Accelerate Your Research: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Slow Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of computational chemistry, biophysics, and drug discovery, yet their extreme computational cost often hinders research progress.

Accelerate Your Research: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Slow Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of computational chemistry, biophysics, and drug discovery, yet their extreme computational cost often hinders research progress. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and developers seeking to optimize MD performance. We cover foundational concepts behind simulation bottlenecks, modern methodological breakthroughs like machine learning interatomic potentials and enhanced sampling, practical hardware and software tuning strategies, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing insights from the latest advancements, this guide offers a clear pathway to achieving faster, more efficient, and scientifically robust molecular dynamics simulations.

Understanding the Bottleneck: Why Your Molecular Dynamics Simulations Are Slow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Time and Sampling Challenges

Q1: Why can't I just use a larger time step to make my simulation run faster?

Using a time step larger than 2 femtoseconds (fs) in conventional molecular dynamics is generally unstable because it cannot accurately capture the fastest vibrations in the system, typically involving hydrogen atoms. While algorithms like hydrogen mass repartitioning (HMR) allow time steps of up to 4 fs by artificially increasing hydrogen atom mass, this approach has significant caveats. For simulations of processes like protein-ligand recognition, HMR can actually retard the binding process and increase the required simulation time, defeating the purpose of performance enhancement [1].

Q2: How long does my simulation need to be to ensure it has reached equilibrium?

There is no universal answer, as the required simulation time depends on your system and the properties you are measuring. A 2024 study suggests that while some average structural properties may converge on the microsecond timescale, others—particularly transition rates to low-probability conformations—may require substantially more time [2]. A system can be in "partial equilibrium," where some properties are converged but others are not. It is crucial to monitor multiple relevant metrics over time to assess convergence for your specific investigation.

Q3: What are my options for simulating large systems or long timescales?

The primary strategies for tackling scale challenges are multiscale modeling and enhanced sampling:

- Coarse-Grained (CG) Models: These combine groups of atoms into single interaction sites, reducing the number of particles and allowing simulation of larger systems for longer times. The Martini model is a popular example for biomolecular simulations [3].

- Enhanced Sampling Techniques: Methods like metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and replica exchange MD accelerate the exploration of energy landscapes by biasing the simulation to overcome energy barriers [3]. This allows you to observe rare events without running prohibitively long simulations.

Length Scale and System Size Challenges

Q4: My system of interest is very large (e.g., a lipid nanoparticle). Are all-atom simulations feasible?

All-atom (AA) simulations of large complexes like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are extremely computationally expensive, as solvent molecules often constitute over 70% of the atoms [3]. A practical solution is to use reduced model systems, such as a bilayer or multilamellar membrane with periodic boundary conditions, to approximate the larger structure's behavior [3]. For questions about self-assembly or large-scale structural changes, coarse-grained models are typically the most efficient choice.

Q5: How can I ensure my simulation results are robust and reproducible?

Major challenges persist in data generation, analysis, and curation. To improve robustness, follow these best practices [4]:

- Perform simulations that are hypothesis-driven.

- Use reliable and well-documented tools.

- Deposit simulation outcomes and protocols in public databases to promote reproducibility and accessibility.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Simulation is Progressing Too Slowly

Problem: The molecular dynamics simulation is taking an impractically long time to complete, hindering research progress.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Key Parameters & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Profile Computational Cost | Identify bottlenecks: Is the system too large? Are PME calculations dominating? Is the trajectory I/O slow? |

| 2 | Assess Time Step | Use a 2 fs time step with bond constraints (SHAKE/LINCS). Test HMR with a 4 fs step but validate that it doesn't alter kinetics for your process of interest [1]. |

| 3 | Evaluate System Size | For large systems, consider switching to a Coarse-Grained (CG) model (e.g., Martini). This can dramatically increase the simulable time and length scales [3]. |

| 4 | Implement Enhanced Sampling | If studying a rare event (e.g., ligand binding, conformational change), use enhanced sampling. Select a Collective Variable (CV) that accurately describes the process and apply methods like metadynamics or umbrella sampling [3]. |

Issue 2: System Fails to Reach Equilibrium

Problem: The simulated system appears trapped in a non-equilibrium state, and measured properties have not converged, making the results unreliable.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Key Parameters & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Multiple Metrics | Monitor convergence of several properties: potential energy, RMSD, radius of gyration (Rg), and biologically relevant distances/angles. |

| 2 | Extend Simulation Time | Continue the simulation while monitoring your metrics. For complex biomolecules, multi-microsecond trajectories may be needed for some properties to converge [2]. |

| 3 | Use Advanced Analysis | Calculate time-lagged independent components or autocorrelation functions for key properties to check if they have stabilized [2]. |

| 4 | Consider Enhanced Sampling | If the system is stuck in a deep local energy minimum, use replica exchange MD (REMD) or metadynamics to help it escape and explore the conformational space more effectively [3]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Overcoming Scale Challenges

| Tool / Method | Function | Key Application in Scale Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) [1] | Allows ~2x longer time step (4 fs) by increasing H atom mass. | Accelerating simulation speed, but requires validation for kinetic studies. |

| Coarse-Grained (CG) Force Fields (e.g., Martini) [3] | Represents groups of atoms as single beads. | Simulating large systems (e.g., membranes, LNPs) over longer timescales. |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms (Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling) [3] | Accelerates exploration of conformational space by biasing simulation. | Studying rare events (e.g., binding, folding) without ultra-long simulations. |

| Constant pH Molecular Dynamics (CpHMD) [3] | Models environment-dependent protonation states in MD. | Accurately simulating ionizable lipids in LNPs or pH-dependent processes. |

| Global Optimization Methods (Basin Hopping, Genetic Algorithms) [5] | Locates the global minimum on a complex potential energy surface. | Predicting stable molecular configurations and reaction pathways. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) & GPUs [6] | Provides the raw computational power for MD. | Executing microsecond-to-millisecond timescale simulations. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating HMR for a Protein-Ligand System

Objective: To determine if Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) provides a net performance benefit for simulating a specific protein-ligand binding event without distorting the binding kinetics [1].

Materials:

- Protein structure (e.g., from PDB).

- Ligand parameter files.

- MD software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER) with HMR capability.

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Prepare two identical simulation systems: one for regular MD and one for HMR MD.

- For the regular system, set the time step to 2 fs.

- For the HMR system, repartition the masses (e.g., set hydrogen mass to 3.0 amu) and set the time step to 4 fs [1].

- Simulation Execution:

- For each system, run multiple independent, unbiased MD trajectories.

- Ensure simulations are long enough to capture multiple binding and unbinding events.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantify Performance: Measure the wall-clock time and aggregate simulation time required to observe the first binding event and to achieve a statistically robust measurement of the binding rate in both setups.

- Validate Kinetics: Calculate the ligand residence time and diffusion coefficient in both simulation sets.

- Validate Thermodynamics: Confirm that the final, bound pose matches the experimental structure (e.g., from crystallography) in both setups.

Expected Outcome: HMR may speed up individual simulation steps but might slow down the observed binding process. The net computational cost for HMR could be similar to or greater than regular MD for this specific application, highlighting the importance of case-by-case validation [1].

