Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) has evolved from a theoretical concept into a powerful experimental tool for probing molecular evolution and engineering proteins with enhanced properties.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) has evolved from a theoretical concept into a powerful experimental tool for probing molecular evolution and engineering proteins with enhanced properties. This article provides a comprehensive overview of ASR techniques, from foundational principles and methodological workflows to advanced applications in structural biology and drug discovery. We detail common troubleshooting strategies for addressing methodological uncertainties and present a comparative analysis of ASR against other protein engineering approaches. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current literature to highlight how ASR is providing deeper mechanistic insights into protein function and creating new opportunities for developing therapeutic and industrial biocatalysts.

The Foundations of Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Principles and Evolutionary Insights

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) is a powerful technique in the field of molecular evolution that enables scientists to reconstruct the sequences of ancient genes and proteins that existed in extinct organisms [1]. The foundational concept was first suggested in 1963 by Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl, who proposed that historical molecular sequences could be inferred from modern descendants [1]. This approach allows researchers to move beyond comparative studies of extant sequences and directly test hypotheses about evolutionary history through experimental analysis of resurrected biomolecules.

The core principle of ASR rests on the observation that closely related species share similar DNA sequences. When modern species differ at specific sequence positions, evolutionary relationships and outgroup comparisons allow researchers to infer which states were most likely present in their common ancestors [1]. This methodology has evolved from early pioneering work in the 1980s and 1990s, led by researchers like Steven A. Benner, into a sophisticated computational and experimental discipline that can reconstruct genes dating back billions of years [1].

ASR serves as a bridge between evolutionary biology and experimental molecular biology, creating a "functional synthesis" that allows researchers to understand how gene sequences, protein structures, and biological functions have diverged over evolutionary timescales [2]. This approach has revealed that ancestral proteins often exhibit properties such as increased thermostability, catalytic activity, and catalytic promiscuity compared to their modern counterparts [1].

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Methodology

Core Principles of Sequence Reconstruction

The theoretical foundation of ASR relies on established evolutionary principles and statistical models. The fundamental assumption is that modern sequences share common ancestry, and their differences result from evolutionary divergence over time. When two species differ at a specific nucleotide position (e.g., humans have 'A' while chimpanzees have 'G'), researchers can infer the ancestral state by examining outgroup sequences (e.g., gorillas and orangutans) [1]. If the outgroups share 'A' with humans, this suggests the ancestor likely had 'A', with a mutation to 'G' occurring in the chimpanzee lineage.

ASR addresses the "multiple hit problem" in molecular evolution – the fact that comparison of present-day sequences alone underestimates the actual number of substitutions that have occurred because multiple changes may affect the same site throughout evolutionary history [2]. Advanced statistical methods are required to account for these hidden changes and produce accurate ancestral reconstructions.

Computational Reconstruction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of ASR Computational Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) | Identifies the sequence that statistically maximizes the probability of observing the extant sequences given an evolutionary model [1] | Most widely used; incorporates complex evolutionary models; provides probabilistic confidence measures [1] | Dependent on evolutionary model assumptions; computationally intensive |

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) | Selects the ancestral sequence requiring the fewest evolutionary changes [2] [1] | Computationally efficient; conceptually simple | Often oversimplifies evolutionary processes; less accurate for deep reconstructions [1] |

| Bayesian Methods | Generates a posterior distribution of possible ancestral sequences incorporating prior knowledge [1] | Quantifies uncertainty comprehensively; incorporates prior information | Computationally demanding; produces potentially ambiguous sequences [1] |

The Maximum Likelihood method, currently the most widely employed approach, works by generating a sequence where the residue at each position is predicted to be the most likely to occupy that position based on a scoring matrix calculated from extant sequences [1]. This method incorporates sophisticated evolutionary models that account for variation in substitution rates across sites and lineages.

It is crucial to recognize that ASR does not typically claim to recreate the exact sequence of the ancient protein/DNA, but rather a sequence that is likely to be similar and, importantly, shares the functional properties of the ancestral molecule [1]. This aligns with the "neutral network" model of protein evolution, which proposes that at evolutionary junctions, populations contained genotypically different but phenotypically similar protein sequences [1].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

Comprehensive ASR Pipeline

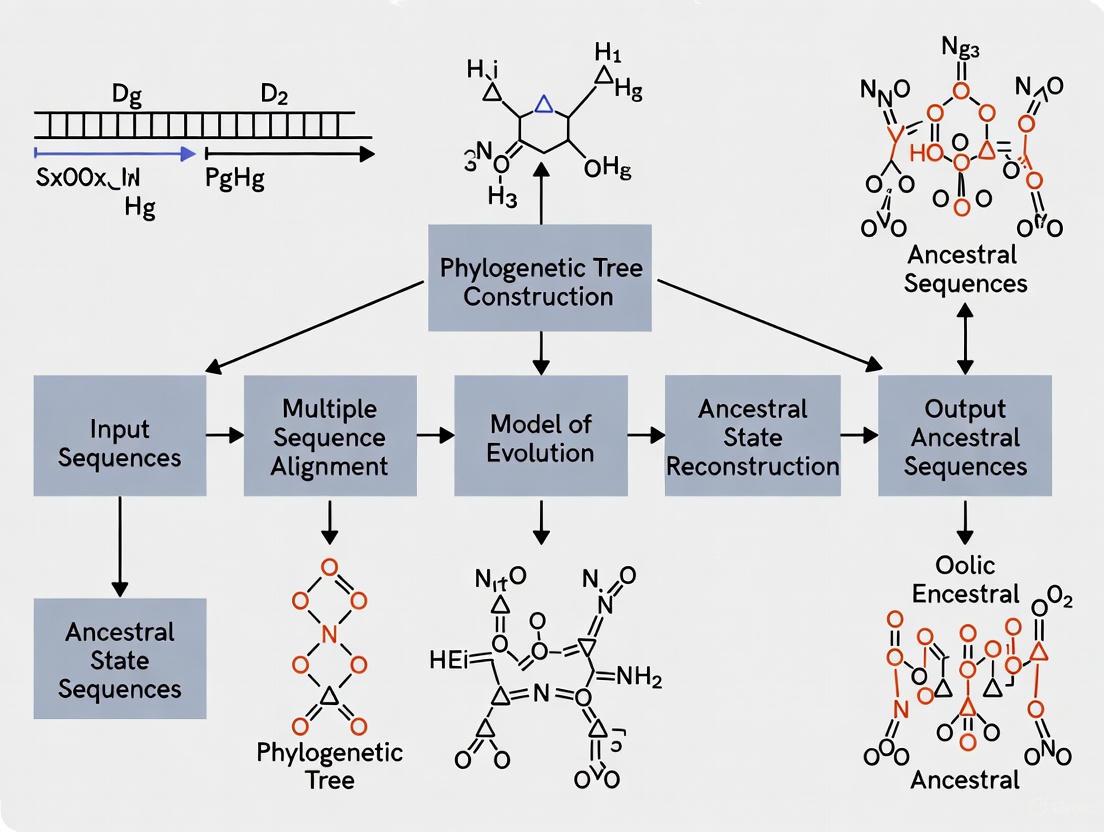

The following diagram illustrates the complete ASR workflow from sequence collection to functional characterization:

Diagram 1: Complete ASR Experimental Workflow

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Sequence Collection and Multiple Sequence Alignment

Collect homologous sequences from diverse but related extant species. The selection should represent an appropriate evolutionary spread for the phylogenetic depth of interest. Create a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) using tools such as MUSCLE, MAFFT, or Clustal Omega to identify conserved and variable regions [2] [1]. The quality of the MSA critically impacts all downstream analyses, so careful refinement is essential.

Step 2: Phylogenetic Tree Construction

Build a phylogenetic tree from the aligned sequences using maximum likelihood, Bayesian inference, or other robust methods. The tree topology and branch lengths will directly influence the ancestral state reconstruction, making this a critical step [1]. Use appropriate model testing to identify the best-fitting substitution model for your dataset.

