Beyond the D-Statistic: A Comparative Guide to Phylogenetic Networks for Detecting Reticulate Evolution

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and bioinformaticians between the widely used D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) and modern phylogenetic network methods for detecting reticulate evolution.

Beyond the D-Statistic: A Comparative Guide to Phylogenetic Networks for Detecting Reticulate Evolution

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and bioinformaticians between the widely used D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) and modern phylogenetic network methods for detecting reticulate evolution. We explore the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing their methodological applications, strengths, and limitations. A troubleshooting guide addresses common challenges like computational scalability and interpreting complex results. Through a direct performance comparison and validation framework, we demonstrate that while the D-statistic offers a fast initial screening tool, phylogenetic networks provide a more robust and detailed inference of evolutionary history, especially in complex scenarios involving multiple reticulations or ghost lineages. This synthesis empowers more accurate detection of hybridization and introgression in genomic studies, with significant implications for understanding evolutionary trajectories in pathogen and drug target research.

Core Concepts: From Tree Discordance to Explicit Reticulate Models

Phylogenetics, the study of evolutionary relationships, has long relied on trees as its primary representational framework. However, the increasing recognition of reticulate evolutionary processes—such as hybridization, horizontal gene transfer, and introgression—has exposed the limitations of strictly tree-like models. This recognition has driven the development and adoption of phylogenetic networks, which can model these complex histories [1]. Phylogenetic networks are broadly categorized into two distinct paradigms: implicit networks and explicit networks [2] [1] [3]. Understanding the fundamental differences between these classes, their appropriate applications, and their performance characteristics is crucial for researchers aiming to accurately reconstruct evolutionary histories in the presence of gene flow.

This guide provides a objective comparison between implicit and explicit phylogenetic networks, situating them within the broader methodological landscape that includes popular heuristic approaches like the D-statistic. We synthesize current research to compare these frameworks based on their underlying assumptions, computational requirements, statistical foundations, and biological interpretability, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Fundamental Definitions and Characteristics

Implicit Phylogenetic Networks

Implicit networks (also known as split networks or abstract networks) are primarily descriptive tools designed to visualize conflicting signals in phylogenetic data without attributing them to specific biological processes [1] [3]. They are typically unrooted graphs that summarize discordance based on genetic distances or conflicting tree topologies, regardless of the underlying biological cause [1].

Key Characteristics:

- Biological Interpretation: Internal nodes do not represent ancestral species or specific evolutionary events [3].

- Process Agnosticism: They visualize conflict but do not distinguish between different sources of discordance (e.g., ILS vs. hybridization) [1].

- Primary Use Case: Data exploration, visualization of conflicting signals, and analysis of datasets where the biological causes of discordance are unknown [1].

Explicit Phylogenetic Networks

In contrast, explicit networks are generative models of evolution that represent specific historical reticulate events [1] [3]. They are rooted, directed acyclic graphs whose internal nodes represent ancestral species, with reticulation nodes explicitly modeling events like hybridization or horizontal gene transfer [2] [1].

Key Characteristics:

- Biological Interpretation: Internal nodes represent explicit evolutionary events (speciation or reticulation) [3].

- Process Specificity: Reticulation vertices have two incoming edges, representing the fusion of genetic material from two ancestral populations [1].

- Model Parameters: Include inheritance probabilities (γ) that denote the proportion of genetic material contributed by each parent in a hybridization event [1] [3].

- Primary Use Case: Hypothesis testing about specific reticulate evolutionary histories [1].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Implicit and Explicit Networks

| Feature | Implicit Networks | Explicit Networks |

|---|---|---|

| Rooting | Unrooted | Rooted, directed |

| Internal Nodes | No biological meaning | Represent ancestral species |

| Reticulations | Summarize conflict | Represent specific historical events |

| Inheritance Probabilities | Not applicable | Estimated (γ parameters) |

| Evolutionary Model | None (phenetic) | Multispecies Network Coalescent (MNSC) |

| Primary Strength | Fast data exploration & visualization | Biologically intuitive hypothesis testing |

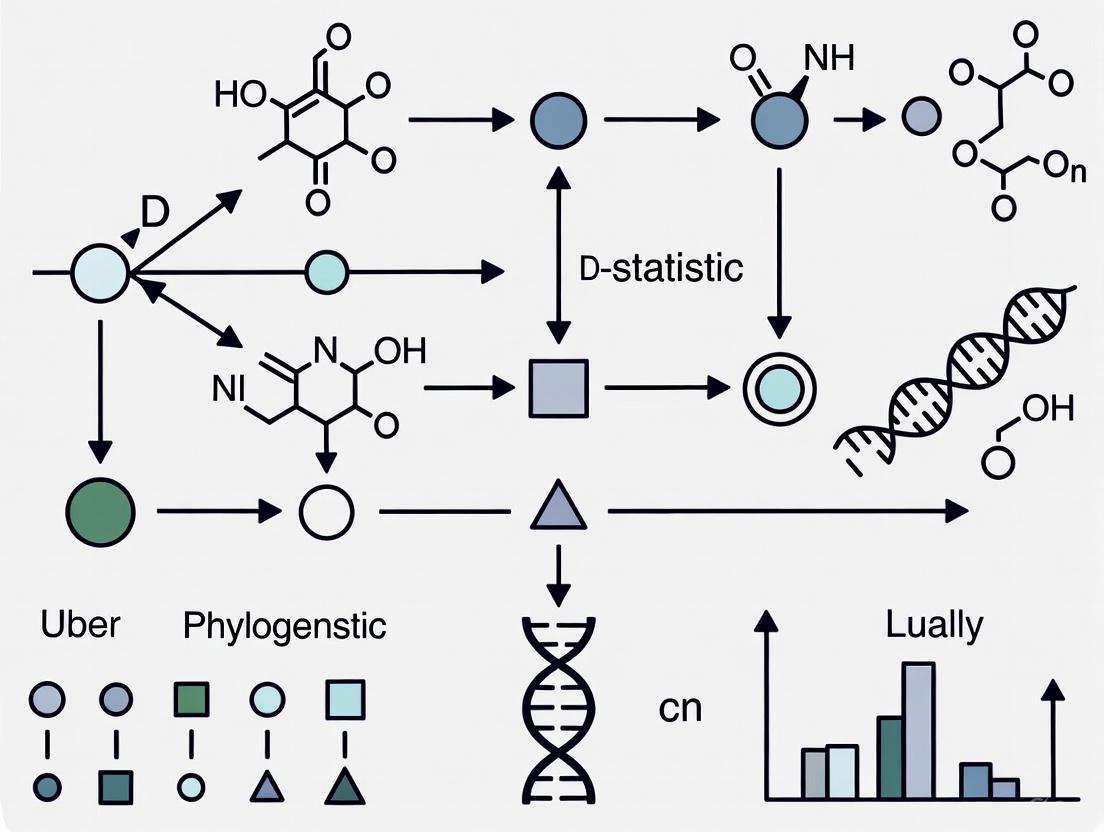

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural and conceptual differences between these network types:

Figure 1: Conceptual classification of phylogenetic networks, highlighting core differences between implicit and explicit paradigms.

Methodological Comparison and Experimental Data

Performance and Scalability

A critical consideration for researchers is the computational performance and scalability of different inference methods. Experimental studies have quantified these metrics across various approaches.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Phylogenetic Inference Methods

| Method (Category) | Representative Tools | Max Practical Taxa (Experimental) | Runtime for 25 Taxa | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Likelihood Explicit | PhyloNet [4] | < 10 taxa [5] | > Weeks (CPU) [4] | Intractable likelihood calculations [4] [5] |

| Pseudolikelihood Explicit | SNaQ [3], MPL [4] | ~25 taxa [4] | Prohibitive beyond ~25 taxa [4] | Heuristic search, pseudo-likelihood approximation [4] [3] |

| Divide-and-Conquer Explicit | PhyloNet [5] | Infeasible otherwise [5] | Significantly reduced [5] | Relies on accurate subset inference [5] |

| Implicit Networks | SplitsTree [4] [6], Neighbor-Net [4] | 100s of taxa [1] | Fast (minutes/hours) [4] | No explicit biological interpretation [1] [3] |

| Hybrid Detection (D-statistic) | Various [1] | Subsets of 4 taxa [1] | Very Fast | Sensitive to assumptions; poor with multiple reticulations [1] |

Biological Interpretation and Identifiability

The biological interpretability of results and the theoretical identifiability of parameters are fundamental distinctions.

