Whole-Cell Molecular Dynamics Simulations: From Digital Cells to Drug Discovery

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have progressed from modeling individual proteins to encompassing entire cells, offering an unprecedented computational microscope for biomedical research.

Whole-Cell Molecular Dynamics Simulations: From Digital Cells to Drug Discovery

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have progressed from modeling individual proteins to encompassing entire cells, offering an unprecedented computational microscope for biomedical research. This article explores the foundational principles, methodologies, and applications of whole-cell MD, focusing on groundbreaking models of minimal cells like JCVI-syn3A. It details the integrative workflows and coarse-grained force fields, such as Martini, that make these massive simulations feasible. For researchers and drug development professionals, the article provides critical insights into overcoming computational challenges, validating simulations against experimental data, and leveraging these digital cells to uncover novel biological mechanisms and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Digital Cell Revolution: Foundations of Whole-Cell Molecular Dynamics

I will organize the content to show the evolution from single proteins to cellular scales, using the most current and authoritative sources. The minimal cell JCVI-syn3A from [1] provides a perfect framework for the cellular scale context. Other search results [2] [3] [4] provide foundational and methodological details for different aspects of MD simulations.

The structure will flow logically:

- Abstract and Introduction establish the field's evolution and the thesis context.

- A historical table quantifies the scale progression.

- Application Notes focus on the entire cell simulation as the current frontier.

- Protocols provide detailed methodologies for different simulation types.

- Visualizations illustrate key workflows.

- The toolkit table synthesizes essential resources.

All elements will be integrated to create a cohesive, technically detailed document for a research audience. */}

From Single Proteins to Cellular Scales: The Evolution of MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have undergone a remarkable evolution, progressing from studying isolated proteins in the 1970s to the current brink of modeling entire cells. This expansion in spatial and temporal scale, driven by advances in computing hardware, force fields, and algorithms, has transformed MD into a indispensable computational microscope for molecular biology and drug discovery. This article details key application notes and provides specific protocols that have enabled this progression, framing the discussion within the ambitious goal of achieving realistic simulations of a complete minimal cell, JCVI-syn3A. We present structured data on simulation scales, detailed methodologies for system setup, and visual workflows to guide researchers in this rapidly advancing field.

The impact of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in molecular biology and drug discovery has expanded dramatically in recent years [4]. These simulations capture the behavior of proteins and other biomolecules in full atomic detail and at very fine temporal resolution, effectively acting as a computational microscope [1]. The first MD simulation of a protein, the bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (58 residues), was achieved in 1977 for a mere 9.2 picoseconds [2]. Early applications were constrained to simple systems and picosecond timescales, but modern simulations now access microseconds and milliseconds, involving systems of hundreds of millions of atoms [2] [4].

The natural next frontier for MD is the scale of entire cells [1]. This goal represents a profound challenge, as it requires integrating a hierarchy of interconnected biomolecular processes. The current state-of-the-art is demonstrated by ongoing efforts to model an entire minimal cell, JCVI-syn3A—a synthetic organism with only 493 genes—using a coarse-grained approach [1]. This perspective frames the evolution of MD applications and protocols within this ultimate objective: simulating cellular function at molecular resolution.

Quantitative Evolution of MD Simulation Capabilities

The table below summarizes the key quantitative milestones in the evolution of MD simulations, highlighting the exponential growth in system size and simulation timescale.

Table 1: Evolution of MD Simulation Scale and Complexity

| Simulation Focus | Approximate System Size | Achieved Timescale | Key Significance | Representative Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Protein (BPTI) | ~1,000 atoms | 9.2 ps | First simulation of a protein | [2] |

| Liquid Argon | 864 atoms | ps-scale | Early simple system simulation | [2] |

| GPCRs / Ion Channels | 10,000s - 100,000s of atoms | µs-scale | Routine for drug target proteins | [4] |

| Gene-scale (Atomistic) | ~1 billion atoms | ns-scale | First atom-scale simulation of an entire gene | [2] |

| Viral Envelope | ~160 million atoms | 121 ns | One of the largest atomistic simulations | [2] |

| Entire Minimal Cell (JCVI-syn3A, CG) | ~550 million particles (6 billion atoms) | N/A (Model Construction) | Integrative model of a complete cell | [1] |

Application Notes: From Drug Discovery to Whole-Cell Modeling

Drug Discovery and Development

MD simulations have become invaluable in the modern drug development process [2]. They provide atomic-level insights that are often difficult to obtain experimentally:

- Target Validation and Mechanism: MD studies offer crucial insights into the dynamics and function of drug targets like sirtuins, RAS proteins, and intrinsically disordered proteins [2].

- Ligand Binding Energetics and Kinetics: In the lead optimization phase, MD facilitates the evaluation of the binding energetics and kinetics of ligand-receptor interactions, guiding the selection of the best candidate molecules [2]. Methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) are used to estimate the standard Gibbs free energy of binding (∆bG⊖) [2].

- Membrane Protein Environments: Simulations that include the biological lipid bilayer are critical for studying major drug target classes like G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels [2] [4].

Characterizing Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)

MD simulations are a powerful tool for studying the structural and dynamical implications of post-translational modifications (PTMs) like phosphorylation and ubiquitination [3]. They can capture the dynamic behavior of biological systems at atomistic resolution in a label-free manner, allowing researchers to compare the effects of different PTM states by carefully controlling simulation conditions [3]. This is typically experimentally unfeasible for a wide variety of PTMs simultaneously. MD can reveal how PTMs alter protein stability, allosteric communication, and interaction networks [3].

The Frontier: Molecular Dynamics of an Entire Cell

The most advanced application of MD is the construction and simulation of a whole-cell model [1]. The chosen model system is the JCVI-syn3A minimal cell, which has a diameter of about 400 nm and a simplified genome of 493 genes [1]. Key aspects of this endeavor include:

- Integrative Modeling Workflow: Building a whole-cell model requires integrating vast amounts of experimental data (CryoET, Cryo-EM, -Omics data) to inform the in silico model [1].

- Coarse-Graining for Feasibility: An atomistic simulation of Syn3A is currently computationally intractable, requiring modeling for more than six billion atoms. Instead, the Martini coarse-grained (CG) force field is employed, which uses a four-to-one mapping of heavy atoms to CG beads, speeding up simulations by about three orders of magnitude [1]. The Syn3A model requires about 550 million CG particles [1].

- The Martini Ecosystem: A suite of software tools has been developed to build cellular models:

- Martinize2: For high-throughput generation of Martini topologies and coordinates for proteins [1].

- Polyply: For efficiently setting up polymer systems like chromosomal DNA from sequence [1].

- Bentopy: A tool under development for generating dense, random packings of proteins within volumetric constraints in the cytosol [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: MM/PBSA Binding Free Energy Calculation

The Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) method is a popular, albeit approximate, technique for calculating binding free energies from MD trajectories [5].

1. Principle: The binding free energy (ΔG_bind) is calculated as the difference between the free energy of the complex and the isolated receptor and ligand in solvent. The potential of mean force W is given by:

- W = EMM + ΔGpolar + ΔGnonpolar [5]

- EMM: The molecular mechanics energy from a standard force field.

- ΔGpolar: The polar solvation free energy, computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation.

- ΔGnonpolar: The non-polar solvation free energy, taken to be proportional to the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), i.e., γA, where γ is a surface tension parameter [5].

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: System Preparation. Create the solvated receptor-ligand complex, receptor alone, and ligand alone.

- Step 2: MD Simulation. Run a standard explicit-solvent MD simulation for the complex to sample conformations. Multiple, shorter simulations can also be used (ensemble approach).

- Step 3: Trajectory Snapshot Extraction. Extract a set of snapshots (e.g., every 100 ps) from the stable (production) part of the trajectory.

- Step 4: Free Energy Calculation. For each snapshot:

- Remove solvent and counterions.

- Calculate the EMM term using the molecular mechanics force field.

- Calculate the ΔGpolar term by solving the PB equation for the snapshot in vacuum and in solvent using a PB solver (e.g., UHBD or APBS).

- Calculate the ΔG_nonpolar term by computing the SASA and multiplying by γ.

