A Practical Framework for Selecting Molecular Dynamics Force Fields in Computational Drug Discovery

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select and validate molecular mechanics force fields.

A Practical Framework for Selecting Molecular Dynamics Force Fields in Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select and validate molecular mechanics force fields. It covers foundational concepts of force field composition and types, methodological approaches for application-specific parameterization, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing simulations, and rigorous techniques for benchmarking performance against experimental and quantum mechanical data. The article synthesizes traditional practices with emerging data-driven and machine learning methods to enhance accuracy and efficiency in molecular dynamics studies.

Understanding Force Field Fundamentals: Components, Types, and Physical Principles

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a force field is a computational model that describes the potential energy of a system of atoms as a function of their nuclear coordinates [1] [2]. It is the fundamental engine that calculates the forces acting upon every particle, thereby driving their motion and enabling the simulation of complex molecular phenomena [3] [2]. For researchers in drug development, the selection of an appropriate force field is paramount, as it directly determines the accuracy and reliability of simulations predicting protein-ligand binding, conformational changes, and other critical processes [4].

The total potential energy ((E{total})) in a typical molecular mechanics force field is almost universally decomposed into bonded and non-bonded contributions [1] [3] [5]: (E{total} = E{bonded} + E{non-bonded})

This application note provides a detailed deconstruction of these energy terms, their functional forms, and their parameterization, serving as a foundation for making informed force field selections in molecular research.

Hierarchical Decomposition of the Force Field Energy Function

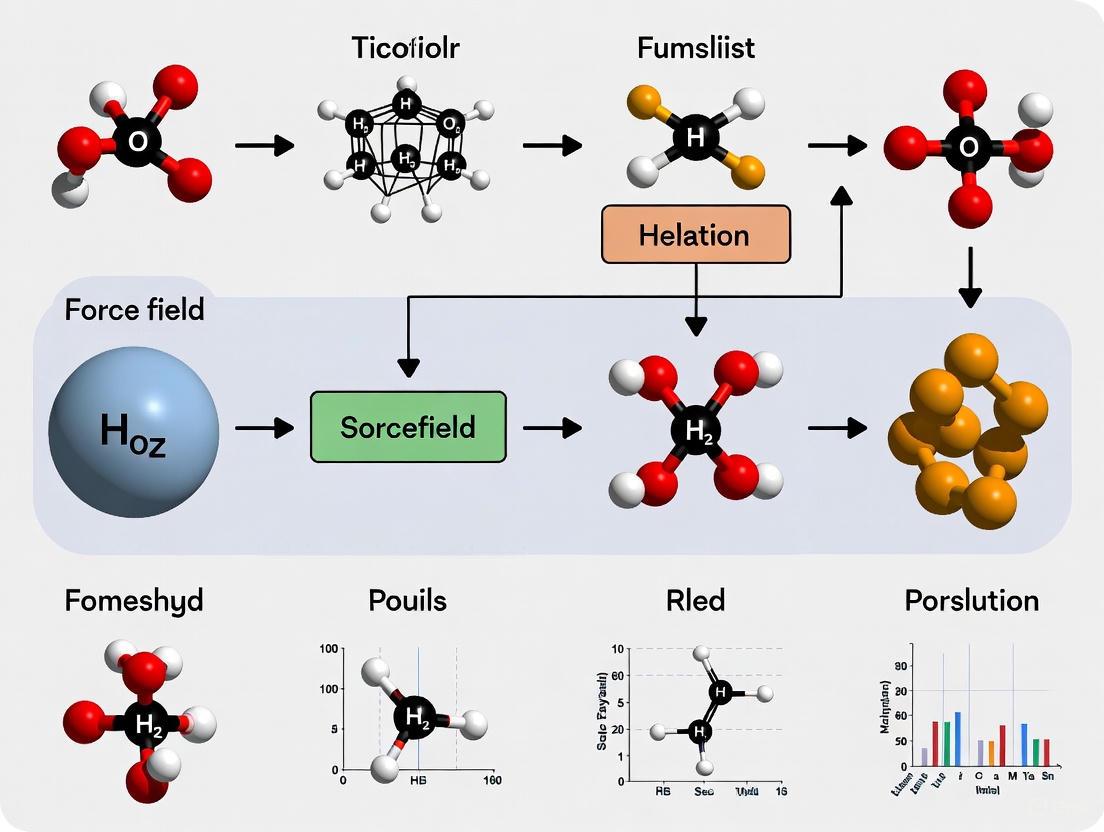

The following diagram illustrates the standard hierarchical decomposition of the total potential energy in a molecular mechanics force field.

Detailed Analysis of Bonded Energy Terms

Bonded energy terms describe the energy associated with the covalent connectivity within molecules. These terms constrain the internal geometry and are crucial for maintaining molecular structure during simulations [1] [3].

Table 1: Primary Bonded Interactions in Molecular Force Fields

| Energy Term | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $V{bond} = k{r}(r - r_0)^2$ [3] | $k{r}$: Force constant$r0$: Equilibrium bond length | Energetic cost of stretching or compressing a covalent bond between two atoms. |

| Angle Bending | $V{angle} = k{\theta}(\theta - \theta_0)^2$ [3] | $k{\theta}$: Force constant$\theta0$: Equilibrium angle | Energetic cost of bending the angle between three covalently bonded atoms. |

| Dihedral Torsion | $V{dihed} = k{\phi}[1 + cos(n\phi - \delta)]$ [3] | $k_{\phi}$: Force constant$n$: Periodicity$\delta$: Phase angle | Energy associated with rotation around a central bond, defined for four sequentially bonded atoms. |

| Improper Torsion | $V{improper} = k{\psi}(\psi - \psi_0)^2$ [3] | $k{\psi}$: Force constant$\psi0$: Equilibrium angle | Used to enforce planarity (e.g., in aromatic rings or conjugated systems) around a central atom. |

Advanced Bonded Formulations

While the harmonic potentials in Table 1 are standard in Class 1 force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) [3], more advanced formulations exist:

- Class 2 Force Fields (e.g., MMFF94, UFF) introduce anharmonicity using cubic and/or quartic terms for bonds and angles, and include cross-terms that describe coupling between adjacent internal coordinates like bonds and angles [3].

- For a more realistic description that allows for bond breaking, the Morse potential can be used instead of the harmonic potential [1] [6].

Detailed Analysis of Non-Bonded Energy Terms

Non-bonded energy terms describe interactions between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds, as well as interactions between different molecules. These terms are computationally intensive and dominate the calculation time in MD simulations [1] [7].

Table 2: Primary Non-Bonded Interactions in Molecular Force Fields

| Energy Term | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| van der Waals(Lennard-Jones) | $V_{LJ}(r) = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right]$ [3] [7] | $\epsilon$: Well depth$\sigma$: Van der Waals radius | Describes Pauli repulsion (r⁻¹² term) and attractive dispersion forces (r⁻⁶ term). |

| van der Waals(Buckingham) | $V_{B}(r) = A\exp(-Br) - \frac{C}{r^6}$ [7] [6] | A, B: Repulsion parametersC: Dispersion parameter | Uses an exponential function for repulsion, considered more realistic but computationally more expensive. |

| Electrostatics(Coulomb) | $V{Elec} = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0\epsilonr r{ij}}$ [1] [3] | $qi, qj$: Atomic partial charges$\epsilon_r$: Dielectric constant | Describes the interaction between atomic partial charges. |

Combining Rules and Cut-off Methods

A critical aspect of non-bonded interactions is the treatment of interactions between different atom types.

- Combining Rules: To avoid parameterizing every possible pair of atom types, combining rules are used. Common rules include the Lorentz-Berthelot rule ($\sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2}$; $\epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \epsilon{jj}}$), used in CHARMM and AMBER, and the geometric mean rule ($\sigma{ij} = \sqrt{\sigma{ii}\sigma{jj}}$; $\epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii}\epsilon{jj}}$), used in OPLS [3] [7].

- Long-Range Electrostatics: The Coulomb potential is long-ranged ($r^{-1}$). Plain truncation at a cut-off distance creates artifacts, so methods like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) or Reaction Field corrections are essential for accurate simulations [7].

