Beyond Best Hits: Advanced Strategies to Reduce False Positives in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Classification

Accurate identification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) is critical for combating the global antimicrobial resistance crisis.

Beyond Best Hits: Advanced Strategies to Reduce False Positives in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Classification

Abstract

Accurate identification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) is critical for combating the global antimicrobial resistance crisis. However, traditional bioinformatics methods relying on high-identity sequence alignments often produce false negatives and fail to detect novel variants, creating significant gaps in resistome surveillance. This article explores the evolution of ARG classification, from the limitations of foundational alignment-based tools to the emergence of sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) and hybrid models designed to minimize false positives. We provide a comprehensive analysis of current methodologies, including deep learning, protein language models, and innovative database curation, and offer a practical framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select, optimize, and validate ARG detection tools for genomic and metagenomic data. By integrating troubleshooting guidance and comparative performance metrics, this resource aims to empower more precise ARG profiling in clinical, environmental, and One Health contexts.

The False Positive Problem: Why Traditional ARG Classification Fails

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main types of misclassification in ARG detection? The two primary types are false positives (classifying a non-ARG as a resistance gene) and false negatives (failing to identify a true ARG). Traditional alignment-based methods, which rely on sequence similarity thresholds, are particularly prone to both. Setting thresholds too high leads to false negatives by missing divergent ARGs, while setting them too low increases false positives by capturing non-ARG homologs [1] [2].

Why is reducing false positives so critical for public health and drug development? False positives can lead to significant resource misallocation. In public health surveillance, they can trigger unnecessary alerts and flawed estimates of resistance gene abundance, misguiding policy. In drug development, they can derail research by misdirecting efforts toward non-existent resistance mechanisms, wasting precious time and funding in the race against superbugs [3] [4].

How do AI models help reduce false positives compared to traditional methods? AI models, particularly deep learning, move beyond simple sequence similarity. They learn complex, discriminative patterns from vast datasets of known ARGs and non-ARGs. This allows them to identify remote ARG homologs that traditional methods would miss (reducing false negatives) while better distinguishing between true ARGs and non-ARG sequences with superficial similarity (reducing false positives) [1] [2] [5].

What is a key limitation of current AI models for ARG classification? A major challenge is their performance with limited or imbalanced training data. When certain ARG classes have few training examples, deep learning models can perform poorly. In such cases, alignment-based scoring can sometimes outperform a pure AI approach, highlighting the need for hybrid solutions [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Reducing False Positives

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data & Training | Model performance is poor for ARG classes with few samples. | Use hybrid models (e.g., ProtAlign-ARG) that leverage AI but default to alignment-based scoring for low-confidence predictions [2]. |

| The model struggles to distinguish ARGs from non-ARG homologs. | Integrate multimodal data like protein secondary structure and solvent accessibility (e.g., MCT-ARG) to provide more biological context than sequence alone [5]. | |

| Methodology & Tools | Traditional BLAST-based methods yield too many false positives. | Employ a tool like DeepARG, which uses a deep learning model to achieve high precision (>0.97) and recall, offering a better balance than strict cutoffs [1]. |

| Uncertainty in whether a predicted ARG is on a mobile plasmid. | Use tools that predict ARG mobility. For example, ProtAlign-ARG includes a dedicated model for identifying if an ARG is likely located on a plasmid [2]. | |

| Validation | Need to confirm the function of a novel ARG identified by an AI model. | Conduct interpretability analysis (e.g., with MCT-ARG) to see if the model's attention aligns with known functional residues, then validate with in vitro experiments [5]. |

Performance Comparison of ARG Identification Tools

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of several advanced tools as reported in the literature, providing a basis for selection.

| Tool | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepARG [1] | Deep Learning | Precision: >0.97, Recall: >0.90 | A robust general-purpose tool for identifying both known and novel ARGs from metagenomic reads. |

| MCT-ARG [5] | Multi-channel Transformer | AUC-ROC: 99.23%, MCC: 92.74% | High-accuracy classification and gaining mechanistic insight via interpretability analysis. |

| ProtAlign-ARG [2] | Hybrid (Protein Language Model + Alignment) | Excels in Recall | Scenarios with limited data or a need to minimize false negatives without sacrificing accuracy. |

| BlaPred [4] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Accuracy: 82-97% (for β-lactamases) | Specific, fast classification of β-lactamase ARG types. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Hybrid ARG Detection Workflow

This protocol is based on the ProtAlign-ARG pipeline and is designed to maximize accuracy while minimizing false positives [2].

1. Data Curation and Partitioning

- Objective: Create a high-quality, non-redundant dataset for training and testing.

- Steps:

- Source Data: Curate ARG sequences from comprehensive databases like HMD-ARG-DB, which consolidates data from CARD, ResFinder, DeepARG, and others.

- Non-ARG Set: Download non-ARG sequences from UniProt. Align them against your ARG database using DIAMOND BLAST. Classify sequences with an e-value > 1e-3 and percentage identity < 40% as non-ARGs. This stringent process ensures the model learns to distinguish challenging homologs.

- Data Partitioning: Use GraphPart (instead of traditional tools like CD-HIT) to partition data into training and testing sets with a strict similarity threshold (e.g., 40%). This prevents data leakage and ensures the model is tested on truly novel sequences, giving a realistic performance estimate.

2. Model Training and Prediction

- Objective: Train a model that leverages the strengths of both deep learning and alignment.

- Steps:

- Framework: Implement a hybrid framework with four dedicated models for (1) ARG Identification, (2) ARG Class Classification, (3) ARG Mobility Identification, and (4) ARG Resistance Mechanism.

- Process: For a given query protein sequence, the model first uses a pre-trained protein language model to generate embeddings and make a prediction. It assesses its own confidence in this prediction.

- Hybrid Decision: If the confidence is below a predefined threshold, the pipeline automatically defaults to an alignment-based scoring method (using bit scores and e-values against a curated database) to classify the ARG.

3. Validation and Interpretation

- Objective: Biologically validate predictions and understand the model's reasoning.

- Steps:

- Interpretability: For deep learning models like MCT-ARG, use built-in interpretability analyses to visualize which residues the model attended to most. Check if these align with known catalytic motifs or active sites from literature [5].

- Experimental Validation: Select a subset of novel, high-confidence ARG predictions for in vitro validation. Clone the gene into a susceptible bacterial strain and test its ability to confer resistance to the corresponding antibiotic.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in ARG Research |

|---|---|

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) | A curated repository of ARGs, antibiotics, and resistance mechanisms used as a gold-standard reference for alignment and validation [2]. |

| HMD-ARG-DB | A large, integrated database compiled from seven major sources, useful for training comprehensive AI models and benchmarking [2]. |

| DeepARG-DB | An ARG database developed alongside the DeepARG tool, populated with high-confidence predictions to expand the repertoire of known ARGs [1]. |

| DIAMOND | A high-throughput BLAST-compatible alignment tool used for rapidly comparing DNA or protein sequences against large databases [1] [2]. |

| GraphPart | A data partitioning tool that guarantees a specified maximum similarity between training and testing datasets, crucial for rigorous model evaluation [2]. |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Model (e.g., from ProtAlign-ARG) | A model pre-trained on millions of protein sequences to understand evolutionary patterns, used to generate informative embeddings for ARG classification [2]. |