Step 3: Ancestral Sequence Inference

Apply computational reconstruction methods (Table 1) to infer ancestral sequences at the nodes of interest in the phylogenetic tree. For maximum likelihood approaches, software such as PAML, HyPhy, or GARLI can be used [2]. It is considered best practice to generate several alternative reconstructions for each node to account for uncertainty and ambiguity in the inference process [1].

Step 4: Gene Synthesis and Molecular Cloning

Following ancestral sequence inference, the candidate sequences are synthesized as DNA constructs. Unlike working with extant genes, researchers cannot simply amplify ancestral genes from living organisms, making synthetic gene synthesis an essential step [1]. These synthetic genes are then cloned into appropriate expression vectors.

Step 5: Protein Expression and Purification

Express the reconstructed ancestral proteins in heterologous systems such as E. coli, yeast, or mammalian cell lines [1]. After expression, purify the proteins using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification) followed by additional purification steps such as size-exclusion or ion-exchange chromatography to achieve homogeneity.

Step 6: Biochemical and Functional Characterization

Characterize the biophysical and functional properties of the resurrected proteins. This typically includes:

- Thermostability Analysis: Measuring melting temperature (Tm) and thermodynamic stability using differential scanning calorimetry or circular dichroism [1]

- Catalytic Activity: Determining enzyme kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) for putative substrates [1]

- Structural Analysis: If possible, determine three-dimensional structure using X-ray crystallography or NMR to complement functional studies

- Ligand Binding: For receptors, measure affinity for relevant ligands [1]

Controls and Validation

To ensure the reliability of ASR findings, incorporate appropriate controls throughout the experimental process:

- Express and characterize modern descendant proteins using identical methods for direct comparison

- Generate and test alternative reconstructions for ambiguous sites to ensure conclusions are robust to inference uncertainty [1]

- For studies observing "ancestral superiority" (e.g., enhanced thermostability), express consensus sequences of modern proteins to determine if observed effects stem from ancestral inference versus simply being a consensus effect [1]

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for ASR Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Homologous Sequence Datasets | Source material for phylogenetic reconstruction and ancestral inference [1] | Should include evolutionarily diverse but related sequences; public databases (GenBank, UniProt) are primary sources |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Software | Creates aligned sequence datasets for phylogenetic analysis [2] | Options: MUSCLE, MAFFT, Clustal Omega; alignment quality critically impacts reconstruction accuracy |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Builds evolutionary trees and reconstructs ancestral sequences [1] | Maximum Likelihood: PAML, HyPhy, RAxML; Bayesian: MrBayes; selection of appropriate evolutionary model is crucial |

| Synthetic DNA Constructs | Physical instantiation of inferred ancestral sequences [1] | Custom gene synthesis services; codon optimization for expression system is recommended |

| Heterologous Expression System | Produces protein from synthetic ancestral genes [1] | Common systems: E. coli, yeast, insect, or mammalian cell lines; selection depends on protein properties and requirements |

| Protein Purification Materials | Isifies ancestral protein for functional characterization [1] | Affinity chromatography resins (Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins), size exclusion, ion exchange columns |

| Biophysical Assay Reagents | Characterizes stability and structural properties [1] | Circular dichroism spectroscopy, differential scanning calorimetry, fluorescence dyes for thermal shift assays |

| Activity Assay Components | Measures enzymatic or receptor function [1] | Substrates, cofactors, specific inhibitors; depends on protein function being studied |

Applications and Case Studies in Evolutionary Biochemistry

Notable Examples of Resurrected Proteins

Table 3: Significant ASR Case Studies and Findings

| Protein/System | Evolutionary Time Scale | Key Findings | Research Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Receptors | ~500 million years [1] | Revealed evolutionary pathway of ligand specificity in steroid receptors [1] | Thornton Lab [1] |

| Thioredoxin Enzymes | Up to 4 billion years [1] | Ancestral enzymes showed significantly elevated thermal and acidic stability while maintaining similar chemical activity [1] | Multiple Groups [1] |

| V-ATPase Subunits | ~800 million years [1] | Investigation of ancient enzyme complex assembly and function in yeast lineages | Stevens/Thornton Labs [1] |

| Ribonuclease H1 (E. coli) | Variable evolutionary depths [1] | Detailed studies on evolutionary biophysical history and stability mechanisms | Marqusee Lab [1] |

| Alcohol Dehydrogenases (Adhs) | ~85 million years [1] | Revealed emergence of subfunctionalized Adhs for ethanol metabolism correlated with fleshy fruit emergence in Cambrian Period [1] | Multiple Groups [1] |

| Visual Pigments | Vertebrate evolution scale [1] | Traced evolutionary adaptations in light absorption properties related to visual ecology | Multiple Groups [1] |

| RuBisCO (Solanaceae) | Plant family evolutionary scale [1] | Studies of photosynthetic enzyme evolution in plant family contexts | Multiple Groups [1] |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While ASR provides powerful insights into molecular evolution, researchers must consider several methodological aspects:

Phylogenetic Uncertainty: The accuracy of ancestral reconstruction depends heavily on the correct phylogenetic tree topology and appropriate evolutionary models [1]. Sensitivity analyses using alternative tree topologies should be conducted to test the robustness of conclusions.

Evolutionary Model Selection: The statistical models used for reconstruction are based on modern sequence data, yet amino acid frequencies and substitution patterns in ancient biological environments may have differed [1]. While studies suggest that derived biophysical properties are generally robust to this concern, it remains an important consideration [1].

Experimental Validation: The ultimate validation of ASR reliability often comes from comparing several alternate reconstructions of the same node and confirming similar biophysical properties emerge across them [1]. This approach leverages the fundamental principle that individual amino acid substitutions typically don't cause drastic biophysical property changes in proteins [1].

Temporal Framing: The "age" of reconstructed sequences is typically determined using molecular clock models calibrated with geological timepoints [1]. These dating approaches have substantial error margins and should be considered approximate temporal frameworks rather than precise dates [1]. Many researchers instead use the number of substitutions between ancestral and modern sequences as a more reliable evolutionary distance metric [1].

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction has evolved from a theoretical concept to an indispensable practical tool in evolutionary biochemistry and molecular biology. By combining computational phylogenetics with experimental molecular biology, ASR enables researchers to directly test hypotheses about evolutionary history and mechanisms. The methodology continues to develop with improvements in sequencing technologies, computational algorithms, and synthetic biology capabilities.

When rigorously applied with appropriate controls and validation, ASR provides unique insights into the evolutionary processes that have shaped modern biological systems. The technique has revealed fundamental principles about protein evolution, including patterns of thermostability, catalytic innovation, and functional diversification. As the field advances, ASR promises to continue expanding our understanding of life's deep evolutionary history.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) represents a powerful convergence of evolutionary biology and computational science, enabling researchers to infer the genetic sequences of long-extinct organisms and thereby illuminate the deep history of molecular evolution. This field has transformed from a theoretical concept into an indispensable experimental toolkit, with modern applications spanning protein engineering, drug development, and fundamental research into life's origins. The journey of ASR began with a revolutionary insight from Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling, who first proposed that comparing sequences from extant species could allow scientists to deduce ancestral molecular forms [3] [1]. Today, this foundational principle underpins sophisticated computational approaches that resurrect ancient proteins for both theoretical inquiry and practical application. This technical guide examines the methodological evolution of ASR, from its earliest conceptual foundations to contemporary computational frameworks that integrate generative models and address persistent challenges like indel reconstruction.

Historical Foundations and Key Theoretical Advances

The conceptual architecture of ASR was established in 1963 when Zuckerkandl and Pauling published their seminal hypothesis suggesting that comparing homologous sequences across species could reveal their evolutionary history [3] [1]. Their work introduced the crucial concept that contemporary genes evolved from common ancestral genes through measurable mutational processes. This theoretical breakthrough created the foundation for a new field—paleogenetics—though the computational tools necessary to implement their vision would require decades to develop.

