Advancing Molecular Dating: From Computational Speed to Biological Accuracy in Evolutionary Studies

Molecular dating, the inference of evolutionary timescales from genetic sequences, is fundamental for connecting biological evolution to geological time.

Advancing Molecular Dating: From Computational Speed to Biological Accuracy in Evolutionary Studies

Abstract

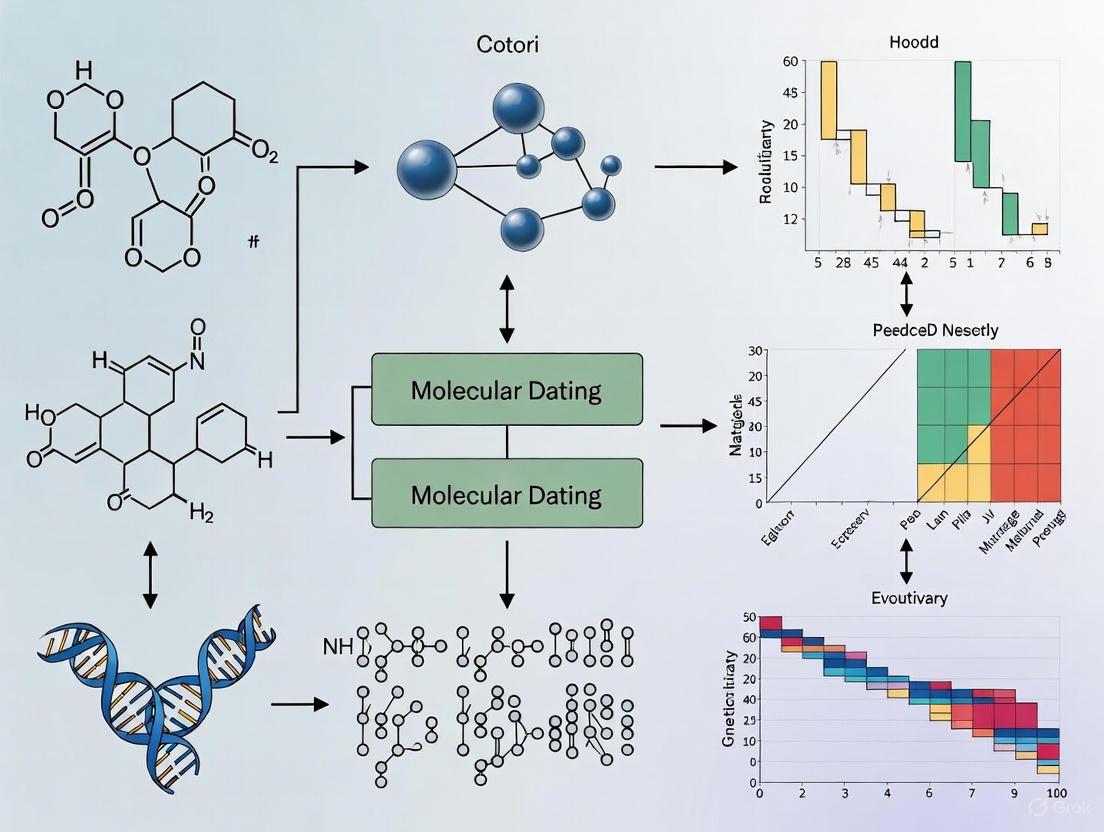

Molecular dating, the inference of evolutionary timescales from genetic sequences, is fundamental for connecting biological evolution to geological time. This article synthesizes recent advances in computational methods, calibration techniques, and model development that are revolutionizing the field. We explore the rise of fast dating methodologies like the Relative Rate Framework and Penalized Likelihood, which offer significant computational advantages for large phylogenomic datasets. The article further details the critical integration of diverse fossil data and horizontal gene transfers for robust calibration, examines key factors influencing date accuracy and precision, and provides a comparative analysis of method performance against Bayesian benchmarks. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting, applying, and validating molecular dating approaches in the era of massive genomic data, with direct implications for understanding disease evolution, host-pathogen interactions, and the timeline of life.

The Molecular Clock Foundation: Core Principles and Modern Challenges

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Rate Heterogeneity in Your Dataset

Problem: My molecular dating analysis yields inconsistent divergence times with poor statistical support. Could rate variation be the cause?

Solution: This guide helps you identify and diagnose rate variation affecting your molecular clock analysis [1].

| Step | Investigation | Key Questions to Ask | Supporting Tools or Tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initial Data Inspection | Do sister branches have highly variable lengths? Does a likelihood ratio test reject a strict clock model? | Phylogenetic tree visualization, Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) [1]. |

| 2 | Identify Anomalous Lineages | Are there specific lineages or clades with significantly accelerated or decelerated evolutionary rates? | Relative-rate tests (e.g., Tajima's test), Local molecular clock models [1]. |

| 3 | Assess Data-Driven Patterns | Does rate variation appear to be gradual across the tree or concentrated in specific shifts? | evorates software for inferring gradually evolving rates, Bayesian Analysis [2]. |

| 4 | Model Selection | Which model of rate evolution (e.g., local clock, relaxed clock, rate-smoothing) best fits my data? | Comparison of AIC/BIC scores from different models, Bayesian model averaging [1]. |

Detailed Protocol: Relative-Rate Test

Objective: To test if two sister lineages have evolved at significantly different rates [1].

- Select Taxa: Choose three taxa: two sister lineages (Taxon A and Taxon B) to test and an outgroup (Taxon O) to root the comparison.

- Calculate Distances: Compute the pairwise genetic distances (e.g., p-distance, Kimura 2-parameter) between A-O, B-O, and A-B.

- Perform Test: Use software like

HYPHYorMEGAto conduct a formal relative-rate test (e.g., Tajima's test). The test statistically evaluates whether the distance from A to O is equal to the distance from B to O. - Interpret Results: A significant p-value (typically < 0.05) indicates that one lineage has evolved at a different rate than the other. This lineage may need to be excluded or assigned its own rate in a local clock model [1].

Guide 2: Resolving Model Inadequacy and Underfitting

Problem: My chosen molecular dating model seems to underfit the data, failing to capture complex rate variation patterns [2].

Solution: Implement a more flexible, data-driven model that can capture gradual rate changes.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low statistical support for a single, constant rate. | Model underfitting due to unaccounted rate heterogeneity [2]. | Switch to a relaxed clock model. | Method: Implement an autocorrelated relaxed clock (e.g., evorates).Benefit: Models rates as gradually evolving, capturing phylogenetic autocorrelation [2]. |

| A few lineages have extremely long or short branches. | Presence of "rate outlier" lineages [1]. | Use a Local Molecular Clock or exclude anomalous lineages. | Method: Apply a Local Molecular Clock model.Benefit: Assigns distinct rates to specific clades, handling large, discrete rate shifts [1]. |

| Inability to detect a general trend (e.g., Early Burst) due to lineage-specific variation. | "Residual" rate variation masks overall trend [2]. | Use a trend model that accounts for residual variation. | Method: Use evorates with a trend parameter.Benefit: More sensitively detects overall rate slowdowns (EB) or speedups (LB) despite lineage-specific anomalies [2]. |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing an evorates Analysis

Objective: To infer patterns of gradual, stochastic rate variation across a phylogeny [2].

- Input Data Preparation: Prepare a rooted, time-calibrated phylogeny with branch lengths proportional to time and a univariate continuous trait (e.g., body size) for the tip taxa. Raw trait measurements are preferred over multivariate ordinations [2].

- Software Configuration: Install the

evoratesR package. Set up the Bayesian analysis, specifying priors for the rate variance (controls how quickly rates diverge) and trend (determines if rates tend to decrease or increase over time) parameters [2]. - Run Analysis: Execute the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation to sample from the posterior distribution of parameters and branch-specific rates. Run the chain for a sufficient number of generations to ensure convergence.

- Output Interpretation: Analyze the posterior distributions. A trend parameter significantly less than 0 indicates an Early Burst-like slowdown. A rate variance parameter greater than 0 confirms substantial gradual rate variation. Visualize branch-wise rates on the phylogeny to identify lineages with anomalously high or low trait evolution rates [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use a local molecular clock versus a fully relaxed model?

