Comparative Phylodynamics for Outbreak Source Attribution: Methodologies, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of phylodynamic methods for outbreak source attribution, tailored for researchers and public health professionals.

Comparative Phylodynamics for Outbreak Source Attribution: Methodologies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of phylodynamic methods for outbreak source attribution, tailored for researchers and public health professionals. It explores the foundational principles of phylodynamics, reviews and contrasts major methodological frameworks—from Bayesian phylogeography to scalable agent-based models—and addresses key challenges including computational scalability, sampling bias, and model misspecification. By synthesizing insights from recent SARS-CoV-2 studies and novel computational tools, it offers a validated guide for selecting and optimizing methods to accurately reconstruct transmission trees and identify outbreak origins, ultimately enhancing genomic surveillance and public health response.

Foundations of Phylodynamics: Core Principles for Source Attribution

Defining Phylodynamics and Its Role in Genomic Epidemiology

Phylodynamics is an interdisciplinary field that combines evolutionary biology with epidemiology to generate evidence about the spread and source of pathogens by exploiting the genomic signature left by ongoing evolution during transmission [1]. This approach allows researchers to corroborate findings from traditional epidemiological modeling and provides deeper insights where conventional case data over time and space may be insufficient [1]. The foundation of phylodynamics relies on "measurable evolution"—the phenomenon where pathogen molecular evolution occurs on the same timescale as transmission, making accumulated genetic diversity informative about the timing of transmission events [1].

During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, phylodynamics experienced more intense application than ever before, establishing it as a core component of coordinated outbreak responses [1] [2]. The field has made significant contributions to understanding the spread of various pathogens, including Ebola, Zika, and HIV, by capturing transmission dynamics in time and space that would otherwise remain inaccessible through traditional epidemiological analysis alone [1].

Core Concepts and Foundational Models

Theoretical Framework and Key Assumptions

Phylodynamic analysis requires pathogen genome sequences and their sampling times from infected hosts. Two key assumptions enable the inference of epidemiological parameters from genetic data:

- The hypothetical "true" phylogeny of the spreading pathogen mirrors the transmission network, with branching events closely corresponding to transmission events [1]

- The underlying pathogen population evolved according to a model that links epidemiological and phylogenetic dynamics [1]

In Bayesian phylogenetic frameworks, these models are implemented as "tree priors," providing an expression for the probability of a tree given parameters governing the epidemiological process that generated it [1]. The analysis requires phylogenetic trees with branch lengths corresponding to time units (chronograms), obtained by converting substitutions per site to time units using an evolutionary clock rate [1].

Foundational Models in Phylodynamics

Table 1: Foundational Phylodynamic Models and Their Characteristics

| Model Type | Theoretical Basis | Key Parameters | Epidiological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coalescent | Population genetics - backwards-in-time process | Effective population size (Ne(t)), generation time (g) | Demographic history, population size through time [1] |

| Birth-Death | Epidemiological processes - forward-in-time process | Transmission rate (λ), removal rate (δ), sampling rate (ψ) | Reproductive number (R), growth rates, prevalence [1] |

| Multi-Type Birth-Death | Structured population expansion | Type-specific birth rates (λij,k), migration rates (mij,k), death rates (μi,k) | Migration patterns, spatial spread, between-population dynamics [3] |

The coalescent model originated in population genetics and models how the ancestry of sampled populations relates to their demographic history [1]. Visualized as a genealogy of sampled individuals, internal nodes correspond to times when lineages coalesce into common ancestors, with time starting at the most recent sample and terminating at the most recent common ancestor [1].

The birth-death model takes a forward-in-time approach, modeling transmission (birth) and removal (death) events in an infected population [1]. This model more directly represents epidemiological processes, with parameters that can be directly linked to transmission rates, sampling rates, and recovery rates [1].

For structured populations, the multi-type birth-death model extends the basic framework to account for dynamics across different populations, geographic regions, or pathogen subtypes [3]. This model can quantify migration rates and type-specific parameters essential for understanding spatial spread and between-population dynamics [3].

Phylodynamics in Outbreak Source Attribution

Molecular Source Attribution Approaches

Source attribution refers to methods that reconstruct infectious disease transmission from a specific source, which could be a population, individual, or location [4]. Molecular source attribution uses pathogen molecular characteristics—most often genomic sequences—to reconstruct transmission events [4]. This approach has become increasingly powerful with advances in sequencing technology and computational methods.

Two primary approaches are used in molecular source attribution:

- Microbial subtyping: Infections are categorized into subtypes based on molecular varieties, with source attribution inferred from subtype similarity [4]

- Phylogenetic reconstruction: Genetic sequences are compared to reconstruct phylogenetic trees that approximate transmission history [4]

The resolution of source attribution depends on having sufficient genetic diversity to differentiate transmission pathways without defining so many subtypes that each individual appears unique [4]. Whole genome sequencing has significantly enhanced attribution precision, particularly for bacterial pathogens, by providing maximal discriminatory power [4].

Methodological Frameworks for Source Attribution

Table 2: Methodological Approaches for Geographical Source Inference

| Method Class | Specific Methods | Key Features | Computational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral State Reconstruction | Discrete Trait Analysis (DTA) | Incorporates discrete metadata (e.g., travel history); relatively low computational demand [2] [5] | Less robust to uneven sampling; parameters difficult to interpret epidemiologically [2] |

| Structured Population Models | Structured Coalescent; Multi-Type Birth-Death | Accounts for variable sampling between regions; infers epidemiologically interpretable parameters [2] [5] | Computationally intensive; improved scalability with recent algorithmic advances [3] |

| Phylogeographic Models | Asymmetric migration models; BEAST phylogeography | Reconstructs spatial dispersal from phylogenetic tree topology [2] [5] | Limited scalability for large datasets (>600 sequences) without model optimizations [6] |

Discrete Trait Analysis (DTA) assigns location states to nodes on a phylogeny and can incorporate travel history data in a straightforward manner [2]. However, it doesn't fully accommodate the interdependency of tree shape and migration rates and is sensitive to sampling biases [2].

Structured population models explicitly model migration events and rates at a population level, providing parameters that can be directly compared with epidemiological or mobility data [2]. These models are more robust to variable sampling between regions but are computationally intensive, though recent algorithmic improvements have enhanced their scalability [3].

Recent advances in multi-type birth-death models have addressed previous limitations in numerical stability and computational efficiency, enabling analysis of datasets containing several hundred genetic samples [3]. These improvements are particularly important for structured populations, where quantifying parameters for each subpopulation requires sufficient samples from each group [3].

Comparative Performance of Phylodynamic Methods

Experimental Evidence on Model Performance

Recent studies have systematically evaluated the performance of different phylodynamic methods under various conditions:

- Model misspecification robustness: Simple structured coalescent models can recover migration rates while adjusting for nonlinear epidemiological dynamics, with only small biases observed for sample sizes ≥1000 sequences [6]

- Genetic data requirements: Migration rates can be estimated using alignments equivalent to partial genes (e.g., HIV pol gene) or complete pathogen genomes, with higher migration rates estimated more accurately than lower rates [6]

- Computational scalability: Phylogeographic models in BEAST showed limited scalability for datasets of 600 or more sequences, though recent improvements in birth-death model implementation have dramatically increased analyzable sample sizes [6] [3]

A study evaluating HIV transmission dynamics found that even simplistic representations of complex epidemiological models could still estimate migration rates accurately, depending on the method and sample size used [6]. The research demonstrated that estimation of higher migration rates was more accurate than estimation of lower migration rates, highlighting method-specific sensitivities [6].

