Adaptive Introgression: The Evolutionary Force Accelerating Species Adaptation and Its Biomedical Implications

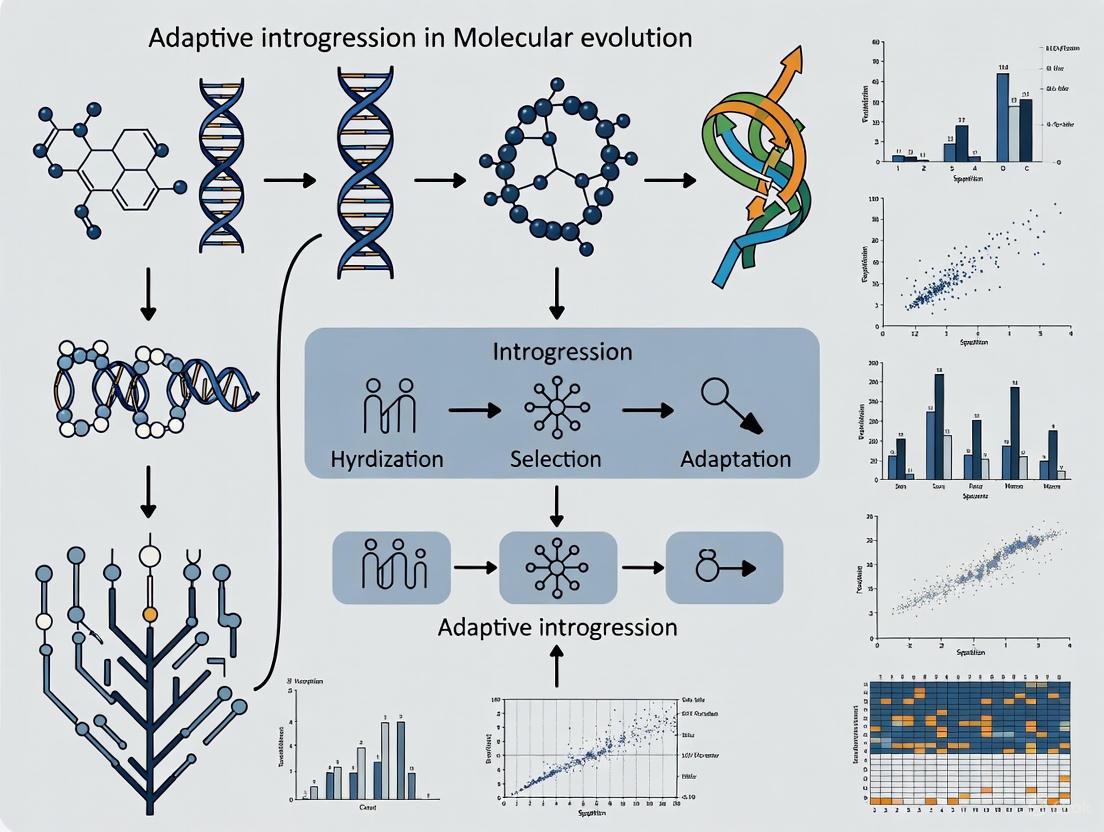

This comprehensive review explores adaptive introgression as a significant evolutionary mechanism, synthesizing recent genomic evidence across diverse taxa.

Adaptive Introgression: The Evolutionary Force Accelerating Species Adaptation and Its Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores adaptive introgression as a significant evolutionary mechanism, synthesizing recent genomic evidence across diverse taxa. We examine the paradigm shift from viewing introgression as a maladaptive process to recognizing its role in rapid adaptation, highlighting advanced detection methodologies like convolutional neural networks and comparative performance evaluations. The article addresses key challenges in distinguishing adaptive introgression from neutral processes and presents compelling case studies from human evolution, plants, and other organisms. For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, we elucidate how archaic adaptive introgression in modern humans influences reproductive genes, disease susceptibility, and developmental pathways, offering novel insights for therapeutic target identification and evolutionary medicine.

From Genetic Swamping to Evolutionary Rescue: Redefining Adaptive Introgression

Introgression, the permanent incorporation of alleles from one population or species into another through hybridization and repeated backcrossing, has undergone a profound conceptual transformation in evolutionary biology [1]. Historically regarded as a primarily deleterious or homogenizing force that counteracted adaptation and divergence, introgression is now recognized as a potent evolutionary mechanism that can accelerate adaptation, introduce novel genetic variation, and rescue populations from environmental challenges [2]. This paradigm shift has been driven largely by the genomic revolution, which has provided researchers with unprecedented tools to detect and characterize introgressed fragments across diverse taxa [3]. The understanding of adaptive introgression—the process by which introgressed alleles confer a fitness advantage and spread under positive selection—has fundamentally altered our perspective on how organisms evolve in response to selective pressures [4] [2].

This whitepaper examines the historical context, methodological advances, and modern understanding of introgression within the framework of its evolutionary significance, with particular relevance for biomedical and pharmacological research. The growing evidence that adaptive introgression has contributed to functional adaptations in immunity, reproduction, and environmental adaptation in humans and other organisms underscores its importance as a source of evolutionarily relevant genetic variation [5] [4].

Historical Trajectory: From Maladaptive to Adaptive

The Traditional View of Introgression as Evolutionary Noise

The historical perspective in evolutionary biology largely viewed introgression as a maladaptive process or an "evolutionary misfortune" that potentially hindered divergence through several mechanisms:

- Genetic Homogenization: Introgression was thought to counteract local adaptation by introducing foreign alleles outside the local adaptive range [2].

- Genetic Swamping: Concerns existed that gene flow from abundant species could lead to outbreeding depression and replacement of local genotypes in species with smaller population sizes [2].

- Reproductive Interference: Introgression was viewed as potentially disrupting co-adapted gene complexes and well-adapted genomes [2].

This perspective was largely shaped by the biological species concept, which emphasized reproductive isolation as a cornerstone of species integrity, and by limited analytical tools that struggled to distinguish introgressed alleles from other forms of shared genetic variation [4].

The Genomic Revolution and Paradigm Shift

The advent of accessible whole-genome sequencing and sophisticated computational methods catalyzed a fundamental reassessment of introgression's evolutionary role [2] [3]. Several key realizations emerged:

- Widespread Occurrence: Genomic studies revealed that introgression is pervasive across diverse taxa, from bacteria to mammals, with varying levels of introgression detected across lineages [6] [2].

- Adaptive Potential: Evidence accumulated showing that introgression could provide beneficial alleles that spread rapidly through populations, sometimes enabling adaptation more quickly than de novo mutation [2].

- Functional Significance: Researchers identified specific introgressed alleles contributing to adaptive traits in various organisms, from herbivore resistance in sunflowers to high-altitude adaptation in humans [7] [4].

This paradigm shift represents a more nuanced understanding where introgression is recognized as one of several evolutionary forces—including divergence, genetic drift, and selection—that interact in complex ways to shape genomes [2].

Table 1: Key Milestones in the Understanding of Introgression

| Time Period | Predominant View | Methodological Focus | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1990s | Largely detrimental process | Morphological analysis, limited genetic markers | Inability to distinguish introgression from shared ancestry |

| 1990s-2000s | Debate over prevalence and impact | Multi-locus sequence typing, early phylogenetic methods | Limited genomic coverage, challenging statistical inference |

| 2010s-Present | Recognition as adaptive evolutionary force | Whole-genome sequencing, sophisticated statistical models | Integration of complex demographic histories, functional validation |

Methodological Evolution: Detecting and Analyzing Introgression

Statistical Approaches for Introgression Detection

The accurate identification of introgressed regions presents significant challenges, primarily because introgressed sequences must be distinguished from ancestral genetic variation shared due to incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) [4]. Several statistical frameworks have been developed to address this challenge:

Summary Statistics-Based Methods leverage patterns of genetic variation to identify introgression:

- Patterson's D Statistic (ABBA-BABA Test): Measures excess sharing of derived alleles between an outgroup and two ingroup populations, identifying asymmetrical gene flow that violates a strict branching phylogeny [4].