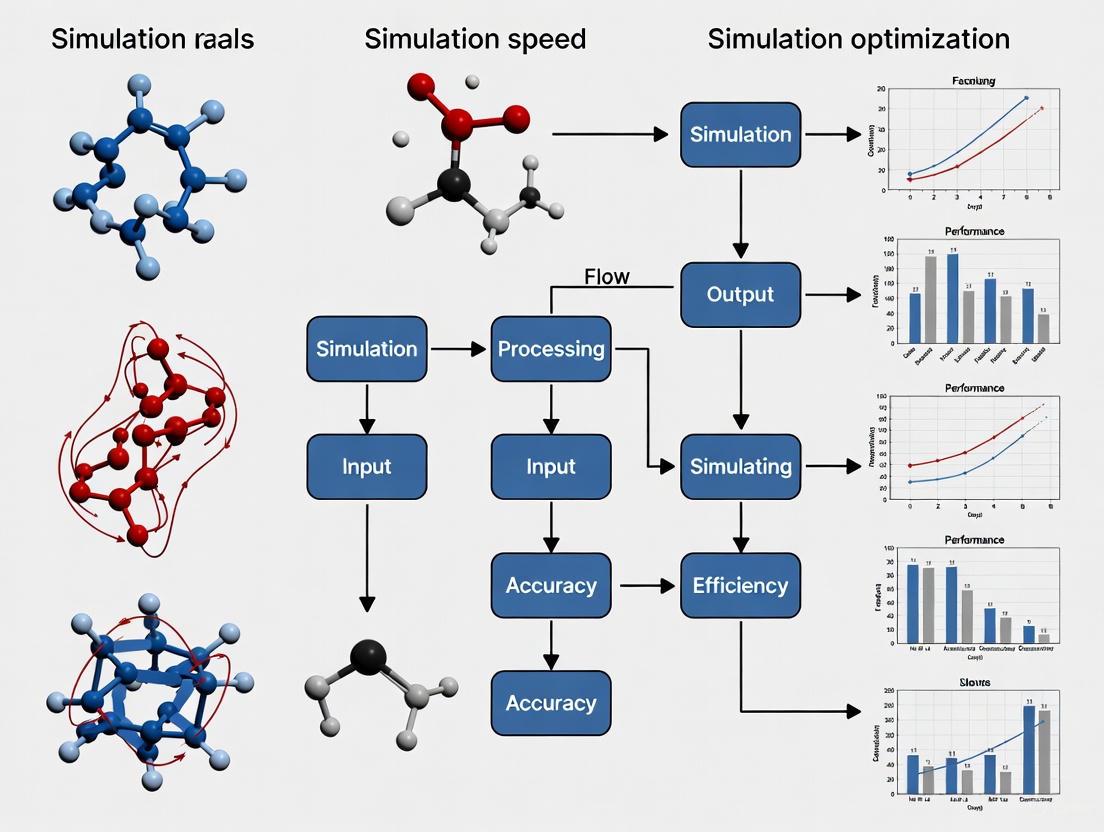

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are pivotal in computational chemistry, biophysics, and materials science, enabling researchers to study atomic and molecular movements. However, these simulations demand intensive computational resources, and their speed is governed by a delicate balance between three fundamental factors: the choice of force field, the system size, and the sampling methodology [7] [8]. As simulations grow in complexity, optimizing these elements becomes critical to achieving realistic results within feasible timeframes. This guide provides a technical troubleshooting framework to help researchers diagnose and resolve common speed bottlenecks, directly supporting broader efforts in MD simulation optimization research.

Force Field Selection and Its Impact on Performance and Accuracy

The force field defines the potential energy surface governing atomic interactions. Its selection is a primary factor influencing not only the physical accuracy of a simulation but also its computational expense and the convergence rate of sampling.

Traditional vs. Modern Machine Learning Force Fields

The table below compares the characteristics of different force field types, highlighting their direct impact on simulation performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Types and Their Impact on Simulation

| Force Field Type | Computational Cost | Key Performance Consideration | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) [8] | Low | Speed comes at the cost of fixed bonding and pre-defined parameters; may produce biased ensembles for IDPs [8]. | Standard simulations of folded proteins, nucleic acids. |

| Polarizable Force Fields | Medium-High | More physically realistic but significantly increases cost per timestep; requires careful parameterization. | Systems where electronic polarization is critical. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Force Fields (e.g., Neural Network Potentials) [9] [10] | Variable (High during training, Lower during inference) | Can achieve quantum-level accuracy with classical MD efficiency; training requires extensive data but can leverage both DFT and experimental data [9]. | Systems requiring quantum accuracy for reactive processes or complex materials [10]. |

Troubleshooting Force Field-Related Issues

FAQ: My simulation of an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) is overly collapsed and structured, contradicting experimental data. What is wrong?

- Cause: Standard pairwise additive force fields are often parameterized using data from folded proteins and can exhibit a bias toward overly collapsed and ordered structural ensembles for IDPs and unfolded proteins [8].

- Solution: Consider using a force field that has been specifically modified for IDPs or unfolded states (e.g., some newer CHARMM or Amber variants). Furthermore, ensure you are using an enhanced sampling technique, as the combination of force field and sampling protocol is critical. A standard force field combined with advanced sampling like Temperature Cool Walking (TCW) may yield better results than an IDP-optimized force field with poor sampling [8].

FAQ: How can I make my ML force field more accurate without generating a massive new DFT dataset?

- Solution: Implement a fused data learning strategy. Train your ML potential concurrently on both available Density Functional Theory (DFT) data (energies, forces, virial stress) and experimentally measured properties (e.g., lattice parameters, elastic constants). This approach can correct for known inaccuracies in the base DFT functional and results in a molecular model of higher overall accuracy, better constrained by real-world data [9].

System Size and Hardware Configuration

The number of atoms in your system and the hardware used to run the simulation are intimately linked. Selecting the right hardware for your system size and software is crucial for performance.

Optimizing Hardware for Different System Sizes and Software

The hardware configuration must be matched to the computational profile of the MD software, which often offloads the most intensive calculations to the GPU.

Table 2: Hardware Recommendations for MD Simulations based on System Size and Software

| System Size / Type | Recommended CPU | Recommended GPU | Recommended RAM/VRAM | Typical Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small-Medium Systems (<100,000 atoms) | Mid-tier CPU with high clock speed (e.g., AMD Ryzen Threadripper) [7]. | NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB) or RTX 5000 Ada (24 GB) for a balance of price and performance [7]. | 64-128 GB System RAM; GPU with ≥24 GB VRAM [7]. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD |

| Large-Scale Systems (>100,000 atoms) & IDP Ensembles | High core count for parallel sampling; consider dual CPU setups (AMD EPYC, Intel Xeon) [7]. | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB) for handling the most memory-intensive simulations [7]. | 256+ GB System RAM; GPU with ≥48 GB VRAM is critical [7]. | NAMD, AMBER, GROMACS |

| Advanced Sampling (e.g., Replica Exchange) | High core count to run multiple replicas efficiently [8]. | Multiple GPUs (e.g., 2-4x RTX 4090 or RTX 6000 Ada) to run replicas in parallel [7]. | Scale RAM with replica count. | GROMACS, AMBER |

Troubleshooting Hardware and System Setup Issues

FAQ: My simulation fails with an "Out of memory when allocating" error.

- Cause: The program has attempted to assign more memory than is available, which can happen during analysis or simulation [11].

- Solutions:

- Reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis in post-processing [11].

- For the simulation itself, use a computer with more memory or install more RAM [11].

- Check for configuration errors; for example, confusion between Ångström and nm in

gmx solvatecan create a water box 1000 times larger than intended, instantly exhausting memory [11].

FAQ: How can I speed up my simulation for a large, complex system?

- Solutions:

- GPU Offloading: Ensure you are using a build of your MD software that leverages GPUs. For most modern MD codes, the GPU is the primary workhorse.

- Multi-GPU Setups: Utilize multi-GPU systems to dramatically enhance computational efficiency and decrease simulation times, especially for software like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD that are well-optimized for such configurations [7].

- Purpose-Built Workstations: Consider systems from specialized vendors (e.g., BIZON) that offer optimized configurations with advanced cooling and power management for stable, high-load computing [7].

Sampling Methods: Achieving Convergence in Simulation Time

The "sampling problem" refers to the challenge of exploring the relevant conformational space of a molecular system within a feasible simulation time. For systems with rough energy landscapes, like IDPs, enhanced sampling methods are not a luxury but a necessity.

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

These methods are designed to accelerate the crossing of energy barriers and improve the convergence of structural ensembles.

Table 3: Comparison of Enhanced Sampling Methods for MD Simulations

| Sampling Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Replica Exchange (TREx) [8] | Multiple replicas run at different temperatures, periodically swapping. | Widely used; good for global exploration. | Can be inefficient (diffusive) for systems with entropic barriers; requires many replicas and high computational resource [8]. |

| Temperature Cool Walking (TCW) [8] | A non-equilibrium method using one high-temperature replica to generate trial moves for the target replica. | Converges more quickly to the proper equilibrium distribution than TREx at a much lower computational expense [8]. | Less established than TREx; implementation may be less widely available. |

| Markov State Models (MSM) [8] | Many short, independent simulations are combined to model long-timescale kinetics. | Can model very long timescales; parallelizable. | Model quality depends on clustering and state definition; requires many initial conditions. |

| Metadynamics [8] | History-dependent bias potential is added to discourage the system from visiting already sampled states. | Efficiently explores free energy surfaces along pre-defined collective variables. | Choice of collective variables is critical and not always trivial. |

Workflow: Selecting a Sampling Strategy

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate sampling method based on system characteristics and research goals.