Table 1: Foundational Methodological Developments in ASR

| Time Period | Methodological Innovation | Key Contributors | Impact on ASR Field |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Conceptual framework for inferring ancestral sequences | Zuckerkandl & Pauling | Established theoretical basis for molecular evolution studies [3] |

| 1971 | Parsimony method for ancestral reconstruction | Fitch | First algorithmic implementation for ASR [3] |

| 1981 | Maximum likelihood introduced for phylogenetics | Felsenstein | Statistical framework for evolutionary inference [3] |

| 1995-1996 | Maximum likelihood models for protein ASR | Yang et al.; Koshi & Goldstein | First robust probabilistic methods for ancestral protein inference [3] |

| 2000 | Joint reconstruction across nodes | Pupko et al. | Enhanced accuracy by considering complete evolutionary paths [3] |

| 2006 | Bayesian sampling approaches | Williams et al. | Incorporated uncertainty in ancestral predictions [3] |

| 2020s | Autoregressive generative models | Multiple groups | Account for epistasis and context-dependent evolution [4] |

Early methodological development focused on establishing robust computational frameworks for reconstructing ancestral states. The maximum parsimony approach, which minimizes the number of evolutionary changes required to explain observed sequences, dominated early ASR efforts due to its conceptual simplicity and computational tractability [3] [1]. However, the field underwent a significant transformation with the introduction of probabilistic methods, particularly maximum likelihood estimation, which incorporated explicit models of sequence evolution and branch lengths to assess the relative probabilities of potential ancestral states [3]. The equation below illustrates the fundamental calculation of the likelihood of an ancestral sequence (Ar) given modern sequences (Ai'), an evolutionary model (M), and a phylogenetic tree (T):

$$P(Ar|Ai',M,T) = \frac{P(Ai'|Ar,M,T)P(Ar)}{P(Ai'|M,T)}$$ [3]

This statistical framework enabled more accurate characterizations of ancient sequences by accounting for the stochastic nature of molecular evolution, setting the stage for ASR to become an empirically rigorous discipline.

Evolution of Computational Methodologies

Sequence Alignment: The Foundational Step

Accurate ASR depends critically on proper identification of homologous positions across sequences through multiple sequence alignment (MSA). Early alignment algorithms employed dynamic programming approaches like the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm for global alignment and Smith-Waterman for local alignment, which guarantee optimal solutions but suffer from computational complexity that limits their application to large datasets [5] [6]. To address these limitations, heuristic methods such as FASTA and BLAST incorporated anchor-based strategies to identify homologous segments quickly, significantly accelerating the alignment process while maintaining acceptable accuracy [5].

Modern MSA tools typically employ progressive alignment strategies that build alignments according to a guide tree representing estimated evolutionary relationships. Popular implementations include Clustal Omega, MUSCLE, and MAFFT, which balance accuracy with computational efficiency through techniques like iterative refinement and fast Fourier transform-based homology detection [5] [6]. For specialized applications involving sequences with large-scale rearrangements, tools like Mauve provide advanced capabilities for whole-genome alignment [6].

Table 2: Multiple Sequence Alignment Algorithms and Applications

| Algorithm | Alignment Strategy | Optimal Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geneious Aligner | Progressive | Small datasets (<50 sequences, <1kb length) [6] | Limited scalability |

| MUSCLE | Iterative | Medium datasets (up to 1,000 sequences) [6] | Poor performance with terminal extensions |

| Clustal Omega | Progressive | Large datasets (2,000+ sequences) with terminal extensions [6] | Struggles with large internal indels |

| MAFFT | Progressive-Iterative | Very large datasets (up to 30,000 sequences) with long gaps [6] | Computationally intensive for largest datasets |

| Mauve | Progressive | Sequences with large-scale rearrangements and inversions [6] | Specialized for genomic applications |

Phylogenetic Inference: Reconstructing Evolutionary Relationships

Phylogenetic tree construction provides the evolutionary framework essential for ASR, with methods broadly categorized as distance-based or character-based approaches [7]. Distance-based methods such as Neighbor-Joining (NJ) operate by first calculating a matrix of evolutionary distances between sequences, then applying clustering algorithms to infer tree topology [7] [8]. While computationally efficient and suitable for large datasets, these approaches necessarily discard some evolutionary information during the distance calculation process [7].

Character-based methods offer a more nuanced approach by evaluating individual sequence positions during tree inference. Maximum Parsimony (MP) seeks the tree topology that requires the fewest evolutionary changes, operating on the principle of Occam's razor [7] [8]. Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods identify the tree that maximizes the probability of observing the extant sequences under a specific evolutionary model, making them statistically robust for diverse evolutionary questions [7]. Bayesian Inference extends the likelihood framework to incorporate prior knowledge and quantify uncertainty through posterior probabilities, typically using Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling to explore tree space [7].

Diagram 1: Phylogenetic Tree Construction Workflow (77 characters)

Ancestral State Reconstruction: Computational Core

The computational core of ASR employs either marginal or joint reconstruction approaches to infer ancestral sequences. Marginal reconstruction calculates the probability of each ancestral state at individual nodes independently, while joint reconstruction simultaneously considers all nodes to find the most probable set of ancestral sequences across the entire tree [3]. Although joint reconstruction offers theoretical advantages by accounting for interactions between nodes, marginal reconstruction remains widely used due to its computational efficiency and generally comparable results [3].

Recent methodological innovations address longstanding limitations in ASR, particularly the challenge of epistasis—the context-dependence of mutational effects. Traditional models assume sequence positions evolve independently, an oversimplification that fails to capture the complex interdependencies within biomolecular structures. Novel autoregressive generative models now incorporate epistatic effects by learning evolutionary constraints from large sequence families, resulting in more accurate ancestral reconstructions that better reflect structural and functional realities [4]. These approaches demonstrate superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods in both simulation studies and experimental validation [4].

Another active frontier involves improving the handling of insertions and deletions (indels) in ancestral reconstruction. The Deletion-Only Parsimony Problem (DPP) represents a significant theoretical advance, providing polynomial-time algorithms for identifying optimal reconstructions when only deletion events are considered [9]. While this addresses just one aspect of indel evolution, it establishes crucial mathematical foundations for more comprehensive solutions and offers practical approaches for representing uncertainty in ancestral reconstructions through partial order graphs [9].

Experimental Validation and Applications

Early Experimental Milestones

The transition of ASR from computational exercise to experimental discipline began with partial reconstructions that replaced specific amino acid positions in modern proteins with inferred ancestral residues [3]. Malcolm et al. (1990) pioneered this approach by resurrecting three ancestral positions in lysozyme, enabling dissection of potential evolutionary pathways during functional divergence [3]. The first full-length ancestral protein resurrection came five years later with the reconstruction of 13 ribonucleases from artiodactyl evolution, marking a critical technical milestone that demonstrated the feasibility of comprehensive ASR [3].

A transformative period for experimental ASR began in the early 2000s with three landmark studies that expanded the temporal and conceptual boundaries of the field. Chang et al. (2002) resurrected ancestral rhodopsin proteins from archosaurs, including dinosaurs, inferring their visual capabilities in dim light environments [3]. Gaucher et al. (2003) reconstructed ancestral elongation factors to infer the environmental temperature of the last bacterial common ancestor billions of years in the past [3]. Thornton et al. (2003) resurrected steroid receptor proteins, demonstrating that early receptors likely exhibited estrogen specificity [3]. This "trifecta of studies" established ASR as a powerful approach for addressing diverse evolutionary questions across deep time scales.

