Adaptive Introgression: The Genomic Engine of Forest Tree Evolution and Climate Resilience

This article synthesizes contemporary research on adaptive introgression—the natural transfer of beneficial genetic material between species—and its profound impact on forest tree evolution.

Adaptive Introgression: The Genomic Engine of Forest Tree Evolution and Climate Resilience

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on adaptive introgression—the natural transfer of beneficial genetic material between species—and its profound impact on forest tree evolution. For researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational principles shifting the historical paradigm of hybridization from a maladaptive to a constructive evolutionary force. We detail advanced genomic methodologies for detecting introgression and analyze case studies across diverse genera, including Pinus, Populus, and Picea, that demonstrate its role in local adaptation. Furthermore, we address the computational and biological challenges in validating adaptive gene flow and present evidence from long-term common garden experiments. The synthesis concludes by highlighting the critical implications of these findings for forest conservation genomics and the development of climate-resilient breeding strategies.

From Maladaptation to Evolutionary Rescue: Redefining Hybridization's Role in Forests

The conceptual framework surrounding interspecific hybridization has undergone a profound transformation in evolutionary biology. Historically dismissed as a maladaptive process leading to genetic swamping and species integrity erosion, hybridization is now recognized as a potent evolutionary mechanism facilitating rapid adaptation. This paradigm shift is particularly consequential for forest tree evolution, where long generation times and complex genomes challenge traditional adaptation models. Genomic advances have revealed that adaptive introgression—the natural incorporation of beneficial alleles from one species into another through hybridization—serves as a critical source of genetic variation that enhances resilience to environmental pressures. This review synthesizes the theoretical underpinnings, methodological advances, and empirical evidence driving this conceptual transition, with specific emphasis on implications for forest tree research in an era of rapid climate change.

The understanding of hybridization outcomes has transitioned from primarily negative to recognizing significant adaptive potential. Historical perspectives viewed interspecific gene flow as a largely deleterious process counteracting divergent selection and threatening species survival through genetic homogenization [1]. This viewpoint stemmed from observations of outbreeding depression, where hybrid offspring exhibited reduced fitness, and genetic swamping, where rare species risked genomic absorption by more abundant congeners [2]. For forest trees, conservation policies often reflected this perspective by prioritizing pure-species preservation and viewing hybrid zones as threats to genetic integrity.

The modern synthesis recognizes hybridization as a dual-purpose force with context-dependent outcomes. Genomic studies across diverse taxa have established that introgression can introduce beneficial genetic variants that spread rapidly under selective pressures, a process termed adaptive introgression [1] [3]. This paradigm shift acknowledges that while maladaptive hybridization occurs, natural selection efficiently purges deleterious introgressed alleles while favoring beneficial ones, sometimes resulting in evolutionary leaps that bypass intermediate mutational stages [1]. In long-lived species like forest trees, this mechanism provides a critical pathway for rapid adaptation that compensates for lengthy generation cycles.

Table 1: Historical vs. Contemporary Views on Hybridization

| Aspect | Historical Perspective (Pre-Genomics) | Contemporary Perspective (Genomic Era) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Maladaptive, homogenizing force | Evolutionary mechanism with adaptive potential |

| Dominant Outcome | Genetic swamping, outbreeding depression | Context-dependent (adaptive, neutral, or maladaptive) |

| Conservation Approach | Preservation of pure lineages | Management of gene flow for evolutionary potential |

| Evolutionary Speed | Hindrance to divergence | Catalyst for rapid adaptation |

| Genomic View | Threat to genomic integrity | Source of novel adaptive variation |

Theoretical Foundations: From Maladaptation to Adaptive Evolution

The Historical Paradigm: Genetic Swamping

The traditional view of hybridization as detrimental emerged from several theoretical premises. Genetic swamping was considered a primary risk, particularly for endangered species or those with small population sizes interacting with more abundant relatives [2]. The homogenization argument posited that gene flow would counteract local adaptation by introducing alleles outside the local adaptive range, thereby blurring species boundaries and reversing diversification [1]. Furthermore, the fitness reduction perspective emphasized that hybridization could break up co-adapted gene complexes, leading to outbreeding depression manifested through reduced hybrid viability or fertility [2]. These concerns were especially pronounced for forest trees, where fitness consequences might not be apparent for decades.

The Contemporary Framework: Adaptive Introgression

Current evolutionary theory recognizes three potential outcomes of hybridization, with adaptive introgression representing a powerful evolutionary pathway. Selective sweeps describe the process whereby beneficial introgressed alleles rapidly increase in frequency within a population due to natural selection [1]. Unlike de novo mutations, introgressed alleles enter the recipient population with higher initial frequency, accelerating their fixation. Evolutionary rescue occurs when adaptive introgression provides critical genetic variation that enables population persistence under environmental conditions that would otherwise cause extinction [1]. For forest trees facing climate change, this mechanism offers potential for enhanced resilience. Transgressive segregation generates extreme phenotypic traits outside the parental range through novel genetic combinations, potentially leading to hybrid speciation [1].

Table 2: Evolutionary Mechanisms Linked to Adaptive Introgression

| Mechanism | Process | Counteracting Force |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal Introgression | Widespread gene flow of beneficial alleles | Islands of differentiation in sex-linked chromosomes |

| Balancing Selection | Maintenance of multiple alleles in population | Genetic drift |

| Sexual Selection | Mating preference for fit hybrids | Assortative mating |

| Selective Sweeps | Rapid fixation of advantageous introgressed alleles | Background selection against linked deleterious variants |

The balance between these opposing forces determines introgression outcomes and is mediated by environmental conditions that shape the evolutionary trajectory of hybridizing species [1].

Genomic Revolution: Methodological Advances Driving the Paradigm Shift

Detection Tools and Classification Methods

The paradigm shift from genetic swamping to adaptive introgression has been largely propelled by advances in genomic technologies and analytical methods. Early approaches relied on limited genetic markers (e.g., microsatellites) and morphological traits, which often failed to distinguish neutral from adaptive introgression and biased detection toward negative consequences that were easier to demonstrate [2].

Contemporary methods include sophisticated statistical frameworks for identifying adaptive introgression. VolcanoFinder detects selective sweeps from archaic introgression; Genomatnn uses deep learning to identify introgressed loci; MaLAdapt employs machine learning to detect local adaptation; and Q95 summary statistics provide efficient exploratory analysis [4]. Performance varies across evolutionary scenarios, with Q95-based methods showing particular promise for initial screening [4]. A critical methodological consideration is the hitchhiking effect, where selection on adaptively introgressed mutations strongly impacts flanking regions, requiring careful discrimination between directly selected windows and adjacent linked regions [4].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Studying Adaptive Introgression

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | Populus trichocarpa, Pinus taeda, Eucalyptus grandis | Ancestry inference and variant mapping |

| Genetic Markers | KASP markers, RFLP markers, GBS-SNPs | Genotyping and tracking introgressed regions |

| Analytical Tools | VolcanoFinder, Genomatnn, MaLAdapt, SPrime | Statistical detection of adaptive introgression |

| Biological Materials | Common garden collections, Germplasm banks, Synthetic hybrids | Phenotypic screening under controlled conditions |

| Environmental Data | Climate layers, Soil maps, Remote sensing data | Genotype-environment association studies |

Case Studies in Forest Trees: Empirical Evidence of Adaptive Introgression

Populus fremontii × angustifolia: Climate Resilience Through Introgression

A landmark 31-year common garden experiment with foundation riparian trees provides compelling evidence for adaptive introgression enhancing climate change resilience. Experimental design involved planting genotypes of low-elevation Populus fremontii, high-elevation P. angustifolia, their F1 hybrids, and backcrosses in a warm, low-elevation site representing future climate conditions [5]. Survival patterns after three decades revealed strong selection: approximately 90% of warm-adapted P. fremontii and 100% of F1 hybrids survived, compared to only 25-30% of cool-adapted P. angustifolia and backcross genotypes [5]. Marker-trait associations identified specific RFLP markers (RFLP-1286) from P. fremontii that increased survival odds in P. angustifolia and backcross trees by 75% [5]. This demonstrates how introgression can enrich genetic variation and enhance adaptive capacity in vulnerable species.

