known reference ligand, though it demands more computational resources per compound and is highly sensitive to the initial binding pose.

The future of binding free energy calculations lies in the increasing integration of these rigorous physics-based methods with machine learning, the rise of kinetics-aware protocols, and the development of more automated and robust workflows. These advancements are steadily transforming free energy calculations from a specialized research tool into a more routine component of the computational drug discovery pipeline.

Automating Workflows with Tools like BAT.py for High-Throughput Screening

The accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity is a central challenge in structure-based drug design. While molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an atomistic view of binding interactions, translating these simulations into reliable binding free energy estimates has traditionally required significant expertise and computational resources. The emergence of automated tools like BAT.py represents a paradigm shift, offering researchers standardized, reproducible pipelines for binding affinity calculation. This guide objectively compares BAT.py's performance and methodology against other available approaches, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to select appropriate tools for their high-throughput screening projects.

The critical need for such tools stems from a well-defined "methods gap" in the binding affinity prediction landscape. At one extreme, molecular docking offers speed (under one minute on CPU) but limited accuracy (2–4 kcal/mol RMSE, correlation coefficients around 0.3). At the other extreme, rigorous alchemical methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) provide high accuracy (RMSE ~1 kcal/mol, correlation >0.65) but require prohibitive computational resources (12+ hours of GPU time per compound). This landscape creates a pressing need for methods that offer intermediate levels of accuracy and throughput suitable for screening thousands of compounds [15].

Tool Comparison: BAT.py Versus Alternative Workflow Solutions

Automated tools for binding free energy calculations differ substantially in their methodological approaches, compatibility with simulation packages, and supported free energy protocols. The table below provides a systematic comparison of BAT.py against other computational frameworks.

Table 1: Comparison of Automated Workflow Tools for Binding Free Energy Calculations

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | MD Engine Compatibility | Free Energy Methods | Automation Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAT.py | Alchemical pathway (DD/SDR) | AMBER, OpenMM | Absolute (ABFE), Relative (RBFE) | End-to-end automation [45] |

| MM/GBSA | End-state approximation | Various | Binding energy estimation | Manual trajectory analysis [15] |

| LABind | Machine learning prediction | Structure-based only | Binding site identification | No MD required [16] |

| Active Learning Frameworks | MD simulations with iterative screening | Custom | Target-specific scoring | Partial automation [46] |

BAT.py distinguishes itself through its comprehensive automation and methodological flexibility. It supports both Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations via double decoupling (DD) or simultaneous decoupling and recoupling (SDR) methods, and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) calculations using both common-core and SepTop approaches. This versatility enables applications ranging from ranking diverse ligands to refining docked poses [45]. Unlike end-state methods such as MM/GBSA, which approximate binding free energies by combining gas-phase enthalpies and solvent corrections with often problematic entropy estimates, BAT.py employs rigorous alchemical transformations that provide a more physically realistic binding affinity assessment [15].

LABind represents a fundamentally different approach, utilizing graph transformers and cross-attention mechanisms to predict binding sites in a ligand-aware manner. While not a direct competitor for free energy calculations, it exemplifies the growing integration of machine learning in structural analysis. Its ability to generalize to unseen ligands demonstrates how ML approaches can complement physics-based methods like BAT.py [16].

Emerging active learning frameworks combine MD simulations with iterative screening to dramatically reduce computational costs. One recent approach reduced the number of compounds requiring experimental testing to less than 20 by leveraging target-specific scoring and extensive MD simulations to generate receptor ensembles. This method achieved a 29-fold reduction in computational costs while successfully identifying a potent TMPRSS2 inhibitor (IC50 = 1.82 nM), demonstrating the power of integrating automation with strategic sampling [46].

Performance Benchmarks: Experimental Data and Validation

Quantitative performance validation is essential for selecting appropriate computational tools. The table below summarizes key benchmark results for BAT.py and alternative approaches across various test systems.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

| Method | Test System | Accuracy Metric | Correlation with Experiment | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAT.py (ABFE) | BRD4(2) ligands | Ranking agreement | Good correlation | ~8000 GPU hours (ensemble) [45] |

| Docking | General protein-ligand | RMSE: 2-4 kcal/mol | ~0.3 | <1 minute CPU [15] |

| FEP/TI | General protein-ligand | RMSE: ~1 kcal/mol | >0.65 | >12 hours GPU per compound [15] |

| MM/GBSA | Validation set | Incorrect coefficient signs | Poor correlation | Moderate [15] |

| Active Learning + MD | TMPRSS2 inhibitors | IC50 = 1.82 nM | Experimental validation | 29-fold reduction vs. brute force [46] |

BAT.py has demonstrated particular effectiveness in ranking ligand affinities for the BRD4(2) system. Experimental binding free energies for this benchmark system range from -5.2 kcal/mol to -11.4 kcal/mol across five ligands. BAT.py calculations typically show good correlation with these experimental values, albeit with a slight systematic overestimation of binding affinities. This performance profile makes it particularly valuable for relative ranking in virtual screening campaigns [45].