- f4-ratio and fD Statistics: Extensions of Patterson's D that provide additional power to quantify introgression proportions and test specific phylogenetic relationships [4].

- S* and Related Methods: Leverage patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype structure to identify introgressed tracts, exploiting the expectation that introgressed segments will exhibit longer haplotypes and distinct LD patterns than background regions [4].

Phylogenetic Incongruence Methods identify introgression through discordance between gene trees and species trees:

- Gene Tree-Species Tree Discordance: Systematic inconsistencies between individual gene genealogies and the expected species phylogeny can indicate introgression, particularly when coupled with tests of sequence similarity [6].

- Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG) Methods: Models the joint effects of recombination, ILS, and introgression on genealogical history, providing a powerful framework for detecting introgressed segments while accounting for other sources of genealogical discordance [5].

Advanced Modeling and Machine Learning Approaches

Recent methodological innovations have substantially improved the detection and characterization of introgression:

Probabilistic Modeling Frameworks explicitly incorporate evolutionary processes to infer introgression:

- Multispecies Coalescent with Introgression: Extends the multispecies coalescent to include migration/introgression events, allowing joint modeling of ILS and gene flow [7].

- Branching Process Models: Quantify stochastic introgression processes, particularly useful for modeling rare hybridization events and demographic stochasticity in small hybrid populations [1].

- Brownian Motion on Phylogenetic Networks: Models quantitative trait evolution on networks with introgression, predicting how introgression affects trait covariances among species [7].

Supervised Learning Approaches represent an emerging frontier in introgression detection:

- Semantic Segmentation Frameworks: Frame introgression detection as a classification task where genomic regions are labeled as introgressed or not based on patterns of genetic variation [3].

- Feature-Based Classification: Utilize summary statistics and population genetic parameters as input features for machine learning classifiers to identify introgressed loci [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Methodological Approaches for Introgression Detection

| Method Category | Key Example Methods | Primary Applications | Key Assumptions/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary Statistics | Patterson's D, f4-statistics, S* | Genome-wide scans, testing for introgression | Requires reference populations, sensitive to demographic history |

| Phylogenetic Methods | Gene tree discordance, ARG inference | Deep evolutionary introgression, non-model organisms | Computationally intensive, requires multiple genomes per species |

| Probabilistic Models | MSci, D-statistics, Bayesian methods | Parameter estimation, model comparison | Model misspecification risk, computational complexity |

| Machine Learning | Semantic segmentation, feature-based classification | High-throughput screening, complex genomes | Training data requirements, interpretability challenges |

Experimental and Analytical Workflows

The modern detection and validation of adaptive introgression typically follows a multi-stage workflow that integrates population genetic inference with functional validation.

Genomic Data Collection and Quality Control

The foundation of any introgression analysis is high-quality genomic data from relevant populations and, when available, archaic or ancestral reference genomes:

- Modern Population Sequencing: Whole-genome sequencing of diverse populations from relevant geographic regions, with particular attention to populations with known or suspected historical admixture [5].

- Archaic Genome Sequencing: High-coverage sequencing of archaic hominins (Neanderthal, Denisovan) or other ancestral reference populations for identifying introgressed fragments [5] [4].

- Variant Calling and Phasing: Accurate identification of genetic variants and reconstruction of haplotypes, which is crucial for detecting introgressed segments through linkage disequilibrium patterns [5].

Statistical Detection of Introgressed Fragments

Multiple complementary methods are typically applied to identify putative introgressed regions:

- Population Differentiation Analysis: Identification of regions with unusual patterns of differentiation between populations that may indicate introgression [5].

- Haplotype-Based Methods: Detection of long, distinct haplotypes in recipient populations that closely match donor populations, using methods such as SPrime [5].

- Divergence-Based Approaches: Calculation of sequence divergence between test haplotypes and putative archaic sources, with introgressed haplotypes showing unexpectedly low divergence to archaic genomes compared to other modern human haplotypes [4].

Tests for Adaptive Selection

Once introgressed regions are identified, multiple selection tests are applied to detect signatures of adaptive introgression:

- Extended Haplotype Homozygosity (EHH): Identifies long haplotypes at unexpectedly high frequency, indicating rapid increase in allele frequency due to positive selection [5].

- Population Differentiation (FST): Measures differences in allele frequencies between populations, with unusually high FST values potentially indicating local adaptation [5].

- Relate Selection Scans: Uses ancestral recombination graphs to infer time-resolved selection signals, identifying variants under recent positive selection [5].

- Frequency-Based Tests: Unusually high allele frequencies of introgressed alleles in specific populations may suggest adaptive benefits [5].

Biological Significance and Functional Impacts

Case Studies of Adaptive Introgression in Humans

Research over the past decade has identified numerous examples of adaptive introgression in modern human populations, providing concrete examples of its functional significance:

Reproductive Gene Adaptations: A 2025 study identified 118 reproductive genes in modern humans showing evidence of archaic adaptive introgression, with 327 archaic alleles genome-wide significant for various traits [5]. Key findings include:

- Three Positively Selected Core Haplotypes: The PNO1-ENSG00000273275-PPP3R1 region in East Asian populations, the AHRR segment in Finnish populations, and the FLT1 region in Peruvian populations showed strong signatures of positive selection [5].

- Regulatory Impact: Over 300 archaic variants were identified as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) regulating 176 genes, with 81% of archaic eQTLs overlapping core haplotype regions and affecting genes expressed in reproductive tissues [5].

- Clinical Associations: Several adaptively introgressed genes were enriched in developmental and cancer pathways, with associations to endometriosis, preeclampsia, and embryo development [5].

- Protective Alleles: Archaic alleles overlapping an introgressed segment on chromosome 2 were found to be protective against prostate cancer [5].

Immunity and Environmental Adaptations: Multiple studies have documented adaptive introgression in genes related to immune function and environmental adaptation:

- Pathogen Defense: Introgressed Neanderthal alleles have been identified in human immune genes, potentially providing enhanced defense against Eurasian pathogens encountered by modern humans after leaving Africa [4].

- High-Altitude Adaptation: Tibetan populations carry an introgressed Denisovan haplotype in the EPAS1 gene, which confers adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia [4].

- Skin and Hair Phenotypes: Keratin genes related to skin and hair morphology show evidence of archaic introgression, possibly adaptations to non-African environments [5].

Beyond Humans: Introgression Across the Tree of Life

Adaptive introgression has been documented across diverse taxonomic groups, demonstrating its broad evolutionary significance:

In Bacteria: Despite being asexual organisms, bacteria engage in homologous recombination that can facilitate introgression between distinct species [6]:

- Variable Introgression Levels: Bacterial genera show an average of 2% introgressed core genes, with up to 14% in Escherichia-Shigella [6].

- Species Border Maintenance: Contrary to expectations, introgression does not necessarily blur species borders in bacteria, with most species remaining clearly delineated based on core genome phylogenies [6].

In Plants and Other Eukaryotes: Studies in wild tomatoes (Solanum) and other plants have demonstrated how introgression can shape quantitative trait variation [7]:

- Gene Expression Impact: Whole-transcriptome analyses in Solanum ovules revealed patterns of expression similarity consistent with historical introgression, particularly in sub-clades with higher introgression rates [7].

- Trait Convergence: Introgression can generate apparently convergent patterns of evolution when averaged across thousands of quantitative traits [7].