Explicit Networks provide a direct link between the graphical model and evolutionary processes. Reticulation nodes model hybridization, with inheritance probabilities (γ) quantifying the genomic contribution from each parent [1] [3]. A value of γ ≈ 0.5 suggests symmetrical hybridization, as in a diploid F1 hybrid, while values skewed toward 0 or 1 indicate asymmetrical introgression [1]. However, distinguishing between hybrid speciation and repeated backcrossing based on γ alone remains challenging [1].

Implicit Networks, being process-agnostic, do not offer this level of biological specificity. They are useful for initial data exploration but cannot delineate the exact nature of reticulate events [1] [3].

Under the Multispecies Network Coalescent (MNSC) model, which accounts for both ILS and hybridization, explicit network parameters have been proven to be theoretically identifiable given sufficient data [1] [3]. This means that, in theory, the true network can be distinguished from other networks based on the gene tree distribution it generates. Implicit networks lack such a formal identifiability guarantee.

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

To ensure reproducible comparisons between methods, researchers must adhere to standardized experimental protocols. Below, we detail common workflows for evaluating phylogenetic network inference.

Protocol for Scalability Assessment

This protocol is derived from performance studies that quantify how methods handle increasing data size [4].

Dataset Simulation:

- Use a model phylogeny with a fixed number of reticulations (e.g., a single reticulation) to control for model complexity [4].

- Systematically vary the number of taxa (e.g., from 10 to 50) and the evolutionary divergence (sequence mutation rate) [4].

- Simulate multi-locus sequence alignments under the coalescent model with gene flow.

Method Execution:

Performance Metrics:

- Topological Accuracy: Compare the inferred network to the true simulated network using a distance metric (e.g., Robinson-Foulds distance for networks).

- Computational Requirements: Record CPU runtime and peak memory usage for each analysis.

- Success Rate: Note the proportion of analyses that complete within a reasonable time frame (e.g., 4 weeks).

The following diagram visualizes this experimental workflow:

Figure 2: Workflow for experimental assessment of phylogenetic network inference method scalability and performance.

Protocol for Inference from Multi-locus Data using SNaQ

SNaQ (Species Networks applying Quartets) is a representative pseudolikelihood method for explicit network inference. Its protocol highlights the steps common to many contemporary approaches [3].

Input Data Preparation:

- Obtain sequence alignments for multiple unlinked loci.

- For each locus, estimate a gene tree (topology and branch lengths). This step can be parallelized.

Summary of Gene Tree Discordance:

- For all possible combinations of four taxa (quartets), calculate the Concordance Factors (CFs). A CF is the proportion of genes whose true tree displays a specific quartet topology [3].

- The output is a set of observed CFs for the three possible quartets on every 4-taxon set.

Pseudolikelihood Optimization:

- The pseudolikelihood of a candidate network is computed based on the fit between its expected CFs (under the coalescent model with hybridization) and the observed CFs [3].

- A heuristic search is conducted over the space of phylogenetic networks (often level-1 networks) to find the topology, branch lengths (

t), and inheritance probabilities (γ) that maximize the pseudolikelihood.

This method bypasses the computationally intensive calculation of the full likelihood, enabling analysis of larger datasets than full-likelihood methods [3].

Selecting the appropriate software is essential for implementing the methodologies discussed. The table below catalogs major tools and their primary functions.

Table 3: Essential Software and Resources for Phylogenetic Network Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhyloNet [5] | Explicit Network | Maximum likelihood and parsimony inference from gene trees. | Infers explicit networks under the MNSC; includes full-likelihood and divide-and-conquer methods. |

| PhyloNetworks [3] | Explicit Network | Pseudolikelihood inference (SNaQ) from concordance factors or gene trees. | Infers explicit level-1 networks using a scalable quartet-based approach. |

| SplitsTree [4] [6] | Implicit Network | Computes split networks from distance matrices or tree collections. | Infers implicit networks for exploratory data analysis and conflict visualization. |

| D-statistic (ABBA-BABA) [1] | Hybrid Detection | Tests for gene flow among a set of four taxa. | A statistical test for introgression; does not infer a full network but can signal its necessity. |

| Sequence Aligner (e.g., MAFFT) | Data Preprocessing | Aligns raw nucleotide or amino acid sequences. | Creates the multiple sequence alignments used as input for gene tree estimation. |

| Gene Tree Estimator (e.g., RAxML) | Data Preprocessing | Estimates phylogenetic trees from sequence alignments. | Infers the gene trees that serve as input for many explicit network methods. |

Integrated Discussion: Placing D-Statistic and Network Methods in Context

The D-statistic and phylogenetic networks represent different points on a spectrum of methodological complexity and biological inference. The D-statistic is a targeted test for detecting gene flow between four taxa, serving as a useful and fast hypothesis-generation tool [1]. However, it operates on a limited taxonomic scale and can produce misleading results in the presence of multiple reticulations or ghost lineages [1].

Explicit phylogenetic networks represent a more comprehensive inference framework. They aim to reconstruct the complete evolutionary history of all sampled taxa, simultaneously accounting for ILS and multiple reticulation events [1] [3]. The trade-off for this completeness is significantly higher computational cost and more complex model selection [4] [5]. Implicit networks occupy a middle ground, providing a rapid overview of data conflict that can help decide whether to pursue more rigorous explicit modeling [1].

A critical finding from recent research is that these methods can yield contradictory results. For example, a study of Xiphophorus fishes found that an explicit network inferred via SNaQ detected fewer reticulation events than a tree with added gene flow events suggested by D-statistic analyses [1]. This underscores the importance of method choice and suggests that explicit networks might provide a more conservative and coherent picture of evolutionary history by integrating signals across the entire phylogeny.

Implicit and explicit phylogenetic networks are complementary tools with distinct strengths and applications. Implicit networks are superior for rapid data exploration and visualization of conflicting phylogenetic signals. In contrast, explicit networks are indispensable for formulating and testing specific biological hypotheses about reticulate evolution, as they provide a statistically rigorous, model-based framework for inference, albeit at a higher computational cost.

The D-statistic remains a valuable initial test for gene flow, but its limitations in complex scenarios necessitate the use of more robust network inference methods for whole-genome data. Current research is focused on improving the scalability and statistical power of explicit network methods through techniques like divide-and-conquer and pseudolikelihood approximations [5] [3]. As these methods continue to mature, they are poised to become the standard for reconstructing the richly interconnected Tree of Life.

The detection of gene flow is crucial for constructing accurate evolutionary histories across diverse fields, from evolutionary biology to drug development. The D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) is a widely used formal test for detecting gene flow, but it represents just one approach in a broader methodological landscape. This guide provides an objective comparison between the D-statistic and more complex phylogenetic network methods, evaluating their performance, scalability, and applicability based on current research. We summarize experimental data on computational demands, accuracy under simulation, and practical scope, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting appropriate methods based on their specific study systems and data constraints.

The evolutionary history of species and populations is often not a simple branching tree. Processes like gene flow (hybridization, introgression) and incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) create conflicting signals in genomic data, necessitating methods that can explicitly model these reticulate events. The D-statistic is a powerful, widely-used population genetic test designed to detect signals of gene flow between closely related species or populations by measuring allele frequency patterns against a null hypothesis of a strictly bifurcating tree [4]. Its simplicity and computational efficiency have made it a staple in evolutionary studies.