The Challenge of Electronic Polarizability

A significant limitation of conventional Class 1 force fields is the use of fixed atomic charges, which do not account for electronic polarization—the redistribution of electron density in response to a changing electrostatic environment [3]. To address this, polarizable force fields (Class 3) have been developed, which employ several advanced models:

- Drude Oscillators: Massless charged particles attached to atoms via harmonic springs (e.g., CHARMM-Drude, OPLS5) [3].

- Inducible Point Dipoles: Atoms or sites possess dipoles that respond to the local electric field (e.g., AMOEBA) [3].

- Fluctuating Charges: Polarization is modeled as a charge transfer process between atoms [3].

Parameterization of Force Fields

The accuracy of a force field is determined by both its functional form and the numerical parameters assigned to each atom type and interaction [1]. The process of determining these parameters is known as parameterization or parametrization.

Parameterization strategies leverage data from multiple sources to achieve a balanced and transferable model.

- Quantum Mechanical (QM) Calculations: Used to derive intramolecular parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and atomic charges from high-level ab initio or Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on small molecule fragments [1] [4]. For example, the ByteFF force field was trained on a dataset of 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries and 3.2 million torsion profiles generated with DFT [4].

- Experimental Data: Macroscopic experimental properties—such as density, enthalpy of vaporization, and crystal lattice parameters—are used to refine intermolecular parameters (van der Waals) to ensure the force field reproduces bulk material behavior [1] [8].

- Atoms-in-Molecules (AIM) Methods: Emerging approaches partition the electron density from QM calculations to derive non-bonded parameters directly. For instance, the Minimal Basis Iterative Stockholder (MBIS) scheme has been shown to accurately reproduce electrostatic and dispersion interactions in proteins [9].

Modern Data-Driven Workflows

Recent advances leverage machine learning to create highly accurate and transferable force fields. The following diagram outlines a modern, data-driven parameterization workflow as used in the development of ByteFF [4].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Force Field Application and Development

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GAFF/GAFF2 [4] | Force Field | General Amber Force Field; a widely used transferable force field for small organic molecules. |

| OpenFF [4] | Force Field & Toolkit | An open-source force field initiative that uses SMIRKS-based atom typing for highly customizable parameterization. |

| AMBER [6] [4] | Force Field | A family of force fields (e.g., ff19SB) specially optimized for proteins and nucleic acids. |

| CHARMM [3] [6] | Force Field | A family of force fields (including polarizable Drude-2013) for biomolecules and lipids. |

| OPLS [3] [6] [4] | Force Field | Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations; widely used for organic liquids and biomolecules. |

| GROMACS [3] [7] | MD Software | A high-performance MD simulation package supporting numerous force fields and advanced algorithms. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [4] [8] | ML Model | Used in modern workflows (e.g., Espaloma, ByteFF) to predict force field parameters directly from molecular structures. |

| Density-Based Energy Decomposition [10] | QM Method | A method to cleanly separate QM interaction energies into force-field-like components for parameterization. |

| Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) [8] | ML Method | An algorithm that enables training of ML potentials directly on experimental data without backpropagating through entire simulations. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Deriving Non-Bonded Parameters via Atoms-in-Molecules (AIM) Analysis

This protocol is adapted from methods used to derive non-bonded force field parameters for proteins from partitioned electron density [9].

System Preparation and QM Calculation:

- Select representative molecular clusters or dimer pairs that capture the key non-covalent interactions of interest (e.g., charged, aromatic, and hydrophilic side-chain interactions for proteins).

- Generate multiple configurations for these clusters to sample the potential energy surface.

- Perform ab initio calculations (e.g., ALMO-EDA at the wB97XV/def2TZVPD level) to obtain reference interaction energies and electron densities.

Energy Decomposition and Parameter Fitting:

- Perform a density-based energy decomposition analysis (e.g., using the Minimal Basis Iterative Stockholder, MBIS, method) on the QM electron density.

- Extract atomic charges ((q_i)) by fitting the electrostatic potential (ESP) derived from the partitioned density.

- Derive dispersion coefficients ((C_6)) directly from the MBIS partitioning scheme.

Validation Against First-Principles Data:

- Compute electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energies using the newly derived AIM parameters.

- Validate the force field by comparing these energies to the original first-principles interaction energies (e.g., ALMO-EDA). Target a mean absolute error for electrostatic interactions of 4-7 kJ/mol [9].

Protocol: Fused Data Training for a Machine Learning Potential

This protocol describes a hybrid approach that leverages both QM and experimental data to train a highly accurate ML potential, as demonstrated for titanium [8].

DFT Pre-Training (Bottom-Up):

- DFT Database Generation: Create a diverse dataset of atomic configurations (e.g., equilibrated, strained, randomly perturbed, high-temperature) for the material/system of interest. Calculate energies, forces, and virial stress using DFT.

- NN Potential Training: Train a Graph Neural Network (GNN) potential on this DFT database using a standard regression loss function to minimize errors in energy, force, and stress predictions.

Experimental Data Refinement (Top-Down):

- Target Selection: Identify key experimentally measurable properties (e.g., temperature-dependent elastic constants and lattice parameters for a metal).

- Differentiable Training: Employ the DiffTRe method to refine the pre-trained GNN potential. Run short simulations with the current model, compute the target properties, and calculate the loss against experimental values. Use DiffTRe to efficiently compute gradients and update the model parameters without backpropagating through the entire simulation trajectory.

Iterative Fused Training:

- Alternate between the DFT trainer and the Experimental (EXP) trainer for multiple epochs. This fused approach concurrently satisfies quantum-level accuracy and reproduces macroscopic experimental observables [8].

- Use early stopping on a validation set to select the final model and prevent overfitting.

The decomposition of the force field energy function into bonded and non-bonded terms provides a powerful and computationally efficient framework for molecular simulation. The choice of a force field is a critical step that dictates the balance between computational cost and physical accuracy. Researchers must consider the specific requirements of their system—such as the need for polarizability (Class 3 FFs), capacity for bond breaking (reactive FFs), or coverage of expansive chemical space (ML-based FFs). Modern trends are shifting towards data-driven, machine-learned parameterizations that offer improved accuracy and transferability by leveraging large-scale quantum chemical data, often in combination with experimental observables. By understanding the fundamental components, parameterization strategies, and available tools detailed in this note, scientists can make more informed decisions in selecting and applying force fields for drug discovery and materials research.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a force field is a computational model that defines the potential energy of a system of atoms as a function of their relative positions [1]. It is the foundational component that determines the accuracy and reliability of simulations, enabling the study of biological processes such as protein folding, ligand-protein binding, and the behavior of complex materials [11] [12]. The total potential energy in an additive force field is typically given by the sum of bonded and non-bonded interactions: ( E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} ) [1].

The bonded interactions (( E{\text{bonded}} )) include terms for bonds, angles, and torsions (dihedrals), which collectively maintain the internal structural integrity of molecules. The non-bonded interactions (( E{\text{nonbonded}} )) describe van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions between atoms that are not directly connected, governing intermolecular behavior and long-range forces [1] [13]. The functional forms of these potentials are designed for computational efficiency, allowing for the simulation of large systems over biologically relevant timescales [13].

This application note details the core potential energy terms, their mathematical foundations, and protocols for their parameterization, providing a guide for researchers in computational chemistry and drug development.

Table 1: Core Components of a Classical Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Energy Component | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Primary Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{b}}{2}(l - l_0)^2 ) [14] | Force constant (( kb )), equilibrium distance (( l0 )) [1] | Maintains covalent bond lengths |

| Angle Bending | ( E{\text{angle}} = \frac{k{\theta}}{2}(\theta - \theta_0)^2 ) [14] | Force constant (( k{\theta} )), equilibrium angle (( \theta0 )) [1] | Maintains bond angles |

| Torsional Dihedral | ( E{\text{dihedral}} = k\phi (1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)) ) [13] | Barrier height (( k_\phi )), periodicity (( n )), phase (( \delta )) [13] | Governs rotation around bonds, conformational sampling |

| Electrostatic | ( E{\text{elec}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{\epsilon r_{ij}} ) [1] [14] | Atomic partial charges (( qi, qj )), distance (( r_{ij} )) [1] | Describes long-range attractive/repulsive forces between charges |

| van der Waals | ( E_{\text{vdW}} = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^6 \right] ) [1] [13] | Well depth (( \epsilon )), van der Waals radius (( \sigma )) [13] | Models short-range repulsion and dispersion |

Bonded Interaction Terms

Bond Stretching

The bond stretching term describes the energy cost associated with the elongation or compression of a covalent bond between two atoms. It is most commonly represented by a harmonic potential, which provides a good approximation near the equilibrium bond length [1]. The harmonic potential is defined as:

( E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{b}}{2}(l - l_0)^2 ) [14]

where ( kb ) is the force constant reflecting the bond's stiffness, ( l ) is the instantaneous bond length, and ( l0 ) is the equilibrium bond length [1]. While adequate for most simulations near equilibrium, the harmonic potential does not allow for bond breaking. For higher stretching or reactive systems, more complex potentials like the Morse potential can be employed [1].

