Computational Simulation of Genetic Code Robustness: From Evolutionary Insights to Therapeutic Applications

This article explores the critical role of computational simulation in quantifying the robustness of the genetic code and its profound implications for biomedical research.

Computational Simulation of Genetic Code Robustness: From Evolutionary Insights to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of computational simulation in quantifying the robustness of the genetic code and its profound implications for biomedical research. We examine the foundational paradox of the genetic code's extreme evolutionary conservation despite its demonstrated flexibility, as revealed by synthetic biology. The review covers a spectrum of methodological approaches, from foundational models for predicting gene expression to machine learning frameworks for inferring genealogies and deconvoluting cellular data. A significant focus is placed on benchmarking platforms that identify performance gaps and optimization strategies to enhance model accuracy and resilience against technical noise. By synthesizing insights from recent large-scale benchmarking studies and advanced algorithms, this work provides researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for leveraging computational simulations to understand genetic stability, predict perturbation outcomes, and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Genetic Code Paradox: Unraveling Conservation and Flexibility

Genetic code robustness is a fundamental property of the nearly universal biological translation system that defines its resilience to perturbations, primarily mutations and translation errors. This robustness is not merely a structural feature but a dynamic property that profoundly influences evolutionary trajectories. Within the context of computational simulation research, understanding and quantifying this robustness provides critical insights into protein evolvability—the capacity of evolutionary processes to generate adaptive functional variation [1]. The standard genetic code exhibits exceptional error tolerance, with studies demonstrating that only approximately one in a million alternative code configurations surpasses its ability to minimize the deleterious effects of single-nucleotide mutations [2]. This application note details the quantitative frameworks, computational methodologies, and experimental protocols for investigating genetic code robustness and its relationship to evolutionary adaptability, providing researchers with standardized approaches for this emerging field.

Quantitative Frameworks and Data Presentation

Core Metrics for Quantifying Genetic Code Robustness

Table 1: Fundamental Metrics for Assessing Genetic Code Robustness

| Metric Name | Definition | Calculation Method | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| μ-Robustness | Unalterability of phenotypes against single-base mutations [3] | r_i = Σu_ij / (9n_i) where u_ij = number of single-base mutants of codon j in set i that preserve phenotype, n_i = codons in set i [3] |

Probability that a random point mutation does not change the encoded amino acid or stop signal |

| s-Robustness | Resistance against nonsense mutations [3] | Proportion of mutations that avoid creating premature stop codons | Preserves protein length and integrity against truncations |

| Physicochemical Robustness | Preservation of amino acid properties after mutation [2] [1] | Average similarity of amino acid pairs connected by single-nucleotide mutations using polarity, volume, charge metrics | Minimizes disruptive changes to protein structure and function |

| Evolvability Index | Capacity to generate adaptive variation [2] | Measured via landscape smoothness, number of fitness peaks, accessibility of high-fitness genotypes in sequence space | Quantifies potential for evolutionary exploration and adaptation |

Empirical Data from Alternative Code Analysis

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Standard vs. Alternative Genetic Codes

| Genetic Code Type | Relative Robustness | Evolvability Assessment | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Genetic Code | High (top 0.0001% of random codes) [2] | Enhanced: produces smoother adaptive landscapes with fewer peaks [2] | 6 combinatorially complete protein fitness landscapes [2] |

| High-Robustness Alternatives | Higher than standard code in thousands of variants [1] | Variable: some further enhance evolvability, effect is protein-specific [1] | Computational analysis of 100,000 rewired codes [1] |

| 61-Codon Compressed Codes | Reduced (eliminated 3 codons) [4] | Viable but with fitness costs (~60% slower growth in Syn61 E. coli) [4] | Synthetic biology implementation in recoded organisms |

| Stop Codon Reassigned Codes | Context-dependent | Functional: natural examples show evolutionary viability [4] | Natural variants in mitochondria, ciliates; engineered E. coli strains [4] |

Computational Methodologies

Code Rewiring Simulation Protocol

Purpose: Systematically evaluate robustness and evolvability properties of alternative genetic code configurations.

Workflow:

- Code Space Definition: Generate alternative genetic codes while maintaining the degeneracy structure of the standard code (20 amino acids, stop codons, synonymous codon blocks) [1].

- Mutation Modeling: Implement single-nucleotide substitution model with capacity to incorporate transition-transversion bias and GC-AT content bias [3].

- Robustness Calculation: For each rewired code, compute μ-robustness and physicochemical robustness metrics (Table 1).

- Landscape Mapping: Translate DNA sequence space to protein space using each alternative code, applying empirical fitness data from deep mutational scanning experiments [2] [1].

- Topography Analysis: Quantify landscape features including:

- Number and height of fitness peaks

- Ruggedness (prevalence of fitness valleys)

- Accessibility of high-fitness regions from different starting points [2]

Implementation Considerations:

- Sample >10,000 alternative codes for statistical power [1]

- Use unbiased codon usage assumption unless modeling specific organisms [3]

- Validate with multiple physicochemical property scales or dataset-specific amino acid exchangeabilities [1]

Adaptive Landscape Analysis

Protocol for Empirical Landscape Construction:

Data Acquisition: Utilize combinatorially complete deep mutational scanning datasets that measure quantitative phenotypes for all amino acid combinations at multiple protein sites [2]. Suitable datasets include:

Network Representation:

- Represent each DNA sequence as a node

- Connect nodes with edges if they differ by a single nucleotide mutation

- Translate sequences via genetic code to amino acid sequences

- Annotate nodes with experimentally measured fitness values [1]

Evolvability Quantification:

- Short-term: Calculate fraction of beneficial mutations in immediate mutational neighborhood

- Long-term: Perform simulated adaptive walks from multiple starting points

- Global: Analyze network connectivity between high-fitness genotypes [2]

Experimental Validation Protocols

Synthetic Organism Engineering

Objective: Empirically test robustness and evolvability predictions in recoded organisms.

Methods:

- Codon Compression:

Codon Reassignment:

Adaptation Tracking:

- Serial passage of recoded organisms under selective pressures

- Genome sequencing to identify compensatory mutations

- Fitness measurements relative to wild-type controls [4]

In Vitro Robustness Assessment

High-Throughput Experimental Protocol:

- Library Design: Create mutant libraries covering single-nucleotide variants of target genes

- Functional Screening: Use deep mutational scanning (e.g., phage display, yeast display) to quantify fitness effects of all possible point mutations [2]

- Code-Specific Analysis: Group mutations by amino acid changes and calculate:

- Average fitness effect of code-allowed mutations

- Fraction of beneficial mutations accessible via single-nucleotide changes

- Comparison to theoretical robustness predictions [1]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Genetic Code Robustness Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorially Complete Datasets | Empirical fitness landscape construction | GB1, ParD3, ParB deep mutational scanning data [2] |

| Recoded Organisms | Experimental validation of alternative codes | Syn61 E. coli (61-codon); Ochre strains (stop codon reassigned) [4] |

| Orthogonal Translation Systems | Incorporation of noncanonical amino acids | PylRS/tRNAPyl, other aaRS/tRNA pairs for genetic code expansion [5] |

| Pathway Enzymes for ncAA Biosynthesis | In situ production of noncanonical amino acids | L-threonine aldolase (LTA), threonine deaminase (LTD), aminotransferases (TyrB) [5] |

| Deep Mutational Scanning Platforms | High-throughput fitness measurement | Phage display, yeast display, bacterial selection systems with NGS readout [2] |

Integrated Analysis Framework

The integrated computational and experimental framework presented enables systematic analysis of how genetic code robustness shapes evolutionary adaptability. The standard genetic code demonstrates remarkable but not exceptional robustness among possible alternatives, with its key advantage being the general enhancement of protein evolvability through smoother adaptive landscapes [2] [1]. This relationship, however, exhibits protein-specific variation, indicating that optimality must be considered across diverse functional contexts.

For computational researchers, these protocols provide standardized methods for simulating code robustness and its evolutionary consequences. The quantitative metrics enable direct comparison between theoretical predictions and empirical measurements, facilitating deeper understanding of how genetic code structure constrains and directs evolutionary exploration. Future directions include expanding analysis to incorporate non-canonical amino acids, modeling organism-specific codon usage biases, and integrating multi-scale evolutionary simulations from molecular to population levels.

