Breaking Down Silos: Classroom Activities to Overcome Epistemological Obstacles in Scientific Research

This article provides a practical framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to identify and overcome epistemological obstacles—the deep-seated differences in how disciplines create knowledge—that hinder interdisciplinary collaboration.

Breaking Down Silos: Classroom Activities to Overcome Epistemological Obstacles in Scientific Research

Abstract

This article provides a practical framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to identify and overcome epistemological obstacles—the deep-seated differences in how disciplines create knowledge—that hinder interdisciplinary collaboration. Drawing on experiential learning theory and real-world case studies, we detail actionable classroom activities designed to foster epistemological awareness, translate methods across fields, troubleshoot common collaboration failures, and validate the success of integrated research teams in achieving transformative scientific outcomes.

Understanding the Invisible Walls: A Primer on Epistemological Obstacles in Science

An epistemological framework is a structured system or blueprint that guides how a discipline or community perceives, interprets, and validates information about the world [1]. Derived from epistemology—the philosophical theory of knowledge concerned with its nature, origins, and limits—these frameworks provide the foundational lens for making sense of complex challenges [2] [1]. In scientific and research contexts, they are not abstract philosophies but active, operational tools that shape organizational strategies, research methodologies, and policy development [1]. They determine what questions are worth asking, what methods are considered valid for answering them, and what criteria are used to judge the reliability of the answers [1]. Understanding these frameworks is therefore essential for comprehending how scientific knowledge, including that in drug development, is constructed and validated.

Core Elements of Epistemological Frameworks

Any robust epistemological framework is built upon several interconnected core elements. These components provide the necessary scaffolding for a coherent approach to knowledge creation and evaluation within a field [1].

Table 1: Core Elements of an Epistemological Framework

| Element | Description | Example in a Scientific Context |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Assumptions | Foundational beliefs about reality and the nature of knowledge itself (e.g., that an objective truth is attainable or that knowledge is socially constructed). | The assumption that biological phenomena follow predictable, causal laws that can be discovered through controlled experimentation. |

| Methodologies & Approaches | The specific, acceptable methods for acquiring and validating knowledge. | Techniques such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quantitative analysis, statistical modeling, and peer review. |

| Criteria for Validation | The standards used to assess the reliability and trustworthiness of knowledge claims. | Requirements for statistical significance (p-values), reproducibility of results, and methodological rigor. |

| Scope & Boundaries | The defined areas of inquiry the framework encompasses and the limits of its application. | A framework might be specialized for molecular pharmacology, clinical outcomes, or epidemiological studies. |

These elements work in concert to form a coherent system. For instance, a positivist framework, dominant in much of traditional drug development, assumes an objective reality, employs quantitative and experimental methodologies, and validates knowledge through empirical data and statistical analysis [1]. In contrast, a constructivist framework, often used in research on patient experiences or the sociology of science, might assume that knowledge is influenced by social contexts and perspectives, and would thus employ qualitative methods like interviews, validating findings through their coherence with lived experiences and expert deliberation [1].

Experimental Protocols for Epistemological Analysis

To move from theory to practice, researchers can employ the following structured protocols to analyze and identify the epistemological frameworks operating within a body of literature, a research team, or a set of classroom activities.

Protocol 1: Disciplinary Framework Deconstruction

Application: This methodology is designed for analyzing published research, grant proposals, or project documentation to expose its underlying epistemological stance.

Workflow:

- Sample Selection: Identify a representative corpus of texts (e.g., key journal articles, methodology sections, conference proceedings) from the discipline or research group under study.

- Data Extraction and Coding:

- Systematically code the texts for the elements listed in Table 1.

- Note the specific terminology used, the types of evidence privileged (e.g., numerical data vs. narrative accounts), and the structure of argumentation.

- Thematic Analysis:

- Group the coded data to identify patterns in assumptions, methods, and validation criteria.

- Compare and contrast these patterns with known epistemological frameworks (e.g., positivism, constructivism, critical realism) [1].

- Framework Identification and Documentation:

- Synthesize the analysis to define the dominant epistemological framework.

- Document findings in a report, using tables and direct quotes as evidence for the classification.

Protocol 2: Epistemological Reflection in Classroom Research Activities

Application: This protocol is designed for use in educational settings to help students and researchers uncover their own epistemological commitments during the research process, thereby identifying potential "epistemological obstacles."

Workflow:

- Pre-Activity Baseline Elicitation: Before a research task (e.g., designing an experiment), participants complete a short questionnaire asking them to define "good evidence" and justify their proposed methodology.

- Guided Research Execution: Participants engage in the research task (e.g., data collection and analysis).

- Structured Reflection and Comparison:

- Upon completion, participants are guided through a reflection on their process using a structured worksheet.

- The worksheet prompts them to compare their initial baseline answers with their actual actions and decisions during the task.

- Obstacle Identification and Discussion:

- Facilitators help participants identify discrepancies between their stated epistemology and their practiced epistemology as potential epistemological obstacles.

- A group discussion explores how different frameworks could lead to different approaches and conclusions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents for Epistemological Inquiry

The "experimental" study of epistemological frameworks requires specific conceptual tools rather than physical reagents. The following table details essential materials for designing and implementing the protocols described above.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epistemological Analysis

| Item | Function / Definition | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Textual Corpus | A curated collection of documents from the discipline or group under analysis (e.g., research papers, lab manuals, grant proposals). | Serves as the primary source of data. Must be representative of the field to ensure valid conclusions. |

| Coding Schema | A predefined set of categories and tags based on the core elements of epistemological frameworks (see Table 1). | Enables systematic and consistent data extraction from the textual corpus, transforming qualitative text into analyzable data. |

| Structured Reflection Worksheet | A guided questionnaire prompting individuals to articulate their assumptions, methodological choices, and criteria for evidence. | Facilitates metacognition and makes implicit epistemological beliefs explicit, which is crucial for identifying obstacles. |

| Framework Lexicon | A reference document defining key epistemological terms (e.g., positivism, constructivism, objectivity, situated knowledge). | Provides a common language for researchers and students to discuss and classify different epistemological stances accurately [2] [1]. |

Data Presentation: Framework Comparison and Outcomes

The results of epistemological analyses can be synthesized into comparative tables to clarify distinctions and inform research design. Furthermore, implementing classroom reflection protocols can yield specific, observable outcomes.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Epistemological Frameworks in Science

| Framework | Underlying Assumption | Preferred Methodology | Validation Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positivism | Objective reality exists and can be known through observation and measurement. | Quantitative experiments, controlled trials, statistical modeling. | Empirical verification, reproducibility, statistical significance. |

| Constructivism | Knowledge is context-dependent and co-constructed through social and cultural practices. | Qualitative interviews, ethnographic studies, discourse analysis. | Credibility, transferability, confirmability, coherence with participant perspectives. |

| Pragmatism | The value of knowledge is determined by its practical consequences and utility in problem-solving. | Mixed-methods, design-based research, action research. | Whether knowledge successfully guides action towards a desired outcome, solves a problem. |

Table 4: Expected Outcomes from Classroom Epistemological Reflection

| Outcome Category | Specific Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Increased Metacognition | Students can articulate why they chose a particular method over another. Students demonstrate awareness of the limits of their chosen approach. |

| Identification of Obstacles | Recognition of a default preference for quantitative data over qualitative insights, or vice versa. Identification of the "one right answer" mindset as a barrier to exploring multiple interpretations. |

| Enhanced Critical Thinking | Improved ability to deconstruct and evaluate the strength of arguments in scientific literature. More nuanced design of research questions that account for methodological limitations. |

Application Note: Systematic Categorization of Classroom Conflict

Conceptual Framework for Conflict Typology

Classroom conflicts present significant epistemological obstacles that can hinder the acquisition of scientific reasoning skills essential for drug development professionals. We propose a systematic framework for categorizing conflict sources to facilitate their integration into structured learning activities. This classification enables researchers to design targeted interventions that address specific cognitive barriers in experimental design and data interpretation [3].

