Bridging the Knowledge Gap: Evidence-Based Strategies for Overcoming Alternative Conceptions in Evolution Education for Scientific Professionals

This article provides a comprehensive framework for addressing deeply held alternative conceptions in evolution education, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Bridging the Knowledge Gap: Evidence-Based Strategies for Overcoming Alternative Conceptions in Evolution Education for Scientific Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for addressing deeply held alternative conceptions in evolution education, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the most common and persistent misconceptions, including teleological and anthropomorphic reasoning, and synthesizes the latest research on effective intervention strategies. The content moves from foundational theory to practical application, offering methodologies for identifying misconceptions, implementing conceptual change techniques, and validating educational outcomes. By integrating insights from science education research and biomedical contexts, this article aims to enhance scientific literacy and critical thinking, which are fundamental for rigorous research and innovation in the biomedical sciences.

Mapping the Conceptual Landscape: Identifying and Categorizing Common Evolutionary Misconceptions

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides researchers and scientists with diagnostic frameworks and experimental protocols to address common alternative conceptions in evolution education.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Alternative Conceptions

| Reported Issue | Diagnostic Questions | Root Cause Identification | Recommended Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teleological Reasoning("Trait exists for a purpose") | • "Are you saying the trait developed in order to achieve that function?"• "What is the evidence that need causes evolutionary change?" | Student conflates evolutionary mechanism (natural selection) with conscious intent or predetermined goals [1]. | Use fruit fly selection experiments to demonstrate trait frequency changes without purposeful direction [2]. |

| Anthropomorphic Conceptions("Organisms 'want' to evolve") | • "What specific mechanism would cause that change?"• "Are you attributing human-like awareness to the organism?" | Student transfers human characteristics like intentionality or mental abilities to biological entities [1]. | Contrast student explanations with scientific norms of objectivity and neutrality through Socratic dialogue [1]. |

| Lamarckian Inheritance("Use-disuse shapes offspring") | • "Can you trace the genetic mechanism for this acquired trait?"• "How would a somatic change become heritable?" | Student holds pre-Darwinian view that individually acquired adaptations can be passed to offspring [2]. | Fast Plants experiments demonstrate environmental adaptation without heritability [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Variation and Selection

Objective: Test the null hypothesis that selection cannot alter trait frequency in subsequent generations [2].

Materials:

- Wild-type ("flier") and vestigial-winged ("crawler") Drosophila melanogaster populations

- Flynap anesthetic

- Fly medium

- 2-liter plastic bottles

- Construction materials: threads, straws, double-sided tape, flypaper, water moats, petroleum jelly, external light sources

Methodology:

- Divide research teams into two groups: one selecting for wild-type phenotype, the other for vestigial-winged phenotype.

- Introduce equal numbers of male and female flies of both phenotypes into experimental and control chambers.

- Allow experiments to run until flies produce at least first generation offspring.

- Record differential mortality and phenotype distribution across generations.

Expected Outcomes: Selection for wild-type fliers typically increases their frequency, while selection against vestigial-winged crawlers is often less successful, demonstrating that selection pressures vary in effectiveness [2].

Quantitative Data from Student Experiments

Table 1: Variation in Seed Characteristics [2]

| Parameter Measured | Distribution Pattern | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Seed Length | Approximates normal distribution | Variation is measurable and distinct |

| Seed Mass | Almost evenly distributed across size classes | Challenges assumption that size correlates directly with mass |

| Color Pattern | Similar to mass distribution | Demonstrates random, non-purposeful variation |

Table 2: Fruit Fly Selection Experimental Data [2]

| Experimental Condition | Starting Population | Ending Population | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (no selection) | 10 fliers, 10 crawlers | 158 fliers, 38 crawlers | Baseline reproduction without selective pressure |

| Selection for Fliers | 10 fliers, 10 crawlers | 245 fliers, 78 crawlers | Demonstration of successful selection pressure |

| Selection for Crawlers | 10 fliers, 10 crawlers | 81 fliers, 23 crawlers | Challenges of effective selective barriers |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most resistant alternative conceptions in evolution education?

Teleological and anthropomorphic conceptions are particularly entrenched. Students routinely explain evolutionary processes by interpreting function as cause or attributing intentionality to natural processes. These conceptions persist because they align with everyday experiences and common sense reasoning [1].

Why do these conceptions persist despite conventional instruction?

Conventional instruction induces only small changes in student beliefs because these qualitative, common-sense beliefs have a large effect on performance. The basic knowledge gain under conventional instruction is essentially independent of the instructor, indicating a need for changed methodology [2].

What teaching strategies effectively address Lamarckian misconceptions?

Using Lamarck's theory as an initial framework allows students to confront its limitations directly. By constructing concept maps of Lamarckian theory and identifying testable hypotheses, students can experimentally falsify elements like inheritance of acquired characteristics [2].

How can instructors distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate teleology?

Illegitimate "design teleology" explains traits as existing for a predetermined purpose, while legitimate "selection teleology" references the evolutionary processes of natural selection without implying intention. Criteria include examining whether explanations reference mechanistic processes versus conscious design [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Evolution Education Research

| Item | Function in Experiment | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin Fast Plants (Brassica rapa) | Rapid life cycle allows observation of multiple generations | Studying adaptation without heritability; developmental plasticity [2] |

| Drosophila melanogaster populations | Distinct phenotypes with known genetic basis | Selection experiments demonstrating trait frequency changes [2] |

| Pecan fruits/Sunflower seeds | Natural variation in measurable characteristics | Quantitative analysis of variation in populations [2] |

| Concept Mapping Tools | Visual representation of conceptual relationships | Identifying testable hypotheses and conceptual relationships [2] |