Troubleshooting Sampling and Convergence Issues

FAQ: My enhanced sampling simulation (e.g., TREx) is taking too long and doesn't seem to be converging for my IDP system.

- Cause: TREx can be inefficient and diffusive for systems whose energy landscapes are dominated by entropic barriers, which is common in IDPs. The closely spaced intermediate replicas do not effectively facilitate barrier crossing [8].

- Solution: Consider switching to a more efficient sampling algorithm like Temperature Cool Walking (TCW), which has been shown to converge more quickly and produce qualitatively different, and more accurate, ensembles for Aβ peptides compared to TREx [8]. Alternatively, Markov State Models (MSM) built from many short simulations can also be an effective strategy [8].

FAQ: How do I know if my simulation has sampled enough?

- Solution: There is no single answer, but convergence should be assessed by monitoring:

- Stability of Properties: Key observables (e.g., Radius of Gyration, RMSD, secondary structure content) should plateau and fluctuate around a stable average.

- Quantitative Metrics: Use tools like

gmx analyzein GROMACS to check statistical errors. - Experimental Validation: Where possible, back-calculate experimental observables (e.g., NMR J-couplings, chemical shifts, FRET efficiencies) from your simulation ensemble and compare directly with real data. This is the ultimate test of a converged and accurate ensemble [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in setting up and running MD simulations.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Item / Software | Function | Example Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [12] [11] | A versatile package for performing MD simulations; highly optimized for speed on both CPUs and GPUs. | Often the first choice for benchmarked performance on new hardware. |

| AMBER, NAMD [7] | Specialized MD software packages, particularly strong in biomolecular simulations and free energy calculations. | AMBER is highly optimized for NVIDIA GPUs [7]. |

| OpenMM [8] | A toolkit for MD simulation that emphasizes high performance and flexibility. | Used as the engine for developing and implementing new sampling methods like TCW [8]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (e.g., EMFF-2025) [10] | A general neural network potential for specific classes of materials (e.g., energetic materials with C, H, N, O). | Provides a versatile computational framework with DFT-level accuracy for large-scale reactive simulations [10]. |

| DP-GEN (Deep Potential Generator) [10] | An active learning framework for generating ML-based force fields. | Used to build general-purpose neural network potentials efficiently via transfer learning [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My simulation is running slower than expected. What are the first things I should check? Start with the hardware and software configuration. Confirm that your simulation is configured to run on a GPU rather than just the CPU, as this can lead to a performance increase of over 700 times for some systems [13]. Ensure you are using a molecular dynamics package, such as LAMMPS, GROMACS, or OpenMM, that supports GPU acceleration and that it has been installed and configured correctly for your hardware [14].

Q2: How do I know if my bottleneck is related to hardware or the simulation methodology? A hardware bottleneck often manifests as consistently slow performance across different simulation stages and system sizes. A methodological bottleneck might appear when simulating specific molecular interactions or when using certain force fields. The diagnostic flowchart below guides you through this process. Profiling your code can often pinpoint if the CPU or GPU is the limiting factor [14] [13].

Q3: My GPU is not being fully utilized. What could be the cause? This can be caused by several factors. The algorithm may be inherently CPU-bound, with the GPU only handling non-bonded force calculations while the CPU handles the rest, leading to an imbalance [14]. Frequent data transfer between the CPU and GPU across the PCIe bus can also create a major bottleneck; data should be transferred as infrequently as possible [13]. Finally, the system size might be too small to fully utilize all the parallel processing units of a modern GPU [13].

Q4: What are common optimization issues when using machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs)? Optimizations with Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) can fail to converge within a reasonable number of steps or can converge to saddle points (structures with imaginary frequencies) instead of true local minima. The choice of geometry optimizer significantly impacts success rates and the quality of the final structure [15].

Q5: Are there specific hardware recommendations for different MD software packages? Yes, different software packages benefit from different hardware optimizations. For general molecular dynamics, a balance of high CPU clock speeds and powerful GPUs is key. For AMBER, GPUs with large VRAM, like the NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB), are ideal for large-scale simulations. For GROMACS and NAMD, the NVIDIA RTX 4090 is an excellent choice due to its high CUDA core count [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Use the following diagnostic flowchart to systematically identify the source of your performance bottleneck. The corresponding troubleshooting actions for each endpoint are detailed in the subsequent guides.

Diagnosing Simulation Performance Bottlenecks

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Hardware Bottlenecks

| Diagnostic Question | Solution & Action Plan |

|---|---|

| Is the simulation not leveraging GPU acceleration? | Action: Verify that your MD package was compiled with GPU support (e.g., LAMMPS with Kokkos, OpenMM with CUDA/OpenCL) and that the simulation script explicitly uses the GPU-enabled pair styles or integrators [14] [17]. |

| Is the CPU-GPU data transfer causing a bottleneck? | Action: Profile the code to measure time spent on data transfer. Restructure the simulation to keep all calculations on the GPU, transferring results back to the CPU only infrequently for analysis [13]. |

| Is the system size too small for the GPU? | Action: For systems with atoms numbering in the hundreds, the parallel architecture of a GPU may be underutilized. Consider running on a CPU or batching multiple small simulations together [13]. |

| Is there a CPU-GPU performance imbalance? | Action: This is common in hybrid approaches. If the CPU cannot prepare data fast enough for the GPU, consider using a more CPU-powerful processor or a GPU-oriented MD package like OpenMM that minimizes CPU involvement [14]. |

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Software & Configuration Issues

| Diagnostic Question | Solution & Action Plan |

|---|---|

| Is the MD package sub-optimal for your system type? | Action: Evaluate if your package is suited for your system. LAMMPS is highly flexible for diverse systems, while OpenMM is often faster for biomolecular simulations when a powerful GPU is available [14]. |

| Are the integration time steps too small? | Action: Increase the time step (dtion) to the largest stable value. Using hydrogen mass repartitioning can often allow for larger time steps (e.g., 4 fs) without sacrificing stability [18]. |

| Is the neighbor list building too frequent? | Action: Increase the neighbor list skin distance (skin or neigh_modify in LAMMPS) to reduce the frequency of list updates, but balance this with the increased list size [13]. |

Guide 4: Troubleshooting Methodological & Force Field Bottlenecks

| Diagnostic Question | Solution & Action Plan |

|---|---|

| Are force field parameters inaccurate or difficult to optimize? | Action: For novel molecules, traditional force fields (GAFF, OPLS) may be inadequate. Use modern machine learning-based optimization methods (e.g., fine-tuning a model like DPA-2) to generate accurate parameters on-the-fly, reducing manual effort and computational cost [19]. |

| Do geometry optimizations with NNPs fail to converge or find false minima? | Action: The optimizer choice is critical. For NNPs, the Sella optimizer with internal coordinates has been shown to achieve a high success rate and find true minima (fewer imaginary frequencies). Avoid using geomeTRIC in Cartesian coordinates with NNPs, as it has a very low success rate [15]. |

| Is the simulation sampling inefficiently? | Action: For enhanced sampling of rare events, consider advanced methods like meta-dynamics or parallel tempering. For long-timescale simulations, new "force-free" ML-driven frameworks can accelerate sampling by using larger time steps [20]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential computational tools and their functions in MD simulations.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A classical MD code for a wide range of systems (soft matter, biomolecules, polymers). Uses a hybrid CPU-GPU approach [14]. | Ideal for complex, non-standard systems. Performance depends on a balanced CPU-GPU setup [14]. |

| OpenMM | A MD code designed for high-performance simulation of biomolecular systems. Uses a GPU-oriented approach [14]. | Often delivers superior GPU performance for standard biomolecular simulations [14]. |

| ML-IAP-Kokkos | An interface for integrating PyTorch-based Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) with LAMMPS [17]. | Enables fast, scalable AI-driven MD simulations. Requires a LAMMPS build with Kokkos and Python support [17]. |

| Sella Optimizer | An open-source geometry optimization package, effective for finding minima and transition states [15]. | Particularly effective for optimizing structures using NNPs, especially with its internal coordinate system [15]. |

| DPA-2 Model | A pre-trained machine learning model that can be fine-tuned for force field parameter optimization [19]. | Accelerates and automates the traditionally labor-intensive process of intramolecular force field optimization [19]. |

| NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | A professional-grade GPU with 48 GB of VRAM and 18,176 CUDA cores [16]. | Excellent for large-scale, memory-intensive simulations in AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD [16]. |

| NVIDIA RTX 4090 | A consumer-grade GPU with 24 GB of GDDR6X VRAM and 16,384 CUDA cores [16]. | Offers a strong balance of price and performance for computationally intensive simulations in GROMACS [16]. |

The pursuit of accurate molecular simulations necessitates navigating the inherent compromises between computational fidelity and performance. The table below summarizes the key quantitative trade-offs between major simulation methodologies.