The typology identifies four primary conflict dimensions relevant to scientific training: interpersonal dynamics arising from collaborative work, intrapersonal conflicts in hypothesis formulation, institutional constraints on research methodologies, and cultural differences in scientific communication styles. Each dimension presents unique challenges for establishing evidentiary standards and causal inference in pharmaceutical research contexts [3].

Quantitative Conflict Metrics and Measurement

Systematic observation and quantification of classroom conflicts provide valuable proxies for understanding epistemological obstacles in research environments. The following table summarizes key metrics adapted from educational research to scientific training contexts:

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Classroom Conflict Analysis

| Metric Category | Specific Measures | Research Application | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Indicators | Conflicts per session; Duration in minutes | Patterns in collaborative breakdown | Direct observation; Session recording |

| Impact Measures | Disengagement index; Learning disruption time | Assessment of team productivity loss | Behavioral coding; Time-sampling |

| Resolution Metrics | Teacher intervention frequency; Student-led resolution rate | Evaluation of research team self-correction | Intervention logs; Conflict diaries |

| Relational Dimensions | Network analysis of alliances; Communication pattern mapping | Scientific collaboration dynamics | Sociograms; Communication transcripts |

These metrics enable the translation of qualitative conflict observations into analyzable quantitative data, facilitating the identification of patterns and testing intervention effectiveness [4] [5].

Experimental Protocols for Conflict Analysis

Protocol: Restorative Circle Implementation for Research Teams

Background and Principles

Restorative practices (RP) offer structured approaches for addressing conflicts that arise during collaborative research activities. Originally developed for educational settings, these techniques show significant promise for managing epistemological tensions in drug development teams where divergent interpretations of experimental data commonly occur [6].

The protocol emphasizes repairing harm and rebuilding working relationships rather than assigning blame, creating an environment where scientific disagreements can be explored productively. This approach aligns with the iterative nature of hypothesis testing and model refinement in pharmaceutical research.

Materials and Equipment

- Facilitator Guide: Structured questioning framework for conflict mediation

- Participant Pre-Assessment: Validated instrument measuring conflict attitudes

- Recording System: Audio/video equipment for session documentation and analysis

- Environmental Setup: Circular seating arrangement to promote equitable participation

- Post-Session Evaluation Forms: Quantitative and qualitative assessment tools

Step-by-Step Procedure

Pre-Circle Assessment (15 minutes)

- Administer pre-assessment instruments to all participants

- Establish baseline measures of team cohesion and conflict perception

- Review confidentiality agreements and ethical guidelines

Circle Initiation (10 minutes)

- Arrange participants in circular formation without hierarchical positioning

- Facilitator states the purpose: "To understand different perspectives on our experimental design disagreement"

- Establish shared guidelines for respectful dialogue and active listening

Sequential Narrative Sharing (20-30 minutes)

- Implement round-robin format ensuring each participant speaks without interruption

- Use restorative questions: "What did you think when the methodology conflict emerged?" "How has this affected your ability to contribute to the project?"

- Document key themes and emotional responses

Collective Problem-Solving (20 minutes)

- Facilitate identification of shared goals and divergent interpretations

- Guide participants toward mutually acceptable solutions for moving forward

- Establish specific action items for implementing revised experimental approaches

Closure and Evaluation (10 minutes)

- Administer post-session assessments measuring perceived resolution effectiveness

- Schedule follow-up assessment points at 1-week and 1-month intervals

- Document agreements for future reference

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative data from pre/post assessments should be analyzed using paired t-tests to measure significant changes in conflict perception. Qualitative data from session transcripts should undergo thematic analysis using established coding frameworks. Integration of mixed methods provides comprehensive understanding of intervention effectiveness [4].

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of Conflict Patterns in Research Training

Experimental Design

This protocol employs systematic observation and statistical analysis to identify conflict patterns in laboratory training environments. The approach adapts established quantitative methods from educational research to scientific training contexts [4] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Conflict Pattern Analysis

| Item | Specifications | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Coding Software | Noldus Observer XT or equivalent | Systematic recording and categorization of conflict behaviors |

| Statistical Analysis Package | SPSS, R, or Python with Pandas/NumPy | Quantitative analysis of conflict frequency and correlates |

| Survey Platform | Qualtrics, REDCap, or equivalent | Administration of validated conflict assessment instruments |

| Video Recording System | Multi-angle cameras with audio capture | Comprehensive documentation of interactions for later analysis |

| Data Management System | Secure database with structured fields | Organization and retrieval of conflict incident records |

Procedure

Instrument Validation

- Establish inter-rater reliability for behavioral coding schemes (target κ > 0.8)

- Pilot-test survey instruments with representative sample

- Refine measurement tools based on pilot feedback

Data Collection Phase

- Record approximately 50 hours of research team interactions

- Code conflicts using established typology with time-stamping

- Administer conflict style assessments to all participants

- Collect demographic and professional background variables

Statistical Analysis

- Employ descriptive statistics to characterize conflict patterns

- Conduct correlation analysis to identify relationship between variables

- Use inferential statistics (ANOVA, regression) to test specific hypotheses

- Perform cross-tabulation to examine categorical relationships [5]

Data Visualization and Workflow Integration

Conflict Analysis Pathway

Diagram 1: Conflict Analysis Workflow

Quantitative Data Analysis Framework

Diagram 2: Quantitative Analysis Methods

Data Synthesis and Interpretation Framework

Integrated Conflict Assessment Matrix

The systematic approach to conflict analysis generates multiple data streams requiring integrated interpretation. The following table provides a structured approach to data synthesis:

Table 3: Multi-Method Conflict Assessment Matrix

| Data Type | Collection Method | Analysis Approach | Interpretation Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Observations | Systematic coding of recorded interactions | Frequency analysis; Sequential pattern identification | Link specific behaviors to project milestones and outcomes |

| Self-Report Measures | Validated surveys; Post-session assessments | Descriptive statistics; Factor analysis; Correlation | Compare perceived vs. observed conflict dynamics |

| Performance Metrics | Project completion rates; Protocol deviations | Regression analysis; Comparative statistics | Assess impact of conflict management on research quality |

| Relational Data | Social network analysis; Communication mapping | Network centrality measures; Density calculations | Identify structural contributors to conflict emergence |

This integrated framework enables researchers to move beyond superficial conflict descriptions toward evidence-based understanding of underlying mechanisms [7] [3] [4].

Implementation Guidelines for Research Settings

Adaptation for Drug Development Contexts

The protocols and assessment strategies outlined require specific adaptations for pharmaceutical research environments. Key considerations include:

- Regulatory Compliance: Ensure all data collection meets ethical and regulatory standards for research settings

- Intellectual Property Protection: Implement safeguards for proprietary information during conflict resolution sessions

- Cross-Functional Dynamics: Address unique challenges arising from interdisciplinary team compositions

- High-Stakes Environments: Modify approaches for conflicts involving significant financial or clinical implications

Evidence from educational implementations of restorative practices suggests potential reductions in team dissolution and protocol deviations, though rigorous studies in research settings remain limited [6].

Quality Control and Validation

Establish quality control measures through regular calibration of observers, periodic reliability assessments, and continuous validation of instruments against project outcomes. Implementation fidelity should be monitored through systematic observation of protocol adherence and regular review of procedural documentation.