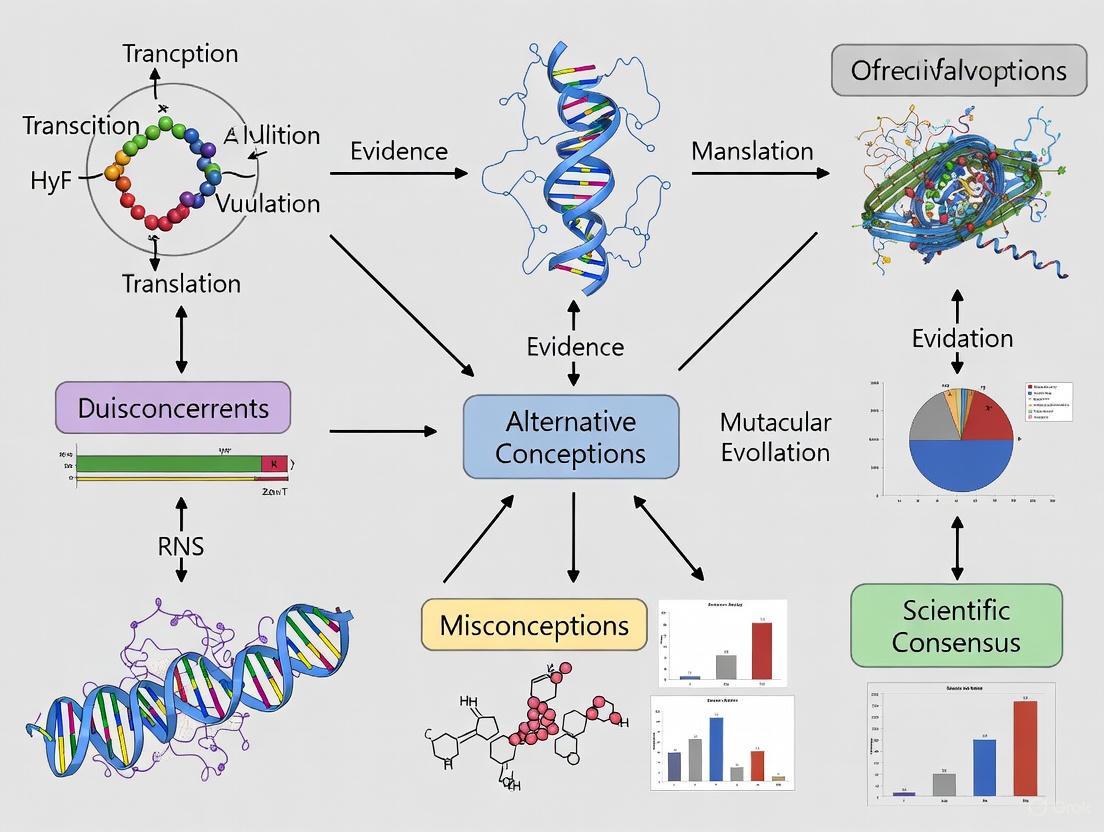

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Conceptual Change Pathway

FAQs: Documenting Misconceptions in Evolution Education

1. What are the most prevalent misconceptions about evolution among non-STEM majors? Research indicates that non-STEM majors often hold significant misconceptions about core evolutionary concepts. A five-year study with Colombian undergraduates revealed a limited understanding of microevolution and demonstrated only a moderate overall grasp of evolutionary theory [3]. Common alternative conceptions include teleological reasoning (the idea that evolution is a goal-directed process, such as believing traits develop because they are "needed") and difficulties understanding that evolution acts on populations, not individuals [3] [4].

2. How do misconceptions differ between STEM and non-STEM populations? Longitudinal data suggests that while differences in understanding exist, they are not always as statistically significant as assumed. One study found that despite apparent differences in scores between STEM and non-STEM majors, these differences were not reliable upon statistical analysis [3]. However, other research confirms that biology majors consistently outperform non-STEM majors on evolution knowledge assessments, though all groups exhibit room for improvement [3].

3. What methodologies are effective for documenting and quantifying these misconceptions? A robust method involves using standardized questionnaires and surveys to collect data over extended periods. One protocol employed an 11-item questionnaire administered over 10 academic semesters (5 years) to track student understanding [3]. For qualitative insights, analyzing open-ended survey responses and student reflections on learning materials (like comics or narratives) can reveal how students conceptualize terms like variation, natural selection, and heredity [4].

4. What is the "therapeutic misconception" in research and how does it relate to this context? The "therapeutic misconception" is a documented phenomenon where research participants conflate the goals of clinical research with personalized clinical care, often overestimating their personal benefit [5] [6]. This represents a broader pattern of misunderstanding complex systems. Similarly, in evolution education, learners often misconstrue the impersonal, population-level process of natural selection as a purposeful, individual-level mechanism, indicating a parallel conceptual challenge in understanding non-intentional, probabilistic systems [4].

5. How can we address sophisticated, resistant misconceptions in educated populations? For sophisticated misconceptions deeply embedded in a learner's conceptual framework, traditional "refutational" approaches that directly contradict the misconception may be less effective. An assimilation-based method is proposed, which leverages a student's existing knowledge as a foundation to build correct understanding, rather than outright rejecting their initial conceptions. This involves using a series of sequenced analogies where the correct understanding from one analogy provides the foundation for addressing the next [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Research on Evolution Misconceptions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution/Suggested Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Low participant understanding scores across all groups. | Assessment tool may not discriminate between nuanced levels of understanding; concepts not taught effectively. | Protocol: Validate instrument with think-aloud protocols. Use a mixed-methods approach (e.g., combine multiple-choice surveys with open-ended questions) to capture conceptual depth [3] [4]. |

| Resistance to conceptual change after standard instruction. | Misconceptions may be "sophisticated" and integrated into the learner's conceptual ecology, making them resistant to simple correction. | Protocol: Implement an assimilation-based teaching intervention. Develop a series of connected analogies that build on each other to gradually reshape understanding, rather than directly refuting the initial idea [7]. |

| Participants demonstrate teleological reasoning (goal-oriented explanations). | Deep-seated cognitive bias to attribute purpose to natural phenomena; may be reinforced by everyday language. | Protocol: Use narrative-based learning tools (e.g., specially designed comic books) that explicitly model population-level, non-goal-directed evolutionary processes through character stories [4]. |

| No significant difference found between STEM and non-STEM majors. | Sample size may be too small; the assessment tool may not be sensitive enough; STEM majors may also hold key misconceptions. | Protocol: Ensure adequate statistical power in study design. Conduct a cross-sectional analysis of differences across demographic variables (age, gender, major) and perform longitudinal tracking to monitor changes over time [3]. |

| Students conflate terminology (e.g., individual adaptation vs. population evolution). | Informal prior knowledge interfering with formal scientific definitions. | Protocol: Utilize conceptual inventories (e.g., Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection) to diagnose specific conflation points. Follow with targeted activities that force discrimination between concepts [3] [4]. |

Quantitative Data on Evolution Misconceptions

The table below summarizes key findings from a five-year study of undergraduate misconceptions, highlighting patterns across different groups [3].

| Participant Group | Sample Size | Overall Understanding of Evolution | Specific Conceptual Weakness | Notable Statistical Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEM Majors | 547 (Total for study, incl. non-STEM) | Moderate | Limited understanding of microevolution | Differences in scores between STEM and non-STEM majors were not statistically significant. |

| Non-STEM Majors | (Subset of above) | Moderate | Teleological reasoning; individual vs. population change | |

| Biology Undergraduates (German Study) | 136 | Mean Score: 17.9/29 | (Data not specified in source) | Biology students scored higher than non-biology and high school students. |

| Non-Biology Undergraduates (German Study) | 124 | Mean Score: 16.2/29 | (Data not specified in source) | Scored between biology undergraduates and high school students. |

Experimental Protocol: Using Narrative Tools to Document and Address Misconceptions

Aim: To document the presence of common alternative conceptions about evolution and assess the effectiveness of a narrative-based comic book in facilitating conceptual change.

Background: Comics are multimodal texts that combine images and sequential narratives, which can enhance understanding of complex scientific concepts like variation, natural selection, and heredity [4].

Materials:

- Specially designed science comic (e.g., "Cats on the Run – A Dizzying Evolutionary Journey").

- Pre- and post-intervention survey (including multiple-choice and open-ended questions).

- Audio recording equipment for focus group discussions (optional).

Methodology:

- Pre-Assessment: Administer a survey to participants (e.g., Grade 4-6 students or older) to establish a baseline of their understanding of evolution. Include questions designed to reveal teleological reasoning or other common misconceptions [4].

- Intervention: Integrate the comic book into standard biology lessons. The narrative should follow characters encountering evolutionary concepts in a story context.

- Post-Assessment: After the intervention, administer a follow-up survey with questions comparable to the pre-assessment.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantitative: Score the pre- and post-surveys to measure changes in correct answers.

- Qualitative: Thematically analyze open-ended responses. Code for references to the comic's narrative and imagery, and check for persistence of non-scientific explanations (e.g., goal-directed adaptation) versus the use of scientific principles (e.g., random variation and selection) [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential "reagents" or tools for researching misconceptions in evolution education.

| Research Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Standardized Conceptual Inventories (e.g., CINS) | Quantitatively diagnose specific, common alternative conceptions about a topic like natural selection in a pre-/post-test design [3]. |

| Demographic Questionnaire | Collects data on variables like age, gender, and major (STEM/non-STEM) to analyze patterns in misconception prevalence [3]. |

| Semi-Structured Interview Protocol | Provides qualitative depth, allowing researchers to explore the reasoning behind a student's survey answers and uncover nuanced misunderstandings [4]. |

| Narrative-Based Learning Tool (e.g., Comic Book) | Serves as an intervention tool; its multimodal and story-driven format can make abstract concepts more accessible and reveal learning pathways through student reflections [4]. |

| Coding Framework for Thematic Analysis | A systematic protocol for analyzing qualitative data (e.g., interview transcripts, open-ended survey responses) to identify and categorize recurring misconceptions [4] [7]. |

Conceptual Change Workflow Diagram

FAQs: Understanding Intuitive Conceptions

What is an "intuitive conception" in science learning? An intuitive conception is a nonscientific idea or cognitive shortcut (a heuristic) that individuals use for fast and spontaneous reasoning about natural phenomena. These conceptions are often useful in everyday life but can be misleading in scientific contexts, interfering with the learning of accurate scientific concepts [8].