The standard genetic code (SGC) represents one of the most fundamental and universal information processing systems in biology, mapping 64 triplet codons to 20 canonical amino acids and stop signals with remarkable fidelity across approximately 99% of known life. This extreme conservation persists despite compelling evidence from both synthetic biology and natural observations that the code is inherently flexible and can be fundamentally rewritten while maintaining biological viability. This contradiction between demonstrated flexibility and evolutionary stasis constitutes the conservation paradox, presenting a significant challenge to evolutionary biology and offering rich opportunities for computational investigation.

Recent advances in synthetic biology have dramatically overturned the historical view of the genetic code as a "frozen accident." Engineering achievements include the creation of Syn61, an Escherichia coli strain with a fully synthetic genome that uses only 61 of the 64 possible codons, demonstrating viability despite systematic recoding of over 18,000 individual codons. Furthermore, researchers have developed strains that reassign all three stop codons for alternative functions, repurposing termination signals to incorporate non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs). Natural genomic surveys analyzing over 250,000 genomes have identified more than 38 natural genetic code variations across diverse biological lineages, including mitochondrial code variations, nuclear code changes in ciliates, and the remarkable CTG clade where Candida species reassign CTG from leucine to serine. These observations confirm that genetic code changes are not only possible but have occurred repeatedly throughout evolutionary history [4].

Computational Frameworks for Analyzing Code Robustness

Graph-Theoretic Models of Genetic Code Structure

Computational analysis of the genetic code employs sophisticated graph-based approaches to quantify its robustness against point mutations. In this framework, all possible point mutations are represented as a weighted graph ( G(V,E,w) ) where:

- ( V = \Sigma^\ell ) represents all possible ℓ-letter words over alphabet Σ (typically {A, C, G, T/U})

- ( E ) contains edges connecting codons differing by exactly one nucleotide

- ( w: E \rightarrow P ) assigns weights to edges based on mutation probabilities [6]

The robustness of a genetic code can be quantified through conductance measures, which evaluate how genetic code organization minimizes the negative effects of point mutations. For a subset S of V (representing codons encoding the same amino acid), the set-conductance is defined as:

[ \phi(S) = \frac{w(E(S,\bar{S}))}{\sum_{c \in S, (c,c') \in E} w((c,c'))} ]

where ( w(E(S,\bar{S})) ) represents the sum of weights of edges crossing from S to its complement. The set-robustness is then defined as ( \rho(S) = 1 - \phi(S) ), representing synonymous mutations that do not alter the encoded amino acid [6].

Table 1: Conductance Values for the Standard Genetic Code Under Different Weighting Schemes

| Weighting Scheme | Average Conductance (( \Phi )) | Average Robustness (( \bar{\rho} )) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| All weights = 1 | ~0.81 | ~0.19 | Uniform mutation probability |

| Optimized weights | ~0.54 | ~0.46 | Position-dependent weights [6] |

| Wobble-effect weights | - | - | Reflects biological translation |

Evolutionary Optimization of Genetic Code Robustness

Computational studies using evolutionary optimization algorithms demonstrate that the structure of the standard genetic code approaches optimal configurations for minimizing the negative effects of point mutations. These analyses reveal that:

- Mutations in the third codon position have least influence on robustness, corresponding to the biological wobble effect

- Mutations in the first base, and especially the second base of a codon, have dramatically larger impacts on robustness

- Random code tables evolved under selective pressure for robustness converge toward structures remarkably similar to the standard genetic code [6]

These findings strongly support the hypothesis that robustness against point mutations served as a significant evolutionary pressure shaping the standard genetic code, though it likely represents only one of multiple competing optimization parameters.

Experimental Evidence and Natural Variations

Documented Natural Code Variations

Natural ecosystems have conducted evolutionary experiments in genetic code modification, with genomic surveys documenting numerous variations across the tree of life. These natural variations demonstrate both the feasibility and constraints of genetic code evolution.

Table 2: Documented Natural Variations in the Genetic Code

| Organism/System | Codon Reassignment | Molecular Mechanism | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebrate mitochondria | AGA/AGG → stop UGA → tryptophan | tRNA adaptation | Energy-producing organelles |

| Ciliated protozoans | UAA/UAG → glutamine | Modified termination machinery | Nuclear code in diverse aquatic environments |

| Candida species (CTG clade) | CTG → serine | tRNA evolution with ambiguous intermediate | Pathogenic and free-living fungi |

| Mycoplasma and other bacteria | UGA → tryptophan | Genome reduction | Multiple independent origins |

| Various mitochondria | AUA → isoleucine → methionine | tRNA modification | Convergent evolution |

The pattern of natural variations reveals important constraints on genetic code evolution. Most changes affect rare codons in the organisms that reassign them, minimizing the number of genes requiring compatibility with the new assignment. Stop codon reassignments are particularly common, potentially because they affect fewer genes than sense codon changes. The existence of ambiguous intermediate states, where a single codon can be translated as multiple amino acids, provides an evolutionary bridge that enables gradual rather than catastrophic code transitions [4].

Synthetic Biology Demonstrations of Code Flexibility

Laboratory achievements in synthetic biology provide even more compelling evidence of genetic code flexibility, demonstrating that what was once considered impossible is merely technically challenging:

- Syn61: A recoded E. coli strain with all 18,000+ instances of two sense codons and one stop codon replaced throughout its 4-megabase synthetic genome

- Ochre strains: E. coli strains that reassign all three stop codons for alternative functions, including incorporation of non-canonical amino acids

- Fitness analysis: Detailed genetic analysis reveals that performance costs in recoded organisms stem primarily from pre-existing suppressor mutations and genetic interactions rather than the codon reassignments themselves [4]

These synthetic biology achievements demonstrate that the genetic code is not frozen by intrinsic biochemical constraints but rather by the accumulation of historical contingencies that can be systematically overcome.

Application Notes: Computational Simulation of Code Robustness

Protocol for Conductance-Based Robustness Analysis

Objective: Quantify the robustness of genetic code configurations against point mutations using graph conductance measures.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Genetic code table (standard or alternative)

- Mutation probability matrix (position-specific and/or nucleotide-specific)

- Graph analysis software (Python with NetworkX or custom C++ implementation)

- Optimization framework (evolutionary algorithms for weight optimization)

Procedure:

- Graph Construction:

- Represent each codon as a vertex in graph G

- Connect codons differing by single nucleotides with weighted edges

- Assign weights based on mutation probabilities (default: uniform weights)

Partition Definition:

- Cluster codons into sets representing amino acid assignments

- Include stop codons as separate partitions

Conductance Calculation:

- For each amino acid set S, compute ( \phi(S) ) using the weighted formula

- Calculate average conductance ( \bar{\Phi}(C_k) ) across all sets

- Compute average robustness ( \bar{\rho}(Ck) = 1 - \bar{\Phi}(Ck) )

Optimization (Optional):

- Apply evolutionary algorithms to optimize edge weights

- Minimize average conductance through iterative weight adjustment

- Compare optimal weights to biological mutation patterns

Interpretation: Lower conductance values indicate superior robustness against point mutations. The standard genetic code exhibits significantly lower conductance (~0.54 with optimized weights) than random code tables, supporting the error-minimization hypothesis [6].