In the pursuit of solving complex scientific challenges, interdisciplinary collaboration has become increasingly essential, particularly in fields like pharmaceutical development and biomedical research. However, these collaborations face a significant yet often overlooked threat: disciplinary capture. This phenomenon occurs when the epistemological framework, methods, and decision-making processes of a single dominant discipline dictate the trajectory of an interdisciplinary project, effectively marginalizing the contributions of other disciplines [8]. The consequences include compromised research quality, stifled innovation, and ultimately, projects that fail to achieve their full interdisciplinary potential.

The concept of disciplinary capture explains why, despite involvement of experts from multiple fields, project outcomes may align solely with the standards, values, and objectives of one discipline [8]. This is not typically the result of malicious intent but rather an unintended consequence of structural and epistemological imbalances within collaborative projects. Common triggers include early methodological decisions that favor one discipline's approaches, funding structures that privilege certain forms of knowledge, or simply the dominant position of a particular field within an institutional hierarchy [8]. The result is that collaborators from other disciplines may feel their expertise is undervalued or improperly utilized, leaving crucial perspectives "on the table" [8].

Understanding and mitigating disciplinary capture is crucial for research integrity and innovation. When capture occurs, the very benefits that justify interdisciplinary work—diverse perspectives, innovative methodological combinations, and comprehensive problem-solving—are substantially diminished. This application note provides researchers with the analytical tools and practical protocols to identify, prevent, and address disciplinary capture in their interdisciplinary projects.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Epistemological Foundations of Disciplinary Capture

At its core, disciplinary capture stems from differences in epistemological frameworks across disciplines. An epistemological framework encompasses the fundamental beliefs about what constitutes valid knowledge within a discipline, including what phenomena are worth studying, which methods are considered rigorous, what counts as sufficient evidence, and how causal relationships are understood [8]. These frameworks are "tailor-made" to handle specific sets of problems within specific disciplines and are deeply ingrained through professional training and practice [8].

When collaborators from different fields convene, they bring these deeply embedded frameworks with them. A biologist might prioritize controlled experimental evidence, while a qualitative researcher might value rich contextual understanding from case studies. An engineer might seek mechanistic causal explanations, while a social scientist might incorporate human intentions and social structures as valid causes [8]. These differences can lead to fundamental disagreements that, if unaddressed, create conditions where one framework dominates by default rather than through deliberate integration.

Disciplinary Capture Versus Related Concepts

It is important to distinguish disciplinary capture from other collaboration challenges:

- Multidisciplinarity involves specialists from two or more disciplines working together on a specific objective while maintaining their disciplinary approaches [9]. This differs from interdisciplinarity, which aims to integrate disciplines to create new approaches, methods, or understandings [9].

- Disciplinary capture occurs specifically when the potential for integration is undermined by the dominance of one disciplinary framework, resulting in collaboration that appears interdisciplinary in membership but remains monodisciplinary in execution and outcome [8].

- Unlike general communication problems, disciplinary capture involves deeper epistemological disagreements about what counts as valid knowledge and rigorous methodology [8].

Quantitative Evidence: The Impact and Manifestations of Capture

Research across multiple domains has documented the challenges and barriers that facilitate disciplinary capture in collaborative science. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from studies on interdisciplinary collaboration:

Table 1: Documented Barriers to Interdisciplinary Collaboration

| Domain/Study | Key Findings on Collaboration Barriers | Prevalence/Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Collaboration (Pakistan) [10] | Role and leadership ambiguity | 68.6% of respondents identified as major barrier |

| Different goals among team members | 68.1% of respondents identified as major barrier | |

| Differences in authority, power, expertise, and income | 53.3% strongly agreed this was a barrier | |

| Primary Healthcare (Qatar) [11] | Hierarchical barriers among professionals | Frequently cited qualitative barrier |

| Lack of communication skills | Identified as key challenge across focus groups | |

| Insufficient professional competencies | Reported across multiple professional groups | |

| Scientific Research [12] | Pressures of scientific production | Major factor driving "normal misbehaviors" |

| Problems with data interpretation in "gray areas" | Common concern among researchers | |

| Difficulty balancing data "cleaning" versus "cooking" | Frequently reported ethical challenge |

These documented barriers create environments ripe for disciplinary capture. For instance, when role ambiguity combines with power differentials, researchers from disciplines with less institutional power may hesitate to advocate for their epistemological perspectives, allowing more established disciplines to dominate methodological decisions [10] [11].

Beyond these structural barriers, scientists report numerous "normal misbehaviors" in daily research practice that can exacerbate disciplinary capture [12]. These include problematic data handling practices, credit allocation issues, and ethical gray areas in research implementation—all of which may be interpreted differently through various disciplinary lenses [12].

Experimental Protocols for Identifying and Mitigating Disciplinary Capture

Protocol 1: Disciplinary Perspective Mapping

Purpose: To make explicit the implicit epistemological frameworks of each discipline represented in a collaboration before methodological decisions are finalized.

Materials: Digital whiteboard platform, disciplinary perspective worksheet, recording device for meetings, facilitator from outside the project team.

Procedure:

- Individual Preparation: Before the first project meeting, ask each team member to complete a disciplinary perspective worksheet containing the following questions [13]:

- What are the central research questions that drive your discipline?

- What methodological approaches are considered most rigorous in your field?

- What types of evidence are required to support claims in your discipline?

- How does your discipline conceptualize causal relationships?

- What values or goals ultimately guide research in your field?

- Structured Discussion: Dedicate the first project meeting to sharing these perspectives. The external facilitator should guide discussion using the following DOT visualization to ensure all dimensions are covered:

Diagram 1: Dimensions of Disciplinary Perspective

- Integration Document: Create a collaborative document summarizing points of alignment and potential conflict across disciplinary perspectives. This document should be revisited at key project decision points.

Expected Outcomes: Team members develop metacognitive awareness of their own disciplinary assumptions and better understanding of collaborators' perspectives, reducing the likelihood of unexamined disciplinary default.

Protocol 2: Epistemological Conflict Mediation

Purpose: To resolve fundamental disagreements about research design, methods, or standards of evidence that threaten to create disciplinary capture.

Materials: Case studies of successful integrations, facilitation guides, decision documentation templates.

Procedure:

- Early Identification: Establish regular checkpoints where team members can flag potential epistemological conflicts using indicators such as:

- Consistent undervaluing of certain data types

- Repeated challenges to methodological validity

- Disagreements about what constitutes sufficient evidence

Structured Mediation Session:

- Step 1: Each discipline explains their preferred approach using the framework from Protocol 1

- Step 2: Collaboratively identify the core epistemological disagreement

- Step 3: Brainstorm potential integrative approaches that honor multiple perspectives

- Step 4: Develop a pilot study to test integrative approaches

Implementation and Evaluation: Document the agreed approach and establish criteria for evaluating its effectiveness, with scheduled reassessment points.

Troubleshooting: When conflicts persist, consider involving an external expert with experience in interdisciplinary integration to facilitate resolution.

Visualization Tools for Project Navigation

Effective navigation of interdisciplinary projects requires visualizing both the process of collaboration and the points where disciplinary capture may occur. The following DOT diagram illustrates the collaborative workflow with critical intervention points:

Diagram 2: Collaboration Workflow with Capture Risk Points

Successful navigation of interdisciplinary collaboration requires specific conceptual tools and frameworks. The following table outlines key resources for identifying and preventing disciplinary capture:

Table 2: Essential Resources for Preventing Disciplinary Capture

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Disciplinary Perspective Framework [13] | Makes implicit epistemological assumptions explicit | Project initiation; conflict resolution |

| The "Gears" Model [11] | Analyzes barriers at macro, meso, micro, and individual levels | Organizational planning; barrier assessment |

| Epistemological Conflict Mediation | Provides structured approach to resolving methodological disputes | Research design; data interpretation |

| Integration Documentation | Tracks how multiple disciplines shape project outcomes | Ongoing project management; evaluation |

| External Facilitation | Brings neutral perspective to collaboration dynamics | High-stakes decision points; persistent conflicts |

Addressing disciplinary capture requires both conceptual understanding and practical strategies. By making epistemological frameworks explicit, creating structures for equitable participation, and vigilantly monitoring decision-making processes, interdisciplinary teams can avoid the trap of defaulting to a single disciplinary perspective. The protocols and tools provided here offer concrete starting points for researchers committed to achieving the genuine integration that defines successful interdisciplinary work.