A1: Use a local molecular clock when you have prior evidence or hypothesis about specific clades having different rates (e.g., from relative-rate tests) and the rate changes are relatively infrequent [1]. Use a fully relaxed model (like evorates) when you suspect rates have changed gradually and stochastically across the entire tree in a more complex pattern, influenced by many factors [2].

Q2: My analysis shows strong rate heterogeneity. How can I improve the accuracy of my divergence time estimates?

A2: First, ensure you are using a model that adequately fits the pattern of rate variation, such as the evorates model for gradual change [2]. Second, incorporate reliable fossil calibrations to provide absolute time constraints. Finally, consider using a combined approach: identify and model major rate shifts with a local clock, while applying a relaxed model to account for residual, gradual variation across the rest of the tree [1].

Q3: What are the practical implications of switching from a strict to a relaxed molecular clock for drug development research? A3: For research tracing the evolution of pathogen drug resistance or host-pathogen co-evolution, relaxed clocks provide more accurate timelines of key events. This helps identify the chronological order of mutations conferring resistance and correlates them with historical drug deployment, ultimately improving evolutionary models used to predict future resistance trends [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key methodological "reagents" essential for conducting modern analyses of rate variation.

| Item Name | Function in Analysis | Brief Explanation of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Relative-Rate Test | Identify lineages with significantly anomalous evolutionary rates [1]. | Used as a diagnostic tool to test the null hypothesis that two lineages evolve at the same rate, informing subsequent model choice. |

| Local Molecular Clock | Model large, discrete shifts in substitution rate at specific points in the phylogeny [1]. | Applied when prior evidence (e.g., from tests) suggests a few clades have distinct, constant rates from the rest of the tree. |

evorates Model |

Infer how trait evolution rates vary gradually and stochastically across a clade [2]. | A Bayesian method used to estimate a "rate variance" parameter and branch-wise rates, ideal for modeling complex, autocorrelated rate evolution. |

| Bayesian MCMC | Efficiently fit complex models with many parameters and account for uncertainty [2]. | The computational engine behind methods like evorates, used to estimate the posterior distribution of rates and divergence times. |

Conceptual Evolution of Molecular Clock Models

Experimental Protocol for Rate Variation Workflow

FAQs: Addressing Core Conceptual Challenges

FAQ 1: Why do my molecular date estimates have such wide confidence intervals, even with a large amount of sequence data?

Wide confidence intervals often stem from inherent biological variation and model selection. Key factors include:

- Substitution Rate Heterogeneity: The rate of molecular evolution is not constant. It can vary significantly between species, between genes, and even between sites within a single gene [3]. This variability introduces substantial uncertainty into the conversion of genetic differences into time estimates.

- Limited Phylogenetic Signal: Single genes often contain a limited amount of information (phylogenetic signal) for robustly estimating divergence times, especially for ancient events. Features such as shorter sequence alignments, high rate heterogeneity between branches, and a low average substitution rate all reduce statistical power and increase uncertainty [3].

- Inappropriate Clock Model: Using an overly simplistic model (like a strict clock) when rates are variable, or selecting a relaxed clock model that does not match the true pattern of rate variation across the tree (e.g., using an uncorrelated clock when rates are highly autocorrelated), can lead to increased uncertainty and bias [4].

FAQ 2: My analysis is yielding consistently biased (older/younger) age estimates compared to the known fossil record. What could be causing this?

Systematic biases often point to issues with calibration or model misspecification.

- Fossil Calibration Misuse: Incorrectly applied fossil calibrations are a primary source of bias. This includes using fossils that do not represent the correct node, or assigning inappropriate calibration densities (priors) that are too narrow, too wide, or offset from the true divergence time.

- Unmodeled Rate-Speciation Relationship: Evidence shows that substitution rates can be linked to speciation rates [4]. If your dating method assumes that substitution rates and speciation times are independent (as most common priors do), but they are in fact correlated in your data, it can introduce substantial errors. Simulations show that this can lead to average divergence time inference errors of over 90% in extreme cases [4].

- High Rate Heterogeneity: When calibrations are lacking and rate variation between branches is high, the tree prior can introduce biases. Simulations of single-gene trees have revealed that high branch-rate heterogeneity is a key factor leading to biased estimates, not just imprecise ones [3].

FAQ 3: What are the most critical factors influencing the accuracy and precision of a molecular dating analysis, particularly for single-gene trees?

For single-gene trees, where concatenation is not an option and fossil calibrations may only inform speciation nodes, the challenge is pronounced. The most critical factors are [3]:

- Alignment Length: Shorter alignments provide less information, leading to greater deviation from median age estimates and lower precision.

- Branch Rate Heterogeneity: High variability in substitution rates between lineages (modeled by a relaxed clock) undermines dating consistency.

- Average Substitution Rate: Genes with a lower overall rate of evolution contain less temporal information, reducing dating power.

FAQ 4: How does generation time affect the molecular clock, and do I need to account for it?

Yes, generation time is a fundamental correlate of molecular evolution. There is a strong negative correlation between the mutation rate per year and generation time across eukaryotic species [5]. Species with shorter generation times tend to have higher mutation rates per year. This relationship provides a biological explanation for why the "strict" molecular clock is often violated and should be considered when selecting taxa and interpreting results across lineages with diverse life histories.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Inaccurate Date Estimates

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates consistently older or younger than fossils | Incorrect fossil calibration placement or density; Model misspecification. | Review fossil evidence for each calibration node. Check if calibrations are too restrictive. | Recalibrate using vetted fossil data. Use flexible calibration densities (e.g., lognormal, gamma). Test different tree and clock models. |

| Implausibly narrow or wide confidence intervals | Too much or too little rate variation; Insufficient phylogenetic signal. | Run a Tajima's relative rate test. Check for significant rate heterogeneity. | Increase sequence data (more genes/ loci). Test different clock models (strict vs. relaxed). Use appropriate priors on rate variation. |

| High error in simulated datasets | Unmodeled relationship between substitution rate and speciation rate. | Analyze results under different simulated scenarios (e.g., punctuated vs. continuous evolution). | If a link is suspected, consider methods that jointly estimate rates and times without assuming independence. Acknowledge this potential source of error in interpretations. |

Guide 2: Optimizing Experimental Design for Molecular Dating

Step 1: Locus Selection. Prioritize genes with strong phylogenetic signal for your taxonomic group. Empirical studies show that genes under strong negative selection (e.g., involved in core functions like ATP binding) often exhibit less deviation in date estimates, as they tend to have more consistent evolutionary rates [3].

Step 2: Taxon Sampling. Dense taxon sampling can help break long branches and improve the accuracy of rate estimation across the tree. Ensure your sampling strategy includes taxa with known, well-vetted fossil records to provide robust calibration points.

Step 3: Clock Model Selection.

- Strict Clock: Use only if statistical tests (e.g., likelihood ratio test) fail to reject a constant rate of evolution.

- Relaxed Clock: The default for most empirical data. Choose between uncorrelated (e.g., UCLN) and autocorrelated (e.g., ARG) models based on prior knowledge of your system. Performance varies; an uncorrelated lognormal prior has been shown to be more robust under some realistic models of rate variation [4].

Step 4: Calibration. Use multiple, well-justified fossil calibrations. Prefer calibrations that are close to the nodes of interest and based on a solid morphological phylogenetic analysis. The use of a Calibrated Node Prior is standard practice in Bayesian dating software like BEAST2 [3].

Step 5: Sensitivity Analysis. Crucially, repeat your analysis while varying key parameters: the clock model, the tree prior (e.g., Birth-Death vs. Yule), and calibration settings. Consistent results across models increase confidence in your estimates.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Factors Influencing Dating Precision in Single-Gene Trees

This table summarizes findings from an empirical analysis of 5,205 gene alignments from 21 primate species, benchmarked with simulations [3].

| Factor | Impact on Precision | Empirical Observation | Simulation Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment Length | Shorter alignments → Less information → Lower precision | Shorter alignments showed greater deviation from median node age estimates. | Confirmed as a key factor reducing statistical power. |

| Branch Rate Heterogeneity | High heterogeneity → Lower consistency | High rate heterogeneity between branches associated with less consistent dating. | Revealed biases in addition to low precision, especially when calibrations are lacking. |

| Average Substitution Rate | Lower rate → Less temporal signal → Lower power | Genes with low average substitution rates showed larger deviations in date estimates. | Confirmed that a low rate directly limits the information available for dating. |

Table 2: Impact of Rate-Speciation Relationship on Dating Error

This table is based on simulations of phylogenies and sequences under different models of rate variation, reconstructed with common relaxed clock methods [4].

| Simulation Model | Description | Dating Method (Rate Prior) | Average Error in Node Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unlinked Model | Speciation and substitution rates vary independently. | BEAST 2 (Uncorrelated) | 12% |

| Continuous Covariance Model | Speciation and substitution rates covary continuously. | BEAST 2 (Uncorrelated) | Not specified, but errors are substantial. |

| Punctuated Model | Molecular change is concentrated in speciation events. | PAML (Autocorrelated) | Up to 91% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking Dating Accuracy with Simulated Alignments

Methodology Summary: This protocol outlines a process for evaluating the performance of molecular dating methods using simulated sequence data where the true divergence times are known. This allows for the direct quantification of accuracy and precision.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Generate a Reference Phylogeny: Simulate a phylogenetic tree under a specified speciation model (e.g., Birth-Death process). The known node ages in this tree are your "ground truth".

