Comparative Transcriptomics Across Species: From Evolutionary Insights to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the field of comparative transcriptomics, exploring how the comparison of gene expression across species is revolutionizing our understanding of biology, disease, and therapeutic...

Comparative Transcriptomics Across Species: From Evolutionary Insights to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the field of comparative transcriptomics, exploring how the comparison of gene expression across species is revolutionizing our understanding of biology, disease, and therapeutic development. We cover foundational concepts in evolutionary transcriptomics, detailing how gene regulation drives phenotypic diversity. The article delves into cutting-edge methodologies, from bulk RNA-seq to sophisticated single-cell and spatial transcriptomics platforms, and offers practical guidance on pipeline selection, troubleshooting, and data validation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current trends, addresses key technical challenges, and highlights the transformative potential of cross-species transcriptomic analysis in biomedical research.

Unraveling Evolutionary Secrets: How Transcriptomics Reveals the Blueprint of Life's Diversity

Transcriptional regulation, the process by which cells control the timing and amount of gene expression, represents a fundamental mechanism underlying the remarkable phenotypic diversity observed within and between species. While protein-coding sequences provide the building blocks for biological structures, it is primarily through changes in gene regulation that morphological, physiological, and behavioral innovations arise throughout evolution. The core principle establishing transcriptional regulation as a driver of phenotypic evolution posits that alterations in the patterns of gene expression—controlled by transcription factors (TFs), their binding sites (TFBS), and complex regulatory networks—underlie many of the heritable phenotypic differences observed in nature [1] [2]. This framework explains how species with highly similar genome sequences can exhibit radically different phenotypes, and why closely related organisms often display substantial variation in traits ranging from morphological features to stress response mechanisms.

The evolution of gene regulation operates through multiple interconnected layers, including changes in TF binding preferences, emergence and loss of regulatory DNA elements, and rewiring of transcriptional networks. These changes can occur through various molecular mechanisms such as gene duplication, point mutations in regulatory sequences, and insertion-deletion events [3]. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics across diverse species have revealed that evolutionary changes in transcriptional regulation are not merely accidental byproducts of genetic drift but are often shaped by natural selection to generate adaptive phenotypic variations [2]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the mechanisms, methodologies, and evidence establishing transcriptional regulation as a cornerstone of phenotypic evolution.

Theoretical Foundations: Mechanisms of Regulatory Evolution

The Biophysics and Population Genetics of Transcription Factor Binding Site Evolution

The evolution of transcription factor binding sites represents a fundamental micro-level process driving macro-level phenotypic evolution. TFBS are typically 6-12 base pairs in eukaryotic organisms and undergo continuous evolutionary dynamics of gain and loss through point mutations and insertion-deletion events [2]. Theoretical models combining biophysical principles with population genetics reveal that the evolutionary rates of TFBS gain and loss are typically slow for isolated binding sites, unless selection is extremely strong. These rates decrease drastically with increasing TFBS length or increasingly specific protein-DNA interactions, making the evolution of sites longer than approximately 10 bp unlikely on typical eukaryotic speciation timescales [2].

Several biophysical and population genetic factors crucially influence TFBS evolutionary dynamics:

- Selection Strength: Strong directional selection can significantly accelerate TFBS emergence, with evolutionary rates proportional to the product of population size (N) and selection advantage (s).

- Initial Sequence Context: The presence of "pre-sites" or partially decayed old sites in the initial sequence dramatically facilitates gain of new TFBS by reducing the mutational distance to functional binding sequences.

- Cooperativity: Biophysical cooperativity between transcription factors can accelerate binding site evolution and partially account for the lack of perfect correlation between identifiable binding sequences and transcriptional activity.

- Regulatory Sequence Length: The availability of longer regulatory sequences in which multiple binding sites can evolve simultaneously increases the probability of functional TFBS emergence [2].

Theoretical investigations demonstrate that evolutionary processes approach the stationary distribution of binding sequences very slowly, raising questions about the validity of equilibrium assumptions in evolutionary models of gene regulation [2]. This non-equilibrium nature of regulatory evolution highlights the importance of historical contingencies and phylogenetic constraints in shaping contemporary gene regulatory architectures.

The organization of transcription factors into "motif families"—groups of TFs with similar binding preferences—provides crucial insights into the evolutionary dynamics of transcriptional regulation. The Birth-Death-Innovation model, a one-parameter evolutionary model, explains the empirical repartition of TFs in motif families and highlights relevant evolutionary forces shaping this organization [3]. This model incorporates three fundamental processes: family growth via gene duplication (Birth), element deletion through inactivation or loss (Death), and emergence of new families through sequence divergence (Innovation).

Analysis of the human TF repertoire reveals significant deviations from neutral expectations, indicating selective pressures on specific regulatory components:

- Over-expanded Families: Three TF families, including HOX and FOX genes, show significant expansion beyond neutral expectations, suggesting adaptive value in their duplication and retention.

- Singleton TFs: A set of "singleton" TFs exists for which duplication seems to be selected against, potentially indicating constraints on dosage sensitivity or pleiotropic functions.

- Zinc Finger TFs: Transcription factors with Zinc Finger DNA binding domains exhibit a higher-than-average rate of diversification of their binding preferences, highlighting the role of specific structural domains in regulatory evolution [3].

Comparative analysis of TF motif family organization across eukaryotic species suggests an evolutionary trend toward increased redundancy of binding with organismal complexity, potentially enabling more sophisticated regulatory networks and phenotypic intricacy [3].

Comparative Evidence Across Biological Kingdoms

Transcriptional Regulation in Animal Evolution

Cross-species comparative transcriptomics provides compelling evidence for the role of transcriptional regulation in phenotypic evolution across the animal kingdom. Large-scale analyses of transcriptomic responses to chemical exposures across six vertebrate species (including Japanese quail, fathead minnow, African clawed frog, double-crested cormorant, rainbow trout, and northern leopard frog) reveal both conserved and species-specific regulatory patterns [4]. These studies identified consistent differentially expressed genes across taxonomic groups, with CYP1A1 emerging as the most frequently responsive gene, followed by CTSE, FAM20CL, MYC, ST1S3, RIPK4, VTG1, and VIT2 [4].

The most commonly enriched pathways in cross-species comparisons include:

- Metabolic pathways

- Biosynthesis of cofactors

- Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites

- Chemical carcinogenesis

- Drug metabolism

- Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 [4]

Advanced computational methods like Icebear (a neural network framework that decomposes single-cell measurements into factors representing cell identity, species, and batch effects) enable precise cross-species comparison and prediction of gene expression profiles [5]. This approach facilitates understanding of regulatory changes during evolution and transfer of knowledge from model organisms to humans. Application of Icebear to X-chromosome upregulation (XCU) in mammals revealed evolutionary and diverse adaptations of X-chromosome upregulation, demonstrating how transcriptional regulation has evolved to balance gene expression following sex chromosome differentiation [5].

Transcriptional Regulation in Plant Evolution

Comparative transcriptomic analyses in plants similarly highlight the central role of regulatory evolution in phenotypic diversification. Studies comparing Arabidopsis, rice, and barley responses to oxidative stress and hormone treatments reveal both common and opposite transcriptional responses to identical stimuli [6]. Between 15% to 34% of orthologous differentially expressed genes show opposite responses between species, indicating significant diversification in regulatory networks despite gene conservation [6].

The conservation of mitochondrial dysfunction response across all three plant species, in terms of both responsive genes and regulation via the mitochondrial dysfunction element, demonstrates how core regulatory modules can be maintained over evolutionary timescales [6]. Conversely, many prominent salt-stress responsive genes show opposite responsiveness to multiple stresses, highlighting fundamental differences in stress response regulation between species [6]. These comparative transcriptomic approaches provide roadmaps for understanding molecular similarities and differences between model species and crops, enabling more effective selection of target genes and pathways for agricultural improvement.