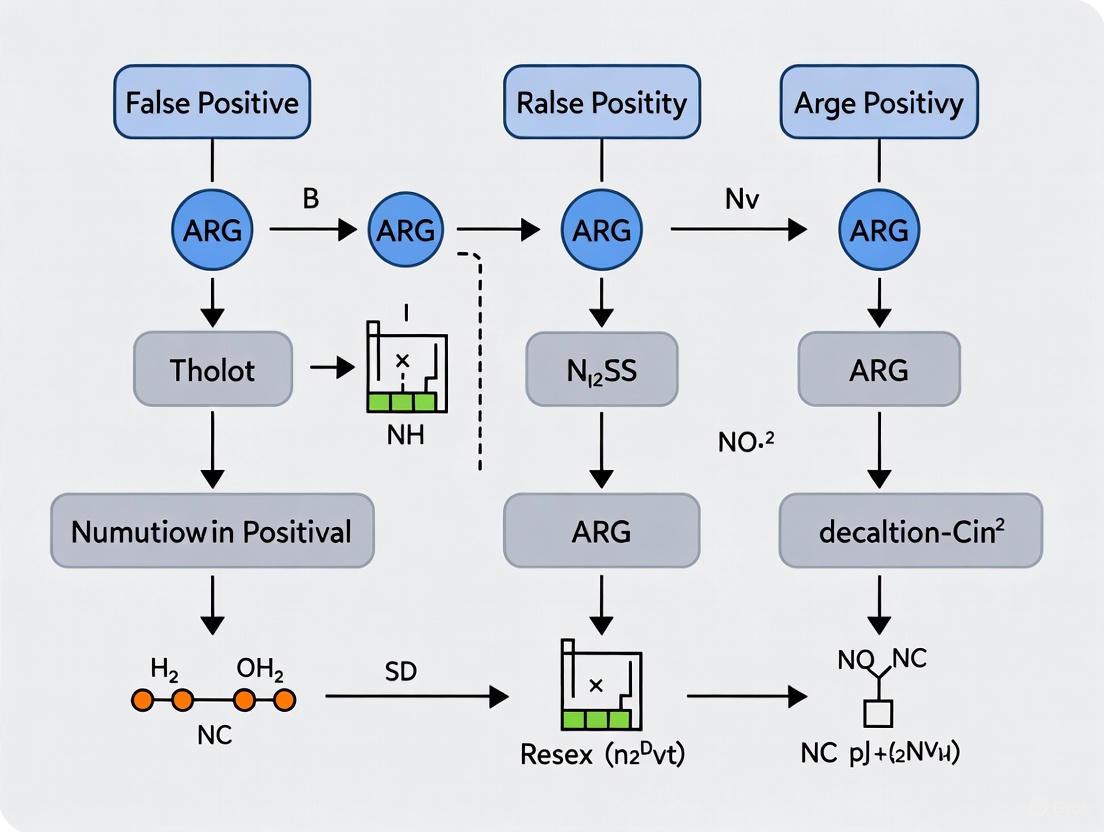

ARG Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a hybrid ARG identification process, designed to minimize false positives.

Multimodal Data Integration for ARG Classification

Advanced models like MCT-ARG integrate multiple data channels to improve accuracy, as shown in this workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the fundamental limitations of alignment-based methods for ARG classification? Alignment-based methods fundamentally rely on sequence similarity to identify genes by comparing query sequences against reference databases using tools like BLAST or DIAMOND [6]. Their core limitations are an inability to detect novel or divergent ARGs and a high sensitivity to user-defined parameters. These methods lack the ability to identify genes that are functionally related but have significantly diverged in their sequence, a task that emerging deep learning models are now designed to address [2] [7].

2. How does the "best hit" approach contribute to false negatives? The "best hit" approach requires a query sequence to find a highly similar match in a reference database to be annotated. This creates a high false negative rate because a large number of actual ARGs are predicted as non-ARGs when they lack a close homolog in the database [8]. This is particularly problematic for discovering new or emerging resistance genes that are not yet cataloged [2].

3. What problems arise from using stringent similarity cutoffs? Stringent similarity cutoffs, while reducing false positives, inevitably increase false negatives by excluding sequences with lower identity that are still bona fide ARGs [9] [10]. Furthermore, there is no globally accepted standard for these cut-offs, leading to inconsistencies across studies. Setting thresholds is ambiguous—too stringent leads to missed genes, while too liberal introduces false positives [2].

4. Can these methods detect ARGs with low sequence similarity to known genes? No, this is a primary weakness. Alignment-based tools are highly effective for known and highly conserved ARGs but perform poorly on sequences with low identity scores [9]. One study quantified this, showing that for sequences with no significant alignment (identity ≤50%), traditional BLAST failed entirely (precision: 0.0000), while modern machine learning tools could still achieve a precision of over 0.45 [9].

5. Why do alignment-based methods struggle with metagenomic data? Metagenomic data often consists of short, fragmented reads from complex microbial communities. Assembly-based approaches to overcome this are computationally intensive and time-consuming [10]. Even after assembly, short-read contigs are often too fragmented to reliably span the full genetic context of an ARG, making accurate classification difficult [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Negative Rates in Novel ARG Discovery

Problem: Your experiment is failing to detect potential novel or divergent antibiotic resistance genes, leading to an incomplete resistome profile.

Solution: Implement a hybrid or machine learning-based workflow.

- Root Cause: The alignment-based tool and database you are using lack the necessary sequences for comparison, and the similarity thresholds are filtering out true positives with remote homology [2] [6].

- Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Supplement Your Analysis: Run your sequences alongside your standard alignment-based tool (e.g., RGI, ResFinder) with a deep learning tool such as ProtAlign-ARG, PLM-ARG, or DeepARG [2] [7] [6].

- Compare Results: Create a Venn diagram to visualize the overlap and unique calls from each method.

- Prioritize Novel Candidates: Genes identified only by the machine learning tool are strong candidates for being novel or divergent ARGs.

- Validate Findings: Where possible, use functional metagenomics or other experimental assays to confirm resistance phenotypes for these candidate genes [6].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results Due to Parameter Sensitivity

Problem: Slight changes in alignment parameters (e-value, identity, coverage) lead to significant variations in the number and type of ARGs identified.

Solution: Adopt a standardized, pre-validated pipeline and database.

- Root Cause: Manual optimization of parameters like e-value and percentage identity is prone to user bias and can yield non-reproducible results [10].

- Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Use Pre-defined Parameters: Choose tools that come with built-in, validated thresholds instead of setting your own. For example, the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) against the CARD database uses pre-computed BLASTP bit-score thresholds [6].

- Select a Consolidated Database: To improve coverage, use a consolidated database like SARG+ or HMD-ARG-DB that integrates multiple sources, reducing the chance of missing a gene due to database-specific curation rules [2] [11].

- Benchmark Your Settings: If manual parameter setting is unavoidable, use a benchmark dataset with known ARGs to calibrate your cut-offs for an optimal balance between precision and recall [9].

Issue 3: Inability to Resolve Host Organisms for ARGs in Complex Metagenomes

Problem: You can detect ARGs in an environmental sample, but you cannot confidently assign them to their host species, limiting ecological insights.

Solution: Leverage long-read sequencing technologies and advanced binning tools.

- Root Cause: Short-read sequences are often too fragmented to link an ARG to other genomic markers of its host organism in a complex metagenomic background [11].

- Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Switch to Long-Read Sequencing: Use platforms like Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) or PacBio to generate sequencing reads that are thousands of bases long [11].

- Use Host-Resolving Tools: Analyze the data with tools like Argo or workflows that leverage long-read overlapping and clustering. These methods can span the full ARG and its flanking regions, which often contain genes that allow for confident taxonomic assignment [11].

- Context is Key: A long read that contains both an ARG and a conserved single-copy marker gene (e.g., 16S rRNA) provides direct evidence for the host species, overcoming the limitations of short-read assembly [11].

Performance Comparison of ARG Identification Methods

The table below summarizes quantitative data on the performance of different ARG identification methods, highlighting the weakness of alignment-based approaches with divergent sequences.

Table 1: Performance comparison of ARG classification methods across different sequence identity levels. [9]

| Method | Type | No Significant Alignment | Identity ≤50% | Identity >50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST Best Hit | Alignment-based | 0.0000 | 0.6243 | 0.9542 |

| DIAMOND Best Hit | Alignment-based | 0.0000 | 0.5740 | 0.9534 |

| HMMER | Alignment-based | 0.0563 | 0.2751 | 0.6051 |

| DeepARG | Machine Learning | 0.0000 | 0.5266 | 0.9419 |

| TRAC | Machine Learning | 0.3521 | 0.6124 | 0.9199 |

| ARG-SHINE | Ensemble ML | 0.4648 | 0.6864 | 0.9558 |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Your ARG Classification Pipeline

This protocol helps you quantitatively evaluate the false negative rate of your current alignment-based method.

Objective: To determine the proportion of known ARGs your workflow misses by testing it on a dataset where ground truth is known. Materials:

- Benchmark dataset (e.g., COALA dataset [9] or a customized set from HMD-ARG-DB [2])

- Your standard alignment-based classification pipeline (e.g., RGI, ResFinder)

- A comparative machine learning tool (e.g., PLM-ARG [7], ARG-SHINE [9])

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Download a curated ARG dataset and partition it using a tool like GraphPart to ensure training and testing sequences have less than 40% similarity, mimicking the challenge of detecting novel variants [2].