Table 3: Functional Categories of Adaptively Introgressed Genes in Humans

| Functional Category | Example Genes/Regions | Putative Adaptive Function | Source Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproduction | PGR, AHRR, FLT1 | Pregnancy maintenance, fertility enhancement, embryo development | Neanderthal, Denisovan |

| Immunity | Multiple immune genes | Defense against novel pathogens | Neanderthal |

| High-Altitude Adaptation | EPAS1 | Hypoxia response, oxygen metabolism | Denisovan |

| Skin and Hair Morphology | Keratin genes | Adaptation to non-African environments | Neanderthal |

| Cancer-Related | Chromosome 2 region | Protection against prostate cancer | Archaic |

Modern introgression research relies on a sophisticated suite of computational tools, datasets, and analytical resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Introgression Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Datasets | 1000 Genomes Project, gnomAD, UK Biobank | Reference population data | Provides allele frequency data across diverse populations |

| Archaic Genomes | Altai Neanderthal, Vindija Neanderthal, Denisova | Reference archaic sequences | Essential for identifying archaic-derived fragments |

| Detection Software | SPrime, AdmixTools, ARCHIE | Statistical detection of introgression | Each has strengths for specific introgression scenarios |

| Selection Tests | RELATE, CLUES, SWIF(r) | Identifying selection signatures | Can detect both recent and ancient selection |

| Functional Annotation | ANNOVAR, Ensembl VEP, GTEx | Functional consequence prediction | Determines potential impact of introgressed variants |

| Visualization Tools | UCSC Genome Browser, IGV | Genomic data visualization | Critical for manual inspection of candidate regions |

Implications for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

The growing understanding of adaptive introgression has significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development:

Evolutionary-Informed Disease Gene Discovery

- Variant Prioritization: Introgression maps can help prioritize functionally relevant variants in disease-associated regions, particularly when archaic alleles show signatures of positive selection [5].

- Population-Specific Risk Variants: Adaptively introgressed alleles may contribute to population-specific disease risk or protection, as demonstrated by the prostate cancer-protective haplotype on chromosome 2 [5].

- Pleiotropy Assessment: Recognizing that adaptively introgressed alleles may have conferred historical advantages while contributing to modern disease risk (antagonistic pleiotropy) [5].

Therapeutic Target Identification and Validation

- Pathway Insights: Introgressed regions enriched for developmental and cancer pathways highlight biologically significant networks that may represent promising therapeutic targets [5].

- Functional Validation: eQTL effects of introgressed variants provide direct evidence of regulatory function, supporting the biological importance of associated genomic regions [5].

- Comparative Genomics: Introgressed regions with evidence of positive selection in humans may inform animal model development and preclinical studies.

The paradigm shift in understanding introgression—from evolutionary noise to significant adaptive mechanism—has fundamentally transformed evolutionary biology and increasingly informs biomedical research. The integration of sophisticated statistical methods, large-scale genomic datasets, and functional validation approaches has revealed the profound impact of historical introgression events on modern human biology and disease. For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, acknowledging and investigating the contributions of adaptively introgressed sequences provides valuable insights for understanding population-specific disease risks, identifying therapeutic targets, and interpreting the functional significance of genetic variation. As methodological advances continue to refine our ability to detect and characterize introgression events, particularly through probabilistic modeling and machine learning approaches, our understanding of this important evolutionary process will continue to deepen, offering new opportunities for translating evolutionary insights into clinical applications.

Introgression, the permanent incorporation of genetic material from one population or species into another through hybridization and repeated backcrossing, represents a fundamental evolutionary process with significant consequences for adaptation and biodiversity [8] [9]. Historically regarded primarily as a homogenizing force that could swamp local adaptations, introgression is now recognized as a complex phenomenon with outcomes spanning from highly beneficial to decidedly deleterious [2]. This paradigm shift has been largely driven by genomic studies revealing that introgression can serve as a critical source of evolutionary innovation, allowing populations to rapidly acquire adaptive traits without waiting for de novo mutations [2]. Understanding the spectrum of introgression outcomes—adaptive, neutral, and maladaptive—is therefore essential for comprehending how species evolve and adapt to changing environments, with particular relevance for fields ranging from conservation biology to agricultural science and biomedical research [8] [5].

Core Definitions and Evolutionary Implications

Adaptive Introgression

Adaptive introgression refers to the natural transfer of genetic material through interspecific breeding and backcrossing of hybrids with parental species, followed by selection on introgressed alleles that increases the fitness of the recipient population [2]. This process allows for the direct acquisition of beneficial alleles that have already been tested by selection in the donor population, potentially enabling more rapid adaptation than waiting for new mutations to arise [8] [2]. The "adaptive" qualification specifically requires that the introgressed variant confers a selective advantage, leading to its increase in frequency and eventual potential fixation in the recipient population [9]. For example, modern humans acquired immune-related genes and high-altitude adaptations through archaic introgression from Neanderthals and Denisovans, while crop plants frequently introgress disease resistance genes from their wild relatives [8] [5].

Neutral Introgression

Neutral introgression occurs when introgressed alleles have no discernible phenotypic or physiological consequences that affect the fitness of the recipient lineage [2]. These alleles are not subject to selection—either positive or negative—and their population dynamics are governed primarily by genetic drift [2]. The frequency of neutral introgressed alleles may fluctuate randomly across generations, and they may eventually be lost from the population or, less commonly, reach fixation through random sampling processes [2]. Most introgressed sequences are expected to be neutral, as they occur in genomic regions not involved in fitness-related traits [10].

Maladaptive Introgression

Maladaptive introgression describes the incorporation of genetic material that reduces the fitness or survival of the recipient evolutionary lineage in its environment [2]. This can occur through several mechanisms, including the introduction of alleles that are intrinsically deleterious, the disruption of coadapted gene complexes, or the dilution of locally adapted genotypes [8] [2]. In severe cases, maladaptive introgression can lead to genetic swamping, where gene flow from abundant populations replaces local genotypes, potentially causing outbreeding depression or even extinction [8] [2]. The presence of introgression deserts—genomic regions largely devoid of introgressed material—in many species provides evidence for widespread purifying selection against maladaptive introgressed alleles [5].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Introgression Types

| Feature | Adaptive Introgression | Neutral Introgression | Maladaptive Introgression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fitness Effect | Increases fitness | No effect on fitness | Decreases fitness |

| Population Dynamics | Maintained by positive selection | Governed by genetic drift | Removed by purifying selection |

| Frequency Pattern | Increases to high frequency, potentially to fixation | Fluctuates randomly | Usually maintained at low frequency or eliminated |

| Genomic Signature | Selective sweeps, high-frequency archaic segments [5] | Distribution follows neutral expectations | Introgression deserts [5] |

| Evolutionary Impact | Rapid adaptation, evolutionary rescue [2] | Increases genetic diversity without adaptive consequence | Genetic load, outbreeding depression, potential extinction [8] |

| Detection Methods | Selection tests (XP-CLR, Relate), EHH, FST [5] [11] | Ancestry inference, demographic modeling | Reduction in ancestry proportions, association with fitness defects |

The Genomic Landscape of Introgression Outcomes

Genomic studies reveal that introgression outcomes are not uniformly distributed across the genome but instead form a distinctive landscape shaped by the interaction between selection and gene flow [10]. While adaptive introgression appears to be common, most introgressed variation is actually selected against throughout much of the genome [10]. This creates a mosaic pattern where islands of adaptive introgression are separated by regions dominated by neutral or maladaptive introgression. The distribution of these outcomes is influenced by factors such as recombination rate, local genomic architecture, and the strength and form of selection [10].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between different introgression types and their fitness consequences:

Methodological Framework for Detection and Analysis

Genomic Detection Workflows

Identifying and classifying introgression types requires integrated genomic approaches that combine population genetic statistics, demographic modeling, and functional validation. The following workflow outlines the primary steps in detecting and distinguishing different forms of introgression:

Performance of Detection Methods

Different statistical methods show varying performance in detecting adaptive introgression depending on evolutionary scenarios. Recent evaluations of three prominent methods (VolcanoFinder, Genomatnn, and MaLAdapt) and the Q95(w, y) summary statistic reveal important considerations for researchers [11].