Why are some misconceptions so persistent, even after instruction? Intuitive conceptions are persistent because they are often deeply anchored and frequently reinforced in everyday life. Research shows they can coexist with scientifically correct knowledge in an individual's mind. Even after formal instruction, these heuristics are not erased but remain, requiring active suppression in specific contexts [8].

What is the role of "inhibitory control" in overcoming misconceptions? Inhibitory control is the cognitive ability to resist automatisms, distractions, or interference. In scientific reasoning, it allows an individual to suppress a tempting but inaccurate intuitive answer in favor of a less intuitive but scientifically correct one. Neurocognitive studies show that correctly evaluating counterintuitive scientific claims is associated with higher activation in brain regions responsible for this inhibitory control [8].

What are common sources of misconceptions in evolution? Students encounter evolution misconceptions from many sources, including:

- Popular media: A study found that 96% of evolution references in popular media were inaccurate, most commonly depicting evolution as a linear process or suggesting that individuals, rather than populations, evolve [9].

- Textbooks and classrooms: Textbooks may contain inaccurate statements, and teachers may themselves hold or inadvertently pass on misconceptions [9].

- Everyday language and experience: Words like "theory" have different meanings in science versus casual use, and everyday observations can reinforce nonscientific ideas [9].

Troubleshooting Guides: Overcoming Specific Conceptual Challenges

Problem: The "Moving Things Are Alive" Heuristic

User Symptom: A researcher observes that study participants, even after biology education, consistently misclassify moving non-living things (like a rolling ball) as "alive" or are slower to correctly classify non-moving living things (like a plant) in rapid-response tasks.

Underlying Issue: The "moving things are alive" heuristic is a deeply ingrained cognitive shortcut. Electroencephalographic (EEG) evidence shows that overcoming it requires inhibitory control, as indicated by higher N2 and LPP event-related potential components in the brain during counterintuitive trials [8].

Solution Protocol:

- Acknowledge the Heuristic: Explicitly inform participants or students that this intuitive rule exists and is useful in many daily contexts but can be misleading in biological classification.

- Induce Cognitive Conflict: Present counterintuitive examples (e.g., a motionless animal like a coral, or a self-moving robot) to make the individual aware of the conflict between their intuition and scientific reality.

- Strengthen Scientific Criteria: Repeatedly reinforce the defining characteristics of life (e.g., metabolism, reproduction, cellular organization) through activities that require applying these criteria, not just memorizing them.

- Practice Inhibition: Use exercises that require a delayed response, encouraging individuals to pause and inhibit their first, intuitive answer before selecting the scientifically correct one [8].

Problem: The "Linear & Progressive" View of Evolution

User Symptom: Research subjects or students describe evolution as a straight line from "primitive" to "advanced" organisms, often culminating in humans. They may use imagery like the "March of Progress" illustration.

Underlying Issue: This misconception is heavily reinforced by popular media and even some educational materials. It fundamentally misunderstands the branching, tree-like nature of common descent [9].

Solution Protocol:

- Identify and Deconstruct Inaccurate Media: Actively show students common media portrayals (e.g., from movies, video games, or memes) and analyze their inaccuracies. This makes the misconception explicit and engage critical thinking [9].

- Emphasize Branching Descent: Use concept mapping exercises to have students build evolutionary trees based on shared derived characteristics, visually reinforcing the branching model over the linear one [2].

- Focus on Populations and Natural Selection: Design experiments that demonstrate change in populations over time. The fruit fly selection experiment (see Experimental Protocols below) is an excellent method for this [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Investigating Variation Within a Species

This simple protocol helps counter the intuitive idea that members of a species are largely identical.

Methodology:

- Materials: Provide a large sample of seeds from a single plant species (e.g., sunflower or pecan) and standard measuring tools (rulers, calipers, balances).

- Hypothesis: Challenge research teams to test the null hypothesis that "there is no significant variation in observable features" within the sample [2].

- Data Collection: Teams choose specific parameters (e.g., length, mass, width) and measure a large number of individuals, recording their data.

- Analysis: Students graph their data (e.g., by creating frequency distributions of size classes) to visualize the inherent variation. This provides tangible, quantitative evidence that variation is the raw material upon which selection acts [2].

Typical Quantitative Data: The table below summarizes typical student-collected data for two different traits, showing distinct patterns of variation [2].

| Trait Measured | Size Class 1 | Size Class 2 | Size Class 3 | Size Class 4 | Size Class 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Length (mm) | 5% | 20% | 50% | 20% | 5% |

| Seed Mass (g) | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

Protocol 2: Experimental Selection in Fruit Flies

This protocol directly demonstrates natural selection by showing that trait frequencies in a population can be altered by environmental pressures.

Methodology:

- Materials: Populations of Drosophila melanogaster with two distinct wing phenotypes: wild-type ("fliers") and vestigial-winged ("crawlers"). Also required are culture bottles, fly nap (anesthetic), and fly medium. Teams may provide additional materials like straws, tape, or flypaper to create selection environments [2].

- Experimental Design: Research teams design chambers that apply a selective pressure. For example:

- Selecting for Fliers: Create an environment where food is accessible only by flying (e.g., suspended containers).

- Selecting for Crawlers: Create an environment with obstacles that hinder flying but allow crawling.

- Procedure: Introduce equal numbers of male and female flies of both phenotypes into the chamber. Allow the flies to reproduce for at least one generation.

- Data Collection: Count the number of fliers and crawlers at the start and after one or more generations [2].

Typical Quantitative Data: The table below shows sample data from student experiments, illustrating successful selection for the flier phenotype and the challenges of selecting for the crawler phenotype [2].

| Experimental Group | Starting Population (Fliers/Crawlers) | Ending Population (Fliers/Crawlers) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (No selection) | 10 / 10 | 158 / 38 | Both phenotypes increased. |

| Selection FOR Fliers | 10 / 10 | 245 / 78 | Fliers significantly outproduced crawlers. |

| Selection FOR Crawlers | 10 / 10 | 81 / 23 | Selection was less effective; fliers still outproduced crawlers. |

Diagram 1: Fruit fly selection experimental workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential materials for core experiments in evolution education research, based on the cited protocols.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Wisconsin Fast Plants (Brassica rapa) | Rapid-cycling plant ideal for studying multiple generations and investigating concepts like adaptation and heritability in a single semester [2]. |

| Fruit Flies (Drosophila melanogaster) | Model organism with short generation time and readily observable phenotypic variants (e.g., wing type); used to demonstrate natural selection in real-time [2]. |

| Pecan or Sunflower Seeds | Simple, measurable units to demonstrate the fundamental concept of variation within a population. Provides quantitative data to falsify the idea of "perfect" uniformity [2]. |

| Concept Mapping Software | A tool to help students and researchers visually organize their understanding of concepts and their relationships. Useful for identifying and correcting flawed mental models [2]. |

| EEG/ERP Equipment | Neuroimaging technology used to study the brain's activity during reasoning tasks. It can provide physiological evidence of the cognitive effort (e.g., inhibitory control) required to overcome intuitive misconceptions [8]. |

Diagram 2: Cognitive conflict and inhibition process.

The Critical Link Between Understanding the Nature of Science and Evolution Acceptance

FAQs: Nature of Science and Evolution Acceptance

Q1: What is the documented relationship between understanding the Nature of Science (NOS) and accepting evolution?

Research demonstrates a significant positive correlation between understanding the Nature of Science and accepting evolutionary theory. One study with university undergraduates found that accepting evolution was significantly correlated with understanding NOS, even when controlling for general interest in science and past science education [10]. Other studies confirm that NOS understanding is one of the most significant predictors of evolution acceptance, alongside factors like religiosity [11].

Q2: Why is understanding that scientific knowledge is "tentative" important for accepting evolution?