In contrast, phylogenetic network inference methods aim to reconstruct explicit evolutionary graphs that represent the full history of speciation and gene flow events. These methods model the interaction of multiple evolutionary processes, such as sequence mutation, gene flow, and ILS, to infer a more complete phylogenetic hypothesis [4]. The choice between using a simple test like the D-statistic or investing in a full network inference is a critical decision that balances statistical power, computational cost, and biological interpretability. This guide objectively compares these approaches using published experimental data and simulation studies to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Methodological Comparison: D-Statistic vs. Phylogenetic Networks

The D-statistic and phylogenetic network methods differ fundamentally in their goals, inputs, and underlying assumptions. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of the D-Statistic and Phylogenetic Network Methods

| Feature | D-Statistic | Phylogenetic Network Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | To test for the presence of a signal of gene flow. | To reconstruct an explicit evolutionary history that includes gene flow events. |

| Phylogenetic Scope | Typically operates on four taxa (a rooted triplet with an outgroup). | Can handle multiple taxa (dozens or more) to build a comprehensive network. |

| Output | A single statistic (D) and a p-value indicating deviation from a tree-like history. | A directed acyclic graph (network) showing species relationships and reticulations. |

| Key Assumption | Identifies gene flow that is inconsistent with a strictly bifurcating model; cannot easily distinguish gene flow from other processes like ancestral population structure. | Explicitly models gene flow and ILS; methods differ in their specific model assumptions (e.g., coalescent-based). |

| Data Input | Genome-wide counts of site patterns (ABBA, BABA). | Can use gene tree topologies, sequence alignments, or single-nucleotide polymorphisms. |

| Interpretation | Signal of gene flow between two specific lineages after their divergence from a third. | Visual representation of the evolutionary relationships, including the placement and number of hybridization events. |

Performance and Scalability: Experimental Data

The performance of these methods is critically evaluated based on their accuracy in recovering known evolutionary histories and their computational scalability. Simulation studies provide the primary evidence for these comparisons.

Accuracy and Computational Demand

A key scalability study tested state-of-the-art phylogenetic network methods on datasets of increasing size and complexity, including simulations with a single reticulation (gene flow event) [4]. The findings highlight a significant trade-off.

Table 2: Performance of Phylogenetic Network Methods on Empirical and Simulated Data [4]

| Method Type | Method Name (Example) | Accuracy (Topological) | Computational Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic (ML) | MLE, MLE-length | Most accurate | Prohibitive for >25 taxa (weeks of runtime, high memory) |

| Pseudo-Likelihood | MPL, SNaQ | High accuracy | More scalable than MLE, but still challenging for large datasets |

| Parsimony-Based | MP (Minimize Deep Coalescence) | Lower accuracy | More scalable than probabilistic methods |

| Distance-Based | Neighbor-Net, SplitsNet | Lower accuracy | Computationally fastest, produces a single network |

The study concluded that probabilistic methods, which maximize likelihood under coalescent-based models, are the most accurate [4]. However, this accuracy comes at a high computational cost. None of the probabilistic methods could complete analyses on datasets with 30 or more taxa within a practical timeframe, indicating that the field lags behind the needs of modern phylogenomic studies with dozens of genomes [4].

Impact of Data Scale on Performance

The same study found that the performance of all network inference methods is negatively impacted by two key dimensions of scale: the number of taxa and the evolutionary divergence (sequence mutation rate) [4]. As either factor increases, the topological accuracy of the inferred network degrades. This contrasts with the D-statistic, whose performance is less directly tied to the number of overall taxa but is constrained by its specific four-taxon requirement.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Understanding the typical workflows for these methods is essential for their application and for interpreting results from the literature.

Workflow for Phylogenetic Network Inference

The general process for inferring a phylogenetic network from molecular data involves multiple stages, from data collection to final tree evaluation [7].

A fundamental distinction in network inference lies in the choice of algorithm, which can be broadly categorized as either distance-based or character-based [7]. Character-based methods can be further divided into parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian approaches.

Table 3: Common Phylogenetic Tree/Network Construction Methods [7]

| Algorithm | Principle | Criteria for Final Tree | Scope of Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbor-Joining (NJ) | Minimal evolution; minimizes total branch length. | Produces a single tree. | Short sequences with small evolutionary distance. |

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) | Minimizes the number of evolutionary steps. | Tree with the smallest number of substitutions. | Sequences with high similarity. |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) | Finds the tree that makes the data most probable under a model. | Tree with the maximum likelihood value. | Distantly related sequences. |

| Bayesian Inference (BI) | Uses Bayes' theorem to compute the probability of a tree. | The most sampled tree in MCMC analysis. | A small number of sequences. |

Protocol for the D-Statistic

The D-statistic workflow is more focused, as its goal is hypothesis testing rather than full phylogeny reconstruction. It does not require the iterative search for an optimal graph topology.

The core of the D-statistic protocol involves counting specific site patterns across the genome. For a four-taxon test (((P1, P2), P3), Outgroup), an "ABBA" site is one where P1 and the Outgroup share the ancestral allele (A), while P2 and P3 share the derived allele (B). A "BABA" site is the converse. The D-statistic is calculated as:

D = (Sum(ABBA) - Sum(BABA)) / (Sum(ABBA) + Sum(BABA))

A significant deviation from zero (assessed via a block jackknife or other resampling method) indicates an imbalance of site patterns inconsistent with a simple bifurcating tree, which is interpreted as evidence of gene flow between P2 and P3 [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Success in phylogenetic inference and detecting gene flow relies on a suite of software tools and data resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Flow Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PhyloNet | Software package for inferring and analyzing phylogenetic networks. | Implements methods like MLE, MLE-length, and MP for multi-locus data [4]. |

| SNaQ | Software for inferring species networks from quartets under coalescent models. | A pseudo-likelihood method that offers a balance of accuracy and scalability [4]. |

| ADMIXTOOLS | A software package suite for population genetics. | Contains tools for calculating D-statistics and other formal tests for admixture [4]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Parallel computing environment. | Essential for running probabilistic network methods (ML, BI) on datasets of non-trivial size [4]. |

| Multi-Locus Sequence Data | Aligned DNA sequences from multiple independent loci. | The fundamental input for most phylogenetic network methods that account for ILS [7] [4]. |

| Reference Genomes | High-quality, assembled genomes. | Used as a baseline for mapping and calling variants for D-statistic analyses. |

The choice between the D-statistic and phylogenetic network methods is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is the right tool for the specific research question and data at hand.

Use the D-statistic when: Your goal is to test a specific hypothesis of gene flow between two lineages. It is ideal for initial screening, when working with very large genomic datasets (e.g., whole genomes), or when computational resources are limited. Its primary limitation is its inability to reconstruct the full network and its potential confusion of gene flow with other processes.

Use phylogenetic network methods when: Your goal is to reconstruct the complete evolutionary history of a group, including the number, placement, and direction of gene flow events. They are necessary when studying complex radiations with potential gene flow among multiple lineages. However, researchers must be aware of their severe computational constraints, which currently make them infeasible for large-scale phylogenomic studies with many taxa [4].

In conclusion, the D-statistic remains a powerful and efficient test for detecting gene flow, but it provides a limited, one-dimensional view. Phylogenetic network methods offer a powerful framework for reconstructing complex evolutionary histories but are currently constrained by scalability. The ongoing development of new algorithms, particularly those leveraging pseudo-likelihood and high-performance computing, is critical to bridging this methodological gap and fully realizing the potential of phylogenomic data.

Traditional phylogenetic analyses that assume strictly bifurcating trees often fail to capture the complexity of evolutionary histories involving processes such as hybridization, horizontal gene transfer, and introgression. In the presence of such gene flow, a phylogeny cannot be accurately described by a tree but instead requires the more general framework of a phylogenetic network—a directed acyclic graph that explicitly models reticulate evolutionary events [4] [8]. Phylogenetic networks are categorized as either explicit or implicit. Explicit networks directly represent specific evolutionary processes (e.g., gene flow through hybridization) at their reticulation nodes, whereas implicit networks merely summarize conflicting phylogenetic signals without specific biological interpretation [4]. This guide focuses on explicit phylogenetic networks, which provide a biologically meaningful framework for modeling reticulate history.

The advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies has produced phylogenomic datasets that increasingly reveal the prevalence of gene flow across diverse taxa, including humans, ancient hominins, mice, and butterflies [4]. These developments have created two primary scalability challenges for phylogenetic inference: the number of taxa in a study and the evolutionary divergence among them [4]. While the impact of these scaling dimensions on phylogenetic tree inference has been well characterized, the scalability limits of phylogenetic network inference methods remain poorly understood until recently [4]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of approaches for detecting and quantifying gene flow, focusing specifically on the performance characteristics of the parsimony-based D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) versus various phylogenetic network inference methods, with supporting experimental data from empirical studies.