Advanced Methodological Innovations

PhyloTune, a recently developed method, accelerates phylogenetic updates using pretrained DNA language models [7]. This approach identifies the taxonomic unit of newly collected sequences and updates corresponding subtrees, significantly reducing computational time compared to complete tree reconstruction [7]. Experimental results demonstrated that:

- For smaller datasets (n=20-40 sequences), updated trees exhibited identical topologies to complete trees

- For larger datasets (n=60-100 sequences), minor topological discrepancies emerged (RF distances: 0.007-0.054)

- Computational time was relatively insensitive to total sequence numbers compared to exponential growth with complete tree reconstruction [7]

Multi-scale phylodynamic agent-based models represent another innovation, integrating within-host pathogen evolution with between-host transmission dynamics in heterogeneous populations [8]. These models can simulate feedback loops between public health interventions and pathogen evolution, capturing phenomena like the punctuated evolution observed in SARS-CoV-2 [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Phylodynamic Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Software | BEAST2 (with bdmm package); RAxML-NG; PhyML | Bayesian phylogenetic inference; maximum likelihood tree estimation | Comprehensive phylodynamic analysis; tree topology estimation [1] [3] [9] |

| Sequence Alignment | MAFFT; BuddySuite | Multiple sequence alignment; genomic data processing | Preprocessing of genomic data for phylogenetic analysis [7] |

| Classification & Annotation | DNABERT; Kraken2; BLAST | Taxonomic classification; sequence similarity identification | Taxonomic unit identification; sequence annotation [7] |

| Language Models | PhyloTune | High-dimensional sequence representation; attention region identification | Efficient phylogenetic updates; informative region extraction [7] |

The BEAST2 software platform with packages like bdmm (birth-death model migration) provides a comprehensive framework for phylodynamic analysis, enabling joint inference of tree topologies, phylodynamic parameters, molecular clock rates, and substitution models [3]. Recent algorithmic improvements to bdmm have dramatically increased the number of genetic samples that can be analyzed while improving numerical robustness and computational efficiency [3].

DNA language models like DNABERT generate high-dimensional sequence representations that can be used for taxonomic classification and identification of phylogenetically informative regions [7]. These models leverage the transformer architecture with self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in genomic sequences, similar to how language models process natural language [7].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Phylodynamic Analysis Pipeline

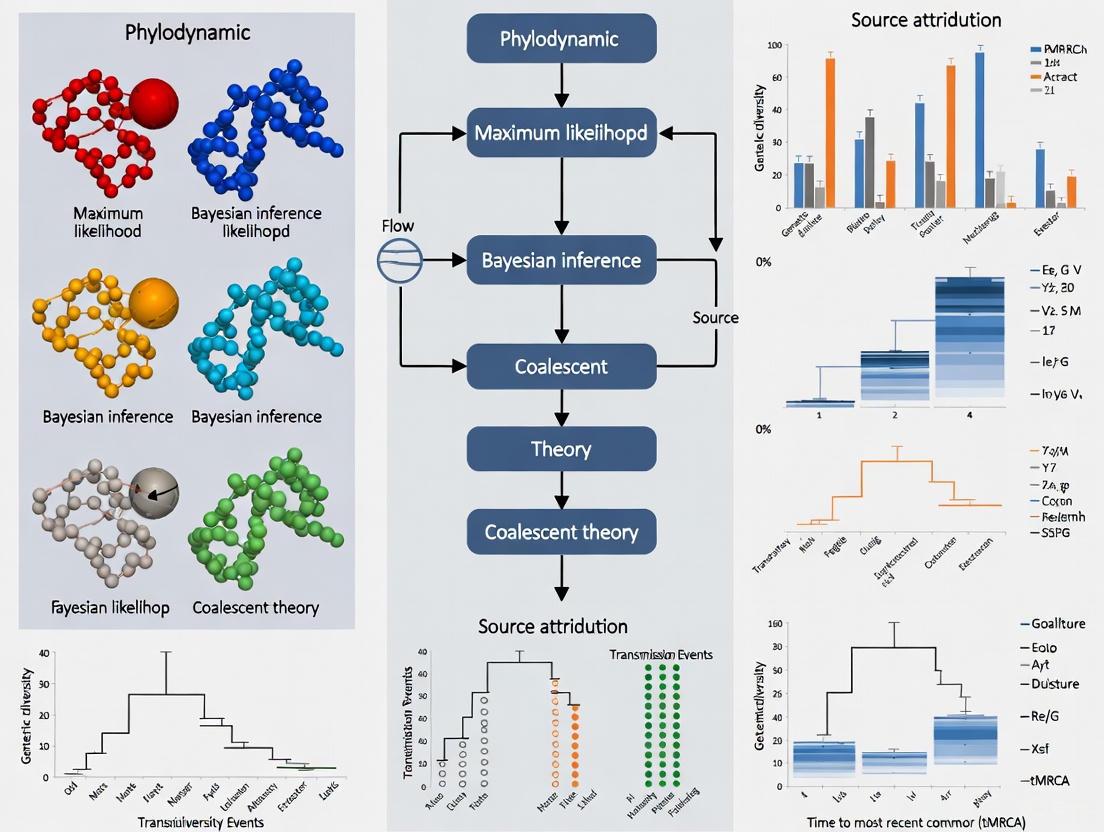

The following workflow diagram illustrates a standard protocol for phylodynamic analysis of outbreak genomic data:

Standard Phylodynamic Analysis Workflow

This workflow was applied in an early SARS-CoV-2 analysis that used 86 genomes to estimate the TMRCA (Most Recent Common Ancestor) and growth rate parameters [9]. Key steps included:

- Sequence quality control: Removal of sequences with sequencing artefacts, insufficient information, or resequencing of the same sample [9]

- Dataset sub-setting: Inclusion of only a single representative genome from known epidemiologically-linked transmission clusters to meet coalescent model assumptions [9]

- Model selection: Comparison of constant size and exponential growth coalescent models, with exponential growth providing better fit to emerging pandemic data [9]

- Parameter estimation: Bayesian MCMC analysis to estimate evolutionary rates, TMRCA, and growth parameters with 95% credible intervals [9]

Source Attribution Experimental Protocol

For outbreak source attribution studies, the following specialized protocol is recommended:

- Genomic data collection: Collect whole genome sequences from outbreak isolates with comprehensive metadata including sampling dates and locations [4] [5]

- Genetic clustering: Apply clustering methods to group similar sequences, balancing resolution power with practical utility [4]

- Phylogeographic analysis: Implement structured birth-death models or discrete trait analysis to infer spatial transmission history [2] [5]

- Statistical validation: Assess confidence in source attribution through bootstrap support or posterior probability values [5]

A key consideration in source attribution is accounting for sampling bias, as uneven sampling across regions can strongly influence phylogeographic inferences [5]. Structured population models generally show better robustness to sampling heterogeneity compared to discrete trait analysis [2].

Phylodynamics has established itself as an essential component of genomic epidemiology, providing powerful methods for reconstructing transmission dynamics and identifying outbreak sources. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that while foundational models like the coalescent and birth-death processes provide the theoretical framework for phylodynamic inference, structured models offer enhanced capabilities for source attribution applications.

Method selection should be guided by specific research questions, data characteristics, and computational constraints. For rapid assessment of well-sampled outbreaks, discrete trait approaches provide efficient inference, while for complex transmission dynamics with uneven sampling, structured birth-death models offer more robust parameter estimation. Recent advances in algorithmic efficiency and multi-scale modeling continue to expand the boundaries of phylodynamic inference, promising even more powerful tools for future outbreak responses.

The integration of phylodynamic methods into public health practice represents a paradigm shift in outbreak epidemiology, enabling researchers to extract profound insights into pathogen spread from genetic sequences. As these methods continue to evolve and improve, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in global infectious disease surveillance and control efforts.

Phylodynamics represents a powerful, integrative framework that combines phylogenetics, epidemiology, and population dynamics to uncover the transmission dynamics of infectious pathogens [10]. The core premise of phylodynamics is that epidemiological processes, such as transmission and population fluctuations, occur on timescales similar to the accumulation of evolutionary changes in pathogen genomes. This synergy leaves a distinct signature in the genetic data, allowing researchers to reconstruct key aspects of an outbreak's history from molecular sequences [10] [11]. Originally applied to rapidly evolving viruses, these methods are now instrumental for outbreak surveillance, enabling estimation of critical parameters like the effective reproduction number (Re), divergence times, and spatial spread patterns from sampled pathogen sequences [12] [13].