Applied Forest Tree Breeding: Harnessing Hybrid Vigor

Forest tree improvement programs increasingly leverage introgression through predictive breeding approaches. Hybrid breeding utilizes heterosis (hybrid vigor) to enhance traits like growth rate and stress resistance, with successful examples including Eucalyptus grandis × E. nithes and Pinus elliotti × P. oocarpa [6]. Backcross breeding facilitates targeted introgression of desirable traits from exotic sources into elite populations, exemplified by transfer of blight resistance from Chinese to American chestnut populations [6]. Genomic selection employs genome-wide markers to predict breeding values for polygenic adaptive traits, overcoming limitations of marker-assisted selection for complex characteristics [6].

Wheat Improvement: Introgression for Disease Resistance

Crop systems provide transferable insights for forest trees, with wheat improvement demonstrating successful harnessing of adaptive introgression. The Oklahoma State University Wheat Improvement Team identified and introgressed quantitative trait loci (QTL) for leaf rust resistance from landraces and synthetic hexaploid wheat, developing KASP markers for efficient marker-assisted selection [7]. Similarly, the greenbug resistance gene Gb9 was identified in synthetic hexaploid wheat and delimited to a 0.6-cM interval on chromosome 7DL, providing resistance against multiple virulent biotypes [7]. These examples illustrate the practical application of introgression for enhancing adaptive traits.

Implications for Forest Tree Research and Conservation

Rethinking Conservation Paradigms

The recognition of adaptive introgression necessitates revised conservation strategies for forest trees. Assisted gene flow involves human-facilitated movement of genotypes pre-adapted to future climate conditions, potentially incorporating admixed individuals with enhanced resilience [6]. Hybrid zone conservation recognizes that naturally hybridizing populations may serve as evolutionary laboratories generating adaptive variation, rather than simply threats to species integrity [5]. Germplasm screening of existing wild and cultivated populations can identify previously overlooked adaptive variants resulting from historical introgression events [8].

Forest Tree Breeding Under Global Change

Breeding strategies must evolve to incorporate adaptive introgression in climate-resilient reforestation. Predictive breeding approaches like genomic selection can leverage introgressed variation while shortening long breeding cycles characteristic of forest trees [6]. Provenance trials and common garden experiments remain essential for validating the adaptive value of introgressed alleles across environmental gradients [6]. Gene editing technologies may eventually allow precise introgression of adaptive variants without associated genomic baggage, though regulatory and technical barriers remain [9].

The journey from viewing hybridization as genetic swamping to recognizing adaptive introgression represents a fundamental paradigm shift in evolutionary biology with profound implications for forest tree research. This transition, propelled by genomic technologies, has revealed that introgression can provide evolutionary shortcuts for long-lived species facing rapid environmental change. Future research directions should prioritize understanding the genomic architecture of adaptive introgression, particularly for polygenic traits; developing improved detection methods that discriminate adaptive from neutral introgression; and integrating evolutionary theory with conservation practice. For forest trees—with their ecological significance, economic importance, and vulnerability to climate change—harnessing adaptive introgression may prove essential for maintaining resilient ecosystems and sustainable forest productivity.

The fixation of beneficial alleles is a cornerstone of evolutionary adaptation, fundamentally shaping the genetic diversity and adaptive potential of species. Two core population genetic mechanisms—selective sweeps and balancing selection—govern this process, creating distinct genomic signatures and evolutionary outcomes. In the context of forest tree evolution, these processes are particularly dynamic, influenced by large effective population sizes, extensive gene flow, and frequent hybridization events. Adaptive introgression, the interspecific transfer of beneficial genetic variants, serves as a critical bridge between these mechanisms, introducing allelic variation upon which selection can act. This whitepaper details the core mechanisms of selective sweeps and balancing selection, their interplay, and their significance in forest tree evolution research, providing researchers with advanced methodological frameworks for their identification and analysis.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Selective Sweeps: Genetic Hitchhiking and Variants

A selective sweep describes the process by which strong positive (directional) selection on a beneficial allele causes it to rapidly increase in frequency and become fixed in a population. As it does so, it reduces genetic variation at linked neutral sites—a phenomenon termed genetic hitchhiking [10].

- Classic 'Hard' Sweeps occur when a de novo beneficial mutation arises on a single haplotype and sweeps through the population to fixation, carrying the linked haplotype with it and creating a pronounced regional reduction in genetic diversity [10].

- 'Soft' Sweeps involve a beneficial allele that is already present in the population as multiple copies before the onset of selection. This can occur from selection on standing genetic variation or from multiple independent mutations. Soft sweeps result in a less pronounced reduction of linked variation and are characterized by multiple haplotypes carrying the beneficial allele [10] [11].

Balancing Selection: Maintaining Polymorphism

In contrast to directional selection, balancing selection describes a suite of selective pressures that act to maintain multiple alleles at a locus over long evolutionary timescales, thereby preserving genetic polymorphism. Modes of balancing selection include heterozygote advantage (overdominance), frequency-dependent selection, and selection that varies across space or time. A key genomic signature of long-term balancing selection is that beneficial alleles are, on average, older than neutral alleles of the same frequency [11].

Quantitative Data and Genomic Signatures

The table below summarizes the key comparative features of these evolutionary mechanisms, which serve as the basis for their identification in genomic data.

Table 1: Comparative Genomic Signatures of Selection Mechanisms

| Feature | Classic Hard Sweep | Soft Sweep | Balancing Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Genetic Pattern | Reduction of linked neutral variation [10] | Multiple haplotypes carry the beneficial allele [10] | Maintenance of multiple alleles over time [11] |

| Allele Frequency Spectrum | Skew towards high-frequency derived alleles | Skew towards high-frequency derived alleles | Excess of intermediate-frequency alleles |

| Haplotype Structure | Long, identical haplotypes around the selected locus | Multiple, intermediate-length haplotypes | Deep coalescent times and trans-specific polymorphism |

| Allele Age Profile | Younger than neutral alleles of same frequency | Can be younger or older | Older than neutral alleles of same frequency [11] |

| Expected in Forest Trees | Less common due to large populations and gene flow | More common, facilitated by standing variation and introgression [12] | Common, especially in environmentally heterogeneous landscapes [12] |

Empirical data from human genomics underscores this theoretical framework. An analysis of derived allele ages found that candidate beneficial alleles (positive ΔEP) were consistently older than neutral controls across most frequency intervals, a pattern incompatible with simple directional selection but strongly indicative of balancing selection [11].

Table 2: Empirical Age Analysis of Selected Alleles in a Human Population

| Allele Class | Mean Age Rank vs. Neutral | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Deleterious (Negative ΔEP) | Consistently below 0.5 (younger) [11] | Consistent with negative directional selection |

| Beneficial (Positive ΔEP) | Consistently above 0.5 (older) [11] | Inconsistent with directional selection; suggests balancing selection |

Experimental and Analytical Protocols

Workflow for Identifying Selection in Non-Model Systems

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for detecting selective sweeps and balancing selection, integrating methods from population genomics and phylogenetic analysis.

Detailed Methodologies from Key Studies

Protocol 1: Genomic Analysis of Hybrid Zones and Adaptive Introgression in Pines [12] This protocol is tailored for long-lived, non-model forest trees and highlights the search for adaptively introgressed alleles.

- Population Sampling: Collect tissue samples (e.g., needles, cambium) from multiple individuals across hybrid zones and reference allopatric populations of parental species. For [12], this involved 1,558 trees from 24 populations of Pinus sylvestris and P. mugo.

- Genotyping: Isolate high-quality DNA and perform high-throughput genotyping. The referenced study used a targeted genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach to discover and genotype thousands of nuclear Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs).

- Genetic Structure and Ancestry: Analyze the SNP data to determine genetic structure using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and assign individuals to genetic classes (pure parents, F1 hybrids, backcrosses) using clustering algorithms like ADMIXTURE.

- Introgression Detection: Use methods like fd to identify genomic regions with significant excess ancestry from one species in the genetic background of another, indicating introgression.

- Outlier Locus Detection: Perform genome scans to identify loci under selection by comparing genetic differentiation (e.g., FST) between populations in different environments or between genetic classes. Loci that are statistical outliers are candidates for being under selection.