Table 2: Method Performance for Adaptive Introgression Detection

| Method | Optimal Scenario | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| VolcanoFinder | Human evolutionary history | Well-documented for archaic introgression | Performance varies across divergence times |

| Genomatnn | Various demographic histories | Flexible modeling approach | Computational intensity |

| MaLAdapt | Selection detection | Specifically designed for adaptive introgression | Requires careful parameterization |

| Q95(w, y) | Exploratory studies | High efficiency, good performance in benchmarks [11] | May require follow-up with other methods |

Critical to accurate detection is accounting for the hitchhiking effect of adaptively introgressed mutations on flanking regions. Studies highlight the importance of including adjacent windows in training data to correctly identify the specific window containing the mutation under selection [11]. Methods based on Q95 statistics appear most efficient for initial exploratory studies of adaptive introgression [11].

Experimental and Research Applications

Research Reagent Solutions for Introgression Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Introgression Analysis

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| High-coverage reference genomes | Baseline for variant calling and ancestry inference | Altai Neanderthal, Denisova, Chagyrskaya Neanderthal genomes as archaic references [5] |

| Population genomic datasets | Empirical data for introgression detection | 1000 Genomes Project, gnomAD, population-specific sequencing cohorts [5] |

| Selection test statistics | Identifying signatures of positive selection | XP-CLR, Relate, Extended Haplotype Homozygosity (EHH), FST [5] [11] |

| Ancestry inference software | Local ancestry deconvolution | SPrime, map_arch, specific ancestry estimation tools [5] |

| Simulation frameworks | Generating expected patterns under different scenarios | msprime for ancestry and mutation simulation [11] |

Evolutionary and Functional Validation

Beyond genomic detection, understanding the functional consequences of introgression requires experimental validation. For example, in the study of archaic introgression in modern human reproductive genes, researchers identified 47 archaic segments overlapping reproduction-associated genes that reached frequencies over 40% in specific populations—approximately 20 times higher than typical introgressed archaic DNA [5]. Functional validation included:

- Expression Quantitative Trait Locus (eQTL) analysis to identify archaic alleles regulating gene expression in reproductive tissues [5]

- Phenome-wide association studies linking archaic variants to clinical traits including endometriosis, preeclampsia, and prostate cancer risk [5]

- Selection signature analyses using multiple complementary tests (EHH, FST, Relate) to confirm positive selection on core haplotypes [5]

In agricultural contexts, similar approaches have identified adaptive introgression of disease resistance and stress tolerance genes from wild crop relatives into domesticated varieties, providing valuable genetic resources for crop improvement [8].

The classification of introgression into adaptive, neutral, and maladaptive categories provides a crucial framework for understanding how gene flow contributes to evolutionary processes. Rather than being mutually exclusive, these outcomes frequently coexist within genomes, creating complex landscapes shaped by the balance between selective forces [2] [10]. Adaptive introgression represents a powerful mechanism for evolutionary leaps, allowing species to rapidly acquire complex adaptations that would be difficult to evolve through de novo mutation alone [8] [2]. Conversely, maladaptive introgression can impose genetic loads and contribute to extinction risk, particularly in small populations or under changing environmental conditions [8] [2].

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated methods for detecting introgression across diverse taxonomic groups and evolutionary scenarios, moving beyond correlative evidence to explicit models that account for how selection and genetic drift interact to shape introgressed variation [10] [3] [11]. Integrating genomic data with functional validation across different biological levels—from molecular mechanisms to organismal fitness and ecological consequences—will be essential for fully understanding the evolutionary significance of introgression and harnessing its potential for applications in conservation, agriculture, and medicine [2].

Adaptive introgression, the natural transfer of beneficial genetic material between species via hybridization and backcrossing, serves as a potent evolutionary mechanism that enables rapid adaptation. This process allows recipient species to acquire complex, functionally optimized alleles directly from donor populations, effectively bypassing the slow, stepwise accumulation of mutations through traditional evolutionary pathways. By harnessing pre-evolved, adaptive genetic variation, adaptive introgression facilitates evolutionary leaps that would be inaccessible through de novo mutation alone. This technical guide synthesizes current research to delineate the genomic architectures, functional consequences, and experimental methodologies for characterizing this bypass mechanism, with particular emphasis on its implications for biomedical and agricultural innovation.

The modern synthesis of evolution has historically emphasized gradual change through the accumulation of de novo mutations followed by natural selection. However, accumulating genomic evidence reveals that this model inadequately explains numerous instances of rapid adaptation to novel environmental pressures. Adaptive introgression represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, functioning as a natural engine of genomic innovation that operates by transferring pre-adapted genetic variants across species boundaries [2].

This process is characterized by three fundamental stages: initial hybridization between a donor and recipient species, backcrossing of hybrid individuals with the recipient population, and the selective sweep of introgressed alleles that confer a fitness advantage. Unlike neutral or deleterious introgressed variants, which are typically purged by selection or genetic drift, adaptively introgressed alleles rapidly increase in frequency due to their positive effects on fitness [2] [5]. The evolutionary significance of this mechanism lies in its capacity to introduce complex, multi-genic adaptations in a single transfer event, effectively compressing evolutionary timelines that would otherwise require innumerable generations through sequential mutation and selection.

Core Mechanistic Principles of Evolutionary Bypass

Genetic Architecture of Introgressed Adaptations

The evolutionary bypass capacity of adaptive introgression stems from specific genetic and population characteristics that distinguish it from standard models of adaptation:

Standing Genetic Variation Source: Adaptive introgression draws from a reservoir of pre-tested, functionally relevant genetic variation that has evolved in the donor species under specific selective pressures. This provides a "toolkit" of potentially adaptive alleles that are immediately available for selection in the recipient genome [2] [9].

Elevated Initial Allele Frequency: Unlike de novo mutations that begin at extremely low frequencies (typically 1/2N), introgressed alleles enter the recipient population at substantially higher frequencies, determined by hybridization rates. This higher starting frequency dramatically reduces the time to fixation under positive selection [2].

Multi-locus Adaptive Complexes: Introgression can transfer co-adapted gene complexes or tightly linked sets of alleles that work synergistically, enabling the immediate acquisition of polygenic traits that would be virtually impossible to assemble through independent mutations [9].

Comparative Evolutionary Trajectories

Table 1: Comparison of Evolutionary Mechanisms

| Feature | De Novo Mutation | Standing Variation | Adaptive Introgression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Variation | New mutations | Pre-existing polymorphisms in population | Cross-species transfer |

| Initial Allele Frequency | Very low (1/2N) | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Time to Fixation | Slow (many generations) | Moderate | Rapid (fewer generations) |

| Genetic Complexity | Typically single locus | Single or few loci | Often multi-locus complexes |

| Evolutionary Pathway | Stepwise through intermediates | Direct selection on existing variants | Direct acquisition of optimized alleles |

| Bypass Potential | Low | Moderate | High |

The bypass mechanism becomes particularly evident when comparing the acquisition of complex adaptations. For instance, developing altitude adaptation through de novo mutation would require multiple coordinated changes in oxygen sensing, hemoglobin affinity, and vascular development across numerous generations. In contrast, adaptive introgression of the EPAS1 gene from Denisovans to Tibetan populations provided a pre-adapted, optimized haplotype that conferred immediate high-altitude tolerance [12].

Quantitative Evidence Across Biological Systems

Empirical studies across diverse taxa provide compelling evidence for the role of adaptive introgression in bypassing evolutionary intermediate stages. The following table synthesizes key findings from multiple systems:

Table 2: Documented Cases of Adaptive Introgression Bypassing Intermediate Stages

| System | Introgressed Locus/Region | Functional Consequence | Bypassed Intermediate Stages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Humans | EPAS1 (Denisovan origin) | High-altitude adaptation in Tibetans | Incremental physiological acclimatization and genetic adaptation to hypoxia | [5] [12] |

| Modern Humans | AHRR, PGR (Neanderthal origin) | Altered reproductive timing and pregnancy outcomes | Gradual accumulation of fertility-enhancing variants | [5] |

| Poplar Trees (Populus) | RFLP-1286 marker from P. fremontii to P. angustifolia | Enhanced survival under warmer, drier conditions | Stepwise adaptation to climate change through sequential mutation | [13] |

| Spruce Trees (Picea) | Multiple stress-resilience and flowering time genes | Rapid adaptation to environmental gradients and historical climate changes | Gradual local adaptation through selection on standing variation | [14] |

| Newts (Triturus) | Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) classes I and II | Expanded immune repertoire and pathogen recognition | Sequential accumulation of diverse antigen recognition alleles | [15] |

| Crop Plants | Various disease resistance and stress tolerance loci from wild relatives | Immediate adaptation to novel pathogens and climatic conditions | Traditional breeding cycles to introgress traits from wild relatives | [9] |

The quantitative impact of this bypass mechanism is evident in the survival differentials observed in long-term studies. In Populus, for instance, the presence of the introgressed RFLP-1286 marker was associated with approximately 75% greater survival after 31 years in a warm common garden, with all backcross individuals carrying this marker surviving through the study period [13]. This demonstrates how a single introgression event can dramatically alter adaptive trajectories under strong selective pressure.