Workflow for Comparative Analysis of Alternative Codes

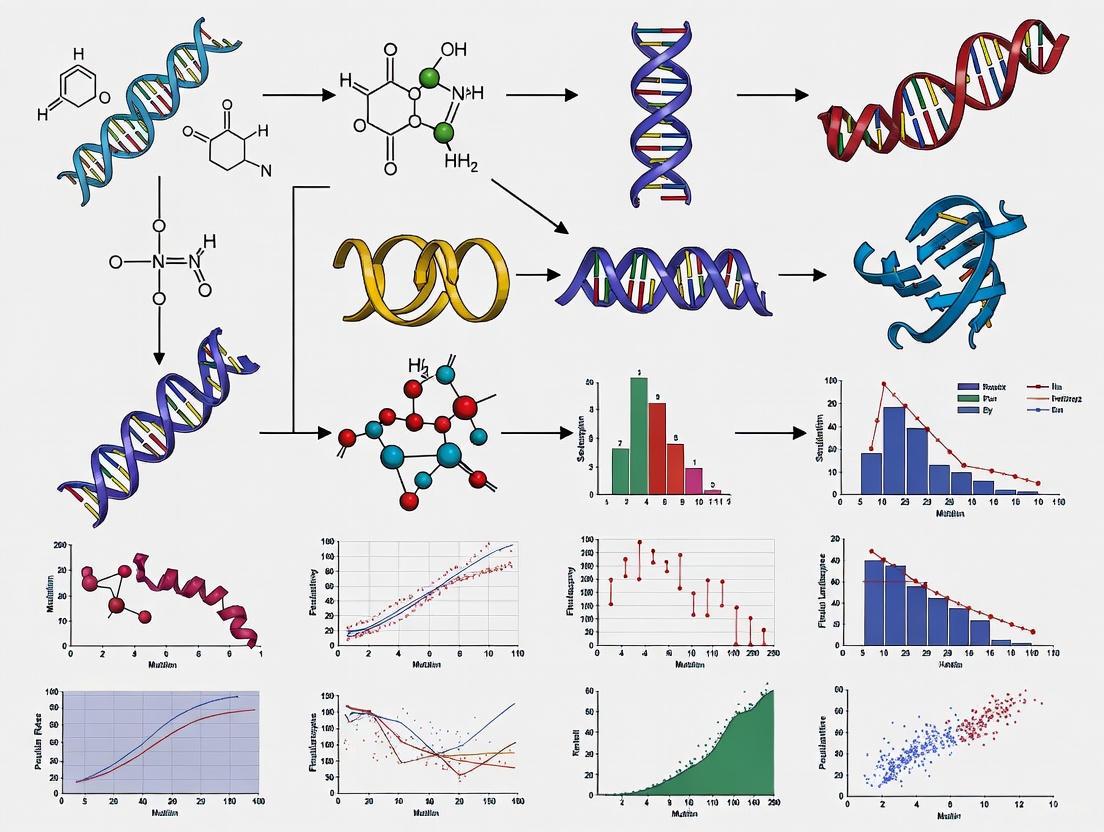

Diagram 1: Workflow for comparative analysis of genetic code variants.

Research Reagent Solutions for Code Manipulation Studies

Essential Materials for Genetic Code Expansion

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Genetic Code Expansion and Manipulation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal translation systems | PylRS/tRNAPyl, EcTyrRS/tRNATyr | Incorporation of ncAAs at specific codons | Requires matching aaRS/tRNA pairs |

| Non-canonical amino acids | p-iodophenylalanine, O-methyltyrosine, sulfotyrosine | Expanding chemical functionality of proteins | Membrane permeability can limit utility |

| Biosynthetic pathway enzymes | L-threonine aldolase, threonine deaminase, aminotransferases | In situ production of ncAAs from precursors | Reduces cost of ncAA supplementation |

| Recoded chassis organisms | Syn61 E. coli, C321.ΔA | Host strains with vacant codons for reassignment | Enable code expansion without competition |

| CRISPR-based genome editing | Cas9, base editors, prime editors | Introducing code changes throughout genomes | Essential for creating recoded organisms |

Platform for Integrated ncAA Biosynthesis and Incorporation

Recent advances address the "Achilles' heel" of genetic code expansion technology: the cost and membrane permeability of non-canonical amino acids. A robust platform now couples the biosynthesis of aromatic ncAAs with genetic code expansion in E. coli, enabling production of proteins containing ncAAs without expensive exogenous supplementation.

The platform employs a three-enzyme pathway:

- L-threonine aldolase: Catalyzes aldol reaction between glycine and aryl aldehydes

- L-threonine deaminase: Converts aryl serines to aryl pyruvates

- Aminotransferase: Produces final ncAAs from aryl pyruvate precursors

This system successfully produces 40 different aromatic amino acids in vivo from corresponding aromatic aldehydes, with 19 incorporated into target proteins using orthogonal translation systems. The platform demonstrates versatility through production of macrocyclic peptides and antibody fragments containing ncAAs [5].

Diagram 2: Integrated pathway for ncAA biosynthesis and incorporation.

Correlation Between Code Robustness and Protein Evolvability

Emerging research reveals a crucial relationship between genetic code robustness and protein evolvability. While these properties might initially appear contradictory, computational analysis demonstrates they are positively correlated. Robustness to mutations creates extensive networks of sequences with similar functions that differ by few mutations. These networks provide evolutionary exploration spaces where some neighboring sequences possess novel or adaptive functions [1].

Empirical validation using deep mutational scanning datasets shows that:

- More robust genetic codes confer greater protein evolvability on average

- The standard genetic code exhibits substantial but not exceptional robustness

- Thousands of alternative genetic codes show greater theoretical robustness

- The relationship between robustness and evolvability is protein-specific and varies across different protein functions

This context-dependent relationship may explain the conservation paradox: the standard genetic code may represent a compromise solution that provides sufficient robustness and evolvability across diverse biological contexts rather than optimal performance for specific functions [1].

Discussion: Resolving the Paradox

The conservation paradox of the genetic code—extreme universality despite demonstrated flexibility—can be understood through multiple complementary explanations:

Network Effects and Evolutionary Constraints

The genetic code represents a deeply integrated information system where changes reverberate throughout cellular networks. While individual codon reassignments are technically possible, their implementation requires coordinated evolution of:

- tRNA identity and modification systems

- Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase specificity

- Translation termination machinery

- mRNA regulatory elements

- Genome-wide codon usage patterns

This deep integration creates powerful network effects that stabilize the existing code despite potential advantages of alternatives. Additionally, most beneficial mutations that might drive code evolution would need to occur simultaneously across multiple system components, representing a significant evolutionary hurdle [4].

Compromise Optimization Across Multiple Parameters

Computational analyses suggest the standard genetic code represents a compromise optimization across multiple competing parameters:

- Robustness against point mutations

- Preservation of chemical similarity in mutated amino acids

- Error minimization during translation

- Evolving biosynthetic pathways of amino acids

- Historical contingency and evolutionary frozen accidents

No single parameter completely explains the code's structure, but together they create a fitness landscape where the standard genetic code represents a strong local optimum that is difficult to escape through gradual evolutionary processes [6] [1].

Implications for Synthetic Biology and Therapeutic Development

Understanding the conservation paradox informs practical applications in synthetic biology and therapeutic development:

- Industrial biotechnology: Engineered genetic codes can enhance productivity by eliminating regulatory conflicts and incorporating novel functionalities

- Therapeutic protein production: Recoded organisms provide biocontainment safeguards against horizontal gene transfer

- Genetic isolation: Alternative codes create functional barriers between natural and engineered organisms

- Expanded chemical functionality: Non-canonical amino acids enable novel protein therapeutics with enhanced properties

The STABLES system represents one application, using gene fusion strategies to link genes of interest to essential genes, thereby maintaining evolutionary stability of heterologous gene expression in synthetic systems [7].

The conservation paradox of the genetic code—extreme universality despite demonstrated flexibility—reveals fundamental principles of biological evolution. Computational simulations demonstrate the code's remarkable robustness against point mutations while synthetic biology confirms its extraordinary flexibility. Rather than a frozen accident, the standard genetic code appears optimized for multiple competing constraints, creating a local optimum that has persisted despite billions of years of evolutionary exploration. Ongoing research continues to unravel this central enigma of molecular biology while providing practical tools for biotechnology and therapeutic development through controlled genetic code expansion and manipulation.

The standard genetic code (SGC) is not a rigid framework but a dynamic system that exhibits remarkable flexibility across biological systems. This adaptability is evidenced by the existence of numerous naturally occurring deviant genetic codes and the successful engineering of expanded genetic codes in synthetic biology. From a computational simulation perspective, this flexibility can be quantified through two fundamental, yet antithetical, properties: robustness (the preservation of phenotypic meaning against mutations) and changeability (the potential for phenotypic alteration through mutation) [3].