- Evolve Molecular Sequences: Simulate the evolution of DNA or protein sequences along the branches of the reference phylogeny using a substitution model (e.g., GTR+G+I). To incorporate realism, evolve sequences under different models of rate variation [4]:

- Unlinked Model: Evolve sequences with branch-specific rates drawn independently of speciation events.

- Continuous Covariance Model: Specify a relationship where substitution rates and speciation rates covary across the tree.

- Punctuated Model: Concentrate a proportion of all substitutions at speciation events.

- Infer Divergence Times: Analyze the simulated alignments using your chosen molecular dating software (e.g., BEAST2 [3]) under a specified clock model (strict, relaxed uncorrelated, relaxed autocorrelated).

- Compare and Calculate Error: Compare the estimated node ages against the known "ground truth" node ages from Step 1. Calculate the error (e.g., absolute or relative difference) for each node.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Molecular Dating Research |

|---|---|

| BEAST 2 (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis Sampling Trees) | A primary software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. It is used for inferring divergence times using phylogenetic trees aligned to molecular sequence data, incorporating relaxed molecular clock models and fossil calibrations [3] [6]. |

| Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares (PGLS) | A statistical method used to test for correlations between traits (e.g., mutation rate and generation time) while accounting for the non-independence of species due to their shared evolutionary history [5]. |

| Relaxed Clock Models (e.g., Uncorrelated Lognormal) | A class of models that allow the rate of molecular evolution to vary across different branches of a phylogenetic tree, rather than assuming a single, constant rate. This is essential for analyzing most empirical datasets [4]. |

| Fossil Calibration Prior | A probability distribution placed on the age of a node in a phylogeny, based on evidence from the fossil record. This provides the essential temporal framework needed to convert genetic distances into absolute time estimates [3]. |

| Substitution Model (e.g., GTR+G+I) | A mathematical model that describes the process of nucleotide or amino acid substitution over time. Selecting an appropriate model is critical for accurately estimating genetic distances and, by extension, divergence times. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Bayesian MCMC analysis is running extremely slowly, often failing to converge. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A1: Slow MCMC convergence is frequently due to high-dimensional parameter spaces and inefficient proposal mechanisms. The primary solution is to improve the model's gradient calculations. For instance, the PHLASH method introduces a technique to compute the score function (gradient of the log-likelihood) of a coalescent hidden Markov model at the same computational cost as evaluating the log-likelihood itself [7]. This allows for more efficient navigation of the parameter space. Furthermore, leveraging GPU acceleration can dramatically reduce computation time. Ensure your software, like the PHLASH Python package, is configured to use available GPUs [7].

Q2: How can I quantify uncertainty in my estimated population size history or divergence times?

A2: A full Bayesian approach naturally quantifies uncertainty by generating a posterior distribution over the parameters of interest. Instead of relying on a single point estimate, methods like PHLASH draw numerous random, low-dimensional projections from the posterior distribution and average them [7]. This results in an estimator that includes automatic uncertainty quantification, often visualized as credibility bands around the median estimate (e.g., showing wider intervals for periods with fewer coalescent events) [7].

Q3: My analysis seems to have poor resolution for very recent and very ancient time periods. Is this a technical error?

A3: Not necessarily. This is often a fundamental identifiability issue in coalescent theory, not just a computational bottleneck. Certain time periods can be "invisible" if there are too few coalescent events to provide information [7]. For example, very recent history in an expanding population or very ancient history after a bottleneck may be poorly estimated because few lineages coalesce during these times [7]. No algorithm can fully overcome this lack of signal.

Q4: What is an efficient way to infer demographic bottlenecks from genomic data?

A4: An Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) approach is highly effective. This method involves simulating data under a bottleneck model with parameters drawn from prior distributions and then accepting parameters that produce summary statistics close to those from the observed data [8]. This allows for joint inference of the bottleneck's timing, duration, and severity without calculating the exact likelihood, which can be computationally prohibitive [8].

Q5: How do I integrate different types of data, such as genomic sequences and radiocarbon dates, in a Bayesian framework?

A5: The most effective method is to construct unified Bayesian age models. This involves combining the likelihoods of different data types. For example, in woolly mammoth studies, researchers combined radiocarbon dates with complete mitogenomes by generating Bayesian age models from the radiocarbon data and using the genetic data to test phylogenetic and population hypotheses informed by these models [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Prohibitively Long Computation Times

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High-dimensional data | Check the number of loci and sample size in your dataset. | Use dimensionality reduction techniques like the random low-dimensional projections employed in PHLASH [7]. |

| Inefficient likelihood evaluation | Profile your code to see if likelihood calculation is the bottleneck. | Implement or use software with optimized gradient calculations (score function) [7]. |

| Hardware limitations | Monitor CPU/GPU usage during execution. | Utilize a GPU-accelerated software implementation. The PHLASH package is designed for this [7]. |

| Poor MCMC mixing | Check MCMC trace plots for poor exploration and high autocorrelation. | Tune proposal distributions or switch to a Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) sampler that uses gradient information. |

Issue: Memory Overflow Errors with Large Genomic Datasets

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Storing entire MCMC chain in memory | Check the memory footprint of the chain object. | Write MCMC samples to disk in batches instead of holding all samples in RAM. |

| Large covariance matrices | Identify matrices being stored, e.g., for multivariate priors. | Use sparse matrix representations or low-rank approximations where possible. |

| Complex data structures | Profile memory usage of different data objects. | Optimize data structures; for example, use integer arrays instead of character data for sequences. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Approximate Bayesian Computation for Bottleneck Inference

This protocol is adapted from methods used to infer the population bottleneck in non-African Drosophila melanogaster [8].

- Define the Model: Specify a bottleneck model with parameters for the time of recovery ((tr)), duration ((d)), and severity ((f = Nb / N0)), where (N0) is the ancestral population size [8].

- Choose Summary Statistics (𝒮): Select statistics that are informative about the bottleneck, such as the site frequency spectrum, Tajima's D, and measures of linkage disequilibrium (LD) [8].

- Set Priors: Define prior distributions for all model parameters ((θ, ρ, t_r, d, f)).

- Simulate and Reject: For a large number of iterations:

- Draw parameter values from the priors.

- Simulate genomic data under the bottleneck model using these parameters.

- Calculate the summary statistics from the simulated data.

- Accept the parameters if the simulated summary statistics are within a tolerance (ɛ) of the observed statistics.

- Analyze Output: The accepted parameter values form an approximation of the joint posterior distribution, from which estimates and uncertainties can be derived [8].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Age Modeling with Combined Data

This protocol is based on the study of woolly mammoth population dynamics [9].

- Data Collection: Gather two types of data: a large set of radiocarbon dates (e.g., from 626 specimens) and complete mitogenomes (e.g., 131) [9].

- Build the Age Model: Input the radiocarbon dates into a Bayesian age-modeling software (e.g., using OxCal or BChron) to construct a robust chronological framework. This model will estimate the probability distribution for the age of each specimen.

- Genetic Analysis: Use the mitogenomes to build phylogenetic trees and estimate population genetic parameters (e.g., effective population size, genetic diversity).

