Benchmarking AI in Evolutionary Genomics: From Foundational Models to Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the rapidly evolving field of AI benchmarking in evolutionary genomics.

Benchmarking AI in Evolutionary Genomics: From Foundational Models to Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the rapidly evolving field of AI benchmarking in evolutionary genomics. It explores the foundational need for standardized evaluation, detailing core community-driven initiatives like the Virtual Cell Challenge and CZI's benchmarking suite. The piece delves into key methodological applications, from predicting protein structures with tools like Evo 2 and AlphaFold to simulating cellular responses to genetic perturbations. It addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for overcoming data noise and model overfitting. Finally, it establishes a framework for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of AI models, synthesizing key takeaways to highlight how robust benchmarking is accelerating the translation of genomic insights into therapeutic discoveries.

The Critical Need for Standardized AI Benchmarks in Evolutionary Genomics

The field of genomics is in the midst of an unprecedented data explosion. Driven by precipitous drops in sequencing costs and technological advancements, the volume of genomic data being generated is overwhelming traditional computational and analytical methods [1] [2]. Where sequencing a single human genome once cost millions of dollars, it now costs under $1,000, with some providers anticipating costs as low as $200 [1] [2]. This democratization of sequencing has releaseed a data deluge, with a single human genome generating about 100 gigabytes of raw data [1] [3]. By 2025, global genomic data is projected to reach 40 exabytes (40 billion gigabytes), creating a critical bottleneck that challenges supercomputers and Moore's Law itself [1]. This guide examines why traditional analysis methods are failing and how artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as an essential solution, with a specific focus on benchmarking AI predictions in evolutionary genomics research.

The Scale of the Genomic Data Challenge

The data generated in genomics is not only vast but also exceptionally complex. Traditional analytical methods, often reliant on manual curation and linear statistical models, are proving inadequate for several reasons.

- Volume and Velocity: Large-scale research initiatives, such as the UK Biobank or the 1000 Genomes Project, sequence hundreds of thousands of individuals [4]. At a theoretical maximum, institutions like the Garvan Institute of Medical Research could generate over 1.5 petabytes of data per year from whole-genome sequencing alone [3]. This volume makes data storage, transfer, and management a primary challenge and cost center.

- Data Heterogeneity: Modern genomics relies on multi-omics approaches that integrate genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics [4] [5]. Combining these diverse data types into a coherent analytical framework is beyond the scope of traditional bioinformatics pipelines.

- Interpretation Complexity: The genome is a dynamic system with complex interactions. A key challenge is interpreting the non-coding genome, which makes up 98% of our DNA and contains critical regulatory elements [1]. Furthermore, understanding the functional consequences of genetic variants requires analyzing their impact across multiple biological scales, a task perfectly suited for AI's pattern-recognition capabilities [4] [1].

Traditional Analysis vs. AI-Enabled Approaches: A Comparative Analysis

The following table provides a structured comparison of the performance and characteristics of traditional analytical methods versus modern AI-enabled approaches across key parameters in genomic analysis.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. AI-Enabled Genomic Analysis

| Parameter | Traditional Analysis | AI-Enabled Analysis | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Calling Accuracy | Relies on statistical models (e.g., GATK). Good for common variants but struggles with complex structural variants. | Higher accuracy using deep learning. Google's DeepVariant treats calling as an image classification problem, outperforming traditional methods [4] [1]. | DeepVariant demonstrates superior precision and recall in benchmark studies, especially for insertions/deletions and in complex genomic regions [1]. |

| Analysis Speed | Slow, computationally expensive pipelines. Can take hours to days for whole-genome analysis. | Drastic acceleration. GPU-accelerated tools like NVIDIA Parabricks can reduce processes from hours to minutes, achieving up to 80x speedups [1]. | Internal benchmarks by tool developers show runtime reduction for HaplotypeCaller from 5 hours to sub-10 minutes on a standard WGS sample [1]. |

| Drug Discovery & Target ID | Hypothesis-driven, low-throughput, and time-intensive. High failure rate (>90%) [1]. | Data-driven, high-throughput analysis of multi-omics data. Identifies novel targets and predicts drug response. | Organizations report a 45% increase in drug design efficiency and a 20% enhancement in therapeutic accuracy using generative AI [2]. |

| Handling of Complex Data | Limited ability to integrate multi-omics data. Struggles with non-linear relationships and high-dimensional data. | Excels at integrating diverse data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) to uncover complex, non-linear patterns [5] [1]. | AI models can predict protein structures (AlphaFold), non-coding function, and patient subgroups from single-cell RNA-seq data, generating testable hypotheses [1] [6]. |

| Data Volume Management | Struggles with petabyte-scale data. Requires constant infrastructure scaling. | AI models can be trained on compressed datasets and run scalable analysis in cloud environments, optimizing compute costs [3]. | Garvan Institute reduced data footprint using lossless compression, enabling cost-effective collaboration and analysis on diverse computing environments [3]. |

Benchmarking AI in Evolutionary Genomics

The promise of AI in genomics can only be realized with robust, community-driven benchmarks that allow researchers to compare models objectively and ensure their biological relevance.

The Need for Standardized Benchmarks

Without unified evaluation methods, the same AI model can yield different performance scores across laboratories due to implementation variations, not scientific factors [6]. This forces researchers to spend valuable time building custom evaluation pipelines instead of focusing on discovery. A fragmented benchmarking ecosystem can also lead to overfitting to small, fixed sets of tasks, where models perform well on curated tests but fail to generalize to new datasets or real-world research questions [6].

Community-Driven Benchmarking Initiatives

Initiatives like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's (CZI) benchmarking suite are designed to address these gaps [6]. This "living, evolving product" provides:

- Standardized Tasks and Metrics: The initial release includes six tasks for single-cell analysis, such as cell type classification and perturbation expression prediction, each paired with multiple metrics for a thorough performance review [6].

- Reproducibility: The suite offers command-line tools and a Python package (

cz-benchmarks) to ensure benchmarking results can be reproduced across different environments [6]. - Biological Relevance: The benchmarks are built with the community to ensure they represent real scientific needs, moving beyond purely technical metrics to those with biological meaning [6].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for AI Genomics Benchmarking

| Category | Tool/Platform Examples | Function in AI Genomics Research |

|---|---|---|

| AI Models & Frameworks | DeepVariant, AlphaFold, Transformer Models (e.g., DNABERT) | Core algorithms for specific tasks like variant calling, protein structure prediction, and sequence interpretation [4] [1]. |

| Benchmarking Platforms | CZI cz-benchmarks, NVIDIA Parabricks | Provide standardized environments and metrics to evaluate the performance, accuracy, and reproducibility of AI models on biological tasks [6]. |

| Data Resources | Sequence Read Archive (SRA), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), ENCODE, AI-ready public datasets (e.g., from Allen Institute) | Large-scale, curated, and often annotated genomic datasets used for training AI models and for held-out test sets in benchmarking [5] [6]. |

| Cloud & HPC Infrastructure | Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Genomics, NVIDIA GPUs (H100) | Scalable computational resources required to store and process massive genomic datasets and run computationally intensive AI training and inference [4] [1]. |

Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking an AI Model for Variant Effect Prediction

This protocol outlines a methodology for evaluating a new AI model designed to predict the functional impact of non-coding genetic variants, a key challenge in evolutionary genomics.

1. Objective: To benchmark the accuracy and generalizability of a novel deep learning model against established baselines in predicting the pathogenicity of non-coding variants.

2. Data Curation & Preprocessing:

- Training Data: Utilize a compendium of epigenomic annotations from the ENCODE and ROADMAP consortia, including chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq), histone modifications (ChIP-seq), and transcription factor binding sites across multiple cell types [5] [7].

- Benchmarking Datasets: Use held-out datasets not seen during training. These should include:

- A set of functionally validated non-coding variants from specialized databases (e.g., promoter or enhancer variants with established regulatory effects).

- A set of common variants from the 1000 Genomes Project to assess the false positive rate in presumably neutral regions [4].

- Preprocessing: Uniformly process all sequencing data through standardized pipelines (e.g., alignment with BWA-MEM, peak calling with MACS2) to ensure consistency [1].