The field faces a fundamental challenge: extracting robust, biologically plausible inferences from complex and often limited genetic data [14] [13]. This article provides a comparative guide to modern phylodynamic methods, evaluating their performance, underlying models, and applicability for outbreak source attribution research.

Comparative Analysis of Phylodynamic Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Core Phylodynamic Methodologies

| Method Category | Key Software/Approach | Underlying Model | Primary Applications | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coalescent-Based | BEAST (Bayesian Skyline Plot) [13] [15] | Coalescent | Estimating effective population size (Ne(t)) trajectory, demographic history [14] [10]. | Models genetic diversity; conditions on known sampling times; well-established framework [14]. | Sampling times are fixed inputs; indirect link to epidemiological parameters [14]. |

| Birth-Death Based | BEAST2 (Birth-Death Model) [11] [15] | Birth-Death | Inferring transmission rates (λ), recovery rates (δ), reproductive number (R0), origin time (T) [14]. | Directly models transmission and sampling as stochastic processes; jointly infers tree and sampling times [14]. | Prior specification highly influences results with limited data; computationally intensive [14] [11]. |

| Deep Learning / Simulation-Based | PhyloDeep [11] | Birth-Death variants (BD, BDEI, BDSS) | Fast parameter estimation and model selection from large phylogenies [11]. | Extremely fast on large trees; avoids complex likelihood calculations; good accuracy [11]. | Requires extensive training with simulated data; "black box" inference process [11]. |

| Joint Inference Frameworks | EpiFusion [12] | Particle Filtering | Joint inference using both phylogenetic trees and case incidence data [12]. | Combines strengths of different data types (genetic and epidemiological) for robustness [12]. | Increased model complexity; requires multiple data streams [12]. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Simulated and Real Data

| Method / Software | Computational Speed | Scalability to Large Trees (>1000 tips) | Accuracy on Simulated Data (vs. Known Truth) | Robustness to Prior Specification | Real-World Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 (Coalescent) | Slow [11] | Limited [11] | High when temporal signal is strong and priors are appropriate [14] | Low to Moderate (posteriors can be highly prior-dependent with limited data) [14] [13] | HIV epidemic dynamics in the UK [10] |

| BEAST2 (Birth-Death) | Slow [11] | Limited [11] | Can be biased if model misspecified or with reporting delays [14] [15] | Low (high sensitivity to tree prior choices in early outbreaks) [14] | Zika virus epidemic in the Americas [14] |

| PhyloDeep (FFNN-SS) | Fast (seconds to minutes) [11] | High [11] | Better than BEAST2 on complex models (BDEI, BDSS) [11] | High (trained on wide parameter ranges, less dependent on user priors) [11] | HIV superspreading dynamics in Zurich [11] |

| PhyloDeep (CBLV-CNN) | Fast (seconds to minutes) [11] | High [11] | State-of-the-art on tested models; outperforms BEAST2 and FFNN-SS [11] | High (same as FFNN-SS) [11] | HIV superspreading dynamics in Zurich [11] |

Experimental Protocols in Phylodynamic Analysis

A robust phylodynamic analysis requires a carefully constructed pipeline to ensure reliable and biologically plausible inferences. The following workflow, adapted from foundational sources, outlines the critical steps and decision points [13] [11].

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Sequence Preparation and Curation: The initial phase involves rigorous sequence collection, alignment, and curation. For reliable inference, the dataset must be temporally and spatially representative of the outbreak. Researchers must decide whether to analyze all available sequences or focus on specific monophyletic lineages, a choice that can significantly impact results [13]. Tools like the Recombination Detection Program (RDP) are often used to identify and remove recombinant sequences that violate phylogenetic assumptions [13].

Evolutionary Model Selection: This critical step assesses the temporal signal in the data using tools like TempEst to determine if sampling dates can calibrate the molecular clock. Subsequently, statistical comparison (e.g., using Bayesian Information Criterion - BIC) selects the best-fitting nucleotide substitution model (e.g., HKY or GTR) [13]. A strict vs. relaxed molecular clock model is also chosen based on data characteristics [13].

Tree Prior Selection and Robustness Testing: The choice between Coalescent and Birth-Death tree priors is fundamental. As demonstrated in Zika virus studies, estimates of the reproductive number and tree height can be highly sensitive to this choice, especially with limited data [14]. A robustness check, scanning different models and prior distributions, is mandatory. Only estimates robust to reasonable prior changes should be trusted for policy decisions [14] [13].

Accounting for Real-World Biases: Modern extensions address common surveillance biases. For instance, reporting delays between sample collection and sequence deposition can severely bias real-time estimates of effective population size. New models incorporate reporting delay distributions to mitigate this effect, providing more reliable estimates closer to the present time [15]. Furthermore, preferential sampling models account for situations where sampling intensity is correlated with disease prevalence [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for Phylodynamic Research

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST / BEAST2 [13] [10] [15] | Software Package | Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. | Implements coalescent and birth-death models; integrates sequence evolution with demographic/epidemiological models; gold standard for many applications. |

| PhyloDeep [11] | Software Package | Fast parameter estimation and model selection using deep learning. | Uses neural networks on tree summaries (SS) or compact vector representations (CBLV); handles large trees efficiently. |

| EpiFusion [12] | Analysis Framework | Joint inference from phylogenetic and case incidence data. | Uses particle filtering; implemented in R and Java; improves estimation of the effective reproduction number. |

| Birth-Death Prior | Model | Tree prior for phylodynamic inference. | Models transmission (λ), becoming non-infectious (δ), sampling (ρ), and origin time; infers trees and sampling times jointly [14]. |

| Coalescent Prior | Model | Tree prior for phylodynamic inference. | Models effective population size (Ne); conditions on fixed sampling times; infers population size changes from genetic data [14]. |

| Bayesian Skyline Plot [15] | Model | Non-parametric estimation of population size. | Infers changes in effective population size (Ne(t)) over time; implemented in BEAST. |

| Compact Bijective Ladderized Vector (CBLV) [11] | Data Representation | A bijective, compact vector representation of a phylogenetic tree. | Preserves all tree information (topology & branch lengths); enables use of convolutional neural networks (CNN) for analysis. |

Conceptual Framework of Phylodynamic Models

The statistical foundation of Bayesian phylodynamics involves inferring the joint posterior distribution of the phylogenetic tree and model parameters given the sequence data and other relevant information [14]. This can be represented as: P(Tree, Parameters | Sequence Data, Other Data) ∝ P(Sequence Data | Tree, Parameters) × P(Tree, Other Data | Parameters) × P(Parameters) Here, the phylogenetic likelihood P(Sequence Data | Tree, Parameters) is determined by the evolutionary substitution model, while the phylodynamic likelihood P(Tree, Other Data | Parameters) is specified by the population dynamic model (e.g., Birth-Death or Coalescent) [14].

The diagram illustrates the core phylodynamic inference loop. The true, unobserved transmission process in the host population drives the evolution of the pathogen. Sampled sequences are used to infer a phylogenetic tree, which serves as the input for statistical models (e.g., Birth-Death or Coalescent). These models reverse-engineer the process to estimate the underlying transmission dynamics, such as the effective population size Ne(t) or the time-varying reproductive number R(t).

The Importance of Source Attribution in Public Health Response

Source attribution is a critical discipline in epidemiology that reconstructs the transmission of infectious diseases from specific sources—such as animal reservoirs, food products, or infected individuals—to humans [16] [17]. By quantifying the contributions of different sources to the human disease burden, it enables public health officials to prioritize interventions, measure their impact, and allocate resources efficiently [17] [18]. This guide compares the primary methodological approaches for source attribution, focusing on the growing role of phylodynamic methods which integrate phylogenetic analysis of pathogen genomes with models of disease dynamics.