Angle Bending

The angle bending term models the energy required to deform the angle between three consecutively bonded atoms from its equilibrium value. This term is crucial for maintaining the correct local geometry and hybridization states of atoms. Like the bond term, it is typically modeled with a harmonic potential:

( E{\text{angle}} = \frac{k{\theta}}{2}(\theta - \theta_0)^2 ) [14]

Here, ( k\theta ) is the angular force constant, ( \theta ) is the instantaneous bond angle, and ( \theta0 ) is the equilibrium bond angle [1]. The force constants for angle bending are generally about five times smaller than those for bond stretching, reflecting the greater ease of deforming angles compared to bonds [13].

Torsional Dihedral

The torsional dihedral potential describes the energy change associated with rotation around a central bond connecting four atoms. This term is critical for determining the conformational preferences of molecules, such as the transitions between gauche and anti conformers in alkanes or the torsional strains in ring systems. The potential is periodic and is commonly expressed as a cosine series:

( E{\text{dihedral}} = k\phi (1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)) ) [13]

In this function, ( k_\phi ) is the torsional barrier height, ( n ) is the periodicity (the number of energy minima or maxima in a 360° rotation), ( \phi ) is the torsional angle, and ( \delta ) is the phase angle that shifts the location of the minima [13]. Multiple such terms with different periodicities are often summed to create a complex torsional profile [13]. For example, a combination of n=2 and n=3 dihedrals is used to reproduce the energy differences in ethylene glycol [13].

Improper Torsions

Improper torsions are used to enforce planarity in specific molecular structures, such as aromatic rings or conjugated systems, and to maintain chirality around tetrahedral centers. Unlike proper dihedrals, they are not defined by a sequence of four bonded atoms but are often applied to a central atom and three atoms bonded to it. The potential is usually harmonic:

( V{\text{Improper}} = k\phi(\phi - \phi_0)^2 ) [13]

where ( \phi ) is the improper dihedral angle and ( \phi_0 ) is its equilibrium value, typically 0° for enforcing planarity [13].

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for parameterizing bonded force field terms (bonds, angles, torsions) using data from quantum mechanical calculations and experimental validation.

Non-Bonded Interaction Terms

Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic interactions are long-range forces between atoms with partial or full electrical charges. They play a dominant role in stabilizing protein-ligand complexes, protein folding, and solvation phenomena. The interaction is modeled using Coulomb's law:

( E{\text{Coulomb}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{\epsilon r_{ij}} ) [1] [14]

Here, ( qi ) and ( qj ) are the partial atomic charges, ( \epsilon0 ) is the permittivity of free space, ( \epsilon ) is the relative dielectric constant of the medium, and ( r{ij} ) is the distance between the atoms [1] [14]. The assignment of atomic charges is a critical step in force field development, often done using heuristic approaches or by fitting to the quantum mechanical electrostatic potential (ESP) using methods like RESP or ChelpG [15].

van der Waals Interactions

van der Waals (vdW) interactions encompass short-range attractive (dispersion) and repulsive (Pauli exclusion) forces. The most common model for these interactions is the Lennard-Jones (L-J) 12-6 potential:

( E_{\text{vdW}} = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^6 \right] ) [1] [13]

The ( r^{-12} ) term describes the strong repulsion at short distances due to overlapping electron orbitals, while the ( r^{-6} ) term models the attractive dispersion forces [13]. The parameters are ( \sigma ), the finite distance at which the inter-particle potential is zero, and ( \epsilon ), the depth of the potential well [13]. To compute interactions between different atom types, combining rules are used. The most common is the Lorentz-Berthelot rule: ( \sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2} ) and ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \epsilon{jj}} ), employed in force fields like CHARMM and AMBER [13].

An alternative to the L-J potential is the Buckingham potential, which replaces the repulsive ( r^{-12} ) term with an exponential function: ( V_{B}(r) = A \exp(-Br) - \frac{C}{r^{6}} ) [13]. This provides a more realistic description of electron density but is computationally more expensive and can exhibit a "Buckingham catastrophe" (energy goes to -∞) at very short distances [13].

Table 2: Common Combining Rules for van der Waals Interactions in Different Force Fields

| Force Field | Combining Rule (Geometric) | Combining Rule (Lorentz-Berthelot) |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | - | ( \sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \epsilon{jj}} ) [13] |

| CHARMM | - | ( \sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \epsilon{jj}} ) [13] |

| GROMOS | ( C12{ij} = \sqrt{C12{ii} \cdot C12{jj}} ), ( C6{ij} = \sqrt{C6{ii} \cdot C6{jj}} ) [13] | - |

| OPLS | ( \sigma{ij} = \sqrt{\sigma{ii} \cdot \sigma{jj}} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \cdot \epsilon{jj}} ) [13] | - |

Parameterization Methodologies and Protocols

Force field parameterization is the process of determining the numerical values for the functional form's constants (e.g., ( kb ), ( l0 ), ( q_i ), ( \epsilon ), ( \sigma )). This process is crucial for the accuracy and transferability of the force field.

Protocol 1: Parameterization of Bonded Terms from Quantum Chemical Data

This protocol outlines the steps for deriving bonded parameters (bonds, angles, torsions) using quantum mechanical (QM) calculations, as implemented in tools like JOYCE and other modern workflows [4] [16].

- System Preparation and QM Calculation Setup: Select a representative set of molecules or molecular fragments that cover the chemical space of interest. For instance, the ByteFF force field was trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragments generated from the ChEMBL and ZINC20 databases to ensure diversity [4].

- Geometry Optimization and Frequency Calculation: Perform QM geometry optimizations (e.g., at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level of theory) to find the equilibrium structure [4]. Subsequently, compute the Hessian matrix (second derivatives of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates) via a frequency calculation. The eigenvalues of the Hessian are directly related to the vibrational frequencies used to fit the force constants (( kb ), ( k\theta )) [4] [16].

- Torsional Energy Scans: For each rotatable bond of interest, perform a relaxed potential energy surface scan by systematically rotating the dihedral angle in fixed increments (e.g., every 15° or 30°) and computing the single-point energy at each step [4] [15]. This generates a torsional profile that will be fitted using the dihedral potential function.

- Force Constant Parameter Fitting: The equilibrium values (( l0 ), ( \theta0 )) are taken directly from the optimized geometry. The force constants are then optimized by minimizing the difference between the QM-calculated vibrational frequencies and the frequencies predicted by the force field, and between the QM and force field torsional energy profiles [4] [16].

- Validation: Validate the parameters by comparing the resulting molecular structures and conformational energies from MD simulations against higher-level QM calculations or available experimental data, such as crystal structures or spectroscopic data [16].

Protocol 2: Optimization of Non-Bonded Terms Using Genetic Algorithms

This protocol describes an automated approach for optimizing van der Waals parameters using Genetic Algorithms (GAs) to reproduce experimental condensed-phase properties [15].

- Define the Fitness Function: The fitness function is a metric to be minimized. It typically includes the sum of squared differences between simulated and experimental properties, such as density (( \rho )) and enthalpy of vaporization (( \Delta H{vap} )): ( Fitness = w1(\rho{sim} - \rho{exp})^2 + w2(\Delta H{vap,sim} - \Delta H_{vap,exp})^2 ), where ( w ) are weighting factors [15].

- Initialize the Population: An initial population of "chromosomes" is generated, where each chromosome is a vector containing a candidate set of vdW parameters (( \epsilon ), ( \sigma )) for the relevant atom types [15].

