Beyond AlphaFold: Benchmarking Evolutionary Algorithms Against Machine Learning for Novel Protein Folding and Design

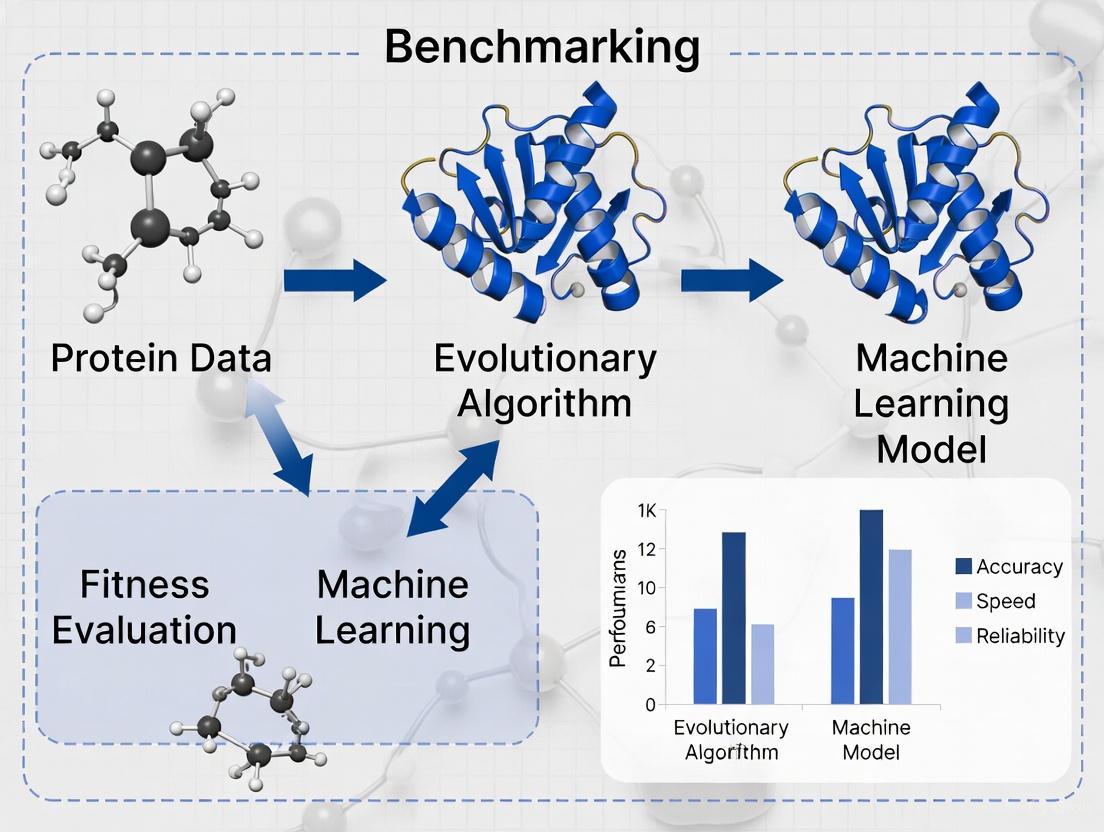

This article provides a comprehensive benchmark of Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) and Machine Learning (ML) models for protein structure prediction and design.

Beyond AlphaFold: Benchmarking Evolutionary Algorithms Against Machine Learning for Novel Protein Folding and Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive benchmark of Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) and Machine Learning (ML) models for protein structure prediction and design. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing their methodological applications and inherent strengths. The analysis delves into critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for deploying these computational tools effectively. Through a rigorous validation and comparative framework, assessing metrics like accuracy, novelty, and resource efficiency, the article synthesizes key takeaways. It concludes that a hybrid AI future, leveraging the complementary strengths of EAs and ML, holds the greatest promise for unlocking novel protein functions and accelerating biomedical discovery.

The Computational Protein Folding Landscape: From Physical Principles to AI-Driven Prediction

Biological Context: From Linear Chains to Functional Machines

The "protein folding problem" is one of biology's greatest unsolved mysteries. It refers to the challenge of predicting how a linear sequence of amino acids folds into a specific, three-dimensional structure that dictates its function [1]. Proteins are the primary architects of cellular activity, catalyzing reactions, providing structural support, and regulating biochemical processes. A protein's final, functional (native) tertiary structure is typically achieved through a stepwise establishment of regular secondary structures like α-helices and β-sheets, which then form the complete 3D architecture [2].

The precise final structure is not random; it is encoded in the amino acid sequence. This structure is crucial because it enables the protein to interact with other molecules and perform its role. Protein misfolding occurs when this process goes awry, and it is directly linked to severe diseases. Misfolded proteins can aggregate, leading to conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Type II Diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [3] [1]. For instance, in cardiovascular disease, misfolding of proteins like Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) can lead to atherosclerosis, where fatty acids accumulate in arteries, increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke [1].

The AI Revolution: Benchmarking Modern Protein Structure Prediction Tools

The field of protein structure prediction was revolutionized by artificial intelligence (AI), particularly with the introduction of AlphaFold2. Today, several AI models offer different trade-offs in accuracy, speed, and resource requirements, which are critical for researchers to consider.

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of three prominent ML-based protein folding methods, benchmarking their performance on key operational metrics.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Machine Learning Protein Folding Tools

| Model | Developer | Key Strength | Running Time (for 400aa sequence) | PLDDT Accuracy (for 400aa sequence) | GPU Memory Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESMFold | Meta AI | Exceptional speed | ~20 seconds | 0.93 [4] | 18 GB [4] |

| OmegaFold | HelixFold | Balance of speed and accuracy for shorter sequences | ~110 seconds | 0.76 [4] | 10 GB [4] |

| AlphaFold (via ColabFold) | Google DeepMind | High overall accuracy | ~210 seconds | 0.82 [4] | 10 GB [4] |

| OpenFold3 | Academic Consortium | Open-source, aims to match AlphaFold3 performance | Information Not Shown | Information Not Shown | Information Not Shown |

| SimpleFold | Apple | Uses general-purpose transformers, challenges need for complex custom architectures | Information Not Shown | Information Not Shown | Information Not Shown |

Analysis for Tool Selection

- For High-Throughput Screening: ESMFold's remarkable speed makes it ideal for tasks requiring rapid analysis of large numbers of sequences, such as initial characterization of genomic data [4].

- For Maximum Accuracy on Complex Targets: AlphaFold remains the gold standard for overall accuracy, often matching the precision of experimental methods. It is the best choice when the highest confidence prediction is required [1] [4].

- For Resource-Constrained Environments or Shorter Sequences: OmegaFold provides a compelling balance, offering good accuracy with lower computational cost, making it suitable for labs with limited GPU resources, especially for sequences under 400 amino acids [4].

- For Open-Source and Collaborative Science: The development of OpenFold3 is a significant move towards creating a powerful, open-source alternative to proprietary models, which can foster greater collaboration and transparency in research [5].

Experimental Paradigms: From Standardized Bench Experiments to Mega-Scale Assays

Understanding protein folding requires robust experimental data. The field has established standardized protocols for traditional kinetics studies and developed novel high-throughput methods to generate data on an unprecedented scale.

Consensus Experimental Conditions for Folding Kinetics

To enable meaningful comparison of folding data across different laboratories, the scientific community has proposed a set of consensus conditions for in vitro experiments [6].

Table 2: Standardized Experimental Conditions for Protein Folding Kinetics

| Experimental Parameter | Consensus Standard | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 25°C | Easily maintained, maximizes backward compatibility with existing literature [6]. |

| Buffer | 50 mM Phosphate or HEPES (pH 7.0) | Buffers effectively at neutral pH; a common baseline for experimental comparison [6]. |

| Denaturant | Urea | Preferred over guanidinium salts due to fewer confounding ionic strength effects [6]. |

| Data Reporting | lnkf (sec⁻¹) and m-values in (kJ/mol)/M | Standardized units ensure consistency and prevent errors in comparative analysis [3] [6]. |

High-Throughput Workflow: cDNA Display Proteolysis

Recent advances have enabled massively parallel measurement of protein stability. The cDNA display proteolysis method is a powerful high-throughput assay that can measure thermodynamic folding stability for hundreds of thousands of protein domains in a single experiment [7].