Methodological Framework for Detection and Validation

Genomic Detection Protocols

Identifying genuine adaptive introgression requires distinguishing it from other evolutionary processes such as incomplete lineage sorting or selective sweeps on standing variation. The following experimental workflows represent state-of-the-art approaches:

Population Genomic Screening Protocol

- Dataset Preparation: Sequence or genotype individuals from putative donor and recipient populations, plus an outgroup population

- Introgression Scan: Apply statistical methods (e.g., D-statistics, f₄-ratio) to identify genomic regions with excess allele sharing between donor and recipient populations

- Selection Tests: Conduct selection scans (e.g., iHS, nSL, XP-EHH) on identified introgressed regions in the recipient population

- Frequency Analysis: Verify elevated frequency of introgressed haplotypes in the recipient population relative to neutral expectations

- Functional Annotation: Annotate candidate regions for genes and regulatory elements to identify potential adaptive targets

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Approach for AI Detection Recent advances implement deep learning for enhanced detection sensitivity [12]:

- Input Matrix Construction: Create genotype matrices from donor, recipient, and unadmixed outgroup populations for 100 kbp genomic windows

- CNN Architecture: Implement a series of convolution layers with 2×2 step size (avoiding pooling layers) to extract features informative of introgression and selection

- Model Training: Train networks using simulated data incorporating admixture and selection parameters

- Saliency Mapping: Visualize input regions that most strongly influence CNN predictions to identify key genomic features

- Empirical Application: Apply trained CNNs to empirical genomic datasets to identify candidate AI regions with >95% accuracy on simulated data

Functional Validation Workflows

Common Garden Experiments [13]

- Experimental Design: Establish common garden(s) with environmental conditions representing selective pressure(s) of interest

- Genotype Planting: Plant individuals representing parental species, hybrids, and backcrosses with known genomic composition

- Phenotypic Monitoring: Track survival, growth, reproduction, and relevant physiological traits over multiple years/seasons

- Association Analysis: Correspond fitness-related traits with introgressed markers using generalized linear models

- Ecosystem Impact Assessment: Measure extended effects on associated communities (e.g., soil microbes, herbivores) where relevant

Molecular Functional Validation

- Gene Expression Profiling: Compare expression patterns of introgressed alleles between donor, recipient, and hybrid backgrounds using RNA-seq

- CRISPR-Cas9 Editing: Precisely introduce or remove introgressed haplotypes in model systems to validate functional effects

- Protein Function Assays: Test biochemical properties of proteins encoded by introgressed alleles versus native versions

- Physiological Phenotyping: Measure organismal-level consequences of introgressed alleles under controlled environmental challenges

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for detecting and validating adaptive introgression, combining population genomic screens with deep learning approaches and functional validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Studying Adaptive Introgression

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | High-coverage assemblies of donor, recipient, and outgroup species | Essential for read mapping, variant calling, and phylogenetic inference | Ensure chromosomal-level scaffolding; annotate with functional elements |

| Population Genomic Datasets | Whole-genome sequences from multiple individuals per population | Identify introgressed regions and estimate allele frequencies | Sample size >20 individuals per population; minimum 10X coverage recommended |

| Genotyping Arrays | Custom SNP chips targeting candidate introgressed regions | High-throughput screening of large sample collections | Design should include ancestry-informative markers and neutral controls |

| Selection Scan Tools | SweepFinder, OmegaPlus, RELATE | Detect signatures of positive selection in genomic data | Account for demographic history to reduce false positives |

| Introgression Detection Software | Dsuite, SPrime, f-statistics, map_arch | Quantify allele sharing and identify introgressed haplotypes | Requires appropriate outgroup selection; sensitive to sample configuration |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | genomatnn (CNN implementation), TensorFlow, PyTorch | Identify complex patterns of AI from genotype matrices | Requires substantial training data; computational resource intensive |

| Common Garden Facilities | Controlled environment gardens, reciprocal transplant sites | Validate fitness consequences under naturalistic conditions | Long-term commitment required; monitor environmental variables |

| Gene Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, base editors | Functionally validate causal introgressed alleles | Requires species-specific transformation protocols; potential pleiotropic effects |

Implications and Future Directions

The mechanistic framework of adaptive introgression as an evolutionary bypass mechanism has profound implications across biological disciplines. In conservation biology, it suggests that managed gene flow between threatened populations and their adapted relatives could facilitate rapid climate adaptation [13]. In agriculture, harnessing wild relative gene pools through natural or facilitated introgression offers a pathway for rapid crop improvement without lengthy breeding cycles [9]. For biomedical research, understanding archaic introgression in human evolution provides insights into genetic underpinnings of adaptation, with potential applications in personalized medicine and therapeutic development [5] [12].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Multi-omics Integration: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to understand the full functional consequences of adaptive introgression

- Temporal Sampling: Applying ancient DNA approaches to track the dynamics of introgression events through time

- Experimental Evolution: Establishing hybrid populations to observe real-time adaptive introgression under controlled selective pressures

- Ecosystem-Level Impacts: Quantifying how adaptive introgression in foundation species cascades through ecological communities

Diagram 2: Bypass mechanism of adaptive introgression showing the direct acquisition of beneficial alleles versus the traditional gradualist path of evolution.

The evidence across diverse biological systems consistently demonstrates that adaptive introgression provides a powerful evolutionary shortcut, enabling species to leapfrog intermediate stages that would be necessary through traditional evolutionary pathways. By leveraging this natural mechanism of genetic exchange, researchers can develop novel strategies for addressing pressing challenges in climate change adaptation, food security, and understanding human evolutionary history.

Adaptive introgression, the natural incorporation of genetic material from one species into the gene pool of another through hybridization and backcrossing, followed by selection, represents a powerful evolutionary mechanism [2]. Historically regarded as a maladaptive process that homogenizes species, this phenomenon has been reevaluated through the lens of genomic studies, which have established its significant role in promoting species adaptation [2] [9]. This technical guide synthesizes evidence demonstrating that adaptive introgression operates across an extensive taxonomic spectrum, from bacteria to mammals, following a complexity gradient with consequences manifesting at multiple levels of biological organization.

The genomic revolution since approximately 2012 has fundamentally shaped our understanding of adaptive introgression, enabling researchers to identify introgressed alleles and document their adaptive benefits across diverse life forms [2]. This whitepaper examines the taxonomic distribution of adaptive introgression, presents structured quantitative data, details methodological approaches for its detection, and provides visualization frameworks and research tools to facilitate further investigation within this evolving field.

Taxonomic Distribution Across Complexity Gradients

Patterns of Adaptive Introgression Across Organisms

Adaptive introgression has been documented across a broad spectrum of taxonomic groups, with evidence indicating its occurrence increases along a gradient of biological complexity. The process was initially considered counterproductive to adaptation but is now recognized as a mechanism that can enhance adaptive capacity and drive evolutionary leaps, potentially bypassing intermediate evolutionary stages [2]. This shift in understanding has emerged from genomic studies that have established clearer insights into how introgressed alleles become incorporated into recipient genomes under selective pressures.