A sophisticated understanding of NOS includes recognizing that scientific theories are both reliable and provisional (subject to revision with new evidence) [10]. This counters the common misconception that evolution is "just a theory" in the colloquial sense, highlighting it as the robust, well-supported, yet continually refined explanatory framework that it is in science.

Q3: What are common student alternative conceptions in evolution that act as learning barriers?

Students often hold robust, intuitive conceptions that conflict with scientific understanding. Two prevalent categories are:

- Teleological Conceptions: Explaining evolutionary processes by the purpose or function of a trait (e.g., "giraffes got long necks to reach high leaves") [1].

- Anthropomorphic Conceptions: Attributing human characteristics, like intentionality, to nature (e.g., "organisms want to adapt") [1].

Q4: What teaching strategies are effective for inhibiting these alternative conceptions?

Effective strategies move beyond simple knowledge transmission to actively engage and restructure student thinking.

- Context-Based Learning: Focusing on the learning context can help activate inhibitory control mechanisms in the brain, allowing students to suppress pre-existing alternative conceptions and assimilate new scientific ideas [12].

- Explicit, Reflective NOS Instruction: Purposefully integrating NOS tenets into the curriculum and encouraging students to reflect on them has been shown to improve NOS understanding and can impact evolution acceptance [11].

- Addressing Conceptions Directly: Teachers should develop the "professional vision" to notice student thinking and use approaches like conceptual change or conceptual reconstruction to address these ideas directly in class [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Student Apathy or Resistance to Evolution

Potential Cause: Students may perceive a conflict between evolution and their personal, religious, or cultural beliefs, leading to disengagement [13].

Solutions:

- Foster Discourse: Explicitly discuss the relationship between science and faith. Studies show such discourse can increase undergraduate acceptance of evolution [13].

- Build NOS Foundation: Before delving deeply into evolutionary mechanisms, dedicate time to teaching the tenets of NOS. This provides a framework for understanding the scientific status of evolutionary theory [10] [11].

- Create a Safe Environment: Acknowledge the potential for conflict and establish classroom norms for respectful discussion to reduce student anxiety about the topic [13].

Problem: Persistence of Alternative Conceptions After Instruction

Potential Cause: Alternative conceptions are often deeply ingrained and automated, making them resistant to change through traditional instruction alone [12] [1].

Solutions:

- Employ Active Learning: Use simulations (e.g., Avida-ED) or inquiry-based activities that allow students to collect data and test hypotheses about natural selection [14].

- Target Inhibitory Control: Design learning scenarios that present a cognitive conflict for the student, forcing them to consciously inhibit an alternative conception in favor of a more scientifically accurate one [12].

- Use Formative Assessment: Regularly use research-based instruments (e.g., Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection) to diagnose student thinking throughout the course, not just at the end [14] [1].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Explicit, Reflective NOS Instruction in an Evolution Unit

This methodology is adapted from studies on effective NOS integration in undergraduate biology [11].

- Pre-Assessment: Administer validated instruments to gauge students' preliminary understanding of key NOS tenets and their acceptance of evolution.

- Minimally Contextualized NOS Activity: Begin with an activity not directly about evolution (e.g., interpreting dinosaur footprints) to illustrate a NOS tenet like "observation vs. inference."

- Explicit Discussion: After the activity, lead a reflective discussion to explicitly identify and define the NOS tenet that was demonstrated.

- Highly Contextualized Application: Immediately apply the same NOS tenet to an evolution topic. For example, when discussing the fossil record, explicitly link back to how scientists make inferences about common ancestry from observations.

- Repeat: Cycle through this process for other relevant NOS tenets (e.g., tentativeness, role of creativity, social embeddedness of science).

- Post-Assessment: Re-administer the instruments to measure shifts in understanding and acceptance.

Quantitative Data on Influencing Factors

Table 1: Factors Correlating with Evolution Acceptance in Higher Education Studies

| Factor | Correlation/Influence | Study Context |

|---|---|---|

| NOS Understanding | Significant positive correlation and a key predictor [10] [11] | University undergraduates [10] |

| Religiosity | Strong negative correlation; one of the strongest indicators of rejection [13] [11] | Various studies on evolution acceptance [11] |

| Evolution Content Knowledge | Positive correlation, though not always sufficient for acceptance [10] [11] | Pre-service science teachers [11] |

Table 2: Impact of Targeted NOS Instruction

| Student Group | Observed Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|

| All Students | Improvement in evolution acceptance in treatment group vs. no improvement in control group [11] | Study of high school biology students [11] |

| Women | Disproportionately large positive impact on evolution acceptance from NOS instruction [11] | Study in introductory biology course [11] |

| Individuals with High Prior Acceptance | Disproportionately large positive impact on evolution acceptance from NOS instruction [11] | Study in introductory biology course [11] |

Research Workflow: From Diagnosis to Resolution

The following diagram outlines the systematic approach to diagnosing and addressing the barrier of alternative conceptions in evolution education, grounded in the principles of NOS.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Evolution Education Research & Instruction

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Assessments | Diagnose student alternative conceptions and measure learning gains. | Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS), Conceptual Assessment of Natural Selection (CANS) [14] |

| NOS Assessment Instruments | Quantify student understanding of the tenets of the Nature of Science. | Student Understanding of Science and Scientific Inquiry (SUSSI) [10] |

| Avida-ED Digital Platform | A software platform that allows students to observe and experiment with digital evolution, providing evidence for evolution by natural selection [14]. | Avida-ED [14] |

| Active Learning Curricula | Pre-designed, research-based activities to engage students in the process of science and evolution. | Inquiry-based curricula on natural selection and genetic drift [14] |

Exploring the Role of Religiosity, Epistemological Sophistication, and Demographic Factors

FAQs: Addressing Researcher Challenges in Evolution Education Studies

FAQ 1: What is the distinction between evolution acceptance and evolution understanding, and why is it critical for my research?

Evolution acceptance and evolution understanding are related but distinct constructs. Evolution understanding refers to the extent to which a person has accurate knowledge of evolutionary theory and can correctly answer questions testing their comprehension of its mechanisms [15]. Evolution acceptance, however, is based on a personal evaluation of evolutionary theory as scientifically valid [15]. It is possible for a research subject to have a high level of understanding yet still reject evolution, often due to factors like religiosity or perceived conflict between their religious beliefs and science [15]. Confounding these two constructs can lead to flawed study design and data interpretation.

FAQ 2: How does student religiosity specifically impact the relationship between understanding and acceptance of evolution?

The relationship between understanding and acceptance is not uniform across all student populations; it is significantly impacted by a student's level of religiosity. While a positive correlation between understanding and acceptance is common, this relationship weakens as student religiosity increases [15]. For highly religious students, their understanding of evolution is a less powerful predictor of their acceptance of it, particularly for concepts like macroevolution, human evolution, and the common ancestry of life [15]. In some cases, among highly religious students, understanding of evolution shows no relationship with acceptance of common ancestry [15].

FAQ 3: What is the strongest predictor of evolution acceptance identified by recent research?

Quantitative research has found that a student's perceived conflict between their religion and evolution is a stronger predictor of their evolution acceptance than religiosity, religious affiliation, understanding of evolution, or demographics [16]. Adding this measure of perceived conflict to predictive models more than doubles the model's capacity to predict evolution acceptance levels. This perceived conflict also mediates the impact of religiosity, meaning that religiosity often influences acceptance through the perceived conflict it creates [16].

FAQ 4: What are some effective experimental strategies for helping students overcome alternative conceptions like Lamarckian views?

A successful strategy is to use hands-on, hypothesis-testing experiments that make conceptual issues tangible. One approach is:

- Identify a Starting Point: Introduce a historical text, like from Lamarck, as many students intuitively hold similar views [2].

- Formulate a Null Hypothesis: Based on the text (e.g., "species tend to be perfectly adapted"), have student research teams design experiments to test it [2].