- Evaluation and Selection:

- Run MD Simulations: For each candidate parameter set, run a short MD simulation (e.g., in the NPT ensemble) of the liquid system.

- Calculate Fitness: Compute the average density and enthalpy of vaporization from the simulation and evaluate the fitness function.

- Selection: Select the parameter sets (chromosomes) with the best fitness scores to "reproduce" and form the next generation [15].

- Genetic Operations - Crossover and Mutation:

- Crossover: Combine parts of two parent chromosomes to create offspring with mixed parameters.

- Mutation: Introduce small random changes to the parameters in the offspring to maintain genetic diversity and explore new regions of the parameter space [15].

- Iteration and Convergence: Repeat steps 3 and 4 over many generations. The algorithm converges when the fitness score no longer improves significantly or a maximum number of generations is reached. The best-performing parameter set is selected for final validation [15].

Diagram 2: A workflow for optimizing non-bonded force field parameters, specifically van der Waals terms, using a Genetic Algorithm (GA) to fit experimental liquid properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF/GAFF2 [4] [17] | General Force Field | Provides parameters for a wide range of organic molecules. | Drug-like molecule simulation; often a starting point for parameterization. |

| CHARMM36 [11] [17] | Biomolecular Force Field | Optimized for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates. | High-accuracy simulations of biomolecular systems and membranes [17]. |

| AMBER [11] [4] | Biomolecular Force Field | Widely used for proteins and nucleic acids, particularly in protein-ligand interactions. | Protein folding, drug design, and nucleic acid simulations [11]. |

| OpenFF (SMIRNOFF) [12] [4] | Force Field Format & Initiative | Uses direct chemical perception via SMIRKS patterns for parameter assignment. | Creates highly specific and transferable force fields; enables automated typing. |

| Espaloma/ByteFF [4] | Machine-Learned Force Field | Graph Neural Network (GNN) that predicts MM parameters for any molecule. | High-throughput parameterization across expansive chemical space [4]. |

| ForceBalance [12] | Parameterization Tool | Automates force field optimization against experimental and QM data. | Systematic refinement of force field parameters using a wide array of target data. |

| JOYCE [16] | Parameterization Software | Protocol for parameterizing accurate quantum-mechanically derived force-fields (QMD-FFs). | Creating specific, high-accuracy intramolecular force fields for diverse molecules. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [15] | Optimization Algorithm | Evolutionary algorithm for optimizing parameters like vdW terms against property data. | Efficiently searching high-dimensional parameter spaces to fit experimental data [15]. |

The core potential energy terms—bonds, angles, torsions, and electrostatics—form the mathematical backbone of molecular mechanics force fields. Accurate parameterization of these terms is non-negotiable for producing reliable simulation results. Traditional methods rely heavily on fitting to quantum chemical data and experimental observables, but the field is rapidly evolving.

Machine learning (ML) is now revolutionizing force field development. Approaches like the Open Force Field Initiative's SMIRNOFF format aim to replace human-defined atom types with statistically rigorous, automated approaches [12]. Furthermore, end-to-end ML models, such as Espaloma and ByteFF, use graph neural networks to predict force field parameters directly from chemical structure, enabling rapid and accurate coverage of vast chemical spaces [4]. These advances, combined with robust parameterization protocols, are paving the way for next-generation force fields that offer unprecedented accuracy and scope for molecular dynamics research in drug discovery and materials science.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide invaluable insights into the structure, dynamics, and function of biomolecular systems. The accuracy of these simulations critically depends on the force field—a set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system based on the relative positions of atoms and their interactions [11]. Force fields define the interaction potentials for bond stretching, angle bending, torsional rotations, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic forces), essentially governing the behavior of the simulated system [11].

The selection of an appropriate force field is a foundational step in MD research, as it directly influences the reliability and interpretability of simulation results [11]. Researchers face a choice between three fundamental approaches that offer different balances between computational efficiency and atomic detail: all-atom, united-atom, and coarse-grained methods. This guide provides a structured overview of these approaches, their applications, and protocols for their implementation, serving as a decision-making framework for researchers across various domains of computational molecular science.

Classification of Force Field Approaches

All-Atom Force Fields

All-atom force fields represent every atom in the system explicitly, including all hydrogen atoms. This approach provides the highest level of detail and is crucial for studying phenomena where precise atomic interactions are paramount [18].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major All-Atom Force Fields

| Force Field | Strengths | Primary Applications | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Accurate for proteins/nucleic acids; refined torsional parameters [19] [11] | Protein folding, protein-ligand interactions, DNA/RNA structure [11] | ff19SB [19], ff99, ff14SB [19] |

| CHARMM | Detailed parameters for diverse biomolecules; good with lipids [11] | Protein-lipid systems, membrane proteins, protein-ligand binding [11] | CHARMM22, CHARMM27, CHARMM36 [19] [20] |

| OPLS | Optimized for condensed phases; accurate thermodynamics [11] | Drug design, small molecule-biomolecule interactions [11] | OPLS-AA, OPLS-AA/M [20] |

United-Atom Force Fields

United-atom force fields represent non-polar carbons and their bonded hydrogens as a single interaction center, significantly reducing the number of particles in the system [18]. This approach emerged as a compromise to accelerate large-scale simulations while maintaining reasonable chemical accuracy [18].

The GROMOS force field represents a prominent united-atom approach, where aliphatic hydrogens are combined with their parent carbon atoms, but polar hydrogens remain explicit [20] [18]. This design helps mitigate limitations in hydrogen bonding and π-stacking interactions that would occur if all hydrogens were unified [18]. United-atom force fields can adequately represent molecular vibrations and bulk properties of small molecules while offering significant computational advantages over all-atom methods [18].

Coarse-Grained Force Fields

Coarse-grained (CG) force fields group multiple atoms into a single "bead" or interaction center, dramatically reducing system complexity and enabling the simulation of larger systems over longer timescales [21]. The level of coarse-graining (number of atoms per bead) depends on the system size and research question [21].

Table 2: Popular Coarse-Grained Force Fields and Their Characteristics

| Force Field | Mapping Resolution | Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MARTINI | 4-5 heavy atoms per bead [21] | Extensive parameter library; good balance of speed/accuracy [19] [21] | Biomolecular complexes, membranes, polymers [19] |

| SIRAH | Hybrid resolution [19] [21] | Different resolution for backbone/side chains [21] | Protein-DNA complexes, solution studies [19] |

| ELBA | Variable based on electrostatics [21] | Combines electrostatic/van der Waals interactions [21] | Charged biomolecules, electrostatic assemblies [21] |

Coarse-grained force fields must balance accuracy with computational efficiency, typically featuring fewer parameters than atomistic force fields [21]. However, they may lack certain atomistic details, such as precise secondary structure recognition, due to the inherent simplifications [19]. Recent developments, such as carefully scaling protein-water interactions in Martini, have improved their accuracy for studying intrinsically disordered proteins [19].

Diagram 1: Force field classification and application space. The diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between the three main force field approaches and their typical biomolecular applications.

Force Field Selection Criteria

Molecular System Considerations

Choosing the appropriate force field requires careful consideration of the biomolecular system under investigation [11]:

Proteins and Peptides: AMBER and CHARMM provide excellent coverage with specialized parameters for proteins [11]. AMBER force fields like ff19SB have demonstrated strong performance for both folded and disordered proteins [19].

Nucleic Acids: AMBER offers refined parameters for DNA and RNA simulations, while CHARMM also provides comprehensive nucleic acid parameters [11].

Lipids and Membranes: CHARMM includes detailed parameters for various lipid species, making it well-suited for membrane simulations [11]. The GROMOS united-atom force field also performs well for large-scale membrane systems [11].

Complex Systems and Drug Design: OPLS excels in modeling small molecule interactions and is particularly valuable in drug design contexts [11]. AMBER also provides precise parameters for protein-ligand binding studies [11].