The amount and variety of published studies on adaptive introgression increases from simpler to more complex organisms, with research focusing progressively on consequences across multiple levels of biological organization—from physiological and demographic to behavioral and ecological [2]. This pattern suggests that the adaptive potential of introgression may be more readily realized or more easily detected in organisms with greater structural complexity, though methodological biases in research focus cannot be excluded as a contributing factor to this observed distribution.

Quantitative Evidence of Taxonomic Distribution

Table 1: Documented Evidence of Adaptive Introgression Across Major Taxonomic Groups

| Taxonomic Group | Key Evidence | Biological Levels Affected | Complexity Gradient Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Adaptive gene transfer through mechanisms including hybridization [2] | Genomic, physiological | Lower complexity |

| Protists | Evidence of adaptive introgression in multiple species [2] | Genomic, functional | Lower complexity |

| Fungi | Documented cases of adaptive introgression [2] | Genomic, physiological | Intermediate complexity |

| Plants (Bryophytes to Angiosperms) | Extensive evidence from bryophytes to angiosperms; crop wild relative introgression [2] [9] | Genomic, physiological, demographic, ecological | Intermediate to high complexity |

| Invertebrates | Demonstrated adaptive introgression in various species [2] | Genomic, physiological, behavioral/ecological | Intermediate complexity |

| Vertebrates | Widespread evidence of adaptive introgression across multiple classes [2] | Genomic, physiological, demographic, behavioral/ecological | Highest complexity |

Table 2: Evolutionary Mechanisms Co-occurring with Adaptive Introgression

| Evolutionary Mechanism | Relationship with Adaptive Introgression | Documented Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal introgression | Co-occurs with islands of differentiation in sex-linked chromosomes [2] | Demonstrated across multiple taxa |

| Balancing selection | Maintains beneficial introgressed alleles against genetic drift [2] | Documented in diverse organisms |

| Sexual selection | Operates alongside assortative mating pressures [2] | Observed in various animal species |

| Selective sweeps | Rapid fixation of beneficial introgressed alleles [2] | Identified through genomic scans |

| Transgressive segregation | Production of extreme phenotypes leading to hybrid speciation [2] | Particularly documented in plants |

Methodological Framework for Detecting Adaptive Introgression

Genomic Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Population Genomic Screening Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Obtain genomic data from potential hybridizing species and their populations, ensuring geographical context is documented [9]

- Sequence Alignment and Variant Calling: Use high-throughput sequencing approaches (whole-genome or reduced-representation) followed by alignment to reference genomes and SNP identification [2]

- Introgression Detection: Apply statistical methods (e.g., ABBA-BABA tests, fd statistics) to identify regions with significant evidence of interspecific gene flow [9]

- Selection Scanning: Implement composite likelihood ratio tests (CLR) or cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH) to detect signatures of positive selection on introgressed regions [9]

- Functional Annotation: Annotate putative adaptive regions using genomic databases to identify genes and regulatory elements under selection [9]

- Phenotypic Association: Correlate introgressed haplotypes with phenotypic traits through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) or functional validation [9]

Functional Validation Protocol:

- Gene Expression Analysis: Compare expression patterns of introgressed alleles versus native alleles using RNA sequencing [9]

- Gene Editing: Implement CRISPR-Cas9 to introduce introgressed alleles into recipient genetic background and evaluate phenotypic effects [9]

- Reciprocal Transplants: Conduct field experiments comparing fitness of genotypes with and without introgressed alleles across relevant environmental gradients [9]

Visualization of Adaptive Introgression Detection Workflow

Biological Network Analysis for Introgression Studies

Network-Based Detection Protocol:

- Gene Network Construction: Build co-expression or protein-protein interaction networks using tools like Cytoscape [16]

- Module Identification: Apply community detection algorithms to identify functionally related gene modules [16]

- Introgression Mapping: Overlay introgressed regions onto network modules to identify functionally coherent units [16]

- Hub Gene Analysis: Identify central genes within introgressed modules that may drive adaptive phenotypes [16]

- Comparative Network Analysis: Contrast network properties between populations with and without introgression [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Adaptive Introgression Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Whole-genome sequencing, Reduced-representation sequencing (RAD-seq) | Genomic variant identification | Detection of introgressed regions across taxa [2] |

| Population Genetic Software | ABBA-BABA tests, fd statistics, CLR tests, XP-EHH analysis | Statistical detection of introgression and selection | Identifying and dating introgression events [9] |

| Network Analysis Tools | Cytoscape, STRING, custom scripts in R/Python | Biological network construction and analysis | Mapping introgression to functional modules [16] |

| Gene Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs | Functional validation of introgressed alleles | Experimental verification of adaptive function [9] |

| Visualization Platforms | Graph visualization libraries, Circos, custom DOT scripts | Data representation and interpretation | Creating publication-quality figures [16] |

Evolutionary Significance and Research Implications

Co-occurrence of Evolutionary Forces

Adaptive introgression frequently operates alongside counteracting evolutionary mechanisms, demonstrating that convergent and divergent processes are not mutually exclusive [2]. This balance is mediated by environmental conditions that shape the evolutionary trajectory of introgressing species. Key examples of these co-occurring forces include:

- Autosomal introgression alongside genomic islands of differentiation in sex-linked chromosomes [2]

- Balancing selection maintaining introgressed variation against the effects of genetic drift [2]

- Sexual selection operating simultaneously with assortative mating, creating complex evolutionary dynamics [2]

Environmental pressures, including both natural and anthropogenic factors, drive adaptive introgression at the genomic level, leading to consequences across multiple biological organization levels [2]. This interplay between gene flow and selection enables rapid adaptation, potentially faster than through de novo mutations, as introgressed alleles may begin with higher initial prevalence in populations [2].

Implications for Conservation and Climate Adaptation

The study of adaptive introgression patterns has important implications for understanding species adaptation in rapidly changing environments [2]. In crop species, adaptive introgression from wild relatives represents a promising mechanism for developing climate-resilient varieties [9]. Harnessing this evolutionary process may enable more rapid crop adaptation to emerging biotic and abiotic stresses than traditional breeding approaches permit.

For wild species, recognizing the adaptive potential of introgression challenges conservation paradigms that exclusively view hybridization as a threat. In some circumstances, adaptive introgression can paradoxically lead to species divergence through mechanisms such as transgressive segregation and hybrid speciation [2]. This nuanced understanding necessitates context-dependent conservation strategies that recognize the potential benefits of managed gene flow for population persistence under environmental change.

The evidence synthesized in this technical guide demonstrates that adaptive introgression represents a significant evolutionary mechanism operating across the taxonomic spectrum, from bacteria to mammals, with increasing prevalence along complexity gradients. The genomic revolution has been instrumental in revealing the taxonomic distribution and evolutionary significance of this process, which frequently co-occurs with divergent evolutionary mechanisms. The methodological frameworks, visualization approaches, and research tools detailed herein provide investigators with robust protocols for investigating adaptive introgression in diverse biological systems. As environmental changes accelerate, understanding and potentially harnessing this evolutionary process may prove crucial for species persistence and agricultural sustainability.

The study of adaptive introgression has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, revealing how gene flow between species can serve as a potent evolutionary force. Rather than solely acting as a homogenizing process that hinders divergence, introgressive hybridization is now recognized as a mechanism that can promote rapid adaptation and drive significant evolutionary innovation [2]. This paradigm shift, largely propelled by advances in genomic technologies since approximately 2012, has established that the transfer of genetic material between species can enable evolutionary leaps that bypass intermediate evolutionary stages [2]. This in-depth technical guide examines the principal outcomes of this process—transgressive segregation, hybrid speciation, and evolutionary leaps—situating them within the broader context of adaptive introgression research.

The historical perspective viewed introgression primarily as a conservation concern due to risks of genetic swamping and outbreeding depression [2]. However, contemporary meta-analyses demonstrate that adaptive introgression functions across all taxonomic groups and biological levels, from bacteria to mammals [2]. The evolutionary significance of these processes lies in their capacity to generate novel genetic combinations and phenotypes at a pace that may exceed what is possible through de novo mutation alone, providing a critical mechanism for rapid adaptation in response to environmental pressures, including contemporary climate change [2] [17] [9].