- Run Alignment-Based Prediction: Use your standard pipeline (with its typical parameters) to predict ARGs in the testing set.

- Run ML-Based Prediction: Run the same testing set through a selected machine learning tool using its default parameters.

- Result Comparison:

- Calculate the sensitivity (recall) of each method against the ground truth labels.

- Identify sequences that were correctly identified by the ML tool but missed by the alignment-based tool—these represent your pipeline's "false negatives."

- Analysis: The size and characteristics of the false-negative set will reveal the limitations of your current method and help justify the adoption of more sensitive tools.

Methodology Workflow: From Traditional to Modern ARG Classification

The following diagram illustrates the core limitations of the traditional alignment-based pathway and contrasts it with the enhanced capabilities of modern machine learning-based approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key computational tools and databases for advanced ARG classification research.

| Name | Type | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) [6] | Curated Database | A rigorously curated resource using the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) to classify resistance determinants; often used with the RGI tool. |

| SARG+ [11] | Consolidated Database | A manually curated compendium expanding CARD, NDARO, and SARG to include ARG variants from diverse species, improving sensitivity for long-read metagenomics. |

| HMD-ARG-DB [2] | Consolidated Database | One of the largest ARG repositories, curated from seven source databases, used for training and benchmarking comprehensive prediction models. |

| ProtAlign-ARG [2] | Hybrid Prediction Tool | A novel model combining a pre-trained protein language model with alignment-based scoring to improve accuracy, especially for remote homologs. |

| PLM-ARG [7] | ML Prediction Tool | An AI-powered framework using the ESM-1b protein language model and XGBoost to identify ARGs and their resistance categories with high accuracy. |

| ARG-SHINE [9] | Ensemble ML Tool | Utilizes a Learning to Rank (LTR) approach to ensemble three component methods (sequence homology, protein domains, raw sequences) for improved classification. |

| Argo [11] | Taxonomic Profiler | A bioinformatics tool that uses long-read overlapping to identify and quantify ARGs in complex metagenomes at the species level, enabling precise host-tracking. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does my ARG analysis produce different results when I use different databases? Different antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) databases vary fundamentally in their structure, content, and curation standards, leading to inconsistent results [12] [6]. Key differences include:

- Curation Methodology: Databases can be manually curated (e.g., CARD, ResFinder) or consolidated from multiple sources (e.g., NDARO, ARGminer). Manual curation offers high quality but may update slowly, while consolidated databases offer broader coverage but can suffer from redundancy and inconsistent annotations [12] [6].

- Scope of Resistance Determinants: Some databases focus exclusively on acquired resistance genes (e.g., ResFinder), others on chromosomal mutations (e.g., PointFinder), and some include both (e.g., CARD, NDARO) [12] [6]. If your analysis targets only one type, using a database that covers another will yield false negatives.

- Coverage and Annotation: The number of genes, the depth of associated metadata (e.g., resistance mechanism, mobile genetic element association), and the logical organization (e.g., CARD's use of the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology) differ significantly [12].

FAQ 2: What is the relationship between sequence homology and ARG function, and why is it a source of error? Sequence homology, inferred from statistically significant sequence similarity, indicates a common evolutionary ancestor but does not guarantee identical function [13] [14].

- Homology vs. Function: A gene detected via homology may be an intrinsic gene with a primary function other than antibiotic resistance [14]. For example, many efflux pumps have native roles in bacterial physiology and only confer resistance when overexpressed [14]. Relying solely on homology can therefore lead to false positives where a gene is annotated as an ARG despite not conferring a resistant phenotype in its native context [14] [6].

- Statistical Significance: Homology is inferred from alignment scores (BLAST, FASTA) and their associated E-values. An E-value represents the number of times a score would occur by chance, and this value depends on database size. The same alignment score will be less significant in a larger database [13]. This complexity means that without careful statistical thresholds, homology searches can produce both false positives and false negatives [15] [16].

FAQ 3: How can I detect novel or highly divergent ARGs that are missed by alignment-based methods? Traditional alignment-based methods (e.g., BLAST) rely on sequence similarity to known references and fail when ARGs are too divergent [2] [15]. Machine learning and deep learning approaches address this by learning patterns from the entire ARG diversity.

- The Limitation of Cutoffs: Alignment-based tools often use strict identity cutoffs (e.g., 80-90%) to minimize false positives, but this comes at the cost of a high false negative rate, missing genuine ARGs with low sequence identity (e.g., 20-60%) to known references [15].

- The Machine Learning Solution: Tools like DeepARG use deep learning models that consider the similarity distribution of sequences across the entire ARG database, rather than just the "best hit." This allows them to detect remote homologs and novel ARG variants with high precision and recall [15].

- Emerging Hybrid Methods: Newer approaches like ProtAlign-ARG combine the power of pre-trained protein language models (which can learn complex patterns from unannotated protein sequences) with traditional alignment-based scoring. This hybrid method improves accuracy, especially for classifying ARGs when training data is limited [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High False Positive Rates in ARG Predictions

| Potential Cause | Solution | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Detection of intrinsic genes with non-resistance functions [14]. | Implement the ARG-MOB scale or check for association with Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) [14]. | Genes co-located with plasmids, insertion sequences (IS), or integrons are more likely to be mobilized and confer resistance. One study found 80% of β-lactamase classes have rarely been mobilized [14]. |

| Overly sensitive homology thresholds [2]. | Apply stricter E-value and bit-score thresholds. Use manually curated databases like CARD with built-in scoring thresholds (e.g., RGI tool) [6]. | Curated databases and optimized thresholds filter out spurious, non-significant alignments that do not represent true homology or resistance function. |

| Use of a single, overly broad database. | Use a combination of databases and cross-validate predictions, prioritizing those confirmed by multiple rigorous resources [12] [17]. | Different databases have unique biases. Corroborating evidence from multiple sources increases confidence in a prediction. |

Issue: High False Negative Rates (Missing Known ARGs)

| Potential Cause | Solution | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Stringent sequence identity cutoffs [15]. | Use tools with more sensitive models, such as DeepARG or HMD-ARG, that do not rely on strict cutoffs [15] [6]. | These tools are designed to identify distant homologs and novel ARGs by learning from the full distribution of ARG sequences. |

| Using a DNA:DNA search instead of a protein-based search [13]. | For divergent sequences, use translated search (e.g., BLASTX) against protein databases [13]. | Protein alignments have a much longer "evolutionary look-back time" and are far more sensitive for detecting distant homology than DNA:DNA alignments [13]. |

| The database used lacks coverage of the specific ARG variant or class [12]. | Supplement your analysis with a consolidated database like ARGminer or NDARO, or use a machine learning-based tool [12] [15]. | Consolidated databases aggregate content from multiple sources, providing wider coverage. ML tools can infer ARGs beyond known sequences. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing ARG Mobility and Decontextualization Using the ARG-MOB Scale

Purpose: To prioritize ARG predictions based on their association with Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs), thereby reducing false positives from intrinsic, chromosomal genes [14].

- ARG Identification: Identify ARGs in your whole genome or metagenome-assembled genome using a tool of your choice (e.g., RGI, ResFinder).

- Context Analysis: For each identified ARG, examine its genetic context for the following MGEs:

- Plasmids: Determine if the ARG is located on a plasmid contig.

- Insertion Sequence (IS) Elements: Check for IS elements within a 10 kb window of the ARG.

- Integrons: Screen for integron-integrase genes and associated gene cassettes near the ARG.

- Mobility Scoring (ARG-MOB): Classify each ARG based on its MGE associations:

- High MOB: ARG is found on a plasmid AND associated with an IS element or integron.

- Medium MOB: ARG is found on a plasmid OR associated with an IS element/integron.

- Low MOB: ARG is chromosomal with no detected associations with the MGEs listed above.

- Interpretation: Prioritize ARGs with High and Medium MOB scores for further analysis, as these pose a more concrete risk for horizontal transfer and expression leading to phenotypic resistance [14].

Protocol 2: A Hybrid Machine Learning and Alignment Workflow for Novel ARG Detection

Purpose: To leverage the strengths of both deep learning and alignment-based methods for comprehensive ARG detection, as exemplified by ProtAlign-ARG [2].