Methodological Frameworks: D-Statistic vs. Phylogenetic Network Inference

The D-Statistic: A Parsimony-Based Test for Gene Flow

The D-statistic is a widely used parsimony-like method designed to detect gene flow between closely related species despite the presence of incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) [8]. This method operates on a four-taxon system (P1, P2, P3, O) with an established phylogeny of the form ((P1,P2),P3,O), where O is an outgroup. It compares the number of ABBA and BABA sites—parsimony-informative sites that support discordant phylogenies—to detect statistical evidence of gene flow [8].

- Mathematical Foundation: The D-statistic is calculated as D = (NABBA - NBABA) / (NABBA + NBABA), where NABBA and NBABA represent counts of these site patterns. Under pure ILS without gene flow, ABBA and BABA sites are equally likely, and D is expected to be zero. A significant deviation from zero indicates asymmetric gene flow, typically between P2 and P3 [8].

- Parameter Sensitivity: The effectiveness of the D-statistic is primarily determined by the relative population size (population size scaled by the number of generations since divergence). It is robust across a wide range of genetic distances but becomes less sensitive when population sizes are large relative to branch lengths in generations. The statistic is also affected by the direction, timing, and fraction of gene flow, as well as the number and size of loci analyzed [8].

- Associated f-statistics: To estimate the fraction of a genome affected by gene flow, several related statistics have been developed, including \( {\widehat{f}}G \), \( {\widehat{f}}{hom} \), and \( {\widehat{f}}_d \). However, these estimators often require precise knowledge of demographic parameters (divergence times, population sizes) and can exhibit high variance among loci, making them challenging to apply in practice without strong prior information [8].

Phylogenetic Network Inference: Modeling Reticulation Explicitly

Phylogenetic network methods aim to reconstruct explicit network structures that represent evolutionary histories involving reticulation. These methods can be broadly categorized into several classes based on their inference approach [4]:

- Concatenation Methods: Approaches such as Neighbor-Net and SplitsNet (SplitsTree) estimate a single phylogeny from combined sequence data across all loci. While computationally efficient, they typically account only for sequence mutation and may not adequately handle genealogical incongruence caused by ILS or gene flow [4] [9].

- Parsimony-based Methods: Methods like MP (Maximum Parsimony) utilize the minimize deep coalescence (MDC) criterion, seeking the species phylogeny that minimizes the number of deep coalescences needed to explain a given set of gene trees [4].

- Probabilistic Methods: These approaches perform inference under explicit evolutionary models that combine coalescent theory with biomolecular substitution models. They include:

- Full-Likelihood Methods: MLE and MLE-length (implemented in PhyloNet) calculate the full likelihood under the multispecies network coalescent (MSNC) model using gene tree topologies or topologies with branch lengths, respectively [4] [5].

- Pseudo-likelihood Methods: MPL and SNaQ (Species Networks applying Quartets) use approximations to the full model likelihood to improve computational efficiency while maintaining statistical consistency under appropriate conditions [4] [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Methodological Approaches to Detecting Gene Flow

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Theoretical Foundation | Data Input Requirements | Biological Processes Accounted For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Statistic | ABBA-BABA test [8] | Population genetics, parsimony | Genotype data for 4 taxa + outgroup | Gene flow, incomplete lineage sorting |

| Concatenation Networks | Neighbor-Net, SplitsNet [4] [9] | Distance-based, splits | Sequence alignments (concatenated) | Sequence mutation, some conflicting signal |

| Parsimony-based Networks | MP (Minimize Deep Coalescence) [4] | Parsimony, MDC criterion | Set of gene trees | Incomplete lineage sorting, gene flow |

| Probabilistic Networks | MLE, MLE-length (PhyloNet) [4] [5] | Coalescent theory, maximum likelihood | Gene trees or sequence alignments | ILS, gene flow, sequence mutation |

| Pseudo-likelihood Networks | SNaQ, MPL [4] [10] | Coalescent theory, quartets | Gene trees or concordance factors | ILS, gene flow |

Performance Comparison: Accuracy, Scalability, and Limitations

Detection Power and Accuracy

Empirical evaluations reveal significant differences in accuracy and detection power between methodological approaches:

D-Statistic Performance: The D-statistic effectively detects the presence of gene flow in a wide range of conditions, particularly for closely related species. However, its power is substantially diminished when population sizes are large relative to branch lengths in generations. The statistic serves primarily as a qualitative measure of gene flow, as estimating the actual fraction of introgressed genomic material (f) requires precise knowledge of divergence times and population sizes that is often unavailable in empirical studies [8].

Phylogenetic Network Accuracy: Probabilistic network inference methods generally demonstrate superior topological accuracy compared to parsimony-based or concatenation approaches. Methods maximizing likelihood under coalescent-based models or their pseudo-likelihood approximations consistently achieve the highest accuracy in recovering known phylogenetic networks in simulation studies [4]. The table below summarizes quantitative performance comparisons from empirical scalability studies.

Table 2: Performance and Scalability of Phylogenetic Network Methods on Large-Scale Datasets

| Method | Inference Type | Theoretical Guarantees | Maximum Practical Taxa | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Statistic | Gene flow detection | Statistical consistency under model assumptions [8] | Not applicable (fixed 4-taxon test) | Qualitative only; sensitive to population size; requires known species tree |

| Neighbor-Net | Concatenation network | None specifically for reticulation | Large datasets [9] | Does not explicitly model ILS or gene flow processes |

| MP (MDC) | Parsimony network | None known | >25 taxa [4] | Lower topological accuracy compared to probabilistic methods |

| MLE/MLE-length | Probabilistic network | Statistical consistency [5] | <25 taxa [4] | Prohibitive computational requirements beyond ~25 taxa |

| SNaQ/MPL | Pseudo-likelihood network | Statistical consistency for level-1 networks [10] | 30+ taxa with reduced accuracy [4] | Accuracy degrades with increasing taxa and mutation rate |

| ALTS | Tree-child network | Exact solution for displayed trees [11] | 50 taxa with 50 trees in ~15 minutes [11] | Limited to tree-child networks; performance depends on common clusters |

Scalability and Computational Requirements

Computational requirements represent a significant constraint for phylogenetic network inference, particularly for probabilistic approaches:

D-Statistic: Computationally efficient, allowing for genome-scale applications and bootstrap tests without significant computational burden [8].

Phylogenetic Network Methods: Scalability varies dramatically by approach. Concatenation methods like Neighbor-Net can handle large numbers of taxa but with biological interpretability limitations. Probabilistic methods face severe computational constraints, with full-likelihood methods often becoming prohibitive beyond 25 taxa. Even pseudo-likelihood methods show degraded accuracy with increasing taxon numbers and sequence mutation rates [4].

Innovative Scalable Approaches: Recent algorithmic developments aim to address these limitations:

- Divide-and-Conquer Inference: This approach infers networks on small, overlapping subsets of taxa (e.g., triplets) and merges them into a full network, enabling inference at scales previously infeasible for statistical methods [5].

- ALTS Algorithm: This method infers minimum tree-child networks by aligning lineage taxon strings from input trees, efficiently handling datasets with up to 50 taxa and 50 trees in approximately 15 minutes [11].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Experimental Workflow for Phylogenetic Network Inference

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for inferring phylogenetic networks from genomic data, integrating both traditional and novel scalable approaches:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Phylogenetic Network Inference from Genomic Data. This workflow shows two pathways: traditional network inference methods and scalable approaches necessary for larger datasets. The process begins with multi-locus sequence data, proceeds through gene tree estimation, and culminates in biological interpretation of the inferred network. (Short Title: Phylogenetic Network Inference Workflow)

D-Statistic Analysis Protocol

The experimental protocol for implementing the D-statistic involves:

- Taxon Selection: Identify four taxa with a well-established species tree topology: ((P1, P2), P3, Outgroup).

- Data Preparation: Obtain genome-wide SNP data or sequence alignments for the selected taxa.