3. Model Training & Comparison:

- Model Architecture: The novel model (e.g., a transformer-based network) is trained to take a genomic sequence window and epigenomic context as input and output a prediction of variant effect.

- Baselines: Compare performance against established models, which could include simpler logistic regression models based on conservation scores, older deep learning models like DeepSEA, and the current state-of-the-art.

- Benchmarking Execution: Run all models on the held-out benchmarking datasets using the CZI

cz-benchmarksframework to ensure a consistent and reproducible evaluation environment [6].

4. Performance Metrics:

- Primary Metrics: Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC).

- Secondary Metrics: Calculate precision, recall, and F1-score at a defined probability threshold to understand clinical applicability.

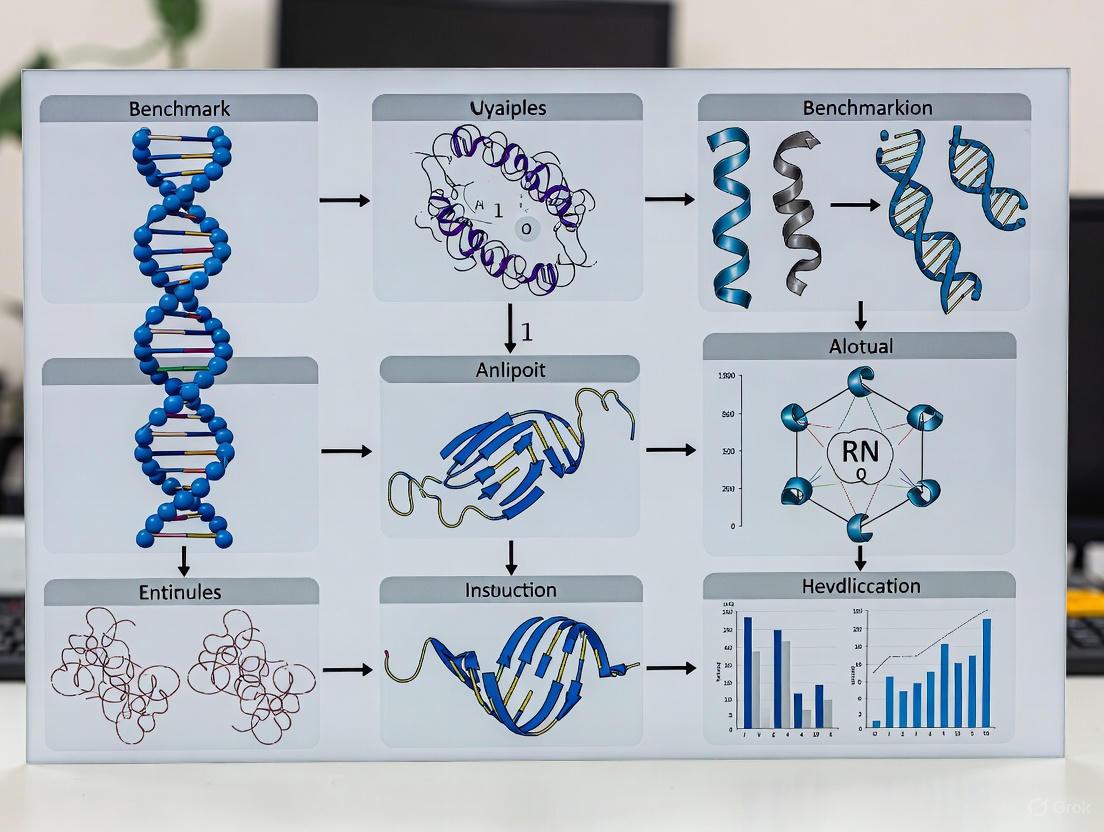

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this benchmarking protocol:

Visualizing Genomic Data and AI Workflows

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting the high-dimensional patterns identified by AI models and for understanding the AI workflows themselves.

Visualizing AI-Based Genomic Analysis

The following diagram maps the logical workflow of a generalized AI-powered genomic analysis system, from raw data to biological insight, highlighting the iterative role of benchmarking.

Advanced Genomic Data Visualization Techniques

As AI models uncover complex patterns, visualization must evolve beyond simple charts [7] [8].

- Circos Plots: Use circular layouts to represent whole genomes, enabling the visualization of intra- and inter-chromosomal relationships, such as translocations, alongside quantitative data like copy number changes in multiple concentric tracks [8].

- Hilbert Curves: A space-filling curve that projects the one-dimensional genome sequence onto a 2D plane, allowing for an aggregated, dense overview of genomic annotations and features across scales [8].

- Hive Plots: Provide a linear layout for network visualization, reducing the "hairball" effect common in transcriptomic networks. They are effective for displaying relationships, such as regulatory interactions between transcription factors, miRNAs, and target genes [8].

The deluge of genomic data has unequivocally overwhelmed traditional analytical methods, creating a pressing need for advanced AI solutions. The integration of machine learning and deep learning is no longer a luxury but a necessity for accelerating variant discovery, unraveling the non-coding genome, and personalizing medicine. However, the rapid adoption of AI must be tempered with rigorous, community-driven benchmarking, as championed by initiatives like the CZI benchmarking suite. For researchers in evolutionary genomics and drug development, the future lies in leveraging these standardized frameworks to build, validate, and deploy AI models that are not only computationally powerful but also biologically meaningful and reproducible. This disciplined approach is the key to transforming the genomic data deluge from an insurmountable obstacle into a wellspring of discovery.

In the rapidly evolving field of evolutionary genomics research, artificial intelligence promises to revolutionize how we interpret genomic data, predict evolutionary patterns, and accelerate drug discovery. However, this potential is being severely hampered by a critical bottleneck: inconsistent and flawed evaluation methodologies. As AI models grow more sophisticated, the absence of standardized, trustworthy benchmarks makes genuine progress increasingly difficult to measure and achieve. Researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals now face a landscape where benchmarking inconsistencies systematically undermine their ability to compare AI tools, validate predictions, and translate computational advances into biological insights.

The fundamental challenge lies in what experts describe as nine key shortcomings in AI benchmarking practices, including issues with construct validity, commercial influences, rapid obsolescence, and inadequate attention to errors and unintended consequences [9]. These limitations are particularly problematic in evolutionary genomics, where the stakes involve understanding complex biological systems and developing therapeutic interventions. With the AI in genomics market projected to grow from USD 825.72 million in 2024 to USD 8,993.17 million by 2033, the absence of reliable evaluation frameworks represents not just a scientific challenge but a significant economic and translational barrier [10].

This comparison guide examines the current benchmarking landscape for AI predictions in evolutionary genomics research, providing objective performance comparisons of available tools, detailed experimental protocols, and standardized frameworks to help researchers navigate this complex terrain. By synthesizing the most current research and community-driven initiatives, we aim to equip genomics professionals with the methodologies needed to overcome the benchmarking bottleneck and drive meaningful progress in the field.

The Current State of AI Benchmarking in Genomics

Fundamental Challenges in Benchmarking AI Systems

The benchmarking crisis in AI for genomics reflects broader issues identified across AI domains. A comprehensive meta-review of approximately 110 studies reveals nine fundamental reasons for caution in using AI benchmarks, several of which are particularly relevant to evolutionary genomics research [9]:

Construct Validity Problems: Many benchmarks fail to measure what they claim to measure, with particular challenges in defining and assessing concepts like "accuracy" and "reliability" in genomic predictions. This makes it impossible to properly evaluate their success in measuring true biological understanding rather than pattern recognition.

Commercial Influences: The roots of many benchmark tests are often commercial, encouraging "SOTA-chasing" where benchmark scores become valued more highly than thorough biological insights [9]. This competitive culture prioritizes leaderboard positioning over scientific rigor.

Rapid Obsolescence: Benchmarks struggle to keep pace with advancing AI capabilities, with models sometimes achieving such high accuracy scores that the benchmark becomes ineffective—a phenomenon increasingly observed in genomics as AI tools mature.

Data Contamination: Public benchmarks frequently leak into training data, enabling memorization rather than true generalization. Retrieval-based audits have found over 45% overlap on question-answering benchmarks, with similar issues likely in genomic datasets [11].