The diagram below illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow of this method.

This workflow begins with a synthetic DNA library where each oligonucleotide encodes a test protein. The DNA is transcribed and translated in vitro using cell-free cDNA display, resulting in proteins covalently attached to their encoding cDNA. This pool of protein-cDNA complexes is then subjected to protease digestion. The key principle is that unfolded proteins are cleaved more rapidly than folded ones. The intact (protease-resistant) complexes are purified, and the surviving sequences are quantified using deep sequencing. Finally, a Bayesian kinetic model uses the sequencing counts to infer the thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) for each of the hundreds of thousands of protein variants [7].

Researchers in protein folding and design rely on a suite of databases, software, and experimental resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Protein Folding Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ACPro Database [3] | Data Repository | A curated database of verified protein folding kinetics data, used for testing predictive models. |

| cDNA Display Proteolysis [7] | Experimental Assay | A high-throughput method for measuring thermodynamic folding stability for up to 900,000 protein variants. |

| Evolutionary Algorithms (DAO-MOGA) [8] | Computational Tool | A genetic algorithm for the inverse protein folding problem, optimizing for sequence diversity and structure. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Repository | The global repository for experimentally-determined 3D structures of proteins, used for training and validation. |

| 3D Profile (3D-1D Scoring) [8] | Computational Metric | A score evaluating the compatibility of an amino acid sequence with a target 3D structure for protein design. |

The integration of AI-based structure prediction with high-throughput experimental data is shaping the future of protein science. While AI tools like AlphaFold, ESMFold, and OmegaFold provide rapid structural models, large-scale experimental data remains crucial for understanding the hidden thermodynamics of folding—the energetics that drive the process and are invisible in static structures [7]. This synergy is particularly powerful for tackling the inverse folding problem, where evolutionary algorithms and other computational methods are used to design novel sequences that fold into a desired structure [8]. As both AI models and experimental techniques continue to evolve, they promise to unlock deeper insights into protein misfolding diseases and accelerate the rational design of proteins for therapeutic and biotechnology applications.

The protein folding problem represents one of the central challenges in structural biology, seeking to understand how a linear amino acid sequence spontaneously folds into a unique three-dimensional functional structure [9]. The energy landscape theory provides a powerful conceptual framework for understanding this process, proposing that natural proteins have evolved "minimally frustrated" folding landscapes that are funneled toward the native state [10]. This funneling allows proteins to avoid the kinetic traps that would be inevitable in a random heteropolymer and to fold efficiently on biological timescales.

In this framework, the molten globule represents a crucial intermediate state—a compact, partially organized ensemble of structures that retains significant secondary structure but lacks fixed tertiary side-chain packing [10]. The characterization of these landscapes involves both physical energy landscapes (derived from atomic interactions and physics-based models) and evolutionary energy landscapes (inferred from statistical analysis of homologous protein sequences) [10]. This article examines how modern machine learning methods for protein structure prediction navigate these landscapes, benchmarking their performance against physical principles and each other.

Theoretical Framework: Physical and Evolutionary Energies

The Principle of Minimal Frustration

The principle of minimal frustration posits that natural protein sequences have been evolutionarily selected to encode energy landscapes where interactions stabilizing the native state are mutually reinforcing rather than competing [10]. This stands in contrast to random amino acid sequences, which typically exhibit rugged landscapes with numerous deep kinetic traps. In minimally frustrated systems, the energetic bias toward the native state is sufficiently strong that the protein can rapidly fold without becoming trapped in non-native configurations.

Quantitatively, this relationship can be expressed through the equation:

[ 2\left(\frac{Tf}{T{sel}}\right) = \left(\frac{1}{Tg^2} + \frac{1}{Tf^2}\right) ]

Where (Tf) represents the protein's folding temperature, (Tg) indicates the glass transition temperature below which the protein would become trapped in non-native states, and (T{sel}) represents the evolutionary selection temperature [10]. For natural proteins, (Tf/T_g > 1), ensuring that folding occurs before the system becomes trapped in misfolded states.

Evolutionary Energy Landscapes from Sequence Coevolution

Direct coupling analysis (DCA) and other coevolution-based methods leverage the evolutionary record encoded in multiple sequence alignments to infer structural constraints [10]. The underlying assumption is that pairs of residues that interact in the tertiary structure will show correlated evolutionary patterns to maintain functional folds. These methods parameterize a Potts model Hamiltonian that assigns an evolutionary energy to any given sequence, effectively defining the evolutionary landscape [10].

The relationship between physical and evolutionary energies can be described by:

[ P(S) = \frac{e^{-\beta E(S)}}{Z} ]

Where (P(S)) represents the probability that sequence (S) adopts the folded structure, (E(S)) is the energy of the folded structure, (\beta = (kB T{sel})^{-1}), and (Z) is the partition function [10]. This formalism demonstrates how evolutionary constraints shape foldable sequences.

Pseudogenes as Natural Experiments in Landscape Devolution

Pseudogenes—formerly protein-coding sequences that have accumulated degenerative mutations—provide natural experiments for testing energy landscape theory [10]. When selective pressure to maintain a functional fold is removed, pseudogene sequences typically accumulate mutations that disrupt the native global network of stabilizing residue interactions, increasing frustration and decreasing foldability [10].

Interestingly, in some cases, pseudogene mutations actually decrease energetic frustration while simultaneously altering biological function, particularly in regions normally responsible for binding interactions [10]. This demonstrates how evolution tunes energy landscapes for both foldability and specific biological functions, and how these constraints can be decoupled when functional requirements are relaxed.

Machine Learning Approaches to Navigating Energy Landscapes

AlphaFold: Integrating Physical and Evolutionary Constraints

AlphaFold represents a transformative approach that combines physical, evolutionary, and geometric constraints through novel neural network architectures [11]. The system employs an Evoformer module—a novel neural network block that processes multiple sequence alignments and residue-pair representations through attention mechanisms [11]. This allows the network to reason about spatial and evolutionary relationships simultaneously.

The structure module then generates explicit 3D atomic coordinates through a series of iterative refinements, starting from trivial initial states and progressively developing accurate structures [11]. Throughout this process, AlphaFold employs principles of equivariance to ensure physical plausibility of the generated structures. The network's ability to provide accurate per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT) further demonstrates its sophisticated understanding of structural constraints [11].

ESMFold and OmegaFold: Alternative Architectural Strategies

ESMFold leverages a transformer-based architecture trained on evolutionary-scale protein sequence databases, enabling rapid structure prediction without explicit multiple sequence alignment construction during inference [4]. This approach benefits from the strengths of evolutionary covariance information while achieving significant speed advantages.

OmegaFold utilizes a deep learning model that emphasizes accuracy, particularly for shorter protein sequences [4]. Its architecture effectively balances computational efficiency with prediction reliability, making it suitable for scenarios where resource optimization is crucial.

Comparative Performance Benchmarking

Experimental Protocol and Metrics

To objectively evaluate these methods, we examine a systematic benchmarking study conducted on a g5.2xlarge A10 GPU configuration [4]. The evaluation employs several key metrics:

- Running Time: Total computation time required for structure prediction

- PLDDT (Predicted Local Distance Difference Test): Per-residue estimate of prediction confidence on a 0-1 scale

- Memory Usage: CPU memory consumption during prediction

- GPU Memory: Graphics memory utilization

The benchmarking was performed across protein sequences of varying lengths (50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1600 residues) to evaluate scalability and length-dependent performance characteristics [4].