Contemporary Applications in Structural Biology and Biotechnology

Recent advances have demonstrated ASR's utility for facilitating structural analysis of challenging protein complexes. In a 2025 study of modular polyketide synthases (PKSs)—large multi-domain enzymes critical for antibiotic biosynthesis—researchers replaced a native acyltransferase domain with an ancestral reconstruction (AncAT) to create a chimeric KSQAncAT didomain [10]. This engineered construct maintained native enzymatic function while exhibiting enhanced properties for structural analysis, enabling determination of high-resolution crystal structures that had proven elusive with the wild-type protein [10]. This innovative application illustrates how ASR can serve as a protein engineering tool to improve crystallization success and enable cryo-EM analysis of dynamic molecular machines.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials in ASR

| Research Reagent | Function in ASR | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ancestral AT (AncAT) domain | Enhanced stability and solubility for structural studies | Crystallography of polyketide synthase modules [10] |

| Pantetheinamide crosslinking probe | Covalently links interacting domains for structural stabilization | Cryo-EM analysis of KSQ-ACP complexes [10] |

| Fragment antigen-binding (Fab) domains | Stabilize conformational states for single-particle analysis | Cryo-EM of dynamic PKS modules [10] |

| Bayesian phylogenetic models | Incorporate uncertainty in ancestral sequence inference | Probabilistic reconstruction of indel events [9] |

| Autoregressive generative models | Account for epistatic interactions in sequence evolution | Improved accuracy in ancestral protein reconstruction [4] |

The biotechnology and therapeutic applications of ASR continue to expand as methodological improvements enhance reconstruction accuracy. Resurrected ancestral proteins often exhibit exceptional thermostability and catalytic promiscuity compared to their modern counterparts, properties valuable for industrial enzyme applications [1]. In biomedical research, ASR has contributed to vaccine development through reconstruction of ancestral immunogens and advanced protein engineering through revealing evolutionary trajectories of functional attributes [9]. The table below summarizes key properties of resurrected ancestral proteins across diverse studies.

Table 4: Properties of Resurrected Ancestral Proteins

| Protein Family | Estimated Age (Million Years) | Key Experimental Findings | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribonucleases [3] | 40 | Functional divergence during artiodactyl evolution | Enzyme evolution studies |

| Rhodopsins [3] | 240-400 | Dim-light adaptation in archosaurs | Sensory biology evolution |

| - | - | - | - |

| Elongation Factors [3] | 2,500-4,000 | Inference of ancient Earth temperatures | Paleoclimate reconstruction |

| Steroid Receptors [3] [1] | ~500 | Estrogen specificity in earliest receptors | Hormone signaling evolution |

| Thioredoxins [1] | ~4,000 | Enhanced thermostability with modern-like activity | Protein engineering templates |

| Polyketide Synthases [10] | Not specified | Improved crystallization and structural analysis | Enzyme mechanism studies |

Technical Protocols and Implementation Frameworks

Standard ASR Workflow Protocol

A robust ASR implementation follows a systematic workflow encompassing sequence collection, alignment, phylogenetic analysis, ancestral reconstruction, and experimental validation. The protocol below outlines key considerations and methodological options at each stage:

Sequence Dataset Assembly

Multiple Sequence Alignment

- Select alignment algorithm based on dataset size and sequence characteristics

- For large datasets (>1,000 sequences), consider MAFFT or Clustal Omega [6]

- For sequences with rearrangements, use specialized aligners like Mauve [6]

- Trim unreliably aligned regions while preserving phylogenetic signal [7]

Phylogenetic Tree Construction

- Select evolutionary model using model-testing tools (e.g., ProtTest for proteins)

- For preliminary analysis, use Neighbor-Joining for rapid tree estimation [7]

- For publication-quality trees, implement Maximum Likelihood or Bayesian methods [7]

- Assess node support with bootstrap resampling or posterior probabilities [7]

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction

Sequence Synthesis and Validation

- Codon-optimize ancestral sequences for expression system

- Synthesize genes commercially or via assembly PCR

- Express and purify recombinant protein for biochemical characterization

- Validate structural integrity and functional properties

Advanced Computational Framework

Contemporary ASR implementations increasingly leverage probabilistic programming frameworks to quantify uncertainty and incorporate prior knowledge. The Bayesian hierarchical model structure below represents a state-of-the-art approach for integrating multiple sources of evolutionary information:

Diagram 2: Bayesian ASR Framework (63 characters)

This Bayesian framework enables researchers to quantify uncertainty in ancestral reconstructions through posterior distributions, providing not just point estimates of ancient sequences but confidence assessments—particularly valuable when considering ancestral proteins for engineering applications [3] [4]. Modern implementations often incorporate Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling to approximate these posterior distributions, with convergence diagnostics ensuring adequate exploration of parameter space [7].

Future Directions and Methodological Frontiers

The accelerating evolution of ASR methodologies continues to expand both theoretical and practical applications. Several promising frontiers merit particular attention:

Generative Modeling and Epistasis: Autoregressive generative models represent a paradigm shift in ASR, moving beyond site-independent evolutionary models to capture context-dependent effects [4]. These approaches leverage deep learning architectures trained on diverse sequence families to infer evolutionary constraints, potentially enabling more accurate resurrection of complex functional attributes. Future developments will likely integrate structural and functional data directly into the reconstruction process, bridging sequence evolution with phenotypic consequences.

Indel-Aware Phylogenetics: Current efforts to handle insertion and deletion events more rigorously are advancing through problems like the Deletion-Only Parsimony Problem, which provides mathematical foundations for representing uncertainty in gap placement [9]. Next-generation algorithms will need to efficiently handle both insertions and deletions while accommodating varying evolutionary models across sequence regions, particularly important for studying protein families with domain shuffling or flexible regions.

Integrated Paleobiology: ASR increasingly combines with other computational paleobiology approaches, including paleoclimate reconstruction and biogeochemical modeling, to contextualize ancestral protein functions within ancient environments [11]. This interdisciplinary synthesis enables more nuanced hypotheses about selective pressures that shaped molecular evolution across Earth's history.

Experimental High-Throughput Characterization: As gene synthesis costs decline, researchers can implement library-based approaches that characterize numerous alternative reconstructions, directly addressing uncertainty in ancestral inferences [3] [10]. These empirical measurements of sequence-function relationships across reconstructed variants provide rich datasets for refining evolutionary models and understanding neutral networks in protein space.

The historical trajectory from Pauling and Zuckerkandl's theoretical insights to today's sophisticated computational frameworks demonstrates how ASR has matured into an indispensable tool for evolutionary biochemistry. As methodological innovations continue to enhance reconstruction accuracy and expand applicable protein families, ASR promises to deliver increasingly profound insights into life's evolutionary history while providing engineered proteins with novel properties for biomedical and industrial applications.

Ancestral sequence reconstruction (ASR) is a computational technique in molecular evolution used to infer the sequences of ancient, extinct proteins from the sequences of their modern, extant homologs [1]. The fundamental principle underlying ASR is that closely related species share similar DNA and protein sequences due to their common evolutionary origin [1]. By comparing multiple extant sequences, researchers can deduce the sequences of their ancestors at specific nodes in the evolutionary tree. This technique, first suggested by Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl in 1963, has evolved into a powerful tool for studying molecular evolution, enabling researchers to "resurrect" and experimentally characterize ancestral proteins [1]. The method provides a unique window into evolutionary history, allowing scientists to test hypotheses about the evolution of protein structure and function, ancient environments, and the functional consequences of specific historical mutations [12] [13].

Theoretical Foundations of ASR

The Evolutionary Basis for Reconstruction

ASR operates on the well-established principle that modern protein sequences share common ancestry and have diversified through evolutionary processes including mutation, selection, and genetic drift [1]. When two species differ at a specific sequence position, and outgroup sequences show consistency with one of the variants, we can infer the ancestral state and identify which lineage acquired a mutation [1]. This logic extends across entire protein families and evolutionary trees. The reliability of ASR stems from the statistical nature of sequence evolution and the fact that back-mutations (where a position mutates and then reverts) are statistically unlikely, making evolutionary paths traceable through comparative analysis [1].

Critically, ASR does not claim to recreate the exact historical sequence that existed millions of years ago. Instead, it produces a sequence that is statistically likely to be similar and, most importantly, to share the phenotypic properties of the ancient protein [1]. This approach aligns with the 'neutral network' model of protein evolution, which proposes that at evolutionary junctions, populations contained genotypically different but phenotypically similar protein sequences [1]. Therefore, while a reconstructed sequence may not be genetically identical to the last common ancestor, it likely represents the functional characteristics of the ancestral protein.