These intrinsic properties of genetic codes have profoundly influenced their origin and evolution. The SGC appears finely balanced to minimize the impact of point mutations while retaining capacity for evolutionary adaptation. Computational analyses reveal that known deviant codes discovered in nature consistently represent paths of evolution from the SGC that significantly improve both robustness and changeability under specific biological constraints [3]. This framework provides a powerful lens through which to evaluate both natural variants and synthetic biological systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Genetic Codes in Computational Analysis

| Property | Definition | Computational Measure | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| μ-Robustness | Unalterability of phenotypes against single base mutations | ri = Σuij/(9ni) where uij is number of synonymous single base mutants [3] | Enhances survivability by protecting against deleterious mutations |

| s-Robustness | Resistance against nonsense mutations | Probability of mutation not creating stop codon [3] | Maintains functional polypeptide length |

| Changeability | Alterability of phenotypes by single base mutations | Average probability of phenotype change via single base substitution [3] | Facilitates evolvability and adaptation to new environments |

Natural Variants of the Genetic Code

Documented Deviations in Nuclear and Mitochondrial Codes

Comparative genomics has revealed systematic genetic code variations across multiple biological lineages. These natural variants demonstrate that codon reassignment is an ongoing evolutionary process. The mitochondrial genome, with its reduced size and distinct evolutionary pressures, exhibits particularly widespread code deviations, but nuclear code variants also exist in diverse organisms [3].

Mitochondrial code variations often show lineage-specific patterns. For instance, in vertebrate mitochondria, the AUA codon is reassigned from isoleucine to methionine, and UGA is reassigned from a stop codon to tryptophan. More extensive reassignments are observed in invertebrate mitochondria, where entire codon families have shifted their amino acid assignments. These natural experiments provide crucial validation for computational models predicting the evolutionary trajectories of genetic codes [3].

Table 2: Representative Natural Variants of the Genetic Code

| Genetic System | Code ID | Codon Reassignments | Initiator Codons | Evolutionary Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial Vertebrata | MVe | UGA: Stop → Trp; AUA: Ile → Met; AGR: Arg → Stop | AUN, GUG (5 total) | 1. UGA Trp 2. AUA Met 3. AGR Stop |

| Mitochondrial Nematoda | MNe | UGA: Stop → Trp; AGR: Arg → Ser; AUA: Ile → Met | AUN, UUG, GUG (6 total) | 1. UGA Trp 2. AGR Ser 3. AUA Met |

| Nuclear Mycoplasma | CMy | UGA: Stop → Trp | AUN, NUG, UUA (8 total) | Single step reassignment |

| Nuclear Candida | CCa | CUG: Leu → Ser | AUG, CUG (2 total) | Unique reassignment |

Computational Analysis of Variant Formation

The origin of these deviant codes can be understood through computational frameworks that model the evolutionary pressure on robustness and changeability. Analysis suggests that the order of codon reassignment in deviant codes follows predictable patterns that maximize these properties. For example, in the mitochondrial vertebrate code (MVe), the UGA to tryptophan reassignment typically occurs first, followed by AUA to methionine, with AGR to stop reassignment occurring last [3].

This progression is not random but represents a path that significantly improves both robustness and changeability compared to alternative reassignment orders. The graph-based representation of genetic codes enables quantitative comparison of these properties across different code variants and prediction of evolutionarily viable trajectories from the standard genetic code [3].

Synthetic Biology: Engineering Genetic Code Expansion

Platform for Aromatic Noncanonical Amino Acid Incorporation

Recent advances in synthetic biology have enabled the engineering of genetic code expansion (GCE) systems that incorporate noncanonical amino acids (ncAAs) into proteins. A robust platform has been developed that couples the biosynthesis of aromatic ncAAs with genetic code expansion in E. coli, enabling cost-effective production of proteins containing ncAAs [5].

This platform addresses a major limitation in conventional GCE experiments: the high cost and poor membrane permeability of many ncAAs when supplied exogenously. By engineering a biosynthetic pathway that produces ncAAs from commercially available aryl aldehyde precursors inside the same host cell used for protein expression, the system achieves autonomous production of ncAAs and their direct incorporation into target proteins [5].

The designed pathway comprises three key enzymatic steps: (1) aldol reaction between glycine and aryl aldehyde catalyzed by L-threonine aldolase (LTA) to produce aryl serines; (2) conversion of aryl serines to aryl pyruvates by L-threonine deaminase (LTD); (3) transamination of aryl pyruvates to ncAAs by aromatic amino acid aminotransferase (TyrB) [5].

Table 3: Biosynthetic Pathway for Aromatic Noncanonical Amino Acids

| Pathway Step | Reactants | Enzyme | Products | Output Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldol Reaction | Aryl aldehyde + Glycine | L-threonine aldolase (LTA) | Aryl serines | 0.96 mM pIF from 1 mM aldehyde in 6h [5] |

| Deamination | Aryl serines | L-threonine deaminase (LTD) | Aryl pyruvates | Conversion efficiency >95% in vitro [5] |

| Transamination | Aryl pyruvates + L-Glu | Aromatic aminotransferase (TyrB) | ncAAs + α-ketoglutarate | 19 ncAAs incorporated into sfGFP [5] |

| Protein Incorporation | ncAA + Amber codon | Orthogonal translation system | Modified protein | 40 ncAAs produced; platform demonstrated with macrocyclic peptides and antibody fragments [5] |

Protocol: Coupled Biosynthesis and Incorporation of Aromatic ncAAs

Objective: To produce site-specifically modified superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) containing aromatic ncAAs using coupled biosynthesis and incorporation in E. coli.

Materials:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) strain harboring pACYCDuet-PpLTA-RpTD plasmid

- Expression vector for orthogonal translation system (e.g., MmPylRS/tRNAPyl for amber suppression)

- Aryl aldehyde precursor (e.g., para-iodobenzaldehyde)

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

- IPTG for induction

Methodology:

Pathway Preparation: Transform the E. coli host with both the biosynthetic pathway plasmid (pACYCDuet-PpLTA-RpTD) and the orthogonal translation system plasmid containing the target gene (sfGFP with amber mutation at desired position) [5].

ncAA Biosynthesis: Inoculate transformed cells into LB medium with antibiotics and grow at 37°C with shaking until OD600 reaches 0.6. Add aryl aldehyde precursor to final concentration of 1 mM and continue incubation for 2-4 hours to allow ncAA biosynthesis [5].

Protein Expression Induction: Add IPTG to final concentration of 0.5 mM to induce expression of the orthogonal translation system and target protein. Incubate for 16-20 hours at 25°C with shaking.

Protein Purification and Validation: Harvest cells by centrifugation, lyse, and purify the target protein using appropriate chromatography methods. Verify ncAA incorporation through mass spectrometry and functional assays.

Validation Metrics:

- Successful incorporation of 19 different aromatic ncAAs into sfGFP demonstrated

- Production of 40 different aromatic amino acids from corresponding aldehydes

- Application to production of macrocyclic peptides and antibody fragments confirmed [5]

Computational Frameworks for Simulating Code Flexibility

Realistic Genome Simulation with Selection

The stdpopsim framework has emerged as a powerful community resource for simulating realistic evolutionary scenarios, including selection pressures on genetic variation. Recent extensions to this platform enable simulation of various modes of selection, including background selection, selective sweeps, and arbitrary distributions of fitness effects acting on annotated genomic regions [8].

This framework allows researchers to benchmark statistical methods for detecting selection and explore theoretical predictions about how selection shapes genetic diversity. The platform incorporates species-specific genomic annotations and published estimates of fitness effects, enabling highly realistic simulations that account for heterogeneous recombination rates and functional sequence density across genomes [8].

Key innovations include the DFE class for specifying distributions of fitness effects and the Annotation class for representing functional genomic elements. These abstractions enable precise modeling of how selection operates differently across genomic contexts, from exons to intergenic regions, providing a sophisticated tool for understanding the interplay between selection and other evolutionary forces [8].

Protocol: Simulating Selection with stdpopsim

Objective: To simulate genetic variation under realistic models of selection and demography using the stdpopsim framework.

Materials:

- Python installation with stdpopsim package (version 1.1.0 or higher)

- Species genetic map and annotation data (available through stdpopsim catalog)

- Demographic model appropriate for target species

- Distribution of fitness effects parameters from published estimates

Methodology:

Environment Setup:

Species and Model Selection:

Selection Parameter Specification:

Annotation Integration:

Simulation Execution:

Output Analysis: Calculate diversity statistics, site frequency spectrum, or other population genetic metrics from the resulting tree sequence.