Computational Efficiency vs. Accuracy Trade-offs

The choice between resolution levels involves balancing computational cost with required detail [21] [11]:

- All-atom: Highest accuracy but greatest computational expense; suitable for detailed mechanistic studies [11]

- United-atom: Moderate efficiency gain while maintaining chemical specificity; suitable for larger systems [18]

- Coarse-grained: Maximum efficiency enabling microsecond-millisecond simulations; suitable for large-scale conformational changes [21]

Target Properties and Validation

Consider which properties are most important for your research question: structural accuracy, thermodynamic properties, dynamics, or specific interactions [11]. Consult literature using similar systems and validate against available experimental data where possible [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: All-Atom Simulation with AMBER ff19SB

This protocol employs the state-of-the-art AMBER ff19SB force field with OPC water model, which has demonstrated strong performance for both folded and disordered proteins [19].

System Setup:

- Obtain initial protein structure from PDB or generate using modeling software

- Process structure using

pdb4amberto standardize residues and atoms - Parameterize using

tleapwith ff19SB force field and OPC water model - Solvate in truncated octahedral water box with 10-12 Å buffer

- Add ions to neutralize system and achieve physiological concentration

Energy Minimization:

- Perform 5000 steps of steepest descent minimization with protein heavy atoms restrained

- Execute 5000 steps of conjugate gradient minimization without restraints

Equilibration:

- Heat system from 0K to 300K over 100ps with backbone restraints

- Density equilibration for 200ps with semi-isotropic pressure coupling

- Unrestrained equilibration for 200ps to remove any residual strain

Production Simulation:

- Run production MD with 2-4fs timestep using hydrogen mass repartitioning

- Maintain temperature at 300K using Langevin dynamics

- Regulate pressure using Monte Carlo barostat

- Execute multiple independent replicates for enhanced sampling [19]

Protocol 2: Coarse-Grained Simulation with Martini 3

This protocol outlines the setup of coarse-grained simulations using Martini 3 in GROMACS, with corrections for protein-water interactions to improve accuracy for intrinsically disordered proteins [19] [21].

Model Conversion:

- Obtain all-atom structure (e.g., from PDB database) [21]

- Convert to Martini representation using

martinize2script - Select appropriate bead types and mapping scheme

- Apply elastic network model if maintaining tertiary structure is desired

System Setup:

- Construct simulation box with sufficient padding (≥1.5nm)

- Solvate with Martini water beads

- Add ions to neutralize system and achieve target concentration

Energy Minimization:

- Execute energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm

- Continue until maximum force <1000 kJ/mol/nm

Equilibration:

- Perform 1ns equilibration with protein position restraints

- Run 10-100ns unrestrained equilibration to relax interactions

Production Simulation:

- Execute production run with 20-30fs timestep

- Maintain temperature using velocity rescale or Nosé-Hoover thermostat

- Regulate pressure using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Run for timescales typically 10-100× longer than equivalent all-atom simulations

Analysis:

- Calculate radius of gyration to monitor compactness [21]

- Determine root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for structural stability [21]

- Compute root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) for residue mobility [21]

- Perform principal component analysis for large-scale motions [21]

Diagram 2: Comparative workflow for all-atom and coarse-grained simulation protocols. The diagram outlines the key stages in setting up and running MD simulations using different resolution approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Software and Force Fields

Table 3: Key Research Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Applicable Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS [19] [21], AMBER [19] | MD engine for simulation execution | All-Atom, United-Atom, Coarse-Grained |

| All-Atom Force Fields | AMBER ff19SB [19], CHARMM36 [19] | Protein/nucleic acid parameters | All-Atom |

| Coarse-Grained Force Fields | Martini 3 [19] [21], SIRAH [19] [21] | Simplified representations | Coarse-Grained |

| Topology Preparation | pdb4amber, martinize2 | System setup and parameterization | All-Atom, Coarse-Grained |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS analysis suite, VMD, MDAnalysis | Trajectory analysis and visualization | All-Atom, United-Atom, Coarse-Grained |

Specialized Methodologies

Advanced Sampling Techniques: For enhanced conformational sampling of biomolecules, particularly relevant for all-atom simulations of complex systems:

- Replica Exchange MD (REMD): Parallel simulations at different temperatures [19]

- Metadynamics: History-dependent bias potential to explore free energy surfaces

- Umbrella Sampling: Targeted sampling along reaction coordinates

QM/MM Methods: Hybrid approaches that combine quantum mechanical detail with molecular mechanics efficiency, useful for studying chemical reactions in biomolecular environments [11] [22].

Disulfide Bond Handling: Specialized protocols for modeling disulfide bonds, including dynamic formation and breaking using distance restraints, particularly relevant for studying proteins like amyloid-β with cysteine mutations [19].

The selection of appropriate force field resolution—all-atom, united-atom, or coarse-grained—represents a fundamental decision point in molecular dynamics research that directly influences the scientific questions that can be addressed. All-atom force fields provide the highest resolution for detailed mechanistic studies, united-atom approaches offer a balance of efficiency and chemical specificity, while coarse-grained methods enable the investigation of large-scale biomolecular processes over extended timescales.

Recent advances in force field development, including the AMBER ff19SB all-atom force field and Martini 3 coarse-grained approach with optimized protein-water interactions, have significantly improved the accuracy of biomolecular simulations [19]. By following structured protocols and selecting force fields matched to their specific research objectives, scientists can leverage MD simulations as a powerful tool for elucidating biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function across diverse research domains.

Force fields are mathematical models that describe the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of the positions of its atoms. They are foundational to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, which analyze the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [11] [23]. The accuracy and reliability of these simulations are critically dependent on the quality of the force field parameters [4] [24]. Parameterization is the process of determining the numerical values within a force field's functions, a procedure that must balance two primary sources of information: high-level Quantum Mechanics (QM) calculations and empirical Experimental Data [25] [26]. This balance is crucial for creating transferable force fields that are accurate across the expansive chemical space explored in modern drug discovery [4]. A force field that over-relies on QM might excel at predicting intramolecular energies yet fail to reproduce macroscopic liquid properties, while one tuned only to a narrow set of experimental data may lack transferability to novel compounds [25].

The total potential energy in a typical molecular mechanics force field is a sum of several components, each with associated parameters that must be determined [4] [11].

Table 1: Key Components of a Classical Force Field and Their Typical Parameterization Sources

| Energy Component | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Primary Parameterization Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $E{bond} = \sum{bonds} kr (r - r0)^2$ | Force constant ((kr)), Equilibrium distance ((r0)) | QM: Optimized geometries & Hessian matrices [4] |

| Angle Bending | $E{angle} = \sum{angles} k{\theta} (\theta - \theta0)^2$ | Force constant ((k{\theta})), Equilibrium angle ((\theta0)) | QM: Optimized geometries & Hessian matrices [4] |

| Torsional Rotation | $E{dihedral} = \sum{dihedrals} \frac{V_n}{2} (1 + cos(n\phi - \gamma))$ | Barrier height ((V_n)), Periodicity ((n)), Phase angle ((\gamma)) | QM: Torsional energy scans [4] |

| Van der Waals | $E{vdW} = \sum{i |

Well depth ((\epsilon)), Atomic radius ((\sigma)) | QM (dimer interactions) & Experimental data (densities, enthalpies) [25] |

| Electrostatics | $E{elec} = \sum{i |

Partial atomic charges ((q)) | QM: Electronic structure calculations [11] |

The parameterization strategy differs significantly between bonded terms (bonds, angles, torsions) and non-bonded terms (van der Waals, electrostatics). Bonded parameters are predominantly derived from QM data because quantum calculations accurately describe the electronic structure that defines molecular geometry [4] [26]. For instance, the ByteFF force field was trained on a massive QM dataset containing 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries and 3.2 million torsion profiles [4]. In contrast, non-bonded parameters have historically relied on a blend of QM and experimental data to ensure the force field reproduces macroscopic thermodynamic properties, a process that often involves empirical optimization to achieve error cancellation [25].