Methodological Comparison of Source Attribution Approaches

Multiple methodologies exist for attributing the source of infections, each with distinct data requirements, applications, and strengths [17] [18]. The choice of method depends on the research question, the point in the farm-to-fork continuum one wishes to attribute, and, crucially, the availability and quality of data [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Source Attribution Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Point of Attribution | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Subtyping (e.g., Frequency-Matching Models) [19] [17] | Compares the distribution of pathogen subtypes (e.g., serotypes, sequence types) in human cases with their distribution in potential animal or food sources. | Primarily the point of production (animal reservoir) [19]. | Well-established with a strong track record for pathogens like Salmonella; provides quantitative estimates of source contributions [17] [18]. | Requires representative, strain-typed isolates from all major sources; subtypes must be stable across the farm-to-fork continuum [18]. |

| Population Genetics Models (e.g., STRUCTURE) [18] | Uses genetic data to assess the genealogical history and evolutionary relationships among strains, assigning human cases to the genetically closest source. | Point of production (animal reservoir). | Can attribute cases even when perfect subtype matches are absent; accounts for pathogen evolution [18]. | Requires high-resolution genetic data; the panel of potential sources must be complete to avoid misattribution [18]. |

| Analysis of Outbreak Data [17] | Attributes cases based on the investigation of foodborne outbreaks where the source is identified. | Point of exposure (specific food vehicle). | Directly uses public health investigation data; no need for complex modeling. | Limited to outbreaks; results may not be representative of sporadic cases, which constitute the majority of illnesses [17]. |

| Case-Control Studies of Sporadic Cases [18] | Compares the exposures of infected individuals (cases) with those of uninfected controls to identify risk factors. | Point of exposure (specific food, contact, etc.). | Identifies risk factors and specific exposure routes for sporadic cases. | Susceptible to recall and selection biases; cannot attribute cases to specific animal reservoirs directly [18]. |

| Phylodynamic Methods [20] [21] | Reconstructs transmission trees and estimates epidemiological parameters by combining pathogen genome sequences with epidemiological and disease dynamic models. | Can infer transmission between individuals, populations, or locations. | Provides a unified framework for evolutionary and epidemiological inference; can identify direct transmission links and estimate key parameters like the reproductive number (R) [14] [21]. | Computationally intensive; requires sequence data and can be sensitive to model specification and prior choices [14]. |

| Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) [18] | A "bottom-up" approach that models the transmission pathway from source to human, incorporating data on contamination levels, food consumption, and dose-response. | Any point in the food chain (production, processing, consumption). | Can model the impact of interventions at different stages of the food production chain. | Data-intensive; requires detailed information on the entire farm-to-fork continuum [18]. |

Experimental Data: Phylodynamic Inference in Practice

Phylodynamic models are not just theoretical constructs; they are routinely applied to real-world outbreak data to infer transmission patterns. The following table summarizes results and protocols from key studies that employed phylodynamic methods for source attribution.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Phylodynamic Source Attribution Studies

| Pathogen / Context | Core Objective | Method & Model Used | Key Findings & Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Netherlands [20] | To determine Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) cut-offs for identifying probable transmission clusters using a phylodynamic model as a reference instead of contact tracing. | Model: phybreakData: 2,008 whole-genome sequences from TB patients (2015-2019).Protocol: Genetic clusters were first defined (≤20 SNP distance). phybreak was then run on each cluster to infer transmission events, which were used to assess the performance of various SNP cut-offs. |

A SNP cut-off of 4 captured 98% of model-inferred transmission events. A cut-off beyond 12 SNPs effectively excluded transmission. The study demonstrated that phylodynamics provides a valuable alternative to often unreliable contact tracing for defining genetic thresholds [20]. |

| Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) in U.S. swine systems [21] | To infer the spread and population history of a specific PRRSV strain (RFLP 1-7-4) among five production systems. | Model: Coalescent and discrete-trait phylodynamic models in a Bayesian statistical framework.Data: 288 ORF5 gene sequences with metadata on farm system and type.Protocol: The best-fit nucleotide substitution model was selected. Models were used to infer demographic history and the ancestral system with root state posterior probability, and significant dispersal routes were identified using Bayes Factors (>6). | Identified the most likely ancestral production system (root state posterior probability = 0.95). Revealed that sow farms were central to viral spread within the systems. Showed that currently circulating viruses are evolving rapidly and have higher relative genetic diversity than earlier relatives [21]. |

| Zika Virus epidemic in the Americas [14] | To assess how model choices (tree priors) influence the estimation of key parameters like the reproductive number (R) and tree height during an emerging epidemic. | Model: Comparison of Birth-Death and Coalescent tree priors in BEAST 2.Data: Zika virus genome sequences from Brazil and Florida, USA.Protocol: Analyses were run with different tree priors and prior distributions on parameters to test the robustness of estimates. | Parameter estimates were not robust for smaller, local epidemics (Brazil and Florida), highlighting that data may be uninformative early in an outbreak. Emphasizes the critical need for robustness checks by scanning models and priors; estimates can only be trusted if the posterior is robust to reasonable prior changes [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SNP Cut-off Assessment forM. tuberculosis

The following workflow details the methodology from the tuberculosis study cited in Table 2 [20]:

Data Preparation & Cluster Formation:

- Sequencing & Alignment: Whole-genome sequences are obtained from bacterial isolates and aligned to a reference genome (e.g., H37Rv for TB).

- SNP Calling & Filtering: A genotypes matrix is created from variant calls, filtering out sites in mobile genetic elements and those with low quality or high levels of missing data.

- Transitive Clustering: Using a package like

adegenetin R, sequences are clustered into genetic groups where each sequence is within a defined SNP distance (e.g., 20 SNPs) of at least one other sequence in the cluster. This large initial cut-off ensures all potentially linked cases are grouped.

Phylodynamic Inference:

- Model Application: For each genetic cluster of sufficient size, a phylodynamic model (e.g.,

phybreak) is run. This model uses the sequences and their collection dates to infer a posterior distribution of possible transmission trees. - Parameter Estimation: The model co-infers transmission events, the mutation rate of the pathogen, and other epidemiological parameters.

- Model Application: For each genetic cluster of sufficient size, a phylodynamic model (e.g.,

Validation & Cut-off Assessment:

- Reference Definition: The transmission events inferred by

phybreakare used as the "reference standard" for determining which case pairs constitute a transmission link. - Performance Calculation: For a range of SNP cut-offs (e.g., 0 to 15), the proportion of model-inferred transmission pairs that fall at or below that cut-off is calculated. This identifies the SNP threshold that best captures true transmission events while minimizing false positives.

- Reference Definition: The transmission events inferred by

Workflow for Phylodynamic SNP Cut-off Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successfully implementing phylodynamic and source attribution studies requires a suite of specialized tools, software, and data.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Phylodynamic Source Attribution

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST 2 [14] | Software Package | A cross-platform Bayesian evolutionary analysis software for inferring evolutionary history and population dynamics from genetic data. | Used to co-infer phylogenetic trees and epidemiological parameters using coalescent or birth-death tree priors [14]. |

| EpiFusion [22] | Software Framework | A Java-based model for joint inference of outbreak characteristics using both phylogenetic trees and case incidence data via particle filtering. | Infers infection trajectories and the effective reproduction number (R~t~) by combining case data and a phylogenetic tree posterior [22]. |

| phybreak [20] | R Package/Model | A phylodynamic method to infer transmission events from outbreak data (genomes and sampling times) without imputing many unobserved cases. | Used to infer transmission chains of M. tuberculosis in a low-incidence setting to validate SNP cut-offs [20]. |

| Structured Coalescent Model [6] | Mathematical Model | A phylodynamic model that estimates migration rates between populations (e.g., geographic regions or host groups) while adjusting for epidemiological dynamics. | Applied to HIV sequence data to estimate migration rates between populations, showing scalability for large datasets (≥1000 sequences) [6]. |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [20] | Laboratory & Data | Provides the highest resolution data by sequencing the entire pathogen genome, enabling precise strain discrimination and detailed phylogenetic analysis. | The foundation for calling SNPs and building high-resolution phylogenies for M. tuberculosis transmission studies [20]. |

| Reporting Delay Model [15] | Statistical Model | A method that incorporates the distribution of times between sample collection and sequence reporting to correct biases in real-time phylodynamic analyses. | Improves the accuracy of effective population size estimates for SARS-CoV-2 near the present time by accounting for missing data [15]. |

Critical Considerations and Future Directions

While powerful, phylodynamic methods require careful implementation. A major consideration is model specification and robustness [14]. Choices regarding the tree prior (e.g., coalescent vs. birth-death) and parameter priors can significantly influence results, especially with limited or early-outbreak data. Researchers must perform robustness checks to ensure estimates are reliable [14]. Furthermore, model misspecification can introduce inductive bias, though for large sample sizes (e.g., ≥1000 sequences), this bias may be small [6].