- Step 5: Averaging. Average the individual energy components over all snapshots for the complex, receptor, and ligand. The final ΔG_bind is the average over the trajectory.

3. Critical Parameters and Notes:

- Dielectric Constant: The choice of the internal solute dielectric constant (ε_in) is critical. Values >1.0 (e.g., 2-4 for proteins) are often necessary to account for electronic polarization and atomistic flexibility not captured by the force field [5].

- Sampling: The method assumes that the simulation adequately samples the relevant conformational space. Inadequate sampling is a major source of error.

- Entropy: The entropic contribution (often calculated via normal mode analysis or quasi-harmonic approximation) is computationally expensive and is sometimes omitted for high-throughput screening, yielding "effective" binding energies.

Protocol: Building a Coarse-Grained Model for Whole-Cell Simulation

This protocol outlines the integrative modeling workflow for constructing a CG model of the JCVI-syn3A cell using the Martini ecosystem [1].

1. Data Curation and Integration:

- Collect all available experimental data on the Syn3A cell. This includes:

2. Mesoscale Modeling:

- Use a pre-existing kinetic model of the whole JCVI-syn3A to gain quantitative insights into cellular processes and composition. This informs the molecular abundances needed for the molecular model [1].

3. Molecular Model Generation with the Martini Ecosystem:

- Proteins:

- For each unique protein in the proteome, obtain an atomistic structure (from experiment or prediction).

- Use Martinize2 to automatically generate a Martini CG topology and coordinates for each protein [1].

- Chromosomal DNA:

- Use Polyply to generate the double-stranded DNA topology and initial coordinates directly from the genome sequence using a specialized biased random walk protocol [1].

- Lipids and Metabolites:

4. System Assembly:

- Use Bentopy to pack the generated proteins, protein complexes, and metabolites into the cytoplasmic volume, respecting their functional annotations and abundances [1]. The tool uses an efficient collision detection scheme to generate a crowded, realistic cytosol.

- Assemble the cell membrane from the appropriate lipid types using the Martini lipidome.

- Insert the folded chromosomal DNA into the assembled cytoplasm.

5. Simulation Setup:

- The final assembled system will contain approximately 550 million CG particles. The simulation will require massive parallelization on high-performance computing (HPC) resources, likely leveraging GPU acceleration.

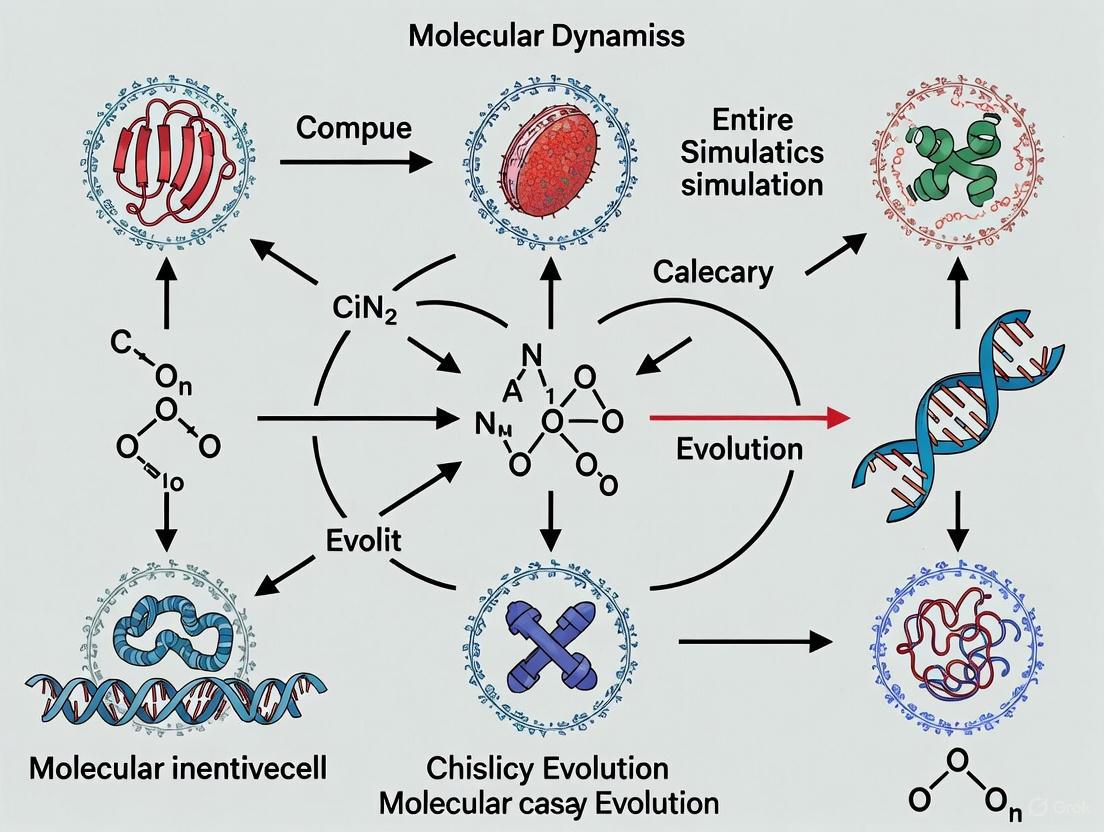

Diagram 1: Integrative modeling workflow for building an entire cell model. The process begins with experimental data, informs a mesoscale model, generates molecular components, and finally assembles the complete system.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Whole-Cell Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [2] | Software Package | A high-performance MD engine for simulating molecular systems. | Core simulation software for running large-scale simulations. |

| Martini Force Field [1] | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Represents ~4 heavy atoms with one bead, greatly accelerating simulation. | Enables feasible simulation of cellular-scale systems like JCVI-syn3A. |

| Martinize2 [1] | Software Tool | Automates the generation of Martini coarse-grained models from atomistic protein structures. | High-throughput topology generation for the entire proteome. |

| Polyply [1] | Software Tool | Generates topologies and coordinates for polymers, including chromosomal DNA, from sequence. | Constructing the large genomic DNA polymer of a cell. |

| Vermouth [1] | Software Library | A central Python library for graph-based molecular manipulation; underpins Martinize2 and Polyply. | Provides the unified framework for handling molecules in the Martini ecosystem. |

| Bentopy [1] | Software Tool (in dev) | Generates dense, random packings of biomolecules within defined volumes. | Packing the cytoplasm with proteins and metabolites at realistic concentrations. |

| MM/PBSA [5] | Computational Method | Calculates binding free energies from MD trajectories using an implicit solvent model. | Useful in drug discovery for evaluating ligand-protein interactions. |

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for setting up and running a coarse-grained MD simulation using the Martini force field and its associated tools.

Why Whole-Cell Modeling? The Scientific Drive for a Holistic View

The quest to understand the fundamental units of life—cells—in their complete complexity represents one of the most ambitious goals in modern science. Whole-cell modeling emerges as a transformative approach that aims to comprehensively predict how cellular phenotypes emerge from genotype by representing the entire genome, the structure and concentration of every molecular species, each molecular interaction, and the extracellular environment [6]. This paradigm shift from studying isolated cellular components to modeling the cell in its entirety promises to bridge critical gaps in our understanding of biological systems, enabling unprecedented predictive capabilities in bioengineering and precision medicine [7] [8]. The driving vision is to create a computational microscope that reveals the dynamics of all cellular components with ultimate resolution, offering a holistic view of cellular function that transcends what can be observed through conventional experimental methods alone [1].

The scientific community's pursuit of whole-cell modeling is fueled by the recognition that biological functions emerge from the intricate, multi-scale interactions between cellular components [1] [9]. While traditional reductionist approaches have yielded profound insights into specific pathways and mechanisms, they inevitably fall short of capturing the system-level behaviors that characterize living systems. By integrating the collective knowledge of individual cellular processes into a unified framework, whole-cell models offer a pathway to understand how perturbations at the molecular level—such as genetic mutations, drug treatments, or environmental changes—propagate through the system to influence observable cellular phenotypes [10] [9]. This integrative approach is poised to revolutionize how we investigate, manipulate, and ultimately understand the fundamental processes of life.