Key Algorithmic Approaches

Multiple computational approaches have been developed for ASR, each with distinct theoretical foundations and assumptions:

Maximum Parsimony (MP): This method reconstructs sequences based on the principle that the evolutionary path requiring the smallest number of sequence changes is the most likely [1]. MP operates on Occam's razor logic, seeking the most evolutionarily efficient route. However, it is often considered less reliable for reconstructing very ancient sequences because it arguably oversimplifies evolutionary processes by not adequately accounting for multiple substitutions at the same site or varying evolutionary rates across lineages [1].

Maximum Likelihood (ML): ML methods represent a more sophisticated approach that uses probabilistic models of sequence evolution. For each sequence position, ML calculates the most likely ancestral state based on the extant sequences, a defined phylogenetic tree, and an explicit model of sequence evolution that includes factors like substitution patterns and rate variation across sites [14] [1]. ML methods can incorporate empirical observations about evolutionary processes, such as the fact that transitions between similar amino acids occur more frequently than transversions [15].

Bayesian Methods: These approaches complement ML methods but typically produce more ambiguous reconstructions [1]. Bayesian frameworks incorporate prior knowledge or assumptions about evolutionary parameters and generate posterior distributions of possible ancestral sequences, allowing researchers to quantify uncertainty in their reconstructions. This is particularly valuable for positions where no clear ancestral state can be determined.

Table 1: Comparison of Major ASR Methodological Approaches

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) | Minimizes the total number of sequence changes required [1] | Computationally simple; intuitive logic | Often oversimplifies evolution; less accurate for deep reconstructions [1] |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) | Finds the sequence that maximizes the probability of observing the extant sequences [14] [1] | Accounts for varying evolutionary rates; generally more reliable than MP [14] | Computationally intensive; requires accurate evolutionary model |

| Bayesian Methods | Estimates posterior distribution of ancestral states given the data and priors [1] | Quantifies uncertainty in reconstructions | Can produce ambiguous sequences; computationally complex [1] |

Methodological Implementation

Core Workflow and Data Requirements

The implementation of ASR follows a systematic workflow that transforms a set of modern sequences into inferred ancestral proteins. The key stages of this process are visualized in the following workflow diagram:

The process begins with the collection of homologous protein sequences from extant organisms. These sequences must share common ancestry but display sufficient variation to provide meaningful evolutionary signal [1]. The quality and diversity of this initial sequence set significantly impacts the accuracy of the final reconstruction.

The next critical step involves creating a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) to identify corresponding positions across all sequences [1] [6]. This alignment step is crucial as it establishes positional homology, ensuring that evolutionarily related sites are compared correctly. Modern MSA methods like Clustal Omega, MUSCLE, and MAFFT use progressive alignment strategies that begin with the most similar sequences and progressively add more divergent ones [6].

Following alignment, a phylogenetic tree is constructed to represent the evolutionary relationships among the sequences [1]. This tree provides the structural framework for reconstruction, as the branching patterns and branch lengths dictate the probabilistic calculations used in ML and Bayesian methods. Branch lengths are particularly important as they represent the amount of evolutionary change that has occurred along each lineage [14].

Advanced Considerations in Reconstruction

Modern ASR implementations incorporate several sophisticated elements that significantly improve reconstruction accuracy:

Rate Variation Across Sites: Evolutionary rates vary substantially across different positions in a protein due to varying structural and functional constraints [14]. Methods like ANCESCON address this by estimating position-specific evolutionary rates (α) using either an empirical method (αAB) based on sequence conservation or a maximum likelihood approach (αML) [14]. Accounting for this rate heterogeneity prevents systematic underestimation of evolutionary distances and improves the accuracy of ancestral state inference [14].

Epistasis and Context Dependence: Traditional models assume sequence positions evolve independently, but recent advances incorporate epistasis—the fact that the effect of a mutation depends on the rest of the sequence [15]. Newer methods like autoregressive models (e.g., ArDCA) model conditional probabilities between positions, creating more evolutionarily realistic reconstructions that account for co-evolution and structural constraints [15].

Model Selection and Optimization: The choice of substitution model and its parameters significantly influences reconstruction outcomes. Modern implementations often include optimization of background amino acid frequencies (π) and other model parameters specific to the protein family under study [14]. This customization improves the fit between the evolutionary model and the actual patterns observed in the alignment.

Table 2: Advanced Modeling Considerations in ASR

| Consideration | Description | Impact on Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| Rate Variation Across Sites | Different positions evolve at different rates due to structural/functional constraints [14] | Prevents distance underestimation; improves accuracy [14] |

| Epistasis | The effect of a mutation depends on the genetic background [15] | Better captures structural constraints; more biophysically realistic [15] |

| Model Optimization | Tuning evolutionary model parameters to specific protein family [14] | Improves fit to data; more accurate ancestral states |

Experimental Validation and Applications

Validation of Reconstructed Sequences

The computational reconstruction of ancestral sequences represents only the first step in a complete ASR study. Experimental validation is crucial for verifying the functional plausibility of the inferred sequences and testing evolutionary hypotheses [1]. The validation process typically involves:

Gene Synthesis and Protein Expression: Once ancestral sequences are computationally inferred, the corresponding genes are synthesized artificially and expressed in host systems (typically E. coli or yeast) to produce the ancestral proteins [1]. This "resurrection" of ancient proteins enables direct experimental characterization of their properties.

Biophysical and Biochemical Characterization: The expressed ancestral proteins undergo comprehensive analysis of their structural stability, catalytic activity (for enzymes), ligand binding specificity, and other functional properties [1] [13]. This experimental validation helps confirm that the reconstructed sequences represent functional proteins rather than computational artifacts.

Control Experiments: To address concerns that ASR might produce "consensus-like" sequences with artificially enhanced properties, researchers typically conduct control experiments including expressing consensus sequences and performing parallel reconstructions using different algorithms [1]. These controls help distinguish genuine ancestral characteristics from potential methodological artifacts.

A notable finding across many ASR studies is the so-called "ancestral superiority" phenomenon, where reconstructed ancestral proteins often exhibit enhanced stability, catalytic activity, or catalytic promiscuity compared to their modern counterparts [1]. While this pattern has been attributed by some to artifacts of the reconstruction process, it may also reflect genuine evolutionary optimization or adaptation to different ancient environmental conditions [1].

Research Applications and Case Studies

ASR has enabled groundbreaking insights across diverse areas of molecular evolution and protein science:

Enzyme Evolution and Functional Divergence: ASR has been used to trace the evolutionary history of enzymes like yeast alcohol dehydrogenases (Adhs), revealing how gene duplication and functional divergence led to specialized metabolic functions [1]. These studies can pinpoint the specific historical mutations that led to changes in substrate specificity or catalytic efficiency.

Environmental Adaptation: Reconstruction of ancestral thioredoxin enzymes dating back ~4 billion years revealed proteins with significantly elevated thermal and acidic stability compared to modern versions, potentially reflecting adaptation to ancient environmental conditions [1]. Similarly, studies of elongation factor thermo-unstable (EF-Tu) proteins support a hotter Precambrian Earth, consistent with geological evidence [1].

Molecular Mechanism Elucidation: By resurrecting ancestral steroid hormone receptors, researchers have identified the specific historical mutations that altered ligand specificity, providing mechanistic insights into how hormone signaling evolved [1]. This historical approach often reveals functional residues that are not apparent from comparisons of only extant proteins [13].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ASR

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in ASR |

|---|---|---|

| ANCESCON | Software Package | Distance-based phylogenetic inference and ancestral reconstruction incorporating rate variation [14] |

| PAML | Software Package | Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood; implements various evolutionary models [14] |

| ArDCA | Generative Model | Autoregressive model incorporating epistasis for improved reconstruction accuracy [15] |

| Clustal Omega/MUSCLE/MAFFT | Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | Align homologous sequences to establish positional homology [6] |

| Heterologous Expression System | Experimental Platform | Produce protein from synthesized ancestral genes (e.g., E. coli, yeast) [1] |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Despite its power, ASR methodology faces several important technical challenges that researchers must consider when designing studies:

Phylogenetic Tree Quality: The accuracy of ancestral reconstruction is heavily dependent on the quality of the underlying phylogenetic tree [14]. Errors in tree topology or branch length estimation propagate directly to the reconstructed sequences. Methods like "Weighbor" (weighted neighbor joining) that account for larger errors in longer distance estimates can improve tree construction [14].