- Environmental Association Analysis (EAA): Test for correlations between allele frequencies at specific loci and environmental variables (e.g., soil moisture, temperature) to link genetic variation to local adaptation.

Protocol 2: Differentiating Selection Modes using Allele Age Estimates [11] This protocol uses allele age to distinguish between directional and balancing selection.

- Variant Annotation and Filtering: From whole-genome sequencing data (e.g., from 3,600 individuals), identify derived alleles using an inferred ancestral sequence. Categorize non-synonymous SNPs as beneficial, neutral, or deleterious using a metric like Evolutionary Probability (ΔEP).

- Define a Neutral Control Set: Establish a set of putatively neutral SNPs from non-coding, non-regulatory regions of the genome to control for demographic history.

- Allele Age Estimation: Apply a method like the Genealogical Estimation of Variant Age (GEVA) to estimate the coalescent time for the gene tree edge carrying the derived allele. This provides an estimate of the allele's age.

- Age-Frequency Comparison: Compare the ages of selected alleles (beneficial and deleterious) to the distribution of ages for neutral alleles in the same frequency bin.

- Statistical Testing: Use an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to test the null hypothesis that the mean age of selected alleles is equal to that of neutral controls. A significant result with beneficial alleles being older supports the action of balancing selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Selection Studies in Forest Trees

| Reagent / Resource | Function and Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | For accurate amplification of template DNA in preparation for sequencing, especially from often-degraded forest tree samples. | Phusion or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase. |

| SNP Genotyping Array | High-throughput, cost-effective genotyping of thousands of pre-defined SNPs across many individuals. | Custom Axiom or Illumina Infinium arrays designed for the target species. |

| Restriction Enzymes for GBS | Used in Genotyping-by-Sequencing to reduce genome complexity and discover novel SNPs in non-model organisms. | ApeKI or other frequent-cutters. |

| Multi-Species Sequence Alignment | Provides the evolutionary context to infer ancestral states and calculate functional scores like Evolutionary Probability (EP). | Ensembl Compara or custom whole-genome alignments. |

| Allele Age Estimation Software | To estimate the time to the most recent common ancestor of all copies of an allele. | GEVA (Genealogical Estimation of Variant Age). |

| Selection Scan Algorithms | To identify genomic regions with signatures of natural selection from polymorphism data. | SweepFinder2, SweeD (for sweeps); BALLET (for balancing selection). |

Adaptive Introgression as a Bridge Between Mechanisms

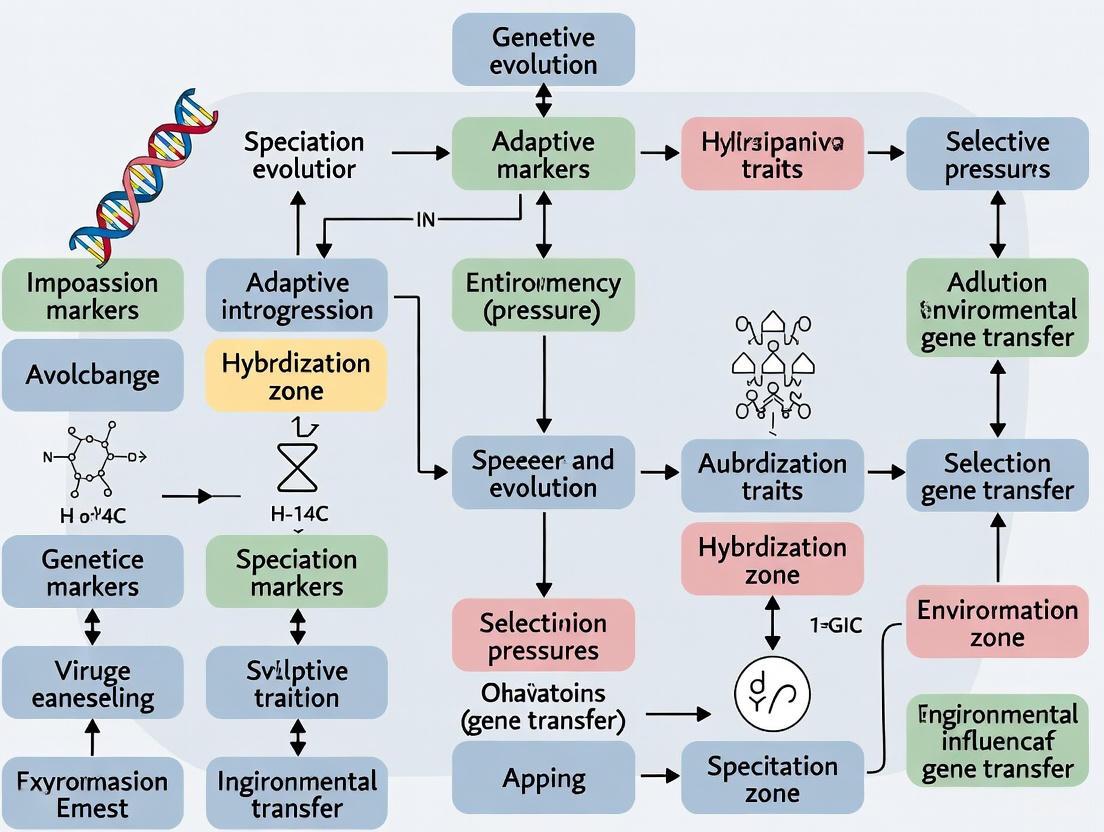

Adaptive introgression is a critical process in forest tree evolution, where interspecific gene flow provides a reservoir of standing genetic variation that can be acted upon by both selective sweeps and balancing selection. The diagram below illustrates this conceptual relationship and its genomic outcomes.

In conifer hybrid zones, such as those between Pinus sylvestris and P. mugo, this model is clearly demonstrated. Genomic analyses reveal strong selective pressures on hybrids and pure P. sylvestris individuals in peat bog habitats, suggesting that P. sylvestris may acquire pre-adapted stress-tolerance alleles through introgression from P. mugo [12]. This introgression can fuel selective sweeps, but the heterogeneity of forest environments also promotes balancing selection, maintaining introgressed variation that is beneficial under specific local conditions. The overall paucity of species-wide "hard" sweeps in human and tree genomes suggests that "soft" sweeps on older, often introgressed standing variation, coupled with balancing selection, are dominant modes of adaptation in species with large and structured populations [11] [12].

The genomic landscape of differentiation refers to the heterogeneous patterns of genetic divergence observed across the genomes of diverging populations or species [13]. These landscapes are often characterized by "islands of differentiation"—genomic regions exhibiting exceptionally high divergence—set against a background of much lower genomic differentiation [13]. Understanding the evolutionary forces that create these landscapes is crucial for unraveling the genetic basis of speciation and local adaptation. In long-lived organisms like forest trees, this is particularly relevant due to their extensive gene flow, large effective population sizes, and complex demographic histories [12]. This technical guide explores the genomic architectures in trees within the context of a broader thesis on the impact of adaptive introgression—the transfer of beneficial genetic material between species through hybridization—on forest tree evolution research [12].

Theoretical Framework: Forces Shaping Genomic Landscapes

Genomic islands of differentiation can arise from multiple evolutionary processes. A key challenge lies in distinguishing their underlying causes [13].

Primary Evolutionary Drivers

- Selection with Gene Flow: Divergence occurs despite ongoing gene flow between populations. In this model, islands are thought to contain loci involved in local adaptation or reproductive isolation, which are resistant to gene flow, while the rest of the genome is homogenized [13].

- Linked Selection: This process involves the interaction between natural selection and genetic linkage. Both positive selection (selective sweeps) and negative selection (background selection) can reduce genetic variation in regions of low recombination, creating peaks of differentiation [14] [13]. This mechanism can create patterns resembling genomic islands even in the absence of gene flow during divergence.

- Variable Recombination Rates: The recombination rate is not uniform across the genome. Regions with low recombination, such as centromeres or telomeres, exhibit reduced genetic diversity and increased differentiation due to the increased effect of linked selection [13].

