A Comprehensive Guide to Whole-Genome Sequencing Pipelines for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

The rapid proliferation of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a critical global health threat, necessitating advanced genomic surveillance tools.

A Comprehensive Guide to Whole-Genome Sequencing Pipelines for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

Abstract

The rapid proliferation of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a critical global health threat, necessitating advanced genomic surveillance tools. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing whole-genome sequencing (WGS) pipelines specifically optimized for antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) identification. We explore foundational concepts of AMR mechanisms and sequencing technologies, detail step-by-step methodological workflows from sample preparation to variant calling, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and provide frameworks for analytical validation and comparative performance assessment of bioinformatics tools. By integrating the latest advancements in sequencing platforms, computational tools, and database resources, this guide aims to equip scientists with practical knowledge to enhance AMR detection, surveillance, and mitigation strategies in both research and clinical settings.

Understanding AMR Mechanisms and Sequencing Foundations for Resistance Gene Discovery

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most severe global public health threats of the modern era, undermining the efficacy of existing treatments and threatening decades of medical progress. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that bacterial AMR was directly responsible for 1.27 million global deaths in 2019 and contributed to 4.95 million deaths [1]. In the United States alone, more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year, resulting in over 35,000 deaths [2]. The economic costs are equally staggering, with the World Bank estimating that AMR could result in US$ 1 trillion additional healthcare costs by 2050, and US$ 1 trillion to US$ 3.4 trillion gross domestic product (GDP) losses per year by 2030 [1].

This application note examines the global AMR crisis through the lens of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) pipelines for resistance gene identification. We provide researchers and drug development professionals with current epidemiological data, detailed experimental methodologies, and technical frameworks for AMR surveillance and research, contextualized within a broader thesis on genomic identification of resistance mechanisms.

Global Prevalence and Regional Variation of AMR

Current Global Resistance Patterns

According to the 2025 WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) report, approximately one in six laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections worldwide in 2023 were resistant to antibiotic treatments. Between 2018 and 2023, antibiotic resistance rose in over 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations monitored, with an average annual increase of 5–15% [3].

The WHO report analyzed eight common bacterial pathogens across human infections: Acinetobacter spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, non-typhoidal Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. These pathogens are linked to infections of the urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, bloodstream, and urogenital gonorrhoea [3].

Table 1: Global Antibiotic Resistance Prevalence by WHO Region (2023)

| WHO Region | Resistance Prevalence | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| South-East Asia | 1 in 3 infections (33%) | Highest regional resistance rates |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 1 in 3 infections (33%) | Comparable to South-East Asia |

| African Region | 1 in 5 infections (20%) | Moderate but concerning prevalence |

| Global Average | 1 in 6 infections (16.7%) | Aggregate across all regions |

Pathogen-Specific Resistance Profiles

Gram-negative bacterial pathogens pose particularly severe threats due to their resistance mechanisms and potential for rapid spread. The WHO identifies several critical resistance patterns of concern [3]:

- E. coli and K. pneumoniae: More than 40% of E. coli and over 55% of K. pneumoniae globally are now resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, the first-line treatment for these infections. In the African Region, this resistance exceeds 70% [3].

- Carbapenem resistance: Once rare, carbapenem resistance is becoming increasingly frequent, narrowing treatment options and forcing reliance on last-resort antibiotics. This is particularly problematic for E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella, and Acinetobacter [3].

- MRSA: The 2022 GLASS report highlighted a 35% median rate for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus across 76 reporting countries [1].

Table 2: Key Pathogen-Specific Resistance Rates

| Pathogen | Antibiotic Class | Resistance Rate | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Third-generation cephalosporins | >40% globally | First-line treatment failure for UTIs, bloodstream infections |

| K. pneumoniae | Third-generation cephalosporins | >55% globally | Treatment failure in severe infections; higher mortality |

| E. coli | Fluoroquinolones | 1 in 5 UTIs (20%) | Reduced efficacy for common infections |

| S. aureus | Methicillin (MRSA) | 35% (median across 76 countries) | Complicated skin, soft tissue, and bloodstream infections |

Impact on Public Health and Clinical Practice

Direct Health Consequences

AMR threatens fundamental components of modern medicine, making routine medical procedures significantly riskier. The ability to perform surgeries, caesarean sections, cancer chemotherapy, and organ transplants relies on effective antibiotics to prevent and treat potential infections [1]. As resistance grows, these life-saving procedures become increasingly dangerous.

The burden of AMR is not distributed equally. Drivers and consequences of AMR are exacerbated by poverty and inequality, with low- and middle-income countries most affected [1]. Regions with limited healthcare infrastructure face compounded challenges from AMR, including reduced capacity for diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance.

Economic Impact

Beyond direct health consequences, AMR imposes substantial economic costs at both national and institutional levels:

- Healthcare costs: The World Bank estimates US$ 1 trillion in additional healthcare costs by 2050 directly attributable to AMR [1].

- Productivity losses: Gross domestic product losses of US$ 1 trillion to US$ 3.4 trillion per year are projected by 2030 [1].

- Treatment expenses: In the U.S. alone, treatment costs for six common antimicrobial-resistant infections exceed $4.6 billion annually [2].

WGS Pipelines for AMR Gene Identification: Experimental Protocols

Whole-genome sequencing has revolutionized AMR surveillance by enabling comprehensive characterization of resistance mechanisms. Two primary methodological approaches have emerged: read-based methods (alignment of raw sequencing reads to reference databases) and assembly-based methods (de novo assembly of genomes prior to analysis) [4]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations for AMR gene identification.

Table 3: Comparison of WGS Approaches for AMR Detection

| Method Type | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read-Based | Faster processing; Less computationally demanding; Suitable for rapid screening | Potential false positives from spurious mapping; Genomic context generally missed | Outbreak investigations; Rapid clinical screening |

| Assembly-Based | Detects novel ARGs with low similarity; Captures genomic context and regulatory elements; Identifies mobile genetic elements | Computationally expensive; Time-consuming due to assembly step | Comprehensive resistome analysis; Research studies; Discovery of novel mechanisms |

Protocol 1: Rapid Nanopore Sequencing for AMR Detection

A recent study evaluated a rapid nanopore-based protocol (ONT20h) for detecting AMR genes, virulence factors, and mobile genetic elements in MRSA and ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae [5]. This protocol demonstrates comparable or superior performance to traditional sequencing methods while offering significantly faster turnaround times.

Materials and Equipment:

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) GridION sequencer

- Rapid barcoding kit (SQK-RBK004)

- R9.4.1 flow cells

- Computational resources for bioinformatics analysis

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: High-quality genomic DNA extraction from bacterial isolates using standardized protocols.

- Library Preparation: Employ the rapid barcoding kit (SQK-RBK004) following manufacturer specifications.

- Sequencing: Load samples onto ONT GridION sequencer with R9.4.1 flow cells.

- Sequencing Duration: Run sequencing for 20 hours (ONT20h protocol).

- Genome Assembly: Perform de novo assembly using Flye v.2.7.1.

- Polish Assemblies: Conduct two rounds of polishing using Medaka v.1.0.1.

- AMR Gene Identification: Analyze polished assemblies using ResFinder and CARD-RGI with default settings.

Performance Characteristics:

- The ONT20h protocol demonstrated comparable or superior performance in AMR gene detection relative to slower sequencing protocols [5].

- Showed high concordance with phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

- Enabled detection of virulence factors and mobile genetic elements crucial for understanding pathogenicity and AMR dissemination.

Protocol 2: The "Align-Search-Infer" Pipeline for Klebsiella pneumoniae

A 2025 study developed a specialized pipeline for rapid inference of antimicrobial susceptibility in K. pneumoniae, a WHO priority pathogen [6]. This method utilizes a customized whole-genome database for rapid phenotype prediction.

Materials and Equipment:

- Oxford Nanopore MinION Mk1B

- Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK110-96)

- R9.4.1/FLO-MIN106 flow cells

- Custom curated database of K. pneumoniae genomes

- High-performance computing resources

Methodology:

- Sequencing: Perform WGS using Oxford Nanopore MinION with Rapid Barcoding Kit.

- Basecalling: Execute with Guppy basecaller v6.1.7 Super High Accuracy mode (quality threshold ≥10).

- Read Processing: Filter and trim reads using NanoFilt v2.8.0 (200 bp filtering threshold, 15 bp trimming threshold).