Performance Comparison Across Sequence Lengths

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Sequence Length | Method | Running Time (s) | PLDDT Score | CPU Memory (GB) | GPU Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | ESMFold | 1 | 0.84 | 13 | 16 |

| OmegaFold | 3.66 | 0.86 | 10 | 6 | |

| AlphaFold | 45 | 0.89 | 10 | 10 | |

| 100 | ESMFold | 1 | 0.30 | 13 | 16 |

| OmegaFold | 7.42 | 0.39 | 10 | 7 | |

| AlphaFold | 55 | 0.38 | 10 | 10 | |

| 200 | ESMFold | 4 | 0.77 | 13 | 16 |

| OmegaFold | 34.07 | 0.65 | 10 | 8.5 | |

| AlphaFold | 91 | 0.55 | 10 | 10 | |

| 400 | ESMFold | 20 | 0.93 | 13 | 18 |

| OmegaFold | 110 | 0.76 | 10 | 10 | |

| AlphaFold | 210 | 0.82 | 10 | 10 | |

| 800 | ESMFold | 125 | 0.66 | 13 | 20 |

| OmegaFold | 1425 | 0.53 | 10 | 11 | |

| AlphaFold | 810 | 0.54 | 10 | 10 | |

| 1600 | ESMFold | Failed (OOM) | - | - | 24 |

| OmegaFold | Failed (>6000) | - | - | 17 | |

| AlphaFold | 2800 | 0.41 | 10 | 10 |

Data sourced from benchmarking study [4]. OOM = Out of Memory.

Method Selection Guidelines Based on Benchmarking Data

For short sequences (<400 residues): OmegaFold provides an optimal balance of accuracy (PLDDT) and resource efficiency, with significantly lower GPU memory requirements than ESMFold and faster execution than AlphaFold [4].

For medium-length sequences (400-800 residues): ESMFold offers the best speed-accuracy tradeoff, though at the cost of higher memory consumption [4].

For long sequences (>800 residues): AlphaFold demonstrates superior capability in handling very long proteins where other methods fail or show degraded performance [4].

For resource-constrained environments: OmegaFold provides the most memory-efficient operation across all sequence lengths [4].

Visualizing Protein Folding Method Workflows

Diagram 1: AlphaFold's iterative refinement process integrates MSA and coevolutionary information through Evoformer and Structure modules, with recycling enabling progressive improvement of predicted structures [11].

Table 2: Key Experimental Resources for Protein Folding Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AWSEM | Physical Model | Coarse-grained molecular dynamics for structure prediction | Physics-based folding simulation and landscape characterization [10] |

| DCA | Algorithm | Inference of coevolutionary constraints from sequence data | Evolutionary energy landscape calculation [10] |

| PDB | Database | Repository of experimentally determined protein structures | Method training and validation [12] [9] |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Precomputed structure predictions for proteomes | Benchmarking and biological discovery [12] |

| CATH/SCOP | Database | Hierarchical protein structure classification | Fold recognition and classification [13] |

| MSA Tools | Software | Construction of multiple sequence alignments | Evolutionary constraint identification [11] |

The remarkable accuracy achieved by modern ML protein folding methods, particularly AlphaFold, represents a convergence of physical understanding and data-driven pattern recognition [9] [11]. These systems successfully navigate protein energy landscapes by leveraging both the physical principle of minimal frustration and the evolutionary record of sequence covariation. While these methods differ in their architectural approaches and computational characteristics, they share a fundamental reliance on the energy landscape theory that has guided decades of protein folding research.

The benchmarking data reveals that method selection involves tradeoffs between speed, accuracy, and computational resources, with each approach exhibiting distinct strengths across different protein lengths and resource scenarios [4]. As these methods continue to evolve, their integration with physical models like AWSEM [10] promises to further bridge the gap between predictive accuracy and mechanistic understanding of the folding process.

This synergy between physical theory and machine learning not only advances structure prediction capabilities but also provides new avenues for exploring fundamental questions about protein folding landscapes, evolutionary constraints, and the molecular basis of biological function.

The protein folding problem—predicting a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence—has been one of the most significant challenges in biology for decades. For years, researchers relied on evolutionary algorithms and simplified models to tackle this complex problem. Methods using the HP lattice model, which classifies amino acids as hydrophobic (H) or polar (P), provided early insights but were limited to simplified representations and faced NP-hard computational complexity [14] [15]. The field underwent a seismic shift with the introduction of deep learning approaches, culminating in AlphaFold2's breakthrough performance in the CASP14 assessment in 2020 [12]. This transformation has moved the field from theoretical simplified models to predictions at near-experimental accuracy, revolutionizing structural biology and drug discovery.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three pioneering machine learning systems—AlphaFold, ESMFold, and OmegaFold—that have redefined the standards of protein structure prediction. We examine their performance metrics, architectural innovations, and practical applications within the context of benchmarking against traditional computational approaches.

Methodological Evolution: Architectural Innovations

Traditional Evolutionary Approaches

Before the deep learning revolution, protein folding optimization relied heavily on stochastic population-based algorithms. The Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm represented the state-of-the-art, using mutation, crossover, and selection operators to navigate the conformational landscape [14]. These methods operated on simplified models like the 3D AB off-lattice model, where energy functions favored hydrophobic interactions between non-polar amino acids. The local search mechanisms and component reinitialization strategies attempted to address the notorious challenges of rugged energy landscapes with numerous local minima [14]. However, these approaches could only confirm optimal solutions with 100% hit ratios for sequences containing up to 18 monomers, highlighting their limitations for larger proteins [14].

Modern Machine Learning Architectures

The transformation of protein structure prediction began with the integration of transformer neural networks and novel architectural paradigms.

AlphaFold2: Introduced the Evoformer architecture—a two-track system that jointly processes evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and pairwise relationships between residues. This attention-based mechanism draws global dependencies between amino acids to produce accurate atomic coordinates [12] [16]. AlphaFold-Multimer extended this capability to protein complexes by including multimeric structures in its training data [17].

ESMFold: Leverages a massive protein language model (ESM-2) trained on millions of protein sequences. Unlike AlphaFold2, ESMFold is alignment-free, predicting structures directly from single sequences without explicit MSAs. It incorporates a modified Evoformer block to refine its predictions [18] [16]. This architecture provides significant speed advantages, being up to 60 times faster than traditional MSA-dependent methods [19].

OmegaFold: Utilizes a protein language model (OmegaPLM) to learn single and pairwise residue embeddings, which are processed through a geometry-inspired transformer block called the Geoformer. Like ESMFold, it operates without MSAs, making it particularly valuable for proteins with few evolutionary relatives [16].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental shift in methodology from traditional evolutionary approaches to modern machine learning systems:

Performance Benchmarking: A Comparative Analysis

Recent systematic evaluations provide comprehensive performance comparisons across these systems. A benchmark study conducted on 1,327 protein chains deposited in the PDB between 2022 and 2024—ensuring no overlap with training data—revealed clear performance hierarchies:

Table 1: Overall Accuracy Metrics on Recent Protein Structures

| Method | Median TM-score | Median RMSD (Å) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 0.96 | 1.30 | Highest overall accuracy, excellent stereochemistry |

| ESMFold | 0.95 | 1.74 | Fast prediction, good for high-throughput screening |

| OmegaFold | 0.93 | 1.98 | Robust on orphan proteins, reasonable accuracy |

AlphaFold2 consistently achieves the highest median accuracy, as measured by both TM-score (0.96) and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD, 1.30 Å) [20]. Independent evaluations on CASP15 targets confirm this hierarchy, with AlphaFold2 attaining a mean GDT-TS score of 73.06, followed by ESMFold (61.62) and OmegaFold [16].

Speed and Resource Utilization

While accuracy is crucial, practical considerations of computational efficiency often influence method selection for large-scale applications:

Table 2: Computational Performance Comparison (A10 GPU)

| Method | Prediction Time (50 aa) | GPU Memory (50 aa) | CPU Memory | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESMFold | 1 second | 16 GB | 13 GB | High-throughput screening |

| OmegaFold | 3.66 seconds | 6 GB | 10 GB | Short sequences, resource-constrained environments |

| AlphaFold2 | 45 seconds | 10 GB | 10 GB | Maximum accuracy applications |

ESMFold demonstrates remarkable speed advantages, processing a 50-amino acid sequence in approximately 1 second compared to OmegaFold's 3.66 seconds and AlphaFold2's 45 seconds [4]. However, these speed advantages come with higher GPU memory requirements for shorter sequences [4]. OmegaFold strikes a balance with better memory efficiency, particularly valuable for shorter sequences (up to 400 amino acids) and resource-constrained environments [4].