- Gene Flow and Introgression: Adaptive introgression, the process by which beneficial alleles are transferred between species via hybridization, can leave distinct signatures in the genomic landscape, introducing locally adaptive variants into hybrid populations [12].

Table 1: Key Processes Shaping Genomic Islands of Differentiation

| Process | Genomic Signature | Key Characteristics in Trees |

|---|---|---|

| Selection with Gene Flow | Islands contain loci under divergent selection | Loci associated with local adaptation to soil, climate, or pathogens [12] |

| Linked Selection | Peaks of differentiation in low-recombination regions | Correlated with recombination rate variation; widespread in large tree genomes [14] |

| Adaptive Introgression | Islands of foreign ancestry in a genomic background | Transfer of beneficial alleles for stress tolerance (e.g., bog adaptation in pines) [12] |

Case Studies in Forest Trees

Genomic Landscapes Across aPopulusDivergence Gradient

A 2023 study on eight closely related Populus (poplar) species resequenced 201 whole genomes from species pairs at different stages of divergence to investigate speciation processes [14]. The study found:

- Extensive Introgression: Population structure and ancestry analyses revealed substantial gene flow, particularly between species with parapatric distributions [14].

- Conserved Patterns: The research observed relatively conserved patterns of genomic divergence across species pairs, independent of their position on the divergence gradient [14].

- Role of Linked Selection: The study concluded that linked selection, alongside gene flow and standing genetic variation, was a primary force in shaping these genomic landscapes [14].

Adaptive Introgression inPinusHybrid Zones

A 2025 study provided one of the most extensive genomic investigations of hybridization in Pinus, analyzing over 1,500 individuals from hybrid zones and allopatric reference populations of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and dwarf mountain pine (P. mugo) [12].

- Hybrid Ancestry Patterns: Individuals in hybrid zones were classified as putative pure species, first-generation hybrids, and advanced backcrosses, with a majority of hybrids showing a genetic ancestry shift towards P. mugo [12].

- Outlier Loci: Most outlier loci (indicative of selection) were shared across sympatric populations, though some were specific to individual contact zones. These loci were linked to regulatory processes like phosphorylation, proteolysis, and transmembrane transport [12].

- Asymmetric Local Adaptation: Signatures of local adaptation were strongest in pure P. sylvestris and hybrids with majority P. sylvestris ancestry, suggesting adaptation to marginal peat bog habitats outside the species' core niche. Weaker selection signals in P. mugo-ancestry individuals indicate pre-adaptation to these environments [12].

Table 2: Genomic Studies of Differentiation in Forest Trees

| Study System | Key Findings | Implications for Speciation and Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Populus Species Complex [14] | Conserved genomic landscapes; signatures of linked selection and gene flow | Highlights the importance of investigating multiple species pairs across a divergence gradient to understand evolutionary forces. |

| Pinus sylvestris and P. mugo Hybrid Zones [12] | Asymmetric introgression; strong selection on hybrids and pure P. sylvestris in marginal habitats | Demonstrates the role of adaptive introgression in facilitating range expansion and survival in challenging environments. |

Experimental and Methodological Framework

Genomic Data Acquisition and Analysis Protocols

Study Design and Sampling:

- Population Selection: Sample from multiple contact zones (sympatric populations) and allopatric reference populations for comparative analysis [12]. For studies of divergence gradients, sample multiple species pairs at varying stages of divergence [14].

- Replication: Include replicate population pairs to distinguish shared evolutionary patterns from population-specific events [13].

- Sample Size: Large sample sizes are critical. The Pinus study genotyped 1,558 individuals from 24 populations to ensure robust statistical power [12].

DNA Extraction and Genotyping:

- High-Throughput SNP Genotyping: Use techniques to genotype thousands of nuclear Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). The Pinus study utilized a targeted genotyping-by-sequencing approach, generating data for thousands of SNPs [12].

- Whole-Genome Resequencing (WGS): For the highest resolution, WGS of individually tagged samples is recommended, with reads mapped to a high-quality reference genome assembly [13]. The Populus study employed whole-genome resequencing of 201 individuals [14].

Bioinformatic and Population Genomic Analysis:

- Population Structure: Analyze genetic structure and assign individuals to genetic classes (e.g., pure species, hybrids) using methods like ADMIXTURE or similar clustering algorithms [12].

- Summary Statistics: Calculate a suite of within-species (e.g., nucleotide diversity, π; recombination rate) and between-species (e.g., absolute divergence, dXY; relative divergence, FST) statistics to characterize genomic landscapes [14].

- Identifying Outliers: Use genome scans to detect FST outliers, which are genomic regions with exceptionally high differentiation that may be under selection [12].

- Detecting Introgression: Use methods like fd or similar statistics to identify genomic regions with significant shared ancestry between species, indicative of introgression [12].

Workflow for Genomic Landscape Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Genomic Studies of Tree Differentiation

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA Extraction Kits | To obtain pure, high-molecular-weight DNA from tree tissue (e.g., needles, cambium) for downstream genotyping or sequencing [12]. |

| SNP Genotyping Array or GBS Reagents | For high-throughput genotyping of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms across the genome [12]. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing Library Prep Kits | To prepare genomic DNA libraries for next-generation sequencing on platforms like Illumina [14]. |

| Reference Genome Assembly | A high-quality, chromosome-level genome for the study species or a close relative is essential for read mapping, variant calling, and genomic context [13]. |

| Bioinformatic Software (e.g., ADMIXTURE, PLINK, VCFtools) | For population genetic analyses, including structure inference, quality control, and calculation of summary statistics [12]. |

Visualization of Genomic Landscapes and Pathways

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting complex genomic data. Biological data visualization bridges the gap between algorithmic analyses and researchers' cognitive skills, facilitating hypothesis generation [15]. For genomic landscapes, genome browsers are indispensable for visualizing sequence alignments, annotations, and comparative genomics data [16].

Mechanisms Behind Genomic Islands

The study of genomic landscapes in trees reveals that processes such as linked selection, gene flow, and adaptive introgression are fundamental in shaping genomic architectures during divergence [14] [12]. The case studies in Populus and Pinus demonstrate that genomic islands of differentiation are not necessarily "speciation islands" but can arise from a complex interplay of evolutionary forces [13]. The framework of adaptive introgression is particularly powerful for explaining how tree species acquire and maintain genetic variation necessary to survive in challenging and changing environments. Future research, leveraging long-read sequencing, improved recombination maps, and functional validation, will further illuminate the genetic basis of adaptation and speciation in forest trees.

Adaptive introgression, the process by which species gain beneficial genetic variants through hybridization, is increasingly recognized as a critical mechanism in evolutionary biology and conservation science. In the context of global environmental change, understanding how this process enhances the resilience of foundational species is paramount. This document explores the taxonomic breadth of adaptive introgression, examining its role from conifers to riparian hardwoods, and synthesizes key experimental approaches for documenting its impact. The findings presented herein are framed within a broader thesis on how adaptive introgression is reshaping forest tree evolution research, offering methodologies and analytical frameworks for researchers and scientists engaged in documenting these evolutionary dynamics.

Documented Cases of Adaptive Introgression in Forest Trees

The following section details specific case studies that provide empirical evidence for adaptive introgression across diverse tree taxa, highlighting the genomic regions involved and their potential adaptive functions.

Table 1: Documented Cases of Adaptive Introgression in Forest Trees

| Tree Species (Parental Taxa) | Ecological Context & Selective Pressure | Key Introgressed Genomic Regions / Candidate Genes | Putative Adaptive Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scots pine & Dwarf mountain pine (Pinus sylvestris & P. mugo) [12] | Peat bog habitats; water-logging, nutrient limitation | Multiple outlier loci shared across sympatric populations | Regulatory processes (phosphorylation, proteolysis, transmembrane transport); adaptation to marginal peat bog environments |

| Fremont cottonwood & Narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus fremontii & P. angustifolia) [5] [17] | Warming and drying climatic conditions at lower elevations | RFLP-755, RFLP-754, RFLP-1286 genetic markers | Increased survival and resilience in warmer, drier climates; climate change adaptation |

| Chinese wingnuts (Pterocarya hupehensis & P. macroptera) [18] | Heterogeneous environmental conditions across elevational niches in Qinling-Daba Mountains | TPLC2, CYCH;1, LUH, bHLH112, GLX1, TLP-3, ABC1 | Environmental adaptation; introgressed regions showed lower genetic load and higher genetic diversity |

Methodologies for Detecting Adaptive Introgression

A multi-faceted approach, combining field studies, genomic analyses, and common garden experiments, is essential for conclusively demonstrating adaptive introgression. The following protocols outline key methodologies referenced in the case studies.