- Integrated Interpretation: Use the timing of population events (e.g., local disappearances, recolonizations) from the age model to calibrate and interpret the genetic findings. For example, the genetic data can test hypotheses about source populations for recolonization, as inferred from the age-structured fossil record [9].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Demographic Inference Methods [7]

This table summarizes a benchmark of several methods across 12 different demographic models from the stdpopsim catalog. The methods were evaluated based on their Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for estimating historical effective population size.

| Method | Sample Sizes Analyzed | Key Strengths | Computational Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHLASH | n ∈ {1, 10, 100} | Nonparametric estimator; automatic uncertainty quantification; uses both linkage and frequency spectrum information; often most accurate [7]. | Requires more data for best performance with very small samples (n=1) [7]. |

| SMC++ | n ∈ {1, 10} | Incorporates frequency spectrum information; can analyze more than a single sample [7]. | Could not analyze n=100 within 24-hour wall time limit [7]. |

| MSMC2 | n ∈ {1, 10} | Optimizes a composite PSMC likelihood over all pairs of haplotypes [7]. | Could not analyze n=100 within 256 GB RAM limit [7]. |

| FITCOAL | n ∈ {10, 100} | Extremely accurate when the true history matches its model class (e.g., constant size or exponential growth) [7]. | Crashed with n=1; assumes a specific, parametric model form [7]. |

Table 2: Inferred Bottleneck Parameters for Non-African D. melanogaster [8]

| Parameter | Description | Inferred Value |

|---|---|---|

| (t_r) | Time of recovery from the bottleneck | ~0.006 (N_e) generations ago [8] |

| (d) | Duration of the bottleneck | (Inferred as part of the model) |

| (f) | Severity of the bottleneck ((Nb/N0)) | (Inferred as part of the model) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Software | Function in Bayesian Dating |

|---|---|

| PHLASH [7] | A Python software package for Bayesian inference of population size history from whole-genome data. It uses efficient sampling and GPU acceleration. |

| SCRM [7] | A coalescent simulator used for efficiently generating synthetic genomic data under complex demographic models for method validation and ABC. |

| stdpopsim [7] | A standardized catalog of population genetic simulations, providing vetted demographic models and genomic parameters for realistic benchmarking. |

| ABC (Approximate Bayesian Computation) [8] | A statistical framework for inferring posterior distributions when the likelihood function is intractable, by relying on simulation and summary statistics. |

| Bayesian Age Models [9] | Models (e.g., implemented in OxCal) that combine radiometric dates with stratigraphic information to build robust chronological frameworks for integrating genetic data. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Relationship between computational bottlenecks and solutions in Bayesian dating.

Diagram 2: Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) workflow for bottleneck inference.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core difference between an autocorrelated and an uncorrelated clock model? Autocorrelated clock models assume that substitution rates evolve gradually, so closely related lineages have similar rates. In contrast, uncorrelated clock models treat each branch's substitution rate as an independent draw from a common distribution, with no relationship between rates on parent and daughter branches [10] [11] [12].

2. When should I choose an autocorrelated model for my analysis? An autocorrelated model is often more biologically reasonable when you expect that traits influencing evolutionary rate (like generation time or body size) evolve gradually over time [10]. It is particularly suitable when analyzing closely related species that are likely to share similar physiological constraints [12].

3. Under what circumstances might an uncorrelated model be more appropriate? Uncorrelated models can be advantageous when you have reason to believe that evolutionary rates have changed abruptly or are influenced by lineage-specific factors that are not phylogenetically conserved [4] [12]. They are also less computationally intensive.

4. How can an incorrect clock model choice impact my divergence time estimates? Simulation studies show that using an incorrect prior can lead to substantial errors. For instance, when sequences evolved under a punctuated model (where molecular change is concentrated in speciation events) were reconstructed under an autocorrelated prior, errors reached up to 91% of node age [4].

5. Can I test which clock model best fits my data? Yes, Bayesian model comparison techniques, such as those implemented in software like BEAST, allow for formal model testing. You can compare the marginal likelihoods of analyses run under different clock models to select the best fit for your specific dataset [11].

Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance

Table 1: Average Divergence Time Inference Errors Under Different Models of Rate Variation [4]

| Simulated Model of Rate Variation | Inference Method / Rate Prior | Average Error in Node Age |

|---|---|---|

| Unlinked (Rates and speciation vary independently) | Uncorrelated (BEAST 2) | 12% |

| Continuous Covariation (Rates and speciation linked) | Uncorrelated (BEAST 2) | 16% |

| Punctuated (Bursts of change at speciation) | Uncorrelated (BEAST 2) | 20% |

| Punctuated (Bursts of change at speciation) | Autocorrelated (PAML) | 91% |

Table 2: Characteristics of Major Molecular Clock Models [10] [11] [12]

| Model Type | Key Assumption | Biological Justification | Common Software Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Clock | All branches have the same substitution rate. | Useful for very closely related lineages or datasets shown to be clock-like. | BEAST, PAML, MrBayes |

| Autocorrelated Relaxed Clock | Substitution rates evolve gradually; closely related lineages have similar rates. | Physiological traits (e.g., generation time) that influence rate evolve gradually. | PAML (MCMCTree), BEAST (optional) |

| Uncorrelated Relaxed Clock | Substitution rate on each branch is independent of its parent branch. | Lineages undergo abrupt changes in life history or population size. | BEAST (standard), BEAST 2 |

Experimental Protocols for Model Selection and Validation

Protocol 1: Bayesian Model Comparison for Clock Selection

Purpose: To objectively select the best-fitting molecular clock model for a given dataset using Bayesian model comparison.

Materials:

- Aligned molecular sequence dataset (e.g., nucleotide, amino acid)

- Software: BEAST 2 or similar Bayesian dating package [12]

- Calibration information (e.g., fossil constraints)

Methodology:

- Model Setup: Conduct separate phylogenetic analyses with identical calibrations and tree priors, but different clock models (e.g., strict, uncorrelated, autocorrelated).

- MCMC Execution: Run a sufficient number of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) generations for each analysis to ensure effective sample sizes (ESS) > 200 for all key parameters.

- Marginal Likelihood Estimation: Calculate the marginal likelihood for each analysis using methods such as path sampling or stepping-stone sampling [11].

- Model Selection: Compare marginal likelihoods by calculating Bayes Factors. A Bayes Factor > 10 is typically considered strong evidence for one model over another.

Protocol 2: Assessing Model Fit Using Posterior Predictive Simulations

Purpose: To diagnose model inadequacy and identify where a chosen clock model fails to capture patterns in the data.

Materials:

- Output from a Bayesian molecular dating analysis

- Software: Tracer (for diagnostics), R or Python for custom scripts

Methodology:

- Summary Statistic Selection: Choose a relevant test statistic, such as the coefficient of variation of branch rates or the relationship between branch length and node depth.

- Posterior Predictive Simulation: Simulate new datasets using parameters (trees, rates) drawn from the posterior distribution of your original analysis.

- Distribution Comparison: Calculate the test statistic for both the observed data and the simulated datasets. The model is considered inadequate if the observed statistic falls in the tails of the distribution from the simulated data.

- Iterative Refinement: If a model shows poor fit, consider more complex models or models that explicitly incorporate sources of rate variation (e.g., linked speciation-substitution models).

Model Schematic and Workflow

Molecular Clock Model Selection Workflow

Table 3: Key Software and Analytical Resources for Molecular Dating

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST / BEAST 2 | Software Package | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Implements uncorrelated relaxed clocks as standard; co-estimates phylogeny & times [12] |

| PAML (MCMCTree) | Software Package | Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood | Implements autocorrelated relaxed clock models [4] [11] |

| BEAUti | Companion Software | Graphical model setup for BEAST | User-friendly interface for configuring complex models [12] |

| Tracer | Diagnostic Tool | MCMC output analysis | Assesses convergence and effective sample sizes (ESS) [12] |

| FigTree | Visualization Tool | Tree figure generation | Displays time-scaled phylogenetic trees [12] |

| Fossil Calibrations | Data | Node age constraints | Provides absolute time scaling; can use minimum (soft) maximum bounds [10] [11] |

Next-Generation Dating Tools: Fast Methods and Innovative Calibrations

Empirical studies demonstrate that both RelTime (implementing the Relative Rate Framework) and treePL (implementing Penalized Likelihood) are efficient alternatives to computationally intensive Bayesian methods for molecular dating with large phylogenomic datasets [13] [14]. The table below summarizes their relative performance based on analysis of 23 empirical phylogenomic datasets.

| Performance Metric | RelTime | treePL |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed | >100 times faster than treePL; significantly lower demand [13] [14] | Slower than RelTime [13] [14] |

| Node Age Accuracy | Generally statistically equivalent to Bayesian divergence times [13] [14] | Shows consistent differences from Bayesian estimates [13] [14] |

| Uncertainty Estimation | 95% confidence intervals (CIs) show excellent coverage probabilities (~94%) [15] [16] | Consistently exhibits low levels of uncertainty; can yield overly narrow CIs [13] [16] |

| Rate Variation Assumption | Minimizes rate differences between ancestral/descendant lineages individually [13] | Uses a global penalty function to minimize rate changes between adjacent branches [13] |

| Calibration Flexibility | Allows use of calibration densities (e.g., uniform, normal, lognormal) [13] [15] | Requires hard-bounded minimum and/or maximum calibration values [13] [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Methodology

Q: What are the core methodological differences between RelTime and treePL?