The real cost of disciplinary capture is not merely bruised egos or inefficient processes, but compromised science that fails to address complex problems with the full range of available intellectual resources. In fields like pharmaceutical development and biomedical research where innovation matters most, overcoming disciplinary capture is not a luxury—it is a scientific necessity.

Application Note: Quantifying the Problem of Clinical Attrition

Quantitative Analysis of Drug Development Failures

Despite advances in technology and methodology, clinical drug development continues to face a persistently high failure rate. An analysis of clinical trial data from 2010-2017 reveals the primary reasons for failure, which are quantified in the table below [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Clinical Drug Development Failures (2010-2017)

| Failure Cause | Failure Rate (%) | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy | 40-50% | Biological discrepancy between animal models and human disease; inadequate target validation; overreliance on structural-activity relationship (SAR) alone [14]. |

| Unmanageable Toxicity | 30% | Off-target or on-target toxicity; accumulation of drug candidates in vital organs; lack of strategies to optimize tissue exposure/selectivity [14]. |

| Poor Drug-like Properties | 10-15% | Inadequate solubility, permeability, metabolic stability, or pharmacokinetics despite implementation of the "Rule of 5" and other filters [14]. |

| Commercial/Strategic Issues | ~10% | Lack of commercial need; poor strategic planning and clinical trial design [14]. |

This high attrition rate persists even as the pharmaceutical industry increasingly adopts artificial intelligence (AI). Reports indicate that only 5-25% of AI pilot projects in pharma successfully graduate to production systems, creating a new layer of epistemological challenges [15].

The STAR Framework as a Potential Solution

A proposed solution to these systemic failures is the Structure–Tissue Exposure/Selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) framework. This approach aims to correct the overemphasis on potency and specificity by integrating critical factors of tissue exposure and selectivity [14]. The STAR framework classifies drug candidates into distinct categories to guide candidate selection and balance clinical dose, efficacy, and toxicity.

Table 2: STAR Framework Drug Candidate Classification

| Class | Specificity/Potency | Tissue Exposure/Selectivity | Clinical Dose & Outcome | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Low dose required; superior efficacy/safety; high success rate. | Prioritize for development. |

| Class II | High | Low | High dose required; high efficacy but high toxicity. | Cautiously evaluate. |

| Class III | Adequate/Low | High | Low dose required; adequate efficacy with manageable toxicity. | Often overlooked; re-evaluate. |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Inadequate efficacy and safety. | Terminate early. |

Experimental Protocols for Overcoming Epistemological Obstacles

Protocol: Implementing Phenotype-Guided Discovery with Active Learning

This protocol outlines a human-AI collaborative framework designed to overcome the "obstacle of first experience" and "general knowledge" by systematically integrating expert knowledge with AI-driven pattern recognition [15] [16].

1. Objective: To create an iterative discovery loop that strategically uses human expertise to annotate the most ambiguous cases identified by AI, thereby reducing expert annotation burden and mitigating AI overconfidence.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- High-Content Imaging System: For generating high-throughput phenotypic data from cell-based assays.

- Cell Lines/Model Systems: Relevant to the disease pathology under investigation.

- Compound Library: Small molecules or therapeutic agents for screening.

- Labeling Reagents: Fluorescent dyes or antibodies for multiplexed readouts (e.g., cell viability, target engagement, morphological changes).

- Active Learning Software Platform: Computational environment supporting the active learning loop.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Initial Model Seeding. Provide a limited set of human-expert-labeled training examples (100-500) to the AI model.

- Step 2: AI-Driven Uncertainty Quantification. The AI model screens the extensive, unlabeled phenotypical data and identifies areas of highest prediction uncertainty.

- Step 3: Strategic Human Annotation. Human experts selectively annotate only the most ambiguous cases (typically 50-100 edge cases) identified in Step 2, rather than reviewing thousands of instances.

- Step 4: Model Retraining and Iteration. The AI model is retrained on the newly annotated, high-value data. The process loops back to Step 2 until model performance converges to a robust level.

4. Expected Outcome: This protocol can rediscover known therapeutic targets in weeks—a process that traditionally took decades—while maintaining a transparent, human-in-the-loop audit trail [15].

Protocol: Federated Learning for Multi-Institutional Knowledge Integration

This protocol addresses the "substantialist obstacle" and challenges of data silos by enabling collaborative model training across proprietary datasets without data sharing [16] [15].

1. Objective: To build more robust and generalizable AI models for drug discovery by learning from multiple institutions' data while preserving intellectual property and data privacy.

2. Materials:

- Distributed Data Sources: Proprietary molecular libraries, high-throughput screening data, or clinical trial data residing securely at different institutions.

- Federated Learning Software Framework: e.g., MELLODDY or other secure, distributed learning platforms.

- Central Aggregation Server: A secure server that aggregates model updates, not raw data.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Local Model Training. Each participating institution trains a local AI model on its own private, siloed dataset.

- Step 2: Update Transmission. Institutions send only the model updates (e.g., gradients, weights) to a secure central aggregation server. Raw data never leaves the institutional firewall.

- Step 3: Secure Model Aggregation. The central server aggregates these updates using a secure algorithm (e.g., Federated Averaging) to create an improved global model.

- Step 4: Model Redistribution. The updated global model is sent back to all participating institutions.

- Step 5: Iteration. The process repeats, allowing the shared model to learn iteratively from all data sources while the data remains decentralized.

4. Outcome: This approach helps overcome epistemic limitations arising from single-institution biases and small sample sizes, leading to models with improved predictive power and generalizability [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Epistemologically Robust Drug Discovery

| Item | Function/Application | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Content Imaging Assays | Generate multiparametric, phenotypical data from cell-based systems for AI-driven analysis. | Moves beyond single-target reductionism; provides rich data for phenotype-guided discovery and identifying complex mechanisms [15]. |

| Tissue-Specific Bioanalytical Assays (LC-MS/MS) | Quantify drug concentrations in specific disease and normal tissues (Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity Relationship). | Critical for implementing the STAR framework; provides essential data on tissue exposure/selectivity often overlooked by traditional SAR [14]. |

| Diverse Animal Model Panels | Preclinical efficacy and toxicity testing across multiple species and disease models. | Challenges overgeneralization; helps identify biological discrepancies between models and humans before clinical trials [14]. |

| Federated Learning Software Platform | Enables secure, multi-institutional model training without sharing proprietary data. | Addresses data silos and epistemic isolation; builds more robust models by learning from collective, cross-institutional data [15]. |

| Synthetic Data Generation Tools | Create shareable datasets that preserve statistical properties of proprietary data while protecting IP. | Facilitates academic and pre-competitive collaboration; allows for model testing and validation without exposing sensitive data [15]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Modules | Software tools that provide confidence intervals or scores for AI/ML model predictions. | Instills "epistemic humility"; helps researchers identify when a model is operating beyond its knowledge boundaries [15]. |