Protocol 1: Genomic Analysis of Natural Hybrid Zones

This protocol is derived from studies on Pinus and Pterocarya systems and involves sampling from sympatric hybrid zones and allopatric parental populations [12] [18].

- Population Sampling: Collect tissue samples (e.g., needles, leaves, cambium) from a large number of individuals (n > 1500) across multiple natural hybrid zones and from reference allopatric populations of the putative parental species.

- DNA Extraction and Genotyping: Extract high-quality genomic DNA. Use high-throughput sequencing or SNP arrays to genotype thousands of nuclear single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

- Genetic Ancestry Assignment: Use model-based clustering algorithms (e.g., STRUCTURE, ADMIXTURE) to assign individuals to genetic ancestry groups (pure parental, F1 hybrids, backcrosses).

- Outlier Locus Detection: Perform genome scans to identify outlier loci with exceptionally high genetic differentiation (e.g., using FST-based approaches). These loci are candidates for being under selection.

- Gene Flow and Introgression Tests: Use phylogenetic or population genetic methods (e.g., D-statistics, f4-ratio) to test for signals of historical gene flow and identify introgressed genomic blocks.

- Functional Annotation: Annotate candidate introgressed regions and outlier loci to identify genes and investigate their associated biological processes (e.g., Gene Ontology term enrichment).

Figure 1: Genomic Analysis Workflow for detecting adaptive introgression in natural hybrid zones.

Protocol 2: Common Garden Experiment for Fitness Validation

This protocol is based on the long-term Populus study which tested the fitness consequences of introgression under climate change conditions [5] [17].

- Experimental Design: Establish a common garden at a site representing projected future climate conditions (e.g., warmer, drier). The garden acts as a standardized environment to separate genetic effects from environmental influence.

- Plant Material Collection: Procure genotypes from across the native range of the vulnerable parental species and its hybrids. This includes pure individuals, F1 hybrids, and backcrossed individuals.

- Long-Term Monitoring: Plant genotypes in a randomized block design and monitor over multiple decades (e.g., 30+ years). Track key fitness traits such as survival, growth rates (e.g., biomass accumulation), and reproductive success.

- Climate Transfer Distance Calculation: For each genotype, calculate the geographic and climatic transfer distance (e.g., difference in Mean Annual Temperature) between its source population and the common garden location. This quantifies the magnitude of climate change experienced.

- Genotype-Phenotype Association: Correlate the presence of introgressed genetic markers (e.g., RFLP markers) with survival and growth data using statistical models (e.g., logistic regression for survival, ANOVA for biomass).

- Identification of Adaptive Markers: Identify specific introgressed markers that are significantly associated with increased fitness (e.g., higher odds of survival) in the novel climate.

Figure 2: Common Garden Experimental Design for validating the fitness benefits of adaptive introgression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Studying Adaptive Introgression

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application in Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| SNP Genotyping Arrays | High-throughput genotyping of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms across the genome. | Identifying genetic ancestry and performing genome scans in Pinus [12] and Pterocarya [18]. |

| Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) Markers | A molecular marker technique used to detect specific genetic variants. | Identifying introgressed regions from P. fremontii associated with survival in P. angustifolia [5] [17]. |

| PCR Reagents & Primers | Amplify specific DNA regions for sequencing, cloning, or marker analysis. | Essential for all genotyping and sequencing workflows, including preparation of libraries for high-throughput sequencing. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (Plant-Specific) | Isolate high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from tough plant tissues. | Used in all cited studies to obtain pure DNA from conifer needles, cottonwood leaves, and other tree tissues [12] [18]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Library Prep Kits | Prepare fragmented and tagged DNA libraries for massive parallel sequencing. | For whole-genome resequencing of parents and hybrids to identify introgressed blocks and candidate genes [18]. |

| Bioinformatics Software (e.g., for FST analysis, ADMIXTURE) | Computational tools for population genetic analysis, ancestry decomposition, and detection of selection. | Assigning individuals to genetic classes and identifying outlier loci in Pinus [12] and Pterocarya [18]. |

The documented cases of adaptive introgression from conifers to riparian hardwoods underscore a unifying evolutionary principle: hybridization serves as a critical mechanism for rapid adaptation. The taxonomic breadth of this phenomenon highlights its general importance in forest ecosystems. For researchers, the integration of genomic analyses in natural populations with long-term common garden experiments provides a robust framework for validating the adaptive value of introgressed alleles. As climate change continues to exert selective pressures, understanding and leveraging adaptive introgression will be fundamental to informing conservation strategies and breeding programs aimed at maintaining resilient forests.

Decoding Nature's Experiments: Genomic Tools for Tracking Introgressed Genes

High-Throughput Sequencing and SNP Genotyping in Natural Hybrid Zones

Adaptive introgression, the natural transfer of beneficial genetic material between species through hybridization and backcrossing, is increasingly recognized as a critical mechanism for rapid evolution. This process enables species to acquire advantageous alleles from closely related taxa, potentially accelerating adaptation faster than de novo mutations, which is particularly vital for long-lived organisms facing rapid climate change [1]. In forest trees, which serve as foundational components of terrestrial ecosystems, adaptive introgression provides a evolutionary pathway to enhance climate resilience by transferring stress-tolerant traits between species [5]. The study of these natural hybrid zones has been revolutionized by high-throughput sequencing technologies and sophisticated SNP genotyping approaches, allowing researchers to precisely identify introgressed genomic regions and quantify their adaptive benefits [19].

For long-generation species like forest trees, adaptive introgression represents a crucial evolutionary leapfrog mechanism, bypassing intermediate evolutionary stages that would require countless generations under natural selection pressures. This process enhances adaptive capacity and can lead to evolutionary rescue for vulnerable populations, potentially determining whether species persist or perish under contemporary climate change scenarios [1]. The genomic revolution has transformed our understanding of hybridization from a primarily homogenizing force to a potentially creative evolutionary mechanism that can promote species divergence under certain circumstances through processes like transgressive segregation [1].

Analytical Frameworks for Detecting Adaptive Introgression

Statistical Methods and Bioinformatics Pipelines

The identification of authentic adaptive introgression requires distinguishing beneficially introgressed regions from neutral gene flow or deleterious genetic material. Several statistical frameworks have been developed to detect signatures of adaptive introgression from genomic data, each with specific applications and limitations as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Statistical Methods for Detecting Adaptive Introgression

| Method | Statistical Approach | Primary Application | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABBA-BABA Statistics | D-statistics comparing allele sharing patterns | Testing for excess allele sharing between species | Significant deviation from null model of no introgression |

| fd Statistics | Ratio of ABBA-BABA patterns | Quantifying introgressed genomic regions | Proportion of genome introgressed between species |

| HyDe | Hypothesis testing using phylogenetic networks | Detecting hybridization from population data | Test statistics for hybrid origin of individuals |

| Twisst | Topology weighting approach | Quantifying gene tree discordance | Relative contributions of different phylogenetic histories |

| SFS-based Methods | Site Frequency Spectrum analysis | Inferring demographic history and selection | Historical population sizes, divergence times |

These methods leverage different aspects of genomic data to detect the distinctive signatures of adaptive introgression, which often includes localized regions of elevated differentiation, unusual linkage disequilibrium patterns, and elevated divergence relative to genomic background [19]. The ABBA-BABA test (also known as the D-statistic) is particularly widely used for detecting introgression between closely related species, while fd statistics build upon this framework to quantify the proportion of introgression in specific genomic regions [19].

The sequential application of these methods typically follows a structured bioinformatics pipeline that begins with raw sequencing data and progresses through increasingly specialized analyses to identify candidate adaptive introgressions, as visualized in the following workflow:

Diagram 1: Bioinformatics workflow for detecting adaptive introgression, progressing from raw data processing to specialized statistical analyses.