A: The methods differ fundamentally in how they handle variation in evolutionary rates:

- treePL (Penalized Likelihood): Applies a global smoothing parameter (λ) to minimize evolutionary rate changes between adjacent branches across the entire tree. This assumes autocorrelation of evolutionary rates, meaning closely related lineages have similar rates [13] [14].

- RelTime (Relative Rate Framework): Evaluates rate differences individually between ancestral and descendant lineages. This approach eliminates the need for a global penalty function and can accommodate situations where sister lineages have very different rates [13] [14].

Q: Under which conditions does RelTime perform particularly well?

A: Simulation studies indicate that RelTime estimates are consistently more accurate, especially when evolutionary rates are autocorrelated or have shifted convergently among lineages [16].

Troubleshooting Experimental Analysis

Q: My treePL analysis is taking a very long time. Is this normal?

A: Yes, this is a recognized characteristic. In comparative studies, treePL was consistently over 100 times slower than RelTime for analyzing the same phylogenomic datasets [13] [14]. The computational burden of treePL is one of its main drawbacks for analyzing very large datasets.

Q: The confidence intervals for my divergence times seem too narrow in treePL. What could be the cause?

A: This is a common finding. Empirical and simulation studies show that treePL time estimates consistently exhibit low levels of uncertainty, and the 95% CIs can have low coverage probabilities, meaning the true divergence time falls within the CI less often than the stated 95% [13] [16]. This "false precision" is often because standard bootstrap approaches for treePL do not fully capture the error caused by rate heterogeneity among lineages [15].

Q: How can I improve confidence interval estimation in RelTime?

A: RelTime uses an analytical method to calculate CIs that incorporates variance from both branch length estimation and rate heterogeneity [15]. Ensure you are using the latest version of MEGA X, which includes this improved analytical approach. This method produces CIs with excellent coverage probabilities, around 94% on average [15] [16].

Q: How should I handle different calibration densities when using treePL?

A: This is a key limitation of treePL. Since it only accepts minimum and maximum bounds, you must convert complex calibration densities (e.g., log-normal) into hard bounds. A common method is to use the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles of the density distribution as the minimum and maximum bounds, respectively [14]. Be aware that this strategy does not consider interactions among calibrations and may lead to an overestimation of variance [15].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Workflow for Performance Comparison

The following workflow is adapted from the large-scale evaluation of 23 empirical datasets [13] [14]. You can use this protocol to compare the performance of RelTime and treePL on your own data.

1. Input Preparation:

- Alignment and Topology: Use the same sequence alignment and fixed tree topology for both methods to ensure a direct comparison.

- Branch Lengths: Estimate all branch lengths (in substitutions per site) in advance using software like MEGA X for consistency [14].

- Calibration Standardization: Extract calibration information from your source. For treePL, derive minimum and maximum bounds from calibration densities (e.g., using the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles). For RelTime, you can set the same densities directly as uniform, normal, or lognormal distributions where supported [14].

2. Running RelTime in MEGA X:

- Perform calculations using the command-line version of MEGA X for reproducibility.

- The confidence intervals (CIs) for divergence times are calculated automatically using the analytical method [15] [14].

3. Running treePL:

- First, run treePL with the

primeoption to select the best optimization parameters. - Perform a cross-validation procedure to optimize the smoothing parameter (λ). A typical setup includes 10 optimization iterations and 1017 simulated annealing iterations, with

cvstartandcvstopparameters set to 1017 and 10⁻¹⁹, respectively [14]. - Use the

thoroughoption for a more rigorous analysis. - To estimate CIs, perform 100 bootstrap replicates and summarize the results in a tool like TreeAnnotator [14].

4. Performance Evaluation:

- Compare the results from both fast methods to a reference, such as a Bayesian timetree.

- Calculate the following metrics for a quantitative comparison [14]:

- Linear Regression: Regress fast dating estimates (RelTime/treePL) against the reference estimates. Use the coefficient of determination (R²) and the slope (β).

- Normalized Average Difference: For each node, calculate the absolute difference between the fast method estimate and the reference estimate, divide by the reference estimate, and average this value across all nodes (expressed as a percentage).

- Precision of Estimates: Compare the width and coverage of the confidence intervals.

Diagram 1: Workflow for comparing RelTime and treePL performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Software

The table below lists essential computational tools and their functions for conducting molecular dating analysis with these fast methods.

| Tool / Resource | Function in Analysis | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MEGA X [15] [14] | Software platform implementing the RelTime method. | Used for relative rate calculations, divergence time inference, and analytical CI estimation. Offers graphical and command-line interfaces. |

| treePL [13] [14] | Software implementing the Penalized Likelihood method. | Used for divergence time inference with a global smoothing parameter. Requires a cross-validation step to optimize the smoothing parameter (λ). |

| BEAST / MCMCTree / PhyloBayes [13] | Bayesian molecular dating software. | Used as a benchmark for evaluating the performance of fast dating methods like RelTime and treePL. |

| TreeAnnotator [14] | Software tool (part of the BEAST package). | Used to summarize the tree samples from the treePL bootstrap procedure into a single target tree with CIs. |

| Calibration Densities [13] [15] | Priors for node ages based on fossil or other evidence. | RelTime can use uniform, normal, and lognormal densities. treePL requires conversion of these densities into hard minimum/maximum bounds. |

Leveraging Horizontal Gene Transfers (HGTs) as Relative Time-Order Constraints

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are relative time-order constraints and how do HGTs create them? A relative time-order constraint establishes that one node in a phylogeny must be older than another, without assigning specific numerical ages. Horizontal Gene Transfers create these constraints because the transfer of a gene between two organisms requires that the donor lineage (the one giving the gene) and the recipient lineage (the one receiving the gene) existed at the same time. Therefore, the evolutionary nodes representing the donor and recipient species must be contemporaneous, providing a relative timing relationship between these two points in the tree of life [17] [18].

FAQ 2: In which fields of research are HGT-derived constraints most valuable? HGT-derived constraints are particularly valuable in fields where the fossil record is sparse or unreliable. This includes:

- Microbial Evolution: Dating the diversification of bacteria and archaea [18].

- Early Eukaryotic Evolution: Resolving deep evolutionary relationships in fungi and other protists where fossils are rare [17].

- Plant Evolution: Understanding the timing of gene transfers from symbionts or pathogens.

FAQ 3: What are the common pitfalls when identifying a true HGT event for dating? Common pitfalls include:

- Insufficient Phylogenetic Support: Relying on weak phylogenetic signals or poor sequence alignment to infer HGT.

- Confounding with Gene Loss: Misinterpreting a pattern caused by extensive gene loss in related lineages as an HGT.

- Database Bias: Over-representation of genomes from certain lineages can skew HGT detection.

- Ancestral vs. Recent Transfer: Incorrectly dating the transfer event by not properly establishing when the HGT occurred relative to the speciation nodes.

FAQ 4: How do I integrate HGT constraints with traditional fossil calibrations? HGT constraints and fossil calibrations are complementary. Fossil calibrations provide absolute minimum and/or maximum age bounds for specific nodes. HGT constraints provide relative timing relationships between nodes that may not have fossil evidence. In a Bayesian dating framework, both types of information can be combined to produce a chronogram where the HGT constraints help to inform the ages of nodes that lack direct fossil evidence, leading to a more refined and accurate timescale for the entire phylogeny [17] [18].