Parameterization Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

The philosophy of force field development has evolved, leading to distinct methodologies for parameterization. The table below compares three primary approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Force Field Parameterization Methodologies

| Methodology | Description | Strengths | Limitations | Example Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional MM | Combines QM-derived bonded parameters with non-bonded parameters refined against experimental data. | High computational efficiency; Good reproduction of bulk properties via error cancellation [25]. | Transferability limited by empirical tuning; May oversimplify complex electronic interactions [25]. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS [11] [25] |

| Ab Initio / QM-Pure | Parameters derived entirely from high-level QM calculations, without empirical fitting to experiment. | High fidelity to first principles; Eliminates need for experimental data [25]. | Can be computationally expensive; Historically struggled with bulk properties without error cancellation [25]. | ByteFF-Pol (trained on ALMO-EDA) [25] |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Uses neural networks (e.g., GNNs) to predict parameters directly from molecular structure using QM data. | Expansive chemical space coverage; No need for pre-defined atom types [4]. | Requires very large QM training datasets; Computational cost higher than traditional MM [4]. | ByteFF, Espaloma [4] |

A major advancement is the emergence of ML-driven parameterization. For example, ByteFF employs a graph neural network (GNN) that preserves molecular symmetry to predict all bonded and non-bonded parameters simultaneously from a molecular graph, trained on a massive QM dataset [4]. This approach aims to overcome the scalability issues of traditional "look-up table" methods when dealing with millions of molecules [4]. Furthermore, next-generation force fields like ByteFF-Pol are addressing the accuracy limitations of classical models by incorporating polarizable terms and being trained exclusively on high-level QM energy decomposition analysis (ALMO-EDA), demonstrating that purely ab initio parameterization can predict macroscopic liquid properties with high accuracy [25].

Experimental Protocol: QM-Driven Parameterization with Experimental Validation

This protocol outlines the key steps for developing a robust force field, leveraging QM data for initial parameterization and experimental data for validation.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for force field parameterization, showing the continuous cycle between QM data generation, parameter fitting, MD simulation, and experimental validation.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Quantum Mechanics Data Generation

- Objective: Generate a high-quality, diverse QM dataset for target molecules.

- Procedure:

- Curation and Fragmentation: Select a diverse set of drug-like molecules from databases like ChEMBL and ZINC. Use a graph-expansion algorithm to cleave molecules into smaller, manageable fragments (<70 atoms) to ensure comprehensive coverage of local chemical environments [4].

- Conformer Generation: Generate initial 3D conformers for each fragment using tools like RDKit from their SMILES strings [4].

- QM Calculations: Perform the following calculations on the generated conformers:

- Geometry Optimization and Hessian Calculation: Optimize molecular structures and compute analytical Hessian matrices (vibrational frequencies) at a level of theory such as B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP, which offers a good balance of accuracy and computational cost [4]. This data is used to fit bonded parameters (bond, angle) [4].

- Torsion Scans: Perform relaxed potential energy scans for all non-ring torsional degrees of freedom. This involves systematically rotating a dihedral angle and optimizing the remaining coordinates at each step to map the rotational energy profile, which is critical for training torsion parameters [4].

- Non-Bonded Interaction Energy: For molecular dimers, compute interaction energies at a high level of theory (e.g., ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD). Use Energy Decomposition Analysis (EDA) methods like ALMO-EDA to decompose the total interaction energy into physically distinct components (electrostatics, polarization, dispersion, etc.) [25]. This provides targeted labels for parameterizing the individual terms of a polarizable force field.

Step 2: Machine Learning-Powered Parameter Fitting

- Objective: Train a model to predict force field parameters from molecular structure.

- Procedure:

- Model Selection: Employ a symmetry-preserving Graph Neural Network (GNN), such as an edge-augmented graph transformer. This architecture naturally handles molecular graphs and ensures predicted parameters are permutationally invariant and respect chemical symmetry [4] [25].

- Feature Engineering: Construct atom and bond features from the molecular graph to create initial embeddings [25].

- Model Training: Train the GNN model to predict all necessary force field parameters (bonded and non-bonded). The loss function should directly compare the MM energy (calculated using the predicted parameters and the molecular coordinates) with the reference QM energy labels. Advanced strategies like differentiable Hessian loss can improve the accuracy of bonded terms [4]. For polarizable force fields, the loss function should fit the decomposed MM energy terms to their corresponding ALMO-EDA components [25].

Step 3: Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Experimental Validation

- Objective: Test the force field's predictive power in realistic simulations and validate against experiment.

- Procedure:

- MD Simulation Setup: Use a standard MD engine (e.g., OpenMM, GROMACS) with the newly parameterized force field. Set up simulations for relevant systems, such as small-molecule liquids or protein-ligand complexes in explicit solvent [24] [27].

- Property Calculation: From the production MD trajectory, calculate a range of thermodynamic and transport properties. Key properties include:

- Validation Against Experiment: Compare the simulation-derived properties with available experimental data. Use statistical measures (e.g., root-mean-square error, R²) to quantify agreement.

- Iterative Refinement: If systematic discrepancies are found, the QM dataset may need to be expanded to include more relevant chemical motifs, or the training strategy may need adjustment before repeating the process [4].

Table 3: Essential Tools for Force Field Parameterization

| Category | Item / Software | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, Psi4 | Perform high-level QM calculations (geometry optimization, torsion scans, EDA) to generate training data [26]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | OpenMM, GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Run MD simulations to test force field parameters and compute macroscopic properties [25] [27]. |

| Force Field Parameterization Tools | GAFF, OpenFF, ByteFF, Espaloma | Provide baseline parameters or ML frameworks for developing new force fields [4] [11]. |

| Cheminformatics & Modeling | RDKit, MOE | Handle molecular structure manipulation, conformer generation, and visualization [4] [28]. |

| Specialized Analysis | ALMO-EDA (in Q-Chem) | Decompose intermolecular interaction energies into physical components for training polarizable force fields [25]. |

Specialized Force Fields for Biomolecules, Polymers, and Materials

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe the motion and interactions of atoms over time. The predictive quality of these simulations is primarily driven by the force field—a mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. Force fields approximate the complex quantum mechanical energy landscape by decomposing it into computable terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics). The accuracy of a simulation in replicating real-world behavior hinges on the careful selection and parameterization of these force fields. This guide provides a structured overview of specialized force fields for biomolecules, polymers, and materials, offering application notes and protocols to aid researchers in making informed choices for their specific systems.

Force Field Classification and Selection Criteria

Force Field Types and Generations

Force fields are broadly categorized by their functional form and parameterization philosophy. The table below summarizes the main types and their characteristics.

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Dynamics Force Fields

| Force Field Type | Key Features | Common Examples | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I (Fixed-Charge) | Harmonic potentials for bonds/angles; periodic dihedrals; computationally efficient. | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA, GROMOS [29] [30] | Folding of proteins with native folds; general biomolecular simulation [30]. |

| Class II (Anharmonic) | Includes cross-coupling terms (e.g., bond-angle); more complex functional forms. | PCFF, CFF, COMPASS [31] [29] | Thermomechanical properties of polymers and organic materials [31] [29]. |

| Polarizable | Accounts for electronic polarization; more physically accurate but computationally expensive. | AMBER, CHARMM polarizable variants | Systems where electronic response is critical. |

| Reactive | Allows bond formation/breaking; typically based on bond-order formalism. | ReaxFF, REBO [31] [32] | Chemical reactions, combustion, catalysis. |

| Machine Learning (MLFF) | Trained on quantum mechanical data; high accuracy without fixed functional forms. | MACE, CHGNet, Vivace, SimPoly, ByteFF [4] [32] [8] | Universal applications where quantum accuracy is required; polymer property prediction [32] [8]. |

Selection Guidelines for Different Material Classes

Choosing the correct force field is paramount. The following guidelines are based on benchmarking studies and reported best practices.

Biomolecules (Proteins, Nucleic Acids): For simulating folded proteins or nucleic acids, mature Class I force fields like AMBER ff99SB, CHARMM36, and OPLS-AA/L are highly recommended. A comparative study on polyglutamine peptides identified these three as producing structural properties in qualitative agreement with experiment [30]. For intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), selection requires greater caution, as some force fields may over-stabilize specific secondary structures [30].

Synthetic Polymers: Class II force fields like PCFF and COMPASS are often convenient for predicting the thermomechanical properties of amorphous polymer systems [29]. They have been successfully applied to systems like poly(methyl methacrylate) and polyisobutylene [29]. Recent advances, such as the PCFF-xe variant, integrate a Morse bond potential with reformulated exponential cross-terms, enabling the modeling of complete bond dissociation while maintaining the computational efficiency of a fixed-bond force field [31].