Validation: The simulation framework has been validated through comparison of method performance for demographic inference, DFE estimation, and selective sweep detection across multiple species and scenarios [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Code Flexibility Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Context | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| stdpopsim Library | Community-maintained simulation of population genetics with selection | Benchmarking statistical methods, exploring theoretical predictions [8] | Simulation of selection modes (background selection, selective sweeps) with species-specific genomic annotations [8] |

| Orthogonal Translation Systems (OTS) | Incorporation of noncanonical amino acids at specific codon positions | Genetic code expansion for novel protein functions [5] | MmPylRS/tRNAPyl pair for amber suppression with biosynthesized ncAAs [5] |

| L-Threonine Aldolase (LTA) | Catalyzes aldol reaction between glycine and aryl aldehydes | Biosynthesis of aryl serine intermediates for ncAA production [5] | Conversion of aryl aldehydes to aryl serines in E. coli BL21(PpLTA-RpTD) strain [5] |

| T7-ORACLE System | Continuous hypermutation and accelerated evolution in E. coli | Protein engineering through directed evolution [9] | Evolution of TEM-1 β-lactamase resistance 5000x higher than original in less than one week [9] |

| AI-Driven Protein Design Tools | De novo protein design with atom-level precision | Creating novel protein structures and functions beyond evolutionary constraints [10] | RFdiffusion for backbone generation and ProteinMPNN for sequence design of novel enzymes [10] |

Impact of Code Structure on Protein Evolution and Landscape Topography

The structure of the genetic code is not merely a passive mapping between nucleotide triplets and amino acids; it actively shapes protein evolution by influencing the accessibility and distribution of mutational pathways on fitness landscapes. This application note examines how the robust nature of the standard genetic code governs the effects of single-nucleotide mutations, thereby modulating protein evolvability and landscape topography. We provide a quantitative analysis of these relationships, detailed protocols for simulating code-driven evolution, and a visualization of the underlying mechanisms. Framed within computational research on genetic code robustness, this resource equips scientists with methodologies to predict evolutionary trajectories and engineer proteins with enhanced stability and function.

The fitness landscape is a foundational concept in evolutionary biology, metaphorically representing the mapping between genetic sequences and organismal reproductive success [11]. In protein science, this translates to how amino acid sequences correlate with functional efficacy, where landscape peaks correspond to high-fitness sequences and valleys to low-fitness ones. The topography of this landscape—its ruggedness, slopes, and the distribution of peaks—is profoundly influenced by the rules of the genetic code.

The standard genetic code exhibits remarkable robustness to mutation, a property that minimizes the deleterious impact of random nucleotide changes [12]. This robustness directly affects protein evolvability—the capacity of mutation to generate adaptive functional variation. A key, unresolved question is whether this robustness facilitates or frustrates the discovery of new adaptive peaks. Computational simulations and empirical studies now reveal that the code's structure biases the mutational neighborhood of a sequence, making certain amino acid changes more accessible than others and thereby shaping the walk of a protein across its fitness landscape [13] [12]. This document details the quantitative data, experimental protocols, and key reagents for investigating this critical relationship.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings on the impact of genetic code structure and stability constraints on protein evolution.

Table 1: Impact of Genetic Code Structure on Mutational Outcomes

| Parameter | Description | Quantitative Effect/Value | Implication for Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Code Robustness | Minimization of deleterious amino acid changes via single-nucleotide mutations. | Primary feature of the standard genetic code [12]. | Enhances evolutionary robustness by buffering against harmful mutations; shapes the available paths for adaptation. |

| Transition/Transversion Bias | Preferential mutation rates between nucleotide types, controlled by a rate ratio. | Incorporated in evolutionary simulators (e.g., RosettaEvolve) to model natural bias [13]. | Skews the proposal distribution of new amino acid variants, influencing which areas of the fitness landscape are explored first. |

| Pleiotropic Mutational Effects | A single mutation impacting multiple molecular traits (e.g., activity, stability, cofactor binding). | Strong driver of epistatic interactions, limiting available adaptive pathways to a fitness optimum [14]. | Creates ruggedness in the fitness landscape, where the effect of a mutation depends heavily on the genetic background. |

Table 2: Fitness and Stability Parameters from Evolutionary Simulations

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range / Value | Computational/Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Stability (ΔG) | Folding free energy. | -5 to -10 kcal/mol for natural proteins [13]. | A central fitness constraint; marginal stability is maintained under mutation-selection balance. |

| Fitness Offset (O) | Parameter controlling selection pressure in fitness functions. | Variable; modulates the stability-fitness relationship [13]. | High O value facilitates destabilizing mutations; low O value forces stabilizing mutations. |

| Fraction Folded (ω) | Fitness proxy based on protein stability. | ω = 1 / (1 + exp(Eᵣₒₛₑₜₜₐ/RT - O)) [13]. | Used in simulators like RosettaEvolve to compute fitness from calculated Rosetta energy. |

| Relative MIC Increase | Measure of antibiotic resistance fitness. | 25-fold increase for an optimized metallo-β-lactamase variant (GLVN) [14]. | Empirical fitness measure in directed evolution experiments connecting molecular traits to organismal fitness. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: All-Atom Simulation of Protein Evolution with RosettaEvolve

This protocol describes how to simulate long-term protein evolutionary trajectories using the RosettaEvolve platform, which integrates an atomistic energy function with population genetics.

1. System Setup and Initialization

- Structure Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution three-dimensional structure of the protein of interest (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank).

- Parameter Configuration: Define the simulation parameters in the RosettaEvolve configuration file. Key parameters include:

- population_size: The effective population size (N), which magnifies selection pressure.

- fitness_offset: The offset parameter (O) in the fitness function, which controls selection stringency.

- transition_transversion_ratio: The bias for transitions over transversions (typically set to reflect natural observed ratios).

- Native State Energy Calculation: Run an initial Rosetta energy calculation on the native sequence. The stability (ΔG) is calculated as ΔG = Erosetta - Eref, where Eref is a reference energy offset.

2. Evolutionary Cycle and Mutation Introduction

- The simulation operates at the nucleotide level to accurately model the structure of the genetic code.

- In each generation, mutations are introduced as random nucleotide substitutions in the gene sequence.

- The type of substitution (transition or transversion) is weighted by the predefined transition_transversion_ratio.

3. Fitness Evaluation and Fixation Probability - For each generated mutant sequence, the corresponding protein structure is modeled in Rosetta. - The change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) is computed on-the-fly, accounting for side-chain flexibility and minor backbone adjustments: ΔGmutant = ΔGparent + ΔΔGparent→mutant. - Fitness (ω) is calculated using the defined fitness function, typically the "fraction folded" model: ω = 1 / (1 + exp(Eᵣₒₛₑₜₜₐ/RT - O)). - The probability of a mutation fixing in the population is determined using a population genetics framework (e.g., the probability is proportional to (1 - exp(-2s)) / (1 - exp(-4Ns)), where s is the selection coefficient derived from fitness).

4. Data Collection and Analysis - Phylogenetic Trees: Record the complete ancestry of sequences to build in silico phylogenetic trees. - Site-Specific Rates: Track the rate of accepted mutations at individual amino acid positions. - Covariation Analysis: Analyze the sequence alignment output for patterns of correlated amino acid substitutions between residue pairs. - Stability Trajectory: Monitor the fluctuation of the protein's stability (ΔG) over evolutionary time.

Protocol 2: Empirical Mapping of a Local Fitness Landscape

This protocol outlines the experimental procedure for quantitatively describing a local fitness landscape around an optimized protein variant, as demonstrated for metallo-β-lactamase [14].

1. Generate Combinatorial Mutant Library - Variant Selection: Identify a set of n key mutations (e.g., G262S, L250S, V112A, N70S) that lead to a fitness optimum. - Library Construction: Synthesize all possible 2n combinatorial variants of these n mutations. This creates a complete local fitness landscape.

2. Measure Molecular Phenotypes - Activity Assays: Purify each variant and determine kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) against relevant substrates. - Stability Measurements: Determine the thermodynamic stability (e.g., ΔG of folding, Tm) of each purified variant using techniques like thermal shift assays or circular dichroism. - Cofactor Affinity: For metalloenzymes, measure the Zn(II) binding affinity. For other proteins, quantify the binding of essential cofactors. - In-Cell Phenotyping: Measure key parameters (e.g., activity, stability) in periplasmic extracts or cellular lysates to mimic the native environment and account for cellular quality control systems.