Protein Length and Type Considerations

Method performance varies significantly with protein length and structural characteristics. For sequences shorter than 400 amino acids, OmegaFold frequently provides the optimal balance of accuracy and efficiency, achieving higher PLDDT scores than ESMFold on shorter sequences while using less memory [4]. ESMFold maintains strong performance across various protein lengths, even successfully predicting structures of large proteins with 540 residues with high accuracy (TM-score 0.98) [19]. However, all methods show declining accuracy as protein size increases, particularly for multidomain proteins with complex topologies where domain packing remains challenging [16].

Specialized Capabilities

Multimeric Predictions: AlphaFold-Multimer extends accurate predictions to protein complexes, successfully modeling approximately 70% of protein-protein interactions in benchmark tests [17]. While ESMFold has capabilities for predicting multimers (complexes of multiple protein chains), performance evaluation remains an active area of research [19].

Stereochemical Quality: AlphaFold2 produces structures with stereochemistry closest to experimental observations, as evidenced by Ramachandran plot distributions and MolProbity scores [16]. Both ESMFold and OmegaFold exhibit more physically unrealistic local structural regions, limiting their utility for applications requiring precise atomic coordinates [16].

Side-chain Positioning: All methods show room for improvement in side-chain positioning, with AlphaFold2 attaining the highest global distance calculation for side-chains (GDC-SC) score, though still below 50 [16].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Robust benchmarking requires standardized datasets and evaluation metrics. Key methodological approaches include:

Temporal Split Validation: Using proteins deposited in the PDB after the training cutoff dates of the tools being evaluated (e.g., July 2022-July 2024 structures for benchmarking tools trained on earlier data) ensures no data leakage [20].

Homology Reduction: Applying sequence identity thresholds (e.g., ≤30% identity to training sequences) via tools like MMseqs2 removes potential homology between benchmark and training datasets [17].

Multiple Assessment Metrics: Employing complementary metrics including TM-score (global topology), DockQ (interface quality for complexes), lDDT (local distance difference test), and PLDDT (per-residue confidence scores) provides a comprehensive accuracy profile [20] [17].

Workflow for Comparative Assessment

The typical workflow for benchmarking protein folding methods involves sequential steps of data preparation, model execution, and structural evaluation:

Successful protein structure prediction and analysis requires leveraging specialized databases, software tools, and computational resources:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Protein Structure Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Experimental protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| ESM Metagenomic Atlas | Database | 617M+ predicted metagenomic structures | https://esmatlas.com/ |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | 200M+ AlphaFold predictions | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| ColabFold | Software | Accessible AlphaFold/MMseqs2 implementation | https://colabfold.com |

| HuggingFace Transformers | Software | Simplified ESMFold API | https://huggingface.co/ |

| MMalign | Software | Structure comparison and alignment | https://github.com/ |

| DockQ | Software | Quality assessment of protein complexes | https://gitlab.com/ElofssonLab/DockQ |

These resources provide the foundational infrastructure for protein structure prediction, analysis, and validation. The ESM Metagenomic Atlas in particular represents a significant expansion of accessible structural information, containing 617 million predicted metagenomic protein structures that help illuminate the "dark matter" of protein space [18] [19].

The transformation of protein structure prediction through machine learning has provided researchers with an unprecedented set of tools for exploring structural biology. Based on comprehensive benchmarking:

AlphaFold2 remains the gold standard for maximum accuracy applications where computational resources and time are secondary concerns. Its superior performance on diverse protein types and excellent stereochemical quality make it ideal for detailed mechanistic studies and hypothesis generation.

ESMFold offers the best solution for high-throughput applications requiring rapid screening of multiple protein targets. Its alignment-free architecture enables speed advantages of 6-60× over MSA-dependent methods, though with slightly reduced accuracy [19].

OmegaFold provides a balanced option for shorter sequences and resource-constrained environments, with particularly strong performance on proteins under 400 amino acids while using less memory than ESMFold [4].

The choice between these systems ultimately depends on the specific research context—balancing accuracy requirements, computational resources, protein characteristics, and application scope. As the field continues to evolve, addressing current challenges in multidomain protein packing, side-chain positioning, and complex prediction will further enhance the transformative impact of these tools on biological research and therapeutic development.

The inverse protein folding problem (IFP)—finding amino acid sequences that fold into a defined three-dimensional structure—represents a fundamental challenge in structural biology and protein engineering [8]. For decades, scientists have sought to solve this problem to design novel proteins with customized functions for applications in medicine, biotechnology, and synthetic biology [21] [22]. Traditionally, two computational approaches have dominated this field: evolutionary algorithms (EAs) inspired by natural selection, and more recently, machine learning (ML) methods leveraging deep neural networks. While ML-based protein folding prediction tools like AlphaFold2 have garnered significant attention for their remarkable accuracy [4] [23], evolutionary algorithms continue to offer unique advantages for exploring the vast sequence space of possible proteins. Evolutionary approaches treat protein sequences as individuals in a population that evolves through selection, recombination, and mutation operations, effectively simulating molecular evolution in silico to discover novel sequences optimized for specific structural constraints [8] [24]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, examining their respective strengths, limitations, and performance in de novo protein exploration.

Fundamental Principles: EA vs. ML Approaches

Evolutionary Algorithms in Protein Design

Evolutionary algorithms approach protein design as an optimization problem, navigating the complex fitness landscape of possible sequences to find those that fulfill structural objectives [24]. In the context of inverse protein folding, a multi-objective genetic algorithm (MOGA) might simultaneously optimize for secondary structure similarity and sequence diversity [8]. These algorithms maintain a population of candidate sequences that undergo iterative improvement through biologically-inspired operations:

- Selection: Preferentially retaining sequences that better match the target structure.

- Crossover: Recombining promising sequences to explore new combinations.

- Mutation: Introducing random changes to maintain diversity and avoid local optima.

The "diversity-as-objective" approach represents an advanced EA strategy where diversity preservation serves dual purposes: it enhances algorithm performance by pushing exploration to new areas of the search space, while simultaneously addressing the problem requirement of finding highly dissimilar protein sequences that achieve the same structural outcome [8].

Machine Learning in Protein Design

Modern ML approaches to protein design typically employ deep learning architectures that have been trained on vast datasets of known protein structures [21] [23]. These methods establish high-dimensional mappings between sequence, structure, and function, enabling rapid generation of novel proteins. Unlike EAs which search through explicit optimization, ML models often employ generative approaches:

- Discriminative models like AlphaFold2 and ESMFold predict structures from sequences [4].

- Generative models like RFdiffusion generate novel protein structures and sequences through diffusion processes [23].

- Inverse folding models like ProteinMPNN design sequences for given backbone structures [25] [23].

These data-driven methods learn statistical patterns from existing protein databases, allowing them to propose novel sequences with high predicted stability and accuracy [21].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarking

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics and applications of evolutionary algorithms versus machine learning methods in protein design.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Evolutionary Algorithms and Machine Learning Methods in Protein Design

| Method | Typical Success Rate | Sequence Diversity | Computational Demand | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Varies by implementation; often requires extensive screening [26] | High (explicitly optimized as objective) [8] | Moderate to High (population-based, multiple generations) [8] [24] | Inverse folding, sequence diversification, exploring uncharted sequence space [8] |

| ProteinMPNN | Foundation for many ML pipelines [23] | Moderate (can sample multiple sequences) [25] | Low (single forward pass) [25] | Sequence design for given backbones, functional site incorporation [25] |

| RFdiffusion + ProteinMPNN | ~3% designability for challenging enzyme designs [25] | Moderate (conditional generation) [23] | High (diffusion process, multiple steps) [23] | De novo binder design, symmetric oligomers, enzyme active site scaffolding [23] |

| EnhancedMPNN (ResiDPO) | 17.57% (nearly 3x improvement on challenging benchmarks) [25] | Moderate (optimized for designability over diversity) [25] | Low to Moderate (inference similar to ProteinMPNN) [25] | Enzyme design, binder design, improved designability [25] |

The performance metrics reveal a fundamental trade-off between designability and diversity. While ML methods have made significant advances in success rates for specific design challenges, evolutionary algorithms maintain their advantage in exploring diverse regions of the sequence space [8]. The recent development of ResiDPO demonstrates how preference optimization—using AlphaFold's pLDDT scores as rewards—can bridge this gap, significantly improving designability while maintaining reasonable diversity [25].