Materials and Drug-like Molecules: For inorganic materials or expansive drug-like chemical space, Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) show exceptional promise. MLFFs like ByteFF are trained on large, diverse quantum chemistry datasets and can predict properties across a broad chemical space with high accuracy [4]. Pre-trained universal MLFFs such as MACE, CHGNet, and M3GNet offer coverage for most of the periodic table and are available in simulation packages [33].

Application Notes and Quantitative Benchmarks

Performance Comparison for Polymers

Benchmarking against experimental data is crucial for validating force fields. The following table summarizes the performance of different force field approaches for predicting key polymer properties.

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of Force Fields for Polymer Properties

| Force Field / Approach | Material System | Target Property | Prediction Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCFF-xe (Class II-xe) | Crystalline, semi-crystalline, and amorphous organics (e.g., polybenzoxazine, PEEK) | Mass Density | Deviations from experiment < 3% for most systems; up to 7% for Cellulose Iβ and glassy carbon [31]. | [31] |

| Class II Force Fields | Poly(methyl methacrylate), Polyisobutylene | Thermomechanical Properties | Convenient and accurate for amorphous polymer systems [29]. | [29] |

| Vivace (MLFF) | 130 diverse polymers (PolyArena benchmark) | Bulk Density | Accurately predicted polymer densities, outperforming established classical FFs [32]. | [32] |

| Vivace (MLFF) | 130 diverse polymers (PolyArena benchmark) | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Capable of capturing second-order phase transitions, enabling Tg estimation [32]. | [32] |

| AMBER ff99SB* | Polyglutamine (Q30) peptide | Structural Properties (Radius of Gyration, Secondary Structure) | Predicted a heterogeneous ensemble of collapsed, disordered conformations, in agreement with experiment [30]. | [30] |

Fused Data Learning for Metals

A novel strategy for developing highly accurate force fields involves fusing data from both quantum simulations and experiments. This approach was demonstrated for titanium, where a Graph Neural Network potential was trained concurrently on:

- DFT Data: Energies, forces, and virial stress for various atomic configurations [8].

- Experimental Data: Temperature-dependent elastic constants and lattice parameters of hcp titanium [8].

The resulting DFT & EXP fused model faithfully reproduced all target properties, demonstrating that this strategy can correct for known inaccuracies in the underlying DFT functionals and yield a molecular model of superior accuracy [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Parametrizing a Machine Learning Force Field using Fused Data Learning

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to create a high-accuracy ML potential for titanium [8].

1. Data Generation and Curation

- Ab Initio Database: Generate a diverse set of atomic configurations (e.g., equilibrated, strained, randomly perturbed structures, high-temperature MD snapshots). Calculate target energies, forces, and virial stresses using a quantum mechanical method (e.g., DFT). A typical database may contain thousands of configurations [8].

- Experimental Database: Collate experimentally measured properties. For the titanium example, this included elastic constants and lattice parameters across a temperature range of 4 to 973 K [8].

2. Model Selection and Initialization

- Select a machine learning architecture, such as a Graph Neural Network (GNN).

- Initialize the model parameters by pre-training solely on the ab initio database. This provides a physically reasonable starting point and avoids the need for a simple prior potential [8].

3. Concurrent Training Loop Train the model by iteratively using two different trainers:

- DFT Trainer: For one epoch, perform batch optimization to minimize the loss between the model's predicted energies, forces, and virial stresses and the ab initio target values.

- EXP Trainer: For one epoch, optimize parameters such that the properties computed from ML-driven MD simulations match the experimental values. Use methods like Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) to calculate gradients without backpropagating through the entire simulation trajectory [8].

- Alternate between the DFT and EXP trainers for a fixed number of epochs, using an early stopping criterion to select the final model.

4. Validation and Testing

- Validate the final model on held-out ab initio data and experimental data.

- Test the model's transferability on out-of-target properties (e.g., phonon spectra, properties of different phases) to assess its general robustness [8].

Protocol: Converting a Class II Force Field for Bond Dissociation (PCFF to PCFF-xe)

This protocol enables the modeling of bond breaking in Class II force fields, combining the stability of fixed-bond models with reactive capabilities [31].

1. Replace Harmonic Bond Potential

- Substitute the standard harmonic bond stretching potential with a Morse bond potential for all relevant atom types. The Morse potential is defined by a dissociation energy (D), an equilibrium distance (r0), and a stiffness parameter (α) [31].

2. Reformulate Cross-Term Potentials

- Identify all cross-terms that couple bond stretching to other degrees of freedom (e.g., bond/bond, bond/angle).

- Reformulate these harmonic cross-term potentials into a new exponential functional form (ClassII-xe) [31].

- Derive the parameters for the new exponential cross-terms directly from the parameters of the Morse bonding potential and the original cross-terms, ensuring the physical meaning of parameters is conserved [31].

3. Parameterization and Benchmarking

- Use reparameterization methods, such as those implemented in the LUNAR software, for rapid model development [31].

- Benchmark the new PCFF-xe force field by simulating crystalline, semi-crystalline, and amorphous organic systems.

- Validate the model by comparing predicted physical properties (e.g., mass density) against experimental data and the original PCFF predictions to ensure accuracy is maintained or improved [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Data Resources for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Simulation Software | A highly versatile and widely used MD simulator that supports a vast array of force fields, including custom implementations. | [31] |

| LUNAR | Parametrization Software | Provides a user-friendly interface for the reparameterization of force fields, such as in the conversion to ClassII-xe. | [31] |

| PolyArena & PolyData | Benchmark & Dataset | A benchmark of experimental polymer properties and an accompanying quantum-chemical dataset for training and evaluating MLFFs. | [32] |

| RadonPy & Polyply | Polymer Building Tools | Open-source tools for generating initial polymer structures and packing them into simulation cells at realistic densities. | [34] |

| DiffTRe | Algorithm | A method for training force fields on experimental data without backpropagating through the entire MD trajectory. | [8] |

| ByteFF | ML Force Field | An Amber-compatible, data-driven force field for drug-like molecules, trained on a massive QM dataset using a graph neural network. | [4] |

| Vivace | ML Force Field | A fast, scalable, and accurate MLFF based on a local SE(3)-equivariant GNN, tailored for large-scale polymer simulations. | [32] |

Force Field Selection and Implementation Strategies for Drug Discovery Applications

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe the structural dynamics and functional mechanisms of biological molecules at an atomic level. The accuracy of these simulations is fundamentally governed by the empirical force field, which is a mathematical model describing the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates. Force fields compute the forces acting on each atom, thereby driving their motion during simulation. A well-validated force field must accurately reproduce experimental observables and quantum mechanical data, making the selection of an appropriate force field paramount to obtaining reliable, predictive results. Current biomolecular force fields have evolved through decades of refinement, yet they exhibit distinct strengths and limitations when applied to different classes of biomolecules—proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules—each presenting unique chemical and structural challenges.

The foundational functional form of most classical force fields includes terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatics). The most widely used models are additive force fields, which assign fixed partial atomic charges, effectively incorporating electronic polarization in an average, mean-field manner. While computationally efficient and successfully applied to a vast range of biological problems, this approximation is a significant source of error in heterogeneous environments where electronic redistribution is crucial. The next generation of polarizable force fields, such as the classical Drude oscillator and AMOEBA models, explicitly model electronic degrees of freedom by allowing charge distributions to respond to their local electric field. Although more computationally demanding, polarizable force fields offer a more physically realistic representation of electrostatic interactions, which is critical for modeling phenomena like ion permeation, ligand binding, and interfaces between biomolecules and solvents with differing polarities [35] [36].

This application note provides a structured guide for researchers to navigate the selection of molecular mechanics force fields for MD simulations of proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules. It presents a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art additive and polarizable force fields, detailed protocols for their implementation and validation, and visual guides for the selection workflow. The objective is to equip scientists with the knowledge to make informed decisions that enhance the accuracy and reliability of their computational studies in structural biology and drug discovery.

Force Field Selection Guide

Selecting an optimal force field requires a systematic approach based on the composition of the biomolecular system, the scientific question, and available computational resources. The following section provides a consolidated overview and comparative tables to guide this selection.