Fragmented Evaluation Ecosystems: Nearly all benchmarks are static, with performance gains increasingly reflecting task memorization rather than capability advancement. The lack of "liveness"—continuous inclusion of fresh, unpublished items—renders metrics stale snapshots rather than dynamic assessments [11].

Domain-Specific Challenges in Evolutionary Genomics

Evolutionary genomics presents unique benchmarking complications that extend these general AI challenges:

Phylogenetic Diversity Considerations: Effective benchmarking must account for vast phylogenetic diversity, from closely related species to distant taxa. The varKoder project addressed this by creating datasets spanning different taxonomic ranks and phylogenetic depths, from closely related populations to all taxa represented in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive [12].

Data Integration Complexities: Genomic analyses increasingly combine multiple data types (sequence data, structural variations, epigenetic markers), creating integration challenges for benchmark design. Over 50 AI-driven analytical tools now combine genomic data with clinical inputs, requiring sophisticated multi-modal benchmarking approaches [10].

Computational Resource Disparities: The exponential growth in AI compute demand particularly affects genomics, where projects can require weeks of GPU computation for a single prediction pipeline [13]. This creates resource barriers that limit who can participate in benchmark development and validation.

Table 1: Key Benchmarking Challenges in Evolutionary Genomics AI

| Challenge Category | Specific Manifestations in Genomics | Impact on Research Progress |

|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Standardization | Inconsistent annotation practices across genomic databases; variable sequencing quality | Prevents direct comparison of tools across studies; obscures true performance differences |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Overrepresentation of model organisms; underrepresentation of microbial and non-model eukaryotes | Limits generalizability of AI predictions across the tree of life |

| Computational Requirements | High GPU/TPU demands for training and inference; expensive storage of large genomic datasets | Creates resource barriers that favor well-funded entities; reduces reproducibility |

| Evaluation Metrics | Overreliance on limited metrics like accuracy without biological context | Fails to capture performance characteristics that matter for real research applications |

| Temporal Relevance | Rapid advances in sequencing technologies outpacing benchmark updates | Makes benchmarks obsolete before they can drive meaningful comparisons |

Community-Driven Solutions and Benchmarking Frameworks

Emerging Benchmarking Initiatives

In response to these challenges, several community-driven initiatives are developing more robust benchmarking frameworks specifically designed for biological AI applications:

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) has launched a benchmarking suite that addresses recognized community needs for resources that are "more usable, transparent, and biologically relevant" [6]. This initiative emerged from workshops convening machine learning and computational biology experts from 42 institutions who concluded that AI model measurement in biology has been plagued by "reproduction challenges, biases, and a fragmented ecosystem of publicly available resources" [6]. Their approach includes:

- Standardized Evaluation Pipelines: Reducing setup time from approximately three weeks to three hours for common evaluation tasks.

- Multiple Assessment Metrics: Moving beyond single metrics to comprehensive evaluation across six tasks: cell clustering, cell type classification, cross-species integration, perturbation expression prediction, sequential ordering assessment, and cross-species disease label transfer.

- Community Governance: A "living, evolving product where individual researchers, research teams, and industry partners can propose new tasks, contribute evaluation data, and share models" [6].

Concurrently, the PeerBench framework proposes a "community-governed, proctored evaluation blueprint" that incorporates sealed execution, item banking with rolling renewal, and delayed transparency to prevent gaming of benchmarks [11]. This approach addresses critical flaws in current benchmarking, where "model creators can highlight performance on favorable task subsets, creating an illusion of across-the-board prowess" [11].

In genomic-specific domains, researchers are developing curated benchmark datasets to enable more reliable tool comparisons. One significant example is the curated benchmark dataset for molecular identification based on genome skimming, which includes four datasets designed for comparing molecular identification tools using low-coverage genomes [12]. This resource addresses the critical problem that "the success of a given method may be dataset-dependent" by providing standardized datasets that span phylogenetic diversity [12].

Similarly, comprehensive benchmarking efforts for bioinformatics tools are emerging for specific genomic tasks. For example, a recent study benchmarked 11 pipelines for hybrid de novo assembly of human and non-human whole-genome sequencing data, assessing software performance using QUAST, BUSCO, and Merqury metrics alongside computational cost analyses [14]. Such efforts provide tangible frameworks for evaluating AI tools in specific genomic contexts.

Table 2: Community-Driven Benchmarking Initiatives Relevant to Evolutionary Genomics

| Initiative | Primary Focus | Key Features | Relevance to Evolutionary Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CZI Benchmarking Suite [6] | Single-cell transcriptomics and virtual cell models | Standardized toolkit, multiple programming interfaces, community contribution | Provides models for cross-species integration and evolutionary cell biology |

| PeerBench [11] | General AI evaluation with focus on security | Sealed execution, item banking, delayed transparency, community governance | Prevents benchmark gaming in phylogenetic inference and genomic predictions |

| varKoder Datasets [12] | Molecular identification via genome skimming | Four curated datasets spanning taxonomic ranks, raw sequencing data, image representations | Enables testing of hierarchical classification from species to family level |

| Hybrid Assembly Benchmark [14] | De novo genome assembly | 11 pipelines assessed via multiple metrics, computational cost analysis | Provides standardized assessment for evolutionary genomics assembly workflows |

Comparative Analysis of AI Benchmarking Approaches

Quantitative Comparison of Benchmarking Methodologies

The evolution of benchmarking approaches has produced distinct methodologies with varying strengths and limitations for genomic applications. The following table summarizes key characteristics of predominant benchmarking frameworks based on current implementations:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of AI Benchmarking Approaches in Genomic Applications

| Benchmarking Approach | Technical Implementation | Data Contamination Controls | Evolutionary Genomics Applicability | Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Benchmark Datasets [15] | Fixed test sets with predefined metrics | Vulnerable to contamination; 45% overlap reported in some QA benchmarks | Limited for rapidly evolving methods; suitable for established tasks | Low to moderate; single evaluation sufficient |

| Dynamic/Live Benchmarks [11] | Rolling test sets with periodic updates | Improved security through item renewal | Better suited to adapting to new genomic discoveries | High; requires continuous maintenance and updates |

| Community-Governed Platforms [6] | Standardized interfaces with contributor ecosystem | Moderate protection through diversity of contributors | Excellent for incorporating diverse evolutionary perspectives | Variable; distributed across community |

| Proctored/Sealed Evaluation [11] | Controlled execution environments | High security through execution isolation | Strong for clinical and regulatory applications | Very high; requires specialized infrastructure |

| Multi-Metric Assessment [6] | Simultaneous evaluation across multiple dimensions | Reduces cherry-picking of favorable metrics | Essential for comprehensive genomic tool assessment | Moderate; increased computational load |

Performance Metrics Across Genomic AI Tasks

Recent benchmarking efforts reveal significant performance variations across different genomic tasks, highlighting the importance of task-specific evaluation:

Molecular Identification: The varKoder tool and associated benchmarks demonstrate that methods like Skmer, iDeLUCS, and conventional barcodes assembled with PhyloHerb show variable performance across different phylogenetic depths, with performance decreasing at finer taxonomic resolutions [12].

Genome Assembly: Benchmarking of 11 hybrid de novo assembly pipelines revealed that Flye outperformed other assemblers, particularly with Ratatosk error-corrected long-reads, while polishing schemes (especially two rounds of Racon and Pilon) significantly improved assembly accuracy and continuity [14].

Variant Interpretation: AI tools for variant classification have demonstrated 20-30 unit improvements in error detection in machine learning implementations, though performance varies significantly across variant types and genomic contexts [10].

The field has observed that nearly 95% of genomics laboratories have upgraded their systems to include neural network models, resulting in improvements of at least 20 numerical units in gene prediction accuracy, though these gains are inconsistently distributed across different biological applications [10].