Table 1: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting Transcriptional Regulation as a Driver of Phenotypic Evolution

| Study System | Key Findings | Evolutionary Implications | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebrate EcoToxChip Project | Common differentially expressed genes (CYP1A1, etc.) and enriched pathways across 6 species | Conserved regulatory responses to environmental stressors | [4] |

| Plant Stress Response (Arabidopsis, rice, barley) | 15-34% of orthologous DEGs show opposite responses between species | Diversification of regulatory networks despite gene conservation | [6] |

| TF Binding Site Evolution | TFBS gain/loss rates are typically slow unless selection is strong or sequences are favorable | Constraints and opportunities in regulatory evolution | [2] |

| Human TF Repertoire | Organization into motif families with deviations from neutral expectations (over-expanded families, etc.) | Selective pressures shaping transcription factor evolution | [3] |

| X-chromosome Upregulation | Evolutionary adaptations in X-chromosome regulation across mammalian species | Transcriptional solutions to gene dosage challenges | [5] |

Methodological Framework for Comparative Transcriptomics

Experimental Approaches and Workflows

Cutting-edge research in evolutionary transcriptomics relies on sophisticated experimental designs and computational frameworks. The EcoToxChip project exemplifies a comprehensive approach, generating RNA-sequencing data from experiments involving model and ecological species at multiple life stages exposed to diverse chemicals of environmental concern [4]. This project utilized six species (Japanese quail, fathead minnow, African clawed frog, double-crested cormorant, rainbow trout, and northern leopard frog) exposed to eight chemicals (ethinyl estradiol, hexabromocyclododecane, lead, selenomethionine, 17β trenbolone, chlorpyrifos, fluoxetine, and benzo[a]pyrene) known to perturb diverse biological systems [4].

Standardized RNA-sequencing protocols ensure cross-study comparability:

- RNA extraction using RNeasy mini or RNA Universal mini kits with on-column DNase I digestion

- Quality assessment via RNA Integrity Number (RIN ≥ 7.5)

- Library preparation and sequencing on Illumina platforms (HiSeq 4000 or Novaseq 6000)

- Sequencing depth of at least 12 million paired-end reads per sample [4]

For cross-species single-cell transcriptomics, the Icebear framework employs a sophisticated mapping strategy:

- Creation of a multi-species reference genome by concatenating reference genomes

- Mapping reads to the multi-species reference, retaining only uniquely mapping reads

- Removal of PCR duplicates and repetitive elements

- Elimination of species-doublet cells (where the sum of second- and third-largest species counts >20% of all counts)

- Re-mapping reads for single-species cells to corresponding species-specific references [5]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Example | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EcoToxChip RNASeq Database | 724 samples from 49 experiments across 6 species | Cross-species investigation of transcriptomic responses | [4] |

| ExpressAnalyst with Seq2Fun Algorithm | Translates transcriptomic reads into amino acid sequences and maps to homologs | Analysis of species with varying genome assembly quality | [4] |

| Icebear Neural Network | Decomposes single-cell measurements into cell identity, species, and batch factors | Cross-species prediction and comparison at single-cell resolution | [5] |

| ChEA3 Transcription Factor Analysis | Predicts TFs associated with input gene sets via enrichment analysis | Identifying regulatory factors behind evolutionary expression changes | [7] |

| CIS-BP Database | Classification of TFs based on binding preferences (PWMs) | Defining motif families and tracing their evolution | [3] |

Computational and Analytical Frameworks

Advanced computational methods are essential for deciphering evolutionary patterns in transcriptional regulation. The Seq2Fun algorithm addresses critical challenges in cross-species transcriptomics by translating sequencing reads from any input species into all possible short amino acid sequences and mapping them to a comprehensive database (EcoOmicsDB) housing approximately 13 million protein-coding genes from 687 species [4]. This approach alleviates reliance on de novo transcriptome assembly and facilitates analysis of species with limited genomic resources.

The ChEA3 (ChIP-X Enrichment Analysis Version 3) platform enables transcription factor enrichment analysis through orthogonal omics integration [7]. This tool compares input gene sets to multiple libraries of TF-target interactions assembled from:

- ChIP-seq experiments from ENCODE, ReMap, and literature sources

- Co-expression data from GTEx and ARCHS4

- Co-occurrence patterns from thousands of gene lists in Enrichr

- Gene signatures from single TF perturbation experiments [7]

For modeling TFBS evolution, theoretical frameworks combine biophysical models of protein-DNA interaction with population genetics to estimate rates of binding site gain and loss under different evolutionary scenarios [2]. These models incorporate parameters for mutation rates, selection strength, population size, and biophysical properties of TF-DNA interactions to simulate evolutionary dynamics across realistic timescales.

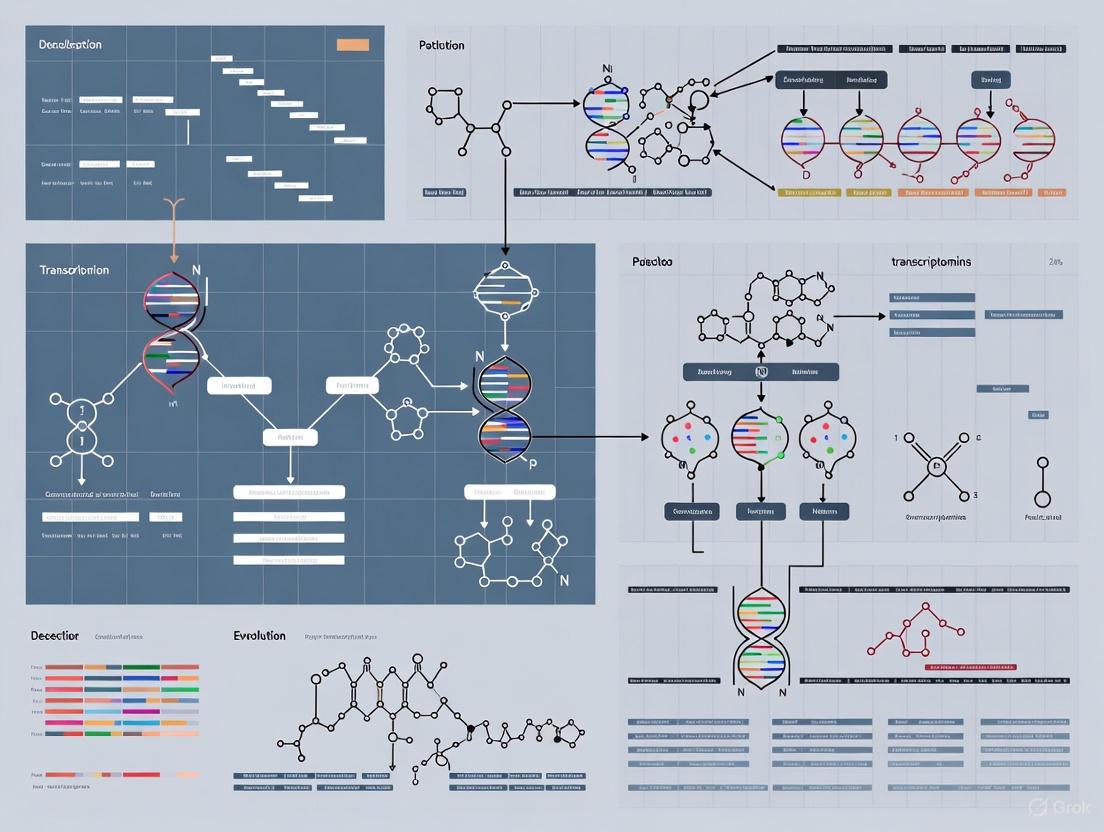

Visualization of Evolutionary Transcriptomics Concepts

Workflow for Cross-Species Transcriptomic Analysis

Diagram 1: Cross-species transcriptomic analysis workflow integrating wet-lab and computational approaches for evolutionary insights.

Transcription Factor Binding Site Evolutionary Dynamics

Diagram 2: Evolutionary dynamics of transcription factor binding sites showing alternative pathways for regulatory evolution.