Table 2: Structure Prediction Tools Used for Validation

| Prediction Tool | Key Characteristics | Typical Use in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | High accuracy, computationally intensive [4] [26] | Gold-standard validation, pLDDT scores for designability [25] [26] |

| ESMFold | Fast inference, single-sequence prediction [4] | Rapid screening, large-scale validation [4] |

| RoseTTAFold | Balanced accuracy/speed, modular architecture [23] [26] | RFdiffusion foundation, alternative validation [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Inverse Folding

A typical EA implementation for inverse protein folding follows this workflow [8]:

Initialization: Generate a population of random amino acid sequences or seeds based on known structural constraints.

Evaluation: Score each sequence using energy functions and secondary structure prediction tools (e.g., PSIPRED, JUFO) to assess compatibility with the target structure.

Multi-objective Optimization: Simultaneously optimize:

- Secondary structure similarity (e.g., using Q3 score comparing predicted vs. target structure)

- Sequence diversity (e.g., using pairwise Hamming distance or BLOSUM substitution matrix)

Diversity Preservation: Implement niching or crowding techniques to maintain population diversity throughout evolution.

Termination & Validation: Select best-performing sequences for tertiary structure prediction using tools like AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold, followed by experimental characterization.

RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN Pipeline

The state-of-the-art ML pipeline for de novo protein design combines RFdiffusion for structure generation with ProteinMPNN for sequence design [23]:

Conditional Generation: Specify design objectives (e.g., symmetric architecture, binding interface, enzymatic active site).

Diffusion Process: RFdiffusion progressively denoises random initial coordinates through multiple steps (typically 200+ iterations) to generate protein backbones matching specifications.

Sequence Design: ProteinMPNN generates sequences for the designed backbones, sampling multiple candidates per structure.

In Silico Validation: Predict structures of designed sequences using AlphaFold2 and filter based on:

- High confidence (mean pAE < 5)

- Global backbone RMSD < 2.0 Å to design model

- Local backbone RMSD < 1.0 Å on scaffolded functional sites

Experimental Characterization: Express and purify designs for validation using circular dichroism, SEC-MALS, X-ray crystallography, and functional assays.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Protein Design Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 [4] [26] | Structure Prediction | Predict 3D structure from sequence with high accuracy | Server, Local Install |

| RFdiffusion [23] | Generative Model | De novo protein structure generation conditioned on specifications | Open Source |

| ProteinMPNN [25] [23] | Inverse Folding | Sequence design for given protein backbones | Open Source |

| RoseTTAFold [26] | Structure Prediction | Alternative structure prediction method, basis for RFdiffusion | Open Source |

| ESMFold [4] | Structure Prediction | Fast single-sequence structure prediction | Server, API |

| Rosetta [27] [26] | Software Suite | Physics-based modeling, energy calculations, design | Commercial License |

Evolutionary algorithms and machine learning methods offer complementary strengths for de novo protein exploration. EAs excel at broadly exploring sequence space and maintaining diversity, making them particularly valuable for fundamental investigations into the sequence-structure relationship and for problems where diverse solutions are paramount [8] [24]. ML methods, particularly modern deep learning approaches, provide unprecedented accuracy and efficiency for specific design challenges, enabling practical applications in therapeutic and enzyme design [21] [23]. The future of protein design lies not in choosing one approach over the other, but in developing hybrid methodologies that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. Techniques like ResiDPO, which incorporates structural feedback from AlphaFold into sequence design models, represent promising steps in this direction [25]. As both fields continue to advance, the integration of evolutionary principles with deep learning architectures will likely unlock new possibilities for engineering functional proteins, accelerating progress in biotechnology and medicine.

The field of protein structure prediction has reached a transformative juncture. With the advent of deep learning systems like AlphaFold that have effectively solved the single-domain protein folding problem, the benchmarking landscape is undergoing a fundamental redefinition [28] [11]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this creates a critical dichotomy in evaluation paradigms: the established quest for accuracy (precisely reproducing known structures) is now complemented by the emerging challenge of assessing novelty (designing new functional proteins and predicting complex, previously uncharacterized assemblies) [29] [8].

This guide objectively compares the performance of modern computational methods across these two divergent benchmarking goals. We synthesize data from recent Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, analyze emerging AI-driven platforms, and provide a structured framework for selecting tools based on specific research objectives—whether validating known biological mechanisms or pioneering novel therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Established Benchmarks

The CASP competitions provide standardized, blind tests for rigorously evaluating protein structure prediction methods. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for prominent tools, highlighting the distinction between high-accuracy predictors and those capable of generating novel structures.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Leading Protein Structure Prediction Tools on Established Benchmarks

| Method | Primary Developer | Key Capabilities | Accuracy (TM-score) | Novelty Support | CASP Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 | Google DeepMind | Multi-component complexes (proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands) [29] | ≥50% improvement on protein-ligand vs. prior methods [29] | Limited de novo design | Dominant in accuracy categories [28] |

| Boltz-2 | MIT & Recursion | Joint structure & binding affinity prediction [29] | Nearly doubles previous affinity prediction methods [29] | Integrated functional property prediction | N/A (Released post-CASP16) |

| RFdiffusion | Baker Institute/University of Washington | Generative protein design [29] | N/A (Design-focused) | High: Novel protein & binder generation [29] | Evaluated in specialized design challenges |

| Evolutionary Algorithms (MOGA) | Academic Research | Inverse folding problem optimization [8] | Varies by implementation | High: Diverse sequence generation for fixed structures [8] | Limited application in mainstream CASP |

Experimental Protocols for Accuracy Assessment

Standardized evaluation methodologies are crucial for meaningful comparison across different protein structure prediction tools. The following experimental protocol is employed in benchmarks like CASP and DisProtBench:

- Test Set Curation: Proteins with recently solved experimental structures (via X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM) that are withheld from public databases and not used in model training form the blind test set [11] [30].

- Structure Prediction: Participating research groups submit predicted 3D models for the target protein sequences within a specified timeframe.

- Metric Calculation: Predictions are compared to experimental ground truth using multiple quantitative metrics:

- Global Structure Measures: TM-score (0-1 scale, where >0.8 indicates correct fold) and RMSD (lower values indicate higher accuracy) assess overall structural similarity [31] [11].

- Local Structure Measures: lDDT (local Distance Difference Test) evaluates the local atomic geometry and integrity [31] [11].

- Interface Quality Measures: For complexes, specialized metrics like DockQ and Interface Contact Score (ICS) assess the accuracy of intermolecular interfaces [31].

- Statistical Analysis: Results are aggregated across all targets to compute median performance and statistical significance, often segmented by target difficulty (e.g., with or without evolutionary relatives, presence of disordered regions) [28] [30].

The Novelty Frontier: Benchmarking for Protein Design and Complex Assembly

While accuracy benchmarks mature, novelty assessment requires distinct frameworks focusing on functional creation and complex system modeling.

Table 2: Novelty-Oriented Benchmarking Criteria and Methodologies

| Novelty Dimension | Benchmarking Focus | Evaluation Methods | Leading Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo Protein Design | Generating stable, foldable sequences not found in nature [8] | Experimental validation of stability & fold, computational stability metrics | RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN [29] |

| Functional Protein Engineering | Designing proteins with novel functions (e.g., binding, catalysis) [32] | Binding affinity assays, enzymatic activity tests, success rate in low-data regimes | AiCE, RFdiffusion-based workflows [29] [32] |

| Multi-Molecular Complex Prediction | Modeling protein-protein, protein-nucleic acid, protein-ligand interactions [29] | Interface-specific metrics (ICS, pDockQ), comparison to experimental complex structures | AlphaFold 3, Boltz-2 [29] |

| Conformational Dynamics | Capturing flexibility, multiple states, allostery, and disordered regions [29] [30] | Comparison to NMR ensembles, conformational diversity metrics, ability to sample alternate states | AFsample2, specialized AlphaFold modifications [29] |

Addressing the Disordered Reality: DisProtBench

A significant limitation of traditional benchmarks is their underrepresentation of intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which are crucial for many biological functions. DisProtBench addresses this by providing a specialized benchmark for evaluating model performance in biologically challenging contexts involving structural disorder [30]. Its 2025 results reveal significant variability in model robustness under disorder, with low-confidence regions strongly linked to functional prediction failures. This emphasizes that global accuracy metrics alone are insufficient for assessing performance on novel, functionally relevant targets [30].