Quantitative Evidence of Evolutionary Patterns

Prevalence of Transgressive Segregation Across Taxa

Table 1: Documented Frequency of Transgressive Segregation in Hybrid Populations

| Taxonomic Group | Studies Reporting Transgression | Traits Exhibiting Transgression | Primary Genetic Basis | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plants (Overall) | 110 of 113 studies (97%) [18] | 336 of 579 traits (58%) [18] | Complementary gene action [18] | Most frequent in inbred, domesticated crosses [18] |

| Wild Outcrossing Plants | 86% of studies [18] | 14% of traits [18] | Complementary gene action, epistasis [18] | Lower frequency than domesticated inbreeders [18] |

| Animals (Overall) | 45 of 58 studies (78%) [18] | 200 of 650 traits (31%) [18] | Varies by genetic architecture [19] | More common in wild outcrossers; less frequent than plants [18] |

| Fungi (Cryptococcus) | Widespread in lab and natural hybrids [20] | Melanin production, capsule size, drug resistance [20] | Novel allelic combinations, heterozygosity [20] | Associated with hybrid vigor and transgressive segregation [20] |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that transgressive segregation is not an exceptional occurrence but rather a common outcome in hybrid populations. The meta-analysis by Rieseberg et al. (1999) revealed that an overwhelming majority of plant hybrid studies (97%) and a substantial majority of animal hybrid studies (78%) documented transgressive phenotypes for at least one trait [18]. The frequency of transgressive traits varies significantly, affecting 58% of examined plant traits and 31% of animal traits, with the disparity partially explained by differences in breeding systems and the prevalence of domesticated versus wild populations in studied samples [18].

The genetic architecture of parental species strongly influences the potential for transgressive segregation. Research on cichlid fishes demonstrated that while the genetic basis of jaw morphology limits transgressive variation, skull shape is highly permissive, indicating that natural selection can constrain transgression for some traits but not others [19]. This contingency underscores that hybridization outcomes depend on both genomic and environmental contexts [19].

Documented Cases of Adaptive Introgression

Table 2: Documented Cases of Adaptive Introgression Across Species

| System/Species | Introgressed Trait/Adaptation | Functional Consequence | Evidence Level | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Humans | Reproductive genes (e.g., AHRR, PGR) [5] | Regulation of developmental pathways; fertility enhancement [5] | Genomic scans, selection tests, eQTL mapping [5] | [5] |

| Populus fremontii × P. angustifolia | Climate resilience alleles [17] | Enhanced survival in warmer, drier conditions [17] | Long-term common garden, marker-trait association [17] | [17] |

| Crop Plants | Stress resistance from wild relatives [9] | Improved adaptation to biotic/abiotic stresses [9] | Genomic studies, phenotypic selection [9] | [9] |

| Aspidoscelis lizards | Gut/skin microbiota restructuring [21] | Niche divergence from progenitor species [21] | Microbiota sequencing, ecological analysis [21] | [21] |

Adaptive introgression has been documented across diverse taxonomic groups, with compelling evidence emerging from human evolutionary history, plant systems, and wildlife. In humans, archaic introgression of reproductive genes has been identified, with three core haplotypes (PNO1-ENSG00000273275-PPP3R1, AHRR, and FLT1) showing signatures of positive selection [5]. The AHRR region exhibited the strongest evidence, with ten variants in the top 1% of the genome-wide distribution for Relate's selection statistic [5]. Furthermore, an archaic haplotype in the PGR gene is associated with reduced miscarriages and decreased bleeding during pregnancy, suggesting a fertility enhancement effect [5].

Foundation species like Populus trees demonstrate how adaptive introgression can confer climate resilience. A 31-year common garden experiment revealed that while pure P. angustifolia and backcross genotypes suffered approximately 70-75% mortality in a warm, low-elevation site, individuals carrying introgressed P. fremontii markers (particularly RFLP-1286) showed up to 75% greater survival [17]. This provides direct experimental evidence that introgression can enhance resistance to selection pressures in warmer, drier climates [17].

Methodological Approaches for Detection and Analysis

Genomic Detection Methods for Adaptive Introgression

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Adaptive Introgression Classification Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Optimal Use Case | Performance Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VolcanoFinder | Population allele frequency spectrum | Well-suited for human evolutionary scenarios [11] | Performance varies with divergence/migration times [11] | [11] |

| Genomatnn | Deep learning approach | Trained on specific evolutionary histories [11] | Context-dependent performance [11] | [11] |

| MaLAdapt | Machine learning framework | Flexible to different datasets [11] | Impacted by evolutionary parameters [11] | [11] |

| Q95(w, y) | Summary statistic | Exploratory studies [11] | Most efficient for initial screening [11] | [11] |

The detection of adaptive introgression requires sophisticated genomic tools and careful experimental design. Recent evaluations of classification methods highlight that performance varies significantly depending on evolutionary parameters such as divergence time, migration history, population size, and selection coefficients [11]. Methods based on the Q95 summary statistic appear most efficient for exploratory studies, while more complex approaches like VolcanoFinder, Genomatnn, and MaLAdapt show context-dependent performance [11].

A critical methodological consideration is the hitchhiking effect of adaptively introgressed mutations, which strongly impacts flanking regions and can complicate discrimination between AI and non-AI genomic windows [11]. Studies demonstrate the importance of including adjacent windows in training data to correctly identify the specific window containing the mutation under selection [11]. This approach controls for the extended linkage disequilibrium generated by selective sweeps.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for detecting adaptive introgression, integrating genomic and phenotypic data.

Experimental Designs for Validating Adaptive Introgression

Controlled crossing designs and common garden experiments remain foundational for establishing causal relationships between introgressed alleles and phenotypic outcomes. The seminal study on transgressive segregation analyzed 171 studies of phenotypic variation in segregating hybrid populations, with most plant studies employing experimental crosses and greenhouse measurements, while animal studies more frequently examined natural hybrid zones [18]. This difference in methodology may contribute to the observed variation in reported transgression frequencies between plants and animals.

Long-term common garden experiments, though rare for long-lived species, provide particularly compelling evidence. The 31-year Populus study exemplifies this approach, where genotypes from different elevations and hybrid categories were planted in a common warm environment to directly assess climate change impacts [17]. Such designs allow researchers to quantify survival, growth, and fitness differences while controlling for environmental variation, enabling rigorous tests of adaptive introgression hypotheses.

For transgressive segregation analysis, quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping in segregating hybrid populations has proven highly effective. Studies consistently identify complementary gene action as the primary genetic mechanism, where parental lines are fixed for alleles with opposing effects that recombine in hybrids to generate extreme phenotypes [18]. Overdominance and epistasis also contribute, though to a lesser extent [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Adaptive Introgression

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Coverage Genomic DNA | Reference genomes; population sequencing | Archaic hominin genomes [5]; parental species references [17] | Quality critical for variant calling; ≥30x coverage recommended |

| Archaic Reference Genomes | Introgression detection in modern populations | Neanderthal (Altai, Vindija, Chagyrskaya); Denisova [5] | Multiple references improve detection accuracy |

| SPrime Algorithm | Archaic segment identification in modern genomes | Scanning for high-frequency archaic variants [5] | Validates against multiple archaic references |

| RFLP Markers | Tracking specific introgressed regions in crosses | Marker-trait association in Populus [17] | PCR-based; useful for non-model organisms |

| Common Garden Facilities | Controlled assessment of genotype performance | Climate change resilience testing [17] | Long-term sites valuable for perennial species |

| Relate Selection Test | Detection of positive selection signatures | Identifying selected haplotypes (e.g., AHRR) [5] | Genome-wide distribution comparison |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Microbiome composition analysis | Holobiont studies in hybrid lizards [21] | Reveals transgressive segregation in microbiota |

The experimental toolkit for studying adaptive introgression and related evolutionary outcomes spans genomic, computational, and ecological resources. High-quality reference genomes for both parental and archaic populations form the foundation for detecting introgressed segments [5] [17]. Computational tools like SPrime enable systematic scanning for archaic variants in modern genomes, while selection tests like those implemented in Relate help identify signatures of positive selection [5].