The Scientific Imperative: Key Drivers for Whole-Cell Modeling

From Isolated Pathways to Integrated Cellular Function

Cellular processes are traditionally studied and modeled as separate networks with heterogeneous levels of detail, such as metabolic networks, protein-protein interaction networks, and transcription regulation networks [9]. However, these processes are neither physically nor functionally independent; the simple fact that molecular species are shared between them makes their dynamics interdependent [9]. For instance, the intracellular concentration of ATP affects and is affected by several processes simultaneously. Whole-cell modeling addresses this interconnected nature of cellular systems by integrating these disparate processes into a unified representation, enabling researchers to study emergent properties that arise from their interactions [9].

The limitations of studying cellular components in isolation become particularly evident when considering that biomolecular functions emerge from molecular interactions within complex, crowded cellular environments [1]. Experimental techniques, while invaluable, often probe only narrow windows in the space-time continuum of cellular activity [10]. Whole-cell modeling addresses this limitation by providing a unified framework that integrates structural and dynamic data across multiple scales, from molecular interactions to system-level behaviors [10]. This approach allows researchers to investigate how biological macromolecules behave inside cells and navigate a spectrum of specific and non-specific interactions in the presence of various electrolytes, osmolytes, and other small molecules—questions that remain difficult to address through experiment alone [10].

Predictive Power: From Genotype to Phenotype

A primary motivation for whole-cell modeling is the ability to predict cellular phenotypes from genetic information, a fundamental challenge in modern biology [6]. By comprehensively representing the function of each characterized gene product and its interactions within the cellular network, whole-cell models can simulate how genetic variations manifest as observable traits [6]. This predictive capability has profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms, developing therapeutic interventions, and engineering microorganisms for biotechnology applications.

The power of whole-cell models to connect genotype to phenotype extends beyond academic interest to practical applications in drug discovery and personalized medicine. For example, with a comprehensive whole-cell model of a bacterial pathogen like Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), researchers could use computer simulations informed by biological experiments to engineer new prevention and treatment strategies for antibiotic-resistant infections [8]. Similarly, in cancer treatment, a complete cell model of immune cells could enable the fine-tuning of specific anti-tumor responses to improve immunotherapies without invasive exploration of the patient [8]. These applications highlight the transformative potential of whole-cell models in translating basic biological knowledge into clinical and biotechnological advances.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Whole-Cell Modeling

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery & Development | Target identification, mechanism of action studies, toxicity prediction | Reduced development costs, personalized treatment approaches |

| Infectious Disease Research | Modeling of bacterial pathogens (e.g., MRSA), antibiotic resistance mechanisms | Novel therapeutic strategies for drug-resistant infections |

| Cancer Research & Treatment | Cancer immunotherapy optimization, tumor cell behavior prediction | Improved personalized cancer therapies with reduced side effects |

| Industrial Biotechnology | Metabolic engineering, optimization of production strains | Enhanced bioproduction of pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and biofuels |

| Environmental Biotechnology | Biofilm control in water treatment systems | Improved water desalination and purification processes |

Addressing the Multi-Scale Challenge of Biological Systems

Cellular function operates across multiple spatial and temporal scales, from rapid molecular interactions occurring in nanoseconds to slow cellular processes like division that take hours [10] [11]. This multi-scale nature of biological systems presents a fundamental challenge that whole-cell modeling directly addresses by integrating representations across these scales. Where traditional experimental methods struggle to simultaneously capture atomistic detail and cellular context, whole-cell models can incorporate data from diverse sources—including structural biology, omics technologies, and biophysical measurements—into a coherent computational framework [1] [10].

The multi-scale challenge extends beyond temporal considerations to encompass organizational complexity, from individual molecules to macromolecular complexes, organelles, and ultimately the entire cell [11]. Physical whole-cell models that build up from atomic-level structures of individual molecules to system-level representations offer the potential to connect behavior at the molecular level to cellular function through physical laws [10]. This approach provides a more fundamental basis for prediction compared to purely statistical or kinetic models, as it can potentially forecast how specific molecular interventions—such as drug candidates—perturb cellular function without requiring pre-existing assumptions about altered kinetic pathways [10].

Quantitative Landscape: Current Capabilities and Computational Requirements

Model Organisms and Their Complexity

Current whole-cell modeling efforts have focused on relatively simple organisms with minimal genetic complexity, enabling proof-of-concept demonstrations while laying the groundwork for more ambitious applications. The bacterium Mycoplasma genitalium, with its compact genome of approximately 500 genes, served as the first comprehensive whole-cell modeling target, integrating 15 cellular processes into a single modeling framework [9]. This pioneering work demonstrated the feasibility of whole-cell modeling and established methodologies for model construction and validation.

More recently, the minimal synthetic cell JCVI-syn3A, containing only 493 genes, has emerged as a promising model system for whole-cell simulation approaches [1]. With a diameter of approximately 400 nm and a largely resolved molecular composition, JCVI-syn3A represents an ideal testbed for developing and refining whole-cell modeling methodologies, particularly those requiring comprehensive structural and compositional data [1]. The relative simplicity of this system makes it particularly amenable to detailed computational modeling approaches that would be infeasible with more complex organisms.

Table 2: Model Organisms in Whole-Cell Modeling Studies

| Organism | Genome Size (Genes) | Key Features | Modeling Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma genitalium | ~500 | Smallest known genome of any free-living organism | First whole-cell computational model integrating 15 cellular processes [9] |

| JCVI-syn3A | 493 | Synthetic minimal cell with reduced genetic complexity | Atomistic and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations [1] |

| Escherichia coli | ~4,300 | Well-studied model bacterium with extensive experimental data | Initial whole-cell modeling efforts; kinetic models of metabolism [12] |

Computational Requirements and Scaling Challenges

The computational demands of whole-cell modeling vary dramatically depending on the chosen resolution and simulation approach. Atomistic models, which provide the highest level of detail, require simulating enormous numbers of particles—a bacterial cytoplasm model may reach 100 million particles for just 1/10th to 1/20th of the smallest bacterial cell [10]. For complete cells like JCVI-syn3A, coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations using the Martini force field require approximately 550 million coarse-grained particles, corresponding to more than six billion atoms [1].

The computational cost of these simulations presents significant challenges. State-of-the-art supercomputers like Fugaku can achieve approximately 8.3 nanoseconds per day for a 1.6 billion-atom system [11]. Specialized molecular dynamics supercomputers like Anton 3 offer improved performance, with a 512-node machine capable of simulating timescales of milliseconds per day for systems approximating a eukaryotic cell (∼100 trillion atoms) [11]. These computational constraints have driven the development of multi-resolution approaches that combine different levels of molecular detail, applying atomistic resolution only to specific regions of interest while treating the remaining cellular environment with more efficient coarse-grained methods [10] [11].

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols in Whole-Cell Modeling

Integrative Modeling Workflow for Whole-Cell Model Construction

The construction of whole-cell models follows an integrative workflow that synthesizes diverse experimental data into coherent computational representations. This process typically begins with the collection of experimental data from multiple sources, including cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) images, cryo-EM protein structures, and various -omics experiments (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [1]. These data provide essential information about cellular architecture, molecular structures, and composition that informs the subsequent modeling stages.

The second stage involves mesoscale modeling, where kinetic models of cellular processes are developed to gain quantitative insights into cellular processes and composition [1]. These models often employ constraint-based methods, ordinary differential equations, or rule-based approaches to capture the dynamics of metabolic networks, gene expression, and other essential cellular functions. In the final stage, molecular-resolution models of cellular components are generated using specialized software tools, followed by the assembly of individual molecular components in their appropriate abundances into the final whole-cell model [1]. This multi-stage approach allows for the integration of data across spatial and temporal scales, bridging from molecular structure to cellular function.

Diagram 1: Integrative modeling workflow for building in silico whole-cell models, illustrating the three major stages from data collection to final model assembly.