The Evolutionary Algorithm Perspective: Bridging Accuracy and Novelty

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) address the inverse folding problem (IFP)—finding sequences that fold into a defined structure—which positions them uniquely between accuracy and novelty paradigms [8].

Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithms (MOGA) using diversity-as-objective approaches optimize both secondary structure similarity and sequence diversity, enabling deeper exploration of the sequence solution space [8]. The validation process involves tertiary structure prediction for generated sequences, comparing both secondary structure annotation and full atomic models to the original protein structure [8].

Learnable Evolutionary Algorithms (LMOEAs) represent recent advancements where machine learning models guide evolutionary search. These hybrids, such as performance improvement-directed learnable generators, help navigate large-scale multiobjective optimization problems by learning compressed representations of promising solutions, accelerating convergence in high-dimensional spaces relevant to protein design [33].

Visualization: Accuracy vs. Novelty in Benchmarking Methodology

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship and methodological differences between accuracy-focused and novelty-focused benchmarking paradigms in protein structure prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Platforms for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 Server | Web Server | Free prediction of biomolecular complexes for non-commercial use [29] | Publicly accessible via DeepMind |

| PSBench | Benchmarking Framework | Large-scale benchmark for evaluating protein complex model accuracy [31] | Open-source on GitHub with datasets on Harvard Dataverse |

| DisProtBench | Specialized Benchmark | Evaluation of model performance on intrinsically disordered regions and complex biological contexts [30] | Available via academic portal with precomputed structures |

| Boltz-2 | Open-source Model | Simultaneous prediction of protein-ligand structure and binding affinity [29] | Permissive MIT license; available on platforms like Nano Helix |

| ProteinMPNN | Algorithm | Sequence design for given protein backbones, enhancing stability and binding [29] | Open-source, commonly integrated into design workflows |

| Nano Helix Platform | Commercial Platform | AI-powered interface integrating multiple prediction and design tools (RFdiffusion, Boltz-2, ProteinMPNN) [29] | Commercial service with accessible interface |

The choice between accuracy-focused and novelty-focused protein structure prediction tools fundamentally depends on the research objective. For applications in functional annotation and drug target validation where reliability is paramount, accuracy-optimized tools like AlphaFold 3 remain dominant, particularly for single-chain and well-folded domains [28] [29]. For challenges in therapeutic protein engineering, drug discovery for complex targets, and fundamental research on disordered systems, novelty-capable platforms like Boltz-2, RFdiffusion, and evolutionary approaches offer the necessary flexibility and functional insight, despite potentially lower atomic-level accuracy on standard benchmarks [29] [8] [30].

The future lies in hybrid approaches that integrate physical constraints, evolutionary data, and deep learning—a direction already evident in tools like Boltz-2's incorporation of molecular dynamics data and evolutionary algorithms' integration with neural networks [29] [33]. As the field progresses, benchmarking frameworks must simultaneously evolve to rigorously assess both the accurate replication of biological reality and the innovative creation of functional protein solutions.

Methodologies in Practice: Implementing ML and EA Frameworks for Protein Modeling

This guide provides a detailed comparison of three leading machine learning models for protein structure prediction: AlphaFold, ESMFold, and ColabFold. For researchers benchmarking evolutionary algorithms against modern ML approaches, understanding the architectural nuances, performance trade-offs, and practical implementation requirements of these tools is essential.

The predictive prowess of each model stems from its unique underlying architecture and the type of data it prioritizes.

AlphaFold 2: The architecture is built around the Evoformer module, a novel neural network that operates on multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). [34] The Evoformer processes the MSA and pairwise representations through a series of transformations to distill evolutionary constraints. This information is then passed to a structure module that iteratively refines the 3D atomic coordinates, using a transformer architecture to rotate and translate each residue into its final position. [12] A final refinement step applies physical constraints through energy minimization. [12]

ESMFold: This model leverages a large protein language model, ESM-2, which is pre-trained on millions of protein sequences. [35] ESMFold operates as an end-to-end transformer that directly maps a single protein sequence to its 3D structure. It bypasses the need for MSAs by internalizing evolutionary information from its pre-training data, which allows it to make predictions from a single sequence. [36] Its key strength lies in predicting structures for "orphan" proteins that lack sequence homologs. [36]

ColabFold: This is not a new core model but a highly optimized implementation that repackages AlphaFold 2 with a drastically accelerated MSA generation step. [37] It replaces the computationally intensive HHblits and BLAST tools with MMseqs2, leading to a 40- to 60-fold speedup in homology search. [37] [36] ColabFold makes state-of-the-art structure prediction accessible via web servers and streamlined local installation, enabling large-scale batch predictions. [37]

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow and core components of each system.

Performance and Benchmarking Data

Independent benchmarks provide critical data for comparing the accuracy and computational efficiency of these predictors. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent evaluations.

| Metric | AlphaFold2 | ESMFold | OmegaFold | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median TM-score | 0.96 [20] | 0.95 [20] | 0.93 [20] | Higher is better. Benchmark on 1,327 PDB chains (2022-2024). [20] |

| Median RMSD (Å) | 1.30 [20] | 1.74 [20] | 1.98 [20] | Lower is better. Same benchmark as above. [20] |

| Speed (shorter sequences) | Slow [4] | Fast [4] | Moderate [4] | ESMFold is fastest for sequences of length 50-100. [4] |

| MSA Dependency | Required [36] | Not Required [36] | Not Required [4] | ESMFold and OmegaFold are alignment-free, single-sequence predictors. [4] [36] |

| Key Strength | Highest overall accuracy [20] | Speed & orphan proteins [36] | Balance of speed and accuracy [4] | AlphaFold2 is most precise; ESMFold is best for proteins without homologs. [20] [36] |

A separate benchmark focusing on computational resource usage provides further practical insights, particularly for deployment considerations.

| Model | PLDDT (Length ~400) | Running Time (s, Length ~400) | GPU Memory (GB, Length ~400) | Notable Failure Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold (ColabFold) | 0.82 [4] | 210 [4] | 10 [4] | Stable resource usage across lengths. [4] |

| ESMFold | 0.93 [4] | 20 [4] | 18 [4] | Failed at 1600 residues (Out of GPU Memory). [4] |

| OmegaFold | 0.76 [4] | 110 [4] | 10 [4] | Failed at 1600 residues (Extreme slowdown >6000s). [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure reproducible and fair comparisons of protein structure prediction tools, a standardized experimental protocol is essential. The following workflow, derived from independent studies, outlines the key steps.

The methodology visualized above can be broken down into the following steps:

- Dataset Curation: Independent benchmarks rely on high-quality datasets of experimentally determined structures that were released after the training periods of the models being evaluated. For instance, one major benchmark used 1,327 protein chains deposited in the PDB between July 2022 and July 2024 to ensure no data leakage. [20] The dataset should cover diverse protein families, lengths, and experimental contexts.

- Prediction Generation: Run each model on the entire benchmark dataset. For tools like ColabFold, this is often done using a Dockerized environment to ensure consistency and facilitate large-scale batch predictions. [37] It is critical to use the same hardware (e.g., A10 GPU) to compare running time and resource usage fairly. [4]

- Metric Calculation: Compare each predicted structure to its experimental ground truth using standard metrics.