Table 1: Accuracy vs. Speed in Molecular Simulation Methods

| Simulation Method | Typical Energy Error (εe) | Typical Force Error (εf) | Relative Speed (Steps/sec/atom) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD (CMD) | ~10.0 kcal/mol (434 meV/atom) [21] | High (Force-field dependent) [21] | Very High [21] | Large-scale systems, polymer dynamics, screening [22] [23] |

| Machine Learning MD (MLMD) | ~1.84 - 85.35 meV/atom (ab initio accuracy) [10] [21] | ~13.91 - 173.20 meV/Å [21] | Medium (on GPU/CPU) [21] | Energetic materials, reaction chemistry, property prediction [10] |

| Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | Ab initio accuracy (reference method) [21] | Ab initio accuracy (reference method) [21] | Very Low [21] | Electronic properties, chemical reactions, catalysis [24] [25] |

| Special-Purpose MDPU | ~1.66 - 85.35 meV/atom [21] | ~13.91 - 173.20 meV/Å [21] | 10³-10⁹x faster than MLMD/AIMD [21] | Large-size/long-duration problems with ab initio accuracy [21] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My molecular dynamics simulation is running very slowly. What are the common causes and solutions?

Slow simulation performance is a frequent challenge. The solution depends on your hardware and system setup.

- Check Your Compilation and GPU Support: If you are using GROMACS, a pre-compiled binary from a package manager may not have GPU support enabled, forcing calculations onto the CPU. Ensure you have compiled GROMACS from source with the

-DGMX_GPU=CUDAflag and properly source theGMXRCfile. A performance of around 4 ns/day on a single workstation might be normal for a moderately sized system, but utilizing a GPU can dramatically improve this [26]. - Verify System Size and Simulation Parameters: Performance scales with the number of atoms. A common mistake during system setup is confusion between Ångström and nanometers, potentially creating a simulation box 1,000 times larger than intended. Always double-check your unit cell dimensions [27].

- Optimize Neighbor Searching: Employ efficient cell decomposition algorithms for non-bonded neighbor list updates. Using multiple time-stepping schemes, where forces for close-range interactions are calculated more frequently than long-range ones, can also save significant CPU time [28].

FAQ 2: My simulation crashes with an "Out of memory" error. How can I resolve this?

This error occurs when the program cannot allocate sufficient memory.

- Reduce Analysis Scope: When processing trajectory files, reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis or the length of the trajectory being read in at once [27].

- Check System Size: As above, confirm your system is not accidentally oversized due to a unit error [27].

- Upgrade Hardware: If the system size is correct and necessary, you may need to use a computer with more RAM or install more memory [27].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the accuracy of my force field for modeling chemical reactions?

Classical force fields often struggle with accurately describing bond formation and breaking.

- Adopt a Neural Network Potential (NNP): Methods like the EMFF-2025 potential for C, H, N, O systems leverage machine learning to achieve Density Functional Theory (DFT)-level accuracy in predicting structures, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics, while being far more efficient than quantum mechanical methods [10].

- Use a Reactive Force Field: ReaxFF employs bond-order-dependent charges to model reactive and non-reactive interactions, though it may still have deviations from DFT accuracy for new systems [10].

- Apply a Multi-Scale Approach: Combine classical MD for large-scale sampling with rare-event techniques (like COLVARS) and targeted DFT calculations. This provides mechanistic insight at the electronic level while managing computational cost [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a General Neural Network Potential (e.g., EMFF-2025)

This protocol outlines the creation of a general-purpose NNP for high-energy materials (HEMs) with C, H, N, O elements [10].

- Objective: To create a fast, accurate, and generalizable potential for predicting mechanical properties and chemical behavior of condensed-phase HEMs.

- Methodology:

- Leverage a Pre-trained Model: Start with an existing pre-trained NNP model (e.g., DP-CHNO-2024) as a foundation [10].

- Incorporate New Data via Transfer Learning: Use a framework like DP-GEN (Deep Potential Generator) to incorporate a small amount of new, system-specific training data from DFT calculations. This expands the model's applicability without requiring massive datasets [10].

- Model Training and Validation:

- Training: Fit the neural network to the combined dataset.

- Validation: Systematically evaluate the model's performance by comparing its predictions of energy and atomic forces against DFT results. Target a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energy within ± 0.1 eV/atom and for force within ± 2 eV/Å [10].

- Application: Use the validated EMFF-2025 model to run MD simulations for predicting crystal structures, mechanical properties, and thermal decomposition behaviors of HEMs. Benchmark the results against experimental data [10].

- Visualization: Diagram: Workflow for Developing a General Neural Network Potential

Protocol 2: A Multi-Scale Framework for CO2 Capture Modeling

This protocol describes a three-tier approach to model CO₂ capture in aqueous monoethanolamine (MEA), linking atomic-scale transport to electronic interactions [25].

- Objective: To gain a mechanistic understanding of CO₂ capture by integrating methods across multiple scales.

- Methodology:

- Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD):

- Setup: Construct a system of CO₂ and 26 wt% aqueous MEA in a simulation box with a gas-liquid interface at 327.15 K [25].

- Execution: Run MD simulations to observe the two-stage capture pathway: rapid interfacial accommodation followed by slower absorption and diffusion into the bulk liquid. Calculate the bulk translational self-diffusion coefficient of CO₂ [25].

- Steered Rare-Event Sampling (COLVARS):

- Setup: Define a collective variable representing the distance or orientation between CO₂ and the amine group of MEA [25].

- Execution: Perform biased dynamics simulations to resolve the orientation-dependent approach of CO₂ to MEA. This calculates an effective one-dimensional diffusivity for the association step, identifying kinetic bottlenecks [25].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations:

- Setup: Use DFT with D3 dispersion correction to model the interaction between a single MEA molecule and CO₂ [25].

- Execution: Calculate binding energies for CO₂ associating with the NH₂ and OH groups of MEA. Analyze charge transfer. Investigate the effect of an external electric field (e.g., 0.1 V/Å) on the interaction energy to explore solvent regeneration strategies [25].

- Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD):

- Visualization: Diagram: Multi-scale Simulation Workflow for CO2 Capture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Advanced Molecular Simulation

| Tool / Material | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile software package for performing classical MD simulations [22] [26]. | Standard for simulating molecular systems with classical force fields; widely used in biochemistry and materials science [22]. |

| Deep Potential (DP) | A machine learning scheme for developing interatomic potentials with ab initio accuracy [10] [21]. | Creating Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) for systems where chemical reactions or high accuracy are critical [10]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A quantum mechanical method for electronic structure calculation [24] [21] [25]. | Provides benchmark energy and force data for training NNPs; studies electronic properties and reaction mechanisms [10] [25]. |

| ReaxFF | A reactive force field that allows for bond formation and breaking [10]. | Simulating combustion, decomposition, and other complex chemical processes in large systems [10]. |

| COLVARS | A software library for performing rare-event sampling simulations [25]. | Studying processes with high energy barriers, such as chemical absorption or conformational changes, that occur on timescales beyond standard MD [25]. |

Modern Acceleration Techniques: From Machine Learning Potentials to Enhanced Sampling

Revolutionizing Speed and Accuracy with Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs)

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Simulation Crashes with "Out of Memory" Error

- Problem: The program fails to allocate memory during a calculation or analysis.