The future of source attribution lies in data integration. Frameworks like EpiFusion, which jointly model phylogenetic trees and case incidence data, represent a move toward synthesizing all available data streams for a more complete and reliable picture of outbreak dynamics [22]. As whole-genome sequencing becomes standard, methods that leverage its full potential while accounting for real-world complexities like reporting delays will be indispensable for precise and timely public health response [15] [18].

The field of infectious disease dynamics has been transformed by the integration of two powerful data streams: classical epidemiological information and pathogen genomic sequences. This integration, formalized through phylodynamic methods, enables researchers to infer transmission patterns, identify outbreak sources, and reconstruct the evolutionary history of pathogens. Phylodynamics combines evolutionary models from molecular phylogenetics with epidemiological models from population dynamics to create a unified framework for analyzing infectious disease spread [23]. This approach has been applied to diverse pathogens including HIV, influenza, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and SARS-CoV-2, providing crucial insights for public health interventions [6] [20] [23].

The core premise of this framework is that pathogen genomes accumulate mutations over time, and the relationships between these genetic sequences contain valuable information about the timing and spread of infections. When combined with epidemiological data such as symptom onset dates, contact networks, and geographic locations, these molecular sequences enable powerful inferences about transmission dynamics that neither data type could provide alone. This article compares the leading phylodynamic methods and provides a conceptual framework for their application in outbreak source attribution research.

Comparative Analysis of Phylodynamic Methods

Methodological Approaches and Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Phylodynamic Methods and Applications

| Method | Primary Application | Data Requirements | Key Outputs | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured Coalescent Models | Estimating migration rates between populations [6] | Genetic sequences, population structure | Migration rates, effective population sizes | Can adjust for nonlinear epidemiological dynamics [6] | Potential inductive bias with model misspecification [6] |

| Agent-Based Models (PhASE TraCE) | Multi-scale pandemic modeling with rapid variant emergence [8] | Genomic surveillance, demographic, mobility data | Transmission chains, variant emergence patterns, intervention impacts | Captures feedback between evolution, interventions, and behavior [8] | Computational intensity with large populations [8] |

| Bayesian Birth-Death Models | Cluster-based transmission rate estimation [24] | Time-stamped sequences, epidemiological priors | Transmission rates, reproductive numbers, cluster influence | Quantifies uncertainty in parameter estimates [24] | Influence varies with cluster size and rate heterogeneity [24] |

| Phylogenetic Network Methods | Lateral spread inference in outbreaks [25] | Whole genomes, epidemiological contact data | Genetic networks, transmission links, diffusion routes | Integrates multiple transmission drivers simultaneously [25] | Dependent on quality of epidemiological metadata [25] |

| Transmission Tree Inference (phybreak) | SNP cut-off determination for transmission clusters [20] | WGS data, serial interval distributions | Transmission probabilities, SNP thresholds | Provides biological reference without contact tracing [20] | Assumes uniform generation time distributions [20] |

Performance and Operational Characteristics

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Computational Tools

| Tool/Method | Computational Efficiency | Scalability | Statistical Power | Implementation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HyPhy | 30 minutes for 1,776 sequences [26] | High | 61.4% sequences clustered [26] | Patristic distance ≤2% threshold [26] |

| MEGA | 324 hours for 1,776 sequences [26] | Moderate | 33.7% sequences clustered [26] | Patristic distance ≤1.5% threshold [26] |

| BEAST Phylogeography | Not scalable for ≥600 sequences [6] | Low | Accurate migration rates with simple models [6] | Complex model specification [6] |

| Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGM) | Moderate | High for network inference | Identifies significant transmission drivers [25] | Genetic networks, epidemiological covariates [25] |

| Agent-Based Models | Variable with population size | Scalable with computational resources | Replicates complex multi-scale dynamics [8] | High-resolution genomic and mobility data [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Phylodynamic Analysis

Protocol 1: Molecular Transmission Cluster Analysis

Objective: Identify recent transmission clusters using genetic sequence data to guide public health interventions.

Methodology:

- Sequence Preparation: Align viral sequences (e.g., HIV pol gene) using MAFFT v7 or equivalent tool [25] [26].

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Build maximum likelihood trees using IQ-TREE v1.6.6 with 1000 bootstrap replicates [25].

- Genetic Distance Calculation: Compute patristic distances (evolutionary distance along tree branches) between all sequence pairs [26].

- Cluster Identification: Apply distance thresholds (≤1.5% for MEGA, ≤2% for HyPhy) to define transmission clusters [26].

- Validation: Compare cluster composition with epidemiological data to validate transmission links.

Key Parameters:

- Genetic distance thresholds optimized for specific pathogens and epidemiological contexts

- Bootstrap support >70% for cluster stability

- Temporal signal assessment through root-to-tip regression

Protocol 2: Integrated Genomic-Epidemiological Network Analysis

Objective: Identify factors driving viral spread during outbreaks using combined genomic and epidemiological data.

Methodology:

- Genetic Network Construction: Generate median-joining networks from concatenated gene segments using NETWORK 10.2.0.0 [25].

- Epidemiological Covariate Preparation:

- Calculate geographic distances between cases

- Determine risk window overlaps (periods of potential infectiousness and susceptibility)

- Record production system relationships (same owners, poultry companies) [25]

- Model Implementation: Apply Exponential Random Graph Models (ERGM) to assess the effect of covariates on genetic link probability [25].

- Interpretation: Identify significant drivers (e.g., same poultry company Est. = 0.548, risk windows overlap Est. = 0.339) [25].

Key Parameters:

- Genetic difference threshold for link definition

- Confidence intervals for covariate effect estimates

- Model goodness-of-fit assessment

Protocol 3: Transmission SNP Threshold Determination

Objective: Establish evidence-based SNP cut-offs for defining transmission clusters using phylodynamic inference.

Methodology:

- Genetic Clustering: Perform transitive clustering with initial 20-SNP threshold to define candidate transmission clusters [20].

- Transmission Inference: Apply phybreak method to infer transmission events within clusters using WGS data and serial interval distributions [20].

- SNP Distance Analysis: Calculate proportion of inferred transmission events below various SNP cut-offs (e.g., 3-12 SNPs) [20].

- Threshold Selection: Identify optimal SNP cut-off that captures majority of transmission events (e.g., 4 SNPs captured 98% of transmissions in TB study) while minimizing false positives [20].

Key Parameters:

- Mutation rate calibration for specific pathogens

- Serial interval distribution parameters

- Sampling density considerations

Conceptual Framework and Workflows

Integrated Phylodynamic Analysis Framework

Method Selection Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Alignment | MAFFT v7 [25] | Multiple sequence alignment | Preprocessing of genomic data for phylogenetic analysis |

| Phylogenetic Reconstruction | IQ-TREE v1.6.6 [25] | Maximum likelihood tree building | Inferring evolutionary relationships from genetic sequences |

| Phylodynamic Inference | BEAST [6] | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Estimating evolutionary parameters and population dynamics |

| Transmission Cluster Analysis | HyPhy [26] | Hypothesis testing using phylogenetics | Identifying molecular transmission clusters |

| Transmission Tree Inference | phybreak [20] | Transmission network reconstruction | Inferring who-infected-whom from genomic data |

| Network Analysis | NETWORK 10.2.0.0 [25] | Median-joining network construction | Visualizing genetic relationships between closely related sequences |

| Statistical Analysis | R Software [25] | Data analysis and visualization | Implementing ERGM and other statistical models |

| Molecular Evolution | MEGA [26] | Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis | Comparative analysis of genetic sequences |

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of epidemiological and evolutionary data represents a paradigm shift in outbreak investigation and source attribution. Our comparative analysis demonstrates that method selection should be guided by specific research questions, data availability, and computational resources. For rapid assessment of transmission clusters, HyPhy offers significant advantages in computational efficiency and clustering sensitivity compared to MEGA [26]. For complex outbreaks with heterogeneous transmission, Bayesian birth-death models provide robust inference but require careful consideration of cluster influence and sample size effects [24].