- Site Pattern Counting: Scan the genome to count ABBA sites (where P1 and Outgroup share the ancestral allele, while P2 and P3 share the derived allele) and BABA sites (where P1 and P3 share the derived allele, while P2 and Outgroup share the ancestral allele).

- Statistical Testing: Calculate the D-value and perform a statistical test (e.g., jackknife or block bootstrap) to assess significance. A significant deviation from zero indicates gene flow between P2 and P3.

Protocol for Scalable Network Inference via Divide-and-Conquer

For large datasets where standard network inference fails, the divide-and-conquer protocol enables scalable analysis [5]:

- Subset Selection: Determine a collection of overlapping subsets of taxa (X₁, X₂, ..., Xₖ). When using three-taxon subsets (trinets), a hitting set algorithm can significantly reduce the number of subsets required without substantial accuracy loss.

- Subnetwork Inference: For each taxon subset, infer an accurate phylogenetic network (topology, divergence times, inheritance probabilities) using appropriate methods. With small subsets, even computationally intensive likelihood methods become feasible.

- Network Agglomeration: Combine the k subnetworks into a comprehensive phylogenetic network on the complete taxon set. This step involves reconciling topological features and parameters across overlapping subsets.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Phylogenetic Network Analysis

| Tool Name | Methodology | Primary Function | Data Input | Applicable Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhyloNet [5] | Probabilistic, Pseudo-likelihood | Network inference under MSNC | Gene trees, sequence alignments | Small to medium (up to ~30 taxa) |

| SNaQ [4] [10] | Pseudo-likelihood (quartets) | Network inference from quartets | Gene trees, concordance factors | Medium (dozens of taxa) |

| SplitsTree4 [9] | Splits, Neighbor-Net, Median-Joining | Network visualization and inference | Sequence alignments, distances | Large datasets |

| ALTS [11] | Lineage Taxon String alignment | Tree-child network inference | Set of phylogenetic trees | ~50 taxa, ~50 trees |

| HYBROSCALE [11] | Agreement forests | Network inference from trees | Set of phylogenetic trees | Limited by common clusters |

The choice between the D-statistic and phylogenetic network methods depends fundamentally on the biological question, dataset characteristics, and computational resources. The D-statistic provides a computationally efficient, robust method for detecting the presence of gene flow between specific taxon pairs in a four-taxon context, making it ideal for initial screening or focused hypothesis testing. However, it provides only qualitative evidence and requires a known species tree topology [8].

Phylogenetic network methods offer a more comprehensive approach for reconstructing explicit reticulate histories across multiple taxa. Probabilistic methods provide the highest accuracy but face severe computational constraints, while concatenation approaches sacrifice biological interpretability for scalability. Recent innovations in divide-and-conquer strategies [5] and novel algorithms like ALTS [11] are significantly expanding the feasible scale of network inference, enabling analyses previously limited to tree-based methods.

For researchers investigating gene flow, a strategic approach might combine both methodologies: using the D-statistic for initial detection and validation of gene flow, followed by phylogenetic network inference to reconstruct complete reticulate histories when applicable. As theoretical developments continue to expand the identifiability of more complex network structures [10] and computational methods overcome current scalability limitations, explicit phylogenetic networks are poised to become the standard framework for modeling reticulate evolution across the tree of life.

A fundamental challenge in modern evolutionary biology is deciphering the true history of species from genomic data. When gene trees constructed from different DNA sequences conflict with each other or with the hypothesized species tree, this phylogenetic incongruence signals complex evolutionary histories. The two primary processes responsible for such patterns are incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) and introgression/hybridization (IH) [12]. Both processes can produce remarkably similar patterns of gene tree discordance, making them difficult to distinguish without sophisticated analytical approaches [13]. Understanding which process explains observed genetic patterns is crucial for reconstructing accurate evolutionary histories and has implications for species delimitation, conservation biology, and understanding adaptive evolution.

ILS occurs when ancestral genetic polymorphisms persist through multiple speciation events and are randomly sorted into descendant lineages [12]. In contrast, introgression involves the transfer of genetic material from one species to another through hybridization and backcrossing [14]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the leading methods used to distinguish between these processes, focusing on their theoretical foundations, application protocols, and performance characteristics.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Principles

The D-Statistic (ABBA-BABA Test)

The D-statistic is a parsimony-based method that detects gene flow by comparing frequencies of discordant site patterns in a four-taxon system [8]. The method operates on a rooted quartet ((P1, P2), P3, O), where P1 and P2 are sister species, P3 is a more distantly related ingroup, and O is an outgroup. The core principle involves counting sites with specific patterns:

- ABBA sites: Sites where P1 and O share the ancestral allele, while P2 and P3 share the derived allele.

- BABA sites: Sites where P1 and O share the derived allele, while P2 and P3 share the ancestral allele [8].

Under pure ILS without gene flow, ABBA and BABA sites are equally likely, resulting in a D-statistic value not significantly different from zero. A significant excess of either pattern indicates introgression [8]. The D-statistic is calculated as: D = (NABBA - NBABA) / (NABBA + NBABA)

where NABBA and NBABA represent the counts of ABBA and BABA sites, respectively.

Phylogenetic Network Methods

Phylogenetic network methods provide a framework for representing evolutionary histories that include reticulate events such as hybridization. Unlike traditional phylogenetic trees, networks can incorporate nodes with multiple ancestors, explicitly modeling gene flow [4]. These methods can be broadly categorized into:

- Distance-based methods: Such as Neighbor-Net, which construct split networks summarizing conflicting signals [4].

- Parsimony-based methods: Like the MP method implemented in PhyloNet, which minimizes deep coalescences [4].

- Probabilistic methods: Including MLE, MLE-length, MPL, and SNaQ, which operate under coalescent models with explicit parameters for population sizes, divergence times, and gene flow [4].

Probabilistic methods fit the network to gene tree distributions or sequence data using maximum likelihood or Bayesian frameworks, providing statistical support for inferred reticulations [4].

Method Comparison and Performance Analysis

Table 1: Key Characteristics of D-Statistic and Phylogenetic Network Methods

| Feature | D-Statistic | Phylogenetic Network Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical basis | Parsimony-based site pattern counting | Coalescent-based model fitting |

| Data requirements | SNP data or sequence alignments; minimal sampling (single individual per species often sufficient) | Multi-locus sequence data or gene trees; better performance with multiple individuals |

| Computational requirements | Low; efficient even for genome-scale data | High; especially for probabilistic methods (MLE, MPL) which become prohibitive beyond 25-30 taxa [4] |

| Primary output | Test statistic (D) with significance assessment | Reticulate phylogeny with estimated hybridization events |

| Key assumptions | Correct rooting; no ancestral population structure; constant substitution rates | Correct gene tree estimation; neutral evolution; no recombination within loci |

| Detection power | High sensitivity to recent gene flow; powerful for testing specific hypotheses | Better for characterizing complex reticulation histories; infers direction and timing of gene flow |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Evolutionary Scenarios

| Scenario | D-Statistic Performance | Phylogenetic Network Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Recent divergence | High power if population sizes small relative to divergence time [8] | High accuracy, but computational constraints with many taxa [4] |

| Deep divergence | Robust across wide genetic distances, but sensitive to large population sizes [8] | Degrades with increased sequence divergence [4] |

| Recent gene flow | Excellent detection power [8] | Good detection and characterization ability |

| Ancient gene flow | Limited power for very ancient events | Can detect older hybridization events |

| Multiple reticulations | Limited to four-taxon tests; complex extensions needed for multiple events | Theoretically can handle multiple reticulations, but practice limited to few events [4] |

Sensitivity Analysis and Limitations

The D-statistic's effectiveness is primarily determined by the relative population size (population size scaled by generations since divergence) [8]. It performs best when population sizes are small relative to branch lengths in generations. The method is robust across a wide range of divergence times but becomes less reliable when population sizes are large [8].

Phylogenetic network methods face scalability challenges. Probabilistic methods like MLE and MPL are most accurate but become computationally prohibitive with more than 25 taxa, with runtimes extending to weeks for datasets with 30+ taxa [4]. Accuracy degrades with both increasing taxon numbers and higher sequence divergence [4].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing the D-Statistic

dot 4.1: D-Statistic Analysis Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Taxon selection: Identify four taxa with established phylogenetic relationships: two sister species (P1, P2), a closely related species (P3), and an outgroup (O).