Sequence Alignment Accuracy: Incorrect alignment of homologous positions represents a major source of error in ASR [6]. This is particularly challenging for very divergent sequences or proteins with complex domain architectures. Iterative alignment methods and consensus approaches that combine multiple alignments can help mitigate this issue [6].

Model Misspecification: All ASR methods depend on models of sequence evolution, and inaccuracies in these models can bias results [15]. The common assumption of site-independent evolution is particularly problematic, as it ignores epistatic interactions that shape protein evolution [15]. Emerging methods that incorporate co-evolution and epistasis represent promising advances addressing this limitation.

Ambiguity and Uncertainty: All reconstructed sequences contain positions with uncertain ancestral states [1]. Bayesian methods can quantify this uncertainty, and experimental studies often characterize multiple reconstructions for the same node to account for this ambiguity [1]. The field increasingly recognizes that ASR produces plausible ancestral sequences rather than definitively correct ones.

Molecular Clock Assumptions: Dating of ancestral nodes typically relies on molecular clock models with substantial error margins [1]. These dating uncertainties complicate correlations between ancestral protein properties and specific historical environments or evolutionary events.

Ancestral sequence reconstruction represents a powerful synthesis of computational biology and experimental biochemistry that enables researchers to travel back in time to characterize ancient proteins. The core principles of ASR—using the statistical patterns of sequence evolution across extant homologs to infer ancestral states—have proven remarkably productive for addressing diverse questions in molecular evolution [13]. As methods continue to advance, particularly through better modeling of epistasis and rate heterogeneity, and through integration with structural and functional data, ASR promises to deliver even deeper insights into the evolutionary history of proteins and the processes that have shaped biological diversity over billions of years [14] [15] [12]. The technique has evolved from a specialized method to an essential tool for understanding how protein structure, function, and interactions have changed throughout evolutionary history.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) has emerged as a powerful phylogenetic tool that enables scientists to infer the sequences of ancient proteins, providing a unique window into molecular evolution. By combining bioinformatics with experimental biochemistry, ASR allows researchers to test hypotheses about the evolutionary history of protein stability, function, and adaptation. This technical review examines how ASR has revealed fundamental insights into protein thermostability, demonstrating that ancestral proteins often exhibit remarkable thermal stability compared to their modern counterparts. We explore the mechanistic basis for these properties, the methodologies enabling these discoveries, and the applications of resurrected ancestral proteins in industrial and pharmaceutical contexts. The evidence synthesized here supports the conclusion that ASR not only illuminates evolutionary trajectories but also provides engineered proteins with enhanced stability for biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) is a computational methodology that infers the most probable genetic or protein sequences of extinct ancestors using phylogenetically related sequences from contemporary species [16] [17]. This approach leverages the traceable imprints of evolutionary processes preserved in modern sequences, allowing researchers to reconstruct molecular history with remarkable precision. ASR has transformed evolutionary biochemistry by providing direct experimental access to ancient proteins, enabling empirical characterization of their biophysical and functional properties.

The foundational principle of ASR rests on the comparison of multiple extant sequences to deduce ancestral states within an evolutionary framework. The technique requires several key components: a multiple sequence alignment of modern proteins, a phylogenetic tree depicting evolutionary relationships, branch lengths representing divergence times, and a stochastic substitution model describing probabilities of sequence changes over time [18] [19]. The accuracy of reconstruction depends critically on each of these elements, with phylogenetic signal strength being the primary determinant of reliability rather than sophisticated substitution models [18].

ASR has gained prominence in protein engineering and evolutionary studies due to its unique ability to generate highly stable and functional protein variants. Unlike rational design or directed evolution approaches, ASR leverages billions of years of natural evolutionary information captured in sequence databases, often yielding proteins with enhanced thermostability, solubility, and promiscuous functions [20] [10] [21]. These properties make ASR particularly valuable for industrial enzymology and therapeutic protein development, where stability under challenging conditions is paramount.

Methodological Framework of ASR

Computational Approaches and Workflow

The ASR workflow follows a systematic pipeline from sequence collection to ancestral inference, with each stage critical for accurate reconstruction. The process begins with comprehensive sequence identification and curation, followed by multiple sequence alignment to establish homologous positions. Phylogenetic tree construction then provides the evolutionary framework for reconstructing ancestral states using statistical models [19].

Three primary computational methods are employed in ASR:

Maximum Parsimony (MP): This non-parametric method minimizes the total number of character changes along the phylogenetic tree, providing the simplest evolutionary explanation. While computationally efficient, MP may oversimplify complex evolutionary scenarios with multiple substitutions at single sites [19].

Maximum Likelihood (ML): As the most widely used approach, ML employs parametric models of sequence evolution to find ancestral states that maximize the probability of observing the extant sequences. ML incorporates branch lengths and explicit evolutionary models (e.g., Jukes-Cantor, Kimura models), providing more statistically robust inferences, especially for deep evolutionary reconstructions [20] [19].

Bayesian Inference (BI): This method incorporates prior knowledge and calculates posterior probability distributions of ancestral states using Bayes' theorem. BI quantifies uncertainty in ancestral state estimates and allows integration of diverse information sources, such as fossil records and molecular clocks [19].

Table 1: Comparison of ASR Computational Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Parsimony | Minimizes total character changes | Computational efficiency; intuitive simplicity | Sensitive to homoplasy; ignores branch lengths |

| Maximum Likelihood | Maximizes probability of observed data | Accounts for branch lengths; robust statistical framework | Computationally intensive; model dependency |

| Bayesian Inference | Calculates posterior probability of ancestral states | Quantifies uncertainty; integrates prior knowledge | Complex implementation; computationally demanding |

Addressing Reconstruction Uncertainties

ASR robustness depends on careful consideration of potential uncertainties and biases. Key concerns include phylogenetic ambiguity, model misspecification, and limited sequence sampling. Statistical support for inferred ancestral states can be assessed through bootstrapping or posterior probabilities [19]. Recent experimental evidence suggests that ASR is surprisingly robust to unincorporated evolutionary heterogeneity, with phylogenetic signal strength being more critical than model complexity [18].

Systematic biases potentially affecting thermostability inferences have been carefully evaluated. While some simulations suggested that maximum likelihood methods might artificially inflate ancestral stability predictions, experimental tests of multiple alternative reconstructions have generally demonstrated robustness of thermostability conclusions [22]. For example, Hart et al. measured ten alternate sequences of a ~3 billion year-old RNase H ancestor and found consistently elevated thermostability (Tm = 76.7 ± 2 °C) compared to modern Escherichia coli RNase H (Tm = 68.0 °C) [22].

ASR Reveals Evolutionary Trends in Protein Thermostability

Evidence for Ancestral Thermostability

Empirical studies across diverse protein families have consistently demonstrated that reconstructed ancestral proteins exhibit significantly enhanced thermostability compared to their modern counterparts. This trend is particularly evident in deep evolutionary reconstructions dating to the Precambrian era. Key examples include:

Elongation Factor-Tu (EF-Tu): Reconstructed ancestral variants showed thermostability far exceeding contemporary mesophilic forms, with inferred environmental temperatures of ancient ancestors resembling modern thermophiles [22].

β-lactamases: Precambrian resurrected enzymes displayed melting temperatures (Tm) substantially higher than their extant descendants, with some ancestral forms tolerating temperatures ~30°C higher and ≥100 times longer incubations than modern versions [21] [22].

Steroid hormone receptors: Ancestral DNA-binding domains exhibited remarkable thermal stability while maintaining functional plasticity, enabling evolutionary biochemistry studies not possible with modern proteins [18].