3. Determine Organismal Fitness - Antibiotic Resistance: For β-lactamases, determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of relevant antibiotics for each variant in a bacterial host. The MIC serves as a direct proxy for organismal fitness in this context.

4. Analyze Epistasis and Pathway Accessibility - Calculate Epistasis: Quantify the deviation of the fitness (MIC) for each double or multiple mutant from the expected value if the individual mutations acted additively. - Identify Sign Epistasis: Note instances where a mutation is beneficial on one genetic background but deleterious on another. - Map Adaptive Pathways: Analyze the combinatorial landscape to determine all possible mutational paths to the optimum and identify which are accessible (i.e., involve no fitness valleys).

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Genetic Code Influence on Fitness Landscape Exploration

RosettaEvolve Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| RosettaEvolve | Software Package | All-atom simulator of protein evolution that integrates molecular modeling with population genetics. | Simulating evolutionary trajectories under defined fitness constraints to study stability, rates, and covariation [13]. |

| Rosetta Macromolecular Modeling Suite | Software Library | Provides the atomistic energy function for calculating protein stability (ΔΔG) upon mutation. | On-the-fly energy evaluation during evolutionary simulations; accounts for side-chain flexibility [13]. |

| Combinatorial Mutant Library | Experimental Resource | A complete set of all combinations of a defined set of n mutations (2n variants). | Empirically mapping local fitness landscapes and detecting epistatic interactions [14]. |

| Metallo-β-lactamase (BcII) | Model Protein System | A Zn(II)-dependent enzyme conferring antibiotic resistance, subject to fitness constraints from stability, activity, and metal binding. | Dissecting the contribution of multiple molecular traits to organismal fitness (e.g., via MIC assays) [14]. |

| Fraction Folded Fitness Model | Computational Model | A fitness function that equates fitness with the proportion of folded protein, based on calculated stability. | ω = 1 / (1 + exp(Eᵣₒₛₑₜₜₐ/RT - O)); used in evolutionary simulations [13]. |

Computational Methods for Simulating and Leveraging Genetic Robustness

The PEREGGRN (PErturbation Response Evaluation via a Grammar of Gene Regulatory Networks) framework represents a comprehensive benchmarking platform designed to evaluate the performance of computational methods for expression forecasting—predicting transcriptomic changes in response to novel genetic perturbations. This framework addresses a critical need in computational biology for standardized, neutral assessment of the growing number of machine learning methods that promise to forecast cellular responses to genetic interventions. By combining a curated collection of 11 large-scale perturbation datasets with a flexible software engine, PEREGGRN enables systematic comparison of diverse forecasting approaches, parameters, and auxiliary data sources. This application note details the platform architecture, experimental protocols, and implementation guidelines to facilitate its adoption within the broader context of computational simulation of genetic code robustness research.

Expression forecasting methods have emerged as powerful computational tools that predict how genetic perturbations alter cellular transcriptomes, with applications spanning developmental genetics, cell fate engineering, and drug target identification [15]. These methods offer a fast, inexpensive, and accessible complement to experimental approaches like Perturb-seq, potentially doubling the chance that preclinical findings survive translation to clinical applications [15]. However, the rapid proliferation of these computational methods has outpaced rigorous evaluation of their accuracy and reliability.

The PEREGGRN framework addresses this gap by providing a standardized benchmarking platform that enables neutral comparison of expression forecasting methods across diverse biological contexts [15]. This platform is particularly valuable for researchers investigating genetic code robustness, as it facilitates systematic assessment of how well computational models can predict system responses to perturbation, a fundamental aspect of robustness. Unlike benchmarks conducted by method developers themselves, which may suffer from optimistic results due to researcher degrees of freedom, PEREGGRN aims to provide unbiased evaluations essential for method selection and improvement [15] [16].

Platform Architecture and Components

Core Software Engine: GGRN

The Grammar of Gene Regulatory Networks (GGRN) forms the computational core of the PEREGGRN framework, providing a flexible software engine for expression forecasting [15]. Key capabilities include:

- Multiple Regression Methods: Implementation of nine different regression approaches, including mean and median dummy predictors as simple baselines

- Network Structure Integration: Efficient incorporation of user-provided network structures, including dense or empty negative control networks

- Perturbation-Aware Training: Automatic omission of samples where a gene is directly perturbed when training models to predict that gene's expression

- Differential Prediction Modes: Support for both steady-state expression prediction and change-in-expression prediction relative to control samples

- Iterative Forecasting: Capacity for multiple iterations to model different prediction timescales

- Flexible Modeling Strategies: Options for both cell type-specific models and global models trained on all available data

GGRN can interface with any containerized method, enabling head-to-head comparison of both individual pipeline components and complete expression forecasting workflows [15].

Benchmarking Datasets

PEREGGRN incorporates a curated collection of 11 quality-controlled, uniformly formatted perturbation transcriptomics datasets (Table 1), focused on human data to maximize relevance for drug discovery and cellular engineering applications [15]. These datasets were selected to represent diverse perturbation contexts and include those previously used to showcase expression forecasting methods. Each dataset undergoes rigorous quality control, including verification that targeted genes show expected expression changes in response to perturbations (with success rates ranging from 73% in the Joung dataset to 92% in Nakatake and replogle1), filtering of non-conforming samples, and assessment of replicate concordance [15].

Table 1: PEREGGRN Benchmark Dataset Characteristics

| Dataset Identifier | Perturbation Type | Cell Type/Line | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joung | Overexpression | Pluripotent stem cells | 73% of overexpressed transcripts increased as expected |

| Nakatake | Overexpression | Pluripotent stem cells | 92% success rate for expected expression changes |

| replogle1 | Various perturbations | Multiple cell types | 92% success rate for expected expression changes |

| replogle2 | Various perturbations | Multiple cell types | Limited replication available |

| replogle3 | Various perturbations | Multiple cell types | Limited replication available |

| replogle4 | Various perturbations | Multiple cell types | Limited replication available |

Evaluation Metrics and Data Splitting

A critical innovation in PEREGGRN is its specialized data splitting strategy that tests generalization to unseen perturbations [15]. Rather than random splitting, the framework ensures no perturbation condition appears in both training and test sets, with distinct perturbation conditions allocated to each. This approach rigorously tests the real-world scenario of predicting responses to novel interventions.

The platform implements multiple evaluation metrics (Table 2) categorized into three groups:

- Standard performance metrics (mean absolute error, mean squared error, Spearman correlation)

- Metrics focused on top differentially expressed genes

- Cell type classification accuracy for reprogramming studies

Table 2: PEREGGRN Evaluation Metrics

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Standard performance metrics | Mean absolute error (MAE), Mean squared error (MSE), Spearman correlation, Direction of change accuracy | General method performance assessment |

| Focused metrics | Performance on top 100 most differentially expressed genes | Emphasis on strong signal genes rather than genome-wide noise |

| Biological context metrics | Cell type classification accuracy | Reprogramming and cell fate studies |

The choice of evaluation metric significantly impacts method rankings, as different metrics reflect various aspects of biological relevance [15]. This multi-metric approach provides a more comprehensive assessment than single-score comparisons.

Experimental Protocols

Benchmarking Implementation Workflow

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control Protocol

- Dataset Collection: Curate perturbation transcriptomics datasets with numerous genetic perturbations and prior use in expression forecasting studies [15]

- Quality Control:

- Verify expected expression changes in targeted genes (e.g., increased expression after overexpression)

- Remove samples where targeted transcripts do not show expected directional changes

- Assess replicate concordance using Spearman correlation in log fold change

- Compute cross-dataset correlations for similar cell types and perturbation directions

- Normalization: Apply uniform formatting, aggregation, and normalization across all datasets

- Data Splitting: Allocate distinct perturbation conditions to training and test sets, with all controls in training data

Method Evaluation Protocol

- Baseline Establishment: Initialize predictions with average expression of all controls

- Perturbation Application:

- Set perturbed gene to 0 for knockout experiments

- Use observed post-intervention values for knockdown or overexpression experiments

- Model Prediction: Generate expression forecasts for all genes except directly perturbed targets

- Performance Assessment: Calculate all relevant metrics from Table 2

- Statistical Analysis: Compare method performance against simple baselines across multiple datasets

Key Findings and Applications

Performance Insights

Initial benchmarking using the PEREGGRN framework revealed several critical insights:

- Expression forecasting methods infrequently outperform simple baselines on metrics like mean squared error [15] [17]