- Database Construction: Create a local curated database from assembled whole genomes of 40 K. pneumoniae isolates.

- Alignment and Inference:

- Align: Query reads against the whole genome database

- Search: Identify best-matched genome in the database

- Infer: Assign the antimicrobial susceptibility phenotype of the query based on the best match

Performance Characteristics:

- Achieved 77.3% accuracy for carbapenem resistance inference within 10 minutes using whole-genome matching.

- Attained 85.7% accuracy within 1 hour using plasmid matching.

- Surpassed the 54.2% accuracy of traditional AMR gene detection at 6 hours.

- Required less bacterial DNA (50-500 kilobases vs. 5,000 kilobases for gene detection) [6].

Protocol 3: Comprehensive Resistome Analysis with sraX

The sraX pipeline provides a fully automated analytical tool for performing precise resistome analysis across hundreds of bacterial genomes in parallel [7]. This tool integrates multiple unique features for comprehensive AMR determinant detection.

Materials and Equipment:

- Perl v5.26.x with complementary libraries (LWP::Simple, Data::Dumper, JSON, File::Slurp, FindBin, Cwd)

- DIAMOND dblastx v0.9.29

- NCBI blastx/blastn v2.10.0

- MUSCLE v3 for multiple-sequence alignment

- Reference databases: CARD, ARGminer, BacMet

Methodology:

- Database Setup: Compile local AMR database by gathering sequence data from CARD, ARGminer, and BacMet.

- Analysis Execution: Run single-command sraX analysis on genomic datasets.

- Resistance Detection:

- Conduct homology searches against curated AMR databases

- Validate known polymorphic positions conferring resistance

- Perform genomic context analysis of identified ARGs

- Output Generation: Produce comprehensive HTML-formatted report including:

- Heat-maps of gene presence and sequence identity

- Proportion of drug classes resistance

- Type of mutated loci

- Spatial distribution of detected ARGs per genome

Unique Features:

- Genomic context analysis: Visualizes arrangement of adjacent genes and regulatory elements.

- SNP validation: Identifies known mutations conferring resistance and detects putative new variants.

- Integrated visualization: Generates comprehensive graphical outputs within a navigable HTML report.

- Single-command operation: Accessible to users without extensive bioinformatics expertise [7].

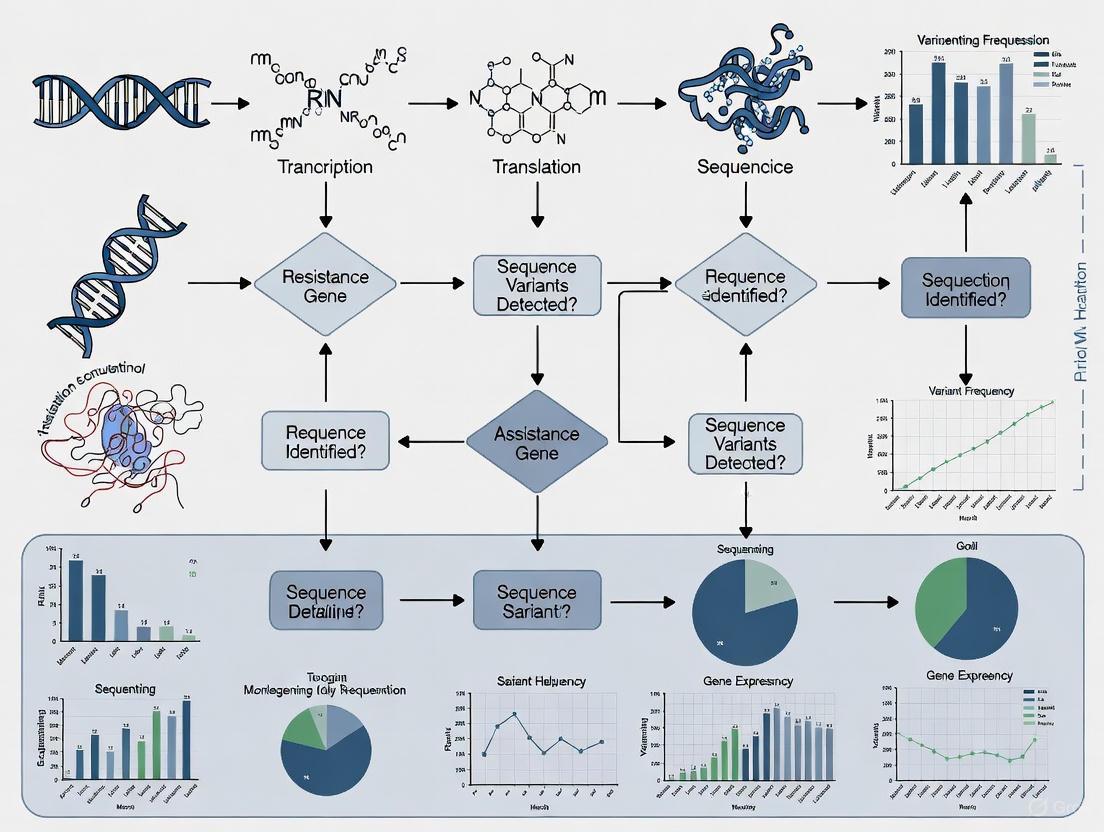

WGS Pipeline Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for whole-genome sequencing-based identification of antibiotic resistance genes, integrating elements from multiple protocols described in this document:

WGS Pipeline for Antibiotic Resistance Gene Identification

Research Reagent Solutions for AMR Detection

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AMR Genomics

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Oxford Nanopore GridION | Long-read sequencing; Real-time data generation | Rapid AMR detection; Field applications |

| Illumina MiSeq | Short-read sequencing; High accuracy | Reference-quality genomes; Validation studies | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CARD-RGI (Resistance Gene Identifier) | Predicts resistomes from protein/nucleotide data | Comprehensive AMR gene detection [8] |

| ResFinder/PointFinder | Identifies acquired AMR genes and chromosomal mutations | Pathogen-specific resistance profiling [4] | |

| sraX | Automated resistome analysis pipeline | Parallel processing of hundreds of genomes [7] | |

| AMRFinderPlus | Detects resistance genes, point mutations, and variants | Integrated analysis of diverse AMR mechanisms [4] | |

| Reference Databases | CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) | Curated repository of ARGs with ontology framework | Gold-standard for AMR gene annotation [4] |

| ResFinder | Specialized database for acquired AMR genes | Detection of horizontally transferred resistance [4] | |

| ARGminer | Aggregates data from multiple AMR repositories | Expanded coverage of resistance determinants [7] | |

| Laboratory Kits | ONT Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK004) | Rapid library preparation for nanopore sequencing | Time-sensitive AMR profiling [5] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The escalating global AMR crisis demands sophisticated surveillance and research methodologies. Whole-genome sequencing pipelines offer powerful approaches for identifying resistance mechanisms, tracking transmission, and informing clinical decisions. The protocols and resources detailed in this application note provide researchers and drug development professionals with cutting-edge methodologies to address this public health emergency.

Future directions in AMR research include:

- Integration of machine learning for prediction of novel resistance mechanisms from genomic data [4]

- Development of point-of-care sequencing solutions for rapid clinical decision-making

- Expansion of global surveillance networks to improve data sharing and resistance tracking

- Standardization of bioinformatics protocols across laboratories and platforms

The WHO calls on all countries to report high-quality data on AMR and antimicrobial use to GLASS by 2030 [3]. Achieving this target will require concerted action to strengthen laboratory systems, enhance data quality and geographic coverage, and implement coordinated interventions across human health, animal health, and environmental sectors using a One Health approach.

As the field of AMR genomics continues to evolve, the tools and methodologies outlined in this application note will play an increasingly vital role in mitigating the global impact of antimicrobial resistance and preserving the efficacy of existing treatments for future generations.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a critical threat to global health, undermining the efficacy of life-saving treatments and increasing the risk associated with common infections and routine medical interventions [9] [10]. The rapid proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) threatens to reverse decades of medical progress, with bacterial AMR directly contributing to an estimated 1.14 million deaths globally in 2021 [4]. Understanding the fundamental genetic mechanisms driving resistance—from point mutations to horizontal gene transfer—is therefore essential for developing effective countermeasures.

The advent of next-generation sequencing technologies, particularly whole-genome sequencing (WGS), has revolutionized our ability to identify and track ARGs across clinical, agricultural, and environmental settings [4]. This Application Note details the principal mechanisms of antibiotic resistance and provides standardized protocols for their identification within the context of a WGS pipeline for resistance gene identification research. The content is specifically tailored to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in advancing AMR surveillance and mitigation strategies.