The convergent evidence from theoretical models, cross-species comparative studies, and molecular experiments firmly establishes transcriptional regulation as a central driver of phenotypic evolution. The core principles emerging from these diverse approaches include: (1) evolution of transcriptional regulation operates through quantifiable biophysical and population genetic processes; (2) regulatory changes can produce both conserved and divergent phenotypic outcomes across lineages; (3) the evolutionary dynamics of regulatory elements follow predictable patterns influenced by selection strength, mutation types, and initial sequence context; and (4) comparative transcriptomics provides powerful insights for understanding evolutionary adaptations across biological kingdoms.

Future research in evolutionary transcriptomics will increasingly leverage single-cell technologies, machine learning approaches, and expanded taxonomic sampling to decipher the precise regulatory mechanisms underlying phenotypic diversification. Integration of these multidimensional data will further illuminate how transcriptional regulation serves as the crucial interface between conserved genetic sequences and diverse biological forms, ultimately providing a comprehensive framework for understanding evolutionary innovation across the tree of life.

Comparative transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful disciplinary bridge connecting evolutionary biology, developmental biology, and genomics. By analyzing gene expression patterns across different species, organs, and developmental stages, researchers can decipher the molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic diversity and evolutionary innovations [8]. This approach has revolutionized evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo), shifting from single-gene expression studies to genome-wide analyses that reveal the overall impact and molecular mechanisms of convergence, constraint, and innovation in anatomy and development [9]. The field now extends from prokaryotes to complex multicellular eukaryotes, enabling researchers to address fundamental questions about the evolution of gene regulation, the origins of morphological diversity, and the molecular basis of adaptation across the tree of life.

The power of comparative transcriptomics lies in its ability to reveal not just sequence differences but regulatory variations that often underlie phenotypic evolution. As technologies have advanced from microarrays to high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), the resolution and scale of comparative studies have expanded dramatically [10]. These technical advances now allow researchers to track expression evolution from microbial organisms to mammalian organs, creating unprecedented opportunities to understand how transcriptional regulation shapes biological diversity.

Fundamental Principles and Methodological Framework

Defining Comparative Approaches

Comparative transcriptomics operates on several conceptual levels, each with distinct methodological considerations. Historical homology compares structures with common evolutionary origins inherited from a common ancestor, while biological homology focuses on organs sharing developmental constraints regardless of common descent [8]. A third approach compares functionally equivalent structures that perform similar functions but may not share evolutionary origins, such as comparing tetrapod lungs with fish gills as respiratory organs [8].

The choice of comparison criteria depends on the evolutionary questions being addressed. For studies of deep homology and conserved developmental mechanisms, historical homology provides the most appropriate framework. Conversely, investigations of convergent evolution often benefit from comparing functionally equivalent structures that evolved independently [8]. These conceptual distinctions are crucial for proper experimental design and interpretation of comparative transcriptomic data.

Key Methodological Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Methodological Challenges in Comparative Transcriptomics

| Challenge | Description | Emerging Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Homology | Defining comparable structures across divergent species | Computational ontologies (e.g., Uberon), homology criteria [9] |

| Developmental Staging | Aligning comparable developmental phases across species | Transcriptomic timing signatures, developmental milestones [11] |

| Orthology Assignment | Identifying evolutionarily related genes across genomes | OrthoFinder, protein-based alignment, single-copy ortholog filtration [12] [13] |

| Data Normalization | Making expression levels comparable across species | Single-copy ortholog analysis, variance-stabilization normalization [13] |

| Cellular Heterogeneity | Accounting for differing cell type proportions in tissues | Cell type deconvolution, single-cell approaches [11] |

A significant technical challenge in cross-species transcriptomics involves orthology assignment. As one researcher notes, "I have a hard time understanding what is the best approach to find differentially expressed genes between species when there are 5 different reference genomes" [13]. The solution typically involves identifying groups of orthologous genes ("orthogroups") using tools like OrthoFinder, then focusing on single-copy orthologs present in all species studied [13]. This approach facilitates meaningful comparisons while acknowledging that transcriptomic datasets only contain genes expressed in the target tissue at sampling time, potentially reducing the number of available single-copy orthologs [13].

Another critical consideration is cellular heterogeneity, as gene expression in complex tissues reflects both transcriptional regulation and abundance of different cell types [11]. Studies comparing mouse molar development revealed that transcriptomic signatures between upper and lower molars were largely shaped by differences in relative abundance of different cell types rather than solely by regulation of individual genes [11]. This insight underscores the importance of single-cell approaches or computational deconvolution methods in comparative studies.

Evolutionary Questions Across Biological Scales

Prokaryotic Transcriptomic Evolution

Comparative transcriptomics has revealed unexpected complexity in prokaryotic transcriptomes, including abundant non-coding RNAs, cis-antisense transcription, and regulatory untranslated regions (UTRs) [14]. A standardized study across 18 model organisms spanning 10 bacterial and archaeal phyla created comparative transcriptome maps that enable searches for conserved transcriptomic elements across the microbial tree of life [14]. This approach has identified genes with exceptionally long 5'UTRs across species, corresponding to known riboswitches and suggesting novel regulatory elements [14].

The prokaryotic transcriptome viewer (http://exploration.weizmann.ac.il/TCOL) provides a framework for comparative studies of the microbial non-coding genome, demonstrating how standardized RNA-seq methods can illuminate evolutionary patterns across deeply divergent lineages [14]. This resource sets the stage for understanding the evolution of regulatory mechanisms in the most ancient branches of the tree of life.

Evolution of Sex-Biased Expression

Studies in bivalve species (Ruditapes decussatus and R. philippinarum) have provided insights into the evolution of sex-biased genes. Researchers found a relatively low number of sex-biased genes (1,284, corresponding to 41.3% of orthologous genes between the two species), likely due to the absence of sexual dimorphism, with transcriptional bias maintained in only 33% of orthologs [12]. The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) was generally low, indicating purifying selection, but genes with female-biased transcription maintained between species showed significantly higher dN/dS [12].

This study challenged established paradigms by reporting a lack of clear correlation between transcription level and evolutionary rate, in contrast to previous studies that reported negative correlation [12]. The findings highlight how comparative transcriptomics in understudied taxa can reveal unexpected evolutionary patterns and call into question methodological approaches generally used in such comparative studies.

Development and Evolution of Serial Organs

Table 2: Insights from Comparative Transcriptomics of Serial Organs

| Organ System | Species | Key Findings | Evolutionary Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molar teeth | Mouse (Mus musculus) | Transcriptomic differences shaped by cell proportions; time-shift differences in transcriptomes related to cusp tissue abundance [11] | Developmental heterochrony contributes to morphological divergence of serial organs |

| Forelimb/hindlimb | Vertebrates | Shared developmental program with position-dependent expression of "identity genes" (e.g., Tbx4, Pitx1) [11] | Similar transcriptomic approach applicable to understanding limb evolution |

| Bivalve gonads | Ruditapes species | Low number of sex-biased genes maintained across species; faster sequence evolution of female-biased genes [12] | Represents different selective pressures on sex-biased genes in closely related species |

The development of serially homologous organs—such as upper and lower molars or forelimbs and hindlimbs—provides powerful models for understanding how phenotypic divergence arises from shared developmental programs. Research on mouse molars has demonstrated that transcriptomic signatures can distinguish between developing homologous organs with different morphologies [11]. These studies revealed that lower/upper molar differences are maintained throughout morphogenesis and stem from differences in relative abundance of mesenchyme and constant differences in gene expression within tissues [11].

A particularly important finding concerns developmental heterochrony, where transcriptomes differ due to temporal shifts in developmental processes rather than completely divergent genetic programs [11]. For example, clear time-shift differences were observed in the transcriptomes of upper and lower molars related to cusp tissue abundance, with transcriptomes differing most during early-mid crown morphogenesis [11]. This corresponds to exaggerated morphogenetic processes in the upper molar involving fewer mitotic cells but more migrating cells, demonstrating how comparative transcriptomics can reveal the cellular processes underpinning differences in organ development.