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Genomic AI Benchmarking

Comprehensive Benchmarking Workflow

To address the benchmarking bottleneck in evolutionary genomics, researchers must implement standardized experimental protocols that ensure fair comparisons across AI tools. The following workflow synthesizes best practices from community-driven initiatives:

AI Benchmarking Workflow for Genomics

Detailed Methodological Specifications

Based on successful implementations in genomic benchmarking [12] [14], the following protocols provide a framework for rigorous AI evaluation:

Dataset Curation Protocol

Taxonomic Stratification: Curate datasets that represent varying phylogenetic depths, from closely related populations (e.g., 0.6 Myr divergence in Stigmaphyllon plants) to distant taxa (e.g., 34.1 Myr divergence) [12]. This enables testing hierarchical classification from species to family level.

Data Quality Control: Implement rigorous quality filters including sequence length distribution analysis, GC content verification, and contamination screening using tools like FastQC and Kraken. The Malpighiales dataset exemplifies this approach with expert-curated samples from herbarium specimens and silica-dried field collections [12].

Benchmark Splitting: Partition data into training/validation/test sets using phylogenetic holdouts rather than random splitting to prevent data leakage and better simulate real-world application scenarios.

Evaluation Metric Selection

Multi-Dimensional Assessment: Combine performance metrics (accuracy, F1-score, AUROC), computational metrics (memory usage, runtime, scalability), and biological metrics (evolutionary concordance, functional conservation).

Statistical Robustness: Employ appropriate statistical tests for performance comparisons, including confidence interval estimation and significance testing with multiple comparison corrections.

Reference Standard Establishment: Where possible, incorporate expert-curated gold standard datasets with known ground truth, such as the Stigmaphyllon clade with its extensively revised taxonomy [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The Genomics Researcher's Benchmarking Toolkit

Implementing robust AI benchmarking in evolutionary genomics requires specific computational reagents and frameworks. The following table details essential components for establishing a comprehensive benchmarking pipeline:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic AI Benchmarking

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | varKoder Malpighiales dataset [12], OrthoBench [12], Hybrid assembly benchmarks [14] | Provides standardized data for tool comparison | Requires phylogenetic diversity and quality verification |

| Evaluation Metrics | QUAST, BUSCO, Merqury [14], CZ-Benchmarks [6] | Quantifies performance across multiple dimensions | Must align with biological relevance and research goals |

| Compute Infrastructure | GPU clusters (NVIDIA), Cloud platforms (AWS, Google Cloud) [13], High-performance computing systems [10] | Enables execution of computationally intensive AI models | Significant resource requirements; cost considerations |

| Workflow Management | Nextflow pipelines [14], Snakemake, Custom Python scripts | Ensures reproducibility and parallelization | Requires expertise in pipeline development and optimization |

| Community Platforms | PeerBench [11], CZI Benchmarking Suite [6], Open LLM Leaderboard [15] | Facilitates transparent result sharing and verification | Dependent on community adoption and participation |

Implementation Framework

Successful implementation of these reagents requires careful planning and execution:

Staged Deployment: Begin with established benchmark datasets before progressing to custom curation. The varKoder dataset provides an excellent starting point with its comprehensive taxonomic coverage [12].

Computational Resource Allocation: Secure appropriate computational resources, recognizing that AI-driven genomic projects can require "weeks of GPU computation for each prediction pipeline" [13].

Continuous Integration: Embed benchmarking into development workflows using tools like the cz-benchmarks Python package, which enables "benchmarking at any development stage, including intermediate checkpoints" [6].

The benchmarking bottleneck in evolutionary genomics represents a critical challenge that demands immediate and coordinated action from the research community. Without significant improvements in how we evaluate AI tools, the field risks squandering the tremendous potential of artificial intelligence to advance our understanding of genomic evolution and accelerate therapeutic development.

The path forward requires embracing community-driven benchmarking initiatives that prioritize biological relevance over leaderboard positioning, implement robust safeguards against data contamination and gaming, and provide multidimensional assessment across performance, computational efficiency, and biological utility. Frameworks like the CZI Benchmarking Suite [6] and PeerBench [11] offer promising blueprints for this evolution, emphasizing transparency, reproducibility, and continuous improvement.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the imperative is clear: adopt standardized benchmarking protocols, participate in community evaluation efforts, and prioritize rigorous assessment alongside model development. Only through such concerted efforts can we overcome the benchmarking bottleneck and realize the full potential of AI to transform evolutionary genomics research.

The Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) has, since its inception in 1994, served as the definitive benchmarking platform for evaluating progress in one of biology's most challenging problems: predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence [16] [17]. This community-wide experiment operates as a rigorous blind trial, where predictors are given sequences for proteins whose structures have been experimentally determined but not yet publicly released [16]. By providing objective, head-to-head comparison of methodologies, CASP has systematically dismantled the technical barriers that once seemed insurmountable, transforming protein folding from a grand challenge into a tractable problem. The journey of CASP, marked by incremental improvements and punctuated by revolutionary breakthroughs, offers a masterclass in how standardized, competitive benchmarking can accelerate an entire scientific field. This guide will objectively compare the performance of the key methods that have defined this evolution, with a particular focus on the transformative impact of deep learning as evaluated through the CASP framework.

The CASP Experimental Protocol: A Blueprint for Rigorous Evaluation

The core of CASP's success lies in its meticulously designed experimental protocol, which ensures fair and comparable assessment of diverse methodologies.

The Blind Prediction Cycle

CASP functions on a biennial cycle. Organizers collect protein sequences from collaborating experimentalists just before the structures are due to be released in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [18]. Participants then submit their predicted 3D models based solely on these sequences [16] [18]. This blind format is crucial for preventing overfitting and providing a true test of predictive capability.

Key Assessment Metrics

Predictions are evaluated by independent assessors using standardized metrics that quantitatively measure accuracy [18]:

- GDTTS (Global Distance Test Total Score): A primary metric ranging from 0-100, measuring the average percentage of amino acids superimposed under a defined distance cutoff. A higher GDTTS indicates greater similarity to the experimental structure [19].

- GDTHA (Global Distance Test High Accuracy): A more stringent version of GDTTS with tighter distance thresholds, used to evaluate high-accuracy models [18].

- Z-score: A statistical measure indicating how many standard deviations a group's performance is above the mean of all groups for a given target [16].

Evolving Challenge Categories

As the field progressed, CASP introduced specialized categories to address new frontiers:

- Monomer Prediction: The original core challenge of predicting single-chain proteins [18].

- Assembly Modeling: Assessing the ability to model multimolecular protein complexes (quaternary structure), introduced due to growing interest in biological interactions [19].

- Refinement: Testing methods for improving available models towards greater accuracy [19].

- Data-Assisted Modeling: Evaluating hybrid approaches that integrate low-resolution experimental data [19].

Table 1: Key CASP Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDT_TS | Percentage of Cα atoms under defined distance cutbacks (1, 2, 4, 8 Å) | 0-100 scale; higher values indicate better model quality | General accuracy assessment for backbone structure |

| GDT_HA | More stringent distance thresholds than GDT_TS | Measures high-accuracy modeling capability | Evaluating near-experimental quality models |

| Z-score | Standard deviations from mean performance | Allows cross-target comparison; positive values indicate above-average performance | Ranking participants across multiple targets |

| TM-score | Structure similarity measure less sensitive to local errors | 0-1 scale; >0.5 indicates same fold, >0.8 high accuracy | Comparing global fold topology |

| ICS (Interface Contact Score) | Accuracy of residue-residue contacts at interfaces | F1 score combining precision and recall | Specifically for protein complex assembly assessment |

Historical Performance Evolution Through CASP

The quantitative data collected over 15 CASP experiments provides an unambiguous record of methodological progress, highlighting particularly dramatic improvements with the introduction of deep learning.

The Pre-Deep Learning Era (CASP1-12)

Early CASP experiments revealed the profound difficulty of the protein folding problem. In CASP11 (2014), the top-performing team led by David Baker achieved a maximum Z-score of approximately 75, while most participants scored below 25 [16]. Template-based modeling and physics-based methods showed steady but incremental progress during this period [19].

The Deep Learning Revolution (CASP13-15)

The introduction of deep learning marked a watershed moment in protein structure prediction:

- CASP13 (2018): DeepMind's original AlphaFold (now called AlphaFold1) debuted with a remarkable accuracy of approximately 120 Z-score, substantially outperforming the 2014 leader at 80 Z-score [16]. This represented the first major leap from traditional methods.

