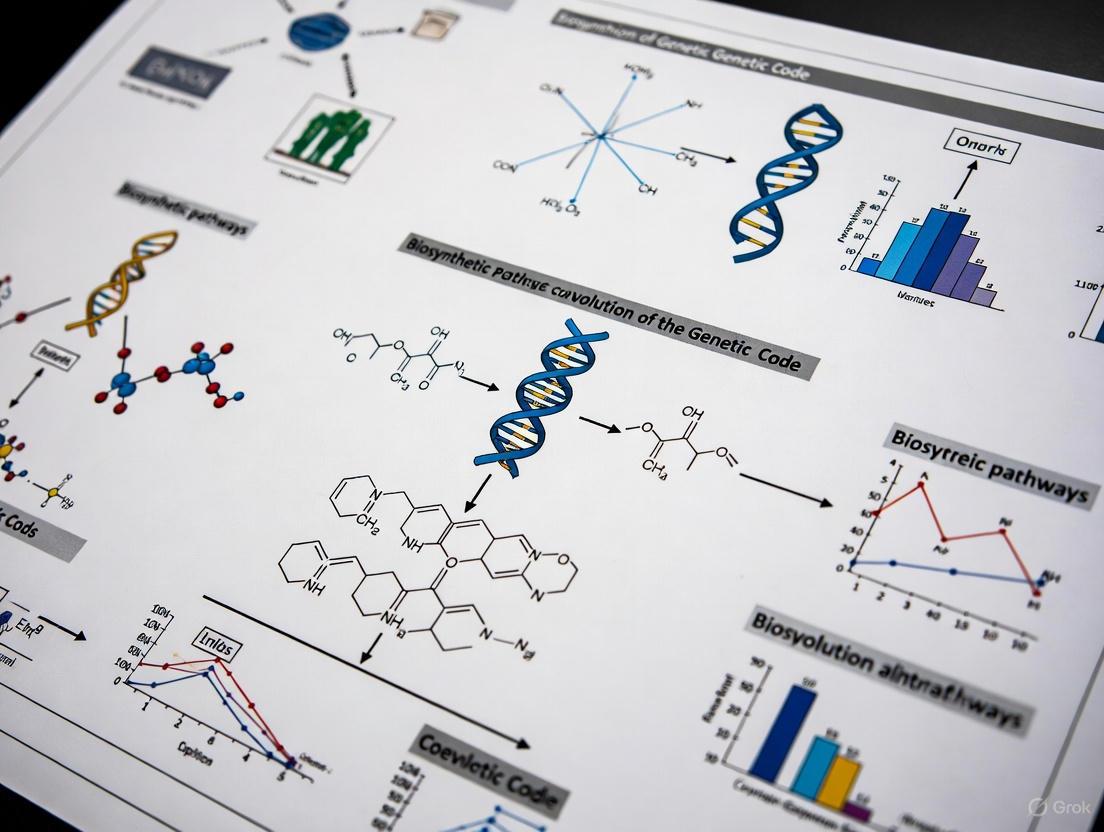

Coevolution of the Genetic Code and Biosynthetic Pathways: From Primordial Origins to Synthetic Biology Applications

This article explores the coevolution theory of the genetic code, which posits that the code's structure is an evolutionary imprint of biosynthetic relationships between amino acids.

Coevolution of the Genetic Code and Biosynthetic Pathways: From Primordial Origins to Synthetic Biology Applications

Abstract

This article explores the coevolution theory of the genetic code, which posits that the code's structure is an evolutionary imprint of biosynthetic relationships between amino acids. We examine foundational evidence from metabolic pathway analysis, including the proposed evolution from a GNC primeval code through SNS intermediate stages to the universal genetic code. For researchers and drug development professionals, we detail modern methodological approaches—including chemoproteomics, synthetic biology, and orthogonal translation systems—that leverage this relationship for natural product discovery and genetic code expansion. The review addresses challenges in pathway elucidation and optimization, presents validating evidence from comparative genomics and experimental evolution, and discusses implications for engineering novel biosynthetic pathways and developing therapeutic agents.

The Primordial Link: Tracing the Coevolution of Amino Acid Biosynthesis and the Genetic Code

The coevolution theory posits that the standard genetic code (SGC) is a historical record of the biosynthetic relationships between amino acids. This framework suggests that the code evolved by incorporating new amino acids as they were synthesized in primordial metabolic pathways, with these product amino acids inheriting codons from their biosynthetic precursors. This in-depth review synthesizes the core tenets of the theory, examines quantitative evidence supporting its claims, details modern experimental and computational protocols for its study, and discusses its profound implications for understanding the origin of life and engineering synthetic biological systems.

The origin of the universal genetic code is a fundamental problem in evolutionary biology. Among the various hypotheses proposed, the coevolution theory offers a compelling historical narrative. First comprehensively articulated by Wong [1], this theory postulates that the genetic code is not a frozen accident but rather an imprint of biosynthetic pathways [2] [3]. Its central premise is that the early code encoded only a small set of precursor amino acids, likely those available via prebiotic synthesis. As metabolic pathways evolved, new, biosynthetically derived amino acids were incorporated into the code's vocabulary. Critically, these product amino acids inherited their codons from their metabolic precursors, thereby creating the observed patterns in the modern codon table [2] [1] [3].

This review delineates the core principles of the coevolution theory, contrasting it with other major hypotheses. It then presents a detailed analysis of the supporting empirical and quantitative evidence, with a focus on statistically significant patterns within the genetic code. Furthermore, we provide a technical guide to the experimental and computational methodologies used to investigate coevolutionary dynamics. Finally, we explore the theory's application in modern synthetic biology, where its principles are being used to expand the genetic code and create novel organisms.

Core Tenets and Mechanistic Basis

The coevolution theory rests on several foundational pillars that distinguish it from stereochemical and adaptive error-minimization theories.

The Primordial Code and Code Expansion

The theory posits that the earliest genetic code was limited and incomplete. It likely encoded a small subset of the modern twenty amino acids, predominantly those simpler ones that could be formed by prebiotic chemistry or early metabolic pathways [4]. The theory identifies amino acids with GNN codons (where N is any nucleotide)—namely glycine, alanine, valine, aspartate, and glutamate—as strong candidates for this initial set, a observation noted to be statistically significant [2]. The code then expanded its coding capacity through a process of codon capture, whereby new amino acids were assigned codons that were previously used by their biosynthetic precursors [3].

The Biosynthetic Imprint and Precursor-Product Relationships

The defining tenet of the theory is that the structure of the standard genetic code preserves a record of amino acid biosynthetic relationships. When a new amino acid was biosynthesized from an existing one, the coding system coevolved, allowing the product amino acid to "take over" part of the codon domain of its precursor [2] [1]. For instance, the theory points to the close biosynthetic relationships between sibling amino acids like Ala-Ser, Ser-Gly, and Asp-Glu and notes that their collocation in the code table is not random [2]. This created the familiar block structure of the genetic code, where biosynthetically related amino acids often have codons that differ only in the first nucleotide [2].

The "Extended" Coevolution Theory

To address criticisms regarding unclear precursor-product relationships for certain amino acid pairs, an extended coevolution theory has been proposed [2]. This generalization maintains that the code is an imprint of biosynthetic relationships "even when defined by the non-amino acid molecules that are the precursors of some amino acids" [2]. This broader view incorporates the role of early metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, in defining biosynthetic proximity. It suggests that ancestral biosynthetic pathways occurred on tRNA-like molecules, facilitating the transfer of codons between biosynthetically linked amino acids as the mRNA template evolved [2].

Contrast with Other Major Theories

The coevolution theory offers a distinct narrative compared to other major hypotheses for the genetic code's origin. The stereochemical theory proposes that codon assignments are dictated by direct physicochemical affinities between amino acids and their codons or anticodons. The adaptive theory (or error-minimization theory) argues that the code evolved to be robust, minimizing the phenotypic impact of point mutations or translation errors [3]. In contrast, the coevolution theory is inherently historical, emphasizing a stepwise expansion driven by the evolving metabolism of the cell. It is important to note that these theories are not mutually exclusive; the standard genetic code is likely a product of multiple evolutionary forces, including aspects of coevolution, adaptive optimization, and potentially weak stereochemical interactions [3].

Quantitative Evidence and Data Analysis

The coevolution theory is supported by statistically significant patterns within the genetic code that correlate strongly with known biosynthetic pathways. The following tables summarize key evidence, including the early GNN codons and specific precursor-product pairs with their codon block assignments.