- Method performance is highly metric-dependent, with different methods excelling on different evaluation measures [15]

- The choice of evaluation metric should align with biological assumptions and application requirements [15]

- Performance varies substantially across cellular contexts and perturbation types

Application to Genetic Code Robustness Research

For researchers investigating genetic code robustness, PEREGGRN provides:

- A standardized framework to assess predictive models of perturbation response

- Tools to evaluate how well computational methods capture system stability and resilience properties

- Metrics relevant to cell fate stability during reprogramming interventions

- Capacity to test context-specific robustness across cell types and conditions

Implementation Guidelines

Computational Requirements

PEREGGRN is designed for extensibility and can interface with containerized methods [15]. Implementation considerations include:

- Software Dependencies: Python-based core with flexibility for R and other languages through containerization

- Hardware Requirements: Variable based on dataset size and method complexity; support for high-performance computing environments

- Containerization: Docker or Singularity support for reproducible method execution

Experimental Design Considerations

Based on general benchmarking principles [16], PEREGGRN implementations should:

- Define Clear Scope: Explicitly state the expression forecasting tasks being evaluated

- Select Appropriate Methods: Include both established baselines and state-of-the-art approaches

- Use Multiple Datasets: Ensure evaluations span diverse biological contexts

- Report Comprehensive Results: Include both quantitative metrics and qualitative insights about method behavior

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function in Expression Forecasting |

|---|---|---|

| PEREGGRN Framework | Software platform | Centralized benchmarking infrastructure for method evaluation |

| GGRN Engine | Computational engine | Core forecasting capability with multiple regression methods |

| Perturbation Datasets | Experimental data | 11 curated transcriptomics datasets for training and validation |

| Gene Regulatory Networks | Prior knowledge | Network structures from motif analysis, co-expression, etc. |

| Containerization Tools | Computational environment | Docker/Singularity for reproducible method execution |

| Evaluation Metrics | Assessment framework | Multiple metrics for comprehensive performance assessment |

Visualization Framework

Future Directions

The PEREGGRN framework continues to evolve with several planned enhancements:

- Expanded Dataset Collections: Incorporation of additional perturbation modalities and single-cell resolution data

- Standardized Interfaces: Improved interoperability with emerging expression forecasting methods

- Community Challenges: Organization of benchmark competitions to drive method innovation

- Integration with Simulation Platforms: Connection to genetic robustness simulation environments

As expression forecasting matures, PEREGGRN will serve as a critical resource for validating new computational methods and identifying contexts where in silico perturbation screening can reliably augment or replace experimental approaches [15].

The advent of large-scale foundation models is revolutionizing the field of genomics, offering unprecedented capabilities for predicting molecular phenotypes from DNA sequences. The Nucleotide Transformer (NT) represents a significant breakthrough in this domain, adapting the transformer architecture—successful in natural language processing—to learn complex patterns within DNA sequences [18] [19]. These models, ranging from 50 million to 2.5 billion parameters, are pre-trained on extensive datasets encompassing 3,202 diverse human genomes and 850 genomes from various species [18]. This approach addresses the longstanding challenge in genomics of limited annotated data and the difficulty in transferring learnings between tasks. When integrated with transfer learning methodologies, these foundation models enable accurate predictions even in low-data settings, providing a powerful framework for genomic selection and variant prioritization [18] [20]. This application note details the implementation, performance, and protocols for leveraging these technologies within computational simulation pipelines for genetic code robustness research.

The Nucleotide Transformer Framework

Model Architecture and Training

The Nucleotide Transformer models employ a transformer-based architecture specifically designed for processing DNA sequences. The models utilize a tokenization strategy where DNA sequences are broken down into 6-mer tokens when possible, with a vocabulary size of 4105 distinct tokens [21]. Key architectural innovations in the second-generation NT models include the use of rotary positional embeddings instead of learned ones, and the introduction of Gated Linear Units, which enhance the model's ability to capture long-range dependencies in genomic sequences [21].

The pre-training process follows a masked language modeling objective similar to BERT-style training in natural language processing, where:

- 15% of tokens are masked

- In 80% of cases, masked tokens are replaced by [MASK]

- In 10% of cases, masked tokens are replaced by random tokens

- In 10% of cases, masked tokens are left unchanged [21]

Training was conducted on the Cambridge-1 supercomputer using 8 A100 80GB GPUs with an effective batch size of 1 million tokens, spanning 300 billion tokens total [21] [19]. The models were trained with the Adam optimizer (β1=0.9, β2=0.999, ε=1e-8) with a learning rate schedule that included warmup and square root decay [21].

Model Variants and Specifications

Table 1: Nucleotide Transformer Model Variants

| Model Name | Parameters | Training Data | Context Length | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT-v2-50m-multi-species | 50 million | 850 diverse genomes | 1,000 tokens | Rotary embeddings, GLU [21] |

| Human ref 500M | 500 million | Human reference genome | 6,000 bases | Initial human-focused model [18] |

| 1000G 500M | 500 million | 3,202 human genomes | 6,000 bases | Population diversity [18] |

| 1000G 2.5B | 2.5 billion | 3,202 human genomes | 6,000 bases | Large-scale human variation [18] |

| Multispecies 2.5B | 2.5 billion | 850 species + human genomes | 6,000 bases | Maximum diversity [18] |

Transfer Learning Methodology for Genomics

Conceptual Framework

Transfer learning in genomics involves leveraging knowledge from a source domain (proxy environment) to improve predictions in a target domain with limited data [20]. This approach is particularly valuable for genomic selection (GS), where it addresses challenges of limited training data and environmental variability [20] [22]. The method works by pre-training models on large, diverse datasets from source domains and fine-tuning them with smaller datasets specific to target domains, allowing researchers to harness genetic patterns and environmental interactions that would be difficult to detect with limited target data alone [20].

Implementation Protocols

Two-Stage Transfer Learning Protocol

For genomic prediction tasks, a two-stage transfer learning approach has demonstrated significant improvements in predictive accuracy:

Stage 1: Proxy Model Pre-training

- Train a model using the predictor: Yi = μ + xPiTβ + εi

- Where Yi represents Best Linear Unbiased Estimates (BLUEs) for the i-th genotype in the proxy environment

- xPi denotes standardized marker information in the proxy environment

- β represents vector of beta coefficients learned from proxy data [20]

Stage 2: Target Model Enhancement

- Implement enriched target model: Yi = μ + gi + γ(xTiTβ) + εi = μ + gi + γĝi + εi

- The β vector learned from the proxy environment enriches the target model

- γ modulates the influence of the proxy-derived predictions [20]

This approach has demonstrated improvements in Pearson's correlation by 22.962% and reduction in normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) by 5.757% compared to models without transfer learning [22].

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

For adapting pre-trained Nucleotide Transformer models to specific downstream tasks, parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques reduce computational requirements:

- Requires only 0.1% of total model parameters compared to full fine-tuning

- Enables faster fine-tuning on a single GPU

- Reduces storage needs by 1,000-fold while maintaining comparable performance [18]

Performance Benchmarking

Molecular Phenotype Prediction

The Nucleotide Transformer models were rigorously evaluated on 18 genomic prediction tasks encompassing splice site prediction, promoter identification, histone modification, and enhancer activity [18]. The benchmark compared fine-tuned NT models against specialized supervised models like BPNet, which represents a strong baseline in genomics with 28 million parameters [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Genomic Tasks (Matthews Correlation Coefficient)

| Model Type | Average MCC | Tasks Matched Baseline | Tasks Surpassed Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPNet (Supervised) | 0.683 | Baseline | Baseline |

| NT Probing | 0.665 (avg) | 5/18 | 8/18 |

| NT Fine-tuned | >0.683 | 6/18 | 12/18 |

The Multispecies 2.5B model consistently outperformed or matched the 1000G 2.5B model on human-based assays, indicating that increased sequence diversity rather than just model size drives improved prediction performance [18].

Robustness Evaluation Framework

Robustness in genomic predictions can be systematically evaluated using tools like RobustCCC, which assesses performance stability across three critical dimensions:

- Replicated data (biological replicates, simulated replicates)

- Transcriptomic data noise (Gaussian noise, dropout events)

- Prior knowledge noise (cell type permutation, ligand-receptor permutation) [23]

The robustness is quantified using Jaccard coefficients of inferred ligand-receptor pairs between simulation data and original data, averaged across multiple cell sampling or data noising proportions [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nucleotide Transformer Fine-tuning for Specific Genomic Tasks

Purpose: Adapt pre-trained NT models for specific genomic prediction tasks with limited labeled data.