- CASP14 (2020): AlphaFold2 achieved a staggering ~240 Z-score, nearly doubling its previous performance and far surpassing all other teams, which remained around 90 Z-score [16]. The CASP14 assessment declared that AlphaFold2 produced models competitive with experimental accuracy (GDT_TS>90) for approximately two-thirds of targets [19].

The Post-AlphaFold Landscape (CASP15-16)

Recent CASP experiments have evaluated refinements and extensions of the deep learning paradigm:

- CASP15 (2022): Showed enormous progress in modeling multimolecular protein complexes, with the accuracy of models almost doubling in terms of Interface Contact Score compared to CASP14 [19].

- CASP16 (2024): Confirmed that single-domain protein fold prediction is largely solved, with no target folds incorrectly predicted across all evaluation units [18]. The best-performing groups consistently utilized AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, with the latter showing noticeable advantages in confidence estimation and model selection [18].

Table 2: Performance Evolution of Key Methods Across CASP Experiments

| Method | CASP Edition | Key Performance Metric | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker Group (2014) | CASP11 (2014) | Z-score ~75 [16] | Leading pre-deep learning methodology | Limited accuracy for difficult targets |

| AlphaFold1 | CASP13 (2018) | Z-score ~120 [16] | First major DL breakthrough; used CNNs and distance maps | Limited to distance-based constraints |

| AlphaFold2 | CASP14 (2020) | Z-score ~240 [16] | Transformer architecture (Evoformer); direct coordinate prediction [16] | Computationally intensive; less accurate for complexes |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | CASP15 (2022) | Significant improvement in complex modeling [20] | Specialized for protein complexes | Lower accuracy than AF2 for monomers |

| DeepSCFold (2025) | CASP15 Benchmark | 11.6% TM-score improvement over AF-Multimer [20] | Uses sequence-derived structure complementarity | New method, less extensively validated |

| AlphaFold3 | CASP16 (2024) | Outperformed AF2 in confidence estimation [18] | Models proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands [18] | Limited accessibility during CASP16 |

Figure 1: Evolution of Protein Structure Prediction Performance Through CASP Benchmarks

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Protocols of Leading Approaches

The progression of top-performing methods in CASP reveals distinct methodological evolution, from physical modeling to deep learning architectures specifically refined through competition.

Traditional Template-Based Modeling (Pre-2018)

Before the deep learning revolution, the most successful approaches combined various techniques:

- Protocol: Identification of structural templates through sequence homology, followed by alignment, model building, and refinement [19].

- Key Features: Reliance on evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and physical energy functions [19].

- CASP Performance: Steady but incremental progress, with GDT_TS improvements of approximately 1-2 points per CASP edition for template-based modeling [19].

Deep Learning Generation 1: AlphaFold1

DeepMind's first CASP entry established a new paradigm by applying convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to protein structure prediction [16]:

- Experimental Protocol:

- Generated distance matrices between amino acid residues using co-evolutionary data from MSAs

- Transformed 3D structural information into 2D distance maps

- Applied CNNs to analyze these maps and predict spatial relationships [16]

- Used gradient descent for optimization and structure generation

- Key Innovation: Framing structure prediction as an image analysis problem using distance geometry.

Deep Learning Generation 2: AlphaFold2

The revolutionary AlphaFold2 architecture that dominated CASP14 introduced several fundamental advances [16]:

- Experimental Protocol:

- Input Processing: Direct use of sequence information including MSAs and pair representation, moving beyond predetermined distance information [16]

- Evoformer Module: A novel transformer-based architecture that replaced CNNs, enabling efficient processing of sequence relationships and residue-residue interactions [16]

- Structure Module: Direct prediction of atomic coordinates rather than inter-residue distances

- End-to-End Training: The entire system was trained jointly rather than as separate components

- Key Innovation: The attention mechanism in the Evoformer allowed the model to learn complex long-range dependencies directly from sequences.

Specialized Complex Prediction: DeepSCFold (2025)

Recent methods like DeepSCFold exemplify how CASP drives specialization for remaining challenges, particularly protein complex prediction [20]:

- Experimental Protocol:

- Input Generation: Creates monomeric multiple sequence alignments from diverse databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, UniProt, Metaclust, etc.) [20]

- Structural Similarity Prediction: Uses deep learning to predict protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) from sequence alone

- Interaction Probability: Predicts interaction probability (pIA-score) between sequences from distinct subunit MSAs

- Paired MSA Construction: Systematically concatenates monomeric homologs using interaction probabilities and multi-source biological information

- Complex Prediction: Feeds paired MSAs into AlphaFold-Multimer for structure prediction, with model selection via quality assessment method DeepUMQA-X [20]

- Key Innovation: Leverages sequence-derived structure complementarity rather than relying solely on co-evolutionary signals, particularly beneficial for complexes lacking clear co-evolution (e.g., antibody-antigen systems) [20].

Figure 2: Evolution of Methodological Approaches in Protein Structure Prediction

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Protein Structure Prediction

The advancement of protein structure prediction methodologies has depended on a ecosystem of computational tools and databases that serve as essential research reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Structure Prediction

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Workflow | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | UniRef30/90, UniProt, Metaclust, BFD, MGnify, ColabFold DB [20] | Provides evolutionary information via homologous sequences | Varying levels of redundancy reduction; metagenomic data critical for difficult targets |

| MSA Construction Tools | HHblits, Jackhammer, MMseqs2 [20] | Identifies homologous sequences and builds multiple sequence alignments | Efficient searching of large sequence databases; different sensitivity/speed tradeoffs |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | AlphaFold2, AlphaFold3, AlphaFold-Multimer, ESMFold [18] | Core structure prediction engines | Varying architecture (Evoformer, etc.); specialized for monomers vs. complexes |

| Quality Assessment Tools | DeepUMQA-X, Model Quality Assessment Programs [20] | Selects best models from predicted ensembles | Predicts model accuracy without reference structures; crucial for blind prediction |

| Specialized Complex Prediction | DeepSCFold, MULTICOM3, DiffPALM, ESMPair [20] | Enhances protein complex structure prediction | Constructs paired MSAs; captures inter-chain interactions |

| Evaluation Metrics | GDTTS/GDTHA, TM-score, ICS, Z-score [19] [18] | Quantifies prediction accuracy against experimental structures | Standardized benchmarks for method comparison; different sensitivities to various error types |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite extraordinary progress, CASP continues to identify persistent challenges that guide future methodological development.

Remaining Technical Hurdles

- Complex Assemblies: While monomer prediction is largely solved, accurately modeling large, dynamic complexes remains difficult [18] [21].

- Conformational Flexibility: Predicting structures for proteins with multiple biologically relevant conformations or significant flexibility [18].

- Model Selection: Ranking self-generated models remains a persistent weakness across most groups, highlighting a critical area for development [18].

- Irregular Structures: Challenges in accurately modeling truncated sequences and irregular secondary structures [18].

Expanding Beyond Protein-Only Structures

The field is increasingly focused on modeling complexes involving diverse biomolecules:

- Protein-Nucleic Acid Complexes: Accurate prediction of protein-DNA and protein-RNA interactions [18].

- Small Molecule Ligands: Modeling interactions with drugs, metabolites, and cofactors [21].

- Multi-Scale Modeling: Integrating structural information with cellular context and dynamics.

The Benchmarking Bottleneck

The rapid progress in biological AI has highlighted systemic challenges in evaluation methodologies, with researchers often spending valuable time building custom evaluation pipelines rather than focusing on methodological improvements [6]. Initiatives like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's benchmarking suite aim to address this by providing standardized, community-driven evaluation resources that enable robust comparison across studies [6].

The trajectory of protein structure prediction, as meticulously documented through CASP experiments, provides a powerful template for how community-driven benchmarking can accelerate scientific progress. The transition from incremental improvements to revolutionary leaps—particularly with the introduction of deep learning—demonstrates how objective, head-to-head comparison in blind trials drives innovation by clearly identifying superior methodologies. CASP's evolution from evaluating basic folding capability to assessing complex assembly prediction illustrates how benchmarking must continuously adapt to address new frontiers.