Table 1: Amino Acids Encoded by GNN Codons as Potential Early Additions

| Amino Acid | Codon(s) | Biosynthetic Family/Precursor | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | GGN | Serine family; 3-phosphoglycerate | Considered one of the earliest amino acids [2] |

| Alanine | GCN | Pyruvate family | Found at head of biosynthetic pathways [2] |

| Valine | GUN | Pyruvate family | Found at head of biosynthetic pathways [2] |

| Aspartic Acid | GAY | Oxaloacetate family | Early member of aspartate family [2] |

| Glutamic Acid | GAR | α-Ketoglutarate family | Early member of glutamate family [2] |

Table 2: Exemplar Precursor-Product Amino Acid Pairs in the Genetic Code

| Precursor Amino Acid | Product Amino Acid(s) | Biosynthetic Relationship | Codon Block Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serine | Tryptophan | Serine is a precursor to tryptophan [2] | UCN (Ser) -> UGG (Trp) |

| Aspartic Acid | Asparagine, Threonine, Methionine, Isoleucine | Aspartate is a common precursor [1] [3] | GAY (Asp) -> AAY (Asn); ACN (Thr, Met, Ile) |

| Glutamic Acid | Glutamine, Proline, Arginine | Glutamate is a common precursor [1] [3] | GAR (Glu) -> CAR (Gln); CCN (Pro); CGN, AGR (Arg) |

| Alanine | Valine | Shared pyruvate precursor; Ala -> Val biosynthesis [2] | GCN (Ala) and GUN (Val) are adjacent |

The organization of the genetic code into distinct biosynthetic families is not random. Statistical analysis has shown that the probability of observing the five major amino acid families (defined by a single amino acid precursor or a non-amino acid precursor) randomly organized in the code as they are is extremely low, on the order of 6 × 10⁻⁵ [2]. This provides strong quantitative support for the core tenet of the coevolution theory. Furthermore, the theory has been used to make successful predictions about the evolutionary root of the tree of life, suggesting the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) was close to modern Methanopyrus, based on tRNA paralog analysis [5] [6].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Research in this field relies on a combination of computational analysis of evolutionary patterns and experimental synthetic biology to test the theory's principles.

Computational Analysis of Coevolution

A primary method for investigating molecular coevolution involves identifying pairs of positions in proteins that evolve in a correlated fashion. The following workflow outlines a state-of-the-art phylogeny-based approach for detecting such coevolving residues, which can be applied to study enzymes in amino acid biosynthetic pathways.

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for identifying coevolving protein positions.

Protocol 1: Phylogeny-Based Detection of Coevolving Residues [7]

Input Data Preparation:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Curate a high-quality MSA of homologous protein sequences (e.g., enzymes from amino acid biosynthesis pathways).

- Phylogenetic Tree: Reconstruct a phylogenetic tree from the MSA using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods.

Ancestral State Reconstruction:

- Use maximum parsimony to infer the amino acid states at all ancestral nodes of the phylogenetic tree for each position in the MSA.

- From this reconstruction, identify all branches in the tree where amino acid changes occurred.

Counting Changes:

- For each pair of positions (i, j) in the protein, count two values:

- Concurrent Changes (Dij): The number of branches in the tree where both positions i and j changed.

- Separate Changes (Sij): The number of branches where only one of the two positions changed.

- For each pair of positions (i, j) in the protein, count two values:

Statistical Modeling and Outlier Detection:

- Model the expected relationship between S~i~ (separate changes for position i with all others) and D~i~ (concurrent changes for position i with all others) under the null hypothesis of no coevolution.

- A recent study found that applying a Box-Cox transformation to S~i~ before linear modeling resulted in "almost perfect precision and specificity" for identifying true coevolution [7].

- Statistically significant coevolving pairs are identified as outliers from this model, showing a significant depletion in separate changes (or enrichment in concurrent changes) [7].

Validation:

- Coevolving residues identified by this method tend to be close in the protein sequence and 3D structure, and are often slightly less solvent-exposed [7]. Validation against a known protein structure is a strong confirmation.

Simulating Genetic Code Evolution

Computational simulations provide a platform to test the factors influencing the emergence of a stable, robust genetic code.

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Simulation of Primitive Coding Systems [4]

Initialize Population:

- Generate a population of "primitive" genetic codes. These codes start by ambiguously encoding a limited set of amino acids (e.g., 3-7 labels, including stop signals), with codons assigned probabilistically to labels [4].

Define Evolutionary Operators:

- Mutation (m~c~): Randomly reassign codons to different labels within a code.

- Addition of New Amino Acids (m~l~): Allow codes to gradually incorporate new amino acids into their coding repertoire, increasing the number of labels from the initial set towards 21.

- Information Exchange (m~e~): Permit the horizontal transfer of genetic information (e.g., codon-to-label assignments) between different coding systems in the population [4].

Fitness Function and Selection:

- Define a fitness function (F) that measures the quality of a genetic code. This function typically evaluates:

- Coding Capacity: The ability to encode all 21 labels.

- Unambiguity: The clarity of the mapping from codons to labels, minimizing translational ambiguity.

- Error Robustness: The code's resilience to point mutations and translation errors [4].

- Select codes for the next generation with a probability proportional to their fitness.

- Define a fitness function (F) that measures the quality of a genetic code. This function typically evaluates:

Analysis:

- Run simulations over many generations and observe if the population converges on stable, unambiguous coding systems that resemble the standard genetic code in structure (e.g., block organization of synonymous codons). Studies have shown that information exchange (horizontal gene transfer) is a crucial factor that significantly accelerates the emergence of such optimal, universal codes [4].

Research at the intersection of coevolution theory, genomics, and synthetic biology relies on a specific set of conceptual and material tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Genetic Code Coevolution Studies

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| tRNA Paralog Analysis | Bioinformatic Method | To identify ancient tRNA gene duplications and trace the evolutionary history of codon assignments, informing on LUCA [5] [6]. |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction | Bioinformatic Method | To infer the sequences of ancient proteins and tRNAs, testing hypotheses about early code usage and enzyme evolution. |

| Maximum Parsimony/Likelihood | Computational Algorithm | For phylogenetic tree building and ancestral state reconstruction, fundamental to coevolution analysis [7]. |

| Orthogonal Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase/tRNA Pairs | Synthetic Biology Reagent | Engineered enzymes and tRNAs that do not cross-react with the host's native machinery, essential for incorporating unnatural amino acids [3]. |

| Unnatural Amino Acids (uAAs) | Chemical Reagent | Novel amino acids used to test code expansibility and create novel protein functions; over 30 have been incorporated in E. coli [3]. |

| Genome-Scale Synthesis & Recoding | Experimental Platform | The systematic replacement of all instances of a particular codon in an organism's genome, allowing its reassignment to a new amino acid [1]. |

Implications and Future Directions

The coevolution theory frames the genetic code as a mutable and evolvable system, a prediction powerfully validated by the creation of synthetic life forms with altered protein alphabets [5] [6] [1]. The theory provides a rational framework for these engineering efforts; by understanding which amino acids are biosynthetically related, researchers can make informed decisions about recruiting new codons for novel amino acids that are structurally or metabolically similar to natural ones.

Future research will continue to leverage integrative multi-omics approaches—genomics, transcriptomics, and microbiomics—to trace the deep evolutionary history of metabolic pathways and their relationship to the code's structure [8]. A major challenge and opportunity lie in moving from formal models to a credible scenario for the evolution of the coding principle itself, which will require a deeper integration of the coevolution theory with models for the origin of the ribosome and the translation system [3]. As we continue to dissect the biosynthetic imprint on the genetic code, we not only unravel the history of life's origin but also gain the tools to direct its future evolution.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis and the Vestiges of Early Code Evolution

The structure of the standard genetic code (SGC) is not arbitrary but represents a frozen accident, bearing the imprints of its evolutionary history. A central thesis in modern molecular evolution posits that the genetic code and metabolic pathways coevolved, with the code expanding as new amino acids became available through the stepwise development of biosynthesis. This coevolutionary process has left vestiges that can be traced through contemporary metabolic pathway analysis, offering a powerful lens to investigate life's deepest history. By integrating phylogenomic analyses with advanced computational tools for metabolic network reconstruction, researchers are now uncovering how early operational RNA codes, predating the modern SGC, facilitated the emergence of protein synthesis and folding. These investigations reveal that protein thermostability was a late evolutionary development, bolstering the hypothesis that proteins originated in the mild environments of the Archaean eon [9]. This technical guide examines the core methodologies, analytical frameworks, and reagent solutions enabling researchers to decode these ancient evolutionary signals through state-of-the-art metabolic pathway analysis.