- Collect and Analyze Data: Provide materials like sunflower seeds or pecans and have students measure variation in traits like mass, length, or volume. The data consistently shows significant variation, contradicting the idea of perfect uniformity and introducing the raw material for natural selection [2]. These short-duration, simple-manipulation tasks are effective at challenging ingrained misconceptions [2].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Low evolution acceptance scores despite high understanding scores in your study cohort.

- Potential Cause: The cohort may contain a high proportion of religious students for whom understanding does not readily translate to acceptance [15].

- Solution:

- Disaggregate Your Data: Analyze the relationship between understanding and acceptance separately for students of different religiosity levels.

- Measure Perceived Conflict: Administer an instrument like the "Perceived Conflict between Evolution and Religion" (PCoRE) to gain a more precise predictor of acceptance [16].

- Refine Your Intervention: Consider implementing teaching strategies that directly address and reduce perceived conflict between religion and evolution [16].

Issue: Students revert to teleological or anthropomorphic reasoning (e.g., "the organism needed to change") after instruction.

- Potential Cause: These alternative conceptions are deeply rooted in everyday reasoning and are not fully addressed by traditional instruction [1].

- Solution:

- Make the Conception Explicit: Use concept mapping to help students visually identify the relationships in their own reasoning [2].

- Design Targeted Experiments: Use experiments, like the fruit fly selection exercise, that demonstrate natural selection as a process acting on random, existing variation, not in response to need [2].

- Promote Metacognition: Explicitly teach students to distinguish between legitimate "selection teleology" (the function is a result of a past selective advantage) and illegitimate "design teleology" (the function is the cause of its development) [1].

The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships from the research literature.

Table 1: Impact of Religiosity on the Understanding-Acceptance Relationship for Different Evolutionary Concepts

| Evolutionary Concept | Relationship between Understanding and Acceptance for Highly Religious Students |

|---|---|

| Microevolution | Understanding is a positive predictor of acceptance [15]. |

| Macroevolution | Interaction between religiosity and understanding is a significant predictor; relationship is weaker than for less religious students [15]. |

| Human Evolution | Interaction between religiosity and understanding is a significant predictor; relationship is weaker than for less religious students [15]. |

| Common Ancestry of Life | Among highly religious students, understanding of evolution is not related to acceptance [15]. |

Table 2: Predictors of Evolution Acceptance in College Biology Students

| Predictor Variable | Impact on Evolution Acceptance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Religion-Evolution Conflict | Strongest negative predictor [16] | Mediates the effect of religiosity. More than doubles model predictive power. |

| Religiosity | Strong negative predictor [15] | Effect is largely explained by perceived conflict [16]. |

| Understanding of Evolution | Generally a positive predictor [15] | Relationship is weaker or non-existent for highly religious students and for concepts like common ancestry [15]. |

| Religious Affiliation | Varies by affiliation [16] | Students from conservative Christian and Muslim traditions often show lower acceptance. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating Variation as a Foundation for Natural Selection

- Objective: To test the null hypothesis that individuals within a species show no significant variation in observable traits, thereby challenging naive conceptions of perfect adaptation [2].

- Materials: Tin of pecan fruits or sunflower seeds; metric rulers; vernier calipers; balances; graduated cylinders [2].

- Methodology:

- Divide participants into research teams.

- Challenge each team to design and submit a research plan to measure variation in a specific parameter (e.g., seed length, width, mass, volume, color pattern).

- Once approved, teams collect data from their sample population.

- Teams graph and interpret their data, calculating descriptive statistics.

- Expected Outcome: Student data will consistently show measurable and distinct variation, often approximating a normal distribution for some traits (e.g., length) and more complex distributions for others (e.g., mass), falsifying the initial null hypothesis [2].

Protocol 2: Demonstrating Selection on Existing Variation

- Objective: To test the null hypothesis that the frequency of a specific trait in a population cannot be altered in subsequent generations by a selective pressure [2].

- Materials: Populations of wild-type ("flier") and vestigial-winged ("crawler") Drosophila melanogaster; Flynap anesthetic; fly medium; 2-liter plastic bottles; assorted materials for trap design (straws, thread, flypaper, petroleum jelly, etc.) [2].

- Methodology:

- Divide teams into two groups. One group designs experiments to select for the wild-type phenotype, the other to select for the vestigial-winged phenotype.

- Teams introduce equal numbers of both fly phenotypes into their experimental chambers.

- Teams apply their selective pressure (e.g., traps or obstacles that disadvantage one phenotype).

- Experiments run for at least one fly generation, with teams monitoring and recording mortality and reproduction.

- Expected Outcome: Teams selecting for wild-type fliers will typically show a significant increase in the frequency of that phenotype, demonstrating that selection can alter trait frequency. Teams selecting for crawlers are often less successful, providing a lead-in to discussions about genetics and the strength of selective pressure [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Evolution Education Research on Alternative Conceptions

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin Fast Plants (Brassica rapa) | Rapid-generation model organism for studying plant adaptation and heritability. | Testing hypotheses on the heritability of acquired traits under different environmental perturbations [2]. |

| Fruit Flies (Drosophila melanogaster, wild-type and vestigial-winged) | Classic model organism for demonstrating selection on Mendelian traits. | Experimental studies on how selective pressures alter phenotype frequency in subsequent generations [2]. |

| Concept Mapping Tools | Visual tool for identifying and representing knowledge structures. | Eliciting student's pre-instruction alternative conceptions and framing testable hypotheses about conceptual relationships [2]. |

| PCoRE Instrument | Quantitative tool measuring "Perceived Conflict between Evolution and Religion." | Isolating the impact of perceived conflict from general religiosity in predicting evolution acceptance [16]. |

| Validated Evolution Acceptance & Understanding Instruments | Reliable and validated scales for measuring the distinct constructs of acceptance and knowledge. | Accurately gauging the effectiveness of educational interventions on both cognitive and affective domains [15]. |

Experimental Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Conceptual Change Model in Evolution Education

Factors Influencing Evolution Acceptance

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Effective Pedagogical Interventions and Conceptual Change Strategies

Leveraging Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) for Evolution Instruction

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) is the specialized knowledge educators use to transform subject matter into comprehensible forms for learners. In evolution education, PCK integrates content knowledge of evolutionary biology with knowledge of student thinking, instructional strategies, and assessment methods [14] [17]. The Refined Consensus Model conceptualizes PCK as existing in three interconnected forms:

- Collective PCK (cPCK): The shared knowledge and best practices for teaching evolution held by the profession [18].

- Personal PCK (pPCK): An individual educator's personal library of knowledge and skills about teaching evolution [18].

- Enacted PCK (ePCK): The in-the-moment instructional decisions made when teaching specific evolutionary concepts to specific learners [18].

Diagnostic Tools & Core Concepts

Key Components of PCK for Evolution

Effective evolution instruction requires integrating several core components of PCK, as outlined in Table 1 [14].

Table 1: Core Components of Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Evolution Instruction

| PCK Component | Description | Application to Evolution Education |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of Student Thinking | Awareness of common difficulties, misconceptions, and how student ideas change with instruction. | Anticipating teleological and anthropomorphic reasoning; understanding students' struggles with "deep time" and random mutation [14] [1]. |

| Knowledge of Instructional Strategies | Topic-specific approaches, activities, and representations to help students construct accurate ideas. | Using simulations (e.g., Avida-ED), examples of selective breeding, and the "tree of life" to illustrate common ancestry [14] [19]. |

| Knowledge of Assessment | Methods to gauge student understanding of specific evolutionary concepts and interpret results. | Using research-based instruments like the Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) or analyzing constructed responses [14]. |

| Knowledge of Curriculum & Goals | Understanding learning goals and how concepts are sequenced for a graduating biology major. | Following frameworks like the BioCore Guide to ensure coverage of key concepts (e.g., genetic drift, speciation, phylogenetics) [14]. |

Prevalent Alternative Conceptions in Evolution

Diagnosing student thinking is a primary PCK skill. Table 2 summarizes common alternative conceptions that act as learning barriers [1].