The lessons from CASP extend far beyond protein folding, offering a blueprint for benchmarking AI across evolutionary genomics and biological research. The success of this three-decade experiment underscores the importance of standardized metrics, blind evaluation, community engagement, and adaptive challenge design. As biological AI tackles increasingly complex problems—from cellular modeling to whole-organism simulation—the CASP model of rigorous, community-wide assessment will remain essential for separating genuine progress from hyperbolic claims and for ensuring that AI methodologies deliver meaningful biological insights.

The field of evolutionary genomics research is increasingly relying on artificial intelligence to model complex biological systems. However, the absence of standardized evaluation frameworks has hampered progress and reproducibility. Two major community initiatives have emerged to address this critical bottleneck: Arc Institute's Virtual Cell Challenge and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's (CZI) Benchmarking Suite. These complementary efforts aim to establish rigorous, community-driven standards for assessing AI predictions in biology, enabling researchers to compare model performance objectively and accelerate scientific discovery in evolutionary genomics and drug development.

Arc Institute's Virtual Cell Challenge

The Arc Institute's Virtual Cell Challenge, launched in June 2025, is a public competition designed to catalyze progress in AI modeling of cellular behavior [22]. Structured as a recurring benchmark competition, it provides a structured evaluation framework, purpose-built datasets, and a venue for accelerating model development in predicting cellular responses to genetic perturbations [23]. The initiative aims to emulate the success of CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) in transforming protein structure prediction over 25 years, ultimately enabling breakthroughs like AlphaFold [22].

Key Specifications:

- Primary Goal: Accelerate progress in AI modeling of biology by creating high-quality datasets and standardized benchmarks for virtual cell modeling [22]

- Core Task: Predict effects of single gene perturbations on cellular gene expression profiles [22]

- Dataset: 300,000 H1 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) with 300 genetic perturbations [22]

- Evaluation Framework: Three specialized metrics assessing differential expression recovery, perturbation discrimination, and global expression accuracy [24]

- Prize Structure: $100,000 grand prize, with additional prizes of $50,000 and $25,000 [22]

CZI's Benchmarking Suite

Launched in October 2025, CZI's benchmarking suite addresses the systemic bottleneck in biological AI evaluation through a comprehensive, community-driven resource [6]. This initiative provides standardized tools for robust and broad task-based benchmarking to drive virtual cell model development, enabling researchers to spend less time evaluating models and more time improving them to solve real biological problems [6].

Key Components:

- cz-benchmarks: An open-source Python package for embedding evaluations directly into training or inference code [6]

- VCP CLI: A programmatic interface to interact with core resources on the platform [25]

- The Platform: An interactive, no-code, web-based interface to explore and compare benchmarking results [6]

Direct Comparison of Initiatives

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Virtual Cell Benchmarking Initiatives

| Feature | Arc Institute Virtual Cell Challenge | CZI Benchmarking Suite |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Format | Time-bound competition with prizes | Ongoing platform and tools |

| Launch Date | June 2025 [22] | October 2025 [6] |

| Core Focus | Predicting genetic perturbation effects [22] | Multiple benchmarking tasks for virtual cell models [6] |

| Dataset Specificity | Single, high-quality dataset of 300,000 H1 hESCs [24] | Multiple datasets from various contributors [6] |

| Evaluation Metrics | DES, PDS, MAE [24] | Six initial tasks with multiple metrics each [6] |

| Target Users | AI researchers, computational biologists [22] | Broader audience including non-computational biologists [6] |

| Access Method | Competition registration at virtualcellchallenge.org [22] | Open access platform with no-code interface [6] |

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Virtual Cell Challenge Dataset Generation

The Arc Institute team made careful experimental decisions to create a high-quality benchmark dataset for the Virtual Cell Challenge [24]:

Perturbation Modality: The team employed dual-guide CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for targeted knockdown, using a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to a KRAB transcriptional repressor [24]. This approach silences gene expression by targeting promoter regions without cutting the genome, leaving the genomic sequence intact while sharply reducing mRNA levels. The dual-guide design ensures strong and consistent knockdown across target genes compared to single-guide designs.

Profiling Chemistry: The team selected 10x Genomics Flex chemistry, a fixation-based, gene-targeted probe-based method for single-cell gene expression profiling [24]. This chemistry enables more uniform capture, better transcript preservation, removal of unwanted transcripts, capture of less abundant mRNAs, and the ability to scale deeply without sacrificing per-cell quality.

Cell Type Selection: H1 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) were deliberately chosen as the cellular model to test model generalization [24]. Unlike immortalized cell lines that dominate existing Perturb-seq datasets, the pluripotent H1 ESCs represent a true distributional shift relative to most public pretraining data, preventing models from succeeding merely by memorizing response patterns seen in other cell lines.

Target Gene Selection: The team constructed a panel of 300 target genes spanning a wide spectrum of perturbation effects [24]. Using ContrastiveVI, a representation learning method, they clustered perturbation responses in latent space to ensure the final list captured diverse modes of response, not just genes that triggered large numbers of differentially expressed genes.

Table 2: Virtual Cell Challenge Dataset Quality Metrics

| Quality Metric | Value (median/mean) | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cells per perturbation | ~1,000 | Robust effect size estimates |

| UMIs per cell | >50,000 | Captures subtle transcriptional shifts impossible at shallow depth |

| Guides detection | 63% of cells with both correct guides detected | Extremely low assignment errors |

| Knock-down efficacy | 83% of cells with >80% knockdown | Confirms perturbations, not noise |

CZI Benchmarking Suite Task Design

CZI's benchmarking suite addresses recognized community needs for resources that are more usable, transparent, and biologically relevant [6]. The initial release includes six tasks widely used by the biology community for single-cell analysis:

- Cell clustering: Grouping cells based on expression similarity

- Cell type classification: Identifying and categorizing cell types

- Cross-species integration: Aligning data across different organisms

- Perturbation expression prediction: Forecasting gene expression changes after perturbations

- Sequential ordering assessment: Analyzing progression through biological processes

- Cross-species disease label transfer: Applying disease annotations across species

Each task is paired with multiple metrics for a thorough view of performance, avoiding the limitations of single-metric evaluations that can lead to cherry-picked results [6].

Evaluation Metrics Framework

Virtual Cell Challenge Metrics:

The Virtual Cell Challenge employs three specialized metrics that directly map to practical use cases in perturbation biology [24]:

Differential Expression Score (DES): Evaluates whether models recover the correct set of differentially expressed genes after perturbation, calculated as the intersection between predicted and true DE genes divided by the total number of true DE genes.

Perturbation Discrimination Score (PDS): Measures whether models assign the correct effect to the correct perturbation by computing L1 distances between predicted perturbation deltas and all true deltas, with perfect ranking yielding a score of 1.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Assesses global expression accuracy across all genes, providing a comprehensive measure of prediction fidelity.

Diagram 1: Virtual Cell Challenge Metrics Framework

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Virtual Cell Modeling

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Initiative |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi with dual-guideRNA | Molecular Tool | Enables strong, consistent gene knockdown without DNA cutting [24] | Arc Institute |

| H1 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) | Biological Model | Pluripotent cell type testing model generalization ability [24] | Arc Institute |

| 10x Genomics Flex chemistry | Profiling Technology | Enables high-resolution transcriptomic profiling with minimal technical noise [24] | Arc Institute |

| cz-benchmarks Python package | Computational Tool | Standardized benchmarking for embedding evaluations into training workflows [6] | CZI |

| Virtual Cells Platform (VCP) | Platform Infrastructure | No-code interface for model exploration and comparison [25] | CZI |

| TranscriptFormer | AI Model | Virtual cell model used as foundation for training reasoning models [26] | CZI |

| rBio | AI Reasoning Model | LLM-based tool that reasons about biology using virtual cell knowledge [26] | CZI |

Diagram 2: Perturb-seq Experimental Workflow for Benchmark Generation

Impact on Evolutionary Genomics Research

Both initiatives present significant implications for evolutionary genomics research by establishing foundational evaluation standards. The Arc Institute's Challenge provides a rigorous framework for assessing how well models can predict evolutionary conserved genetic perturbation responses across species [24]. By using H1 embryonic stem cells, which represent a primitive developmental state, the dataset offers insights into fundamental regulatory mechanisms that have been evolutionarily conserved [24].