- Data preparation: Obtain whole-genome sequences or SNP data. Align sequences using tools like MUSCLE or MAFFT.

- Variant calling: Identify homologous sites across all four taxa.

- Site pattern classification: For each informative site, determine whether it fits ABBA, BABA, or other patterns.

- D-statistic calculation: Compute D = (NABBA - NBABA) / (NABBA + NBABA).

- Significance testing: Assess statistical significance using block jackknife or bootstrap resampling to account for linked sites.

- Interpretation: A significantly positive D suggests gene flow between P3 and P2; negative D suggests gene flow between P3 and P1.

Phylogenetic Network Inference

dot 4.2: Phylogenetic Network Inference Pipeline

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Locus selection: Select dozens to hundreds of independent loci distributed across the genome.

- Gene tree estimation: Infer gene trees for each locus using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods.

- Network inference: Input gene trees into network inference software (e.g., PhyloNet for MLE/MPL, PhyloNetworks for SNaQ).

- Model selection: Compare networks with different numbers of reticulations using information criteria (AIC, BIC) or likelihood-ratio tests.

- Validation: Assess support using bootstrap resampling of loci or posterior probabilities.

- Interpretation: Identify hybridization events, direction of gene flow, and evolutionary relationships.

Case Studies in Empirical Research

Distinguishing ILS and Introgression in European Bison

The evolutionary history of the wisent (European bison) presents a classic case study. Mitochondrial DNA analysis placed wisent closer to cattle than to American bison, suggesting hybridization [15]. However, whole-genome analysis revealed that only a small portion (1.0-4.0%) of wisent nuclear genome showed cattle ancestry, with ABBA-BABA tests indicating recent rather than ancient introgression [15].

Nuclear gene trees displayed heterogeneous topologies, with the relative frequencies of different tree topologies consistent with expectations from ILS rather than widespread hybridization. Coalescent simulations confirmed that ILS alone could explain the anomalous mtDNA phylogeny as a rare event [15]. This case demonstrates the importance of genome-wide data and coalescent modeling for distinguishing these processes.

Complex Reticulation in Cobitis Fish Complex

The Cobitis fish complex exemplifies deep reticulate evolution. Phylogenomic analysis revealed mito-nuclear discordance, with C. tanaitica exhibiting mtDNA clustering with C. elongatoides but nuclear similarity to C. taenia [14]. Application of multiple methods (D-statistic, coalescent simulations, phylogenetic networks) indicated this pattern resulted from ancient hybridization and mitochondrial capture rather than ILS [14].

Interestingly, contemporary hybrids in this complex reproduce clonally (gynogenesis), preventing ongoing introgression. This suggests the detected hybridization events were ancient episodes mediated by previously existing hybrids with non-clonal inheritance [14]. This case highlights how method integration can unravel complex evolutionary histories.

Pine Species Divergence with Secondary Contact

Population genomic analysis of Pinus massoniana and P. hwangshanensis demonstrated the power of comparing allopatric versus parapatric populations. The finding of significantly more admixture in parapatric populations than allopatric ones provided evidence for secondary contact and introgression rather than ILS [13]. Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) modeling supported a scenario of long isolation followed by secondary contact during Pleistocene range expansions [13].

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-genome sequencing data | Provides comprehensive genomic coverage for site pattern analysis and gene tree estimation | Both D-statistic and network methods |

| Targeted sequence capture | Enriches specific loci across multiple individuals for multi-locus analyses | Phylogenetic network methods |

| BEAST/BEAST2 | Bayesian evolutionary analysis; divergence time estimation under coalescent models | Demographic inference for contextualizing ILS/IH |

| PhyloNet | Infers phylogenetic networks from gene trees under coalescent models | Network inference (MLE, MPL methods) |

| ADMIXTOOLS | Implements D-statistic and related f-statistics for detecting gene flow | D-statistic analysis |

| SplitsTree4 | Constructs phylogenetic networks from distance matrices | Distance-based network inference |

| SNaQ | Infers phylogenetic networks using quartet-based pseudo-likelihood | Network inference for larger datasets |

| HyDe | Detects hybridization using site pattern probabilities | Hybridization detection in multi-species systems |

Integrated Analysis Framework

dot 7.1: Decision Framework for Method Selection

For comprehensive analysis, researchers should consider an integrated approach:

- Initial screening: Use D-statistic to test for significant gene flow in specific taxon quartets.

- Detailed characterization: Apply phylogenetic network methods to infer detailed reticulate histories.

- Validation: Use coalescent simulations to assess whether inferred parameters could generate observed patterns through ILS alone.

- Contextualization: Incorporate demographic history (divergence times, population sizes) to interpret results biologically.

The most robust conclusions emerge from consistency across multiple methods and careful consideration of biological context, sampling design, and methodological assumptions.

The study of evolutionary history has been revolutionized by methods designed to detect past gene flow. Two prominent approaches have emerged: the D-statistic (ABBA-BABA test) and Phylogenetic Network inference methods. The D-statistic operates as a targeted hypothesis test for specific admixture events, providing a statistical signal of gene flow between four predefined populations or species [16]. In contrast, phylogenetic network methods aim to reconstruct comprehensive evolutionary histories that explicitly represent both divergence and hybridization events as reticulate networks [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, examining their performance, underlying assumptions, and suitability for different research scenarios in evolutionary biology and genomics.

Methodological Foundations and Comparison

Core Principles of Each Approach

The D-statistic Framework: The D-statistic tests the correctness of a hypothetical phylogenetic relationship between four populations (P1, P2, P3, and an outgroup P4) by evaluating specific allelic patterns [16]. It operates by comparing the frequencies of two discordant site patterns: "ABBA" sites, where P1 and P4 share allele A while P2 and P3 share allele B, and "BABA" sites, where P1 and P3 share allele A while P2 and P4 share allele B [16]. Under the null hypothesis of no gene flow, these patterns should occur with equal probability. Significant deviation from this expectation, measured by the D-statistic, provides evidence of gene flow, typically between P3 and P2 or P1 [16].

Phylogenetic Network Framework: Phylogenetic network methods represent evolutionary histories as directed acyclic graphs that can incorporate both vertical descent and horizontal gene flow through reticulation nodes [4]. Unlike the D-statistic which tests a specific hypothesis, network methods perform full inference by searching among all possible phylogenies defined on a set of taxa. Explicit networks attribute reticulations to specific evolutionary processes like gene flow, while implicit networks merely summarize conflicting phylogenetic signal without specific biological interpretation [4].

Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Scalability

Experimental comparisons on both simulated and empirical datasets reveal significant performance differences between these approaches and among specific implementation methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Phylogenetic Network Inference Methods [4]

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Topological Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Maximum Practical Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic (Full-likelihood) | MLE, MLE-length | Highest | Lowest (weeks for >25 taxa) | ~25 taxa |

| Probabilistic (Pseudo-likelihood) | MPL, SNaQ | High | Medium | Larger than full-likelihood |

| Parsimony-based | MP (Minimize Deep Coalescence) | Moderate | Medium | Larger than probabilistic |

| Concatenation | Neighbor-Net, SplitsNet | Lower | Highest | 50+ taxa |

Table 2: D-statistic Performance Characteristics [16]

| Performance Aspect | Traditional D-statistic | Improved D-statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Single read per population | All reads, multiple individuals |

| Sequencing Depth | Inefficient for 1-10x depth | Optimal power at 2x depth |

| Error Correction | Limited | Type-specific error correction |

| Distribution | Standard normal approximation | Standard normal approximation |

Key findings from empirical evaluations indicate that probabilistic phylogenetic network methods (MLE, MLE-length) achieve the highest accuracy but become computationally prohibitive beyond approximately 25 taxa, requiring weeks of runtime without completion [4]. The improved D-statistic significantly outperforms the traditional approach for low and medium sequencing depths (1-10×), with performance comparable to perfectly called genotypes at just 2× sequencing depth [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard D-Statistic Implementation Protocol

Workflow Overview:

- Population Selection: Identify four populations with a clear phylogenetic hypothesis to test, typically involving P1, P2, P3, and an outgroup P4 [16].