- TM-score: A scale of 0-1 that measures global fold similarity, where >0.5 indicates the same fold and closer to 1 indicates higher accuracy. [20]

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average atomic distance between predicted and native structures, with lower values (e.g., 1-2 Å) indicating better accuracy. [20]

- pLDDT: The model's own per-residue confidence score on a scale of 0-100. [4]

- Performance Analysis: Analyze the results to identify strengths and weaknesses. This includes comparing median scores, success rates, and investigating the sequence, structural, or experimental features that lead to substantial discrepancies in accuracy. [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key computational tools and resources essential for working with these protein folding platforms.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Docker | Containerization platform | Creates reproducible environments for running ColabFold and other predictors locally. [37] |

| MMseqs2 | Rapid sequence search and clustering | Used by ColabFold to generate MSAs 40-60x faster than standard tools, enabling high-throughput work. [37] |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Repository of experimental protein structures | Source of ground-truth data for model validation and benchmarking. [20] |

| ABCFold | Unified execution toolkit | Simplifies running and comparing AlphaFold 3, Boltz-1, and Chai-1 by standardizing inputs and outputs. [38] |

| AlphaBridge | Interaction interface analysis | Post-processes and visualizes interaction interfaces in macromolecular complexes predicted by AlphaFold 3. [38] |

Practical Implementation and Deployment

The choice between these models is highly context-dependent. AlphaFold2 remains the gold standard for maximum accuracy when computational resources and time are not primary constraints. [20] [34] ESMFold is the preferred choice for high-throughput screening of large sequence databases or for predicting structures of orphan proteins with no close homologs, thanks to its single-sequence speed. [36] ColabFold strikes an excellent balance, offering near-AlphaFold2 accuracy with dramatically reduced runtimes, making it a practical default for most research applications. [37] [36]

For large-scale projects, a Dockerized implementation of ColabFold is recommended for its flexibility and efficiency. This involves pulling the official Docker image, setting up local sequence databases (e.g., UniRef30) to avoid relying on public servers, and executing batch predictions via command-line scripts that manage both the MSA generation and structure prediction steps. [37]

The prediction of a protein's tertiary structure from its amino acid sequence stands as one of the most significant challenges in computational biology, with profound implications for drug discovery and understanding biological processes [15]. While deep learning methods like AlphaFold have recently dominated the field, evolutionary algorithms (EAs) continue to offer unique advantages as robust, flexible optimization approaches that can handle arbitrary energy functions and complex biological constraints [15] [39]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of EA methodologies for protein folding, benchmarking them against contemporary machine learning approaches to delineate their respective strengths, limitations, and optimal application domains within biomedical research.

EAs represent a class of population-based optimization techniques inspired by natural selection that have demonstrated considerable promise in navigating the complex conformational spaces of proteins [40] [39]. Unlike deep learning methods that require extensive training datasets and substantial computational resources, EAs operate on principles of stochastic search and fitness-based selection, making them particularly suitable for problems with complex energy landscapes and specific constraint handling requirements [15] [41]. The robustness of EAs stems from their ability to incorporate diverse forms of biological knowledge through customized representations, fitness functions, and genetic operators without being constrained to specific mathematical formulations of the energy landscape [15].

EA Methodologies and Workflow

Representation Schemes

The choice of representation fundamentally shapes the EA's search space and operational efficiency. Multiple representation schemes have been developed, each with distinct trade-offs between biological fidelity and computational tractability.

Lattice Models: Simplified representations that map amino acids onto discrete lattice points, with the 3D Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) lattice being particularly prominent due to its high packing density and ability to render conformations closer to real protein structures [15]. The FCC model places residues at (x, y, z) coordinates where x + y + z is even, with each point having 12 adjacent neighbors, enabling more realistic bond angles (60°, 90°, 120°, and 180°) compared to simpler cubic lattices [15].

Cartesian Coordinates: Direct representation using Cα Cartesian coordinates of the protein chain, enabling meaningful recombination through rigid superposition of parent structures followed by linear combination of coordinates [40]. This approach preserves topological similarities and long-range contacts between generations, significantly improving convergence over standard genetic algorithms.

Internal Coordinates: Encodings using dihedral angles or internal coordinates with absolute moves, facilitating the generation of valid conformations while reducing the search space dimensionality [39].

Table 1: Comparison of EA Representation Schemes for Protein Folding

| Representation | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D FCC Lattice | Residues placed on face-centered cubic lattice points | High packing density; avoids parity problems; realistic angles | Discrete conformation space; limited resolution | Ab initio folding; hydrophobic core optimization |

| Cartesian Coordinates | Direct Cα atomic coordinates | Preserves parent topology; meaningful recombination | Requires validity checking; potential steric clashes | Small proteins and fragments |

| Internal Coordinates | Bond angles and torsion angles | Natural biological representation; reduced search space | Complex operator design; potential kinematic issues | Secondary structure prediction |

Fitness Functions

The fitness function quantifies conformation quality, directly guiding the evolutionary search toward biologically relevant structures.

HP Model Energy: The foundational Hydrophobic-Polar model emphasizes hydrophobic interactions as the primary folding driver, assigning H-H topological contacts an energy of -1 while ignoring other interactions [15] [39]. The objective is minimizing total energy (maximizing H-H contacts), which corresponds to forming a compact hydrophobic core.

Physics-Based Potentials: Molecular mechanics forcefields like AMBER incorporate bond lengths, angles, dihedral terms, and non-bonded interactions (Lennard-Jones and Coulomb forces) [41]. These offer higher biological fidelity but increase computational complexity substantially.

Knowledge-Based Potentials: Statistical potentials derived from known protein structures in databases like PDB, which capture observed atomic contact preferences and residue packing patterns [40].

Multi-Objective Formulations: Combined functions addressing competing objectives like energy minimization, secondary structure preservation, and evolutionary conservation metrics.

Genetic Operators

Specialized genetic operators balance exploration of new conformations with exploitation of promising regions in the fitness landscape.

Crossover Operators:

- Lattice Rotation Crossover: Exploits geometric properties of 3D FCC lattice by rotating subsequences to increase successful recombination rates [15].

- Cartesian Combination: Performs rigid superposition of parent chains followed by linear combination of coordinates, preserving structural motifs [40].

- Dynamic Hill-Climbing Crossover: Asynchronously generates and inserts offspring within the same generation, applying pull-move transformations to ensure validity [39].

Mutation Operators:

- K-site Move: Mutates a contiguous block of K residues, providing sufficient structural changes within a fixed length interval [15].

- Generalized Pull Move: Single residue movement diagonally to adjacent positions, pulling connected residues along the chain to maintain validity [15] [39]. This reversible, complete operator enables efficient local exploration.

- Steepest-Ascent Hill-Climbing Mutation: Systematically applies pull-move transformations at all possible positions, selecting the most beneficial modification [39].

Diversification Mechanisms: Explicit replacement of redundant individuals with new genetic material prevents premature convergence, using similarity metrics based on topological features or contact maps [39].

EA Workflow for Protein Structure Prediction

Comparative Performance Analysis

EA vs. Machine Learning Approaches

The protein folding landscape has been transformed by deep learning methods, yet EAs maintain relevance in specific research contexts. The table below provides a systematic comparison of computational approaches based on recent benchmarking studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Protein Folding Methods

| Method | Type | Accuracy (TM-score) | Computational Requirements | Inference Speed | Training Demand | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA with Hill-Climbing [39] | Evolutionary | Varies by instance | Moderate CPU | Minutes to hours (sequence-dependent) | None | Handles arbitrary energy functions; constraint satisfaction |

| EA with Lattice Rotation [15] | Evolutionary | Finds previously unknown optima | High CPU | Hours for complex sequences | None | Robustness; no specific math optimization required |

| SPIRED [42] | Deep Learning (Single-sequence) | 0.786 (CAMEO) | 1 GPU | ~5x faster than ESMFold/OmegaFold | 10x reduction vs. SOTA | End-to-end fitness prediction; optimized for stability |

| ESMFold [4] [42] | Deep Learning (Single-sequence) | High (exact values N/A) | 13-20GB GPU Memory | Fast (seconds for short sequences) | Massive | Speed; no MSA required |

| OmegaFold [4] [42] | Deep Learning (Single-sequence) | 0.778-0.805 (CAMEO) | 6-11GB GPU Memory | Moderate | Massive | Accuracy on short sequences; memory efficient |

| AlphaFold [4] [42] | Deep Learning (MSA-based) | >0.9 (CASP14) | 10GB GPU Memory | Slow (minutes to hours) | Massive | State-of-the-art accuracy; experimental validation |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

HP Lattice Folding Protocol: EA performance is typically evaluated on the HP model using standardized benchmark sequences [15] [39]. The experimental protocol involves: (1) initializing a population of valid self-avoiding walks on the lattice; (2) iteratively applying genetic operators with hill-climbing; (3) enforcing diversification when population diversity drops below a threshold; (4) terminating after convergence or maximum generations; (5) comparing found minima against known optimal configurations.