Evolutionary Chronology of Code Formation

Reconstructing the Peptide-Based Fossil Record

The evolutionary timeline of genetic code emergence can be reconstructed through phylogenomic analysis of dipeptide sequences across diverse proteomes. A groundbreaking study analyzing 4.3 billion dipeptide sequences across 1,561 proteomes revealed a distinct chronology for the incorporation of amino acids into the evolving genetic code, supporting the early emergence of an operational RNA code in the acceptor arm of tRNA prior to the implementation of the standard genetic code in the anticodon loop [9].

Table 1: Evolutionary Chronology of Amino Acid Incorporation Based on Dipeptide Analysis

| Evolutionary Phase | Amino Acids | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Early Emergence | Leu, Ser, Tyr | Overlapping temporal emergence in dipeptide sequences |

| Subsequent Incorporation | Val, Ile, Met, Lys, Pro, Ala | Supported operational RNA code |

| Late Development | Protein thermostability determinants | Associated with mild Archaean environments |

This chronology aligns with the coevolution theory of genetic code development, which suggests that the code expanded alongside biosynthetic pathways, with newer amino acids inheriting codons from their metabolic precursors [4]. The synchronous appearance of dipeptide–antidipeptide sequences along this chronology further supports an ancestral duality of bidirectional coding operating at the proteome level [9].

Simulation Models of Primitive Coding Systems

Computational simulations based on evolutionary algorithms provide critical insights into the emergence of stable coding systems. These models typically begin with populations of primitive genetic codes that ambiguously encode only a limited set of amino acids (labels), which then undergo mutation, gradual incorporation of new amino acids, and information exchange [4].

The simulation process incorporates three fundamental processes:

- Mutation (

mc): Dynamic reassignment of labels to codons - Label incorporation (

ml): Gradual addition of new amino acids to the code - Information exchange (

me): Transfer of genetic information between evolving coding systems

These simulations demonstrate that evolution converges toward stable and unambiguous coding systems with higher coding capacity, facilitated by exchange of encoded information among evolving codes. A crucial finding is that this exchange significantly accelerates the emergence of genetic systems capable of encoding 21 labels (20 amino acids plus stop signal) [4].

Computational Frameworks for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Advanced Tools for Metabolic Network Reconstruction

The reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks require specialized bioinformatics tools that can handle the complexity of modern omics data. Several powerful platforms have been developed to address these challenges.

Table 2: Computational Tools for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Data Sources | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MetaDAG | Constructs reaction graphs and metabolic directed acyclic graphs (m-DAG) | KEGG | Taxonomy classification, diet analysis, comparative metabolism |

| KEGG | Reference database for pathway mapping | Curated pathway data | Pathway annotation, enzyme function prediction |

| Reactome | Signaling and metabolic pathway analysis | Curated pathway data | Pathway visualization, functional enrichment |

| MetaCyc | Metabolic pathway database | Curated experimental data | Metabolic engineering, enzyme function prediction |

| ORENZA | Orphan enzyme database | Experimental characterization | Identification of unassociated enzyme sequences |

MetaDAG represents a particularly innovative approach, implementing a metabolic directed acyclic graph (m-DAG) methodology that collapses strongly connected components of reaction graphs into single nodes called metabolic building blocks (MBBs). This representation significantly reduces network complexity while maintaining connectivity, enabling more efficient analysis of large-scale metabolic networks [10]. The tool can generate metabolic networks from various inputs, including specific organisms, groups of organisms, reactions, enzymes, or KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers, making it suitable for everything from individual microbial samples to complex metagenomic datasets.

Identifying and Plugging Metabolic Pathway Holes

A significant challenge in metabolic pathway analysis involves addressing "pathway holes" - enzymatic reactions without associated gene sequences. Recent research has developed sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines to identify candidate genes for these orphan enzyme activities through coevolutionary analysis [11].

The identification pipeline for pathway holes involves:

- Coevolution scoring: Calculating coevolution scores between human metabolic enzymes using orthologous protein families from OrthoDB

- Pathway analysis: Applying these scores to KEGG pathway charts to identify reactions with reliable connections but missing sequence associations

- Candidate selection: Focusing on reactions sandwiched between two known reactions in human pathways

- Validation: Experimental verification of predicted enzyme functions

This approach successfully identified C11orf54 (PTD012) as 3-dehydro-L-gulonate (BKG) decarboxylase, an enzyme that had remained uncharacterized for 65 years despite being assigned the EC number 4.1.1.34 in 1961 [11]. The protein belongs to the Domain of Unidentified Function family DUF1907 (PF08925) and features a high-resolution 3D structure with a bound Zn²⁺ ion coordinated by three conserved His residues.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Phylogenomic Reconstruction of Dipeptide Evolution

Objective: To reconstruct the evolutionary chronology of genetic code emergence through analysis of dipeptide sequences across diverse proteomes.

Methodology:

- Proteome Selection: Curate 1,561 representative proteomes spanning diverse phylogenetic lineages

- Dipeptide Enumeration: Extract and enumerate 4.3 billion dipeptide sequences from the proteomic datasets

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Reconstruct the evolutionary repertoire of 400 canonical dipeptides using phylogenomic methods

- Temporal Mapping: Map the emergence chronology of dipeptides containing specific amino acids

- Duality Assessment: Identify synchronous appearance of dipeptide–antidipeptide sequences

Key Parameters:

- Alignment algorithms for sequence comparison

- Molecular clock models for dating divergence events

- Statistical tests for assessing synchronous appearance

This protocol successfully revealed the overlapping emergence of dipeptides containing Leu, Ser, and Tyr, followed by those containing Val, Ile, Met, Lys, Pro, and Ala, providing empirical support for the operational RNA code hypothesis [9].

Machine Learning-Based Diagnostic Model Construction

Objective: To identify key metabolic and signaling pathways associated with complex traits through integrative bioinformatics analysis.

Methodology (as applied to Major Depressive Disorder [12]):

- Data Curation: Obtain gene expression datasets from public repositories (e.g., GEO) applying strict inclusion criteria

- Pathway Analysis: Perform Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) using Gene Ontology Biological Process (GOBP) and KEGG gene sets

- Immune Infiltration: Apply multiple immune infiltration algorithms (CIBERSORT, EPIC, ESTIMATE, MCPcounter, quanTIseq, TIMER, xCell)

- Differential Expression: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using linear models (limma package)

- Machine Learning: Employ 113 machine learning algorithms to construct diagnostic models, selecting optimal algorithms based on AUC values

- Risk Stratification: Divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on model scores for subgroup analysis

Validation:

- Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis across multiple datasets

- Calculation of area under the curve (AUC) values

- Residual analysis and goodness-of-fit testing

This approach identified the random forest algorithm (AUC = 0.788) as optimal for MDD diagnosis and revealed the cell-killing signaling pathway as consistently enriched across datasets [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | KEGG Pathway Database | Reference metabolic pathways for annotation and analysis |

| OrthoDB | Orthologous protein families for coevolutionary analysis | |

| UniProt | Protein sequence and functional information | |

| Protein Data Bank | 3D protein structures for functional inference | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MetaDAG | Metabolic network reconstruction and m-DAG generation |

| AlphaFold2 | Protein structure prediction for functional annotation | |

| Limma R Package | Differential expression analysis for omics data | |

| ClusterProfiler | Functional enrichment analysis of gene sets | |

| Analytical Platforms | Structural Prediction (pLDDT) | Assessment of protein structure prediction quality |

| Coevolution Scoring | Identification of functionally related genes | |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Diagnostic model construction and biomarker identification | |

| Experimental Resources | Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Public repository of functional genomics data |

| L1000 FWD Database | Drug perturbation signatures for drug discovery | |

| Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal | Drug sensitivity data for therapeutic prediction |

Integration of Structural Biology with Evolutionary Genomics

Recent advances in protein structure prediction, particularly through AlphaFold2, have enabled large-scale analysis of enzyme evolution across deep evolutionary timescales. A comprehensive study of 11,269 predicted and experimentally determined enzyme structures across 424 orthologue groups associated with 361 metabolic reactions revealed how metabolism shapes structural evolution across multiple scales [13].