FAQ 5: What software can I use to implement HGT constraints in my molecular dating analysis? One software package that implements the use of relative time constraints, including those from HGT, is RevBayes [18]. This Bayesian phylogenetic tool allows for the incorporation of these constraints in a modular manner alongside a wide range of molecular dating models.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Resolution or Inconsistent Results After Adding HGT Constraints

Problem: Your molecular dating analysis yields poor resolution, inconsistent node ages, or fails to converge after you incorporate HGT constraints.

Solutions:

- Verify the HGT Event: Re-examine the evidence for the HGT. The strength of the constraint depends on the confidence in the HGT identification. Use robust phylogenetic methods and tests (e.g., Approximate Unbiased tests) to confirm the transfer [17].

- Check for Conflicting Constraints: Ensure your HGT constraints do not conflict with each other or with highly reliable fossil calibrations. Conflicting temporal information can lead to non-convergence.

- Adjust Prior Distributions: Review the prior distributions for your fossil calibrations and clock model. Improper priors can overwhelm the signal from the HGT constraints.

- Increase MCMC Iterations: Analyses with complex constraints may require longer Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs to achieve convergence. Check effective sample size (ESS) values to ensure they are sufficient (>200).

Issue 2: Difficulty in Identifying Suitable HGT Events for My Study Group

Problem: You are unable to find well-supported HGT events that can provide constraints for the nodes of interest in your phylogeny.

Solutions:

- Expand Genomic Sampling: A limited taxon sampling can obscure HGT events. Utilize initiatives like the "1000 Fungal Genomes Project" to access broader genomic data [17].

- Systematic Screening: Perform a systematic and conservative screening of gene families across your study group and outgroups. Look for genes with strong phylogenetic discrepancies that are best explained by HGT rather than other evolutionary forces [17].

- Focus on Functional Traits: Investigate genes for known functional traits (e.g., metabolic enzymes, virulence factors) that are suspected to have been transferred, as these can be good candidates [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Identifying and Applying HGT Constraints

Objective: To systematically identify HGT events and formally integrate them as relative time-order constraints in a Bayesian molecular dating analysis.

Materials:

- Genomic data for the ingroup and outgroup taxa.

- High-performance computing cluster.

- Phylogenetic software (e.g., PhyloBayes, RevBayes).

- Sequence alignment tools (e.g., MAFFT, MUSCLE).

Methodology:

- Genome and Marker Selection: Assemble a phylogenetically broad and diverse genomic dataset. Select hundreds of phylogenetic protein markers to build a robust supermatrix [17].

- Phylogenetic Inference: Reconstruct a species tree using models that account for site-heterogeneity (e.g., the CAT-PMSF model) to mitigate long-branch attraction, which can confound both tree topology and HGT detection [17].

- HGT Detection: For each gene family, perform individual gene tree reconstructions and compare them to the species tree. Identify strongly supported conflicts that indicate HGT.

- Constraint Formulation: For each robust HGT event, define the relative time constraint. For example, if a gene was transferred from Clade A to Clade B, establish that the node for the donor in Clade A and the node for the recipient in Clade B must be contemporaneous.

- Molecular Dating Analysis: In your dating software (e.g., RevBayes), set up a relaxed molecular clock model. Input both your fossil calibrations and the relative time constraints derived from HGT events. Run the MCMC analysis until convergence is achieved [18].

- Validation: Compare the results of analyses with and without the HGT constraints to assess their impact on node ages and credibility intervals.

Protocol 2: Validating an HGT Event for Use as a Constraint

Objective: To confirm that a putative HGT event is genuine and suitable for use as a relative time-order constraint.

Materials:

- Putative HGT gene sequence and homologous sequences from potential donor and recipient lineages.

- Phylogenetic analysis software (e.g., IQ-TREE, RAxML).

- Computational resources for statistical testing.

Methodology:

- Curate a High-Quality Alignment: Build a multiple sequence alignment for the gene of interest, including sequences from the putative recipient, putative donor, and many other taxa to provide context.

- Construct Gene Trees: Infer a phylogenetic tree for the gene. A true HGT will be indicated by the recipient's gene grouping with the donor's genes with strong support, rather than with its taxonomic relatives.

- Reconcile with Species Tree: Compare the gene tree to the established species tree. Use phylogenetic reconciliation methods to test if HGT is a significantly better explanation for the observed pattern than incomplete lineage sorting or gene duplication and loss [17].

- Perform Statistical Tests: Use methods like the Approximately Unbiased (AU) test to statistically reject alternative topologies that do not involve HGT [17].

- Assess Function and Context: Examine the genomic context (e.g., is it near other mobile elements?) and the function of the gene to see if it is consistent with known HGT mechanisms.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Calibration Types in Molecular Dating

| Feature | Fossil Calibrations | HGT-Derived Relative Constraints |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Information | Absolute (minimum/maximum ages) | Relative (node A is contemporaneous with node B) |

| Primary Source | Fossil record | Genomic sequence data and phylogeny |

| Best Use Case | Groups with a structured fossil record (e.g., plants, animals) | Groups with poor fossil records (e.g., microbes, fungi) |

| Main Challenge | Fossil interpretation and precise taxonomic assignment | Accurate identification of the HGT event and involved lineages |

| Combined Benefit | Provides absolute age anchors for the tree | Provides temporal correlations between nodes, improving overall time estimation [18] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Scenarios with HGT Constraints

| Scenario | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis fails to converge after adding HGT constraints | Conflicting temporal information between constraints and other priors | Re-evaluate the evidence for the HGT and check for conflicts with fossil calibrations. |

| HGT constraints have negligible effect on node ages | The fossil calibrations or clock model may be too restrictive. | Check the priors on your fossil calibrations; they may be overly confident and thus dominating the analysis. |

| Posterior age estimates are much older than expected | The HGT constraint may be incorrectly forcing deep nodes to be contemporaneous. | Verify that the recipient lineage in the HGT event is correctly identified and is not an artifact of deep gene duplication. |

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: HGT Constraint Workflow

Diagram 2: HGT Creating a Relative Constraint

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HGT Constraint Research

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Datasets | Provides the raw sequence data for phylogenomic and HGT analysis. | Initiatives like the "1000 Fungal Genomes Project" provide broad taxonomic sampling [17]. |

| Site-Heterogeneous Models (e.g., CAT) | Phylogenetic models that account for variation in amino acid composition across sites, crucial for resolving deep evolutionary relationships and avoiding artifacts that can confound HGT detection [17]. | Implemented in software like PhyloBayes. |

| Bayesian Molecular Clock Software | Software capable of integrating relative time-order constraints into the dating analysis. | RevBayes is a flexible platform that allows this [18]. |

| Phylogenetic Reconciliation Tools | Software used to compare gene trees and species trees to infer evolutionary events like HGT. | Used to systematically identify and validate HGT events [17]. |

| Statistical Test Packages (e.g., AU Test) | Provides a statistical framework for testing alternative phylogenetic hypotheses, such as the presence or absence of an HGT event. | Helps reject topologies that do not support the HGT, strengthening the evidence for the constraint [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are taphonomic controls and why are they important for calibration? Taphonomic controls involve assessing the conditions that affect fossil preservation to identify gaps and biases in the rock record. They are crucial for justifying maximum age constraints for a lineage. A strong maximum constraint can be established based on the absence of evidence for a lineage, but only when qualified by the presence of taphonomic controls provided by sister lineages and knowledge of facies biases in the rock record [20].

Q2: My divergence times have extremely wide confidence intervals. What is wrong? Overly broad confidence intervals often stem from imprecise or poorly justified calibrations. The precision of divergence time estimates is limited more by the precision of fossil calibrations than by the amount of sequence data [20]. To fix this, focus on a priori evaluation of your fossil calibrations. Ensure you are using the best possible fossil evidence by minimizing phylogenetic uncertainty and providing explicit justification for the probability densities you assign to node ages [20].

Q3: What is the difference between a "soft" and "hard" maximum bound? A hard maximum bound assigns a zero probability to any node age older than the constraint. A soft maximum, which is generally preferred, allows a small amount of probability (e.g., 2.5%) to exceed the maximum constraint. This accommodates uncertainty and is less likely to produce biased estimates if the true divergence is slightly older than the fossil evidence suggests [20].