- Data Preparation & Partitioning:

- Curate a set of ARG sequences from databases like HMD-ARG-DB.

- Use GraphPart (not CD-HIT) to partition data into training and testing sets at a specific similarity threshold (e.g., 40%). GraphPart guarantees no sequences in the training and testing sets exceed the threshold, preventing biased performance metrics [2].

- Model Training & Prediction:

- Path A - Protein Language Model (PPLM): Feed protein sequences into a pre-trained PPLM (e.g., from ProtAlign-ARG) to generate embeddings and perform initial ARG identification/classification [2].

- Path B - Alignment-Based Scoring: For sequences where the PPLM lacks confidence, perform a diamond alignment against a reference ARG database. Extract bit scores and E-values for classification [2].

- Hybrid Integration:

- Combine the predictions from both paths based on a confidence metric. The final output is a robust classification that benefits from the pattern recognition of deep learning and the statistical grounding of sequence alignment [2].

Below is a workflow diagram summarizing this hybrid approach:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key databases and computational tools essential for ARG detection and characterization.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARD [12] [6] | Manually Curated Database | Reference database for ARGs and resistance ontology. | High-quality, experimentally validated data. Includes RGI tool. May be slower to include novel genes [6]. |

| ResFinder/PointFinder [12] [6] | Manually Curated Database & Tool | Detects acquired ARGs (ResFinder) and chromosomal mutations (PointFinder). | Excellent for tracking known, acquired resistance genes and specific mutations in pathogens [6]. |

| DeepARG [15] [6] | Machine Learning Tool & Database | Predicts ARGs from sequence data using a deep learning model. | Excels at finding novel/divergent ARGs; lower false negative rate than strict alignment tools [15]. |

| HMD-ARG-DB [2] | Consolidated Database | Large repository consolidating ARGs from seven source databases. | Used for training and benchmarking machine learning models due to its comprehensive coverage [2]. |

| ProtAlign-ARG [2] | Hybrid Machine Learning Tool | Identifies and classifies ARGs by combining protein language models and alignment scoring. | Addresses limitations of both pure alignment and pure ML models, especially with limited data [2]. |

| ARGminer [12] | Consolidated Database | Ensemble database built from multiple ARG resources using crowdsourcing. | Broad coverage due to data integration; annotations may be less consistent than in manually curated databases [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My alignment-based tool fails to detect potential ARGs in my metagenomic data. What are the main limitations of this approach?

Traditional alignment-based methods rely on comparing sequences to existing reference databases. Their limitations, which can lead to missed detections, are summarized in the table below [2] [6].

Table: Key Limitations of Alignment-Based ARG Detection

| Limitation | Impact on ARG Detection |

|---|---|

| Inability to detect remote homologs/novel variants | High false-negative rate for ARGs that have significantly diverged from reference sequences [2]. |

| Dependence on existing database completeness | Cannot identify ARGs not yet catalogued in the database, missing emerging threats [2] [6]. |

| High computational time | Alignment against large databases can require hours to days for terabyte-sized datasets [2]. |

| Sensitivity to similarity thresholds | Stringent thresholds cause false negatives; liberal thresholds increase false positives [2]. |

Q2: How do modern computational tools like ProtAlign-ARG address the problem of false positives and negatives?

Tools like ProtAlign-ARG use a hybrid methodology to overcome the limitations of single-method approaches [2]. The workflow integrates a pre-trained protein language model (PPLM) with a traditional alignment-based scoring system. The PPLM uses deep learning to understand complex patterns and contextual relationships in protein sequences, which helps identify novel ARGs that alignment might miss. For cases where the deep learning model lacks confidence, the system defaults to a validated alignment-based method, using bit scores and e-values for classification. This combined approach has demonstrated superior accuracy and recall compared to tools that use only one method [2].

Q3: What are the practical differences between using CARD and a consolidated database like NDARO?

The choice of database significantly impacts your results. Key differences are outlined below [6].

Table: Comparison of Manually Curated and Consolidated ARG Databases

| Feature | CARD (Manually Curated) | NDARO (Consolidated) |

|---|---|---|

| Curation Method | Rigorous manual curation with strict inclusion criteria (e.g., experimental validation) [6]. | Integrates data automatically from multiple sources (e.g., CARD, ResFinder) [6]. |

| Data Quality | High accuracy and consistency due to expert review [6]. | Potential issues with consistency, redundancy, and annotation standards [6]. |

| Coverage | Deep coverage of well-characterized ARGs; may lack very recent discoveries [6]. | Broad coverage by aggregating data, potentially including more ARGs [6]. |

| Best Use Case | Studies requiring high-confidence identification of known ARGs [6]. | Large-scale screening where comprehensive coverage is a priority [6]. |

Q4: When using long-read sequencing for ARG host-tracking, what are the specific advantages of the Argo tool?

The Argo tool is specifically designed for long-read data and provides a major advantage in accurately linking ARGs to their host species. Unlike methods like Kraken2 or Centrifuge that assign taxonomy to each read individually, Argo uses a read-overlapping approach. It clusters overlapping reads and assigns a taxonomic label collectively to the entire cluster. This method substantially reduces misclassification errors, which is critical because ARGs are often located on mobile genetic elements that can be shared across different species [11].

Argo Workflow for Host-Tracking

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent ARG annotations when using different databases or tools.

- Potential Cause: Variations in database curation, annotation standards, and underlying algorithms.

- Solution:

- Always document the database name, version, and tool parameters used.

- For critical validations, use a consensus approach by running your data against multiple curated databases (e.g., CARD and ResFinder).

- Manually inspect the alignment results for key ARGs to understand the source of discrepancy [6].

Problem: Protein language model (e.g., in ProtAlign-ARG) performs poorly on a specific ARG class.

- Potential Cause: Insufficient or low-quality training data for that particular ARG class.

- Solution:

- Verify the distribution of ARG classes in your training data. Classes with few sequences are known to hamper model performance [2].

- In such cases, the hybrid nature of ProtAlign-ARG is beneficial. Check if the alignment-based scoring module provides a more reliable classification for that ARG class [2].

- If possible, supplement the training data with more sequences from consolidated databases like HMD-ARG-DB, which integrates data from seven source databases [2].

Problem: Difficulty in detecting ARGs that arise from point mutations rather than acquired genes.

- Potential Cause: General ARG databases like CARD may have limited coverage of resistance-conferring mutations, and the tools used may not be designed for this purpose.

- Solution:

- Incorporate specialized tools like PointFinder into your workflow, which are explicitly designed to identify chromosomal point mutations that confer resistance in specific bacterial species [6].

- Ensure you are using the correct reference genome for the organism you are studying when looking for mutations.

Table: Essential Resources for ARG Detection and Classification

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CARD [6] | Manually Curated Database | Reference of ARGs and resistance ontology using the ARO framework. | High-confidence identification of known, experimentally validated ARGs using tools like the RGI. |

| ResFinder/PointFinder [6] | Bioinformatics Tool & Database | Identifies acquired ARG genes (ResFinder) and chromosomal mutations (PointFinder). | Profiling acquired resistance and specific point mutations in bacterial genomes. |

| HMD-ARG-DB [2] | Consolidated Database | A large repository aggregating ARG sequences from multiple source databases. | Provides a broad set of sequences for training machine learning models like ProtAlign-ARG and HMD-ARG. |

| SARG+ [11] | Curated Database for Long-Reads | An expanded ARG database designed for read-based environmental surveillance. | Used with the Argo tool for enhanced sensitivity in identifying ARGs from long-read metagenomic data. |

| ProtAlign-ARG [2] | Hybrid Computational Tool | Integrates a protein language model and alignment scoring for ARG classification. | Reducing false negatives by detecting novel ARGs while maintaining confidence via alignment checks. |

| Argo [11] | Bioinformatics Profiler | A long-read analysis tool that uses read-clustering for taxonomic assignment. | Accurately tracking the host species of ARGs in complex metagenomic samples. |

ARG Identification Workflow Strategy

Next-Generation Solutions: AI and Hybrid Models for Precision ARG Detection

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing global health crisis, estimated to cause over 700,000 deaths annually worldwide [18] [2] [19]. Accurate identification of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) is crucial for understanding resistance mechanisms and developing mitigation strategies [6]. Traditional ARG identification methods rely on sequence alignment algorithms that compare query sequences against reference databases using tools like BLAST, Bowtie, or DIAMOND [19] [1]. These approaches typically employ strict similarity cutoffs (often 80-95%) to assign ARG classifications [20] [21] [6].