Demographic History Inference

Accurately identifying adaptive introgression requires understanding the demographic context in which hybridization occurred. Methods based on the site frequency spectrum (SFS), such as Fastsimcoal2, enable inference of divergence histories and demographic parameters, including population sizes, divergence times, and migration rates [19]. For forest trees, which typically have large effective population sizes and complex demographic histories, these methods are essential for distinguishing true adaptive introgression from other processes that can generate similar genomic patterns, such as incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) [19].

Coalescent-based approaches including PSMC, MSMC, and SMC++ allow researchers to reconstruct historical population size changes over evolutionary timescales, providing crucial context for interpreting contemporary patterns of genetic variation [19]. These methods have revealed how past climate fluctuations have shaped the genomes of foundation tree species like poplar, oak, and ginkgo, creating the genomic background upon which contemporary adaptive introgression occurs [19].

High-Throughput Sequencing Methodologies

Whole Genome Sequencing Approaches

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) provides the most comprehensive approach for characterizing hybrid zones, enabling unbiased discovery of variants across the entire genome. For large-genome species like trees, skim-sequencing (skim-seq) has emerged as a cost-effective WGS alternative that sequences genomes at low coverage (typically 0.01× to 1×) while still providing sufficient data for genotyping and structural variant detection [20].

The skim-seq approach utilizes optimized low-volume Illumina Nextera chemistry, which employs a transposome complex to simultaneously fragment DNA and ligate adapters in a single step (tagmentation) [20]. This method significantly streamlines library preparation compared to traditional approaches, enabling multiplexing of up to 960 samples in a single sequencing run using dual index barcoding, with potential for expansion to 3,072 samples [20]. The efficiency of this workflow makes large-scale hybrid zone studies feasible, as depicted below:

Diagram 2: Skim-seq workflow using Nextera tagmentation for efficient library preparation.

The applications of skim-seq in hybrid zone studies are diverse, including genotyping of segregating populations, identification and characterization of translocations, assessment of chromosome dosage and aneuploidy, and karyotyping of introgression lines [20]. For species with large genomes, this approach provides an optimal balance between cost and genomic coverage, making large-scale population studies feasible.

Reduced-Representation Sequencing

Reduced-representation approaches provide cost-effective alternatives to WGS by targeting specific subsets of the genome. Restriction-site-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq) and genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) use restriction enzymes to reduce genome complexity, generating consistent subsets of loci across multiple individuals [20]. These methods are particularly valuable for non-model species without reference genomes, as they don't require prior genomic information [20].

Sequence capture methods represent another reduced-representation approach, using oligonucleotide probes to enrich specific genomic regions prior to sequencing. While this method requires upfront probe design and synthesis, it provides more consistent coverage of targeted regions across samples compared to enzyme-based methods [20]. The selection between these approaches depends on research goals, genomic resources, and budget constraints, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparison of High-Throughput Sequencing Approaches for Hybrid Zone Studies

| Method | Coverage | Cost per Sample | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Complete genome | High | De novo variant discovery, structural variants | Costly for large sample sizes |

| Skim-Seq | 0.01×-1× genome | Low-Medium | Large populations, aneuploidy detection | Lower coverage limits some applications |

| RAD-Seq/GBS | 1-5% of genome | Low | Genetic mapping, population structure | Locus dropout, reference bias |

| Sequence Capture | Targeted regions | Medium | Candidate gene studies, comparative genomics | Requires probe design, fixed target set |

| RNA-Seq | Transcriptome | Medium | Gene expression, functional annotation | Tissue-specific, complex normalization |

SNP Genotyping Technologies

High-Throughput SNP Arrays

SNP genotyping arrays provide a cost-effective solution for high-throughput screening of known variants in large populations. These arrays enable rapid genotyping of hundreds to thousands of individuals at predetermined SNP positions, making them ideal for monitoring programs and breeding applications [21]. The development of a SNP array follows a structured process beginning with variant discovery through whole-genome resequencing of representative individuals, followed by stringent filtering to identify high-quality SNPs, and finally assay design and validation [21].

The Illumina GoldenGate platform represents one widely used SNP genotyping technology that employs a three-oligonucleotide system for each SNP locus: two allele-specific oligos (ASO1 and ASO2) and one locus-specific oligo (LSO) containing a unique address sequence [22]. The assay involves DNA activation, oligonucleotide hybridization, extension and ligation, universal PCR, and finally array hybridization and fluorescence scanning [22]. The resulting intensity values are analyzed using clustering algorithms to assign genotypes (AA, AB, BB) with associated quality scores.

Several factors influence SNP assay success rates, particularly in non-model species. The presence of exon-intron boundaries in flanking sequences accounts for approximately 50% of assay failures, while secondary SNPs, indels, paralogous genes, and repetitive sequences also contribute to reduced performance [22]. Careful SNP selection and assay design can significantly improve success rates; in Acacia hybrids, optimized approaches achieved 92.4% assay success and 57.4% conversion rates for 768-plex genotyping [22].

Applications in Monitoring and Conservation

SNP arrays have significant utility in monitoring invasion dynamics and conservation genetics. For the invasive comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi, a customized 116-SNP array successfully distinguished between northern and southern lineages, enabling tracking of invasion sources and pathways [21]. This approach provided comparable results to whole-genome resequencing with 832,323 SNPs in terms of genetic differentiation estimates and population structure, while being substantially more cost-effective for large-scale monitoring [21].

In forest trees, SNP arrays facilitate the monitoring of genetic diversity in natural populations, identification of admixed individuals, and detection of adaptive introgression events. This information is crucial for conservation decisions, including assisted migration, genetic rescue, and prioritization of populations for conservation [19]. The long-term nature of forest tree generation times makes these efficient monitoring tools particularly valuable for tracking evolutionary changes over management-relevant timescales.

Case Study: Adaptive Introgression in Populus Under Climate Change

A landmark 31-year common garden experiment with Populus fremontii and Populus angustifolia provides compelling evidence for adaptive introgression enhancing climate change resilience [5]. This long-term study examined growth and survival of pure species, F1 hybrids, and backcross genotypes in a warm, low-elevation garden representing future climate conditions. The experimental design and key findings are summarized below:

Diagram 3: Long-term common garden experimental design for detecting adaptive introgression in Populus.

After three decades, striking survival differences emerged among cross types: approximately 90% of warm-adapted P. fremontii and 100% of F1 hybrids survived, compared to only 30% of backcross hybrids and 25% of cool-adapted P. angustifolia [5]. Most significantly, survival among the vulnerable P. angustifolia and backcross genotypes was strongly associated with introgression of specific P. fremontii markers, particularly RFLP-1286 [5]. Individuals carrying this marker showed approximately 75% greater survival, with all backcross individuals possessing this marker remaining alive after 31 years [5].

This case study demonstrates several key principles of adaptive introgression: (1) introgression can provide climate resilience traits, (2) the adaptive value of introgressed alleles becomes increasingly important under climatic stress, and (3) long-term studies are essential for detecting fitness consequences in long-lived species. The findings have important implications for conservation strategies under climate change, suggesting that managed hybridization or protection of natural hybrid zones may enhance ecosystem resilience.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of adaptive introgression in hybrid zones requires specialized reagents and analytical tools. Based on the methodologies discussed, Table 3 compiles essential research solutions for conducting such studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for High-Throughput Hybrid Zone Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Illumina Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit | Tagmentation-based library construction | Enables low-volume, high-throughput processing |

| Custom DNA Oligos & Barcodes | Sample multiplexing | Dual-indexing allows for thousands of unique combinations | |

| Genotyping | Illumina GoldenGate Assay | Medium-throughput SNP genotyping | Optimal for 96-1,536 SNP multiplexing |

| Custom SNP Arrays | High-throughput screening | Ideal for monitoring programs with known variants | |

| Sequencing | Illumina Platform Reagents | DNA sequencing | Various platforms suitable for different throughput needs |

| Quality Control Kits (e.g., Bioanalyzer) | Library QC | Essential for optimizing sequencing efficiency | |

| Bioinformatics | BWA, Bowtie2 | Read alignment | Mapping reads to reference genomes |

| GATK Suite | Variant calling | Industry standard for SNP/indel discovery | |

| Fastsimcoal2, PSMC | Demographic inference | Reconstruction of historical population sizes | |

| fd, ABBA-BABA Statistics | Introgression detection | Quantifying and testing gene flow between species | |

| Field Collections | DNA Preservation Buffers | Sample stabilization | Maintain DNA integrity during transport |

| Herbarium Specimen Materials | Voucher preservation | Essential for verifying species identification |

The selection of appropriate reagents and methods should be guided by research objectives, genomic resources available for the study system, and scale of the investigation. For non-model systems, investment in initial genomic resource development (e.g., reference genomes, transcriptomes) is often necessary before targeted studies of adaptive introgression can proceed efficiently.