- Diagnosis: This is a common error when the system size or trajectory length exceeds available RAM. The computational cost for various activities can scale with the number of atoms (N) as order N, NlogN, or N² [29].

- Solutions:

- Reduce the number of atoms selected for analysis.

- Process a shorter segment of your trajectory file.

- Verify unit consistency during system setup (e.g., ensure a water box is created in nm, not Ångström, to avoid creating a system 10³ times larger than intended) [29].

- Use a computer with more memory.

Issue 2: Residue or Molecule Not Recognized During Topology Generation

- Problem: When using a tool like

pdb2gmx, you get an error: "Residue 'XXX' not found in residue topology database" [29]. - Diagnosis: The force field you selected does not contain a database entry for the residue or molecule 'XXX'. The topology cannot be generated automatically.

- Solutions:

- Check if the residue exists under a different name in the force field's database and rename your molecule accordingly.

- Find a topology file (.itp) for the molecule from a reputable source and include it manually in your system's topology.

- Use a different force field that has parameters for your molecule.

- Parameterize the molecule yourself (requires significant expertise) [29].

Issue 3: Simulation Becomes Unstable with MLIPs

- Problem: A molecular dynamics simulation using an MLIP force field crashes or produces unrealistic trajectories (e.g., atoms flying apart).

- Diagnosis: The MLIP model is being applied outside its valid domain or the initial system configuration is problematic.

- Solutions:

- Domain Check: Ensure your system's atomic compositions and conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure) are within the training data domain of the MLIP model. Do not extrapolate.

- Visual Inspection: Visually inspect your starting geometry and initial trajectory frames using software like VMD or PyMol. Look for atoms placed too close together or distorted bonds [30].

- Energy Monitoring: Plot the system's potential energy throughout the simulation. It should be negative and relatively stable (unless extreme conditions are being simulated) [30].

- Energy Minimization: Perform a thorough energy minimization of your system before starting the production MD run.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and why are they important?

MLIPs are a novel computational approach that uses machine learning to estimate the forces and energies between atoms. They disrupt the long-standing trade-off in molecular science between computational speed and quantum-mechanical accuracy. MLIPs can approach the precision of quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) while reducing the computational cost by several orders of magnitude, making previously infeasible simulations possible [31] [32].

Q2: How can I visually check if my simulation is running properly?

Always visualize your system geometry and trajectory. This can reveal many setup problems [30]. Key things to check:

- Initial Structure: Ensure no atoms are overlapping and all bonds look reasonable.

- Trajectory: Watch the simulation animation to see if the system behavior looks physically realistic (e.g., no atoms suddenly jumping or molecules disintegrating).

- Analysis: Generate plots of key properties over time, such as potential energy, density, temperature, and pressure. They should fluctuate around stable values [30].

Q3: My simulation ran without crashing, but how do I know the results are correct?

A successful run does not guarantee physical accuracy. To validate your simulation:

- Reproduce Known Results: Start by simulating a well-studied system and confirm you can reproduce established results or follow a tutorial successfully [30].

- Analyze Properties: Calculate properties like Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs) to check for reasonable atomic interactions. Look for unexpected peaks that indicate atoms are too close [30].

- Check System Properties: For a protein simulation, generating a Ramachandran plot can help verify the structural integrity of the protein throughout the trajectory [30].

Q4: What is the mlip library and who is it for?

The mlip library is a consolidated, open-source environment for working with MLIP models. It is designed with two core user groups in mind:

- Industry Experts & Domain Scientists (e.g., biologists, materials scientists): It provides user-friendly and computationally efficient tools to run MLIP simulations without requiring deep machine learning expertise.

- ML Developers & Researchers: It offers a flexible framework to develop and test novel MLIP architectures, fully integrated with molecular dynamics tools [31] [32].

Performance Data and Protocols

Quantitative Performance of MLIP Models

The following table summarizes the key attributes of popular MLIP architectures available in libraries like mlip, which are trained on datasets like SPICE2 containing ~1.7 million molecular structures [32].

Table 1: Comparison of MLIP Model Architectures and Performance

| Model Architecture | Reported Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | High | Efficient | Strong all-around performance on benchmarks [32] |

| NequIP | High | Good | Data-efficient, high accuracy [32] |

| ViSNet | High | Good | Incorporates directional information [32] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an MLIP Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up and running a molecular dynamics simulation using an MLIP.

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial atomic coordinates for your system (e.g., from a PDB file).

- Use a tool like

pdb2gmxto generate a topology if using standard residues. For non-standard molecules, provide a pre-parameterized topology file [29].

MLIP Model Selection:

Simulation Setup:

- Use a Molecular Dynamics wrapper like ASE or JAX-MD that is integrated with the MLIP library. These wrappers act as a bridge, allowing you to use the MLIP-generated forces within established simulation workflows [31] [32].

- Define simulation parameters: ensemble (NVT, NPT), temperature, pressure, timestep, and total simulation time.

Energy Minimization:

- Run an energy minimization step to remove any bad contacts or high-energy strains in the initial structure.

Equilibration:

- Run equilibration simulations to bring the system to the desired temperature and density.

Production Run:

- Execute the production MD simulation to collect data for analysis.

Validation and Analysis:

- Visually inspect the trajectory.

- Plot and analyze energy, temperature, density, and other relevant properties over time to ensure stability [30].

- Calculate the scientific properties of interest (e.g., RDFs, diffusion coefficients).

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: MLIP Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for MLIP Experiments

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

MLIP Library (e.g., mlip) |

A consolidated software library providing efficient tools for training, developing, and running simulations with MLIP models. It includes pre-trained models and MD wrappers [31] [32]. |

| Pre-trained Models (MACE, NequIP, ViSNet) | High-performance, graph-based machine learning models that have been trained on large quantum mechanical datasets (e.g., SPICE2). They are used to predict interatomic forces and energies with near-quantum accuracy [31] [32]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Wrappers (ASE, JAX-MD) | Software interfaces that connect MLIP models to molecular dynamics engines. They allow users to apply ML-generated force fields within established simulation workflows without manual reconfiguration [31] [32]. |

| High-Quality Training Datasets (e.g., SPICE2) | Chemically diverse collections of molecular structures with energies and forces computed at a high level of quantum mechanical theory. These are used to train the MLIP models to understand atomic interactions [32]. |

| System Topology File | A file that defines the molecules in your system, including atom types, bonds, and other force field parameters. It is essential for defining the system to the simulation software [29]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset and how does it address key limitations in molecular simulations?

OMol25 is a massive, open dataset of over 100 million density functional theory (DFT) calculations designed to train machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). It directly addresses the critical bottleneck in molecular dynamics: the extreme computational cost of achieving quantum chemical accuracy. Traditional DFT calculations, while accurate, demand enormous computing power, making simulations of scientifically relevant molecular systems "impossible... even with the largest computational resources." MLIPs trained on OMol25 can provide predictions of the same caliber but 10,000 times faster, unlocking the ability to simulate large atomic systems that were previously out of reach [33].

Q2: What specific chemical domains does OMol25 cover to ensure its models are generalizable?

The dataset was strategically curated to cover a wide range of chemically relevant areas, ensuring models aren't limited to narrow domains. Its primary focus areas are [33] [34]:

- Biomolecules: Structures from the RCSB PDB and BioLiP2 datasets, including protein-ligand complexes, protein-nucleic acid interfaces, and various protonation states and tautomers.

- Electrolytes: Aqueous and organic solutions, ionic liquids, and molten salts, including clusters and degradation pathways relevant to battery chemistry.

- Metal Complexes: Combinatorially generated structures from a wide range of metals, ligands, and spin states, including reactive species. The dataset includes 83 elements and systems of up to 350 atoms, a tenfold increase in size over many previous datasets [33] [35] [36].

Q3: I need high accuracy for my research on transition metal complexes. What is the quantum chemistry level of theory used for OMol25?