This dependency on high sequence similarity creates a fundamental limitation: while alignment-based methods maintain low false positive rates, they produce high false negative rates because they cannot identify novel or divergent ARGs that fall below similarity thresholds [6] [1]. This significant limitation means many actual ARGs in samples are misclassified as non-ARGs, leaving researchers with an incomplete picture of the resistome [20].

Deep learning approaches represent a paradigm shift in ARG identification. By learning statistical patterns and abstract features directly from sequence data rather than relying on direct sequence comparisons, tools like DeepARG and HMD-ARG can identify ARGs with little or no sequence similarity to known references, dramatically reducing false negative rates while maintaining high precision [18] [1].

Technical Deep Dive: How Deep Learning Models Minimize False Negatives

Core Architectural Differences from Traditional Methods

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow differences between traditional alignment-based methods and deep learning approaches for ARG identification:

DeepARG's Dissimilarity Matrix Approach

DeepARG introduced a fundamentally new approach to ARG identification by replacing similarity cutoffs with dissimilarity matrices and deep learning models. The framework consists of two specialized models: DeepARG-SS for short-read sequences and DeepARG-LS for full gene-length sequences [1].

Instead of relying on single best-hit comparisons, DeepARG uses a multilayer perceptron model that considers the similarity distribution of sequences across the entire ARG database. This allows it to detect ARGs that have statistically significant relationships to known resistance genes even when sequence identity falls well below traditional cutoff thresholds [1].

Key technical innovations in DeepARG include:

- Dissimilarity Matrix Processing: Creates a comprehensive similarity profile against all known ARG categories

- Neural Network Classification: Uses deep learning to identify complex patterns indicative of ARG function

- Expanded Database (DeepARG-DB): Incorporates manually curated ARGs from CARD, ARDB, and UNIPROT with reduced redundancy [1]

HMD-ARG's Hierarchical Multi-task Architecture

HMD-ARG advances the field further with an end-to-end hierarchical deep learning framework that provides comprehensive ARG annotations across multiple biological dimensions. The system employs convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that take raw sequence encoding (one-hot vectors) as input, automatically learning relevant features without manual feature engineering [18].

The hierarchical structure consists of three specialized levels:

- Level 0: Binary classification (ARG vs. non-ARG)

- Level 1: Multi-task prediction (antibiotic class, resistance mechanism, gene mobility)

- Level 2: Specialized beta-lactamase subclass identification [18]

This architecture enables HMD-ARG to not only identify ARGs with high accuracy but also provide detailed functional annotations that are valuable for understanding resistance mechanisms and transmission potential.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Evidence of False Negative Reduction

Statistical Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of ARG Identification Methods

| Method | Approach | Precision | Recall | False Negative Rate | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Alignment | Sequence similarity with strict cutoffs (>80-95%) | High (>0.95) | Low (~0.60-0.70) | High (30-40%) | Low false positives |

| DeepARG | Deep learning with dissimilarity matrices | >0.97 [1] | >0.90 [1] | Low (<10%) | Balanced precision and recall |

| HMD-ARG | Hierarchical multi-task CNN | High (Equivalent to ESM2) [20] | >0.90 [20] [21] | Low (<10%) | Comprehensive annotation capabilities |

| ProtAlign-ARG | Hybrid (Protein Language Model + Alignment) | High | Highest recall [2] | Lowest | Excels with limited training data |

Experimental Validation Results

Multiple independent studies have validated the superior performance of deep learning approaches for reducing false negatives:

- Cross-fold Validation: HMD-ARG demonstrated consistent performance across validation folds, maintaining recall values above 0.9 for most antibiotic classes [18]

- Third-party Dataset Validation: When applied to human gut microbiota datasets, both DeepARG and HMD-ARG identified significantly more ARGs compared to alignment-based tools [18]

- Functional Validation: Wet-lab experiments confirmed novel ARG predictions made by HMD-ARG, validating its ability to identify true positives that would be missed by traditional methods [18]

- Independent Benchmarking: Recent evaluations show deep learning tools achieve recall values >0.9 across all tested protein classes, significantly outperforming alignment-based approaches [20] [21]

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ARG Classification Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in ARG Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARG Databases | CARD [6], DeepARG-DB [1], HMD-ARG-DB [18], MEGARes [6] | Reference sequences for training and validation | Curated ARG collections with metadata |

| Non-ARG Datasets | SwissProt [20] [21], Uniprot (filtered) [2] | Negative controls for model training | Curated non-resistant proteins |

| Sequence Processing | DIAMOND [20], CD-HIT [1], GraphPart [2] | Data preprocessing and partitioning | Efficient sequence alignment and clustering |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow/Keras [20], PyTorch [19] | Model implementation and training | Flexible neural network development |

| Protein Language Models | ESM-1b [19], ProtBert-BFD [19] | Advanced feature extraction | Pre-trained on vast protein sequences |

| Evaluation Metrics | Recall, Precision, F1-score [1] | Performance assessment | Quantify false negative reduction |

Experimental Protocols for False Negative Assessment

Standard Benchmarking Protocol

To quantitatively assess false negative rates in ARG identification tools, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol:

Reference Dataset Curation:

- Select experimentally validated ARGs from CARD and other curated databases

- Artificially mutate sequences to create divergence series (5-95% identity)

- Combine with confirmed non-ARGs for balanced testing

Tool Configuration:

- Traditional aligners: Set identity cutoffs from 70-95%

- DeepARG: Use default parameters for either short-read or full-length modes

- HMD-ARG: Execute full hierarchical classification pipeline

Performance Quantification:

- Calculate recall: True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)

- Compare false negative rates across identity thresholds

- Statistical analysis of performance differences

Cross-Validation Methodology

For robust evaluation of deep learning models in reducing false negatives:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do traditional alignment methods produce so many false negatives?

Traditional methods rely on sequence similarity cutoffs (typically 80-95%) to identify ARGs. This approach fails to detect:

- Evolutionarily divergent ARGs that share functional domains but have low overall sequence identity

- Novel ARG variants not yet represented in reference databases

- Remote homologs where evolutionary relationships have significantly diverged over time [2] [6]

Deep learning models learn the underlying statistical patterns and functional domains that define ARGs, enabling identification based on abstract features rather than direct sequence similarity [18] [20].

Q2: How can DeepARG and HMD-ARG maintain low false positive rates while reducing false negatives?

These tools achieve this balance through several mechanisms:

- Comprehensive training on both ARG and non-ARG sequences, learning discriminative features

- Hierarchical classification (in HMD-ARG) that progressively refines predictions

- Dissimilarity matrix approaches (in DeepARG) that consider overall similarity distributions rather than single thresholds

- Multi-task learning that leverages correlated information across ARG properties [18] [1]

Resource requirements vary significantly:

- DeepARG: Moderate requirements, suitable for standard bioinformatics workstations

- HMD-ARG: Higher requirements due to complex CNN architecture, benefits from GPU acceleration

- Protein Language Models (ESM, ProtBert): Highest requirements, typically requiring dedicated GPUs with substantial memory [19]

For most research applications, a workstation with 16+ GB RAM, modern multi-core processor, and a mid-range GPU provides sufficient capability for practical implementation.

Q4: How do I handle data imbalance when training custom ARG classification models?

Several strategies have proven effective:

- Data augmentation techniques specifically designed for protein sequences [19]

- Strategic partitioning using tools like GraphPart to maintain representation across splits [2]

- Cross-referencing protein language models to enhance limited training data [19]

- Weighted loss functions that automatically adjust for class frequency [18]

Q5: Can these tools identify completely novel ARGs with no similarity to known sequences?