High-throughput sequencing and SNP genotyping technologies have transformed our ability to detect and characterize adaptive introgression in natural hybrid zones, revealing this process as a significant evolutionary force in forest trees and other long-lived species. The integration of these genomic approaches with long-term ecological studies, such as common garden experiments, provides powerful insights into how hybridization may enhance climate resilience through the transfer of beneficial alleles. As climate change accelerates, understanding and potentially facilitating adaptive introgression through informed conservation strategies may prove crucial for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function. The methodological framework presented here offers researchers a comprehensive toolkit for investigating these evolutionary processes across diverse biological systems.

Foundation tree species, defined as those that create and stabilize environmental conditions necessary for the survival of numerous other species, play disproportionately critical roles in ecosystem structure and function [23]. Among these ecological linchpins, cottonwoods (Populus spp.) represent model systems for understanding ecological genetics and evolutionary responses to environmental change [24]. Specifically, Populus fremontii (Fremont cottonwood) is recognized as one of the most important foundation species in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, structuring communities across multiple trophic levels, driving ecosystem processes, and influencing biodiversity via genetic-based functional trait variation [23]. However, the geographic extent of P. fremontii has declined dramatically over the past century due to surface water diversions, non-native species invasions, and more recently, climate change [23]. Consequently, P. fremontii gallery forests are now considered among the most threatened forest types in North America [23].

Compounding these climate-induced reductions in riparian habitat is the successful invasion of Tamarix (tamarisk or salt cedar), which has replaced native Populus stands along many major river systems [23]. Once established, Tamarix increases soil salinity, alters hydrology, reduces native vegetation cover, and disrupts belowground mycorrhizal fungal communities upon which native trees like P. fremontii depend [23]. This combination of abiotic and biotic pressures has created a selective regime demanding rapid evolutionary responses for species persistence. Within this context, hybridization between P. fremontii and closely related species, particularly P. angustifolia (narrowleaf cottonwood), has emerged as a potentially critical mechanism for rapid adaptation to changing conditions [25] [26]. This case study examines the genomic, ecological, and evolutionary dimensions of climate resilience in these foundation tree species, with particular emphasis on the role of adaptive introgression as a mechanism for evolutionary rescue amid rapid environmental change.

Genomic Framework and Adaptive Potential

Population Genomics and Local Adaptation

Populus fremontii exhibits substantial genetic variation across its range, which extends from Mexico, Arizona, and California northward into Nevada and Utah [23]. Population genomic studies utilizing restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RADseq) and ~9,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have revealed that P. fremontii is strongly differentiated into three primary genetic groups: the Utah High Plateau (UHP), Sonoran Desert (SD), and California Central Valley (CCV) ecotypes [23]. This genetic structure strongly correlates with variation in key environmental variables, particularly minimum temperature of the coldest month, precipitation seasonality, and mean temperature of the coldest quarter, supporting a hypothesis of strong niche differentiation and local adaptation [23].

P. angustifolia, in contrast, occupies generally higher elevation sites and displays different adaptive trajectories. Research on sky island populations of P. angustifolia has demonstrated significant phenotypic divergence from adjacent mountain chain populations in traits related to both reproduction and productivity [27]. Common garden studies have revealed that sky island populations show 34% higher rates of cloning (asexual reproduction) and produce 52% more aboveground biomass than populations from adjacent mountain chains, suggesting adaptive responses to hotter, drier conditions [27]. These trait differences appear to be driven by different evolutionary mechanisms: natural selection for increased aboveground biomass and genetic drift for increased cloning capacity [27].

Hybridization as an Evolutionary Mechanism

Natural hybridization between P. fremontii and P. angustifolia creates extensive hybrid zones that serve as natural laboratories for studying adaptive introgression [25] [24]. These zones facilitate the transfer of adaptive alleles across species boundaries, potentially providing novel genetic variation for responding to environmental change [26]. The genomic architecture of these hybrid systems has been extensively mapped using a combination of molecular markers, including amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLPs), simple sequence repeats (SSRs), and restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) [24] [28].

Table 1: Genomic Resources for Populus Hybrid Research

| Resource Type | Specific Tools | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Markers | 541 AFLP, 111 SSR markers [24] | Construction of dense linkage maps across 19 linkage groups |

| Genetic Mapping | RFLP markers (e.g., RFLP-1286, RFLP-755, RFLP-754) [25] | Identification of marker-trait associations for climate adaptation |

| Genomic Sequencing | RADseq, ~9,000 SNPs [23] | Population genomics and identification of locally adapted loci |

| Pedigree Resources | 246 backcross (BC₁) progeny [24] | Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping of ecologically important traits |

A key finding from long-term common garden experiments is that hybrid introgression is associated with enhanced survival in warmer, drier climates. Specifically, the presence of introgressed P. fremontii markers in P. angustifolia and backcross genotypes significantly increases survival odds under climate stress [25]. For example, backcross hybrid and P. angustifolia trees carrying the P. fremontii marker RFLP-1286 showed approximately 75% greater survival after 31 years in a warm common garden compared to trees without this marker [25]. Importantly, all backcross individuals with this marker remained alive at the end of the 31-year study, demonstrating the potential adaptive value of introgressed alleles [25].

Figure 1: Adaptive Introgression Workflow in Populus Hybrids. This diagram illustrates the pathway through which hybridization and subsequent backcrossing, followed by natural selection, can lead to adaptive introgression and enhanced climate resilience.

Experimental Evidence from Common Gardens and Hybrid Zones

Reciprocal Common Garden Networks

A powerful approach for investigating genetic variation, patterns of local adaptation, and phenotypic plasticity in forest trees involves the use of experimental common gardens [23]. For Populus species, a successfully constructed reciprocal common garden network was established in 2014 using cuttings collected from 12 genotypes per 16 source populations representing two distinct ecoregions - the Utah High Plateau and Sonoran Desert ecoregions [23]. These gardens span an elevation gradient of almost 2,000 meters, encompassing a wide range of temperature extremes experienced by P. fremontii, from mean annual temperatures of 10.7°C at the highest elevation garden to 22.8°C at the low-elevation garden [23].

The experimental design incorporates over 4,000 trees planted in four replicated blocks across three garden sites, allowing researchers to disentangle genetic from environmental influences on phenotypic traits [23]. This design facilitates investigation of key mechanisms for coping with environmental challenges, including the expression of leaf/canopy traits required to balance trade-offs between minimizing plant hydraulic dysfunction and minimizing canopy thermal stress, and the maintenance of mycorrhizal symbionts in the presence of climate change and Tamarix invasion [23].

Long-Term Hybrid Performance

A 31-year common garden experiment has provided particularly compelling evidence for the role of hybridization in climate adaptation [25]. This long-term study planted genotypes of P. fremontii, P. angustifolia, F₁ hybrids, and F₁ × P. angustifolia backcross hybrids in a low-elevation, warm common garden, effectively imposing climate change conditions on trees originating from various elevations [25]. The results revealed striking differences in survival among cross types: approximately 90% of the low-elevation-adapted P. fremontii and 100% of F₁ hybrid genotypes survived, while only about 30% of backcross hybrid and 25% of P. angustifolia genotypes survived over the 31-year period [25].