A critical insight from our analysis is that model misspecification can introduce inductive biases, particularly when simple models are applied to complex transmission systems [6]. However, structured coalescent models can still recover accurate migration rates despite some simplification of epidemiological dynamics [6]. For large-scale pandemic modeling with rapid variant emergence, multi-scale agent-based approaches like PhASE TraCE offer the unique advantage of capturing feedback between evolutionary dynamics, intervention policies, and human behavior [8].

Future methodological development should address several key challenges: improving computational scalability for large genomic datasets, developing standardized approaches for integrating heterogeneous data sources, and creating robust methods for real-time phylodynamic inference during ongoing outbreaks. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and genomic surveillance becomes more routine, the conceptual framework presented here will serve as a foundation for the next generation of phylodynamic tools in public health practice.

A Landscape of Phylodynamic Methods: From Theory to Real-World Application

Bayesian phylogeographic models have emerged as a powerful statistical framework for reconstructing the spatiotemporal spread and evolution of pathogens. These methods combine molecular sequence data with epidemiological, geographic, and temporal information to infer patterns of pathogen dispersal across landscapes. The foundational principle underpinning these approaches is that evolutionary relationships inferred from genetic sequences, when calibrated in time, contain valuable information about the demographic history and spatial dynamics of pathogen populations [10]. In the context of infectious disease outbreaks, this enables researchers to address critical questions about origin estimation, the number of independent introductions, rates of spread between locations, and the impact of interventions.

The field represents a synthesis of evolutionary biology, epidemiology, and spatial statistics. Phylogeography specifically models how discrete or continuous traits, such as geographic location, evolve along the branches of a time-scaled phylogenetic tree [27] [10]. When these models are applied within a Bayesian statistical framework, they naturally quantify uncertainty in parameter estimates—including tree topology, divergence times, and evolutionary rates—providing a posterior distribution of possible scenarios consistent with the observed data [28]. The integration of such models with epidemic birth-dedeath processes has given rise to the subfield of phylodynamics, which aims to understand the interaction of evolutionary and ecological processes shaping pathogen populations [10].

For outbreak source attribution research, a key quantity of interest is often the root state of the inferred phylogeny, which represents the geographic origin of the sampled outbreak [27]. The performance of different models in accurately identifying this root state, and the factors affecting this performance, forms a critical basis for comparison. The following sections provide a comparative analysis of leading software packages, their underlying models, performance characteristics, and experimental protocols for evaluating their accuracy in outbreak source attribution.

Comparative Analysis of Software Platforms

Multiple software platforms implement Bayesian phylogeographic inference, each with distinct strengths, model offerings, and computational characteristics. The table below provides a structured comparison of three prominent tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Bayesian Phylogeographic Software Platforms

| Software | Core Strengths | Primary Phylogeographic Models | Key Innovations | Performance & Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEAST X [29] | Integrated Bayesian inference, rich model library, active community development. | Discrete-trait CTMC, Relaxed Random Walk (RRW), Structured Birth-Death. | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) samplers; models for sampling bias; missing data integration. | HMC samplers provide ~5x faster convergence for skygrid models; efficient for large datasets [29]. |

| MTML-msBayes [30] | Hierarchical Approximate Bayesian Computation (HABC) for multi-taxon, multi-locus comparative phylogeography. | Multi-taxon coalescent model with divergence and migration. | Hyper-parameters to quantify variability in divergence times across taxon-pairs. | Computationally efficient for complex multi-taxon models via ABC, but accuracy depends on summary statistics. |

| EpiFusion [22] | Joint inference from phylogenetic trees and case incidence data via particle filtering. | Particle MCMC integrating incidence data and tree(s). | "Single process model, dual observation model" particle filter. | Fits force of infection via particle filter; other parameters via MCMC; suitable for outbreak-scale analysis. |

BEAST X represents the state-of-the-art, introducing significant advances in flexibility and scalability. Its novel shrinkage-based local clock model offers a more tractable and interpretable alternative to the classic random local clock, while new preorder tree traversal algorithms enable linear-time gradient evaluations for high-dimensional parameters [29]. This computational efficiency allows BEAST X to handle the large genomic datasets now common in pathogen research.

MTML-msBayes serves a specific niche in comparative phylogeography. Instead of focusing on a single pathogen, it uses Hierarchical Approximate Bayesian Computation (HABC) to infer patterns of divergence and gene flow across multiple codistributed species or populations (taxon-pairs) [30]. This is particularly useful for identifying common biogeographic histories.

EpiFusion takes a different approach by formally integrating two key data sources: phylogenetic trees and case incidence data. Its particle filtering framework is designed to infer the effective reproduction number (R_t) and infection trajectories by evaluating simulated outbreaks against both types of data [22]. This joint inference can provide a more robust understanding of outbreak characteristics.

Performance in Source Attribution and Key Findings

Evaluating the performance of Bayesian phylogeographic models, particularly their accuracy in root state classification (source attribution), is crucial for applied public health. Simulation studies have revealed how model performance is influenced by data set characteristics.

Table 2: Key Factors Influencing Root State Classification Accuracy

| Factor | Impact on Root State Classification | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Data Set Size | Performance is highest at intermediate sequence data set sizes; very small datasets lack signal, while very large datasets can introduce complex model fit challenges [27]. | Simulation studies measuring classification accuracy across a range of dataset sizes (10s to 1000s of sequences) [27]. |

| Discrete State Space Size | As the number of possible discrete locations (state space) increases, the difficulty of the classification task also increases, requiring more data for the same level of accuracy [27]. | Logistic regression modeling of accuracy against state space size (e.g., from 2 to 56 discrete states) [27]. |

| Sampling Bias & Metadata Uncertainty | Models are sensitive to geographic sampling bias. Missing or uncertain location metadata for sequences can significantly impact inference if not properly accounted for [27] [29]. | Development of the Uncertain Trait Model (UTM) to incorporate sampling probability mass functions (PMFs) for tips with missing data [27]. |

| Model Parameterization | Incorporating prior epidemiological information and using advanced spatial models (e.g., RRW) can improve accuracy by better reflecting realistic spread processes [29]. | Comparison of discrete trait analysis (DTA) vs. structured birth-death models; continuous phylogeography with biased priors [29] [2]. |

A critical insight from systematic evaluations is that a common model evaluation metric, the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, tends to increase with both larger state spaces and larger data set sizes. However, statistical modeling has shown that KL divergence is not a reliable predictor of root state classification accuracy [27]. This indicates that relying solely on KL divergence for model selection can be misleading, potentially favoring models with artificially inflated support.

The Uncertain Trait Model (UTM) provides a coherent method for incorporating sequences with missing or uncertain location metadata. Instead of discarding such sequences, UTM allows the researcher to specify a prior probability mass function over possible states. Studies show that an "informed" UTM prior (where most mass is on the correct trait) can improve inference, while a "misspecified" prior can harm it, highlighting the importance of careful prior specification [27].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Robust validation of phylogeographic models relies on simulation-based approaches where the "true" history is known, allowing for direct assessment of inference accuracy. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for such performance evaluation.

Well-Calibrated Simulation Study

A well-calibrated simulation study tests whether the software implementation can accurately recover known parameters across repeated analyses [28]. The specific protocol is as follows:

- Parameter and Tree Simulation: From a specified Bayesian model (e.g., containing an HKY substitution model, uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock, and a Yule tree prior), randomly draw 100 or more independent sets of parameters (e.g., base frequencies, transition-transversion ratio, birth rate) and corresponding time-scaled phylogenetic trees [28].

- Sequence Alignment Simulation: For each parameter set and tree, simulate a nucleotide sequence alignment using a phylogenetic continuous-time Markov chain. This represents the evolutionary process along the branches of the tree.