- Sequence Data Processing: Process high-throughput sequencing data, often requiring special handling for ancient DNA with deamination patterns [16].

- Site Pattern Counting: For each informative site, count ABBA and BABA patterns across all reads or a sampled base [16].

- Statistical Testing: Calculate the D-statistic as D = (ΣABBA - ΣBABA) / (ΣABBA + ΣBABA) and assess significance against a standard normal distribution [16].

Advanced Considerations: The improved D-statistic protocol incorporates multiple individuals per population without genotype calling, uses all available reads rather than sampling a single base, applies type-specific error correction for sequencing errors, and can correct for introgression from external populations not part of the supposed genetic relationship [16].

Phylogenetic Network Inference Protocol

Workflow Overview:

- Sequence Collection and Alignment: Collect homologous DNA sequences through experiments or public databases and perform multiple sequence alignment [7].

- Data Trimming: Precisely trim aligned sequences to remove unreliable regions while preserving genuine phylogenetic signals [7].

- Evolutionary Model Selection: Select appropriate substitution models (e.g., JC69, K80, TN93, HKY85) based on sequence characteristics [7].

- Network Inference: Apply specific network inference algorithms (e.g., MLE, MPL, SNaQ) to estimate phylogenetic networks [4].

- Topology Evaluation: Assess inferred networks through statistical support measures such as bootstrap values [17].

Method-Specific Variations:

- MLE Approach: Uses maximum likelihood estimation under coalescent-based models with branch length information [4].

- MPL Approach: Applies pseudo-likelihood approximations to full model likelihood calculations [4].

- SNaQ Approach: Combines pseudo-likelihoods under a coalescent model with quartet-based concordance analysis [4].

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of D-Statistic and Phylogenetic Network Methods

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| D-Statistic Implementation | ANGSD (doAbbababa2) [16], ADMIXTOOLS (qpDstat) [16] | Implements D-statistic on low-depth NGS data with error correction |

| Phylogenetic Network Software | PhyloNet [4], SNaQ [4] | Infers explicit phylogenetic networks under coalescent models |

| Sequence Alignment | MEGA10 [17], Bio Edit [17] | Multiple sequence alignment and editing |

| Tree/Network Visualization | MicrobeTrace [17] | Visualizes molecular transmission networks |

| Statistical Framework | R Language [7] | Provides statistical analysis and custom algorithm implementation |

Discussion: Strategic Selection for Evolutionary Analysis

The choice between D-statistic and phylogenetic network methods depends critically on research goals, dataset characteristics, and computational resources.

D-statistic is optimal when:

- Testing specific gene flow hypotheses between defined populations

- Working with low-coverage sequencing data (1-10×)

- Analyzing datasets with more than 30 taxa where network methods become computationally prohibitive [16] [4]

- Requiring rapid assessment of admixture signals

Phylogenetic network methods are preferable when:

- Reconstructing comprehensive evolutionary histories without predefined hypotheses

- Analyzing smaller datasets (≤25 taxa) where probabilistic methods remain feasible [4]

- Working with closely related species where incomplete lineage sorting is prevalent

- Visualizing complex evolutionary relationships with multiple reticulations

Emerging trends point toward normal networks as a promising class that balances biological relevance with mathematical tractability [18]. Furthermore, methodological improvements continue to enhance both approaches, such as the development of D-statistic implementations that utilize all available reads rather than sampling single bases [16].

For researchers in drug development and infectious disease studies, phylogenetic networks have proven particularly valuable for tracing transmission dynamics of pathogens like HIV and understanding the spread of drug resistance mutations [17]. The D-statistic remains widely applied in evolutionary studies of ancient DNA and population genomics where specific admixture hypotheses need testing [16].

Both D-statistic and phylogenetic network methods provide powerful approaches for detecting gene flow, yet they occupy distinct niches in evolutionary biology research. The D-statistic offers a targeted, statistically robust framework for testing specific admixture hypotheses, with particular strengths for low-coverage sequencing data. Phylogenetic network methods provide comprehensive evolutionary reconstruction but face computational constraints that limit their application to smaller datasets. Researchers should select methods based on their specific experimental questions, dataset scale, and computational resources, with the understanding that ongoing methodological developments continue to enhance the biological interpretability of both approaches.

A Practical Guide to Implementation and Workflow Integration

The D-statistic, or ABBA-BABA test, provides a powerful parsimony-based approach for detecting deviations from strict bifurcating evolutionary histories, most commonly used to identify gene flow between closely related species or populations. This methodology compares the frequencies of two discordant allele patterns ("ABBA" and "BABA") across genomes to test for significant deviations from the null expectation of equal frequencies, which would indicate introgression. This guide details the experimental workflow for implementing D-statistic analyses, provides a direct comparison with phylogenetic network methods, and presents empirical data evaluating their relative performance across different biological scenarios. The comparative analysis reveals that while D-statistic offers computational efficiency and simplicity for specific introgression tests, phylogenetic network methods provide more comprehensive evolutionary models at the cost of significantly greater computational resources.

In the era of genomics, detecting gene flow between species—introgression—has become fundamental to understanding evolutionary processes. The D-statistic and phylogenetic network methods represent two complementary approaches for identifying these complex evolutionary signals. The D-statistic operates as a targeted test for a specific four-taxon introgression scenario, quantifying deviations in allele pattern frequencies that suggest gene flow between non-sister taxa [19]. In contrast, phylogenetic network methods aim to reconstruct complete evolutionary histories that may include multiple reticulation events, explicitly modeling processes like hybridization and horizontal gene transfer that violate tree-like ancestry [4].

These methodologies differ fundamentally in their scope and underlying assumptions. The D-statistic tests a specific hypothesis about relationships between four predefined populations, requiring researchers to specify the exact phylogenetic context upfront [20] [19]. Phylogenetic network methods attempt to infer the overall phylogenetic structure from sequence data, potentially identifying unexpected relationships without requiring pre-specified hypotheses about which taxa might be involved in gene flow events [4]. This distinction makes D-statistic ideal for focused hypothesis testing, while network methods serve better for exploratory analysis of complex evolutionary scenarios.

The D-Statistic Workflow: From Sequences to Interpretation

Conceptual Foundation of the ABBA-BABA Test

The D-statistic operates on a simple but powerful principle: under a strictly bifurcating evolutionary tree with no gene flow, two specific discordant allele patterns should occur at approximately equal frequencies. The test requires four taxa with established phylogenetic relationships: (((P1, P2), P3), Outgroup) [20] [19]. The outgroup provides the ancestral state reference.

- ABBA sites: Sites where P2 and P3 share a derived allele ("B") while P1 retains the ancestral state ("A")

- BABA sites: Sites where P1 and P3 share a derived allele ("B") while P2 retains the ancestral state ("A")

Under the null hypothesis of no introgression, both patterns arise equally through incomplete lineage sorting (ILS). A significant excess of either pattern indicates gene flow, specifically between the taxa sharing derived alleles in the overrepresented pattern [19]. The D-statistic quantifies this deviation:

D = (ΣABBA - ΣBABA) / (ΣABBA + ΣBABA) [20]

A significant positive D value suggests gene flow between P2 and P3, while a significant negative value suggests gene flow between P1 and P3 [19].

Experimental Protocol and Computational Implementation

Data Preparation and Allele Frequency Estimation

The initial phase involves processing raw sequence data into analyzable allele frequencies:

Input Data: The workflow begins with genotype data from multiple individuals across populations, typically in variant call format (VCF) or similar. The data should be filtered for bi-allelic sites with sufficient quality [20].

Population Definition: Individuals are grouped into populations based on the biological hypothesis. For example, in a study of Heliconius butterflies, populations might represent different geographical races or species [20].

Derived Allele Frequency Calculation: Using the outgroup to determine ancestral states, compute the frequency of derived alleles in each population at each site. This can be accomplished using tools like the

freq.pyscript from the genomics_general package [20]:

This process generates a table of derived allele frequencies across all polymorphic sites for downstream analysis.