Cytochrome P450 enzymes: Ancestral vertebrate CYP3 P450 ancestors demonstrated a T50 of 66°C and enhanced solvent tolerance compared to human drug-metabolizing CYP3A4, yet comparable activity toward a broad substrate range [21].

Ketol-acid reductoisomerases: Ancestral forms showed an eight-fold higher specific activity than the cognate Escherichia coli enzyme at 25°C, which increased 3.5-fold at 50°C, highlighting both thermostability and enhanced catalytic efficiency [21].

Table 2: Thermostability Measurements of Ancestral vs. Modern Proteins

| Protein Family | Ancestral Tm/Т50 (°C) | Modern Tm/Т50 (°C) | Stability Increase | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebrate CYP3 P450 | 66.0 (T50) | ~6.0 (T50 for modern) | ~60°C T50 increase | [21] |

| β-lactamase | >70.0 | ~45.0 | >25°C Tm increase | [22] |

| EF-Tu | ~85.0 | ~55.0 | ~30°C Tm increase | [22] |

| Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | N/A | N/A | 3.5-fold activity increase at 50°C | [21] |

| RNase H (3 BYA ancestor) | 76.7±2.0 | 68.0 | ~8.7°C Tm increase | [22] |

Environmental Influences and Evolutionary Timing

The elevated thermostability of ancient proteins correlates with Earth's geological history. Analysis of reconstructed proteins suggests that deep ancestors had stability profiles similar to modern thermophiles, with a transition toward lower thermostability occurring as Earth cooled. When melting temperatures are converted to environmental temperature estimates using empirical relationships (Tm generally rises ~1°C per 1°C of environmental temperature), reconstructed proteins indicate elevated environmental temperatures ~3 billion years ago [22].

A study of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (IPMDH) revealed that a dramatic improvement in low-temperature catalytic activity occurred between the fifth (Anc05) and sixth (Anc06) intermediate ancestors, coinciding with the Great Oxidation Event 2.5-2.1 billion years ago, which led to global cooling [17]. This suggests that climate shifts drove enzyme adaptation to lower temperatures, with key mutations occurring distant from active sites enabling enhanced efficiency at cooler temperatures through structural dynamics modifications [17].

Molecular Mechanisms of Thermal Adaptation

Structural Determinants of Thermostability

ASR studies have identified several key structural mechanisms that contribute to ancestral thermostability:

Improved hydrophobic core packing: Ancestral sequences often feature optimized hydrophobic interactions in protein cores, reducing cavity formation and enhancing stability [20].

Stabilizing salt bridges and electrostatic interactions: Networks of charge-stabilized interactions provide additional stabilizing energy in ancestral proteins compared to modern counterparts [20].

Loop stabilization and rigidification: Shortened loops and strategic proline substitutions reduce conformational flexibility in regions prone to unfolding initiation [20].

Enhanced oligomeric interfaces: In multimeric proteins, ancestral forms often exhibit strengthened subunit interfaces contributing to overall stability [10].

Interestingly, the specific structural mechanisms underlying thermostability can vary significantly among ancestral nodes within the same protein family. A study of RNase H evolution revealed that thermodynamic stabilization mechanisms fluctuated even as thermal denaturation temperatures varied smoothly, indicating that evolution can access alternate structural solutions to maintain stability under environmental selection pressures [22].

Dynamic Properties and Allosteric Regulation

Beyond static structural features, protein dynamics play a crucial role in thermal adaptation. Research on 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase (IPMDH) demonstrated that key mutations distant from active sites enabled conformational shifts enhancing catalytic efficiency at lower temperatures [17]. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that intermediate ancestral enzymes between Anc05 and Anc06 underwent a structural shift from open to partially closed conformations, reducing activation energy and improving low-temperature activity [17].

This highlights that allosteric regions—often far from catalytic sites—significantly influence temperature adaptation through modulation of structural dynamics and conformational landscapes. These dynamic properties buffer the often destabilizing effects of mutations introduced to improve other properties, explaining why robust protein scaffolds are better able to accept potentially destabilizing mutations that confer novel activities [20].

Experimental Validation and Applications

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Ancestral Proteins

The experimental validation of computationally reconstructed ancestral proteins follows a standardized workflow:

Gene Synthesis and Protein Expression

- Computational sequence optimization: Codon-optimize inferred ancestral sequences for target expression systems (typically E. coli)

- Gene synthesis: De novo synthesis of ancestral gene sequences

- Vector cloning: Insertion into appropriate expression vectors with affinity tags

- Recombinant expression: Protein production in host systems, often with temperature optimization

- Purification: Affinity and size-exclusion chromatography to obtain pure, monodisperse protein [10] [21]

Biophysical Characterization

- Thermal stability assays: Measurement of melting temperatures (Tm) using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) or fluorometric methods with dyes like SYPRO Orange

- Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy: Assessment of secondary structure content and stability under thermal denaturation

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS): Evaluation of monodispersity and aggregation state

- X-ray crystallography/Cryo-EM: Structural determination to identify stabilization features [10] [22]

Functional Characterization

- Enzyme kinetics: Determination of kcat, KM, and catalytic efficiency across temperature gradients

- Substrate profiling: Assessment of substrate specificity and promiscuity

- Long-term stability: Measurement of functional half-life under storage and operational conditions [21]

Research Reagent Solutions for ASR Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASR Experimental Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in ASR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | PAML, MEGA, HyPhy, IQ-TREE | Phylogenetic analysis, ancestral sequence inference, evolutionary model testing |

| Gene Synthesis Services | Custom gene synthesis providers | De novo production of optimized ancestral gene sequences |

| Expression Systems | E. coli strains (BL21, Rosetta), cell-free systems | Recombinant production of ancestral proteins |

| Purification Tags | His-tag, GST-tag, MBP-tag | Affinity purification of expressed ancestral proteins |

| Stability Assay Reagents | SYPRO Orange, DSC instruments, CD spectrometers | Measurement of thermal denaturation profiles and melting temperatures |

| Structural Biology Tools | Crystallization screens, Cryo-EM grids | Determination of high-resolution structures of ancestral proteins |

| Activity Assays | Substrate libraries, spectrophotometric assays | Functional characterization of ancestral enzyme kinetics and specificity |

Applications in Biotechnology and Medicine

The unique properties of ancestral proteins resurrected through ASR have enabled diverse applications:

Industrial biocatalysis: Thermostable ancestral enzymes withstand harsh industrial process conditions, enable higher temperature reactions for improved yields, reduce microbial contamination, and provide longer operational lifetimes [20] [21]. For example, ancestral cytochrome P450s and ketol-acid reductoisomerases have been employed in chemical synthesis and biofuel production [21].

Therapeutic protein engineering: Enhanced stability of ancestral proteins translates to longer shelf life for protein therapeutics and broader application contexts [20]. Thermostable ancestral biotin ligases (AirID) have been developed for proximity labeling applications, while stable ancestral L-arginine sensors demonstrate diagnostic potential [10].

Structural biology enablement: Crystallization-resistant modern proteins often yield to structural analysis when ancestral stabilized variants are used [10]. The structural analysis of modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) was enabled by creating chimeric didomains containing ancestral acyltransferase (AncAT) domains, allowing high-resolution crystal and cryo-EM structures previously unattainable [10].

Synthetic biology: Robust ancestral protein 'biobricks' provide stable, standardized components for building bioinspired devices [20]. Their enhanced stability buffers destabilizing mutations introduced for novel functions, making them ideal platforms for further engineering.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction has fundamentally advanced our understanding of protein evolution and thermostability. The accumulating evidence from diverse protein families strongly indicates that ancient proteins were often remarkably thermostable, with systematic decreases in stability occurring as Earth's environment cooled over geological timescales. Beyond this overarching trend, ASR reveals the intricate structural and dynamic mechanisms governing thermal adaptation, providing protein engineers with novel strategies for stabilizing modern proteins.

The experimental resurrection of ancestral proteins has transitioned from evolutionary curiosity to practical engineering strategy, yielding robust enzymes and proteins with enhanced properties for industrial, therapeutic, and research applications. As sequence databases expand and computational methods refine, ASR promises continued insights into life's molecular history while providing increasingly sophisticated protein engineering solutions for contemporary challenges.