Fundamental Resistance Mechanisms

Bacteria employ a diverse arsenal of biochemical strategies to overcome antibiotic action. These mechanisms can be broadly categorized into five core types, each with distinct genetic bases and phenotypic manifestations.

Target Modification and Mutation

Chromosomal point mutations in genes encoding antibiotic target sites represent a primary pathway for resistance development. These alterations reduce drug binding affinity without compromising the target's essential cellular function [4]. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, mutations in genes like rpoB (conferring rifampicin resistance) and gyrA (conferring fluoroquinolone resistance) are classic examples [11] [12]. Gram-positive pathogens can develop reduced susceptibility to last-line antibiotics like daptomycin and linezolid through mutations in multiple genetic loci [9]. Specialized databases such as PointFinder have been developed specifically to catalogue and identify these resistance-conferring mutations [4].

Enzymatic Inactivation and Modification

Bacteria produce a vast array of enzymes that directly inactivate antibiotics. β-Lactamases, including extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) like blaCTX-M, hydrolyze the β-lactam ring of penicillins, cephalosporins, and related drugs [9] [5]. Other enzymes mediate chemical modification of antibiotics through group transfer; acetyltransferases modify aminoglycosides, and phosphotransferases alter chloramphenicol [9]. These resistance genes are often acquired via horizontal gene transfer and can be identified using homology-based tools like ResFinder [4].

Efflux Pump Upregulation

Membrane-associated efflux pumps actively export antibiotics from the bacterial cell, reducing intracellular concentrations to subtoxic levels [9]. These systems can be specific for a single drug class or function as multi-drug transporters, conferring broad resistance. Upregulation of efflux activity can occur through mutations in regulatory genes or through acquisition of pump-encoding genes on mobile genetic elements [9] [4]. In Gram-negative bacteria, the combination of efflux pumps and reduced membrane permeability creates a particularly effective barrier to antimicrobial agents [9].

Reduced Permeability and Biofilm Formation

Structural changes to cell envelope components can significantly reduce antibiotic penetration. Gram-negative bacteria possess an inherent advantage due to their outer membrane, which acts as a formidable permeability barrier [9]. Additionally, many bacterial species can form biofilms—structured communities encased in an extracellular matrix. The biofilm phenotype provides profound resistance by creating physical diffusion barriers, housing metabolic heterogeneities including dormant persister cells, and enabling increased frequency of horizontal gene transfer [9].

Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT)

HGT facilitates the rapid dissemination of ARGs between bacteria through three primary mechanisms:

- Conjugation: Direct cell-to-cell transfer of plasmids, integrons, or transposons carrying resistance cassettes. This is the dominant pathway for disseminating genes encoding ESBLs, carbapenemases, and glycopeptide resistance [9] [4].

- Transformation: Uptake and incorporation of free environmental DNA from lysed cells. This mechanism allows for the acquisition of resistance genes, including those released from biofilms [9].

- Transduction: Bacteriophage-mediated transfer of genetic material between bacterial hosts. Recent evidence confirms ARGs, including blaCTX-M and tet(A), can be detected in phage-associated DNA fractions from wastewater and biosolids, highlighting their potential role as environmental resistance reservoirs [13].

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance

| Mechanism | Genetic Basis | Key Examples | Primary Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Modification | Chromosomal point mutations | rpoB (Rifampicin), gyrA (Quinolones) | PointFinder, TB-Profiler [11] [4] |

| Enzymatic Inactivation | Acquired resistance genes | β-lactamases (e.g., blaCTX-M), acetyltransferases | ResFinder, CARD [4] [5] |

| Efflux Pump Upregulation | Regulatory mutations or acquired pump genes | Multi-drug efflux systems in Gram-negative bacteria | CARD, Custom analysis [9] [4] |

| Reduced Permeability | Alterations in porin genes or outer membrane structure | LPS modifications in polymyxin resistance | Genomic analysis [9] |

| Biofilm Formation | Regulation of matrix production and persister cell formation | ica operon in S. aureus, alginate in P. aeruginosa | VirulenceFinder, VFDB [9] [5] |

Quantitative Analysis of Resistance Patterns

Surveillance data and research studies provide critical insights into the prevalence and distribution of resistance mechanisms. The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from recent genomic studies to illustrate current resistance trends.

Table 2: Drug Resistance Profile in M. tuberculosis from a Low-Incidence Region (Huzhou, China; n=350 isolates) [11]

| Resistance Category | Prevalence (%) | Defining Resistance Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Any Drug Resistance | 24.6% (86/350) | Resistance to ≥1 first-line drug |

| Multidrug-Resistant (MDR-TB) | 2.0% (7/350) | Resistance to both rifampicin and isoniazid |

| Pre-Extensively Drug-Resistant (pre-XDR-TB) | 1.7% (6/350) | MDR + fluoroquinolone resistance |

| Extensively Drug-Resistant (XDR-TB) | 0% (0/350) | MDR + fluoroquinolone + Group A drug resistance |

Table 3: Performance Comparison of WGS Technologies for AMR Detection [12] [5]

| Sequencing & Analysis Parameter | Rapid Nanopore (ONT20h) | Illumina Technology (IT) | Hybrid Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Results | ~20 hours sequencing | ~56 hours sequencing | ~20-56 hours [5] |

| Concordance with Phenotypic DST | High agreement demonstrated | High agreement demonstrated | Not specified |

| Lineage Calling Accuracy | 94% concordance with Illumina (16/17 isolates) | Reference standard | Not specified |

| Resistance SNP Identification | 100% concordance with Illumina (17/17 isolates) | Reference standard | Not specified |

| Cost & Expertise Requirements | Lower time requirement, less expertise for analysis | Higher expertise for analysis | Most complex setup |

Experimental Protocols for Resistance Gene Identification

Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tuberculosis Drug Resistance

Application: This protocol provides a standardized workflow for DNA extraction, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis to identify drug resistance and lineage in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates [12].

Materials:

- M. tuberculosis isolates from cultured sputum samples

- Lowenstein-Jensen medium or Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar

- Mag-MK Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Sangon Biotech) or CTAB-based method

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) RBK110.96 library preparation kit

- Nanopore GridION or PromethION sequencer

- Computational resources for bioinformatics analysis

Procedure:

- Culture and DNA Extraction:

- Subculture isolates on Lowenstein-Jensen medium for 3-4 weeks at 37°C.

- Harvest bacterial colonies and extract genomic DNA using a spin-column CTAB method.

- Quantify DNA concentration using Qubit Fluorometer.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries using the ONT RBK110.96 kit according to manufacturer specifications.

- Load libraries onto a Nanopore GridION sequencer.

- Perform sequencing for approximately 20 hours using high-accuracy (HAC) basecalling.

Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Perform quality control on FASTQ files using fastp v0.23 (quality threshold ≥Q20).

- Align reads to M. tuberculosis reference genome H37Rv using BWA-MEM.

- Call variants using SAMtools/BCFtools with threshold of ≥90% frequency and ≥5 supporting reads.

- Analyze resistance mutations and lineage using TB-Profiler.

Validation: This pipeline demonstrated 71% (12/17) concordance with phenotypic drug susceptibility testing and 100% concordance with Illumina for resistance SNP identification [12].

Metagenomic Detection of ARGs in Complex Matrices

Application: This protocol compares concentration and detection methods for identifying ARGs in environmental samples, particularly treated wastewater and biosolids, including their phage-associated fractions [13].

Materials:

- Secondary treated wastewater (200mL) and biosolid samples

- 0.45µm sterile cellulose nitrate filters (MicroFunnel)

- Aluminum chloride (AlCl₃) solution (0.9N)

- Beef extract (3%, pH 7.4)

- Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO and Authentication Kit (Promega)

- Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) system or quantitative PCR (qPCR) instrumentation

- Chloroform and 0.22µm PES membranes

Procedure:

- Sample Concentration (Comparative):

- Filtration-Centrifugation (FC) Method: Filter 200mL wastewater through 0.45µm filter. Resuspend filter in buffered peptone water, sonicate, and concentrate via centrifugation at 9000×g for 10 minutes.

- Aluminum Precipitation (AP) Method: Adjust wastewater pH to 6.0. Add AlCl₃ (1:100 v/v), shake at 150rpm for 15min, and centrifuge at 1700×g for 20min. Resuspend pellet in 3% beef extract.