Transcriptomics in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Applications

Comparative transcriptomics has found important applications in drug discovery, particularly for natural products. Statistical analyses reveal that more than one-third of new drugs reaching the market between 1981 and 2014 were directly or indirectly derived from natural products, with the annual global medicine market recently reaching 1.1 trillion US dollars [10]. In the cancer field, from the 1940s to the end of 2014, 85 of the 175 small molecules approved by the FDA were either natural products or derived from them [10].

Transcriptomic approaches facilitate multiple aspects of drug discovery:

- Mechanism elucidation: Illuminating the molecular mechanism, composition of phytochemical components, and potential therapeutic targets of natural drugs [10]

- Toxicity screening: Identifying genes related to drug sensitivity or resistance and predicting potential positive effects or side effects [10]

- Biomarker identification: Detecting expression patterns that can determine which patients will respond to specific therapies [10]

The application of DermArray and PharmArray DNA microarrays to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) tissue samples exemplifies this approach, leading to the identification of seven verified genes that may become new candidate molecular targets for IBD treatment [10].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized RNA-seq Across Species

For comparative transcriptomics across evolutionarily distant species, standardized protocols are essential for meaningful comparisons. A prokaryotic study across 10 phyla established a robust workflow [14]:

- Sample preparation: Culture organisms under standardized conditions

- RNA sequencing: Use standardized RNA-seq methods across all species

- Transcriptome mapping: Create detailed, comparable annotations for each organism

- Comparative analysis: Implement BLAST-searchable databases and comparative tools

This standardized approach enabled the identification of conserved regulatory elements across deeply divergent lineages, demonstrating the power of carefully controlled comparative methodologies [14].

Cross-Species Differential Expression Analysis

For differential expression analysis across multiple species with different reference genomes, researchers have developed sophisticated orthology-based workflows [13]:

Figure 1: Cross-Species Transcriptomics Workflow

This workflow addresses the central challenge of comparing expression across different genomes by focusing on single-copy orthologs. As one researcher describes: "We searched all transcriptomes for groups of orthologous genes using OrthoFinder. In total, we identified 48,684 orthogroups, including 5,591 orthologues that were single-copy in all eight species" [13]. The resulting count matrix for single-copy orthologs can then be analyzed using standard differential expression tools like DESeq2, with appropriate normalization for cross-species comparisons [13].

Analyzing Transcriptomic Dynamics in Development

Studies of developing serial organs require specialized approaches to capture temporal dynamics [11]:

- Sample collection: Collect organs at multiple developmental time points

- Transcriptome profiling: Generate RNA-seq data for each time point

- Signature identification: Extract "transcriptomic signatures" - groups of genes with coordinated expression differences

- Cellular interpretation: Relate expression differences to changes in cell type abundance and regulation

- Heterochrony analysis: Identify temporal shifts in developmental programs

This approach successfully revealed how transcriptomic differences between developing upper and lower molars in mice reflect both differences in cell type proportions and heterochrony in developmental programs [11].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Comparative Transcriptomics

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Identifies orthogroups across multiple species | Critical first step for cross-species comparisons [13] |

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis | Identifying DE genes across species with normalized counts [13] |

| Bgee database | Curated expression data and homology relationships | Provides comparable expression patterns across species [9] |

| Uberon ontology | Computational representation of homology | Anatomical structure comparison across species [8] |

| DermArray/PharmArray | Targeted expression profiling | Drug screening applications [10] |

| StringTie | Transcript assembly from RNA-seq data | Reference-based transcriptome reconstruction [13] |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | Resolution of cellular heterogeneity | Distinguishing regulation from cell proportion effects [11] |

Comparative transcriptomics has fundamentally expanded our ability to address evolutionary questions across the tree of life. From revealing unexpected complexity in prokaryotic transcriptomes to deciphering the developmental basis of morphological evolution in mammals, this approach continues to provide insights into the regulatory mechanisms underlying biological diversity. The ongoing development of single-cell technologies, improved orthology detection methods, and sophisticated computational frameworks for comparing developmental processes promises to further enhance the power of comparative transcriptomics.

As these methodologies become more accessible and comprehensive, they will enable researchers to tackle increasingly profound questions about the evolution of gene regulation, the origin of novel traits, and the molecular basis of adaptation. The integration of comparative transcriptomics with other functional genomics approaches will continue to illuminate the mechanistic links between genotype and phenotype across the breadth of the tree of life.

The field of comparative biology is undergoing a transformative shift driven by large-scale genomic consortia that are generating unprecedented amounts of high-quality genetic data across the tree of life. These initiatives are revolutionizing our approach to fundamental questions in evolution, disease mechanisms, and biodiversity conservation by providing comprehensive genomic resources that enable direct cross-species comparisons. Projects like the Vertebrate Genomes Project (VGP), Earth Biogenome Project (EBP), and Y1000+ Project are at the forefront of this data revolution, each with distinct but complementary goals in sequencing eukaryotic lifeforms [15] [16] [17]. For researchers in comparative transcriptomics, these resources provide the essential genomic frameworks needed to analyze gene expression patterns, regulatory networks, and functional elements across diverse species. This guide objectively compares the approaches, outputs, and applications of these major genomic initiatives to help researchers select appropriate resources for their cross-species investigations.

The current landscape of large-scale genomic sequencing projects encompasses varying taxonomic scopes and scientific priorities, from focused studies on specific taxonomic groups to comprehensive planetary-scale sequencing efforts.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Genomic Consortia

| Project | Primary Scope | Sample Size Goal | Key Sequencing Quality | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGP [15] [18] | Vertebrate species | 72,000 extant species | Near error-free, chromosome-level, haplotype-phased | Comparative biology, conservation, human disease research |

| EBP [16] | All eukaryotes | ~1.5 million species | Chromosome-level assemblies | Biodiversity understanding, ecosystem conservation, societal benefits |

| Y1000+ Project [17] | Saccharomycotina yeasts | >1,000 yeast species | Comprehensive genetic catalog | Metabolic evolution, ecological adaptations, industrial applications |

The Vertebrate Genomes Project (VGP) has emerged from earlier initiatives like the Genome 10K Community of Scientists, applying lessons learned to focus on producing high-quality, near error-free reference genome assemblies for all vertebrate species [15] [18]. The project employs a phased approach, beginning with sequencing one representative species from each of the 260 vertebrate orders (Phase 1), followed by representatives from all vertebrate families (Phase 2), and ultimately progressing to all genera and species (Phase 3) [19]. This systematic approach ensures that the most phylogenetically diverse species are sequenced first, maximizing the utility for broad comparative studies.

The Earth Biogenome Project (EBP) represents perhaps the most ambitious biological sequencing project conceived, aiming to generate high-quality genome sequences for all known eukaryotic species within a defined timeframe [16]. This project addresses the critical need to document Earth's genetic diversity amid rapid biodiversity declines due to climate change and human activity. The EBP recognizes that genomic information provides fundamental insights into the origin, evolution, and maintenance of biodiversity while offering potential solutions for societal challenges in health, agriculture, and environmental management.

Unlike the taxonomic breadth of the VGP and EBP, the Y1000+ Project focuses deeply on a single subphylum—Saccharomycotina yeasts—with the goal of creating the first comprehensive catalog of genetic and functional diversity for this group [17]. This project exemplifies how targeted sequencing of evolutionarily or economically important groups can yield profound insights into metabolic diversity, ecological specialization, and evolutionary innovation.

Experimental Methodologies and Data Generation

Large-scale genomic projects employ sophisticated technological pipelines that have been optimized through years of method development. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for researchers evaluating the quality and appropriateness of different genomic resources.