Materials:

- Pre-trained Nucleotide Transformer model (e.g., NT-v2-50m-multi-species)

- Task-specific genomic sequences with labels

- Computing environment with GPU acceleration

- Python with transformers library installed from source

Procedure:

- Environment Setup

Sequence Tokenization

Embedding Extraction

Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning

- Freeze base model parameters

- Add task-specific head with adapters

- Train only adapter parameters (0.1% of total)

- Use task-appropriate loss function (cross-entropy for classification) [18]

Protocol 2: Transfer Learning for Genomic Selection

Purpose: Implement transfer learning from proxy to target environments for enhanced genomic prediction.

Materials:

- Genotypic and phenotypic data from proxy and target environments

- Computational resources for Bayesian regression

- BGLR library in R [20]

Procedure:

- Proxy Model Training

- Standardize marker information in proxy environment

- Fit model: Yi = μ + xPiTβ + εi

- Estimate β coefficients using Bayesian methods

Target Model Implementation

- Incorporate proxy-derived β into target model: Yi = μ + gi + γ(xTiTβ) + εi

- Use genomic relationship matrix G for random effects

- Estimate γ parameter to modulate proxy contribution

Cross-Validation

Workflow Visualization

Foundation Model and Transfer Learning Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transformer Models | Foundation models for genomic sequence analysis | Hugging Face Hub: InstaDeepAI/nucleotide-transformer [24] [21] |

| Agro Nucleotide Transformer | Specialized model for plant genomics | InstaDeepAI GitHub repository [24] |

| SegmentNT | Genomic element segmentation at single-nucleotide resolution | InstaDeepAI GitHub repository [24] |

| RobustCCC | Robustness evaluation for cell-cell communication methods | GitHub: GaoLabXDU/RobustCCC [23] |

| BIOCHAM 2.8 | Robustness analysis with temporal logic specifications | http://contraintes.inria.fr/BIOCHAM/ [25] |

| BGLR Library | Bayesian generalized linear regression for genomic selection | CRAN R package [20] |

| GGRN/PEREGGRN | Expression forecasting and benchmarking framework | Publication: Genome Biology 2025 [15] |

The integration of foundation models like the Nucleotide Transformer with transfer learning methodologies represents a paradigm shift in computational genomics. These approaches enable robust molecular phenotype prediction even in data-limited settings, overcoming traditional challenges in genomic research. The protocols and frameworks outlined in this application note provide researchers with practical tools to leverage these advanced technologies for enhanced genomic selection, variant prioritization, and functional genomics investigations. As these models continue to evolve, they promise to unlock new insights into genetic code robustness and its implications for disease mechanisms and therapeutic development.

Bayesian Inference of Genome-Wide Genealogies for Hundreds of Genomes

The Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG) is a comprehensive genealogical history of a sample of genomes, representing the complex interplay of coalescence and recombination events across genomic positions [26]. As a vital tool in population genomics and biomedical research, accurate ARG inference enables powerful analyses in evolutionary biology, disease mapping, and selection detection [26] [27]. However, reconstructing ARGs from genetic variation data presents substantial computational challenges due to the enormous space of possible genealogies and the need to account for uncertainty [26].

Recent methodological advances have improved the scalability of ARG reconstruction, yet many approaches rely on approximations that compromise accuracy, particularly under model misspecification, or provide only a single ARG topology without quantifying uncertainty [26]. The SINGER (Sampling and Inferring of Genealogies with Recombination) algorithm addresses these limitations by enabling Bayesian posterior sampling of genome-wide genealogies for hundreds of whole-genome sequences, offering enhanced accuracy, robustness, and proper uncertainty quantification [26] [28]. This protocol details the application of SINGER within the broader context of computational simulation of genetic code robustness research, providing researchers with comprehensive methodological guidance for inferring genome-wide genealogies and analyzing their implications for genetic variation and evolutionary processes.

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Through extensive simulations using msprime [26] [27], SINGER has been benchmarked against established ARG inference methods including ARGweaver, Relate, tsinfer+tsdate, and ARG-Needle across multiple accuracy dimensions [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Coalescence Time Estimation Accuracy

| Method | Sample Size | Mean Squared Error | Correlation with Truth | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SINGER | 50 haplotypes | 0.78 | Highest | Most accurate |

| ARGweaver | 50 haplotypes | >0.78 | High | Similar to Relate |

| Relate | 50 haplotypes | >0.78 | High | Similar to ARGweaver |

| tsinfer+tsdate | 50 haplotypes | >0.78 | Lowest | Least accurate |

| SINGER | 300 haplotypes | Lowest | Highest | Most accurate |

| ARG-Needle | 300 haplotypes | Medium | Medium | Similar to Relate |

| Relate | 300 haplotypes | Medium | Medium | Similar to ARG-Needle |

| tsinfer+tsdate | 300 haplotypes | Highest | Lowest | Least accurate |

Table 2: Tree Topology and Additional Performance Metrics

| Method | Triplet Distance | Lineage Number Accuracy | Computational Speed | Uncertainty Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SINGER | Lowest | Matches expectation | 100x faster than ARGweaver | Full posterior sampling |

| ARGweaver | Higher than SINGER | Drops too fast | Slow (reference) | Full posterior sampling |

| Relate | Medium | Matches expectation | Fast | Single point estimate |

| tsinfer+tsdate | Highest | Substantial overestimation | Fast | Single point estimate |

| ARG-Needle | Not reported | Not reported | Fast | Single point estimate |

Robustness to Model Misspecification

SINGER incorporates an ARG re-scaling procedure that applies a monotonic transformation of node times to align the inferred mutation density with branch lengths [26]. This approach, conceptually similar to ARG normalization in ARG-Needle but learned directly from the inferred ARG without external demographic information, significantly improves robustness against violations of model assumptions such as constant population size [26]. In simulations, this re-scaling effectively mitigates biases introduced by demographic model misspecification, a common challenge in population genomic analyses [26].

Experimental Protocols

SINGER Algorithm Workflow

Input Data Requirements and Preparation

- Data Format: Phased whole-genome sequence data in VCF or similar format

- Data Quality Control: Implement standard QC filters for call rate, missingness, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- Phasing Accuracy: Ensure high-quality phasing using reference-based (e.g., Eagle2, Shapeit) or population-based methods

- Ancestral Allele Designation: When available, include ancestral state information to improve inference accuracy [27]

Core Algorithmic Components

Threading Operation: SINGER iteratively builds ARGs by adding one haplotype at a time through threading [26]. Conditioned on a partial ARG for the first n-1 haplotypes, the threading operation samples the points at which the lineage for the nth haplotype joins the partial ARG [26].

Two-Step Threading Algorithm:

- Branch Sampling: Construct a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) with branches as hidden states and sample a sequence of joining branches along the genome using stochastic traceback [26]

- Time Sampling: Build a second HMM with joining times as hidden states, conditioned on the sampled joining branches [26]

This two-step approach substantially reduces the number of hidden states compared to ARGweaver's HMM, which treats every joining point in the tree as a hidden state, resulting in significant computational acceleration [26].

Sub-graph Pruning and Re-grafting (SGPR): SINGER employs SGPR as a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) proposal to explore the space of ARG topology and branch lengths according to the posterior distribution [26]. The SGPR operation:

- Prunes a sub-graph by introducing a cut

- Extends the pruned sub-graph leftwards and rightwards

- Uses the threading algorithm to sample from the posterior during re-grafting [26]

Compared to prior approaches like the Kuhner move, which samples from the prior during re-grafting and rarely improves likelihood, SGPR favors data-compatible updates, introduces larger ARG updates with higher acceptance rates, and yields better convergence and MCMC mixing [26].

ARG Re-scaling: Apply a monotonic transformation of node times that aligns the inferred mutation density with branch lengths [26]. This calibration step improves robustness to model misspecification (e.g., population size changes) even though the HMMs assume a constant population size [26].

Implementation Protocol

Diagram 1: SINGER ARG inference workflow with MCMC iteration

Downstream Analysis Applications