Protocol: Building a Coarse-Grained Whole-Cell Model with the Martini Ecosystem

The Martini coarse-grained force field has emerged as a powerful tool for whole-cell modeling, offering a balance between computational efficiency and molecular detail. The following protocol outlines the key steps for constructing a coarse-grained whole-cell model using the Martini ecosystem:

Step 1: System Preparation and Component Selection

- Select the target organism (e.g., JCVI-syn3A minimal cell) and gather comprehensive compositional data

- Obtain or generate structural models for all macromolecular components (proteins, DNA, RNA)

- Determine the stoichiometry and cellular abundances of all molecular species from experimental data [1]

Step 2: Topology Generation for Cellular Components

- For proteins: Use Martinize2 software to generate Martini topologies and coordinates from atomistic protein structures [1]. This tool performs quality checks on atomistic structures and alerts to potential problems.

- For chromosomal DNA: Employ Polyply software to efficiently generate polymer topologies from sequence data using a multiresolution graph-based approach [1]

- For lipids: Use the Martini Database to access curated parameters for various lipid species [1]

- For metabolites: Apply recently developed Martini parameters for small molecules [1]

Step 3: System Assembly

- Use specialized packing software like Bentopy (currently in development) to generate dense macromolecular solutions within volumetric constraints that reflect cellular crowding [1]

- Incorporate functional annotations to bias spatial distribution of proteins based on known biochemical functions

- Assemble membrane systems using insane tool or similar utilities for building complex membrane architectures [1]

Step 4: Simulation Setup and Execution

- Integrate the assembled system using simulation packages like GROMACS capable of handling large-scale systems

- Implement appropriate simulation parameters accounting for the Martini force field requirements

- Run simulations on high-performance computing resources, potentially leveraging GPU acceleration for improved performance

Step 5: Analysis and Validation

- Compare simulation results with experimental data for validation

- Analyze spatial organization, diffusion characteristics, and emergent behaviors

- Iteratively refine the model based on discrepancies between simulation and experiment

This protocol leverages the growing Martini ecosystem of software tools specifically designed to facilitate the construction of topologies and initial coordinates for running coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations of complex cellular systems [1].

Protocol: Biochemical Network Modeling for Whole-Cell Integration

An alternative approach to whole-cell modeling involves constructing comprehensive biochemical networks that integrate multiple cellular processes. The following protocol outlines the key steps for this methodology:

Step 1: Data Integration and Curation

- Collect organism-specific biochemical data from databases such as WholeCellKB, MetaCyc, BRENDA, and UniProt [9] [6]

- Map known molecular interactions, including metabolic reactions, protein-protein interactions, and transcriptional regulation relationships

- Resolve inconsistencies and gaps in the data through manual curation and literature review

Step 2: Rule-Based Model Specification

- Define reaction rules that can be applied to multiple substrates following rule-based modeling principles [9]

- Develop templates for repetitive processes such as transcription, translation, and replication that can be instantiated for specific genes or macromolecules [9]

- Specify modification rules for post-translational modifications and other chemical alterations

Step 3: Network Generation

- Instantiate the rule set to generate specific biochemical reactions for all molecular components

- Represent the system as a bipartite graph with molecule nodes and reaction nodes connected by edges indicating participation as reactants, products, or modifiers [9]

- Annotate edges with stoichiometric information and regulatory effects

Step 4: Model Validation through Essentiality Prediction

- Implement cascading failure analysis to simulate gene deletions [9]

- Compare predicted essential genes with experimental data from global transposon mutagenesis studies [9]

- Refine the model to improve agreement between predictions and experimental observations

Step 5: Simulation and Analysis

- Employ constraint-based methods such as flux balance analysis to simulate metabolic behavior [12]

- Implement kinetic simulations for dynamic processes where parameter data are available

- Analyze network properties to identify critical nodes, bottlenecks, and functional modules

This biochemical network approach provides a more homogeneous framework for whole-cell modeling compared to hybrid approaches that combine multiple modeling methodologies [9]. It enables a systemic analysis of cells on a broader scale, revealing interfaces between cellular processes that might be obscured in more segregated modeling frameworks.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Whole-Cell Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), Cryo-EM Data Bank, AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Provide atomic-level structural information for proteins and nucleic acids essential for physical modeling [10] [11] |

| Omics Data Resources | WholeCellKB, PaxDb, ECMDB, ArrayExpress | Offer comprehensive datasets on cellular composition, including protein abundances, metabolite concentrations, and gene expression profiles [12] [9] [6] |

| Pathway/Interaction Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, BioCyc, BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Contain curated information about metabolic pathways, regulatory networks, and kinetic parameters [12] [6] |

| Modeling Software & Platforms | Martini Ecosystem (Martinize2, Polyply, Vermouth), E-CELL, Virtual Cell, COPASI, PySB | Provide specialized tools for constructing, simulating, and analyzing whole-cell models at different resolutions [1] [12] [6] |

| Simulation Force Fields | Martini Coarse-Grained Force Field, All-Atom Force Fields (CHARMM, AMBER) | Define interaction parameters between molecular components at different resolutions [1] [10] |

| Standards & Formats | Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML), CellML | Enable model sharing, reproducibility, and interoperability between different modeling tools [12] |

Future Directions: Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Computing

The future of whole-cell modeling is increasingly intertwined with advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). These technologies are poised to address two critical challenges in molecular simulations: force field accuracy and sampling efficiency [11]. Neural networks for predicting force field parameters have been shown to approach the accuracy of traditional quantum mechanics-based methods while being approximately three orders of magnitude more efficient [11]. Similarly, enhanced sampling methods like reinforced dynamics protocols enable more efficient exploration of complex energy landscapes, making it feasible to simulate cellular processes at relevant timescales [11].

The integration of AI methods with structural biology breakthroughs is creating new opportunities for whole-cell modeling. The availability of predicted three-dimensional models for entire proteomes through AlphaFold, combined with high-resolution structural data from cryo-electron microscopy, is rapidly filling the gaps in our structural knowledge of cellular components [11] [13]. Meanwhile, cryo-electron tomography provides unprecedented insights into cellular architecture in situ, informing more realistic model assemblies [1] [11]. These advances, coupled with the exponential growth in computational power and the emergence of MD simulation-specific supercomputers, suggest that comprehensive physical simulations of entire cells may be achievable in the foreseeable future [11].

Diagram 2: Future directions in whole-cell modeling showing the integration of artificial intelligence, structural biology advances, and advanced computing hardware.

Whole-cell modeling represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, offering a pathway to understand cellular behavior through integrated, multi-scale representations rather than isolated components. The scientific drive for this holistic view stems from the recognition that cellular functions emerge from the complex interactions between countless molecular components, and that a comprehensive understanding requires models that capture this complexity [7] [9]. While significant challenges remain in model construction, validation, and simulation, the rapid advances in experimental methods, computational power, and algorithmic approaches are quickly making whole-cell modeling a viable approach for tackling fundamental questions in biology [10] [11].

The potential applications of whole-cell models span from basic science to translational research, including drug discovery, personalized medicine, biotechnology, and beyond [8] [6]. As these models continue to develop and improve, they promise to transform how we investigate cellular processes, design therapeutic interventions, and engineer biological systems. By providing a computational framework that integrates our collective knowledge of cellular components and their interactions, whole-cell modeling offers the tantalizing possibility of predicting cellular behavior from first principles—a capability that would fundamentally advance our understanding of life and our ability to manipulate it for human benefit.

JCVI-syn3A represents a landmark achievement in synthetic biology and a transformative platform for computational modeling. This minimal cell, derived from Mycoplasma mycoides, contains a synthetically designed genome of only 543 kilobase pairs with 493 genes, making it the smallest genome of any known self-replicating organism [14] [15] [16]. Its drastically reduced complexity compared to natural bacterial cells—approximately one-tenth the genomic size of E. coli—makes it an ideal benchmark for developing and validating whole-cell computational models [17] [18]. The creation of JCVI-syn3A was driven by the fundamental question of what constitutes the minimal genetic requirements for life, providing a streamlined biological system where cellular processes can be studied without the redundancy and complexity of natural organisms [16] [19].