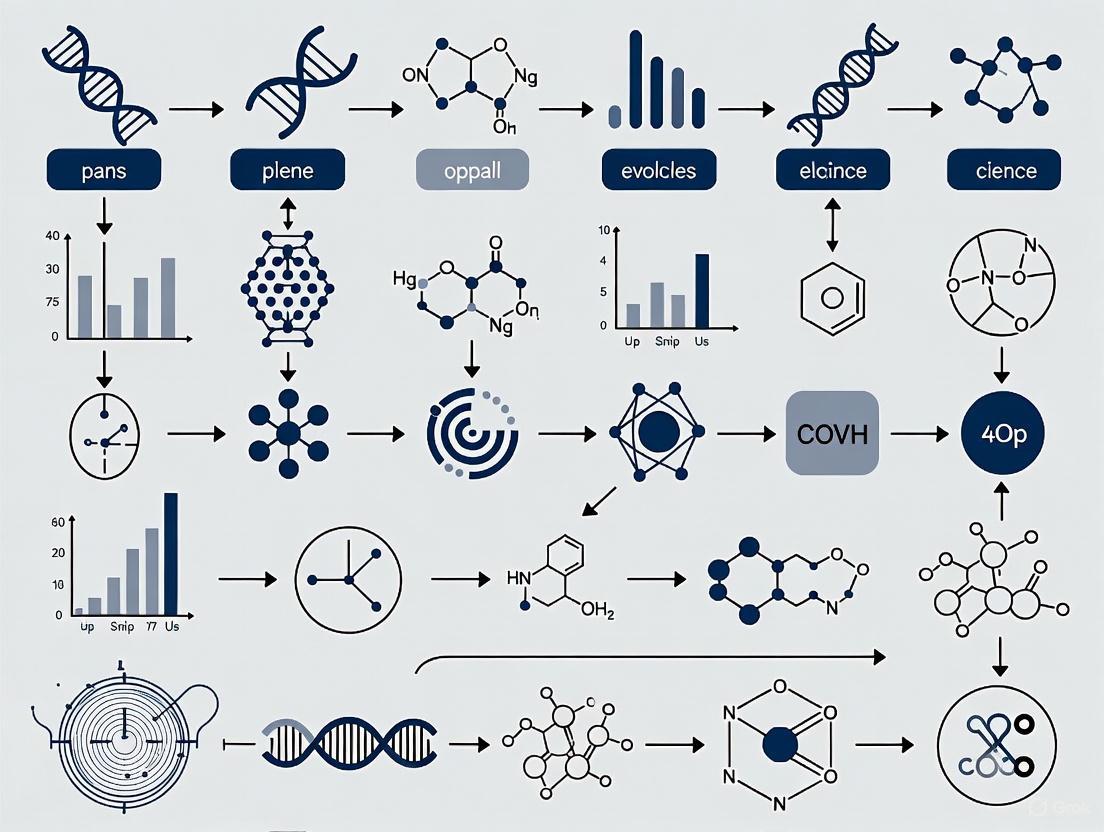

Visualizing the Integrated Framework

The following diagram synthesizes the core components and workflows of an epistemologically robust drug discovery team, integrating the principles, protocols, and tools detailed in this analysis.

The Epistemological Toolbox: Experiential Activities for Building Collaborative Competence

Adapting Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle for Epistemological Awareness

Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) defines learning as "the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience" [17]. This process occurs through a four-stage cycle that is particularly relevant for developing epistemological awareness—the understanding of how knowledge is constructed, validated, and applied within a specific domain. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, epistemological development involves recognizing how knowledge claims are generated and justified within their field, understanding the nature of scientific evidence, and identifying potential epistemological obstacles that may hinder conceptual advancement [18].

The experiential learning cycle comprises four stages: Concrete Experience (feeling), Reflective Observation (watching), Abstract Conceptualization (thinking), and Active Experimentation (doing) [17] [19] [20]. This framework offers a structured methodology for addressing deeply ingrained epistemological obstacles by engaging learners through multiple modes of understanding. The model's emphasis on transforming experience into knowledge aligns directly with the goal of epistemological development, making it particularly valuable for scientific fields where professionals must continually evaluate and refine their understanding of knowledge construction [21].

Theoretical Foundation: Kolb's Framework

The Experiential Learning Cycle

Kolb's model presents learning as an integrated process with four distinct but interconnected stages [17]:

Concrete Experience (CE): The learner encounters a new experience or reinterprets an existing one in a new context. This stage emphasizes feeling over thinking and involves direct sensory engagement with the learning situation [17] [20].

Reflective Observation (RO): The learner consciously reflects on their experience from multiple perspectives, observing carefully and considering the meaning of what they have encountered. This stage emphasizes watching and listening with open-mindedness [17] [21].

Abstract Conceptualization (AC): The learner engages in theoretical analysis, forming abstract concepts and generalizations that explain their reflections. This stage emphasizes logical thinking, systematic planning, and theoretical integration [17] [22].

Active Experimentation (AE): The learner tests their newly formed concepts through practical application, creating new experiences that continue the learning cycle. This stage emphasizes practical doing and decision-making [17] [20].

These stages form a continuous cycle where effective learning requires capabilities in all four modes, though individuals may enter the cycle at any point [17]. The complete cycle enables learners to develop increasingly complex and abstract mental models of their subject matter [17].

Kolb identified four learning styles resulting from preferences along two continuums: the Perception Continuum (feeling versus thinking) and the Processing Continuum (doing versus watching) [17]. These styles represent preferred approaches to learning that influence how individuals engage with epistemological development:

Table: Kolb's Learning Styles and Epistemological Characteristics

| Learning Style | Combination of Stages | Epistemological Orientation | Preferred Knowledge Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diverging | Concrete Experience + Reflective Observation [17] | Views knowledge from multiple perspectives [17] | Personal feedback and group consensus [17] |

| Assimilating | Abstract Conceptualization + Reflective Observation [17] | Values logically sound theories and systematic models [17] | Logical consistency and theoretical coherence [17] |

| Converging | Abstract Conceptualization + Active Experimentation [17] | Prefers practical application of ideas and technical problem-solving [17] | Practical utility and effectiveness in application [17] |

| Accommodating | Concrete Experience + Active Experimentation [17] | Relies on intuition and adaptation to specific circumstances [17] | Hands-on results and adaptability to new information [17] |

Understanding these preferences is crucial for designing interventions that address epistemological obstacles, as individuals may struggle with epistemological development when activities exclusively favor styles different from their preferences [17].

Application Notes: Protocol for Epistemological Awareness

This protocol adapts Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle specifically for developing epistemological awareness in scientific research contexts. The approach is based on successful implementations in medical education where Kolb's cycle has been used to connect clinical practice, theoretical discussion, and simulation [18].

Primary Learning Objectives:

- Identify personal epistemological assumptions about scientific knowledge

- Recognize epistemological obstacles in research practice

- Develop metacognitive awareness of knowledge construction processes

- Apply reflective practices to overcome entrenched conceptual frameworks

- Transfer epistemological insights to novel research scenarios

Target Audience: Researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in knowledge-building activities.

Duration: Complete cycle requires approximately 6-8 hours, which can be distributed across multiple sessions.

Stage-Specific Experimental Protocols

Concrete Experience Protocol: Epistemological Encounter

Purpose: To create a tangible experience that challenges existing epistemological frameworks [18].

Materials Required:

- Research case studies with anomalous data

- Laboratory notebooks for documentation

- Experimental protocols with intentional gaps or contradictions

Procedure:

- Present participants with genuine research scenarios containing data that contradicts established theories or includes ambiguous results.

- Ask participants to engage directly with the scenario by attempting to interpret the data or resolve the contradiction.

- Instruct participants to document their initial hypotheses, reasoning processes, and points of conceptual difficulty.

- Provide limited guidance to allow participants to experience the epistemological challenge authentically.

Implementation Notes:

- The experience should be designed to create cognitive conflict that exposes current epistemological assumptions [18]

- Case studies should be drawn from relevant research domains to maximize engagement and transferability

- Group settings can enhance the experience through shared confrontation with epistemological challenges

Reflective Observation Protocol: Epistemological Reflection

Purpose: To facilitate conscious examination of the epistemological experience from multiple perspectives [18].