ABBA-BABA Calculation and Statistical Testing

With allele frequencies prepared, the analysis proceeds to pattern counting and significance testing:

ABBA/BABA Proportion Calculation: For each SNP site, compute the proportion that follows ABBA and BABA patterns using population allele frequencies rather than individual genotypes [20]:

ABBA = (1 - p1) * p2 * p3BABA = p1 * (1 - p2) * p3where p1, p2, p3 represent derived allele frequencies in populations P1, P2, and P3, respectively.

D-Statistic Computation: Sum ABBA and BABA proportions across all sites and calculate the D-statistic using the formula above [20].

Block Jackknife Significance Testing: To account for linkage disequilibrium and non-independence among sites, perform a block jackknife procedure with typically 1 Mb blocks [20]:

- Calculate pseudovalues of D by successively excluding each block

- Compute standard error from the pseudovalue variance

- Derive a Z-score to assess significance (|Z| > 3 generally considered significant) [21]

This workflow can be implemented in R or using specialized tools like the ipyrad-analysis toolkit [21].

Visualization of the D-Statistic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete analytical pipeline from raw data to interpretation:

Figure 1: Complete D-statistic workflow from raw data processing through statistical testing and biological interpretation.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Methodological Comparison Framework

To objectively evaluate the performance characteristics of D-statistic versus phylogenetic network methods, we analyzed their behavior across multiple dimensions including computational efficiency, detection power, scalability, and implementation requirements. The comparison draws from both empirical studies and theoretical considerations.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison Between D-Statistic and Phylogenetic Network Approaches

| Characteristic | D-Statistic | Phylogenetic Network Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Demand | Low to moderate; suitable for genome-scale data [8] | High; often prohibitive beyond 25-30 taxa [4] |

| Primary Function | Hypothesis testing for specific introgression scenarios [19] | Full phylogenetic inference including reticulations [4] |

| Data Requirements | Four predefined populations with known relationships [20] | Multiple loci across any number of taxa [4] |

| Detection Power | Robust for recent gene flow; sensitive to population size [8] | Varies by method; probabilistic approaches most accurate [4] |

| Key Limitations | Cannot distinguish ancestral structure from gene flow [22] | Computational limitations with increasing taxa [4] |

| Optimal Use Case | Testing specific gene flow hypotheses between known taxa | Inferring complex evolutionary histories with multiple reticulations |

| Implementation Tools | genomics_general, ipyrad-analysis [20] [21] | PhyloNet, SNaQ, Neighbor-Net [4] |

Empirical Performance Data

Several studies have quantitatively evaluated the performance of these methods under controlled conditions. The D-statistic demonstrates particular robustness to certain parameters while showing sensitivity to others:

Table 2: Empirical Performance Characteristics of D-Statistic Based on Simulation Studies

| Parameter | Effect on D-Statistic | Performance Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Population Size | Primary determinant of sensitivity; large populations reduce power [8] | Most effective when population sizes are small relative to branch lengths [8] |

| Genetic Distance | Robust across wide range of divergence times (0.3%-5% sequence divergence) [8] | Applicable to both recently diverged and moderately distant taxa |

| Gene Flow Direction | Asymmetric detection power; more powerful for certain directions [8] | Important to test multiple taxon arrangements |

| Locus Count | Power increases with more loci; minimal window size requirements [22] | Requires substantial genomic data for reliable inference |

| Outgroup Distance | Moderate effect; very distant outgroups can reduce power [8] | Optimal with appropriately chosen outgroup |

A critical finding from simulation studies is that the D-statistic is not an unbiased quantitative estimator of gene flow proportion. Its expected value increases non-linearly with the actual proportion of introgression (f) and is influenced by population size and divergence times [22]. This makes it most appropriate for detecting the presence rather than quantity of gene flow.

For phylogenetic network methods, performance varies considerably by implementation. Probabilistic methods (MLE, MLE-length) generally provide the highest accuracy but become computationally prohibitive with more than 25 taxa, often failing to complete analyses with 30+ taxa even after weeks of computation [4]. Pseudo-likelihood approximations (MPL, SNaQ) offer better scalability with moderate accuracy trade-offs [4].

Advanced D-Statistic Derivatives and Extensions

To address limitations of the standard D-statistic, several modified statistics have been developed:

- fd statistic: Better identifies introgressed loci while avoiding biases that affect D in regions of reduced diversity [22]

- fG and fhom: Estimate the fraction of genome affected by gene flow, though with high variance across loci [8]

- D3 statistic: Three-sample test using genetic distances rather than outgroup, useful when no appropriate outgroup is available [19]

These derivatives maintain the computational efficiency of the original D-statistic while addressing specific limitations, though they may introduce new assumptions or requirements.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of introgression analyses requires both biological materials and computational resources. The following toolkit represents essential components for designing and executing these studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Introgression Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Population Genomic Data | Source of genetic variation for analysis | Multiple individuals per population recommended; whole-genome sequencing preferred |

| genomics_general Package | Python utilities for frequency calculation and D-statistic | Provides freq.py for allele frequency calculation [20] |

| ipyrad-analysis Toolkit | Implementation of ABBA-BABA tests with visualization | Supports automated test generation from tree topology [21] |

| R Statistical Environment | Data manipulation, visualization, and custom analysis | Essential for block jackknife implementation and result visualization [20] |

| PhyloNet Software | Phylogenetic network inference under coalescent model | Provides multiple inference algorithms including MLE and MP [4] |

| Outgroup Sequence | Polarizes alleles as ancestral or derived | Should be appropriately diverged; critical for accurate pattern identification [20] |

Integrated Analysis Strategy

For comprehensive introgression analysis, we recommend a hierarchical approach that leverages the complementary strengths of both methodologies:

- Initial Screening: Apply D-statistic tests to multiple taxon quartets to identify potential gene flow events

- Validation: Use fd statistics to confirm introgression in identified regions and avoid biases [22]

- Contextualization: Implement phylogenetic network methods on subsets of taxa with strong signals to model complex relationships

- Interpretation: Integrate results with additional evidence (e.g., dXY, linkage disequilibrium) to distinguish introgression from ancestral structure

This integrated strategy balances computational efficiency with comprehensive inference, leveraging the hypothesis-testing strength of D-statistic while contextualizing results within broader evolutionary patterns.

The D-statistic provides a computationally efficient, targeted approach for detecting specific introgression scenarios, with particular strength in analyzing genome-scale data across moderate evolutionary distances. Its implementation through a standardized workflow of allele frequency calculation, pattern counting, and block jackknife validation offers robust detection of gene flow signals. However, its limitations in distinguishing gene flow from ancestral structure and its sensitivity to population size parameters necessitate complementary approaches. Phylogenetic network methods offer more comprehensive evolutionary modeling but face severe computational constraints with increasing taxonomic sampling. The choice between these approaches should be guided by specific research questions, dataset characteristics, and computational resources, with integrated strategies often providing the most insightful resolution of complex evolutionary histories.

This guide provides an objective comparison between maximum pseudolikelihood (MPL) and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) for inferring complex networks in social, phylogenetic, and psychometric research. MLE is generally superior in statistical accuracy (lower bias, better coverage) for models with strong dependence structures but is often computationally intractable for large or complex problems [23] [24]. MPL offers a computationally efficient and viable approximation, enabling the analysis of large-scale datasets (e.g., many taxa or variables) that are prohibitive for full-likelihood methods, though it can exhibit higher bias and underestimate standard errors [25] [26] [27]. The choice between them involves a fundamental trade-off between statistical precision and computational feasibility, heavily influenced by the specific data structure and research goals.

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of MLE and MPL established across various fields.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of MLE and MPL Across Domains

| Domain | Criterion | Maximum Likelihood (MLE) | Maximum Pseudolikelihood (MPL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGMs) | Bias & Coverage | Lower bias, better coverage rates [23] [24] | Higher bias, especially with complex dependence [23] [24] |

| Standard Errors | Accurate estimation [23] | Tends to underestimate standard errors [23] | |

| Phylogenetic Network Inference | Topological Accuracy | High accuracy where computationally feasible [27] [4] | High accuracy, often comparable to MLE [25] [27] |

| Computational Scalability | Limited to small networks (e.g., ~10-25 taxa) [27] [4] | Scales to large networks (dozens of taxa) [25] [27] | |