This minimal cell platform has emerged as a powerful testbed for computational biologists aiming to build predictive models of entire cells. Unlike traditional models that focus on isolated cellular pathways, JCVI-syn3A enables researchers to simulate integrated cellular functions from metabolism to replication within a manageable parameter space [17] [18]. With 92 genes still of unknown function in JCVI-syn3A, computational models serve not only as validation tools but also as hypothesis generators for discovering new biological mechanisms essential for life [18]. The integration of multi-scale data from genomics, proteomics, structural biology, and cryo-electron microscopy has positioned JCVI-syn3A at the forefront of efforts to simulate complete cellular systems using molecular dynamics and other computational approaches [14] [20] [21].

Genomic and Structural Characteristics

JCVI-syn3A exhibits distinctive structural and genomic properties that make it uniquely suited for whole-cell modeling. The cell measures approximately 400 nm in diameter, significantly smaller than most natural bacteria [14]. Its genome was systematically minimized through design-build-test cycles, starting from JCVI-syn1.0 (with 901 genes) and progressively removing non-essential genetic elements while maintaining capacity for autonomous replication [15] [16]. This minimization process identified both essential genes (immediately required for survival) and quasi-essential genes (necessary for robust growth but dispensable under ideal conditions) [15].

The structural organization of JCVI-syn3A, while simplified, maintains the fundamental compartments of a prokaryotic cell. The cell envelope consists of a lipid membrane without a cell wall, characteristic of Mycoplasma species [19]. Internal organization includes a nucleoid region containing the circular chromosome, ribosomes for protein synthesis, and various metabolic enzymes dispersed throughout the cytosol [20] [21]. The minimal genome has forced a high efficiency in molecular organization, with approximately 40% of the intracellular volume occupied by proteins [14]. This dense packing creates a highly crowded intracellular environment that influences molecular diffusion and interaction kinetics—a critical consideration for accurate physical modeling [14].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of JCVI-syn3A Minimal Cell

| Parameter | Specification | Significance for Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | 543 kbp | Drastically reduced sequence space for simulation |

| Number of Genes | 493 total (452 protein-coding) | Manageable number of molecular components |

| Genes of Unknown Function | 92 (20% of protein-coding genes) | Opportunity for discovery via model prediction |

| Physical Diameter | ~400 nm | Computationally tractable for 3D simulation |

| Doubling Time | 105-120 minutes | Definable cell cycle for temporal models |

| Chromosome Topology | Single circular DNA molecule | Simplified genome organization |

Metabolic Capabilities and Essential Functions

Despite its minimal genome, JCVI-syn3A maintains a surprisingly comprehensive metabolic network capable of synthesizing most essential biomolecules. The reconstructed metabolic network accounts for 98% of enzymatic reactions supported by experimental evidence or annotation [15]. Key metabolic pathways include central carbon metabolism, nucleotide biosynthesis, amino acid metabolism, and lipid biosynthesis, though the cell relies on scavenging some nutrients from its environment [15]. The model organism requires specifically enriched culture medium containing metabolic precursors that it cannot synthesize independently, reflecting the trade-offs made during genome minimization [15] [18].

The essential functions encoded by the minimal genome can be categorized into several core cellular processes: genetic information processing (DNA replication, transcription, translation), energy production, membrane biogenesis, and cellular division [18]. Analysis of gene essentiality shows that 68% of genes are strictly essential for survival, with an additional 24% classified as quasi-essential, bringing the total essentiality to 92% [15]. This high essentiality fraction underscores the efficiency of the minimized genome, with most genes serving non-redundant critical functions. The metabolic model agrees well with genome-scale in vivo transposon mutagenesis experiments, showing a Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.59 [15], validating its accuracy for predictive simulations.

Computational Modeling Approaches

Molecular Dynamics Frameworks

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of JCVI-syn3A leverage coarse-grained approaches to manage the enormous computational challenge of simulating an entire cell. The Martini force field has emerged as the primary framework for these simulations, employing a four-to-one mapping scheme where up to four heavy atoms and associated hydrogens are represented by a single coarse-grained bead [14]. This reduction decreases the number of particles in the system by approximately fourfold, speeding up simulations by about three orders of magnitude while maintaining sufficient chemical specificity [14]. For JCVI-syn3A, this approach requires about 550 million coarse-grained particles, corresponding to more than six billion atoms—a scale that would be computationally prohibitive with all-atom models [14].

The Martini ecosystem provides specialized tools for each cellular component. Martinize2 generates topologies and coordinates for proteins from atomistic structures [14]. Polyply handles nucleic acids, using a multiresolution graph-based approach to efficiently generate polymer topologies from sequence data [14]. TS2CG converts triangulated surfaces into coarse-grained membrane models, enabling simulation of the cell envelope with precise control over lipid composition and curvature [14]. These tools collectively enable construction of a comprehensive whole-cell model that integrates proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and metabolites within a unified simulation framework.

Integrative Modeling of Cellular Structures

Integrative modeling approaches combine cryo-electron tomography data with genomic and proteomic information to create accurate 3D structural models of JCVI-syn3A components. For the nucleoid, lattice-based methods generate initial models with one bead per ten base pairs, incorporating user-defined superhelical plectonemes and coarse-grain representations of nucleoid-associated proteins [20] [22]. These models are then optimized off-lattice with constraints for connectivity, steric occlusion, and fiber stiffness [20]. The resulting structures faithfully represent the genome organization while remaining computationally tractable for simulation.

The modular modeling pipeline implements "molecular masks" for key nucleoid-related complexes including RNA polymerase, ribosomes, and structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) cohesins [20]. These masks are positioned based on cryo-electron tomography data, with ribosomes placed at experimentally determined positions and other components distributed according to biochemical constraints [20]. The models successfully integrate ultrastructural information with molecular-level detail, enabling hypothesis testing about transcription, genome condensation, and spatial organization of genetic material [20].

Diagram: Integrative modeling workflow for JCVI-syn3A, showing the pipeline from experimental data to model predictions.

Application Notes: Simulation Protocols

Whole-Cell Model Construction Protocol

Objective: Construct a computationally tractable coarse-grained model of an entire JCVI-syn3A cell for molecular dynamics simulation.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Martini ecosystem tools (Vermouth, Martinize2, Polyply, TS2CG)

- Genomic sequence of JCVI-syn3A (GenBank accessions)

- Proteomic and lipidomic composition data

- Cryo-electron tomography structural data

- High-performance computing infrastructure

Procedure:

- Genome Structure Generation

- Input circular chromosome sequence (543 kbp) into Polyply software

- Generate double-stranded DNA model with 10 bp/bead resolution

- Introduce superhelical density of -0.06 to form physiological plectonemes

- Set persistence length to 50 nm for DNA mechanical properties

Proteome Integration

- Obtain atomic structures for all 452 JCVI-syn3A proteins from PDB or homology modeling

- Process each protein through Martinize2 for Martini coarse-graining

- Use Bentopy for efficient collision detection and packing of proteins within cytoplasmic volume constraints

- Incorporate functional annotations to bias spatial distribution based on biological function

Membrane Assembly

- Define membrane curvature based on cryo-ET measurements of cell morphology

- Input lipid composition (phospholipids, glycolipids) from mass spectrometry data

- Generate membrane model using TS2CG with triangulated surface representation

- Insert transmembrane proteins with characteristic lipid shells using lipid fingerprint data

System Integration and Equilibration

- Combine all components in simulation box with appropriate ionic conditions

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm

- Conduct stepwise equilibration with position restraints gradually released

- Run production molecular dynamics simulation using GROMACS with Martini parameters

Validation Metrics:

- Compare simulated cell diameter to experimental measurements (~400 nm)

- Verify reproduction of experimental doubling time (105-120 minutes)

- Confirm appropriate density of cytoplasmic proteins (~40% volume fraction)

- Validate structural stability over multiple replication cycles

Nucleoid Modeling Protocol

Objective: Generate a 3D structural model of the JCVI-syn3A nucleoid integrating experimental data and molecular details.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- ModularLattice software package

- Cryo-ET segmented ribosome positions

- Genomic sequence with gene annotations

- Structures of RNA polymerase, ribosomes, SMC complexes

Procedure:

- Molecular Mask Preparation

- Generate lattice-based models of RNA polymerase (PDB 6c6u), ribosomes (PDB 4v6k), and SMC cohesins (PDB 7nyx)

- Embed each molecular structure in a 3.4 nm grid, selecting points within one grid spacing of atoms

- Manually assign control points for DNA/RNA/protein chain connections

- Add insulating points around control points to prevent occlusion

Component Placement

- Import experimentally determined ribosome positions (503 total)

- Place ribosome masks with random orientations from 24 possible 90° rotations

- Resolve minor clashes through local jittering of positions

- Place RNA polymerases (187 total) via random walk algorithm in free spaces

- Position SMC complexes (187 total) between polymerase locations

Genome Tracing and Connectivity

- Connect molecular masks with DNA segments using biased random walk

- Implement user-defined supercoiling for DNA segments

- Connect RNA polymerases to ribosomes via mRNA chains

- Ensure single circular DNA continuity throughout nucleoid

Structural Refinement

- Optimize model off-lattice with connectivity constraints

- Apply steric exclusion constraints between all components

- Enforce appropriate fiber stiffness for DNA and RNA chains

- Perform Monte Carlo relaxation to eliminate residual clashes

Validation:

- Verify genome occupies appropriate nucleoid volume fraction

- Confirm compatibility with Hi-C contact probability data

- Check appropriate spatial segregation of transcription and translation

- Validate mechanical properties against single-molecule experiments

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters for JCVI-syn3A Simulations

| Simulation Parameter | Value | Computational Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse-Grained Particles | ~550 million | Enables millisecond timescales on exascale computing |

| Simulation Box Size | ~500 nm³ | Requires massive parallelization across GPU clusters |

| Temporal Resolution | 20-50 fs | Balances numerical stability with simulation speed |

| Simulation Duration | 1-10 μs | Captures complete cell division cycles |

| Energy Calculations | ~2000 reactions | Tracks metabolic flux and energy budgets |

Research Reagent Solutions

The computational study of JCVI-syn3A relies on both in silico tools and physical research reagents that enable model validation. The table below details essential resources for JCVI-syn3A research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for JCVI-syn3A Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martini Force Field | Computational Tool | Coarse-grained molecular dynamics parameters | Martini Database (https://mdmartini.nl) |

| Polyply | Software | Graph-based generation of nucleic acid structures | GitHub Repository (https://github.com/marrink-lab/polyply) |

| JCVI-syn3A Genome | Biological Data | Minimal genome sequence | GenBank CP014940.1 |

| ModularLattice | Software | Lattice-based nucleoid modeling | GitHub (https://github.com/ccsb-scripps/ModularNucleoid) |

| Cryo-ET Tomograms | Experimental Data | Cellular ultrastructure reference | Available upon collaboration |

| Metabolic Network Model | Computational Model | Constraint-based metabolic flux analysis | Supplementary materials from [15] |

Signaling and Metabolic Pathways

JCVI-syn3A contains streamlined versions of essential metabolic pathways that represent core energy production and biosynthetic capabilities. The major metabolic routes include glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, nucleotide biosynthesis, and limited amino acid metabolism [15] [18]. The metabolic model successfully predicts flux distributions that match experimental measurements of nutrient consumption and growth rates, providing validation of its accuracy [15].

A key feature of JCVI-syn3A's metabolism is its heavy reliance on substrate-level phosphorylation for energy generation rather than oxidative phosphorylation [15]. This simplification reflects the minimal genome's elimination of many electron transport chain components, resulting in exclusively fermentative metabolism. The model predicts and experiments confirm that addition of specific non-essential genes can enhance metabolic efficiency, such as the 13% reduction in doubling time observed when pyruvate dehydrogenase genes were added back to the minimal genome [18].

Diagram: Core metabolic network of JCVI-syn3A showing simplified metabolic pathways and their connections to cellular functions.

JCVI-syn3A has established a new benchmark for whole-cell modeling, demonstrating that predictive simulation of an entire living organism is computationally achievable when biological complexity is sufficiently minimized. The integration of multi-scale data from cryo-electron tomography, proteomics, and metabolomics with molecular dynamics frameworks has produced models that accurately recapitulate observed cellular behaviors, including growth rates and structural organization [14] [18]. These models serve not only as validation tools but as discovery platforms, generating testable hypotheses about the function of uncharacterized essential genes and enabling in silico experiments that would be resource-intensive to perform in the laboratory [17] [18].

Future developments in JCVI-syn3A modeling will focus on increasing spatial and temporal resolution while expanding the scope of cellular processes represented. Current efforts aim to integrate stochastic gene expression with metabolic flux models to predict phenotypic variability in clonal populations [18]. As computational power increases through exascale computing, all-atom simulations of subcellular compartments may become feasible, providing atomic-level insights into molecular mechanisms within the context of the full cellular environment [14]. The JCVI-syn3A platform continues to evolve as a testbed for developing computational methods that will eventually be applied to more complex model organisms and human cells, advancing toward the ultimate goal of predictive whole-cell modeling for biomedical and biotechnological applications [17].

Spatial Resolution, Timescales, and the 'Computational Microscope'

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has matured into a powerful tool that functions as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to probe biomolecular processes at an atomic level of detail that is often difficult or impossible to achieve with experimental techniques alone [14] [23]. This "microscope" provides an exceptional spatio-temporal resolution, revealing the dynamics of cellular components and their interactions [24]. The application of this technology to model an entire cell represents a monumental step forward in computational biology, offering the potential to interrogate a cell's spatio-temporal evolution in unprecedented detail [14] [1]. This article details the key concepts, quantitative parameters, and experimental protocols for employing MD simulations to study biological systems at the scale of a complete minimal cell.

Key Quantitative Parameters

The utility of the computational microscope is defined by its ability to resolve specific spatial and temporal characteristics. The following parameters are critical for planning and interpreting simulations, especially for large-scale systems like an entire cell.

Table 1: Key Spatio-Temporal Parameters in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Parameter | Typical Range | Description | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic (Ã…) to Coarse-Grained (nm) | Level of structural detail captured. | From atomic interactions (all-atom) to macromolecular assembly dynamics (coarse-grained). |

| Temporal Resolution | 0.5 - 2.0 femtoseconds (fs) | Time interval between simulation steps [25]. | Determines the fastest motions that can be accurately captured (e.g., bond vibrations). |

| Total Simulation Time | Nanoseconds (ns) to Milliseconds (ms) | Total physical time covered by the simulation [24]. | Determines which biological processes can be observed (e.g., local dynamics vs. protein folding). |

| System Size (All-Atom) | Millions to Billions of atoms | Number of atoms in the simulation box. | From single proteins to sub-cellular structures or minimal cells (e.g., ~6 billion atoms for JCVI-syn3A) [14]. |

| System Size (Coarse-Grained) | Hundreds of Millions of particles | Reduced number of interaction sites, speeding up calculations. | Enables simulation of mesoscale systems like entire cells (e.g., ~550 million particles for JCVI-syn3A) [14]. |

Workflow for Whole-Cell Modeling and Simulation

Constructing and simulating an entire cell requires an integrative modeling approach that synthesizes diverse experimental data into a coherent computational framework [14] [1]. The workflow involves multiple stages, from data collection to final analysis.