All 100 million calculations in the OMol25 dataset were performed at a consistent and high level of theory: the ωB97M-V functional with the def2-TZVPD basis set [35] [34] [36]. ωB97M-V is a state-of-the-art range-separated meta-GGA functional that avoids many known pathologies of older functionals. The use of a large integration grid and triple-zeta basis set with diffuse functions ensures accurate treatment of non-covalent interactions, anionic species, and gradients [34] [36]. This high and consistent level of theory across such a vast dataset is one of its key differentiators.

Q4: What ready-to-use tools are available to start using OMol25 in my simulations immediately?

To help researchers get started, the Meta FAIR team and collaborators have released several pre-trained models [34]:

- eSEN Models: Available in small, medium, and large sizes, with both direct-force and conservative-force variants. The conservative-force models are generally recommended for better-behaved molecular dynamics and geometry optimizations.

- Universal Model for Atoms (UMA): A foundational model trained not only on OMol25 but also on other open-source datasets (like OC20 and OMat24) covering materials and catalysts. UMA uses a novel Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) architecture to act as a versatile base for diverse downstream tasks [34] [37]. These models are publicly available on platforms like Hugging Face and can be run through various scientific computing interfaces [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: My Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is running very slowly.

Slow MD simulations are a common challenge. The solution depends heavily on the software and hardware you are using. The table below outlines a systematic troubleshooting approach.

Table: Troubleshooting Slow Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Step | Issue / Solution | Technical Commands / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Software | Using non-optimized MD engines. | Switch from a standard engine (e.g., sander in AMBER) to a highly optimized one (e.g., pmemd). A GPU-accelerated version (pmemd.cuda) can provide a 100x or greater speedup [38]. |

| 2. Check GPU Usage | Simulation is not fully leveraging GPU, or GPU is throttling. | Ensure all compatible calculations are offloaded. In GROMACS, use flags like -nb gpu -bonded gpu -pme gpu -update gpu [39]. Monitor GPU temperature (nvidia-smi -l) for thermal throttling. |

| 3. Check System Setup | Poor cooling or dust accumulation in hardware. | Ensure proper airflow in the computer case. Clean heat sinks and fans from dust annually to maintain cooling efficiency [39]. |

Problem 2: My simulation results are physically inaccurate or the simulation is unstable.

This often stems from inaccuracies in the underlying potential energy surface.

- Solution A: Leverage High-Quality MLIPs. Replace traditional force fields with a machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP) trained on a high-quality dataset like OMol25. The pre-trained models offered (e.g., eSEN, UMA) have been shown to achieve "essentially perfect performance" on standard molecular energy benchmarks, providing DFT-level accuracy at a fraction of the cost [34].

- Solution B: Validate Your Workflow. The OMol25 project provides robust public evaluations and benchmarks. Use these to verify that your chosen model performs accurately for the specific chemical tasks you are interested in, such as predicting protein-ligand interaction energies or spin-state gaps [33] [36].

Problem 3: I cannot access sufficient computational resources to train my own ML model from scratch.

The scale of OMol25 makes full model training from scratch challenging for groups without massive GPU clusters.

- Solution: Utilize Transfer Learning. Instead of training a new model, fine-tune one of the existing pre-trained models (like UMA or eSEN) on your smaller, domain-specific dataset. This approach leverages the broad chemical knowledge already encoded in the model and requires significantly less data and compute [34] [37].

OMol25 Dataset & Model Specifications

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of the OMol25 Dataset

| Parameter | Specification | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total DFT Calculations | >100 million [33] [35] | Unprecedented scale for model training. |

| Computational Cost | 6 billion CPU hours [33] | Equivalent to >50 years on 1,000 laptops. |

| Unique Molecular Systems | ~83 million [35] [36] | Vast coverage of chemical space. |

| Maximum System Size | Up to 350 atoms [33] [36] | 10x larger than previous datasets; enables study of biomolecules. |

| Element Coverage | 83 elements (H to Bi) [35] [36] | Includes heavy elements and metals, unlike most organic-focused sets. |

| Level of Theory | ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD [35] [34] | High-level, consistent DFT methodology for reliable data. |

Table 2: Performance of Select Pre-Trained Models on OMol25

| Model Name | Architecture | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN (conserving) | Equivariant Transformer | Conservative forces for stable MD; two-phase training [34]. | Outperforms direct-force counterparts; larger models (eSEN-md, eSEN-lg) show best accuracy [34]. |

| Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) | Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) | Unified model for molecules & materials; trained on OMol25+ other datasets [34] [37]. | Enables knowledge transfer; outperforms single-task models on many benchmarks [34]. |

| MACE & GemNet-OC | Equivariant GNNs | State-of-the-art graph neural networks. | Full performance comparisons reported; used as baselines in the OMol25 paper [35] [36]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Leveraging OMol25 in Research

| Resource | Function | Access / Availability |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Core training data for developing or fine-tuning MLIPs. Provides energies, forces, and electronic properties [35] [36]. | Publicly released to the scientific community [33]. |

| Pre-trained Models (eSEN, UMA) | Ready-to-use neural network potentials for immediate deployment in atomistic simulations, providing near-DFT accuracy [34] [37]. | Available on Hugging Face and other model repositories [34]. |

| ORCA Quantum Chemistry Package | High-performance software used to perform the DFT calculations for the OMol25 dataset [37]. | Commercial software package. |

| Community Benchmarks & Evaluations | Standardized challenges to measure and track model performance on tasks like energy prediction and conformer ranking [33] [36]. | Publicly available to ensure fair comparison and drive innovation. |

Workflow: Accelerating MD with OMol25

The following diagram illustrates the optimized workflow for running molecular dynamics simulations using MLIPs trained on the OMol25 dataset, contrasting it with the traditional, slower approach.

Overcoming Time-Scale Barriers with Enhanced Sampling Methods

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insights into biological systems but are severely limited by insufficient sampling of conformational states. This limitation stems from the rough energy landscapes of biomolecules, which are characterized by many local minima separated by high-energy barriers. These landscapes govern biomolecular motion and often trap conventional MD simulations in non-functional states, preventing access to all relevant conformational substates connected with biological function. Enhanced sampling algorithms have been developed to address this fundamental challenge, enabling researchers to bridge the gap between simulation timescales and biologically relevant phenomena [40].

FAQ: Enhanced Sampling Fundamentals

What is the fundamental "timescale problem" in molecular dynamics? The timescale problem refers to the limitation of standard MD simulations to processes shorter than a few microseconds, making it difficult to study slower processes like protein folding or crystal nucleation and growth. This occurs because biomolecules have rough energy landscapes with many local minima separated by high-energy barriers, causing simulations to get trapped in non-relevant conformations without accessing all functionally important states [40] [41].

Why can't we simply run longer simulations with more computing power? While high-performance computing has expanded MD capabilities, all-atom explicit solvent simulations of biological systems remain computationally prohibitive for reaching biologically relevant timescales (milliseconds and longer). For example, a 23,558-atom system on specialized Anton supercomputers would require several years of continuous computation to achieve 10-second simulations, making this approach impractical for most research institutions [42].

What are collective variables and why are they important for enhanced sampling? Collective variables (CVs) are low-dimensional descriptors that capture the slowest modes of a system, such as distances, angles, or coordination numbers. Good CVs are essential for many enhanced sampling methods like metadynamics, as they describe the reaction coordinates connecting different metastable states. The quality of CVs directly impacts sampling efficiency, with poor CVs leading to suboptimal performance [41].

How do I choose the right enhanced sampling method for my system? Method selection depends on biological and physical system characteristics, particularly system size. Metadynamics and replica-exchange MD are most adopted for biomolecular dynamics, while simulated annealing suits very flexible systems. Recent approaches combine multiple methods for greater effectiveness, such as merging metadynamics with stochastic resetting [40] [41].

Troubleshooting Common Enhanced Sampling Issues

Poor Convergence in Replica-Exchange Simulations

Symptoms: Low exchange rates between replicas, failure to achieve random walks in temperature space, or incomplete sampling of relevant conformational states.

Solutions:

- Optimize temperature distribution: Ensure maximum temperature is slightly above where folding enthalpy vanishes, avoiding excessively high temperatures that reduce efficiency [40].

- Consider REMD variants: For improved convergence, try reservoir REMD (R-REMD) or Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD) when temperature REMD proves insufficient [40].