DNA Extraction:

- Extract nucleic acids from concentrates using Maxwell RSC system with Pure Food GMO program.

- Elute DNA in 100µL nuclease-free water.

Phage DNA Purification:

- Filter concentrates through 0.22µm PES membranes.

- Treat filtrate with chloroform (10% v/v), vortex, and centrifuge to separate phases.

- Recover aqueous phase for analysis.

ARG Detection and Quantification:

- Analyze samples using both qPCR and ddPCR for target ARGs (e.g., tet(A), blaCTX-M, qnrB, catI).

- For ddPCR, partition samples into nanoliter droplets and amplify with target-specific primers/probes.

Performance Notes: The AP method yields higher ARG concentrations than FC in wastewater samples. ddPCR demonstrates superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets in complex matrices like wastewater, while performance in biosolids is more comparable between detection platforms [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for ARG Identification

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) | Manually curated database | Catalogs resistance elements using Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) | Reference for RGI tool; ideal for known, validated ARGs [4] |

| ResFinder/PointFinder | Bioinformatics tool | Identifies acquired resistance genes (ResFinder) and chromosomal mutations (PointFinder) | K-mer-based detection from raw reads; species-specific mutation detection [4] |

| TB-Profiler | Specialized analysis tool | Determines lineage and drug resistance profile from M. tuberculosis sequences | Optimized for TB WGS analysis; used in pragmatic diagnostic pipelines [11] [12] |

| Oxford Nanopore RBK110.96 | Library preparation kit | Rapid barcoding for multiplexed WGS on Nanopore platforms | Enables fast (20h) sequencing for timely AMR diagnosis [12] [5] |

| Maxwell RSC Pure Food GMO Kit | Nucleic acid extraction system | Automated purification of DNA from complex matrices | Effective for environmental samples (wastewater, biosolids) [13] |

Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Fundamental antibiotic resistance mechanisms and their relationship to horizontal gene transfer. HGT accelerates the dissemination of genetic determinants encoding specific resistance mechanisms [9] [4].

Diagram 2: End-to-end workflow for whole-genome sequencing-based antibiotic resistance identification, integrating wet-lab and computational steps [11] [12] [5].

The escalating global AMR crisis demands sophisticated approaches to resistance detection and monitoring. The fundamental mechanisms—from point mutations that subtly alter drug targets to the rapid dissemination of resistance genes via horizontal transfer—create a complex landscape that requires integrated genomic solutions. The protocols and analyses presented here provide a framework for implementing WGS-based resistance surveillance, enabling researchers to accurately characterize resistance patterns, understand transmission dynamics, and inform public health interventions. As resistance continues to evolve, leveraging these tools within a One Health framework that connects human, animal, and environmental surveillance will be crucial for effective mitigation.

Within the framework of a whole-genome sequencing (WGS) pipeline for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, the selection of an appropriate sequencing platform is a critical foundational decision. The identification of resistance genes (ARGs), particularly those embedded within complex mobile genetic elements or challenging genomic regions, places specific demands on sequencing technologies. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms have evolved into three principal paradigms: Illumina, renowned for its high-throughput and accuracy; Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), distinguished by its highly accurate long reads (HiFi); and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), recognized for its ultra-long reads and real-time sequencing capabilities [14]. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these platforms, summarizing their quantitative performance and detailing experimental protocols tailored for WGS in AMR research.

Platform Comparison and Selection Guide

The choice of sequencing technology directly influences the completeness and accuracy of the resulting genomic data, which is paramount for confidently identifying ARGs and understanding their genomic context and mechanisms of horizontal transfer.

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of Major WGS Platforms

| Feature | Illumina (e.g., NovaSeq X) | PacBio (HiFi Sequencing) | Oxford Nanopore (e.g., PromethION) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Type | Short reads (paired-end) | Long, highly accurate reads (HiFi) | Ultra-long reads |

| Typical Read Length | Up to 2x300 bp [15] | Up to 25 kb [16] | N50 > 100 kb, can exceed 1 Mb [14] |

| Maximum Output | Up to 16 Tb (NovaSeq X Plus) [17] | Varies by instrument | Several Tb per flow cell (PromethION) [14] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) [18] | >99.9% (Q30) [16] | ~99% (Q20) with Q20+ chemistry [14] |

| Variant Calling Strength | Excellent for SNVs, small indels [18] | Comprehensive for SNVs, indels, SVs, STRs [19] | Excellent for SVs, methylation, large repeats |

| Methylation Detection | Requires bisulfite conversion | Direct detection (5mC) as standard [16] [19] | Direct detection of 5mC, 6mA in native DNA [14] |

| Time to Result | ~1-3 days | ~0.5-2 days | Minutes to hours from sample prep [14] |

| Portability | Benchtop to production-scale | Benchtop | High (MinION is pocket-sized) [14] |

| Key Advantage in AMR | High accuracy for SNVs in ARGs | Phased, complete ARG haplotypes and plasmid context | Real-time surveillance; complete assembly of resistance plasmids [14] |

Table 2: Performance in Application to AMR Research

| Parameter | Illumina | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARG Identification | High for known genes from databases | High, enables discovery in complex loci | High, enhanced by real-time analysis |

| Plasmid Reconstruction | Poor, requires complex assembly | High-quality, closed plasmids [14] | High-quality, closed plasmids, even large ones [14] |

| Context of ARG (Location, MGEs) | Limited | Excellent [19] | Excellent [14] |

| Detection of Epigenetic Modifications | Indirect, requires special prep | Direct, inherent [16] | Direct, inherent [14] |

| Typical Workflow | Batch processing | Batch processing | Real-time, adaptive sampling [14] |

| Best Suited For | Large-scale SNP screening, expression studies | Reference-quality genomes, resolving complex AMR loci [19] | Rapid diagnostics, ultra-long range genomics, field sequencing [14] |

Experimental Protocols for WGS in AMR Research

DNA Extraction Protocol for Long-Read Sequencing

Principle: High-molecular-weight (HMW) and high-purity genomic DNA is critical for successful long-read sequencing. The protocol below is optimized for bacterial cultures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for HMW DNA Extraction

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Quick-DNA HMW MagBead Kit (Zymo Research) | Magnetic bead-based purification of HMW DNA. |

| Proteinase K | Digests nucleases and cellular proteins to prevent DNA degradation. |

| RNase A | Removes RNA contamination that can affect quantification and library prep. |

| Magnetic Stand | For efficient separation of MagBeads from supernatant. |

| Qubit Fluorometer & dsDNA HS Assay | Accurate quantification of double-stranded DNA, superior for library prep. |

| Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) | Assay for verifying DNA fragment size is >20 kb. |

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Harvest bacterial cells and resuspend in lysis buffer containing Proteinase K. Incubate at 55°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Bead Binding: Add MagBeads to the lysate and incubate with mixing. DNA binds to the bead surface.

- Washing: Place the tube on a magnetic stand to pellet beads. Remove supernatant and wash beads with prepared wash buffers to remove contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the pure HMW DNA in a low-EDTA elution buffer or nuclease-free water. Pre-warm the elution buffer to 55°C to improve yield.

- Quality Control:

- Quantification: Use Qubit dsDNA HS Assay.

- Size Assessment: Analyze DNA integrity by PFGE or the Fragment Analyzer system. A successful prep should show a dominant band >20 kb.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

The following workflows outline the standard methods for each platform as applied in recent AMR studies.

Diagram: Comparative WGS Workflows for AMR Research

A. Illumina WGS Protocol (e.g., for NovaSeq X)

- Library Preparation: Use the Illumina DNA Prep kit. The process involves tagmentation (simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging), followed by PCR amplification to incorporate unique dual indices for sample multiplexing [20] [17].

- Sequencing: Load the normalized and pooled library onto a NovaSeq X flow cell. Sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry generates billions of short, paired-end reads (e.g., 2x150 bp). Base calling and primary analysis are performed in real-time by the instrument's onboard software [17].

- Secondary Analysis: Process raw data (BCL files) through the DRAGEN (Dynamic Read Analysis for GENomics) platform for ultra-rapid secondary analysis, including alignment, variant calling (SNVs, indels), and de novo assembly [18] [17].

B. PacBio HiFi WGS Protocol

- Library Preparation: Construct a SMRTbell library by fragmenting HMW DNA, repairing ends, and ligating universal hairpin adapters to create closed, circular DNA templates [16] [19].