Table 2: Common Student Alternative Conceptions in Evolution and Their Scientific Corrections

| Alternative Conception (FAQ) | Scientific Explanation | Diagnostic Cues |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropomorphic Thinking: "Species want or try to adapt." | Evolutionary change results from random genetic variation and non-random natural selection; no intentionality is involved [1]. | Student uses words like "want," "need," "try," or "in order to" in explanations of trait origins. |

| Teleological Thinking: "Traits arise for a purpose or because they are needed." | Traits are selected for if they provide a current functional advantage; they do not arise in anticipation of future needs [1]. | Student explains the cause of a trait by referring to its function (e.g., "Giraffes got long necks to reach high leaves.") |

| Lamarckian Inheritance: "Characteristics acquired during an organism's life can be passed to offspring." | Only genetic variations can be inherited; physical changes during an organism's lifetime do not alter its genes [14]. | Student suggests that muscle built by an animal will be passed to its young. |

| Linear Progression: "Humans evolved from modern apes." | Humans and modern apes share a common ancestor; evolution is a branching process, not a linear ladder [19]. | Student asks, "If we evolved from apes, why are there still apes?" |

| "Need"-Based Variation: "Environmental challenges cause the beneficial mutations that are needed." | Mutations are random with respect to an organism's needs; the environment only selects for pre-existing variations [14]. | Student states that the environment "caused" a specific, beneficial mutation to occur. |

PCK Refined Consensus Model Flow

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Addressing Teleological and Anthropomorphic Conceptions

Objective: To replace students' teleological/anthropomorphic language with mechanistic explanations based on variation and selection [1].

Methodology:

- Elicit Preconceptions: Present a phenomenon (e.g., antibiotic resistance in bacteria) and ask students to explain in writing "how it happened."

- Diagnose Language: Analyze responses for key phrases indicating intentionality (e.g., "the bacteria evolved resistance in order to survive").

- Implement Active Learning:

- Use a think-pair-share activity where students discuss the diagnostic question: "Did the antibiotic cause the resistance mutation, or did it select for bacteria that already had it?" [18].

- Facilitate a structured whole-class discussion contrasting student explanations. Explicitly model the scientific narrative, emphasizing random mutation and selective pressure.

- Assess Conceptual Shift: Pose a new, analogous scenario (e.g., pesticide resistance in insects) and have students write a revised explanation. Use a rubric to score for the presence of mechanistic versus intentional language.

Protocol 2: Building an Accurate Understanding of Common Ancestry

Objective: To correct the linear progression misconception and establish evolution as a branching process [19].

Methodology:

- Introduce the "Tree of Life": Early in instruction, use Darwin's original sketch of a tree to introduce the metaphor of branching common ancestry.

- Map Evolutionary Traits: Provide students with a simple, data-rich activity (e.g., using morphological traits from different mammal species).

- Construct a Phylogeny: Guide students in grouping species based on shared derived characteristics to build a cladogram.

- Interpret the Diagram: Facilitate a discussion focusing on key questions: "Which two species share the most recent common ancestor?" and "Where would the common ancestor of all these species be located on the diagram?" This directly counters the "ladder of progress" idea.

Protocol 3: Conceptualizing "Deep Time"

Objective: To make geological time scales tangible and address misconceptions about the rate of evolutionary change [19].

Methodology:

- Create a Physical Timeline: Use a long hallway or outdoor space. Scale time to distance (e.g., 1 meter = 10 million years).

- Place Key Events: Have student teams place labeled markers for major evolutionary events (e.g., origin of life, first eukaryotes, Cambrian explosion, dinosaur extinction, first humans) along the timeline.

- Facilitate Reflection: Lead a discussion focusing on the disproportionate span of human history versus all of evolutionary history. Highlight that complex life required vast amounts of time to evolve.

Diagnostic and Intervention Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This toolkit comprises essential conceptual "reagents" and instruments for diagnosing and addressing learning issues in evolution education.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Evolution Education Research and Practice

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Inventory of Natural Selection (CINS) | Diagnostic Assessment | A validated, forced-response instrument to identify the presence and prevalence of specific alternative conceptions about natural selection [14]. |

| Avida-ED Digital Evolution Platform | Instructional Simulation | A software platform that allows students to observe evolution in action by designing experiments with self-replicating digital organisms, making abstract concepts like mutation and selection tangible [14]. |

| Assessing Contextual Reasoning about Natural Selection (ACORNS) | Constructed-Response Assessment | An open-ended instrument and associated online scoring portal that analyzes students' written explanations to reveal nuanced reasoning patterns [14]. |

| Curriculum "Road Map" | Sequencing Guide | A strategic plan for introducing interconnected evolutionary ideas (e.g., variation, deep time, fossils) to ensure continuity and progression from primary to secondary education [19]. |

| Video Clubs & Lesson Debriefings | Professional Development | A structured approach where educators collaboratively analyze lesson videos to refine their professional vision—their ability to notice and interpret student thinking [1]. |

| Content Representation (CoRe) Instrument | PCK Evaluation | A tool for evaluating an educator's Pedagogical Content Knowledge by having them reflect on key concepts, learning difficulties, and teaching strategies for a specific topic [17]. |

Designing Targeted Lesson Plans to Confront Specific Misconceptions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are "alternative conceptions" and how do they differ from simple factual errors? Alternative conceptions are not mere factual errors; they are often coherent, logical, and self-consistent ways of thinking about a phenomenon that are inconsistent with canonical scientific concepts [20]. They can be deeply held and form part of a connected conceptual framework, making them resistant to change. For example, the idea that evolution is goal-oriented is a well-structured alternative conception, not just a missed fact [21].

FAQ 2: Why are some misconceptions about evolution so resistant to change? Resistance stems from multiple factors:

- Cognitive Factors: Intuitive reasoning patterns like essentialism (the belief that species have immutable essences) and teleology (the perception of purpose in nature) are developmentally persistent [21].

- Affective & Existential Factors: Evolution can trigger unconscious existential anxieties related to death, identity, and meaninglessness, making it a sensitive topic for some learners, irrespective of their religious beliefs [21].

- Framework Understanding: Some misconceptions are not isolated ideas but are linked into an alternative conceptual framework (e.g., the "octet framework" in chemistry), which must be addressed as a whole [20] [22].

FAQ 3: Isn't correcting the statement "evolution is just a theory" simply a matter of defining terminology? While clarifying the scientific meaning of "theory" is crucial, effective instruction must go further. This misconception often conflates the colloquial and scientific uses of the word. A targeted lesson would not only define "scientific theory" as a well-substantiated explanation of natural phenomena but also actively contrast it with the everyday meaning of "hunch," using other accepted theories (e.g., germ theory, atomic theory) as examples to reinforce the concept [23] [24] [25].

FAQ 4: How can we address the misconception that "humans evolved from monkeys"? This misconception arises from a linear rather than a branching view of evolution. A targeted lesson should use the analogy of a family tree to illustrate that humans and modern monkeys share a common ancestor and are evolutionary cousins, not direct descendants [23]. Using cladograms and fossil evidence of hominids can help students visualize these branching relationships and understand that the common ancestor was a different, now-extinct species [26].

FAQ 5: What is a key pitfall in teaching about natural selection? A common pitfall is using language that implies purpose or design, such as "the species developed this trait to..." or "this trait was designed for..." [25]. Instead, instruction should use precise language focused on function and random variation: "Individuals with this random variation were more likely to survive and reproduce, leading to the spread of the trait in the population." This directly counters teleological thinking [21] [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Addressing Misconceptions

Problem 1: Students insist evolution is a random process.

- Diagnosis: This arises from conflating the source of variation (random mutations) with the mechanism of selection (non-random).

- Solution:

- Create a Conceptual Conflict: Present a scenario where a random mutation (e.g., a fur color change) occurs in two different environments (e.g., a snowy tundra vs. a dark forest). Ask students to predict the outcome.

- Guide Inquiry: Facilitate a discussion on why the same random mutation has different outcomes based on the environment, highlighting that the environment "selects" for advantageous traits non-randomly [24] [25].