Table 2: Comparative Sequencing and Assembly Methodologies

| Methodological Component | VGP Approach [15] [19] | Typical Transcriptomics Methods [20] | Application in Comparative Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequencing | Multi-platform: PacBio SMRT (60x), 10x Genomics (68x), Bionano optical mapping, Hi-C (68x) | RNA-Seq, microarrays, SAGE, CAGE | Genome assembly completeness affects transcriptome annotation accuracy |

| RNA Sequencing | PacBio IsoSeq, RNA-Seq for annotation | RNA-Seq (high-throughput), microarrays (predetermined sequences) | Identifies splice variants, non-coding RNAs, expression quantification |

| Assembly Method | FALCON unzip, MARVEL, Scaff10X, TGH, Salsa, Arrow | Transcriptome assembly: de novo or reference-based | Determines continuity, error rate, gap presence in final assembly |

| Quality Metrics | Error-free, near-gapless, chromosome-level, haplotyped phased | Accuracy, sensitivity, dynamic range, technical reproducibility | Affects downstream analysis including gene family and expression evolution |

The VGP employs an exceptionally rigorous multi-platform sequencing approach that represents the current gold standard in reference genome generation [19]. This includes 60x genome coverage using PacBio SMRT (Single Molecule Real Time) sequencing to generate long reads that span repetitive regions, 68x coverage using 10x Genomics linked reads for intermediate-range scaffolding, Bionano optical mapping to correct potential scaffolding errors, and Hi-C data for large-scale scaffolding and chromosome-level assembly [19]. This comprehensive approach addresses the limitations of earlier sequencing technologies that often resulted in fragmented assemblies with persistent gaps and errors.

For transcriptomic data generation, contemporary projects typically employ RNA-Seq methodologies, which have largely superseded earlier techniques like expressed sequence tags (ESTs), serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE), and microarrays [20]. RNA-Seq involves reverse transcribing RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) followed by high-throughput sequencing, which allows both quantification of transcript abundance and identification of structural features such as splice variants [20]. The VGP complements its DNA sequencing with PacBio IsoSeq data and RNA-Seq for comprehensive genome annotation, enabling precise determination of gene models and alternative splicing events [19].

Diagram 1: Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Workflow

Data Management and Accessibility

The utility of large-scale genomic projects depends critically on how the resulting data are stored, curated, and made accessible to the research community. Each major project has established specific data repositories and distribution mechanisms.

The VGP stores its data in the Genome Ark, a digital open-access library of high-quality reference genomes, with final deposition in the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) public databases including NCBI, ENSEMBL, and UCSC Genome Browser [15] [18]. This ensures that data conform to community standards and are accessible through multiple familiar interfaces. The project maintains an open-door policy, welcoming collaboration from researchers worldwide in sample collection, genome assembly, and data analysis [15].

Specialized transcriptomic databases have also emerged to facilitate comparative studies, such as the Mammalian Transcriptomic Database (MTD), which focuses on transcriptomes of humans, mice, rats, and pigs [21]. This database allows browsing of genes by genomic coordinates or KEGG pathway and provides expression information at exon, transcript, and gene levels integrated into a genome browser. Such specialized resources enable both intra-species and inter-species comparative transcriptomic analysis, which is valuable for evolutionary and functional studies [21].

Research Applications and Case Studies

The genomic resources generated by large-scale consortia are enabling diverse research applications across biological disciplines, from conservation genetics to human disease mechanisms.

Conservation Genomics

The VGP has generated reference genomes for critically endangered species including the kākāpō (a flightless parrot endemic to New Zealand) and the vaquita (the most endangered marine mammal) [15]. Analyses of these genomes have revealed evolutionary and demographic histories showing purging of harmful mutations in the wild and long-term small population size at genetic equilibrium [15]. These insights are invaluable for designing effective conservation strategies based on the genetic health of endangered populations.

Disease Mechanism Insights

The Bat1K consortium, in partnership with VGP, has generated high-quality reference genomes for six bat species, revealing "selection and loss of immunity-related genes that may underlie bats' unique tolerance to viral infection" [15]. These findings provide novel avenues for research on increasing survivability to emerging infectious diseases, with particular relevance to COVID-19 and other viral pandemics. The chromosomal evolution changes found in bat species may contribute to their enhanced immune systems and pathogen tolerance [15].

Ecological and Metabolic Adaptations

The Y1000+ Project has enabled ecological studies of yeast species that challenge longstanding macroecological patterns [17]. Contrary to traditional expectations that species diversity should increase near the equator, yeast species were found to be most abundant in montane forest habitats, suggesting that "elevational clines along a mountainside create all these micro-habitats that can host a lot more species" [17]. The project also revealed that yeast species with specialized metabolic capabilities (those metabolizing fewer carbohydrates) have more restricted geographical ranges compared to generalist species, connecting biochemical processes to macroecological patterns.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Conducting research with large-scale genomic databases requires specific analytical tools and resources. The following table summarizes key reagents and computational resources used in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic Analyses

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Project Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | PacBio SMRT, 10x Genomics, Bionano, Hi-C | Generate long reads, linked reads, optical maps, chromatin interactions | VGP genome assembly pipeline [19] |

| Assembly Software | FALCON unzip, MARVEL, Scaff10X, TGH, Salsa, Arrow | Genome assembly, error correction, scaffolding, polishing | Dresden genome assembling pipeline [19] |

| Annotation Tools | RNA-Seq alignment, PacBio IsoSeq, homology prediction | Gene prediction, transcript identification, functional annotation | Genome annotation across projects [20] [19] |

| Analysis Platforms | MTD database, Genome Ark, ENSEMBL, UCSC | Data browsing, comparative analysis, visualization | Data dissemination and analysis [15] [21] |

| Specialized Reagents | DNase treatment, poly-A affinity beads, ribosomal depletion probes | RNA isolation, mRNA enrichment, quality control | Transcriptomics sample preparation [20] |

The data revolution in genomics is fundamentally transforming comparative biological research through systematically generated, high-quality resources that enable unprecedented cross-species analyses. The Vertebrate Genomes Project, Earth Biogenome Project, and Y1000+ Project each contribute distinct but complementary assets to this new research paradigm, from taxonomic breadth to deep functional insights. For researchers in comparative transcriptomics, these resources provide the essential genomic frameworks needed to analyze gene expression patterns, regulatory networks, and functional elements across diverse species. As these projects continue to grow and evolve, they will undoubtedly yield further insights into fundamental biological processes, disease mechanisms, and conservation strategies, ultimately advancing both basic science and applied biomedical research.

Insights from Evolutionary Genomics: Novel Gene Origination, Transposon Dynamics, and Protein Family Evolution

Evolutionary genomics provides a powerful lens through which to examine the molecular mechanisms that generate diversity and complexity in living organisms. By comparing genomic and transcriptomic data across species, researchers can decipher the history and function of fundamental genetic components. This guide objectively compares the roles and experimental approaches used to study three key drivers of genome evolution: novel gene origination, transposable element (TE) dynamics, and the expansion of protein families. The supporting quantitative data and detailed methodologies provided herein serve as a reference for researchers investigating the genetic underpinnings of adaptation, speciation, and disease.

Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, quantitative impacts, and key experimental data for the primary mechanisms driving genome evolution.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Evolutionary Genomic Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Core Function & Impact | Key Quantitative Data / Evidence | Representative Experimental Organism(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Gene Origination | Generates new genetic material, providing substrate for evolutionary innovation and new cellular functions [22]. | >100 genes duplicate per million years in the human genome; ~6% of human-chimp difference due to gene number variation [22]. | Drosophila (e.g., jingwei gene), Vertebrates [23] [22] |

| Transposon Dynamics | Shapes genome architecture, size, and regulation; drives structural variation and epigenetic changes [24] [25]. | TEs constitute 20-30% of small genomes (e.g., Arabidopsis) to over 85% of large genomes (e.g., maize, lily) [24]. | Maize, Arabidopsis thaliana, Cotton (Gossypium) [24] [25] [26] |

| Protein Family Evolution | Expands functional capabilities through gene duplication and diversification, leading to family and superfamily formation [27] [22]. | Protein family and superfamily sizes follow power-law distributions, indicating biased evolutionary expansion [27]. | Model organisms in early evolution simulations, Diverse eukaryotes [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Gene Age Estimation using Phylogenetic Profiling

Objective: To estimate the evolutionary age of a protein-coding gene by identifying its first appearance in a phylogenetic tree.

Workflow:

- Sequence Acquisition: Obtain the protein sequence of the gene of interest from a target species.