- Sequencing: Bind the SMRTbell library to polymerase and load onto a SMRT cell on the Sequel IIe or Revio system. During sequencing, the polymerase repeatedly traverses the circular template, generating multiple subreads of the same insert. These subreads are processed to produce one HiFi read with >99.9% accuracy through Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) [16].

- Data Analysis: HiFi reads can be used for highly accurate de novo assembly with tools like Flye or hifiasm, or mapped directly to a reference genome for comprehensive variant calling, including structural variants and base modifications.

C. Oxford Nanopore WGS Protocol (e.g., for PromethION)

- Library Preparation: Use the Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114). The protocol involves DNA repair and end-prep, followed by adapter ligation. Native barcoding kits (e.g., SQK-NBD114) allow for multiplexing without PCR amplification, preserving base modifications [14] [21].

- Sequencing: Load the library onto a R10.4.1 or newer flow cell in a PromethION or GridION device. As DNA strands are translocated through the nanopores by a motor protein, changes in ionic current are measured in real-time. The Dorado basecaller converts raw signal to nucleotide sequence, often integrated with adaptive sampling for target enrichment [14].

- Data Analysis: Basecalled FASTQ files can be assembled in real-time using tools like Shasta or Flye. The signal-level data also allows for direct detection of DNA modifications, such as 5mC, using tools like Dorado with modified base models.

The optimal sequencing platform for a WGS pipeline in AMR research is dictated by the specific scientific question. Illumina remains the workhorse for cost-effective, high-accuracy variant screening at scale. PacBio HiFi sequencing is the superior choice for generating reference-quality genomes that completely resolve ARG contexts, plasmid structures, and epigenetic markers. Oxford Nanopore provides unparalleled capabilities for rapid diagnostics, real-time surveillance, and the assembly of the most complex and repetitive genomic regions due to its ultra-long reads. A strategic approach, potentially involving a hybrid of these technologies, will most effectively empower researchers to unravel the complexities of antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a critical global health threat, with resistant microorganisms contributing to increased mortality rates and substantial economic burdens on healthcare systems worldwide [22]. The rise of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has revolutionized AMR surveillance, enabling researchers to analyze antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) from both bacterial whole genomes and complex metagenomic datasets [4]. Effective in silico approaches for identifying ARGs in resistant isolates have become essential tools that leverage whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data to detect resistance determinants with high accuracy [22].

Within this landscape, specialized ARG databases serve as fundamental resources for cataloging, annotating, and analyzing genetic determinants of resistance. This application note provides a comprehensive technical analysis of three pivotal ARG databases: the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), ResFinder, and MEGARes. Each database offers unique strengths in content, curation methodology, and analytical capabilities, making them suitable for different applications within whole-genome sequencing pipelines for resistance gene identification [4] [23]. We examine their structural architectures, annotation frameworks, and implementation protocols to guide researchers in selecting appropriate resources for their AMR research and surveillance objectives.

Database Architectures and Comparative Analysis

Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)

CARD represents a rigorously curated bioinformatic database of resistance genes, their products, and associated phenotypes, organized according to the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) [24] [4]. This ontology-driven framework classifies resistance determinants, mechanisms, and affected antibiotic molecules across three primary branches: Determinants of Antibiotic Resistance, Mechanisms of Resistance, and Antibiotic Molecules [4]. CARD employs strict inclusion criteria requiring that all ARG sequences be deposited in GenBank, demonstrate an experimentally validated increase in Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), and have results published in peer-reviewed journals, with limited exceptions for certain historical β-lactam antibiotics [4].

The database encompasses extensive content, including 8,582 ontology terms, 6,442 reference sequences, 4,480 SNPs, and 3,354 publications [24]. A key feature is the "Resistomes & Variants" database, which contains in silico-validated ARGs derived from sequences stored in CARD, thereby extending the range of ARGs available for computational analyses while maintaining quality standards [4]. CARD also provides analytical tools, most notably the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) software, which predicts ARGs in genomic or metagenomic sequences based on curated reference sequences and a trained BLASTP alignment bit-score threshold [24] [4].

ResFinder Database

ResFinder is a specialized bioinformatics tool focused on identifying acquired AMR genes categorized by antimicrobial classes and resistance mechanisms [4]. Originally derived from the Lahey Clinic β-Lactamase Database, ARDB, and extensive literature review, ResFinder detects acquired resistance genes using a K-mer-based alignment algorithm that enables rapid analyses directly from raw sequencing reads without de novo assembly [4]. This approach facilitates efficient screening of genomic data and is particularly valuable for clinical applications requiring timely results.

Integrated with ResFinder is PointFinder, a specialized tool for detecting chromosomal point mutations conferring resistance in specific bacterial species [4]. This integration provides researchers with detailed insights into resistance mechanisms at a finer scale, covering a wide array of acquired genes and resistance mutations. The combined resource includes phenotype prediction tables that link genetic information to potential resistance traits, enhancing its utility for both research and clinical applications [4]. The ResFinder database (version 2.4.0) contains 3,150 alleles and is licensed under the Apache License 2.0, permitting free use, modification, and distribution [22].

MEGARes Database

MEGARes (version 3.0) incorporates approximately 9,000 hand-curated antimicrobial resistance genes within an annotation structure specifically optimized for high-throughput sequencing [25]. The database features an acyclical annotation graph that enables accurate, count-based, hierarchical statistical analysis of resistance at the population level, similar to microbiome analysis approaches [25]. This structure is specifically designed for use as a training database for creating statistical classifiers, making it particularly valuable for metagenomic resistome studies.

The MEGARes database is integrated with the AMR++ bioinformatics pipeline, which facilitates the analysis of raw sequencing reads to characterize antimicrobial resistance gene profiles, or resistomes [25]. AMR++ version 3.0 includes a specialized feature for high-throughput verification of resistance-conferring SNPs in relevant gene accessions, enhancing its utility for comprehensive AMR analysis [25]. This combination of curated database and analytical pipeline supports robust metagenomic investigations of antimicrobial resistance using genomic sequencing and high-throughput computational analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key ARG Database Content and Features

| Feature | CARD | ResFinder | MEGARes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Ontology-based resistance classification | Acquired AMR genes & point mutations | Hand-curated genes for metagenomic analysis |

| Content Scope | 8,582 ontology terms, 6,442 reference sequences, 4,480 SNPs [24] | 3,150 alleles (version 2.4.0) [22] | ~9,000 hand-curated antimicrobial resistance genes [25] |

| Curation Method | Rigorous manual curation with experimental validation required [4] | Integration of multiple sources with K-mer-based detection [4] | Hand-curated with acyclical annotation structure [25] |

| Key Tools | Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI), CARD:Live, CARD Bait Capture [24] | Integrated with PointFinder for mutation analysis [4] | AMR++ pipeline for raw read analysis [25] |

| Mutation Coverage | Chromosomal mutations & SNPs via PointFinder integration [4] | Specialized in point mutations via PointFinder [4] | Limited SNP verification in AMR++ v3.0 [25] |

| Primary Application | Comprehensive resistome prediction & analysis [24] | Rapid screening of acquired resistance [4] | Metagenomic resistome profiling & statistical analysis [25] |

Table 2: Database Integration in Analysis Tools

| Tool | Supported Databases | Primary Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| AmrProfiler | ResFinder, CARD, Reference Gene Catalog [22] | Identifies acquired AMR genes, mutations, and rRNA mutations | First tool to systematically report mutations in rRNA genes [22] |

| RGI | CARD [24] | Predicts ARGs based on curated reference sequences | Uses trained BLASTP alignment bit-score threshold for higher accuracy [4] |

| ResFinder | ResFinder, PointFinder [4] | Detects acquired AMR genes and mutations | K-mer-based algorithm works directly on raw reads without assembly [4] |

| AMR++ | MEGARes [25] | Characterizes resistomes from raw sequencing reads | Integrated pipeline optimized for metagenomic analysis [25] |

Integrated Analysis Protocols for WGS Pipelines

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Resistome Profiling Using CARD and RGI

The Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) software serves as the primary analytical tool for CARD, providing robust resistome prediction based on homology and SNP models [24]. The following protocol outlines the standard workflow for whole-genome sequence analysis:

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Obtain whole-genome sequencing data in FASTA or FASTQ format

- For raw reads (FASTQ), perform quality control using tools such as FastQC and Trimmomatic

- Assemble high-quality reads into contigs using appropriate assemblers (SPAdes, SKESA) for chromosome and plasmid reconstruction

Step 2: RGI Analysis Execution

- Install RGI software (available as command-line tool from CARD website)

- Run RGI against assembled contigs using default parameters for comprehensive resistome prediction:

rgi main --input_sequence assembly.fasta --output_file resistome_results --local - For metagenomic reads, use the RGI main function with read filtering:

rgi main --input_sequence metagenome.fastq --output_file metagenome_resistome --local --include_loose

Step 3: Results Interpretation

- Analyze the output tabular file containing ARG identifications with percentage identities, coverage, and resistance mechanism annotations

- Cross-reference identified ARGs with the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) terms for mechanistic insights

- Utilize CARD:Live feature for comparing results with community-submitted resistome information to identify emerging resistance patterns [24]

Step 4: Visualization and Reporting

- Generate AMR gene maps showing genomic context of resistance determinants

- Create heatmaps of resistance classes for multiple sample comparisons

- Annotate identified ARGs with associated metadata including PubMed IDs and phenotypic information [22]

This protocol leverages CARD's strengths in ontology-driven classification and rigorous curation, making it particularly suitable for research requiring detailed mechanistic insights into resistance determinants.