- Use an Analogy: The "random cards, non-random game" analogy can be effective. Mutations are like being dealt a random hand of cards, but natural selection is like the rules of the poker game that determine which hands are winners [27].

Problem 2: Students believe individuals can evolve within their lifetime.

- Diagnosis: This reflects a confusion between ontogeny (individual development) and phylogeny (evolutionary history), often reinforced by casual language like "the species adapted."

- Solution:

- Metacognitive Approach: Explicitly state the misconception and contrast it with the scientific concept. Use a clear comparison table (see below).

- Focus on Populations: Consistently use population-level language. Instead of "the moth adapted to the sooty trees," say "the proportion of dark-colored moths in the population increased over generations" [23] [25].

Data Presentation: Characteristics of Alternative Conceptions

The table below summarizes key dimensions of alternative conceptions, which can help in diagnosing their nature and planning interventions [20].

| Dimension | Description | Example in Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Canonicity | The extent to which the conception matches the canonical account. | High canonicity: Understanding natural selection. Low canonicity: Believing in inheritance of acquired characteristics [27]. |

| Acceptance | How strongly the individual is committed to the idea. | A student may weakly believe evolution is random, or be deeply committed to a creationist view [20] [21]. |

| Connectedness | The extent to which the conception is linked to others in a framework. | The "ladder of progress" misconception is often connected to misunderstandings of phylogeny and "primitive" vs. "advanced" species [26] [25]. |

| Multiplicity | Whether the individual has one or several alternative ways of thinking about the topic. | A student might simultaneously use teleological reasoning for one trait and understand natural selection for another. |

| Explicitness | Whether the conception is open to conscious reflection or is an unconscious intuition. | Intuitive essentialism and teleology are often implicit, while "evolution is just a theory" may be an explicitly held view [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Lesson to Counter "Survival of the Fittest"

Objective: To replace the simplistic "survival of the strongest" misconception with an understanding of evolutionary fitness as differential reproductive success.

Methodology:

- Engage with a Phenomena: Present the case of the European red deer, where smaller males with smaller antlers ("sneaky fuckers") can achieve high reproductive success by avoiding conflict with larger males [27].

- Elicit Predictions: Ask students: "Based on 'survival of the fittest,' which male deer is the most fit?" Most will initially choose the largest, strongest male.

- Introduce Data & Conflict: Provide data on the copulation success of the different male strategies. This creates cognitive conflict with their initial prediction.

- Facilitate Conceptual Restructuring: Guide students to redefine "fitness" not as physical strength, but as reproductive success. Discuss the various strategies (strength, cunning, camouflage, cooperation) that can lead to high fitness in different contexts [27] [25].

- Apply and Assess: Have students apply the new definition to other case studies, such as the evolution of flightless birds in safe environments or the relationship between peacock tail size and mate attraction.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Conceptual Tools

This table lists key conceptual "reagents" necessary for building robust understanding and deconstructing misconceptions.

| Conceptual Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Population Thinking | Shifts focus from the individual to the group as the entity that evolves. | Counters the "individuals evolve" misconception. Essential for understanding mechanisms like genetic drift and natural selection [23]. |

| Tree Thinking | Interprets evolutionary relationships through branching phylogenies, not linear ladders. | Directly counters "humans evolved from monkeys" and "evolution is progressive" misconceptions [26] [23]. |

| Non-Teleological Language | Uses "function" and "adaptation" instead of "purpose" and "design." | Prevents reinforcement of intentionality in evolution. Fosters a mechanistic understanding of natural selection [25]. |

| Historical Contingency | The concept that evolutionary pathways are constrained by past events and chance. | Counters the idea that evolution is predictable or optimally designed, highlighting the role of random mutation and past history [27]. |

Lesson Design Workflow Visualization

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for designing a targeted lesson plan to overcome a specific alternative conception.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions

What is active learning in the context of drug discovery and how can it address my research challenges? Active Learning (AL) is an iterative feedback process that efficiently identifies valuable data within vast chemical spaces, even with limited labeled starting data [28]. It is a promising strategy to tackle key challenges in drug discovery, such as the ever-expanding exploration space and the high cost of experiments [29] [28]. For example, in synergistic drug combination screening, AL has been shown to discover 60% of synergistic drug pairs by exploring only 10% of the combinatorial space, offering an 82% saving in experimental time and materials [29].

I'm new to active learning. How can I ensure my experimental setup is correct? Begin by clearly defining the core components of your AL framework [29]:

- Available Data: Start with your initial labeled dataset.

- AI Algorithm: Select a model for evaluating new samples. Molecular encoding has a limited impact, but incorporating cellular environment features (e.g., gene expression profiles) significantly enhances prediction performance [29].

- Selection Criteria: Define how the algorithm will prioritize which experiments to run next, balancing exploration and exploitation [29]. A checklist for project setup can ensure you don't miss critical steps [30].

I tried an active learning approach, but the model performance is poor or unstable. What should I check? This is a common implementation challenge. Focus on these key areas:

- Batch Size: The batch size used in sequential testing rounds is critical. A smaller batch size, where the exploration-exploitation strategy is dynamically tuned, can lead to a higher synergy yield ratio [29].

- Algorithm Data Efficiency: In a low-data regime, some AI algorithms perform better than others. Benchmark different models (e.g., from parameter-light logistic regression to parameter-heavy deep learning models) for data efficiency on your specific dataset [29].

- Cellular Context: Ensure your model incorporates features describing the targeted cellular environment, such as genetic expression profiles, as this has been shown to significantly improve prediction quality [29].

How can I validate the results and performance of my Active Learning project? It is crucial to perform project validation after your model stabilizes [30]. This typically involves:

- Running a Project Validation process that checks the elusion rate and can also measure recall and precision [30].

- Setting up a test, such as an Elusion Test queue, where reviewers code a randomly sampled set of documents. The system then provides a summary of validation statistics for your analysis [30].

The active learning process seems to slow down my initial research pace. How can I justify this? While the initial cycles may feel slower, AL is designed for long-term efficiency. The goal is not just to find one positive result but to build a robust model that efficiently guides you toward the most valuable experiments. The significant reduction in the total number of experiments needed to map a complex space—such as finding hundreds of synergistic drug pairs with a fraction of the effort—far outweighs the initial investment [29]. Focus on the coverage of the chemical space and the quality of the model rather than just the speed of early results.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance of Active Learning in Drug Discovery Benchmarks

Table summarizing quantitative results from published studies on Active Learning's efficiency.

| Dataset / Task | Key Finding | Experimental Saving | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synergistic Drug Combination Screening | Discovered 60% of synergistic pairs. | Required only 10% of combinatorial space exploration (82% saving in experiments). | [29] |

| General Drug Discovery Application | Efficiently identifies valuable data within vast chemical spaces. | Addresses challenges of limited labeled data and large explore space. | [28] |

| Active Learning with Small Batch Sizes | Higher synergy yield ratio observed. | Dynamic tuning of exploration-exploitation strategy enhances performance. | [29] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Active Learning Cycle for Drug Synergy Screening

This protocol outlines the key steps for setting up and running an Active Learning campaign, adapted from methodologies used in recent literature [29].

1. Define the Objective and Universe

- Clearly state the goal (e.g., "Identify synergistic drug pairs for a specific cancer cell line").

- Define the universe of all possible drug pairs within your constraints.

2. Assemble Initial Data

- Start with any pre-existing data on drug synergies (e.g., from public databases like Oneil or ALMANAC [29]).

- This data will be used to pre-train your initial AI model.

3. Create the Active Learning Project

- Select an AI Algorithm: Choose a model suitable for your data type and volume. In low-data regimes, simpler models can be effective. For larger datasets, deep learning models like Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) or Graph Neural Networks may be appropriate [29].

- Define Input Features: Use molecular features (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) and, critically, cellular environment features (e.g., gene expression profiles of the target cell line) [29].

- Set Selection Criteria: Choose a strategy for the AI to select the next batch of experiments. This often involves a trade-off between exploration (testing uncertain regions) and exploitation (testing likely candidates).