- Ortholog Identification: Search for orthologs (genes descended from a common ancestor) across a wide range of species using tools like Ensembl Compara [23]. This step requires significant computational resources [23].

- Timetree Construction: Map the presence or absence of the gene onto a species timetree, which includes divergence times (e.g., from the TimeTree database) [23].

- Age Inference: Apply a parsimony algorithm (e.g., Wagner parsimony) to trace the evolutionary trajectory of the gene and infer the branch (and corresponding time in million years) where it originated [23].

- Database Integration: Resources like GenOrigin automate this pipeline, allowing for batch processing and querying of gene ages across hundreds of species [23].

Profiling Transposable Element Activity

Objective: To identify and quantify the activity of transposable elements in a genome, particularly in response to stressors like polyploidy.

Workflow:

- Genome Sequencing & Assembly: Generate high-quality genome assemblies for the organisms of interest. Long-read sequencing technologies are particularly valuable for resolving repetitive TE-rich regions [24] [28].

- TE Library Construction: Create a custom library of known TE sequences for the organism, or use a de-novo TE discovery tool like GenomeDelta to identify sample-specific TE insertions without a pre-defined library [25].

- Read Mapping & Identification: Map sequencing reads (from genomic or transcriptomic data) to the reference genome and the TE library to identify TE insertion sites and their copy numbers [24].

- Epigenetic Analysis: Apply techniques like bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) to assess the DNA methylation state of TEs, which is a key marker of their epigenetic silencing and activity [24] [26].

- Expression Analysis: Use RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) to detect TE-derived transcripts, indicating active transcription and potential mobility [25].

Comparative Single-Cell Transcriptomics for Cell Type Evolution

Objective: To compare cellular composition and gene expression patterns across the brains of closely related species to uncover evolutionary adaptations.

Workflow (as applied to drosophilid brains) [29]:

- Tissue Dissociation & Nuclei Isolation: Dissect central brain tissues from multiple species (e.g., D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia) and isolate nuclei.

- Single-Nucleus RNA Sequencing (snRNA-seq): Generate barcoded libraries from individual nuclei and perform high-throughput sequencing.

- Data Integration & Clustering: Use computational pipelines (e.g., Seurat) to integrate datasets from different species. Techniques like Reciprocal Principal Component Analysis (RPCA) are used to correct for technical variation and batch effects, enabling direct cross-species comparison [29].

- Cell Type Annotation: Identify distinct cell clusters and annotate them as specific neuronal or glial types using known marker genes.

- Differential Abundance & Expression: Statistically compare the proportions of cell types (differential abundance) and gene expression levels (differential expression) between species to identify evolved differences [29].

The following diagram visualizes the logical sequence and key outputs of this integrated experimental approach to studying brain evolution.

This table details key bioinformatic databases, tools, and experimental models essential for research in evolutionary genomics.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Evolutionary Genomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function / Utility | Relevant Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| GenOrigin [23] | Database | Provides gene age estimates (in million years) for protein-coding genes across 565 species. | Novel Gene Origination |

| Ensembl Compara [23] | Database | Provides pre-computed orthology and paralogy relationships between genes across species. | Novel Gene Origination, Protein Family Evolution |

| TimeTree [23] | Database | A repository of species divergence times, crucial for calibrating evolutionary timescales. | Novel Gene Origination, Protein Family Evolution |

| GenomeDelta [25] | Computational Tool | Identifies sample-specific sequences, such as recent TE invasions, without a pre-defined repeat library. | Transposon Dynamics |

| Drosophilid Trio (D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia) [29] | Experimental Model | A closely related group with diverse ecologies; ideal for comparative transcriptomics and tracing recent evolutionary changes. | All Mechanisms |

| Polyploid Plants (e.g., Wheat, Cotton, Lily) [24] | Experimental Model | Systems where whole-genome duplication and subsequent TE activity drive rapid genome restructuring and evolution. | Transposon Dynamics, Protein Family Evolution |

Integrated Signaling in Genomic Evolution

The following diagram synthesizes the interactions between the major mechanisms discussed, illustrating how they collectively contribute to genome evolution and phenotypic diversity.

Sex-biased gene expression represents a fundamental mechanism underlying biological differences between males and females, serving as a crucial evolutionary innovation that enables sexual dimorphism while maintaining a largely identical genome. In aquatic species, this phenomenon exhibits remarkable diversity, reflecting the extraordinary variety of reproductive strategies and sexual systems that have evolved in marine and freshwater environments. Teleost fishes, in particular, display the most diverse array of sex determination systems among vertebrates, ranging from strict genetic determination to environmental sex determination and sequential hermaphroditism [30] [31]. This diversity makes aquatic species exceptionally valuable models for investigating the evolutionary dynamics of sex-biased gene expression across different phylogenetic scales and ecological contexts.

The study of sex-biased gene expression has been revolutionized by the advent of high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies, which enable comprehensive transcriptomic profiling without requiring prior genomic information [30] [32]. This technological advancement has been particularly transformative for research on non-model aquatic organisms, many of which possess significant economic and ecological importance but lack well-annotated reference genomes. By leveraging comparative transcriptomics, researchers can now identify sex-biased genes and pathways across multiple species, tissues, and developmental stages, providing unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms governing sexual development, reproduction, and phenotypic dimorphism in aquatic animals [33] [34].

This case study examines current research on the evolution of sex-biased gene expression in aquatic species, with a particular focus on finfishes that exhibit sexual size dimorphism. We integrate findings from multiple transcriptomic investigations to identify conserved and lineage-specific patterns, analyze the relationship between gene expression evolution and protein sequence adaptation, and explore the methodological frameworks that enable robust comparative analyses. Through this synthesis, we aim to illuminate both the fundamental principles and practical applications of this rapidly advancing field.

Comparative Analysis of Sex-Biased Gene Expression Across Species

Patterns of Sexual Size Dimorphism and Transcriptomic Divergence

Aquatic fishes exhibit remarkable diversity in sexual size dimorphism (SSD), with some species displaying female-biased size dimorphism while others show male-biased growth patterns. Recent comparative transcriptomic studies have sought to identify the gene expression underpinnings of these phenotypic differences across multiple species. A comprehensive investigation analyzed four fish species with significant SSD: loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) and half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis) exhibiting female-biased SSD, and yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) displaying male-biased SSD [33].

Table 1: Sexual Size Dimorphism and Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in Four Fish Species

| Species | Sexual Size Dimorphism | Female:Male Weight Ratio | DEGs in Brain | DEGs in Muscle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loach | Female-biased | 1.96:1 | 1,132 | 1,108 |

| Half-smooth tongue sole | Female-biased | 3.5:1 | 1,290 | 1,102 |

| Yellow catfish | Male-biased | 1:9.57 | 4,732 | 4,266 |

| Nile tilapia | Male-biased | Male-biased (exact ratio not specified) | 748 | 192 |

This comparative analysis revealed substantial variation in the number of sex-biased genes across species and tissues. Yellow catfish, which exhibits the most pronounced SSD (with males approximately 9.57 times heavier than females), also showed the highest number of DEGs in both brain (4,732) and muscle (4,266) tissues [33]. This correlation suggests that the extent of transcriptomic divergence between sexes may reflect the degree of phenotypic dimorphism. Interestingly, the number of DEGs was generally higher in brain tissue compared to muscle across most species, indicating that neural regulation may play a particularly important role in establishing and maintaining sexual dimorphism.

Taxonomic Distribution and Evolutionary Conservation

The evolutionary conservation of sex-biased gene expression remains an active area of investigation. Research on crimson seabream (Parargyrops edita) identified 11,676 unigenes differentially expressed between males and females, with 9,335 female-biased and 2,341 male-biased genes [30]. Similarly, a study on snakeskin gourami (Trichopodus pectoralis) revealed 11,625 unigenes overexpressed in ovaries and 16,120 overexpressed in testes during juvenile development [32]. These findings highlight the extensive transcriptomic reprogramming underlying sexual differentiation in teleosts.