- Adjust system parameters: Implement multiplexed-REMD (M-REMD) with multiple replicas per temperature level for better sampling in shorter simulation times, though this increases computational cost [40].

Typical Performance Metrics: Table 1: Replica-Exchange MD Performance Indicators

| Metric | Optimal Range | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Replica exchange rate | 20-30% | Adjust temperature spacing if outside range |

| Random walk in temperature space | Uniform distribution across all temperatures | Increase simulation time or adjust temperatures |

| Folding/unfolding transitions | Multiple transitions per replica | Extend simulation or optimize temperature distribution |

Inefficient Barrier Crossing in Metadynamics

Symptoms: Slow exploration of configuration space, bias potential accumulating without driving transitions, or incomplete free energy surface exploration.

Solutions:

- Refine collective variables: Select CVs that better distinguish between metastable states and describe the reaction pathway [41].

- Combine with stochastic resetting: Add resetting procedures where simulations are periodically restarted from initial conditions, particularly effective for flattening free energy landscapes [41].

- Adjust bias deposition parameters: Modify the rate and shape of Gaussian potentials deposited in metadynamics to balance exploration and accuracy [40].

Recent Advancement: The combination of metadynamics with stochastic resetting has demonstrated acceleration of up to two orders of magnitude for systems with suboptimal CVs, such as alanine tetrapeptide and chignolin folding simulations [41].

System Size Limitations in Enhanced Sampling

Symptoms: Performance degradation with increasing system size, inability to apply methods to large biomolecular complexes, or excessive computational costs.

Solutions:

- Implement parallel CV-driven hyperdynamics: This approach accelerates multiple reactions simultaneously in large systems by employing rate control and independent bias potentials for different regions [43].

- Use generalized simulated annealing (GSA): Particularly effective for large macromolecular complexes at relatively low computational cost compared to other methods [40].

- Apply local hyperdynamics: Decompose the system into local domains with different bias potentials for each subdomain [43].

Performance Data: Parallel collective variable-driven hyperdynamics has achieved accelerations of 10^7, reaching timescales of 100 milliseconds for carbon diffusion in iron bicrystal systems [43].

Method Selection Guide

Table 2: Enhanced Sampling Method Comparison

| Method | Mechanism | Best For | System Size | Key Parameters | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) | Parallel simulations at different temperatures with state exchanges | Biomolecular folding, peptide dynamics, protein conformational changes | Small to medium | Temperature range, number of replicas, exchange frequency | High (scales with replica count) |

| Metadynamics | Fills free energy wells with "computational sand" via bias potential | Protein folding, molecular docking, conformational changes | Small to medium | Collective variables, bias deposition rate, Gaussian height | Medium to high |

| Simulated Annealing | Gradual temperature decrease to find global minimum | Very flexible systems, structure prediction | All sizes (GSA for large complexes) | Cooling schedule, initial/final temperatures | Low to medium |

| Parallel CVHD | Multiple independent bias potentials applied simultaneously | Large systems, parallel reaction events, materials science | Medium to very large | Number of CVs, acceleration rate control, synchronization | High (but efficient for large systems) |

| Metadynamics + Stochastic Resetting | Bias potential with periodic restarting from initial conditions | Systems with poor CVs, flat landscapes | Small to medium | Resetting frequency, CV selection, bias parameters | Medium |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics Setup

Application: Enhanced sampling of protein conformational states [40]

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Begin with solvated protein system using standard preparation protocols.

- Replica Parameters: Determine optimal temperature distribution using the formula:

- Number of replicas: 24-48 for small proteins

- Temperature spacing: Aim for 20-30% exchange probability

- Maximum temperature: Slightly above where folding enthalpy vanishes

- Simulation Parameters:

- Integration timestep: 2 fs

- Exchange attempt frequency: Every 1-2 ps

- Simulation length: Minimum 50-100 ns per replica

- Analysis: Monitor replica exchange rates, random walks in temperature space, and convergence of thermodynamic properties.

Protocol: Metadynamics with Stochastic Resetting

Application: Accelerated sampling with suboptimal collective variables [41]

Methodology:

- Collective Variable Selection: Identify CVs that approximate reaction coordinates, even if suboptimal.

- Resetting Parameters:

- Resetting time distribution: Poisson process with mean reset time τ

- Initial conditions: Resample from identical distribution

- Metadynamics Parameters:

- Bias factor: System-dependent (typically 10-30)

- Gaussian width: Adjusted to CV fluctuations

- Gaussian height: 0.1-1.0 kJ/mol

- Simulation Workflow:

- Run metadynamics with periodic resetting

- Employ kinetics inference procedure for mean first-passage time estimation

- Validate with known system properties

Protocol: Parallel Collective Variable-Driven Hyperdynamics

Application: Large systems with multiple simultaneous reactions [43]

Methodology:

- System Decomposition: Divide system into subsets based on spatial or chemical criteria.

- CV Definition: Employ bond distortion function for each bond pair i:

- χi = max(0, (ri - rimin)/rimin)

- where ri is current bond length, rimin is starting point

- Parallel Implementation:

- Assign independent CVs to different system regions

- Apply bias potentials simultaneously with rate control

- Synchronize acceleration rates across subsets

- Validation: Compare accelerated dynamics with known diffusion coefficients or reaction rates.

Enhanced Sampling Relationships and Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Enhanced Sampling

| Tool/Software | Function | Compatible Methods | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLUMED 2 | Enhanced sampling plugin | Metadynamics, REMD, Bias-Exchange | Collective variable analysis, versatile bias potentials |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics engine | REMD, Metadynamics | High performance, extensive method implementation |

| NAMD | Scalable MD simulation | Metadynamics, REMD | Parallel efficiency, large system capability |

| AMBER | MD package | REMD variants | Biomolecular focus, force field compatibility |

| Structure-Based Models | Coarse-grained potentials | Generalized ensemble methods | Computational efficiency, millisecond timescales |

| OpenMM | GPU-accelerated toolkit | Custom enhanced sampling | High throughput, flexible API |

| LAMMPS | MD simulator | Parallel CVHD | Materials science focus, extensibility |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common ML-IAP-Kokkos Integration Issues

PyTorch Model Loading Failures

Problem: LAMMPS fails to load your PyTorch model file (.pt), often hanging or crashing during the pair_style mliap unified command without clear error messages.

Diagnosis and Solution: This is a known compatibility issue between recent PyTorch versions and LAMMPS's model loading mechanism. PyTorch has become more restrictive about loading "pickled" Python classes for security reasons [44].

Resolution: Set the following environment variable before running LAMMPS to enable loading of class-based models [17] [44]:

Alternatively, for temporary session-only setting:

Important Security Note: Only use this workaround with trusted .pt files, as it re-enables arbitrary code execution during model loading [17].

GPU Compatibility and Multi-GPU Errors

Problem: The error "ERROR: Running mliappy unified compute_forces failure" occurs when running on a different GPU type than the one used for training [45].

Diagnosis and Solution: This typically indicates a hardware architecture mismatch. The model or LAMMPS build may be optimized for specific GPU compute capabilities.

Resolution:

- Consistent KOKKOS_ARCH: Ensure LAMMPS is compiled with the correct

KOKKOS_ARCHflag for your target GPU [45]. - Rebuild for Target Architecture: If moving between different GPU architectures (e.g., from NVIDIA V100 to A100), rebuild LAMMPS with the appropriate

KOKKOS_ARCHsetting. - Model Portability: Retrain or convert models specifically for target GPU architectures when maximum performance is required.

Performance Scaling Issues in Multi-GPU Setups

Problem: Simulation performance does not scale efficiently when increasing the number of GPUs.

Diagnosis and Solution: This often relates to inefficient data distribution and ghost atom handling across GPU boundaries.

Optimization Strategies:

- Ghost Atom Reduction: Utilize the communication hooks in the ML-IAP-Kokkos interface to minimize ghost atom transfers [46].

- Neighbor List Tuning: Adjust the neighbor list cutoff and update frequency in LAMMPS to balance communication and computation.