Key findings from this structural-evolutionary analysis include:

- Metabolic Specialization: Enzymes from metabolically specialized species (e.g., fermenting vs. non-fermenting yeasts) show distinct patterns of structural conservation and divergence

- Pathway Constraints: Enzyme evolution is constrained by reaction mechanisms, interactions with metal ions and inhibitors, metabolic flux variability, and biosynthetic cost

- Hierarchical Patterns: Structural context dictates amino acid substitution rates, with surface residues evolving most rapidly and small-molecule-binding sites under selective constraints

- Cost Optimization: Metabolic cost optimization operates at both species and molecular levels, with high-abundance enzymes incorporating less energetically costly amino acids

This integration of structural biology with evolutionary genomics establishes a model in which enzyme evolution is intrinsically governed by catalytic function and shaped by metabolic niche, network architecture, cost, and molecular interactions [13].

The integration of metabolic pathway analysis with genetic code evolution research provides powerful insights for drug discovery and development. Computational metabolomics combines multiscale analysis with in silico approaches and molecular docking methods to enhance the detection of metabolic biomarkers and prediction of molecular interactions [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying drug modes of action, from pharmacokinetics to toxicity forecasting, thereby streamlining drug development pipelines.

Applications in anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiviral drug discovery demonstrate how these computational models can accelerate target validation and enhance the accuracy of therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, the identification of evolutionary constraints on enzyme evolution informs the selection of drug targets with appropriate conservation characteristics—highly conserved targets for broad-spectrum therapies versus divergent targets for specialized treatments [13].

The continuing evolution of bioinformatics tools and multi-omics integration approaches promises to further illuminate the deep evolutionary history encoded in metabolic pathways while providing increasingly sophisticated platforms for therapeutic development across diverse disease contexts.

The GNC Primeval Code Hypothesis and SNS Intermediate Evolutionary Stages

The origin of the genetic code remains a central mystery in understanding the emergence of life. The coevolution theory posits that the genetic code is an evolutionary imprint of biosynthetic relationships between amino acids, where the code expanded as new amino acids were synthesized through evolving metabolic pathways [2]. Within this theoretical framework, the GNC-SNS hypothesis provides a specific, stepwise model for how the genetic code originated from a simple four-codon system and evolved into the universal triplet code through definable intermediate stages [15]. This hypothesis addresses critical limitations of the RNA world hypothesis, which struggles to explain the spontaneous emergence of complex nucleotides and the codon-based organization of genetic information [16] [17]. The GNC-SNS model suggests that life originated from a [GADV]-protein world, where proteins composed of glycine (G), alanine (A), aspartic acid (D), and valine (V) could undergo pseudo-replication and establish the first peptide-based biochemical systems prior to the evolution of sophisticated nucleic acid replication [17].

Theoretical Foundation of the GNC-SNS Hypothesis

Core Postulates of the GNC-SNS Hypothesis

The GNC-SNS primitive genetic code hypothesis proposes that the universal genetic code evolved through two major evolutionary stages from a simpler precursor code [18] [15]:

- GNC Primeval Genetic Code: The first genetic code consisted of only four codons (GGC, GCC, GAC, GUC) encoding four amino acids (Gly, Ala, Asp, Val) - the [GADV] amino acids. This code was formally represented by triplets but functioned substantially as singlets.

- SNS Intermediate Genetic Code: The GNC code expanded to an SNS code, where S represents G or C, and N represents any nucleotide. This intermediate code contained 16 codons encoding 10 amino acids before finally expanding to the universal 64-codon table [15].

This evolutionary pathway is supported by the observation that proteins composed of [GADV]-amino acids can form the four fundamental structural elements found in modern proteins: hydrophobic and hydrophilic structures, α-helices, β-sheets, and turns/coils [15]. Furthermore, imaginary proteins encoded by the SNS code satisfy six conditions necessary for water-soluble globular protein formation [18].

Critical Weaknesses of the RNA World Hypothesis

The GNC-SNS hypothesis emerged from identified limitations in the prevailing RNA world hypothesis, which faces several fundamental challenges [16] [17]:

- Nucleotide Synthesis: Nucleotides have not been produced through prebiotic means and have not been detected in meteorites, despite the detection of nucleobases [16].

- RNA Synthesis Difficulty: The prebiotic synthesis of RNA is considered "quite difficult or most likely impossible" due to the complex chemical structure of nucleotides and the stability issues of ribose [16] [17].

- Self-Replication Paradox: RNA would need to maintain an unfolded state to function as a genetic template while simultaneously folding into stable tertiary structures to exhibit catalytic function - creating a fundamental contradiction [17].

- Information Formation: Genetic information composed of triplet codon sequences would never form stochastically by joining mononucleotides one by one [16].

These limitations prompted the development of alternative models, including the [GADV]-protein world hypothesis, which serves as the foundation for the GNC-SNS genetic code model [16].

Experimental Validation and Methodological Approaches

Computational Analysis of Protein Folding Potentials

Objective: To determine the minimum set of amino acids capable of forming proteins with structural properties similar to modern proteins.

Methodology: Researchers analyzed whether imaginary proteins composed of limited amino acid sets could satisfy the structural requirements for water-soluble globular protein formation [18] [17]. The analysis evaluated six key physicochemical properties:

- Hydropathy (hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity)

- α-helix formation capability

- β-sheet formation capability

- Turn/coil formation capability

- Acidic amino acid composition

- Basic amino acid composition

Implementation: The computational analysis involved generating virtual polypeptides using selected amino acid sets and calculating their physicochemical properties based on known amino acid structural indexes. The results were compared against the average values of extant proteins to determine if they fell within viable ranges for functional protein folding [17].

Key Finding: Proteins composed of [GADV]-amino acids encoded by the GNC codons satisfied four fundamental structural conditions (hydropathy, α-helix, β-sheet, and turn/coil formation capabilities) when approximately equal amounts of each amino acid were contained in the proteins [18] [17]. No other four-amino acid combination from the standard genetic code table could satisfy all these structural requirements, with the exception of the closely related GNG code [18].

Metabolic Pathway Analysis and Coevolution Theory

Objective: To trace the evolutionary pathway of the genetic code through analysis of modern amino acid biosynthetic pathways.

Methodology: The KEGG PATHWAY Database was used to extract and analyze metabolic pathways for amino acid biosynthesis [19]. Researchers examined:

- Precursor-product relationships between amino acids

- Chemical structures of amino acids and intermediate metabolites

- The order of amino acid incorporation into the genetic code based on biosynthetic complexity

Analytical Framework: The coevolution theory suggests that the genetic code expanded as new amino acid synthetic pathways evolved. When a new amino acid was synthesized through a newly formed metabolic pathway and accumulated in sufficient quantities, it could be incorporated into the expanding genetic code [19] [2]. This process required two conditions:

- Significant accumulation of the new amino acid in cells

- Functional enhancement of proteins synthesized using the expanded amino acid repertoire [19]

Key Insight: Analysis of biosynthetic relationships revealed that the first amino acids to evolve along these pathways are predominantly those codified by codons of the type GNN, supporting the primacy of the GNC code in early genetic code evolution [2].

Genomic Analysis of GC-Rich Non-Stop Frames

Objective: To identify potential evolutionary relics of primitive genetic codes in modern genomes.

Methodology: Researchers analyzed microbial genes from the GenomeNet Database, focusing on:

- Base compositions at three codon positions in GC-rich genes

- Non-stop frames on antisense strands of GC-rich genes (GC-NSF(a))

- The protein-folding potential of hypothetical proteins encoded by these sequences

Finding: The base composition format of highly GC-rich genes (65-75%) and hypothetical sequences of GC-NSF(a) approximate repetitions of SNS (where S means G or C), suggesting that SNS repetition sequences possess strong potential to function as genes [17]. This supports the hypothesis that the SNS code served as an intermediate in genetic code evolution.

Quantitative Data and Structural Evidence

Structural Properties of [GADV]-Proteins

Table 1: Protein Structural Formation Capabilities of Primitive Amino Acid Sets

| Amino Acid Set | Genetic Code | Number of Amino Acids | Hydropathy | α-helix | β-sheet | Turn/Coil | Acidic/ Basic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [GADV] | GNC | 4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| SNS-encoded | SNS | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Modern proteins | Universal | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Data derived from computational analyses of imaginary proteins indicates that [GADV]-proteins encoded by the GNC code can satisfy four fundamental structural requirements for protein folding, while SNS-encoded proteins containing 10 amino acids can satisfy all six conditions necessary for water-soluble globular protein formation [18] [17].