However, broader evolutionary comparisons suggest limited conservation of specific sex-biased genes across deep phylogenetic divides. A micro-evolutionary study of closely related mouse taxa found rapid evolutionary turnover in sex-biased gene expression, particularly in somatic tissues [35]. This rapid turnover was coupled with signatures of adaptive protein evolution, suggesting that positive selection may drive divergence in sex-biased expression patterns. Similarly, investigations in human populations have demonstrated that sex-biased gene expression is highly variable and mostly population-specific, with evidence of recent adaptive evolution in sex-specific regulatory variants [36]. These findings challenge the notion of a conserved core set of sex-biased genes maintained across vertebrates and highlight the importance of considering evolutionary timescales when assessing conservation patterns.

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Frameworks

Standardized RNA-Seq Workflows for Non-Model Organisms

Transcriptomic analysis of sex-biased gene expression in aquatic species typically follows a standardized workflow optimized for non-model organisms. The general methodology encompasses sample collection, RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, assembly, annotation, and differential expression analysis [30] [33] [31]. For species lacking reference genomes, de novo transcriptome assembly using software such as Trinity becomes essential [30] [34]. Quality assessment metrics including N50 values, BUSCO completeness scores, and back-mapping rates of reads to the assembly ensure the generation of robust transcriptomic resources.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols in Transcriptomic Studies of Aquatic Species

| Protocol Step | Standard Methodology | Purpose | Quality Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Tissue dissection (gonads, brain, muscle); immediate freezing in liquid nitrogen | Preserve in vivo gene expression patterns | Multiple biological replicates (typically 3+); uniform developmental stages |

| RNA Extraction | Trizol/chloroform method | Isolate high-quality total RNA | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥7; agarose gel electrophoresis |

| Library Preparation | TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit; poly-A selection | Construct sequencing libraries with minimal bias | Fragment analyzer assessment; accurate quantification |

| Sequencing | Illumina platforms (HiSeq 2500/4000, NovaSeq); 150bp paired-end reads | Generate high-throughput transcriptome data | Q30 scores >80%; minimum 20 million reads per sample |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2; ∣log~2~(fold change)∣ >1; FDR <0.05 | Identify statistically significant sex-biased genes | Normalization for library size; multiple testing correction |

Functional annotation of assembled transcripts represents a critical step in extracting biological meaning from sequence data. This typically involves sequence similarity searches against multiple databases including NCBI non-redundant (NR), Swiss-Prot, Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG) [30] [34] [31]. Enrichment analyses then identify biological processes, molecular functions, and pathways that are overrepresented among sex-biased genes, providing insights into their potential functional roles.

Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Evolutionary Inference

The application of phylogenetic comparative methods (PCMs) has become increasingly important for understanding the evolutionary dynamics of sex-biased gene expression. These approaches explicitly account for shared evolutionary history among species, which can confound traditional statistical analyses that assume independent data points [37]. Recent methodological advances have enabled researchers to model gene expression evolution using frameworks such as Brownian motion (BM) and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) processes, which describe different modes of trait evolution [37].

Assessment of model adequacy has emerged as a crucial component of phylogenetic analyses of gene expression data. A comprehensive evaluation of phylogenetic models found that Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models, which incorporate stabilizing selection toward optimal expression values, were preferred for 66% of gene-tissue combinations across eight datasets [37]. However, the study also revealed that for 39% of gene-tissue combinations, even the best-fitting model performed poorly according to statistical adequacy tests, highlighting the need for continued methodological refinement in this field.

Molecular Pathways and Conserved Genetic Networks

Conserved Sex-Determination and Differentiation Pathways

Despite the rapid evolutionary turnover of specific sex-biased genes, certain core molecular pathways appear to be recurrently involved in sex determination and differentiation across diverse aquatic species. Transcriptomic studies in multiple fish species have consistently identified involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which regulates reproduction and growth through complex neuroendocrine signaling [33]. Key genes and pathways frequently associated with sex-biased expression include those involved in steroid hormone synthesis, gonad development, and growth regulation.

Research on protogynous hermaphroditic sparids (common pandora Pagellus erythrinus and red porgy Pagrus pagrus) has revealed a common suite of well-conserved molecular players that maintain either sex identity in these species capable of natural sex change [31]. Similarly, studies in crimson seabream have identified multiple sex-related genes including zps, amh, gsdf, sox4, and cyp19a, as well as pathways such as MAPK signaling and p53 signaling [30]. The conservation of these pathways across diverse reproductive systems suggests their fundamental importance in vertebrate sexual development.

Tissue-Specific Patterns of Sex-Biased Expression

Comparative transcriptomic analyses have revealed striking differences in sex-biased gene expression patterns between tissues. A seminal study in mice demonstrated that sex-biased expression evolves more rapidly in somatic tissues compared to gonads, with extensive evolutionary turnover and mosaicism across tissues [35]. This tissue-specific variation challenges binary classifications of sexual differentiation and suggests a more complex model where sex-biased gene expression is context-dependent and evolutionarily labile.

In fish, gonadal tissues typically exhibit the most extensive sex-biased expression, reflecting their direct role in reproductive function. For instance, in snakeskin gourami, the top female-biased genes in ovarian tissue included rdh7, dnajc25, ap1s3, zp4, and polb, while male-biased genes in testis included vamp3, nbl1, dnah2, ccdc11, and nr2e3 [32]. Brain tissues also show significant sex-biased expression, though typically fewer genes are differentially expressed compared to gonads [33]. This tissue-specificity underscores the importance of analyzing multiple tissues to obtain a comprehensive understanding of sexual dimorphism at the molecular level.

Figure 1: Molecular Regulation of Sexual Differentiation in Fish. This pathway illustrates the integration of environmental and genetic factors through the neuroendocrine system to ultimately produce sexually dimorphic phenotypes through changes in gene expression.

Research Tools and Resource Development

The expansion of transcriptomic studies on aquatic species has stimulated the development of specialized databases and resources that facilitate comparative analyses. The aquatic animal transcriptome map database (dbATM) represents one such resource, providing de novo assemblies, functional annotations, and comparative analysis for more than twenty non-model aquatic organisms [34]. This database integrates transcriptomic information from publicly available sources and applies standardized computational pipelines to enable cross-species comparisons.

These resources typically include homologous gene groups, which allow researchers to identify orthologous genes across multiple species and investigate the evolution of sex-biased expression in a phylogenetic context. For example, dbATM has identified 21 homologous genes shared across at least 17 aquatic species, including essential genes such as tRNA synthetases (yars, cars) and nuclear pore proteins (nup98, nup188) [34]. The conservation of these genes across diverse lineages suggests their fundamental cellular functions, while their expression patterns may reveal species-specific adaptations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Transcriptomic Studies of Sex-Biased Expression

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TRIzol Reagent | Total RNA isolation from multiple tissue types | Maintains RNA integrity while disrupting cells and denaturing proteins |

| DNase I | Removal of genomic DNA contamination | Critical for accurate RNA-seq results; typically included in cleanup kits |

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | mRNA enrichment via poly-A tail selection | Essential for mRNA-seq library preparation |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Kit | Library preparation for Illumina sequencing | Incorporates dUTP for strand specificity |

| - Illumina Sequencing Platforms | High-throughput sequencing | HiSeq 2500/4000 for moderate throughput; NovaSeq for high throughput |

| Trinity Software | De novo transcriptome assembly | Critical for non-model organisms without reference genomes |

| DESeq2 R Package | Differential expression analysis | Uses negative binomial distribution to model count data |

| BLAST Suite | Sequence similarity searching | Annotates assembled transcripts against reference databases |

| OrthoMCL | Homologous gene group identification | Enables comparative genomics across multiple species |

This toolkit encompasses both wet-lab reagents and computational tools that have become standard in the field. The integration of experimental and computational approaches is essential for generating robust, reproducible data that enables meaningful evolutionary inferences. As sequencing technologies continue to advance, these methodologies are likely to be refined, potentially incorporating single-cell approaches to resolve cell-type-specific patterns of sex-biased expression and long-read sequencing to improve transcriptome assembly.