Real-Protein Folding Protocol: For real proteins, EAs employ physics-based energy functions and experimental constraints [40] [41]. The protocol includes: (1) extracting sequence and secondary structure predictions; (2) defining flexible and constrained regions; (3) applying Cartesian or internal coordinate representations; (4) using knowledge-based potentials for fitness evaluation; (5) validating against experimental NMR or crystallographic data when available.

Performance Metrics: Key evaluation metrics include: (1) TM-score for structural similarity [42]; (2) RMSD for atomic-level accuracy; (3) number of H-H contacts for HP models; (4) energy attainment ratio (found minimum vs. known optimum); (5) computational time to solution; (6) success rate across multiple runs.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Protein Folding Studies

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPstruct [15] | Software Tool | Constraint programming for optimal HP folding | Finding global minima; benchmarking EA performance |

| OpenMM [41] | Molecular Dynamics Framework | Physics-based energy evaluation | Fitness calculation with molecular mechanics potentials |

| SCOPe Database [42] | Structural Classification | Protein fold taxonomy and benchmarking | Comprehensive fold-level performance evaluation |

| CAMEO Dataset [42] | Benchmark Targets | Weekly updated protein structure prediction targets | Method validation on novel folds |

| CASP Dataset [42] | Benchmark Targets | Blind prediction competition targets | Gold-standard performance assessment |

| PDB Database [42] | Structural Repository | Experimentally determined protein structures | Training knowledge-based potentials; method validation |

| FSx for Lustre [43] | High-throughput Storage | Rapid access to genetic databases (BFD, MGnify) | Accelerating MSA construction in hybrid workflows |

| SageMaker [43] | ML Workflow Platform | Orchestrating protein folding pipelines | Large-scale comparative studies |

Method-Application Mapping in Protein Folding Research

Evolutionary algorithms maintain a distinct and valuable position in the protein folding methodology landscape, particularly for problems involving complex energy functions, specific constraints, or scenarios where training data is limited. The integration of hill-climbing strategies, problem-specific genetic operators, and explicit diversification mechanisms has significantly enhanced EA performance, enabling them to find previously unknown optimal conformations even in challenging HP model instances [15] [39].

For researchers and drug development professionals, method selection should be guided by specific project requirements:

Choose EAs when working with novel energy functions, incorporating complex biological constraints, handling proteins with limited evolutionary information, or when computational resources for training deep learning models are unavailable [15] [41].

Prefer deep learning methods (AlphaFold, ESMFold, OmegaFold) for high-throughput prediction of standard protein sequences, when maximum accuracy is required, or when working with proteins with rich evolutionary information [4] [42].

Consider hybrid approaches that use EAs for refinement of deep learning-predicted structures, particularly for optimizing specific properties like stability or binding affinity [43] [42].

The recent development of efficient single-sequence predictors like SPIRED, which offers 5-fold acceleration over previous methods, demonstrates the ongoing innovation in protein structure prediction [42]. However, EAs continue to evolve as well, with advanced operators like lattice rotation and generalized pull moves expanding their capabilities [15]. For the foreseeable future, both paradigms will likely coexist, each addressing different aspects of the multifaceted protein folding problem and enabling researchers to tackle an increasingly diverse range of biological and therapeutic challenges.

ML for Rapid Prediction vs. EA for De Novo Design and Optimization

The advent of sophisticated computational methods has revolutionized structural biology and protein engineering. Two dominant paradigms have emerged: machine learning (ML) for the rapid prediction of protein structures from sequences, and evolutionary algorithms (EA) for the de novo design and optimization of protein sequences for desired properties. This guide provides a objective comparison of these approaches, benchmarking their performance, outlining experimental protocols, and contextualizing their roles within a modern research workflow.

ML models, such as AlphaFold and ESMFold, have achieved remarkable accuracy in predicting protein structures by learning from vast datasets of known sequences and structures [11] [44]. In contrast, evolutionary algorithms excel at navigating the vast sequence space to solve inverse problems, such as finding sequences that fold into a target structure or optimizing for stability and function [8]. The following sections synthesize quantitative performance data and detailed methodologies to equip researchers with the information needed to select the appropriate tool for their specific application.

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

Directly comparing ML and EA is complex, as they are often applied to different problems—structure prediction versus sequence design. However, by examining their performance on related tasks and their computational footprints, meaningful comparisons can be drawn. The table below summarizes key performance indicators for leading ML models and EA approaches.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of ML Prediction Models

| Model | Primary Application | Key Metric | Performance | Computational Load | Notable Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 2/3 [45] [11] [12] | Protein Structure & Complex Prediction | Global Distance Test (GDT) | >90 GDT on most CASP14 targets [11] | High (Requires significant GPU memory) [4] | Atomic accuracy; predicts complexes with ligands, DNA, RNA [45] |

| ESMFold [4] | Protein Structure Prediction | Predicted LDDP (pLDDT) | pLDDT >90 on some targets; variable on longer sequences [4] | Medium (Faster than AlphaFold, but high memory use) [4] | Very fast prediction; does not require multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) |

| OmegaFold [4] | Protein Structure Prediction | pLDDT | High pLDDT on short sequences (<400 aa) [4] | Medium (More efficient GPU use than ESMFold) [4] | Balanced speed, accuracy, and resource efficiency for shorter sequences |

| Boltz 2 [45] | Structure & Binding Affinity Prediction | Pearson Correlation (Affinity) | Pearson ~0.62 for binding affinity (comparable to FEP) [45] | High (with Boltz-steering for physical plausibility) [45] | Approaches FEP accuracy for binding affinity; 1000x more efficient [45] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Evolutionary Algorithm Approaches for Protein Design

| Aspect | Description | Performance & Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function [8] | Inverse Protein Folding Problem (IFP) | Finds sequences that fold into a defined structure. |

| Algorithm Example [8] | Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) | Optimizes for secondary structure similarity and sequence diversity simultaneously. |

| Key Strength [8] | Diversity Preservation | Searches deeper in sequence solution space, finding highly dissimilar sequences for the same structure. |

| Validation [8] | Tertiary Structure Prediction | Generated sequences are validated by predicting their 3D structure and comparing it to the original target. |

| Limitation | Relies on Predictive Tools | Dependent on fast, approximate structure predictors (like ML models) during optimization for feasibility [8]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A clear understanding of the underlying methodologies is crucial for their practical application and critical evaluation. This section details the standard protocols for both ML-based prediction and EA-driven design.

Protocol for ML-Based Protein Structure Prediction

The workflow for models like AlphaFold and ESMFold is largely automated but follows a consistent pipeline [11] [44].

- Input Preparation: The user provides the amino acid sequence of the target protein in FASTA format.

- Homology Search (MSA Generation): For models requiring it (e.g., AlphaFold), the first step is to search genetic databases to find homologous sequences and construct a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA). This step is bypassed in single-sequence methods like ESMFold [44].

- Neural Network Inference: The sequence (and MSA) is fed into the pre-trained deep learning model.

- Output and Confidence Estimation: The model outputs a 3D structure file (e.g., PDB format) alongside a per-residue confidence score (pLDDT), which estimates the local accuracy of the prediction [11].

Protocol for Evolutionary Algorithm-Based Protein Design

The EA workflow for the Inverse Folding Problem is an iterative optimization process [8].

- Problem Definition: The target protein structure (secondary or tertiary) is defined as the goal for the design process.

- Initialization: An initial population of random or seed-based amino acid sequences is generated.

- Fitness Evaluation: Each sequence in the population is evaluated using one or more fitness functions. A common multi-objective approach includes:

- Objective 1 (Similarity): Predicting the secondary structure of the generated sequence and measuring its similarity to the target secondary structure.

- Objective 2 (Diversity): Measuring the sequence diversity within the population to encourage exploration of the solution space [8].