Amino Acid Biosynthetic Relationships

Table 2: Biosynthetic Families and Codon Domains in Genetic Code Evolution

| Biosynthetic Family | Precursor Amino Acid | Product Amino Acids | Codon Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartate | Aspartate (Asp) | Asparagine (Asn), Threonine (Thr), Methionine (Met), Lysine (Lys), Isoleucine (Ile) | GAY, AAY, ACY, AUY |

| Glutamate | Glutamate (Glu) | Glutamine (Gln), Proline (Pro), Arginine (Arg) | GAR, CAR, CCR, CGR |

| Pyruvate | Alanine (Ala) | Valine (Val), Leucine (Leu) | GCN, GUN, CUN, UUR |

| Serine | Serine (Ser) | Glycine (Gly), Cysteine (Cys) | UCN, GGN, UGY |

| Aromatic | Phenylalanine (Phe) | Tyrosine (Tyr), Tryptophan (Trp) | UUY, UAY, UGG |

The organization of the genetic code table reflects these biosynthetic relationships, with product amino acids typically located within the codon domain of their precursor amino acids [2]. This pattern provides strong support for the coevolution theory and the progressive expansion of the genetic code.

Evolutionary Pathway and Mechanism

From GNC to SNS to Universal Code

The GNC-SNS hypothesis proposes a clear evolutionary pathway for the genetic code [18] [15]:

- GNC Primeval Code: The first genetic code established correspondence relationships between four GNC codons and four [GADV]-amino acids.

- SNS Intermediate Code: The code expanded to include 16 SNS codons encoding 10 amino acids ([GADV] plus Glu, Leu, Pro, His, Gln, Arg).

- Universal Genetic Code: Further expansion led to the complete 64-codon table encoding 20 standard amino acids.

This evolutionary progression is supported by the observation that the GNC code represents the most simplified code that can generate proteins with structural diversity comparable to modern proteins, while the SNS code provides additional functional groups necessary for enhanced catalytic capabilities [18].

The Role of the Peptidated RNA World

The Peptidated RNA World concept bridges the transition between the RNA world and the modern protein-dominated world [5]. In this model:

- Early functional RNAs (fRNAs) covalently attached peptide prosthetic groups to enhance their catalytic capabilities

- These polypeptide prosthetic groups evolved to cooperate with host fRNAs

- Templates on fRNAs guided the binding of aminoacyl-RNA synthetase ribozymes (rARS) to synthesize specific peptide sequences

- Eventually, these polypeptide prosthetic groups detached from their host fRNAs to function as independent enzymes [5]

This model resolves the "information-need paradox" - that information-rich biopolymers are too long to arise spontaneously - by providing a mechanism for peptide sequences to evolve under the nurturing environment of host fRNAs [5].

Figure 1: Evolutionary Pathway from Prebiotic Chemistry to Modern Genetic Code

Research Tools and Experimental Applications

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Genetic Code Evolution Studies

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function/Application | Example Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG PATHWAY Database | Database | Analysis of amino acid biosynthetic pathways and metabolic relationships | Kanehisa Laboratories [19] |

| GenomeNet Database | Database | Genomic data for analysis of GC-rich genes and non-stop frames | Kyoto University [17] |

| Amino Acid Structural Indexes | Computational Parameters | Calculation of hydropathy, secondary structure formation potentials | Experimental literature [17] |

| Virtual Polypeptide Generation | Computational Algorithm | Testing protein-folding potential of limited amino acid sets | Custom implementation [18] |

| Metabolic Pathway Analysis | Analytical Framework | Tracing biosynthetic relationships between amino acids | KEGG-based analysis [19] |

Methodological Framework for Hypothesis Testing

The experimental validation of the GNC-SNS hypothesis relies on a multidisciplinary approach combining computational, biochemical, and evolutionary analyses:

- Computational Protein Modeling: Using structural indexes to evaluate the folding potential of polypeptides composed of limited amino acid sets.

- Comparative Genomics: Analyzing sequence patterns in modern genomes to identify potential evolutionary relics of primitive genetic codes.

- Metabolic Pathway Analysis: Tracing biosynthetic relationships between amino acids to reconstruct the expansion history of the genetic code.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Studying tRNA and rRNA evolution to understand the development of the translation apparatus.

Figure 2: Methodological Framework for Hypothesis Testing

The GNC-SNS hypothesis, framed within the broader context of the coevolution theory, provides a compelling model for the stepwise evolution of the genetic code from a simple four-codon system to the universal triplet code. This model successfully addresses several critical limitations of the RNA world hypothesis while providing testable predictions about the early evolution of biological information systems.

Key strengths of the GNC-SNS model include its ability to explain:

- The emergence of structurally diverse proteins from a limited amino acid repertoire

- The biosynthetic relationships evident in the organization of the modern genetic code table

- The transition from a peptide-based early world to the nucleic acid-dominated systems of modern biology

Future research directions should focus on experimental validation of the pseudo-replication concept for [GADV]-proteins, further elucidation of biosynthetic pathways for early amino acids, and exploration of the biochemical mechanisms that facilitated the transition from the SNS code to the universal genetic code. The integration of this model with understanding of early metabolic pathways continues to provide insights into one of biology's most fundamental questions: the origin of the genetic code and the emergence of life itself.

Biosynthetic Families and Their Representation in Codon Domains

The universal genetic code is not a random assignment of codons to amino acids but rather a historical record of the biosynthetic relationships between amino acids and their coevolution with the emerging translation machinery [20] [2]. The coevolution theory posits that the genetic code structure is an imprint of biosynthetic pathways, where precursor amino acids donated parts of their codon domains to their biosynthetic products as the code evolved and expanded [2]. This extended coevolution theory further suggests that the genetic code reflects biosynthetic relationships "even when defined by the non-amino acid molecules that are the precursors of some amino acids" [2]. This framework provides profound implications for understanding the fundamental organization of life, as the very structure of the genetic code preserves a molecular fossil record of early metabolic evolution.

The representation of biosynthetic families within codon domains demonstrates remarkable organizational principles. Analysis of proteome-wide dipeptide sequences has provided a evolutionary chronology supporting the early emergence of an operational RNA code in the acceptor arm of tRNA prior to the implementation of the standard genetic code in the anticodon loop [9]. This timeline reveals that specific amino acids with particular biosynthetic relationships, including those containing Leu, Ser, Tyr, Val, Ile, Met, Lys, Pro, and Ala, were recruited in overlapping temporal patterns that reinforced the operational code [9]. The synchronous appearance of dipeptide-antidipeptide sequences along this evolutionary chronology further supports an ancestral duality of bidirectional coding operating at the proteome level [9].

Theoretical Foundations: Genetic Code Structure and Biosynthetic Relationships

Organizational Principles of the Genetic Code

The genetic code exhibits a sophisticated architecture where the second codon position (P2) plays a determinative role in specifying amino acid properties [20]. When U occupies position 2, all encoded amino acids are strongly hydrophobic without exception, while with A in position 2, all amino acids are strongly hydrophilic, also without exception [20]. With C or G in position 2, most codons code for semipolar amino acids [20]. This organization suggests the primordial code likely specified three fundamental types of amino acids: hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and semipolar.

The three codon positions exhibit dramatically different variation constraints across genomes. Position 2 varies only 12% in GC content across organisms with different genomic GC compositions, compared to 31% variation for position 1 and 80% variation for position 3 [20]. These differential constraints reflect the principle of negative selection, where functionally more important sites evolve more slowly [20]. Thus, P2 in codons is most important for specifying the nature of the amino acid, P1 is of intermediate importance for specifying the specific amino acid, and P3 is least important and highly redundant [20].

Biosynthetic Families and Their Codon Domain Relationships

Amino acids with similar biosynthetic origins tend to occupy contiguous codon domains in the genetic code table [2]. Statistical analysis indicates that the five families of amino acids defined by a single amino acid precursor or a non-amino acid precursor would be randomly observed in the genetic code with a probability of just 6×10⁻⁵, strongly supporting non-random organization based on biosynthetic relationships [2].