Protocol 2: Rapid Screening of Acquired Resistance Using ResFinder

ResFinder provides an optimized workflow for rapid identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes, particularly valuable in clinical settings where timely results are critical:

Step 1: Data Preparation

- Collect whole-genome sequencing data (assembled genomes or raw reads)

- Ensure data meets minimum quality requirements (coverage >30x, contamination <5%)

Step 2: Gene Identification Using ResFinder

- Access ResFinder through web interface or command-line implementation

- For assembled genomes: Submit FASTA file to ResFinder with default thresholds (90% identity, 60% coverage)

- For raw reads: Utilize the integrated K-mer-based algorithm for direct analysis without assembly, significantly reducing processing time [4]

- For point mutation detection, concurrently run PointFinder to identify chromosomal mutations associated with resistance

Step 3: Phenotype Prediction

- Consult the integrated phenotype prediction tables to link identified genetic determinants to potential resistance traits

- Correlate acquired ARGs with species-specific point mutations for comprehensive resistance profiling

- Identify potential multi-drug resistance patterns based on the repertoire of detected genes

Step 4: Reporting

- Generate summary reports highlighting clinically relevant resistance determinants

- Flag critical resistance markers (e.g., carbapenemases, ESBLs) for immediate attention

- Export results in standardized formats for electronic health record integration when applicable

The ResFinder protocol excels in clinical surveillance scenarios where efficient detection of acquired resistance genes and rapid turnaround times are prioritized.

Protocol 3: Metagenomic Resistome Analysis with MEGARes and AMR++

The MEGARes database and AMR++ pipeline form an integrated system specifically designed for metagenomic resistome profiling, enabling population-level analysis of antimicrobial resistance in complex microbial communities:

Step 1: Metagenomic Read Processing

- Obtain raw metagenomic sequencing reads in FASTQ format

- Perform adapter trimming and quality filtering using integrated AMR++ preprocessing modules

- Retain paired-end read information for improved mapping accuracy

Step 2: AMR++ Pipeline Execution

- Configure AMR++ workflow parameters, specifying MEGARes as the reference database

- Execute the main analysis pipeline:

amrplusplus_pipeline.py --input reads/ --output results/ --database MEGARes_v3.0 - Enable SNP verification module for detection of resistance-conferring single nucleotide polymorphisms in relevant gene accessions [25]

Step 3: Hierarchical Statistical Analysis

- Utilize the acyclical annotation graph of MEGARes to perform count-based, hierarchical statistical analysis of resistance at multiple classification levels [25]

- Normalize ARG abundances using appropriate scaling factors (e.g., reads per kilobase million)

- Calculate resistance class proportions and diversity metrics within and between samples

Step 4: Population-Level Interpretation

- Generate resistance heatmaps and ordination plots to visualize resistome patterns across sample groups

- Perform statistical testing to identify differentially abundant resistance mechanisms between conditions

- Correlate resistome profiles with microbial community composition data when available

This protocol is particularly powerful for environmental monitoring, microbiome studies, and One Health approaches where understanding the distribution and dynamics of resistance elements across complex microbial ecosystems is essential.

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Integrated bioinformatics workflow for antimicrobial resistance gene detection incorporating CARD, ResFinder, and MEGARes databases. The pipeline processes whole-genome sequencing data through quality control and assembly steps before database-specific analysis, culminating in an integrated AMR report for research or clinical interpretation.

Table 3: Computational Tools for ARG Analysis in WGS Pipelines

| Tool/Resource | Function | Compatible Databases | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGI (Resistance Gene Identifier) | Resistome prediction | CARD [24] | Ontology-based classification, homology & SNP models |

| AmrProfiler | Comprehensive AMR analysis | ResFinder, CARD, Reference Gene Catalog [22] | Identifies acquired genes, mutations, and rRNA mutations |

| AMRFinderPlus | AMR gene & mutation detection | NCBI Reference Gene Catalog [22] [23] | Detects genes and point mutations, stand-alone tool |

| Abricate | Gene screening | Multiple databases including CARD [23] | Batch screening of assembled contigs, user-defined thresholds |

| Kleborate | Species-specific analysis | K. pneumoniae-focused [23] | Species-specific variant cataloging, less spurious matching |

| DeepARG | Machine learning-based prediction | DeepARG database [23] | Uncovers novel/low-abundance ARGs, AI-based approach |

Table 4: Database Content and Accessibility

| Resource | Content Type | Update Frequency | Access | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARD | ARO terms, reference sequences, SNPs, publications [24] | Regular with manual curation [4] | Web interface, download, API [24] | Free for academic use, license required for commercial [22] |

| ResFinder | Acquired AMR genes, alleles [22] [4] | Regular updates | Web interface, download [4] | Apache License 2.0 [22] |

| MEGARes | Hand-curated AMR genes, annotation structure [25] | Versioned releases | Download [25] | Open science, freely available |

| PointFinder | Chromosomal point mutations [4] | Integrated with ResFinder | Web interface, download [4] | Apache License 2.0 [22] |

| Reference Gene Catalog | AMR genes from NCBI [22] | Regular updates (e.g., 2024-12-18.1) [22] | Download from NCBI FTP | Public domain (U.S. Government Work) [22] |

The strategic selection and implementation of ARG databases within whole-genome sequencing pipelines significantly influences the depth and accuracy of antimicrobial resistance research. CARD, ResFinder, and MEGARes each offer distinctive advantages: CARD provides ontology-driven comprehensive classification ideal for mechanistic studies; ResFinder enables rapid detection of acquired resistance genes valuable for clinical surveillance; and MEGARes supports population-level metagenomic analysis essential for understanding resistome dynamics in complex microbial communities.

Recent advancements in bioinformatic tools like AmrProfiler, which integrates multiple databases to identify acquired AMR genes, resistance-associated mutations, and previously overlooked rRNA mutations, demonstrate the power of combining these resources [22]. As AMR continues to evolve as a critical public health challenge, the ongoing development and refinement of these databases—coupled with integrated analysis protocols—will remain fundamental to advancing both research and clinical applications in antimicrobial resistance. Researchers should consider implementing complementary database strategies to address specific research questions while acknowledging the limitations inherent in each resource, particularly regarding curation methodologies, update frequencies, and coverage of emerging resistance mechanisms.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents one of the most pressing global health threats, directly causing an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually and contributing to millions more [26]. The rapid proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) undermines the efficacy of existing treatments, threatening decades of medical progress [4]. Within this context, whole-genome sequencing has emerged as a powerful approach for monitoring the spread and emergence of resistance determinants, enabling researchers to identify ARGs from both bacterial genomes and complex metagenomic datasets [4] [27].

The bioinformatic tools developed for ARG detection primarily fall into two methodological categories: alignment-based approaches and machine learning-based methods. Alignment-based tools such as AMRFinderPlus rely on sequence similarity to curated reference databases, while deep learning approaches like DeepARG and HMD-ARG leverage artificial neural networks to identify abstract patterns associated with resistance determinants, enabling detection of novel ARGs with limited sequence similarity to known references [26] [28] [4]. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of three prominent ARG detection tools—AMRFinderPlus, DeepARG, and HMD-ARG—within the context of a whole-genome sequencing pipeline for resistance gene identification, offering structured performance data, experimental protocols, and practical implementation guidelines for researchers and drug development professionals.