- Batch Processing: Ensure your

compute_forcesimplementation efficiently batches operations for all local atoms rather than processing individually [17].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Quick Reference

| Problem | Symptoms | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Model Loading | Crash on pair_style command |

Set TORCH_FORCE_NO_WEIGHTS_ONLY_LOAD=1 [17] [44] |

| GPU Compatibility | compute_forces failure on different GPU |

Recompile with correct KOKKOS_ARCH [45] |

| Performance Scaling | Poor multi-GPU efficiency | Optimize ghost atoms and neighbor lists [46] |

| Memory Issues | Out-of-memory errors on large systems | Enable cuEquivariance for memory-efficient models [46] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the exact software and hardware requirements for using ML-IAP-Kokkos with PyTorch models?

A: The core requirements include [17]:

- LAMMPS: September 2025 release or later, compiled with Kokkos, MPI, ML-IAP, and Python support

- PyTorch: Compatible version (typically ≥1.10)

- Python: 3.8 or later with Cython (for custom model development)

- GPUs: NVIDIA GPUs with compute capability 7.0 or higher (Volta architecture or newer)

- Optional: cuEquivariance support for additional acceleration of equivariant models

Q2: How does the data flow work between LAMMPS and my PyTorch model during simulation?

A: The data flow follows a specific pattern that's crucial to understand for debugging and optimization [17]:

- LAMMPS Preparation: LAMMPS prepares neighbor lists and atom data, separating atoms into "local" (active) and "ghost" (periodic images/other processors) atoms

- Data Passing: The ML-IAP-Kokkos interface passes this data to your Python class through the

compute_forcesfunction - Model Inference: Your PyTorch model processes the atomic environment data

- Force/Energy Return: Your model returns energies and forces for local atoms

- LAMMPS Integration: LAMMPS integrates these forces into the molecular dynamics simulation

Table 2: Data Structure Components Passed from LAMMPS to PyTorch Model

| Data Field | Description | Example Values |

|---|---|---|

data.ntotal |

Total atoms (local + ghost) | 6 |

data.nlocal |

Local atoms to be updated | 3 |

data.iatoms |

Indices of local atoms | [0, 1, 2] |

data.elems |

Atomic species of all atoms | [2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1] |

data.npairs |

Neighbor pairs within cutoff | 4 |

data.pair_i, data.pair_j |

Atom indices for each pair | (0, 5), (0, 1), etc. |

data.rij |

Displacement vectors between pairs | [-1.1, 0., 0.], [1., 0., 0.], etc. |

Q3: What performance benefits can I realistically expect compared to traditional force fields?

A: Benchmark results demonstrate significant performance improvements [46]:

- HIPPYNN Models: Showed substantial speed improvements when scaling across up to 512 NVIDIA H100 GPUs

- MACE Integration: The ML-IAP-Kokkos plugin provided superior speed and memory efficiency compared to previous implementations

- Multi-Node Scaling: Efficient strong scaling demonstrated on exascale systems including OLCF Frontier, ALCF Aurora, and NNSA El Capitan [47]

The key advantage comes from reduced communication overhead and optimized message-passing capabilities that minimize redundant computations, particularly for large systems where traditional force fields become communication-bound.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Simple Test Model

Step-by-Step Methodology for Protocol Validation

Follow this exact protocol to validate your ML-IAP-Kokkos setup with a minimal test case before implementing complex models [17]:

Step 1: Environment Preparation

Step 2: Implement a Diagnostic Model Class

Create simple_diagnostic.py:

Step 3: Create Minimal Molecular System

Create test_system.pos:

Step 4: Execute Validation Simulation

Create validate.in:

Execute with:

Step 5: Output Validation Expected output should show:

- 3 local atoms and 3 ghost atoms (total: 6)

- 4 neighbor pairs within cutoff

- Clear mapping of atomic indices and displacement vectors

This protocol validates the complete data pipeline from LAMMPS to your PyTorch model and back.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components

Table 3: Essential Software Components for ML-IAP-Kokkos Integration

| Component | Function | Installation Source |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS with Kokkos | Main MD engine with performance-portable backend | https://github.com/lammps/lammps [17] |

| ML-IAP-Kokkos Interface | Bridge between LAMMPS and PyTorch models | Bundled with LAMMPS (Sept 2025+) [17] |

| PyTorch (GPU) | ML framework for model inference | pytorch.org (with CUDA support) |

| MLMOD-PYTORCH | Additional ML methods for data-driven modeling | https://github.com/atzberg/mlmod [48] |

| USER-DEEPMD | Alternative DeePMD-kit ML potentials | LAMMPS plugins collection [48] |

| PLUMED | Enhanced sampling and free energy calculations | https://www.plumed.org [48] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: ML-IAP-Kokkos Integration Workflow and Troubleshooting Points

This workflow diagram illustrates the complete data pathway from LAMMPS molecular dynamics simulations through the ML-IAP-Kokkos interface to PyTorch model execution and back. Critical troubleshooting points are highlighted where common errors typically occur, particularly during model loading and GPU force computation. The data structure components shown in the green subgraph represent the exact information passed from LAMMPS to your PyTorch model, which is essential for debugging custom model implementations.

FAQs: Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and Solubility

Q1: What are MLIPs and how do they fundamentally accelerate molecular simulations? Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are models that parameterize the potential energy surface of an atomic system as a function of local environment descriptors using machine learning techniques [49]. They enable accurate simulations of materials at scales that are much larger than those accessible by purely quantum mechanical (ab initio) methods, which are computationally prohibitive for many drug discovery applications [49]. By providing a way to compute energies and forces with near-ab initio accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost, MLIPs make long-time-scale or large-system molecular dynamics (MD) simulations feasible for pre-screening drug candidates [49].

Q2: Why is predicting drug solubility particularly challenging for computational methods? Solubility is an inherently difficult mesoscale phenomenon to simulate [50]. It depends on complex factors like crystal polymorphism and the ionization state of the molecule in a nonlinear way [50]. Furthermore, experimental solubility data itself is often noisy and inconsistent, with inter-laboratory measurements for the same compound sometimes varying by 0.5 to 1.0 log units, setting a practical lower limit (the aleatoric limit) on prediction accuracy [51]. Full first-principles simulation is too costly for routine use in high-throughput workflows [50].

Q3: How does the integration of MLIPs with enhanced sampling techniques improve solubility prediction? While the provided search results do not detail specific enhanced sampling techniques, the core strength of MLIPs is enabling sufficiently long and accurate MD simulations to properly sample the relevant molecular configurations and interactions that dictate solubility. This could include processes like solute dissociation from a crystal or its stabilization in a solvent environment. By making such simulations computationally tractable, MLIPs provide the necessary data to understand and predict solubility behavior [49].

Q4: My MD simulations are running progressively slower. Could this be related to the potential functions? Performance degradation in MD simulations can stem from various sources. While the search results do not directly link this to MLIPs, they document cases where simulations slow down over time [52]. One reported issue involved a specific GROMACS version where simulation times increased for subsequent runs, a problem that was resolved by restarting the computer, suggesting a resource management issue rather than a problem with the potential function itself [52]. It is always recommended to profile your code and check for hardware issues like GPU overheating [52].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common MLIP and Simulation Issues

| Issue & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Solubility Prediction Accuracy | • Training data does not cover the relevant chemical/structural space.• Model is trained on aqueous solubility but used for organic solvents.• Predictions are at the limit of experimental data uncertainty (0.5-1.0 log S) [51]. | • Apply stratified sampling (e.g., DIRECT sampling) to ensure robust training set coverage [49].• Use a model specifically designed for the solvent type (e.g., FASTSOLV for organic solvents) [51].• Compare error to known aleatoric limit of experimental data [51]. |

| MD Simulation Performance Degradation | • GPU memory leaks or overheating leading to thermal throttling [52].• Inefficient file I/O or logging settings.• Suboptimal workload balancing between CPU and GPU. | • Monitor GPU temperature and throttle reasons using nvidia-smi [52].• Simplify the system (e.g., halve its size) as a test [52].• Restart the computer or software to clear cached memory [52]. |

| MLIP Fails to Generalize to New Molecules | • The model is extrapolating to chemistries or structures absent from its training data.• Inadequate active learning during training. | • Use a universal potential (e.g., M3GNet-UP) pre-trained on diverse materials [49].• Implement an active learning loop where the MLIP identifies uncertain structures for iterative augmentation of the training set [49]. |