Materials Required:

- Guided reflection prompts

- Video recording equipment (optional)

- Peer feedback forms

Procedure:

- Conduct structured individual reflection using prompts focused on:

- Description of the experience without interpretation

- Identification of points of confusion or surprise

- Analysis of assumptions that guided initial approaches

- Consideration of alternative interpretations

- Facilitate small group discussions where participants share their reflections and receive feedback.

- Use guided questions to prompt consideration of how knowledge claims were constructed, validated, or challenged during the experience.

- Incorporate peer observation and feedback to expose participants to diverse perspectives on the same experience.

Implementation Notes:

- Reflection should focus specifically on knowledge construction processes rather than just content understanding [18]

- Facilitators should model metacognitive thinking by verbalizing their own epistemological reflections

- Journaling can be an effective method for capturing reflective observations over time

Purpose: To develop theoretical understanding of epistemological principles and their application to research practice [18].

Materials Required:

- Theoretical frameworks about scientific epistemology

- Concept mapping tools

- Expert input (live or recorded)

Procedure:

- Present relevant epistemological frameworks that help explain the challenges encountered in the concrete experience.

- Guide participants in comparing their reflective observations with established epistemological concepts.

- Facilitate concept mapping exercises where participants visually represent relationships between epistemological concepts and their research experiences.

- Provide expert input that explicitly connects theoretical epistemological principles with practical research applications.

- Support participants in developing personalized epistemological frameworks that integrate new conceptual understanding with their research practice.

Implementation Notes:

- Theoretical input should be tightly connected to participants' specific reflective observations [18]

- Concepts should be presented as tools for understanding rather than as content to be memorized

- Participants should be guided to develop their own explicit epistemological principles rather than simply adopting presented frameworks

Active Experimentation Protocol: Epistemological Practice

Purpose: To test and apply new epistemological understanding in simulated or authentic research contexts [18].

Materials Required:

- Simulated research scenarios

- Protocol development templates

- Feedback mechanisms

Procedure:

- Design research-like tasks that require application of newly developed epistemological frameworks.

- Ask participants to develop research plans that explicitly articulate their epistemological approach.

- Implement simulated research scenarios where participants can practice their new epistemological awareness with structured feedback.

- Create opportunities for participants to test alternative epistemological approaches to the same research problem.

- Provide guided reflection on the outcomes of different epistemological approaches.

Implementation Notes:

- Simulations should provide safe environments for epistemological experimentation without high-stakes consequences [18]

- Feedback should focus on the process of knowledge construction rather than just the correctness of outcomes

- Participants should be encouraged to consciously apply their epistemological frameworks rather than revert to automatic approaches

Implementation Case Study: Medical Education Application

A documented implementation at the Technical University of Munich demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach [18]. In this case, medical students participated in a structured program that followed Kolb's cycle to develop clinical reasoning skills with explicit epistemological components:

Program Structure:

- Concrete Experience: Students selected patients during clinical clerkships based on specific chief complaints [18].

- Reflective Observation: Students documented and reflected on their clinical experiences, focusing on their diagnostic reasoning processes [18].

- Abstract Conceptualization: In seminars with experienced practitioners, students presented cases, received theoretical input, and discussed clinical reasoning models [18].

- Active Experimentation: Students applied their refined conceptual understanding in simulated patient scenarios with standardized patients [18].

Results: Quantitative evaluation showed positive reception with an average rating of 1.4 (on a 1-6 scale where 1=very good) for the seminar component and 1.6 for the simulation training [18]. Qualitative feedback indicated that students valued discussing personally experienced patient cases and the opportunity to practice similar cases in a simulated environment [18].

Visualization of the Adapted Model

The following diagram illustrates the adapted experiential learning cycle for epistemological awareness, highlighting the specific processes and outcomes at each stage:

Diagram 1: The Epistemological Awareness Learning Cycle. This adaptation of Kolb's model emphasizes the transformation of epistemological understanding through successive stages of experience, reflection, conceptualization, and experimentation.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Components

Successful implementation of this protocol requires specific methodological components that function as "research reagents" to facilitate the epistemological development process:

Table: Essential Methodological Components for Epistemological Awareness Development

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Anomalous Case Studies | Creates cognitive conflict that exposes epistemological assumptions [18] | Research scenarios with contradictory data that challenge established theories |

| Structured Reflection Prompts | Guides metacognitive examination of knowledge construction processes [18] | Question sequences that prompt analysis of how conclusions were reached |

| Epistemological Frameworks | Provides conceptual tools for understanding knowledge validation [18] | Theoretical models describing forms of scientific evidence and argumentation |

| Simulated Research Environments | Allows safe experimentation with epistemological approaches [18] | Controlled scenarios where participants test knowledge-building strategies |

| Multi-perspective Analysis Tools | Facilitates examination of knowledge claims from different viewpoints [17] | Protocols for evaluating evidence from contrasting theoretical perspectives |

| Concept Mapping Resources | Supports visualization of epistemological relationships [18] | Digital or physical tools for creating concept maps of knowledge structures |

The adaptation of Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle for epistemological awareness provides a structured methodology for addressing deeply ingrained obstacles to conceptual change in scientific fields. By engaging researchers through the complete cycle of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation, this approach enables meaningful development in how knowledge is understood, constructed, and validated.

The protocols outlined here offer practical tools for implementing this approach in various research contexts, from individual laboratory settings to formal research training programs. The case study from medical education demonstrates the potential effectiveness of this approach when implemented with careful attention to the connections between different learning stages [18].

Future research should explore specific applications within drug development contexts, examine the long-term impact on research practices, and investigate how digital tools might enhance the implementation of these protocols in distributed research teams. By making epistemological development an explicit focus of research training, this approach has the potential to enhance scientific innovation and address persistent conceptual obstacles that hinder scientific progress.

Application Notes

The Interdisciplinary Fishbowl is a structured discussion technique designed to facilitate the observation and analysis of disciplinary reasoning patterns among diverse experts, particularly within the context of epistemological obstacle overcoming research. This protocol creates a controlled environment where researchers can document how specialists from different fields articulate foundational concepts, confront conceptual hurdles, and negotiate meaning across disciplinary boundaries.

Core Theoretical Context: Within epistemological obstacle research, this activity serves as a methodological tool to identify and examine discipline-specific reasoning barriers that emerge during collaborative problem-solving. The fishbowl's structured format makes the often-implicit processes of disciplinary thinking explicit and available for systematic analysis.

Experimental Protocol & Methodology

Participant Recruitment and Group Formation

Table 1: Participant Group Composition and Roles

| Group Role | Number of Participants | Primary Discipline(s) | Prerequisite Expertise | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Circle (Discussants) | 4-6 | Varied (e.g., Medicinal Chemistry, Pharmacology, Clinical Science) | Senior Researcher or above | Articulate disciplinary reasoning and engage in dialogue. |

| Outer Circle (Observers) | 4-6 | Complementary to Inner Circle | Mid-level to Senior Researcher | Systematically document reasoning patterns and epistemic exchanges. |

| Facilitator | 1 | Science of Team Science, Psychology | Experienced in group dynamics | Guide discussion flow, ensure protocol adherence, and manage time. |

| Data Analyst | 1-2 | Qualitative Research Methods | Expertise in discourse analysis | Code and analyze recorded sessions and observation notes. |

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application in Protocol | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Protocol Case | Presents a pre-validated, complex interdisciplinary problem scenario to initiate discussion. | Must contain sufficient disciplinary depth to engage all expert participants. |

| Structured Observation Instrument | Standardized form for real-time coding of discursive events and reasoning patterns. | Includes fields for timestamp, speaker, discipline, and observed reasoning type. |

| Audio/Video Recording System | Captures full verbal and non-verbal communication for subsequent granular analysis. | Multi-angle setup to capture both inner and outer circle participants. |

| Epistemic Coding Framework | A pre-defined schema for classifying types of epistemological obstacles and reasoning moves. | Framework should be piloted and refined prior to main study. |

| Post-Session Debrief Guide | Semi-structured questionnaire to elicit participant reflection on the discussion process. | Probes perceived obstacles, moments of clarity, and interdisciplinary negotiation. |

Step-by-Step Procedural Workflow

Phase 1: Pre-Activity Preparation (Approx. 1 week prior)

- Distribute the Stimulus Protocol Case and foundational reading materials to all participants.