AMRFinderPlus: A Curated Alignment-Based Approach

Developed and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), AMRFinderPlus is an alignment-based tool that identifies AMR genes, resistance-associated point mutations, and other relevant genetic elements using protein annotations and/or assembled nucleotide sequence [29]. This tool forms the core of NCBI's Pathogen Detection pipeline, with results publicly available through the Isolate Browser [29]. AMRFinderPlus operates by comparing query sequences against NCBI's curated Reference Gene Database and collection of Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), employing carefully determined cutoffs to distinguish between known alleles and novel variants [29]. The tool provides comprehensive AMR genotype information, including designated gene symbols and allele names, facilitating standardized reporting across studies.

DeepARG: Pioneering Deep Learning for ARG Detection

DeepARG represents one of the first deep learning-based frameworks developed to address limitations inherent in alignment-based methods [26] [30]. This tool employs a deep learning model trained to identify ARGs without direct sequence alignment to known references, thereby reducing false-negative rates associated with strict similarity cutoffs (typically >80-95%) used by traditional methods [26] [30]. While initial versions incorporated some alignment components in their workflow, DeepARG demonstrated the potential of artificial neural networks to learn complex, non-linear rules from ARG sequence data, achieving remarkable results in multiclass classification of resistance proteins with lower false negative rates than alignment-based alternatives [26].

HMD-ARG: Hierarchical Multi-Task Deep Learning

HMD-ARG represents a significant advancement in deep learning approaches for ARG annotation, implementing an end-to-end hierarchical multi-task deep learning framework [28]. Unlike tools that provide single-dimensional outputs, HMD-ARG employs a level-by-level prediction strategy that annotates ARGs from multiple perspectives: (1) identifying whether a protein sequence is an ARG; (2) determining which of 15 antibiotic families it confers resistance to; (3) elucidating the biochemical resistance mechanism (e.g., antibiotic efflux, inactivation, target alteration); and (4) predicting gene mobility (intrinsic versus acquired) [28]. For beta-lactamase genes, HMD-ARG further predicts the molecular subclass, providing exceptionally detailed characterization in a single analysis workflow [28].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of ARG Detection Tools

| Feature | AMRFinderPlus | DeepARG | HMD-ARG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Alignment-based | Deep learning | Hierarchical multi-task deep learning |

| Database | NCBI Curated Reference Gene Database | Non-redundant Comprehensive Database (NCRD) | HMD-ARG-DB (17,282 sequences) |

| Primary Advantage | Standardized annotation, connection to NCBI resources | Detection of novel ARGs with limited homology | Multi-faceted annotation in a single workflow |

| Output Types | AMR genes, point mutations, stress genes | ARG identification and classification | ARG identification, antibiotic class, mechanism, mobility |

| Classification Granularity | Gene-specific | Resistance classes | Multiple hierarchical levels |

| Reference | [29] | [26] [30] | [28] |

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking

Independent evaluations have demonstrated distinct performance characteristics across the three tools. Deep learning-based approaches consistently show superior recall values (>0.9) compared to alignment-based methods across all protein classes tested, significantly reducing false-negative rates [26] [30]. This enhanced sensitivity is particularly valuable for detecting novel or divergent ARGs that may be missed by strict similarity thresholds.

HMD-ARG has demonstrated robust performance in comprehensive benchmarking studies, accurately predicting multiple ARG properties simultaneously while maintaining high precision across different resistance classes [28]. The tool's hierarchical architecture effectively addresses class imbalance issues common in ARG datasets, particularly for rare resistance types.

AMRFinderPlus maintains advantages in standardization and connection to clinical reporting frameworks, with carefully curated cutoffs that minimize false-positive assignments, particularly for novel alleles [29]. The tool's integration with NCBI's pathogen surveillance ecosystem provides additional contextual information valuable for public health applications.

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Operational Characteristics

| Characteristic | AMRFinderPlus | DeepARG | HMD-ARG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recall | Varies by gene/threshold | >0.9 for most classes [26] | >0.9 for most classes [28] |

| Novel ARG Detection | Limited to close homologs | Moderate capability | High capability |

| Multi-label Classification | Limited | No | Yes (antibiotic class, mechanism, mobility) |

| Computational Demand | Moderate | Moderate to High | Moderate to High |

| Strengths | Standardization, clinical relevance | Novel ARG detection | Comprehensive annotation |

| Limitations | Database-dependent, limited novel detection | Limited explainability | Complex model architecture |

| Ideal Use Case | Routine surveillance, clinical isolates | Exploratory studies, environmental samples | Comprehensive resistome characterization |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Sample Preparation and Sequencing Requirements

For optimal ARG detection using any of the three tools, the following sample preparation and sequencing standards are recommended:

- DNA Extraction: Use mechanical lysis methods proven effective for diverse bacterial populations, particularly for metagenomic samples where Gram-positive bacteria may be underrepresented with enzymatic lysis alone.

- Sequencing Depth: Minimum of 10-20 million read pairs per metagenomic sample for adequate coverage of low-abundance resistance determinants.

- Sequence Quality Control: Implement adapter trimming, quality filtering (Q-score ≥30), and host sequence removal (for host-associated samples) prior to analysis.

- Assembly: For assembly-based approaches, use optimized assemblers such as MEGAHIT or SPAdes with parameters appropriate for your dataset complexity [28].

AMRFinderPlus Implementation Protocol

Installation:

Database Setup:

Basic Execution:

Critical Parameters:

--identityand--coverage: Adjust alignment thresholds (defaults optimized for curated database)--plus: Include additional non-AMR elements (stress genes, virulence factors)--organism: Specify organism for point mutation detection (e.g., Escherichia, Salmonella)

Output Interpretation:

- Results include gene name, allele designation, sequence coverage, identity percentage, and predetermined cutoff criteria for novel allele designation.

- The "Reference Gene Catalog" web interface provides detailed biological context for identified genes.

DeepARG Implementation Protocol

Database Preparation:

Sequence Analysis:

Key Parameters:

--model: Select model type (LS for long sequences, SS for short reads)--arg-prob: Probability threshold for ARG classification (default: 0.8)--min-prob: Minimum probability for gene classification

Result Interpretation:

- Output includes ARG probability scores, best-matching gene family, and resistance mechanism predictions.

- Lower probability thresholds increase sensitivity for novel ARGs but may reduce specificity.

HMD-ARG Implementation Protocol

Environment Setup:

Model Prediction:

Advanced Options:

--task: Specify prediction task (identification, classification, mechanism, mobility)--hierarchy: Enable full hierarchical prediction (default: True)--visualize: Generate explanatory visualizations for predictions

Output Interpretation:

- Results provided across multiple files corresponding to different annotation levels.

- Beta-lactamase subclass predictions automatically generated for relevant hits.

- Mobility predictions distinguish between intrinsic chromosomal genes and acquired resistance.

Workflow Integration and Visualization

The integration of these tools into a comprehensive whole-genome sequencing pipeline for resistance gene identification follows a logical progression from raw data to biological interpretation. The following diagram illustrates the recommended workflow:

Diagram 1: ARG Detection Workflow in Whole-Genome Sequencing Pipeline (Width: 760px)

Successful implementation of ARG detection pipelines requires both biological and computational resources. The following table outlines essential research reagents and computational components:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | DNA Extraction Kit | Mechanical lysis capability | Maximize DNA yield from diverse bacteria |

| Library Preparation Kit | Illumina-compatible | High-quality sequencing libraries | |

| Quality Control Assays | Qubit, Bioanalyzer | DNA quantity/quality assessment | |

| Computational Resources | Reference Databases | CARD, NCBI, HMD-ARG-DB | ARG sequence reference |

| Alignment Tools | DIAMOND, BLAST | Sequence homology detection | |

| Containers | Docker, Singularity | Environment reproducibility | |

| Analysis Packages | R/Python Stack | ggplot2, scikit-learn | Statistical analysis, visualization |

| Metadata Management | SQLite, PostgreSQL | Sample tracking, result storage |

Discussion and Strategic Recommendations

The selection of appropriate ARG detection tools depends heavily on research objectives, sample types, and desired annotation depth. For clinical surveillance and regulatory applications where standardized reporting is essential, AMRFinderPlus offers robust, curated results integrated with public health resources [29]. For exploratory research in complex environments (e.g., soil, wastewater) where novel resistance determinants may be present, deep learning approaches (DeepARG, HMD-ARG) provide superior detection capabilities for divergent sequences [26] [28].