Table 1: Biosynthetic Families and Their Codon Representations

| Biosynthetic Family | Precursor Molecule | Amino Acid Members | Codon Domain Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate Family | Pyruvate | Ala, Val, Leu, Ser* | GCN (Ala), GUN (Val), UUR (Leu) |

| Aspartate Family | Aspartate | Asp, Asn, Lys, Thr, Met, Ile | GAY (Asp), AAY (Asn), AAR (Lys) |

| Glutamate Family | Glutamate | Glu, Gln, Pro, Arg | GAR (Glu), CAR (Gln), CCN (Pro) |

| Serine Family | Serine | Ser, Gly, Cys, Trp | UCN (Ser), GGN (Gly), UGY (Cys) |

| Aromatic Family | Phosphoenolpyruvate + Erythrose-4-P | Phe, Tyr, Trp, His | UUY (Phe), UAY (Tyr), CAY (His) |

*Serine has multiple biosynthetic origins including glycolysis intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate [2]

The close biosynthetic relationships between sibling amino acids Ala-Ser, Ser-Gly, Asp-Glu, and Ala-Val are not randomly distributed in the genetic code table and reinforce the hypothesis that biosynthetic relationships between these six amino acids played a crucial role in defining the earliest phases of genetic code origin [2]. This finding led to the hypothesis of an early GNS code reflecting these fundamental biosynthetic relationships that preceded the modern genetic code [2].

Analytical Methods for Studying Codon Domain-Biosynthetic Relationships

Codon Usage Bias Analysis

Codon usage bias (CUB), the non-uniform usage of synonymous codons, occurs across all domains of life and provides insights into evolutionary forces shaping genomes [21]. Analyzing CUB patterns can reveal signatures of natural selection, mutation pressure, and genetic drift acting on coding sequences. The Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) value is calculated as:

RSCU = gᵢⱼ / (Σⱼ gᵢⱼ / nᵢ)

where gᵢⱼ represents the observed count of the i-th codon for the j-th amino acid, and nᵢ denotes the number of synonymous codons for the j-th amino acid [22]. An RSCU value of 1.0 indicates no codon usage bias, while values greater than 1.0 and less than 1.0 represent positive and negative bias, respectively [22]. Codons with RSCU values exceeding 1.6 are considered "over-represented," while those with values below 0.6 are "under-represented" [22].

The Effective Number of Codons (ENC) analysis measures the degree of codon usage bias independent of sequence length and amino acid composition, ranging from 20 (extremely biased) to 61 (no bias) [22]. ENC plots comparing observed ENC values against expected values under GC3 content can reveal whether mutation pressure or natural selection is the dominant force shaping codon usage patterns.

Diagram 1: Codon usage bias analysis workflow

Phylogenomic Reconstruction of Code Evolution

Phylogenomic approaches can reconstruct the evolutionary chronology of genetic code expansion by analyzing dipeptide sequences across diverse proteomes. One recent study analyzed 4.3 billion dipeptide sequences across 1,561 proteomes to reconstruct the evolutionary repertoire of 400 canonical dipeptides [9]. This approach revealed the temporal emergence of dipeptides containing specific amino acids that supported the operational RNA code hypothesis.

The methodology involves:

- Proteome Data Collection: Compiling complete proteomes from diverse taxonomic lineages

- Dipeptide Frequency Analysis: Calculating occurrence frequencies of all 400 possible dipeptide pairs

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Building evolutionary trees based on dipeptide usage patterns

- Chronology Mapping: Inferring the temporal sequence of amino acid recruitment into the genetic code

This phylogenomic approach has revealed that protein thermostability was a late evolutionary development, bolstering the hypothesis of a mild-environment origin of proteins during the Archaean eon [9].

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Identification and Analysis

Bioinformatic analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) enables the connection between genetic code organization and natural product biosynthesis. The antiSMASH (antibiotics and secondary metabolite analysis shell) tool is widely used for identifying and comparing BGCs in bacterial genomes [23]. Advanced versions like antiSMASH 7.0 employ detection settings that enable KnownClusterBlast, ClusterBlast, SubClusterBlast, and Pfam domain annotation to comprehensively characterize BGCs [23].

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Biosynthetic Family Research |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | BGC identification and comparison | Predicts BGC types and their structural diversity |

| BiG-SCAPE | Gene Cluster Family analysis | Groups BGCs into families based on domain sequence similarity |

| PRISM | Natural product structure prediction | Predicts natural product structures from BGC sequences |

| RODEO | RiPP precursor peptide identification | Identifies ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides |

| Deep-BGC | BGC detection with machine learning | Uses classifier to identify BGCs and predict their products |

| ARTS | Antibiotic Resistance Target Seeker | Identifies resistance genes within BGCs |

BGC clustering analysis using tools like BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering and Prospecting Engine) groups BGCs into Gene Cluster Families (GCFs) based on domain sequence similarity [23]. This analysis can be performed at multiple similarity cutoffs (e.g., 10% and 30%) to resolve both fine-scale and broad gene cluster families [23]. For example, analysis of vibrioferrin-producing BGCs showed that at 10% similarity they formed 12 families, while at 30% similarity they merged into a single gene cluster family [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Comprehensive Codon Usage Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps for analyzing codon usage patterns in relation to biosynthetic families, adapted from methodologies used in viral and bacterial genome studies [22] [24].

Materials and Reagents:

- Genomic sequences in FASTA format

- Computing environment with R or Python installed

- Bioinformatics packages: seqinr (R), BioPython, CodonW

- Multiple sequence alignment software (e.g., ClustalW, MAFFT)

Procedure:

- Sequence Retrieval and Curation

- Retrieve coding sequences from databases (e.g., GenBank, RefSeq)

- Filter sequences by length and completeness

- Verify annotation accuracy and correct reading frames

Compositional Analysis

- Calculate mononucleotide (A, C, U/T, G) frequencies

- Determine GC content at first (GC1s), second (GC2s), and third (GC3s) codon positions

- Compute mean GC content of first and second positions (GC12s)

Codon Usage Bias Metrics

- Calculate Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) values

- Compute Effective Number of Codons (ENC)

- Perform neutrality plot analysis (GC12 vs GC3)

- Conduct parity rule 2 (PR2) bias analysis

Evolutionary Force Discrimination

- Compare observed vs expected ENC values under mutational equilibrium

- Analyze correlation between codon positions

- Perform multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., correspondence analysis)

Biosynthetic Family Grouping

- Group amino acids by biosynthetic pathways

- Compare CUB patterns within and between biosynthetic families

- Statistical testing of CUB differences (t-tests, ANOVA)

This protocol typically requires 2-3 days for a medium-sized dataset (50-100 genes) and can be scaled for larger genomic analyses.

Protocol: Phylogenomic Reconstruction of Code Evolution

This protocol describes the methodology for reconstructing genetic code evolution through dipeptide sequence analysis across proteomes [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Proteome datasets from diverse organisms

- High-performance computing cluster

- Phylogenetic analysis software (e.g., MEGA11, IQ-TREE, RAxML)

- Multiple sequence alignment tools (e.g., Clustal Omega, MUSCLE)

Procedure:

- Proteome Data Collection

- Compile complete proteomes from public databases (UniProt, NCBI)

- Ensure taxonomic representation across evolutionary lineages

- Quality control for sequence completeness and annotation

Dipeptide Frequency Analysis

- Extract all dipeptide sequences from each proteome

- Calculate normalized frequencies for all 400 possible dipeptides

- Compute enrichment/depletion relative to random expectations

Phylogenetic Tree Construction

- Select appropriate marker genes or use whole-proteome approaches

- Determine best-fit substitution model (e.g., GTR+G+I)

- Construct maximum likelihood phylogeny with bootstrap support

Ancestral State Reconstruction

- Map dipeptide usage patterns onto phylogenetic tree

- Reconstruct ancestral dipeptide repertoires

- Infer chronological sequence of amino acid recruitment

Statistical Validation

- Apply statistical tests for chronological patterns

- Compare with alternative evolutionary scenarios

- Validate with independent molecular dating approaches

This advanced protocol requires significant computational resources and typically takes 1-2 weeks for a dataset of 100-200 proteomes, depending on sequence length and complexity.