- Phylogeographic Inference: Using only the simulated sequences and their sampling times (and associated discrete traits for phylogeography), perform full Bayesian phylogeographic inference with the software and model being tested.

- Validation: Compare the posterior estimates of parameters and the root state to the true values used in the simulation. A well-calibrated model should contain the true value within the 95% Highest Posterior Density (HPD) interval approximately 95% of the time [28].

Performance Benchmarking

To compare computational efficiency and sampling performance between different software or operators, the following protocol is used:

- Data Sets: Run analyses on a range of datasets, from small to large (e.g., 50 to 500 taxa).

- MCMC Execution: Perform MCMC sampling for a fixed number of steps or until convergence is achieved.

- Metrics Calculation: Calculate the Effective Sample Size (ESS) for each key parameter, which estimates the number of independent samples from the posterior. Also record the total computer running time.

- Efficiency Comparison: The primary metric for comparison is the ESS per hour. An operator or software that yields a higher ESS per hour for the same level of accuracy is considered more efficient [28]. For example, the "Constant Distance" operator developed for BEAST 2 was shown to improve overall mixing efficiency by up to half an order of magnitude for large data sets [28].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Implementing Bayesian phylogeographic analyses requires a suite of software tools and research reagents. The table below details essential components for a standard workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Bayesian Phylogeography

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Inference Software | BEAST X [29], BEAST 2 [28], MTML-msBayes [30], EpiFusion [22] | Core platforms for performing Bayesian MCMC or ABC inference of phylogenetic trees, evolutionary parameters, and trait diffusion. |

| High-Performance Computing Library | BEAGLE [28] [29] | A software library that uses parallel processing (CPUs/GPUs) to drastically accelerate likelihood calculations, which are the computational bottleneck in phylogenetic inference. |

| Result Analysis & Visualization | Tracer [28], FigTree, R packages (ape, ggtree, EpiFusionUtilities [22]) | Used to diagnose MCMC convergence (ESS), summarize posterior distributions of parameters and trees, and visualize phylogenetic trees with annotated traits. |

| Sequence Data & Management | GenBank, GISAID, PANGOLIN | Public repositories for obtaining sequence data with metadata. Tools for lineage assignment and preliminary analysis. |

| Uncertain Trait Pipelines | Geographic Location Resolution Pipelines [27] | Bioinformatic tools that output probability mass functions (PMFs) for the location of infected host (LOIH) for sequences with missing metadata, for use with the Uncertain Trait Model. |

The relationship between these tools in a standard phylogeographic analysis is visualized below.

Bayesian phylogeographic models are indispensable tools for outbreak source attribution research. The choice of software and model—whether it is the comprehensive and scalable BEAST X, the comparative MTML-msBayes, or the data-integrating EpiFusion—should be guided by the specific research question, the nature and scale of the data, and computational constraints. Performance validation studies consistently show that accuracy is highest at intermediate data set sizes and is challenged by large discrete state spaces and sampling bias. The adoption of modern techniques like the Uncertain Trait Model, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo samplers, and models that correct for sampling bias is critical for generating robust, actionable insights for public health intervention. As the field evolves, continued rigorous evaluation of model performance under realistic conditions will ensure these powerful methods remain reliable guides for understanding and combating infectious disease outbreaks.

Phylodynamics integrates epidemiological and genetic data to reconstruct the transmission dynamics of infectious diseases, a capability that is crucial for effective outbreak management. Two mathematical frameworks form the cornerstone of modern phylodynamic inference: the birth-death model and the coalescent model. Each provides a distinct method for relating the phylogenetic tree of pathogen samples to the underlying population processes. The birth-death model is a forward-time process that describes the transmission (birth) and removal (death) of infected individuals, from which the observed phylogeny is a subsample. In contrast, the coalescent model is a backward-time process that starts with the sampled individuals and traces their lineages backward in time until they merge (coalesce) into common ancestors. While often used interchangeably in some studies, these models operate under fundamentally different assumptions about population dynamics and sampling, which directly impacts their performance in estimating key epidemiological parameters such as migration rates, growth rates, and the basic reproductive ratio ( [31] [32]). The choice between these models is not merely academic; it significantly influences the accuracy and reliability of the epidemiological insights gained, particularly in outbreak source attribution research. This guide provides a structured, data-driven comparison to inform this critical methodological choice.

Performance Comparison: Key Quantitative Findings

Direct comparative studies reveal that the performance of birth-death and coalescent models is highly dependent on the epidemiological context, specifically whether the disease is in an early epidemic growth phase or a stable endemic state.

Table 1: Model Performance Across Epidemiological Scenarios

| Epidemiological Scenario | Performance Metric | Birth-Death Model | Coalescent Model | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemic Outbreak | Accuracy of Migration Rate | Superior (accurate across migration rates) [32] | Less accurate [32] | Birth-death model better accounts for population dynamics [32]. |

| Coverage of Growth Rate (HPD Interval) | Higher Coverage (2-13% error rate) [31] | Lower Coverage (31-75% error rate) [31] | Coalescent's deterministic population assumption is problematic in early outbreaks [31]. | |

| Endemic Disease | Accuracy & Precision of Migration Rate | Comparable Accuracy [32] | Comparable Accuracy, Higher Precision [32] | Both models perform well; coalescent may yield more precise estimates [32]. |

| Source Location Identification | Accuracy | Comparable [32] | Comparable [32] | Both models similarly estimate the source of the disease [32]. |

Performance in Epidemic Outbreaks

For epidemic outbreaks characterized by exponential growth, the birth-death model demonstrates a clear advantage. A simulation study found it exhibits a superior ability to retrieve accurate migration rates regardless of the actual migration rate, whereas the structured coalescent model with a constant population size can lead to inaccurate estimates [32]. Furthermore, when estimating the epidemic growth rate from phylogenetic trees simulated under a birth-death process, the birth-death model achieved a much higher coverage probability, meaning the true parameter value was contained within the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) interval far more often (87-98% of the time) compared to the coalescent model with exponential growth (25-69% of the time) [31]. This superior performance is attributed to the birth-death model's inherent ability to account for the stochastic population fluctuations that are pronounced in the early phase of an outbreak. The coalescent model, which often assumes a deterministically changing population size, struggles to capture this early stochasticity [31].

Performance in Endemic Situations

In contrast, for endemic scenarios where the infected population size is relatively stable, the performance gap between the two models narrows significantly. A comparative investigation demonstrated that both models produce comparable coverage and accuracy for estimating migration rates in this context [32]. Interestingly, the same study noted that the coalescent model can even generate more precise estimates (tighter confidence intervals) than the birth-death model for endemic diseases [32]. This makes the coalescent a valid and potentially preferable option for studying the spread of pathogens in stable, endemic settings.

Experimental Protocols for Model Comparison

The quantitative findings summarized above are derived from rigorous simulation studies. The following outlines the standard protocol employed by researchers to objectively compare the performance of birth-death and coalescent models.

Protocol 1: Assessing Migration Rate Estimation

This protocol is designed to evaluate the models' ability to infer pathogen spread between subpopulations [32].

- Tree Simulation: Generate a large number of phylogenetic trees using a known, simulated multi-type birth-death process. This process defines the "true" history with known parameters, including specified migration rates between demes and a pre-defined population growth dynamic (e.g., epidemic or endemic).

- Parameter Inference: For each simulated tree, analyze it using both the structured coalescent model (e.g., with constant population size) and the multitype birth-death model (e.g., with a constant rate) in a Bayesian statistical framework like BEAST2.

- Output Analysis: For each analysis, record the estimated migration rate parameters and their associated measures of statistical uncertainty.

- Performance Calculation:

- Accuracy: Calculate the difference between the median estimated migration rate and the known true value used in the simulation.

- Precision: Calculate the width of the 95% HPD interval for the estimates.

- Coverage: Determine the percentage of analyses in which the true parameter value falls within the estimated 95% HPD interval.

Protocol 2: Assessing Growth Rate Estimation

This protocol specifically tests the models' performance in inferring the rate of epidemic spread [31].