The integration of ASR with structural biology, directed evolution, and rational design represents a powerful synthetic approach for developing functional proteins that transcend natural variation. By learning from evolutionary history, researchers can create novel proteins optimized for human needs while deepening fundamental understanding of the principles governing protein structure, function, and stability.

Key Biological Questions Addressed by Foundational ASR Studies

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) has emerged as a powerful methodology in evolutionary biology, enabling researchers to formulate and answer fundamental biological questions that are otherwise inaccessible through the study of modern sequences alone. By inferring and resurrecting the sequences of ancient proteins and genomes, ASR allows for the direct experimental testing of hypotheses concerning molecular evolution, protein function, and the origins of biological diversity. This technical guide details the key biological questions addressed by foundational ASR studies, provides detailed experimental protocols, and outlines the essential reagents and analytical tools required for conducting such research. Framed within the broader context of ancestral sequence reconstruction techniques, this review serves as a resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to apply paleogenetics to problems in protein engineering, evolutionary biochemistry, and therapeutic design.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) is a computational and experimental technique that infers the sequences of ancient genes and proteins from the phylogenetic analysis of extant sequences, followed by their synthesis and functional characterization in the laboratory [2] [23]. The concept, first proposed by Pauling and Zuckerkandl, posits that biological sequences document evolutionary history, and with sufficient genetic information, the temporal accumulation of mutations can be traced backward to reconstruct sequences from long-lost common ancestors [23] [24]. The subsequent "resurrection" of these ancestral proteins in the lab opens fascinating avenues to test evolutionary hypotheses concerning enzyme mechanism, protein stability, and the functional adaptations that have shaped modern biological systems [2] [23]. Beyond evolutionary studies, ASR has found significant applications in protein engineering and industrial biotechnology, where ancestral proteins often exhibit enhanced stability and novel functions [10].

Key Biological Questions and Findings

Foundational ASR studies have been instrumental in addressing several core questions in molecular evolution. The table below summarizes the primary biological questions, key findings, and the evolutionary implications derived from seminal ASR research.

Table 1: Key Biological Questions Addressed by Foundational ASR Studies

| Biological Question | Key Finding from ASR | Implication for Molecular Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Protein Promiscuity & Specificity | Ancestral proteins were often more promiscuous, with specificity refining after gene duplication events [2]. | Supports the "gene duplication and functional refinement" model of protein family evolution. |

| 2. Origins of New Functions | New protein functions can evolve de novo from ancestors lacking those functions via a few key mutations [2]. | Suggests the acquisition of new functions is neither difficult nor rare, though stabilizing them is. |

| 3. Historical Substitutions & Epistasis | Horizontal "swap" experiments between extant proteins often fail due to epistasis; ASR identifies functionally compatible historical paths [2]. | Highlights the importance of historical context and pervasiveness of intragenic epistasis in shaping modern protein functions. |

| 4. Evolution of Complex Systems | ASR of modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) enabled high-resolution structural analysis, revealing evolutionary mechanisms in biosynthetic pathways [10]. | Provides a tool for structural analysis of complex, dynamic proteins that are difficult to study with modern sequences alone. |

| 5. Reconstruction of Ancient Genomes | Algorithmic development (e.g., AGORA) allows reconstruction of ancestral gene content and order across hundreds of eukaryotic ancestors [24]. | Enables the study of large-scale genomic events (rearrangements, duplications) and their role in evolution and disease. |

Evolutionary Mechanisms and Protein Dynamics

A primary application of ASR has been to dissect the evolutionary mechanisms behind functional diversification in protein families. Studies have challenged a purely reductionist view by demonstrating that the functional properties of modern proteins are not solely the result of optimization for current roles but are also constrained by their evolutionary history [2]. A key finding is the role of intragenic epistasis, where the effect of a mutation depends on the genetic background in which it occurs. This explains why horizontal swap experiments of amino acids between extant homologs often fail to interconvert function, as the swapped residues may be incompatible with the recipient's background [2]. ASR overcomes this by identifying the specific, historically accurate substitutions that occurred along evolutionary lineages, allowing researchers to trace the step-wise acquisition of new functions without the confounding effects of modern epistatic networks.

Structural Biology and Enzyme Engineering

ASR has proven particularly valuable in structural biology, especially for proteins that are difficult to crystallize due to flexibility or instability. A 2025 study on the FD-891 polyketide synthase (PKS) loading module exemplifies this. Researchers replaced the native acyltransferase (AT) domain with a reconstructed ancestral AT (AncAT) to create a KSQAncAT chimeric didomain [10]. This chimeric protein retained enzymatic function but exhibited properties amenable to crystallization, enabling the determination of a high-resolution crystal structure and cryo-EM structures that were unattainable with the native, more flexible protein [10]. This demonstrates ASR's utility as a protein engineering tool to enhance stability and solubility for structural analysis, providing deeper mechanistic insights into complex multi-domain enzymes like modular PKSs [10].

Experimental Protocols in ASR

The process of ancestral sequence reconstruction and characterization follows a structured pipeline, from sequence collection to functional assays. The workflow below outlines the major stages of a typical ASR study.

Diagram 1: ASR Experimental Workflow

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Reconstruction

The foundation of a robust ASR study is an accurate multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and a reliable phylogenetic tree.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): The first step involves gathering a comprehensive set of extant protein sequences homologous to the protein of interest. These sequences are then aligned using algorithms such as MAFFT or PRANK [23]. The choice of alignment tool is critical, as it can introduce biases in the inferred ancestral sequences. Some studies improve accuracy by integrating results from multiple alignment algorithms [23].

- Phylogenetic Tree Construction: A phylogenetic tree depicting the evolutionary relationships between the aligned sequences is built using Maximum Likelihood (ML) or Bayesian methods [23]. The tree topology and branch lengths are essential inputs for the subsequent ancestral state inference. While uncertainty in the true phylogeny exists, ASR has been shown to be robust to this uncertainty, with ML methods performing well without integrating over tree topologies [23].

Ancestral Sequence Inference

With the MSA and phylogenetic tree, the ancestral states at each node of the tree can be inferred. The two primary probabilistic approaches are:

- Maximum Likelihood (ML): ML methods, as implemented in software like PAML (via the

codemlprogram), calculate the most probable ancestral sequence at a given node based on the extant sequences, the tree, and a specified model of sequence evolution [23]. Model selection (e.g., LG, WAG) is typically performed using likelihood-based methods to find the best-fitting model for the data [23]. - Bayesian Methods: Bayesian approaches (e.g., implemented in MrBayes) integrate over uncertainty in the reconstruction by sampling from the posterior distribution of ancestral states. While this can account for uncertainty in the tree and model parameters, computational studies suggest it may not significantly improve accuracy over ML methods for ASR [23].

After inference, the predicted ancestral sequences are manually curated, and the corresponding genes are synthesized de novo for laboratory resurrection.

Functional and Structural Characterization

The resurrected ancestral proteins are expressed and purified using standard recombinant protein techniques. Their functional characterization is then tailored to the specific protein family but generally includes:

- Activity Assays: Measuring enzymatic kinetics (Km, kcat) to compare efficiency and substrate specificity with modern counterparts [2] [23].

- Stability Profiling: Assessing thermal stability (e.g., by measuring melting temperature, Tm) and solubility. Ancestral proteins often show enhanced thermostability [10] [23].

- Structural Analysis: Determining three-dimensional structures using X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to provide mechanistic insights into functional changes [10]. As demonstrated with the PKS system, ancestral domains can facilitate structural studies of otherwise intractable proteins [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of an ASR study relies on a suite of computational tools, laboratory reagents, and experimental materials. The following table catalogues the key resources required.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for ASR

| Category | Item/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | MAFFT, PRANK | Generation of multiple sequence alignments from extant sequences [23]. |

| IQ-TREE, MrBayes, RAxML | Construction of phylogenetic trees from sequence alignments [23]. | |