Diagram Title: Integrative Workflow for Whole-Cell MD Simulation

The Martini Ecosystem: A Toolkit for Mesoscale Simulation

For modeling systems as vast as an entire cell, a coarse-grained (CG) approach is indispensable. The Martini force field is a leading CG model that employs a four-to-one mapping scheme, where up to four heavy atoms are represented by a single CG bead [14]. This reduction, combined with a smoothened potential energy surface, accelerates simulations by approximately three orders of magnitude, making cellular-scale modeling feasible [14]. The Martini "ecosystem" comprises a suite of software tools designed to work together.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Whole-Cell MD

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Whole-Cell MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martini Force Field | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Defines interaction parameters for biomolecules [14]. | Provides the physical model for efficient simulation of large, complex cellular systems. |

| Martinize2 | Software Tool | High-throughput generation of Martini topologies for proteins [14]. | Automates the conversion of the proteome (hundreds of proteins) into CG representations. |

| Polyply | Software Tool | Generates topologies and coordinates for polymeric systems like DNA [14]. | Constructs large chromosomal DNA structures from sequence data. |

| Bentopy | Software Tool (In Dev) | Efficiently packs proteins and complexes into dense solutions [14]. | Assembles the crowded cytoplasmic environment based on functional annotations and abundances. |

| TS2CG | Software Tool | Converts triangulated surfaces into CG membrane models [14]. | Builds complex cell envelopes with curvature-dependent lipid composition. |

| Vermouth | Python Library | Graph-based framework unifying Martini processes [14]. | Serves as the central, interoperable foundation for many ecosystem tools. |

| GROMACS | MD Simulation Engine | High-performance software to run MD simulations [26]. | Executes the production MD simulation, often optimized for GPUs. |

| Calcium plumbate | Calcium Plumbate Supplier | 12013-69-3 | For Research | High-purity Calcium Plumbate (Ca2O4Pb) for materials science and corrosion research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| FMePPEP | FMePPEP, CAS:1059188-86-1, MF:C26H24F4N2O2, MW:472.47 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application Note: Modeling the JCVI-syn3A Minimal Cell

Background and Rationale

The minimal cell JCVI-syn3A (Syn3A), created by the J. Craig Venter Institute, is an ideal candidate for whole-cell modeling [14] [1]. With a diameter of only 400 nm and a stripped-down genome of 493 genes, its relative simplicity makes the immense challenge of a full-cell simulation tractable [14]. Its composition has been extensively characterized, providing the necessary quantitative data for integrative modeling [1].

Detailed Protocol for Constructing the Syn3A Model

Step 1: Chromosome Building

- Input: The circular chromosome sequence of 543 kbp.

- Tool: Polyply.

- Method: Use the graph-based and biased random walk protocols within Polyply to generate the three-dimensional structure and Martini topology of the chromosomal DNA directly from its sequence. This avoids the computational intractability of forward-mapping from an all-atom structure [14].

- Output: A coarse-grained model of the entire circular chromosome.

Step 2: Cytoplasmic Packing

- Input: The proteome of Syn3A, including the identity, structure, and abundance of all proteins.

- Tool: Martinize2 for protein topology generation; Bentopy for spatial packing.

- Method:

- Process all protein structures through Martinize2 to generate their CG representations.

- Use Bentopy to perform collision-detection-based packing of all cytoplasmic components, including proteins, ribosomes, and metabolites, into the defined cytosolic volume. The packing can be biased using functional annotations to create a biologically realistic distribution [14].

- Output: A densely packed, crowded cytoplasm model.

Step 3: Cell Envelope Assembly

- Input: Lipid composition data for the cell membrane.

- Tool: TS2CG.

- Method:

- Define a triangulated surface representing the cell membrane.

- Use TS2CG's backmapping algorithm to populate the membrane with lipids according to the specified composition. The tool allows precise control over the lipid distribution in both membrane leaflets [14].

- Insert membrane proteins with their characteristic lipid shells (lipid fingerprints).

- Output: A complete, protein-studded model of the cell membrane.

Step 4: System Integration and Simulation

- Input: The assembled components (chromosome, cytoplasm, membrane).

- Tool: A molecular dynamics engine like GROMACS.

- Method:

- Combine all components into a single simulation system.

- Solvate the system with the appropriate CG water model.

- Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological salt concentration.

- Energy-minimize the system to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibrate the system with positional restraints on non-solvent components, then gradually release restraints.

- Run the production simulation. For Syn3A, this involves propagating ~550 million CG particles, a task requiring massive parallelization on high-performance computing (HPC) systems, often leveraging GPUs [14].

Visualization of the Martini Ecosystem

The following diagram illustrates how the various tools in the Martini ecosystem interact to build a complete cell model.

Diagram Title: Software Architecture of the Martini Ecosystem

Analysis of Simulation Trajectories

The raw output of an MD simulation is a trajectory file containing the time-evolving coordinates of all particles. Extracting scientific insight requires sophisticated analysis.

Essential Analysis Techniques

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Measures the deviation of a particle (e.g., a protein's Cα atom) from its average position, quantifying flexibility and thermal fluctuations [27].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies the dominant collective motions (essential dynamics) in a system by diagonalizing the covariance matrix of atomic displacements. This reduces the high-dimensional trajectory data to a few key modes that often correlate with biological function [25].

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): Quantifies the short-range order in a system, such as the solvation shell around an ion or the packing of molecules in the cytoplasm [25].

- Mean Square Displacement (MSD) & Diffusion Coefficient: The MSD measures the average squared distance a particle travels over time. In the diffusive regime, the slope of the MSD vs. time plot is used to calculate the diffusion coefficient (D), providing a quantitative measure of molecular mobility within the crowded cellular environment [25].

Statistical Significance in MD

A critical consideration when analyzing MD trajectories is the sampling problem. Due to the high dimensionality of conformational space, independent simulations started from slightly different conditions can yield different results [28] [27]. Therefore, it is essential to perform multiple replicate simulations and employ statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests) to determine whether observed differences (e.g., between wild-type and mutant proteins) are statistically significant and not merely artifacts of incomplete sampling [28] [27].

The ambitious goal of building a virtual cell—a computational model capable of accurately simulating cellular behaviors in silico—represents a frontier in computational biology with the potential to revolutionize biomedical research and drug discovery [29]. Current state-of-the-art cellular simulations operate across multiple spatial and temporal scales, employing diverse computational strategies. These range from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that model cellular components at near-atomic resolution to generative AI models that predict morphological changes in response to perturbations, and agent-based models that simulate multi-cellular systems [29] [1] [30]. Driving these advances are increases in computational power, the development of sophisticated machine learning algorithms, and the generation of massive, high-quality datasets through automated high-content screening [29] [31]. This article details the key methodologies, applications, and protocols underpinning the latest breakthroughs in cellular simulation, framed within the context of a broader thesis on molecular dynamics simulation of entire cells.

State-of-the-Art Simulation Paradigms

Whole-Cell Molecular Dynamics at Coarse-Grained Resolution

Objective: To construct a dynamic, molecular-scale model of an entire cell, capturing the spatio-temporal interactions of all its components.

Rationale: While traditional MD simulations provide unparalleled detail, their computational cost has historically limited their application to cellular subsystems. The use of coarse-grained (CG) force fields like Martini, which reduces system complexity by representing groups of atoms as single interaction beads, has enabled a leap in simulation scale [1] [14]. This approach has been successfully applied to create integrative models of a minimal cell, JCVI-syn3A, which contains only 493 genes and is one of the simplest self-replicating organisms known [1] [14].

- Proof of Concept: A proof-of-concept model of the JCVI-syn3A cell requires approximately 550 million CG particles, corresponding to more than six billion atoms, showcasing the immense scale now achievable [14].

- The Martini Ecosystem: Building and simulating an entire cell relies on a suite of integrated software tools [1] [14]:

- Vermouth: A central framework for unified handling of Martini topologies and coordinate generation.

- Martinize2: High-throughput generation of Martini topologies for proteins from atomistic structures.

- Polyply: Efficient generation of topologies and initial coordinates for large polymeric systems like chromosomal DNA.

- TS2CG: Converts triangulated surfaces into CG membrane models with precise lipid composition.

- Bentopy: Generates dense, crowded protein solutions representative of the cellular interior.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics in State-of-the-Art Cellular Simulations

| Simulation Type | System Scale | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value / Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Cell MD (Coarse-Grained) | JCVI-syn3A Minimal Cell | Number of CG Particles / Atoms Represented | ~550 million particles (>6 billion atoms) [1] [14] |

| Cellular Morphology Prediction (CellFlux) | Chemical & Genetic Perturbation Datasets (BBBC021, RxRx1, JUMP) | Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) Improvement | 35% improvement over previous methods [29] |

| Mode-of-Action Prediction Accuracy | 12% increase in accuracy [29] | ||

| Multi-Cellular Simulation (CellSys) | Tumor Spheroids & Monolayers | Maximum Simulated Cell Count | Up to several million cells [30] |

Generative AI for Predicting Cellular Morphology

Objective: To simulate how cellular morphology changes in response to chemical and genetic perturbations by learning a distribution-to-distribution mapping.