Diagram 2: Phylogenomic reconstruction workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Biosynthetic Code Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH 7.0 | BGC identification and annotation | Predicts biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic data |

| BiG-SCAPE 2.0 | BGC similarity network analysis | Groups BGCs into gene cluster families based on sequence similarity |

| seqinr R Package | Codon usage analysis | Computes RSCU, ENC, and other codon usage statistics |

| RDP4 | Recombination detection | Identifies potential recombination events in coding sequences |

| MEGA11 | Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis | Constructs phylogenetic trees and performs evolutionary analyses |

| Modelfinder | Best-fit substitution model selection | Identifies optimal nucleotide/amino acid substitution models |

| IQ-TREE | Maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference | Reconstructs evolutionary relationships with model selection |

| Cytoscape 3.10.3 | Biological network visualization | Visualizes BGC similarity networks and functional relationships |

| DIVEIN Software | Evolutionary distance analysis | Estimates pairwise genetic distances between sequences |

| Geneious Prime | Sequence alignment and annotation | Aligns and annotates BGC regions and core genes |

Case Studies and Research Applications

Case Study: Duck Hepatitis Virus 1 Codon Usage Patterns

Analysis of Duck Hepatitis Virus 1 (DHV-1) genomes revealed distinct codon usage patterns across three phylogenetic groups (Ia, Ib, and II) with different evolutionary dynamics [22]. The DHV-1 genome showed a strong preference for A/U-ended codons and underrepresentation of CG dinucleotides, with low overall codon usage bias suggesting host adaptation [22]. The three phylogroups exhibited distinct evolutionary trends: phylogroups Ia and Ib showed evidence of neutral evolution with selective pressure, while phylogroup II evolution was primarily driven by random genetic drift [22].

This case study demonstrates how codon usage analysis can reveal evolutionary dynamics and host adaptation strategies in viral pathogens, with implications for understanding pathogen evolution and developing control measures.

Case Study: Marine Bacterial Biosynthetic Diversity

Analysis of 199 marine bacterial genomes from 21 species identified 29 distinct BGC types, with non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), betalactone, and NRPS-independent siderophores (NI-siderophores) being most predominant [23]. The study focused on vibrioferrin-producing BGCs across Vibrio harveyi, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Photobacterium damselae, revealing high genetic variability in accessory genes while core biosynthetic genes remained conserved [23].

This research highlights the biosynthetic diversity of marine bacteria and the structural plasticity of BGCs, which may influence functional properties like iron-chelation and microbial interactions [23]. Such studies contribute to natural product bioprospecting and underscore the potential for discovering novel bioactive compounds from marine microbes.

The representation of biosynthetic families in codon domains provides a compelling window into the early evolution of the genetic code and its coevolution with metabolic pathways. The evidence supporting the extended coevolution theory continues to accumulate, with phylogenomic analyses revealing detailed chronologies of amino acid recruitment and code expansion [9] [2]. The organizational principles of the genetic code, particularly the determinative role of the second codon position in specifying amino acid properties, reflect deep evolutionary constraints that likely originated in the operational RNA code of the acceptor arm of tRNA [20] [9].

Future research directions in this field should include:

- Expanded Phylogenomic Analyses: Applying dipeptide chronology methods to larger and more diverse proteome datasets

- Experimental Validation: Developing experimental systems to test predictions of the coevolution theory

- Integration with Origin of Life Studies: Connecting genetic code evolution with broader scenarios for life's emergence

- Applied Applications: Leveraging biosynthetic family relationships for drug discovery and natural product engineering

- Machine Learning Approaches: Implementing advanced computational methods to predict biosynthetic pathways from genomic data

The study of biosynthetic families and their representation in codon domains remains a vibrant research area with profound implications for understanding life's fundamental organization and evolutionary history.

The extended coevolution theory represents a significant refinement of the classic coevolution theory of the genetic code's origin. While maintaining the core premise that the genetic code structure reflects biosynthetic relationships between amino acids, the extended theory specifically incorporates the crucial role of non-amino acid precursors and the earliest amino acids emerging from central metabolic pathways. This framework resolves long-standing difficulties in defining the initial phases of code evolution and provides a more comprehensive mechanistic explanation for the observed patterns in the modern genetic code. The theory posits that the first amino acids to be incorporated were predominantly those synthesized from intermediates of energy metabolism and codified by GNN codons, with their biosynthetic relationships directly imprinting on the code's structure through interactions on tRNA-like molecules.

Foundations of the Classic Coevolution Theory

The classic coevolution theory, first formally proposed by Wong, posits that the genetic code originated and evolved in parallel with the development of amino acid biosynthetic pathways [25]. The theory contends that the code's structure represents an evolutionary map of biosynthetic relationships, wherein a small set of precursor amino acids were initially encoded. As new product amino acids were biosynthetically derived from these precursors, they inherited part or all of the codon domain of their metabolic precursors [25]. This process resulted in the non-random organization of the genetic code table, where biosynthetically related amino acids tend to possess contiguous or similar codons.

Limitations and the Need for an Extension

Despite its explanatory power, the classic coevolution theory faced significant challenges. It struggled to clearly define the very earliest phases of genetic code origin and did not fully attribute a role to the biosynthetic relationships between the first amino acids that evolved along pathways of energetic metabolism [26]. Furthermore, criticisms highlighted that certain amino acid pairs cited by the theory appeared to have unclear biosynthetic relationships [26]. These difficulties necessitated a refinement of the theory, leading to the development of the extended coevolution theory.

Core Principles of the Extended Coevolution Theory

The extended coevolution theory generalizes the classic framework by stating that "the genetic code is simply an imprint of the biosynthetic relationships between amino acids, even when defined by the non-amino acid molecules that are the precursors of some amino acids" [26]. This extension incorporates two crucial conceptual advances:

- Role of Non-Amino Acid Precursors: The theory explicitly recognizes that the biosynthetic proximity between amino acids, including relationships defined by their common non-amino acid precursors (e.g., intermediates of glycolysis and the citric acid cycle), played a fundamental role in organizing the code.

- Mechanistic Framework: The structuring occurred because ancestral biosynthetic pathways operated on tRNA-like molecules, enabling a direct coevolution between these pathways and the genetic code's organization. This involved the transfer of tRNA-like molecules between biosynthetically related amino acids, facilitating the reassignment of codons from precursor to product amino acids as the mRNA template evolved [26].

Key Evidence and Quantitative Data

The Primacy of GNN Codons and Early Amino Acids

A critical prediction of the extended theory is that the first amino acids to be incorporated into the code were those synthesized from and closely linked to central metabolic pathways. Statistical analysis strongly supports this, revealing that amino acids encoded by GNN codons are predominantly found at the beginning of these pathways.

Table 1: Early Amino Acids and Their Codon Assignments

| Amino Acid | Codon Type | Biosynthetic Family | Metabolic Precursor (Non-Amino Acid) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine | GGN | Serine Family | 3-Phosphoglycerate |

| Alanine | GCN | Pyruvate Family | Pyruvate |

| Valine | GUN | Pyruvate Family | Pyruvate |

| Serine | UCN, AGY | Serine Family | 3-Phosphoglycerate |

| Aspartate | GAY | Aspartate Family | Oxaloacetate |

| Glutamate | GAR | Glutamate Family | 2-Oxoglutarate |

The observation that five amino acids codified by GNN codons (Gly, Ala, Val, Asp, Glu) are found at the head of four major biosynthetic pathways is statistically significant and unlikely to be a random occurrence [26]. This points to a GNN-based primordial code.

Biosynthetic Sibling Relationships

The extended theory identifies specific, statistically non-random biosynthetic relationships between pairs of "sibling" amino acids that were crucial in the code's earliest phases. These include Ala-Ser, Ser-Gly, Asp-Glu, and Ala-Val [26]. Their close placement in the genetic code table is a direct imprint of their biosynthetic linkage, either through shared non-amino acid precursors or direct interconversion.

Table 2: Key Sibling Amino Acid Relationships in Code Organization

| Sibling Pair | Biosynthetic Relationship | Codon Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Ala-Ser | Both derive from 3-phosphoglycerate/pyruvate pathways | GCN (Ala) and UCN/AGY (Ser) are adjacent |

| Ser-Gly | Serine is a direct precursor to Glycine | UCN/AGY (Ser) and GGN (Gly) share the second base |

| Asp-Glu | Direct structural analogs from similar TCA cycle precursors (oxaloacetate, 2-oxoglutarate) | GAY (Asp) and GAR (Glu) share the first base |

| Ala-Val | Both derive from pyruvate | GCN (Ala) and GUN (Val) share the first base |

The GNS Code: A Hypothetical Framework for the Earliest Code

The evidence for the primacy of GNN codons and the specific sibling relationships leads to the hypothesis of a very early GNS code, where N is any nucleotide and S signifies G or C [26] [27]. This hypothetical code would have primarily encoded the six critical early amino acids (Gly, Ala, Val, Asp, Glu, Ser) whose biosynthetic relationships are foundational. The GNS framework elegantly resolves the classic theory's difficulty in defining the initial phases by providing a plausible, simple precursor state from which the modern code could evolve through the coevolution mechanism.