The development of biomolecular force fields has been largely carried out by several major families, each with a unique history and parametrization philosophy. The AMBER and CHARMM families are the most prevalent for proteins and nucleic acids. The AMBER force fields, such as ff14SB and ff19SB, are known for their careful optimization of backbone dihedral potentials to balance secondary structure propensities. The CHARMM family, including CHARMM36m, is noted for its rigorous parametrization against a wide range of target data, including crystallographic data, NMR observables, and thermodynamic properties. The OPLS-AA force field is another widely used model, particularly valued in the simulation of small molecules and for computing condensed-phase properties [35] [37].

A significant challenge in force field development is the accurate description of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs). These systems lack a stable folded structure and sample a heterogeneous conformational ensemble, making them highly sensitive to the balance between protein-water and protein-protein interactions. Traditional force fields, when combined with standard water models like TIP3P, often lead to an artificial structural collapse of IDPs, resulting in overly compact conformations that disagree with experimental data. This has prompted the development of corrected force fields like CHARMM36m and the use of modified water models such as TIP4P-D, which incorporates dispersion corrections to improve the solvation of disordered systems [38].

For nucleic acids, the AMBER and CHARMM lineages have also seen extensive refinement. Early AMBER force fields (e.g., ff94, ff99) suffered from inaccuracies in backbone dihedral sampling, leading to non-native conformations in long simulations. These issues have been progressively addressed through parameter sets like parmbsc0, parmbsc1, and OL modifications for DNA and RNA, which correct α/γ dihedrals and glycosidic torsion (χ) parameters. Similarly, the CHARMM nucleic acid force fields have evolved from C22 to C27 and the currently recommended CHARMM36, which improved backbone dihedrals (ε and ζ) and sugar puckering [39] [40].

Table 1: Summary of Recommended Additive Force Fields for Different Biomolecular Systems

| Biomolecular System | Recommended Force Field | Key Features and Strengths | Commonly Paired Water Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins (General) | AMBER ff19SB [41] | Recent update; improved backbone and side-chain torsions | TIP3P, OPC |

| Proteins (General) | CHARMM36 [35] | Balanced parameters for folded proteins; part of a consistent family with lipids/nucleic acids | TIP3P, TIP4P-D |

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | CHARMM36m [38] | Optimized for structured and disordered regions; prevents artificial collapse | TIP4P-D [38] |

| DNA | AMBER parmbsc1 [40] | Corrects backbone dihedral inaccuracies (α/γ); stable simulations of A, B, Z-DNA | TIP3P, SPCE |

| RNA | AMBER OL3 [40] | Refined χ dihedral; prevents ladder-like structural artifacts | TIP3P, OPC |

| Nucleic Acids (CHARMM) | CHARMM36 [40] | Improved ε/ζ dihedrals and sugar puckering; good performance for duplex DNA/RNA | TIP3P |

| Small Molecules (Drug-like) | CGenFF [36] | Compatible with CHARMM biomolecular FFs; broad coverage of chemical space | TIP3P |

| Small Molecules (Drug-like) | GAFF/GAFF2 [36] | Compatible with AMBER biomolecular FFs; widely used for organic molecules | TIP3P |

The Rise of Polarizable and Machine Learning Force Fields

Polarizable force fields represent a significant advancement in molecular modeling by explicitly treating electronic polarization. The Drude polarizable force field, also known as the classical Drude oscillator model, attaches negatively charged auxiliary particles (Drude oscillators) to non-hydrogen atoms via harmonic springs. These oscillators can displace in response to the local electric field, inducing atomic dipoles. The Drude FF has been parameterized for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and small molecules, and has demonstrated improved performance in modeling dielectric constants, peptide bond polarizability, and interactions in heterogeneous environments [35] [36].

The AMOEBA (Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications) polarizable force field utilizes a different approach, based on permanent atomic multipoles (charge, dipole, quadrupole) and induced dipole polarization. AMOEBA has been shown to provide a highly accurate description of molecular interactions, including the subtle energetics of base stacking and ion binding in nucleic acids [40].

While polarizable FFs offer superior physical fidelity, their computational cost has historically limited widespread adoption. However, efficient implementations in GPU-accelerated software like OpenMM and NAMD are making them increasingly accessible for production simulations [41] [40].

Concurrently, machine learning force fields (MLFFs) are emerging as a powerful alternative. MLFFs use neural networks to learn a quantum mechanical potential energy surface from reference data, potentially achieving density functional theory (DFT) accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. Models like MACE are being trained on datasets of solvated biomolecular fragments and demonstrate promising results in simulating small peptides [42]. Although not yet mature for routine application to large, complex biomolecules, MLFFs represent the cutting edge of force field development.

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Force Field Paradigms

| Force Field Type | Representative Examples | Underlying Model | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polarizable | CHARMM Drude [35] [36] | Classical Drude Oscillator | Explicit electronic polarization; better response to different environments | ~2-4x higher computational cost than additive FFs |

| Polarizable | AMOEBA [35] [40] | Induced Dipole + Atomic Multipoles | High electrostatic accuracy; excellent for ion binding | High computational cost; complex parameter set |

| Machine Learning | MACE [42] | Equivariant Neural Network | Near-DFT accuracy; great speedup over QM | Requires large training datasets; generalization to unseen systems |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Setup and Simulation for Additive Force Fields

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for setting up and running an all-atom MD simulation of a protein-DNA complex using the additive AMBER and CHARMM force fields. The example system is a DNA-binding protein complex, but the workflow is generalizable to other biomolecular systems.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Molecular System: Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure of the protein-DNA complex.

- Force Field Parameters: AMBER ff19SB for the protein [41], AMBER parmbsc1 for DNA [40], and the general AMBER force field (GAFF2) for any non-standard ligands [36].

- Solvent Model: TIP3P explicit water box [38].

- Ions: Monovalent (Na⁺, Cl⁻) and/or divalent (Mg²⁺) ions to neutralize system charge and mimic physiological concentration (~150 mM).

- Software: AMBER tools, GROMACS, or NAMD for simulation setup and production runs.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial atomic coordinates from the PDB (e.g., 1ABC). Remove crystallographic water molecules and other non-essential components using molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, VMD).

- Use tools like

pdb4amber(AMBER) orCHARMMM GUIto add missing hydrogen atoms and missing side-chain residues. For any non-standard residues or small molecule ligands, generate force field parameters usingantechamber(for GAFF2) or the CGenFF program.

Solvation and Ionization:

- Place the solvated macromolecule in a pre-equilibrated rectangular or rhombic dodecahedral water box, ensuring a minimum distance (e.g., 1.2 nm) between the solute and the box edges. The TIP3P water model is a standard choice [38].

- Add ions to neutralize the system's net charge. Subsequently, add additional ions to reach a desired physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl). This step is typically performed using software utilities like

tleap(AMBER) orgenion(GROMACS).

Energy Minimization:

- Conduct an initial energy minimization to remove any bad atomic contacts introduced during the setup process. This is typically done in two stages:

- Stage 1: Restrain the heavy atoms of the solute (protein/DNA) with a strong force constant (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) and minimize the energy of the solvent and ions.

- Stage 2: Perform a full, unrestrained minimization of the entire system until the maximum force falls below a chosen threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Conduct an initial energy minimization to remove any bad atomic contacts introduced during the setup process. This is typically done in two stages:

Equilibration:

- Gradually heat the system from 0 K to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) over 100-200 ps using a weak coupling algorithm (e.g., Berendsen thermostat) while maintaining positional restraints on solute heavy atoms.

- Subsequently, run a longer equilibration (e.g., 1 ns) in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to allow the solvent density to adjust and the system to reach a stable state. Use a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to maintain pressure at 1 bar. Continue to restrain solute heavy atoms during this phase.

Production MD:

- Initiate a production simulation without any positional restraints on the solute. Use a modern integration algorithm and a timestep of 2 fs, constraining bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Employ a more accurate thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostat for production runs.

- The length of the production run depends on the biological process under investigation, but for stability assessment, a simulation of 100 ns to 1 µs is typical. Save atomic coordinates (trajectories) at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for subsequent analysis.

Protocol 2: Validation and Benchmarking Against Experimental Data

Validation is a critical step to ensure the chosen force field produces a physically realistic representation of the system. This protocol describes key validation metrics for a simulated protein.