Q4: My analysis is computationally slow with large phylogenomic datasets. Are there faster alternatives to Bayesian dating? Yes, rapid dating methods can significantly reduce computational burden. The Relative Rate Framework (RRF), implemented in RelTime, is computationally efficient and has been shown to provide node age estimates statistically equivalent to Bayesian divergence times, while being more than 100 times faster [14]. Penalized Likelihood (PL), implemented in treePL, is another fast alternative, though it can be slower than RRF and often yields time estimates with lower levels of uncertainty [14].

Q5: How can I use a fossil to calibrate a node without assigning multiple prior distributions? Incoherence from applying multiple priors to a single node can be avoided by treating the fossil observation time as data. The age of the calibration node is a deterministic node, and the fossil age is a stochastic node clamped to its observed age. This approach, used in RevBayes, calibrates the birth-death process without applying multiple prior densities to the calibrated node [21].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly broad posterior age estimates [20] | Imprecise calibration priors. | Re-evaluate fossil evidence; use justified soft maximum bounds based on taphonomic controls [20]. |

| Conflicting age estimates between calibration methods [20] | Use of inconsistent calibrations; miscalibrated priors. | Use a priori fossil evaluation over a posteriori cross-validation; ensure calibrations are accurate [20]. |

| Computationally infeasible with large dataset [14] | High computational demand of Bayesian MCMC sampling. | Use a fast dating method (e.g., RelTime) to approximate Bayesian timescales [14]. |

| Incoherent calibration priors [21] | Applying multiple prior densities to a single calibrated node. | Use fossil evidence as data to condition the tree model, as implemented in RevBayes [21]. |

| Low contrast in workflow diagrams | Insufficient color ratio between foreground and background. | Ensure a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text or UI components [22] [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Node Calibration with Taphonomic Controls

This protocol outlines the steps for justifying and implementing a node calibration in a Bayesian molecular dating analysis, incorporating taphonomic controls to establish a soft maximum bound.

1. Identify and Evaluate the Fossil Evidence

- Select a Fossil: Choose a fossil that can be reliably assigned to a lineage based on apomorphies (derived characteristics).

- Establish the Minimum Bound: The first appearance datum (FAD) of this fossil provides a hard minimum constraint for the divergence at the base of its clade. In our example, the oldest crown group bear, Ursus americanus, has a FAD of 1.84 Ma [21].

2. Establish a Justified Maximum Bound Using Taphonomic Controls

- Rationale: A soft maximum bound should be based on positive evidence for the absence of a lineage, not just a lack of evidence.

- Procedure:

- Identify the sister lineage to your clade of interest. In this case, the clade containing bears and other "dog-like" mammals (caniforms).

- Investigate the fossil record of this sister lineage. The oldest known fossil of the caniform clade provides an objective basis for a maximum constraint.

- This evidence, combined with knowledge of the rock record's suitability for preserving members of this clade (taphonomic controls), justifies setting a soft maximum constraint. For crown bears, this is set at 49.0 Ma [21].

3. Implement the Calibration in Software

- The following example uses RevBayes syntax to apply these constraints to the root node.

- For an internal node calibration, the fossil age can be treated as data offset from the node age [21]:

4. Run the Analysis and Assess Output

- Conduct the MCMC analysis to estimate the posterior distribution of divergence times.

- Critical Step: Run the analysis without the sequence data to examine the effective calibration prior. Compare this prior to the posterior to understand the influence of your molecular data [21].

- Use software like Tracer to visualize the posterior and prior distributions of node ages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material / Software | Function in Molecular Dating |

|---|---|

| BEAST / MCMCTree | Software implementing Bayesian relaxed clock models for divergence time estimation [14]. |

| RevBayes | Highly modular software for Bayesian phylogenetic inference; allows for coherent implementation of fossil calibrations by treating them as data [21]. |

| RelTime | Implements the Relative Rate Framework (RRF) for fast molecular dating, useful for large phylogenomic datasets [14]. |

| treePL | Implements Penalized Likelihood (PL) for fast molecular dating [14]. |

| Fossil Taxa Table | A file (e.g., bears_taxa.tsv) containing the first (max) and last (min) appearance dates for all species, both extant and extinct, used for calibration [21]. |

| Tracer | Software for analyzing the output of MCMC analyses (e.g., from BEAST, RevBayes), allowing you to assess convergence and summarize posterior distributions of parameters like node ages [21]. |

| Justified Soft Maximum | A calibration prior based on taphonomic controls and the fossil record of sister lineages, which provides a more accurate and precise upper bound on node age than an arbitrary value [20]. |

Workflow: Calibration with Taphonomic Controls

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for developing and implementing a calibrated molecular dating analysis.

Accounting for Compositional Heterogeneity in Amino Acid Sequence Evolution

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Phylogenetic Resolution or Unsupported Topologies

Problem: Analysis results in a phylogenetic tree with poor resolution, low bootstrap support, or suspected long-branch attraction artifacts.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Substitution Saturation | Calculate saturation statistics; inspect if distant taxa have similar amino acid frequencies due to homoplasy [24]. | Use complex models (e.g., CAT); consider recoding schemes with more than 6 states (e.g., 9, 12, 15, 18) [24]. |

| Violation of Stationarity | Use RCFV/nRCFV metrics to quantify compositional heterogeneity across taxa before analysis [25]. | Remove compositionally heterogeneous taxa; use site-heterogeneous models; apply amino acid recoding [25]. |

| Inadequate Substitution Model | Perform model selection tests (e.g., ProtTest); check model adequacy. | Select models that account for site-specific rate variation (e.g., Gamma + I) and composition (e.g., PMB) [26]. |

Issues with Molecular Dating Calibration

Problem: Divergence time estimates are unrealistic, have extremely wide confidence intervals, or are strongly sensitive to prior choices.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Fossil Calibrations | Review fossil evidence for internal nodes; check if calibrations are based on robust stratigraphic data. | Use node-dating with carefully vetted fossil calibrations; consider the fossilized birth-death process [26]. |

| Unsuitable Clock Model | Perform clock likelihood tests; check if rate variation across lineages is significant. | Use autocorrelated clock models (e.g., CIR process) for biologically realistic rate variation [26]. |

| Compositional Heterogeneity Bias | Assess if calibrating nodes involve taxa with high tsRCFV values [25]. | Re-run dating analysis after excluding compositionally biased taxa or using recoded data [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is compositional heterogeneity and why is it a problem for molecular dating?

Compositional heterogeneity occurs when the proportions of amino acids are not broadly similar across the taxa in a dataset. This violates the stationarity assumption of most substitution models used in phylogenetics, potentially leading to phylogenetic artefacts, including erroneous estimation of edge lengths and topologies, which in turn can severely bias molecular date estimates [25].

Q2: How can I measure compositional heterogeneity in my amino acid dataset?

The Relative Composition Frequency Variability (RCFV) metric and its improved version, nRCFV, are designed specifically for this purpose. RCFV quantifies the deviation of each taxon's amino acid frequency from the dataset average. The newer nRCFV metric is recommended as it is normalized to be independent of dataset size, number of taxa, and sequence length, providing a unbiased quantification [25].

Q3: Is six-state amino acid recoding an effective strategy to mitigate the effects of compositional heterogeneity?

Simulation studies suggest that six-state recoding is often not the most effective strategy. While it can buffer against compositional heterogeneity, the significant loss of phylogenetic information often outweighs the benefits, especially under conditions of high substitution saturation. Recoding schemes with a higher number of states (e.g., 9, 12, 15, or 18) have been shown to consistently outperform six-state recoding [24].

Q4: What is an autocorrelated clock model and why might it be preferred in molecular dating?

An autocorrelated clock model posits that the rate of molecular evolution along a lineage is correlated with the rate in its immediate ancestor. This is often considered more biologically realistic than uncorrelated models, as it reflects the heritability of traits like generation time and metabolic rate that influence substitution rates. Using a biologically plausible clock model is crucial for obtaining accurate divergence times [26].

Q5: Besides taxon removal, what are other approaches to handle compositional heterogeneity?

- Amino Acid Recoding: Grouping amino acids into a smaller number of categories based on chemical properties or substitution patterns to reduce compositional signal [24].

- Site-Heterogeneous Models: Using complex substitution models (e.g., CAT) that allow different sites in the alignment to have distinct evolutionary processes [25].