CZI's multi-task benchmarking approach enables researchers to evaluate model performance on cross-species integration and label transfer tasks directly relevant to evolutionary studies [6]. The platform's design as a living, community-driven resource ensures it can evolve to incorporate new evolutionary genomics questions and datasets as the field advances [6].

The collaboration between CZI and NVIDIA further accelerates these efforts by scaling biological data processing to petabytes of data spanning billions of cellular observations [27]. This infrastructure supports the development of next-generation models that can unlock new insights about evolutionary biology through multi-modal, multi-scale modeling that reflects the complex, interconnected nature of cellular evolution [28].

Future Directions

Both initiatives are designed as evolving resources. Arc Institute plans to repeat the Virtual Cell Challenge annually with new single-cell transcriptomics datasets comprising different cell types and increasingly complex biological challenges [22]. This iterative approach will continuously push the boundaries of what virtual cell models can predict, potentially expanding to include evolutionary comparisons across species.

CZI will expand its benchmarking suite with additional community-defined assets, including held-out evaluation datasets, and develop tasks and metrics for other biological domains including imaging and genetic variant effect prediction [6]. This expansion will create more comprehensive evaluation frameworks for studying evolutionary processes at multiple biological scales.

The emergence of reasoning models like rBio, trained on virtual cell simulations, points toward a future where researchers can interact with cellular models through natural language to ask complex questions about evolutionary mechanisms [26]. This democratization of virtual cell technology could empower more researchers to investigate evolutionary genomics questions without requiring deep computational expertise.

Core Methodologies and Applications in Genomic AI Benchmarking

Foundation models, pre-trained on vast datasets using self-supervised learning, are revolutionizing genomic research by decoding complex patterns and regulatory mechanisms within DNA sequences. These models learn fundamental biological principles directly from nucleotide sequences, enabling researchers to predict variant effects, annotate functional elements, and generate novel biological sequences with unprecedented accuracy. The emergence of architectures like Evo 2 and scGPT represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, offering powerful tools for evolutionary genomics research and therapeutic development.

This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of leading DNA foundation models, focusing on their architectural innovations, performance characteristics, and practical applications. We situate this analysis within the critical context of benchmarking AI predictions in evolutionary genomics, examining how these models generalize across species, handle diverse biological tasks, and capture evolutionary constraints. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the relative strengths and limitations of these tools is essential for selecting appropriate methodologies and interpreting results with biological fidelity.

Model Architectures and Technical Specifications

DNA foundation models employ diverse architectural approaches to process genomic sequences, each with distinct advantages for handling the complex language of biology.

Architectural Approaches

Evo 2 utilizes the StripedHyena 2 architecture, a multi-hybrid design that combines convolutional operators, linear attention, and state-space models to efficiently process long sequences [29] [30]. This architecture employs three specialized operators: Hyena-SE for short explicit patterns using convolutional kernels (length LSE=7), Hyena-MR for medium-range dependencies (LMR=128), and Hyena-LI for long implicit dependencies through recurrent formulation [29]. This combination enables Evo 2 to capture biological patterns from single nucleotides to megabase-scale contexts, making it particularly suited for analyzing long-range genomic interactions like enhancer-promoter relationships [31] [29].

scGPT employs a transformer-based encoder architecture specifically designed for single-cell multi-omics data [32]. Unlike nucleotide-level models, scGPT processes gene expression values using lookup table embeddings for gene symbols, value embeddings for expression levels, and employs a masked gene modeling pretraining objective [32]. This architecture enables the model to learn the complex relationships between genes and cellular states, making it particularly valuable for predicting cellular responses to perturbations and identifying disease-associated genetic programs.

DNABERT-2 adapts the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) architecture with Attention with Linear Biases (ALiBi) for genomic sequences [33]. Pretrained using masked language modeling on genomes from 135 species, it employs Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) for tokenization, which builds vocabulary iteratively without assumptions about fixed genomic words or grammars [33].

Nucleotide Transformer (NT-v2) also uses a BERT-style architecture but incorporates rotary embeddings and Swish activation without bias [33]. It utilizes 6-mer tokenization (sliding windows of 6 nucleotides) and was pretrained on genomes from 850 species, providing broad evolutionary coverage [33].

HyenaDNA implements a decoder-based architecture that eschews attention mechanisms in favor of Hyena operators, which integrate long convolutions with implicit parameterization and data-controlled gating [33]. This design enables processing of extremely long sequences (up to 1 million nucleotides) with fewer parameters than transformer-based approaches [33].

Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical Specifications of DNA Foundation Models

| Model | Architecture | Parameters | Context Length | Tokenization | Training Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evo 2 | StripedHyena 2 (Multi-hybrid) | 1B, 7B, 40B [30] | Up to 1M nucleotides [31] | Nucleotide-level [29] | 9.3T nucleotides from diverse eukaryotic/prokaryotic genomes [31] |

| scGPT | Transformer Encoder | 50M [32] | 1,200 HVGs [32] | Gene-level | 33M cells [32] |

| DNABERT-2 | BERT with ALiBi | ~117M [33] | No hard limit (quadratic scaling) [33] | Byte Pair Encoding | Genomes from 135 species [33] |

| NT-v2 | BERT with Rotary Embeddings | ~500M [33] | 12,000 nucleotides [33] | 6-mer sliding window | Genomes from 850 species [33] |

| HyenaDNA | Decoder with Hyena Operators | ~30M [33] | 1M nucleotides [33] | Nucleotide-level | Human reference genome [33] |

Performance Benchmarking in Evolutionary Genomics

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating DNA foundation models' performance across diverse genomic tasks and evolutionary contexts. Recent studies have established standardized frameworks to assess these models' capabilities and limitations.

Benchmarking Methodology

Comprehensive benchmarking requires evaluating models across multiple dimensions: (1) task diversity - including variant effect prediction, functional element detection, and epigenetic modification prediction; (2) evolutionary scope - performance across different species and phylogenetic distances; and (3) technical efficiency - computational requirements and scalability [33]. Unbiased evaluation typically employs zero-shot embedding analysis, where pre-trained model weights remain frozen while embeddings are extracted and evaluated using simple classifiers, eliminating confounding factors introduced by fine-tuning [33].

For evolutionary genomics, benchmarking datasets should encompass sequences from diverse species to assess cross-species generalization. The mean token embedding approach has demonstrated consistent performance improvements over sentence-level summary tokens, with average AUC improvements ranging from 4.3% to 9.7% across different DNA foundation models [33]. This method better captures sequence characteristics relevant to evolutionary analysis.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking Across Genomic Tasks

| Model | Variant Effect Prediction (AUROC) | Epigenetic Modification Detection (AUROC) | Cross-Species Generalization | Long-Range Dependency Capture | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evo 2 | 0.89-0.94 [34] | 0.87-0.92 [29] | High (trained on diverse species) [31] | Excellent (1M context) [29] | Moderate (requires significant GPU) [30] |

| scGPT | 0.82-0.88 [32] | 0.79-0.85 [32] | Moderate (cell-type focused) [32] | Limited (gene-level context) [32] | High (50M parameters) [32] |

| DNABERT-2 | 0.86-0.91 [33] | 0.83-0.89 [33] | High (135 species) [33] | Moderate (quadratic scaling) [33] | Moderate (117M parameters) [33] |

| NT-v2 | 0.84-0.90 [33] | 0.88-0.93 [33] | Excellent (850 species) [33] | Limited (12K context) [33] | Low (500M parameters) [33] |

| HyenaDNA | 0.81-0.87 [33] | 0.80-0.86 [33] | Limited (human-focused) [33] | Excellent (1M context) [33] | High (30M parameters) [33] |

In specialized applications like rare disease diagnosis, models like popEVE (an extension of the EVE evolutionary model) demonstrate exceptional performance, correctly ranking causal variants as most damaging in 98% of cases where a mutation had already been identified in severe developmental disorders [35]. This model outperformed state-of-the-art competitors and uncovered 123 novel gene-disease associations previously undetected by conventional analyses [35] [36].