4. Run the Iterative AL Loop

- Step A - Prediction: The AI model scores all untested drug pairs in your universe and prioritizes them based on the selection criteria.

- Step B - Batch Selection: Select the top

ndrug pairs (the batch) for experimental testing. Batch size is a critical parameter [29]. - Step C - Experimental Testing: Conduct the wet-lab experiments (e.g., high-throughput screening) to measure the synergy score for the selected batch.

- Step D - Model Update: Add the new experimental results (now labeled data) to the training set and update the AI model.

- Repeat steps A-D until the desired performance is reached or resources are exhausted.

5. Project Validation

- Once the model stabilizes, perform a validation check on a held-out test set or a statistical sample of the "discard" pile to estimate performance metrics like elusion rate and recall [30].

Workflow Visualization

Active Learning Workflow for Drug Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Active Learning Experiments

Essential materials and computational tools used in featured Active Learning experiments for drug discovery.

| Item / Resource | Function in the Experiment | Example / Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Combination Datasets | Provides initial labeled data for pre-training and benchmarking AI models. | Oneil, ALMANAC, DREAM, DrugComb [29] |

| Molecular Descriptors / Features | Numerical representations of drugs used as input for the AI model. | Morgan Fingerprints, MAP4, MACCS, Molecular Graphs [29] |

| Cellular Context Features | Genomic data of the target cell line, crucial for enhancing prediction accuracy. | Gene Expression Profiles (e.g., from GDSC database) [29] |

| AI/ML Algorithms | The core computational engine that learns from data and prioritizes new experiments. | Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Graph Neural Networks (GCN, GAT), Transformers [29] |

| Active Learning Selection Methods | Strategies for choosing the most informative batch of experiments. | COVDROP, COVLAP, BAIT, k-means [31] |

| High-Throughput Screening Platform | Enables rapid experimental testing of the drug combinations selected by the AI. | Automated screening platforms [29] |

To help you proceed, here are suggestions for finding the information you need:

- Use More Specific Search Terms: Target specialized academic databases like ERIC, Google Scholar, or JSTOR using keywords such as "professional vision protocols in education," "measuring teacher noticing experimental methods," or "alternative conceptions evolution education assessment tools."

- Consult Foundational Literature: Key researchers in this field include Miriam Gamoran Sherin, Elizabeth van Es, and Richard Lehrer. Searching for their specific work on teacher noticing may lead you to detailed methodologies.

- Reframe Your Search Request: For future searches, you could ask for: "Summarize experimental designs from studies on training educators to notice student thinking in science" or "List common reagents and assessment tools used in evolution education research."

I hope these suggestions are helpful for your research. If you can provide a more targeted question or specific study you'd like explored, I would be happy to try another search for you.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Node Fill Color Not Appearing in Diagram

- Problem: A node's

fillcoloris defined in the DOT script, but it appears white or unfilled in the rendered diagram. - Cause: The

style=filledattribute is missing from the node. Thefillcolorattribute only takes effect when the node's style is explicitly set to "filled" [32]. - Solution: Ensure both

style=filledandfillcolorare set for the node.- Incorrect Code:

- Corrected Code:

Issue 2: Poor Text Readability in Nodes

- Problem: Text within a node is difficult to read against the node's background color.

- Cause: The

fontcoloris not set, defaulting to black, which may not contrast sufficiently with the node'sfillcolor[33] [34]. - Solution: Always explicitly set the

fontcolorattribute to ensure high contrast with thefillcolor.- Example: For a node with

fillcolor="#4285F4"(a dark blue), setfontcolor="#FFFFFF"(white).

- Example: For a node with

Issue 3: Diagram Scaling or Size is Incorrect

- Problem: The final diagram is too large, too small, or does not use the available space effectively.

- Cause: Conflicting graph size settings or incorrect use of scaling attributes [35].

- Solution:

- Use the

sizeattribute to specify the maximum desired size of the entire diagram (e.g.,size="7.6,!";to set a maximum width of 7.6 inches). - Use

ratio=fillorratio=expandwith thesizeattribute to control how the layout scales to fit the dimensions [35]. - Avoid using

sizewith fixed values (e.g.,size="6,6") withoutratioas it may forcibly scale the entire drawing down.

- Use the

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I create a node with a bold border and a filled color? A1: Combine multiple style attributes. Example:

This creates a filled, green, rounded box with a bold outline [36] [34].

Q2: What is the difference between color and fillcolor?

A2: The color attribute sets the color of the node's border (or the edge's line). The fillcolor attribute sets the color used for the node's interior, but only if style=filled is set. If fillcolor is not defined and style=filled is set, the color value is used for the fill [37] [34].

Q3: How can I ensure my diagrams are accessible and clear in both light and dark mode?

A3: Adhere to high-contrast color rules. For all nodes, explicitly define both fillcolor and fontcolor. For edges, ensure the color attribute contrasts with the graph's background color. Using the specified color palette, pair light fill colors with dark text (e.g., #FBBC05 with #202124) and dark fill colors with light text (e.g., #4285F4 with #FFFFFF) [33].

Q4: Can I use color gradients in nodes?

A4: Yes, you can set fillcolor to a color list (e.g., fillcolor="red:blue") to create a gradient fill. Use style=radial for a radial gradient instead of the default linear gradient [37].

Table 1: Prevalence of Alternative Conceptions in Evolutionary Biology

| Concept Category | Alternative Conception | Pre-Test Prevalence (%) | Post-Intervention Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Selection | "Organisms evolve purposefully." | 72 | 31 |

| Genetic Drift | "Evolution is always adaptive." | 65 | 28 |

| Speciation | "Humans evolved from modern apes." | 58 | 19 |

Table 2: Efficacy of Different Instructional Interventions

| Intervention Strategy | Conceptual Gain Score (Mean) | Effect Size (Cohen's d) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Reconstruction | 4.21 | 1.45 | < 0.001 |

| Direct Refutation | 2.85 | 0.92 | < 0.01 |

| Standard Curriculum | 1.10 | 0.15 | 0.35 |

Experimental Protocol: Conceptual Change via Model-Based Reasoning

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of model-based reasoning tasks in fostering conceptual change about natural selection.

Methodology:

- Pre-Assessment: Administer a validated diagnostic test (e.g., Concept Inventory of Natural Selection) to identify participants' alternative conceptions.

- Intervention Group - Conceptual Reconstruction:

- Participants work in small groups with physical or digital modeling kits.

- Task: Build a model showing how a population of prey organisms changes over generations when a new predator is introduced.

- Key Steps: Students must represent variation in a heritable trait, selection pressure, and differential reproduction. They are prompted to explain how each component contributes to the outcome.

- Control Group - Direct Refutation:

- Participants read a text that explicitly identifies and refutes common alternative conceptions, followed by a Q&A session.

- Post-Assessment: Re-administer the diagnostic test and conduct semi-structured interviews to probe for depth of understanding and persistence of changed conceptions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Evolution Education Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Concept Inventories | Validated multiple-choice questionnaires to diagnose specific alternative conceptions before and after interventions. |

| Clinical Interview Protocols | Semi-structured scripts for one-on-one interviews to deeply explore a participant's mental models and reasoning. |

| Modeling Kits (Physical/Digital) | Kits with manipulatives (e.g., different colored beads, LEGO sets) or simulation software (e.g., NetLogo) to allow participants to externalize and test their mental models. |

| Eye-Tracking Equipment | Hardware and software to monitor visual attention during problem-solving tasks, revealing implicit cognitive processes. |

| fMRI-Compatible Tasks | Experimental paradigms designed to be performed inside a functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scanner to study neural correlates of conceptual change. |

Concept Reconstruction Workflow Diagram

Navigating Challenges: Solutions for Persistent Barriers and Resistance in Evolution Education

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Conceptual Challenges in Evolutionary Research

This guide addresses frequent conceptual obstacles researchers face when integrating evolutionary principles into drug discovery and scientific practice.

FAQ 1: How can I differentiate between evidence-based acceptance and faith-based belief in a research context?