While no tool can guarantee perfect identification of completely novel ARGs, deep learning approaches significantly outperform traditional methods for this application. They can detect:

- Novel combinations of known functional domains and motifs

- Distant evolutionary relationships not apparent through sequence alignment

- Statistical patterns indicative of resistance function across diverse sequence types [22]

Experimental validation remains essential for confirming truly novel ARG predictions, but deep learning models provide the most promising leads for discovery.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low Recall Despite Using Deep Learning Models

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient training data diversity: Expand training set to include more divergent ARG sequences

- Improper data partitioning: Use GraphPart instead of CD-HIT for partitioning to ensure proper divergence between training and testing sets [2]

- Class imbalance: Implement data augmentation techniques specific to protein sequences [19]

Problem: High Computational Time for Large Metagenomic Datasets

Optimization Strategies:

- Sequence pre-filtering: Use fast alignment tools for initial screening before deep learning analysis

- Model simplification: Consider shallower architectures for initial screening with detailed analysis on subsets

- Hybrid approaches: Implement tools like ProtAlign-ARG that use alignment for high-confidence matches and deep learning for uncertain cases [2]

Problem: Interpretation of Model Predictions

Explainability Techniques:

- Feature importance analysis: Examine which sequence regions contribute most to predictions

- Domain mapping: Correlate important regions with known protein domains and motifs

- Activation pattern analysis: Visualize which neural network components respond to specific sequence features [20] [21]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key advantage of using a protein language model like ESM-1b for ARG identification over traditional BLAST?

Protein language models (PLMs) like ESM-1b, which contains 650 million parameters pre-trained on 250 million protein sequences, excel at capturing complex sequence-structure-function relationships that traditional alignment-based tools miss [7]. While BLAST and DIAMOND rely on sequence similarity and can produce high false-negative rates for remote homologs, PLMs use deep contextual understanding of protein sequences to identify ARGs that lack significant sequence similarity to known database entries [7]. This enables identification of novel ARGs that would otherwise be missed by alignment-based methods.

Q2: My model performs well on validation data but shows high false positives on real metagenomic samples. How can I improve specificity?

This is a common challenge when moving from curated datasets to complex real-world samples. ProtAlign-ARG addresses this through a hybrid approach: when the PLM lacks confidence in its prediction, it automatically employs an alignment-based scoring method that incorporates bit scores and e-values for classification [2]. Additionally, ensure your negative training dataset is properly curated by including challenging non-ARG sequences from UniProt that have some homology to ARGs (e-value > 1e-3 and identity < 40%), which forces the model to learn more discriminative features [2].

Q3: What are the computational requirements for implementing PLM-ARG, and are there optimized alternatives?

The full ESM-1b model with 650 million parameters requires significant computational resources for generating protein embeddings [7]. For resource-constrained environments, consider ARGNet which uses a more efficient deep neural network architecture that reduces inference runtime by up to 57% compared to DeepARG while maintaining high accuracy [23]. Alternatively, ProtAlign-ARG's hybrid approach provides computational efficiency by only using the PLM component when necessary, falling back to faster alignment-based methods for high-confidence matches [2].

Q4: How can I handle very short amino acid sequences (30-50 aa) from metagenomic reads?

Standard PLM-ARG and similar models are typically trained on full-length protein sequences. For short sequences, use ARGNet-S, which is specifically designed for sequences of 30-50 amino acids (100-150 nucleotides) using a specialized autoencoder and convolutional neural network architecture [23]. The model was trained with mini-batches containing mixed-length sequences to ensure robust performance on partial gene fragments commonly found in metagenomic data.

Q5: What integration strategies work best for combining multiple prediction approaches?

ARG-SHINE demonstrates an effective ensemble strategy using Learning to Rank (LTR) methodology, which integrates three component methods: ARG-CNN (raw sequence analysis), ARG-InterPro (protein domain/family/motif information), and ARG-KNN (sequence homology) [9]. This approach leverages the strengths of each method - homology-based methods excel with high-identity sequences, while deep learning methods perform better with novel sequences, resulting in superior overall performance across different similarity thresholds.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Performance on Sequences with Low Similarity to Database Entries

Problem: Your model fails to identify ARGs that have low sequence identity (<50%) to known resistance genes in reference databases.

Solution:

- Implement a hybrid model: Adopt ProtAlign-ARG's strategy that combines PLM embeddings with alignment-based scoring. The PLM handles remote homolog detection while alignment methods provide confidence scoring [2].

- Use ensemble methods: Deploy ARG-SHINE's framework that ensembles multiple approaches, which significantly outperforms single-method approaches on low-identity sequences (0.4648 accuracy vs 0.0000 for BLAST on sequences with no significant database hits) [9].

- Data augmentation: Apply the data augmentation techniques used in PLM-ARG, including training on subsequences of varying lengths (60-90% of full length) to improve model generalization [2].

Validation: Test your improved pipeline on the COALA dataset's low-identity partitions where ARG-SHINE achieved 0.4648 accuracy compared to BLAST's 0.0000 [9].

Issue: High False Positive Rates in Complex Metagenomic Samples

Problem: Your ARG classifier identifies numerous false positives when applied to real metagenomic datasets, reducing reliability for research conclusions.

Solution:

- Enhanced negative training set: Curate your non-ARG training set using Diamond alignment with HMD-ARG-DB, keeping sequences with e-value > 1e-3 and percentage identity < 40% as non-ARGs to create more challenging negative examples [2].

- Incorporate functional information: Integrate protein domain knowledge using ARG-InterPro, which scans for domains, families, and motifs then uses logistic regression for classification, adding biological plausibility to predictions [9].

- Confidence thresholding: Implement ProtAlign-ARG's confidence-based switching mechanism where low-confidence PLM predictions are verified with alignment-based methods [2].

Validation: Compare your false positive rate against ARG-SHINE's benchmark results showing weighted-average f1-score improvements over DeepARG and TRAC across multiple datasets [9].

Issue: Limited Training Data for Specific ARG Classes

Problem: Certain antibiotic resistance classes have few representative sequences (few-shot learning scenario), leading to poor classification performance.

Solution:

- Transfer learning: Utilize the pre-trained ESM-1b model from PLM-ARG which has learned general protein representations from 250 million sequences, then fine-tune on your specific ARG data [7].

- Hierarchical classification: For classes with insufficient data, use HMD-ARG's approach of grouping similar resistance mechanisms or employing a hierarchical model that shares representations across related classes [2].

- Data partitioning: Use GraphPart instead of CD-HIT for data splitting, as it provides exceptional partitioning precision and retains most sequences while ensuring proper separation between training and test sets [2].

Validation: ProtAlign-ARG demonstrated remarkable accuracy even on the 14 least prevalent ARG classes in HMD-ARG-DB through careful data partitioning and hybrid modeling [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Implementing a Hybrid PLM and Alignment ARG Classification System

Based on ProtAlign-ARG Methodology [2]

Data Curation

- Source ARG sequences from HMD-ARG-DB (contains >17,000 ARG sequences across 33 classes)

- Curate non-ARG sequences from UniProt by excluding known ARGs and aligning remaining sequences against HMD-ARG-DB

- Retain sequences with e-value > 1e-3 and identity < 40% as negative examples

Data Partitioning

- Use GraphPart tool with 40% similarity threshold for precise training/test separation

- Partition data into 80% training/validation and 20% testing sets

- Apply data augmentation using subsequences (60-90% of full length)

Model Architecture

- Generate protein embeddings using ESM-1b (1280-dimensional vectors from 32nd layer)

- Train XGBoost classifier on embeddings for initial prediction

- Implement confidence thresholding to identify low-confidence predictions

- Route low-confidence sequences to alignment-based scoring (bit-score and e-value)

- Combine results from both pathways for final classification

Validation

- Test on independent validation sets using COALA dataset (16,023 ARG sequences)

- Evaluate using Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and F1-score

- Compare against DeepARG, HMMER, and TRAC baselines

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across ARG Identification Tools

| Tool | Approach | MCC | Accuracy | Specialization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLM-ARG [7] | Protein Language Model (ESM-1b) + XGBoost | 0.838 (independent set) | N/A | General ARG identification |

| ProtAlign-ARG [2] | Hybrid PLM + Alignment | N/A | Superior recall vs. existing tools | Detection of novel variants |

| ARG-SHINE [9] | Ensemble (LTR) | N/A | 0.9558 (high identity) | Low-identity sequences |

| DeepARG [9] | Deep Learning + Similarity | N/A | 0.9419 (high identity) | Metagenomic data |

| ARGNet [23] | Autoencoder + CNN | N/A | Reduced runtime 57% | Variable length sequences |