- Conduct brief individual interviews with participants to establish baseline understanding of key concepts.

- Train observers on the use of the Structured Observation Instrument and the Epistemic Coding Framework.

Phase 2: Fishbowl Discussion Execution (Total Time: 90-120 minutes)

- Orientation (10 minutes): The facilitator outlines the rules, goals, and timeline. The inner circle is seated in the center, surrounded by the outer circle.

- Initial Reasoning Presentation (20 minutes): Each inner circle participant sequentially presents their discipline's initial approach to the problem case, highlighting core assumptions and potential challenges.

- Open Disciplinary Dialogue (30 minutes): Facilitated discussion among inner circle participants. They are encouraged to question each other's reasoning, identify points of friction or synergy, and work toward an integrated approach.

- Observer Integration (20 minutes): Outer circle observers pose clarifying questions to the inner circle based on their initial observations, probing specific reasoning moves.

- Role Switch and Iteration (30 minutes): Inner and outer circle participants switch places, and a new, related problem facet is discussed, allowing for comparative observation.

- Full Group Synthesis (10 minutes): The facilitator leads a brief open discussion on emerging interdisciplinary insights and persistent obstacles.

Phase 3: Post-Activity Data Collection (Immediately following)

- Administer the Post-Session Debrief Guide to all participants.

- Collect and digitize all completed Structured Observation Instruments.

- Secure and backup all audio/video recordings for analysis.

Data Presentation and Analysis Framework

Table 3: Primary Quantitative Metrics for Analysis

| Metric Category | Specific Measurable Variable | Data Source | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discursive Engagement | - Talk time per discipline- Number of turns per participant- Frequency of cross-disciplinary questioning | Audio/Video Recording | Descriptive Statistics, ANOVA |

| Epistemic Move Frequency | - Instances of assumption articulation- Challenges to another discipline's premise- Proposals for integration | Structured Observation Instrument, Transcripts | Content Analysis, Frequency Counts |

| Obstacle Identification | - Count of unique epistemological obstacles coded- Discipline of origin for each obstacle- Resolution status (persisted/resolved) | Epistemic Coding Framework Application | Qualitative Thematic Analysis |

| Interaction Pattern | - Network density of conversational turns- Centralization of discussion around specific disciplines | Structured Observation Instrument | Social Network Analysis |

Visualization of Workflow and Logical Relationships

Fishbowl Activity Setup

Epistemological Analysis Pathway

Application Notes

Troika Consulting is a structured peer-consultation method designed to help individuals gain insight into challenges and unleash local wisdom to address them. In quick round-robin consultations, individuals ask for help and receive immediate advice from two colleagues [23]. This peer-to-peer coaching is highly effective for discovering everyday solutions, revealing patterns, and refining prototypes, extending support beyond formal reporting relationships [23].

Within the context of epistemological obstacle research in drug development, this method is particularly valuable. It creates a forum for professionals to articulate and dissect hidden cognitive barriers—such as overgeneralization from single experimental results (generalized obstacle) or substantialist thinking about biological targets as immutable entities—that can impede scientific progress [16]. By fostering a culture of mutual aid and critical questioning, the protocol directly engages with Bachelard's concept of "epistemological obstacles," which are internal impediments in the very act of knowing that arise from functional necessity [16].

The activity is especially suited for cross-disciplinary teams where diverse expertise can challenge domain-specific assumptions. For example, a biologist's "animist obstacle" of attributing agency to a disease pathway might be effectively questioned by a chemist's mechanistic perspective [16]. This structured interaction helps build trust within a group through mutual support and develops the capacity to self-organize, creating conditions for unimagined solutions to complex research problems to emerge [23].

Table 1: Summary of Troika Consulting Applications in Research Settings

| Application Context | Primary Purpose | Targeted Epistemological Obstacles | Expected Research Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-clinical Project Review | Challenge assumptions in experimental design and data interpretation [24]. | Realist obstacle (over-reliance on concrete analogies), quantitative obstacle (decontextualized data) [16]. | Refined experimental models; improved validity of target identification. |

| Clinical Trial Strategy | Address challenges in patient stratification, endpoint selection, and data analysis [25]. | General knowledge obstacle (over-generalization), substantialist obstacle (static disease definitions) [16]. | More robust trial designs; enhanced patient cohort definitions. |

| Data Integration & KGs | Troubleshoot issues in unifying disparate biological data into a coherent knowledge graph [25] [24]. | Verbal obstacle (ambiguous terminology), animist obstacle (personifying abstract systems) [16]. | Higher quality, more interoperable data resources; better semantic alignment. |

| Cross-functional Team Meetings | Solve collaborative challenges between research, development, and regulatory teams. | Obstacle of first experience (biases from prior projects) [16]. | Accelerated project timelines; improved mutual understanding across disciplines. |

Experimental Protocol

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Troika Consulting Implementation

| Item Name | Type/Specifications | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Session Facilitator | Human resource; experienced in Liberating Structures [23]. | To briefly explain the activity, keep time for the overall session, and ensure adherence to the structure. |

| Participant Trios | Small groups of 3 researchers/knowledge workers [23] [26]. | To form the core consulting units where the roles of client and consultants are rotated. |

| Timing Device | Timer or stopwatch application. | To enforce strict time allocations for each phase of the consultation rounds. |

| Problem Formulation Guide | Document with prompting questions (e.g., "What is your challenge?" "What kind of help do you need?") [23]. | To assist participants in refining their consulting question before the activity begins. |

| Reflective Space | Physical space with knee-to-knee seating preferred (no table) or virtual breakout rooms [23] [27]. | To create an intimate, focused environment conducive to open dialogue and active listening. |

Methodology

Step 1: Preparation and Participant Briefing

- Convene researchers and briefly introduce the purpose of the session, framing it within the context of overcoming specific research challenges and epistemological obstacles [16].

- Form small groups of three participants each. Groups should ideally comprise individuals with diverse backgrounds and perspectives for the most helpful consultations [23].

- In a virtual setting, use breakout rooms to facilitate the trio formations [26].

Step 2: Individual Reflection

- Allocate 1 minute for all participants to silently reflect on and formulate their specific consulting question. They should consider: "What is your current research challenge?" and "What specific help do I need?" [23].

Step 3: Structured Consultation Rounds (Repeat for each participant in the trio) The following sequence is performed for each member of the trio acting as the "client," with the other two as "consultants." One consultant can also serve as the timekeeper [27].

- Client Presents Challenge: The first client shares their question with the two consultants clearly and concisely. (Time: 2 minutes)

- Consultants Ask Clarifying Questions: Consultants ask only open-ended, clarifying questions to better understand the situation. They must refrain from giving advice or suggestions at this stage. (Time: 2 minutes)

- Client Turns Around/Disengages: The client turns around (in person) or turns off their camera and mutes their microphone (online) [26] [27]. This is a critical step that reduces client defensiveness and frees the consultants to speak candidly.