Rationale: Traditional microscopy is destructive, preventing direct observation of the same cell before and after a perturbation. CellFlux, a state-of-the-art model, overcomes this by using flow matching to learn the transformation from a distribution of unperturbed (control) cell images to a distribution of perturbed cell images [29]. This approach inherently corrects for experimental artifacts like batch effects and enables continuous interpolation between cellular states.

- Input and Output: The model takes as input an unperturbed cell image and a specified perturbation (e.g., a drug or genetic modification). It outputs a predicted image of the cell after the perturbation, faithfully capturing morphology changes specific to that intervention [29].

- Performance: Evaluated on major chemical (BBBC021), genetic (RxRx1), and combined perturbation (JUMP) datasets, CellFlux generates high-fidelity images that improve upon existing methods, as measured by a 35% improvement in FID scores and a 12% increase in mode-of-action prediction accuracy [29].

Agent-Based Modeling of Multi-Cellular Systems

Objective: To simulate growth and organization processes in multi-cellular systems, such as avascular tumor spheroids and regenerating tissues.

Rationale: Understanding tissue-level phenomena requires modeling cells as discrete, interacting agents. Software like CellSys implements an off-lattice, agent-based model where each cell is represented as an isotropic, elastic, and adhesive sphere [30].

- Biophysical Foundation: Cell migration is governed by a Langevin equation of motion, and cell-cell interactions are modeled using the experimentally validated Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) model, which summarizes deformation, compression, and adhesion forces [30].

- Applications: This methodology has been used to model liver regeneration after toxic damage, leading to predictions of cell alignment mechanisms along microvessels that were subsequently validated experimentally [30].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Application Note: Simulating Perturbation Responses with CellFlux

1. Purpose To provide a protocol for using the CellFlux model to simulate the morphological changes in cells induced by a specific chemical or genetic perturbation.

2. Background CellFlux employs flow matching, a generative technique that uses an ordinary differential equation (ODE) to continuously transform the distribution of control cell images into the distribution of perturbed cell images. This allows for the in silico prediction of perturbation effects, correcting for batch artifacts and enabling the exploration of intermediate cellular states through interpolation [29].

3. Materials and Data Requirements

- Software: CellFlux codebase (publicly available).

- Data: A dataset containing paired sets of control and perturbed cell images from the same experimental batch. Standard datasets include BBBC021 (chemical), RxRx1 (genetic), or JUMP (combined).

- Input Specifications: Multi-channel microscopy images (e.g., H × W × C) from high-content screening, such as cell painting assays [29].

4. Step-by-Step Protocol

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing. Prepare and normalize the microscopy images. Ensure control and perturbed image sets are correctly assigned and batched.

- Step 2: Model Loading. Load the pre-trained CellFlux model, which includes the learned neural network approximating the velocity field for the distribution transformation.

- Step 3: Conditioning. For a given simulation, input a control cell image (

x0) and the desired perturbation condition (c). - Step 4: Sampling. Sample from the conditional distribution

p(x1|x0, c)by solving the ODE defined by the flow matching model. This generates a new, synthetic image of the perturbed cell (x1). - Step 5: Analysis. Use the generated images for downstream tasks such as mode-of-action classification, phenotypic analysis, or visualizing state transitions via interpolation.

5. Troubleshooting

- Poor Generation Fidelity: Ensure control and perturbed data are from the same experimental batch to minimize uncorrected artifacts.

- Computational Load: Leverage GPU acceleration for faster ODE solving during image sampling.

Application Note: Building a Coarse-Grained Whole-Cell Model

1. Purpose To outline the integrative modeling workflow for constructing a starting model of a minimal cell (JCVI-syn3A) for molecular dynamics simulation using the Martini coarse-grained force field.

2. Background This protocol integrates experimental data from cryo-electron tomography (CryoET), -omics experiments, and known structures to build a spatially detailed, molecular-resolution model of an entire cell. The Martini force field's four-to-one mapping scheme speeds up simulations by about three orders of magnitude, making cell-scale simulations feasible [1] [14].

3. Materials and Reagents (In Silico)

- Software: The Martini ecosystem (Vermouth, Martinize2, Polyply, TS2CG, Bentopy), MD simulation package (e.g., GROMACS).

- Data: Genome sequence; proteome list; lipidome composition; cryo-ET data for structural constraints.

4. Step-by-Step Protocol

- Step 1: Chromosome Building. Use Polyply to generate the topology and initial coordinates of the circular chromosomal DNA from the genome sequence using a graph-based, biased random walk protocol [1] [14].

- Step 2: Cytoplasm Modeling. Use Martinize2 for high-throughput generation of Martini topologies for all proteins in the proteome. Use Bentopy to pack these proteins and other soluble components (e.g., metabolites, ribosomes) into a dense, crowded solution within the cell volume, respecting volumetric constraints [1].

- Step 3: Cell Envelope Assembly. Use TS2CG to build the cell membrane. The tool converts a triangulated surface representing the cell geometry into a CG membrane model, allowing for precise determination of curvature-dependent lipid concentrations in both membrane leaflets. Insert membrane proteins along with their characteristic lipid shells [14].

- Step 4: System Integration and Equilibration. Combine the chromosome, cytoplasm, and membrane components into a unified simulation system. Run initial energy minimization and short equilibration simulations to relax steric clashes.

5. Troubleshooting

- System Instability: Carefully check the topologies of all components, particularly custom metabolites or lipids. Ensure charge neutrality of the system by adding appropriate counterions.

- Memory Limitations: The construction of the initial system is memory-intensive and may require access to high-performance computing (HPC) resources.

The following diagram illustrates the integrative modeling workflow for building a whole-cell model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cellular Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specifications & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Martini Coarse-Grained Force Field | Provides the interaction parameters for simulating biomolecules at a reduced resolution, enabling larger spatial and temporal scales. | Includes parameters for proteins, lipids, polynucleotides, carbohydrates, and metabolites [1] [14]. |

| GROMACS MD Suite | A high-performance software package for performing molecular dynamics simulations; widely used for both atomistic and coarse-grained simulations. | Supports the Martini force field; highly optimized for parallel computing on CPUs and GPUs [32]. |

| Cell Painting Assay Kits | High-content screening assay that uses fluorescent dyes to label multiple cellular components, generating rich morphological data for training models like CellFlux. | Labels nucleus, cytoskeleton, Golgi, etc. [29]. |

| IMOD / ImageJ Software | Software packages for processing, visualizing, and segmenting 3D electron microscopy data, a key step in creating realistic cellular geometries for simulation. | Used for tomographic reconstruction and manual/automatic segmentation of cellular structures [31]. |

| DeepCell / CellSegmenter AI Tools | Machine learning-based tools for the automatic segmentation of cells and subcellular structures from microscopy images. | Platforms like DeepCell and the Allen Cell Structure Segmenter use convolutional neural networks (e.g., U-Net) for accurate segmentation [31]. |

| Lyngbyatoxin-d8 | Lyngbyatoxin-d8, MF:C₂₇H₃₁D₈N₃O₂, MW:445.66 | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Bromo Lidocaine-d5 | 3-Bromo Lidocaine-d5, MF:C₁₄H₁₆D₅BrN₂O, MW:318.26 | Chemical Reagent |

Critical Data Visualization and Workflow Analysis

Effective visualization is paramount for analyzing the massive datasets produced by modern cellular simulations. The shift from static, frame-by-frame visualization to interactive, web-based tools and immersive virtual reality (VR) environments allows researchers to intuitively explore complex structural and dynamic data [33]. Furthermore, deep learning techniques are being used to embed high-dimensional simulation data into lower-dimensional latent spaces, which can then be visualized to reveal patterns and relationships that are difficult to discern in the raw data [33] [31].

The following diagram outlines the end-to-end workflow for transitioning from experimental data to physics-based simulation in a realistic cellular geometry, highlighting key decision points and potential integration of machine learning.

Building and Simulating a Digital Cell: Methodologies and Real-World Applications