Notably, benchmarking reveals that different models excel at distinct tasks. DNABERT-2 shows the most consistent performance across human genome tasks, while NT-v2 excels in epigenetic modification detection, and HyenaDNA stands out for runtime scalability and long sequence handling [33]. This task-specific superiority underscores the importance of selecting models aligned with particular research objectives in evolutionary genomics.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Variant Effect Prediction Protocol

Objective: Evaluate models' ability to identify and prioritize disease-causing genetic variants using evolutionary constraints [35] [36].

Dataset Curation:

- Collect missense variants from large cohorts (e.g., 31,000 families with developmental disorders) [35]

- Include population frequency data from gnomAD and UK Biobank to distinguish benign polymorphisms [35]

- Incorporate evolutionary conservation scores from multiple sequence alignments across hundreds of species [35]

Methodology:

- Extract model embeddings for wild-type and mutant sequences

- Compute effect scores based on embedding perturbations or likelihood changes

- Calibrate scores using population frequency data to reduce ancestry bias [35]

- Evaluate using AUROC for known pathogenic versus benign variants

- Assess clinical utility by ranking causal variants in proband genomes [35]

Interpretation: Models like popEVE demonstrate 15-fold enrichment for true pathogenic variants over background rates, significantly outperforming existing tools and reducing false positives in underrepresented populations [35] [36].

Cross-Species Functional Element Detection

Objective: Identify conserved functional elements across evolutionary timescales using DNA foundation models.

Dataset Curation:

- Compile orthologous sequences from diverse eukaryotic and prokaryotic species [33]

- Include annotated functional elements (enhancers, promoters, coding sequences)

- Balance dataset with non-functional genomic regions

Methodology:

- Process sequences through foundation models to obtain embeddings

- Apply supervised classifiers (e.g., gradient-boosted trees) on embeddings

- Evaluate using stratified cross-validation across species

- Assess generalization to novel species not in training data

Interpretation: Models pre-trained on diverse species (e.g., NT-v2: 850 species) generally show better cross-species generalization, with performance dependent on evolutionary distance from training species [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DNA Foundation Model Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Sources/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Benchmarks | Standardized datasets for model evaluation | 4mC sites detection datasets (6 species), Exon classification tasks, Variant effect prediction cohorts [33] |

| Embedding Extraction Tools | Generate numerical representations from DNA sequences | HuggingFace Transformers, BioNeMo, Custom inference code [29] [30] |

| Single-Cell Atlases | Reference data for single-cell foundation models | Arc Virtual Cell Atlas (500M+ cells), scBaseCount, Tahoe-100M [37] |

| Perturbation Datasets | Evaluate cellular response predictions | Genetic perturbation screens (e.g., H1 hESCs with 300 perturbations) [37] |

| Interpretability Tools | Understand model features and decisions | Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs), Feature visualization platforms [34] |

| Model Training Frameworks | Customize and fine-tune foundation models | NVIDIA BioNeMo, PyTorch, Custom training pipelines [29] [30] |

Biological Interpretability and Model Insights

Understanding how DNA foundation models derive their predictions is crucial for biological validation and scientific discovery. Recent advances in interpretability methods have begun to decode the internal representations of these complex models.

Feature Visualization: Through techniques like sparse autoencoders (SAEs), researchers have identified that Evo 2 learns biologically meaningful features corresponding to specific genomic elements, including exon-intron boundaries, protein secondary structure patterns, tRNA/rRNA segments, and even viral-derived sequences like prophage and CRISPR elements [34]. These features emerge spontaneously during training without explicit supervision, demonstrating that the models discover fundamental biological principles directly from sequence data.

Evolutionary Conservation Signals: Models like popEVE leverage evolutionary patterns across hundreds of thousands of species to identify which amino acid positions in human proteins are essential for function [35] [36]. By analyzing which mutations have been tolerated or eliminated throughout evolutionary history, these models can distinguish pathogenic mutations from benign polymorphisms with high accuracy, even for previously unobserved variants [35].

Cell State Representations: Single-cell foundation models like scGPT learn representations that capture continuous biological processes such as differentiation trajectories and response dynamics [32]. The attention mechanisms in these models can reveal gene-gene interactions and regulatory relationships, providing insights into the underlying biological networks controlling cell fate decisions [32].

DNA foundation models represent a transformative advancement in evolutionary genomics, offering powerful new approaches for decoding the information embedded in biological sequences. Through comprehensive benchmarking, we observe that model performance is highly task-dependent, with different architectures excelling in specific domains. Evo 2 demonstrates exceptional capability in long-range dependency capture and whole-genome analysis, while specialized models like popEVE show remarkable precision in variant effect prediction for rare disease diagnosis [35] [29].

The field is rapidly evolving toward more biologically grounded evaluation metrics, with increasing emphasis on model interpretability, cross-species generalization, and clinical utility. Future developments will likely focus on multi-modal integration (combining DNA, RNA, and protein data), improved efficiency for longer contexts, and enhanced generalization to underrepresented species and populations. As these models become more sophisticated and interpretable, they promise to accelerate discovery across evolutionary biology, functional genomics, and therapeutic development.

For researchers selecting models, considerations should include: (1) sequence length requirements, (2) evolutionary scope of the research question, (3) available computational resources, and (4) specific task requirements (variant effect prediction, functional element detection, etc.). As benchmarking efforts continue to mature, the scientific community will benefit from more standardized evaluations and clearer guidelines for model selection in evolutionary genomics research.

The development of virtual cells—AI-powered computational models that simulate cellular behavior—promises to revolutionize biological research and therapeutic discovery. These models aim to accurately predict cellular responses to genetic and chemical perturbations, providing a powerful tool for understanding disease mechanisms and accelerating drug development [38]. The core value of these models lies in their Predict-Explain-Discover capabilities, enabling researchers not only to forecast outcomes but also to understand the underlying biological mechanisms and generate novel therapeutic hypotheses [38]. However, recent rigorous benchmarking studies have revealed a significant gap between the purported capabilities of state-of-the-art foundation models and their actual performance, raising critical questions about current evaluation practices and the true progress of the field.

This comparison guide objectively assesses the current landscape of virtual cell models for predicting cellular responses to genetic perturbations. By synthesizing findings from recent comprehensive benchmarks and emerging evaluation frameworks, we provide researchers with a clear understanding of model performance, methodological limitations, and the essential tools needed for rigorous assessment in this rapidly evolving field.

Performance Benchmarking: Surprising Results and Simple Baselines

Recent independent benchmarking studies have yielded surprising results that challenge the perceived superiority of complex transformer-based foundation models for perturbation response prediction.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Cell Models on Perturb-Seq Datasets (Pearson Δ Correlation)

| Model / Dataset | Adamson | Norman | Replogle K562 | Replogle RPE1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train Mean | 0.711 | 0.557 | 0.373 | 0.628 |

| scGPT | 0.641 | 0.554 | 0.327 | 0.596 |

| scFoundation | 0.552 | 0.459 | 0.269 | 0.471 |

| RF with GO features | 0.739 | 0.586 | 0.480 | 0.648 |

Unexpectedly, even the simplest baseline model—Train Mean, which predicts post-perturbation expression by averaging the pseudo-bulk expression profiles from the training dataset—consistently outperformed sophisticated foundation models across multiple benchmark datasets [39] [40]. More remarkably, standard machine learning approaches incorporating biologically meaningful features demonstrated substantially superior performance, with Random Forest (RF) models using Gene Ontology (GO) vectors outperforming scGPT by a large margin across all evaluated datasets [39] [40].

These findings were corroborated by a separate large-scale benchmarking effort that introduced the Systema framework for proper evaluation of perturbation response prediction [41]. This study found that simple baselines like "perturbed mean" (average expression across all perturbed cells) and "matching mean" (for combinatorial perturbations) performed comparably to or better than state-of-the-art methods including CPA, GEARS, and scGPT across ten different perturbation datasets [41].

Diagram 1: Benchmarking workflow for virtual cell models

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Protocols