Comparative transcriptomic analyses have fundamentally advanced our understanding of sex-biased gene expression evolution in aquatic species. The emerging picture is one of remarkable diversity and evolutionary lability, with rapid turnover of specific sex-biased genes even as core molecular pathways remain conserved. The development of specialized databases and standardized analytical pipelines has enabled increasingly sophisticated comparative studies that reveal both shared and lineage-specific aspects of sexual dimorphism.

Future research in this field will likely focus on several promising directions. First, integrating genomic and transcriptomic data will help distinguish the relative contributions of cis-regulatory evolution versus trans-acting factors to sex-biased expression patterns. Second, single-cell RNA-sequencing approaches promise to resolve cell-type-specific patterns of sex-biased expression, particularly in heterogeneous tissues like the brain and gonads. Third, experimental manipulation of candidate genes, perhaps using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, will enable functional validation of hypotheses generated from correlative transcriptomic studies. Finally, expanding taxonomic sampling to include more diverse reproductive systems, such as sequential hermaphrodites and unisexual species, will provide additional evolutionary insights into the plasticity of sexual development.

As these methodological advances converge with growing genomic resources for non-model aquatic species, we anticipate rapid progress in understanding the evolutionary forces that shape sex-biased gene expression and its consequences for phenotypic diversity, adaptation, and speciation in aquatic environments.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Transcriptomic Analysis of Sex-Biased Gene Expression. This diagram outlines the standard pipeline from sample collection through evolutionary inference, highlighting the integration of experimental and computational approaches.

A Practical Toolkit: From Bulk RNA-seq to Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics

Transcriptomic technologies have revolutionized biological research, providing unprecedented insights into gene expression. This guide objectively compares the performance of microarray, RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), and spatial transcriptomics, with a specific focus on their applications in cross-species comparative research.

Transcriptomic technologies have evolved from bulk expression profiling to high-resolution spatial analysis at the single-cell level. Microarrays, a hybridization-based technology, were the primary platform for transcriptomics for over a decade. They measure fluorescence intensity of predefined transcripts through complementary probe binding [38]. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) utilizes next-generation sequencing to count reads that can be aligned to a reference sequence, providing a broader dynamic range and the ability to detect novel transcripts [39] [38].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analyzes gene expression profiles of individual cells from both homogeneous and heterogeneous populations, enabling the identification of rare cell subtypes and gene expression variations that would otherwise be overlooked in bulk analyses [40]. Spatial transcriptomics represents a pivotal advancement that facilitates the identification of RNA molecules in their original spatial context within tissue sections, preserving architectural information that is lost in other single-cell techniques [40] [41].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Microarray vs. RNA-seq

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of microarray and RNA-seq technologies. The table below summarizes key comparative findings from experimental studies:

Table 1: Performance comparison between microarray and RNA-seq

| Performance Metric | Microarray | RNA-seq | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Limited [38] | Broader [39] [38] | Superior detection of low-abundance transcripts and highly expressed genes [39] |

| Transcript Discovery | Restricted to predefined probes | Comprehensive; identifies novel transcripts, isoforms, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs [38] | RNA-seq detects non-coding RNAs (miRNA, lncRNA) and genetic variants missed by microarrays [39] |

| Specificity & Background | Issues with cross-hybridization and non-specific hybridization [39] | High specificity through direct sequencing | Simplified data interpretation by avoiding probe redundancy and annotation issues [39] |

| Concentration Response Modeling | Effectively identifies functions, pathways, and transcriptomic points of departure (tPoD) [38] | Identifies more DEGs but produces equivalent tPoD values and pathway enrichment results [38] | Both platforms yielded similar tPoD values for cannabinoids (CBC and CBN) in toxicogenomic studies [38] |

| Cost & Accessibility | Lower cost, smaller data size, well-established analysis software and databases [38] | Higher cost, complex data storage and analysis, but becoming more accessible [39] [38] | Microarray remains a viable choice for traditional applications like mechanistic pathway identification [38] |

Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics Advantages

scRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics offer distinct advantages for resolving cellular heterogeneity and tissue architecture:

Table 2: Advantages of advanced transcriptomic technologies

| Technology | Key Advantages | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | Reveals cellular diversity, identifies rare cell subtypes, reconstructs cell trajectories and developmental lineages [40] | Characterizing complex populations in cancer, immunology, neurology, and developmental biology [40] [42] |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Maps gene expression within intact tissue architecture, identifies spatially restricted cell subpopulations and co-enrichments [41] [43] | Studying tissue organization, tumor microenvironments, developmental processes, and plant biology [41] [43] |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Microarray Protocol (GeneChip PrimeView)

Total RNA samples are processed using the GeneChip 3' IVT PLUS Reagent Kit. Briefly, double-stranded cDNA is synthesized from total RNA using a T7-linked oligo(dT) primer. Subsequently, complementary RNA (cRNA) is synthesized through in vitro transcription (IVT) with biotinylated nucleotides. The biotin-labeled cRNA is fragmented and hybridized onto microarray chips. After hybridization, chips are stained, washed, and scanned to produce image files that are preprocessed to generate cell intensity files for analysis [38].

RNA-seq Protocol (Illumina Stranded mRNA Prep)

Sequencing libraries are prepared from total RNA. Messenger RNAs with polyA tails are purified using oligo(dT) magnetic beads, then fragmented and denatured. First-strand cDNA is synthesized by reverse transcription of the RNA fragments, followed by second-strand synthesis to generate blunt-ended, double-stranded cDNA. After adapter ligation and library amplification, the libraries are sequenced on platforms such as Illumina HiSeq or NovaSeq to produce paired-end reads [38] [4].

Cross-Species Transcriptomics with Seq2Fun

For non-model organisms with limited genomic resources, the Seq2Fun algorithm provides a robust solution for comparative analyses. This method translates transcriptomic sequencing reads from any input species into all possible short amino acid sequences, which are then mapped onto a universal database (EcoOmicsDB) housing millions of protein-coding genes from hundreds of species. This approach identifies functional homologs without relying on de novo transcriptome assembly, facilitating cross-species investigations in ecological and evolutionary contexts [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for transcriptomic studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Isolation of polyA-tailed mRNA from total RNA | Library preparation for RNA-seq and scRNA-seq [38] |

| Biotinylated UTP/CTP | Labeling of cRNA for detection | In vitro transcription for microarray analysis [38] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tagging individual molecules to correct for amplification bias | High-resolution single-cell and spatial transcriptomics [44] [43] |

| Spatial Barcoded Arrays | Capturing mRNA with positional information | Microarray-based spatial transcriptomics (Array-seq) [44] |

| DNase I | Digestion of contaminating genomic DNA | RNA purification protocols across all platforms [38] [4] |

Technology Workflow and Integration

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows and relationships between the major transcriptomic technologies.

Application in Cross-Species Comparative Research

Cross-species comparative transcriptomics leverages these technologies to understand evolutionary conservation and diversity. A compelling application is found in studying male infertility, where researchers compared scRNA-seq datasets from testes of humans, mice, and fruit flies. This approach identified conserved genes involved in post-transcriptional regulation, meiosis, and energy metabolism during spermatogenesis. Gene knockout experiments of candidate genes in fruit flies confirmed functional conservation, with mutations in three genes resulting in reduced male fertility [42].

In ecological toxicology, the EcoToxChip project utilized RNA-seq to profile transcriptomic responses to chemicals across six vertebrate species, including model organisms and ecological relevant species. This database enables comparative analysis of baseline and differential transcriptomic changes across species-life stage-chemical combinations, identifying commonly differentially expressed genes like CYP1A1 and conserved pathways such as xenobiotic metabolism by cytochrome P450 [4].

Another study on sea urchins performed a four-species comparative transcriptome analysis to investigate neurotransmitter system genes in early embryos. By analyzing RNA-seq data across development stages, researchers found that while specific receptors showed consistent expression across species, many components exhibited considerable interspecies variability, revealing evolutionary plasticity in these developmental systems [45].