- Coevolutionary Analysis: Using methods like Direct Coupling Analysis (DCA) to identify and account for networks of interacting residues that evolve in a correlated manner [27].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Quantifying Compositional Heterogeneity with nRCFV

Purpose: To objectively measure compositional heterogeneity in a phylogenetic dataset prior to tree reconstruction.

Materials:

- Amino acid sequence alignment (FASTA format)

- Software:

RCFV_Reader(Available at: https://github.com/JFFleming/RCFV_Reader)

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Prepare a multiple sequence alignment of your amino acid data.

- Software Execution: Run the

RCFV_Readertool on your alignment. - Data Extraction:

- Extract the total nRCFV value for the entire dataset. A higher value indicates greater overall heterogeneity.

- Extract taxon-specific nRCFV (ntsRCFV) values to identify outlier taxa with highly divergent compositions.

- Extract character-specific nRCFV (ncsRCFV) values to identify which amino acids are contributing most to the heterogeneity.

- Interpretation: Use the results to make informed decisions about data filtering, model selection, or the application of recoding strategies. Taxa with high ntsRCFV may be candidates for removal, while skewed ncsRCFV may suggest recoding is appropriate [25].

Protocol: Evaluating Amino Acid Recoding Strategies

Purpose: To test if amino acid recoding improves phylogenetic signal by reducing compositional heterogeneity.

Materials:

- Amino acid sequence alignment

- Phylogenetic software (e.g., IQ-TREE, PhyloBayes)

- Scripts or functions for recoding (e.g., in BaCoCa or custom scripts)

Methodology:

- Baseline Analysis: Perform a phylogenetic analysis (e.g., Maximum Likelihood) on the non-recoded data. Record bootstrap support values and tree topology.

- Data Recoding: Recode your amino acid alignment into different state schemes (e.g., 6-state, 9-state, 12-state).

- Comparative Analysis: Re-run the phylogenetic analysis on each recoded dataset using the same inference parameters.

- Evaluation:

- Compare topologies and support values (e.g., bootstrap) across analyses.

- Use model selection criteria to assess fit.

- Prefer the recoding strategy that yields higher nodal support and is justified by tests of compositional heterogeneity [24].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Comparison of Compositional Heterogeneity Metrics

The following table summarizes the key metrics used to assess compositional heterogeneity.

| Metric | Formula | Purpose | Biases/Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCFV | $$RCFV=\sum{i=1}^{n}\sum{j=1}^{j=m}\frac{\left | {\mu }{ij}-\overline{{\mu }{j}}\right | }{n}$$ [25] | Quantifies overall compositional variation in a dataset. | Biased by sequence length, number of taxa, and character states [25]. |

| nRCFV | Modified RCFV with normalization constants. | A dataset-size-independent metric for compositional heterogeneity. | Allows direct comparison between datasets of different sizes [25]. | ||

| tsRCFV / ntsRCFV | $$tsRCFV=\sum_{j=1}^{j=m}\frac{\left | {\mu }{ij}-\overline{{\mu }{j}}\right | }{n}$$ [25] | Identifies taxa (or monophyletic groups) with atypical amino acid compositions. | Critical for deciding on taxon exclusion or model application [25]. |

| csRCFV / ncsRCFV | $$csRCFV=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\frac{\left | {\mu }{ij}-\overline{{\mu }{j}}\right | }{n}$$ [25] | Identifies amino acids that are over- or under-represented across the dataset. | Guides decisions on amino acid recoding strategies [25]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application in Analysis |

|---|---|

| RCFV_Reader Software | Calculates RCFV and the improved nRCFV metrics from a nucleotide or amino acid alignment to quantify compositional heterogeneity [25]. |

| BaCoCa Tool | A comprehensive tool that implements the original RCFV calculation and other tests for compositional heterogeneity and saturation [25]. |

| PhyloBayes Software | Implements site-heterogeneous mixture models (e.g., CAT) and complex clock models that can better handle compositionally heterogeneous data [26]. |

| Dayhoff-6 Recoding Groups | The original 6-state recoding scheme (AGPST, DENQ, HKR, ILMV, FWY, C) that groups chemically similar amino acids [24]. |

Visualization Diagrams

Workflow for Heterogeneity Assessment

Decision Workflow for Heterogeneity Issues

Data Types in Molecular Dating

Factors Influencing Molecular Dating

Machine Learning for Branch Support and Multiple Sequence Alignment Evaluation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key considerations when choosing a molecular dating method for phylogenomic data? When selecting a molecular dating method, consider computational demand, treatment of rate variation, and calibration use. Bayesian methods (e.g., BEAST, MCMCTree) are highly parameterized and computationally intensive, making them challenging for large datasets. Rapid methods like the Relative Rate Framework (RRF), implemented in RelTime, and Penalized Likelihood (PL), implemented in treePL, offer alternatives. RRF does not assume a global clock and accommodates rate variation between sister lineages without a penalty function, while PL uses a smoothing parameter to control global rate autocorrelation. For large phylogenomic datasets, RRF can be more than 100 times faster than treePL and provides node age estimates statistically equivalent to Bayesian methods, offering a practical balance between accuracy and speed [14].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the reliability of branch support in my phylogenetic trees? Traditional bootstrap support values based solely on sequence data can be enhanced by integrating structural information from proteins. The multistrap method combines sequence-based bootstrapping with structural metrics derived from homologous intra-molecular distances (IMD). Structural metrics like Template Modeling Score (TM-Score) and IMD exhibit lower saturation than sequence-based Hamming distances, meaning they retain phylogenetic signal even for distantly related sequences. Combining sequence and structure bootstrap support values significantly improves the discrimination between correct and incorrect branches, leading to more reliable phylogenetic inferences [28].

FAQ 3: Which multiple sequence alignment (MSA) tool should I use for my dataset? The choice of MSA tool depends on your dataset's characteristics, but accuracy evaluations consistently rank ProbCons as the top performer for overall alignment quality. Other high-performing tools include SATé and MAFFT(L-INS-i). SATé offers a significant speed advantage, being over 500% faster than ProbCons. Alignment quality is highly influenced by the number of deletions and insertions in the sequences, with sequence length and indel size having a weaker effect. For a balance of accuracy and speed, SATé and MAFFT are excellent choices [29].

FAQ 4: How can machine learning accelerate maximum likelihood tree searches? Machine learning (ML) can guide heuristic tree searches by predicting which tree rearrangements are most likely to increase the likelihood score, avoiding costly likelihood calculations for all possible neighbors. A trained random forest regression model can use features from the current tree and proposed Subtree Pruning and Regrafting (SPR) moves to rank neighbors. This allows the algorithm to evaluate only a promising subset of the tree space. This approach can successfully identify the optimal move within the top 10% of predictions in a majority of cases, substantially accelerating tree inference without sacrificing accuracy [30].

FAQ 5: What is the impact of an incorrect tree prior in Bayesian molecular dating with mixed samples? Using a single tree prior for phylogenies containing both intra- and interspecies samples (a mix of population-level and species-level divergences) can bias time estimates. Bayesian methods typically use a tree prior designed for either speciation processes (e.g., Yule, Birth-Death) or population processes (e.g., coalescent). Applying a speciation prior to population divergences incorrectly treats them as speciation events, while using a coalescent prior for deep interspecies nodes can also introduce bias. It is critical to evaluate the fit of different tree priors to your specific data mix to ensure accurate divergence time estimation [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Long computational times for Bayesian molecular dating with large phylogenomic datasets.

- Issue: Bayesian MCMC analyses are prohibitively slow with large numbers of sequences.

- Solution: Use rapid dating methods to approximate Bayesian inference.

- Protocol: Employ the Relative Rate Framework (RRF) in MEGA X's RelTime.

- Estimate a phylogeny from your alignment (e.g., using Maximum Likelihood in MEGA X or IQ-TREE).

- In MEGA X, use the

Compute Timetreefunction with the RelTime method. - Apply the same calibration constraints (e.g., uniform, lognormal) used in your Bayesian setup. RelTime supports calibration densities.

- Expected Outcome: You will obtain a timetree with divergence times and confidence intervals in a fraction of the time required for a Bayesian analysis, with estimates often statistically equivalent to Bayesian posteriors [14].

- Protocol: Employ the Relative Rate Framework (RRF) in MEGA X's RelTime.

Problem 2: Low branch support values in a phylogeny inferred from sequence data.

- Issue: Traditional bootstrap values are low, reducing confidence in inferred evolutionary relationships.