Proposed Evolutionary Pathway from the GNS Code

The following diagram illustrates the proposed evolutionary pathway from the initial GNS code to the modern standard genetic code, driven by the coevolution mechanism.

Evolutionary Pathway of the Genetic Code

Experimental Corroboration and Molecular Fossils

Key Experimental Protocols

A strong line of evidence supporting the theory comes from the existence of molecular fossils—modern biochemical pathways that reflect the ancient mechanisms proposed by the theory.

Protocol 1: Identifying tRNA-Dependent Amino Acid Biosynthesis

- Objective: To demonstrate that the biosynthesis of certain amino acids directly on tRNA molecules is a widespread phenomenon.

- Methodology:

- Isolate tRNA molecules for specific amino acids (e.g., tRNA^Gln, tRNA^Asn, tRNA^Sec) from various archaea and bacteria.

- Perform in vitro aminoacylation assays using non-cognate amino acids (e.g., Glu onto tRNA^Gln, Asp onto tRNA^Asn).

- Identify and purify the corresponding amidotransferase enzymes that convert the mischarged amino acid to the correct one (e.g., Glu-tRNA^Gln → Gln-tRNA^Gln).

- Interpretation: The persistence of these indirect pathways, which directly link the biosynthesis of an amino acid to its cognate tRNA, is interpreted as a molecular fossil of a time when such tRNA-dependent transformations were the norm, precisely as predicted by the coevolution theory [25].

Protocol 2: Metabolic Pathway Analysis with KEGG Database

- Objective: To trace the precursor-product relationships between amino acids and their correlation with codon assignments.

- Methodology:

- Extract amino acid metabolic pathways from the KEGG PATHWAY database [28].

- Map the biosynthetic families, noting the specific non-amino acid precursors (e.g., pyruvate, oxaloacetate).

- Correlate the position of an amino acid in its biosynthetic pathway with the first base of its codons and its physical proximity to related amino acids in the genetic code table.

- Interpretation: A strong correlation, where amino acids from the same biosynthetic family share the first base of their codons and are clustered in the code table, provides statistical support for the theory [26] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Genetic Code Origins

| Research Reagent / Method | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| KEGG PATHWAY Database | A knowledge base for systematic analysis of metabolic pathways and networks, essential for tracing amino acid biosynthetic relationships [28]. |

| In vitro Aminoacylation Assays | Used to study the specificity of tRNA charging by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and to identify non-canonical charging pathways. |

| Amidotransferase Enzymes (e.g., GatCAB, GatDE) | Key reagents to demonstrate the conversion of a mischarged amino acid on a tRNA to the correct one (e.g., Glu-tRNA^Gln to Gln-tRNA^Gln) [25]. |

| Evolutionary Algorithms / Computational Simulations | Used to model the evolution of genetic codes from ambiguous, primitive systems to stable, unambiguous codes under constraints like mutation and biosynthetic expansion [4]. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis of tRNA Sequences | Allows for the reconstruction of evolutionary relationships between tRNAs, testing predictions about their common ancestry within biosynthetic families. |

Implications and Synthesis with Other Theories

The extended coevolution theory has profound implications. It suggests that ancestral metabolism, at least for amino acids, took place on tRNA-like molecules [25]. This provides a direct mechanistic link between the world of RNA catalysis and the emergence of encoded protein synthesis.

The theory is not necessarily mutually exclusive with other hypotheses. For instance, the adaptive theory, which posits that the code was optimized to minimize the phenotypic impact of mutations or translation errors, can operate in concert with coevolution. A recent synthesis suggests that while the biosynthetic relationships (coevolution) primarily organized the rows of the genetic code table, natural selection acting on physicochemical properties (like partition energy) optimized the allocation of amino acids to its columns [29] [4]. In this view, the code's structure is a palimpsest, recording both its biosynthetic history and subsequent adaptive refinement.

The extended coevolution theory represents the most complete and empirically supported framework for understanding the origin of the genetic code's structure. By incorporating the role of non-amino acid precursors from central metabolism and the pivotal biosynthetic relationships between the earliest amino acids (most notably those encoded by GNN codons), it overcomes the limitations of the classic theory. The hypothesis of an initial GNS code, the corroborating evidence from tRNA-dependent biosynthesis, and the theory's ability to be tested via bioinformatic and biochemical protocols solidify its status as a cornerstone of research into the origin of life. Future work will continue to elucidate how this coevolutionary interplay between metabolism and information storage drove the transition from a primitive RNA world to the central dogma of biology. ```

The "RNA World" hypothesis represents a fundamental pillar of origins of life theory, proposing that self-replicating RNA molecules served as both genetic information carriers and catalytic entities before the evolution of DNA and proteins [30] [31]. This concept emerged from the discovery that RNA possesses dual capabilities: information storage through complementary base pairing and catalytic functions through ribozymes [32] [30]. The hypothesis gained significant support with the recognition that the ribosome's active site for peptide bond formation is composed primarily of RNA, making it essentially a ribozyme [32] [33].

However, a growing body of evidence challenges the notion of an RNA world existing independently of peptides and amino acids. This whitepaper synthesizes recent research supporting an alternative framework: the "Peptidated RNA World," where RNA and peptides co-evolved from life's earliest stages. This perspective addresses critical limitations of the pure RNA world scenario, including the chemical instability of RNA, the catalytic limitations of ribozymes compared to proteins, and the enigmatic emergence of the genetic code [34] [35]. We argue that life originated through a reciprocal partnership between peptides and nucleotides, where both contributed to early catalysis and information coding, eventually leading to the sophisticated biological systems observed today.

Theoretical Foundation: The Case for Molecular Cooperation

Limitations of a Pure RNA World

The traditional RNA world hypothesis faces several substantial challenges that undermine its plausibility as a standalone framework:

- Prebiotic Synthesis Challenges: Laboratory simulations of prebiotic conditions typically produce intractable mixtures of organic compounds rather than specific RNA precursors. The formation of β-D-nucleoside 5′-phosphates and their subsequent activation for polymerization remains chemically problematic under plausible early Earth conditions [32].

- Regioselectivity Issues: Non-enzymatic polymerization of nucleotides predominantly yields 2',5'-phosphodiester linkages rather than the biologically relevant 3',5'- linkages, resulting in structurally compromised oligonucleotides [32].

- Catalytic Limitations: While ribozymes demonstrate diverse catalytic capabilities, their reaction rates and versatility generally fall short of protein-based enzymes, creating a catalytic efficiency gap [30].

- The Coding Paradox: The RNA world hypothesis provides no clear transitional pathway for the emergence of the genetic code, which represents a fundamental chicken-and-egg conundrum: how could RNA-based life evolve the complex system of translation without pre-existing specific catalysts? [36] [35]

The Coevolutionary Framework

The Peptidated RNA World perspective addresses these limitations through several key principles:

- Reciprocal Catalysis: Early peptides and RNA molecules likely engaged in mutually beneficial interactions where each enhanced the stability and functionality of the other. Short peptides could protect RNA from degradation by Mg²⁺ ions or help stabilize specific RNA conformations [34].

- Structural Complementarity: Early oligopeptides and oligonucleotides may have interacted through specific stereochemical complementarity. The repeating hydrogen bonds between ribose 2'-OH groups and peptide carbonyl oxygen atoms suggest a possible basis for reciprocal autocatalysis [35].

- Gradual Specialization: Rather than appearing fully formed, the distinct advantages of RNA (information storage) and proteins (catalytic power) emerged gradually from simpler peptide-RNA complexes [35].

- Operational Code Precedence: Evidence suggests that an early "operational RNA code" existed in the acceptor arm of tRNA before the implementation of the standard genetic code in the anticodon loop, providing a transitional state in coding evolution [9] [37].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of RNA World vs. Peptidated RNA World Models

| Aspect | Pure RNA World | Peptidated RNA World |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Catalysts | Ribozymes exclusively | Ribozymes and simple peptides |

| Information Storage | RNA primarily | RNA with peptide contributions |

| Key Strength | Self-replication potential | Integrated functionality |

| Main Limitation | Prebiotic plausibility | Complexity of interactions |

| Genetic Code Origin | Late development | Early operational code |

| Experimental Support | Ribozyme catalysis | Peptide-RNA co-catalysis |

Key Experimental Evidence

Direct Peptide Synthesis on RNA