The emerging trend in ARG detection involves hybrid approaches that combine alignment-based methods with machine learning classifiers. Tools like ProtAlign-ARG represent this next generation, leveraging protein language model embeddings alongside traditional alignment scores to maximize both sensitivity and specificity [31]. Similarly, PLM-ARG utilizes pre-trained protein language models (ESM-1b) with XGBoost classifiers, demonstrating substantial performance improvements over existing methods [32].

For comprehensive resistome characterization, a tiered approach is recommended: initial screening with AMRFinderPlus for well-characterized resistance determinants, followed by deep learning analysis to identify novel or divergent ARGs. This strategy balances the standardization of alignment-based methods with the innovative detection capabilities of machine learning approaches, providing the most complete assessment of resistance potential in genomic and metagenomic datasets.

Future developments in ARG detection will likely focus on explainable artificial intelligence to enhance biological interpretability, incorporation of protein structural features, and real-time monitoring capabilities for clinical applications. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational resources become more accessible, these tools will play an increasingly critical role in global AMR surveillance and mitigation efforts.

Implementing End-to-End WGS Workflows for Precise Resistance Gene Detection

Within the framework of a thesis focused on whole-genome sequencing (WGS) pipelines for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene identification, the initial steps of sample preparation and library construction are critical. The accuracy of downstream bioinformatics analyses, such as those performed by tools like ResFinder and ABRicate, is fundamentally dependent on the quality and completeness of the sequencing data generated upstream [33]. PCR-free library preparation protocols have emerged as a essential methodology for achieving comprehensive genome coverage, minimizing biases such as altered GC-content representation, and providing a more accurate foundation for identifying resistance determinants in pathogens like Klebsiella pneumoniae [6] [33]. This application note details a optimized PCR-free protocol designed to support robust AMR gene detection within a clinical research pipeline.

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies utilizing whole-genome sequencing for AMR identification, highlighting the impact of data quality on analytical outcomes.

Table 1: Performance Metrics in Whole-Genome Sequencing for AMR Identification

| Metric | Findings | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | Average of 326x (Range: 78x-729x) [6] | Based on 40 K. pneumoniae isolates; depth of 100-200x is generally recommended [6]. |

| Genome Coverage | Mean of 93.8% [33] | Achieved from an analysis of 201 K. pneumoniae genomes. |

| AMR Inference Accuracy (Whole-Genome Matching) | 77.3% (95% CI: 59.8–94.8%) for carbapenem resistance [6] | Result achieved within 10 minutes of sequencing. |

| AMR Inference Accuracy (Plasmid Matching) | 85.7% (95% CI: 70.7–100.0%) for carbapenem resistance [6] | Result achieved within 1 hour of sequencing. |

| AMR Gene Detection Accuracy | 54.2% (95% CI: 34.2–74.1%) at 6 hours [6] | Highlights speed and accuracy advantage of inference methods over traditional gene detection. |

| Bacterial Identification Accuracy (Kraken2) | 100% correct identification [33] | Evaluated on 201 K. pneumoniae genomes. |

| Number of AMR Genes Identified (ResFinder) | 23.27 ± 0.56 genes per sample [33] | Note: This count included gene duplicates. |

| Number of AMR Genes Identified (ABRicate) | 15.85 ± 0.39 genes per sample [33] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: PCR-Free Library Construction for Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)

This protocol is adapted for rapid sequencing from low-biomass clinical samples, such as urine, as described in studies of K. pneumoniae [6].

DNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Extract high-molecular-weight (HMW) genomic DNA from bacterial isolates or directly from clinical samples using a kit designed for long-read sequencing (e.g., MagAttract HMW DNA Kit).

- Quantify DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Assess DNA integrity and fragment size via pulse-field gel electrophoresis or the Fragment Analyzer system. A target DNA amount of 400-500 ng is often used as input.

DNA Repair and End-Preparation:

- In a 0.2 mL PCR tube, combine 400 ng of HMW DNA in a 25 µL volume with 2.5 µL of NEBNNext Ultra II End Prep reaction buffer and 1.5 µL of NEBNNext Ultra II End Prep enzyme mix.

- Mix thoroughly by pipetting and incubate at 20°C for 5 minutes, followed by 65°C for 5 minutes in a thermal cycler.

Adapter Ligation:

- To the end-prepped DNA, add 25 µL of Ligation Buffer (LNB), 5 µL of NEBNNext Quick T4 DNA Ligase, and 5 µL of ONT Adapter Mix (e.g., from the SQK-RBK110-96 kit).

- Mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Clean-Up and Elution:

- Add 50 µL of AMPure XP beads to the ligation reaction and mix thoroughly. Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Pellet the beads on a magnetic stand, discard the supernatant, and wash twice with 200 µL of Freshly Prepared 70% Ethanol without disturbing the pellet.

- Air-dry the beads for 30 seconds, then elute the library in 15 µL of Elution Buffer (ELB).

Library Loading and Sequencing:

- Combine 12 µL of the eluted library with 26.5 µL of Sequencing Buffer (SB) and 3.5 µL of Loading Beads (LB).

- Load the entire volume onto a primed R9.4.1 (FLO-MIN106) flow cell.

- Initiate sequencing on a MinION Mk1B device using MinKNOW software with basecalling enabled (e.g., Guppy basecaller in Super High Accuracy mode).

Protocol 2: Bioinformatics Processing for AMR Gene Identification

This downstream protocol is validated for identifying AMR genes from sequenced samples [33].

Quality Control and Trimming:

- Perform quality assessment on raw FASTQ files using NanoPlot v1.40.0.

- Trim and filter reads using NanoFilt v2.8.0, applying a quality threshold (e.g., Q-score > 10) and a minimum length filter (e.g., 200 bp).

De Novo Genome Assembly:

- Assemble the filtered reads into contigs using a assembler such as Flye, Raven, or Unicycler with default parameters.

- Evaluate assembly quality using metrics like N50, number of contigs, and total assembly size.

Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Identification:

- Using ABRicate: Run the tool against the assembled contigs with a curated AMR database (e.g., CARD, ResFinder). Use default parameters (typically 80% identity and 80% coverage) or project-specific thresholds.

- Using ResFinder: Alternatively, use the ResFinder tool with its integrated database, which employs a K-mer-based alignment algorithm. The default parameters are often 90% identity and 60% coverage.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for PCR-free WGS and AMR identification.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and their functions for the successful execution of the PCR-free WGS protocol are listed below.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for PCR-Free WGS Library Construction

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Product |

|---|---|---|

| HMW DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of intact, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA, minimizing shearing. | MagAttract HMW DNA Kit |

| DNA Quantification Kit | Accurate fluorometric quantification of double-stranded DNA concentration. | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay |

| DNA Size/Quality Analyzer | Assessment of DNA fragment size distribution and integrity. | Fragment Analyzer / Pulse Field Gel Electrophoresis |

| Library Prep Kit (PCR-Free) | Contains all enzymes and buffers for end-prep, ligation, and clean-up. | Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK110-96) |

| Sequencing Adapters | Short, double-stranded DNA molecules that facilitate binding of the library to the sequencing matrix. | Provided with ONT Library Prep Kit |

| Magnetic Beads | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) for post-reaction clean-up and size selection. | AMPure XP Beads |

| Flow Cell | The consumable containing nanopores for sequencing. | Oxford Nanopore R9.4.1 (FLO-MIN106) |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Software for basecalling, quality control, assembly, and AMR gene detection. | Guppy, NanoFilt, Flye, ABRicate, ResFinder |

In the context of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) pipelines for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene identification, quality control (QC) and preprocessing are not merely preliminary steps but critical determinants of success. The accuracy with which resistance determinants such as blaKPC, blaNDM, and blaOXA are identified hinges directly on the quality of the underlying sequence data [6] [33]. Poor quality reads can lead to false positives, obscure true variants, and ultimately mischaracterize a pathogen's resistome. This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for QC and preprocessing, designed to ensure that downstream analyses—including alignment, assembly, and AMR gene annotation—are built upon a foundation of high-fidelity data. The principles detailed here are particularly pertinent for sequencing data derived from key AMR pathogens like Klebsiella pneumoniae, where discerning subtle genetic differences can directly impact clinical interpretations [6] [4].

The Quality Control Workflow: A Three-Stage Process