- Consultants Generate Ideas: The two consultants discuss the client's challenge with each other. They generate ideas, suggestions, and coaching advice. They should aim to "respectfully provoke by telling the client what you see that you think they do not see" [23]. Questions that spark self-understanding may be more powerful than direct advice. (Time: 5 minutes)

- Client Feedback: The client turns back (or turns their video on) and shares with the consultants what was most valuable or insightful about the conversation they overheard. The client has agency and is not obligated to accept all advice. (Time: 2 minutes)

Step 4: Role Rotation

- The trio repeats Step 3, rotating roles so that each person has an opportunity to be the client and receive consultation.

Step 5: Group Debrief (Optional but Recommended)

- Reconvene the larger group and facilitate a brief plenary discussion. A prompt such as "What is one actionable insight which came out of that for you?" can be effective [27].

Troika Consulting Process Flow

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 3: Quantitative Framework for a 3-Participant Troika Consulting Session

| Phase / Activity | Cumulative Elapsed Time (Minutes) | Duration per Participant (Minutes) | Cumulative Duration per Role (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session Introduction | 0 - 5 | N/A | N/A |

| Individual Reflection | 5 - 6 | 1 | 1 (as Reflector) |

| Round 1: Participant A as Client | |||

| - Client Presentation | 6 - 8 | 2 | 2 (as Client) |

| - Clarifying Questions | 8 - 10 | 2 | 2 (as Consultant) |

| - Consultant Brainstorming | 10 - 15 | 5 | 5 (as Consultant) |

| - Client Feedback | 15 - 17 | 2 | 2 (as Client) |

| Round 2: Participant B as Client | 17 - 27 | 10 | 2 (as Client) + 8 (as Consultant) |

| Round 3: Participant C as Client | 27 - 37 | 10 | 2 (as Client) + 8 (as Consultant) |

| Group Debrief | 37 - 45 | ~3 | N/A |

| TOTALS | 45 | ~23 | ~10 (Client)\n~15 (Consultant) |

The protocol's efficacy stems from its ability to mitigate specific epistemological obstacles through structured social interaction [16]. For instance, the "consultant brainstorming" phase, conducted without the client's direct engagement, directly counters the "obstacle of first experience" and "general knowledge obstacle" by allowing for speculative and creative idea generation that is not immediately constrained by the client's initial framing or personal biases [23] [27] [16]. The requirement for the client to then provide feedback on what was most valuable empowers them to self-correct and identify which suggestions effectively bypass their own cognitive blocks.

Knowledge Graph Refinement via Troika Consulting

Application Notes

Theoretical Foundation and Purpose

Appreciative Interviews are a qualitative research technique grounded in Appreciative Inquiry, Social Constructionism, and the narrative turn in psychology [28]. This method is deliberately designed to shift the research focus from identifying deficits to uncovering existing epistemological strengths and successful reasoning strategies within a research team or student cohort.

In the context of epistemological obstacle overcoming research, this activity helps participants and researchers identify and articulate moments of breakthrough or exceptional conceptual understanding. By recalling and analyzing these "peak experiences" in research or learning, the method makes latent, often unarticulated, cognitive strengths visible, providing a robust foundation for developing more effective pedagogical and research strategies [28] [29].

Key Advantages for Scientific Research

- Strength-Based Framework: Moves beyond traditional deficit-based analysis that focuses on what is wrong or missing, which can be counterproductive. Instead, it identifies what is working well to create more positive and sustainable outcomes [29].

- Empowerment and Agency: The interview process itself can be a transformative and empowering experience for participants, fostering increased confidence in their cognitive abilities and problem-solving capacities [28].

- Uncovering Tacit Knowledge: Effectively surfaces tacit knowledge and successful but unrecorded reasoning processes that are often hidden in standard research methodologies [30].

Experimental Protocol

Pre-Interview Planning and Materials

1. Interview Guide Development:

- Craft a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions designed to elicit rich, narrative responses [29].

- Core questions should follow the 4-D Cycle (Discovery, Dream, Design, Destiny) of Appreciative Inquiry [28].

- Essential Materials: Digital audio recorder, consent forms, interview guide with note-taking space, timer [31].

2. Participant Briefing:

- Clearly explain the unique, strength-based nature of the interview to set expectations. Frame it as an exploration of success and effective thinking, not problem-solving [30].

Interview Execution

The interview should be conducted in a quiet, private setting to ensure confidentiality and minimize distractions. The recommended flow involves three distinct phases [28]:

1. Opening Phase (Building Rapport):

- Begin with gentle, open-ended questions to put the participant at ease.

- Example Question: "Can you tell me about a time in your research or studies when you felt particularly engaged and successful in solving a complex problem?" [28]

2. Core Phase (The 4-D Cycle in Practice): This is the main data collection segment, progressing through focused, positive questioning.

- Discovery (Peak Experience): Ask the participant to recount a specific, concrete story of a "peak experience" or significant breakthrough in their research or learning. Prompt them to include details about the context, their actions, thoughts, and feelings [28] [29].

- Dream (Envisioning the Ideal): Invite the participant to envision an ideal future. Example Question: "If you could have that level of clarity and success in all your research endeavors, what would that look like? Imagine no constraints." [28]

- Design (Co-Constructing Conditions): Focus on the identified strengths and the ideal vision to articulate the conditions that enable such success. Example Question: "What are the key elements, resources, or ways of thinking that would need to be in place to make that ideal a reality?" [30]

- Destiny (Action and Momentum): Conclude the core phase by focusing on forward momentum. Example Question: "What is one small step you can take to move toward that ideal?" [28]

3. Closing Phase (Reflection and Validation):

- Allow the participant to reflect on the interview experience.

- Thank them for their contributions and reiterate the value of their insights [28].

Post-Interview Data Management and Analysis

1. Data Management:

- Transcribe audio recordings verbatim.

- Anonymize transcripts by removing identifying information and assigning participant codes (e.g., R1 for Researcher 1).

- Import anonymized transcripts into qualitative data analysis software (e.g., NVivo, MAXQDA) for systematic coding.

2. Thematic Analysis: Follow Braun and Clarke's six-step framework for thematic analysis [29]: 1. Familiarization: Immersion in the data by reading and re-reading transcripts. 2. Generating Initial Codes: Systematically coding interesting features across the entire dataset. 3. Searching for Themes: Collating codes into potential themes. 4. Reviewing Themes: Checking themes against the coded data and entire dataset. 5. Defining and Naming Themes: Refining the specifics of each theme and generating clear definitions and names. 6. Producing the Report: Selecting vivid, compelling extract examples and finalizing the analysis.

Table 1: Summary of Quantitative Metrics for Data Management

| Management Stage | Key Metric | Description | Purpose in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription | Verbatim Accuracy | Word-for-word transcription fidelity. | Ensures data integrity and minimizes analyst bias. |

| Anonymization | Participant Code Ratio | Ratio of identifiable data removed to total data. | Protects participant confidentiality as per ethical standards. |

| Data Cleaning | Missing Data Percentage | % of questions or data points not addressed. | Identifies potential gaps in the interview guide or data set. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential methodological "reagents" required to conduct the Appreciative Interview experiment effectively.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation | Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | Serves as the primary protocol to ensure consistency while allowing for exploratory probing. | Contains pre-written open-ended questions following the 4-D cycle [28]. |

| Qualitative Data Analysis Software | The computational engine for organizing, coding, and analyzing textual data. | Software platforms like NVivo or MAXQDA. |

| Digital Audio Recorder | Primary tool for accurate data capture during the interview. | A reliable device with high-fidelity recording and long battery life. |

| Informed Consent Form | The ethical foundation of the research, ensuring participant autonomy and compliance. | Outlines study purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, and confidentiality [31]. |

| Thematic Codebook | The standardized reference for analysis, ensuring coding consistency between researchers. | Contains code definitions, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and example quotes [29]. |

Workflow and Thematic Relationship Diagrams

Appreciative Interview Workflow

Epistemological Strength Themes

Application Notes