Table 2: Survival and Biomass Accumulation in a 31-Year Common Garden Experiment [25]

| Cross Type | Survival Rate (%) | Relative Biomass Accumulation | Climate Transfer Distance Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. fremontii | ~90% | High (reference) | Minimal impact (locally adapted) |

| F₁ Hybrid | ~100% | Highest (heterosis) | Minimal impact |

| Backcross Hybrid | ~30% | 37% lower than P. fremontii | 7.5% decreased odds of survival per 1°C increase |

| P. angustifolia | ~25% | 37% lower than P. fremontii | 7.5% decreased odds of survival per 1°C increase |

The study also demonstrated that survival among the more vulnerable P. angustifolia and backcross trees was strongly influenced by transfer distance - both geographic and climatic - with trees originating from populations closer and more climatically similar to the common garden site having higher survival rates [25]. For each 1°C increase in mean annual temperature between source populations and the common garden, the odds of survival decreased by 7.5%, with greater than 90% mortality observed when the temperature difference exceeded 4°C [25]. This provides compelling evidence that climate transfer distance serves as a powerful proxy for predicting climate change impacts on tree populations.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Hybrid Zone Mapping and Genotyping

The study of adaptive introgression in Populus requires sophisticated genomic methodologies. A standard protocol involves:

Pedigree Construction: Crossing a naturally occurring F₁ hybrid (P. fremontii × P. angustifolia) with a pure P. angustifolia from the same population to produce backcross (BC₁) mapping progeny [24]. Typical mapping populations consist of 246 or more full-sib backcross progeny [24].

DNA Extraction: Collecting fresh leaves from parents and progeny during the height of the growing season, freezing on dry ice (sometimes lyophilizing), and extracting DNA using either standard CTAB protocols or commercial kits such as the Qiagen DNeasy plant miniprep kit [24].

Marker Analysis: Conducting AFLP analysis using the method of Vos et al. (1995) with modifications from Travis et al. (1996) [24]. Preselective amplification is conducted using adenine (A) as the first selective base, followed by selective amplification with 3+3 primer combinations (EcoRI+AXX/MseI+AXX) [24].

SSR Analysis: Screening a subset of individuals with SSR markers derived from the Populus trichocarpa whole-genome sequencing project. Amplification products are typically analyzed on an ABI3730 automated capillary electrophoresis instrument [24].

Linkage Analysis: Constructing linkage maps using software such as JoinMap or MapMaker with markers showing expected 1:1 segregation ratios for testcross configurations [24]. The resulting linkage maps typically distribute markers across 19 linkage groups, corresponding to the haploid chromosome number in Populus [24].

Common Garden Establishment

The protocol for establishing reciprocal common gardens includes:

Propagule Collection: Collecting hardwood cuttings from multiple genotypes (typically 12 or more) per source population during dormancy [23]. Cuttings should represent the major ecoregions and genetic groups within the species' range.

Site Selection: Establishing gardens across major environmental gradients, particularly elevation gradients that capture the temperature and precipitation variation experienced by the species [23]. Each garden should have uniform soils and environmental conditions.

Experimental Design: Planting cuttings in randomized complete block designs with multiple replicates (typically 4 blocks) to account for microenvironmental variation [23]. Standard spacing (e.g., 2×2 meters) allows for adequate growth and reduces competition.

Trait Measurements: Monitoring survival, growth, phenology, physiology, and reproductive traits over multiple years [23] [25]. Key measurements include aboveground biomass, cloning capacity (ramet production), leaf traits, hydraulic function, and bud phenology.

Figure 2: Common Garden Experimental Workflow. This methodology allows researchers to disentangle genetic from environmental influences on phenotypic traits critical for climate adaptation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Populus Evolutionary Genomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| AFLP Marker System | Genome-wide scanning without prior sequence knowledge | EcoRI+AGG/MseI+ACC primer combinations [24] |

| SSR (Microsatellite) Markers | Fine-scale mapping and comparative genomics | 341 SSR markers from P. trichocarpa genome project [24] |

| RFLP Probes | Tracking specific introgressed chromosomal regions | RFLP-1286, RFLP-755, RFLP-754 as adaptive markers [25] |

| RADseq Protocol | Population genomics and SNP discovery | ~9,000 SNPs for population structure analysis [23] |

| Common Garden Network | Disentangling genetic and environmental effects | Three-garden network across 2,000 m elevation gradient [23] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality DNA for multiple applications | Qiagen DNeasy plant miniprep kit [24] |

Ecological and Evolutionary Implications

Community and Ecosystem Consequences

The evolutionary dynamics of foundation species like Populus have profound consequences for associated communities and ecosystem processes. Genetically based variation in cottonwood phytochemistry, morphology, and phenology has been shown to affect populations, communities, and ecosystem processes at multiple scales, from individual trees to stands, rivers, and entire regions [24]. These effects extend to diverse organisms including microbes, fungi, arthropods, birds, and mammals, creating genetically based community structure [24].

Hybridization-induced changes in plant traits can alter ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling and decomposition rates [24]. For example, genetically based differences in herbivore susceptibility among Populus species and their hybrids influence aquatic leaf litter decomposition rates and carbon cycling [25]. Similarly, ecosystem-level carbon budgets vary with tree cross type both in field studies and common gardens, demonstrating the ecosystem-level consequences of evolutionary processes [25].

Conservation and Management Applications

Understanding adaptive introgression in foundation tree species has direct implications for conservation and restoration strategies in rapidly changing environments. The evidence for adaptive introgression suggests that hybrid-specific conservation policies may be necessary to preserve the evolutionary potential of foundation species [25]. This represents a paradigm shift from traditional conservation approaches that often focused on preserving "pure" species and viewed hybridization primarily as a threat to genetic integrity.

Restoration efforts for threatened P. fremontii gallery forests may benefit from selecting naturally occurring populations and genotypes with traits that maximize resource use efficiency during periods of resource limitation and maximize resource uptake efficiency during brief resource pulses [23]. Furthermore, the identification of specific genetic markers associated with climate adaptation (e.g., RFLP-1286) provides potential tools for marker-assisted selection in restoration programs [25].

Remote sensing technologies offer promising approaches for scaling these findings from genes to ecosystems. High spatial and spectral resolution remote sensing can detect key traits in common gardens and natural populations, potentially allowing landscape-level assessment of adaptive capacity [23]. This integration of evolutionary genomics with remote sensing and landscape ecology creates powerful frameworks for forecasting ecosystem responses to climate change and prioritizing conservation interventions.

The case of Populus fremontii and P. angustifolia illustrates how adaptive introgression through hybridization can serve as a critical mechanism for rapid evolution in foundation tree species facing climate change. The transfer of adaptive alleles across species boundaries provides genetic variation that enhances survival and performance under warmer, drier conditions, as demonstrated by long-term common garden experiments [25]. This evolutionary process has cascading effects on community structure and ecosystem function, emphasizing the importance of considering evolutionary processes in conservation planning and ecosystem management [24].

The genomic resources and experimental protocols developed for Populus research provide a powerful toolkit for investigating adaptive evolution in other forest trees [24] [26]. The integration of population genomics, common garden experiments, and ecological studies offers a model system for understanding how long-lived species respond to rapid environmental change. As climate change continues to alter selective pressures across global landscapes, the insights gained from Populus hybridization studies may prove invaluable for predicting and managing the responses of foundation species worldwide.

Future research should focus on identifying the specific genes underlying adaptive traits, understanding the ecological mechanisms that maintain hybrid zones, and developing conservation strategies that incorporate the evolutionary potential provided by natural hybridization. Such integrative approaches will be essential for preserving foundation species and the diverse ecosystems that depend on them in an era of rapid global change.

Forest tree species are facing unprecedented challenges from rapid climate change, including increased drought stress, heat waves, and altered freeze-thaw cycles [29] [30]. For long-lived species with generation times spanning decades to centuries, the pace of adaptive evolution through de novo mutation may be insufficient to track these environmental shifts. Within this context, adaptive introgression—the natural transfer of beneficial genetic material between species through hybridization and backcrossing—has emerged as a critical evolutionary mechanism that can fuel rapid adaptation [1] [5]. This case study examines how adaptive introgression functions between two closely related five-needle pines, Pinus strobiformis (southwestern white pine) and Pinus flexilis (limber pine), providing a model system for understanding evolutionary resilience in forest trees.