For non-model organisms and experimental crosses, PCR-based markers such as RFLPs provide a cost-effective method for tracking specific introgressed regions and establishing marker-trait associations, as demonstrated in the Populus system [17]. Common garden facilities represent critical infrastructure for disentangling genetic and environmental effects on phenotype, with long-term gardens providing particularly valuable insights for climate adaptation research [17].

Emerging approaches include microbiome sequencing (e.g., 16S rRNA) to assess how hybridization affects host-associated microbial communities, expanding the concept of the holobiont in evolutionary studies [21]. This integrated perspective recognizes that hybrid fitness and ecological success may involve complex interactions between host genetics and microbiota.

Evolutionary Implications and Research Frontiers

The accumulating evidence for transgressive segregation, hybrid speciation, and evolutionary leaps through adaptive introgression has profound implications for evolutionary theory, conservation biology, and agricultural science. These mechanisms demonstrate that evolutionary innovation can arise not only gradually through mutation but also rapidly through the recombination of existing genetic variation across species boundaries [2] [9].

Figure 2: Logical relationships between hybridization processes and major evolutionary outcomes, highlighting key concepts.

In conservation biology, the recognition that adaptive introgression can enhance climate resilience suggests that hybrid zones may represent important evolutionary laboratories rather than merely conservation concerns [17]. The documentation that introgressed alleles can increase survival in foundation tree species by up to 75% under warming conditions indicates that managed gene flow may represent a valuable strategy for enhancing ecosystem resilience to climate change [17].

In agricultural systems, wild-to-crop introgression represents an untapped resource for crop improvement, particularly for enhancing stress resistance [9]. Screening wild introgression already present in cultivated gene pools may efficiently identify valuable alleles adapted to emerging environmental conditions, potentially offering a more rapid approach than de novo domestication or traditional breeding [9].

Future research directions include refining genomic detection methods to perform reliably across diverse evolutionary scenarios [11], understanding the genomic constraints on transgressive segregation [19], and exploring how hybridization shapes holobiont evolution through restructuring of host-associated microbiota [21]. The emerging concept of "hopeful holobionts" suggests that successful hybrids may leverage transgressive segregation of microbial communities to expand their ecological niches, potentially driving evolutionary diversification [21].

As research in this field progresses, it continues to reveal the creative role of hybridization in adaptive evolution, demonstrating that introgression from divergent lineages can provide the raw material for rapid adaptation, ecological divergence, and evolutionary innovation across the tree of life.

Advanced Genomic Tools and Computational Methods for Detecting Adaptive Introgression

Adaptive introgression (AI), the process by which beneficial genetic material is transferred between species or populations through hybridization and then spreads via natural selection, is increasingly recognized as a crucial mechanism for rapid adaptation [8]. Detecting these genomic regions is computationally complex, as it requires distinguishing the faint signatures of selection on introgressed haplotypes from other evolutionary forces such as neutral introgression, background selection, or independent selective sweeps [12]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for this task, capable of learning complex spatial patterns from genomic data without relying on predefined summary statistics that may discard biologically relevant information [22] [12]. The genomatnn framework represents a specialized implementation of CNNs specifically designed to identify genomic regions evolving under adaptive introgression by directly processing genotype matrices from multiple populations [12].

genomatnn Architecture: Core Components and Design Principles

Input Representation and Data Preprocessing

The genomatnn architecture begins with a sophisticated input representation that encodes population genetic data into a format amenable to convolutional processing:

- Input Data Structure: The network processes an

n × mmatrix wherenrepresents the number of haplotypes (or diploid genotypes for unphased data) andmcorresponds to bins along a genomic window, typically 100 kbp in size. Each matrix entry contains the count of minor alleles for an individual in a specific bin [12]. - Population Concatenation: Data from three key populations are processed and concatenated: the donor population (source of introgressed material), the recipient population (where adaptive introgression may occur), and an unadmixed sister population serving as an outgroup. Within each population, pseudo-haplotypes are sorted by similarity to the donor population before concatenation [12].

- Image Resizing Scheme: genomatnn incorporates an innovative resizing approach that preserves inter-allele distances and local density of segregating sites, maintaining critical spatial information while enabling faster training times compared to methods that discard positional information [12].

CNN Layer Architecture and Specialized Components

The genomatnn implementation features a CNN architecture optimized for population genetic data:

Table 1: Core Architectural Components of genomatnn

| Component | Implementation in genomatnn | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Layers | Series with successively smaller outputs | Extract increasingly higher-level features from genotype matrices [12] |

| Downsampling Method | 2×2 stride in convolutions instead of pooling layers | Reduces computational burden while maintaining accuracy comparable to traditional CNNs [12] |

| Activation Functions | Not explicitly stated, but ReLU common in similar genomic CNNs [23] | Introduces non-linearity to learn complex patterns |

| Output Layer | Single probability score | Probability that input matrix comes from a genomic region undergoing adaptive introgression [12] |

Innovative Computational Optimizations

genomatnn incorporates several technical innovations that enhance its efficiency for genomic analyses:

- Stride-Based Dimensionality Reduction: By replacing traditional pooling layers with a 2×2 step size during convolutions, genomatnn achieves comparable accuracy to conventional implementations while significantly reducing computational burden [12]. This approach maintains spatial relationships while efficiently compressing representations.

- Shift Invariance Exploitation: Similar to optimized genomic CNNs like FASTER-NN, genomatnn leverages the shift invariance property of CNNs to perform inference over overlapping genomic windows without redundant computations, maximizing data reuse [22].

- Sample Size Invariance: The data representation and model complexity are designed to be largely invariant to sample size, a crucial feature for processing large-scale genomic datasets with varying numbers of individuals [22].

Implementation Framework: From Simulation to Detection

Training Protocol and Simulation Framework

genomatnn employs a comprehensive training approach based on simulated data:

- Simulation Infrastructure: The framework interfaces with a selection module integrated into the stdpopsim framework, utilizing the forwards-in-time simulator SLiM (Haller and Messer, 2019) to generate training data [12].

- Training Scenarios: The CNN is trained using simulations encompassing a wide range of selection coefficients and times of selection onset, enabling the network to detect both complete and incomplete sweeps occurring at any time after gene flow without assuming prior knowledge of these parameters [12].

- Multi-Fidelity Optimization: While not explicitly mentioned for genomatnn, similar genomic CNN frameworks like GenomeNet-Architect use multi-fidelity optimization that initially evaluates configurations with shorter runtimes for more efficient search space exploration [24].

Interpretation and Visualization Features

genomatnn incorporates specialized functionality for interpreting results:

- Saliency Mapping: The framework includes visualization tools that plot saliency maps, highlighting regions of the genotype matrix that contribute most significantly to the CNN prediction score. This feature helps researchers understand which aspects of the input data drive classification decisions [12].

- Pre-Trained Models: The developers provide downloadable pre-trained CNNs alongside pipelines for training new networks on custom datasets, facilitating adoption by the research community [12].

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Accuracy and Performance Benchmarks

The genomatnn framework has undergone rigorous validation:

- Simulation-Based Testing: On simulated data, the architecture demonstrates 95% accuracy in distinguishing regions under adaptive introgression from those evolving neutrally or experiencing selective sweeps [12].

- Robustness to Data Challenges: Accuracy remains high even with unphased genomic data and decreases only moderately in the presence of heterosis (hybrid vigor) [12].

- Comparison to Alternatives: While explicit comparisons to other AI detection methods are not provided in the available literature, the reported accuracy exceeds typical performance of summary statistic-based approaches, which often struggle to jointly model introgression and selection [12].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of genomatnn

| Metric | Performance | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 95% | Simulated data [12] |

| Data Type Handling | High accuracy with both phased and unphased data | Unphased genomes [12] |

| Selection Timing | Effective for both ancient and recent selection | Various selection onset times [12] |