- Tree Simulation under Contrasting Models:

- Simulate one set of phylogenetic trees under a constant-rate birth-death model.

- Simulate a second set of trees under a coalescent model with a deterministically, exponentially growing infected population.

- Cross-Inference: Analyze each set of simulated trees using both the birth-death and coalescent inference models. This creates a scenario where the data-generating process and the inference model are sometimes mismatched.

- Performance Calculation: The key metric is, again, the coverage probability of the growth rate parameter. This tests the robustness of each inference model when its underlying assumptions are violated by the data.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for a phylodynamic model comparison study, illustrating the process of simulation, inference, and evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful implementation of the phylodynamic models discussed requires a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Phylodynamic Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Models |

|---|---|---|

| BEAST 2 | A cross-platform software for Bayesian evolutionary analysis of molecular sequences using MCMC. | Primary framework for implementing both birth-death and coalescent model inference [3] [31]. |

| bdmm Package | A BEAST 2 package for multi-type birth-death inference. | Enables phylodynamic analysis under the birth-death model for structured populations; improved to handle larger datasets (>250 samples) [3]. |

| ModelFinder (IQ-TREE) | A fast model selection method for accurate phylogenetic estimates. | Used to select the best-fitting nucleotide/amino acid substitution model and model of rate heterogeneity, which is a critical step prior to phylodynamic inference [33]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A network of computers for computationally intensive tasks. | Essential for running complex Bayesian MCMC analyses, which are computationally demanding and time-consuming. |

| Structured Sequence Data with Metadata | Pathogen genetic sequences annotated with data such as sampling date and location. | The fundamental input data for phylodynamic analysis. Rich metadata is crucial for meaningful structured model analysis. |

The choice between birth-death and coalescent models is not one of absolute superiority but of contextual fitness. The experimental data consistently demonstrates that the birth-death model is the more robust and reliable choice for analyzing epidemic outbreaks, where its explicit modeling of transmission and removal events allows it to naturally accommodate the stochastic population dynamics of an emerging pathogen. For endemic diseases or stable populations, both models are viable, with the coalescent sometimes offering advantages in computational efficiency and estimation precision. When the primary research goal is outbreak source attribution, both models perform equally well in identifying the source location [32]. Therefore, researchers should base their model selection on the specific epidemiological context of their study, the key parameters of interest, and the nature of the available data. As the field progresses, the development of more complex models that integrate genomic and ecological data will further refine our ability to reconstruct and forecast pathogen spread.

The field of phylodynamics, which unifies epidemiological processes with pathogen evolutionary dynamics, has become indispensable for modern outbreak response. It enables researchers to infer critical variables such as transmission trees, reproductive numbers, and migration patterns. However, the exponential growth of pathogen genomic data—exemplified by millions of SARS-CoV-2 sequences—has exposed significant computational bottlenecks in traditional methods [34] [35]. These bottlenecks hinder real-time analysis during public health emergencies.

Two innovative frameworks, SPRTA (Subtree Pruning and Regrafting-based Tree Assessment) and ScITree (Scalable Bayesian inference of Transmission tree), have emerged to address this challenge. Each tackles a distinct yet complementary aspect of phylodynamic inference. SPRTA revolutionizes the assessment of confidence in massive phylogenetic trees, while ScITree enables scalable, accurate reconstruction of transmission trees. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of their performance, methodologies, and applicability for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in outbreak source attribution.

SPRTA: Scalable Phylogenetic Confidence Assessment

SPRTA (Subtree Pruning and Regrafting-based Tree Assessment) introduces a paradigm shift in measuring confidence for phylogenetic trees inferred from millions of genomes. Traditional methods, like Felsenstein's bootstrap, require computationally prohibitive data resampling and are poorly suited to pandemic-scale datasets [34] [36].

- Core Innovation: SPRTA shifts from a "topological focus" (evaluating confidence in clades) to a "mutational focus." It assesses the probability that a specific branch in a tree correctly represents the evolutionary origin of a lineage or variant [34].

- Mechanism: For each branch in a given tree, SPRTA systematically explores alternative evolutionary histories by performing Subtree Pruning and Regrafting (SPR) moves. These moves represent plausible alternative placements of a lineage within the tree. The support for the original branch is then calculated as a function of the likelihoods of the original tree and these alternative topologies [34].

- Integration: It is embedded within widely used phylogenetic software, including MAPLE and IQ-TREE, making it accessible for genomic epidemiological studies [36].

ScITree: Scalable Transmission Tree Inference

ScITree addresses a different computational bottleneck: the inference of transmission trees (who-infected-whom) from epidemiological and genomic data. While the previous Bayesian mechanistic model by Lau et al. was highly accurate, it faced major scalability issues due to its explicit, nucleotide-level modeling of mutations [35].

- Core Innovation: ScITree overcomes this by incorporating the infinite sites assumption to model the evolutionary process. Instead of imputing every single nucleotide, it models genetic mutations between sequences through time as a Poisson process, dramatically reducing the computational parameter space [35].

- Mechanism: It is a fully Bayesian mechanistic model that uses an exact likelihood to integrate spatio-temporal SEIR (Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Removed) models with observed genomic and epidemiological data. Its efficient data-augmentation Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm enables inference of the complete transmission tree and key epidemiological parameters [35].

- Implementation: ScITree is available as an open-source R package, facilitating adoption by the public health and research communities [35].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics of SPRTA and ScITree based on published benchmarks and simulations.

Table 1: Key Performance and Benchmarking Data

| Metric | SPRTA | ScITree | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Demand | >2 orders of magnitude reduction in runtime/memory vs. bootstrap methods [34] | Linear scaling with outbreak size; significant improvement over Lau method's exponential scaling [35] | Benchmark against Felsenstein's bootstrap, aLRT, etc. for SPRTA; benchmark against predecessor for ScITree. |

| Scalability Demonstrated On | Dataset of >2 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes [34] [36] | Simulated outbreaks; real-world FMD outbreak (UK, 2001) [35] | Demonstrates practical application at pandemic scale. |

| Inference Accuracy | N/A (Assesses confidence, not tree topology) | Comparable to the highly accurate Lau method [35] | Accuracy measured by transmission tree reconstruction in simulations. |

| Primary Output | Confidence scores for phylogenetic branches | Transmission tree, epidemiological parameters (e.g., reproductive number) [35] | Outputs are complementary for a full phylodynamic analysis. |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Identifies plausible alternative evolutionary origins for lineages [34] | Full Bayesian framework providing posterior distributions for all inferred parameters [35] | Both provide robust uncertainty quantification. |

Table 2: Methodological Comparison and Application Scope

| Aspect | SPRTA | ScITree |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Assess confidence in phylogenetic trees | Infer transmission trees and epidemiological dynamics |

| Core Method | Likelihood comparison via Subtree Pruning & Regrafting (SPR) moves | Bayesian MCMC with infinite sites mutation model |

| Epidemiological Model | Not directly integrated | Integrated spatio-temporal SEIR model |

| Ideal Use Case | Evaluating reliability of large-scale phylogenies for tracking variant emergence | Reconstructing fine-grained transmission dynamics and superspreading events |

| Key Advantage | Interpretability and speed for massive trees | Scalability without sacrificing mechanistic accuracy |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

SPRTA Workflow and Benchmarking

The validation of SPRTA involved a rigorous benchmarking process against established methods.

- Experimental Setup: Researchers compared SPRTA against several branch support methods, including Felsenstein’s bootstrap, local bootstrap probability (LBP), and approximate likelihood ratio test (aLRT), using simulated SARS-CoV-2-like genome datasets where the true evolutionary history was known [34].

- Workflow:

- Input: A multiple sequence alignment and an inferred rooted phylogenetic tree.

- SPR Operation: For each branch

bin the tree, the algorithm generates alternative tree topologies by performing SPR moves. This involves pruning the subtreeS_band regrafting it onto other parts of the tree to create hypothetical alternative origins for that lineage. - Likelihood Calculation: The likelihood of the original tree and each alternative topology is computed.

- Support Score Calculation: The SPRTA support for branch