Table 2: Performance on Sequences with Different Database Similarity [9]

| Method | No Hits (Accuracy) | ≤50% Identity (Accuracy) | >50% Identity (Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST Best Hit | 0.0000 | 0.6243 | 0.9542 |

| DeepARG | 0.0000 | 0.5266 | 0.9419 |

| TRAC | 0.3521 | 0.6124 | 0.9199 |

| ARG-CNN | 0.4577 | 0.6538 | 0.9452 |

| ARG-SHINE | 0.4648 | 0.6864 | 0.9558 |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Databases for ARG Classification

| Resource | Type | Description | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMD-ARG-DB [2] | Database | >17,000 ARG sequences from 7 databases | Comprehensive training and benchmarking data for model development |

| ESM-1b [7] | Protein Language Model | 650M parameters, pre-trained on 250M sequences | Generating contextual protein embeddings for sequence analysis |

| CARD [2] | Database | Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database | Reference database for alignment-based validation and scoring |

| COALA Dataset [9] | Benchmark Dataset | 17,023 ARG sequences from 15 databases | Standardized evaluation across different methods and approaches |

| GraphPart [2] | Tool | Data partitioning tool | Precise separation of training and test datasets with similarity control |

| InterProScan [9] | Tool | Protein domain/family/motif detection | Providing functional signatures for ensemble methods like ARG-SHINE |

Methodological Workflows

PLM-ARG Classification Pipeline

End-to-End Experimental Framework for ARG Classification

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when using the ProtAlign-ARG tool for antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) characterization. The guidance is framed within a research thesis focused on reducing false positives in ARG classification.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of ProtAlign-ARG over purely alignment-based methods for reducing false positives? ProtAlign-ARG's hybrid architecture directly addresses the limitation of alignment-based methods, which are highly sensitive to similarity thresholds and can yield false positives if thresholds are too liberal [2]. By leveraging a protein language model (PLM) to understand complex patterns, the model can better distinguish true ARGs from non-ARGs with some sequence homology, thereby enhancing generalizability and reducing false positive rates [2] [24].

Q2: How does ProtAlign-ARG handle sequences with low homology to the training data, a common source of false negatives? For sequences where the PLM lacks confidence, typically due to limited training data or low homology, ProtAlign-ARG automatically falls back to an alignment-based scoring method. This method uses bit scores and e-values to classify ARGs, ensuring robustness even when the deep learning model encounters unfamiliar patterns [2] [24].

Q3: What specific data partitioning method is recommended to avoid over-optimistic performance metrics? To prevent data leakage and ensure that training and testing sets are sufficiently distinct, the developers recommend using GraphPart over traditional tools like CD-HIT. GraphPart provides exceptional partitioning precision, guaranteeing that sequences in the training and testing sets do not exceed a specified similarity threshold (e.g., 40%), which leads to a more reliable evaluation of the model's performance on unseen data [2].

Q4: Beyond identification, what other functional characteristics can ProtAlign-ARG predict? ProtAlign-ARG comprises four distinct models for: (1) ARG Identification, (2) ARG Class Classification, (3) ARG Mobility Identification, and (4) ARG Resistance Mechanism prediction [2]. This allows researchers to gain comprehensive insights into the functionality and potential mobility of resistance genes, which is crucial for understanding their spread.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Suboptimal Performance on Novel ARG Variants

- Problem: The model shows low recall for ARG variants that are highly divergent from known sequences.

- Solution: This is where the hybrid architecture excels. The integrated pre-trained protein language model (PPLM) is designed to capture remote homologs and complex patterns missed by conventional alignment. Ensure you are using the full ProtAlign-ARG pipeline and not just its alignment-scoring component. The PLM's embeddings provide a more nuanced representation of protein sequences, improving detection of novel variants [2] [24].

- Reference Performance: In comparative evaluations, the PPLM component alone achieved a weighted F1-score of 0.97 on identification tasks, demonstrating its strong capability [24].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results Across Different ARG Classes

- Problem: Classification accuracy is high for common antibiotic classes but poor for less prevalent ones.

- Solution: This is often a result of class imbalance in the training data. ProtAlign-ARG was developed using HMD-ARG-DB, which contains 33 antibiotic-resistance classes. The developers addressed this by initially focusing on the 14 most prevalent classes for model development. For research targeting rare classes, consult the model's performance metrics on all 33 classes (available in Supplementary Table 7 of the original publication) to set realistic expectations. Retraining or fine-tuning the model on a dataset enriched for your target classes may be necessary [2].

Issue 3: Poor Distinction Between ARGs and Challenging Non-ARGs

- Problem: The model produces false positives by misclassifying non-ARG sequences that have some homology to known resistance genes.

- Solution: The non-ARG training set for ProtAlign-ARG was specifically curated to include sequences with an e-value > 1e-3 and percentage identity below 40% to ARGs in HMD-ARG-DB. This forces the model to learn subtle discriminative features. If false positives persist, validate results against the alignment-based scoring component as a sanity check. The hybrid model's decision logic is designed to improve precision in these edge cases [2] [24].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

ProtAlign-ARG was rigorously evaluated against other state-of-the-art tools and its own components. The following tables summarize key quantitative results.

Table 1: Macro-Average Performance on the COALA Dataset (16 classes)

| Model | Macro Precision | Macro Recall | Macro F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST (best hit) | - | - | 0.8258 |

| DIAMOND (best hit) | - | - | 0.8103 |

| DeepARG | - | - | 0.7303 |

| HMMER | - | - | 0.4499 |

| TRAC | - | - | 0.7399 |

| ARG-SHINE | - | - | 0.8555 |

| PPLM Model | - | - | 0.67 |

| Alignment-Score | - | - | 0.71 |

| ProtAlign-ARG | - | - | 0.83 |

Table 2: Internal Model Component Comparison

| Model | Metric | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPLM | Macro | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| Weighted | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| Alignment-Scoring | Macro | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.78 |

| Weighted | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | |

| ProtAlign-ARG | Macro | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.78 |

| Weighted | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

Detailed Methodology for Key Experiments

Experiment: Benchmarking against existing tools using the COALA dataset.

- Data Curation: The COALA dataset was used for this experiment. It was collected from 15 published ARG databases and comprises 17,023 ARG sequences across 16 drug resistance classes [2] [24].

- Data Partitioning: The dataset was partitioned into training and testing sets using a precise method like GraphPart to ensure a maximum sequence similarity threshold (e.g., 40%) between the sets, preventing biased performance metrics [2].

- Model Comparison: ProtAlign-ARG and other tools (BLAST, DIAMOND, DeepARG, HMMER, TRAC, ARG-SHINE) were run on the test set.

- Evaluation Metrics: Macro-average and weighted-average F1-scores were calculated to evaluate performance across all 16 antibiotic classes. The macro average gives equal weight to each class, making it a stringent metric for imbalanced datasets [24].

Experiment: Evaluating the hybrid model's components.

- Data Curation: The HMD-ARG-DB, integrating seven public databases, was used. It contains over 17,000 ARG sequences from 33 classes, though the model was primarily focused on 14 prevalent classes [2].

- Model Training: The three key components were trained and evaluated separately:

- The Pre-trained Protein Language Model (PPLM) using raw embeddings.

- The Alignment-Scoring model based on bit scores and e-values.

- The full ProtAlign-ARG hybrid model.

- Performance Analysis: Precision, Recall, and F1-Score (both macro and weighted) were computed for each component. The analysis demonstrated that the hybrid model successfully leveraged the strengths of both approaches, achieving high recall from the PPLM and robust precision from the alignment-scoring where needed [24].

Workflow and System Architecture Visualization

ProtAlign-ARG Hybrid Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Databases and Computational Tools for ARG Research

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| HMD-ARG-DB [2] [24] | Database | A large, integrated repository of ARGs curated from seven public databases; used for training and benchmarking models like ProtAlign-ARG. |

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) [2] [25] | Database | A widely used reference database for ARGs and antibiotics; often used as a gold standard for alignment-based methods. |

| COALA Dataset [2] [24] | Dataset | A comprehensive collection of ARGs from 15 databases; used for independent and comparative performance evaluation of ARG detection tools. |

| GraphPart [2] | Software Tool | A data partitioning tool used to create training and testing sets with a guaranteed maximum sequence similarity, preventing data leakage and overfitting. |

| Protein Language Model (e.g., ProtAlbert, ProteinBERT) [2] [25] | Computational Model | A deep learning model pre-trained on millions of protein sequences to generate contextual embeddings, enabling detection of remote homologs and novel variants. |

| DIAMOND [2] | Software Tool | A high-throughput sequence alignment tool used for fast comparison of sequencing reads against protein databases like HMD-ARG-DB. |

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a significant global health threat, directly responsible for an estimated 1.14 million deaths worldwide in 2021 alone. Effective surveillance of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) is critical for understanding and mitigating AMR's spread. While metagenomics has advanced our ability to monitor ARGs, traditional short-read sequencing struggles to accurately link ARGs to their specific microbial hosts—information indispensable for tracking transmission and assessing risk. The Argo computational tool represents a breakthrough approach that leverages long-read sequencing to provide species-resolved profiling of ARGs in complex metagenomes, significantly enhancing resolution while reducing false positives in ARG classification research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of Argo over traditional short-read methods for ARG profiling? Argo's primary advantage is its ability to provide species-level resolution when profiling antibiotic resistance genes in complex metagenomic samples. Unlike short-read methods that often produce fragmented assemblies and struggle to link ARGs to their specific microbial hosts, Argo leverages long-read sequencing to span entire ARGs along with their contextual genetic information, dramatically improving the accuracy of host identification and reducing false positive classifications [26].

Q2: How does Argo's clustering approach reduce false positives in host identification? Instead of assigning taxonomic labels to individual reads like traditional classifiers (Kraken2, Centrifuge), Argo uses a read-overlapping approach to build overlap graphs that are segmented into read clusters using the Markov Cluster (MCL) algorithm. Taxonomic labels are then determined on a per-cluster basis, substantially reducing misclassifications that commonly occur with per-read classification methods, especially for ARGs prone to horizontal gene transfer across species [26].

Q3: What are the key database requirements for running Argo effectively? Argo uses a manually curated reference database called SARG+, which compiles protein sequences from CARD, NDARO, and SARG databases. SARG+ is specifically expanded to include multiple sequence variants for each ARG across different species, addressing limitations of standard databases that might only include single representative sequences. Additionally, Argo uses GTDB (Genome Taxonomy Database) as its default taxonomy database due to its comprehensive coverage and better quality control compared to NCBI RefSeq [26].

Q4: How does Argo handle plasmid-borne versus chromosomal ARGs? Argo specifically marks ARG-containing reads as "plasmid-borne" if they additionally map to a decontaminated subset of the RefSeq plasmid database. The tool currently includes 39,598 plasmid sequences for this purpose. This differentiation is crucial for understanding ARG mobility and assessing transmission risk, as plasmid-borne ARGs can transfer horizontally between bacteria more readily than chromosomal ARGs [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low ARG Detection Sensitivity

Problem: Argo is detecting fewer ARGs than expected in samples known to contain antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Solutions:

- Verify the quality and length of input long reads; Argo performance improves with read length and quality

- Check that you're using the complete SARG+ database, which includes expanded ARG variants beyond standard databases

- Adjust the identity cutoff parameter, which Argo sets adaptively based on per-base sequence divergence from read overlaps

- Ensure your sequencing depth is sufficient for detecting low-abundance ARGs, particularly in complex environmental samples [26]

Issue 2: Incorrect Host Species Assignment

Problem: ARGs are being assigned to incorrect microbial hosts, compromising data reliability.

Solutions:

- Validate that the GTDB taxonomy database is properly installed and includes non-representative genomes for comprehensive coverage

- Examine read clustering parameters; poorly defined clusters can lead to incorrect taxonomic assignments

- Check for repetitive regions surrounding ARGs that might interfere with accurate overlap detection

- Confirm that read quality meets minimum requirements for reliable overlap graph construction [26]

Issue 3: High Computational Resource Consumption

Problem: Argo analysis is consuming excessive computational resources or time.

Solutions:

- Leverage Argo's preliminary filter that identifies ARG-containing reads using DIAMOND's frameshift-aware alignment, reducing downstream processing

- Optimize the cluster segmentation step by adjusting MCL algorithm parameters for your specific dataset complexity

- For large datasets, consider subsampling strategies to establish optimal parameters before full analysis

- Ensure sufficient memory is allocated for overlap graph construction, particularly for highly complex metagenomes [26]

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Argo Workflow for Species-Resolved ARG Profiling

The following diagram illustrates Argo's core workflow for processing long-read metagenomic data:

Protocol 1: Sample Processing and Sequencing for Argo Analysis

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect biomass samples (e.g., 1L wastewater, 50mL activated sludge) and preserve immediately on ice

- Concentrate biomass onto 0.22-μm membrane filters and preserve in 50% ethanol for transport

- Extract DNA using a commercial soil DNA extraction kit (e.g., FastDNA SPIN kit) suitable for diverse microbial communities

- Purify extracted DNA using a genomic DNA clean kit and quantify using fluorometric methods

- Verify DNA purity (target OD 260/230 = 2.0-2.2, OD 260/280 > 1.8) and check for degradation using gel electrophoresis or tape station analysis [27]

Library Preparation and Long-read Sequencing:

- Use ≥1000 ng DNA for library preparation with native barcoding kits (e.g., Oxford Nanopore SQK-LSK108)

- Fragment DNA mechanically (e.g., using g-Tube at 6000 rpm for 1 minute)

- Perform extended DNA end-repair incubation (30 minutes) to improve library preparation from complex environmental DNA

- Sequence using appropriate long-read platforms (Nanopore R9.0/R9.4 flow cells) with a minimum target of 0.6 million reads per sample after quality control [27]

Protocol 2: Argo Implementation and Database Setup

Software Installation and Database Configuration:

- Install Argo from the GitHub repository (xinehc/argo) along with dependencies including DIAMOND, minimap2, and MCL

- Download and configure the SARG+ database, which includes manually curated ARG sequences from CARD, NDARO, and SARG

- Set up the GTDB taxonomy database (release 09-RS220), including non-representative genomes for comprehensive coverage

- Configure the RefSeq plasmid database (39,598 sequences) for identifying plasmid-borne ARGs [26]

Analysis Execution and Parameter Optimization:

- Process base-called long reads through Argo's initial ARG identification using DIAMOND's frameshift-aware DNA-to-protein alignment

- Allow Argo to adaptively set identity cutoffs based on per-base sequence divergence from the first 10,000 reads

- Monitor read overlap graph construction and cluster segmentation using the MCL algorithm

- Validate results using positive controls or mock communities with known ARG-host associations [26]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Argo Analysis

| Reagent/Database | Function | Specifications | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARG+ Database | Reference ARG database for identification | 104,529 protein sequences organized in hierarchy; excludes regulators and housekeeping genes | Manually curated from CARD, NDARO, SARG [26] |

| GTDB Taxonomy | Taxonomic classification reference | 596,663 assemblies (113,104 species) from GTDB release 09-RS220 | Genome Taxonomy Database [26] |

| RefSeq Plasmid DB | Plasmid-borne ARG identification | 39,598 decontaminated plasmid sequences | NCBI RefSeq [26] |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Microbial DNA extraction | Bead-beating protocol for diverse communities | FastDNA SPIN kit for soil [27] |

| Library Prep Kit | Long-read sequencing | Native barcoding for multiplexing | Oxford Nanopore 1D native barcoding kit (SQK-LSK108) [27] |

Performance Benchmarking and Validation

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Argo Compared to Alternative Methods

| Method | Host Identification Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Sensitivity for Low-Abundance ARGs | False Positive Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argo | High (read-cluster approach) | Moderate (avoids assembly) | High (detects hosts at 1X coverage) | Low (cluster-based reduction) [26] |

| ALR Method | Moderate (83.9-88.9%) | High (44-96% faster) | High (1X coverage detection) | Moderate [28] |

| Assembly-Based | Variable (fragmentation issues) | Low (computationally intensive) | Limited (information loss) | Higher (misassemblies) [26] [28] |

| Correlation Analysis | Low (spurious correlations) | High | Limited | High (uncertain associations) [28] |

Advanced Technical Considerations

Addressing Horizontal Gene Transfer Challenges

ARGs present unique classification challenges due to their propensity for horizontal gene transfer between chromosomes and plasmids across different species. Argo's cluster-based approach specifically addresses this by grouping reads that originate from the same genomic region through overlap graph construction, rather than relying on single-read classifications that are more prone to misassignment when ARGs appear in multiple genetic locations across different species [26].

Optimization for Complex Environmental Samples